#but in the Iliad he works against her which she takes very personally

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

#in other sources Ares is a total mama’s boy doing her bidding and tormenting the ppl she hates#but in the Iliad he works against her which she takes very personally#did they have a better relationship once upon a time?#greek mythology#greek pantheon#ancient greek mythology#greek goddess#hera goddess#hera deity#hera#zeus#hera greek mythology#hera x zeus#ares greek mythology#ares deity#ares greek god#ares#ares god of war#hera children#goddess hera

348 notes

·

View notes

Text

THOUGHTS ON: ARIADNE and ELEKRA

So I've reentered my Greek myth phase and I just want to talk about these two books for just a second!

First off, look how beautiful the covers are! And second, out of all these authors who've been retelling the Greek myths, Jennifer Saint is definitely one of my favorites! Something I've always hated about a lot of retellings (even with ones I've liked) is how characters are brought down in order to elevate the likability of another, even if that character has had no basis of being petty or cruel previously. And honestly, I probably wouldn't find it nearly as irritating as I do now if it weren't done with the same characters over and over again, with many of these stories having absolutely nothing new to say! Because then it just feels less like the author is trying to be revolutionary and more like they're just following a trend. And where's the challenge in that?

Enter Ariadne, a story all about challenging perspectives, about how appearances can be deceiving, even those made by the decent ones. Of course, you have Theseus with his abandonment of Ariadne after building himself up to be the greatest hero since Heracles, but later on, you also get Perseus; whom Ariadne comes to despise both because of his beheading of Medusa and because of his refusal to let his people worship Dionysus... until she actually meets the guy and finds that not only is he actually really nice and in a very complicated situation, but she herself even acknowledges that her perception of heroes may have been warped because of what Theseus had done to her, all while still having Perseus as an enemy.

As for Elektra, I actually liked it more than I did Ariadne, but also didn't, if that makes sense. So take Helen for example. How many times have we seen her as either vapid or selfish, someone who doesn't care that lives were lost in her name? Well, in this book... I wish we could say we get the opposite of that, but the thing is, this portrayal of Helen has very little personality to even speak of other than being nice! Seriously, even what led her to run away with Paris is treated with complete ambiguity! Like, I prefer it to her being demonized (Atwood, Miller to an extent) or desperately longing for freedom to the point of selfishness (Gill, Heywood), but that's not really saying much, is it?

Compare this to the Epic Cycle, where we get scenes like this:

Then Iris went as messenger to white-armed Helen, in the likeness of her husband’s sister, the wife of Antenor’s son, she whom Antenor’s son, lord Helikaon, held—Laodike, most outstanding in beauty of all of Priam’s daughters. She found Helen in her chamber; she was weaving a great cloth, a crimson cloak of double thickness, and was working in the many trials of the Trojan horse-breakers and bronze-clad Achaeans, trials which for her sake they had suffered under the hand of Ares. Standing close, Iris of the swift feet addressed her: “Come this way, dear bride, and see the marvelous deeds of the Trojan horse-breakers and bronze-clad Achaeans, who earlier carried war and all its tears against each other into the plain, in their longing for deadly battle; these men now sit in silence, the war stopped, leaning on their shields, their great spears fixed upright beside them; and Alexandros and Menelaos beloved by Ares are to fight with their great spears on your account; and you will be called wife of that man who is victor.”

So speaking the goddess aroused in Helen’s heart sweet longing for her husband of old, her city and her children.

[...]

“Honored are you to me, dear father-in-law, and revered, and would that evil death had pleased me at that time when I followed your son here, abandoning my marriage chamber and kinsmen, my late-born child, and the lovely companions of my own age. But that did not happen; and so I waste away weeping. [...]”—Homer, Iliad (trans. Caroline Alexander)

And this:

“Come here; Alexandros summons you home; he is there, in his bedroom, on his bed that is inlaid with rings, shining in beauty and raiment—you would not think that he came from fighting a man, but rather that he was going to a dance, or had just left the dance and was reclining.”

So she spoke; and stirred the anger in Helen’s breast. And when she recognized the goddess’ beautiful cheeks and ravishing breasts and gleaming eyes, she stood amazed, and spoke out and addressed her by name:

“Mad one; why do you so desire to seduce me in this way? Will you drive me to some further place among well-settled cities, to Phrygia or lovely Maeonia? Perhaps there too is some mortal man beloved by you—since now Menelaos has vanquished godlike Alexandros and desires that I, loathsome as I am, be taken home. Is it for this reason you stand here now conniving? Go, sit yourself beside him, renounce the haunts of the gods, never turn your feet to Olympus, but suffer for him and tend him forever, until he makes you either his wife, or his girl slave. As for me, I will not go there—it would be shameful—to share the bed of that man. The Trojan women will all blame me afterward; the sufferings I have in my heart are without end.”

Then in anger divine Aphrodite addressed her: “Do not provoke me, wicked girl, lest I drop you in anger, and hate you as much as I now terribly love you, and devise painful hostilities, and you are caught in the middle of both, Trojans and Danaans, and are destroyed by an evil fate.”

So she spoke; and Helen born of Zeus was frightened; and she left, covering herself with her shining white robe, in silence, and escaped notice of the women of Troy; and the divine one led her.

When the women arrived at the splendid house of Alexandros, the handmaids swiftly turned to their work, and she, shining among women, entered into the high-roofed chamber; then laughter-loving Aphrodite, taking a stool for her, placed it opposite Alexandros, the goddess herself carrying it. There Helen took her seat, daughter of Zeus who wields the aegis, and averting her eyes, reviled her husband with her words: “You’re back from war; would that you had died there broken by the stronger man, he who in time past was my husband. Yet before this you used to boast that you were stronger than Menelaos, beloved by Ares, in your courage and strength of hand and skill with spear; go now and challenge Menelaos beloved by Ares, to fight again, face-to-face—but no, I recommend you give it up, and not fight fair-haired Menelaos man-to-man, or recklessly do battle, lest you be swiftly broken beneath his spear.”—Homer, Iliad (trans. Caroline Alexander)

And if you want to look beyond the Iliad itself, there's also this:

Next comes the Little Iliad in four books by Lesches of Mitylene: its contents are as follows. The adjudging of the arms of Achilles takes place, and Odysseus, by the contriving of Athena, gains them. Aias then becomes mad and destroys the herd of the Achaeans and kills himself. Next Odysseus lies in wait and catches Helenus, who prophesies as to the taking of Troy, and Diomede accordingly brings Philoctetes from Lemnos. Philoctetes is healed by Machaon, fights in single combat with Alexandrus and kills him: the dead body is outraged by Menelaus, but the Trojans recover and bury it. After this Deiphobus marries Helen, Odysseus brings Neoptolemus from Scyros and gives him his father's arms, and the ghost of Achilles appears to him. Eurypylus the son of Telephus arrives to aid the Trojans, shows his prowess and is killed by Neoptolemus. The Trojans are now closely beseiged, and Epeius, by Athena's instruction, builds the wooden horse. Odysseus disfigures himself and goes in to Ilium as a spy, and there being recognized by Helen, plots with her for the taking of the city; after killing certain of the Trojans, he returns to the ships. Next he carries the Palladium out of Troy with help of Diomedes. Then after putting their best men in the wooden horse and burning their huts, the main body of the Hellenes sail to Tenedos. The Trojans, supposing their troubles over, destroy a part of their city wall and take the wooden horse into their city and feast as though they had conquered the Hellenes.—Proclus, Chrestomathia

And this:

Concerning Aethra Lesches relates that when Ilium was taken she stole out of the city and came to the Hellenic camp, where she was recognised by the sons of Theseus; and that Demophon asked her of Agamemnon. Agamemnon wished to grant him this favour, but he would not do so until Helen consented. And when he sent a herald, Helen granted his request.—Pausanias

Say what you will about society in Ancient Greece, but it really is sad when the source material is even slightly more progressive than the retellings are, such as when Helen tries to resist Aphrodite. And that's not to say Helen has never been given a more assertive personality before, but when she is, it's usually at the expense of making Menelaus a terrible husband (again, Gill, Heywood). The only other one I can think of that even comes close to this without attacking another character is The Private Life of Helen of Troy by John Eriskine, and not only did it come out in 1925, but it's a sequel anyway too.

Going back to Elektra, I'm surprised there has yet to be a generational series on the House of Atreus as a whole, because wow did I forget how messed up this family was and I love it! You've got your family drama, your betrayals, your cycle of vengeance! And with Pelops' line specifically, it all leads up to a mother avenging her daughter and a daughter avenging her father. It's perfect! But seriously, if anyone knows of a show or book series covering Tantalus and his bloodline, please tell me!

Which brings me to Agamemnon, whose portrayal here I found to be interesting. So something about Elektra is that it's told from three different PoVs, and because of that, each views Agamemnon in a certain way: to Clytemnestra, he's the proud warrior who killed their eldest daughter; to Elektra, he's the kind father whom she misses dearly; to Cassandra, he's her captor and destroyer of her city. And even then, we still get these tiny glimpses of his true self beneath his usual stern exterior—that of an insecure man who's desperately trying to make something out of his family name after reclaiming his home, a name that had already been cursed since long before he was born. But maybe he can change that by gaining glory in war... even if it means sacrificing his own daughter for a fair bit of wind.

Then you have the clear parallels that are drawn between Clytemnestra and Elektra as the book goes on, simultaneously sympathizing and condemning both for the actions they take. Even Aegisthus probably would've been seen as a hero if this were any other story. And I feel like this is true to the original Oresteia as well, how not one person can be categorized as being solely a hero or villain, but human.

So go ahead and give me the love story of Hades and Persephone, but remember that it's mournful Demeter's tale as much as it is theirs.

Give me the stories of the women and goddesses who have long been ignored throughout the centuries, but remember that it's possible to write such tales without having there be a need to drag those around them down.

Give me love, give me drama, but most of all, give me understanding and complexity.

And going back to the books themselves, honestly, if there was anything negative I had to say about both of them is that the myths are retold pretty directly for the most part, something I myself didn't actually have much of a problem with, but I understand may be a turn-off for some people, especially if you're looking for something a little more deviating from the source material in terms of characterization. Also, for some reason, both Greek and Roman spellings are used, instead of just sticking to one, hence why I've been using Elektra instead of Electra, but not Klytemnestra and Kassandra for, well, Clytemnestra and Cassandra. Not unique to Saint, but still no less jarring.

Like I said, of the two, Elektra was probably my favorite, but there were still a ton of problems I had with it, some more nitpicky than others, I'll admit. I already went over my feelings on Helen, but besides that, seeing more of Elektra's relationship with her father before he goes off to war would've been nice to see too. I also feel like if each book absolutely had to be named after a single character, then I kinda think this one should've been called Clytemnestra instead since it really did feel more like her story than Elektra's, at least for me. Some parts also felt a little rushed, especially with how the final chapter just jumps from Elektra getting her revenge to the epilogue describing what had happened afterwards instead of actually showing it, which makes me wish this book had either been a little longer or divided into a duology—one part focusing on Clytemnestra getting her revenge while the other is focused on Elektra's, similar to how Aeschulys divides them in his Oresteia trilogy. Or if neither of these solutions while still keeping the book at the same length, then maybe Cassandra's PoVs could've even been saved for her own book instead.

Speaking of Cassandra, there's also the fact that her fate ends up being a mercy kill rather than the cold-blooded murder it was in the original, basically absolving Clytemnestra of any wrongdoing when it came to this. Admittedly, I wasn't as annoyed over it as I could've been and the choice made sense to me as far as the presentation of the characters in the novel are concerned, but at the same time, it'd be nice to see more retellings actually portray Clytemnestra as so far gone by the time Agamemnon returns that she ends up killing an innocent in cold blood rather than just being a mournful mother out for revenge. Seriously, it's possible to do both.

And as for Elektra herself, the fact that it is very heavily implied she has the complex that's been named after her is just... no. And if that's the case, here's hoping Saint never does an Oedipus retelling. I can handle it with the gods because they're gods, but not when its mortals.

Also, the fact that Theseus isn't even mentioned once in Elektra despite the fact that he (and Pirithous) tried to kidnap Helen when she was twelve always felt like a missed opportunity to me, especially considering the book was published after Ariadne, where Theseus is of course a major character and him and Pirithous trying to kidnap Persephone is actually mentioned. It wouldn't have added anything to the story, but I still think addressing that little connection would've been neat.

And yet despite all of this, I still loved it, as well as Ariadne, flaws and all. But here's hoping Atalanta will be even better!

#greek mythology#jennifer saint#ariadne#elektra#theseus#hippolytus#phaedra#clytemnestra#cassandra#helen of troy#helen of sparta#menelaus#agamemnon#house of atreus

71 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Treasure of King Priam

The tale of Troy is well-known among many. For some, the tale of the Trojan Horse was simply the start of Odysseus’s journey back home. For others, it was the tragic end of Achilles after his friend, Patroclus was killed by Hector, which led him to seek revenge before losing his life to Paris (which helped spawn the best selling novel of The Song of Achilles. At least, I think that’s what it’s about. I have yet to read Madeleine Miller’s book).

According to the Romans, of course, the war with Troy also led to the founding of their city. As to whether there is any truth to that, who’s to say. But a displaced group of people finding a home across continents does sound plausible.

But the tale of Troy is not simply a fight between two warring human factions. It was also a battle between the Greek Gods. In fact, the entire story of woe began with Eris, Goddess of Strife and Discord, and her being slighted by the other Gods. In turn, she created the Golden Apple on which was was inscribed: For the Fairest.’ This, in turned, sparked competition between the three main Goddesses: Hera, Athena and Aphrodite.

Not wanting to suffer the anger that would come as a result of choosing who the apple would go to, Zeus nominated Paris, prince of Troy, to choose in his stead. And, as the story goes, he chose Aphrodite. And thus, he was rewarded the love of the most beautiful woman in the world: Helen of Sparta.

The problem, of course, was that she was already married to King Menelaus.

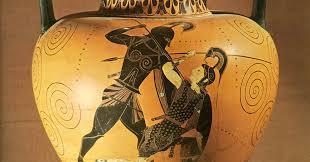

And so, from one simple choice, war sprung forth for ten long years. After all, Helen’s face was the one that led the launch of a thousand ships to bring her back home. The war the raged was one where heroes rose and fell on the battlefield until, at least, Odysseus came up with the most clever of ploys: hiding Greek troops in a wooden horse that would be presented to the Trojans as a symbol of the Greeks’ surrender. Feigning retreat, they would return in the dead of the night to an open gate and storm the city.

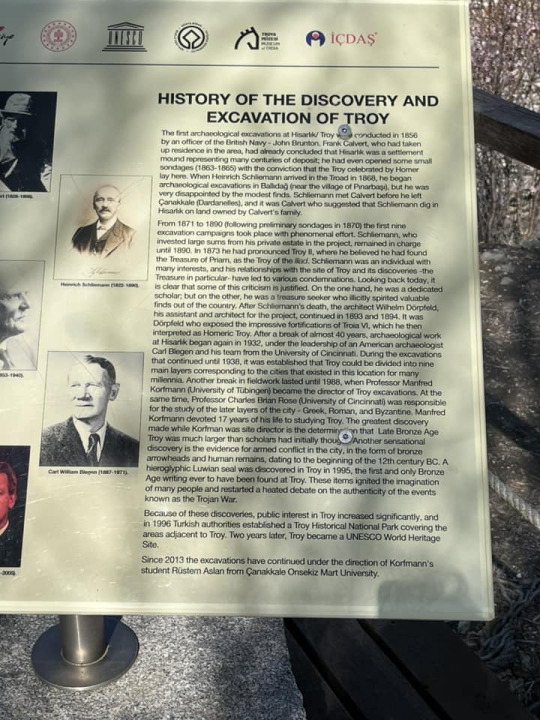

Ever since playing Age of Mythology and becoming obsessed with such stories, the tale of Troy was one of the very first to capture my imagination at a very young age. But I was the first such individual. In the 1800s, an archaeologist by the name of Heinrich Schliemann was also intent on uncovering the lost city. Though a dedicated scholar, he was also something of a treasure seeker and smuggled away many precious valuables out of Turkey for his personal gain. In his excavations, he also damaged quite a bit of the city and also incorrectly pronounced that Troia II as the one from the Iliad, though later scholars would grant the honour to Troia VI based on the defensive structures an imposing citadel.

While not as impressive as the remains at Ephesus, I still enjoyed my time exploring the ruins of Troy, or Troia as it was written, despite the cutting wind. There was even a statue of a wooden horse (not the original) created by the Turkish artisan: Izzet Senemoglu.

Another interesting fact about Troy/Trioa/ Hisarlik is that it isn’t very far from the Dardanelles Strait. Now, a student of modern history, and in particular, the world Wars, will know that this is where the famous battle of Gallipoli was held. And it was here that the allied forces launched the attack against the Turks in order to take the waterway linking the Black Sea to the Mediterranean.

After we finished looking around Troy, we drove to a restaurant in Gelibolu (Gallipoli) for lunch before taking the scenic route along the Sea of Marmara back to Istanbul for our second last day in Turkey.

Tomorrow promises to be an interesting day where we will visit a mosque and maybe do some shopping before heading to the airport for the long flight back to Sydney.

My time overseas has felt both long and short in equal measure but all such things must come to an end. I, certainly, am eager to go back home and bask in the familiar, even if the idea of returning to work and the stresses it promises doesn’t seem very appealing.

Still, I’ll be starting in a new position (which at time of writing this post, has been about a week and it’s going okay!). And there’s also the Toymaker story that I’ve been writing which needs to get finished before I can editing! Then onto the next the next story project that I’ve been meaning to write for a while now!

Oh, and games. Can’t forget those video games. During my time overseas, I was playing through quite a bit of Theatrhythm: Final Bar Line and there’s an impressions blog just waiting to be written up and uploaded!

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

You know what? You are right, up to a point.

These are all things I have been thinking about for years, and yes, we do tend to romanticize a lot of historical figures a little too much sometimes. But I think as human beings we build myths, and part of the foundation of myth is turning people and things into symbols and archetypes.

Why DO people care about royals so much, for example?

Because

a) ever since the middle ages, aristocracy has become short-hand for a certain type of courtly love, a certain imagery, a certain moral code. Kings and knights stand for oyalty, stand for devotion, stand for honour (or the subversion of those themes, like Galavant);

b) when people stand for entire countries, personal problems and decisions are amplified, dramatized to the maximum. You want to talk about betrayal? Here it leads to a war or an execution. About loving someone against the rules? You stand to loose a kingdom if you do it.

I enjoy the Arthurian cycle, and yet I think monarchy is a blight upon the earth. I like Hamlet and Macbeth, even though in real life I'd join the mob that kills them. I routinely listen to an album about Anne Boleyn, but the way she helped plunge her country into war doesn't sit right with me at all. I abhor the crusades with all of my being, I have argued with several people about them until we almost came to literal blows l, and yet I love Nicolò in "The Old Guard" . I will mantain that the Iliad is one of the best things ever written. I cry when I read it. Does it mean I think that slavery and body desacration are cool?

There is a difference between what an historical character actually did and were, and what they represent in a story.

Pirates are also an archetype, a narrative short-hand. They represnt freedom, and they represent outcasts that go against the status quo. "Black Sails" is a perfect example of this,and it does deal with racism and imperialism and misoginia and homophobia like few other shows do- yet the characters, which the audience comes to love, are pirates. Their namesakes have sometimes done terrible things, but there's the rub: this is not an historical series, Nor a documentary. In that case, I would take issue with a glorification of some of these man; in Black Sail's case, they stop being real people and become narrative foils for all outcasts. They become tragic and epic heroes.

I mean, take Juslius Caesar as a similar example. He was a dictator, a megalomaniac, a ruthless, cruel conqueror who wrote his own propaganda. Should we stop reading Shakespeare 's "Julius Caesar"? "Anthony and Cleopatra"?

The case of "Our Flag Means Death" is a little different, because it leans heavily into commedy and into the "oh they are just poor little meow meows" of it all, and I have to admit that although I enjoyed immensly I personally do have issues with the way they handled historical facts. I have to aknowledge, however, that they were very very clearly going for a "pirates as outcasts"/"piracy as queerness" symbolism that is a direct consequence of the way pirates have been conceptualized by the popular conscience for centuries.

So yeah, people do in fact remove concepts from their historical context and make them into symbols. They have ever since the beginning of time. We have made some people into gods, others into heroes, others into villains. We can love what they stand for in the collective immagination of our cultures, and then turn around and criticize the historical reality of them. It's possible, and it's not a contraddiction, nor is it strange or a new phenomenon.

It seems that we do not do it (much) with RECENT historical figures and movements, but that's what the filter of time does: it removes context, and leaves the outline. It is the work of the historians, and of us who live in history, to figure out what that context was and discuss it. It is the work of the artist and the reader/viewer to figure out what the outline can stand for in the metaphorical story of humankind. There is a time and place for both.

Those are my two cents anyway.

also like pirates in general and piracy as a practice throughout all of history are inextricably intertwined with human trafficking, especially slavery, and if youre not willing to have a discussion or even acknowledge that in your story.... dont write about pirates?

#I try to stear clear of internet debates#but the relatiosnship between fiction and reality has always been more complicated than#they did terrible things therefore let's hate them#if we reasoned like this#we would have to stop reading half of the world's literature#pirates

3K notes

·

View notes

Note

I'm currently reading lattimore's iliad, and I'm planning to read an oresteia translated by Anne Carson. What are some other works you'd recommend/love? And the translation you like. I want to read up on the classics as I didn't really go to school past 14, and I love how passionate you are about them, so I thought I'd ask, thanks either way!

hi! sorry for taking one million years to reply to this :/ every time i try to make a Brief list of my fave texts i explode. also please bear in mind that this is a list of Texts I Personally Really Like and not a list of Texts That Are The Hashtag Classical Canon.

if you enjoy(ed. it's been a while) the iliad and An Oresteia then probably try the odyssey? i like emily wilson's translation and also ive said this before but her introduction is soooooo good. she has a translation of the iliad coming out next year and i'm probably more excited to read her introduction to it than like. the actual translation

also in the genre of epic (the best genre) i actually prefer latin epic so. definitely the aeneid (post on different translations here!) which is also very uhhh foundational for so so much of subsequent latin literature. including my other favourite epic poem, lucan's pharsalia (post on translations again!) which is a historical epic about the civil war between caesar and pompey.

this is where the list gets very much into things i personally like. the pharsalia is so cool to me because it's not a history/historiography but it Does do weird things To history and gets away with them because of its genre. veryyy similarly, aeschylus' persians is a tragedy (the only surviving tragedy based on historical events!) about the persian response to defeat at the battle of salamis. i don't have a preferred translation for this one just read whatever! but definitely read some sort of introduction or the wikipedia page because it's weird for a Lot of reasons. also necromancy happens. and there's boats. what more can anyone want!

i've also been really into livy's ab urbe condita atm. it's a history of rome but the first 5 books especially are very. well i just don't think that actually happened. BUT the early roman like. political myth making is cool actually! (if only because if you read it then when lucan is like oh and the ghost of curius dentatus was there you can be like oh i know who that guy is! a Lot of latin lit involves invoking historical exempla and livy is a major source for a Lot of those.) i actually care very little about greek myth (and the take that the romans just 'stole' greek religion. like what) because i think the romans' mythologisation of e.g. lucius junius brutus is way more fun. but ALSO livy was writing a history starting from the Foundation of rome at a time when augustus was 'ReFounding' rome so you're always a bit like. hmmmmmm. or like you read about coriolanus in livy and you're like oh wow foreshadowing of the political situation that would later lead to the civil wars! but then you remember that livy was writing it After the civil wars and then you fall into the livian timeloop and then you explode.

ok now ignore livy because my favourite historian is actually sallust. would recommend william batstone's translation of (and introduction to) the bellum catilinae. Catilina Is There. sallust's catiline is soooooo sexy like his countenance was a civil war itself! enough eloquence but not enough wisdom! animus audax subdolus varius! he's haunted by sulla's ghost! he's didn't cause the fall of the republic so much as he was a symptom of it! he's an antihero! he's cicero's mimetic double! he probably doesn't drink blood! he would have died a beautiful death IF it had been on behalf of his country (except that quote is actually from florus maybe via livy lol)! He Did Nothing Wrong. you want to read the bellum catilinae soooooo bad. also it is v fun to read alongside with cicero's catilinarian orations (the invective speeches against catilina). i think i read the oxford world's classics translation of those but i Cannot remember who it is by.

also you know what i really like what i've read of florus' epitome of roman history which is maybe kind of a summary of livy but also florus is totally doing his own thing (he is sooo influenced by lucan! nice!) highly recommend the (relatively brief) section on the first punic war. it does cool things with boats.

i also love plutarch's life of cato the younger!!! one of my favourite ancient texts of all time ever. like a) it's plutarch and he is fun. would recommend the life of alexander the great as well tbh. and b) it's cato the younger and he is so so so fucked up.

finallyyyyyy bcs this is getting long. the poetry of catullus (and a post on translations is here!) like It's Catullus. the original poor little meow meow. what more can i say

#please be aware also that i made this list via What Came Into My Brain and in a few hours i'll probably be like#how the fuck did i forget like. idk. seneca's thyestes#actually real and true. senecan tragedy does also slap. emily wilsons translations are good also.#book list#beeps

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

@ everyone in the last post pointing out that Odysseus slept with other women while he was trying to get back to Ithaca like it's brand new information: first off, we know, thank you, we've read the damn book.

Secondly, have you read the book? In neither case is Odysseus' tenure with Circe and Calypso portrayed as fully voluntary - he's an outright captive of Calypso and spends all his free time crying and staring at the sea. Things didn't get off to a great start with Circe either. I feel like the modern interpretation of the encounters with the goddesses in the Odyssey make it out as though Odysseus was just screwing around for the ten years between the end of the Trojan War and his homecoming, but that is reading against the text pretty significantly. I'm not saying there's 0 textual support for that reading but there's much much more in the opposite direction. The Odyssey is a nostos story - it derives its narrative tension from Odysseus' struggle to get home, so the story doesn't happen without the challenges he faces along the way.

Third - when you reduce the episodes with Calypso and Circe to "Odysseus is a bad husband because he cheated on Penelope", you're missing a really interesting parallel to the Iliad, where the events of the story are precipitated by a fight over a captive woman. We don't actually get very much of Briseis' perspective, despite the fact that the story couldn't start without her. She has very few lines of dialogue. But when we get to the Odyssey, now the story starts with the main character who is essentially powerless in the role of a slave concubine. Do the gender ramifications there not make your head spin? In the Iliad, a straightforward poem about straight shooting heroes, which romanticizes war as much as it critiques it, the experiences of the war captives is all but absent. In the Odyssey, we see the aftermath of war and its impacts up close and personal, although the narrative comes at it at an angle (incidentally, the way Odysseus himself comes at problems). If you don't want to examine that because you think Odysseus was a bad guy for cheating on Penelope... okay? That's your prerogative I guess. You're missing out some of the best stuff in the poems though!

(Incidentally I'm not saying Odysseus is a *good* guy, either - he's a man of many ways, as Emily Wilson put it, he's "a complicated man" - but that's what makes him so interesting! If he were 100% wholesome and Unproblematic, we wouldn't be reading this shit 2800 years later! Trust me! There are some extremely boring ancient works I've read where everybody does exactly what they were supposed to do! I'd rather read the Odyssey!)

Fourth, and I don't exactly know how to frame this, even if you take Odysseus' captivity with Circe and/or Calypso as infidelity... that doesn't actually mean that he and Penelope don't still have this crazy powerful bond! He deploys all his cleverness to escape from Calypso (even though she offers him immortality!) and then from Circe (in part) because they can't offer him the like-mindedness he has with Penelope! He leaves because he wants to go back to Ithaca, his kingdom, and his family! And it's not some kind of secret affair! Odysseus TELLS Penelope about both of them the same day she finally recognizes him and they reunite! If it is infidelity, it doesn't compromise the foundation of their relationship.

Sorry for the long post y'all but I could not let this go

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Thanks for the mention @prompted-wordsmith

Yes I have mentioned many times in the past how Homer clearly is stating Odysseus was unwilling. In fact I answered an ask about it very recently;

In it I include answers to OP questions as to what the "no longer liked the nynph" line and the clear lines where it is stated he had no choice. Both with her and circe by the way.

In more than one occasion he calls her "dreadful goddess". A goddess that brings fear. Homer mentions Circe being afraid because she was never resisted against before. She is not afraid for her life for she is immortal. My estimation goes that she is initially afraid of Odysseus because she assumes he either is a God or protected by Gods much higher than her thus him being unaffected of her spell. Odysseus himself was so afraid of her to the point that he sleeps with his comrades after their return from the underworld and he is brought inside by Circe. In more cases than one he expresses his horror for them but as @prompted-wordsmith said he cannot speak bad of gods the same much that he hasn't spoken badly for other kings as well not even for Neoptolemus whom we know killed at least Priam upon an altar.

Emily Wilson is not just mistranslating many passages (I discover so many errors in passages that is even funny at points because what she translates makes no sense apart from fitting her narrative or at best her metric system). She also supports Telegony to my knowledge which has way too many contradictions with the Odyssey including his death prophesied by Tiresias. She also brings as a reason why Odyssey has no definitive ending and that there is more not because the prophecy of Tiresias that is yet to be fulfilled but because "Odysseus wants to flee his home and be absent again" which makes no sense in narrative. Odysseus is known for violence more times than one can count, yes, but he never seeks it and he tries to avoid it. Willson is incredibly biased in the feministic movement from what I see and more often whatnot she claims stuff that are not just blunt but often seem deliberate. Is she a good scientist? Absolutely she has studied a long time. However she has tried many times to use her work to push her narrative. She even seems to be supporting modern retellings like Miller for their feministic takes even if even non experts know how inaccurate they are (that is what I heard by the way do not take this as 100% fact for I am not 100% sure on it) but she has the tendency to translate the men in her story as evil as possible or using deliberately words that lead to that (for instance she names Agamemnon "cannibal" among others where there is no such word in the Iliad)

I find it interesting that you keep mention misogyny given how incredibly woman-centric the Odyssey is. Helen is a queen who speaks her mind and gives solutions, Penelope is regent who rules in place of her husband till Telemachus is of age. Circe is a goddess who lives in her own accord and is eventually redeemed and given a complicated personality, Arete is the powerful figure that Odysseus has to plead to when he reaches Scheria, Nausicaa helps a stranger in her own accord. Euryclea is also a slave and yet she enjoys a lot of privilege in her household etc. Half of Odyssey revolves around women and women in various cases of power and they are shown incredibly positively. The only woman that is badmouthed in the Odyssey is Clytemnestra by Agamemnon and let's face it Agamemnon was her victim of course he would speak bad of her. Agamemnon in fact praises Penelope so his problem is not against women either but against the specific woman who he believes wronged him. And of course Athena being a central figure. Are women equal in Homer's time? Absolutely not. We have binary roles and eveey part is doing its own thing. But "misogyny" implies that Homer deliberately depicts women negatively because he hates them. That doesn't happen in the Odyssey. In fact the focus on women is so great that led people like Butler speak on a female writer in the Odyssey.

The answer as to why didn't Poseidon attack Calypso's isle is very simple OP. Poseidon never wished to attack Odysseus to kill him. He wanted to detain him. Calypso was doing that job for him and he didn't need to do anything. Once Odysseus was released his anger was released anew and he sank his raft. Odysseus swam to Scheria. After that the prophecy was completed. Poseidon knew that Odysseus would return home as per the second part of the prophecy.

I also see how you say that Penelope was a prize for Odysseus where it simply wasn't the case or I believe you forget or never seen Pausanias where he mentions that Odysseus gave Penelope a choice and Penelope chooses him as her husband. If she wanted she could have stayed with her father. She was never a prize. In fact many sources claim that Odysseus invented the Oath so that he could get a chance to fight for her hand. He has to face her father in a race as well. But even if we take it as correct and assume that Penelope was "his prize" that still doesn't necessarily imply that he had a willing affair in Homer. In fact we see many different characters that end up with the woman they considered a Prize (ironically Hades included) such as Ajax the Greater who keeps his war prize close like a wife and we see that to Sophocles's play. Other characters like Euryclea were also mentioned in the Odyssey and how Laertes was fond of her but he never took her to his bed because of his wife Anticlea. Euryclea was also a prize technically and she was treated with respect. Also in one way then Helen should be considered a "prize" to Menelaus as well and yet Menelaus started a war for her (now there are of course some sources that mention Menelaus having slaves to his bed but that is another story). Even if one considered Penelope "his prize" still is not necessarily an indicator that Odysseus cheated on her willingly and Homer seems to make it clear in my opinion.

The case of Ismarus is a case where Homer shows the dark side of war and warfare after 10 years. Also Odysseus and his men were pulled away by a storm. Piracy was a very common way for people to get provisions. But I don't know why you bring Ismarus to strengthen your opinion that Odysseus cheats on his wife. Like "he enslaved all the women of Ismarus and therefore all women are products to him"? That is not how it works. In fact Odysseus aspired enough loyalty so that only 12 out of his 50 slave girls betrayed him. The case of Ismarus is what war and famine did to the men. And of course the enslavement of women was a common trope for wars (I touch the subject to my own fanfiction and retelling of Ismarus) which was so that Homer shows a spherical view of the character including the darker side of both him and his men during the war.

I also see that you say "Penelope's name is missing from the story" as a proof but in reality the story was not about her exclusively unlike what modern retellings say. Odysseus knows he has to see his men in the here and now. He knows where Penelope is and his goal to go home. Homer uses the word νόστος which gives the name to words "nostalgia". It means the return home. Home is everything in it including family and loved ones. Odysseus in many occasions speaks on "his loved ones" that include Penelope. He doesn't need to mention her name every five lyrics. And he says his story because again Odyssey is a poem about return. It is not a love poem of a lost husband to go home. Like I said it is a NOSTOS a tale for return home and to your loved ones. Telling one's story is also part of the law of Xenia. As to why he doesn't resist Hermes is very easy again the point was the arduous trip not Odysseus screaming the name of Penelope every five minutes. What was more nothing Odysseus would say to Hermes would change a thing. He had no choice but to accept Circe's bed if he wanted to save his men. Homer adding extra 100 lyrics to show a moral dilemma wouldn't change a thing. What is more like I said before Odysseus is a man in a survival mode. He has a goal before him and that is to save his men. Not to cry his own miserable fate. Which is again why he shows no hesitation or at least he doesn't mention any. And again he has already explained himself that "there is nothing sweeter than one's home and loved ones". We already know his motivation by his actions. He doesn't need to have a mental breakdown every second page in the Odyssey. Odyssey is an epic poem not a lyric song or a tragedy.

In scheria he doesn't cry of nostalgia. He cries of guilt. If you read how Odysseus is described to cry like a widow over the husband etc. It is literally a passage that photographs the fall of Troy. Odysseus cries of guilt. And yes he doesn't want to go home only because of his wife. He wants to go home because it is his beloved land: the place he was born the place he lived. His Nostos again is to go back home and to everything in it.

You say that he "suddenly being helpless against goddesses" is out of character? Sorry OP but that is straight out wrong in my opinion. Both Calypso and Circe are goddesses. He cannot kill or face them. Would you then say that Helen who chooses her husband being helpless against Aphrodite is out of character? Also interesting how you mention Skylla Charybdis and Sirens which are the ultimate proof of how helpless Odysseus was. Every stop of his trip was a painful sacrifice, a loss for him and a reminiscent of his mortal nature. Would you call Heracles "out of character" because he couldn't resist the madness Hera invoked him just because he killed the snakes she sent? No, I believe. The same goes for Odysseus.

I am not gonna comment on the "mass rapist" characterizations you bring because i believe in my humble opinion they miss the point of mythology. Mythology unlike epic poetry or plays are massively allegorical. The "lack of consent" in the myths is a symbol that the humans cannot resist the will of the gods (also Hepheatus doesn't rape Athena. He attempts to though) but even if you intend to use the gods and such as an example then it actually shows even more how helpless Odysseus was against goddesses. And since you bring the subject of rape and want to take it to its literal form I shall respect it and say that gods and goddesses pictured as selfish to their erotic pursues is yet another reason to show how helpless Odysseus was against the goddesses.

As for why are not other sources reliable to interpret the Odyssey itself is the same reason as Ovid is not a source for the myth of Medusa; future writers interpreted it according to their own views and as you rightly said according to their biases from their time. There are various of versions of the myths as well and Homer himself seems to be winking at thwm

I also find it ironic that you say "modern adaptations" make Neoptolemus the killer of Astyanax. Most ancient sources including Little Iliad from the Epic Cycle mention Neoptolemus as the killer of Astyanax. The only source where Odysseus himself kills the child is Iliou Persis. Most of sources and art speak on Neoptolemus killing the baby and Eurypedes who was always writing Odysseus negatively, places Odysseus as the mastermind behind the killing

I admire your attempt to use many different sources but I think you used the wrong examples here or that you miss pieces of information. But even after what I told you you still wanna stick to your interpretation I absolutely respect it but bear in mind what is here. However in my humble Opinion what you listed would be great to interpret Odysseus from the other sources you mention which name the affair with Calypso as a willing one. Homer seems pretty clear with his mention of how both affairs are unwilling

Now if you want to interpret the passages differently is of course valid and a very good attempt to add all the different versions but I feel like the way the train of thought was it wasn't very right. But I could be wrong. Either way it is great that you tried to use the sources to support your opinion.

Odysseus and Calypso Were Lovers

As problematic as that sounds because WTF, hear me out because it's complicated and there's a lot to discuss. Trigger warning for sa. Also, not directly Epic: The Musical related; that's a whole other ballpark.

She trapped him on her island!

I'm not denying that nor am I denying how objectively messed up that is.

However, the captor and prisoner trope is one that does crop up in Greek mythology now and then. The most famous example I can think of is Hades’ kidnapping of Persephone. I have seen that situation blatantly called rape in the original story, and yet today, modern storytellers do like to revise that myth into a version that makes Demeter out to be an overbearing mother and Persephone's ‘kidnapping’ so to speak becomes an escape. Personally, I think that is a very graceful way to make a barbaric story a bit more palatable to modern audiences.

So regarding Odysseus’ situation where falling in love with his captor is problematic…my thought process runs as, “Fucking Greek mythology and its weird idea of what constitutes as a love story.”

As a result, I have no serious thoughts on the morality of certain figures of Greek mythology because they frankly come from a time period where the people had a very different culture and set of moral values and ideas on what was acceptable. Therefore, it's futile to judge their stories by my own modern moral compass.

Where in The Odyssey does it say they were lovers?

The main line I can't ignore that strongly implies the nature of their relationship is Odysseus' farewell to Calypso:

“The sun went down and brought the darkness on. They [Odysseus and Calypso] went inside the hollow cave and took the pleasure of their love, held close together.” - The Odyssey, Homer, translated by Emily Wilson.

Keep in mind, she’s already told him he’s free to go. He’s free to build his raft, she’s giving him supplies, and yet he says goodbye this tenderly. Note the absence of Calypso using magic to compel him. If you cherry-picked this line, you'd find a fond goodbye.

Odysseus’ Tears

A lot of people making the ‘Odysseus/Calypso was a non-consensual situation’ argument like to cite the line that Odysseus cried every day on Ogygia. And yes, he did weep every day he was there. But this is the full stanza.

“On the tenth black night, the gods carried me till I reached the island of Ogygia, home of the beautiful and mighty goddess Calypso. Lovingly she cared for me, vowing to set me free from death and time forever. But she never swayed my heart. I stayed for seven years; she gave me clothes like those of gods, but they were always wet with tears.” - The Odyssey, Homer, translated by Emily Wilson.

‘Beautiful and mighty….Lovingly she cared for me….she never swayed my heart.’ He speaks highly of her, not with hate or venom for her delaying him.

In my literature class where we read The Odyssey, the tears line was discussed and largely interpreted as Odysseus’ reaction to all the monsters he’d faced and losing all his crew and friends. The PTSD of a war veteran. From the cultural mindset of Ancient Greece, Odysseus was a king, and he failed his people when they all died under his command and he was unable to bring them home. Similarly, the hero Theseus was once king of Athens. He was usurped in absentia (Theseus being trapped in the Underworld at the time) and when he returned to his kingdom, he found another man on his throne, was forced to flee, and died a rather ignoble death when a supporter of his usurper shoved him off a cliff. So Odysseus being a king who let an entire fleet die under his watch is certainly grounds for shame to the point of tears in the eyes of the Ancient Greeks. And with an entire line-up of men attempting to court his wife and take his place, it drives home the idea that he was replaceable.

Also important to note: He’s still miserable when he leaves Ogygia. When he arrives at King Alcinous’ court, he is welcomed, provided food, shelter, and entertainment, but when the king checks in with his heartbroken guest, he pleads with him to tell him what’s wrong, which kickstarts the telling of Odysseus’ journey.

Odysseus was afraid of Calypso!

That said, it's also important to address this concept because this is Odysseus' reaction to the goddess telling him she is sending him on his way to Ithaka:

‘Goddess, your purpose cannot be as you say; you cannot intend to speed me home. You tell me to make myself a raft to cross the great gulf of ocean--a gulf so baffling and so perilous that not even rapid ships will traverse it, steady though they may be and favoured by a fair wind from Zeus. I will not set foot on such a raft unless I am sure of your good will--unless, goddess, you take on yourself to swear a solemn oath not to plot against me any new mischief to my ruin.’ The Odyssey, Homer, translated by Shewring.

His suspicion certainly suggests mistrust and fear that she intends to do him harm, and considering his track record of being hated by deities, that's understandable. This isn't exactly what you'd call a loving relationship. But this also brings up a weird contradiction in the poem. I would 100% say this was a completely non-consensual situation were it not for this line:

His eyes were always tearful; he wept sweet life away, in longing to go back home, since she [Calypso] no longer pleased him. - Wilson.

Not ‘she did not please him.’ She no longer pleased him. That implies she 'pleased' him at one point and because of that, one could argue Calypso was a mistress and Odysseus eventually tired of her. (Probably long before seven years had passed.)

What Do The Translators Say?

I can't speak for all translators, but in the Emily Wilson translation, she includes a lengthy introduction describing Odysseus' world, the culture of Ancient Greece, the reasoning behind specific English wordage in the translation, etc. In the introduction, she refers to Calypso and Circe as Odysseus' affairs. Not his abusers. He also has a brief flirtation with Princess Nausicaa, the daughter of his final host, King Alcinous. Wilson then goes on to describe how these affairs are not a character failing of Odysseus in comparison to the treatment of Penelope where she is expected to be faithful and how that is indicative of a good woman.

Taking a step back from Greek mythology, consider the actions of King Henry VIII of England. Most historians agree that, for the first few years, the king's relationship with his first wife Katherine of Aragon was unusually good for the times. And yet he was an unfaithful husband, had at least one acknowledged bastard and historians speculate there were more. But while 'indiscretions' such as this were frowned upon in the Tudor Period, Henry VIII did not receive near as much criticism as Queen Katherine would have if she'd had an illegitimate child. If Katherine was 'indiscreet,' that was considered treason because she compromised the legitimacy of the succession and that was cause for a beheading.

Because misogyny. Again, different time, different moral values.

Misogyny in The Odyssey

Whatever one's thoughts on Calypso are, it is incredibly misogynistic of Homer to solely blame her for keeping Odysseus trapped while he conveniently ignores the plot hole that her island is completely surrounded by ocean and we all know that Poseidon was lurking out there just waiting for his shot at vengeance. Odysseus is barely two stanzas off Calypso’s island before Poseidon goes after him. It’s almost hilarious how quickly it happens. The poem says Poseidon was returning from Ethiopia, not that he was there for the whole seven years, and Hermes clearly did not pass along the memo that Odysseus was free to return to Ithaka. Although I like to imagine it was Zeus who forgot about Poseidon’s grudge against Odysseus, and Hermes, being the mischievous scamp that he is, did not remind him.

If one line in the text says Odysseus/Calypso was consensual while another says otherwise, which is it?

Honestly, I don't think there's a conclusive answer with just The Odyssey. I'm a hobbyist, not an expert, so I do refer to the judgment of translators like Wilson to make that call. If she and other translators say Calypso and Circe were affair partners and I can see the lines in the text to support that, I'll believe it and chalk up the rest as Greek mythology being problematic.

That said, we can also look at the opinions of other Greek poets in their further writings of the mythology:

“And the bright goddess Calypso was joined to Odysseus in sweet love, and bare him Nausithous and Nausinous.” - The Theogony; Of Goddesses and Men, Hesiod, translated by Evelyn-White.

“… after brief pleasure in wedlock with the daughter of Atlas [Calypso], he [Odysseus] dares to set foot in his offhand vessel that never knew a dockyard and to steer, poor wretch…” - Alexandra, Lycophron, translated by Mair.

Both seem to be of the opinion Calypso was Odysseus' lover.

Interestingly, Hesiod also writes in The Catalogues of Women Fragment:

“…of patient-souled Odysseus whom in aftertime Calypso the queenly nymph detained for Poseidon.” - The Catalogues of Women Fragment, Hesiod, translated by Evelyn-White.

The wording ‘detained for Poseidon’ implies Calypso was acting at Poseidon’s command or she was doing the sea god a favor or she possibly didn't have any free will herself whether or not Odysseus stayed on Ogygia. Either way, it does neatly account for Homer's aforementioned misogyny/plot hole.

But if Hesiod and Lycophron's works are not part of The Odyssey, why should we take them seriously?

You don't have to consider them canon. Just because I prefer to consider all mythology canon doesn't mean anyone else does. Just as easily, I could ask why we should take Homer's work seriously even though historians can't even agree whether or not he was a real person.

The truth is, Ancient Greece as we think of it lasted a thousand years. Their culture/values changed several times and so did their stories to reflect those changes, and those stories continue to evolve to the modern day. Odysseus himself goes through a few different descriptions over the centuries, being described as scheming and even cruel in other works. So I consider modern works like Percy Jackson, Epic: The Musical, Son of Zeus, and so on to be just more cogs in the evolving narrative. Much like how retellings of Hades and Persephone are shifting to circumstances easier to accept by audiences today.

But why would Odysseus be unfaithful to his loving wife?

The loving wife he claimed as payment for helping out King Tyndareus? Yeah...Odysseus and Penelope's relationship may not quite be the undoubted loving one modern retellings make it out to be nor is Odysseus a saint in The Odyssey.

“A blast of wind pushed me [Odysseus] off course towards the Cicones in Ismarus. I sacked the town and killed the men. We took their wives and shared their riches equally amongst us.” - The Odyssey, Homer, translated by Emily Wilson.

Raiding a town unprovoked, killing the men, kidnapping the women, stealing their treasure is not indicative to what we in the modern day consider heroic or good protagonist behavior. Also, at the end of the Trojan War, Queen Hekuba was made a slave and given to Odysseus.

As for the chapter with Circe, Penelope's name isn't even mentioned. Moreover, the wording of the Wilson translation gives the troubling connotation that Circe may have been the one who was assaulted.

Hermes’ instructions to Odysseus are as follows:

"...draw your sharpened sword and rush at her as if you mean to kill her. She will be frightened of you, and will tell you to sleep with her." - Wilson

She'll be frightened of him? Hermes is encouraging Odysseus to render Circe powerless by eating the Moly plant so she can't turn him into a pig, then threaten her with a sword, which does frighten her, and then sleep with her. That line of events is disturbing. Circe is the one who offers to take Odysseus to bed, sure, but there’s a strange man in her house, she’s allegedly afraid according to Hermes, and she’s unable to resort to her usual defense and turn him into a pig as she did with the others. Under those circumstances, sleeping with an invader is a survival tactic.

However...after Odysseus makes Circe promise to turn his men back, she bathes him and gives him food like a proper Ancient Greek host. Yet before Odysseus accepts the meal, he puts his men first, saying he can't bear to eat until he knows they're well. So Circe turns them back, then Odysseus returns to where the rest of the crew are waiting on the shore. They're all convinced their comrades are dead until Odysseus tells them what transpired and they rejoice. All except suspicious Eurylochus who calls them fools for trusting Odysseus' word based on his previous bad decisions. Odysseus thinks about cutting his head off for speaking that way. Damn, that went from zero to a hundred fast.

But Penelope's name is missing from the story.

Odysseus only thinks of leaving Circe's island when his men speak of returning to their homeland, after which he goes to Circe about the matter, and she instructs him to go to the Underworld.

"That broke my heart, and sitting on the bed I wept, and lost all will to live and see the shining sun." - Wilson

Odysseus and his men all lament the idea of sailing into the land of the dead. So his tears and despair did not start with Calypso. Also, they return to Circe's island after the journey so she can help them make sense of Tiresias' instructions.

But setting all that aside, even when Hermes instructed him on what to do, Odysseus didn't make some grand speech on how he can’t betray his wife. He doesn’t specifically say he’s crying for Penelope on Calypso’s island. He doesn’t mention Penelope at all, and when King Alcinous asks him about his sorrow, Odysseus tells his whole story, barely bringing up his wife or his love for her.

So is Odysseus a good guy?

In all, Odysseus is a clever character who is known for using his wits to get out of any situation. Polyphemus, the Sirens, Scylla, he had a plan. The idea that he’s suddenly helpless against Calypso and Circe is out of character. They may be goddesses, but they’re not exactly the heavy hitters of the pantheon, which is why Poseidon could absolutely order a minor sea nymph to stop what she’s doing and hold a man prisoner for him. And while Odysseus spends the entire story being thwarted by the gods, one could say he also thwarts the gods right back by refusing to give up.

Like most Greek heroes, I would say Odysseus is not what we today would call a hero. But when he shares a roster with characters like this:

Zeus: Serial rapist

Poseidon: Serial rapist

Hades: Kidnapped Persephone (setting aside modern interpretations she went with him willingly)

Herakles: Raped a princess named Auge (Yes, really.)

Theseus: Kidnapped Helen of Sparta when she was a child because he wanted to marry a daughter of Zeus, aided and abetted his cousin in an attempt to kidnap Persephone, abandoned Ariadne, etc.

Jason the Argonaut: Tried to abandon his wife. (I say ‘try’ because he didn’t get the chance. His wife Medea killed the other woman first.)

Hephaistos: Raped Athena after she refused him.

Achilles: Murdered a child to prevent a prophecy from coming true.

...Odysseus's atrocities are weirdly tame by comparison. Even the narrative where he kills the infant Prince Astyanax, modern retellings usually give that role to the lesser known Neoptolemus. More on that here.

In the end, it's not necessarily thematically important whether or not Odysseus is good or bad. The core of his character revolves around his cleverness and ability to build and strategize and make his own way in the world he lives in. Rounding this out is Emily Wilson's commentary on the symbolism behind the tree bed,

"In leaving Calypso, Odysseus chooses something that he built with his own mind and hands, rather than something given to him. Whereas Calypso longs to hide, clothe, feed, and possess him, Athena enables Odysseus to construct his own schemes out of the materials she provides." - The Odyssey, Homer, trans. by Emily Wilson, Introduction Pg 64.

So were Odysseus and Calypso lovers?

Based on the above, my opinion is 'Yes they were, but with the caveat they were problematic af.' Because problematic themes like that are pretty par for the course in Greek mythology.

76 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mystics, Chapter 36

84,000 words later....

I can’t thank everyone enough who sent in asks, commented, liked, and reblogged Mystics as it was being created. It meant the world to me and gave me so much inspiration to continue! Special thanks to Myst, of course. Continue to send in asks for the OCs as much as you want. A part 2 is in the works.

Enjoy Mystics’ final chapter. I hope its been as much fun to read as it was for me to write! <3

Xx -Alpaca

Taglist: @myst-in-the-mirror & @livingforthewhump

CW: captivity, blood mention, drug mention, cheesy dancing at the end.

------------------------------

CHAPTER THIRTY-SIX: THREE LITTLE BIRDS

Remember: Matter. How tiny your share of it. Time. How brief and fleeting your allotment of it. Fate. How small a role you play in it.

- Marcus Aurelius, Meditations.

Shining white, pristine walls lined the hall. It didn’t take long for Hekate to catch up. Paimon didn’t know why he expected anything less. Now his arms were held behind his back by a cosmic force, unknown even to him, and the inorganic urge to continue walking by her side pushed him forward. He spoke little, and listened even less to what the old hag was saying.

“I cannot promise you will be happy here, but at least you will not be alone in your imprisonment,” Hekate said.

They turned around a corner through the maze of halls and landed upon a wide set of sliding doors. The whole realm was practically space-age. Hekate was clever to disguise the entryway to her realm as his own Labyrinth.

He should never have jumped through. That was a rookie mistake. The moment Apollo was released, he should have known something was amiss. Lyrem certainly didn’t have the talents to perform such a feat.

“This is best for you, Pan,” Hekate continued. “I know that with a little more helpful guidance, you can return to your true nature, and your true glory.”

“Paimon.”

Hekate paused. “No, no, no, my dear. You are Pan. You always have been Pan. You will always be Pan.”

The sliding doors opened. Inside this room there was yet another hallway, but instead of previous areas, this one was lined with clear walls. Perfect for seeing through into the cells that would hold a chosen prisoner.

Many of them were empty. Hekate continued toward the end, until Paimon reached the last of the cells. There was a simple bed and some books on a nightstand that had been left untouched. The room was covered in a white rubber. The bed, made of wood.

“I am not going in there,” Paimon said, his brows furrowed.

Hekate agreed with a nod of her head.

“You are correct. You are going into this one.”

The cell door across from the one that had taken Paimon’s attention opened with a whirring noise. Unable to stop himself, Paimon stepped through the threshold. The door whirred shut behind him and he was released, finally, from whatever command Hekate had over him.

“This is an abuse of power!”

“An abuse of power is what you had for many, many years on Earth my darling dear. And quite frankly, I have had enough of your games,” Hekate observed calmly. “You will have much in common with your cellmate. Let me put it simply, Pan. The sooner you behave, the sooner you will be released.”

Pan- no! Paimon looked around his new home as new objects formed around him out of nothingness. A simple bed, nightstand, all as white as snow on Christmas day and one thing in the corner that stood out among everything else because of its red mahogany sheen- a Pan flute.

“If you wish to have anything more, then you will need to earn it,” Hekate stated.

Darkly, Paimon turned around, meeting his great aunt’s eyes.

“I will destroy you for this. I will ruin you. I will make sure no one ever knows of you. I will turn you into a forgotten relic! Just as you deserve to be!”

Hekate raised a brow to show how meaningless Paimon’s threats truly were to her.

“I would think it something to be admired, if you could do any one of those things, darling dear. Certainly, if even your own father could not do those things, then it would be worth true congratulation.”

Paimon charged the clear wall and then stole a glance to the cell across from him, where someone had returned from using a restroom. The mysterious person sat on the edge of his bed. Someone vaguely familiar, with light eyes and a trimmed white beard, looking drastically different than he remembered. Paimon blinked.

“Dad?”

---------------------------------

“Have you ever heard the tale of Sisyphus?”

“It may shock you to learn I haven’t ever quite finished the Iliad, but yes, I have.” Lyrem replied to Hades’ question. “So, you’ll have repeat a meaningless, trivial task for all eternity in my afterlife as a punishment for imprisoning you as per Pan’s command. How very original. Did you think of that all on your own, or did you need your brother’s help?”

“My brother Zeus has not been heard from for a millennia. While he had given me some inspiration, I thought it better to put my own ironic flair into your suffering.”

Persephone interrupted with a short squeak.

“No, uncle, please don’t be so ruthless. He’s lost so much already!”

Artemis had switched back into her cat-like form, comforting her brother Apollo in his lap and purring. She had let out a protest of her own in Lyrem’s favour as well.

Apollo translated. “Arty agrees. We should be kind to him. Truly uncle, I have to imagine that Pan had quite the psychological hold on this man. Perhaps it would be wise to show him a tad bit of mercy?”

Hades looked to the naïve children and back to the human-mortal-man with growing disinterest. Then a light crossed his face, as though an idea dawned on him. He allowed himself to smile, ever so gently.

“Well, I can see that you have created quite the positive rapport with my nieces and nephew already. I don’t know why I am so surprised.”

Lyrem shot a quick wink to Persephone as a thank you.

“Which is why, I shall grant you eternal life.” Hades continued.

Lyrem looked back to him, and stammered.

“What- what did… Did you just say what I think you said?"

Hades nodded. Everyone looked joyful. Excited even. Lyrem could last forever- very nearly be one of them. Yes, everyone thought this to be a grand idea, except for obviously, Lyrem.

“When you die, I will refuse to take your soul. Every time without fail. You will forever grow old, then older… then older. And you will never die.”

“No.”

“Welcome to a lifetime of arthritis and aching legs and never-ending cataract surgery,” Hades said. “Oh, yes, that is right, Thomas. I know how old you are, and how much older you will get before your cells no longer hold you together. Consider this a gift.”

“No, please, God Hades. I need to find Ros-”

“Goodbye ‘Lyrem’. Have yourself a wonderful life.”

He was gone. All the mortals had left the Underworld, finally. Now, Hades could return to restoring his realm to its proper state.

Persephone perked up, realizing she was free to create and grow everything back to the way it was in the Underworld.

“My pond!” She cried, running out the dining room doors towards the Depths of Despair. “I swear, if Pan killed my koi, I am going to be furious!”

-----------------------------

“Why the hell are there empty bins in the hall?! Where are all my photos?! What on earth happened to my stereo?!”

Arch groaned, sitting up from the floor of the living room. Their mother was already back to her old self, standing and shouting and asking questions that no one would care to answer for her.

“I don’t know, and I don’t care,” Arthur answered. He stood to his feet and limped slowly down the hall. “I’m pouring myself a bath.”

Charlotte rushed past her brother and her child, throwing herself through the house in a frenzy. Arch stood with their back against the wall, arms crossed. It wasn’t anything defiant. They just wanted to be held.

“Where are all my clothes?!”

DING DONG

“Arch, I swear to God, you will tell me what happened while I was away, and where all my f-” ding dong “stuff is!”

Arch removed their bloody apron from their body, moved a short few steps to the kitchen sink and rinsed their hands that were still stained red.

DING DING DING DING DING DONG!

Arch rubbed their temple with their hands and out of instinct, walked to the front door.

It was Benji. Through the screen door, Arch saw him standing on the sidewalk in front of their house. He had just pressed play on his Bluetooth speaker sitting in the grass. It started playing a bizarre melody.

“Hey! You answered! I was hoping you would! You have no idea how many texts I’ve sent!”

Arch stepped out onto the top of the stairs, still puzzled to know what was happening. The summer heat still lingered in the air.

“Look, I don’t know what I did to deserve the cold-shoulder, but I thought you deserved a visit at least on your birthday, okay? So, sue me.”

“My birthday?” Arch said. “It’s… It’s August? Thirteenth?”

‘Me, my, oh, what a life So lean on my people, gon' be stepping in time��

“Yeah, dude! Did you seriously forget?!” Benji exclaimed, bobbing his head from side to side.

‘So, thank you!

For coming to my birthday party!

I am one minute old today

And everything is going great-’

Arch sputtered a reflexive, well-needed laugh. Benji had started dancing like an absolute fool on their front lawn. He pulled out a birthday candle from the recesses of his pocket and held it forward.

“Look, I’ve been wanting you to show me that magic trick again, I can’t stop thinking about it.”

Arch placed their hands in their pockets, trying to work past their tears of both exhaustion and entertainment. They shook their head. They really didn’t want to know if they could still perform that trick.

“I… forgot how.”

Benji stared back up, crestfallen. He checked his phone and lowered the volume on his music player.

“Fine, okay. Whatever. You don’t want me around. That’s cool. I get it. I’m a big shot. Not really your type to hang with-”

“What?”

Benji swallowed back his pain, and shrugged.

“It’s cool Arch. School’s over and we gotta go our separate ways. I understand.”

He started backing away. Arch leapt forward, and caught him by the elbow before he turned away completely.

“I want you to stay!” Arch admitted. “It’s totally cool if you want to hang out. Please stay... I… Honestly, I have been so lonely...”

How did the air get so thick?

“And I have missed you… so much.”

Benji’s sad, soulful eyes skeptically narrowed, and then widened with a realization.

“Dude… Have you been struggling? This whole time…? All summer? You gotta come to me with your shit! Don’t bottle it up, bud.” Benji wrapped them in a tight hug and rocked them to and fro. “Oh, I had no idea... You’re my main enby, Arch… I’ll be your Rick Astley forever… The Bernie to your Elton… Okay? Always. No doubt. No doubt.”

Arch took a moment to sob grossly into his shoulder. They pulled away before it got too squishy for their liking. If allowed, they knew Benji would let them cry on him until the end of time.

Arch took a deep breath of relief.

“Sorry, I’ve just been really stressed.”

“Yeah, hey. No kidding.” Benji said. “Look, here’s the plan, Shazia said that if I could reach you today that she’d meet us at the park with some of that fancy hash we like so that we can smoke up cakes.”

Arch scrunched their face.

“Cupcakes. Shazia would meet us in the park with cupcakes. Hey, Charlotte,” Benji cleared his throat, seeing the dark haired woman, who seemed to be hanging by a very fine thread from behind the screen door. “How are you?”

“I’m fine, Benji. Arch, just go.”

“Wait. Really?” Arch turned around, wondering how she could be serious.

“You’re eighteen now, aren’t you?” Charlotte asked.

Arch nodded.

“Then get out.”

There wasn’t anything warm about the way Charlotte said those words. Instead of lingering too long on the nuance, Arch only nodded, watching the door to the house shut its inhabitants in.

Benji bent over to pick up his speaker. He didn’t miss a beat cutting the music.

“What was that all about?” He asked. Like Arch, he looked up at the closed door.

Arch wiped the wetness away from their face with a couple fingers.

“I… I think I was just kicked out.”

Arch cleared their throat. They turned back to Benji as the summer sun beat down on them both.

Oh Benji. He was the most welcome sight in this world. The only good thing left that Arch had yet to ruin. Shazia would soon await them both in the park. Their life with Paimon, Lyrem, and hell, was now in the past. A future containing Arthur and Charlotte filled with shame and regret awaited them.

That didn’t matter yet. All that mattered was what was right in front of them.

And Arch really, really, really wanted to get high.

“Anyways, you said something about smoking up?”

#unsung hero: benji#drug mention#whump#urbanfantasy#fantasy#fiction#writeblr#finalchapter#mystics by alpaca#whumpblr#writing#creativewriting#completed projects#Lyrem oc#Paimon oc#Arch oc#dark comedy#tw blood mention#twdrug mention#nonbinary main character#nonbinary#greek mythology character#psychological whump#emotional whump#memory whump#AJR reference

5 notes

·

View notes

Note

About headcanons: Zeus' and Hera's relationship with their children (wedlock + Hephaestus)

Oh, this is interesting! Okay, let’s go in reverse order (I’m going to count Enyo as well as Angelos, but not Eris, among the kids):

Hebe is basically the apple of her parents’ eye. Both because she’s the youngest, but also for her shy, sweet nature. She’s very indulged, and it’s an easy relationship - mostly because she doesn’t have many or any expectations put on her, which means her ambivalence about getting married to Heracles hit both Zeus and Hera and neither really had a good idea how to deal with it. Not that Hebe got very obviously angry or confrontational about it, but the fact that she didn’t go easily along with it sort of rubbed both of them wrong (on the other hand, strange chance for Zeus and Hera to bond over it, haha). They got through that, even before Hebe relaxed and felt more positive about her new husband, though.

Angelos isn’t exactly a trouble-maker as such, but she deeply resents her mother for the fact that nymphs fostered her (not fully Hera’s fault; I am definitely into @a-gnosis idea that Hera suffers from postpartum depression to various degrees), and they never really get past that. Angelos acting out is what lands her in the Underworld, with Zeus basically putting his daughter in his brother’s care for safety’s sake. (Poseidon would’ve been the less radical option, but, uh, I don’t think Zeus would do that just for how Poseidon might latch onto it as a sign of weakness or something.)

Eileithyia has an okay relationship with Zeus, if a little distant - she is definitely mommy’s girl, so to speak, and she nearly always takes Hera’s side during arguments and similar issues.

Ares and Enyo were born as twins, and the problem here when it comes to Zeus with both of them, but especially Ares, before his honours and sphere was obvious, is probably because these two were Hera and Zeus’ first children and first son. There was a lot of expectations and desires here, and neither twin was actually very well-suited to dealing with that on top of that they’re both rabble-rousers and Ares has a temper. Ares is still (despite everything) the one who’s more attached both to family and his relationship with his parents, which means he’s the one who stays when Enyo finally has Had Enough, has a big, angry flounce and leaves Olympus (and stays away, though she stays in contact with Ares). Generally Ares’ relationship with his mother is better than with his father, but that doesn’t mean its perfect - Hera has no compunction about showing her displeasure if Ares goes against her. Something which probably makes those moments worse than Zeus’ constant low-level disapproval-disappointment that sometimes spills over into more obviously expressed dislike.