#but satire is not inherently humorous

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

shrek and sandman are the same to me in the sense that they’re both stories fueled by reimagining old tales with the intent to serve as satirical commentary on the state of the modern world

#Shrek is obviously a comedy while sandman is not#but satire is not inherently humorous#I could write a fucking essay on this shit if you give me long enough#the sandman#shrek#my posts

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

What’s gross is that I bet you’re smarter than this, you just have a bizarre antagonistic parasocial relationship with Vivienne Medrano.

This critique is fundamentally flawed in its analysis, misinterpreting the narrative structure and character dynamics of Helluva Boss. Here’s a breakdown of why it doesn’t hold up:

1. The Claim About Blitz and Octavia:

The statement that Blitz “pretends Octavia’s mother never existed” grossly oversimplifies his behavior and motivations. Blitz’s struggles are rooted in his unresolved trauma and inability to form healthy relationships, not a deliberate erasure of Stella. Additionally, the idea that Stella is treated as a “nameless surrogate egg donor” is false. The show repeatedly acknowledges her presence, but she’s portrayed negatively because her actions (abusing Stolas, prioritizing status over family) make her an antagonist. This isn’t about erasing her but about exploring Stolas’s toxic marriage and its impact on Octavia.

2. The Misreading of Stella’s Character:

The critique argues that Vivienne “has to make the woman purely evil and unfeeling,” but Stella’s characterization is consistent with her role as an abusive partner and a foil to Stolas. Her lack of maternal care is a reflection of her values and personality, not an inherent “hatred of women.” Plenty of female characters in Helluva Boss are nuanced, compassionate, and strong (e.g., Millie, Loona, Octavia), disproving the claim of misogyny.

3. The Strawman Argument of “Gay Erotica”:

The scene where Blitz throws Stella out the window isn’t about her disliking “gay erotica.” It’s a comedic exaggeration that underscores the absurdity of the situation, fitting the show’s satirical tone. The focus isn’t on her gender but on the humor of the clash between her and Stolas.

4. The Daughters’ Reactions:

The daughters’ lack of mourning in the Christmas episode is a misinterpretation of the narrative focus. The scene is meant to emphasize Blitz’s moral growth, not delve into the daughters’ feelings. It’s also possible that the mom died quite some time ago and they have moved past actively mourning, but to assume they “don’t care” is reading into something the episode doesn’t explicitly address.

5. Accusation of Misandrist Themes:

Claiming that Vivienne portrays “gay men’s love as more pure” ignores the complexity of Stolas and Blitz’s relationship, which is far from idealized. Their love is messy, imperfect, and rooted in deep emotional baggage—hardly the pedestal the critique implies.

In summary, this critique misrepresents Helluva Boss by cherry-picking elements and ignoring context. The show’s nuanced exploration of flawed relationships, trauma, and humor-driven storytelling doesn’t align with the reductive and bad-faith interpretation presented here.

#helluva boss#media analysis#criticism response#blitzø#stolas#stella helluva boss#character analysis

122 notes

·

View notes

Text

Racism in Astarion's Writing

There is a fascist takeover happening in Europe. Again. With pogroms targeting racialized and marginalized groups. Being at all silent about how media affects our perception of reality would be irresponsible of me. I stand in solidarity with you all. I will polish this as I go along, but this is for anyone who wants to understand.

Block, report, and move on from the inevitable racist shitheads. We have work to do.

Donate to Gaza here: https://gazafunds.org/ Support good causes with a click here: https://arab.org/ Ceasefire Now: https://ceasefire-now.com/ Donate to the [Sidewalk School] [Pay your rent], settlers. [KOSA Resources]

There is a... let's be charitable for a moment and call it "knee-jerk" reaction to discussions of racism in fandom. To call it character assassination, exaggeration, slander - anything but to acknowledge the dehumanizing system of power that underlies every part of this imbalance. It's only scary if you don't understand it, and as part of another group under siege for half a millenia, I am intimately familiar with it.

There are Romani perspectives on Astarion's storyline I would encourage everyone to read before mine. I don't wish to link them in case this post gets targeted. Please lend them your kind support and sincere gratitude for their contributions.

I do not "forgive" a character for questionable biases. I wonder why the writers put it there. I question its purpose in the narrative and the effect it has on the story and audience.

Let's discuss the effect:

The racism in Astarion's storyline serves no purpose, but the effects are harmful.

I've played evil (poorly). But I also have a very fucked up sense of humor and understand the appeal of a well-written fucked up little dude. Take, for instance, this Warlock from a BG3 playthrough:

youtube

Absolutely vile, but a clearly theatrical/satirical look at a classist piece of shit, you know, that sort of character. Take it as a palate cleanser after reading, and then gather your strength.

This is not a post about liking flawed characters. Please take your strawman, dust behind you, and move along.

I often find the trouble with depicting racism is the inherent unfamiliarity with the subject in a majority-white writer's room and company. There is an idea of what it entails, but not its purpose, and not its day-to-day application.

There is a veritable treasure trove of knowledge out there that I've ended up having to take in small parts. It is not easy hearing about the ways people have hurt others, systemic and otherwise. I genuinely want us to learn from this and be better for one another.

So when I see depictions of people who are Indigenous and Romani and Sinti, I wonder... why? And why were these writers chosen for this character/storyline?

In Astarion's storyline, from what I can tell, he makes light of stealing the Gur children. I can tell this is meant to be a depiction of guilt and deflection. What sucks is the fact that he's ultimately a white man making light of the fact that's... historically what they do.

The point, I believe, of him "following Cazador's orders" is to invoke the Nuremberg Defense. The tragedy is that Astarion, by D&D logic, literally couldn't do anything but follow his command. It's implied because he's defensive as hell, but he feels exceedingly guilty regardless. For all we know, it's earned.

Is Racist Magistrate Astarion still canon? If so, his "grudge" against the Gur is motivated by racism. Is that something we are prepared to confront with more than a line? Was he just a (maybe recently?) privileged asshole exercising his newfound power? In that case, his use of systemic power over the Gur may be read as a parallel to his storyline. But then the Gur need autonomy as well.

There is something to be deconstructed here, but I would not know its intimacies from my perspective. Others would. They may restructure it altogether so that it makes sense for their experience.

Here is what I know, and it should not be on this group alone to point it out: The inappropriate misuse of these tropes has encouraged racism in the fandom at large.

Performing a script well is not the fault of the voice actor, nor is the twisted logic of fans the fault of the writers. I am pointing out that reckless inclusion of certain ideas can have very unfortunate implications:

youtube

So stealing their children, expressing little remorse, and then "sparing" them the pain of executing stolen marginalized children is a good ending? I'm adding some untagged comments here for emphasis:

I find it interesting the game recognizes the complexity of the situation regarding the spawn and doesn’t punish the players or Astarion whatever the choice as long as they aren’t doing it for selfish reasons. Some good, thoughtful writing there.

Wow, even as a dedicated Astarion romancer, I was beginning to feel like it was a little unfair how much more recognition Neil is getting over the rest of the cast, but now I’m reminded of why. I’ve finished the game 3 times and never even considered not sparing the spawn, because if he deserves a chance, why don’t they? But the conviction he has behind his words in this makes me think I’ve been making the wrong choice.

Person 1: I really dislike Ulma. She’s such a judgmental Monday morning quarterback. Person 2: same, no matter what you do she'll blame Astarion for things that were outside his control

Spawn Astarion sparing their children as spawn is better and in line with his story, but for some reason, that isn't acknowledged through commentary, dialogue, or mechanics... thus, again, unfortunate implications:

To the spawn Astarion, Greetings from the family of Ulma, hunters of monsters and keepers of peace across Faerun. We know this letter finds you well, for although we hunt you no longer, we do sometimes keep a watch. Your restraint and control over your bloodlust has been admirable. Indeed, it has been an inspiration for our children, who have struggled with their own hunger. These last months have been a difficult time for our people. We have protected and nurtured our children as best we can, and we have learned much. Herbs we once used to dull our foes' minds are now sedatives to ease hunger and pain, restraints built to hold the undead now protect them from themselves. There has been a lot of pain, but a lot of progress too. Our children learned discipline and control, while we learned compassion and patience. There was a time when we would have destroyed any undead creature, our own blood or not, and called it a mercy. But then we met you. Wer saw that redemption was possible. Difficult, yes. Painful. But possible. You saved our children first from Cazador, and then from us. For that, we thank you. We will watch you still, but with more admiration than fear. Walk in peace, Astarion.

And, according to these commenters, it's better to kill them because the marginalized Elder is never satisfied with the man who stole their children?

It sounds so casual, I think. Perhaps they don't know what stealing children from a community really means.

60s scoop/residential school/reeducation camps trigger warning:

(The Scream by Kent Monkman. Alt text in link.)

Look at this painting.

Take it in with me for a moment. It is a scene taken from many memories and one. Look at how these families fought to stay together. Look at how they fight priests, nuns, and state officials - ones who my friend assured me are very friendly - how they grasp at their children with such painful desperation on their faces. It is a way for one to bear witness to unfathomable love and heartbreak.

When genocide deniers play their games, this is what they want you to pretend never happened. Don't mind the tens of thousands of child graves, or the stolen land. Just pretend these people are criminals out to swindle you, or steal your wives.

Growing up, listening to survivor testimonies, and the sweet reverberance of the remnants of survivors of slavery, you appreciate what you have. You remember every kindness. You love what you lost, and what you gained through gritted teeth.

And, you remember the unfathomable pain. It's why you promise to stop it from ever happening again, to anyone.

It is very sad. A heart is a heavy burden. Embrace it. To love is to live again, and to live again means you understand Never Again. Because people deserve to be happy. And that's worth a fight. That's why it's worth depicting with care and love, even when the subject matter threatens to choke you.

Let's get into Cazador Szarr.

I've played the game and understand that he has a backstory and some depth. What disturbs me is that an Asian man has the bloodiest, most brutal scene in the game with a white man killing him.

I can't let this be undiscussed as sinophobia rises in a pandemic. I am no authority, but I'm not ignorant. These posts are found in discussions of racism in BG3 and I would, again, prefer not to put a target on their back. Instead, show them support.

In terms of diverse storytelling, casting, and roles, I would only ask that a historical and sensitive look be applied. Hire people from these communities to act, direct, and write for that role. Writing is never easy. There is a weight and responsibility to it, but it's worth it to touch as many souls as possible.

I respect this history. That is why it is not something I believe should be thrown in as flavor text. It's why history needs to be respected as a great backstory to everything we create. We need each other, and we need art we create together.

The debt is yet to be paid.

#bg3#baldur's gate 3#bg3 critical#bg3 racism#larian racism#larian critical#my writing#astarion critical#astarion ancunin#astarion discourse#fandom racism#fandom critical#me@me IF IT WERE A CENTURY your own grandfathers wouldn't have given a shit#the word is “millenia”#and it is that horrifying

141 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Self-Aware Player of Harry Du Bois

It's fascinating to me to think about how satire is used as the 'touch grass' or 'be fucking for real' genre. Oftentimes it's making fun of tropes/conventions by humorously contrasting them with reality, which is exactly what Disco Elysium is doing with the RPG!

It goes hand in hand with the idea of RPGs as escapist power fantasy. RPGs are often thought of as the ultimate self-insert fantasy by its detractors or worst players, ahem looking at all those DND horror stories about entitled mangsty murderhobos.

One of the most infamous criticisms of Disco Elysium is its lackluster combat.

ID A screenshot of a random forum discussion post by dungeon master Zed Duke of Banville. It reads: "Disco Elysium has neither combat nor exploration, and therefore is missing two of the three fundamental components (or sets of components) that define the RPG genre." End ID

The game has essentially bordered off your ability to make Harry into a power fantasy murderhobo because you just are physically unable to equip an longsword or cuisse to murder your average citizen on the street of Martinaise.

But even on a less mangsty level, it subverts a lot of the basic expectations of RPGs.

Like the encounter with the racist lorry driver! You never get the ability or quest to change his mind, you only choose how you react to him.

Where other RPGs might let you act as the white savior or the white knight of chivalric romance, no questions asked, you're changing the minds of everybody who's wrong so we can all get along, Disco Elysium really makes you confront your ability to whiteknight, makes you confront if whiteknighting is even helpful, and why you wanted to whiteknight in the first place.

It’s part of the fun/humor experience of Disco Elysium that you at first expect to solve the world’s problems with a couple quests and lines of ‘good’ dialogue and then get socked in the faced with the fact that yeah, you can’t do much, you’re one person, what did you expect, asshole? Cuno doesn't fucking care!

By subverting our RPG expectations, it forces us to become more aware that these expectations even exist and how they fall short of reality. Yet, despite this subversion, the world of Disco Elysium feels so much realer to us.

ID a screenshot of Disco Elysium dialogue YOU - "Don't call it a dump, you've made it nice and cosy here." NOVELTY DICEMAKER - "Yeah." She stares out of the window, not really hearing your words. "Or maybe it's the entire world that's cursed? It's such a precarious place. Nothing ever works out the way you wanted." "That's why people like role-playing games. You can be whoever you want to be. You can try again. Still, there's something inherently violent even about dice rolls." "It's like every time you cast a die, something disappears. Some alternative ending, or an entirely different world...." She picks up a pair of dice from the table and examines them under the light. End ID

Like, Neha is highlighting this little meta element of how you can stack your Harry in any RPG to pursue a certain ending or situation, but the actual outcome is still influenced by a dice roll out of your control.

A lot of the satirical humor in Disco Elysium comes from the absurdity that you can do everything right or everything wrong, and the dice can still fuck it up or save it for you—not just for things like high-fantasy attacks, but mundane things like remembering your name.

The dice are, at their core, about how RPGs aren't just for the control fantasy, of winning high-fantasy battles, but also can represent life as it is, mundane and uncontrollable.

Similarly, Harry is clearly written—complete with all the 'lore' that this would entail—to couch his RPG protagonist nature in the real.

If RPG characters are blank slates? Let's give ours amnesia! Need fast travel?! Kim teases the 41st Precinct for constantly running everywhere by calling it the Jamrock Shuffle. He needs to have deep and intimate conversations with everyone, even when they're strangers? Yeah, that's so weird we gave him the name 'Human Can-Opener,' and everybody remarks on his uncanny manipulation skills.

It's commenting on difference between controlling an RPG avatar and navigating in a human body.

As Kurvits said: “In reality we do not have control, or complete control, of our minds. Just like our body, it is something that we give-not even commands wishes to, and we hope it's gonna do it. We hope it's not gonna break down, we hope it's not gonna rebel against us.”

In one type of RPG fantasy, we don't even question our total control and even assume the joy is from the control.

But in Disco Elysium, we lack control and find joy in it anyway. That is the fun of the game making us, the players, 'self-aware' about its RPG elements, and it especially resonates with anybody not able-bodied, anybody neurodivergent.

#disco elysium#metas#My thoughts#harry du bois#harrier du bois#human can-opener#jamrock shuffle#yeah so im reposting my meta because i worked really hard but i feel like it was too long for anybody to appreciate :')

367 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Flux/Series 13 was a super fun series. (fair warning; spoilers ahead)

Am I a fan of the fact we were starved for content for so long just to get 6 episodes and a few specials in like what 3 years? No. But the episodes we DID get were so great!

I could feel the intent to inspire wonder in the world-building of the Whoniverse again. I heard lines purposively written to punch out a few cheap laughs while moving the plot forward. These are things that are inherent to the legacy of Doctor Who. Whimsy, coy humor, and satire.

Where certain plot points had fallen short of expectation, it was clear Chibs had taken at least some of that feedback and applied it to making the 13th series a memorable one.

Also:

Karvanista! Who's a good boy?! 🤗 Wait, hold on, maybe that's too presumptuous. Who am I to judge anyone's moral status on appearance alone? 🤭

Such a fun character with a classic Doctor Who "secret backstory". On a deeper fan appreciation perspective, this series was and still very much is a sandbox for creative innovation.

The side characters we met in these 6 episodes felt so well established and grounded in the narrative. Eustacius Jericho facing his death in a poignantly heroic way, Vinder & Bel's love story, Dan's earnest appreciation of Liverpool (and most importantly history), heck even Claire was worth her salt as someone to revolve the story around.

Was she captivating? Well, we're talking about narrative structure here so *clearing throat; failing to hide obvious blushing* no? I mean, no. She's really just a vessel for the Weeping Angels to have a voice which makes for an interesting plot device but it also sidelines her own independent will in the story. Still, when that's a "weak point", you're doing well!

Also, Yaz was incredible and I felt like we were finally able to grasp at her individual companion status. Prior to the departure of "the fam", she was the prototypical companion choice but we were splitting time with Graham & Ryan. A common fear people had before the series came out was the inclusion of Dan Lewis being an obnoxious and obvious replacement for Graham... but I don't believe his presence in the story had that lasting effect.

In fact, I think of the scenes we had with Yaz, Eustacius, and Dan as being a time for Yaz to shine in particular as a leader. Clever, calm, and concerted in her efforts. Yaz's demeanor is the only reason that facet of the journey was successful. Her relationship with the Doctor was empowering in that way we impact others through positive experiences. She pushed herself to become more motivated as our time with her moved along and we were rewarded with a meaningful degree of success in her arc through this story.

Plus her love for the Doctor felt so real; so fated to be one-sided.

Rose's romantic attachment to 9/10 had the advantage of an entire plot built around her; elevating her importance to the Doctor as a being we came to know, for a time, as Bad Wolf.

With Yaz, she is, in fact, an ordinary human who doesn't get to have some immense cosmically significant role with a title that gets plastered across the whole of the universe for the Doctor to piece together like a puzzle. She is an incredibly smart and capable person; she is also mortal.

Say what have you about Yaz + 13 (and I have my opinions too of them never kissing) but the Doctor keeping a distance from Yaz while acknowledging her feelings was still rather intentional and thematically moving.

You learn you're this being known as "The Timeless Child" and you've lost innumerable lifetimes of memories while beings you encounter ON THE REGULAR are persistently trying to tear the universe like a chew toy for their pleasure? Sorry, love. Maybe attachment to a human isn't a wise choice after all...

It's a decision made in a moment and a moment is all Yaz & the Doctor have. It adds levels to the tragedy of a romance with such a being that can travel all of time and space.

"All of time and space but no room for me?"

-a line I may have written for Yaz before it was all over

🥹

Maybe I'll write some fan fiction one day around The Flux. Around 13 & Yaz. Maybe something with Karvanista & a version of the Doctor forgotten to time.

Anywho, I love this show. I love it for all it's many eras. I love it for many different reasons. I truly believe value can be had in finding those aspects of enjoyment even when one Doctor or one era speaks more to us individually because what does the opposite hold? What does boundless criticism of "the writing" ever truly amount to?

The internet is teeming with "expert opinions" on how Doctor Who should have been made after every new season but gods is it the rarest thing to find people who choose to love it for everything it has already been and everything it can always continue to be...

That's all from me for now, my lovelies. 💞 Take care, get a shift on, and snack on something that brings you a little joy. 🍪 Kisses.

#doctor who#thirteenth doctor#the flux#karvanista#eustacius jericho#yazmin khan#dan lewis#series 13#doctor who spoilers#creative writing#writing theory#fan fiction#fan fic writing#fan fic inspo#jodie whittaker#chris chibnall#mandip gill#scifi#bisexual#queer#queer joy#queer romance#lesbian#romance#lgbtqia#dw

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

Recently Viewed: Head

Star vehicles for musicians are hardly a rarity in Hollywood—after all, creatively bankrupt studio executives are perfectly willing to exploit pretty much any intellectual property that might be marketable, artistic integrity be damned—but even within that niche genre, Head stands out. Whereas A Hard Day’s Night (The Beatles) and True Stories (Talking Heads frontman David Byrne) are ultimately sincere and earnest despite their surface-level whimsy, the motion picture “adaptation”—more like antithesis!—of popular sitcom The Monkees is deeply cynical beneath its absurdist humor and psychedelic visuals, mercilessly deconstructing the superficiality of the entertainment industry, the elusive (and illusive) nature of the American Dream, and the manufactured public image of the band around which it revolves (exemplified by such sanitized, inoffensive lyrics as, “We’re too busy singing to put anybody down”).

The satire is as caustic as it is deliberately unsubtle. In an early scene, Micky Dolenz stumbles across a Coca-Cola vending machine in the middle of a barren desert—a condemnation of rampant commercialism and mindless consumerism that is subsequently reinforced by a rapidly edited montage of roadside billboard advertisements. Later, Peter Tork briefly breaks character mid-take to fret about how slapping a woman, even within the context of his work as an actor, might damage his reputation (“The kids won’t dig it, man!” he complains to the indifferent director)—lampooning the inherent egotism of celebrity. In the movie’s most scathing sequence, a concert is intercut with archival footage of the Vietnam War; as the performance ends, the frenzied audience storms the stage and literally tears the group apart—exposing them as nothing more than hollow mannequins. The medium itself can barely contain the filmmakers’ moral outrage: metafictional conflicts frequently disrupt the narrative; flashbacks within interludes within digressions overlap and interweave, making the “plot” borderline indecipherable. It can only be summarized in terms of its individual episodes and the loose thematic associations between them—which is akin to trying to explain a fever dream (or a drug-induced hallucination) to your pet cat.

Featuring cameo appearances by Jack Nicholson, Frank Zappa, and Timothy Carey and punctuated by stylistic flourishes that anticipate such cinematic classics as Raging Bull and Skyfall (no, seriously), Head is a fascinating countercultural artifact. Even amongst its New Wave contemporaries, it remains defiantly unconventional, incomprehensible, and unclassifiable; it must be experienced firsthand to be properly understood—though your mileage may vary in that regard.

#Head#Bob Rafelson#Jack Nicholson#The Monkees#Monkees#Davy Jones#Peter Tork#Micky Dolenz#Michael Nesmith#Frank Zappa#Criterion Collection#film#writing#movie review

50 notes

·

View notes

Note

Sorry this is a dumb question but can you explain why tomshiv is not abusive? Shiv seems to hit a lot of textbook behaviours of emotional abusers

thank you for your follow up clarifying this was in good faith bc i checked my inbox yesterday right after getting high and was like man come on. don't do this to me. but yeah i can talk about it, it's obviously something i have a fair amount of thoughts on

on a fundamental level, i take issue with the assertion that there are 'textbook behaviors of emotional abusers' in the first place. distilling abuse down to a set of behaviors is, imo, effectively meaningless and totally unproductive. it's not the behavior of an individual that defines abuse, it's a specific and intentionally cultivated imbalance of power and control within a relationship. victims of abuse can and do resort to survival mechanisms that could be considered in isolation as 'abusive behavior', the point is that you can't consider them in isolation. there's a gulf of difference between the same actions when they're coming from a person in a position of significant financial or physical or social power over someone else, or when they're coming from the person at a disadvantage.

i think viewing abuse as a set of behaviors also encourages you to treat interpersonal abuse as if it's discontinuous with systemic abuse, which is inaccurate and unproductive. a key part of succession's premise is that, because the family is literally the business, the familial abuse within the roy family is inextricable from the broader systems of capitalism, patriarchy, and the sexual violence and abuse endemic to them. with regards to how the show satirizes and critiques these systems, i think it's very telling that all of the characters are to some degree complicit and/or participants in abuse, but logan is the only one i'd say is unambiguously and intentionally presented as 'an abuser' (whose abuse is not an isolated product of him as a person, but integrated into/inseparable from the capitalist system which persists after his death). still, logan isn't reduced to a one-dimensional angry, abusive dad, he's given depth and complexity. his continued insistence that he loves his children isn't treated as something that's untrue, but that doesn't make it inherently good, and it certainly isn't incompatible with him abusing them.

circling back to tom and shiv. their relationship is unhealthy, it's not good for either of them to be married, shiv does fucking awful things to tom and tom does awful things right back, i'm not questioning any of that. but at my most cynical and bitchy, what it comes down to is quite simply: shiv doesn't have enough power over tom to be abusive, systemically or personally.

the thing is sometimes you see people say 'wow, if the genders were reversed people would say tom and shiv's relationship is unambiguously abusive!' which... hrm, but really the issue is that. the genders are the way they are, that's for a reason, and yes, that does make a significant difference in how we perceive their relationship and power dynamics. tom holds very real and present power over shiv as a man and as her husband, proposing to her when she was vulnerable in a way that placed huge pressure on her to accept and then trying to get her to have his baby so he can become patriarch. shiv's the heiress with the legitimacy of her family name and generational wealth but she is continuously, unavoidably subjected to gendered discrimination and violence. she's never allowed direct access to real power - she has to rely on the men around her, her husband or her brothers, and if they don't feel like humoring her she's shit out of luck.

this doesn't cancel out like a math equation, but it definitely makes things much more complicated than shiv being an Evil Bitch Wife to her Poor Pitiful Husband. when shiv finally does push tom too far, he immediately, successfully, goes over her head to her abusive father to fuck her over. maybe shiv wants to be her father in her relationships and exert the same kind of control he does. but she doesn't and she can't! she does not have that power! she cannot stop tom from kicking back and his hits are significant. as much as she might like to pretend otherwise, tom not only has always had the power to leave in a way shiv doesn't, he had and has the power to fuck her up badly, and he's used that power. that is simply not the power dynamic between abuser and victim to me.

i also have to say that abuse is not always going to be definitive black and white. in real life there are plenty of unambiguous situations but there are also plenty of complicated situations, and applying judgments to fiction is not always straightforward. i can't exactly call someone 'wrong' for personally being uncomfortable with tom and shiv's relationship or believing shiv is abusive, but i'm very skeptical of the viewpoint and the motivations or assumptions that are often contained within. if shiv is abusive, she definitely isn't uniquely so among the cast, so you had better be applying that label and any associated moral judgments equally across the board.

#mingbox#abuse mention#might self destruct this tag later but it's like.#my relationship with my ex was definitely unhealthy and fucked me up but it was not abusive because fundamentally.#he was actively worse to me than i was to him but the moment he went too far i cut him off and took all the friends in the divorce#if he had more influence in our social circle or could actually successfully emotionally manipulate me it would've been much worse#but he didn't so it wasn't. i won the idgaf wars and everyone liked me better because i am not an asshole so i peaced out.#he's a dickhead and i had to leave that relationship for my own good. still it was not abusive#chalkboard

152 notes

·

View notes

Text

Now let’s do similarities between some of the themes of The Bear and Twin Peaks and other things from the 90s.

Mikey the “life of the party” was everyone’s best friend like Laura Palmer but was harboring dark secrets.

Generational abuse and mental illness “haunting” families is a frequent topic with characters like Laura and Audrey Horne wanting to run away from home/escape. Many of the young characters in the show feel this way.

A dark underbelly present under the veneer of All-Americanism and a very present class structure that is hinted to be driven by capitalism and colonialism with the lumber mill (run by a matriarch) and the Black Lodge (being stuck/dopplegangers and alter egos - Logan, Claire, the walk-in, “prisons of your own design”, etc.).

Wealthy family members involved in illicit activities who are looked at as benefactors and respectable citizens of the town but really pull the strings like Ben Horne (Cicero).

The Log Lady who seems absurd on the surface but appears periodically to drop truths like an oracle (Faks).

The absurdist humor/tragicomedy, because Twin Peaks in the 90s was a satire of soap operas, but talking about lots of other things. Similarly The Bear could be viewed as a satire, which was hinted in S3 (fictional character played by Bradley Cooper’s image from Burnt shown at the Ever’s funeral dinner) among other things.

Characters in Twin Peaks break the Fourth Wall in the Black Lodge, similar to Richie in S3 when he’s on the playground bench with Tiff and they appear to talk about knowing their real audience. Also the presence of many real-life chefs who point out inherent problems with fine dining while still participating in it and being celebrated. Restaurant reviewers mentioned include a real-life critic/influencer and major newspapers.

Twin Peak’s creator, David Lynch, is also very influenced by Shakespeare in his works, just like Jane Austin was (my previous comparisons of The Bear to Pride and Prejudice).

Lynch has said that he uses his art to broadcast his subconscious conjurings, similar to how Hamlet transmits his bad dreams outwards. He also loves Oedipal shit.

The Bear is, in some ways, part Carmy’s waking big bad dream (S3 for sure) about family legacy.

Twin Peaks came out in the 90s aligning with many of Storer’s influential musical choices like REM (very popular before they broke up in the 90s), Pearl Jam, and Trent Reznor (NIN) @whenmemorydies did a dive into this. The very popular BBC tv adaptation of Pride and Prejudice with Colin Firth came out in 1995.

Syd and Carmy could also be described as similar to The X-Files’ Mulder and Scully where they are both professionally dedicated which is the cause of their introduction with Scully being more academic in nature. Both are haunted in different ways related to their childhood/families; Mulder has a missing sibling that drives him. Scully is very connected to her father. They appear to be in opposition at times but are completely dedicated to one another and fall in love despite all attempts from outward opposition and even other love interests.

I’m sure there are others that I’m missing so anyone feel free to jump in.

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Title: “Scarecrowds: The Harvest”

👁️⃤X 𝔪𝔦𝔵𝔢𝔡 𝔪𝔢𝔡𝔦𝔞 𝔭𝔬𝔰𝔱-𝔞𝔯𝔱

“Fantasies are regarded by humans as NOT real. They are blind and senseless. They waste their true potential by living a life that arrogantly rejects and dismisses the fact that, to begin with, reality establishes the conditions for these fantasies to manifest as definitive REAL actions inherent to reality itself.” (𝘼𝙣𝙤𝙣𝙮𝙢𝙤𝙪𝙨 𝙎𝙘𝙖𝙧𝙚𝙘𝙧𝙤𝙬𝙙)

This is the 2nd illustration of my new post-art series: "Scarecrowds". The description of the series goes as follows: “The series is a dark fantasy and surreal-gothic mixed media post-art series that began on Halloween Eve, 2024. In gothic culture, crows are powerful and multifaceted symbols, often representing darkness, mystery, and a connection to death or the supernatural. This series playfully keeps out not crows as scarecrows do, but the dull and regulatory conceptual box labeled "Humans," especially when it comes to crowds. It celebrates the magic of animatronic "scarecrowds" and their warm-hearted, whimsical and non-human worlds, though not without a certain dose of fun, irony, satire, and dark humor. They have such big, warm hearts, but you do not want to know them when they detect a situation that is too human-centered. Beware.”

I’m publishing all my images on my OpenSea page, on my Website and across social media. Today I will start by publishing them also on my Youtube Channel. Please visit! Links in bio. TYVM @ofb1t

◐𐍆ᛒ1𝚪 (҂0_✘)

#darkfantasy #darkwave #darkart #gothgoth #gothicart #goth #gotico #gothicstyle #halloween #halloween2024 #gothaesthetic #gothic #illustration #surrealism #artoftheday #art #fyp #fypシ #foryou #parati #animecore #otaku #animatronic #scarecrow #animeart #ai #digitalart #fantasy #dark #ofb1t

#darkfantasy#darkwave#darkart#gothgoth#gothicart#goth#gotico#gothicstyle#halloween#halloween2024#gothaesthetic#gothic#illustration#surrealism#artoftheday#art#fyp#fypシ#foryou#parati#animecore#otaku#animatronic#scarecrow#animeart#ai#digitalart#fantasy#dark#ofb1t

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Double ep 6-7

I'm impressed with this adaption's choices. Instead of proceeding with all the cliches of the ep 6 chapters from the novel, turns them a bit on their head with 'it COULD have played out this way' and gives the sister some human depth. There's a lot of blatant misogyny in what this author writes and it's not all necessary to the story.

The way the narrative sees the inherent humor in the OTT antics of the characters, but it feels like a warm humor (it's laughing with the audience and with book readers instead of looking down patronizingly).

Weaving in some light satire into the narrative was a smart choice. That arranged marriage showdown scene was a lot of fun. I'm a fan of the actor who played her 1st marriage prospect - he has great comedic timing when given supporting roles. Loved him in Dream of Splendor.

Scholar Shen and FL's fraught relationship is much more interesting than I expected. He even digs up her muddy grave in hysterics !!!

I have no idea what is going on with ML's politics plot, nor do I particularly care. Luckily, novel author & drama screenwriter seem to agree. Just here for the vibes, thanks bb.

Hope we can make it through the school talent show plot by ep 10.

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

One very interesting to note when comparing the "literary" fairytales and the "folkloric" fairytales - the fairytales actually rewritten or entirely written by authors for a literate public versus the oral folktales and "countryside" or "simple folks" fairytales collected by folklorists.

The latter tend to be very conservative, the former much more progressive than you think. Or rather... when you've got crazy nationalist and xenophobes and discriminators of all kinds, they'll turn towards the "folkloric" fairytales - but when you want to research queer, society-questioning, gender-norms-breaking, eerily modern fairytales, you'll go with the literary fairytales rather.

Don't get me wrong, do NOT get me wrong - both kind of fairytales are usually very racist in one way or another because they are from ancient times. The Pentamerone, madame d'Aulnoy's fairytales and the brothers Grimm fairytales all are very not-Black-people-friendly and always depict having dark skin as being ugly, being wicked or being a laughingstock. Because they were written by Renaissance-era Italians and French people, and by 19th century German men, so casual racism is just there.

BUT... Folkloric countrysides tend to play the cards of the casual European racism, and the common antisemitism, and the ingrained misogynistic views, much more plainly, openly and directly, because they were literaly collected among the folks that thought that, among the common population with the "common" views of the time. For example in a lot of French folkloric fairytales (not reprinted for children today) the role of the ogre or the devil or the murder in the woods will often be "the Moor" or "the Mooress", because it was okay to depict Moors are humanoid, devilish monsters used to eat the flesh of Christian children. The casual racism and antisemitism in good handfuls of the Grimm fairytales also prove the point (NOT HANSEL AND GRETEL THOUGH! I think I made my point clear). And the same way, in the Grimm you have the absolute "heterosexual-happiness" structure that was reinforced by Disney movie and is the reason why people think fairytales are inherently homophobic.

However, when it comes to literary fairytales, you have an entirely different song. Because they were LITERARY works, and as with a lot of literature pieces, you often get more progressive things than you think. Everybody knows of Andersen's fairytales queerness today that make them beautiful allegories for things such as coming out of the closet or transitioning or living in an homophobic setting, but if we take less "modern" and "invented", more traditional fairytales, we can be in for quite a surprise...

Take the Italian fairytales classics - the Pentamerone and the Facetious Nights. These works were originally satirical and humoristic adult works. Crude satire, dark humor - they were basically the South Park of their time. Slapstick gore out of an Itchy and Scratchy show, very flowery insults the kind of which you except to come of a Brandon Rogers video, poop and piss everywhere (yet another common trait with Brandon Rogers video, in fact I realized the classic Italian literary fairytales have actually a LOT in common with Brandon's videos...), and lot of sexual innuendos and jokes involving the limits of what was accepted as tolerable (extra-marital affairs, homosexuality, incest, gerontophilia, zoophilia). This was one big crude joke where everybody got something for their money and everyone, no matter the skin color, the religion, the gender or the social status, got a nasty little caricature. It does come off as a result as massively racist, antisemitic, ageist and misogynistic tales today... But it also clearly calls out the bad treatment of women, and takes all kings for fools, and completely deconstructs the "prince charming" trope before it even existed because they're all horny brutes, and it encourages good people to actually go and KILL wicked people who abuse others and commit horrid deeds... These tales inherited the "medieval comedy style" of the Middle-Ages, where it was all about showing how everybody in the world is an asshole, all "goodness" and "purity" is just foolishness and hypocrisy, how the world is just sex and feces, and how everybody ended up beaten up in the end.. (See the Reynard the Fox stories for example - which themselves spawned an entire category of "animal fairytales" listed alongside traditional "magical fairytales" in the Aarne-Thompson Catalogue.

But what about the French classical literary fairytales? Charles Perrault, and madame d'Aulnoy, and all the other "précieuses" and salon fairytale authors - mademoiselle Lhéritier, madame de Murat, the knight of Mailly, Catherine Bernard, etc etc...

The common opinion that was held by everyone, France included, for a very long tale, was that their fairytales were the "sweet and saccharine-crap and ridiculous-romance" type of fairytales. They were the basis of several Disney movies afterall, and created many of the stereotyped fairytale cliches (such as the knight in shiny armor saving a damsel in distress). People accused these authors - delicate and elegant fashionable women, upper-class people close to the royal court and part of the luxurious and vain world of Versailles, "proper" intellectuals more concerned with finding poetic metaphors and correct phrasing - they were accused of removing the truth, the power, the darkness, the heart of the "original" folkloric fairytales to dilute them into a syrupy and childish bedtime story.

But the truth is - a truth that fairytale authorities and students are rediscovering since a dozen of years now, and that is quite obvious when you actually take time to LEARN about the context of these fairytales and actually read them as literary products - that they are much more complex and progressive than you could think of. Or rather... subversive. This is a word that reoccurs very often with French fairytales studies recently: these tales are subversive. Indeed on the outside these fairytales look like everything I described above... But that's because people look at them with modern expectations, and forget that A) fairytales were generally discredited and disregarded as a "useless, pointless child-game" by the intellectuals of the time, despite it being a true craze among bookish circles and B) the authors had to deal with censorship, royal and state censorship. As a result, they had to be sly and discreet, and hide clues between the lines, and enigmas to be solved with a specific context, and references obscure to one not in the known - these tales are PACKED with internal jokes only other fairytale authors of the time could get.

These fairytales were mostly written by women. This in itself was something GRANDIOSE because remember that in the 17th century France, women writing books or novels or even short stories was seen as something indecent - women weren't even supposed to be educated or to read "serious stuff" else their brain might fry or something. Fairytales were a true outlet for women to epxress their literary sensibilities and social messages - since they were allowed to take part in this "game" and nobody bothered looking too deep into "naive stories about whimsical things like fairies and other stupid romances".

But then here's the twist... When you look at the lie of the various fairytale authors (or authoresses) oh boy! Do you get a surprise. They were bad girls, naughty girls (and naughty boys too). They were "upper-class, delicate, refined people of the salons" true. But they were not part of the high-aristocracy, they usually were just middle or low nobility or not even true nobility but grand bourgeois or administrative nobility - and they had VERY interesting lives. Some of them went to prison. Others were exiled - or went into exile to not be arrested. You had people who were persecuted for sharing vies opposing the current politico-status of France ; you had women who had to live through very hard and traumatic events (most commonly very bad child marriages, or tragic death of their kids). And a lot of them had some crazy stories to tell...

Just take madame d'Aulnoy. Often discredited as the symbol of the "unreadable, badly-aged, naive, bloated with romance, uninteresting fairytale", and erased in favor of Perrault's shorter, darker, more "folkloric" tales - and that despite madame d'Aulnoy being the mother of the French fairytale genre, the one that got the name "fairytale" to exist in the first place, and being even more popular than Perrault up until the 19th century. Imagine this so called "precious, delicate, too-refined and too-romantic middled aged woman in her salon"... And know that she was forced into a marriage with an alcoholic, abusive old man when she as just a teenager, that things got so bad she had to conspire with family members of her (and some male friends, maybe lovers, can't recall right now) to accuse her husband of a murder so he would get death sentence - but the conspiracy backfired, madame d'Aulnoy's friends got sentenced to death, and she had to exile herself it her mother in England to not get caught too. And she only returned to France and became known as a fairytale writer there after many decades of exile in other European countries the time the case got settled down. Oh, and when escaping France's justice she even had to hide under the frontsteps of a church. Yep.

Now I am reciting it all out of memory, I might get some details wrong, but the key thing is: madame d'Aulnoy was a woman with a crazy criminal life, and in fact she got such a reputaton of a "woman of debauchery" the British people reinvented her and her fairytales around the folk/fairytale figure of Mother Bunch (Madame d'Aulnoy's fairytales became "Mother Bunch" fairytales in England to match Perrault's "Mother Goose" fairytales, and Mother Bunch was previously in England a stereotype associated with the old wise woman, kind of witchy, that girls of the village went to to get love potions and aphrodisiacs or some advice on what to do once in bed with a guy - think fo Nanny Ogg from Discworld).

And many other fairytale authors of this "classical era of fairytales" had just as interesting, wild or marginal lives. The result? When you look at their tales you find... numerous situations where a character has to dress up and pass off as the opposite gender, resulting in many gender-confusing emotion and situations just as queer as Shakespeare's Twelfth Night. Several suspiciously close and intimate friendships between two girls or two men. Various dark jokes at all the vices and corruption underlying in the "good society". Discreet sexual references hinting that there's more than is told about those idyllic romances. And lots of disguised criticism of the monarchic government and the gender politics of the society of their time - kings being depicted as villains or fools, princes either being villains or behaving very wrongly towards women, many of the typical fairytale love stories ending in tragedies (yes there's a lot of those fairytales where, because a prince loved a princess, they both died), numerous courtly depictions of rape and forced and abusive marriages, and of course - supreme subversion of all subversions - people of lower class ending up at the same level as kings (Puss in Boots' moral is that all you need to be a prince is just to look the part), and other mixed-class marriages (which was the great terror of the old nobility of France, for whom it was impossible to marry below their rank - if a king married a common peasant girl, the Apocalypse would arrive and it was the End of times).

So yeah, all of that to say... All the literary fairytales I came across with had subversive or progressive elements to it ; and this is why they are generally so easier to adapt or re-adapt in more queer or democratic or feminist takes, because there's always seeds here and there, even though people do not see it obviously. Meanwhile folkloric fairytales tend to be much more conservative and reflective of past (or present) prejudices, but people tend to forget it because these stories simple format and shortness allows them to "break" into pieces more easily like Legos you rearrange.

All I'm going to say is that there's a reason wy the Nazis very easily re-used the Grimm brothers fairytales as part of their antisemitic and fascist propaganda ; and why Russian dictators like Putin also love using traditional Russian fairytales in their own propaganda, while you rarely see Italian or French political evils reuse Perrault, d'Aulnoy, Basile or Straparole fairytales.

#fairytale analysis#fairy tales#fairytales#literary fairytales#folkloric fairytales#french fairytales#madame d'aulnoy#d'aulnoy fairytales#brothers grimm#grimm#queerness in fairytales#subversion in fairytales#queer fairytales#racism in fairytales#antisemitism in fairytales#politics and fairytales

30 notes

·

View notes

Note

DON’T FILE THOSE DIVORCE PAPERS. but i thought emma was boring i desperately need ur full take geek out plz tell me what I don’t see

i would NEVER divorce you pookie??

(us actually)

everyone gets film freaky in their own way!!! its ok!!!

two film essay posts in less than 24 hrs by ro, someone needs to sedate me or something

( sort of spoilers for emma (2020) under the cut , but nothing explicit , really )

!!! disclaimer i think to really fw regency-ish movies, kind of inherently calls for being into things like their original source material. and trust!! i know its not for everyone!!!

personally, i'm actually a big fan of reading those old and classical kind of books. as in, i have a full, clothbound, BOX SET, of jane austen's novels (emma being one of them). my literature teacher recommended me to read pride and prejudice ONCE and i've been hooked ever since.

yknow people joke that back then that it was all "oh my god you can't show your ankles!!!" and yeah, that's pretty much what it's like when you get down to reading novels from that time 😭 but that's what makes it so entertaining for me! the bridgerton series (which i also really like by association) is an easy example of this. i once saw someone say bridgerton plays out like a kdrama and YES!! that's the level of yearning and pining and slow burn i feed off of

upfront, i liked the movie–even from when its first trailer came out–because its aesthetics visually were just so nice. like yes!!! pastels!! pretty flowers!!! hats with feathers!! tea parties!!! big poofy dresses!!! (and anya taylor joy)

but it was when i watched it for a second time, i found a lot of why i like this specific adaptation of emma is because i think it really got across the vibe of jane austen's writing–especially the humor.

ok now stay with me: i'm not saying you have to read the whole original novel to get it, bc basically i would summarize the reason why the humor is so dry (when usually you would think this rich and old-fashioned vibe of a story should be much more over-the-top and dramatic) is because jane austen was always trying to make fun of all the social constructs of her time. especially for women! (heavy on how her works were ones of satire!)

like it all plays out so bare-bones that you just can't ignore how ridiculous everything sounds, which is what austen felt about all the rules and expectations emma and the other characters were trying to uphold the whole story. i also find that kind of humor from the movie very charming in a simple way, too.

the whole vibe of watching the movie and its characters is very much unserious, and it's a personal favorite in that watching it and listening to the soundtrack makes me feel ok to wallow in my emotions like the characters do. it's very cathardic in that way to me. but yeah by no means is it very action-packed or even conventionally "dramatic", so i get how it can wind up boring.

the character development of emma is always so interesting to me though. it's subtle, especially on the first watch, but it always warms my heart when she goes from thinking she's got everything figured out, to seeing the value of true friendship in harriet and even mrs. bates (MY FAV CHARACTER I CANNOT LIE SHE'S SO FUNNY), and that making her more open to questioning her and her life more, including not being as perfect as she once thought she was.

and that's really why we get that payoff with her and knightley, because he's known her all this time but when she finally recognizes her imperfections and embraces them, that newly found self-awareness us what pushes him over the edge in love. then we get that BEAUTIFUL confession scene under the tree. 🤭🌳

it very much fits the genre of a "romantic" movie, in that it romanticizes everything. but not to the point where it lets you forget what everyone's wants were, and that there were genuine struggles grappling with all those societal rules at the same time.

bc at the end of the day those rules were efforts meant to promote values that could hopefully lead a life of morality, responsibility/duty, and respect to others and yourself (arguably there are rules we face today that try to promote the same things, but they just look much different than rules about showing your ankles lol). i think in emma it's interesting to see just how each character tries to navigate those rules to get what they want out of life from them, and i think it's just a very beautifully-made film overall as well.

#🍃 𝗿𝗼 𝗴𝗲𝘁𝘀 𝗳𝗶𝗹𝗺 𝓯𝓻𝓮𝓪𝓴𝔂#i’m embarrassed to admit how many times i’ve watched this movie#definitely in the double digits thats for sure#emma 2020#jane austen

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

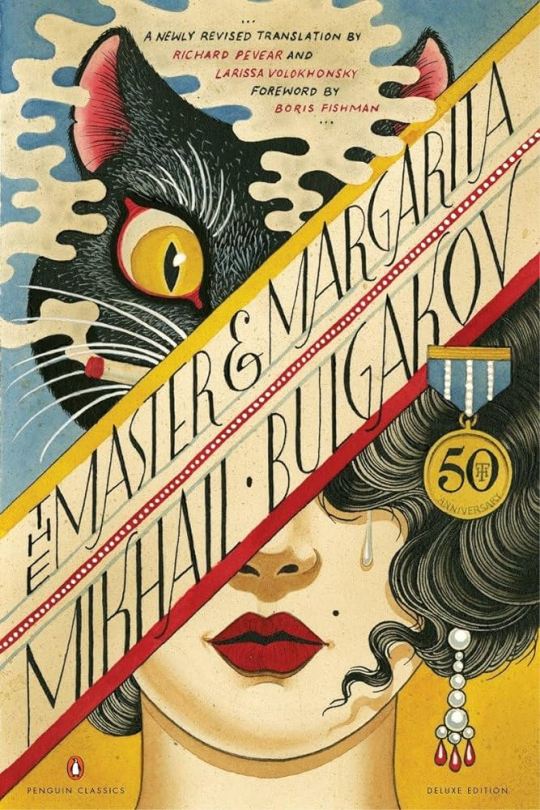

[REVIEW] The Master and Margarita by Mikhail Bulgakov

3/5 stars (★★★)

"He does not deserve the light, he deserves peace."

This was an oddly enjoyable read for the Christmas season. Before I read The Master and Margarita, I had zero idea what the book was about and 412 pages + a lot of reviews later I still can't exactly say what even happened here. The Gogolian influence was very persistent in Bulgakov's prose, so I highly recommend reading some of Nikolai Gogol's stuff before getting into TMaM. That being said, I agree with people that it's a novel that stands on its own in spite of its heavy context. I did some background research into Bulgakov's biography, the ten-ish years it took for him to write the book, Stalinist Russia, and the 25-year gap between when he finished the manuscript (which don't burn!) and the actual publication of it after his death. Critics seem to be unanimous in agreeing that the Master is a self-insert of Bulgakov himself, which I really felt to be most fitting during the scenes in the hospital where he discussed with Ivan the Homeless his philosophies on art and the current social order. I appreciated Bulgakov's harrowing criticism on Soviet Russia without actually being too grave about it; the dark humor is good because the "dark" is the adjective that informs the noun, not vice versa like a lot of "satire" plots which I feel fail in comparison. The magical realism was a good kind of wacky (although I wouldn't exactly call it magical realism, but that may be just because I'm more used to its South and Latin American literary uses). I liked Woland and all the beheading episodes. Bulgakov's tongue-in-cheek treatment of citizens "disappearing," private executions, political censorship of the Soviet intelligista, and the air of general repression felt in all people, especially artists, during the time were spot-on (though that's coming from someone who never experienced Stalinist Russia and have only done humble research into it). I think TMaM is a great testament to the political and social climate of Russia in the 20th century. Bulgakov captured everything so well whilst still retaining a sense of wonder, folkloric absurdism, and, at times, tender humanity.

Personally, I didn't like the scenes set in Yershalaim with Pontius Pilate and Yeshua Ha-Nozri, though I appreciate their symbolic meaning and narrative weight as a whole. I honestly found myself falling asleep, especially during the infamous conversation between Pilate and Jesus. That being said, I found Bulgakov's portrayal of Jesus very intriguing, as well as his decision to refer to ancient Jerusalem by an alternate transliteration from the Hebrew quite bold. It gave a sort of distancing effect to the otherwise well-known Biblical places that separated their religious (over)-associations with actual historic (and fictionalized) context. I like that Jesus became "Yeshua," with the name obviously coming from the Aramaic word for "the Lord is salvation." Bulgakov making Jesus' last name "Ha-Nozri" meaning "of Nazareth" specifically was quite beautiful to me, as it places him as coming explicitly coming from the town of Galilee (north of Palestine), which Jesus was said to have lived in before he began his ministry. Instead of "Jesus Christ" or "King of Israel," which are common ways he is referred to, Bulgakov opted to name him according to his native Palestinian roots first and foremost. There's a lot of literary analysis you can take from that, but it's inherently a very defiant decision that I appreciate Bulgakov for making, and I'm saying that as a reader in 2024. Bulgakov, amongst other subtle cultural references, also mentions the keffiyeh ("kefia") in his novel a handful of times, most strikingly in the scene when Matthew Levi essentially curses at God because he was too late saving Yeshua from crucifixion. Bulgakov here is writing almost 100 years ago from where I am with zero idea of the political climate happening now in my world (although Zionism was still obviously present in early 20th century Russia). Matthew Levi's keffiyeh was one of the book's most resonant images for me, even if Bulgakov didn't exactly intend it to be as jarring as it is since he couldn't have predicted the genocide happening in Gaza right now. However, this small link I've noticed between the past and now is just an example of literature transcending time and space by acting as a bridge for human connections. Long ago, one man from Palestine disrupted Jerusalem and Rome's established (tyrannical) order and then centuries later a writer in early 20th century Russia adapted Jesus' story to criticize the cruelties and ridiculousness of the Stalinist regime, and then I in 2024 am reading this as the mass killings are happening in Palestine. Through this one book, three generations -- three timelines -- are somehow connected.

My final comment is that TMaM, particularly that connection I've personally drawn as a modern reader, reminds me why humanities, reading, history, literature, the arts, etc. are so timelessly and universally important. I know I may sound crazy and "you're just trying to be deep," but it really honestly is the truth. Bulgakov explicitly highlighting Jesus as Palestinian in Soviet Russia as a form of political protest and me in 2024 reading this book just as Jesus' same homeland is being massacred during Christmastime ... it's so haunting. The book being finished in 1940, meaning it and Bulgakov's very Palestinian Jesus is older than the "state" of Israel is an even more damning fact in and of itself. Even though I gave the book 3/5 stars, it's surely a story I will remember. That final image of the four "horsemen" riding off into the distance just as another dawn is breaking over a dictatorial empire history knows is doomed to crumble that concludes the novel will stay with me.

#mikhail bulgakov#bulgakov#the master and margarita#russian literature#literature review#book review

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Crypto Wealth Building A Guide for Gen Z

Who is Andrew Tate?

Understanding Memecoins

Memecoins have gained significant popularity in the world of cryptocurrencies, attracting a new wave of investors, especially among the younger generation like Gen Z. Let’s delve into what memecoins are and how they differ from traditional cryptocurrencies.

Definition and Explanation of Memecoins

Memecoins are a type of cryptocurrency that primarily relies on humor, memes, and community engagement to gain value and traction in the market. Unlike traditional cryptocurrencies such as Bitcoin or Ethereum, which are based on underlying technology and blockchain functionality, memecoins derive their value from internet culture and trends. They often represent a joke or satirical concept that resonates with a specific online community.

How Memecoins Differ from Traditional Cryptocurrencies

While both memecoins and traditional cryptocurrencies use blockchain technology, their fundamental differences lie in their purpose, value proposition, and community-driven nature. Traditional cryptocurrencies aim to revolutionize finance by providing decentralized alternatives to traditional banking systems. In contrast, memecoins serve as a form of entertainment or social commentary within the crypto space. Their value is driven by community engagement rather than technological advancements or real-world utility.

Examples of Popular Memecoins in the Market

Several memecoins have gained significant attention and market capitalization. One notable example is Dogecoin (DOGE), which originated as a joke but has since become one of the most well-known memecoins. Another popular memecoin is Shiba Inu (SHIB), inspired by the Dogecoin phenomenon. These coins have experienced massive price surges due to viral trends and influential endorsements.

Memecoins offer an exciting alternative investment opportunity for Gen Z investors looking to explore the crypto space. Understanding their unique characteristics and how they differ from traditional cryptocurrencies is essential for making informed investment decisions.

Andrew Tate’s Advice on Memecoins

Andrew Tate, a prominent figure in the world of entrepreneurship and wealth building, has shared valuable insights into the realm of memecoins and their potential as an investment avenue for individuals. His perspective on investing in memecoins is characterized by strategic approaches and risk management techniques that can benefit investors looking to explore this unique market.

Overview of Andrew Tate’s Perspective

Andrew Tate views memecoins as an innovative and potentially lucrative investment opportunity within the crypto space. His approach emphasizes the significance of identifying promising memecoin projects with strong fundamentals and community support.

Strategies for Identifying Profitable Memecoin Investments

Tate advocates for thorough research and due diligence when considering memecoin investments. He highlights the importance of assessing the underlying technology, development team, and community engagement to gauge the long-term viability of a memecoin project.

Tips for Managing Risks Associated with Memecoin Investments

Recognizing the inherent volatility of memecoins, Andrew Tate advises investors to exercise caution and prudence in their approach. Setting clear entry and exit strategies, diversifying investment portfolios, staying updated on market trends, and identifying potential breakout candidates such as the next big cryptocurrency set to explode in 2024 are among the risk management practices he recommends.

By aligning his insights with practical investment strategies, Andrew Tate offers a comprehensive perspective on navigating the dynamic landscape of memecoins while prioritizing informed decision-making and risk mitigation.

The Role of Memecoins in Crypto Wealth Building for Gen Z

How Memecoins Can Help Gen Z Build Wealth Through Crypto Investments

Memecoins have become popular among Gen Z investors because they have low barriers to entry and can potentially generate high profits. Unlike traditional investment options, memecoins usually have lower fees for transactions and can be easily accessed through various online platforms. This makes it possible for young investors to enter the cryptocurrency market with a smaller initial investment, which is appealing to those who want to start building wealth at a younger age.

Furthermore, memecoins offer a sense of community and inclusivity that resonates with many Gen Z individuals. The social aspect of memecoins can create a supportive environment for learning about investing and financial literacy, empowering young adults to take control of their financial future.

The Potential for Long-Term Financial Growth Through Memecoin Investments for Young Investors

Memecoins present an opportunity for long-term financial growth for Gen Z investors. While they may be considered more volatile than traditional cryptocurrencies, some memecoins have shown significant increases in value over time. By carefully choosing and diversifying their memecoin portfolio, young investors can position themselves to benefit from potential long-term growth and take advantage of emerging trends in the crypto market.

As digital natives, Gen Z individuals are well-suited to adapt to the changing world of cryptocurrency and blockchain technology. Embracing memecoins as part of their wealth-building strategy can give them practical experience in navigating the digital economy while also potentially earning substantial profits in the future.

The Intersection of Memecoins and AI: A Survival Strategy for Bitcoin Miners

While memecoins offer financial opportunities for Gen Z, it’s important to note that the crypto landscape is ever-evolving. In fact, some forward-thinking Bitcoin miners are exploring AI as a survival strategy in response to certain challenges like the halving event. This intersection between memecoins and AI signifies the growing importance of technological innovations in the cryptocurrency industry. By staying informed and adaptable, young investors can navigate these shifts and continue to thrive in the crypto market.

Getting Started with Crypto Wealth Building as a Gen Z Investor

When it comes to starting your journey of crypto wealth building as a Gen Z investor, there are several important things to think about and tactics that can help you get on the right track. Here’s how you can get started:

1. Educate Yourself

Take the time to understand the basics of cryptocurrencies and blockchain technology. There are many resources available, such as online courses, articles, and forums where you can learn more.

2. Diversify Your Portfolio

Instead of putting all your money into just one cryptocurrency, think about spreading your investments across different assets. This can lower the risk and improve your chances of long-term success.

3. Stay Informed

The cryptocurrency market is always changing, with new things happening all the time. Stay up-to-date with the latest news, market analyses, and expert opinions to make smart investment choices.

4. Manage Risks

It’s important to know how much risk you’re comfortable with and set clear investment goals. Don’t invest more money than you can afford to lose and consider using strategies like stop-loss orders to protect yourself.

5. Find a Mentor

Look for experienced investors or mentors who have done well in the world of crypto wealth building. Their advice and guidance can be really helpful as you start your own investment journey.

By thinking about these things and using these tactics, Gen Z investors can build a strong foundation for their crypto wealth building efforts. With a proactive attitude and a commitment to always learning, it becomes more possible to see financial growth through cryptocurrencies.

Embracing the Future: Why Gen Z Should Explore Crypto Wealth Building Opportunities

As a member of Generation Z, you have the chance to lead the way in technological innovation and shape how financial markets will look in the future. Here’s why it makes sense for you to consider getting into crypto wealth building:

1. Technological Proficiency

Gen Z is known for being comfortable with technology, which puts you in a good position to understand and navigate the world of cryptocurrencies and blockchain. Getting involved in crypto wealth building is a natural fit for your tech-savvy nature.

2. Financial Empowerment

Investing in crypto gives you the power to take charge of your own financial destiny. Instead of relying solely on traditional methods, like saving money or investing in stocks, you can actively seek out opportunities that have the potential to grow your wealth over time.

3. Innovative Mindset

One of the key strengths of your generation is its ability to think outside the box and come up with fresh ideas. By embracing crypto wealth building, you’re not only tapping into an exciting new asset class but also contributing to the ongoing transformation of how money works.

4. Global Perspective

Unlike traditional financial systems that are tied to specific countries, cryptocurrencies operate on a global level. This means that by exploring crypto wealth building options, you can gain exposure to international markets and stay informed about global economic trends.

Embracing crypto wealth building isn’t just about making money; it’s about embracing a mindset of progress, empowerment, and adaptability — qualities that resonate deeply with Generation Z’s values.

Conclusion

As Gen Z individuals, embracing the world of crypto wealth building can have a significant impact on your financial future. The potential for long-term growth through investments in cryptocurrencies, including memecoins, presents a unique opportunity for young investors to secure their financial well-being.

Andrew Tate’s valuable advice on memecoins aligns with the overall guide, emphasizing the importance of strategic investment approaches and risk management. His expertise in entrepreneurship and wealth building serves as an inspiration for Gen Z to explore the world of crypto investments with confidence.

Thanks for reading Article, Also we done tons of research and found this amazing platform solanalauncher.com For you... Here you can generate your own memecoins tokens on solana in just less than three seconds without any extensive programming knowledge, There support is too good for clients, and also you aware about solana blockchain, It's fastest growing blockchain compare to other crypto blockchain.

By staying informed, adopting a proactive mindset, and leveraging the guidance available, you can position yourself to thrive in the evolving landscape of crypto wealth building. Remember, the decisions you make today can pave the way for a prosperous tomorrow.

Happy Investing!

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Distorted Reflections: Plastic Man, Fragmented Identity, and the Politics of Absurdity

Abstract

Plastic Man, with his exaggerated elasticity and irreverent humor, transcends the boundaries of traditional superhero narratives to become a profound critique of modern identity and adaptability. This thesis examines the Eisner Award-winning Plastic Man comic as a satirical exploration of the pressures of contemporary socio-political systems, where individuals are compelled to constantly adapt and reshape themselves to meet external demands. By dissecting Plastic Man’s shape-shifting powers, the analysis delves into the fragmentation of selfhood in a postmodern world, exploring themes of authenticity, autonomy, and the costs of perpetual flexibility. Through the lens of cultural theory, postmodern philosophy, and narrative analysis, this study positions Plastic Man as an embodiment of the grotesque paradoxes of modernity—a figure of both resilience and absurdity who mirrors the fractured realities of contemporary existence. In a world obsessed with spectacle and fluidity, Plastic Man becomes a symbol of survival at the expense of stability, a satirical mirror reflecting the disjointed nature of modern life.

Introduction:

Plastic Man, the rubber-limbed anti-hero, epitomizes the intersection of resilience and absurdity in a world obsessed with fluidity and spectacle. The Eisner Award-winning Plastic Man comic, often dismissed as mere humor, uses its protagonist’s shape-shifting powers to critique the elasticity demanded by contemporary socio-political systems. In a reality where individuals are urged to “adapt” at all costs, Plastic Man’s grotesque flexibility mirrors the pressures placed upon modern identity, where selfhood is fragmented and reshaped by social, economic, and political forces. In this extended analysis, we will explore how Plastic Man embodies the fractured postmodern self, serving as a satirical lens for examining authenticity, autonomy, and the costs of flexibility.

Section 1: Plasticity and the Fragmented Self in the Modern Age

In modern political and social discourse, “plasticity” has evolved beyond its physical connotations to represent adaptability, psychological resilience, and ideological flexibility. Philosopher Catherine Malabou’s concept of “neuronal plasticity” in What Should We Do With Our Brain? argues that modern society demands an internal plasticity—a forced adaptability that echoes through the personal, social, and professional realms (Malabou, 2008). Plastic Man’s literal elasticity serves as a grotesque exaggeration of this concept, embodying the fragmented self required to navigate a reality defined by contradiction and pressure.

Erving Goffman’s theory of the “presentation of self,” as outlined in The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life, further illuminates how Plastic Man mirrors the postmodern condition. Goffman suggests that individuals are constantly shifting roles to meet social expectations, performing identities in a manner that is more functional than authentic (Goffman, 1956). Plastic Man’s absurd adaptability—a body twisted to fit any circumstance—acts as a caricature of this performative flexibility, where the self becomes as malleable as his form. Just as people today must rebrand themselves to align with shifting cultural and professional expectations, Plastic Man’s transformations expose the absurdity and alienation inherent in these demands.

Historical Context:

Plastic Man’s debut in 1941, amid the rise of consumerism and wartime propaganda, positioned him as a satirical figure in a time when American identity was itself undergoing transformation. His origin as a former criminal turned hero hinted at the era’s struggles with moral ambiguity and the possibility of redemption through adaptive resilience—a precursor to the “plastic” identities of the modern age. As the comic industry matured, Plastic Man’s absurdism became more pronounced, reflecting societal shifts toward individualism, commercialism, and ideological performance. His elastic form becomes a hauntingly accurate reflection of a reality that increasingly values adaptability over authenticity.

Section 2: Absurdity as Satire—Plastic Man and the Theatre of Politics