#british cinematographer 2023

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Oooh! A great Gavin Finney (Good Omens Director of Photography) interview with Helen Parkinson for the British Cinematographer! :)

HEAVEN SENT

Gifted a vast creative landscape from two of fantasy’s foremost authors to play with, Gavin Finney BSC reveals how he crafted the otherworldly visuals for Good Omens 2.

It started with a letter from beyond the grave. Following fantasy maestro Sir Terry Pratchett’s untimely death in 2015, Neil Gaiman decided he wouldn’t adapt their co-authored 1990 novel, Good Omens, without his collaborator. That was, until he was presented with a posthumous missive from Pratchett asking him to do just that.

For Gaiman, it was a request that proved impossible to decline: he brought Good Omens season one to the screen in 2019, a careful homage to its source material. His writing, complemented by some inspired casting – David Tennant plays the irrepressible demon Crowley, alongside Michael Sheen as angel-slash-bookseller Aziraphale – and award-nominated visuals from Gavin Finney BSC, proved a potent combination for Prime Video viewers.

Aziraphale’s bookshop was a set design triumph.

Season two departs from the faithful literary adaptation of its predecessor, instead imagining what comes next for Crowley and Aziraphale. Its storyline is built off a conversation that Pratchett and Gaiman shared during a jetlagged stay in Seattle for the 1989 World Fantasy Convention. Gaiman remembers: “The idea was always that we would tell the story that Terry and I came up with in 1989 in Seattle, but that we would do that in our own time and in our own way. So, once Good Omens (S1) was done, all I knew was that I really, really wanted to tell the rest of the story.”

Telling that story visually may sound daunting, but cinematographer Finney is no stranger to the wonderfully idiosyncratic world of Pratchett and co. As well as lensing Good Omens’ first outing, he’s also shot three other Pratchett stories – TV mini series Hogfather (2006), and TV mini-series The Colour of Magic (2008) and Going Postal (2010).

He relishes how the authors provide a vast creative landscape for him to riff off. “The great thing about Pratchett and Gaiman is that there’s no limit to what you can do creatively – everything is up for grabs,” he muses. “When we did the first Pratchett films and the first Good Omens, you couldn’t start by saying, ‘Okay, what should this look like?’, because nothing looks like Pratchett’s world. So, you’re starting from scratch, with no references, and that starting point can be anything you want it to be.”

Season two saw the introduction of inside-outside sets for key locations including Aziraphale’s bookshop.

From start to finish

The sole DP on the six-episode season, Finney was pleased to team up again with returning director Douglas Mackinnon for the “immensely complicated” shoot, and the pair began eight weeks of prep in summer 2021. A big change was the production shifting the main soho set from Bovington airfield, near London, up to Edinburgh’s Pyramids Studio. Much of the action in Good Omens takes place on the Soho street that’s home to Aziraphale’s bookshop, which was built as an exterior set on the former airfield for season one. Season two, however, saw the introduction of inside-outside sets for key locations including the bookshop, record store and pub, to minimise reliance on green screen.

Finney brought over many elements of his season one lensing, especially Mackinnon’s emphasis on keeping the camera moving, which involved lots of prep and testing. “We had a full-time Scorpio 45’ for the whole shoot (run by key grip Tim Critchell and his team), two Steadicam operators (A camera – Ed Clark and B camera Martin Newstead) all the way through, and in any one day we’d often go from Steadicam, to crane, to dolly and back again,” he says. “The camera is moving all the time, but it’s always driven by the story.”

One key difference for season two, however, was the move to large-format visuals. Finney tested three large-format cameras and the winner was the Alexa LF (assisted by the Mini LF where conditions required), thanks to its look and flexibility.

The minisodes were shot on Cooke anamorphics, giving Finney the ideal balance of anamorphic-style glares and characteristics without too much veiling flare.

A more complex decision was finding the right lenses for the job. “You hear about all these whizzy new lenses that are re-barrelled ancient Russian glass, but I needed at least two full sets for the main unit, then another set for the second unit, then maybe another set again for the VFX unit,” Finney explains. “If you only have one set of this exotic glass, it’s no good for the show.”

He tested a vast array of lenses before settling on Zeiss Supremes, supplied by rental house Media Dog. These ticked all the boxes for the project: “They had a really nice look – they’re a modern design but not over sharp, which can look a bit electronic and a bit much, especially with faces. When you’re dealing with a lot of wigs and prosthetics, we didn’t want to go that sharp. The Supremes had a very nice colour palette and nice roll-off. They’re also much smaller than a lot of large-format glass, so that made it easy for Steadicam and remote cranes. They also provided additional metadata, which was very useful for the VFX department (VFX services were provided by Milk VFX).”

The Supremes were paired with a selection of filters to characterise the show’s varied locations and characters. For example, Tiffen Bronze Glimmerglass were paired with bookshop scenes; Black Pro-Mist was used for Hell; and Black Diffusion FX for Crowley’s present-day storyline.

Finney worked closely with the show’s DIT, Donald MacSween, and colourist, Gareth Spensley, to develop the look for the minisode.

Maximising minisodes

Episodes two, three and four of season two each contain a ‘minisode’ – an extended flashback set in Biblical times, 1820s Edinburgh and wartime London respectively. “Douglas wanted the minisodes to have very strong identities and look as different from the present day as possible, so we’d instantly know we were in a minisode and not the present day,” Finney explains.

One way to shape their distinctive look was through using Cooke anamorphic lenses. As Finney notes: “The Cookes had the right balance of controllable, anamorphic-style flares and characteristics without having so much veiling flare that they would be hard to use on green screens. They just struck the right balance of aesthetics, VFX requirements and availability.” The show adopted the anamorphic aspect ratio (2:39.1), an unusual move for a comedy, but one which offered them more interesting framing opportunities.

Good Omens 2 was shot on the Alexa LF, paired with Zeiss Supremes for the present-day scenes.

The minisodes were also given various levels of film grain to set them apart from the present-day scenes. Finney first experimented with this with the show’s DIT Donald MacSween using the DaVinci Resolve plugin FilmConvert. Taking that as a starting point, the show’s colourist, Company 3’s Gareth Spensley, then crafted his own film emulation inspired by two-strip Technicolor. “There was a lot of testing in the grade to find the look for these minisodes, with different amounts of grain and different types of either Technicolor three-strip or two-strip,” Finney recalls. “Then we’d add grain and film weave on that, then on top we added film flares. In the Biblical scenes we added more dust and motes in the air.”

Establishing the show’s lighting was a key part of Finney’s testing process, working closely with gaffer Scott Napier and drawing upon PKE Lighting’s inventory. Good Omens’ new Scottish location posed an initial challenge: as the studio was in an old warehouse rather than being purpose-built for filming, its ceilings weren’t as high as one would normally expect. This meant Finney and Napier had to work out a low-profile way of putting in a lot of fixtures.

Inside Crowley’s treasured Bentley.

Their first task was to test various textiles, LED wash lights and different weight loadings, to establish what they were working with for the street exteriors. “We worked out that what was needed were 12 SkyPanels per 20’x20’ silk, so each one was a block of 20’x20’, then we scaled that up,” Finney recalls. “I wanted a very seamless sky, so I used full grid cloth which made it very, very smooth. That was important because we’ve got lots of cars constantly driving around the set and the sloped windscreens reflect the ceiling. So we had to have seamless textiles – PKE had to source around 12,000 feet of textiles so that we could put them together, so the reflections in the windscreens of the cars just showed white gridcloth rather than lots of stage lights. We then drove the car around the set to test it from different angles.”

On the floor, they mostly worked with LEDs, providing huge energy and cost savings for the production. Astera’s Titan Tubes came in handy for a fun flashback scene with John Hamm’s character Gabriel. The DP remembers: “[Gabriel] was travelling down a 30-foot feather tunnel. We built a feather tunnel on the stage and wrapped it in a ring of Astera tubes, which were then programmed by dimmer op Jon Towler to animate, pulse and change different colours. Each part of Gabriel’s journey through his consciousness has a different colour to it.”

Among the rigs built was a 20-strong Creamsource Vortex setup for the graveyard scene in the “Body Snatchers” minisode, shot in Stirling. “We took all the yokes off each light then put them on a custom-made aluminium rig so we could have them very close. We put them up on a big telehandler on a hill that gave me a soft mood light, which was very adjustable, windproof and rainproof.”

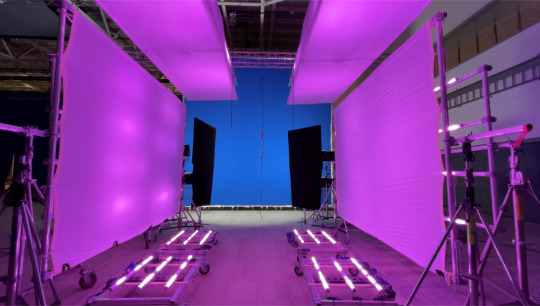

Shooting on the VP stage for the birth of the universe scenes in episode one.

Sky’s the limit

A lot of weather effects were done in camera – including lightning effects pulsed in that allowed both direct fork lightning and sheet lightning to spread down the streets. In the grade, colourist Spensley was also able to work his creative magic on the show’s skies. “Gareth is a very artistic colourist – he’s a genius at changing skies,” Finney says. “Often in the UK you get these very boring, flat skies, but he’s got a library of dramatic skies that you can drop in. That would usually be done by VFX, but he’s got the ability to do it in Baselight, so a flat sky suddenly becomes a glorious sunset.”

Finney emphasises that the grade is a very involved process for a series like Good Omens, especially with its VFX-heavy nature. “This means VFX sequences often need extra work when it comes back into the timeline,” says the DP. “So, we often add camera movement or camera shake to crank the image up a bit. Having a colourist like Gareth is central to a big show like Good Omens, to bring all the different visual elements together and to make it seamless. It’s quite a long grade process but it’s worth its weight in gold.”

Shooting in the VR cube for the blitz scenes .

Finney took advantage of virtual production (VP) technology for the driving scenes in Crowley’s classic Bentley. The volume was built on their Scottish set: a 4x7m cube with a roof that could go up and down on motorised winches as needed. “We pulled the cars in and out on skates – they went up on little jacks, which you could then rotate and move the car around within the volume,” he explains. “We had two floating screens that we could move around to fill in and use as additional source lighting. Then we had generated plates – either CGI or real location plates –projected 360º around the car. Sometimes we used the volume in-camera but if we needed to do more work downstream; we’d use a green screen frustum.” Universal Pixels collaborated with Finney to supply in-camera VFX expertise, crew and technical equipment for the in-vehicle driving sequences and rear projection for the crucial car shots.

John Hamm was suspended in the middle of this lighting rig and superimposed into the feather tunnel.

Interestingly, while shooting at a VP stage in Leith, the team also used the volume as a huge, animated light source in its own right – a new technique for Finney. “We had the camera pointing away from [the volume] so the screen provided this massive, IMAX-sized light effect for the actors. We had a simple animation of the expanding universe projected onto the screen so the actors could actually see it, and it gave me the animated light back on the actors.”

Bringing such esteemed authors’ imaginations to the screen is no small task, but Finney was proud to helped bring Crowley and Aziraphale’s adventures to life once again. He adds: “What’s nice about Good Omens, especially when there’s so much bad news in the world, is that it’s a good news show. It’s a very funny show. It’s also about good and evil, love and doing the right thing, people getting together irrespective of backgrounds. It’s a hopeful message, and I think that that’s what we all need.”

Finney is no stranger to the idiosyncratic world of Sir Terry Pratchett and Neil Gaiman.

#good omens#gos2#season 2#interview#gavin finney#neil gaiman#terry pratchett#gavin finney interview interview#s2 interview#bts#fun fact#british cinematographer#british cinematographer 2023#jon hamm#2ep1#2ep2#2ep3#2ep4#2ep6#2i1i1#job's minisode#1941 minisode#1827 minisode#2i6i7#bentley

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

'Tower blocks in Britain could have been what villages once were to this cramped little island: humble concentrations of community amid the greenbelts and the farms and the swaths of land marked out for the haughty upper class. The midcentury model of the council housing estate centered on high-rise developments of boxy apartments, piled and clustered tightly enough that everybody in them knew everybody else. In London, this neighborly ideal harked back to a past version of the city, which, long before it was unified as a sprawling metropolis, was once a patchwork of separate villages. Many estates sprang up on sites razed by bombing during the Second World War, brutalist symbols of stoic survival and renewal.

But ideals rarely endure in a country quick to settle for austerity—there’s no nation-defining British dream to speak of here. And so the perception of the tower block shifted, with every man’s tiny home becoming his castle, fortified by suspicion, marginalized by government neglect. If the tragedy of the 2017 Grenfell Tower fire signified the worst-case outcome of a crumbling social-housing model, the glossier, glassier private high-rises now mushrooming around Britain’s major cities mark their own sort of societal decay. Priced to exclude and designed to divide—many of the ones with a government-mandated quota of “affordable” apartments offer separate entrances and facilities for the poorer residents—they’d be hard-pressed to evoke village life even if many of them didn’t stand pristinely, echoingly empty.

In All of Us Strangers (2023)—Andrew Haigh’s exquisite, twilit tangle of lives and loves separated by space, time, and personal defenses—such isolation suits London screenwriter Adam (Andrew Scott) just fine. Gay, single, and somewhere past forty, he is one of a scarce few residents to have moved into a sheeny, geometric new block in an unloved stretch of the East End. The lighting in the building’s lengthy corridors sets an intimate mood for nobody in particular; the mirrored elevators dizzyingly multiply the reflection of anyone who steps inside, perhaps so they might feel less solitary. At the outset, cinematographer Jamie D. Ramsay shoots the skyline as seen from Adam’s lofty living-room window, its familiar silhouettes toy-sized beneath a huge, heavy dawn sky. We’re in the city, yet it looks so far away.

Adam cultivates distance. If he has any friends, we don’t see them. His apartment, compact and chicly furnished, is fitted entirely for one. Even then, the place doesn’t look wholly lived-in: he may spend his days within its walls, watching real-estate TV shows and procrastinating over a new screenplay, but he’s never quite at ease, at home. When we eventually hear him speak, it’s as if he is out of practice, surprised by the sound of his own voice, itself a hesitant, placeless thing, with Estuary English edges softened by an Irish lilt. His gaze is long and his posture unyielding. This is not a man between relationships, taking time out from the world; Adam is proficient, even expert, in his solitude. He was born lonely, he explains, even before his parents were killed in a car crash when he was just eleven. First as an only child and then as an orphan, he feared he would be alone forever; as an adult, he says, the fear “just solidified.” The great, mournful beauty of Scott’s performance is in its bodily evocation of loneliness as daily routine: from the way he walks to the way he sleeps, he makes no room for others—though that will change.

If one could cross-pollinate Haigh’s films, it would be tempting to matchmake Adam with Russell (Tom Cullen), the similarly handsome, withdrawn protagonist of the director’s 2011 breakthrough feature, Weekend—a heartsore queer romance on a tight schedule, chronicling a one-night stand that stretches to a second night, and then to the brink of something altogether deeper, only to be thwarted by the calendar. Russell lives in a Nottingham tower block, in an apartment less stylish than Adam’s, with a view less expansive. But it offers him an equivalent refuge—way up on the fourteenth floor—from a world he reticently holds at arm’s length. He is younger than Adam, his routines less rigid. Venturing into a nightclub, Russell connects with the more outgoing Glen (Chris New), sampling for one weekend a life of unfamiliar companionship, before being left in his shabby flat once more. In both Weekend and All of Us Strangers, Haigh maps out the simultaneous security and insecurity of urban high-rise living, the way it functions as quiet sanctuary and solitary confinement for characters pushed to the margins by their queerness, their reserve, or both.

“How do you cope?” The question comes from Harry (Paul Mescal), Adam’s only visible neighbor, mere seconds into their first meeting—after a fire drill exposes the scant population of their building. It’s not a typical chat-up line, but Harry, who has shown up drunk at Adam’s door with a bottle of Japanese whiskey begging to be shared, hasn’t time for small talk. Besides, he already knows the answer, as someone who isn’t coping much at all himself. Another gay man adrift in this unoccupied space, albeit twenty-odd years younger, Harry identifies in Adam both a kindred spirit and an anxious vision of his future. Mescal’s performance, with its plaintively flirtatious delivery and piercing eye contact, articulates a kind of loneliness that hasn’t yet settled and hardened. But Adam, not given to letting people in, shuts the door, and with it, their only chance at a life together. He won’t know this, of course, until they’re very much in love.

All of Us Strangers, like Joseph L. Mankiewicz’s The Ghost and Mrs. Muir and Anthony Minghella’s Truly Madly Deeply, is a ghost story in which the uncanny merges so fluidly with the everyday that one might easily forget it’s a fantasy at all. There is no horror here in the afterlife. Adam either sees dead people or imagines them so vividly into being that they become independent spiritual entities; either way, he accepts their presence without confusion or protest. Perhaps this sixth sense is a natural consequence of his own partial retreat from the land of the living. Deftly and inventively adapting Taichi Yamada’s 1987 novel Strangers, Haigh isn’t preoccupied with the rules and regulations of this strange dimension but rather with its emotional truths.

In this existential hinterland, ghosts can’t necessarily identify one another as such, while Adam can only really differentiate a member of the deceased if he recalls the death in question. Such is the case when, on a memory-stoking trip to Sanderstead, the very ordinary outer-London scene of his early childhood, he spots a man he recognizes, and follows him home. Leather-jacketed and neatly mustachioed, the man (Jamie Bell) is a little younger than Adam, and for a charged, uncertain moment, we think perhaps they’ve cruised each other. But it’s his father, fresh-faced and frozen at his age of death; back at the family home, his mother (Claire Foy) is likewise undead and well, still in her eighties perm and loose pastel sweats. They’re pleased but not overly surprised to see him, and the reunited trio settles comfortably into catching up.

That Adam has moved the dozen-plus miles from Sanderstead to Stratford—from London’s dowdy outskirts to one of its throbbing urban centers—is a point of pride to his working-class parents, who hail from the era when Margaret Thatcher demonized poverty, encouraging the hoi polloi to transcend their roots. Adam’s writing career may not have made him famous or glamorous, but it nonetheless strikes his parents as a step up from their ordinary, wage-earning lives: something to brag to the neighbors about.

His sexuality, revealed on a second encounter, is another matter. “They say it’s a very lonely kind of life,” says his rattled mother, echoing a line heard by many gay people in a period when the powers that be explicitly aimed to isolate them, no matter how much queer communities rallied against it. For his parents, locked forever in 1987, the reality of gay life is the one presented by the mainstream media, with panic-inducing headlines about the AIDS epidemic, and Thatcher’s openly homophobic government, then on the brink of bringing Section 28 into law and thereby banning the “promotion of homosexuality” by local authorities. Why wouldn’t Adam’s admission strike fear into his mother’s heart? Foy pitches her aggrieved tone perfectly, her voice terse and tightened, not merely with ingrained prejudice but also with a parent’s dismay at a child’s identity having formed outside her sphere of influence.

But the 2020s are a brave new world, Adam explains, even if he doesn’t quite share in it: to the question of being lonely, he responds, “If I am, it’s not because I’m gay, not really.” Like much of what he tells his parents, it’s a half-truth, meant to make his life sound fuller than it is. Adam can be more honest with Harry, after correcting his earlier error and inviting him inside. When they eventually fuck, in velvety half-light, Adam must remind himself to breathe. Because he came out and of age in a more paranoid time for gay men, erotic abandon doesn’t come easily to him.

As in Weekend and his HBO series Looking (2014–16), Haigh himself doesn’t take gay physicality for granted. All of Us Strangers is a film that evokes the heart-quickening voltage of a hand boldly planted on an inner thigh, a film whose sex scenes are marked by the sweat and friction and curiosity of two unfamiliar bodies discovering each other’s sweet spots. The pinched bearing of Scott’s performance loosens in dialogue with Mescal’s portrayal, which in turn gains something of the former’s tense vulnerability.

Harry, for his part, fears his generation approaches sex too cleanly. Noting how his peers identify more readily as queer than as gay, he wonders if there’s a sterile politeness to the former label, “like all the dick-sucking has been taken out of it.” The men find in each other something realer and closer than they have hitherto been offered by this vast city and by a scene that has been clinically compartmentalized by hookup apps, as well as the gradual decimation of London’s queer social spaces over the last two decades. (The gay club is a pivotal point of movement and exchange in Weekend and Looking, and in All of Us Strangers, it’s the one location that draws Adam into present-day society.) Mutual intimacy doesn’t heal all the wounds of these two wary souls, but it at least allows them to be lonely together—even if, as we come to learn, only one of them is alive.

As the film unfolds, it shows how the dead can pull restlessly at our hearts. In this way, it calls to mind Haigh’s 2015 film 45 Years, which is not a ghost story (at least not in any conventional sense) but a portrait of a marriage undone by unresolved grief. When devoted wife Kate (Charlotte Rampling) sees old vacation images of her husband, Geoff (Tom Courtenay), with his late, pregnant lover, the projection of a life that could have been—one that would not have included her—cuts as deep as any betrayal. In All of Us Strangers, Adam is stymied by memorabilia of a family life stopped cold: the vintage Christmas decorations he pores over in his room, and the eighties records he has seemingly never moved on from, snared up as they are with parental associations and childhood tragedy. One of them, Frankie Goes to Hollywood’s fiercely devotional ballad “The Power of Love,” bridges his relationships to his parents and to Harry, with its pledge of “death-defying love” and its commitment to “keep the vampires from your door.”

Who will protect Adam, however, from a life lived among specters? In Scott’s devastating performance, the character’s initial, unreadable composure slowly crumbles: the more time he spends with his parents, the more he reverts to his preadolescent state, until, lying between them in patterned pajamas, he somehow becomes his middle-aged and eleven-year-old selves all at once. In bed, he cradles himself like a fragile boy; when his father says something he doesn’t want to hear, Adam shushes him with a child’s strident bossiness. His parents insist he must stop seeing them, that they must voluntarily close this afterlife portal. Returned to the reality of his hollow tower block, he has one ghost left to cling to. Back in his own adult bed, he holds Harry’s body close, expressing the same intense need with which he held his parents. Romantic and familial loves reflect one another throughout Haigh’s film, all filling the same void for our affection-starved hero.

And so All of Us Strangers ends in limbo, somewhere between life and death, reality and delusion, comfort and despair. Adam and Harry lie in an embrace so tight their spirits might merge, as the unmistakably sonorous vocal of Holly Johnson commands the viewer to “make love your goal.” Hitherto a master of very English understatement, Haigh has never previously flirted with this volume of sentiment or spirituality, but this ending is the right crescendo for a film about allowing oneself to feel. Much of the movie is shot in a dusky, smoke-blue afterlight, against which human flesh sometimes appears ablaze, like the brilliant last gasp of a scarlet sunset. Fittingly, in the closing frame, the men’s entwined bodies burn so brightly as to become a supernova in the night sky—or a single, hopeful light on in an otherwise dark high-rise.'

#All of Us Strangers#Andrew Haigh#Andrew Scott#Paul Mescal#Jamie D. Ramsay#Taichi Yamada#Strangers#Jamie Bell#Claire Foy#Looking#Weekend#Criterion#Holly Johnson#Frankie Goes to Hollywood

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

""LAWRENCE OF ARABIA TOOK TWO YEARS AND WAS SHOT IN SPAIN, MOROCCO, AND JORDAN."

PIC INFO: Resolution at 1638x2048 -- Spotlight on the many wide shots from "Lawrence of Arabia" (1962), directed by David Lean, photographed by Freddie Young (OBE, BSC, ASC), stills uploaded on November 17, 2023 by "justashott."

"The three films he made with David Lean were a challenge. “Lawrence of Arabia" took two years and was shot in Spain, Morocco and Jordan. The heat in the desert was a dry heat of 110 degrees. We had a sunshade over the camera and a wet cloth on top of the camera, which acted like refrigerator. We never saw rushes, the results were cabled from London. The famous mirage scene was shot using a 500mm lens. This was obtained from Panavision in Hollywood along with the rest of the camera equipment,” said Young."

-- BRITISH CINEMATOGRAPHER magazine, on the "Gentleman Genius" Freddie Young (OBE, BSC, ASC)

Sources: www.instagram.com/justashottt/p/Czx5u7NM9su & https://britishcinematographer.co.uk/freddie-young-obe-bsc-asc.

#Lawrence of Arabia 1962 Movie#1962#Cinema#60s Cinema#British Cinema#Director of Photography#David Lean#Cinematography#Cinema is Photography#Frederick Archibald Young#Wide Shots#British Cinematographer#Photography#Filmmaking#Lawrence of Arabia Film#1960s#Historical Epic#Freddie A. Young#Lawrence of Arabia 1962#British Film#British Films#Freddie Young#Sixties#60s#British Society of Cinematographers

3 notes

·

View notes

Note

the reason you didn’t love the little mermaid live action is because it was too diverse

yeah, that's why. i'm definitely someone who isn't passionate about animation as a medium and i definitely don't think the live action remakes are destructive to the industry and i definitely don't think they're creatively bankrupt and i definitely loved all the other live actions aside from tlm!!! /s (btw i don't even dislike tlm as much as i do lily ja*mes' cinderella, which has been well documented on my page for close to a decade lol)

also, can we just be for real for a moment? people can say they like halle's casting specifically but the overall casting is far from inclusive. this movie is SO WHITE despite them literally hammering us over the head with their diversity and inclusion initiative in the marketing, which is the same tactic they used for previous live actions. remember all the noise they made about having le fou be gay in the marketing when, in the finished movie, le fou never delivers what was promised to us????

but let's just review this "diverse" cast that's supposed to be believable in the universe that they set in the caribbean

halle's prince that rules the caribbean

halle's dad they cast

halle's "aunt"

halle's "aunt's" alternate form where she's literally using halle's voice

so pretty much all the principles were white for a movie that was set in the caribbean- and not just white but the whitest white you could get, with british accents and all, and a lot of the filming locations they used were in england (that's where the jodi benson cameo was filmed) and the other majority was filmed in italy. so where is this "diversity" coming from? maybe the creative team is diverse??? let's check

the director of this movie

the directors from the original movie that the 2023 remake ripped off

the cinematographer

the writer credited to the 2023 movie

the original writer of the story this movie was based off of

the lyricist

the original composer and lyricist whose works were heavily used in this movie, one of which was brought back for the 2023 production

so, sorry, but i don't view this as a diverse team and i think that if they're going to claim it is, this doesn't cut it in 2023 for being a diverse- or even standard- production. again, this was supposedly set in the caribbean?...yeah, they need to do better. the fact that they literally had a black lead and then gave her a white british prince, a white father, and a white aunt is so backwards. i'm sorry but that's problematic to me- even though brandi's cinderella still had a decent percentage of white talent, it was still far more colorful and that was almost 30 years ago. again, this is 2023???

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

nowe filmy pełne

Sprawdź repertuar Kin - Przysięga Ireny!

Repertuar kin : w repertuarze kinowym film „Przysięga Ireny” zasługuje na szczególną uwagę. To historia młodej dziewczyny, która zmuszona została do bycia kochanką starego niemieckiego oficera, aby uratować życie swoich przyjaciół.

Twórcy filmu

Dan Gordon, uznany kanadyjski scenarzysta, jego kariera nabrała rozpędu dzięki kultowemu serialowi telewizyjnemu „Highway to Heaven”. Do jego najbardziej znaczących prac należą scenariusze do filmów akcji, dramatów i biografii. „Pasażer 57” z Wesleyem Snipesem w roli głównej, to emocjonujący thriller akcji, który zyskał uznanie zarówno widzów jak i krytyków. Film pt. „Wyatt Earp” z Kevinem Costnerem to z kolei epicka opowieść o jednej z ikonicznych postaci Dzikiego Zachodu. Kolejne jego scenariusze to m.in. „Murder in the First”, z udziałem Christiana Slatera i Kevina Bacona oraz „Let There Be Light” z Kevinem Sorbo.

Jednym z najbardziej wyróżniających się osiągnięć Gordona jest scenariusz do filmu „The Hurricane”, w którym Denzel Washington wcielił się w postać Rubina Hurricane’a Cartera, boksera niesłusznie skazanego za morderstwo. Ten poruszający dramat biograficzny, nominowany do Oscara, zyskał uznanie za szczegółowe przedstawienie błędów systemu sądowniczego i niezłomną walkę o sprawiedliwość.Gordon wykazał również swoją zdolność do tworzenia intrygujących opowieści szpiegowskich i thrillerów, czego dowodem jest scenariusz do filmu „The Assignment”, z Donaldem Sutherlandem i Benem Kingsleyem w rolach głównych.

Od Thrillerów, poprzez filmy akcji aż po filmy biograficzne

Przysięga Ireny to film adresowany do szerokiej publiczności.

Dla miłośników filmów akcji Dana Gordona , to na półce nowe filmy Dana Gordona na szczególną uwagę zasługuje „Przysięga Ireny” , film o młodej Polce dla której bycie kochanką starego Niemca było gorsze od gwałtu.

Reżyseria

Louise Archambault, kanadyjska scenarzystka i reżyserka, zyskała międzynarodowe uznanie dzięki swojemu debiutanckiemu filmowi krótkometrażowemu „Atomic Saké”, który przyniósł jej prestiżowe nagrody, w tym Jutra za najlepszy film krótkometrażowy. Jej pierwszy pełnometrażowy projekt, „Familia”, również został ciepło przyjęty na arenie międzynarodowej, zdobywając szereg nagród, w tym nagrodę za najlepszy kanadyjski film pełnometrażowy na Toronto International Film Festival (TIFF) oraz nagrodę Genie za debiut. Archambault ma na swoim koncie również telewizyjne seriale „La Galère”, „Nouvelle Adresse” czy „This Life” dla CBC.

Jej drugi pełnometrażowy film pt. „Gabrielle”, został ciepło przyjęty na Międzynarodowym Festiwalu Filmowym w Locarno, gdzie zdobył Nagrodę Publiczności. Film ten reprezentował Kanadę na Oscarach i Złotych Globach w 2014 roku, zdobywając jednocześnie liczne międzynarodowe wyróżnienia i został sprzedany do ponad 24 krajów.

Archambault została uhonorowana tytułem Osobowości Roku w dziedzinie sztuki i rozrywki przez La Presse/Ici Radio-Canada. Od 2016 roku reżyserowała trzy sezony serialu „TROP” i dwa sezony „Catastrophe” dla Radio-Canada, gdzie ten drugi został wyróżniony nagrodą za najlepszy scenariusz w Cannes w 2018 roku.

W 2019 roku Louise Archambault wyreżyserowała dwa pełnometrażowe filmy: „Il pleuvait des oiseaux” (Deszcz ptaków), który zadebiutował na TIFF i zdobył wiele nagród, w tym za najlepszy międzynarodowy film na festiwalu w Goeteborgu oraz „Merci pour tout” (Dzięki za wszystko), który miał premierę w 2019 roku. Oba filmy osiągnęły wysokie wyniki box office w Kanadzie, zajmując odpowiednio drugie i trzecie miejsce.

W 2023 wyreżyserowała kolejne filmy fabularne francuskojęzyczny „Le temps d’un été” i swój debiut anglojęzyczny „ Przysięga Ireny” .

Obraz w filmie Przysięga Ireny

Paul Sarossy jest wielokrotnie nagradzanym autorem zdjęć filmowych, który współpracował z wybitnymi reżyserami. Jest członkiem Canadian Society of Cinematographers (C.S.C.), American Society of Cinematographers (A.S.C.) oraz British Society of Cinematographers (B.S.C.).

Wielokrotnie nagradzany autor zdjęć filmowych Paul Sarossy ma na swoim koncie zdjęcia do takich filmów jak „Guest Of Honour”w reżyserii Atoma Egoyana z Davidem Thewlisem w roli głównej, który miał swoją światową premierę podczas 76. edycji Międzynarodowego Festiwalu Filmowego w Wenecji, oraz „The Padre” w reżyserii Jonathana Sobela z Timem Rothem i Nickiem Nolte w rolach głównych.

W swoim dorobku ma także filmy fabularne „Don’t Talk To Irene” w reżyserii Pata Millsa, „Goon: The Last Of The Enforcers” w reżyserii Jaya Baruchela oraz brytyjski serial telewizyjny „Tin Star” z Timem Rothem w roli głównej. Oprócz ” Guest of Honour”, Sarossy współpracował z reżyserem Atomem Egoyanem przy filmach „Remember” z Christopherem Plummerem i Martinem Landau w rolach głównych, “The Captive”, “Devil’s Knot”, “Chloe”, “Adoration”, “Where The Truth Lies”, “Ararat”, “Felicia’s Journey”, “The Sweet Hereafter”, “Exotica”, “The Adjuster”, a także przy telewizyjnej produkcji ” Krapp’s Last Tape”.

W 2016r. podczas Festiwalu Camerimage : Egoyan i Sarossy zostali uhonorowani Nagrodą dla Duetu za swoją 27-letnią współpracę. Wśród innych filmów Sarossy’ego znajdują się „The Borgias” Neila Jordana z Jeremym Ironsem w roli głównej, „The Duel” Dovera Koshashviliego, „Act Of Dishonour” Nelofera Paziry, „Ripley Under Ground” z Willemem Dafoe w roli głównej, „Head In The Clouds” z Charlize Theron i Penelope Cruz oraz „Charlie Bartlett” z Robertem Downeyem Jr. w roli głównej. Był także autorem zdjęć do filmów Neila Labute’a „Wicker Man” z Nicolasem Cage’em i Ellen Burstyn, „Duety” z Gwenyth Paltrow, nominowanego do Oscara® „Affliction” Paula Schradera z Nickiem Nolte i Jamesem Coburnem, „Picture Perfect” z Jennifer Aniston, „Love And Human Remains” Denysa Arcanda, „The Secret” Vincenta Pereza oraz „The Deal” z Meg Ryan i Williamem H. Macy. Nagrodzony został za zdjęcia za film „Remember” (2016), otrzymał pięć nagród Genies, dwie Gemini, osiem nagród CSC, nominację do nagrody Emmy®, nominację do nagrody ASC, nominację do nagrody BSC oraz nominację do nagrody Independent Spirit. Paul Sarossy wyreżyserował brytyjski film fabularny “Mr. In Between”, który miał swoją premierę na TIFF i zebrał kilka nagród i nominacji, w tym nominację do Grand Prix i nagrodę dla najlepszego aktora na Międzynarodowym Festiwalu Filmowym w Tokyo.

Sześć filmów Sarossy’ego było nominowanych do Złotej Palmy w Cannes.

Tworzenie nastroju w filmie poprzez muzykę

Alexandra Stréliski, zdobywczyni prestiżowej nagrody Juno, to kompozytorka i pianistka neoklasyczna, która mieszka w Quebecu w Kanadzie. Jej album „Inscape” otrzymał certyfikat platynowy w Kanadzie, a także cieszył się popularnością na klasycznych listach przebojów, osiągając pierwsze miejsce w Kanadzie, drugie w Wielkiej Brytanii oraz piąte w USA. Twórczość Stréliski można usłyszeć w wielu serialach i filmach fabularnych, takich jak „Sharp Objects” (Ostre przedmioty), „Big Little Lies” (Wielkie Kłamstewka), „Dallas Buyers Club” (Witaj w klubie) oraz „Demolition” (Destrukcja). Jej utwory były również prezentowane podczas ceremonii rozdania Oscarów w 2014 roku.

Alexandra może pochwalić się imponującą liczbą 300 milionów streamów, 6 milionami wyświetleń na YouTube, 12 milionami słuchaczy miesięcznie na Spotify oraz 140 000 sprzedanymi albumami.

Magazyn Billboard uznał ją za jedną z najważniejszych nowych postaci współczesnej muzyki klasycznej. Urodzona w Montrealu, w prowincji Quebec, Stréliski jest z pochodzenia polską Żydówką.

Za wszystkim stoi producent filmowy

Beata Pisula producentka filmową i telewizyjna, prowadzi butikową firmę producencką K&K Film Selekt. Zadebiutowała filmem który powstał w koprodukcji amerykańsko-polskiej pt. „Dzieci Ireny Sendlerowej” w reż. John Kent Harrison, film ten nie tylko zdobył nagrodę Primetime Emmy, ale również otrzymał nominacje do tak prestiżowych nagród jak Złote Globy i Satelity. Jej kolejny film to „Amok” w reż. Kasi Admik, który otrzymał wyróżnienia i nominacje na renomowanych festiwalach, w tym na Festiwalu Polskich Filmów Fabularnych w Gdyni i Camerimage. W 2023 roku Beata wyprodukowała dwa polskie filmy fabularne zatytułowane: „W nich cała nadzieja” w reż. Piotra Biedronia i film „ O psie, który jeździł koleją” w reż. Magdaleny Nieć dla Canal+. Zrealizowała również koprodukcję kanadyjsko-polską pt. „Przysięga Ireny” w reżyserii Louise Archambault oraz odpowiadała za produkcję w Polsce filmu „WIL” w reżyserii Tima Mielantsa, który obecnie jest dostępny na platformie Netflix.

Nicholas Tabarrok – producent filmowy i telewizyjny, jest założycielem Darius Films Inc., dynamicznej firmy produkcyjnej z siedzibami w Los Angeles i Toronto. Firma Darius Films Inc. wyprodukowała ponad 40 filmów fabularnych, które nie tylko zyskały uznanie na najbardziej prestiżowych festiwalach filmowych na świecie, ale także osiągnęły znaczący sukces komercyjny. Nicholas współpracował z plejadą gwiazd międzynarodowego kina, w tym Ethanem Hawke, Woodym Harrelsonem, Kurtem Russelem, Nicholasem Cage’em, Dennisem Quaidem, Ronem Perlmanem, Snoop Doggiem, Mattem Dillonem, Harveyem Keitelem, Noomi Rapace, Nickiem Nolte, Susan Sarandon, Timem Rothem, Samem Bee, Sandrą Oh i wieloma innymi. Wśród najważniejszych jego produkcji znajdują się takie tytuły jak „Stockholm”, „Art of The Steal”, „The Padre”, „Weirdsville”, „Defendor” i „The Calling”, które zdobyły uznanie zarówno krytyków, jak i publiczności.

Nicholas jest cenionym członkiem licznych prestiżowych organizacji branżowych, w tym Amerykańskiej Gildii Producentów, Akademii Sztuki i Wiedzy Telewizyjnej, Brytyjskiej Akademii Sztuk Filmowych i Telewizyjnych, Kanadyjskiej Akademii Kina i Telewizji oraz Atelier du Cinema European.

Podsumowując

„Przysięga Ireny” to znakomity film, który powstał w koprodukcji kanadyjsko - polskiej , repertuar kin film na ekrany kin w Polsce i Kanadzie wchodzi od 19 kwietnia, a w USA od 15 kwietnia.

0 notes

Text

Famous May 24, 2023 birthdays.

Tommy Chong (Canadian-American comedian & actor), 85

Bob Dylan (American singer & guitarist), 82

Gary Burghoff (American actor), 80

Patti Holte aka Patti LaBelle (American singer & actress)(pictured), 79

Priscilla Presley (American actress & businesswoman)(pictured), 78

Albert Bouchard (American drummer & singer), 76

Mike Reid (American singer & football player), 76

Waddy Wachtel (American guitarist & record producer), 76

Jim Broadbent (British actor), 74

Sir Roger Deakins (British cinematographer), 74

Alfred Molina (British actor), 70

Rosanne Cash Leventhal (American singer & guitarist), 68

Prof. Richard B. Bernstein (American historian & lecturer), 67

Guy Fletcher (British keyboardist & guitarist), 63

Kristin Scott-Thomas (British-French actress), 63

Alain Lemieux (Canadian hockey player & executive), 62

Rich Rodriguez (American football coach), 60

Pat Verbeek (Canadian hockey player & executive), 59

John C. Reilly (American actor & singer), 58

Carlos Hernández (Venezuelan-American baseball player & analyst), 56

Rich Robinson (American guitarist & singer), 54

Kris Draper (Canadian hockey player & executive), 52

Bartolo Colón (Dominican-American baseball player), 50

Kobayashi Masahide (Japanese baseball player & coach), 49

Dr. Heinrich Manske (German biochemist & software developer), 49

Will Sasso (Canadian actor), 48

Alessandro Cortini (Italian keyboardist & singer), 47

Brad Penny (American baseball player), 45

Johan Holmqvist (Swedish hockey player), 45

Kareem McKenzie (American football player), 44

Jason Babin (American football player), 43

Rian Wallace (American football player), 41

Guillaume Latendresse (Canadian hockey player & coach), 36

Sgt. Monica Brown (American soldier), 35

Artem Anisimov (Russian hockey player), 35

G-Eazy (American rapper), 34

Kalin Lucas (American basketball player), 34

Mattias Ekholm (Swedish hockey player), 33

Cody Eakin (Canadian hockey player), 32

Jarell Martin (American basketball player), 29

#Celebrities#Movies#Canada#Alberta#Music#Minnesota#TV Shows#Connecticut#Pennsylvania#Money#New York City#New York#Sports#Football#U.K.#Tennessee#Hockey#Quebec#West Virginia#Ontario#Illinois#Baseball#Venezuela#Georgia#Dominican Republic#Japan#Germany#British Columbia#Italy#Oklahoma

0 notes

Text

Stars celebrate at the 2023 Oscars afterparties – in pictures | Film

German production designer Christian Goldbeck (L), winner of the Oscar for best production design, British cinematographer James Friend, winner of the Oscar for Best Cinematography and Swiss director Edward Berger, winner of the Oscar for best international feature film, for All Quiet on the Western Front, at the Governors Ball. Photograph: Angela Weiss/AFP/Getty Images #Stars #celebrate #Oscars…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Stars celebrate at the 2023 Oscars afterparties – in pictures | Film#Stars #celebrate #Oscars #afterparties #pictures #Film

German production designer Christian Goldbeck (L), winner of the Oscar for best production design, British cinematographer James Friend, winner of the Oscar for Best Cinematography and Swiss director Edward Berger, winner of the Oscar for best international feature film, for All Quiet on the Western Front, at the Governors Ball. Photograph: Angela Weiss/AFP/Getty Images #Stars #celebrate #Oscars…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Photo

La gara per la #Migliorfotografia potrebbe rivelarsi tra le più imprevedibili della prossima Notte degli Oscar, dato che il suo principale frontrunner, Claudio Miranda (Top Gun: Maverick), vincitore di quasi tutti i principali premi chiave, è stato a sorpresa escluso dalle nomination agli Oscar. In siffatto contesto potrebbe avere la meglio la vincitrice dell’American Society of Cinematographers Award assegnato dal sindacato dei direttori della fotografia, Mandy Walker per #Elvis. Inseguita dal vincitore del BAFTA e del British Society of Cinematographers Award #AllQuietontheWesternFront e anche da #TAR che ha dalla sua parte il Golden Frog vinto all’Energa Camerimage, il Festival cinematografico internazionale dedicato all'arte della fotografia, i cui verdetti hanno un impatto significativo nella successiva corsa agli Oscar per la miglior fotografia. Anche se questi ultimi due film sono stati esclusi dalle nomination agli ASC Awards. (LINK NELLA STORIA) NOMINATION OSCAR 2023 Best Cinematography -“All Quiet on the Western Front” -“Bardo, False Chronicle of a Handful of Truths” -“Elvis” -“Empire of Light” -“Tár” #AwardsSeason #AwardsRace #OscarsRace #RoadtotheOscar #Movies #AwardsRace #BestCinematography #Oscars2023 #OscarsPredictions #FinalPredictions #StagionedeiPremi #Oscar2023 #PrevisioniOscar https://www.instagram.com/p/CpcEz2ssLN8/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

#migliorfotografia#elvis#allquietonthewesternfront#tar#awardsseason#awardsrace#oscarsrace#roadtotheoscar#movies#bestcinematography#oscars2023#oscarspredictions#finalpredictions#stagionedeipremi#oscar2023#previsionioscar

0 notes

Text

To Leslie Garners Oscar Nod for Andrea Riseborough in Long-Shot Bid for Gold

To Leslie was shot in 19 days, but, come 2023 Oscar time, its star, Andrea Riseborough, has earned an Oscar nomination, even if the movie only earned $27,000 worldwide. When I saw it at SXSW in 2022, I was impressed by the entire cast, but the lead performance was so honest and genuine that it dominated those of the others in the ensemble cast. Owen Teague played the son in this story. He is far from the best-known name in the one-hour and 59-minute film. Michael Morris directed. It's worth mentioning that Morris was the executive producer of the 2016 series “Bloodlines,” in which Owen Teague appeared as Young Danny. He found a script from a talented writer (Ryan Binaco) that spoke to him, because of events of his own childhood, and he knew that Andrea Riseborough was right for the lead. She certainly is, as she shows no vanity whatsoever in depicting a woman who hits rock bottom and then must try to scramble her way back to the top. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SwaFEUNXMVQ The film is based on the real-life story of a West Texas single mom who won the lottery and lost it all to her addiction to alcohol. The film had a very personal connection for its director, whose mother suffered from alcoholism. Oscar winner Allison Janney (“I, Tonya!”), Stephen Root (the stapler guy in “Office Space”), and Marc Maron (“G.L.O.W.”), who also executive produced, have leads. Royal is portrayed by Andre Royo (“The Wire”), also a fine character actor on stage and screen and a writer. But the film's lead (Leslie) is Andrea Riseborough, who has been acting since she was 7 years old, which means 36 years. The film stars Andrea Riseborough, a British actress who has been hailed by the Sunday “Times” as one of Britain’s rising young stars, along with such other luminaries as Hugh Dancy and Eddie Redmayne. She graduated from the London Academy of Royal Arts (RADA) in 2005, but her West Texas accent is completely convincing. The script is courtesy of screenwriter Ryan Binaco; the Cinematographer is Larkin Seiple. Riseborough was so good in the part that other actors and actresses (Helen Hunt, Cate Blanchett, Ed Norton) sang her praises on social media and even had some private screenings at their homes to tout her work. All of this was done more-or-less without any active lobbying from Riseborough, herself, but it was aimed at voting members of the Screen Actors' Guild. And that set off a backlash against her totally unexpected nomination for an Oscar when two prominent black actresses who had been expected to earn nods did not. Investigations were held to see if any "rules" were violated, but, to date, the nomination holds and Andrea Riseborough is, for sure, a rising star whose work will garner more notice in the future. The opening scenes of “To Leslie” show a jubilant young mother celebrating winning $190,000 in the lottery and declaring that drinks are on her. Six years later, she’s broke and the drinks have definitely been plentiful during those years (and mostly consumed by her). We learn that the young mother of the opening scene abandoned her son (Owen Teague as James) and his step-mother (Allison Janney) was forced, along with Dutch (Stephen Root) to raise him, by default. To say that Allison Janney’s character is angry and resentful is an understatement. Andrea's portrayal of a woman who has gotten by on looks and charm but is now past those halcyon days of her youth is intense and convincing. I was reminded of Blanche in "A Streetcar Named Desire" who opines, "I have always depended on the kindness of others" as Leslie's femme fatale vibe begins to wither on her increasingly mature vine. The film depicts Leslie hitting rock bottom and trying to claw her way back to at least the middle. She is extended a lifeline on that bootstrap journey by Marc Maron’s character of Sweeney, the manager of a seedy motel on the edge of town. Sweeney is running it for Andre Royo’s character of Royal. Royal was left the motel by his family but, because he took too much acid in his younger days, it has left him with mental impairments that make Marc Maron’s participation in running the place essential. As Leslie gradually swears off the booze and gets sober, she and Marc Maron’s character and Royal assist her in renovating an ice cream parlor on the edge of town. The happy ending involves, once again, son James (Owen Teague), to whom Leslie turns when things are at their bleakest. All’s well that ends well with this female film equivalent of “Leaving Las Vegas.” The acting was very, very good, although the true story has been told many times previously. (Even “A Star Is Born” touches on the old familiar story of alcoholism.) I did enjoy watching Andre Royo strip nearly naked and race around amongst the cactus and sand of a west Texas prairie, as we are told in the script he is prone to do. Marc Maron’s offer of a job cleaning motel rooms and washing the laundry makes you wonder if he has romantic designs on Leslie and, yes, that seems to be the case as the film winds down. You can watch the film on Prime Video ($6.99) before the Oscar telecast. Then we can all wait and see if Riseborough has any chance of pulling off the greatest upset in Oscar history. Read the full article

0 notes

Text

'‘Mesmerizing Masterpiece’

Gay people are rarely depicted with respect in movies today. Hollywood has often ignored homosexual men that climb back-breaking mountains. Out of shame, filmmakers avoid telling stories about gay lovers calling each other by their name. Despite homosexuality rising in the U.S., movies scarcely shine moonlight on queer people’s plight...

Few films I’ve seen have captured barriers experienced by LGBTQ communities treated as strangers as powerfully as “All of Us Strangers”. Intimate, heartbreaking and sweeping, it captures adversities experienced by LGBTQ communities. Andrew Haigh pays tribute towards gay communities today. Boasting exquisite production-design, thoughtful storytelling and phenomenal performances, it’s a mesmerizing masterpiece. Viewers aren’t required to identify with the LGBTQ community to appreciate it. Ultimately, its universal message has abilities to resonate with everyone impacted by lifelong relations with parents from an early age.

Based on the novel “Strangers”, “All of Us Strangers” chronicles the life of a queer man facing barriers. Andrew Scott embodies Adam, a middle-aged gay man mourning parents’ deaths in 1980’s Britain. To overcome grief, Adam bonds with gay neighbor Harry (Paul Mescal) providing comforting relief. However, Adam’s life changes when he begins envisioning ghosts of parents that died in car crashes years ago. Feeling like a stranger in family, Adam struggles disclosing homosexuality.

Andrew Haigh gravitates towards communities that are gay. A British gay filmmaker, Haigh has often told stories of LGBTQ communities today. His debut “Weekend” examined short-lived romance between gay lovers over a weekend. With “All of Us Strangers”, however, Haigh crafts a period piece. It’s the filmmaker’s attempt dramatizing LGBTQ communities in the 1980’s, but he succeeds. Through spellbinding cinematography, Haigh captures a queer man’s journey. Evoking Ang Lee’s “Brokeback Mountain”, Haigh uses montages to capture bonds between gay lovers. It sparked joyous memories of bonds with a cousin I wasn’t aware kept homosexuality shrouded in secrecy. Montages are complicated. Richard Curtis’ “About Time” suggested, montages elevate time-travel movies. As Spike Jonze’s “Her” demonstrated, montages elevate science-fiction. Nevertheless, it succeeds. Alongside cinematographer Jamie D. Ramsay, Haigh commemorates LGBTQ communities. Haigh captures back-breaking barriers of queer men, manufacturing theatrical viewing.

If stories of queer lovers don’t attract you towards theaters, however, there’s reasons to see “All of Us Strangers”. Accompanied by production-designer Sarah Finlay, Haigh uses symbolism capturing negative impact of homosexuality on parent-child relationships. Throughout the film, Adam’s childhood home symbolizes his sexuality. For instance, symbolism elevates the father conversation scene. During this heartbreaking scene, Adam pulls off intimidating tasks of disclosing sexuality to a father that showcases rare understanding. One appreciates set-design of the house in styles recalling Luca Guadagnino’s “Call Me By Your Name”. Like Elio’s heartbreaking conversation with his father about Oliver, Adam’s dad embraces his sexual orientation. It reminded me of my cousin’s desire to be accepted by his father after revealing sexuality in countries where homosexuality was unaccepted. Moreover, the music is magnificent. Evoking Jonathan Demme’s “Philadelphia”, it captures an era of homophobia. Through phenomenal production-design, Haigh honors queer communities.

Another extraordinary aspect of “All of Us Strangers” is storytelling. Haigh’s screenwriting strength is demonstrating struggles of homosexual men seeking acceptance by silence. In Hollywood, most movies rarely address negative impact of stress on queer people’s success. As a case in point: Bryan Singer’s “Bohemian Rhapsody” depicted Freddie Mercury as an invincible musician overcoming barriers of homosexuality by composing melodies. Fortunately, however, “All of Us Strangers” avoids pitfalls. Inspired by Barry Jenkins’ “Moonlight”, Haigh expertly uses sequences of silence to capture the LGBTQ community’s plight. Like Chiron’s silent withdrawal from his family due to his sexual identity, Adam drifts apart from his family. Silences elevate the scene where Adam says heartbreaking goodbyes to parents that realize his sexuality to be a shocking surprise. It reminded me of broken relationships growing distant from a cousin I appreciated after discovering his sexual identity. Minimal dialogue is tricky. Charlotte Wells’ “Aftersun” suggested scenes of silence elevate dramas about father-daughter relations. As Saim Sadiq’s “Joyland” demonstrated, silence elevates Pakistani transgender dramas. Nevertheless, it succeeds. Through a spectacular screenplay, Haigh commemorates gay communities today.

One admires astonishing performances.

Andrew Scott delivers a career-defining performance as Adam. Scott achieved fame playing a villain seeking to shock on BBC’s series “Sherlock”. Drawing from personal experience, Scott embodies a queer man seeking social acceptance. It’s challenging embodying a gay man during the 1980’s, but Scott succeeds. Evoking Hugh Grant in James Ivory’s “Maurice”, Scott embodies a queer man struggling pursuing homosexual relationships in a world without peace. With mesmerizing expressions, he captures angst, loneliness and resentments of a queer man. It’s a phenomenal performance.

The supporting cast is sensational, building familial bonds. Paul Mescal is phenomenal, demonstrating acknowledgements of a queer man that can’t help but fall in love in a relationship doomed to face downfall. Claire Foy is captivating, showing despair of a mother unable to care for a son that’s queer. Last, Jamie Bell merits acknowledgements. As Adam’s dad, he’s heartbreaking.

Finally, “All of Us Strangers” earns appreciation of viewers for celebrating gay wallflower teenagers. Evoking Stephen Chbosky’s “The Perks of Being a Wallflower”, the film captures barriers of queer teenagers. It tackles universal themes including family, identity and trauma. Viewers aren’t required to identify with LGBTQ communities to appreciate it. Anyone sharing strong bonds with parents at an early age will identify with the film’s message. Therefore, “All of Us Strangers” pleases all viewers.

Fans of LGBTQ Cinema will definitely acknowledge “All of Us Strangers” and so will movie-goers giving acknowledgements to sexuality. A powerful drama, it proves stories of queer men battling homophobia in Philadelphia are worth telling in Cinema. A soul-stirring tribute to queer men whose disclosure of sexuality to family incites institutionalization despair, it could make people aware of a burden that gay communities rarely getting acknowledgements bear.

A magnificent depiction of plight faced by LGBTQ communities beneath moonlight, it’s a marvelous reminder of gay men hiding sexuality in plain sight so that their parents are able to sleep soundly at night.

Like doomed affairs between queer lovers that call each other by their name, it’s a sad reminder of the struggles faced by gay men keeping sexuality shrouded in secrecy to avoid causing their family shame.

If movies can celebrate gay communities breaking backs climbing big mountains today, hopefully it leads people to honor joyous memory of queer people whose sexuality came with a painful price to pay.

As powerful as Adam’s memories of parents which died, it has inspired me to honor a cousin which took pride in sexuality becoming a guide in whom I could confide in countries where queer communities denied equal rights were pushed aside.

5/5 stars'

#Andrew Scott#Paul Mescal#Jamie Bell#Claire Foy#Andrew Haigh#Weekend#All of Us Strangers#LGBTQ+#Strangers#Sarah Finlay#Jamie D. Ramsay#Call Me By Your Name#Aftersun#Sherlock

1 note

·

View note

Text

Gay people are rarely depicted with respect in movies today. Hollywood has often ignored homosexual men that climb back-breaking mountains. Out of shame, filmmakers avoid telling stories about gay lovers calling each other by their name. Despite homosexuality rising in the U.S., movies scarcely shine moonlight on queer people’s plight. On a personal level, I saw a gay cousin’s struggle. In childhood, I met a gay cousin that was misunderstood in a Pakistani neighborhood. As charismatic as Freddie Mercury, he was somebody to love praised by family. A wallflower teenager, he enjoyed activities for the opposite gender. Fond of women’s attire, he was a person my family would admire. It didn’t take long before I bonded with my cousin. I spent every Summer in Canada with a cousin that shaped my persona. I spent every weekend with a cousin that became a friend. Unaware that he was queer, I bonded with a cousin about whom I came to deeply care. However, sexuality ended bonds forever. Due to sexuality, I grew distant from a cousin I used to value. In a matter of months, he went from being a beloved family member to a stranger. Not the cousin I came to adore, he became a stranger I didn’t know anymore. Ousted by his father, his life changed forever. In a joyless land where queer people were banned, he couldn’t take a stand. It wasn’t until the day he moved to Canada that my cousin embraced being gay. Years later, I leant being queer is a burden to bear.

Few films I’ve seen have captured barriers experienced by LGBTQ communities treated as strangers as powerfully as “All of Us Strangers”. Intimate, heartbreaking and sweeping, it captures adversities experienced by LGBTQ communities. Andrew Haigh pays tribute towards gay communities today. Boasting exquisite production-design, thoughtful storytelling and phenomenal performances, it’s a mesmerizing masterpiece. Viewers aren’t required to identify with the LGBTQ community to appreciate it. Ultimately, its universal message has abilities to resonate with everyone impacted by lifelong relations with parents from an early age.

Based on the novel “Strangers”, “All of Us Strangers” chronicles the life of a queer man facing barriers. Andrew Scott embodies Adam, a middle-aged gay man mourning parents’ deaths in 1980’s Britain. To overcome grief, Adam bonds with gay neighbor Harry (Paul Mescal) providing comforting relief. However, Adam’s life changes when he begins envisioning ghosts of parents that died in car crashes years ago. Feeling like a stranger in family, Adam struggles disclosing homosexuality.

Andrew Haigh gravitates towards communities that are gay. A British gay filmmaker, Haigh has often told stories of LGBTQ communities today. His debut “Weekend” examined short-lived romance between gay lovers over a weekend. With “All of Us Strangers”, however, Haigh crafts a period piece. It’s the filmmaker’s attempt dramatizing LGBTQ communities in the 1980’s, but he succeeds. Through spellbinding cinematography, Haigh captures a queer man’s journey. Evoking Ang Lee’s “Brokeback Mountain”, Haigh uses montages to capture bonds between gay lovers. It sparked joyous memories of bonds with a cousin I wasn’t aware kept homosexuality shrouded in secrecy. Montages are complicated. Richard Curtis’ “About Time” suggested, montages elevate time-travel movies. As Spike Jonze’s “Her” demonstrated, montages elevate science-fiction. Nevertheless, it succeeds. Alongside cinematographer Jamie D. Ramsay, Haigh commemorates LGBTQ communities. Haigh captures back-breaking barriers of queer men, manufacturing theatrical viewing.

If stories of queer lovers don’t attract you towards theaters, however, there’s reasons to see “All of Us Strangers”. Accompanied by production-designer Sarah Finlay, Haigh uses symbolism capturing negative impact of homosexuality on parent-child relationships. Throughout the film, Adam’s childhood home symbolizes his sexuality. For instance, symbolism elevates the father conversation scene. During this heartbreaking scene, Adam pulls off intimidating tasks of disclosing sexuality to a father that showcases rare understanding. One appreciates set-design of the house in styles recalling Luca Guadagnino’s “Call Me By Your Name”. Like Elio’s heartbreaking conversation with his father about Oliver, Adam’s dad embraces his sexual orientation. It reminded me of my cousin’s desire to be accepted by his father after revealing sexuality in countries where homosexuality was unaccepted. Moreover, the music is magnificent. Evoking Jonathan Demme’s “Philadelphia”, it captures an era of homophobia. Through phenomenal production-design, Haigh honors queer communities.

Another extraordinary aspect of “All of Us Strangers” is storytelling. Haigh’s screenwriting strength is demonstrating struggles of homosexual men seeking acceptance by silence. In Hollywood, most movies rarely address negative impact of stress on queer people’s success. As a case in point: Bryan Singer’s “Bohemian Rhapsody” depicted Freddie Mercury as an invincible musician overcoming barriers of homosexuality by composing melodies. Fortunately, however, “All of Us Strangers” avoids pitfalls. Inspired by Barry Jenkins’ “Moonlight”, Haigh expertly uses sequences of silence to capture the LGBTQ community’s plight. Like Chiron’s silent withdrawal from his family due to his sexual identity, Adam drifts apart from his family. Silences elevate the scene where Adam says heartbreaking goodbyes to parents that realize his sexuality to be a shocking surprise. It reminded me of broken relationships growing distant from a cousin I appreciated after discovering his sexual identity. Minimal dialogue is tricky. Charlotte Wells’ “Aftersun” suggested scenes of silence elevate dramas about father-daughter relations. As Saim Sadiq’s “Joyland” demonstrated, silence elevates Pakistani transgender dramas. Nevertheless, it succeeds. Through a spectacular screenplay, Haigh commemorates gay communities today.

One admires astonishing performances.

Andrew Scott delivers a career-defining performance as Adam. Scott achieved fame playing a villain seeking to shock on BBC’s series “Sherlock”. Drawing from personal experience, Scott embodies a queer man seeking social acceptance. It’s challenging embodying a gay man during the 1980’s, but Scott succeeds. Evoking Hugh Grant in James Ivory’s “Maurice”, Scott embodies a queer man struggling pursuing homosexual relationships in a world without peace. With mesmerizing expressions, he captures angst, loneliness and resentments of a queer man. It’s a phenomenal performance.

The supporting cast is sensational, building familial bonds. Paul Mescal is phenomenal, demonstrating acknowledgements of a queer man that can’t help but fall in love in a relationship doomed to face downfall. Claire Foy is captivating, showing despair of a mother unable to care for a son that’s queer. Last, Jamie Bell merits acknowledgements. As Adam’s dad, he’s heartbreaking.

Finally, “All of Us Strangers” earns appreciation of viewers for celebrating gay wallflower teenagers. Evoking Stephen Chbosky’s “The Perks of Being a Wallflower”, the film captures barriers of queer teenagers. It tackles universal themes including family, identity and trauma. Viewers aren’t required to identify with LGBTQ communities to appreciate it. Anyone sharing strong bonds with parents at an early age will identify with the film’s message. Therefore, “All of Us Strangers” pleases all viewers.

Fans of LGBTQ Cinema will definitely acknowledge “All of Us Strangers” and so will movie-goers giving acknowledgements to sexuality. A powerful drama, it proves stories of queer men battling homophobia in Philadelphia are worth telling in Cinema. A soul-stirring tribute to queer men whose disclosure of sexuality to family incites institutionalization despair, it could make people aware of a burden that gay communities rarely getting acknowledgements bear.

A magnificent depiction of plight faced by LGBTQ communities beneath moonlight, it’s a marvelous reminder of gay men hiding sexuality in plain sight so that their parents are able to sleep soundly at night.

Like doomed affairs between queer lovers that call each other by their name, it’s a sad reminder of the struggles faced by gay men keeping sexuality shrouded in secrecy to avoid causing their family shame.

If movies can celebrate gay communities breaking backs climbing big mountains today, hopefully it leads people to honor joyous memory of queer people whose sexuality came with a painful price to pay.

As powerful as Adam’s memories of parents which died, it has inspired me to honor a cousin which took pride in sexuality becoming a guide in whom I could confide in countries where queer communities denied equal rights were pushed aside.

5/5 stars'

#Andrew Haigh#Andrew Scott#Paul Mescal#Claire Foy#Jamie Bell#All of Us Strangers#Strangers#Taichi Yamada#Weekend#Jamie D. Ramsay#LGBTQ#Sarah Finlay

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

'Gay people are rarely depicted with respect in movies today. Hollywood has often ignored homosexual men that climb back-breaking mountains. Out of shame, filmmakers avoid telling stories about gay lovers calling each other by their name. Despite homosexuality rising in the U.S., movies scarcely shine moonlight on queer people’s plight. On a personal level, I saw a gay cousin’s struggle. In childhood, I met a gay cousin that was misunderstood in a Pakistani neighborhood. As charismatic as Freddie Mercury, he was somebody to love praised by family. A wallflower teenager, he enjoyed activities for the opposite gender. Fond of women’s attire, he was a person my family would admire. It didn’t take long before I bonded with my cousin. I spent every Summer in Canada with a cousin that shaped my persona. I spent every weekend with a cousin that became a friend. Unaware that he was queer, I bonded with a cousin about whom I came to deeply care. However, sexuality ended bonds forever. Due to sexuality, I grew distant from a cousin I used to value. In a matter of months, he went from being a beloved family member to a stranger. Not the cousin I came to adore, he became a stranger I didn’t know anymore. Ousted by his father, his life changed forever. In a joyless land where queer people were banned, he couldn’t take a stand. It wasn’t until the day he moved to Canada that my cousin embraced being gay. Years later, I leant being queer is a burden to bear.

Few films I’ve seen have captured barriers experienced by LGBTQ communities treated as strangers as powerfully as “All of Us Strangers”. Intimate, heartbreaking and sweeping, it captures adversities experienced by LGBTQ communities. Andrew Haigh pays tribute towards gay communities today. Boasting exquisite production-design, thoughtful storytelling and phenomenal performances, it’s a mesmerizing masterpiece. Viewers aren’t required to identify with the LGBTQ community to appreciate it. Ultimately, its universal message has abilities to resonate with everyone impacted by lifelong relations with parents from an early age.

Based on the novel “Strangers”, “All of Us Strangers” chronicles the life of a queer man facing barriers. Andrew Scott embodies Adam, a middle-aged gay man mourning parents’ deaths in 1980’s Britain. To overcome grief, Adam bonds with gay neighbor Harry (Paul Mescal) providing comforting relief. However, Adam’s life changes when he begins envisioning ghosts of parents that died in car crashes years ago. Feeling like a stranger in family, Adam struggles disclosing homosexuality.

Andrew Haigh gravitates towards communities that are gay. A British gay filmmaker, Haigh has often told stories of LGBTQ communities today. His debut “Weekend” examined short-lived romance between gay lovers over a weekend. With “All of Us Strangers”, however, Haigh crafts a period piece. It’s the filmmaker’s attempt dramatizing LGBTQ communities in the 1980’s, but he succeeds. Through spellbinding cinematography, Haigh captures a queer man’s journey. Evoking Ang Lee’s “Brokeback Mountain”, Haigh uses montages to capture bonds between gay lovers. It sparked joyous memories of bonds with a cousin I wasn’t aware kept homosexuality shrouded in secrecy. Montages are complicated. Richard Curtis’ “About Time” suggested, montages elevate time-travel movies. As Spike Jonze’s “Her” demonstrated, montages elevate science-fiction. Nevertheless, it succeeds. Alongside cinematographer Jamie D. Ramsay, Haigh commemorates LGBTQ communities. Haigh captures back-breaking barriers of queer men, manufacturing theatrical viewing.

If stories of queer lovers don’t attract you towards theaters, however, there’s reasons to see “All of Us Strangers”. Accompanied by production-designer Sarah Finlay, Haigh uses symbolism capturing negative impact of homosexuality on parent-child relationships. Throughout the film, Adam’s childhood home symbolizes his sexuality. For instance, symbolism elevates the father conversation scene. During this heartbreaking scene, Adam pulls off intimidating tasks of disclosing sexuality to a father that showcases rare understanding. One appreciates set-design of the house in styles recalling Luca Guadagnino’s “Call Me By Your Name”. Like Elio’s heartbreaking conversation with his father about Oliver, Adam’s dad embraces his sexual orientation. It reminded me of my cousin’s desire to be accepted by his father after revealing sexuality in countries where homosexuality was unaccepted. Moreover, the music is magnificent. Evoking Jonathan Demme’s “Philadelphia”, it captures an era of homophobia. Through phenomenal production-design, Haigh honors queer communities.

Another extraordinary aspect of “All of Us Strangers” is storytelling. Haigh’s screenwriting strength is demonstrating struggles of homosexual men seeking acceptance by silence. In Hollywood, most movies rarely address negative impact of stress on queer people’s success. As a case in point: Bryan Singer’s “Bohemian Rhapsody” depicted Freddie Mercury as an invincible musician overcoming barriers of homosexuality by composing melodies. Fortunately, however, “All of Us Strangers” avoids pitfalls. Inspired by Barry Jenkins’ “Moonlight”, Haigh expertly uses sequences of silence to capture the LGBTQ community’s plight. Like Chiron’s silent withdrawal from his family due to his sexual identity, Adam drifts apart from his family. Silences elevate the scene where Adam says heartbreaking goodbyes to parents that realize his sexuality to be a shocking surprise. It reminded me of broken relationships growing distant from a cousin I appreciated after discovering his sexual identity. Minimal dialogue is tricky. Charlotte Wells’ “Aftersun” suggested scenes of silence elevate dramas about father-daughter relations. As Saim Sadiq’s “Joyland” demonstrated, silence elevates Pakistani transgender dramas. Nevertheless, it succeeds. Through a spectacular screenplay, Haigh commemorates gay communities today.

One admires astonishing performances.

Andrew Scott delivers a career-defining performance as Adam. Scott achieved fame playing a villain seeking to shock on BBC’s series “Sherlock”. Drawing from personal experience, Scott embodies a queer man seeking social acceptance. It’s challenging embodying a gay man during the 1980’s, but Scott succeeds. Evoking Hugh Grant in James Ivory’s “Maurice”, Scott embodies a queer man struggling pursuing homosexual relationships in a world without peace. With mesmerizing expressions, he captures angst, loneliness and resentments of a queer man. It’s a phenomenal performance.

The supporting cast is sensational, building familial bonds. Paul Mescal is phenomenal, demonstrating acknowledgements of a queer man that can’t help but fall in love in a relationship doomed to face downfall. Claire Foy is captivating, showing despair of a mother unable to care for a son that’s queer. Last, Jamie Bell merits acknowledgements. As Adam’s dad, he’s heartbreaking.

Finally, “All of Us Strangers” earns appreciation of viewers for celebrating gay wallflower teenagers. Evoking Stephen Chbosky’s “The Perks of Being a Wallflower”, the film captures barriers of queer teenagers. It tackles universal themes including family, identity and trauma. Viewers aren’t required to identify with LGBTQ communities to appreciate it. Anyone sharing strong bonds with parents at an early age will identify with the film’s message. Therefore, “All of Us Strangers” pleases all viewers.

Fans of LGBTQ Cinema will definitely acknowledge “All of Us Strangers” and so will movie-goers giving acknowledgements to sexuality. A powerful drama, it proves stories of queer men battling homophobia in Philadelphia are worth telling in Cinema. A soul-stirring tribute to queer men whose disclosure of sexuality to family incites institutionalization despair, it could make people aware of a burden that gay communities rarely getting acknowledgements bear.

A magnificent depiction of plight faced by LGBTQ communities beneath moonlight, it’s a marvelous reminder of gay men hiding sexuality in plain sight so that their parents are able to sleep soundly at night.

Like doomed affairs between queer lovers that call each other by their name, it’s a sad reminder of the struggles faced by gay men keeping sexuality shrouded in secrecy to avoid causing their family shame.

If movies can celebrate gay communities breaking backs climbing big mountains today, hopefully it leads people to honor joyous memory of queer people whose sexuality came with a painful price to pay.

As powerful as Adam’s memories of parents which died, it has inspired me to honor a cousin which took pride in sexuality becoming a guide in whom I could confide in countries where queer communities denied equal rights were pushed aside.

5/5 stars'

#All of Us Strangers#Andrew Scoty#Paul Mescal#Claire Foy#Jamie Bell#Andrew Haigh#Strangers#Taichi Yamada#LGBTQ

1 note

·

View note

Text

'...JAMIE D. RAMSAY SASC ON ALL OF US STRANGERS All of Us Strangers, Andrew Haigh’s deeply personal portrait of love and loss, was the big winner at the British Independent Film Awards 2023, earning seven awards including Best Cinematography for Jamie D. Ramsay SASC.

Keen to avoid being too heavy handed with nostalgia, Ramsay opts for a subtle and organic visual language to bring this extraordinary story – based on Taichi Yamada’s novel Strangers – to the screen...'

0 notes