#but really doesn’t exist not in a reality way but literary way

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

This post may have inspired me to start a blog about answering only the background questions in panels from manga.

Because I love these questions and they’re cool as fuck.

In the tags

God ykno that panel of marcille saying yeah it was highly illegal magic so don't tell anyone about this and chilchuck makes a fucking expression and then is like sure whatever and starts drinking from the bottle. That's how I feel reading some people's posts

#dark elves or dokkalfar taken from Norse mythology are as you can expect#something that doesn’t exist#but really doesn’t exist not in a reality way but literary way#thought to be a mistake in understanding when first Norse myths were translated years ago and now widely accepted to be#the result of treating the elves of Alfheim and opposite their cousins the dwarves of Nidavellir#thus the dwarves would be referred to as dokkalar in contrast with ljosalfar#and the term dark elves to describe dwarves was misunderstood by a generation of fantasy authors#to mean an entirely separate race and indeed an entirely separate made up realm#Svartalfheim#for the dark elves#they’re just dwarves people#they like the dark and also smithing and that’s Nidavellir baby

45K notes

·

View notes

Text

Fundamentally I believe that writing about the rich and varied human existence is so important, and authors who do this end up seeming prescient in ways that naive analysis often rejects.

Two examples. First; a lot of people ship Frodo/Sam or Legolas/Gimli (or more obscure gay ships like Maedhros/Fingon), and some people say stuff like “well, Tolkien was catholic, he clearly didn’t intend for these characters to be gay.” But Tolkien himself says that he doesn’t write Christian allegory, in fact he despises all allegory. What he does is write about the rich and varied human existence, and when he did so he drew on the experiences of the likely closeted gay and bisexual men he had met over his life! And he synthesized this as just a way people behave, not as ‘representation’ but reality. And we can recognize that while in the early twentieth century, the 15% of people that identify as bisexual in the current generation (gen Z) would likely have married people of the opposite gender, that doesn’t mean they didn’t have same-gender relationships that had romantic elements even if they were never consummated.

A second example; in Tamora Pierce’s the Song of the Lioness Quartet, Alanna, the main character, dresses as a boy and trains to be a knight. As she grows up, she has to re-learn to connect with her femininity in secret with the few people who know who she is (thus making her a paradoxically-apt role model for both trans men and trans women, depending on which parts of the narrative one projects oneself onto). But Alanna never feels truly comfortable as a woman, either, and constantly has to assert both her masculinity and femininity to different people once she becomes a knight and reveals the secret. Tamora Pierce has since stated that if Alanna were born in the modern day, she would likely identify as genderfluid. But these books were written in the 1980s, and while there were people in that time period who were exploring the language of nonbinary and genderfluid identities, it wasn’t really a widespread notion, and while I can’t be sure Tamora Pierce didn’t encounter that language I sort of doubt Alanna was intended from the beginning to fit that identity. Instead, Pierce wrote a character based on the people she knew in life, who perhaps uncomfortably chafed at their assigned gender, and wrote a character who really believably would be genderfluid today, despite (plausibly) not knowing what ‘genderfluid’ was!

And I think that’s beautiful. There’s not really a point to this but just to highlight a perspective in literary analysis that you can lose if you focus too much on the biographical details of the author.

425 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fell down a rabbit hole on ancient Israelite child sacrifice and it’s interesting that 1) it’s basically impossible (without jumping through absurd apologetic hoops) to explain important parts of the Hebrew Bible unless they are reacting to, being revised against, or being overlaid on a literary stratum which assumes the existence of Yahwistic child sacrifice; 2) as such it seems there is a very ancient strand of religious law (renegotiated at a very early date!) which specifically commands the sacrifice of all human and animal firstborn males; 3) like all religious law in the Bible, “one group of elites produced religious literature commanding a thing” doesn’t mean that those commandments represent actual universal and uncontested practices—indeed, one of the reasons people produce religious literature is to argue for a set of practices or to shore up their own position by portraying it as normative, and there is very little evidence that the ancient near eastern law codes (religious or secular) produced for propaganda purposes were used like we might use a modern law code; 4) the Canaanite/Phoenecian/Punic/Northwest Semitic religious milieu was certainly one in which infant sqcrifice was at least irregularly practiced, but no such archeological remains have been found in ancient Israel, but by their very nature this kind of infanticide leaves very little remains behind: infant skeletons are small and mostly cartilage, fire seems to have frequently been involved in such sacrifice, and the reason evidence of Carthaginian child sacrifice survived is bc such remains were interred in jars in Carthaginian tophets. 5) While a lot of modern commentators balk at taking the plain meaning of the relevant passages of the Bible seriously, and think that on grounds of basic social and emotional realism they cannot be read as supporting the existence at one time of Yahwistic child sacrifice, we really do not understand the realities of living in an Iron Age society with its attendant phenomenally high infant mortality rates, where many parents seem to have bonded with their children much later, and fertility rates were much higher to compensate for the basic reality of how often babies died. I would add to that my hunch that people in the ancient past were by modern standards just more likely to be traumatized in general, and that probably fucks up how you deal with violence and the value of human life and how you build systems which create social meaning out of death, too. “People in the past were human beings who loved their children” is not incompatible with “people in the past did horrific shit occasionally because they thought it was spiritually, socially, or materially necessary.”

And I am in some ways sympathetic to people who are reluctant to accept evidence of ancient Israelite, or even ancient Carthaginian child sacrifice. It’s so alien to our own moral sensibilities—it is in fact utterly repugnant to them! Ergo the urge to try to read the evidence differently, even if it requires wild contortions. But we know that (for instance) the death penalty and exposure of infants and religious ordeals would have all been common in the region and it seems a small step to me to imagine some ritualization of these practices that at least imbues infanticide with some kind of deeper spiritual significance, if for no other reason than as a kind of cope. In a way it’s encouraging that we have come so far that we refuse to believe any society could have ever endorsed such a thing. Nor is it a recent transition: much of the overt violence and bloodshed of the ancient Israelite law codes was renegotiated away thousands of years ago, and the renegotiation of child sacrifice happened so early that it was a major part of the formation of those codes in the form that we have them now. That too is encouraging—you don’t need modern, historically contingent sensibilities to look at brutal social systems and go “fuck this, let’s replace them with something kinder and more humane.” That tendency is as much a part of the basic forces that drive human history as our violence or our shortsightedness is.

166 notes

·

View notes

Note

obsessed with the idea of jeremy loving hamlet and much ado and i cannot believe i never stopped to think about what his favorite books would be (& specifically which of the classics he most love) before now and i would LOVE to hear any further thoughts you have on this to supplement my own contemplation🫡

HELL YES MY FRIEND

okay fair warning: a good deal of this will be projection, but hey.

a portrait of the artist as a young man by james joyce: guilt!!! so much guilt! and it’s also absolutely delightful to jeremy that such an overtly religion-questioning queercoded book was published in 1916 ireland. and while he doesn’t relate directly to stephen (lack of religious trauma + lack of loving family) he does relate a lot to cranly

ulysses by james joyce (which i haven’t even read yet, so this can’t be projection): he just really likes it okay. english lit majors need to love ulysses

every single thing by ursula le guin: not classics exactly, but he loves the way she challenges normal literary canon expectations, and he just generally really likes unconventional storytelling

okay projection time: the goldfinch by donna tartt. he loves the goldfinch because i love the goldfinch and also because of the culminating realisation of “the space between reality and the point at which the mind hits reality, the rainbow edge where all art exists, and all magic.” also because literature (art) was a very important part of his growth as an individual and he can see that reflected in the goldfinch

he has something against charles dickens. he doesn’t like him

complicated relationship with byron. he can talk for hours about the romantic friend group (byron, the shellys, keats, polidori) and also about the unconventional nature of byron’s poetry, but he will also never miss the opportunity to drag byron through the mud

what about you what do you think??

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

A bunch of people who never read the novels are already crawling out of the woodwork to share their opinions(tm). But “I know the legend of the Witcher and the Witcher girl,” and I got you.

Consider this a highly specific explainer of some of what makes The Witcher novels interesting for those thinking of jumping into W3 or the novels now that 4 is in the works. My interests lie in what stories are doing and how, so this is analytical and not just a summary or reference guide. Wikis exist for that, and if you want to experience the characters you gotta go read the books. No real spoilers because I’m not focusing on plot here.

The Witcher novels are a very cool exercise in dual protagonists driving a convergent narrative operating on two distinct literary frequencies.

Geralt spends most of the books chasing Ciri in some capacity. He’s the man on the ground, getting stuck in personal problems and more ‘realistic’ situations and intrigues (sometimes your friends are also vampires; don’t be weird about it). His world overlaps with the mythic realm, but the sense is that he’s a regular person who keeps ending up in mythic situations. He approaches problems like the professional he is. He’s our guy. But he’s basically just a guy. When he tries to be a hero things tend to go really badly for him.

Ciri is a child of prophecy who befriends unicorns and gets roped into space elf dynastic disasters and visits camelot. She’s also trying desperately to get back to Geralt and Yennefer, her very normal parents. Her world overlaps with the mundane because she’s Geralt’s daughter by choice. She has to study swordplay with her Witcher family and practice magic discipline with Yennefer, but her problems are operating in the realm of myth and folklore. She’s perceived as the holy grail by men who want her power for themselves, a vessel to own and fill with a child. This is a misrecognition, and she remains beyond their grasp because Ciri is really the noble hero Geralt always wished he could be. When people forget that, things go very badly for them.

These two are also a split reference to Elric of Melnibone’s personas. Geralt is the White Wolf and Ciri is the dimension-hopping champion eternal. Their shared role is very consciously designed. Also just about everything is some kind of literary metaphor here.

The Narrative World

Let’s look at what the world-as-narrative is doing and how Witchers function in it.

The Continent exists on a fantasy world where realities have converged, and it greatly resembles Central Europe in its cultures, conflicts, and references. We’re talking Germany/France to the Russian border. This is an area that’s been repeatedly invaded from all sides for millennia. The convergence of spheres operating metaphorically as waves of invasion and overlapping cultures does quite a lot for the story in terms of conflict and setting up an interplanary reality. It also means that everyone is aliens.* Which is objectively the funniest way to do things in addition to providing a pretty fascinating moral bedrock. There’s no 1:1 fantasy race being mapped to real life groups here, though the series is strong in its references to concrete human evils in the real world. Everyone is people. Except monsters. Except when monsters are people too.

Witchers are people who are like monsters. Witcher is also a profession. They’re something that doesn’t fit into any neat category, and that’s the entire point of them. The ones who survive the trials that make them into witchers go on to live brutal lives killing monsters for coin or children to make new Witchers (the trials render them sterile; this is a real thematic beat. I’ll get to it). Witchers are the ‘other’ you’d expect to be scared of in a more conservative fantasy. But in this series, we see this world through the eyes of two Witchers, and we hear the exaggerated stories about their inhumanity, and we know they’re actually people with distinct experiences and perspectives and desires. We know how they feel, and that they’re not doing anything weirder than what everyone else in this world is doing to survive. So we know everyone else is people too. And that lends a very real layer of horror to the fact that by the time we meet our Witchers, most Witchers have already been massacred in a pogrom.

This isn’t as simple as ‘we’re the real monsters’ navel gazing. Over and over we see the different angles of everyone. One moment you’re looking at a strange and alien fae, the next a broken addict. The kindest man you meet is a vampire, and he’s done monstrous things he describes with philosophical eloquence. You’re asked to see the strange and uncanny and ‘other’ in everyone so you can also see the humanity. People are both, always. And the loss of one is the death of both. The novels enforce distinct narrative perspectives to this effect. Everything we know, we know through subjective and limited perspectives. This is a good series for folks fond of Bakhtin.

And if the fact that there are real monsters who aren’t sentient and are absolutely dangerous seems unfair. There’s also mad dogs and people who are beyond all reason and help too (the church is pretty fundamentally evil here and tends to instigate the pogroms. Wonder where a Polish author got that). The text doesn’t shy from the implications.

*except maybe gnomes. That might be a running joke. Nobody knows.

Btw if you’re here from my Dragon Age posts. Yes this is exactly what BioWare tried to immitate but ethically dropped the ball on by doing the exact thing the Witcher resists doing.

Witcher Family Planning

At the heart of this story is a family by choice and maybe destiny.

Geralt is a Witcher who survived an extra round of trials. A mutant among mutants. He’s an extraordinarily competent professional whose sense of justice and soft heart tend to cause him problems. He’s not nice. He’s kind of a boor. He’s very sulky. He loves deeply.

Yennefer is an outrageously overpowered sorceress who really regrets her inability to have children. She’s ambitious even by sorceress standards. Yennefer does things exactly the way she wants to, and that tends to cause her problems. She’s not nice. She’s imperious. She’s very petty. She’s ride or die for anyone she likes even a bit.

These two are the love of each others lives. This is a relationship, and I’m directly paraphrasing here, where two people who don’t know how to be soft try to be soft to each other. They’re bad at it. They keep trying.

Ciri is the lost Scion of every royal line on the continent. She’s also a Witcher. And a child of prophecy. And a dimension-hopping superhero. She’s also about 15 for most of the time we know her in the novels. She’s survived war, led a life of crime, been a gladiator. She’s clever and strong and rebellious and has an innate nobility that shames kings. She has Geralt’s compassionate heart, and she’s honed it to Yennefer’s cutting edge.

Gender & Power

I touched on this up at the top. Over and over again in these books, and in W3, we watch the patriarchal norms of the continent run smack into an interesting reality of the setting. Women tend to be the ones who are ‘first’ in power. There’s a lot of Mists of Avalon happening here. Sorceresses outdo their male peers. All these powerful men think they can have Ciri’s power for themselves by getting a child on her. They ignore that it’s the women in her line who have and wield the gift. They really ignore that her grandmother didn’t even need the gift to bring men like them to their knees. Patriarchy is a kind of willing blindness here. The desire to own and control makes the men of the series into fools who can’t see the obvious. That this isn’t their story.

Amongst Witchers, girl children are usually traded to the dryads for boys. This is left notably vague (another patriarchal blind spot? More likely than you think; there’s hints of female and nonhuman Witchers in the cat school) because by the time we meet our Witchers, the real secrets of their process have been lost. Ciri herself does actually take some of their potions and trials, which seem to potentially interrupt her puberty. Our Witchers are reluctant to subject her to what they went through, so she’s never put through the final trial. But this literally results in the reinforcement of Ciri’s gender by external forces. She is a woman, so that’s actually helpful under the circumstances. But. Fascinating stuff.

Sterility and Reproduction

Briefly. The novels constantly undermine the ‘replacement fear’ of dominant groups set on finding scapegoats for unsolvable problems. Witchers can’t reproduce, so they functionally adopt. Sorceresses may often be sterile too. Elves are particularly slow to reproduce. Women who aren’t mothers and men who live together and adopt and ‘others’ who are probably jealous and stealing our children… And just when you think this is a clumsy metaphor, the text smacks you with the fact that nobody reproduces as fast as regular old humans. This is explicitly about providing zero foundation for any of the bigoted anxieties around ‘nonhumans’, and the presence of sterile humans is here to complicate that very border. The text refuses to cede any quarter to attempts at justifying paranoia-fueled hatred and violence.

The Hero

Ciri is the unique point around which the novels’ tensions cohere. She loses her magical abilities in the books only to awaken to new and greater power. She’s human and nonhuman. A witcher who never completed the trials. Noble and criminal. She’s a woman who literally can’t be physically contained by this patriarchal setting. She’s entirely her own person in a world designed to break her. She’s a hero that eludes a hero’s limits over and over.

Nobody should be surprised that she’s The Witcher.

Novels in order:

Blood of Elves

The Time of Contempt

Baptism of Fire

The Tower of Swallows

The Lady of the Lake

Next Up:

I’ll do a write up with some grittier explanation for what happened between these novels and W3. The games are messy, so we’ll get into it now that you’ve got some themes and angles to roll around.

I may or may not touch on the short stories. Part of the wide misreading of the series is due to folks who’ve read a few of the stories and think that’s what it’s all about. This was also the problem with the show. Well. One of the problems.

#literary analysis#of course I had to start this way have you met me#I promise to be sensible about the game catch-up#that’s a lie#the witcher books#the witcher novels#cirilla fiona elen riannon#is queen of my heart and I’ll never be normal about it#long reads

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

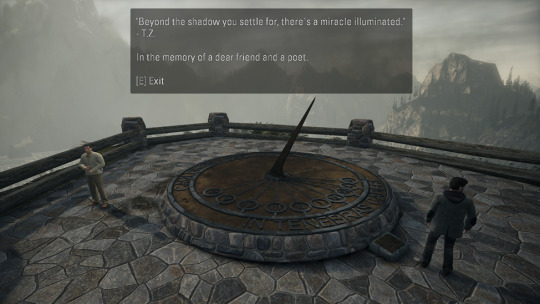

Thomas Zane's writing or the lack thereof

The third and final point I left unanswered in my theory about the 70’s.

the extent of Thomas’ writing powers, since as much as it is stressed a lot that he wrote himself out of reality, Barry, with a little research, is still able to find out about his existence, yet Alan in one of the “Writer in the Cabin” TV’s claims “A story is a beast with a life of its own. You can create it, shape it, but as the story grows, it starts wanting things of its own. Change one thing, and you set off a chain reaction of events that spreads through the whole thing.” The chain reaction here never happens: we have hard evidence that both Thomas and Barbara existed.

I guess, I should start with the rules of writing things into reality, that we learn throughout several games.

In AW1 Alan says about chain reactions: change one thing and others will follow, because the characters and the world in the story must be true to themselves. In AWAN it expanded even further with Alan making his, sometimes quite ridiculous, phantasies come true by starting the chain reaction by nudging the reality to fit his writing. One way or another it’s established well enough: each word causes the butterfly effect. Write something wrong and the whole thing will fall apart or twist; forget to add a little detail and the event you lead to will never happen.

There is a bit more about it in his Hotlines in Control:

Be clever. Make them do the work. Form the image in their minds. They make it. You just imply. Incept. They are drawn to the mystery. Obsessed. You set it up, they put it together. Their interpretation. And there's only one, because you give them no choice. And they believe in it, because it's theirs now.

Again: put a detail in and make people do the work. If you do it clever, you don’t need to expand on every little thing, the story will leave them no choice but to accept, believe and act accordingly.

The story needed many beginnings. Many springs. Streams that turned into a river, a flood, and then, an ocean. This was one. Wake used the materials he had. The connections he had. The people. The places. Wake put them in to make it true. His wife. The psychiatrist. His city. These connections, like magnets, moved things. Alice was a conduit. She'd been in the Dark Place. The Thing-that-Had-Been-Hartman sensed her near. Sensed Wake through her. Went berserk. Broke loose. Wake made sure Alice was already gone by then. Safe. The more springs, the more the story became real. The more people believed. Cause and effect. It was extremely delicate and hard work. It had to go through the path of least resistance. Where success was most likely. Where there was a connection already.

Alan always stresses out how important it is to thread on reality, use all the tools to make the events as plausible as possible for everything to fall into place. Yet, much of his writing, that came true, is pretty unbelievable stuff. Mr. Door in the second game calls Alan out on it: the rules are self-imposed, the loops are a choice. My take on it and all the hoops Alan creates to jump through: it doesn’t really matter what you write, the chain reaction will happen, as longs as you, as a creator, believe that’s possible.

Thomas, as it is presented, certainly, believed that he can erase himself and Barbara from reality; believed that this was the only way to stop the Dark Presence, to undo his mistake. And we see that some of it worked to a certain degree, as Cynthia tells us:

“He tried to undo it, wrote himself, her, everything he’d ever written out of the world. He was so famous. And afterward no one knew. Oh, Tom.”

Alan, who was very involved in the literary world, doesn’t recognise the name when he sees the shoebox in the cabin; Barry claims:

“Yeah, okay... anyway, there was an island there, owned by a guy called Thomas Zane. Now, some of the articles I found about him make him out to be a famous writer. But I ran a bunch of searches, couldn’t find a single thing he wrote.”

Thomas’ works are really hard to come by; the only people who read him, aside from those who knew him closely back in the 70’s, are Alan and Samantha, who found poems in shoeboxes, and Jesse Faden, who might’ve or might’ve not possessed a shoebox of his at some point in time. But the very existence of Thomas Zane and Barbara Jagger is quite known.

Barry with little efforts finds newspaper articles by Cynthia:

“Zane was heavily into diving, so much so that the place came to be called Diver’s Isle. But the volcano under the lake erupted in 1970, and Zane went down with the island.” […] “It gets better: a local girl, Barbara Jagger, drowned in Cauldron Lake just a week earlier. They were lovers.”

Randolph, the trailer park manager, acknowledges that Barbara is quite famous around here:

“Sure, Jagger’s a local spook story: ‘The Scratching Hag!’ Comes for you in the dark. Childish stuff like that.”

(Thomas is a legend around Bright Falls too, by the way, as seen from this bit of Sarah Breaker’s dialog:

Not even mentioning the Diver’s Isle, that still bears the name given to it by Thomas’ hobby.)

Barry continues:

“I’m just getting to the best part: all of the articles about this stuff were written by Cynthia Weaver. I asked around, and she’s that crazy bag lady you met...” […] “Yeah, anyway, she knew both Jagger and Zane before they both died and she had some kind of breakdown.”

And we have two of those articles in the guide:

This one mentions Thomas at the very last paragraph

And here’s the one about Barbara’s death

What we need from them are dates. They both were written before Thomas erased himself and Barbara from existence, so why the chain reaction didn’t delete those evidences together with other magazines and newspapers that mentioned him or printed his works? I mean, the way-to-go for writers at the time was to publish their pieces in the press, even Alan started like this, yet there is nothing of Thomas’. The bits that remained are those written in Bright Falls, where the AWE, caused by the last poem, originated and is strongest. I don’t believe that the journalist being Cynthia matters in this case; she indeed remembers Thomas and Barbara, but her previous work has nothing to do with it and had to be erased.

There is also a problem of fighting the Dark Presence off. I have to admit, the more I dive into this topic, the more I question if Thomas even wrote anything about deleting himself and Barbara from the annals of history or tried to fix him unleashing the Dark Presence onto the world. All we know about this comes from manuscripts written by Alan and the only two other sources of information. One being extremely vague on what happen and what Thomas wanted to achieve:

The Poet and the Muse

In the dead of night she came to him with darkness in her eyes Wearing a mourning gown, sweet words as her disguise He took her in without a word for he saw his grave mistake And vowed them both to silence deep beneath the lake

And another telling a very different story:

This House of Dreams

The diver (or what was left of him, his true self) spoke the words of his secret poem. The poem described a new world, an island in this sea of darkness, a safe haven, a paradise, a “baby” universe. The nature of the dark place was such that anything dreamed up there, any dream or a work of art, would come true, just as true as anything in our world can be. And the poem came true and the essence of the diver and the essence of his girlfriend escaped from the darkness and disappeared into this new world to live there happily ever after; while their shapes, his now taken over by a bright presence, as his girlfriend’s had been taken over by a dark presence, surged up, through the opening in the lake to our world, to continue their battle there.

According to the Bright Presence here, Thomas wrote his masterpiece about the new world, a personal paradise for him and Barbara to be happy there; not about erasing all traces of their existence and trapping the Dark Presence in the depths it came from, since both Presences surged up to the new playground.

So, did Thomas even care about fixing any mistakes, except for not getting the real Barbara back? Or was his writing so sloppy, he failed to erase anyone from reality properly and failed to contain the Dark Presence in the lake? And what happened after he was cosily tucked away in his new private baby-universe in the Dark Place with his love? How exactly did he save Cynthia, as she claims, from the darkness with his light?

What horror was left behind?

In my theory about the cabin, I wrote that we are led to believe that Thomas was caring, considerate and aware enough to leave a loophole for him to help when someone, as he predicted, eventually will awake the Dark Presence. The catch here is: some of this information comes from Alan’s manuscripts; some — from the “characters trapped” in Alan’s story, as Cynthia put it. What if Thomas wasn’t any of those things? What if he only cared about himself and Barbara and wrote them the happy ending, leaving others to deal with the mess that he caused?

IN TENEBRAS CADERE

“To fall into darkness”. Indeed, in the memory of a very questionable poet.

#alan wake#alan wake 2#alan wake game#alan wake ii#alan wake remastered#rcu theory#remedy connected universe#remedy entertainment#remedy games#thomas zane#tom zane

38 notes

·

View notes

Note

Karp, your Saber Alter roleplay is like watching someone put the “try” in try-hard. It’s like you saw the word "dark" in the Fate lore and decided, “Yep, that’s my entire personality now.” We get it, she’s edgy and angsty, but do you really need to make every post sound like she’s one bad day away from releasing her own black metal album? There’s a fine line between staying true to the character and writing dialogue so stiff it feels like it was copy-pasted from a 2005 DeviantArt OC profile.

You lean so hard into the "dark knight" aesthetic that it’s a wonder Saber Alter hasn’t just collapsed under the weight of all that edge. Every interaction reads like she’s contractually obligated to remind everyone how tragic and menacing she is. God forbid anyone tries to have a normal conversation with her—your muse responds with the emotional range of a brick dipped in motor oil. Lighten up! Not every post needs to feel like the literary equivalent of a storm cloud.

Let’s talk about her combat posts for a second. Why does every fight scene feel like it’s trying to win an award for Most Over-the-Top Edgy Description? We get it—she’s powerful and dark, but do her attacks really need to sound like they’re destroying the fabric of reality every single time? Sometimes less is more, but apparently, that concept doesn’t exist in your roleplaying dictionary. Saber Alter could sneeze in your posts, and you’d describe it like it tore open a void in the universe.

Also, can we address the fact that she’s somehow managed to have zero personality outside of being angry or brooding? I’m convinced that if someone handed her a puppy, she’d just glare at it and monologue about the futility of joy. It’s like you’re allergic to giving her any dimension beyond “tragic anti-hero,” and it’s honestly impressive how much you’ve doubled down on keeping her as one-note as possible. At this point, even her sword probably feels emotionally neglected.

In conclusion, your Saber Alter roleplay is the most “edgelord” thing I’ve ever seen, and that’s saying something considering this fandom. You’ve turned her into a caricature of darkness that’s so over-the-top it’s practically comedic. But hey, at least you’re consistent! If nothing else, you’ve mastered the art of making a character with endless potential feel like she’s been written into a corner—and somehow, that’s its own kind of talent.

Alright, homework grading time.

So, first things first. I know you're probably someone i know with some familiarity, so, I get the Anon Mask. Don't want people givin you flak for this, even though frankly, the fact you're on anon to begin with makes me give less than a rats shit about whatever it is you're saying. -10 points, not off to a good start.

Second, I can tell you're familiar with the surface level of what I do here. Congrats, you can skim. Good on ya. You've also shown me that you also don't actually understand Salter like you're claiming I do. The girl is an 'Edge-Lord' on a surface level purely, and I dont blame you for not being able to look past it. For all intents and purposes, as far as FGO is concerned, she's just that: an angry, gluttonous one off joke. Edgy Artoria. Its how she's presented in most media you find her in. And in truth, theres really not all that much to work with her. She's just Artoria whos been corrupted by the Grail. Which means what you can say about Salter you can say about Artoria, because they're still the same person but without the restraint.

Third: you have not actually read the growth of her as a character under my writing. A lot, if not most of it, has been done so with one @miraruinada and my other good pal an writing partner, Vibe. She's grown from the archetype she was into an actual individual with thoughts, wants, hopes and dreams. She's thrown away her crown in both a literal and metaphorical sense and broken away from the chains of obligation and duty that come with it. Salter has learned to open up, in her own way, to others. Is she gonna be personal and friendly to everyone? Of course not. Because she's never been allowed to be an actual person (which is canon motherfucker~) or feel or understand others because she had to be a King before absolutely anything else. Her life was constant war and campaigning, backstabbing from her sister, betrayal, an insurmountable wall of opposition handed to her by her father and his own colossal fuck ups that she still fought tooth an nail against.

Of course she's gonna be emotionally stunted and have to grow. Of course her conversations are going to be fucking weird. Have you even played Artoria's route in FSN? Hell, that whole thing was about humanizing her again. Salt's having to go through that herself, but with the extra weight of her own personal timeline compounding onto the fact.

Fourth: i have not, in fact, wrote a single proper fight scene as Salter in my tenure on this blog. The only time i've even come close to that would probably be her lashing out on my previous blog, which i assume is where you came from to get that kind of idea. Besides, have you even seen Heaven's Feel movies or her animations? Every swing she does to begin with is maximum effort with full intent to kill behind every blow. She's a powerhouse in a five foot nothing body that no diffed Heracles in Heaven's Feel and obliterated a meteor in Shinjuku.

Fifth: You really dont read my posts, at all dood. One look, again, at her interactions with @miraruinada would prove that. Her interactions with @avaloniamagus's Merlin, whom she regards as her proper father figure. @rake-rake's Oberon, with whom she's form a bond with, learning from his dramatics and finding comfort in family that she never knew. I could go on, and on, and on, but, that'd be givin you more time an attention than i've already given, or that you deserved my guy.

in review:

Suck my fat girl nuts an go touch some grass my guy.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Alethic Value

I am so sick of the only stuff I enjoy being slice of life bullshit! These past few seasons of anime have not had anything I found even slightly enjoyable that isn’t, somehow, at its base level, a grounded story about a real space told with animation! Why aren’t I watching things where people use laser swords or have shapeshifting raven powers or creep around in dungeons?

Oh, because I tried all those things that include those ideas and I think they’re bad? All of them? That’s rough. Shame. Maybe the people who make anime should get around to making anime I like again.

This isn’t about the anime that are bad and yes, I did try Dungeon Meishi and no, I don’t like it, but this is rather about the realisation that I have a feeling and a preference about the anime that I like to watch and in this moment I am frustrated by the play space of these stories in terms of their unvaried alethic value.

But hey, you may ask, what’s alethic value? What a weird turn of phrase. Does it come from somewhere? Well, yeah, it comes from Greek, which is one of the uniform languages of smartypants and academic terminology. In philosophy, Alethia is used to refer to the idea of truth or disclosure — and here’s our first pause because the person who popularised that term is Martin Heidegger. Heidegger is a dude with a lot of complicated ideas but also any time he comes up I feel the need to share that that guy was a Nazi. This can be upgraded depending on the scenarion into ‘Nazi, well,’ or ‘Nazi, but’ but I feel like if I don’t mention that Marty Heidy’s A Naughty Nazi I’m leaving something important unsaid in the conversation.

Anyway, Alethia isn’t just ‘true’ness, in the philosophical discussion, it’s something else, a secret third thing, but I’m not going to get bogged down in that even though we’re talking about ontology which is a discipline that owes a lot to Martin Heidegger who got promotions at university by reporting on the Jewishness of various people who were directly above him in the organisational structure. Ontology is the philosophical consideration (because it feels weird to call it ‘study’) of being. Like, anything being. The fundamental concept of things existing.

Ontology’s heavy, but don’t worry, we’re not using it, not properly. We’re driving by ontology’s house and throwing a brick, it’s fine.

Anyway, there’s this literary scholar, Marie-Laure Ryan. In her writing about fiction and literature, she has this text called Ontological Rules, in which she describes categorical approaches — a playful approach really — to the consideration of types of stories. It’s a lengthy list and it’s super interesting, including a consideration of the individuals involved — are you literally only using real verifiable people who existed in your story? What kind of natural species exist? Are the natural laws available but subjugated periodically?

But the thing is, the top layer of all of this is a consideration of the alethic values of the world. Alethic values in this context, discusses the idea of the modalities of truth. That is to say, how does the world of the fiction engage with the reality of the primary world. This conversation gets really interesting and weird because of course, reality is as we understand it not subjective, but functionally it is subjective. If I put aliens in a story, that doesn’t necessarily mean the story isn’t historic fiction if I believe that aliens are real and the reader believes aliens are real. But if aliens aren’t real (at least not the way the story is representing them) then suddenly we’re left with a story where the modality of truth has to kind of dial into a mean from a communal whole that nobody can necessarily connect.

If you believe in magic, stories about wizards might well be historical fiction, to you.

Heck, Star Wars represents itself as historic fiction and modern day Jedi believers may well consider it to be the same.

What makes this extra complicated is that there are a lot of normal unrealities that everyone believes in. Hey, what’s Australia like? Wrong! Unless you’re Fox, hearing me say this, or one of the small number of Australian readers I have. But you have a way of seeing Australia represented in your mind and that representation is based on an assumption about what is real that may be just factually wrong.

But here’s the big thing about alethic values as boundaries on what ‘reality’ can include in the context of the storytelling of a universe: We don’t like when alethic values sequence to one another.

If you’re playing Skyrim and someone has a book in that world about hey, these are the stories of the seven starskalds in their space horses that cruise through the skies and travel from world to world and encounter all sorts of monsters of the week and that, people go ‘hey, that’s bullshit.’ Right? Because somehow, the idea that there is fiction in the universe of the fiction of the game, that fiction itself has to be bound within the parameters of that universe. Because the idea that characters who see unicorns have a vision of what normalcy means creates an entirely different relationship of those fantastic characters to the fantastic. To you, unicorns are bullshit, but in their universe, unicorns are real, and how much can you imagine those people having the ability to dream up the Starship Enterprise?

And there’s also just this idea of nonsense gaps; they don’t need to dream up spaceships right, because they have magic and dragons and just go to other worlds. Even worlds that are meant to have a vibrant fictional world, like again, Star Trek, it doesn’t largely represent theatre and the arts except as emulations of our now. There’s a deep indulgence in (human) history, and like, I get the problems of representing the vastness of that alethic gap, where you have to dream up a guy and then dream up that guy’s dreams?

I want deeper alethic value. I want more variety. I want some cool shows about fuckin dragons god damnit.

Check it out on PRESS.exe to see it with images and links!

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

A bit more on Heavenly misunderstanding

I’ve already posted about this, but felt like I needed to come back and restate this, hopefully, a bit better.

Aziraphale and Crowley have a fundamental misunderstanding because they do not view Heaven in the same way. Obviously for Crowley, the Fall was transformational. Crowley sees Heaven and God as two separate entities; one unreachable and mysterious, the other drunk on power and lost in petty squabbles and corporate greed. Without that loss, Aziraphale has internalized the concept that God and Heaven are one and therefore the goals of one must be that of the other, theoretically “good”.

If I were doing a literary analysis, I would say that Crowley is representative of our personal relationship with God and spirituality. I’ve heard Hell described as an “absence from God” and for Crowley I believe that is true. Crowley’s trauma from the Fall is more about being rejected by God than being removed from Heaven and doing “good”. He has carved out a reasonably comfortable existence, but he is unable to create, satisfy his curiosity and help those in need. We see that when in crisis he still talks directly to God. In the Job minisode, we see him wistful for the opportunity to ask God a question, to talk to her.

Crowley sees Heaven for what it is, an artificial construct that separates God from the execution of the Plan, ineffable or not. Because of that distinction, Crowley views Heaven as toxic, uncaring and separate from God and “goodness.” He acknowledges the reality that in it’s pursuit of the Plan, Heaven is willing to perform any deed necessary to win. Crowley rejects being reinstated because he doesn’t need a corporate mistake to be fixed or even to be protected from Hell for doing good. He needs to be restored to communication with God and that’s beyond the power of Heaven and is beyond Aziraphale’s fundamental understanding until the end of Season 2.

I have a fundamental belief that Aziraphale is not the angel we believe him to be. I will write more about that later, but suffice it to say he experienced a heavenly trauma that has yet to be revealed, but has left him in the state that we see until the end of Season 2. He has been kept within the confines of the corporate-like structure of Heaven encouraged to bring about the Plan and believe in the ineffable power of “good”. From a literary standpoint, I'd say that Aziraphale represents our relationship with organized religion and society as a whole.

He is encouraged to follow his duties of doing good and thwarting evil, even when they bring him into direct conflict with the Plan and are doomed to failure. He has had the structure, policies and procedures reinforced to him. He struggles with the need for affirmation and approval and turns to the rules and authority for comfort and guidance when it is lacking from his superiors. He has been repeatedly told he is not enough.

He functions on faith. It’s mainly faith in the system. Aziraphale has faith in God and the ineffable Plan, whatever that may be, but he relies on the system. And for him, the system is Heaven and God working as one. "The Almighty" isn't as personal a concept for him. His first response to crisis or a lack of guidance isn’t to directly address God, even if he knows that she's ultimately running the show. He appeals to a higher authority within the Heaven’s structure.

In Season 1 he does try to reach God, but settles for the Metatron, an intercessor.

In every case, Aziraphale allows himself to believe that he is the one at fault, surely the system, Heaven, couldn’t be wrong. Sadly, I don't think that Aziraphale ever experiences a personal relationship, ever. I think that lack makes the ineffable plan an esoteric concept that he feels he should aspire to, even if he doesn't really get it, much like a corporate mission statement. He has been gas-lit and bullied, degraded and demeaned until his innate response is to believe that it’s him.

Aziraphale will never be able to understand how Crowley views God and heaven until he goes to heaven and sees the disconnect for himself. Not just see the disconnect, but see that he is powerless to make a change. He’s the little engine that could. Aziraphale needs to see that far greater than him cannot stop the power of Heaven. He has to see that Heaven is a machine that has corrupted goodness and possibly the will of God. Then he has the foundation to understand why.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

I love your post about backend motivation vs frontend motivation in the HTTYD series!!! I’ve always had a bit of a problem with the sequels (especially the third movie) that I could never put into words, but the difference in motivation is EXACTLY it. The Hidden World in particular had a specific ending in mind, wich isn’t necessarily a bad thing, but their solution was to force the ending into existence instead of letting the story naturally build up to the ending. And you can feel the story straining soooooo much when Toothless acts like a dog for twenty minutes or Grimmel does something simple/obvious that the narrative treats as an ingenious act of strategy. It’s just not genuine! The characters simply wouldn’t act like that, but the writers let plot dictate characters instead of the other way around, and it’s just. so disappointing. There has to have been a way to keep the natural tensions and eventual triumphs of dragon/human bonds without resorting to flattening everyone’s character and taking the story in a weird, half-baked direction.

————————————————————————————-

Oh my gosh B. You’re still there??????? THANK YOU for being faithful to my blog even tho I’ve not really posted anything proper in ages!!! I’m so happy to hear from you!!!

I’m glad you liked my post XD Ok so. I remembered that what I tried to express is called “Watsonian vs. Doylish” interpretation in fandom (based on this post), or easier, it’s about giving in-universe explanations vs. ex-universe explanations for something that happens in the plot. The actual literary terms according to Gérard Genette for that would be “intra-diegetic” vs. “extra-diegetic”.

The specific difference the terms “back-end vs. front-end motivation” makes, seems to be the phenomenon that building a story from the start allows it to better make sense inside the universe, whereas building a story from its ending reveals the circumstances that the author found themselves in when creating it.

Anyway so what I always found strange is that Httyd2 had all those same problems you named, yet no one talks about that and only bashes on the third movie! Wanna enlighten me on why the second movie worked for you???

Ok so this is spontaneously going to turn into the “Ooc Hiccup post” that I promised at the beginning of the year. I hope you’re ok with that.

WHY IS HICCUP OOC IN HTTYD2?

because his new conflict (”becoming Chief”) was pulled out of thin air and wasn’t already an established extension of Berk’s situation. (a part I always loved about Httyd1 was that Hiccup wasn’t made out to be a Disney Princess who would have to face the duty of leading eventually. I expected the question of succession to be handled far more casually - that someone who wanted to be worthy could be Chief on Berk, not because Hiccup was expected to continue Stoick’s legacy. In fact I wish Stoick would have let him go rampant with the smithy and all his crazy inventions, making him Gobber’s successor first - since Gobber is also canonically older than Stoick - and lining Astrid up to be the next actual Chief. There could have been a sudden plot twist where Astrid realizes she doesn’t want to do it alone and that she needs Hiccup in this with her. It would have made them the ruling couple in a different way.)

because the movie made him immature on purpose so it could justify slapping the “necessary” growth arc on him. (Look, Hiccup has always been reckless and a little bit too trusting when presented with danger, but he was never ignorant of a certain reality or too stupid to see error in his ways. Httyd2 depicts him as a naive dragon geek who can’t see past the destructive potential this has on the humans around him. Eret has had a shit life and a dark past. Drago has his reasons for what he does. Yet Hiccup is far too quick to ignore the trauma that the tribes of the Archipelago suffered because of the dragon plague, and simply forgives his mother despite the fact that she chose to save dragons over raising her own son. It’s all in the name of dragon welfare now and that is just not Hiccup. Og Hiccup took time to engage with Astrid’s valid scepticism. Og Hiccup killed the Red Death to save his tribe. He did not attempt to train that one, if you get what I’m saying. The dragons were never pets.)

because Stoick died only so he wouldn’t get in the way of Hiccup’s leadership. (After all that happens, Hiccup - to me - hasn’t suddenly evolved into a wiser or more experienced person. He just righteously got his ass kicked for the stupidity that was forced onto his character. He then becomes Chief not because he has learned much from the situation, but because Stoick is now dead. It’s true that Hiccup says “Sorry, Dad” to the funeral pyre, but it is never specified what he’s sorry for. To me, he does understand that he got his father killed, but he doesn’t get a grasp on why. He hasn’t the faintest notion of what Stoick did for him, to what extent his father came after him. There was desperation in Stoick to save his son. And Hiccup never feels this guilt much. It is then very convenient that he can freely lead the people of Berk and appear as a competent Chief simply because there is no more Stoick to disagree with him. I loved the version in the books where Hiccup becomes king and Stoick as well as Valhallarama are both alive and well to see it!!!! And Stoick, Chief of the Hairy Hooligans, has to take a step back and let his son shine.)

Right. So that’s that. The second point is by far my greatest criticism regarding Httyd2. Hiccup, in my opinion, was always balanced between the needs of dragons and humans. He is not a “dragon geek”. It simply so happened that a dragon became his best friend because no one else wanted to be his friend at first. Movie!Hiccup is an “invention geek”!!! The time he spends building stuff in the smithy is so important to his character! He doesn’t fix stuff by talking. He fixes stuff by building tools first and explaining them to everyone else second. That’s how I’ve always understood him. Httyd3 Hiccup partly returned to that focus with his fireproof armor, the fully developed flightsuits and the docking contraption for ships that he made on New Berk. The Hiccup I know acts more, gains emotional insight by observation, and talks less.

Of course I agree with all of your criticism of Httyd3. Yes the movie felt strained. But I admit that because I enjoyed Hiccup’s hesitant yet determined character again, I can overlook its flaws much easier than the flaws of Httyd2.

Let me know what you think!

#httyd#httyd2#httyd3#httyd franchise#analysis#httyd analysis#httyd2 analysis#httyd3 analysis#wherethekiteflies#wherethekitethought#b#ask#asks#anon#anonymous

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Generative AI: An Argument for the Soul

This is gonna be a long one, so lemme start out by stating a few things that I am and am not saying.

What I am not saying:

Generative AI is inherently good.

Generative AI is inherently bad.

A machine or other computer-based system with a soul or fully self-conscious sapience is impossible.

Generative AI is incontrovertible proof that there is a soul.

The spirit is good and material is bad (that would be gnosticism, after all).

What I am saying:

The advances in generative AI and the remaining shortcomings thereof are, I think, further evidence for the existence of a soul, a spirit, what-have-you—some spiritual element within our human intelligence that transcends the simply physical/material.

And I’m not going to pretend that I’m the first to make the argument that reason cannot fully explain the phenomenon of reason: literary and theological greats such as G. K. Chesterton, C. S. Lewis, and Alvin Plantinga have all made the same point.

So, now that the preamble is out of the way: in AI art, while there’s a lot of fascinating stuff you can generate with it, it’s still very obvious that the AI doesn’t actually understand the prompt—it’s using a probability algorithm, but it doesn’t have any sort of inherent knowledge to cross-reference or anything. For example, these few prompts I made when goofing around with Midjourney:

Prompt: The Call of Cthulhu in the style of a UPA cartoon

Prompt: An eldritch space creature that’s a fusion of a crocodile and a spider, with a chitinous carapace, on the surface of a moon.

It’s creative, but it has an... emptiness to it. There’s no idea that the AI could really understand why these things are good matches for the prompts. And I think AI writing has the same sort of issue (I don’t know of any examples off the top of my head, sadly).

So how does this tie into the idea that there must be a soul? Well, as trite as it is, in many ways, these LLMs are very similar to the human brain. They’re networks of software neurons that communicate in a way that’s modeled off of how the neurons interact in humans and other animals. That’s not to say that LLMs are based on detailed models of human brains, but as far as I understand, there are some broad, basic similarities. And, for all the worries about an AI rebellion or AI overlords overthrowing civilization, we’re seeing that LLMs, while novel and more powerful than previous chatbots/etc., still have their own limitations, and they’re pretty stark when compared to what a human can do.

This on its own, of course, doesn’t prove that AIs couldn’t have the same sort of capability as a human, or possess that level of consciousness/sapience. But it’s another drop in the (to me) ocean of evidence that there is more to our experience than just the physical. The primary point of evidence, however, isn’t exactly new: all three of those authors I mentioned above have pointed it out, and G. K. Chesterton lived from 1874–1936. And as he wrote in 1906:

That peril is that the human intellect is free to destroy itself. Just as one generation could prevent the very existence of the next generation, by all entering a monastery or jumping into the sea, so one set of thinkers can in some degree prevent further thinking by teaching the next generation that there is no validity in any human thought. It is idle to talk always of the alternative of reason and faith. Reason is itself a matter of faith. It is an act of faith to assert that our thoughts have any relation to reality at all. If you are merely a sceptic, you must sooner or later ask yourself the question, "Why should anything go right; even observation and deduction? Why should not good logic be as misleading as bad logic? They are both movements in the brain of a bewildered ape?" The young sceptic says, "I have a right to think for myself." But the old sceptic, the complete sceptic, says, "I have no right to think for myself. I have no right to think at all." ~ G. K. Chesterton, Orthodoxy, Chapter III

If all of our thoughts are just molecular happenstance, why should we have any faith that our ability to reason has any reflection of reality?

C. S. Lewis also puts forth much the same argument, in a more detailed way.

All possible knowledge, then, depends on the validity of reasoning. If the feeling of certainty which we express by words like must be and therefore and since is a real perception of how things outside our own minds really ‘must’ be, well and good. But if this certainty is merely a feeling in our own minds and not a genuine insight into realities beyond them—if it merely represents the way our minds happen to work—then we can have no knowledge. Unless human reasoning is valid no science can be true. It follows that no account of the universe can be true unless that account leaves it possible for our thinking to be a real insight. A theory which explained everything else in the whole universe but which made it impossible to believe that our thinking was valid, would be utterly out of court. For that theory would itself have been reached by thinking, and if thinking is not valid that theory would, of course, be itself demolished. It would have destroyed its own credentials. It would be an argument which proved that no argument was sound—a proof that there are no such things as proofs—which is nonsense. Thus a strict materialism refutes itself for the reason given long ago by Professor Haldane: ‘If my mental processes are determined wholly by the motions of atoms in my brain, I have no reason to suppose that my beliefs are true…and hence I have no reason for supposing my brain to be composed of atoms.’ (Possible Worlds, p. 209) … Any thing which professes to explain our reasoning fully without introducing an act of knowing thus solely determined by what is known, is really a theory that there is no reasoning. But this, as it seems to me, is what Naturalism is bound to do. It offers what professes to be a full account of our mental behaviour; but this account, on inspection, leaves no room for the acts of knowing or insight on which the whole value of our thinking, as a means to truth, depends. ~ C. S. Lewis, Miracles (Collected Letters of C. S. Lewis), Ch. 3

Somewhat paradoxically, this is also something that we cannot ourselves reason into reasoning—that is, we cannot use Reason to prove that Reason exists, because then we are using circular logic, and furthermore, we are basing our proof on the thing on trial. To quote Lewis again:

But the very attempt [to prove the naturalistic rising of Reason within the human mind] is absurd. This is best seen if we consider the humblest and almost the most despairing form in which it could be made. The Naturalist might say, ‘Well, perhaps we cannot exactly see—not yet—how natural selection would turn sub-rational mental behaviour into inferences that reach truth. But we are certain that this in fact has happened. For natural selection is bound to preserve and increase useful behaviour. And we also find that our habits of inference are in fact useful. And if they are useful they must reach truth’. But notice what we are doing. Inference itself is on trial: that is, the Naturalist has given an account of what we thought to be our inferences which suggests that they are not real insights at all. We, and he, want to be reassured. And the reassurance turns out to be one more inference (if useful, then true)—as if this inference were not, once we accept his evolutionary picture, under the same suspicion as all the rest. If the value of our reasoning is in doubt, you cannot try to establish it by reasoning. If, as I said above, a proof that there are no proofs is nonsensical, so is a proof that there are proofs. Reason is our starting point. There can be no question either of attacking or defending it. If by treating it as a mere phenomenon you put yourself outside it, there is then no way, except by begging the question, of getting inside again. ~ C. S. Lewis, Miracles (Collected Letters of C. S. Lewis), Ch. 3 [emphasis mine]

(I will make a side note here: the issue that I—and I suspect Lewis himself—have with the proposal of reason evolving in humans is the idea that it evolved naturally; that is, without any external force or actor causing it to evolve, but evolving in the sense of it being a purely material element. Evolution itself, as I see it, is very well established, and does not contradict Christian theology at all—I recommend Adam and the Genome by Dennis Venema and Scott McKnight for further reading if anyone is curious)

As I see it, if we believe that our ability to reason has any bearing whatsoever on the real world, beyond the purely coincidental, then we must accept that there is a supernatural element to it—a soul, a spirit, an animus, call it what you will. That is not to say that the brain cannot affect our thought processes—I have a few different mental disorders/neurodivergencies/what-have-you, and am very much on the side of science in that regard. But the brain is not the be-all-end-all when it comes to reason, either. And I think C. S. Lewis put it best when he described the brain as a lens through which our souls/minds view the world (couldn't find the exact quote, so I don't know which book it’s from). We do not live in our brains, nor are we just our brains, any more than the human body is just the heart or just the head.

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Green Knight and Medieval Metatextuality: An Essay

Right, so. Finally watched it last night, and I’ve been thinking about it literally ever since, except for the part where I was asleep. As I said to fellow medievalist and admirer of Dev Patel @oldshrewsburyian, it’s possibly the most fascinating piece of medieval-inspired media that I’ve seen in ages, and how refreshing to have something in this genre that actually rewards critical thought and deep analysis, rather than me just fulminating fruitlessly about how popular media thinks that slapping blood, filth, and misogyny onto some swords and castles is “historically accurate.” I read a review of TGK somewhere that described it as the anti-Game of Thrones, and I’m inclined to think that’s accurate. I didn’t agree with all of the film’s tonal, thematic, or interpretative choices, but I found them consistently stylish, compelling, and subversive in ways both small and large, and I’m gonna have to write about it or I’ll go crazy. So. Brace yourselves.

(Note: My PhD is in medieval history, not medieval literature, and I haven’t worked on SGGK specifically, but I am familiar with it, its general cultural context, and the historical influences, images, and debates that both the poem and the film referenced and drew upon, so that’s where this meta is coming from.)

First, obviously, while the film is not a straight-up text-to-screen version of the poem (though it is by and large relatively faithful), it is a multi-layered meta-text that comments on the original Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, the archetypes of chivalric literature as a whole, modern expectations for medieval films, the hero’s journey, the requirements of being an “honorable knight,” and the nature of death, fate, magic, and religion, just to name a few. Given that the Arthurian legendarium, otherwise known as the Matter of Britain, was written and rewritten over several centuries by countless authors, drawing on and changing and hybridizing interpretations that sometimes challenged or outright contradicted earlier versions, it makes sense for the film to chart its own path and make its own adaptational decisions as part of this multivalent, multivocal literary canon. Sir Gawain himself is a canonically and textually inconsistent figure; in the movie, the characters merrily pronounce his name in several different ways, most notably as Sean Harris/King Arthur’s somewhat inexplicable “Garr-win.” He might be a man without a consistent identity, but that’s pointed out within the film itself. What has he done to define himself, aside from being the king’s nephew? Is his quixotic quest for the Green Knight actually going to resolve the question of his identity and his honor – and if so, is it even going to matter, given that successful completion of the “game” seemingly equates with death?

Likewise, as the anti-Game of Thrones, the film is deliberately and sometimes maddeningly non-commercial. For an adaptation coming from a studio known primarily for horror, it almost completely eschews the cliché that gory bloodshed equals authentic medievalism; the only graphic scene is the Green Knight’s original beheading. The violence is only hinted at, subtextual, suspenseful; it is kept out of sight, around the corner, never entirely played out or resolved. In other words, if anyone came in thinking that they were going to watch Dev Patel luridly swashbuckle his way through some CGI monsters like bad Beowulf adaptations of yore, they were swiftly disappointed. In fact, he seems to spend most of his time being wet, sad, and failing to meet the moment at hand (with a few important exceptions).

The film unhurriedly evokes a medieval setting that is both surreal and defiantly non-historical. We travel (in roughly chronological order) from Anglo-Saxon huts to Romanesque halls to high-Gothic cathedrals to Tudor villages and half-timbered houses, culminating in the eerie neo-Renaissance splendor of the Lord and Lady’s hall, before returning to the ancient trees of the Green Chapel and its immortal occupant: everything that has come before has now returned to dust. We have been removed even from imagined time and place and into a moment where it ceases to function altogether. We move forward, backward, and sideways, as Gawain experiences past, present, and future in unison. He is dislocated from his own sense of himself, just as we, the viewers, are dislocated from our sense of what is the “true” reality or filmic narrative; what we think is real turns out not to be the case at all. If, of course, such a thing even exists at all.

This visual evocation of the entire medieval era also creates a setting that, unlike GOT, takes pride in rejecting absolutely all political context or Machiavellian maneuvering. The film acknowledges its own cultural ubiquity and the question of whether we really need yet another King Arthur adaptation: none of the characters aside from Gawain himself are credited by name. We all know it’s Arthur, but he’s listed only as “king.” We know the spooky druid-like old man with the white beard is Merlin, but it’s never required to spell it out. The film gestures at our pre-existing understanding; it relies on us to fill in the gaps, cuing us to collaboratively produce the story with it, positioning us as listeners as if we were gathered to hear the original poem. Just like fanfiction, it knows that it doesn’t need to waste time introducing every single character or filling in ultimately unnecessary background knowledge, when the audience can be relied upon to bring their own.

As for that, the film explicitly frames itself as a “filmed adaptation of the chivalric romance” in its opening credits, and continues to play with textual referents and cues throughout: telling us where we are, what’s happening, or what’s coming next, rather like the rubrics or headings within a medieval manuscript. As noted, its historical/architectural references span the entire medieval European world, as does its costume design. I was particularly struck by the fact that Arthur and Guinevere’s crowns resemble those from illuminated monastic manuscripts or Eastern Orthodox iconography: they are both crown and halo, they confer an air of both secular kingship and religious sanctity. The question in the film’s imagined epilogue thus becomes one familiar to Shakespeare’s Henry V: heavy is the head that wears the crown. Does Gawain want to earn his uncle’s crown, take over his place as king, bear the fate of Camelot, become a great ruler, a husband and father in ways that even Arthur never did, only to see it all brought to dust by his cowardice, his reliance on unscrupulous sorcery, and his unfulfilled promise to the Green Knight? Is it better to have that entire life and then lose it, or to make the right choice now, even if it means death?

Likewise, Arthur’s kingly mantle is Byzantine in inspiration, as is the icon of the Virgin Mary-as-Theotokos painted on Gawain’s shield (which we see broken apart during the attack by the scavengers). The film only glances at its religious themes rather than harping on them explicitly; we do have the cliché scene of the male churchmen praying for Gawain’s safety, opposite Gawain’s mother and her female attendants working witchcraft to protect him. (When oh when will I get my film that treats medieval magic and medieval religion as the complementary and co-existing epistemological systems that they were, rather than portraying them as diametrically binary and disparagingly gendered opposites?) But despite the interim setbacks borne from the failure of Christian icons, the overall resolution of the film could serve as the culmination of a medieval Christian morality tale: Gawain can buy himself a great future in the short term if he relies on the protection of the enchanted green belt to avoid the Green Knight’s killing stroke, but then he will have to watch it all crumble until he is sitting alone in his own hall, his children dead and his kingdom destroyed, as a headless corpse who only now has been brave enough to accept his proper fate. By removing the belt from his person in the film’s Inception-like final scene, he relinquishes the taint of black magic and regains his religious honor, even at the likely cost of death. That, the medieval Christian morality tale would agree, is the correct course of action.

Gawain’s encounter with St. Winifred likewise presents a more subtle vision of medieval Christianity. Winifred was an eighth-century Welsh saint known for being beheaded, after which (by the power of another saint) her head was miraculously restored to her body and she went on to live a long and holy life. It doesn’t quite work that way in TGK. (St Winifred’s Well is mentioned in the original SGGK, but as far as I recall, Gawain doesn’t meet the saint in person.) In the film, Gawain encounters Winifred’s lifelike apparition, who begs him to dive into the mere and retrieve her head (despite appearances, she warns him, it is not attached to her body). This fits into the pattern of medieval ghost stories, where the dead often return to entreat the living to help them finish their business; they must be heeded, but when they are encountered in places they shouldn’t be, they must be put back into their proper physical space and reminded of their real fate. Gawain doesn’t follow William of Newburgh’s practical recommendation to just fetch some brawny young men with shovels to beat the wandering corpse back into its grave. Instead, in one of his few moments of unqualified heroism, he dives into the dark water and retrieves Winifred’s skull from the bottom of the lake. Then when he returns to the house, he finds the rest of her skeleton lying in the bed where he was earlier sleeping, and carefully reunites the skull with its body, finally allowing it to rest in peace.

However, Gawain’s involvement with Winifred doesn’t end there. The fox that he sees on the bank after emerging with her skull, who then accompanies him for the rest of the film, is strongly implied to be her spirit, or at least a companion that she has sent for him. Gawain has handled a saint’s holy bones; her relics, which were well known to grant protection in the medieval world. He has done the saint a service, and in return, she extends her favor to him. At the end of the film, the fox finally speaks in a human voice, warning him not to proceed to the fateful final encounter with the Green Knight; it will mean his death. The symbolism of having a beheaded saint serve as Gawain’s guide and protector is obvious, since it is the fate that may or may not lie in store for him. As I said, the ending is Inception-like in that it steadfastly refuses to tell you if the hero is alive (or will live) or dead (or will die). In the original SGGK, of course, the Green Knight and the Lord turn out to be the same person, Gawain survives, it was all just a test of chivalric will and honor, and a trap put together by Morgan Le Fay in an attempt to frighten Guinevere. It’s essentially able to be laughed off: a game, an adventure, not real. TGK takes this paradigm and flips it (to speak…) on its head.

Gawain’s rescue of Winifred’s head also rewards him in more immediate terms: his/the Green Knight’s axe, stolen by the scavengers, is miraculously restored to him in her cottage, immediately and concretely demonstrating the virtue of his actions. This is one of the points where the film most stubbornly resists modern storytelling conventions: it simply refuses to add in any kind of “rational” or “empirical” explanation of how else it got there, aside from the grace and intercession of the saint. This is indeed how it works in medieval hagiography: things simply reappear, are returned, reattached, repaired, made whole again, and Gawain’s lost weapon is thus restored, symbolizing that he has passed the test and is worthy to continue with the quest. The film’s narrative is not modernizing its underlying medieval logic here, and it doesn’t particularly care if a modern audience finds it “convincing” or not. As noted, the film never makes any attempt to temporalize or localize itself; it exists in a determinedly surrealist and ahistorical landscape, where naked female giants who look suspiciously like Tilda Swinton roam across the wild with no necessary explanation. While this might be frustrating for some people, I actually found it a huge relief that a clearly fantastic and fictional literary adaptation was not acting like it was qualified to teach “real history” to its audience. Nobody would come out of TGK thinking that they had seen the “actual” medieval world, and since we have enough of a problem with that sort of thing thanks to GOT, I for one welcome the creation of a medieval imaginative space that embraces its eccentric and unrealistic elements, rather than trying to fit them into the Real Life box.

This plays into the fact that the film, like a reused medieval manuscript containing more than one text, is a palimpsest: for one, it audaciously rewrites the entire Arthurian canon in the wordless vision of Gawain’s life after escaping the Green Knight (I could write another meta on that dream-epilogue alone). It moves fluidly through time and creates alternate universes in at least two major points: one, the scene where Gawain is tied up and abandoned by the scavengers and that long circling shot reveals his skeletal corpse rotting on the sward, only to return to our original universe as Gawain decides that he doesn’t want that fate, and two, Gawain as King. In this alternate ending, Arthur doesn’t die in battle with Mordred, but peaceably in bed, having anointed his worthy nephew as his heir. Gawain becomes king, has children, gets married, governs Camelot, becomes a ruler surpassing even Arthur, but then watches his son get killed in battle, his subjects turn on him, and his family vanish into the dust of his broken hall before he himself, in despair, pulls the enchanted scarf out of his clothing and succumbs to his fate.

In this version, Gawain takes on the responsibility for the fall of Camelot, not Arthur. This is the hero’s burden, but he’s obtained it dishonorably, by cheating. It is a vivid but mimetic future which Gawain (to all appearances) ultimately rejects, returning the film to the realm of traditional Arthurian canon – but not quite. After all, if Gawain does get beheaded after that final fade to black, it would represent a significant alteration from the poem and the character’s usual arc. Are we back in traditional canon or aren’t we? Did Gawain reject that future or didn’t he? Do all these alterities still exist within the visual medium of the meta-text, and have any of them been definitely foreclosed?