#but part of the beauty of transformers is that their stories? their mythology and religious stuff? can be proven

Text

So, Rodimus, you're making sense here and it seems like you guys might've found what you were questing for. But dear Primus does that take so much of the whimsy and symbolism and raw meaning out of it.

#now i like logical explanations#i really do#but part of the beauty of transformers is that their stories? their mythology and religious stuff? can be proven#they've got evidence— true honest evidence. they can explain it and how it works#because it's not just ''uwu magic''#there do seem to be rules#pluuuuus there's the fact i know this adventure doesn't end here#there's more to this than meets the eye#comic reading#riot rambles

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

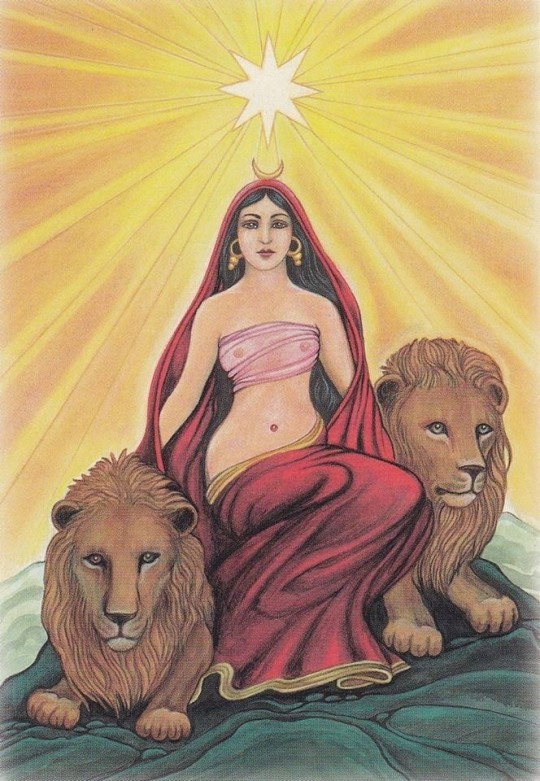

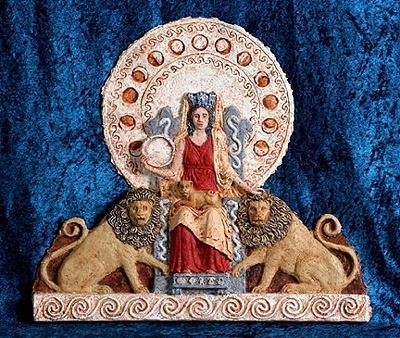

Bharani : the birth of Venus.

Part 1

Let's talk about ancient godesses of love and Bharani nakshatra.

I will base my research on the legend of the dead and resurrected god present in many religious myths coming from the middle east (ps : i'm sorry in advance for the grammar, syntax or spelling mistakes that you may find in this post, english is not my first language)

Bharani, situated in the heart of the rashi of aries is governed by Shukr: Venus but also by Yami and Yama in vedic mythology who are twins and gods respectfully of life and death.

Yama, the main deity of Bharani is said to be one of "8 celestial gatekeepers, who guards eight directional doorways or exits through which souls travel from an earthly plane to other planes of existence" making him the lord of Dharma since at one's death, he decides basing on his actions in what plane should one reincarnate.

Since Yama is responsible for directing the flow of life on Earth the association between bharani and the yoni becomes evident: the female reproducting system serves as a portal for souls to take on a physical form. So bharani as Claire Nakti perfectly described it relates to the feminine ability to receive, hold, nurture and ultimately transform through the womb.

Because Bharani aligns itself with all the feminine qualities by excellence it makes sense as to why Venus is it's ruler.

Venus is the roman name for the goddess Aphrodite: in greek mythology. She is said to be the goddess of love and beauty at large but also the goddess of war and sexuality. First because the ancient greeks saw the duality that links love to war and how they seem to come together through sex.

Also, Aphrodite is said to be born from the sperm of Ouranos when his testicules got cut by his son Saturn as he was always feconding Gaia, the Earth and causing her distress: he was acting cruel regarding their children. The sperm of Ouranus got mixed up with the foam of the Ocean creating Aphrodite which means "risen from the foam". So it was interesting to see that as Shukr also means sperm in sanskrit and it shows the origin of Venus as a fertility goddess too.

This conception of Aphrodite directly links her to ancient goddesses of love such as Ishtar or Inana in Mesopotamian/summerian mythology or Isis in egyptian mythology. Most of the time, these goddesses are the female counterpart of a god that was once mortal, got cursed, died and then came back to life for them to form an immortal couple.

In the case of Ishtar, her consort is Dumuzi or Tammuz and Osiris is the consort of Isis.

In Mesopotamian mythology :

Ishtar or Inana in sumerian is the goddess of love and sexuality, beauty, fertility as well as war because of her status as a " bloody goddess" mostly refering to her character in plenty of myths.

For example: in one story, she became infatuated with the king Gilgamesh, but the latter knowing her fierce reputation, refused her advances. As a result she got furious and unleashed the celestial Bull on Earth which resulted in 7 years of plagues. This celestial bull was later defeated by Gilgamesh and Endiku, and its corpse was throwed in front of Inana. Blinded by rage, she decided that as a punition Enkidu must die and sad at the death of his bestfriend Gilgamesh began his journey to find a cure to Death.

Bharani is a fierce or Ugra nakshatra meaning that its nature is agressive, bold and assertive in pursuing their goals. They are ruthless in the process of accompling what they desire the most and are inclined to extreme mood swings that can result in them to be "blinded" by their extreme emotions perfectly expressing the passionate character of Venus and her other equivalents in differents pantheons of antiquity.

Inana/ Ishtar's story with Dumuzi/Tammur begins as she was convinced to chose him by her brother Utu. Then she got married with the shepphard Dumuzi instead of whom she prefered the farmer: Enkinmdou. During the courtship, Inana prefered the fine textile of the farmer and his beer rather than the thick wool and milk of Dumuzi. The preference for the shepphard illustrates that at the time the Mesopotamian civilisation was known for their proliferent agriculture with the egyptians in the region, so this myth encapsulate the opposition between nomads and sendatary people at this specifific time period.

By the way, another symbol of Bharani is the cave and traditionnaly, the cave was used as a storage room for food. Also Bharani's purpose is Artha so these individuals are motivated to accumalate resources and provide safety and security, so Bharani can be linked to the exploitation of natural ressources like the soil illustrating the preference of Ishtar for the farmer. This is reinforced also by its Earth element.

So coming back to the myth, in a mesopotamian text called Inana's Descent to the Underworld, the goddess goes to Kur (hell) with the intent of conquering it, and her sister Ereshkigal who rules the Underworld, kills her. She learns that she can escape if she finds a sacrifice to replace her, in her search, she encounters servants who were mourning her death however she finds Dumuzi relaxing on a throne being entertained by enslaved girls. Enraged by his disloyalty she selects him as a sacrifice and he is dragged to the Underworld by demons.

He is eventually resurrected by Inana and they become an "immortal couple" as he may only come back to life for half of the year, being replaced by his son (?) who is also his reincarnation for the other half of the same years, so describing the cycle of regeneration of life.

Other mythologycal stories of goddesses in the near east describe a similar patterns:

The goddess Asherah is described as being the mother and the lover of her son Adonis.

The goddess Cybele in the phrygian pantheon takes the form of an old woman as she described as the mother of everything and of all. And at the same time she is the consort of Attis who his her own son (wtf ?)

Also, Yama and Yami are implicated in a incestuous entanglement where his sister Yama wanted to lay with him however he refused establishing himself as a god with an infaillible moral campus.

All of these representations illustrate the relation between the masculine and the feminine, life and regenration which are all topics related to Bharani nakshatra. Women by their capacity to give life are seen as the source of life and therefore are eternal as they are able to regenarate themselves through daughters which are identical to them whereas man who is unable to reproduce by himself, is therefore mortal feels the need to associate with her to resurrect through a son who is identical to him. Bharani exiting as the embodiment of the link between "the father and the offspring" which is the feminine vessel.

So this is certainly part 1, I think that these ancient myths are where Claire Nakti found her inspiration for her series on Bharani.

#vedic astrology#cinema#coquette#astrology#vintage movies#aesthetic#coquette dollete#fashion#vintage#movies#greek mythology#roman mythology#ancient egypt#bharani#chitra nakshatra#purva bhadrapada#purva phalguni#cowboy carter#venus#adonis

198 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Iktomi Tales

Iktomi (also known as Unktomi) is a trickster figure of the lore of the Lakota Sioux nation similar to tricksters of other nations, such as Wihio of the Cheyenne, Nanabozho (Manabozho) of the Ojibwe, Coyote of the Navajo, or Glooscap of the Algonquin. As a trickster, he may cause harm or good but always brings transformation.

The concept of transformation is relayed in the form of a lesson learned either by himself or another character in the story that teaches the audience any one of several lessons including respect for nature, the importance of telling the truth, recognizing falsehood, being content with what one has, respect for oneself and one's community, and many others. These stories always encourage recognition of some important cultural value either by illustrating the concept in action or showing the consequences of violating it. Iktomi sometimes appears as a spider, sometimes as a man (a Sioux hunter, warrior, or sage), and is variously known as Ictinike, Ikto, Unktome, and most famously Unktomi by the different bands of the Sioux.

When the character was created or how old the stories are is unknown. The tales were passed down orally, generation to generation, until they were written down by European and Euro-American settlers, primarily in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Native American writers began to record their nation's legends, and those of others, at about this same time, including the Iktomi tales.

Iktomi the Trickster

Iktomi often interacts with Coyote, who sometimes serves as the trickster figure while Iktomi is the one taught the lesson (just as Ma'ii, the coyote figure of the Navajo, does in those stories). There are many variations on the Iktomi character, and when first introduced at the beginning of a story, the audience has no idea what part he is going to play. The story itself, therefore, mirrors the changeable nature of the character. In one piece, he will be the villain, in another the hero, in another a sage mediator, and in another a clown or buffoon.

In The Bound Children, for example, Iktomi is the sage who mediates a dispute between members of the community, while in White Plume, he is the villain who tries to steal the hero's identity and claim the beautiful maiden as his own. In the two tales that follow, Unktomi and the Arrowheads and Iktomi and the Coyote, the character is presented as a helper who is mistreated and as a buffoon who cannot tell the difference between a living animal and a dead one, respectively. Unktomi and the Arrowheads encourages respect for other living things, while the moral of Iktomi and the Coyote would be similar to the old adage, "don't count your chickens until they hatch."

Iktomi tales were, and still are, among the most popular Sioux legends as they are always entertaining while also providing an important cultural, religious, or common-sense moral. In this, they share ground with trickster tales of any culture, ancient or modern, around the world as trickster figures in general often drive the narrative of some of the most engaging texts, as with Loki in Norse mythology, Hermes in Greek mythology, or Reynard the Fox in European medieval folklore, among many others. Regarding such figures, scholar Larry J. Zimmerman writes:

Despite the different guises, the trickster exhibits similar characteristics wherever he is encountered. He can be a crafty joker and a bungler, who is usually undone by his own horseplay or trickery, ending up injured or even dead – only to rise again, seemingly none the wiser for his experience. At times irreverent and idiotic, his doings entertainingly highlight the importance of moral rules and boundaries.

(188)

The cultural importance of the trickster figure was recognized by the Swiss psychiatrist Carl Jung (l. 1875-1961), who included the concept in his archetypes as a psychological manifestation of one's juvenile and immature impulses, which, even so, should be acknowledged as, through its expression, one can recognize important personal truths. The trickster in Jung's work is an avatar, challenging how one defines oneself and offering the opportunity for change and growth. The Iktomi tales illustrate Jung's concept well in offering their audience the same possibility of seeing the world, and themselves, in a different light.

Continue reading...

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

Emotional Archetypes: Understanding the Mythological Creatures Within Us

Human emotions are complex, multifaceted, and deeply rooted in our psyche. From joy and love to fear and anger, these feelings shape our thoughts, behaviors, and interactions. Throughout history, different cultures have sought to understand and represent these emotions through mythology, creating creatures and figures that embody the very essence of our inner world. These emotional archetypes, manifested as mythological beings, offer profound insights into the human experience. By exploring these symbolic figures, we can gain a deeper understanding of our own emotions and how they influence our lives.

The Role of Archetypes in Mythology

Archetypes are universally recognized symbols or patterns that recur across different cultures and historical periods. In mythology, these archetypes often take the form of gods, monsters, and spirits that personify various aspects of the human condition. For example, in Greek mythology, the god Ares represents the destructive power of war and rage, while Aphrodite embodies love and beauty. These mythological figures are not just characters in stories; they are symbolic representations of the emotions and instincts that drive human behavior.

By personifying emotions as mythological creatures, ancient cultures created a framework for understanding the complexities of the human psyche. These archetypes served as tools for reflection, allowing individuals to explore their emotions and experiences through the lens of storytelling. In many ways, these figures acted as mirrors, reflecting the deepest parts of ourselves.

Emotional Archetypes in Modern Culture

While the specific mythological figures may vary, the concept of emotional archetypes persists in modern culture. Today, we continue to use symbolic representations to understand and process our emotions. Characters in literature, film, and art often embody specific emotions or psychological states, helping us to explore our own feelings in a more tangible way.

For example, the character of The Hulk in the Marvel Universe is a modern embodiment of uncontrollable anger and rage. His transformation into a powerful, destructive force mirrors the experience of being overwhelmed by these intense emotions. Similarly, the figure of the angel in many religious and cultural traditions represents hope, purity, and protection, serving as a symbol of our highest ideals and aspirations.

These modern emotional archetypes, like their ancient counterparts, help us navigate the complexities of our emotional lives. They offer a way to externalize and understand feelings that might otherwise be difficult to articulate.

The Therapeutic Power of Emotional Archetypes

Recognizing and engaging with emotional archetypes can be a powerful tool for personal growth and healing. By identifying with a particular mythological figure or archetype, individuals can gain insight into their emotional patterns and behaviors. This process can be especially helpful in therapy, where exploring these archetypes can lead to a deeper understanding of one's emotions and motivations.

For instance, someone who struggles with anger might benefit from exploring the archetype of a mythological figure like Ares or The Hulk. By understanding the symbolism behind these figures, the individual can begin to unravel the sources of their anger and develop healthier ways to manage it. Similarly, someone seeking to cultivate more compassion and empathy might resonate with the archetype of a benevolent figure like an angel or goddess of mercy.

Conclusion

Emotional archetypes, whether rooted in ancient mythology or modern culture, offer a unique lens through which we can explore and understand our emotions. These symbolic figures provide a language for the inner world, allowing us to navigate the complexities of our feelings with greater clarity and insight. By engaging with these archetypes, we can gain a deeper understanding of ourselves and our place in the world, leading to greater emotional intelligence and personal fulfillment.

Unlock the secrets of your emotions with Nancy Vallette’s captivating series, starting with Figments of Persuasion. Dive into a world where mythological creatures embody the complex emotions we all experience. Whether it’s the balance between Sinisters and Benevolents in your life or the journey of discovering your own unique Figments, these books offer a profound exploration of the feelings that shape us. Bring these Figments to life with the Field Guide to the Sinisters and Benevolents and enhance your understanding of these emotional archetypes. Then, immerse yourself in creativity with the accompanying coloring books, where you can personalize your Figments, making them truly your own. Don’t just feel your emotions—understand them, visualize them, and engage with them through this beautifully crafted series. Order now from this link: https://amz.run/9TXO and start your journey into the mythological creatures within you!

0 notes

Text

Virupaksha Temple: A Journey Through History and Devotion

In the heart of Hampi, Karnataka, the Virupaksha Temple stands as a living monument to centuries of devotion and architectural brilliance. Dedicated to Lord Shiva, this ancient temple offers a unique journey through the annals of history and the profound depths of spiritual devotion. Its storied past and sacred presence make it a significant landmark, not only for pilgrims but also for those interested in the rich tapestry of India’s cultural heritage.

A Historical Overview

The origins of the Virupaksha Temple date back to the 7th century, making it one of the oldest functioning temples in India. The temple’s history is deeply intertwined with the rise and fall of empires, particularly the Vijayanagara Empire, which significantly enhanced and expanded the temple complex in the 16th century. Under the patronage of King Krishnadevaraya, the temple saw considerable architectural development, transforming it into a grand edifice that reflects the artistic and spiritual fervor of the time.

Architectural Brilliance

The Virupaksha Temple is renowned for its impressive Dravidian architecture, characterized by its towering gopurams (gateway towers), intricately carved pillars, and expansive courtyards. The main gopuram, rising about 50 meters, is a striking feature of the temple’s façade, adorned with elaborate sculptures that narrate stories from Hindu mythology. The grandeur of this entrance serves as a fitting prelude to the intricate beauty within.

The Sanctum Sanctorum

At the heart of the temple lies the sanctum sanctorum, where the deity Lord Virupaksha is enshrined. This sacred space is the focal point of worship, where devotees gather to offer prayers and seek divine blessings. The sanctum’s design reflects a deep understanding of sacred geometry and spiritual symbolism, creating a serene environment conducive to meditation and devotion.

A Living Tradition of Worship

The Virupaksha Temple has been a center of devotion for centuries, and its religious practices continue to thrive today. Daily rituals and ceremonies, performed with great reverence, include the morning Suprabhatam (wake-up call), abhishekams (ritual bathing), and various offerings. These rituals are an integral part of the temple’s spiritual life, connecting devotees with a tradition that has been maintained over generations.

Historical and Cultural Significance

The Virupaksha Temple is not only a religious center but also a cultural landmark. Its historical significance is reflected in its role as a pivotal site in Hampi’s urban planning. The temple was strategically located at the convergence of major trade routes and water sources, underscoring its importance in the social and economic life of the Vijayanagara Empire.

Preservation and Legacy

As a UNESCO World Heritage Site, the Virupaksha Temple is protected and preserved as a crucial part of India’s cultural and historical legacy. Conservation efforts ensure that the temple’s architectural and artistic treasures are maintained for future generations to appreciate and learn from. The temple’s continued reverence and use in contemporary worship also contribute to its enduring legacy.

Conclusion

A visit to the Virupaksha Temple is more than just a journey to a sacred site; it is an exploration of India’s rich history and spiritual heritage. From its architectural grandeur to its vibrant rituals and festivals, the temple offers a profound connection to the past and a deep sense of devotion. As a testament to centuries of faith and artistry, the Virupaksha Temple stands as a beacon of spiritual and cultural significance, inviting all who visit to experience its timeless allure.

0 notes

Text

Puri Temple Tour Package: Explore Spiritual Heritage

Nestled along the serene coastline of Odisha, Puri is a city steeped in spiritual significance and historical grandeur. Known for its sacred temples and vibrant cultural heritage, Puri offers a unique opportunity for travelers to delve into India’s rich spiritual traditions. A Puri tour package focused on temple exploration can provide a profound and enlightening experience, allowing visitors to connect with the city’s deep-rooted spiritual heritage.

The Spiritual Significance of Puri

Puri’s reputation as a spiritual epicenter is anchored in its array of historic temples, each offering a unique glimpse into Hindu religious practices and architectural splendor. A Puri tour package designed around temple visits ensures that you experience the city’s spiritual essence in a comprehensive and immersive manner.

Jagannath Temple: At the heart of any Puri tour package is a visit to the iconic Jagannath Temple, one of the Char Dham pilgrimage sites. Dedicated to Lord Jagannath, a form of Lord Vishnu, this temple is renowned for its grand architecture, intricate carvings, and the massive Rath Yatra (Chariot Festival) that draws thousands of devotees each year. The temple’s vibrant atmosphere and sacred rituals offer a deep dive into the religious practices and communal spirit of Hinduism.

Loknath Temple: Another highlight of a Puri tour package is a visit to the Loknath Temple. This ancient shrine is dedicated to Lord Shiva and is known for its tranquil setting and significant spiritual history. The temple’s serene environment and religious practices provide a contemplative space for reflection and connection with divine energies.

Gundicha Temple: Located a short distance from the Jagannath Temple, the Gundicha Temple is another essential stop on a Puri tour package. This temple is closely associated with the Rath Yatra, as it is the place where the Jagannath deity is taken during the festival. The temple’s historical and religious importance makes it a vital part of any spiritual journey in Puri.

Sakshi Gopal Temple: Known for its fascinating legend and architectural beauty, the Sakshi Gopal Temple is an intriguing addition to a Puri tour package. Dedicated to Lord Krishna, this temple is associated with a story of devotion and justice, reflecting the rich tapestry of Hindu mythology and cultural values.

Enhancing Your Spiritual Experience

A Puri tour package centered on temple exploration can be further enhanced with a range of activities that deepen your understanding and connection with Hindu spiritual practices:

Guided Temple Tours: Opting for guided tours as part of your Puri tour package ensures that you gain insightful knowledge about each temple’s history, architecture, and religious significance. Expert guides can offer valuable context and enrich your visit with stories and explanations that bring the spiritual heritage to life.

Participating in Rituals: Engaging in local rituals and ceremonies can provide a more immersive experience. Many Puri tour packages include opportunities to witness or participate in traditional worship practices, offering a unique perspective on the devotional aspects of Hinduism.

Cultural Workshops: Enhance your spiritual journey with workshops that explore Hindu philosophy, art, and traditions. These sessions, often included in specialized Puri tour packages, can provide deeper insights into the cultural and spiritual fabric of the region.

Meditation and Reflection: Incorporating sessions of meditation or reflective practices into your Puri tour package can help you connect with the spiritual energy of the temples. Puri’s serene environment offers an ideal backdrop for contemplation and inner peace.

Conclusion

A Puri tour package focused on temple exploration offers a transformative journey into the spiritual heritage of one of India’s most revered cities. By visiting iconic temples like the Jagannath Temple, Loknath Temple, and Gundicha Temple, travelers can immerse themselves in the rich traditions and practices that define Puri’s spiritual landscape. Whether through guided tours, participation in rituals, or cultural workshops, a well-curated Puri tour package provides a comprehensive and enriching experience, making it an ideal choice for those seeking to explore the depths of Hindu spirituality and heritage.

0 notes

Text

Oral history - Brazilian indigenous mythology.

The main ones are curupira; that of the iara; that of the pink button; cassava; that of boitatá; that of the pirarucu; that of guarana; the caipora; that of the water lily; that of saci-pererê; that of Matinta Perera; and that of uirapuru.

Example: The pink dolphin is a legend of Brazilian folklore, being very influential in the northern region of the country. It talks about a button that transforms into a beautiful and seductive man. In human form, the boto seduces women to impregnate them. These women are abandoned by the being, who returns to the river in his animal form.

It is incredibly rich and diverse, reflecting the vast cultural diversity of the indigenous tribes that inhabited and still inhabit Brazilian territory. It is made up of a wide range of myths, legends, rituals and beliefs that have been passed down orally over generations.

It is deeply connected to nature and natural elements, reflecting the strong spiritual relationship that indigenous cultures maintain with the environment. Animals, plants, rivers, and mountains often play significant roles in stories and are considered sacred entities.

Furthermore, deities and supernatural entities in indigenous mythology often personify forces of nature, such as the sun, moon, thunder, and the spirits of ancestors. These entities are often revered and invoked in religious rituals and shamanic ceremonies.

Each indigenous ethnic group has its own distinctive mythology, transmitted through oral traditions and ritual practices. This diversity reflects not only Brazil's geographic and environmental differences, but also the diverse historical and cultural experiences of indigenous tribes over time.

Brazilian indigenous mythology is a cultural and spiritual treasure that offers valuable insights into the worldview and values of indigenous communities, as well as the complexity and beauty of the relationship between human beings and nature. It is important to recognize, respect and preserve this rich cultural heritage as an integral part of Brazilian identity. #edisonmariotti @edisonblog

.br

Historia oral - A mitologia indígena brasileira.

As principais são a do curupira; a da iara; a do boto-cor-de-rosa; a da mandioca; a do boitatá; a do pirarucu; a do guaraná; a da caipora; a da vitória-régia; a do saci-pererê; a da Matinta Perera; e a do uirapuru.

Exemplo: O boto-cor-de-rosa é uma lenda do folclore brasileiro, sendo muito influente na região Norte do país. Fala de um boto que se transforma em um homem belo e sedutor. Na forma humana, o boto seduz mulheres para engravidá-las. Essas mulheres são abandonadas pelo ser, que retorna para o rio em sua forma animal.

É incrivelmente rica e diversa, refletindo a vasta diversidade cultural das tribos indígenas que habitaram e ainda habitam o território brasileiro. Ela é composta por uma ampla gama de mitos, lendas, rituais e crenças que foram transmitidos oralmente ao longo de gerações.

Está profundamente conectada à natureza e aos elementos naturais, refletindo a forte relação espiritual que as culturas indígenas mantêm com o meio ambiente. Os animais, plantas, rios e montanhas frequentemente desempenham papéis significativos nas histórias e são considerados entidades sagradas.

Além disso, as divindades e entidades sobrenaturais na mitologia indígena frequentemente personificam forças da natureza, como o sol, a lua, o trovão e os espíritos dos antepassados. Essas entidades muitas vezes são reverenciadas e invocadas em rituais religiosos e cerimônias xamânicas.

Cada grupo étnico indígena possui sua própria mitologia distintiva, transmitida através de tradições orais e práticas rituais. Essa diversidade reflete não apenas as diferenças geográficas e ambientais do Brasil, mas também as diversas experiências históricas e culturais das tribos indígenas ao longo do tempo.

A mitologia indígena brasileira é um tesouro cultural e espiritual que oferece insights valiosos sobre a visão de mundo e os valores das comunidades indígenas, bem como sobre a complexidade e a beleza da relação entre seres humanos e natureza. É importante reconhecer, respeitar e preservar essa rica herança cultural como parte integrante da identidade brasileira.

1 note

·

View note

Text

A response to the “Athena is a victim blamer and hates women” crowd

The idea that Athena punishes victims of rape is very popular in today’s culture because of how famous Ovid’s retelling of the Medusa myth has gotten. It hurts me that people think that Athena hates assault victims because of 1 (one) story written by a man who hated authority figures and wanted to slander the gods.

Before Ovid’s Metamorphoses (which is part of Roman mythology, not Greek mythology fyi), all of the mythology regarding Medusa said that she was born a monster. She wasn’t a beautiful woman who was assaulted and no one transformed her. She was a sister of Echidna, a monster born from a family of monsters. Ovid’s tale of Medusa is a fictional story that has no basis on greek culture and that he wrote to push a political narrative. If you want to learn how Athena acted in actual greek mythology, here are some stories for you:

- When Ajax The Lesser raped Cassandra at a temple of Athena, Athena punished him and the greeks who failed to chastise him by sending a storm that sank their fleet. Ajax was shipwrecked and drowned, while his people, the (historical) Opuntians, were told by Apollo that to appease the goddess they would have to send maidens to the Trojan land for the next 1000 years, when the maidens arrived there they became priestesses of Athena.

- In Hyginus’ Fabulae, when the princess Nyctimene was found crying in the woods because her own father had raped her, Athena transformed her into her sacred owl and appointed her as her animal companion.

- In Ovid’s Metamorphoses (I’m only using this as a source to show how selective people are), Coroneis, princess of Phokis, was chased down by Poseidon. She cried out to Athena and the goddess transformed her into a crow to save her from the rape.

- For Hera’s sake, Athena IS a victim of attempted rape. In mythology, Hephaestus tried to force himself on her and she fought him off. The myth explicitly says that she felt disgusted by this.

Besides Ovid’s Metamorphoses Book 4, in every other myth about Athena and rape she is completely against it, protects the woman in danger and punishes the rapist.

Also, let’s talk about how in ancient times the cult of Athena was a escapeway for women. “The cult of Athena provided women in ancient Greece not only with a purpose outside the home and childbearing but a significant role in the life of the city. In the Athenian culture, which regularly suppressed feminine energy, even while celebrating it through their patron deity, Athena’s cult was an opportunity for women to express themselves, be recognized, and contribute to the religious and cultural life of the city.” (World History Encyclopedia, Joshua J. Mark)

In the Parthenon, a famous temple of Athena, there was a statue of Pandora, the first of womankind, where she was honored. (Pausanias, Description of Greece 1. 24. 5)

It’s worth noting that 99% of the sources that we have about ancient greece were written by aristocratic men, we have little to no idea of how women viewed and worshipped the gods. To sum it up, before y’all call Athena an anti-feminist, a rape enabler, or a victim blamer PLEASE read actual mythology and put some respect on Athena Axiopoenus (the avenger against injustice)’s name <3

#greek mythology#greek gods#hellenic polytheism#hellenic worship#athena deity#athena worship#athenadeity#medusa

571 notes

·

View notes

Text

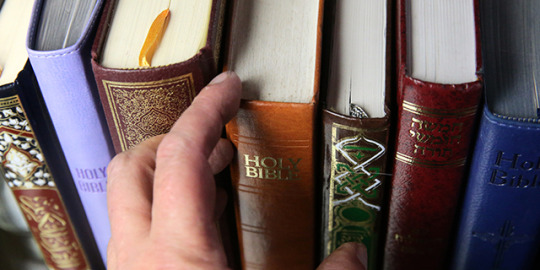

Divinum Pacis’s Reference Guide- UPDATED 2021

Let’s face it, schooling is expensive, and you can’t cram everything you want to know into 4+ years. It takes a lifetime (and then some). So if you’re like me and want to learn more, here’s an organized list of some books I find particularly insightful and enjoyable. NEW ADDITIONS are listed first under their respective sections. If you have any recommendations, send them in!

African Religions 🌍

African Myths & Tales: Epic Tales by Dr. Kwadwo Osei-Nyame Jnr

The Ancient Egyptian Book of the Dead: Prayers, Incantations, and Other Texts from the Book of the Dead by E.A. Wallis Budge

Prayer in the Religious Traditions of Africa by Aylward Shorter (a bit dated but sentimental)

The Holy Piby: The Black Man’s Bible by Shepherd Robert Athlyi Rogers

The Altar of My Soul: The Living Traditions of Santeria by Marta Moreno Vega (autobiography of an Afro-Puerto Rican Santeria priestess)

African Religions: A Very Short Introduction by Jacob K. Olupona

Buddhism ☸

The Heart of the Buddha's Teaching: Transforming Suffering into Peace, Joy, and Liberation by Thich Nhat Hanh

The Dhammapada by Eknath Easwaran (collection of Buddha’s sayings)

Liquid Life: Abortion and Buddhism in Japan by William R. LaFleur

The Tibetan Book of the Dead by John Baldock (the texts explained and illustrated)

Teachings of the Buddha by Jack Kornfield (lovely selection of Buddhist verses and stories)

Understanding Buddhism by Perry Schmidt-Leukel (great introductory text)

Essential Tibetan Buddhism by Robert Thurman (collection of select chants, prayers, and rituals in Tibetan traditions)

Christianity ✝️

The Story of Christianity Volume 1: The Early Church to the Dawn of the Reformation by Justo L. Gonzales

The Story of Christianity Volume 2: The Reformation to Present Day by Justo L. Gonzales

By Heart: Conversations with Martin Luther's Small Catechism by R. Guy Erwin, etc.

Introducing the New Testament by Mark Allen Powell

Who’s Who in the Bible by Jean-Pierre Isbouts (really cool book, thick with history, both Biblical and otherwise)

Synopsis of the Four Gospels (RSV) by Kurt Aland (shows the four NT gospels side by side, verse by verse for easy textual comparison)

Behold Your Mother by Tim Staples (Catholic approach to the Virgin Mary)

Mother of God: A History of the Virgin Mary by Miri Rubin (anthropological and historical text)

Systematic Theology by Thomas P. Rausch

Orthodox Dogmatic Theology by Fr. Michael Romazansky (Eastern Orthodox Christianity)

Diary of Saint Maria Faustina Kowalska (very spiritual)

The Names of God by George W. Knight (goes through every name and reference to the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit in the Bible)

Icons and Saints of the Eastern Orthodox Church by Alfredo Tradigo (for those who like art history AND religion)

The Orthodox Veneration of the Mother of God by St. John Maximovitch (the Orthodox approach to the Virgin Mary)

East Asian Religions ☯️

Shinto: A History by Helen Hardacre

Tao Te Ching by Chad Hansen (a beautiful, illustrated translation)

The Analects by Confucius

Tao Te Ching by Stephen Mitchell

Shinto: The Kami Way by Sokyo Ono (introductory text)

Understanding Chinese Religions by Joachim Gentz (discusses the history and development of Taoism, Confucianism, and Buddhism in China)

Taoism: An Essential Guide by Eva Wong (pretty much everything you need to know on Taoism)

European (various)

Iliad & Odyssey by Homer, Samuel Butler, et al.

Tales of King Arthur & The Knights of the Round Table by Thomas Malory, Aubrey Beardsley, et al.

Early Irish Myths and Sagas by Jeffrey Gantz

The Prose Edda: Norse Mythology by Snorri Sturluson and Jesse L. Byock

Mythology by Edith Hamilton (covers Greek, Roman, & Norse mythology)

The Nature of the Gods by Cicero

Dictionary of Mythology by Bergen Evans

Gnosticism, Mysticism, & Esotericism

The Gnostic Gospels: Including the Gospel of Thomas, the Gospel of Mary Magdalene (Sacred Texts) by Alan Jacobs and Vrej Nersessian

The Kybalion by the Three Initiates (Hermeticism)

The Freemasons: The Ancient Brotherhood Revealed by Michael Johnstone

Alchemy & Mysticism by Alexander Roob (Art and symbolism in Hermeticism)

The Gnostics: Myth, Ritual, and Diversity in Early Christianity by David Brakke

What Is Gnosticism? Revised Edition by Karen L. King

The Essence of the Gnostics by Bernard Simon

The Essential Mystics: Selections from the World’s Great Wisdom Traditions by Andrew Harvey (covers Jewish, Christian, Muslim, Greek, Hindu, Buddhist, and Taoist traditions)

The Secret Teachings of All Ages by Manly P. Hall (huge book on esoteric and occult religions)

Freemasonry for Dummies by Christopher Hodapp

Hinduism 🕉

The Ramayana by R.K. Narayan

7 Secrets of Vishnu by Devdutt Pattanaik (all about Vishnu’s various avatars)

7 Secrets of the Goddess by Devdutt Pattanaik (all about Hindu goddesses, myths and symbolism)

Hinduism by Klaus K. Klostermaier (good introductory text)

Bhagavad Gita As It Is by Srila Prabhupada (trans. from a religious standpoint)

The Mahabharata, parts 1 & 2 by Ramesh Menon (super long but incredibly comprehensive)

The Upanishads by Juan Mascaro (an excellent introductory translation)

In Praise of the Goddess by Devadatta Kali (the Devi Mahatmya with English & Sanskrit texts/explanations of texts)

Beyond Birth and Death by Srila Prabhupada (on death & reincarnation)

The Science of Self-Realization by Srila Prabhupada

Krishna: The Beautiful Legend of God (Srimad Bhagavatam) by Edwin F. Bryant (totally gorgeous translation)

The Perfection of Yoga by Srila Prabhupada (about “actual” yoga)

Islam ☪️

The Handy Islam Answer Book by John Renard (a comprehensive guide to all your questions)

The Illustrated Rumi by Philip Dunn, Manuela Dunn Mascetti, & R.A. Nicholson (Sufi poetry)

Islam and the Muslim World by Mir Zohair Husain (general history of Islam)

The Quran: A Contemporary Understanding by Safi Kaskas (Quran with Biblical references in the footnotes for comparison)

Essential Sufism by Fadiman & Frager (select Sufi texts)

Psychological Foundation of the Quran, parts 1, 2, & 3 by Muhammad Shoaib Shahid

Hadith by Jonathan A.C. Brown (the history of Hadith and Islam)

The Story of the Quran, 2nd ed. by Ingrid Mattson (history and development of the Quran)

The Book of Hadith by Charles Le Gai Eaton (a small selection of Hadith)

The Holy Quran by Maulana Muhammad Ali (Arabic to English translation, the only translation I’ve read cover-to-cover)

Mary and Jesus in the Quran by Abdullah Yusuf’Ali

Blessed Names and Attributes of Allah by A.R. Kidwai (small, lovely book)

Jainism & Sikhi

Understanding Jainism by Lawrence A. Babb

The Jains (The Library of Religious Beliefs and Practices) by Paul Dundas

The Forest of Thieves and the Magic Garden: An Anthology of Medieval Jain Stories by Phyllis Granoff

A History of the Sikhs, Volume 1: 1469-1839 (Oxford India Collection) by Khushwant Singh

Sikhism: A Very Short Introduction by Eleanor Nesbitt

Judaism ✡

Hebrew-English Tanakh by the Jewish Publication Society

Essential Judaism by George Robinson (this is THE book if you’re looking to learn about Judaism)

The Talmud: A Selection by Norman Solomon

Judaism by Dan & Lavinia Cohn-Sherbok (introductory text)

The Jewish Study Bible, 2nd edition by the Jewish Publication Society (great explanations of passages)

The Hebrew Goddess by Raphael Patai

Native American

God is Red: A Native View of Religion, 30th Anniversary Edition by Vine Deloria Jr. , Leslie Silko, et al.

The Wind is My Mother by Bear Heart (Native American spirituality)

American Indian Myths and Legends by Erdoes & Ortiz

The Sacred Wisdom of the Native Americans by Larry J. Zimmerman

Paganism, Witchcraft & Wicca

Magic in the Roman World: Pagans, Jews and Christians (Religion in the First Christian Centuries) 1st Edition by Naomi Janowitz

The Greek Magical Papyri in Translation: Including the Demotic Spells: 2nd Edition by Hans Dieter Betz

Wicca for Beginners: Fundamentals of Philosophy & Practice by Thea Sabin

The Path of a Christian Witch by Adelina St. Clair (the author’s personal journey)

Aradia: Gospel of the Witches by C.G. Leland

The Anthropology of Religion, Magic, & Witchcraft, 3rd ed. by Rebecca L. Stein

Paganism: An Introduction to Earth-Centered Religions by Joyce & River Higginbotham

Christopaganism by Joyce & River Higginbotham

Whispers of Stone by Tess Dawson (on Modern Canaanite Paganism)

Social ☮

Tears We Cannot Stop (A Sermon to White America) by Eric Michael Dyson (concerning racism)

Comparative Religious Ethics by Christine E. Gudorf

Divided by Faith by Michael O. Emerson (on racism and Christianity in America)

Problems of Religious Diversity by Paul J. Griffiths

Not in God’s Name by Rabbi Jonathan Sacks (on religious terrorism)

The Sacred and the Profane by Mircea Eliade (difficult but worthwhile read)

World Religions 🗺

Understanding World Religions by Len Woods (approaches world religions from a Biblical perspective)

Living Religions, 9th ed. by Mary Pat Fisher (introductory textbook)

The Norton Anthology of World Religions: Hinduism, Buddhism & Daoism by Jack Miles, etc.

The Norton Anthology of World Religions: Judaism, Christianity, & Islam by Jack Miles, etc.

Zoroastrians: Their Religious Beliefs and Practices by Mary Boyce

The Baha’i Faith by Moojan Momen (introductory text)

Saints: The Chosen Few by Manuela Dunn-Mascetti (illustrated; covers saints from Christianity, Islam, Hinduism, and more)

The Great Transformation by Karen Armstrong (the evolutionary history of some of the world’s greatest religions)

Roman Catholics and Shi’i Muslims: Prayer, Passion, and Politics by James A. Bill (a comparison of the similarities between Catholicism & Shi’a Islam)

God: A Human History by Reza Aslan (discusses the evolution of religion, specifically Abrahamic and ancient Middle Eastern traditions)

A History of God by Karen Armstrong (similar to Aslan’s book but much more extensive)

The Perennial Dictionary of World Religions by Keith Crim

#religion#world religions#reference#judaism#christianity#islam#hinduism#buddhism#jainism#sikhism#paganism#witchcraft#wicca#library#divinum-pacis

228 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Art of the Hex: The Witch in the Movies.

The concept of witch arises in the Babylonian culture to refer to the woman who practices a “black magic” contrary to institutionalized religious precepts, a crime that in the Code of Hammurabi was punished by throwing the guilty into the river (Hormigos Vaquero: 2007,477 ). The image of women flying, with powers that transform people into animals, causing them physical damage or tremendous pain have haunted the witches.

In the cinema, the figure of the witch is an inexhaustible topic, it has several facets: the sensual and attractive sorceress who seduces, with her beauty, embodies the young Circe who in the Odyssey dupes Odysseus and transforms her companions into pigs .

The witch is powerful in that she combines charm and knowledge, establishes contact with the devil through orgies and rituals, and sometimes becomes his priestess, as can be seen in films such as Witchcraft Through Ages (Haxan) or The Undead. The other facet is to present her with a horrible appearance, rejected and feared for the excessive use of her knowledge and tendency for destruction.

In Argento's filmography we find Suspiria, which is part of a trilogy that the director himself put together from his literary influence, especially Thomas de Quincey's story about three mothers, Mater Lachrymarum (Tears), Mater Suspiriorum (Sighs) and Mater Tenebrarum (Darkness).

Like the Fates, in Greek mythology there are three sisters: Clotho, Lachesis and Atropos. The first grants the threads of each person's life; the second, intertwine the threads and decide how long the thread of each person's life will be; finally, the third is in charge of cutting the thread and, thereby, ending the person's existence.

Suspiria is a mysterious breath of life, all the tectonic power embodied in a female being that is nourished by the young energy of the students of an academy that is the heart of Suspiria the destructive mother. Its hidden existence as a dangerous shadow veils the dream of the young women. Suspiria is an evil witch, a demonic entity.

In Black Sunday Barbara Steele plays a sorceress named Asa Vajda who seems to harbor not a drop of humanity inside her when she returns 200 years after her death to wreak havoc on her execrable brother's family. It also presents itself as the enemy of good, of the order established by patriarchal institutions that undermine by all means the development of dissatisfied women and the propagation of their ideas.

Always fought through violent actions and methods, let us remember the scene where the mask is nailed at the point of mallets. Currently, productions such as The Lords of Salem or Las Brujas de Zugarramurdi demonstrate once again the renewed validity of the witch on the screen.

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

Why Did Medusa Get Cursed?

Although Hesiod gives an account of Medusa’s origins and the death of Medusa at the hands of Perseus, he does not say more about her. By contrast, a more comprehensive account of Perseus and Medusa can be found in Ovid’s Metamorphoses. In this work, Ovid describes Medusa as originally being a beautiful maiden. Her beauty caught the eye of Poseidon, who desired her and proceeded to ravage her in Athena’s shrine. When Athena discovered the sea god had ravaged Medusa in her shrine she sought vengeance by transforming Medusa’s hair into snakes, so that anyone who gazed at her directly would be turned into stone.

I look at this as a classic depiction of the victim of sexual assault being unjustly punished for having been assaulted in the first place. Victim blaming is a huge stigma we as women (as well as trans women too I imagine) face on a daily basis. Especially those who speak out about their trauma. The patriarchy shifts blame onto the victim, implying that a woman’s body is inherently sinful and something to be ashamed of. That having an act of violence committed against you is somehow your own fault.

Ovid’s depiction of a vestial virgin, devoutly spiritual in nature, falling from grace by having her innocence shredded from her by a man in a position of power... is very tragic. It highlights the brutality. Where it gets tricky... is with Athena’s punishment. Since she cannot punish Poseidon for his misdeeds, Athena punishes Medusa instead. Feminists have interpreted this action in two ways:

1. Athena justifies her punishment of Medusa because the act occurred in Athena’s temple. Enraged at having her temple defiled, and unable to hold the rapist accountable, she victim blames Medusa instead.

2. Others argue that as Medusa was Athena’s most devoted priestess, Athena knew Medusa was pure of heart and having her innocence taken from her in such a violent way was appalling. So Athena cursed Medusa as a way to protect her from a man ever harming her again, by giving Medusa the power to turn anyone who looked at her into stone.

I am more inclined to believe the first one. Sad as it is, anthropology tells us that women have been perpetuating violence against one another for centuries. Much as it pains me to admit, women are capable of atrocities towards each other, especially when jealousy rears it’s ugly head. Athena May have been jealous that people were coming to her temple to see Medusa performing the rites and rituals—not for worship of Athena herself. Or perhaps she overlooked this fact, knowing Medusa can’t help the way she is, and that her intentions of worship were pure.

Yet statistics show that many barbaric practices, including (but not limited to) female genital mutilation—are perpetuated not by men, but actually by women. For those who are unfamiliar, female genital mutilation is when a woman’s clitorus is cut off, removing sexual pleasure from the act. This is usually done for religious reasons, and though it is an archaic practice, women still force it upon their own daughters to this day—because it was done to them.

This idea that women need to force their own sufferings onto others... I’ve seen it time and time again among older women. My theory is that the psychological reason for this, is that it is an unconscious way to take back power, when they were powerless and it was done to them.

I was reflecting on this idea the other day...when my friend and I came up with the Medusa concept, and wanting to explore the deeper themes behind the mythology. The old idea that a woman’s sexuality is by nature unholy and degrading. That a woman historically was not free to explore this part of herself without punishment, or indeed even allowed to keep her virginity by choice—without subjugation to a man’s will. As women our choices have never been easy, but the other side of Medusa’s story says a lot about how little choice we had, how much things have changed (or not), and how far we still have to go.

62 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jerome Backstory

Circe ranks as one of the greatest witches of mythology. A beautiful enchantress . Circe, in Greek legend, a sorceress, the daughter of Helios, the sun god, and of the ocean nymph Perse. She was able by means of drugs and incantations to change humans into wolves, lions, and swine. The Greek hero Odysseus visited her island, Aeaea, with his companions, whom she changed into swine.

The daughter of Helios and Perse, Circe was a powerful enchantress versatile in the arts of herbs and potions and capable of turning human beings into animals. She did just that to Odysseus’ sailors when they reached her dwelling place, the secluded island of Aeaea. Odysseus, however, managed to trick her with the help of Hermes and, instead of becoming an animal, he became her lover for a year. The couple had three children, one of whom, Telegonus, eventually killed Odysseus.

Family

Circe was the daughter of Perse, one of the Oceanids, and Helios, the Titan sun god. As such, she was part of a family of formidable sorceresses. Pasiphae, who supposedly charmed both Minos and Procris, was her sister, and the even more notorious enchantress Medea was her niece, since she was the daughter of Circe’s brother Aeetes, the guardian of the Golden Fleece. Circe had another brother, Perses, who was slain by Medea after he had deposed her father Aeetes from the throne of Colchis.

Reaching Circe’s Island

Disheartened and dispirited from their horrendous encounter with the man-eating Laestrygonians – after which they had been left with only one out of their twelve ships – Odysseus and his remaining men land on Aeaea, Circe’s island.

At first glance, it seems to them like a desolate island, since the only visible sign of life is a column of smoke rising from somewhere deep in the woods. Naturally, Odysseus sends his men to investigate, putting his brother-in-law Eurylochus in charge of the scouting party.

The Transformation of Odysseus’ Men

After some time, the men reach Circe’s house and are surprised to find many fearsome beasts – mostly lions and wolves – slouching around and acting as domesticated as the tamest pets imaginable. From the inside, they hear a woman’s voice: it’s Circe singing melodiously.

Eurylochus suspects danger, so he chooses to stay outside as Circe comes out of her house and welcomes the rest of the scouting party indoors. Odysseus’ men are treated with some fine-flavored wine they gulp down in a second with the utmost pleasure. However, once they do that, Circe makes a quick move with her wand and, suddenly, all of Odysseus’ men are transformed into pigs. They still have their human brains, so they start grunting and weeping as Circe puts them into her pigsty.

Odysseus Tricks Circe

Eurylochus runs back to Odysseus and tells him the whole story and Odysseus decides to confront Circe. Fortunately, on his way to Circe’s house, he is met by Hermes, who gives him a magical black-rooted white-flowered plant called moly which, the divine messenger says, will make Odysseus immune to Circe’s spells.

As indicated by Hermes, Circe’s wine has no effect on the cunning Greek hero and so, after the enchantress pulls out her wand, Odysseus responds by pulling out his sword. He makes Circe swear that she won’t hurt him and forces her to restore the original form of all his sailors. Circe does precisely that and, furthermore, taken aback by his bravery, offers Odysseus her sincere love and unconditional devotion.

Odysseus accepts them, and, as a result, his men stay in Aeaea for almost a year, after which Odysseus becomes restless to go back to Ithaca and once again see his mortal wife, Penelope.

Odysseus’ and Circe’s Offspring

If we are to believe Hesiod’s genealogies, however, we must deduce that Odysseus returned to Aeaea once or twice more after this, or at least that he stayed there for a little longer than a year. Since Circe – says Hesiod – bore him no less than three children: Agrius, Latinus, and Telegonus. The last and youngest one of the three ended up killing Odysseus by mistake using a poisoned spear given to him by his mother.

Circe in Other Myths

Circe plays a smaller part in few other myths: she purifies Jason and Medea from a murder, and she transforms PIcus and Scylla into a woodpecker and monster respectively.

Jason and Medea

Circe shows up in the second most famous Ancient Greek story of sea adventures, the voyage of the Argonauts. According to Apollonius, after Jason and Medea treacherously and brutally kill the Colchian prince Absyrtus, it is Circe who purifies them from the sin, though she also chases them away from her island once she learns the full gravity of their transgression.

Circe, a Vengeful Lover

Before falling for Odysseus, Circe felt an attraction to at least three other men, the first one a mortal, and the second two a god.

The mortal was Picus, who was too faithful to his wife Canens for his own sake: after fiercely rejecting Circe’s advances, Picus was turned into a woodpecker. Unable to fight through the unbearable sorrow, six days later, Canens threw herself into the river Tiber.

Another time, the sea-god Glaucus asked Circe for a potion which would make the beautiful nymph Scylla fall in love with him. Circe, however, loved Glaucus for herself, so, when he scorned her, she gave him a potion which turned Scylla into the hideous sailor-preying monster Odysseus and his crew had to evade soon after leaving Circe’s island. The third was the God Odin. Odin was known for taking more than one female. Though he loved his mate, Odin had an affair with Circe keeping her happy so nothing bad fell on him.

Who was Circe?

The daughter of Helios and Perse, Circe was a powerful enchantress versatile in the arts of herbs and potions and capable of turning human beings into animals. She did just that to Odysseus’ sailors when they reached her dwelling place, the secluded island of Aeaea.

Where did Circe live?

Circe's home was Aeaea.

Who were the parents of Circe?

The parent of Circe was Helios.

Who were brothers and sisters of Circe?

Circe had 3 siblings: Pasiphae, Aeetes and Perses.

How many children did Circe have?

Circe had 4 children: Agrius, Latinus, Telegonus and Jerome.

Father: Odin

Odin (/ˈoʊdɪn/;[1] from Old Norse: Óðinn, IPA: [ˈoːðinː]) is a widely revered god in Germanic mythology. Norse mythology, the source of most surviving information about him, associates Odin with wisdom, healing, death, royalty, the gallows, knowledge, war, battle, victory, sorcery, poetry, frenzy, and the runic alphabet, and projects him as the husband of the goddess Frigg. In wider Germanic mythology and paganism, the god was known in Old English and Old Saxon as Wōden, in Old Dutch as Wuodan, and in Old High German as Wuotan, all ultimately stemming from the Proto-Germanic theonym *Wōđanaz, meaning 'lord of frenzy', or 'leader of the possessed'.

Odin appears as a prominent god throughout the recorded history of Northern Europe, from the Roman occupation of regions of Germania (from c. 2 BCE) through movement of peoples during the Migration Period (4th to 6th centuries CE) and the Viking Age (8th to 11th centuries CE). In the modern period the rural folklore of Germanic Europe continued to acknowledge Odin. References to him appear in place names throughout regions historically inhabited by the ancient Germanic peoples, and the day of the week Wednesday bears his name in many Germanic languages, including in English.

In Old English texts, Odin holds a particular place as a euhemerized ancestral figure among royalty, and he is frequently referred to as a founding figure among various other Germanic peoples, such as the Langobards. Forms of his name appear frequently throughout the Germanic record, though narratives regarding Odin are mainly found in Old Norse works recorded in Iceland, primarily around the 13th century. These texts make up the bulk of modern understanding of Norse mythology.

Old Norse texts portray Odin as one-eyed and long-bearded, frequently wielding a spear named Gungnir and wearing a cloak and a broad hat. He is often accompanied by his animal companions and familiars—the wolves Geri and Freki and the ravens Huginn and Muninn, who bring him information from all over Midgard—and rides the flying, eight-legged steed Sleipnir across the sky and into the underworld. Odin is the son of Bestla and Borr and has two brothers, Vili and Vé. Odin is attested as having many sons, most famously the gods Thor (with Jörð) and Baldr (with Frigg), and is known by hundreds of names. In these texts he frequently seeks greater knowledge, at times in disguise (most famously by obtaining the Mead of Poetry), makes wagers with his wife Frigg over the outcome of exploits, and takes part both in the creation of the world by way of slaying the primordial being Ymir and in giving the gift of life to the first two humans Ask and Embla. Odin has a particular association with Yule, and he provides mankind with knowledge of both the runes and poetry, giving Odin aspects of the culture hero.

Odin is a frequent subject of interest in Germanic studies, and scholars have advanced numerous theories regarding his development. Some of these focus on Odin's particular relation to other figures; for example, the fact that Freyja's husband Óðr appears to be something of an etymological doublet of the god, whereas Odin's wife Frigg is in many ways similar to Freyja, and that Odin has a particular relation to the figure of Loki. Other approaches focus on Odin's place in the historical record, a frequent question being whether the figure of Odin derives from Proto-Indo-European mythology, or whether he developed later in Germanic society. In the modern period the figure of Odin has inspired numerous works of poetry, music, and other cultural expressions. He is venerated in most forms of the new religious movement Heathenry, together with other gods venerated by the ancient Germani Odin, also called Wodan, Woden, or Wotan, one of the principal gods in Norse mythology. His exact nature and role, however, are difficult to determine because of the complex picture of him given by the wealth of archaeological and literary sources. The Roman historian Tacitus stated that the Teutons worshiped Mercury; and because dies Mercurii (“Mercury’s day”) was identified with Wednesday (“Woden’s day”), there is little doubt that the god Woden (the earlier form of Odin) was meant. Though Woden was worshiped preeminently, there is not sufficient evidence of his cult to show whether it was practiced by all the Teutonic tribes or to enable conclusions to be drawn about the nature of the god. Later literary sources, however, indicate that at the end of the pre-Christian period Odin was the principal god in Scandinavia.

From earliest times Odin was a war god, and he appeared in heroic literature as the protector of heroes; fallen warriors joined him in Valhalla. The wolf and the raven were dedicated to him. His magical horse, Sleipnir, had eight legs, teeth inscribed with runes, and the ability to gallop through the air and over the sea. Odin was the great magician among the gods and was associated with runes. He was also the god of poets. In outward appearance he was a tall, old man, with flowing beard and only one eye (the other he gave in exchange for wisdom). He was usually depicted wearing a cloak and a wide-brimmed hat and carrying a spear.

JEROME

As everyone knows, what Circe wanted, Circe got. When she set her sights on The father of Gods, Odin nothing would stop her. Odin, the God seen a beautiful God who could help him win his battles with her potions. Little did he know she would trick him, and keep him at her island for months while the plan all along was to impregnate her with a son. One she would cherish above all. He would be a brother to Thor. Only his powers would be that of not onky strength, he was a sorcerer as well. Jerome is out going, the life of the party. He has many abilities and ones he is still finding he has. He isn't like Father, or his Mother and is actually a nice guy with a huge heart. Yiu fuck with what's his, or family and he will make you pay.

18 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Origins and Evolution of the Bull Cult in the Ancient Mediterranean

Gods came in all forms in the ancient Mediterranean. Many were anthropomorphic, or human formed, others manifested in animal form. The bull in particular was considered a divine animal throughout antiquity and was a symbol of the moon, fertility, rebirth, and even royal power. The earliest depictions in Paleolithic cave art and the enigmatic veneration of the bull in Anatolia would influence a variety of religious cults in antiquity. From bull jumping in Minoan Crete, to the worship of the Apis bull in Egypt, to the sacrificial portrayal in Roman Mithraism, the bull was an integral part of many diverse and important religious traditions.

Evidence of bull worship has been found in areas as varied as Europe, Africa and India. The bull was the subject of cult veneration beginning 15,000 years ago in the late Upper Paleolithic era. One of the greatest representations of the bull from the Upper Paleolithic is the cave painting at Altamira in northern Spain. The ceiling of the cave is covered with impressive paintings depicting a herd of extinct bison.

Even though no evidence has been found indicating rituals centered on the bull took place at Altamira, it is interesting to note that initiation ceremonies from some later mystery religions in Asia Minor and Greece took place in caves. It is possible bull worship, which began with these cave paintings and evolved over thousands of years, influenced the roots of religious ritual to take place in caves or darkened temples.

In the Ancient Near East the earliest evidence of a bull cult was found at Çatal Hüyük in Anatolia around 7000 BCE. Bull paintings are featured on the northern walls of shrines which are like simulations of caves. There are even early representations of bull-games, specifically bull-leaping. The paintings depicts young acrobats jumping over the backs of bulls. Besides paintings, the shrines also include three-dimensional model bull heads made from plaster. Some bulls are depicted being born of the Goddess indicating a connection between bull and Mother Goddess worship. Actual bull skulls and horns were used to decorate the shrines as well.

The imagery of the Goddess and the bull, as well as the vulture show the religious beliefs of the inhabitants of Çatal Hüyük were focused on death and rebirth. Paintings of huge vultures indicate the practice of excarnation, where bodies were left for scavenging birds to pick clean. The first stamp seals, which may have been used for body and textile decoration, were found at Çatal Hüyük. Seals bearing the image of the bull were especially common. Migrating people and traders from Çatal Hüyük may have brought their religious and ritualistic practices involving the bull to other areas over the next several thousand years.

In Mesopotamia, the bull was to become a symbol of divinity rather than just an object of cult veneration. For the early Sumerians the bull symbolized divinity and power. Their chief gods Enlil and Enki would be honored as the “Great Bull” in song and ritual, and bulls would occasionally be represented on stamp seals with the gods. Images of bull sacrifice has also been found engraved on Sumerian seals. The scenes depicting a bull being stabbed in the throat could be the first evidence of bull sacrificial rites in history. Representations of human-headed bulls as well as bull-headed humans have also been found. These hybrid representations may symbolize the dominance of man over wild animals or the power of intelligence over man’s animal instincts.

In the Sumerian Epic of Gilgamesh the bull is represented as Gugalanna, the husband of Ereshkigal the Goddess of the Underworld. He is also called the “Bull of Heaven” and is sent by Anu to kill Gilgamesh and his friend Enkidu after Gilgamesh refuses to marry the goddess Inanna. Gugalanna is represented as an actual bull in the lines “with his first snort cracks opened in the earth and a hundred young men fell down to death”. There is even a bull-games aspect in the passage; “Enkidu dodged aside and leapt on the Bull and seized it by the horns”. Gilgamesh then succeeds in slaying the bull by thrusting his sword in its neck. The Bull of Heaven was not killed in the sacrificial manner by slashing the jugular which may be symbolic of the killing of the Mother goddess, in the form of Innana. This could indicate the rejection of the connection with Goddess worship as found in Çatal Hüyük thousands of years before.

After this symbolic break with Mother Goddess worship, the bull evolved into a symbol of spring and regeneration. Many cults in the future would use the bull as the principal ritual sacrifice, especially those related to the sun, like Roman Mithraism. In later Mesopotamian cultures the bull took on additional symbolic meanings. The bull and lion would frequently be depicted together as winged creatures symbolizing royal power. For the Babylonians the bull’s horns signified the crescent moon.

One area where elements of Goddess and bull worship may have continued is Minoan Crete in the second millennium BCE. There is evidence that Crete was first inhabited by migrant peoples from Anatolia and possibly people from Çatal Hüyük. Walter Burkert in Greek Religion states “the finds from the Neolithic town of Çatal Hüyük now make it almost impossible to doubt that the horned symbol which Evans called ‘horns of consecration’ does indeed derive from real bull horns”. Arthur Evans discovered and restored the ‘Palace of Minos’ at Knossos on Crete. The ‘horns of consecration’ are large bull horns on the walls of Knossos that have to come to symbolize the bull-games Cretan culture is famous for. The ‘palatial buildings’ discovered by Evans may actually be religious temples rather than buildings of government administration or a king’s palace. Cretan religious practices may have its roots in the Goddess cult from Anatolia as the evidence suggests the establishment was predominantly female.

Besides the earliest depiction of bull-games at Çatal Hüyük, bull-leaping paintings have been found in Egypt at Tell el-Daba’a, the ancient city of Avaris. The culture synonymous with bull-games is undeniably Crete in the second millennium BCE. The earliest representation of bull-leaping on Crete is from a pottery figure dated to circa 2000 BCE which depicts small humans holding the bull’s horns. The wall decorations at Knossos show human figures, some women dressed as men, gracefully jumping and performing acrobatic feats over the backs of the bull. Other representations depict wrestling with the bull and images of unfortunate bull-leapers being thrown, trampled or gored by the bull’s horns.

Even though the bull was clearly important to Cretan culture, there is no evidence it was worshipped as a god, like the Egyptian Apis bull, and may have been ritually sacrificed at the end of the bull-games. There is a sarcophagus at Aghia Triada on Crete which may depict a bull sacrifice. On one side of the sarcophagus the bull is shown lying on a table with its throat slashed while the blood is collected in a vase. The other side of the sarcophagus shows a woman pouring what is possibly the bull’s blood into another vase for an offering. This entire scene may show a ritual where the bull’s blood was used as a symbol of rebirth for the deceased.

In Greece some aspects of the bull-cult connected to Crete continued. The mythological stories of Theseus and the Minotaur and Zeus and Europa had roots in Cretan culture. In the myth of Theseus and the Minotaur, the Athenians were required to periodically send young men and women as an offering to King Minos of Knossos where they would be sacrificed to the Minotaur in the Labyrinth. Theseus travels to Knossos on Crete and slays the Minotaur freeing the Athenians. In the story of Europa, Zeus arrives in Crete in the form of a beautiful white bull, then transforms into his human form and fathers three sons on Europa, one of which was King Minos.

The bull-cult rituals in Greek rural areas were sacrificial and were often held in caves. The bull would be identified with a god, usually Dionysos, Zeus or Poseidon, and the sacrifice of the animal would symbolize the god’s death and rebirth. Dionysos was also sometimes represented in man-bull form with horns and was honored at fertility festivals. A bull sacrifice was even included as part of the Eleusinian mystery cult of Demeter and Persephone.

In Egypt the bull-cult included a wide variety of aspects including sacrificial rites, identification with the gods, and the symbol of the king and royal power. It is the most important center for bull worship in antiquity. The earliest evidence of the bull-cult in Egypt is from the pre-Dynastic period and is found in a tomb at Hierakonopolis. Tomb 100, unfortunately destroyed and only preserved in drawings, consists of a grave where a bull, cow, and calf are buried together, covered with a makeshift canopy. Wild bulls are painted on the tomb walls as well as scenes of hunting and warfare.

When Narmer unified Upper and Lower Egypt the bull became a personification of the king and a symbol of royal power. The “Bull Palette” is associated with Narmer and each side depicts the king as a bull trampling or goring his enemies. The bull was also used as a funerary decoration during the First Dynasty. Tombs 3504 and 3507 discovered at Saqqara featured bulls’ heads surrounding the perimeter of the tomb. Tomb 3504 included about 300 of these heads. At each site the bull heads were made from clay but were finished with real bull horns, similar to the plaster heads found at Çatal Hüyük. Also at Saqqara, a genuine bull skull was found buried under an altar in the funerary complex of the Step Pyramid.

The cult of the Apis bull also originated at Saqqara in either the First or Second Dynasty. The Apis was worshipped as the embodiment of the powerful god Ptah. The Greek historian, Herodotus, describes the Apis in the Histories, “Now this Apis, or Epaphus, is the calf of a cow which is never afterwards able to bear young. The Egyptians say that fire comes down from heaven upon the cow, which thereupon conceives Apis. The calf which is so called has the following marks: He is black, with a square spot of white upon his forehead, and on his back the figure of an eagle; the hairs in his tail are double, and there is a beetle upon his tongue”. When an Apis Bull died the priests would find a young bull with these markings and it would become the new Apis. The new Apis would then be brought to Memphis where he would be kept in luxury by the priesthood. After their death, the Apis bulls were mummified and buried in the Serapeum at Saqqara.

Besides the Apis, there were two other bull-cults in Egypt. The Buchis bull was sacred to the god Montu and was worshipped at Thebes. There is evidence these sacred bulls were buried in the Bucheum as late as 340 CE. The Mnevis bull, sacred to Re, was worshipped at Heliopolis as the living bull. Even though the bull was clearly fundamental to many Egyptian religious practices, there is no depiction of a bull-headed god like the many other animal headed gods which are part of their pantheon.

In Rome, the bull was a sacrificial victim, but also a symbol of regeneration. Roman Mithraism may have had its roots in Persia and became very popular with Roman soldiers in the first century AD. It was a mystery cult centered on the bull-slaying god Mithras where believers participated in initiation rituals held in a mithraeum, a shrine reminiscent of a cave. The cave was an important aspect in Mithraism because the god had slayed the bull in a cave.Porphyry, a Neoplatonist philosopher, said of the roots of Mithraic rites in On the Cave of the Nymphs, “not only have they made the cave a symbol of the perceptible cosmos, but they also have used the cave as a symbol of all the unseen powers, since caves are dark, and that which is the essence of the powers is invisible.”

Very little is known of the cult’s actual rites. There may have been a re-enactment of Mithras slaying the bull, as a bull hide would cover the table where the initiates shared a feast. The act of slaying the bull, tauroctony, was depicted on reliefs found in every mithraeum and symbolized transformation. Manfred Clauss in The Roman Cult of Mithras The God and His Mysteries graphically describes the act on a relief; “beneath the arching roof of the cave, Mithras, with an easy grace and imbued with youthful vigour, forces the mighty beast to the ground, kneeling in triumph with his left knee on the animal’s back or flank, and constraining its rump with his almost fully extended right leg. Grasping the animal’s nostrils with his left hand and so pulling its head upwards to reduce its strength the god plunges the dagger into its neck with his right hand. The animal’s throat rattles, the tail jerks up: it dies.” In Mithraism, the bull represents the moon, a symbol of death and rebirth. Mithras represents Sol Invictus, the invincible sun, whose sacrifice of the bull brings light and creation.

The bull-cult was clearly an integral part of many religious practices in the ancient Mediterranean. The question is why the bull, above all other animals, remained such a powerful symbol for over 15,000 years. Michael Rice in The Power of the Bull says the psychologist Carl Jung “tended to see the bull as a metaphor for brute nature, operating at a lower state of consciousness than that of fully realized humanity. He considered bull sacrifices as devices for affecting the catharsis of the ancients’ sense of their animal nature”.

Of all the aspects of the bull-cult, the sacrifice was the central event. Even in Egypt, where the Apis bull was treated like a god, sacrifice was common. The killing of the bull, a highly valued animal, was done with the expectation the gods would be pleased and in exchange would bring them prosperity. Spilling the blood of this supreme animal was a sacred act that would bring rebirth or salvation to the participants of the ritual.

The origins of the bull-cult began in the darkened caves of Paleolithic Europe. Cave paintings of the divine bull, like those in Altamira, would continue in a similar form in the shrines of Çatal Hüyük. Depictions of bull-games and bull-leaping first found at Çatal Hüyük would be discovered in Egypt, and become synonymous with the Minoan culture of Crete. The bull would gain prominence in the literary traditions of Mesopotamia in The Epic of Gilgamesh and in Greek mythology through the stories of Theseus and the Minotaur and Zeus and Europa.

Beginning in Sumeria, the bull would be associated with the gods and this practice would continue in Egyptian and Greek culture. In Egyptian culture the bull would reach the pinnacle of its veneration. From the similarities of bull-influenced tomb decorations to the shrines at Çatal Hüyük, to the worship of the Apis bull as the god Ptah, Egypt was the most important center of the bull-cult in the ancient Mediterranean. Bull sacrifice was practiced throughout antiquity and its symbolism was central to Roman Mithraism. The divine bull was a symbol of fertility, the moon, and the gods, but above all a symbol of rebirth and salvation.

Written by Darci Clark

Further reading: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sacred_bull

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

Swan Lake