#but idk how to write it phonetically

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

friendly reminder that thais' name is pronounced tah-ish peh-droh-zu here in her country rio de janeiro

#the dr is not pronounced the english way either#but idk how to write it phonetically#thais pedroso#the wicked powers#tsc#the shadowhunters chronicles

58 notes

·

View notes

Link

Jazz ain't the smartest guy ever, but man he really beefed it this time. This definitely takes the cake.

Like, he's beefed it so hard 'beefed' doesn't even begin to cover how badly he's whiffed this one.

Y’all ever get sucked through a wormhole and then immediately just make assumptions and get distracted by a cool guy in a mecha suit? Then ya start dating the cool guy in a mecha suit and then ya realize oh shit he's not in a mecha suit-

#idk what im doing#based on an au#tumblr user keferon ur aus itch my brain#i got no idea how tumblr works#jazzprowl#i used this as a flimsy excuse to try writing sylistically#i did write jazz's accent out tho so like beware if u struggle with phonetic accents#mecha pilot jazz au#tf mecha universe#mine :3

85 notes

·

View notes

Text

I have been thinking about this video nonstop since I first saw it on Instagram. I hope everybody has a very happy tuchus!

[Video ID: A Jewish woman (Rabbi Yael Buechler, @midrashmanicures on Instagram) speaks to the camera: We have reached a new low in holiday product fails. This treat box is for Sukkot. It's featured on Amazon and Sukkot is a holiday that doesn't get a lot of love so kudos for having a product for Sukkot. It says Happy Sukkot and in the Hebrew it says--wait for it--tuchus! Happy tuchus! Tuchus is Sukkot spelled backwards. The product clearly wasn't vetted in the Hebrew. This other treat box just says Tuchus. I'm thinking we should create some sort of governing body that "certifies" Jewish holiday products as being "kosher" because this is a new low. Anyway I want to wish you all a very happy Tuchus." The first box she shows is pale green decorated with images of apples, pomegranates, and branches and the words "happy sukkot" and תוכוס. The second treat box is pale orange with a similar motif and the word תוכוס. End ID]

#Sukkot#tuchus#Hebrew#language fails#Hebrew fails#Yiddish#Jewish#Judaism#Jewish things#video#Instagram#happy tuchus#in case anyone was wondering that is NOT the actual spelling for tuchus in Yiddish BUT it does in fact phonetically spell out tuchus#I really don't understand how people keep winding up writing these things backwards#because if you look it up...shouldn't it be written correctly? and shouldn't you then write the letters as you see them in your source?#like. even if you physically write it left->right shouldn't you still be writing the letters in the right places?#she has a couple of other product fails videos including one for a pop-up sukkah that says (in Hebrew) 'Hanukkah happy' (שמח חנוכה) on it#maybe I'll post that one too idk#midrashmanicures#Rabbi Yael Buechler

70 notes

·

View notes

Note

Top five animals, Sadie. I trust you.

I can’t count

#FROM LEFT TO RIGHT -#Muileach and Panda!#Parsley!#Ossie!#aaandd#Collach and Liosach!#I’d write out the Gaelic names phonetically but#they have sounds that don’t exist in English#so idk how#ask game!#ty for the ask!#smartheart#top 5 ask game#Srry it took so long to answer this ask game stuff lol#I have no excuse

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ah, yes, Nelly Furtado's hit song Anteater. In completely unrelated news, several people have told me that I might be slightly dyslexic.

#shitpost hours but also this one's lowkey serious😭#I'm mostly bad with acronyms and double-letters but sometimes regular-ass words trip me up. like maneater apparently.#I can read and write just fine but stuff gets inexplicably mixed up here and there.#The bane of my existence is NDA and DNI though. they're not even that similar. idk.#actually homophones aren't- by jove! I've summoned an ant. there is an ant on my desk.#anyways homophones aren't fun either. I write things as I hear them in my mind and sometimes my brain chooses the wrong one.#I know the difference between them! It's not a lack of understanding. I know my its/it's and to/too/twos etc.#but when I try to get them down on paper something just goes wrong and I end up with the wrong one. and I KNOW it's wrong. alas.#even with super easy ones like flour and flower. obviously I know the difference but there's just a disconnect when I go to write it.#it's never been impactful enough for me to actually get it checked out but it is annoying.#if anything it impairs my ability or total lack thereof to do math over linguistic stuff but that's a whole other thing.#the ONLY way math makes sense to me is the way you'd put it into excel. i can put in horizontal stuff with brackets#but I could never do vertical math like they teach you in school.#even with a calculator. I cannot go downwards with it. my brain just doesn't compute it.#it's like reading other phonetically-similar languages as an english-only speaker.#you can recognize each individual letter (read: number) but putting them together doesn't get you very far.#you might even be able to pick out specific parts but you don't know the grammatical structures behind it.#that's how math has always felt to me.

6 notes

·

View notes

Note

“Bostonian yaoi” one of the funniest tags to ever do it

bostonian yaoi is everything to me <3 they are getting 2 iced regulahs and 1 strawberry frahsted. to shahe.

#gale answer#that last word is supposed to be share idk how to phonetically write out the accent#i guess i could do. shayuh. but that's more mainer.#masshole

8 notes

·

View notes

Note

How is your name even pronounced?

That would be “care-ee-ehn”.

#carrion speaks#(if this is the incorrect pronunciation blame myself HAHAH)#(also I’m sorry if this is unclear idk how to write out like. phonetics 😭😭)

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

do any countries other than the us spell mum as mom ?? i feel like canada maybe does but i’m curious about it especially in countries where the word for mother is completely different like. if you learn english as a second language are you taught u or o ? and i think actually in ireland it’s sometimes mam ?

#i realised that i’ve shifted from writing mama to mumma when i text my mum and idk why#i think it’s just closer phonetically to how i say it???

1 note

·

View note

Text

i’ve been binging fargo and the minnesota accent is driving me insane but my ear isn’t good enough to know if it’s actors with other accents butchering it or of it’s just. like that.

1 note

·

View note

Text

me, scribbling furiously in my sketchbook all of the answers to my plot problems: yes YES Y E S

#silly phonetic#idk how to write dick grayson tho so now im procrastinating ;w;#i have so much built up art for my own fic i cant post yet because SPOILERS it kills me dead

1 note

·

View note

Note

I wanna have a small vent, if I may, because the thing that’s on my mind is completely a me problem and not something I can ever comment on a fic because it’s not necessary or kind, but gah it’s winding me up and idk if it’s just me being too petty or if others feel like this too.

There’s a few authors I like - they tell good stories with good writing - but who each have some really small, specific quirk in their writing and I just can’t make myself get over it and ignore it. I do a double take every time. One example is someone who writes “em” instead of “erm” and uses it a lot. Another is someone using “..” instead of “…”. Another is their particular use of dialogue markers (idk what to call them, things like “he said”).

It shouldn’t bother me this much. I’m never gonna comment on them to the authors. I keep reading because everything else is good but they come up in every fic by those people. I just can’t seem to stop my brain noticing Every Single Instance of the Annoying Quirk and briefly taking me out of the story. I have to actively pause and take a deep breath sometimes to calm down which just sounds ridiculous over the use of “em” instead of “erm”. Is it just me?

Yeah that happens sometimes, I work as an English tutor and comma mistakes always jump out at me when I read, I sometimes have to remind myself that it’s really not that serious

“Em” vs “erm” might be a phonetic spelling of a dialect or the authors regional accent. Such as how my midwestern friends might text: “ope! Gimme a sec, okie?” In stead of “oh! Give me a second, okay?”

75 notes

·

View notes

Text

Haikyuu boys as tiktok pranks

CHARACTERS: Nishinoya & Kenma,

a.n. As always - requests are open! It's been so so long and I feel like I'm in lockdown again but the Haikyuu phase is strong as ever. Enjoy!

NISHINOYA YUU.

"Would you still love me as a worm?"

You shifted in his arms slightly. "Mm, yeah probably. Depends how long though."

You felt him nod, his chest rising and falling in time with his slight laughter. "Well, probably forever. It's kinda a permanent situation-"

"No, Noya, I mean how long the worm is."

A few moments of silence passed before you continued. "Well, I suppose you're on the short side anyways so you probably wont have to worry about it."

He sat up, almost knocking you off the couch. "Probably?! And what do you mean I won't have to worry about it?? I'll be the longest worm ever and you'll hate it."

Frowning, you maneuvered yourself off his legs and onto a more stable part of the couch. "Um, no, you'll be teeny tiny and I'll love you forever and keep you in a little bottle cap."

He mirrored your frown, and pointed at you. "You will not keep me in a bottle cap, you'll have to get a, like..." He faltered, making wild gestures with his hands. "...a jar or a skyscraper or something."

"Dont point at me! You're actually so wrong, you'll only be this size." you loomed toward him, showing him the tiny distance between your thumb and finger. He gasped dramatically and clutched his heart, before retaliating once more.

It was very likely that this quarrel would continue for at the very least, another half hour or so, but likely the worm references would continue for the next few weeks, confusing anyone who tried to understand what you were even arguing about anymore.

KENMA KOZUME

(Laughing like spongebob at him)

"So then Kuroo had to spike but completely missed, he slipped and fell just like-"

"blahahahhahahaha" (chat you know what i mean idk how to write spongebobs laugh phonetically)

Absoloute silence. Kenma turns to look at you with literal horror and fear etched across his face.

"....what was that?" he asked incredulously. "Did you just - was that a spongebob laugh? How do you even do that?"

"blahahahaha ! Stop, Kenma, you're so funny I don't know what you're talking about" At this point he was standing, head tilted and a look of pure shock and disbelief. "No. No, I'm not doing this."

You watch him get up and head for the door - "Wait, wait, Ken I'll stop, promise" you gasped between fits of laughter, in some attempt to bring back your terrified boyfriend.

After some coaxing, he sat down on the bed a good distance away from you.

"Promise you won't do that ever again."

"Aww, I promise."

"I'm serious, y/n! That was like, inhumane - no human should make that sound."

He flopped back onto the soft duvet, looking genuinely stressed. "I actually think you triggered my fight or flight response or something, that was messed up."

You sidled up beside him, wrapping a comforting arm aound him. "Don't worry, we're all afraid of something, Kenma."

"I am NOT scared of spongebob! I honestly think I'm scared of you now, though."

#Ty paul and morgan on tiktok for the inspo my fav british ppl#yes i intended to include oikawa... yes i gave up#But yes there will be a pt 2?#nishinoya x reader#nishinoya x you#nishinoya x y/n#yuu nishinoya x reader#hq nishinoya x reader#hq nishinoya x y/n#haikyuu x reader#haikyuu x y/n#haikyuu x you#haikyuu x gender neutral reader#kenma x reader#hq kenma#kenma x y/n#kenma x you#hq kenma x reader#haikyuu kenma

174 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hermaphrodite but it's pronounced like Aphrodite is that a thing if not I'm making it one but idk how to write it

Hermaphroditi could represent the phonetic sound however it's Latin and doesn't sound the same

Hermaphrodit is technically the German word for it that doesn't sound the same

Herm/Aphrodite ?

Herm-Aphrodite ?

#slur reclamation#tw h slur#h slur tw#h slur mention#h slur reclaimed#h slur#aphrodite#intersex exclusive#hermaphrodite#herm/aphrodite#intersex term#intersex mogai#mogai intersex#mogai terms#term coining#intersex thoughts#intersex things#intersex#Herm-Aphrodite

62 notes

·

View notes

Note

new to the fandom, hello. i've seen a few posts on your blog about blitz's bad spelling being rooted in dyslexia, however i've noticed that all imps seem to have bad spelling, all the way back to flashbacks of the circus.

one could argue i suppose that spellings seen at the circus are written by his dad, and that dyslexia runs in the family. but i think the consistent imp misspellings are intended as another indication of how lower class imps are - that they are uneducated, perhaps not allowed to receive education, and thus don't know *how* to spell.

Welcome. I disagree, and I think you expected that.

I'll start with the claim you based everything on.

"I've noticed that all imps seem to have bad spelling, all the way back to flashbacks of the circus."

Now, I really dug. And I could only find one example of something spelled incorrectly in any of the circus flashbacks. This is from "Oops."

Okay. Someone spelled fireworks comically wrong. My bet is Cash (whatever the cause), and idk... we haven't seen a pattern. Just the one example. Maybe he's dyslexic too. Maybe he's poorly educated (more on that later). But that would all be more in the headcanon realm for me.

Other things are spelled correctly at the circus.

The only other non-Blitz example of an imp being unable to spell something is Striker in "Mastermind" struggling to spell/say grimoire. But who can blame him? I struggle to spell grimoire, and I'm a human with a masters degree.

Beyond that, Fizzarolli, Millie, and Moxxie (you know . . . all the secondary imp characters) are shown spelling things correctly.

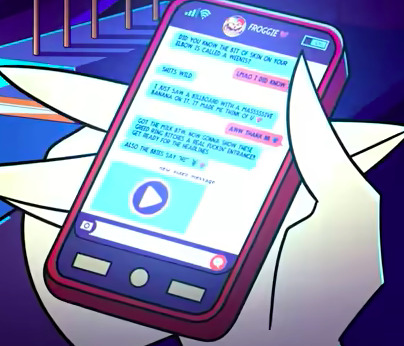

Fizz uses shorthand and repeats letters for emphasis here and there, but all of the words that he fully spells out are spelled correctly. There's nothing that can really be called a spelling mistake here.

The same can be said about Millie's texts in "Seeing Stars." She uses shorthand, but it seems intentional. You can compare her spelling to Blitz's directly here. "Mackin" in this context just doesn't have a slangy/shorthand explanation in the same way. Neither does "were" for "where." This is because spelling is automatic for Millie, but it isn't for Blitz. He's using phonetic(ish) guesses.

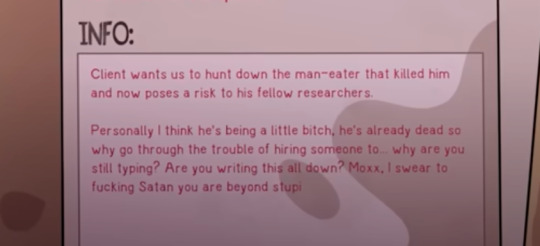

We also have Moxxie writing down a report that Blitz dictates in "Mission: Antarctica."

The guy can spell perfectly.

But-- honestly? You only have to be familiar with Moxxie as a character to know that his spelling would be flawless . . . For example, look at how he calls Blitz out for his spelling and grammar in "Spring Broken."

Blitz is the ONLY character with a recurring pattern of poor spelling. And if the writers didn't want us to make something of it, they wouldn't keep showing it to us in almost every episode. Now his spelling isn't always bad (he does alright in his apology notes and then in his reports in the shorts- IF Moxxie isn't still writing for him). And I wrote a piece of meta here that explains why I think it might show a form of self-accommodation that's super common for people with learning disabilities.

Now. I'd like to talk about imps and education briefly. Yes, imps are marginalized by their society, often poor, and expected to work for higher demons. But I don't think they have it much worse in terms of education and daily life than say . . . marginalized people in today's real life societies. Their roles are more rigid, yes, but they do hold a range of jobs and participate fully in demon life in multiple rings of Hell.

Are imps on average less well educated than demons higher on Hell's hierarchy? Yes, I'm sure. But remember, Blitz tells us he dropped out of a college, and for that he'd have to be . . . you know, allowed to start at one. And we see imps being very competent consistently. I haven't seen anything that suggests that they're not allowed to be educated (though they're pretty clearly not allowed to access magical artifacts), so I suspect that most imps receive a basic education.

Now do some marginalized people in real life end up illiterate (completely or in part) either because their education is horribly disrupted or inadequate or because they have a learning disability that isn't properly addressed? YES. Do some people with dyslexia still struggle to spell in daily life even if they're well educated and absolutely literate? Also yes.

Imps have a range of experiences in a society that is complex (even if it's in the process of being fleshed out) and reflects our own in many ways.

Blitz is dyslexic. Thanks for reading.

#asks#my helluva meta#blitz#blitzo#blitzo buckzo#helluva boss#helluva boss analysis#helluva boss meta#danny? this you?#this is my bitchy nerd mode

76 notes

·

View notes

Note

favorite word?

hi! you know, i listen to a shit ton of music, but i can't really say i have a favorite album or song or band. similarly, i'm a linguist, i literally study words (eventually for a living), but i can't say i have a favorite word.

did you know linguists don't actually really believe in the existence of a "word"? at least, we can't define it. think about it -- what is a word? you could say "well, they're separated by spaces", but that implies that languages without writing systems (which definitely exist!) don't have words. or even that languages whose writing systems don't use spaces don't have words. we definitely don't want to say that. there are no phonetic cues for a word either -- language is pronounced as if it's all one big "word".

but it's still an important concept -- perhaps most of all in phonology, the study of sounds and sound systems in language. we know that the concept of a "word" is important in phonology because we see interesting phenomena at "word" boundaries, such as certain sound changes or changes in prosody (intonation and etc). and yet we can't actually define what a "word" is, to make these observations have more scientific grounding. perhaps the existence of these phenomena is, in fact, the definition of a word. "a word is defined by potential sound change at its periphery". but then how are we to distinguish those sound changes from all other sound changes that do not depend on a word boundary?

you'd think this poses a big problem for linguistics as a study, and maybe it does. maybe this is a massive flaw in the foundation of our field. but we have ways of getting around it. in syntax, we have syntactic items. which often are "words" ("which", "often", "are", and "words" are all syntactic items), but don't have to be. "n't" is a syntactic item. possessive " 's" is a syntactic item. even silence can be a syntactic item, unspoken and unheard in speech. in morphology, we have the concept of a morpheme. "cat" is a morpheme, but the plural suffix "-s" is a morpheme. "cats" is NOT a morpheme -- "cats" is two morphemes. in semantics, "to" in the phrase "i give the book to you" isn't really a "word", in fact, we often say that it doesn't have any meaning it all. it might as well not exist.

so. idk, but like, ig a good one is uhm. oblique? just sounds nice idk. it has a specialized meaning in linguistics and i just looked up what it means otherwise and apparently it has a lot of definitions all with radically different meanings. lol

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

A slice of swapped life. Day 17. Swapped people often enjoy the little things that the other would totally take for granted. Even if that little thing is being unable to manipulate little things because the paw too damn big.

I forgot to account for Manya's accent last time. I've since decided that accents stay with the body (since it's kinda physiological, whatever) and diction stays with the mind. So they sound like the other, but talk like themselves if you know what I mean. idk if it's considered corny to write accents phonetically, but I like it as long as it's not overblown.

The dates are ambiguously canon and more for flavor and a sense for how long they've been swapped.

25 notes

·

View notes