#but like 1 trans man scientist on that whole list.

Text

once again beefed by the utter lack of cool trans men literally anywhere. I found a list of notable trans ppl and it was only 16% trans men and most of them were from like 1900

#like sorry to be bitching but it is a thread ive noticed#i know some of it is that trans women have essier access to cool shit pre transition#stem game shops etc#and trans men dont get to pretransition bc of misogyny#but post transition so many of us seem to stay fucking lame#at best a cool artist#but like 1 trans man scientist on that whole list.#meanwhile trans chicks are responsible for all of computers basically#(shoots you with a beam)

0 notes

Text

TOP five people named magnus in the world

5. Magnus carlsen

magnis carlsen is the worlds most powerful chess player, having earned the rank of "grand master". this has made him an incredible figure in the chess world. however, recently his fame has been rocked by scandal. there are rumors that he cheated by using a vibrating buttplug to enhance his chess skills while playing the game. these shocking allegations call his grand master status into question. however, whether he used artifical "doping" to win his title or not, his extreme chess power earns him a spot on this list.

4. Magnus archives

Mangus archives, also known by the nickname "trans misogyny affected" by many of his fans, is one of the most popular podcasting stars in the world. although he retired from his podcasting career in 2021, his fans still think that he is one of the greatest podcasters who ever lived, along side the likes of joe rogan and el chapo. thanks to his incredible podcasting prowess, magnus archives earns a spot on this list.

3. Magnus herchfeld

Magnus hirschfeld was a german scientist who is largely credited with being the first man to discover how to have gay sex. while many other scientists had tried before, none could compete with doctor hirchfeld's revolutionary theories. he even started a school, called the institüte for sexualwitchencraft, for teaching his discoveries. however, his school was destroyed by adolf hitler when the nazis came to germany. for his revolutionary discovery of gay people everywhere, mangus hirschfeld earns a spot on my list.

2. Mangus Maximus

this guy was a roman emperor so powerful, he even got his face on a coin. he became the emporer of rome in 300 bc, and used his military skills to conquer wales. nobody has ever heard of this guys because he died thousands of years ago, but that doesn't change just how awesome of a magnus he was. so don't forget this old faithful! for that reason, he earns a spot on my list.

1. Magnus Von Grapple!!!!!!!!!!

that's right folks, the one youve all been waiting for. magnus von grapple is the most famous magnus of all time, because he's a giant and powerful robot. try to compete with THAT. ever since he made his appearance in "paper mario", his fans have been rooting for him above all else. there is a whole list of things which makes this magnus the best, but lets just say: if you disagree, he could smash you with his feet. the all time greatest magnus of all time, for that reason, he earns the number one spot on this list.

281 notes

·

View notes

Note

Do you mind if I ask your top 10 favorite characters (can be male or female) from all of the media that you loved (can be anime/manga, books, movies or tv series)? And why do you love them? Sorry if you've answered this question before.....Thanks....

I always like talking about characters, so no problem, ask away. This was a pretty tough question and I had to do a lot of soul searching for that. Turns out I don't actually have any major favourite characters for movies or TV shows. Like, I will have favourite characters in a show, but I'm not that wild about them that they could compare to others across mediums. I guess with the many movies and TV shows I like, I always tend to prioritize the plot more and the characters kind of seamlessly integrate into that. So the characters that did make the list are from animangas, video games, comic books and Warhammer. I can't really rank them from 1 to 10, I just ordered them by franchise/medium.

Lucifer/Louis Cypher (Shin Megami Tensei games)

This doesn't include the Lucifer from SMTIV, I prefer to forget that ever happened. As a quick summary, in SMT there's this big war going on between the forces of chaos and order. Gods and mythical beings of all kinds fall somewhere between the two sides. An Abrahamic god, angels and forces of light usually belong to order (who exactly can change based on the game) and Lucifer is the leader of the forces of chaos. Contrary to Order, he tends to get personally involved with the player and tries to lead them subtly towards chaos, but somehow still manages to come off as very sympathetic. That's what I like about him and find so fascinating. He's a big fighter for free will and will never openly judge you for the choices you make, unlike the order-aligned characters, who fly into a rage. He will fight you to ensure chaos wins, but it's never really seen as you doing some personal failing. Especially in SMT II he is essentially an ally and even if you defeat him, he will offer to help you slay YHVH as long as you don't join order. I'm currently playing SMT Nocturne again and am trying to go for the True Demon Ending (leading Lucifers army towards heaven) and I have to say especially in his old man form it's always nice to see him stop by to check up on me. The little kid form is much nastier, but whenever I'm running through the apocalyptic landscape or crawling through some dungeon and he shows up in his wheelchair it makes me feel supported. Like "aw, grandpa is watching me, I have to do my best". Anyway, I think the place he has in the games is very interesting. He's also the reason why many people say the games are leading you to side more with chaos over order, even though it's always made clear that you will be working towards a world of eternal war. Lucifer is just very charming, as you would expect, and seems even more so when you compare him with the prospect of losing all autonomy.

Kenjaku (JJK)

I think this is pretty self-explanatory, since I won't shut up about them on this blog. They combine a lot of things I really like about fictional characters. They're a mad scientist, they are mainly driven by their own curiosity and therefore a chaotic force in the plot, they're trans, they are genre-savvy and then there is the whole business of being the main characters evil mother. Kenjaku is also another excuse to brush up my knowledge on Japanese history. What really hooked me in was the whole toxic family business and the time while they stayed with the Itadori family. For most of the story they're this big bad, who managed to destroy half of Japan in 2 weeks, but then we find out about that and it all seems so low key and relatively normal, that it makes them even more fascinating. They're the main villain, but they're also very chill for most of the story and don't immediately send off alarm bells in the average person's head unlike Sukuna for example. That's what allowed them to stay undercover for so long (that and Tengen). I don't think I've come across another character before who hits so many of my fave character boxes.

Phosphophylite (Houseki no Kuni)

Pretty new addition to my list, but their character development across the series really hit me like a train. It's honestly so perfect, it's hard to summarize why I love it so much. In the beginning of the story they are relatively innocent, weak, but also with some clear character flaws. As they gain strength these flaws only become even more pronounced and extreme as they go through trauma after trauma. Every step of the story serves to chip away at Phos both physically and mentally until there's only splinter left of them. The story is almost over and while Phos has undoubtedly changed, they have also held onto their most intrinsic characteristic and you could say that what really made them who they are has only become more clear now. They have idealistic goals and only end up hurting the people they want to protect with every step they take towards them, until they're completely alone at the end. They are driven completely insane by their actions and the suffering others put them through until they snap completely and destroy everything. That destruction was a much needed restart however, as much as it hurt to lose so many people. There's so much I could talk about with them, I just think they are such a fascinating character and definitely one of my favourite mcs ever.

Johan Liebert (Monster)

It's been a while since I read/watched Monster, but every time I look in the direction of the series, it makes me insane all over again. Johan is probably the only anime villain I find actually scary. It's the mystery around his character, he's very unpredictable and just like the characters you start to see him everywhere in every little hint you are given. The finale in Ruhenheim was so stressful to watch and Johan didn't even do anything for most of it, it was all just vague glimpses and build up tension. Every time we do see him on screen we know something bad will happen and even if he's interacting with someone friendly you are just waiting for that other person to suffer for being in his presence for too long. I could watch episode 49 again and again because things go downhill so fast and you know from the beginning that Johan interacting with children is bad. I'm getting war flashbacks any time I hear Noto Mamiko talk in another anime. Immediate red flag. Do not trust. Same goes for hearing the phrase 昔々ある所に. As if there wasn't enough reason to be vary of German and Eastern European fairy tales. All that doesn't even touch on his relationship with Nina. They are so destructive, but still love each other. The whole reveal surrounding the rose mansion was so good and gave them a whole new depth. That's another thing that I love, Nina shows that while what Johan went through is tragic and horrible, there was nothing forcing him to become the serial killer he is now, which I think is a very important part of his character.

Satan/Ryo Asuka (Devilman franchise)

Satan is the whole reason I love Devilman so much, they're the center piece of the series, the series and its sequels only exist because God wants to punish Satan for being gay and an environmentalist, but unfortunately that often gets overlooked in the broader anime community. They think it's all just about Devilman/Akira killing people and the world dying and sideline the suffering twink who started it all. Even in the worst parts of the franchise (Devilman Lady), Satan and his bond with Akira can save the story from being complete shit. On the surface it's pretty basic, but Satan's wish to save the planet and demons by wiping out humanity and thereby destroying what he wanted to protect gets me every time. He ends up falling in love with a human, wants to save him from the war he's about to unleash by giving him special powers and eventually ends up fighting and killing him because of that. God swoops in and puts the timeline on loop to torture Satan. Satan tries to escape, but thereby only ends up killing the one he loves over and over again. Wonderfully tragic and I like how the story ends up siding with Satan. It would be better for humans to die, but seeing loved ones die still hurts. Basically, I'm not immune to suffering gays who want to fight God.

Thief King Bakura (Yu-Gi-Oh!)

Best character in the series, never did anything wrong and should've won or at least got to kill Atem and/or Atem's father. He only got used his whole life and I hate how dirty the anime and especially the eng dub did him. They really tried to say that melting the entire population of a village in gold was fully justified because they were thieves and Bakura has no right to complain because "he uses violence too (against the pharaoh...)". Ugh, it always makes me so mad just to think about it. Thankfully, the manga handled it better, even if they didn't quite stick the landing. I just love his whole story. Little boy goes up against the Pharaoh and his entire court, protected by the spirits of his home and even almost manages to take revenge, when he goes just a little too far and in his desperation gets involved with dark powers that are out to use him. I especially like that the manifestation of his ka, Diabound, is a holy spirit in the manga, showing that his initial goal was actually justified and the ruling class, who pass their time by torturing people for fun, are wrong. If only Zorc hadn't shown up... He gave us Yami Bakura though, so I'm not too mad. Yami Bakura instantly became my fave for liking ttrpgs over the Duel Monster card game and he stuck to that throughout his plan. No children's card games if he has a say in it. It's also hilarious that the others kill and torture each other with card games, but he just takes a knife and does it the old-fashioned way. Why gamble over cards, when you can simply stab the people and then take their belongings?

Lucifer Morningstar (Lucifer comics by Mike Carey)

My time again to tell everyone to read the Lucifer comics because even if you don't like comics, they are just insanely good. If you like The Sandman (TV series or comics), then definitely give them a go. There's technically also a TV series based on them, but aside from some names it has nothing in common with the source material. Don't know why they bothered getting the rights. It's basically a long discussion about free will and what it really means to be free. The ending really devastated me when I first read it, but I really like it and it makes the most sense. I had to think about Lucifer and how he's written a lot recently because of the Gojo vs Sukuna fight. In my opinion, Lucifer is the best overpowered mc I've seen so far. He has at his best the power to create whole multiverses, but the author uses his character traits to make sure he still struggles and faces challenges. It also helps that Lucifer is not a good fighter. The other fallen angels carried him hard in the war against heaven. If he doesn't have the option to oneshot his enemy, he will get beaten up badly. But more importantly, Lucifer has one goal in life and that is to be free and to escape his father's all-seeing, all-knowing eye and predestination itself. That is of course pretty difficult, not even creating his own multiverse helps because God/The Presence foresaw that too. At it's core the story is about escaping a controlling parent. This is made even more difficult by Lucifer's lack of empathy and resulting difficulties in cooperating with other people. There are very few people he cares about and even the ones he does he ends up pushing away because he can't understand their needs and always thinks about himself first. Quite often he doesn't even notice that he angered someone until it blows up in his face. Usually, he just assumes that everyone hates him anyway (it's often true), but with the few who do like him, he often ends up distancing himself from them because his plans are more important to him than them and they obviously don't always have much understanding for that. Basically, he's a selfish dick and I love that about him. I can emphasize with his struggles and philosophy, but how he goes about it is sometimes so maddening and that's what makes me invested. He also always gets retribution when he makes mistakes or treats other gods dismissively. He can literally move mountains, but because of his own limitations, he is often very vulnerable and arguably a bigger hurdle to overcome than his father. Because of his rather cold if snarky nature, it's also always nice when he does show a slither of care towards someone else.

Xaiozanus Exasas (Imperator: Wrath of the Omnissiah by Gav Thorpe)

The last three on this list are all Warhammer 40k characters, mostly taken from the novels like Exasas here. Full name and title is: Magos Dominus Militaris Xaiozanus Skitara Xilliarkis Exasas. So you know they are important. Aside from how giddy it makes me that there's a mc in a (Warhammer) novel that uses neopronouns, Exasas is also just so cute and lovable that it's impossible I think not to like ver. Ve is a magos of the Adeptus Mechanicus, meaning a cyborg employed to oversee all machine and tactical decisions in an Imperator Titan (basically a Gundam but the size of a city). Ve looks like a mechanical centipede with humanoid upper body and three oculars for eyes. Besides the threat of infiltration, a big part of the book is Exasas learning to get out of vis head so to say, let go of pure logic and make impulsive decisions. Exasas loves to predict battle outcomes and basically anything that is happening around ver, ve can spend hours brooding over hypothetical problems ve made up for verself. A considerable part of vis part of the plot is Exasas sitting in a corner and crunching numbers to distract verself from the people around ver bullying ver. Unfortunately, that also leads to ver overlooking a crew member that switched sides, which is what eventually forces ver to engage more with the real world and when ve can't find any logic in the actions of this person to disregard logic and consider improbabilities and make actions based on vis gut (I'm pretty sure Exasas doesn't have a gut anymore tho). Exasas isn't very relatable or anything, I have to admit that I skimmed some of vis repetitive combat predictions, but this very different way of thinking is what makes it so fascinating. It's not that uncommon for techpriests, but we rarely see it depicted like this. Exasas creates entire separate personalities in vis head to have discussions with or to administer special problems to while ve thinks about something else. There's also a Fighter Ego, which is less logically based because it needs to make quick decisions and eventually helps Exasas somewhat with vis struggle for action in other scenarios. Exasas body is technically made for combat as well, but ve verself isn't a very confrontational person, so ve split off all functions related to that into a separate part of verself that is only sometimes allowed to take over. In other words, there's a lot going on in that metal head and it's super interesting to read about.

Trazyn the Infinite

Trazyn shows up all over wh40k, but I mainly know him from the books The Infinite and The Divine and War in the Museum (yes this is a play on Night at the Museum), both written by Robert Rath. Trazyn is a Necron, which are basically robot ancient egyptians. They used to be the Necrontyr, but their souls/consciousness were then poured into skeletal robot bodies. Many didn't survive that and are no more than drones without will, others fell asleep and never woke up, but some like Trazyn kept their personality and most of their memories. Necrons are very hard to kill and can be reassambled to work again (although the consciousness might be gone if it was there before). Trazyn also has the ability to jump between egoless Necrons and turn them into his own body, which makes him especially hard to kill. He's a collector of artifacts, people, memories and whatever else picks his fancy. He collects them all in a giant museum for when the Necron of the empire he belongs to wake up and can see what happened while they're awake. It's mostly for himself though. He's like a magpie with the British Museum in the size of a planet to his disposal. With a stasis beam he can even keep living beings in his museum. Contrary to other Necrons he's more of a chaotic neutral party in the galaxy. He looks down on the Imperium (love that about him, he tends to drag them to filth), but he might ally with some soldiers or a squad he comes across if it means he gets some artefact he might've been after. He's aeons old, but like an old man and a child in one. He has seen so much and accumulated so much knowledge, but he still gets incredibly excited when he finds something new and even something as "simple" as coffee or music can be fascinating to him. He's kinda like Kenjaku in that way, except he doesn't have some big goal, he just likes watching the universe and only interferes arbitrarily.

Tanau Aleya (Watchers of the Throne novel series)

She belongs to the Anathema Psykana, commonly known as the Sisters of Silence. Her order is made up of women, who don't have souls. They are just void. This absence can make people around them physically ill, make them faint or give them other discomfort. It is also incredibly effective against the forces of chaos, so the Sisters of Silence fight to push back against the Chaos Gods. Thing is, because of their nature they have been neglected a lot and haven't received much attention or support from the Imperium at all. Aleya is especially aware of this and this is part of why she is such a ball of rage. The other reason is that her conclave, all the sisters she knew and grew up with, was destroyed by chaos cultists. She ends up fighting with Imperial armies to avenge her sisters, but she always makes sure to let them know that she does not like them and hasn't forgiven them for not giving a shit about her or her order for the last millennia or so. While the Sister of Silence have sworn to not talk, they do use sign language to communicate. Many people outside the order don't know this sign language though. Aleya personally also has no problem with talking if she needs to, she sometimes does it with her sisters, but usually she just doesn't want to. When the other doesn't know sign language, she often doesn't communicate at all unless it's urgent. Similarly, if someone pisses her off, she decides to just stand next to them unmoving, watch them squirm because of her repulsive aura. It is so rare to read about the Sisters of Silence, much less have them as a protagonist, and Aleya is all I was looking for from them. She hates the Imperium, she hates their cult of worship, she makes sure that she has very high priorities when it comes to who she cares about, she makes a sport out of unsettling politicians and she can crush a skull with her bare hands. What's not to love?

#asks#hope I could somewhat communicate what I like about them and wasn't too rambly...#not that analytical but it's hard to do that with so many different characters#long post

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

im definitely not ripping off my friend by making a list of au ideas i have no siree //gonna slap this under a readmore cause i. well i say a lot. all of the time. i tried so hard to format this Good but tumblr fucked me up i am so sorry

so first-off i know i already have one WIP AU (Auckland) on ao3 so i wont talk about That one cause like. spoilers. i actualyl have it like 80% created so its likely gonna truly get finished for once and i dont wanna ruin shit

the other one ive posted about is something me and ben (catgirlrepublic) have worked on together its not at all close to done or anything but it's. a fun little crossover. Between jdate and my fuckinuhm. Original characters story “Untitled Villains Project”. the sketches of the comic version ive started is actually my pinned post 👉👈 its like the first chunk of the story, i think half of part 1? yea.

Tldr john fucking Somehow is able t oget into contact with a certain curious scientist from another reality who’d just love to study the Soy Sauce, most certainly not for her own nefarious purposes

John and Dave meet up with the scientist, her name is Boss, and her lab assistant, Toxic, and after a bit of a preliminary Vibe Check where john determines her trustworthy (which Dave doesnt agree with,) the two agree to be taken to the world UVP is set in. from there they stay in Boss’s lab (big old fucking abandoned military lab). John and Toxic are fast friends due to mutual love-of-chaos. John n Dave get to fuckin, camp out on an air mattress.

The day after they arrive, the two get split up, not exactly intentionally; big plot points of UVP are liek. Fueled by Boss sending Toxic to go fetch her “research materials,” which are usually important artifacts

Fuckin side note i guess i have to explain my dumb bullshit: Boss’s, uh, field of expertise so to speak is actually fckin, basically the scientific study of magic and superpowers n shit like that. This shit’s all real in that world. Toxic’s got fuckin superpowers, so do 4 other main characters, whatever. It’s got a bit to do with spirituality, iss Boss’s hypothesis. So she has Toxic fetch important artifacts that might have “energies” to them. The thing is actually way more fuckin complictated than that, this is just Boss’s initial hypothesis.

Motherfucking anyways. So Boss gives Toxic a job to do, and John get excited about how Cool that sounds, and ends up going with Toxic, leaving Boss and Dave alone. Neither is thrilled about this. But Dave and Boss get to have a bit of conversation (while Toxic and John are off bonding and having a good time) and come to a… mutual grudging understanding of some kind. They still dont like each other though lmao

Theres gonna be deeper shit going on but we havent sorted it out yet/tbh havent like Written For It in a while but i still like thinking about it a lot lol

Also pretty sure our endgame is john and dave steal toxic and bring them back with em lmao boss is kind of not nice and toxic would most certainly be better off in Undisclosed. Actually theyd fucking love it. Theyd become a local cryptid im sure. Undisclosed’s mothman is a teleporting spike baby.

I have. Another crossover AU that i might. Post something about for halloween? Maybe? If i have it finished?

Crosses over into, you guessed it, another one of my original-character projects. God, am i vain or something?

I promise this is just because i think blue and dave should get to team up to beat up some monsters

Quick briefing on my fuckinuh. Original character story, this one doesnt have a name (yet? Idk lol my work never actually goes anywhere sso who gives a shit). It centers around two grim reapers, Red (26, bi woman) and Blue (22, aroace agender asshole). In this reality or whatever, grim reapers function kind of like low-level office workers. They get told who’s going to die + when by some middle-management types, and upper management only involve themselves when punishment needs to be doled out. These Higher-Ups can be seen as analogous to Korrok; they’re decidedly not human, never were, and fucking terrifyingly powerful. Additionally, grim reapers are sort of .. designed to be “background noise” people. In reality theyre supernatural beings and, uh, look Real Fuckin Weird (the whole deal has a neon aesthetic im terrible at drawing uwu) but most humans just perceive them like extras in a movie. A body’s there but the camera’s not focused on it.

To the narrative: the shit starts when Red n Blue get relocated to Undisclosed. Relocation is something that just happens every now and then to reapers; they usually work in teams, but they get split up into different cities to avoid any strong bonds forming (a counter-union strategy from the Higher-Ups).

Red, Blue, John and Dave end up running into each other for the first time in a McDonalds where John n Dave are getting some 4am “hey, we just survived another horrific monster fight” celebration burgers. John and Dave are the only two people who can see how… strange Red and Blue are. Nobody else notices.

John unintentionally pisses Blue off, leading to Blue whacking him upside the head with a dildo bat. They all four get kicked out of McDonald’s. Dave and Red both are less than thrilled

Blue and John end up resolving their differences, somehow. Red and Dave briefly bond over their dumbass best friends being, well, dumbasses. They all part ways amicably.

somehow-or-other (idk yet) they end up running into each other a few more times, and eventually john invites them over to his place, and the four (plus Amy now!) get to know each other a little better

while there, Blue gets a text about some guy who's gonna die and John offers to drive them to where that's gonna go down. they take him up on the offer and get to have a bit of one-on-one conversation

after that ordeal though Blue has had Enough of people and bails, leaving John to head home alone

theres a sort of mirror-development going on with the five of em. Red, John, and Amy would all like everyone to get along, though theyre a bit tentative about it (John moreso than the other two, actually, jsut cause. well Red n Blue could still be Sauce Monsters). Dave and Blue on the other hand do Not like people enough for this shit, and Dave's not unconvinced theyre Sauce Monsters. he will not trust them until proven he should

the story's kinda nebulous but i got an idea for some Shit going down that involves both Sauce Monsters and also the Higher-Ups to have some fuckin absolute chaos go down.

Oops! All Trans

Everybody is transgender. Everyone

Ive actually workshopped this one both with ben (catgirlrepublic) and ghost (ghost-wannabe) lmao its a fun lil concept ive had from the get-go cause i mean. What’s an internet tran gonna do other than hit all their favourite media with the Everyone’s Trans beam

Dave transitioned post-high school and faked his death for it. People go missing in Undisclosed all the damned time, after all. He moved to the next city over, transitioned fully, then came back as a completely new man. Yes i know this doesnt exactly fit with the “everyone knows David from high school” thing alright, hush.

Anytime anyone brings up John’s old best friend (pre-transition Dave) John throws an entire fit like an overdramatic grieving widow. Full-on sobbing “why would you bring her up?! I miss her so much—” to the point that people just stop bringing up because Jesus Christ That Sure Is Uncomfortable KJHGFDS.

This is a scheme he and Dave came up with prior to Dave leaving, though Dave hadnt exactly anticipated John putting on this much of a performance about it— but it’s stopped Dave from ever having tto hear his deadname again, so hey.

Amy transitioned sometime in middle school/early high school. Her family was super supportive and loved her a ton and most people just know her as Amy. she was super shy her whole life really so. Yeah. people just dont think to bring it up lmao also i Feel Like big jim would absolutely wallop anyone who gave her trouble of any kind

John’s nonbinary (genderfluid specifically) and not exactly Interested in transitioning ? like hes fine with how he is. mostly.

he came out to Dave in high school but hes not out to anyone else exactly. Maybe his bandmates. Probably any other trans person in Undisclosed knows, too, cause theyre safe to tell lmao. Johns mostly a “he/him out of convenience” kinda nb who’s cool with any pronouns but does prefer they/them most. Dave and Amy use they/them when the trio are alone

Also this is a totally self-indulgent caveat that i think would be great, Dave’s actually agender but because he's transmasc and transitioned when he thought there were really only two options, and being Boy at least felt less weird than being Girl, he just kind of assumed he was a dude. It’s only through a lot of (like fucking years and years hes probably in his 30s/40s when he puts 2 and 2 together on this one) talks about gender with John that he realizes he actually feels like No Gender. Masc aesthetic with none gender.

I Just Think It’d Be Neat Is All Okay

Also Amy came out to Dave about being trans early on in them seeing each other and his response was to get very nervous before blurting out “me too” and then just being too embarrassed to talk about it for the rest of the day. Hes got a lot of hangups on talking about it actually it takes years for him to get comfortable in that

by contrast when Amy comes out to John about it his response is to yell “EYYY ME TOO” and give her a big ol hug lmao

I think itd be neatt if Amy ran a like. Transfem help/advice blog on tumblr. Kind of helped-with by John who can give her transfem nb insight for certain asks. I also just think that would be neat.

Cowboy AU - i put this one last cause its got drawings to it actually. Theyll be at the bottom

Basically just. Hey you ever watched a western. I think they look neat

This is another one me n ben have come up with lol

The soy sauce and all that shit still exist, im not sure where korrok fits in yet but ill figure it out

Theres no real like solid narrative yet ? but heres the barebones of everybody’s arcs.

John

Johns an absolute troublemaker, Of Course. Hes wanted in several towns for absolutely stupid shit. Hes a loner who shows up, causes chaos, gets drunk, does some drugs, runs away if people get too mad at him

He definitely had the same kind of deal with the soy sauce as in canon— he was at some kind of party, somebody offered it, he took it cause why the fuck wouldnt he, now he can see monsters and shit

Hes kind of a mooch also. Like. dont let him stay in your barn man he’ll never fucking leave and drink all your booze.

He runs into Dave when they happen to just, cross paths in the same town. the bullshit John stirs up ends up involving Dave in a way that makes it seem like it's his fault too, and they both get run out of town

after that he just tags along after Dave. hes decided this guy's Cool he wants to stick around. Dave is pissed at first, but not enough to shoot him or anything, and eventually, John grows on him

Dave

Dave also is a loner but unlike John hes simply so fucking awkward and bad with people. He doesnt feel like he belongs anywhere so he just travels

He’s the stereotypical Lone Ranger tbh. He wanders from town to town, solving their problems, though hed deny its out of any moral obligation (it kinda is, a little bit, tbh. He does like feeling useful). He shows up, fixes things, leaves. He's kind of a legend but most people think he's hiding something dark. other people jsut know him as that guy who farted real loud in the middle of the saloon and promptly skipped town out of sheer embarrassment. you know how it goes with Dave

He ends up involved with the Soy Sauce when a snake (not Actually a snake,) bites him. The snake’s more like the wig-monsters, really. Anyway, it injects him with the soy sauce, he fucking trips balls in the middle of the desert, he can see monsters now

He runs into John and shit goes tits-up, as said, but they become traveling buddies after that. he'd never say so, but he's glad for the company, actually. it's nice. hes not used to companionship but he feels a strange kind of easiness hanging out with John....

not sure how the Monster Dave concept will like fit in to this reality but like. trust me i want it in here. I'll Figure It Out.

Amy

Amy’s been living in a town John and Dave end up passing through and she is very curious about these two new Handsome Strangers who claim to fight monsters and just kinda. Persistently tags along til they let her join for real

Her family’s all dead, unfortunately, just like in canon, and she’s been living alone for a few years before meeting John n Dave. she had nothing left in that town to stay for, she'd been fantasizing about escaping on wild adventures for a long time and this felt a little like a dream come true. (Dave still gives her a spiel about how Difficult it is, but really, her fantasies were pretty grounded-in-reality already. i jsut think thats how she is, yknow?)

Shes the first person to react to the whole “we see monsters” shit with a kind of “oh, okay. neat” kind of response lmao

John and Dave fix whatever the fuck is up with her town (maybe that’s where the Korrok shit can fit, who knows) and Amy ends up being integral to that. After, she insists they take her with them because “they need her now” and Dave just cant really say no. John too is very much "the more the merrier!" and hes actually glad to have another person along he loves people lmao

At the start she has long hair but after she joins them she chops it short with a knife for convenience

also she still is an amputee. justt. idk. it was a wagon/stagecoach accident rather than a car accident lmao. just to clarify since i hadnt mentioned it, i wouldnt rob her of her ghost hand or yknow. all of the significance to her character that Missing A Hand has. although also now im going to have to research what was used as painkillers way-back-when, but im betting shes still got, like, her pain pills, they probably had those, maybe i wouldnt have to try too hard there. old timey medicine could be WACK though,

Shitload

Yeah hes in tthis shit mostly cause i liked designing his cowboy self lmao

Hes a kid (like 16, 17, technically i think in those days that was more Young Man than Kid but whatever. Hes Young i mean.) who got possessed by the Worms out in the desert and, by his family’s perception, just went missing!

Hes also a wanderer, but he ended up at the same town john and dave met in, at that same time, and starts following them after, already aware of who/what they are.

He keeps his face covered 24/7. actually he covers a Majority of his self for reasons. kinda want him to be a slightly more horrifying Worm Entity rather than human idk,

I kinda dont have much for this boy yet sorry Shitload

images !

with some editing notes for me cause im doing a very specific aesthetic with this lmao. i might change some lil details/colours though ...... idk

im also kinda 🤔 about shitload's colour palette. i want things assoicated w the sauce to be black'n'red predominantly but i think his palette might mirror dave's too closely. also im working on a korrok design i jsut am too busy to draw it now

#jdate#john dies at the end#aus#erh. tthe hell do i tag this as#rambles.txt#long post#well let me know if youd wanna hear more or. or something#send an ask. or whatever#yaknow#:jazz hands:

6 notes

·

View notes

Note

Do you have any comic book recs that are short? Like one-shots or mini series?

YESSSSSSS!!!! so many!!!

here’s a list of some personal favorite mini/maxi series of mine (with links!)

MINI-SERIES:

dark knights: death metal robin king (1 issue)

background knowledge required: middling. this takes place in the death metal storyline, so it’s nice to know what’s going on. but honestly, robin king’s story operates on its own pretty well as a glimpse into bruce waynes that could have been (and are!). i love robin king i think he’s adorable. tw for gore though.

nubia: real one (graphic novel)

background knowledge required: none. nubia’s backstory and connection to wondy is given and explained. HEAVY tw for police brutality, racism, school shootings, sexual harassment and the like. nubia: real one is written by a black woman and as such handles the topics fairly well, but it can still be upsetting.

year one: batman/scarecrow (2 issues)

background knowledge required: none! dive right in. gives us jon’s backstory and, provided you know who batman is, you get the gist real quick. great read, great art, great time.

timber wolf (5 issues)

background knowledge required: not much! this was my first brin comic. easy and quick. features one of lobo’s bastard sons, thrust! funny antics ensue. good story, good characters, some wacky coloring mistakes.

event leviathan (6 issues)

background knowledge required: some. you should probably know who the characters are, but other than that, it’s pretty easy. not a huge fan of b and jason’s characterizations here, but plas is in it (huge thumbs up) and he’s very weirdly homoerotic with the question.

plastic man 2018 (6 issues)

background knowledge required: none! jump right in! you see eel’s backstory, the villains are self explanatory, it’s a great characterization and a great read. has a canon trans character (two, if you count eel!) and is wonderfully written.

collapser (6 issues)

background knowledge required: absolutely none. this is a free floating comic. fun art, fun characters, fun story.

eternity girl (6 issues)

background knowledge required: like collapser, absolutely none. this series stands alone. heavy tw for suicide and self harm. it’s a heavy story but it’s really amazing. definitely worth a read.

MAXI-SERIES

black canary 2015 (12 issues)

gonna be honest, been too long for me to remember much about this comic, but the art is fuckin gorgeous.

metal men 2019 (12 issues)

background knowledge required: not too much. happens during death metal, so there’s alternate universe shenanigans. overall, just a fun read if you wanna watch a very sad scientist get even sadder.

doom patrol 2016 (12 issues)

background knowledge required: sssssome, but it’s nowhere near necessary. you can get a handle on the characters pretty quick, even if i would recommend reading morrison patrol first. fun read, fun characters, fun ending. followed by doom patrol: weight of the worlds, a 7 issue series of one-shots focusing on alternate universe versions of the doom patrol.

shade the changing girl (12 issues)

background knowledge required: some, but it’s not necessary. basically, she’s the successor to shade the changing man, but you get the gist of her whole deal pretty quickly, and reading his comics isn’t essential. he does appear in this series and his characterization isn’t... great.... but. if you’re just reading for loma, go for it. followed by shade the changing woman (6 issues).

dc/young animal: milk wars (graphic novel)

background knowledge required: read doom patrol 2016, shade the changing girl, aaaaand probably eternity girl first. the rest is pretty self explanatory and honestly if you wanna jump right in and see batman as a priest, i don’t blame you. it’s cool and really fucking weird. but it’s super fun! you should read milk wars!

hope this helped you find something good to read!!! much love

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

100 Humans on Netflix

So there’s this neat Netflix Original show called 100 Humans. I immediately got interested in it because they take this group of various humans from different backgrounds, age groups, and so on, and they use them to conduct experiments to get answers to interesting questions.

So, right away I had concerns about this show because

If you know anything about data and statistical research, you know 100 people is a very small sample size and does not breed accurate results

However, I’m very curious and wanted to see what they came up with anyway. I watched all 8 episodes and, honestly, I enjoyed watching it for the most part. However, I have a LOT of issues with the show and how it was conducted and I want to list them out here.

If you’re interested in watching 100 Humans or have already watched it, please consider the following before taking any of the show’s data as fact.

100 people is a very small sample size. This is because, the more people you have, the more weight each increment in your percentages has. With 100 people, each person represents 1 entire percent. That’s a lot. That means even a few people giving incorrect answers, having off-days, or giving ridiculous results (such as you can see in the spiders georg meme), can sway the entire result of an experiment into unreasonable territory. This is why most scientific studies attempt to get data from many hundreds or even thousands of people. The bigger the sample size, the more accurate it is to the entirety of the world.

I’ll put the rest under the cut because it gets long

The 3 hosts, who I’ll refer to as the scientists (regardless of if they actually are, because I’m not sure and don’t feel like googling it) repeatedly make false statements. For example, in one episode, they told their humans to “raise your hand if you believe you’re less bigoted than the average person here,” to which 94 people raised their hands. One of the scientists then made the statement, “If that were true, it would mean only 6% of Americans are bigoted.” This statement is entirely false. The only way to actually determine a true meaning to that would be to determine at what percentage of bigotry you are considered a real bigot. You also must consider that believing you’re more bigoted than other people in a small group, who you already have an impression of, is not necessarily indicative of how you feel you measure up to America as a whole. Anyway, I could go on and on. The only way to accurately summarize the results of that question would be to say that 44% of the humans had an inflated sense of righteousness or something of the sort.

The 3 scientists, both in person and in narration, for the sake of entertainment (if that’s what you call it) continually made “jokes” that poked fun at different groups, implied men are shit, etc. Maybe that’s fun for some people, but the kind of jokes they were making to amp up the hilarity of their host personas was genuinely just uncomfortable and made me feel even more like they couldn’t be trusted to go about unbiased research.

The scientists continually drew conclusions where the results should have been labeled inconclusive

The scientists made blanket statements about certain groups based on 1 element of research that would not stand up to further evaluation. For example, when explaining that ~93% (i think it was about that number) of Americans have access to clean, drinkable, tap water and yet some large number of single use bottled waters are sold every year, one scientist said it was because people believe bottled water is safer and cleaner than tap water. I am going to do my next survey on this to see if my own perception is flawed, but I simply don’t believe that all of the people who buy bottled water do so because they think its cleaner than “tap” (as if all tap is the same.) I know there have been studies about people drinking unlabeled bottled water and tap water and not being able to tell the difference, but this neglects to account for the fact that different houses pipes can affect the taste of the tap water running through them, people can use disposable bottles of water for certain activities or events too far away from tap for people to refill their reusable bottles easily, and so so so much more. Anyway, it just really bothers me to see “scientists” making these kinds of generalizations when they’re the ones whose results we’re supposed to trust.

The show was incredibly cisnormative. There was an entire episode based on comparing men and women that made me extremely uncomfortable with its division of people by men and women. There was the implication that all men have penises and all women have vaginas. There were implications that reproduction is a necessity in picking a partner. It was just a shitshow. There was one comment by one subject who asked, when being told to separate by men and women, “What if I’m transgender?” Obviously I can’t say for sure, but this person didn’t appear to be transgender and the sort of tone it was asked in makes me think it was literally something they asked him to say in order to get inclusivity points with the viewers and to “prove” that they’re not transphobic by having them divide up, because they said to go to the side you identify with.

This whole thing is a) harmful to nb folks who would not have had a side to go to and b) completely negating the fact that the way we were socialized can have an effect on our social responses. That means that for a social experiment, a trans person could sway the results of one side due to their upbringing and the pressures society put on them before/if they don’t pass. This is all assuming they had any trans people there, which is potentially debatable.

I also take issue with this entire fucking episode because just, the amount of toxicity in proving one sex is better than the others is really gross and actually counterproductive to everything feminist and progressive. Not to mention, them implying that they’re trying to support trans people only to reinforce the notion that a trans man is inherently lesser for being a man when even prior to hatching, he would have also been force fed propaganda and societal pressure implying he’s less than for supposedly being a woman is really gross and makes me angry. The point of what I’m saying is that it’s actually not woke to hate men as a way of bringing women up because there are men who are minorities who are being hurt by the rise of aggression being directed at them for their gender. Anyway enough about that.

The tests drew false conclusions because they did not account for how minorities adapt to a world that’s not made for them. This is specifically directed at the episode where subjects were asked to match up 6 people into couples. There were 3 women and 3 men and the humans were asked to put them together into pairs. they could ask the people 1 question each but then had to match them up with only that information.

The truth is, the people brought in were 3 real life couples already, which the humans didn’t know until after they matched them. The couples were m/f, m/m, and f/f. I think that’s great, but the problem is, literally none of the humans asked any of them their sexuality as their question and most people didn’t even consider they could match up same-sex people. One girl even thought that they had told her to make m/f pairings, even though they didn’t.

The scientists concluded from the experiment that the humans have a societal bias toward people, and assume they’re all straight, even if they, themselves, are not straight. I personally believe that was the wrong conclusion to draw. You could see some of the queer humans were shocked that they hadn’t considered some of the pairings might be gay. But, I don’t think it’s because they believe everyone they meet is straight, I believe this says more about what they expected from the scientists themselves.

If someone is in a minority and they go to do something organized, like a set of experiments, they are going to be judging the quality and setup of the experiments by those designing them. I feel that the lack of consideration that the couples might be gay has a lot more to do with queer people having adapted to a world where queers are rarely involved or included in equal volume to the cishets. The queer humans taking part in the experiment and failing to guess gay couples shows that they have adapted to a world where they are excluded rather than a belief that every random person that they meet is straight.

My point is further supported by an expert they had on the show who explained that, statistically, it was entirely likely that they were all straight and that even queers will account for being minorities by going with what’s most likely. The truth is, we are surrounded by a whole lot of straight people. It makes sense to assume only 6 people are all straight and that, if any aren’t, they may be bi.

The scientists frequently broke an already small sample size into even smaller groups. The group was very frequently broken in half, in thirds, or into sets of 10 people. These sample sizes tell us almost nothing actually conclusive.

The experiments/tests frequently were affected by peoples abilities, unrelated to what was being tested. For example, one test that was broken down into 6 people and 6 control people competing at jenga was meant to show whether needing to pee helps or hurts your focus. first of all, sample sizes of 6 are a fucking joke. Second, this completely ignores these 6 people’s actual ability to play Jenga. If someone sucks at jenga with or without needing to pee, them losing Jenga when they need to pee says exactly fuck all about whether needing to pee affected their focus. They should have tested people’s Jenga skills beforehand, counted the amount of moves they made before the tower fell, and then did it again after hours of not peeing to compare their results. This test made no logical sense at all.

The scientists ignored the social effect of subjects knowing each other as well as duration of events during their last experiment. They were testing to see if people with last names near the end of the alphabet get a shittier deal because they go last in everything where things are done by name order. They tested this by doing a fake awards ceremony where they gave out some 30 awards to people, gauging the applause to see whether the people at the end got less hype and therefore felt worse about themselves than those in the beginning who got the fresh enthusiasm of the audience.

the results showed that the applause remained fairly consistent throughout the awards. The issues with this test are numerous, but here are the three I take most issue with.

1) the people here all got to know each other very well over the week it took to make the show. People who know each other and have become friends are much more likely to cheer for each other with enthusiasm, regardless of how long it’s been. On the other hand, polite applause from a crowd at, say, a graduation, where you are applauding people you don’t know, WILL start off more raucous and grow very quiet except for individual families near the end.

2) the duration of the test was a half hour, which is not very long at all and doesn’t say much to test the limits of enthusiasm. Try testing the audience at a graduation with a couple hundred graduates that also involves the time it takes to walk all the way up to a stage a hundred feet away, accept a diploma, and then wait for the next person. These kinds of events take hours and nobody keeps up their enthusiasm that long unless they’re rooting for someone in particular.

3) this study tested only one of many many ways name order affects a person. Cheering and applause is only one factor. It does not take into account people having their resumes looked at in alphabetical order and therefore people at the beginning of the alphabet being picked before anyone ever looks at a W name’s resume. It doesn’t take into account a small child’s show and tell day being at the very end of the school year, after 6 other people have brought in the same thing they planned to. No one cares about their really cool trinket because they’ve seen a bunch like it already. This test doesn’t take into account how many end-of-the-alphabet people just get straight up told, “we ran out of time. maybe next time,” when next time doesn’t really exist. I feel genuinely bad for the girl who suggested this experiment because the scientists straight up said something akin to, “lmao her theory was bs ig /shrug” even though it was their own shitty research abilities that led to their results.

They did one experiment intending to see how many people have what it takes to be a “hero.” The request for this test was made by someone curious about the effect of adrenaline and if it really works how some people say. The scientists thought it an adequate method to determine an answer by testing their reflexes with a weird crying baby sound and then dropping a doll from above while they were distracted with answering questions. The scientists looked up before the doll dropped to indicate a direction of attention. While this does give some answers about peoples intuition, reflexes, and ability to use context clues, its entirely an unusual situation, makes no sense in reality, fails to take adrenaline into consideration literally at all, and has a lot more to do with chance. The person dropping the doll literally couldn’t even drop it in the same place from person to person. Some got it dropped into their lap and others almost out of arm’s reach. This, like a few of the other mentioned experiments, was during the last episode, which felt lazy and thrown together last minute, with very little scientific basis to any of the results. The last episode was weak and disappointing overall.

One of the big issues I have with this show is actually their repeated use of the same group. They said at the end that they had done over 40 tests. Part of doing studies is getting varied samples of people in order to get more widespread results. Using the same 100 or less people (already a tiny sample) repeatedly is a terrible research method. You’re no longer studying humans at large. You’re studying these specific humans. You can’t take the same group with the same set of inadequacies, the same set of skills, and the same set of biases and then study them extensively and in many different ways like this. Your results are inherently skewed toward these specific people and their abilities. I expected them to at least get a new group each episode - every 5 or so studies - but no. They keep the same group all week, which makes the entire season. This is inexcusable in research imo.

The next issue is contestant familiarity. The humans all getting to know each other is great, socially, but it also destroys the legitimacy of many of the studies that involve working together or comparing yourselves and your beliefs

Many tests had issues with subject dependency. One study, meant to compare age groups and their ability to work together to complete the task of putting together a piece of ready to assemble furniture had each group with members they relied on entirely. A few people built the furniture while one person sat across the room, looking at instructions with their back to the others. They had to relay the instructions through a walkie talkie to another contestant and that other contestant had to relay it to the people they’re watching build the chair. You cannot study a group’s ability to build something with instructions by the ability of one single person to communicate. You’re testing that individual and the rest of them on two completely different capabilities. One person fails at being able to communicate and everyone else becomes unable to build the furniture. Even if everyone else in the group is more effective than all the other groups at building ready to assemble furniture, they might end up falling in last because of their shitty communicator who is literally not able to convey simple instructions. (yes, this actually happened in the test)

One test judged the subjects at their speed of getting ready, to see if men or women are faster at getting ready. While most elements of this test were just fine, the part I took issue with was that they did this test without regard to social convention. They told the subjects they were going on a field trip and to get ready by a certain time. Then, they gave them many things to get distracted by, like refreshments to pack with them, a menu to preorder lunch from, and so on.

The part that upsets me about this test is that they ignored social convention entirely, to the point that subjects were judged based on their conventional actions and expectations more than their actual speed at getting ready. The buses promptly shut their doors and left at the time they were supposed to but there was no final call to get on the buses. In general, when a group is to be taken somewhere by bus, there will be an announcement to load up and leave. You could clearly see many of the subjects were ready to go and were just standing around talking while they waited for fellow subjects to finish getting ready. I have no doubt that, if given a final call, most of them would have loaded up within a couple minutes. However, they were relying on the social convention of announcing departure and were therefore, left behind entirely (for a nonexistent field trip). These people who were left behind were counted as being late and not making the time cutoff.

If one were to look at the social element of this situation, if everyone there believed there would be a warning before departure, the fact that 24 to 14 women to men were loaded onto the buses at departure doesn’t necessarily indicate the women were faster to get ready. It seems to me that it’s more likely to indicate anxiety at being late and a belief that they need not impede on anything lest they be reprimanded or have social consequences for taking too long - something women are frequently bullied for. There’s also the chance that many who boarded without final call are more introverted or antisocial. Plus, we can’t forget to include the people who have anxiety about seating. If someone is overweight, has joint pain, or has social anxiety, they will be more likely to board early to get a seat they feel comfortable in.

If they had counted up all of the people socializing and waiting on the sidewalks nearby, they may have found that there were more men who were ready to board up at a moment’s notice. I’m not saying I think men are faster to get ready, I’m just saying that we can’t know based on who boarded without a final call. If people believe they will have a last minute chance to board, a large number of them will take the last few minutes to socialize with their new friends until they’re told they have to board. Therefore, this test cannot be considered conclusive without counting and including the people who were ready and not boarded as a third subset.

Honestly, I could go on and on about how sensationalist and unscientific this show is, but I just don’t have 6 more hours to contribute to digging up every single flaw with it. There’s A Lot.

My point is, if you feel like watching this show, which I don’t necessarily discourage inherently, I just beg you to go into it with a critical eye. Enjoy the fun of it and the social aspects, but please don’t rely on the information provided and please don’t spread it as fact, because it’s not.

It’s entertainment, not science.

#100 humans#netflix#tv#show#science#scientific research#research#studies#study#studyblr#statistics#stats#sociology#data#netflix original#analysis#review#netflix review#show review#tv review#ghostpost#logical fallacy#logic#correlation#causation

10 notes

·

View notes

Note

Do you have any podcast recommendations? I've listened to tma, wolf359, the penumbra podcast, and like...half of night vale. You seem like you'd know some good ones!

!!!

I Am In Eskew is an absolute all-time favorite of mine! It’s very firmly horror, but not tragedy. Think… WTNV but 1. on a personal scale, 2. actually terrifying, and 3. not benign. It follows David Ward, inhabitant of the city Eskew, as he chronicles some of the terrifying stuff that happens to him. Eventually, we hear from Riyo Dulae, a private investigator who’s been pulled into Eskew’s orbit. It uses place-as-horror in an astonishing way! It’s a finished product with 30 episodes and the ending is honestly amazing. I’ve listened to it several times. It’s very good. Listen to it. Please.

This got long, so the rest of the recommendations are under the cut, and in no particular order! (Eskew is absolutely my top recommendation lol) Particularly sad endings and ongoing series are specified.

Janus Descending is a finished and relatively short sci-fi horror series. It follows two xenoarcheologists (archeologists for aliens) as they inspect the site of an abandoned alien civilization. It’s told in inverse chronological order, alternating between Chel and Peter’s perspectives. Chel’s is chronological, while Peter’s is backwards. It’s an amazing format and keeps you suspended in the mystery up until the very end! It is a tragedy, though, and has a sad ending.

ars PARADOXICA is an audio drama about time-travel and the Cold War. The synopsis is this: scientist Sally Grissom accidentally creates time travel, is transported back to the Cold War, and is entwined with a clandestine branch of the US government. It’s 3 seasons long- and I will say that if you’re not good with differentiating voices I recommend either listening to it without stopping for a long period and/or reading along to transcripts. The plot is intricate but engaging and the large cast of characters each has their own unique personality. Plus: canon ace main character (as in she says she’s asexual! in canon!), a Jewish lesbian semi-main character, a mlm (bi?) man of color side-character, and several other characters of color.

Mabel is an ongoing horror podcast with elements of fae/fairy lore and the place-as-horror theme. It’s not as outright horror as TMA, Eskew, or Janus Descending, it’s much more atmospheric? It’s several seasons in, with the next season currently in production. It follows Anna Limon, who is an in-home caretaker, trying to contact Mabel Martin, the granddaughter of the woman Anna is caring for. It has lots of wlw, lots of moral ambiguity, beautiful prose, and lots and lots of fae.

Zero Hours is a 7 episode long anthology series by the creators of Wolf 359. Each episode deals with “the end of the world - or at least something that feels like the end of the world.” There’s 99-year intervals between episode and it starts in the past and ends in the far future. It’s honestly stunning and was well worth listening to in it’s entirety when it dropped (and subsequently staying up past midnight).

The Bright Sessions is… kinda urban fantasy? The official synopsis is that TBS is a “science fiction podcast that follows a group of therapy patients. But these are not your typical patients - each has a unique supernatural ability. The show documents their struggles and discoveries as well as the motivations of their mysterious therapist, Dr. Bright.” (I tried explaining but was having a tricky time) The characters are amazingly written and unique. (And no, it doesn’t fall into the “evil therapist” idea, in case you were worried) One of the main characters is gay (and it isn’t a throwaway line). It has good and realistic representation of mental illnesses: a main character as a panic/anxiety disorder, another has PTSD, another has depression, and so on. The main show is finished but there’s a spin off that’s being made. Specifically happy ending!

Alice Isn’t Dead is a horror podcast by the creators of Night Vale. It follows Keisha, a trucker, who is looking for her wife, Alice. Keisha encounters many strange things as she drives back and forth across America, including murderous almost-human monsters, places that are stuck out of time, and a nation spanning conspiracy. It encompasses the whole… atmosphere of middle-of-nowhere America perfectly. It’s a complete story with a novel form (haven’t had the pleasure of reading it, though). Main character is wlw, and Alice is not dead.

Limetown is a horror podcast. It follows reporter Lia Haddock as she investigates the mystery of Limetown- a town in Tennessee where over 300 people disappeared overnight, never to be heard from again. It’s finished…? I think the podcast is finished but a book and a Facebook miniseries are in development? Anyways. Sad ending. I loved the first season a lot, the second season is good too though!

The Adventure Zone isn’t an audio drama, instead it’s an actual-play show of Dungeons and Dragons (and D&D like systems). The McElroy brothers and their dad host it, and are frankly absolutely hilarious. TAZ: Balance is the first season and starts as a classic d&d game but turns into an amazing and heart wrenching story with beautiful prose and music. And also 69 jokes. TAZ:B is honestly one of the most emotionally impacting stories I’ve ever heard. It has an amazingly happy and hopeful ending. Includes: casual lgbt rep and a late game but major character is a trans woman! I’ve heard good things about the recently finished season TAZ: Amnesty, although I haven’t finished it. There’s a new season, TAZ: Graduation, that started recently, and I’ve enjoyed the handful of episodes I’ve listened to! Currently ongoing, but tragic endings aren’t something that’s expected.

I haven’t finished/caught up with these, but I’ve enjoyed them: Sayer (sci-fi. think menacing capitalist Night Vale in space, heard s3/s4 are really good), The Bridge (horror, alternate modern day. follows a watchpost on a bridge that crosses the Atlantic), The Orbiting Human Circus (from the people at WTNV. surreal fiction. hard to explain). I feel like there’s more but I can’t remember any atm.

I’m also gonna point you towards @theradioghost‘s blog and her podcast recs tag. Her taste is amazing and I haven’t disliked a single show I’ve tried. (Also, check out her show, Midnight Radio! It’s the next thing on my to-listen list.)

82 notes

·

View notes

Text

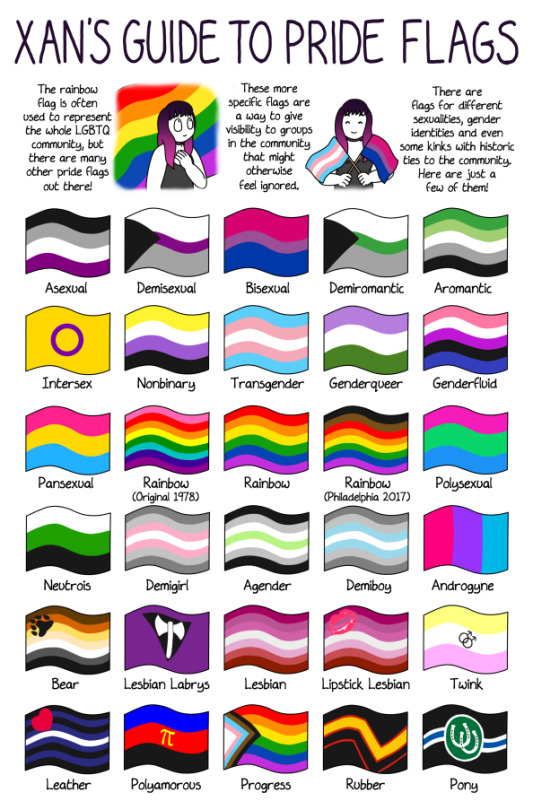

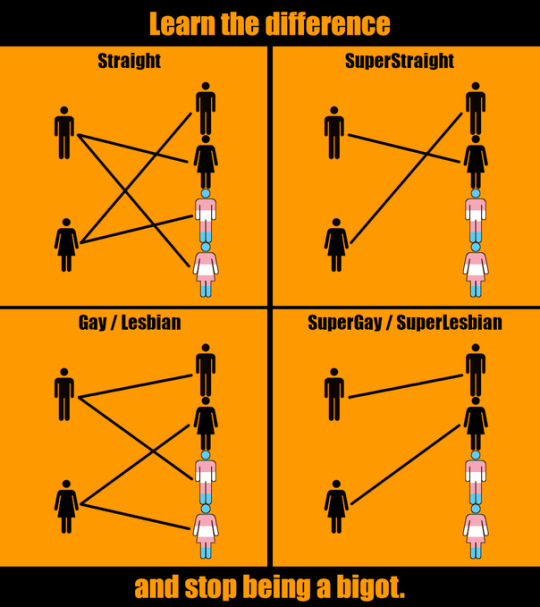

SuperStraight

A brand new sexuality that is trending on twitter and being super popular.

Definition:

A superstraight person is someone attracted to members of the opposite gender who are not transexual.

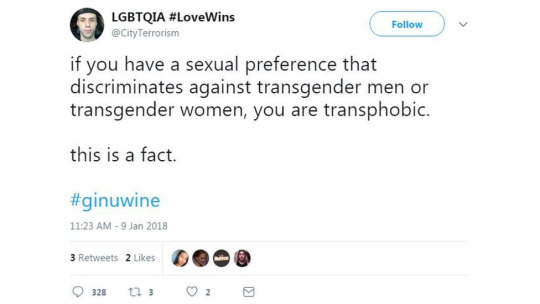

This was created as a response to people who sometimes say things like this:

(source:BBC)

Let’s give a name to the people who insist that not being attracted to trans people makes you transphobic, since I’m not about to describe them every time i wanna bring them up, I’ll call them trans-incels because just like incels they resent people for not wanting to have sex with them.

It’s worth it to remember that trans-incels aren’t representative of all trans people. or even of a majority of them, if i were to bet, they are about as popular as actual incels.

In all the comment sections I checked the anti trans-incel side was a clear majority, and having searched for “superstraight” on youtube to see what people have to say, the first video on the list, from a trans man, is definetely anti trans-incel .

> If you don’t want to date a trans person that’s fine, and if somebody is trying to force you they’re just an asshole

-probably most trans people

From the perspective of a trans-incel (and how we’re all assuming too much)

Imagine a person.

Imagine the probability that they are racist.

Imagine that same person saying “i wouldn’t date a black person”

Has the probability increased at all? be honest, it hasn’t gone up to 100% (which would be the race-incel response) but it must have gone up by at least a little.

But why did it go up by a little? Because now the chance they’ll say something like “because blacks disgust me” has also gone up.

Now imagine being into internet drama (ew) and as a trans person, you’re especially interested in people being transphobic and you probably see transphobia every day because people like talking about it as much as anti-sjw(tm) people like to talk about the trans-incels.

If discussions about trans people only gets to you when it causes drama you’ll probably never see “i wouldn’t date trans men/women...” without having it be followed by “...because they’re not real men/women”.

And even though the whole point of being superstraight is to explain why people wouldn’t date trans men/women without calling them ‘not real men/women’ lets see what the original guy who started the whole superstraight meme has to say at second 15.

https://youtu.be/z8vQhkPnEE4

It’s like instead of throwing bait, they’re just throwing food.

The more you see “...because they’re not real men/women” the more likely you are to expect it, and as someone who subscribes to people posting drama 24/7 you’ll see that hundreds of times until you end up answering ...

the probability that the person who says ‘i wouldn’t date trans men/women’ to be transphobic is 100%

...and even if they don’t follow up with something transphobic it’s always easier to imagine they’re just hiding it rather than to change your whole worldview on the spot.

And if you think “why do they even predict transphobia before its spoken”, well, this might sound crazy to you, but everyone is assuming things all the time, our whole perception of reality is nothing but a hallucination that our brain comes up with using not only stimulus from the world but also assumptions.

There’s a blind spot on each 1 of your eyes, your brain simply fills it in without you knowing, it also adds color to the edge of your vision and makes the whole thing less blurry.

When someone says “i won’t date trans people” some people will simply fill in the blanks, they’ll assume every bit of info about who you are what you believe in what your personality is from just a sentence, because the brain is literally designed for it.

IQ tests are just patterns where a spot is blanked out and you’re supposed to fill it in, your intelligence is measured by your ability to fill in the blanks, and low intelligence people will just make mistakes more often, but everyone smart or dumb will constantly make assumptions about everything, and dumb people will be proven wrong about their assumptions more often.

And this happens all the time even when you’re not talking about politics or having a fight.

Someone talking about the earth being curved? well, every time I saw someone do that they called it a sphere so let me just fill in the blanks.

Someone saying they wouldn’t date trans women? well, every time I see screenshots of people saying that in my drama facebook group i see them being transphobic, so let me just fill in the blanks

That’s just how incels operate.

Building legitimacy

Have you ever noticed that every sexual preference eventually gets assigned a flag, on that note, why does every country have a flag?

If you ask a regular person to guess why their country has a flag you’ll get something related to aesthetics, our flags represent our country.

For example Romania and Hungary:

In school we are taught that each colour on our flag has a different meaning, I searched on google and everyone disagrees on what they mean but as an example.

Liberty (sky-blue), Justice (field yellow), Fraternity (blood red)

Outside of school I was taught by my grandma that the Hungarian flag, much like the Romanian flag, also has a meaning.

The green represents a wide field of green grass, the white represents a white dog playing on the field of grass, rolling around on his back, and the red represents his red dog cock.

Both of these meanings are pretty much just something that a Romanian randomly came up with so i don’t think most people know why countries have flags.

Flags originate from war, that way the armies know not to attack their own allies when they see they carry the same flag, having an army grants you true legitimacy because you can just beat people up into believing you’re legitimate, so countries with no armies probably still had flags because it would be really hard to pretend you have an army otherwise.

Nowadays every country has a flag even if war is illegal, simply because every country has been using one for so long that it became convention. If you don’t follow convention you will be seen as illegitimate. It’s an unwritten rule, but a rule nonetheless, that you need a flag, and much like not following written rules makes you illegitimate (and illegal) so does not following unwritten rules.

And sexualities having their own flags and names probably feels like an even stronger convention than countries having flags for some people.

It’s very often brought up that you have to feel “valid” (which more or less means “legitimate”)

I still don’t know why, but it’s apparent that people need to be reassured that their sexuality is “valid” and then there’s also this:

Why does a sexual preference have to be distinct from a sexuality? I don’t know, but I’m pretty sure the only difference between the two is legitimacy, to confirm to the conventions of flags and labels.

Q: So why do superstraights get a label and a flag and copy everything that LGBT people do, like tweets talking about how valid their followers are or using the word bigot etc

A: Because to get true legitimacy you need to copy the conventions.

The cargo cult

(wikipedia) Some primitive tribes of people would look at colonists from the civilised world and notice that after they’d built some plane lanes, the planes would come bringing cargo full of valuable stuff.

The tribesmen have made the observation that planes land if you build lanes for them to land on, they made the hypothesis that building the lanes causes the planes to come, and like scientists, they set out to test it.

They made lanes, they made fake planes, they tried to copy everything that the colonists did hoping it would be enough.

Superstraight is a lot like a cargo cult of sexualities, they have a flag, they have a label, they call everyone bigots all the time.

This is the first pic I sent before cropping it.

Because, like a cargo cultist who does not see the plane factories from the colonists homelands, the superstraight person does not see the LGBT community from outside his filter bubble, the filter bubble where only the most obnoxious people like the trans-incels can get through.

So when the superstraight person who thinks every LGBT person is just an obnoxious incel tries to “fit in” with the LGBT, they will act like an obnoxious incel, and when everyone is angry at him, he thinks to himself “they've all proven themselves hypocrites! i baited them so hard! i won!!!”

Even tho there’s a bunch of LGBT people from the comment sections I read who don’t even know the trans-incels even exist, because their filters simply don’t show them the same things you superstraight people are shown.

It gets worse

There’s some people who are so cocky and think they’re so much smarter than the LGBT community that they can just sneak in the nazi SS symbol into their flag and not just fuck up the bait completely.

hehe Schutzstaffel fla- wait! you cant call me a nazi! this is just another sexuality you hypocriteeeee

But this is also just a minority of the people who get superstraight trending, its so popular that I’m pretty sure most of the people getting it to trend are actual normies who wouldn’t even recognise the SS symbol and who have never been to 4chan.

Speaking of 4chan

Of course people don’t think superstraight is legitimate when you have 4chan taking credit for it.

They pick up on all the superficial customs like the flag the label the speech patterns and think “this is their, logic, im using it against them, and they’re all mad because of this alone and not just because a we’re comparing ourselves to the Schutzstaffel”

In a turing test a computer attempts to pass as a human.

In the ideological turing test a human tries to pass as someone of a different ideology.

Are people afraid of passing the ideological turing test? do they think if they can think like the enemy, then they’ll become the enemy? there was no need for people on 4chan to talk so openly about superstraight being a ruse, there was no need to make nazi memes with it, there is no need to post “we used their logic against them”, to constantly tell “yes this is all a lie”.