#Çatal hüyük

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

it never is tajikistan por lo que sea

#manifesting for the first asian country i visit to be türkiye#I NEED IT#i need to see çatal hüyük and gobekli tepe and cappadocia and lake van and ionia and hattussas and

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

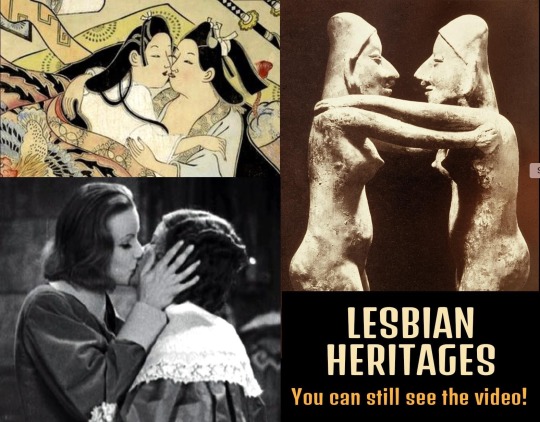

If you missed the Lesbian Heritages show, you can still see it stream on demand til April 15. Just register and Max Dashu will send you the link.

Regular $20: https://py.pl/1zNJJD

Supporter $25: https://py.pl/1H2wsh

Low-Income: $15: https://py.pl/wkOhd

Lesbian Heritages

International view of woman-loving women, from archaeological finds of paired and embracing women, up to recent history. Khotylevo, Çatal Hüyük, Mycenae, Nayarit, Etruria, Nok, and the Begram ivories. Lesbian love in Hellenistic art, Thai murals, Indian temple carvings, and Japanese erotic books. Some called us mati, zami, hwame, sakhiyani, bofe or sapatão. Lesbians as female rebels: the Amazons, Izumo no Okuni, Juana Asbaje, Louise Michel, Stormé DeLarverie. Women who passed as men in order to practice medicine and roam the world. Punishing the lesbian: in the Bible, Zend Avesta, Laws of Manu; and demonological fantasies. Lesbian musicians (Sotiria Bellou, Chavela Vargas, Ethyl Waters), artists (Edmonia Lewis, Romaine Brooks, Yan María Castro), writers (Emily Dickinson), and actors (Garbo!) Lesbian clubs and scenes in Paris, Berlin, and New York. Lesbian feminists, and Arab, South African, Australian lesbians. And more…

"I am a lesbian, I am reality; I insist on living in freedom: --Rebeldías Lesbicas, Peru

157 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

Witches, women, and animal care.

#radical feminism#divine female#mother nature#radfem#womenempowerment#women power#dogs of tumblr#dogs#cats#cats of tumblr#farming#homesteading#wolf#Youtube

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Agricultural fertility is a matter of vital concern to the peoples of the ancient world, who cannot take fertility for granted and believe that fertility is fragile. Ancient religions provide a way to participate in the creation of fertile abundance and to ensure its continuation. They address a human desire to do everything possible to make the earth fertile and to make the crops grow. In Mesopotamian thinking, labor is divinely ordained and, indeed, the purpose for which humans were created. The gods give humankind the tools of labor and instruct the people on their use. Actual work, however, is only one sphere of activity. The ancient pagan religions also provided a cult of fertility in which people sang, danced, and performed other rituals in order to experience and aid the perpetuation of nature.

It was not ignorance that impelled people to perform these rituals, for they were practiced long after the neolithic revolution, long after the ancients learned that if you put a seed in the ground it will grow, long after people domesticated plants and animals to ensure their food supply. But the ancient farmers were also very aware that sometimes you could put a seed in the ground and it wouldn't grow. The ground might be too saline, or the birds might eat the seed, or locusts might devour the growing plants, the weather conditions might not be right, the earth might have become contaminated. There are so many reasons that a seed might not grow that it is a miracle every time it really does so. Pagan religions celebrated this miracle by offering a ritual life through which one can participate in this miracle. Of course. the fertility ritual does not really "cause" fertility—if it could, rituals would not have to be repeated. But in performing these rituals, the celebrants acknowledge their dependence on fertility and their desire to participate in assuring the continuation of the natural cycle.

Pagan prayers and rituals reflect the idea that fertile abundance is the result of harmonious interaction among various powers in the cosmos. Cultic acts and liturgy may propitiate the various divine powers and facilitate their joining together. In Sumerian cult, this conjoining was achieved sexually in the ritual of the sacred marriage. In later periods, even when sacred marriage was no longer part of the official state cult, it clearly continued in sacred and popular literature. Was there ever a time in which fertility and vegetation were thought to come directly from the womb of the earth mother? This claim, very often assumed in modern recreations of paganism, can only be true (if at all) for the prehistoric period. There may be prehistoric evidence from Old Europe and possibly from Çatal Hüyük that the mother-goddess had this vital function and the all-powerful position that results from it. The historical evidence, from the writings of Sumer and Babylon, indicates that the conceptualization of fertility was much more complex than the simple idea of earth mother and her womb. There are certainly goddesses of vegetation, and the breast of the goddess Nisaba is sometimes considered the source of grain. But more common are the many indications that fertility required many gods, and that no one god was able to insure it. Agricultural abundance depended on an interaction of forces and their divine embodiments, upon the fertility of the earth and its fertilization by water, and upon the joining of the power of life with the exercise of agriculture. This conjoining of forces could be aided by sexual activities on the fertile bed, sexual intercourse into the body of the young nubile goddesses. Even when sexual union is not part of the ritual, this union of forces is the essential metaphysical idea.

-Tikva Frymer-Kensky, In the Wake of the Goddesses: Women, Culture, and the Biblical Transformation of Pagan Myth

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

"in what sense were [Çatal Hüyük's] men and women "urban"? ... They were not burdened by the anonymity and awesome sense of personal isolation that is the most characteristic trait of the modern urban dweller. In some sense, they were "protocitizens" of a highly articulated and richly textured community in which a high sense of collectivity, ... was integrated with the civic facts of politically defined rights and duties"

-Murray Bookchin

#anarchism#book is cities without urbanisation#murray bookchin#social ecology#urban planning#urbanism

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Beneath the Rising by Premee Mohamed

By: S. Qiouyi Lu

Issue: 24 February 2020

Nick Prasad has always been Joanna “Johnny” Chambers’s sidekick. Friends since a young age, Johnny has rocketed into an early and brilliant career as a child prodigy scientist, while Nick has lived a quiet, mundane life in which his biggest concerns are work and family. But the two of them still have a regular, teenage friendship, one filled with banter and misadventures. So when Johnny comes up with a new invention that could change the world, Nick doesn’t think much of it at first: after all, this is the seventeen-year-old girl who has already fitted the world with solar panels, created lifesaving medications, and perfected tools that assist millions of people’s lives—to name just a few of her accomplishments.

When strange things start to happen, Nick soon realizes that this invention isn’t like the others. An aurora borealis that shouldn’t be visible from their latitude heralds the coming of monstrous creatures, relentless in their pursuit of Johnny and her new invention. Bit by bit, the scale of what’s happening comes together: there are other realms beyond ours where terrible evil lurks and waits for its opportunity to trigger the next apocalypse. Those beings, “The Ancient Ones,” are responsible for the annihilation of civilizations ranging from Carthage to Cahuachi to Çatal Hüyük to Atlantis. And now, they’re after Johnny’s invention and the power it can unleash to destroy the world again.

But that’s not all. Suspicious of how much Johnny knows about the origin of these monsters, Nick pries the truth out of her and discovers that she’s made a covenant with the Ancient Ones. One of their terrifying pursuers, Drozanoth, is here to uphold that covenant, and will do anything to make Johnny hand over the invention responsible for calling the Ancient Ones back to Earth. Now, only she has any idea how to close the gates that are opening between realms. Determined to help stop the apocalypse, Nick embarks on a wild scavenger hunt with Johnny across the Maghreb and the Middle East to gather the items they need to put an end to the invasion.

Beneath the Rising, Indo-Guyanese author Premee Mohamed’s debut novel, is a rollercoaster of an experience. Although Mohamed draws from cosmic horror tropes as classic as Lovecraft’s, she challenges the oppressive foundations on which Lovecraft built his career. The novel is set in an alternate history shortly after a failed terrorist attack on the World Trade Center on September 11, 2001. The impact of September 11 doesn’t go unnoticed: instead, it, and the period setting of the early 2000s, deeply inform the characters’ every movement through the world and the global context around them. Nick, who is Indo-Caribbean and often refers to himself as “brown,” details the various ways in which his racial and class background affect how he sees the world, and how the world sees him. Unlike Nick, Johnny, the wonder-kid know-it-all seemingly blessed with endless genius, is White and rich. Although the sexism she faces is made clear, her privilege on other axes is called out in a way that feels natural to the characters and important to the narrative.

Lovecraft’s work often relies on racism to fuel its narrative and to lend horror and dread to cosmic horror elements. Mohamed, on the other hand, lays out the intersecting foundations of that marginalization and shows how those systems of oppression are the all-too-mundane backdrop against which otherworldly cosmic horror can play out. On top of that, Mohamed brings a genuinely global scope to her doomsday narrative. It is not just the West that faces an imminent catastrophe in Beneath the Rising. Rather, most of the main events occur in the Maghreb and across the Middle East. The rise and fall of civilizations across a broad set of cultures at the hands of the Ancient Ones feels like a smooth integration of all parts of the world, creating a truly global and historically linear scope of events that adds urgency to the narrative.

When it comes to the technical details of craft, Beneath the Rising shows Mohamed’s masterful command of description, pace, and emotion that renders powerful characters and settings. The prose is lean and deliberate, a short story writer’s novel. Mohamed, who also has several short fiction publications to her name, makes sure that every sentence, every paragraph, every simile serves multiple purposes. A sentence can reveal period- and character-appropriate details while also being embedded in an unusual, yet apt, metaphor that vividly describes and furthers the events of the story:

[Johnny] was trembling so hard she was almost flickering, like a poorly-tracked VHS tape. […] This [fear] felt more like something from outside of me, like secondhand smoke, greasily invisible, sinking into my pores, blown from someone unseen. (pp. 56–58)

Mohamed’s command of the rhythm of a sentence shows through in her control over the pace of the story as well. When Nick and Johnny have room to breathe, the prose is denser and slower as it lingers on fuller descriptions.

In the moment of relative safety I craned my head to try to take it all in, wishing I had sunglasses or a hat—it was so bright it just seemed like a spangled kaleidoscope of car windows, men in suits, tiny booths hawking electronics, sunglasses, clothing, CDs, food, tiles, everyone gabbling around me in languages I didn’t know, plus blessedly recognizable if not actually comprehensible French and English. People bumped and buffeted me apparently without even noticing. I had been picturing … I don’t even know what. Some mud-brick city from Raiders of the Lost Ark? Flowing white robes? Tintin books, for absolute sure. (p. 144)

But when Nick and Johnny are on the run, Mohamed’s prose goes into fight-or-flight mode, highlighting only the barest of actions, reactions, and sensory details. The reader barrels along, breathless, with the characters.

I shut the closet door, hearing first a bang, and then—oh shit—the musical tinkle of falling glass from the living room. A multilegged shadow, all spikes and floppy appendages and translucent nodules, firmly struck the hallway wall, like an ink stamp. I cast about, left, right, left, right. Kids. Bedroom. Two quick steps: empty. (p. 103)

At the same time, Beneath the Rising isn’t just an action-adventure chase after a string of McGuffins against a backdrop of tentacles, shadows, uncanny eldritch pawns, and imminent apocalypse. It’s also a slow tale about a different kind of unrequited love between two teenagers who were forced to grow up too early, and who have never had the space to address their lingering PTSD after surviving a shooting during a hostage crisis. Woven between the multidimensional chaos of the Ancient Ones’ return is a poignant, melancholy tale of what growing out of childhood ideals means and feels like. As Nick confronts the codependent nature of his love for Johnny, who turns out not to be the person he thought she was, he shores up memories and emotions that illustrate the processing he’s doing internally while also showing his growth as a character. The vindication of his fury and betrayal feels both earned and deserved.

The biggest strength of the novel, however, comes from the shocking reveal toward the end of the book that explains the true nature of Nick’s “friendship” with Johnny, and why he was even dragged along on such a dangerous journey he had no hand in creating. I’ll be including spoilers from here on in order to fully discuss the impact of the ending.

Instead of being a magnanimous scientist who simply wants to help the world, Johnny practices “altruism” as a reflection of her own need for power and worth. She may be doing good with her work, but that doesn’t mean that she can’t channel great evil and also be a villainous mad scientist. Her prodigal power and inhuman brilliance stem from a covenant she struck with the Ancient Ones. In exchange for time off of her life, Johnny can speed up her mind, like a supercomputer’s processing power getting a boost, to do what she does. But with that covenant came another clause that Johnny only reveals to Nick when she can no longer hide it. Afraid that her unbelievable talent would alienate her from the rest of the world, leaving her alone forever, Johnny bargained for Nick to be forever by her side as a companion. Nick’s true relationship to Johnny is as a slave.

This Faustian covenant, however, didn’t have to take place. Johnny admits that, if she’d refused the covenant, she would have still lived a comfortable, successful life, and would have still been a great scientist. But, lured in by power and the opportunity to influence the world, saving millions of lives in the process, Johnny agreed to a deal with the Ancient Ones. She justifies her actions with all the good she’s done—but Beneath the Rising is, at its heart, a novel about the true cost of power, and whether the ends can justify appalling means. After all, the Ancient Ones would never have been attracted to the world if Johnny had refused the covenant in the first place. The millions of lives potentially lost in a global apocalypse don’t factor into Johnny’s calculations of how much good she does and her positive impact on the world.

Therein lies the extended metaphor that forms the secret crux of Mohamed’s narrative: Johnny’s covenant, and Nick’s role as her “companion,” are tools to critique the legacy of colonialism; in particular, slavery. In a key character turning point, Nick reminds Johnny that his family, of Indian descent and from Guyana, descends from indentured servants who were exploited for the sake of the British Empire. Nick takes deep offense at the way Johnny doles out money, as if to buy people and solutions to her problems. Johnny’s race is actually the most insignificant reflection of her position as a symbol for colonization and empire. It is her utilitarian attitude toward people and her perceived self-importance as a representative of “the greater good” that motivate the true horrors that Johnny commits. Loyalty can always be bought. Nick’s loss of agency, the loss of his potential livelihood, and the psychic toll of not being a genuinely free individual, never enter into Johnny’s mind. Nick isn’t truly a friend, an equal, or even a person to her. He is a sidekick, a person to be uprooted from place to place so that Johnny can always have someone to carry her when she is weak, provide strength when she has none, and sacrifice his life if she needs him to. Nick is merely a resource she can exploit as an extension of herself. How many families, societies, and whole cultures have similarly been torn apart to support the advancement of Western civilization?

No matter how euphemistically slavery is named, whether as “indentured servitude,” “incarceration,” or “debt bondage,” it is ultimately the real covenant that robs people of their time and life force. The lasting socioeconomic impact of slavery, too, oozes through Beneath the Rising as the gulf in wealth between Nick and Johnny, as well as the gulf in opportunity and attitudes toward self-worth between them. No eldritch covenant needs to be made for oppressors to keep subjugating the oppressed. Through Johnny, the whole empire of colonization is laid bare and exposed: for all the “advancement” purportedly created by colonizers, for all the status colonizers lay claim to, millions of people whom colonizers considered as second-class were sacrificed. When Johnny sets out to “save the world,” what she is truly saving is the status quo of her own world of privilege. Nick’s world, the world of the subjugated and oppressed, has long since been lost.

On a micro scale, Beneath the Rising is the best inversion of the sidekick trope I’ve ever seen. The effect of a reckless superhuman crashing through the world are called out early: who will clean up? Who will pay for property damage? Who will handle witness protection? Insurance? Jobs? How will people recover from the trauma of such a disruptive event? Then, when the true nature of Nick’s slavery is revealed, we see the rare story of a sidekick walking away—of codependency not being romanticized, but called out for the real destruction it can cause. Nick’s anger and betrayal are validated narratively as he sets boundaries at last and recovers from Johnny’s exploitation. The scale of Johnny’s betrayal and the evilness of her act are never downplayed, even as Johnny herself, like many benefitting from the legacy of colonization, remains clueless of her impact, even going so far as to still believe that she is doing good, and that all the devastation behind her can be a footnote to her altruism.

Beneath the Rising is a near-flawless debut novel. While it works well as a standalone, the story and worldbuilding leave room for sequels as well. Multilayered and richly rendered, Beneath the Rising is a darkly humorous romp through unspeakable cosmic horrors that also paints a portrait of two hurt teenagers grappling with their place in the world and their relationship with each other, all while navigating complex inner worlds impacted by the legacies of colonization, slavery, racism, and sexism. Like a doomsday device, Beneath the Rising is compact, powerful, and devastating as it hurls the reader through a brilliantly crafted narrative. Prepare for an epic journey, and don’t forget to bring a barf bag for the turbulent ride.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Древний город Чатал-Хююк Древний город Чатал-Хююк (Çatal Hüyük) Открытое в середине пятидесятых годов минувшего столетия доисторическое поселение Чатал-Хююк, по мнению многих исследователей древнего мира, является одним из наиболее древних поселений человека на территории Евразии, так как по полученным результатам радиоуглеродного анализа самые древние наход��и из этого исторического артефакта датируются седьмым и шестым тысячелетием до нашей эры. Путешествие сквозь … Сообщение Древний город Чатал-Хююк появились сначала на Информационно туристический портал.

0 notes

Photo

The Origins and Evolution of the Bull Cult in the Ancient Mediterranean

Gods came in all forms in the ancient Mediterranean. Many were anthropomorphic, or human formed, others manifested in animal form. The bull in particular was considered a divine animal throughout antiquity and was a symbol of the moon, fertility, rebirth, and even royal power. The earliest depictions in Paleolithic cave art and the enigmatic veneration of the bull in Anatolia would influence a variety of religious cults in antiquity. From bull jumping in Minoan Crete, to the worship of the Apis bull in Egypt, to the sacrificial portrayal in Roman Mithraism, the bull was an integral part of many diverse and important religious traditions.

Evidence of bull worship has been found in areas as varied as Europe, Africa and India. The bull was the subject of cult veneration beginning 15,000 years ago in the late Upper Paleolithic era. One of the greatest representations of the bull from the Upper Paleolithic is the cave painting at Altamira in northern Spain. The ceiling of the cave is covered with impressive paintings depicting a herd of extinct bison.

Even though no evidence has been found indicating rituals centered on the bull took place at Altamira, it is interesting to note that initiation ceremonies from some later mystery religions in Asia Minor and Greece took place in caves. It is possible bull worship, which began with these cave paintings and evolved over thousands of years, influenced the roots of religious ritual to take place in caves or darkened temples.

In the Ancient Near East the earliest evidence of a bull cult was found at Çatal Hüyük in Anatolia around 7000 BCE. Bull paintings are featured on the northern walls of shrines which are like simulations of caves. There are even early representations of bull-games, specifically bull-leaping. The paintings depicts young acrobats jumping over the backs of bulls. Besides paintings, the shrines also include three-dimensional model bull heads made from plaster. Some bulls are depicted being born of the Goddess indicating a connection between bull and Mother Goddess worship. Actual bull skulls and horns were used to decorate the shrines as well.

The imagery of the Goddess and the bull, as well as the vulture show the religious beliefs of the inhabitants of Çatal Hüyük were focused on death and rebirth. Paintings of huge vultures indicate the practice of excarnation, where bodies were left for scavenging birds to pick clean. The first stamp seals, which may have been used for body and textile decoration, were found at Çatal Hüyük. Seals bearing the image of the bull were especially common. Migrating people and traders from Çatal Hüyük may have brought their religious and ritualistic practices involving the bull to other areas over the next several thousand years.

In Mesopotamia, the bull was to become a symbol of divinity rather than just an object of cult veneration. For the early Sumerians the bull symbolized divinity and power. Their chief gods Enlil and Enki would be honored as the “Great Bull” in song and ritual, and bulls would occasionally be represented on stamp seals with the gods. Images of bull sacrifice has also been found engraved on Sumerian seals. The scenes depicting a bull being stabbed in the throat could be the first evidence of bull sacrificial rites in history. Representations of human-headed bulls as well as bull-headed humans have also been found. These hybrid representations may symbolize the dominance of man over wild animals or the power of intelligence over man’s animal instincts.

In the Sumerian Epic of Gilgamesh the bull is represented as Gugalanna, the husband of Ereshkigal the Goddess of the Underworld. He is also called the “Bull of Heaven” and is sent by Anu to kill Gilgamesh and his friend Enkidu after Gilgamesh refuses to marry the goddess Inanna. Gugalanna is represented as an actual bull in the lines “with his first snort cracks opened in the earth and a hundred young men fell down to death”. There is even a bull-games aspect in the passage; “Enkidu dodged aside and leapt on the Bull and seized it by the horns”. Gilgamesh then succeeds in slaying the bull by thrusting his sword in its neck. The Bull of Heaven was not killed in the sacrificial manner by slashing the jugular which may be symbolic of the killing of the Mother goddess, in the form of Innana. This could indicate the rejection of the connection with Goddess worship as found in Çatal Hüyük thousands of years before.

After this symbolic break with Mother Goddess worship, the bull evolved into a symbol of spring and regeneration. Many cults in the future would use the bull as the principal ritual sacrifice, especially those related to the sun, like Roman Mithraism. In later Mesopotamian cultures the bull took on additional symbolic meanings. The bull and lion would frequently be depicted together as winged creatures symbolizing royal power. For the Babylonians the bull’s horns signified the crescent moon.

One area where elements of Goddess and bull worship may have continued is Minoan Crete in the second millennium BCE. There is evidence that Crete was first inhabited by migrant peoples from Anatolia and possibly people from Çatal Hüyük. Walter Burkert in Greek Religion states “the finds from the Neolithic town of Çatal Hüyük now make it almost impossible to doubt that the horned symbol which Evans called ‘horns of consecration’ does indeed derive from real bull horns”. Arthur Evans discovered and restored the ‘Palace of Minos’ at Knossos on Crete. The ‘horns of consecration’ are large bull horns on the walls of Knossos that have to come to symbolize the bull-games Cretan culture is famous for. The ‘palatial buildings’ discovered by Evans may actually be religious temples rather than buildings of government administration or a king’s palace. Cretan religious practices may have its roots in the Goddess cult from Anatolia as the evidence suggests the establishment was predominantly female.

Besides the earliest depiction of bull-games at Çatal Hüyük, bull-leaping paintings have been found in Egypt at Tell el-Daba’a, the ancient city of Avaris. The culture synonymous with bull-games is undeniably Crete in the second millennium BCE. The earliest representation of bull-leaping on Crete is from a pottery figure dated to circa 2000 BCE which depicts small humans holding the bull’s horns. The wall decorations at Knossos show human figures, some women dressed as men, gracefully jumping and performing acrobatic feats over the backs of the bull. Other representations depict wrestling with the bull and images of unfortunate bull-leapers being thrown, trampled or gored by the bull’s horns.

Even though the bull was clearly important to Cretan culture, there is no evidence it was worshipped as a god, like the Egyptian Apis bull, and may have been ritually sacrificed at the end of the bull-games. There is a sarcophagus at Aghia Triada on Crete which may depict a bull sacrifice. On one side of the sarcophagus the bull is shown lying on a table with its throat slashed while the blood is collected in a vase. The other side of the sarcophagus shows a woman pouring what is possibly the bull’s blood into another vase for an offering. This entire scene may show a ritual where the bull’s blood was used as a symbol of rebirth for the deceased.

In Greece some aspects of the bull-cult connected to Crete continued. The mythological stories of Theseus and the Minotaur and Zeus and Europa had roots in Cretan culture. In the myth of Theseus and the Minotaur, the Athenians were required to periodically send young men and women as an offering to King Minos of Knossos where they would be sacrificed to the Minotaur in the Labyrinth. Theseus travels to Knossos on Crete and slays the Minotaur freeing the Athenians. In the story of Europa, Zeus arrives in Crete in the form of a beautiful white bull, then transforms into his human form and fathers three sons on Europa, one of which was King Minos.

The bull-cult rituals in Greek rural areas were sacrificial and were often held in caves. The bull would be identified with a god, usually Dionysos, Zeus or Poseidon, and the sacrifice of the animal would symbolize the god’s death and rebirth. Dionysos was also sometimes represented in man-bull form with horns and was honored at fertility festivals. A bull sacrifice was even included as part of the Eleusinian mystery cult of Demeter and Persephone.

In Egypt the bull-cult included a wide variety of aspects including sacrificial rites, identification with the gods, and the symbol of the king and royal power. It is the most important center for bull worship in antiquity. The earliest evidence of the bull-cult in Egypt is from the pre-Dynastic period and is found in a tomb at Hierakonopolis. Tomb 100, unfortunately destroyed and only preserved in drawings, consists of a grave where a bull, cow, and calf are buried together, covered with a makeshift canopy. Wild bulls are painted on the tomb walls as well as scenes of hunting and warfare.

When Narmer unified Upper and Lower Egypt the bull became a personification of the king and a symbol of royal power. The “Bull Palette” is associated with Narmer and each side depicts the king as a bull trampling or goring his enemies. The bull was also used as a funerary decoration during the First Dynasty. Tombs 3504 and 3507 discovered at Saqqara featured bulls’ heads surrounding the perimeter of the tomb. Tomb 3504 included about 300 of these heads. At each site the bull heads were made from clay but were finished with real bull horns, similar to the plaster heads found at Çatal Hüyük. Also at Saqqara, a genuine bull skull was found buried under an altar in the funerary complex of the Step Pyramid.

The cult of the Apis bull also originated at Saqqara in either the First or Second Dynasty. The Apis was worshipped as the embodiment of the powerful god Ptah. The Greek historian, Herodotus, describes the Apis in the Histories, “Now this Apis, or Epaphus, is the calf of a cow which is never afterwards able to bear young. The Egyptians say that fire comes down from heaven upon the cow, which thereupon conceives Apis. The calf which is so called has the following marks: He is black, with a square spot of white upon his forehead, and on his back the figure of an eagle; the hairs in his tail are double, and there is a beetle upon his tongue”. When an Apis Bull died the priests would find a young bull with these markings and it would become the new Apis. The new Apis would then be brought to Memphis where he would be kept in luxury by the priesthood. After their death, the Apis bulls were mummified and buried in the Serapeum at Saqqara.

Besides the Apis, there were two other bull-cults in Egypt. The Buchis bull was sacred to the god Montu and was worshipped at Thebes. There is evidence these sacred bulls were buried in the Bucheum as late as 340 CE. The Mnevis bull, sacred to Re, was worshipped at Heliopolis as the living bull. Even though the bull was clearly fundamental to many Egyptian religious practices, there is no depiction of a bull-headed god like the many other animal headed gods which are part of their pantheon.

In Rome, the bull was a sacrificial victim, but also a symbol of regeneration. Roman Mithraism may have had its roots in Persia and became very popular with Roman soldiers in the first century AD. It was a mystery cult centered on the bull-slaying god Mithras where believers participated in initiation rituals held in a mithraeum, a shrine reminiscent of a cave. The cave was an important aspect in Mithraism because the god had slayed the bull in a cave.Porphyry, a Neoplatonist philosopher, said of the roots of Mithraic rites in On the Cave of the Nymphs, “not only have they made the cave a symbol of the perceptible cosmos, but they also have used the cave as a symbol of all the unseen powers, since caves are dark, and that which is the essence of the powers is invisible.”

Very little is known of the cult’s actual rites. There may have been a re-enactment of Mithras slaying the bull, as a bull hide would cover the table where the initiates shared a feast. The act of slaying the bull, tauroctony, was depicted on reliefs found in every mithraeum and symbolized transformation. Manfred Clauss in The Roman Cult of Mithras The God and His Mysteries graphically describes the act on a relief; “beneath the arching roof of the cave, Mithras, with an easy grace and imbued with youthful vigour, forces the mighty beast to the ground, kneeling in triumph with his left knee on the animal’s back or flank, and constraining its rump with his almost fully extended right leg. Grasping the animal’s nostrils with his left hand and so pulling its head upwards to reduce its strength the god plunges the dagger into its neck with his right hand. The animal’s throat rattles, the tail jerks up: it dies.” In Mithraism, the bull represents the moon, a symbol of death and rebirth. Mithras represents Sol Invictus, the invincible sun, whose sacrifice of the bull brings light and creation.

The bull-cult was clearly an integral part of many religious practices in the ancient Mediterranean. The question is why the bull, above all other animals, remained such a powerful symbol for over 15,000 years. Michael Rice in The Power of the Bull says the psychologist Carl Jung “tended to see the bull as a metaphor for brute nature, operating at a lower state of consciousness than that of fully realized humanity. He considered bull sacrifices as devices for affecting the catharsis of the ancients’ sense of their animal nature”.

Of all the aspects of the bull-cult, the sacrifice was the central event. Even in Egypt, where the Apis bull was treated like a god, sacrifice was common. The killing of the bull, a highly valued animal, was done with the expectation the gods would be pleased and in exchange would bring them prosperity. Spilling the blood of this supreme animal was a sacred act that would bring rebirth or salvation to the participants of the ritual.

The origins of the bull-cult began in the darkened caves of Paleolithic Europe. Cave paintings of the divine bull, like those in Altamira, would continue in a similar form in the shrines of Çatal Hüyük. Depictions of bull-games and bull-leaping first found at Çatal Hüyük would be discovered in Egypt, and become synonymous with the Minoan culture of Crete. The bull would gain prominence in the literary traditions of Mesopotamia in The Epic of Gilgamesh and in Greek mythology through the stories of Theseus and the Minotaur and Zeus and Europa.

Beginning in Sumeria, the bull would be associated with the gods and this practice would continue in Egyptian and Greek culture. In Egyptian culture the bull would reach the pinnacle of its veneration. From the similarities of bull-influenced tomb decorations to the shrines at Çatal Hüyük, to the worship of the Apis bull as the god Ptah, Egypt was the most important center of the bull-cult in the ancient Mediterranean. Bull sacrifice was practiced throughout antiquity and its symbolism was central to Roman Mithraism. The divine bull was a symbol of fertility, the moon, and the gods, but above all a symbol of rebirth and salvation.

Written by Darci Clark

Further reading: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sacred_bull

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

God's Axe

God’s Axe

“A double axe painted on a pottery from Knossos” On the edge of the Fayum, the pyramid of Hawara is considered the architectural masterpiece of the Middle Kingdom. Built of bricks covered with a limestone facing, it still forms a massive mound, housing an imposing funerary vault composed of enormous blocks of white quartzite. It was once flanked by an immense funerary temple, larger than the…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

The scale of time when these sculptures were made is difficult for a human mind to comprehend. Fat women have been appreciated and revered in art since art began. The modern view is the outlier, not the norm.

Image Rights (Top to Bottom)

Photo by Louvre Museum, CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Photo by Rob Koopman, CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Photo from Mellaart 1967, Çatal Hüyük: A Neolithic Town in Anatolia 145, plate 79, used under fair dealing

Photo by Nevit Dilmen, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Photo by Jason Quinlan, used under fair dealing

Photo by 120, CC BY 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons

Photo by Petr Novák, CC BY-SA 2.5, via Wikimedia Commons

Photo copyright Smithsonian Institution, used under fair dealing

Photo copyright H. Jensen, Universität Tübingen, used under Fair Dealing

649 notes

·

View notes

Note

If money was no object, tell me what your dream vacation would be. Where would you go and what would you do there.

Thank youuu

I'm thinking (mostly) Turkey! I would probably start in Istambul, go to the nearby ruins of Troy, and get a ferry to Lesbos in Greece, to Izmir, to the Greek island of Paros (to see the Paros Chronicle that was the topic of my master's thesis) and finally to Rhodes (also in Greece I think). From there I'd visit the ruins of Pergamon, Çatal Hüyük, Gobekli Tepe, Hattusas, and I'd end in the lake Van where I could probably find ruins / museums of Urartu. Maybe even I could go all the way to Yerevan and take the plane back home from there so I can also visit more Urartean stuff!

What about you??

(The pics are in order with all the places i've mentioned except for Troy and Yerevan cause it exceeds the photo limit 😔)

#ask#i would also stop by ankara while i was there tbh#I FORGOT THERA / SANTORINI I DON'T KNOW WHY I FORGOT IT#BUT OF COURSE I WOULD GO THERE AS WELL I WANNA SEE AKROTIRI#oh and if it weren't turkey i would visit either greece or the levant (syria lebanon jordan and palestine)#OH or tunisia and libya!!!#as you can see i wouldn't leave the mediterranean sjdjs

17 notes

·

View notes

Link

Excerpts from the above article:

The Grimaldi Goddess clay figurine, unearthed at the Neolithic settlement of Çatal Hüyük in Turkey, dates back to about 6000 BC. It depicts an obese woman giving birth while seated upon a throne. Although many have considered this a sure sign of feminine fertility, many scholars have dismissed the two massive dog-like beasts sitting by her side. The focus has continued being about sexual reproduction symbols, rather than her role in dog domestication and dominance over woman’s best and most loyal friend.

In northern Israel, archaeologists discovered the remains of a 12,000-year-old Natufian woman with her hand resting on a pet puppy, at the ‘Ain Mallaha site. This is one of the first known remains related to dog domestication. (The Israel Museum, Jerusalem )

At an excavation site near Lake Baikal in Siberia, the archaeologist and geneticist Andrea Waters Rist from Leiden University discovered two 8,000-year-old skeletal remains of Neolithic Siberian women carrying signs of the parasitic infection known as echinococcosis. This disease occurs when humans have long interaction and contact with canines through the sharing of food, water, and in some instances from being exposed to canine fecal matter. Waters-Rist’s analysis concludes that ancient Siberian women of this forgotten tribe might have been responsible for the caring, feeding, and rearing of dogs. Within every culture, there is distinct evidence that women were significant to the rearing and training of dogs. Shortly after the domestication of the dog, humans lived side by side with these animals, considered them equals, and depended on them for protection and assistance in their everyday lives. According to scholars such as Waters-Rist, it is therefore not surprising that humans would also endure the same sicknesses as well. As time went on, dogs were reared by both men and women, and they eventually became part of the family unit across many cultures. Without the friendship and alliance of dogs, there would be no human civilization. This fact must have been well understood in the ancient world, as there are several goddesses associated with dogs. Could these dog-friendly deities provide clues to the relationship between women and dogs?

Dog-Friendly Deities: Women and Dogs in Mythology

Aside from the Grimaldi Goddess figurine hypothesis previously mentioned, the list of gods who demonstrate a strong relationship with dogs include the goddess Gula, also known as Bau, Nintinugga, and Basat, who was often represented sitting near dogs. The goddess of dogs and healing, in her earliest form she was described as the dogs' controller, but she became associated with spells and healing in later years. Her temples were prevalent in Mesopotamia, Babylonia and Sumer, and stray dogs were allowed to roam within their walls. Altars at her temples were littered with dog statues, dedicated to her in the hope she would provide speedy recovery for loved ones. Her sacred symbol remained that of the dog until she was forgotten over time.

Left; Detail of the goddess Nintinugga, her dog, and a scorpion man from kudurru of Nebuchadnezzar granting Šitti-Marduk freedom from taxation. British Museum. ( CC BY-SA 4.0 ). Right Public Domain )

Other powerful mythical deities and goddesses were associated with hunting. The goddess Atalanta was often painted equipped with a bow, spear, and dogs, not to mention a severed boar head, representing luck with the hunt and fruitful prosperity. As the scholar Adrienne Mayor has mentioned, vase paintings depicted Amazon archers accompanied by dogs as they ran to battle or hunted. The eternal bond between women and dogs, especially on Greek vases, is evidence of an unbreakable connection. The goddess Artemis (Diana) is another deity which illustrates the connection between women, hunting and a feminine command over dogs, wolves, and animals. Another Greek goddess was Hecate, who was responsible for crossroads and entryways, as well as dogs. However, her depiction was far more sinister, as she represented the unpredictability of magic and spells. She was a shapeshifter, described as having three heads and was often responsible for dog barking, since they were obliged to announce her entrance anywhere she went.

Amongst the ancient Greeks, there are a few common themes related to women and dogs, in that their companionship was seen as old and mysterious, but beneficial for all. Much ancient Greek art portrays men hunting with hounds, but the representation of warrior women and ancient hunting deities could help shine a light on a past when women trained dogs for hunting and gathering.

There is not much evidence to speak for this hypothesis, besides some Greco-Roman art and a few Scythian warrior women gravesites with hounds. There is however significant evidence of women rearing and training dogs for the purpose of assisting in hunting and carrying supplies. The most extraordinary evidence can be seen with the ethnographic accounts of early North American Plains Indians as they spoke of the time before the arrival of Spanish horses.

Detail from a Karl Bodmer painting showing a dog with a travois in an Assiniboine camp in the Great Plains. ( Public domain )

Women and Dogs in North American Plains Indian Culture

The most famous account is from the Hidatsa elder Buffalo Bird Woman. In her stories from the past, she discusses the older way of life for women and dogs within the American Plains culture. Her account explains that even after incorporating horses, it was only the more affluent families that could afford to house them. Most families still relied heavily on dog transportation by way of travois, two-pole sleds used by North American Plains Indians to carry goods, and their brutal nomadic way of life.

She states that women were considered the owners of dogs. They were expected to raise them, clean them, and train them. Like in many other cultures, the methods for domesticating dogs revealed a selection process over generations favoring the more complacent over the vicious and mercurial. The most favorable of puppies had large round faces, big legs, and floppy ears. These traits revealed a loyal and happy dog that would grow up big. Puppies that did not meet these criteria were often killed or given away.

Her narrative involves women training the dogs in hauling weights, in order to get an adult canine ready and able to carry between 50 and 70 pounds (22 to 32 kilos) by travois. Once this task was completed, the dog would be used for multiple purposes. In some situations, anywhere from 20 to 70 dogs would be brought on hunts and expected to carry the processed buffalo meat back to camp without being tempted to eat any of it. Women would also take packs of between 12 and 20 dogs to collect firewood and supplies to sustain their families one month at a time. With every task given, it was still customary for a woman to care and equip the dogs, as well as ensure they were comfortable in their tasks.

According to Buffalo Bird Woman’s account, dogs would always follow in single file behind their women owners, and if any of the dogs tired, the women would know how to keep them encouraged. In the summer, women knew not to load dogs as heavily as in winter. This had to do with the heat and the friction from the ground. During winter, the weather and snow worked in a travois-pulling dog’s favor. It was also necessary for women to continue keeping the dogs hydrated throughout the day, for they were always in use.

#hekate#wolf domestication#feminist witch#goddess worship#canine domestication#atalanta#artemis#diana#women's history

205 notes

·

View notes

Text

Two Hundred Fifty Things an Architect Should Know

by Michael Sorkin

1. The feel of cool marble under bare feet. 2. How to live in a small room with five strangers for six months. 3. With the same strangers in a lifeboat for one week. 4. The modulus of rupture. 5. The distance a shout carries in the city. 6. The distance of a whisper. 7. Everything possible about Hatshepsut’s temple (try not to see it as ‘modernist’ avant la lettre).

The Temple of Hatshepsut

8. The number of people with rent subsidies in New York City. 9. In your town (include the rich). 10. The flowering season for azaleas. 11. The insulating properties of glass. 12. The history of its production and use. 13. And of its meaning. 14. How to lay bricks. 15. What Victor Hugo really meant by ‘this will kill that.’ 16. The rate at which the seas are rising. 17. Building information modeling (BIM). 18. How to unclog a Rapidograph. 19. The Gini coefficient. 20. A comfortable tread-to-riser ratio for a six-year-old. 21. In a wheelchair. 22. The energy embodied in aluminum. 23. How to turn a corner. 24. How to design a corner. 25. How to sit in a corner. 26. How Antoni Gaudí modeled the Sagrada Família and calculated its structure. 27. The proportioning system for the Villa Rotonda. 28. The rate at which that carpet you specified off-gasses. 29. The relevant sections of the Code of Hammurabi. 30. The migratory patterns of warblers and other seasonal travellers. 31. The basics of mud construction. 32. The direction of prevailing winds. 33. Hydrology is destiny. 34. Jane Jacobs in and out. 35. Something about feng shui. 36. Something about Vastu Shilpa. 37. Elementary ergonomics. 38. The color wheel. 39. What the client wants. 40. What the client thinks it wants. 41. What the client needs. 42. What the client can afford. 43. What the planet can afford. 44. The theoretical bases for modernity and a great deal about its factions and inflections. 45. What post-Fordism means for the mode of production of building. 46. Another language. 47. What the brick really wants. 48. The difference between Winchester Cathedral and a bicycle shed. 49. What went wrong in Fatehpur Sikri. 50. What went wrong in Pruitt-Igoe. 51. What went wrong with the Tacoma Narrows Bridge. 52. Where the CCTV cameras are. 53. Why Mies really left Germany. 54. How people lived in Çatal Hüyük. 55. The structural properties of tufa. 56. How to calculate the dimensions of brise-soleil. 57. The kilowatt costs of photovoltaic cells. 58. Vitruvius. 59. Walter Benjamin. 60. Marshall Berman. 61. The secrets of the success of Robert Moses. 62. How the dome on the Duomo in Florence was built.

Duomo in Florence

63. The reciprocal influences of Chinese and Japanese building. 64. The cycle of the Ise Shrine. 65. Entasis. 66. The history of Soweto. 67. What it’s like to walk down the Ramblas. 68. Back-up. 69. The proper proportions of a gin martini. 70. Shear and moment. 71. Shakespeare, et cetera. 72. How the crow flies. 73. The difference between a ghetto and a neighborhood. 74. How the pyramids were built. 75. Why. 76. The pleasures of the suburbs. 77. The horrors. 78. The quality of light passing through ice. 79. The meaninglessness of borders. 80. The reasons for their tenacity. 81. The creativity of the ecotone. 82. The need for freaks. 83. Accidents must happen. 84. It is possible to begin designing anywhere. 85. The smell of concrete after rain. 86. The angle of the sun at the equinox. 87. How to ride a bicycle. 88. The depth of the aquifer beneath you. 89. The slope of a handicapped ramp. 90. The wages of construction workers. 91. Perspective by hand. 92. Sentence structure. 93. The pleasure of a spritz at sunset at a table by the Grand Canal. 94. The thrill of the ride. 95. Where materials come from. 96. How to get lost. 97. The pattern of artificial light at night, seen from space. 98. What human differences are defensible in practice. 99. Creation is a patient search. 100. The debate between Otto Wagner and Camillo Sitte. 101. The reasons for the split between architecture and engineering. 102. Many ideas about what constitutes utopia. 103. The social and formal organization of the villages of the Dogon. 104. Brutalism, Bowellism, and the Baroque. 105. How to dérive. 106. Woodshop safety. 107. A great deal about the Gothic. 108. The architectural impact of colonialism on the cities of North Africa. 109. A distaste for imperialism. 110. The history of Beijing.

Beijing Skyline

111. Dutch domestic architecture in the 17th century. 112. Aristotle’s Politics. 113. His Poetics. 114. The basics of wattle and daub. 115. The origins of the balloon frame. 116. The rate at which copper acquires its patina. 117. The levels of particulates in the air of Tianjin. 118. The capacity of white pine trees to sequester carbon. 119. Where else to sink it. 120. The fire code. 121. The seismic code. 122. The health code. 123. The Romantics, throughout the arts and philosophy. 124. How to listen closely. 125. That there is a big danger in working in a single medium. The logjam you don’t even know you’re stuck in will be broken by a shift in representation. 126. The exquisite corpse. 127. Scissors, stone, paper. 128. Good Bordeaux. 129. Good beer. 130. How to escape a maze. 131. QWERTY. 132. Fear. 133. Finding your way around Prague, Fez, Shanghai, Johannesburg, Kyoto, Rio, Mexico, Solo, Benares, Bangkok, Leningrad, Isfahan. 134. The proper way to behave with interns. 135. Maya, Revit, Catia, whatever. 136. The history of big machines, including those that can fly. 137. How to calculate ecological footprints. 138. Three good lunch spots within walking distance. 139. The value of human life. 140. Who pays. 141. Who profits. 142. The Venturi effect. 143. How people pee. 144. What to refuse to do, even for the money. 145. The fine print in the contract. 146. A smattering of naval architecture. 147. The idea of too far. 148. The idea of too close. 149. Burial practices in a wide range of cultures. 150. The density needed to support a pharmacy. 151. The density needed to support a subway. 152. The effect of the design of your city on food miles for fresh produce. 153. Lewis Mumford and Patrick Geddes. 154. Capability Brown, André Le Nôtre, Frederick Law Olmsted, Muso Soseki, Ji Cheng, and Roberto Burle Marx. 155. Constructivism, in and out. 156. Sinan. 157. Squatter settlements via visits and conversations with residents. 158. The history and techniques of architectural representation across cultures. 159. Several other artistic media. 160. A bit of chemistry and physics. 161. Geodesics. 162. Geodetics. 163. Geomorphology. 164. Geography. 165. The Law of the Andes. 166. Cappadocia first-hand.

Cappadocia

167. The importance of the Amazon. 168. How to patch leaks. 169. What makes you happy. 170. The components of a comfortable environment for sleep. 171. The view from the Acropolis. 172. The way to Santa Fe. 173. The Seven Wonders of the Ancient World. 174. Where to eat in Brooklyn. 175. Half as much as a London cabbie. 176. The Nolli Plan. 177. The Cerdà Plan. 178. The Haussmann Plan. 179. Slope analysis. 180. Darkroom procedures and Photoshop. 181. Dawn breaking after a bender. 182. Styles of genealogy and taxonomy. 183. Betty Friedan. 184. Guy Debord. 185. Ant Farm. 186. Archigram. 187. Club Med. 188. Crepuscule in Dharamshala. 189. Solid geometry. 190. Strengths of materials (if only intuitively). 191. Ha Long Bay. 192. What’s been accomplished in Medellín. 193. In Rio. 194. In Calcutta. 195. In Curitiba. 196. In Mumbai. 197. Who practices? (It is your duty to secure this space for all who want to.) 198. Why you think architecture does any good. 199. The depreciation cycle. 200. What rusts. 201. Good model-making techniques in wood and cardboard. 202. How to play a musical instrument. 203. Which way the wind blows. 204. The acoustical properties of trees and shrubs. 205. How to guard a house from floods. 206. The connection between the Suprematists and Zaha. 207. The connection between Oscar Niemeyer and Zaha. 208. Where north (or south) is. 209. How to give directions, efficiently and courteously. 210. Stadtluft macht frei. 211. Underneath the pavement the beach. 212. Underneath the beach the pavement. 213. The germ theory of disease. 214. The importance of vitamin D. 215. How close is too close. 216. The capacity of a bioswale to recharge the aquifer. 217. The draught of ferries. 218. Bicycle safety and etiquette. 219. The difference between gabions and riprap. 220. The acoustic performance of Boston Symphony Hall.

Boston Symphony Hall

221. How to open the window. 222. The diameter of the earth. 223. The number of gallons of water used in a shower. 224. The distance at which you can recognize faces. 225. How and when to bribe public officials (for the greater good). 226. Concrete finishes. 227. Brick bonds. 228. The Housing Question by Friedrich Engels. 229. The prismatic charms of Greek island towns. 230. The energy potential of the wind. 231. The cooling potential of the wind, including the use of chimneys and the stack effect. 232. Paestum. 233. Straw-bale building technology. 234. Rachel Carson. 235. Freud. 236. The excellence of Michel de Klerk. 237. Of Alvar Aalto. 238. Of Lina Bo Bardi. 239. The non-pharmacological components of a good club. 240. Mesa Verde National Park. 241. Chichen Itza. 242. Your neighbors. 243. The dimensions and proper orientation of sports fields. 244. The remediation capacity of wetlands. 245. The capacity of wetlands to attenuate storm surges. 246. How to cut a truly elegant section. 247. The depths of desire. 248. The heights of folly. 249. Low tide. 250. The Golden and other ratios.

940 notes

·

View notes

Text

TWO HUNDRED FIFTY THINGS AN ARCHITECT SHOULD KNOW

Michael Sorkin

1. The feel of cool marble under bare feet. 2. How to live in a small room with five strangers for six months. 3. With the same strangers in a lifeboat for one week. 4. The modulus of rupture. 5. The distance a shout carries in the city. 6. The distance of a whisper. 7. Everything possible about Hatshepsut’s temple (try not to see it as ‘modernist’ avant la lettre). 8. The number of people with rent subsidies in New York City. 9. In your town (include the rich). 10. The flowering season for azaleas. 11. The insulating properties of glass. 12. The history of its production and use. 13. And of its meaning. 14. How to lay bricks. 15. What Victor Hugo really meant by ‘this will kill that.’ 16. The rate at which the seas are rising. 17. Building information modeling (BIM). 18. How to unclog a Rapidograph. 19. The Gini coefficient. 20. A comfortable tread-to-riser ratio for a six-year-old. 21. In a wheelchair. 22. The energy embodied in aluminum. 23. How to turn a corner. 24. How to design a corner. 25. How to sit in a corner. 26. How Antoni Gaudí modeled the Sagrada Família and calculated its structure. 27. The proportioning system for the Villa Rotonda. 28. The rate at which that carpet you specified off-gasses. 29. The relevant sections of the Code of Hammurabi. 30. The migratory patterns of warblers and other seasonal travellers. 31. The basics of mud construction. 32. The direction of prevailing winds. 33. Hydrology is destiny. 34. Jane Jacobs in and out. 35. Something about feng shui. 36. Something about Vastu Shilpa. 37. Elementary ergonomics. 38. The color wheel. 39. What the client wants. 40. What the client thinks it wants. 41. What the client needs. 42. What the client can afford. 43. What the planet can afford. 44. The theoretical bases for modernity and a great deal about its factions and inflections. 45. What post-Fordism means for the mode of production of building. 46. Another language. 47. What the brick really wants. 48. The difference between Winchester Cathedral and a bicycle shed. 49. What went wrong in Fatehpur Sikri. 50. What went wrong in Pruitt-Igoe. 51. What went wrong with the Tacoma Narrows Bridge. 52. Where the CCTV cameras are. 53. Why Mies really left Germany. 54. How people lived in Çatal Hüyük. 55. The structural properties of tufa. 56. How to calculate the dimensions of brise-soleil. 57. The kilowatt costs of photovoltaic cells. 58. Vitruvius. 59. Walter Benjamin. 60. Marshall Berman. 61. The secrets of the success of Robert Moses. 62. How the dome on the Duomo in Florence was built. 63. The reciprocal influences of Chinese and Japanese building. 64. The cycle of the Ise Shrine. 65. Entasis. 66. The history of Soweto. 67. What it’s like to walk down the Ramblas. 68. Back-up. 69. The proper proportions of a gin martini. 70. Shear and moment. 71. Shakespeare, et cetera. 72. How the crow flies. 73. The difference between a ghetto and a neighborhood. 74. How the pyramids were built. 75. Why. 76. The pleasures of the suburbs. 77. The horrors. 78. The quality of light passing through ice. 79. The meaninglessness of borders. 80. The reasons for their tenacity. 81. The creativity of the ecotone. 82. The need for freaks. 83. Accidents must happen. 84. It is possible to begin designing anywhere. 85. The smell of concrete after rain. 86. The angle of the sun at the equinox. 87. How to ride a bicycle. 88. The depth of the aquifer beneath you. 89. The slope of a handicapped ramp. 90. The wages of construction workers. 91. Perspective by hand. 92. Sentence structure. 93. The pleasure of a spritz at sunset at a table by the Grand Canal. 94. The thrill of the ride. 95. Where materials come from. 96. How to get lost. 97. The pattern of artificial light at night, seen from space. 98. What human differences are defensible in practice. 99. Creation is a patient search. 100. The debate between Otto Wagner and Camillo Sitte. 101. The reasons for the split between architecture and engineering. 102. Many ideas about what constitutes utopia. 103. The social and formal organization of the villages of the Dogon. 104. Brutalism, Bowellism, and the Baroque. 105. How to dérive. 106. Woodshop safety. 107. A great deal about the Gothic. 108. The architectural impact of colonialism on the cities of North Africa. 109. A distaste for imperialism. 110. The history of Beijing. 111. Dutch domestic architecture in the 17th century. 112. Aristotle’s Politics. 113. His Poetics. 114. The basics of wattle and daub. 115. The origins of the balloon frame. 116. The rate at which copper acquires its patina. 117. The levels of particulates in the air of Tianjin. 118. The capacity of white pine trees to sequester carbon. 119. Where else to sink it. 120. The fire code. 121. The seismic code. 122. The health code. 123. The Romantics, throughout the arts and philosophy. 124. How to listen closely. 125. That there is a big danger in working in a single medium. The logjam you don’t even know you’re stuck in will be broken by a shift in representation. 126. The exquisite corpse. 127. Scissors, stone, paper. 128. Good Bordeaux. 129. Good beer. 130. How to escape a maze. 131. QWERTY. 132. Fear. 133. Finding your way around Prague, Fez, Shanghai, Johannesburg, Kyoto, Rio, Mexico, Solo, Benares, Bangkok, Leningrad, Isfahan. 134. The proper way to behave with interns. 135. Maya, Revit, Catia, whatever. 136. The history of big machines, including those that can fly. 137. How to calculate ecological footprints. 138. Three good lunch spots within walking distance. 139. The value of human life. 140. Who pays. 141. Who profits. 142. The Venturi effect. 143. How people pee. 144. What to refuse to do, even for the money. 145. The fine print in the contract. 146. A smattering of naval architecture. 147. The idea of too far. 148. The idea of too close. 149. Burial practices in a wide range of cultures. 150. The density needed to support a pharmacy. 151. The density needed to support a subway. 152. The effect of the design of your city on food miles for fresh produce. 153. Lewis Mumford and Patrick Geddes. 154. Capability Brown, André Le Nôtre, Frederick Law Olmsted, Muso Soseki, Ji Cheng, and Roberto Burle Marx. 155. Constructivism, in and out. 156. Sinan. 157. Squatter settlements via visits and conversations with residents. 158. The history and techniques of architectural representation across cultures. 159. Several other artistic media. 160. A bit of chemistry and physics. 161. Geodesics. 162. Geodetics. 163. Geomorphology. 164. Geography. 165. The Law of the Andes. 166. Cappadocia first-hand. 167. The importance of the Amazon. 168. How to patch leaks. 169. What makes you happy. 170. The components of a comfortable environment for sleep. 171. The view from the Acropolis. 172. The way to Santa Fe. 173. The Seven Wonders of the Ancient World. 174. Where to eat in Brooklyn. 175. Half as much as a London cabbie. 176. The Nolli Plan. 177. The Cerdà Plan. 178. The Haussmann Plan. 179. Slope analysis. 180. Darkroom procedures and Photoshop. 181. Dawn breaking after a bender. 182. Styles of genealogy and taxonomy. 183. Betty Friedan. 184. Guy Debord. 185. Ant Farm. 186. Archigram. 187. Club Med. 188. Crepuscule in Dharamshala. 189. Solid geometry. 190. Strengths of materials (if only intuitively). 191. Ha Long Bay. 192. What’s been accomplished in Medellín. 193. In Rio. 194. In Calcutta. 195. In Curitiba. 196. In Mumbai. 197. Who practices? (It is your duty to secure this space for all who want to.) 198. Why you think architecture does any good. 199. The depreciation cycle. 200. What rusts. 201. Good model-making techniques in wood and cardboard. 202. How to play a musical instrument. 203. Which way the wind blows. 204. The acoustical properties of trees and shrubs. 205. How to guard a house from floods. 206. The connection between the Suprematists and Zaha. 207. The connection between Oscar Niemeyer and Zaha. 208. Where north (or south) is. 209. How to give directions, efficiently and courteously. 210. Stadtluft macht frei. 211. Underneath the pavement the beach. 212. Underneath the beach the pavement. 213. The germ theory of disease. 214. The importance of vitamin D. 215. How close is too close. 216. The capacity of a bioswale to recharge the aquifer. 217. The draught of ferries. 218. Bicycle safety and etiquette. 219. The difference between gabions and riprap. 220. The acoustic performance of Boston Symphony Hall. 221. How to open the window. 222. The diameter of the earth. 223. The number of gallons of water used in a shower. 224. The distance at which you can recognize faces. 225. How and when to bribe public officials (for the greater good). 226. Concrete finishes. 227. Brick bonds. 228. The Housing Question by Friedrich Engels. 229. The prismatic charms of Greek island towns. 230. The energy potential of the wind. 231. The cooling potential of the wind, including the use of chimneys and the stack effect. 232. Paestum. 233. Straw-bale building technology. 234. Rachel Carson. 235. Freud. 236. The excellence of Michel de Klerk. 237. Of Alvar Aalto. 238. Of Lina Bo Bardi. 239. The non-pharmacological components of a good club. 240. Mesa Verde National Park. 241. Chichen Itza. 242. Your neighbors. 243. The dimensions and proper orientation of sports fields. 244. The remediation capacity of wetlands. 245. The capacity of wetlands to attenuate storm surges. 246. How to cut a truly elegant section. 247. The depths of desire. 248. The heights of folly. 249. Low tide. 250. The Golden and other ratios. https://www.readingdesign.org/

1 note

·

View note

Video

youtube

Coil: “Another Brown World” (Unnatural History II: Smiling in the Face of Perversity, Threshold House 1995)

This cut appeared on the second installment of Coil’s Unnatural History series after originally being released on Sub Rosa’s 1989 compilation, Myths 4: Sinpole Twilight in Çatal Hüyük.

26 notes

·

View notes