#but i treat them as very 'real' (which this can be another tangent in itself) and intuitive is the best way to describe how i process them

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

reblogs off bc i dont want to start Conversations based on other peoples posts but re the whole "who is in control you or the character" question, i find it SO interesting because it's by letting myself discovery write that I (for me personally disclaimer) found the perfect balance between intuition and intention. which to preface "intution" is the easiest way to describe how the inside of my writers brain feels bc often i just get vivid characters/stories/images/scenes with little control at first and i have to figure out what they mean. anyway discovery writing is what works for my brain to make intentional decisions because i need to be amidst a draft to get the Story Cogs working, whenever i try to outline before a draft it's always been just throwing things at a wall bc it feels too far away, but because im also using the discovery element to do that it's like. that's where i think the whole i feel like my characters reveal themselves to me comes from. because im always discovering small bits about them even if i've written them for years just but because discovery writing is also what prompts me to be intentional about writing as i write something it's like both are happening at the same time. so the whole "who's in control" it's like...i don't think control is the right word for me at all because its not Me or the Character it's me trying to understand the character to understand + then write my intentions. like neither me or the character are in the drivers seat because there's no car we are in the middle of the story forest and at first i won't know what it means at all except that it is a Story. and my character will start going one way and sometimes i'll follow and pay attention to where they're taking me to figure out if this is the right path/where to go next. and sometimes i'll figure out how to read the compass first and realise i need to drag their ass in another direction

#anyway i just thought this was interesting because i used to think i needed to outline to be intentional/in control of my story#but outlines are too distant for me to feel like im in control so thats why theyre more organisational than creative for me#whilst we're infodumping on process i also dont like the whole are characters Like Real People or just Story Tools#like yes my characters are tools for the story just like how the story is a tool for demonstrating my characters#like again i dont think its one or the other for me#but i treat them as very 'real' (which this can be another tangent in itself) and intuitive is the best way to describe how i process them#but that doesnt mean there isnt intention and control you know#like the reason i describe my characters and stories as 'real' to me is simply bc they are very vivid in my brain#and that vividness often expands the bounds of the story#i want to go on the 'real' tangent the weight of that word one day#i think this makes sense if u know that for me i rarely get 'ideas' i get images#and characters/relationships#and i have to figure out what that means as a story#also no i dont think you need 'intuition' bc thats just the word i use for myself but i do think you need to understand#how intention works w your writing process and what it means for you to be intentional and what helps you be intentional#and sometimes that will be not considering any form of 'intuition' at all#beloved writeblrs i think i need to launch the dallonwrites substack i cant be doing these tag essays anymore!! i need to expand!!! someone#give me a podcast

10 notes

·

View notes

Note

If you’ve been around for a while this user may cause some ears to perk because they were involved in drama a while ago involving “inserting proship propaganda” into the Kirby tag. I didn’t say anything about it when it happened because I wanted to stay neutral and drama free but that ship sailed a long time ago so it’s time for me to talk about my opinions here because I think “antis don’t interact pros don’t interact” is not enough to explain my feelings on this. Sorry Mini for using your post as the starting piece.

I personally hate the proship antiship discourse. I understand where this comes from but when the most openly proship people I’ve seen as gross and creepy and the most openly antiship are…really insanely aggressive and they seem to harass and shout more death threats than the average Xbox kid (which if ur a CSA survivor and are mad at this lenience on pedoshit then that’s somewhat understandable but should perhaps be expressed in different spaces) I tend to stay far away from the war grounds. But if I had to be defined by one of these I’d be antiship.

Also the definition of both sides has been oh so muddied over the years to where if you asked anyone to define it you might get a range of answers. So here’s my stance on this.

Shipping adults with kids is cringe and if you do this I’m calling your ass out (This includes SOME child-coded characters I’d recommend Noralities YouTube video on it it’s really good). No romanticizing pedophilia.

Shipping kids with kids is fine as long as it is not portrayed as nsfw or raunchy. Treat it respectfully and innocently or I will also call your ass out. Aging both kids up to adults and shipping them is fine (I kinda do that? Considering Nextgen and how that works).

Shipping like- actual animals with people is not cool. Like if you wanna ship ur human sona with Zootopia Fox guy it’s whatever it’s an anthropomorphic Fox with a human personality and does human things. It’s when like- you ship a very obviously animalistic creature with no real knowledge of consent with a human. Oh yeah as here’s a cool factoid. Zoophilic thoughts and tendencies have been recorded to be signs of psychosis. So yeah it’s not cool it is basically mental issues.

Shipping abusive relationships in a romantic way and portraying it as sexy or cute isn’t cool either. I’m looking kinda at you, Helluva Boss.

Aging up a young character to ship with an adult character is really weird and I’m not going to affiliate with you if you do that. Aging down an adult character to ship with a young character is equally weird.

I’d also like to go onto another tangent because I think romantically pairing characters are writing couples are a little different. I’m a Berserk fan so I feel the need to say this.

It’s fine if not important to portray things like abusive relationships, pedophilia, zoophilia, CSA, etc in media and art. Just make sure to portray it with the respect and care needed as these are very sensitive topics that will always sadly exist in real life. They may be portrayed through the lens of an artist who actually suffered from these things or something similar to a PSA, maybe even just a portrayal of what really happens and negatively affects a character. These portrayals may have people who were genuinely affected by these things feel represented and heard and also help others be aware of these things and how horrible they can be or even avoid future encounters with these gross things.

IF you are someone who uses these things to cope with trauma, label and make due with warnings as this stuff is sensitive and not everyone is going to want to see it.

And for those of you who say, “well it’s not illegal so it’s not bad” like an idiot…

JUST BECAUSE IT IS LEGAL DOES NOT MAKE IT MORAL

Thanks for listening to my horrible rambling and make sure to block the aforementioned account that calls itself a proshipper.

Edit: Also to add on from what I’ve seen in tags, Fiction does absolutely affect real life, there are so many examples of it as that excuse will not work either.

Quakey

There's a proshipper named princess-yurioangel going around, be careful

Oh God, blocked them immediately thank you so much for telling me

146 notes

·

View notes

Text

This is the third time this week.

The Archmage of Civil Influence sits slumped over her pristine, deep red desk with her head in her hands. She can handle Ludinus. The man gives her a long enough leash, so long as she gets the right things done with it. She can even handle Professor Widogast, absurd as his new name might be, tiring as his constant pushing of the line between acceptable lesson plans and light treason might be. No, it’s not him. It’s his friend.

“Hi, Astrid!”

She presses her fingertips into her temples. Twenty-five words feels like more than one might think. Twenty-five and then twenty-five more and twenty-five more and on towards infinity feels like an eternity. Occasionally, for a while after Ikithon’s trial, she had received a friendly hello from Ms. Lavorre. That had been irritating enough. But from what she understands, the tiefling and two others are now at sea dealing with their own issues.

Veth Brenatto, on the other hand, seems to have absolutely nothing else for which to use her spells.

“How ya doing? Just checking in about that little get-together we talked about.”

Talked about is a generously mutual way to put it. There is an event planned for the end of the week at the dance hall she and Bren used to frequent. Brenatto is of the persistent opinion that she ought to attend with Professor Widogast. As his date.

Ridiculous, as she had snapped to Eadwulf last night, because if anything he would be her date - but that is beside the point.

“I know Caleb is waiting to hear a ‘yes,’” the voice in her head continues in its usual overly chipper tone.

Astrid does not believe for a second that “Caleb” is doing anything of the sort. They pass one another in the halls of the Soltryce occasionally, and their interactions are always a coin-flip between professional and very awkward. The only other time they see one another at all is when he’s dragged into her office for going on one of his famous little tangents in class, and he hardly seems interested in her authority, let alone her companionship.

“Good afternoon, Frau Brenatto,” she says smoothly, thankful that the woman can’t see her face. “As I have previously informed you, I would be happy to discuss this with Bren himself. Do have a pleasant day.”

She hopes it sounds sufficiently final, but allows herself a sigh as the halfling’s voice filters back into her mind a moment later.

“Caleb is very shy,” she says. “I think you intimidate him - which is silly, because he’s extremely powerful - but if you could just give me your answer--”

Astrid cups her face in her hands, fingers splayed. Only three more days until the dance has come and gone, and then she won’t have to deal with this anymore. Until the next time, of course. Or until Brenatto comes up with some other pretense to push them at each other.

“As I have said,” she says pointedly, “I would like to be sure that this invitation is coming from Bren. If he wishes to speak-” and he will not- “then we may.”

The next message is almost immediate this time, and Astrid resists the urge to bang her forehead onto the desk.

“Why don’t we go visit him together?” Brenatto asks with renewed enthusiasm. “Have some lunch, talk a little… I can leave you alone, if you two lovebirds are getting--”

Never before has she been so grateful for the limits of a Sending spell. She clears her throat, eyes falling on the stack of paperwork waiting in front of her. There is actual work to be done. Actual important work that does not involve a halfling jabbering in her head all afternoon. And, well, if confronting Bren directly about this nuisance could put an end to it?

“Very well,” she says on a sigh. “When shall we meet?”

Astrid wants to groan out loud at the ecstatic tone of the next message. They plan to meet tomorrow evening. Brenatto is already in town, for some reason Astrid doesn’t bother remembering, and they’ll arrive together at Bren’s little residence on the outskirts of the capital at sunset. Ostensibly, Veth will treat them all to a meal at Bren’s favorite establishment - but Astrid suspects things won’t get that far.

At least she can finish her paperwork, now.

She buries her face in Eadwulf’s shoulder that night and groans, “Why does she never do this with you?”

The following evening, she finds Veth Brenatto on the road outside Bren’s place, waving on her tiptoes with a wide grin splitting her face. Astrid gives her a tight, mirthless smile in return. Better to get this over with.

“I’m so happy that the two of you are getting some proper time to get to know each other again,” Brenatto says as they approach the door together.

Astrid will ignore the suggestive tilt of her eyebrows.

Bren’s place is smaller than those of most of the Academy’s faculty. He is one of the only professors who has chosen to live outside of the city center, opting instead for a little-travelled section of Rexxentrum to the northeast. The house itself is small and nondescript; she would never have picked it out, if she didn’t already know it was here. Astrid wonders sometimes about the secrecy, but she will let him have his privacy. She owes him that much, at least.

She shakes herself from her thoughts just in time to notice Brenatto reaching for the doorknob, but not soon enough to stop her from opening without a single knock. By the time she’s reached out to stop her, the door is already wide open.

And oh, this is rich.

“Caleb! I brought--” And then Veth sees them, too.

The man in question - Caleb or Bren or the physical manifestation of regret, whichever he pleases just now - has just fallen off the couch. Brought tumbling down with him is the drow with whom he’s intimately tangled up, face twisted into such a comical mix of shock and mortification that Astrid actually cracks a smile.

“Ah,” Bren says, pulling a blanket from the sofa to wrap around his partner’s shoulders, “Hallo, ja, come right in.”

The drow, for his part, has already waved a hand and magicked them both some clothing. Brenatto, for hers, has begun sputtering incoherently - which, after the week of endless pestering Astrid has had, sounds about like music. Astrid gives her a smug look, and gestures with one hand towards the two men hastily righting themselves.

“I believe this settles the matter,” she says coolly. “Thank you for the invitation.”

She gives Bren a knowing look, and he gives her a tired nod back. She doesn’t envy him the interrogation he’s about to endure. With a parting glance at the drow, who has retreated toward another room with his real clothing clutched just a bit too tightly in his hands, she turns on her heel and steps back out into the dusk.

That explains the secrecy, then. She hopes he’s good for Bren, whoever he is. He deserves something good.

Just as the teleport whisks her away, she hears Veth Brenatto screech, “Him?!”

#this has been kicking around in my head ever since the week of the finale#very silly but hey#shadowgast#astrid beck#veth brenatto#caleb widogast#essek thelyss#mine#mine:fic#also i feel like i should say: yes i am aware astrid and essek were in the blooming grove together for a While#but astrid was pretty preoccupied so i'm playing with this anyway#astrid#veth#caleb#essek

701 notes

·

View notes

Note

do any of the mercs play board games?

Mercopoly (Board Game

Headcanons)

Scout:

You think he has enough of an attention span to play something that doesn’t involve sweating out his energy drinks?

Hell no!

He gets very bored very quickly, especially with something complex like chess.

He’ll play cards sometimes, but only Crazy Eights and Go Fish - that’s all he knows how to play.

However, there is one true board game he plays occasionally: Candy Land.

It’s one of the few board games that you don’t really have to read the rules for, and there isn’t any writing on the cards.

However, he only asks to play it when he’s not feeling very well.

Medic even has a page in his medical journal for the mercs that says, and I quote:

“The Scout has an extremely short attention span, and if an activity isn’t active or immersive, he will not stay long. If at any point he chooses a sedentary activity, a check-up is in order.”

As sad as it is, a request to play Candyland is a good way to know if Scout needs a little extra reassurance or support.

By the end of the game, Scout usually feels more himself, whether he wins or not.

Engie is especially good with Scout when he’s this way, being the one of the most emotionally sensitive of the group. But he also knows Scout would never admit straight-away how he was feeling, so he usually has a more fun way of getting answers.

“You feelin’ more like a King Candy or a Lord Licorice?”

“...Fudge Monster.”

“That bad, huh?”

“Yeah...”

Spy:

If you ask him, he will most likely go off on a tangent about chess, and how it’s a game of strategy, deception, and crushing your enemy with your wit.

He scoffs at any other game, and constantly makes fun of several of his more intelligent peers for finding interest in them.

“You are mercenaries. Blood-thirsty killers of men. And you are playing ‘Hungry, Hungry Hippos’ like a hoarde of kindergartners?”

But one thing he cannot resist is Sorry.

He considers it above normal board games because it has strategy - or at least that what he says.

He actually just likes it because it’s a game of revenge, which is like a drug to him.

He’s gotten so good at it that if he asks you to play Sorry with him, it’s almost guaranteed that he’s mad at you and just wants to let off some steam by giving you a horrendous loss. However, occasionally, he’s the one who loses.

Spy isn’t a poor sport, exactly - he’s too cultured for that - but sometimes his pride outweighs his manners and he convinces himself that the other player cheated through made up signs of deception.

He simply “allows” them to win because he “doesn’t want to make a fuss.”

But god help the unfortunate soul who decides to rub their win in his face.

Sniper had won five games in a row, and it was clear Spy was getting hot under the collar.

Sniper ended their games with a mischievous, “You’ll get ‘em next time, tiger.” and a small pat on his shoulder.

Spy immediately saw red, grabbed Sniper’s hand, and before the aussie knew it, he was against a concrete wall with a butterfly knife to his throat.

“I could kill you right now. Your final cry for Medic will be drowned in blood, and I would leave you here to die a painful, dramatic death. You’ll be replaced with a rusted trash can of a bot until they could grow another clone of you. Every memory will be gone. The team will be shrouded in grief, not because of losing you, but losing what the clone can never have. And I shall bide my time, ask the clone to play the same game, and kill them when they win. Another clone, another kill. And again. And again. And again. You think the Manns give a damn as long as their work is getting done? You will never be able to form a single thought before I spill your blood - caught in an eternal prisoner’s dilemma where you always lose.”

After gathering his bearings, Sniper finally spoke.

“Is this about your takeout?”

Spy scoffed.

“Do you really think - !”

“Tonight, my treat if you don’t kill me.”

Spy squinted.

“Egg rolls?”

“And an extra order of crab rangoon.”

“Your treat?”

“Yep.”

“How do I know you won’t poison me?”

“Chemical test before and after the food arrives.”

“How do I know Medic isn’t in on it?”

“Miss Pauling as a witness and Scout as an overseer. Pauling’s main objective is to keep us alive, and Scout can’t do bloody anything subtle, even if he wanted to. You can also play back the cameras in the lab, if the mood really struck ya.”

Spy held Sniper against the wall for a minute or two while he thought it all over, then let Sniper fall to the ground.

“I don’t need your sympathy, bushman. But you had better keep your end of the deal. I am the only backstabber around here.”

Demo:

Can’t even stay awake long enough to play most board games.

On the rare chance that he’s sober, he, Engie, and Medic like to play Monopoly.

Here’s the thing: you should never ask a drunkard, an engineer, and a sadist genius to play Monopoly together. It will not end well.

They have been playing the same game for years, with new rules in place and physical extensions to the board in order to try and end the game. Every other Friday, they take the weekend to try and finish it.

However, it all ends up fruitless.

Demo is usually the one keeping the peace, since he is the least competitive out of the three. That isn’t to say he isn’t clawing for the win as much as the other two, but he is definitely the least invested. He’s mostly staying out of principle.

“If there’s one thing I’ve learned, ‘s ta ne’er give up, e’en when the goin’s gettin’ tough. Roll the dice, doc.”

Despite his confidence, he’s not even sure what he would do if he or anyone else won. It would seem more like a relief than a celebration.

Medic:

He’s the one who started the Eternal Monopoly game, which has led to some theories that the game itself came straight from hell, and is one of the many punishments used on sinners. The box does smell a bit of brimstone…

He seems to enjoy the chaos that each round brings and the challenge of coming up with new rules to the game. To any outsider, his commentary and directions are complete nonsense.

“According to zhe ‘Calvinball Rule,’ as stated by Engineer, and the ‘Double Kill,’ as stated by myself, since the current time ends vis a three and ve all received at least two kills zhis veek, ve need to double every other roll and whomever loses zhe resulting game of ‘Bim Bum’ vill have to go to zhe Purple Jail.”

The rules and mechanics are like an unholy amalgamation of Monpoly, Sorry, chess, D&D, Bluff, and poker.

However, when Medic isn’t stapling pages of rules together, he likes to play a nice, relaxing game of checkers with Heavy.

Both of them are excellent checker players, but neither of them care who wins.

In fact, they usually talk over the game, taking the other player’s pieces as one of them shares a story from that day’s battle.

They’ve even played while Heavy was in surgery - leading to many unfortunate times when Medic had to fish a piece out of Heavy’s intestines.

One would think that a genius doctor would also have a passion for chess, but he expresses his disdain for it almost every time the checker board is brought out.

“Ach, people think chess is such an intelligent sport. Let me tell you, liebling, it is terribly overrated. If zhe devil can play chess, anyvun can. He might as vell just give souls avay, vis those shaky claws of his.”

Engineer:

Being the engineer, he is usually the one to add to the Eternal Monopoly.

Pieces, board extensions, cards, trivia - it gives him a nice break from all the weaponry.

He’s usually the one who remembers all the mechanics and rules, and serves as the judge if rules contradict each other.

“Alright, now let’s see here…we’ve got the Infinity Loop over here, but now you’ve got the Time Travel card…how many years? Infinite? Ho boy…looks like I’m gonna have to add a Hilbert’s Hotel square somewhere. Hold on…”

Despite his affinity for Eternal Monopoly, Engineer will play almost any board game. He learns new rules and figures quickly, and enjoys the challenges that brings.

However, if he’s particularly burnt out, he likes to take a break by playing Jenga. He and Spy have a friendly rivalry, since Engie can tell which blocks are supporting and Spy has quick fingers.

Spy, oddly, is a lot more amiable losing in Jenga - he knows Engie won’t think less of him - but Engineer hates when the bricks fall over. Not because it means he lost, but because, to him, it’s a failure on his part…even if it was someone else that knocked it over.

He’s made several blueprints for the perfect Jenga game, but has concluded that no human hand could put it into practice.

During one particularly bad day, Engie bumped the table, causing the whole column to come crashing down. Spy had already recovered from the noise, but Engie was still standing there, stone-faced.

His eyes were covered by his goggles, but it was clear he was crying.

Several of his machines had broken on the job, and to him, this was just another egregious mistake.

Spy carefully put the blocks back in the container, and Engie came to his senses.

“I’m real sorry, Spy. Maybe another time…?”

Spy only nodded. He was thinking.

The next time they played, Spy brought out a different container.

Instead of wood, the bricks seemed to be made of a sturdy foam.

“They fall a bit more…quietly,” Spy explained. He dropped one, and it only made a small bouncing sound. “Pyro uses these, but they allowed me to borrow it.”

Engie was a bit skeptical at first, since it was a new material, but he got the hang of it rather quickly. He was almost ecstatic the first time it fell - the blocks barely made any sound at all!

After a few games, Spy had to leave for an assignment. Engie put a hand on their arm.

“Thank ya, Spy. Maybe you ain’t the cold-blooded backstabber I thought you were.”

Spy chuckled, but said little else. He didn’t want to admit that noise sensitivity plagued him as well.

Pyro:

Pyro loves board games, and has quite the collection in their room.

Each plastic piece is at least a little melted, and all the boxes have two or three scorch marks.

Hungry Hungry Hippos, Candyland, and Uno are among her favorites.

He is an absolute beast at Uno, though.

They take each game very seriously, especially when they can convince the whole team to play.

As you can imagine, it’s pure chaos - it even led to a rule in the Merc Guidebook: “When playing Uno with three or more players with the inclusion of a Pyro, at least one Mann Co. representative and/or a mediating Medic must be present.”

Pyro has been known the hide cards, bribe players, or even try to set flame to competition. Playing Uno is almost like a mission, with weapon preparation and Spy posing as other players.

The mercs even have a betting stand that Sniper runs. All parties have lost a lot of money that way.

It’s pretty much the only time outside of battle that the team remembers how cruel and malicious Pyro can be.

Sniper:

Conventional board games aren’t exactly his forté, but he does enjoy a bit of cards every once in a while - Solitaire being his favorite.

He even has a pack of cards in his Sniper Square for that exact purpose. It allows him the pass the time without having to look away from his targets too often.

On occasion, he could be pressed to play poker, but only if the stakes weren’t monetary (i.e candy pieces, crackers, duties, etc.).

His favorite part of every match is shuffling the cards. Pretty much every merc could shuffle cards, but Sniper could make them almost float with how quick his fingers and wrists moved. He always began the game with a new trick he learned, which delighted his fellow players (usually Spy, Engineer, Medic, and Demo).

You could always tell if he had a busy day because he would avoid tricks with too much movement, which would be murder on his sore fingers and hands.

Pyro is currently learning card tricks from Sniper, and show off what they learn at the beginning of every Uno game.

Heavy:

He isn’t a huge fan of the bright, plastic-y board games that Pyro has, although he will play them if asked.

It’s mostly because of how complicated the rules are and the fact there are almost never a Russian translation for the directions.

He always prefers checkers, cards, or mancala, which he almost exclusively plays with Medic because he’s the only one who speaks fluent Russian.

Heavy can play a mean game of mancala, though, and it’s the only game he can beat Medic at.

Soldier:

The only games he will play are Battleship and Uno - but only after Miss Pauling convinced him it was “American enough” because the game had red, white, and blue cards.

He prefers the electronic Battleship because of the sound effects and voices. However, if it’s out of batteries, he’ll make his own sound effects.

Miss Pauling is the best at pretending to be a commander, so she’s usually the one playing with him - but, sometimes, Demo gets in on the action, too.

#tf2#tf2 fandom#tf2 headcanon#tf2 headcanons#tf2 sniper#tf2 demo#tf2 scout#tf2 medic#tf2 spy#tf2 pyro#tf2 engineer#tf2 miss pauling#tf2 solly#tf2 heavy#humor#funny post#just for laughs#funny content#funny#dank humor#send asks#ask blog

152 notes

·

View notes

Text

Azula and the Mirror

In film, mirrors are used for moments of reflection, obviously, both the physical and emotional kind, but they are also used for moments of deceit, deception, dejection, juxtaposition, contrast and comparison, distortion, delusion, breaking down and breaking through. A persona is never more vulnerable, nor stronger, than when it is staring at itself, and the visual power of these moments have been used in cinematic narratives beginning at the dawn of the medium and continuing to the present day. (source)

It might seem obvious, but mirrors used in film and television have a wealth of meaning, and present a visually striking way to get that meaning across. Mirrors show us who we really are, but they also show us what we want to see. Therefore a mirror can be a symbol of both truth and lies.

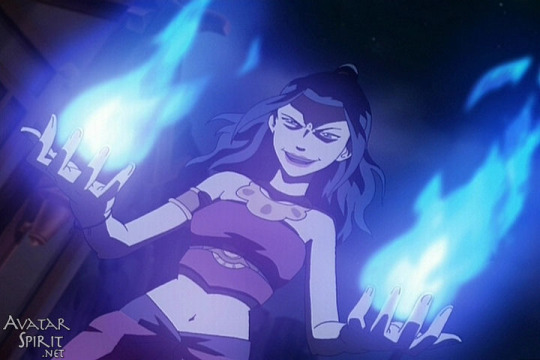

This scene in “Sozin’s Comet” is one of the most memorable Azula scenes because of the use of the visual imagery to tell us the story of who Azula is, and it’s one of the most clear pictures we get of her in the entire series. Perhaps Azula is also seeing herself for the first time, but it’s also a moment when she’s at her most self-deluded. Confronted with both the reality of herself and the lie that she desperately clings to.

I think that, more than anything, Azula craves authenticity. Her brother Zuko does, too, and I’ll make a separate post as a follow up to this one because I want to avoid going off on a tangent. I’ll keep this post focused on Azula, although since Azula is an essential part of Zuko’s narrative, it’s hard to talk about them entirely separately. So I am going to cheat a little bit here and talk about what Zuko says about Azula, since it’s one of our biggest introductions to her before we actually meet her.

Zuko (to Aang): There's always something. Not that you would understand. You're like my sister. Everything always came easy to her. She's a firebending prodigy, and everyone adores her. My father says she was born lucky. He says I was lucky to be born.

Zuko puts Azula up on a pedestal here, although it’s one that also comes with a lot of resentment. Zuko defines Azula as everything that he is not, successful where he is not, and adored where he is not. The latter is particularly interesting because although we do get a sense that Azula is “adored,” it is most likely in a shallow way. I think Azula would absolutely be the popular girl in school but she wouldn’t have very many real friends. What she would have is power and status, like many bullies do, and that might be enough to gain her a following, as it does in canon, but it’s clear that this is not enough, and I think that she’s beginning to realize it.

Azula believes in the image of herself as the perfect princess, and several other people in her life reinforce this. Ozai, Zuko, Mai and Ty Lee, Li and Lo. By the end she loses them all, though, and is left with the one person who did see her for who she was. Ironically, this is the one person she does not want to see, because this is the reflection of herself that she does not want to see.

There are several different parts of Azula at play here. The image she presents to others, the image she wishes she could present, and the image of herself that she denies.

The image she presents to others is the one Zuko talks about in “The Siege of the North.” The powerful princess who can’t even have just one hair out of place.

The person Azula wishes she coulbe, the part of herself that craves authenticity but doesn’t know how to get it, is on full display in “The Beach.”

Azula demanding to be invited to a party that Ty Lee and Mai get asked to tells us a lot about how Azula sees her friendship with the latter two. It shows Azula’s jealousy of their social skills but also her need for control in her relationships. Even before the rift between the three really starts, we get a sense that Ty Lee and Mai aren’t as fully in Azula’s corner as she thinks they are. Azula thinks that fear and control are enough to gain her friends and allies. Deep down, she knows that this is not true, however she does not know another way to be. But the party provides an opportunity to try and embrace this authentic self that she craves.

Zuko: Why didn't you tell those guys who we were?

Azula: I guess I was intrigued. I'm so used to people worshiping us.

Ty Lee: They should.

Azula: Yes, I know, and I love it. But, for once, I just wanted to see how people would treat us if they didn't know who we were.

Zuko’s question to Azula is really interesting, too, and I’ll talk about that and Zuko’s perspective in another post, because I want to keep the focus on Azula here. Azula masks her desire for authenticity in haughtiness, saying that she’s “used to” being worshipped and reinforcing Ty Lee’s comment that they should worship her them, and that she loves it, but it’s clear that what she really wants is to be liked for who she is, or rather, who she might be if she were not Ozai’s daughter, princess of the Fire Nation.

This is also shown in Azula’s jealousy of Ty Lee during the party.

Ty Lee: What? You're jealous of me? But you're the most beautiful, smartest, perfect girl in the world.

Azula: Well, you're right about all those things. But, for some reason, when I meet boys, they act as if I'm going to do something horrible to them.

I’ve seen a lot of discussion of this conversation in the context of Azula’s relationship with Ty Lee, and a lot of people cite this as a sympathetic moment for Azula or an indication that she really does care for Ty Lee, although I tend to be less charitable in that regard, since Azula just told Ty Lee that boys only liked her because she was “easy” and made her cry. For me, this scene really highlights the toxic nature of the relationship between Azula and Ty Lee, where Azula boosts her self esteem by bringing Ty Lee down. Azula does admit her jealousy of Ty Lee, and some people read this as Azula comforting Ty Lee, but 1) Azula is the one who made Ty Lee cry in the first place, and 2) Ty Lee is then put in the position of comforting Azula and assuaging Azula’s jealousy, even though Azula is the one who made Ty Lee cry. This is reminiscent of a lot of abusive relationships in which the abuser will harm their victim and then twist the narrative so that the victim has to be responsible for comforting the abuser. Ty Lee knows what is expected of her in this dynamic, and responds by reaffirming Azula’s need to be seen as perfect, Azula agrees, and all is restored in the world again.

Except Azula still craves that authenticity. When she tries it, though, she gets Ty Lee’s advice hilariously wrong, and resorts back to what she knows. Conqueror Azula. Princess of the Fire Nation. Perfect weapon.

There are a lot of moments that people point to in “The Beach” when they analyze Azula, but here’s the moment which I think is really Azula at her most authentic.

Azula: Well, those were wonderful performances, everyone.

Zuko: I guess you wouldn't understand, would you, Azula? Because you're just so perfect.

Azula: Well, yes, I guess you're right. I don't have sob stories like all of you. I could sit here and complain how our mom liked Zuko more than me, but I don't really care. My own mother thought I was a monster. She was right, of course, but it still hurt.

I’m going to take a slightly different approach than what I usually see when people talk about this scene because I do think this is when we are finally seeing a glimpse of Azula’s authentic self, but not in the way a lot of people who discuss her think.

I’ve talked about how Azula presents a mask to others. Here, she calls Zuko, Mai, and Ty Lee’s emotional confessions about their deepest trauma “performances.” She uses Zuko’s confession to reinforce her place as the golden sibling, calling him “pathetic.” Zuko expresses resentment and anger at “perfect” Azula. And then Azula reveals a sob story of her own.

Azula in this scene shows deep-seated anger towards her mother, which she tries to play off flippantly, but her words reveal how deep this trauma actually is. She says her own mother thought she was a monster. Do I think that this is a reflection of what Ursa thought about Azula? Absolutely not, and I think what has to be remembered about this scene is that it comes from Azula herself. This scene, plus the mirror scene in “Sozin’s Comet” involving Azula and her mother, both originate from Azula’s thoughts and feelings about her mother. We will never know what Ursa herself really, truly thought about Azula, because all we get from her is either from Zuko or Azula’s perspective. These statements and thoughts and visions from Azula are meant to tell us about Azula, not Ursa. This is not, as the “Ursa is a bad mother” crowd insists, proof that Ursa hated Azula. This is what Azula thinks about herself.

We know that Ursa did scold Azula and try to steer her on a correct path, but that’s because Azula was acting in increasingly worrying ways in the flashbacks. The young Azula we see in “Zuko Alone” had already begun to build her Perfect Princess image, modelled after what Ozai expected her to be, and what Ozai expected her to be was both infallible and monstrous.

And a part of Azula knows that what Ozai expected of her was monstrous. But since she had no choice but to internalize it, she could not reconcile that part of herself with the part of herself that was taught right and wrong by her mother. That part of herself she locked away tightly. But comes out here, because Azula in “the Beach” is trying to achieve an authentic self, which is, in fact, what Lo and Li say at the beginning of the episode that the beach is supposed to do, and Ty Lee bookends that sentiment. Just like in the previous scenes, though, Azula still can’t quite get there. Her feelings about her mother are still couched in condescending language, she belittles the others, and she dismisses her mother in the same paragraph. She embraces the monster because that is who she was taught to be, and monsters cannot be hurt.

And that, that’s it. Azula can’t admit that she was hurt by her mother’s absence. I’ve said before that Azula translated her mother’s abandonment as “she loves Zuko more than me” because Ursa left for Azula and in the world where Azula is perfect and Zuko is nothing, that does not compute. This creates some huge cognitive dissonance which cannot be reconciled.

Azula’s confession here about her mother also is a way for her to reinforce to the group that she’s still the most powerful. She casually dismisses Mai, Zuko, and Ty Lee when they talk about their trauma so that she can talk about herself, in language that blames her mother for the person she is. It’s not that Azula is at fault, it’s not that Azula cannot reconcile her fractured sense of self, it’s that everyone else is pathetic and Ursa is a bad mother who made her feel this way, although really, she was right, so what does it matter?

One of the main reasons that most Azula redemption speculation falls flat is that they don’t acknowledge that in order for Azula to get redemption, she has to take responsibility for the ways in which she has hurt others. This would also be incredibly difficult for her, and in some ways that isn’t her fault, because she was very much a victim of Ozai’s abuse, and one way that she was a victim is because by instilling the need that she had to be perfect, Ozai made it nearly impossible for Azula to acknowledge when she was wrong. She gets perilously close here, but then retreats into blaming her mother, her brother, her friends, and anyone else, then denies that she even wants to change, which is the other thing she has to accept in order to get redemption.

Fast forward to Azula confronting her mother’s image in the mirror, which of course is really herself. This is why I hate where the comics took this particular subplot, because I do not think we were meant to interpret it as Azula actually hallucinating. What Azula is seeing in the mirror is really herself, the part of herself that understands right from wrong, but is too afraid to admit that she’s done so many things wrong. That little girl who can’t even properly mourn the loss of her own mother because she was never allowed to, because her father never let her. Right before Ursa appears, Azula attacks her own image in the mirror, viciously cutting her hair, a symbol of “perfect” Azula and an obvious symbol of Azula’s self-hatred. Just as before, though, she can’t really direct this anger and blame and pain at herself, so she conjurs up the image of her mother, who tells her all the truths she wants to deny about herself, that her mother always loved her, that she has embraced fear and control and that this has left her lonely in the end. This is the closest that Azula has ever come to realizing her authentic self, the little girl who misses her mother. But she rejects it again.

So mirrors represent self-reflection, right? The fractured mirror, then, is a clear symbol for the fractured self. These are all the sides of Azula that she cannot reconcile as one. Whereas Zuko’s narrative deals with the restructuring of the fractured self, Azula’s narrative deals with what happens when the fractured self never becomes whole.

115 notes

·

View notes

Text

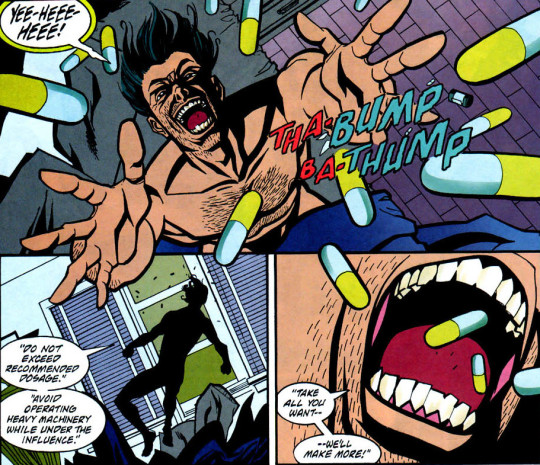

...and the unironic joys of better living through chemistry

How do I love Venom: The Hunger, let me count the ways…

It’s by far the shippiest Venom/Eddie story to come out of the character’s heyday. It’s the only story of the era to treat Venom’s violent wild-animal instincts not as an immutable fact, but as something that can be managed. It pulls off an aesthetic like nothing else that was being done at the time.

And then there’s the way it says, Does the world around you seem sinister and foreboding? Do you lie awake at night contemplating metaphorical oceans of despair? Well shit, son – have you considered you may be suffering from a mundane neurochemical imbalance, and a round of the right meds could clear that right up for you?

It does all this without breaking the atmosphere, without a whiff that our story has been interrupted for a Very Special Message about mental health.

In the near-decade since I was first prescribed anti-depressants, I don’t think I’ve read another story that lands the message “Sometimes, it’s not you, it’s just your brain chemistry,” so well.

Fair warning: if you have not read The Hunger, I am about to spoil every major plot point. If you have, well, maybe I can still give you a new appreciation for a few details you might have missed.

It’s a strange book, whatever else you take from it. It’s almost the only thing either author or artist contributed to the Venom canon, and it’s so different stylistically and tonally from the 90′s Venom norm that it feels like a tale from some noir-elseworlds setting instead of 616 canon. When you take risks that big with a property, you leave yourself precious little landing space between 'unmitigated triumph’ and ‘abject failure’: if this book hadn’t absolutely nailed it, I’d be dismissing it as edgy, OOC dreck. Fortunately, if The Hunger is nothing else, it is a story that $&#@ing commits – to basically everything it does.

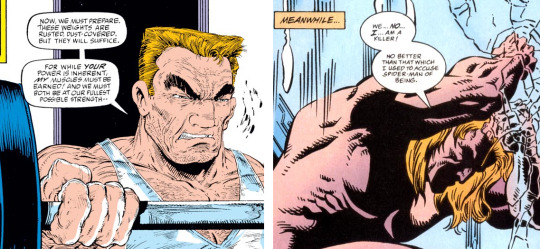

Now, I'm not going to tell you Venom: The Hunger is a story about overcoming depression, because I don't know whether author Len Kaminski even thought about it that way while working on it. There's always space for other readings, and this one take is not gospel. That said: holy shit is this thing unsubtle with its metaphors. And with that in mind, let’s start by talking a little about Kaminski’s take on Eddie himself.

As I may have mentioned before, I like to divide 90′s Eddie into two broad personas: the Meathead, and the Hobo.

Kaminski’s Eddie nominally belongs in the angsty, long-haired Hobo incarnation, but that’s a bit of a simplification: this version certainly has plenty of angst and plenty of hair to his name – but nowhere, not even at his lowest ebb, does he doubt that he and his Other are meant for each other, which is usually Hobo!Eddie’s primary existential quandary.

He’s also taken up narrating his own life like a hardboiled PI.

So that’s... novel.

The only other time Eddie’s sounded like this is, er, in that one other Venom one-shot Kaminski penned (Seed of Darkness, a prequel that sadly isn’t in The Hunger’s league), so I think we can safely file it under authorial ticks.

Then again, Hobo!Eddie’s always been one melodramatic SOB, so maybe this is just how he’d sound after learning to channel his angst into his poetry. You can’t argue it fits the aesthetic, anyway.

We’d also be remiss not to mention Ed Halsted’s art, which I can only describe as gothic-meets-noir-meets-H.R.-Giger. Never before or since has the alien symbiote looked this alien: twisted with Xenompoph-like ridges and veins.

But Halsted doesn’t treat Venom to all that extra detail in every panel. Instead, the distortion tends to appear when the symbiote is separated from Eddie or out of control – and I doubt you need me to walk you through the symbolic importance of that creative decision. More importantly, Halsted’s art provides exactly the class of visuals that Kaminski’s story needs.

Did I mention this is a horror story? You might be surprised how few Venom stories really fit that genre, but if all those adjectives about Halsted’s style above didn’t clue you in, this is one of them.

Anyway, with that much context covered, let’s get into the main narrative of this thing.

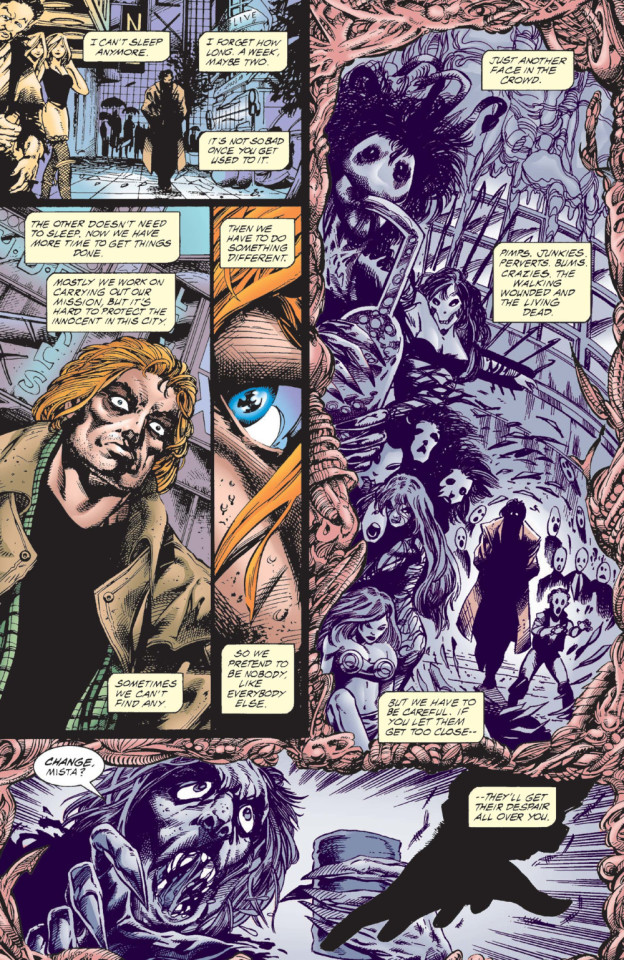

As our first issue opens, Eddie’s world has become a dark and foreboding place. He’s not sleeping, though he mostly brushes this off. (Fun fact: trouble sleeping is one of those under-appreciated symptoms of depression. Additional fun fact: the first doctor ever to suggest I might be suffering from depression was actually a sleep specialist. You can guess how that appointment was going.)

Just to set our scene, here’s all of page 1.

Eddie’s narration has plenty of (ha) venom for his surroundings, but the visuals are here to back him up: panels from Eddie’s POV are edged in twisted, fleshy borders and drained of colour, the people rendered as creepy, goblin-like creatures. A couple of later scenes go even further to contrast Eddie-vision with what everyone else is seeing:

As depictions of depression go this is a little on the nose, but then, you don’t read a comic about a brain-eating alien parasite looking for subtlety, do you?

Eddie doesn’t see himself as depressed, of course. As far as he’s concerned, he’s seeing the world’s true face: it’s everyone else who’s deluding themselves. He’s still got his symbiote, so he’s happy. He’s yet to hit that all-important breaking point where something he can’t brush off goes irrevocably wrong.

But he’s also starting to experience these weird... cravings.

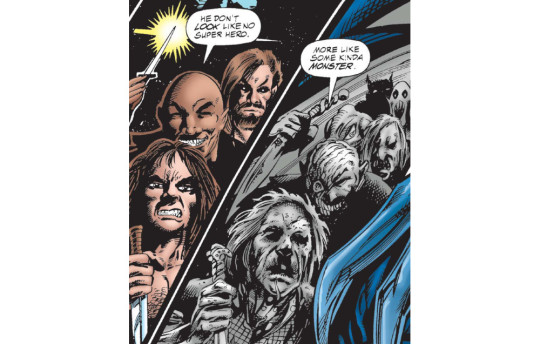

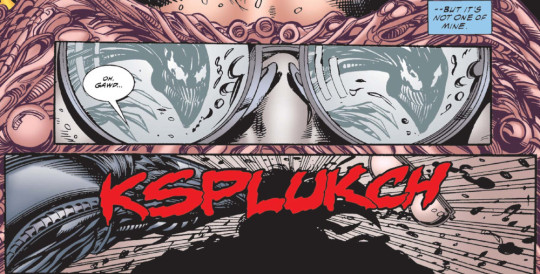

He just can’t put a name to exactly what he’s craving until a routine bar fight with a couple of thugs takes a turn for the horrific.

(I include this panel partly to point out even in The Hunger, the goriest of all 90′s Venom titles, you’re still not going to see brains getting eaten in any graphic detail. We don’t need to to get the horror of the moment across. The 90′s were a more innocent time.)

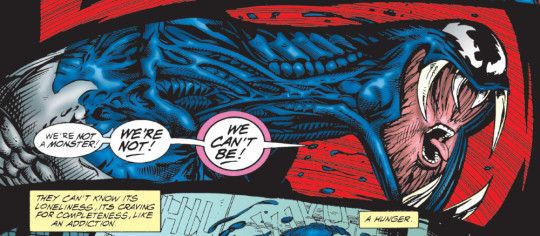

Eddie himself is horrified when he comes back to himself and realises what he’s done.

Or rather, what his symbiote’s just made him do.

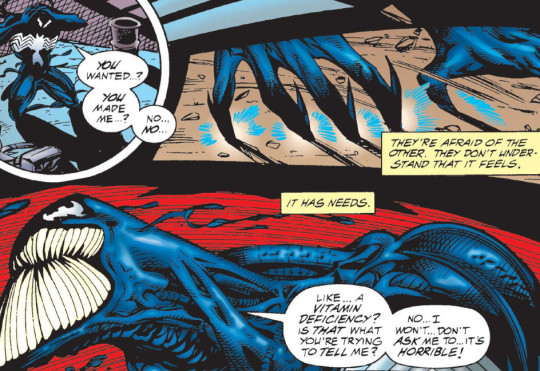

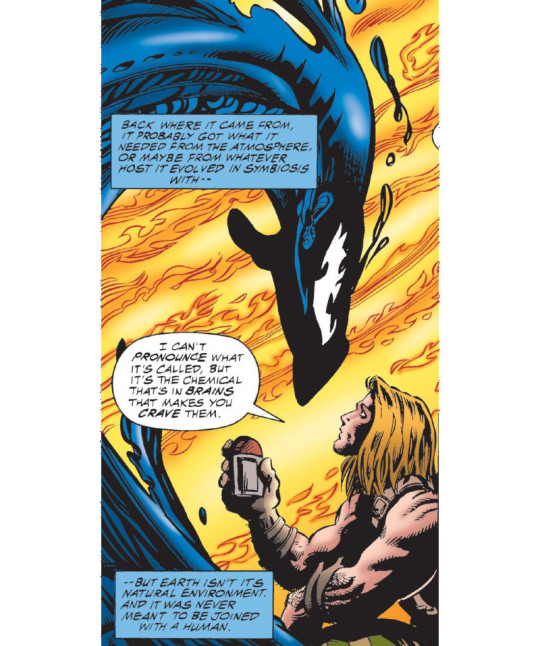

Kaminski doesn’t keep us in suspense about why, though. Eddie may have just done something horrific, but there’s a reason, and it’s as mundane as a vitamin deficiency. He’s bonded to an alien creature, after all, and his symbiote is craving a nutrient which just happens to be found in human brains. And if Eddie can’t or won’t help it meet that need, it’ll do so alone.

Now, giving us that explanation so quickly is an interesting creative decision: this is a horror story, and horror lives in what we don’t know. Wouldn’t it be all the more horrifying had the symbiote been unable to explain what’s going on, leaving Eddie without the first real clue as to where this monstrous new hunger had come from?

The Hunger doesn’t take that route though, and I love it. Eddie isn’t a monster, this isn’t his fault: he has a fucking condition, and wallowing in his own moral failings is going to get him nowhere. You might as well try to cure scurvy or rickets with positive thinking. Just like depression can make you feel like an utter failure at the most basic parts of being human, and all the affirmations in the world won’t fix it when it’s fundamentally your brain chemistry that’s the problem. Or like addicts aren’t weak-willed for struggling not to relapse, they’re dealing with genuine chemical dependency – or even like how someone who’s trans isn’t at fault for being unable to reconcile themselves to the bodies and the hormones they were born with by pure force of trying. Free will is more than an illusion, but we’re all messy, biological organisms underneath, and your own brain and biochemistry can and will fuck you over in a hundred wildly different ways for as many wildly different reasons and it’s not your fault.

We aren’t monsters. But if we do, sometimes, find ourselves identifying with the monster, there might be a reason for that.

(Ahem)

I’m just saying, that’s fucking powerful, and we need more stories that say it.

Anyway, in case you missed it during that tangent, issue #1 closes with the symbiote having torn Eddie’s heart in two itself free to go hunting brains without him.

I’m trying not to get too sidetracked at this point talking about Kaminski’s take on the symbiote itself. Suffice to say there are broadly two schools of thought on how it ought to function while separated from its host: the traditional ambulatory-slime-puddle version, and the more recently popular alternative where anything-you-can-do-with-a-host-you-can-also-do-without-one. I’m not much of a fan of the latter, personally: if your symbiote doesn’t actually need a host, I feel you’ve sort of missed the point. (The movie takes the route of saying symbiotes can’t even process Earth’s atmosphere without a host, which is a great new idea that appears nowhere in the comics, and I love it. Hosts or GTFO, baby!)

Kaminski has his own take, and I can only wish it had caught on. Without Eddie, the symbiote becomes an ever-shifting insectoid-tentacle-snake-monstrosity, driven by an animalistic hunger. It’s many things, but it’s never humanoid.

If you absolutely must have your symbiote operating minus a host, I feel this is the way to do it: semi-feral, shapeless and completely alien (uncontrollable violence and cravings for brains to be added to taste).

Issue #2 comes to us primarily through the perspective of the mild-mannered Dr. Thaddeus Paine of the Innsmouth Hills Sanitarium (yes, really).

Yeah, he’s not fooling anyone. Meet our official villain! He joins our story after Eddie is picked up by the police and handed off to the nearest available institution, on account of how completely sane and rational he’s been acting.

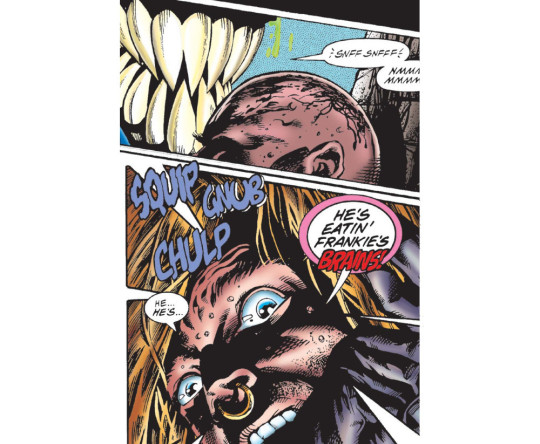

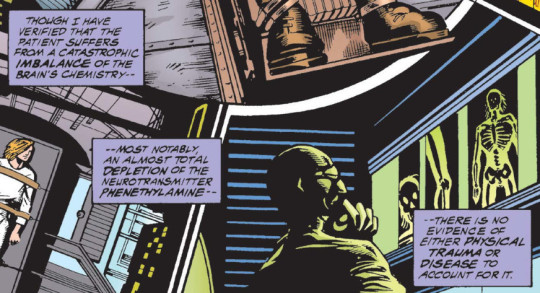

Naturally, Dr. Paine soon has copious notes on Eddie’s ‘crazy’ story about his psychic link to a brain-eating alien monster. Fortunately for Eddie, Paine also runs some tests and makes an interesting discovery.

Congratulations, Venom: the ‘vitamin’ you were missing officially has a name!

Finding the right meds isn’t always this easy. I got lucky – the first ones my psych put me on worked pretty well – but I have plenty of friends who weren't so lucky. In fact, the treatment for Eddie's problems is so straightforward it arguably has more in common with, say, endocrine disorders like thyroid conditions or Addison’s disease, which differ from clinical depression but present many similar symptoms (but can sadly be just as much of a bitch to get correctly diagnosed – please do read author Maggie Stiefvater’s account of the latter when you get the chance, because forget Venom, that is a horror story).

‘True’ depression remains much less well understood by medicine, either in its causes or how to effectively treat it. But simply having a name for what was wrong with me made so much difference, and that’s an experience I imagine anyone who’s dealt with any long undiagnosed medical condition could relate to. It put my life in context in a way nothing else had in years.

(I can’t speak to the accuracy of the way phenethylamine is portrayed in this comic – a quick google suggests there may be some real debate that phenethylamine deficiencies have been overlooked as a contributor to clinical depression, but having no medical background, that one’s well beyond me. Either way, scientific accuracy really doesn’t matter in this context – it’s how it works in-universe for story purposes that we should pay attention to.)

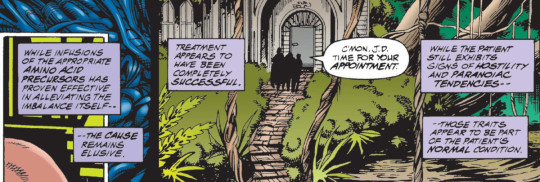

Since this issue is mostly from Paine’s POV, we don’t get Eddie’s reaction to having a healthy amount of phenethylamine sloshing around in his brain again, just the assurance that treatment appears to be ‘completely successful’.

He’s still a paranoid, hostile bastard though. Meds can turn your life around, but they won’t make you not you.

But even if Eddie’s feeling better, he’s still psychically linked to someone who isn’t. Symbiote-vision still comes through drained of colour and edged in viscera.

That’s the thing about meds: they won’t solve all your problems overnight. If you’ve been depressed for a while, there are good odds you have problems stacking up. But working meds can be a godsend when it comes to getting you into a space where you can deal with your problems again, whether said problems are doing-your-laundry or all the way into not-giving-up-completely-and-just-accepting-you’ll-die-alone-on-the-street.

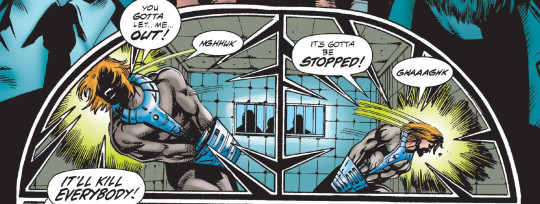

For Eddie, ‘dealing with his problems’ begins with stealing a keycard and busting out of the asylum.

Of course, that’s the easy part. How do you solve a problem like a feral symbiote? Like any good 90′s comic book protagonist, Eddie tackles it by putting on his big-boy camouflage pants and kitting himself out with weapons and pouches while quoting “If you live something, set it free. If it doesn’t come back, hunt it down.”

We can add this to the list of things I love about this comic. Even if The Hunger is a weirdly-stylistic tract about depression at heart, it’s also still a goddamn 90′s Venom comic, and not ashamed to be.

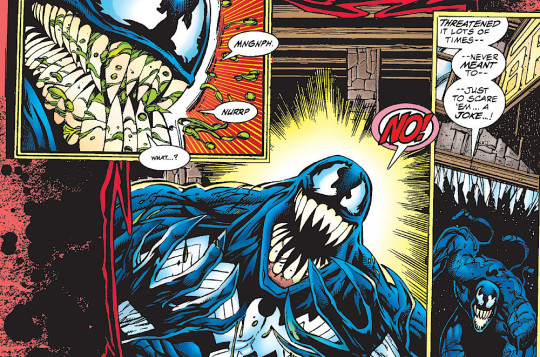

We’re into issue #3 now, and back to hearing the story from Eddie’s POV.

Eddie is very much aware that his symbiote has murdered innocent people while they’ve been separated. Even if this is the result of extreme circumstances, there’s a good case to be made that the symbiote is too dangerous to be allowed to live. Plenty of heroes would treat it like a rabid dog at this point.

But Eddie isn’t a hero, he’s a mess of a character and an anti-hero at best, so we don’t have to hold him to the same standard. He’s well aware his symbiote may be too far gone to save, that he may have to put it down – but that’s only his backup plan. He wants to help it. He wants it back. He’s down in that sewer with screamers and a flamethrower because he knows all his symbiote’s weaknesses, but he’s also carrying a large jar of black-market synthesised phenethylamine, because if he can just get close enough...

Depression can’t make you a literal monster, but it can make you an asshole. Miserable to be around, lacking even the energy to care who else you’re hurting. The depression doesn’t excuse that, but it makes everything harder, and it’s that much easier to sink back into your spiral when everyone around you has given up. It can make you think everyone around has given up even if that isn’t true.

So to have Eddie here say, in effect, I don’t care how many people you’ve eaten, I know it wasn’t your fault. I still love you. You’re still worth fighting for – god, does that get me right in the id.

There’s still a whole issue left at this point – we’ve still got to deal with our real villain, Dr. Paine, who we’ve just learned is into eating brains himself and torturing his patients recreationally, and who wants to capture the symbiote for his own purposes. There’s the scene where Eddie and his symbiote finally bond again, and Venom beats up all Paine’s goons while singing David Bowie because like I said, this is still a 90′s superhero comic and this is what Venom does.

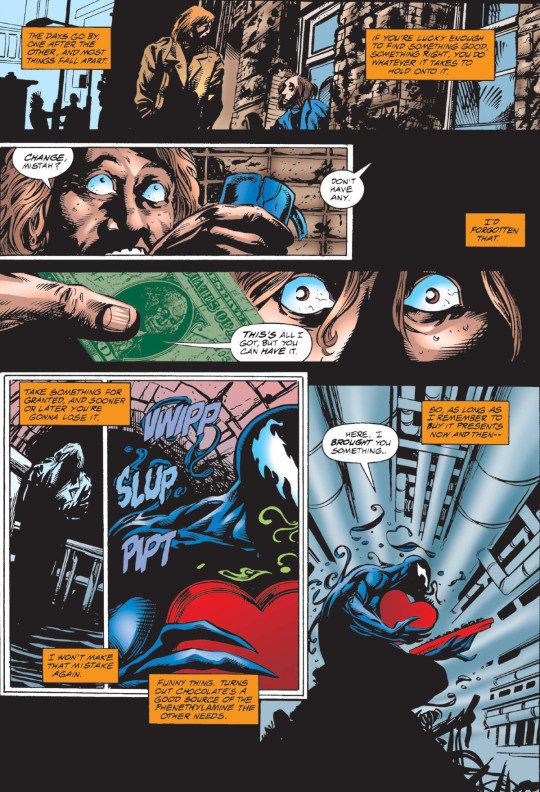

But for our purposes, I'm going to skip to the penultimate page of the story, because the way it mirrors our opening page is really lovely.

Remember that shot of Eddie dealing with a beggar back at the beginning of the story, thinking about how these people would 'get their despair all over you'? Here he is again, cheerfully forking over the last dollar in his pocket to the next man to ask him for change. For all the gothic atmosphere and gore, it’s moments like this that make The Hunger easily one of the most positive, uplifting Venom stories ever written. Funny, that. (I could probably write a whole other essay on sympathy for the homeless as a recurring motif in Venom stories, but that... well, whole other essay and all that.)

What’s Eddie learned from this experience? Don’t take your symbiote for granted. Is ‘symbiote’ a metaphor for mental health here, is paying attention to its needs an allegory for paying attention to your own? I still don’t know how literally Kaminski meant us to take this, but it’s a lovely note to end on no matter how you parse it.

At the end of the day, The Hunger isn’t flawless. The conflict with Paine ends on a thematic but slightly unsatisfying note. Eddie makes much of his symbiote's loneliness and desire for union, but when the two of them are finally reunited, the only reaction comes from Eddie's side. In fact, the symbiote seems to have no response to being able to return to Eddie at all, and that’s an omission that bugs me.

But Kaminski is more interested than any other writer of the era in the truly alien nature of the symbiote, in its relationship with Eddie from Eddie’s side, and though plenty of others talk about the symbiote's love/hate relationship with Spider-man, no-one else had the guts to portray their relationship this much like a romance.

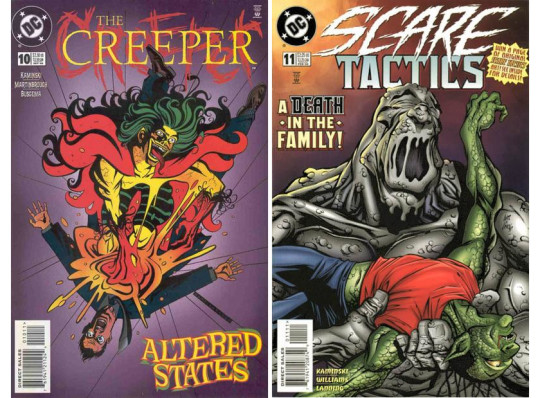

And Venom: The Hunger is no less interesting in the context of Len Kaminski’s other work. You don't have to look far into his Marvel and DC credits to pick up that the guy has a real thing for monsters. (“All of my favourite characters are outlaws, misfits, anti-heroes,” he says, in one of the very few interviews I could find with him, “I wouldn't know what to do with Superman.”) He's written for vampires, werewolves, victims of mad science, and all of three at once, littering his work with biochemistry-themed technobabble, melodramatic monologues, gratuitous pop-culture references, and protagonists who must learn to embrace their inner demons. So The Hunger represents more than a few of his favourite running themes.

For our context, his more notable other work includes Children of the Beast, in which a werewolf must make peace between his human and animalistic sides, and The Creeper, in which a journalist must make peace with the crazy super-powered alter-ego sharing his body. In fact, The Creeper and The Hunger share so much DNA (including an evil doctor posing as a respected psychiatrist who uses hypnosis on our hero while he's trapped in a mental institution) that it’s quite the achievement that they still feel like such very distinct entities beyond that point.

The human alter-egos of both werewolf and Creeper even use prescription meds while wrestling with their respective dark sides. The difference, in both cases, is that these are stories where meds play their traditional fictional role – and that's a role that could be as easily filled by illegal drugs or alcohol without making any substantive difference. You see, if a protagonist is using them, it's a sign of unwillingness to tackle their 'real' problems. Even among work by the same author in the same genre, The Hunger represents an outlier. And that's just a little disappointing – at least to me.

In real life, of course, prescription meds are no magical cure-all elixir. Depression meds that work for one person may not work for another, or may not keep working in the longer term. Everyone has heard stories about quack doctors who prescribe them to the wrong patients for the wrong reasons, about lives ruined by addictions to prescription painkillers, or the supposedly-damning statistics about how poorly SSRI's perform in rigorous clinical trials. The proper way to treat depression is obviously with lifestyle and therapy. People will still airily dismiss medications that we all know previous generations got along just fine without, or suggest that figures like Van Gogh would never have created great art if they hadn't been mad enough to slice off an ear. I mean, the fact you think you need those bogus mediations is probably the best possible sign of just how broken you are, right? Who do you think you’re kidding?

Our popular fiction loves stories about manly men who bury their trauma under a gruff, anti-social exterior and come back swinging at the world that broke them, bravely refusing even painkillers that might dull their manly reflexes. Other genres make space for broken people confronting their demons in grand moments of catharsis, finally breaking down into tears when someone gets through to make them face their problems. "I could barely make it out of bed in the mornings until I found a doctor who started me on this new prescription" is not only wildly counter to the accepted social narrative, it's a hard thing to know how to dramatise.

Even other Venom comics have been guilty of this.

Believe me, I recognise all of this, and just how much progress we've made in the last few decades. But I haven't the slightest doubt that for so many vulnerable people, the stigma against prescription medications does infinitely more harm than those same meds could ever do. And just having the right to externalise my problems into it's not you, it's your brain chemistry, may have helped me more than the meds themselves.

(And again, no, being prescribed SSRI's didn't fix me overnight, but I honestly don't know if all the talk therapy and tearful conversations with family members in the world could've got me as far as I've come without them.)

I love Venom: The Hunger. It's no-one's idea of high art, but it doesn’t need to be. There is a whole other post’s worth of things I love about it that I’ve already cut out this one as pointless tangents, and that may actually be it’s biggest drawback as a go-to example: I fully recognise that I would not be making this post if The Hunger hadn't also also grabbed me as a great bit of Venom canon, being the massive fan and shipper that I am. Other people who are just as desperate as me for more stories with the same core theme, but not into weird 90's comics about needy goo aliens, probably won't get nearly as much out of it as I have.

But if it sounds anything like your jam, maybe you'll enjoy it as much as I did.

If nothing else, it proves that you can make a viscerally satisfying story out of a message that shockingly unconventional. And you may even have people still discovering it and falling in love with it 25 years after the fact.

98 notes

·

View notes

Note

As someone that loves almost every character in ACOTAR but still wants to discuss their flaws and slip ups I really liked your post about Nesta and how she treated Feyre as a sister. None of the characters in ACOTAR are perfect. They have flaws and people in the fandom need to keep the same tone about all of them when it comes to that. Don't excuse one character and bash on the next. Like of course you can have your favorites, but Idk I just love seeing the characters as flawed rather than put them on a pedestal. Cheers 🖤

I mean I absolutely love flaws. I love Nesta for that reason. She’s such an imperfect, easily debatable character. Her interactions with others are amazing because of this, because she’s not so easy to be around, so she pushes a lot of boundaries or expands the way these characters have learned to adapt in their world. They’ve never met anyone who is not so easily swayed, which is obvious in all her interactions with them. Though I won’t get into it, since this post will be a thousand times longer.

But I think if any character is most human-like, as in she is based on how someone in the real world would act, she’s probably the most authentic in my opinion. But authenticity requires a level of flaws that can’t be denied or overwritten. So, I really did want to stress that, that she can keep her mistakes, her cold demeanor, her sometimes harsh words, her standoffishness, her distrust many times, but at some point she’s going to have more character development and will she really exonerate herself and claim she played no part in her own life or the lives of her family members? She hasn’t before. She’s acknowledged that Feyre went out and kept them alive, but to what extent does she feel guilty or regretful or even blameless? Not specifically about that situation, but... the lack of friends, her relationship with her father, her sisters, or any close relationship before and after the trauma, her own wants, wishes, goals, the lack of purpose. In the case of the cabin, and now in the case of her father’s death, she’s really coping the same way. Someone else is supporting her, and she’s really mentally unhealthy and very closed off. You know maybe I’m taking a page out of my own psychotherapy textbook, but I think healing for her would require her to see more options, to be open to more opportunities, and for her to see the world and how she interacts with it a little bit differently where she has accountability for her own wellbeing and happiness, but also accepts the role she played in the past that she could’ve changed.

*But* if she copes that way throughout the series and she doesn’t allow anyone in and she unintentionally hurts someone’s feelings, for lack of a better term, then their feelings are still valid whether we understand them or not. That’s how POV’s work. A change in the narrative. And if in Feyre’s POV Nesta’s done wrong in some way even though some may not agree, even if Feyre herself has done wrong, it doesn’t mean we erase the mistakes as if they didn’t happen. I think to really analyze a character you need to see the whole character and not just the things that make them palatable or the things we’d rather ignore/excuse, even in the pursuit of defending them. As readers, we’re the third party observers, so we can see more things than the characters, but to Feyre for example, Nesta has an odd way of showing her love to the point where we have instances where she questions it throughout the series. It doesn’t mean necessarily that Nesta has to change or that she doesn’t love Feyre, but it also doesn’t make Feyre wrong to feel that way. or Elain or Cassian or Amren whatever happened to them. It also doesn’t make the Inner Circle wrong for not liking her, though the situation is more complicated than that. If Feyre’s hurt that Nesta won’t come to her after all they’ve through, after she’s reached out, and tried to help in the way that she knew how, then she is allowed to be hurt. And if Nesta’s perspective says that Feyre wronged her after what happens in ACOSF, even if Feyre had good intentions and explains her intentions, Nesta has been wronged. I think there’s a certain level of validity that we need to keep when discussing their interaction or any interaction, otherwise we start playing a blame game, when no one is at fault. It’s too complex to be simply one person’s fault and we know practically nothing of Nesta’s POV. It’s not Feyre or the Inner Circle’s fault that Nesta is in a bad way. But it’s not Nesta’s fault that Feyre sometimes feels hurt or betrayed or unloved. Which unfortunately makes the situation very complicated and quite oxymoronic.

Also I think that sometimes people feel (which people have also said to me) that discussing Nesta’s flaws is a direct attack on her character, because other character’s flaws are not as highlighted in the fandom nor Feyre’s POV. But I think that in itself is a whole other post. Because Feyre has grown up with Nesta, and she has seen her in so many lights, and she’s really only beginning to know how the Inner Circle are truly when the wars are over and the dust has settled. You know, they took her in when she was really low and in an emotionally abusive relationship and having had a traumatic experience with the Amarantha situation, and they supported her and her decisions. So, I find that it would be hard to really expect that from Feyre where we ended in ACOSAF. But this of course doesn’t mean that we can’t dislike a character or question why they do things. It just means that we can dislike a character for a lot less than having to make one character seem inherently greater than another and making people feel bad about it. They all offer value to the series that we all are so obsessed about. But also we as posters can’t reasonably post essays. Like I can’t post something discussing Nesta’s flaws and a specific circumstance and then equally talk about several other character’s flaws in the same post to make everyone feel better and sure that I’m not taking a side.

Which is what I try to get at sometimes when people comment and they seem a little bit too aggressive. Which is why I really don’t like the whole anti/pro debacle, even though I understand the practicality of being able to filter certain posts you see on tumblr because of those hashtags. Thankfully there hasn’t many people who are uber aggressive and honestly I block a lot of people who continually post things in which they don’t allow their opinion to be challenged in any way. Because at the end of the day, none of us are wrong, but... some I’d say are more right than others--simply because they have and use textual evidence to back up their claims or they make reasonable connections that don’t stomp on anyone’s opinions and open up a discussion in which everyone exchanges their ideas. There are so many posts I absolutely adore in either direction, because of how well-rounded they approach the topic.

That being said, quite honestly that post that thankfully you appreciate, absolutely drives me insane. Every time someone likes it or comments I get so afraid that it’s going to be someone telling me off. But I’m a very anxious person so that’s probably why, but also I’ve seen many people being told off lol. I really was hoping it wasn’t too bad or being too biased. I absolutely hate that. And I certainly don’t want to be just agreed with, I love active discussions and will have them with many people on here, but I don’t like feeling like at any moment I could be invalidated and my opinion worthless when all I did was post something I felt was accurate to my own analysis. So I’ve almost deleted that post so many times. But thankfully, y’all are not horrible... so far.

Anyways, I for some reason go on tangents that only half make sense. Stream of consciousness and ADHD I guess. But hopefully this reply wasn’t so drastic. I absolutely love that you support the active discussion of flaws and the character’s who have them and you are more than welcome to discuss with me anytime :D As long as your okay with the fact that I write essays as opposed to simple thanks haha!

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Essays in Existentialism: Polo 3

Previously on Polo

The sun was glaring; absolutely murdering the entirety of the world in the noontime shine of a clear day in the early spring. The heat couldn’t come just yet, still not allowed due to larger forces like the tilt of the planet and the distinct absence of a certain player, yet to be seen despite a not-so-covert glance at the pitch during warm ups. The entire event was going to be the largest of its kind, and it was like the world knew it, opening itself up and shining all of the kindest wishes on the sport, as a large herd of watchers made their way to find a place to watch.

The tents were stocked with alcohol and snacks, people in hats and those who were there because they were supposed to be. But along the pitch, bleachers filled up with anyone who wanted to watch, creating an atmosphere of joy and excitement that’d been lacking at the private matches.

There really wasn’t a reason to be there. Clarke had more than fulfilled her daughterly duty for the entire year with her increasingly frequent showings at events for both of her parents. She chalked it up to growth, and becoming a better person, to make an effort, to try her best to show her mother that she was happy for her, and to prove to her father that she was deserving of her name, even if that meant trudging through society things in lieu of his wife.

But seeing as Kane’s opening of the Gauntlet of Polo opening day party was not her mother’s, nor was it something she felt compelled to do to represent her father, Clarke had no true reason to go other than because Kane was nice enough to invite her, and she truly had nothing else to do.

“So where’s the hot polo playing Argentinian underwear model who recites you poetry and fucks you in stables?”

Clarke grit her teeth before sighing and shaking her head, giving her best friend a look that should equal death, if she’d been luckier.

“What?” Raven shrugged. “I want to get a good look at the girl that convinced you to be okay with your parents divorce. I’m sure there are over-paid therapists who would kill to know how to do it.”

“She didn’t--”

“And made you nicer in general to your parents. And me. And your life is less chaotic now-- I’ve noticed you are volunteering. That must be some of the worlds most powerful puss--”

“Kane! Mom!” Clarke interrupted her friend’s tangent, thankfulness apparent in her voice as she found the host and hostess.

Her mother was always beautiful, but Clarke began to see how much nicer happiness looked on her, and as much as she claimed to always love her father, there was a girlish spark that came when Abby was near Marcus. It took Clarke long enough to put aside her feelings to see it, but when she did, she couldn’t have been happier, despite the occasional bitterness about what was lost. It was Lexa’s stupid notions of love that messed with her brain and her ability to hold a grudge.

There’d been a truce between herself and Kane, reached gently and treated very cautiously, but still, it remained. She had dinner with them just a week ago when they were in the city, and it wasn’t entirely painful. As much as she wanted to dislike Marcus Kane, she couldn’t bring herself to do it because he was just… nice. And he made Abby smile in a way that Clarke didn’t realize she hadn’t seen in a while.

The real benefit of all of this love and joy being that while Abby got to live her best truth, it meant less comments about Clarke’s “wasted potential,” and there was a bigger focus on her art, which led to less stress with their average communications.

“Oh, honey you made it,” Abby smiled and hugged her daughter, kissing her cheek quickly, squeezing her shoulders. “I didn’t think we’d find you in all this.”

“Believe it or not,” Clarke explained as she accepted a quick hug from her mother’s boyfriend. “It’s easy to find the guy who owns a team in a tournament sponsored by his company.”

“I’ve been looking and couldn’t find you.”

“I took Raven to see the ponies.”

“Look at that,” Kane grinned. “She’s using proper jargon already.”

“Clarke’s given me a quick rundown, but I don’t know if I trust her expertise yet,” Raven offered after all pleasantries were exchanged. “Care to teach me, Kane?”

“The more the merrier,” he smiled wider, like a kid in a candy store, surrounded by people who wanted to listen to him explain his favorite sport. “We better go find a good spot. It’ll start soon.”

Raven turned and gave Clarke a wry grin before linking her arm with Kane’s as she maneuvered them through the crowd. Clarke let her mother squeeze her and follow along a few steps behind.

“It means a lot that you’ve tried to take an interest in something that Marcus finds important,” Abby offered as they meandered along.

“Just a good reason to be outside, and Raven loves selling rich people her programs and things,” Clarke dismissed her effort for anything benevolent as she grabbed a flute of champagne gratefully. “I’m fairly certain that’s the only reason she keeps me around.”

“Whatever the reason. It means a lot to me. I know it wasn’t easy to find out--”

“We don’t have to do this.”

“I know,” Abby relented. “You just never cease to amaze me is all. Marcus is important to me, and you’ve taken the time to get to know him, just like I’m sure you would when your father starts--”

“Dad won’t date anyone else.”

The words came out a little bit too harsh, and Clarke wasn’t sure why she felt so protective of her father’s refusal to get over a broken heart.

“He will eventually, and believe it or not, no matter how he feels about Marcus and even me right now, seeing you be open to our happiness will make it easier.”

“I guess I’m just a saint.”

It was meant to be a joke, but Clarke felt suddenly a little guilty. They took their seats beside Kane and Raven, and Clarke looked out on the pitch, wondering if she would be there at all if it hadn’t been for the oddest addiction she somehow developed for a stupid girl who argued with her every time she saw her.