#both of those books are indie published and relatively short

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Note

Hi Jenn,

Do people in the industry still use the term “traditional publishing”? I was told that was an incorrect term and that it should be referred to as “trade publishing.”

Do you know why some people consider the term offensive?

Thanks!

OK so here's the thing:

Publishing is a vast industry and within it there are several different "markets" - that is, places that a given book might be created for and sold.

The actual correct term for the branch of the publishing industry I work in, and most authors and illustrators I know work in, and most publishers we work with, is Trade Publishing.

Trade Publishers -- like most imprints of Penguin Random House and Macmillan and Chronicle Books and Candlewick, etc, basically all the publishers you normally hear about -- mostly publish "into the Trade Market." The "Trade Market" is regular bookstores. Pretty much 99% of the books you see on the shelves in B&N or whatever are Trade Books.

There are other markets! For example(s), Educational Publishing is its own market, with its own publishers and its own norms. Religious Publishing is its own market, with its own publishers and its own norms. There are obviously Trade Publishers who also publish "religious" or "educational" type books -- but they are still TRADE BOOKS, they are the religious and educational books you'd see at the regular bookstore. Truly Religious Publishers or Educational Publishers are peddling their books primarily through their own separate distribution channels, and they don't normally work with agents in the same way as Trade Publishers do. If you only shop in a regular bricks-and-mortar bookstore, you may never even see actual Religious Market specific or Ed Market specific books, they would be more likely found in a Religious Bookstore or through a Library or some such. (Though of course, all of them are available online!)

(There are other Markets, too -- like "Mass Market" refers to both a kind of book -- those short chunky paperbacks like they sell in the supermarket or drug store -- and also a Market, specifically, "places like the supermarket or drugstore". Some/most of these books originate in the Trade Market - some are made specifically for the Mass Market).

"Traditional" publishing is a term that sprung up in relatively recent years (like, the past 20 years or so???) -- to differentiate it from Self-Publishing/"Indie Publishing" -- so often on websites where, for example, people are advocating for self-publishing options, they will say "We are breaking the mold of Traditional Publishing!" or whatever. It basically became shorthand for "the opposite of indie publishing"***.

Now, I understand that the vast majority of people saying "Traditional Publishing" aren't actually dissing or dismissing it -- in fact, I have definitely said it as well when I am for some reason talking about both types and want to make my point clear. HOWEVER, some people are offended. (OK, I'll be specific: The only place I have ever personally seen anyone be offended is on the Absolute Write forum -- which I find to be a delightful forum generally, but they are quite pedantic about this terminology!)

So: Long story short: It's called Trade Publishing. If you want to be right, call it Trade Publishing. However, if you are specifically trying to differentiate Trade Publishing from Self-Publishing, nobody will actually care if you say Traditional Publishing, unless you are around people who are being unusually pedantic.

***

*** the one that actually gets my goat WAY more than "traditional" instead of "Trade" is INDIE publishing instead of Self-Publishing. The reason for this: INDIE means something in the Trade Publishing world. INDIE BOOKSTORES are non-chain bookstores. INDIE PUBLISHERS are privately-owned publishers. Indie Bookstores and Indie Publishers have a very rough go of it in the world and are generally doing work that big corporations could and would never do; they are often daring and special, and I find it extremely annoying that some people have co-opted this language to mean something that isn't the thing it means.

Note that I AM NOT annoyed by indivuduals who are self-publishing and want to say they are "indie publishing!" or "independently publishing!" -- I was at first, 20 years ago, don't get me wrong, but this is a normal term at this point, clearly people like saying it, and it's a perfectly valid and cool thing to do if its what you want to do! So I'm not mad at those people DON'T COME AT ME.

Who I AM mad at are companies who "help" self-published authors under the guise of being "indie publishers" -- because often the people who are pushing this language are actually selling some sort of scam where they get authors to pay them a grip of money to "publish their book" when actually the authors would be better off completely doing it themselves. So they are calling themselves "INDIE PUBLISHERS" but in fact they are SCAM PUBLISHERS, SCHMUBLISHERS, VANITY PRESSES, etc, and meanwhile actual Indie Publishers got their thing taken away from them. :( -- however, the ship has kinda sailed on this, so, whatever I guess. :(

12 notes

·

View notes

Note

Aww it makes me really happy too, from the reader's side of things, to know my support has been so meaningful to you 🥺 (and to even be complimented on my interpretations by the writer herself). Best of luck to you and pulling through the week <3

I totally forgot original works barely get attention on ao3 (I don't even use the site often) and I literally filtered by original works to find Rust lol.

So in response to "how are you people finding it??": a road to nowhere was the second work to appear when I searched for original work, robot/human relationships, and F/F (I've been scrounging to find any piece of fiction, officially published or not, that fits this niche) and thought "oh, the first in this series is a nice little 7k word short story to read before I go to sleep at a normal and functional time :)" and then was awake at 4am not able to shut my brain up about Rexzee and sleep. I had class the next morning and could barely focus due to sleep deprivation and thinking about robot wife hand motifs.

Really exposing which ao3 account I am rn by my style of long-winded rambling. Anyways, life changing pieces of fiction <3

This is actually extremely interesting-- this means I've done a pretty good job of making sure the target audiences can find it (also I know exactly what you mean and it is a crying shame there is so little original robot/human femslash stuff out there it KILLS me). I'm really glad you were able to find it and that also you like it so much!!!!! I'm having an incredibly awful week for multiple reasons and I've gone back and reread your tags/asks/comments multiple times and it makes me smile and do a little happy-flap every single time. You engage with it in a really genuine and meaningful way and I really love how you've picked up everything I put down plus some stuff I didn't even intend, which as an author is the BEST thing about other people reading your works. Thank you so much for reading Rust, genuinely-- it really makes me so so happy.

#now I'm so curious about what I read into that wasn't intended 👀#also thank you for the rec in the tags. noted >:]#basically the only other stuff I've read so far is The Cybernetic Tea Shop (which I do recommend)#and Lesbian Robots from Space (which was a lot less focused on the title topic than you would expect but it was still fun)#both of those books are indie published and relatively short

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Interview #495: Quince Pan

q: Give a short introduction of yourself: a: I am Quince Pan, a documentary photographer born in 2000, currently based in Singapore. I am now waiting to enter university to study Philosophy, Politics and Economics.

q: What is your series "JBM" about? What was the process of making the series? a: “JBM”, my family’s abbreviation of “Jalan Bukit Merah”, is a documentary photo project centred on my maternal grandmother, Lau Giok Niu, her cultural heritage and her HDB flat where I spent my childhood under her care. It is my first exhibited series and also my first serious long-term documentary project.

In 2015, I followed my grandmother to visit her hometown in Fengwei, Quangang District, Quanzhou City, Fujian, China. Bringing my camera along on the trip, I noticed that instead of shooting purely for fun or beauty, I would include certain objects (for example, a calendar on the wall) in my frames because they had historical significance. I submitted those Fengwei photos as my portfolio for the 2016 Noise Art Mentorship (Photography and Moving Images). I got selected, and my mentor, Jean Qingwen Loo, urged me to pursue a project which I could speak authentically about. Through her criticism, I learnt to further prioritise meaning over style. My grandmother and my childhood were topics close to my heart, especially as she cared for me during my childhood and gave me the gift of the 头北 Thâu-pak dialect, a unique variant of Hokkien from the Quangang District. Eventually, “JBM” was born as my mentorship capstone, and was exhibited at the “Between Home and Home” Noise Art Mentorship Showcase at Objectifs in 2017. I haven’t stopped shooting; that’s why it’s an ongoing long-term project!

“JBM” contains a range of visual styles, ranging from photojournalistic fly-on-the-wall documentations of heated family discussions and visits by distant relatives from China to more tender images of sunlight at the void deck where my late grandfather’s wake was held in 2006. Rituals and festivities are anthropologically significant, so I pay particular attention to Chinese New Year, the Qing Ming Festival and the Winter Solstice, which my family celebrates. I also look at how other photographers document their families: Bob Lee, Nicky Loh, Bernice Wong, Brian Teo and Nancy Borowick.

More broadly, “JBM'' extends beyond photography and is a family history project. Since 2013, I have been researching the Quangang district, 头北 Thâu-pak dialect and my grandmother’s clan. I discovered that other descendants from her clan established an ancestral temple in Singapore, which initially stood on Craig Road but is now housed in a flat in Telok Blangah. I already did some fieldwork, interviews and preliminary documentation, which led to an article I published in April 2021 in Daojia: Revista Eletrônica de Taoismo e Cultura Chinesa. Maybe I will explore this in greater depth in future photo projects!

q: How did you get into photography? a: When I was around seven years old, I loved to play with my father’s Fujifilm compact. As a young student, I hadn’t heard of terms such as “light painting”, “Dutch angle” and “rule of thirds”, but those were the techniques I subconsciously used in my photographs.

I entered the Noise Art Mentorship, as previously mentioned. During the school holidays, I worked as a media intern at Logue and as an assistant at Objectifs for the “Passing Time” exhibition and book by Lui Hock Seng. Through these work experiences, I learnt so much from Jean Loo, Yang Huiwen, Ryan Chua, Lim Mingrui and Chris Yap: news angles, editorial writing, scanning and touching up negatives and slides, colour management for print, liaising with clients and issuing invoices, among other skills. As part of the Noise Art Mentorship, I was given a copy of “+50” by the PLATFORM collective, which opened my eyes to diverse approaches within the documentary genre. I started to regularly attend talks at Objectifs and DECK, where I got to know people in the local photography scene, particularly in the documentary tradition.

q: You also do videography. How do you see it in relation to your photography? a: Videography requires a different way of seeing and thinking compared to photography, because video has additional temporal and auditory dimensions. With photography, I don’t have to think about how long I want a scene to be, what foley and B-roll I want to overlay, or have a storyboard in my head before heading out to shoot. In that sense, photography is more reactive to and receptive of situational contingencies because it requires less pre-planning.

Also, photography can be a solitary endeavour, but it is quite difficult to make films alone, and the schoolmates I used to make films with have since embarked on separate paths in life. However, photography and videography share the same basics as visual media: composition and sequencing.

Fundamentally, I see myself as a documentarian, and this applies to any medium I work in, be it photography or videography, or even writing. The end goal is to record and share history by telling stories from lesser-known perspectives. Thus, the topics of my video projects are similar to the topics of my photo projects; sometimes I do both side by side! The films I made were all documentary shorts of places which do not exist anymore, such as the Hup Lee coffee shop at 114 Jalan Besar and the old Sembawang Hot Spring before NParks took over the site from MINDEF and redeveloped it.

Currently, I am working as a videographer for Sing Lit Station’s poetry.sg archive. Thankfully, this job can be done solo!

q: What or who is inspiring you right now? a: Bob Lee, for being an amazing father and spreading hope and joy to others through his images. Alex and Rebecca Webb, for pairing literature with photography. Tom Brenner, for approaching photojournalism like street photography. Sim Chi Yin, for her international achievements and being both an academic and a practitioner. Brian Teo, for being an eminent contemporary. Last but not least, Kevin WY Lee’s advice, “CPR: Craft, Point, Rigour”, which I try to benchmark my work against.

q: Upcoming projects or ideas? a: Nothing concrete on my mind so far. I am just going to see where life takes me and what topics life makes me want to explore or talk about.

q: Any music to recommend? a: First and foremost, my fight song: “倔强 Stubborn” by Mayday. A close second, Queen’s 1986 “Under Pressure” live performance at Wembley is a transformative experience. The catchy “他夏了夏天 He Summered Summer” by Sodagreen brings out the grandeur in the mundane. “Silhouette” by KANA-BOON and “Everybody’s Changing” by Keane remind me of the fragility of life and time. I also like The Fray, Kings of Leon, Last Dinosaurs, Stephanie Sun, Tanya Chua, and the Taiwanese indie band DSPS.

his website.

Get more updates on our Facebook page and Instagram.

267 notes

·

View notes

Text

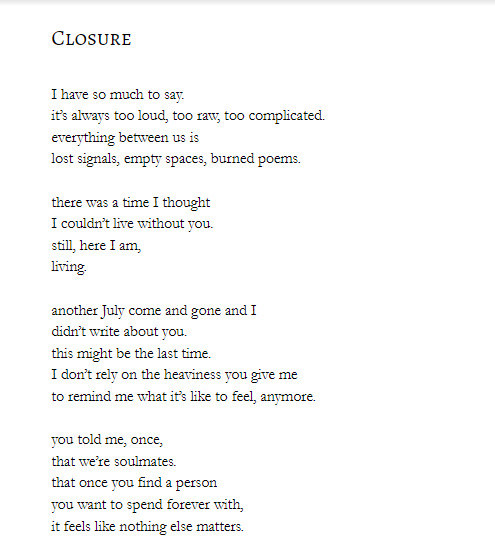

Writing My Obituary (context on my weird poetry collection)

I realized today that I very casually bring up my poetry collection all the time and a large majority of my followers have no clue what I’m talking about, so here’s a WMO explanation post thing! I should definitely give a content warning though: this book deals with suicide, abuse (both physical and emotional, by both parents and other people), homophobia and transphobia, allusions to major appetite and stomach issues (which while reading sound a lot like eating disorders), toxic relationships, just a lot of really heavy emotions in general. Please don’t read the book or this post if those things could trigger you. This post also ended up super long, so the rest is under the cut.

So. first thing’s first, this collection is being published by Pure Print Publishing this fall (due to covid there aren’t any exact dates available). I didn’t query it, someone reached out to me after reading my poems on Instagram, hearing that they were in an unpublished collection, and basically connected me with their friend who runs the indie publishing house and is an author himself.

A big part of the reason this book is so difficult to talk about in context is because that requires getting pretty vulnerable - most of this book is just me dealing with everything I’ve struggled with over the last 4 years of my life. So if there’s discussion about the book in the replies, please keep it to the content of the book and not the validity of these experiences or details of things that happened to me.

The collection is about me and my journey from 13 to 17, starting with my suicide attempt at 13. There are several poems from around that time in my life, but they’ve changed a lot over the four years of editing. However, you can definitely still see changes in the way I write and the way I approach poetry by the end of the book - which was the goal. The book is centered around learning about identity, about how relationships should work, about friendships, about learning to handle mental and chronic illness, and above all, growing. There’s really no “breaking point” where everything about the way I write changes all at once, so in context, the change is almost difficult to see. So to sort of represent these changes, I’m putting a poem from the beginning, from the middle, and from the end all right next to each other (and some bonus analysis of my own poetry!).

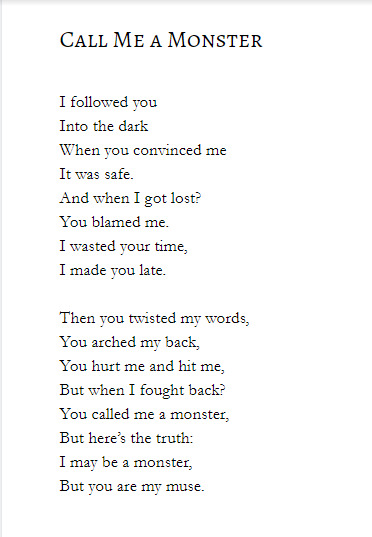

Call me a monster is probably the most stark change from the past to the present. I almost never rhyme my poems anymore and if I do, they’re fleeting and mostly for rhythm. The lines are also extremely short, which I only do now when it really fits - in general, I make an effort to avoid consistently short lines. I like to tell myself that it’s symbolism I did on purpose to represent how all over the place my brain was, hopping from one thought to the next, but I don’t think it’s symbolism. I think my brain was really too jumbled to have more than five words in a line.

I also took my own poems very seriously back then - writing a poem was an Occasion, so the first letter of each of those lines is capitalized like I’m some sort of English classics major. Both stanzas are also the same length (I still do that now sometimes, but back then it was in so many of my poems that I think I thought it was a requirement). Basically, I wrote this like I was going to turn it in somewhere.

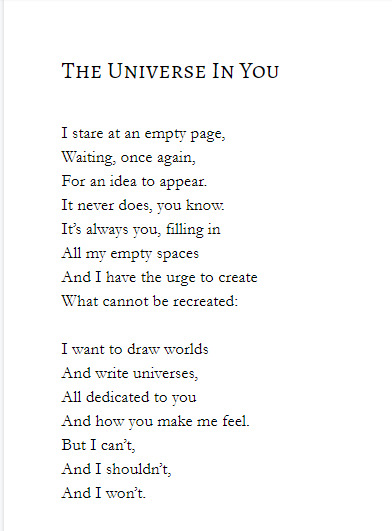

Still pretty heavy on the capitalization here, but I definitely got more flexible with stanza length and slightly longer lines (7 whole words, yay!). This poem was somewhat of a turning point for me, basically realizing that I could not only vent through poetry, but still make it poetic and artistic in a lot of ways, and also explore contrast in my own emotions and conflicting feelings. For some reason, prior to this, I thought a poem could only be one emotion at a time, but now I think a poem can be one topic and the way multiple or conflicting emotions revolve around it. This is also one of the first poems I wrote that I was proud of from beginning to end.

This poem isn’t totally representative of the last couple changes I want to talk about (especially line length - for being relatively recent the lines are still pretty short), but I don’t want to use too many poems that haven’t been posted online before and this one has been posted and read aloud on an Instagram live, minus one stanza I added, which I’ll get to. I also wanted to choose this one because it has a direct reference to The Universe In You and several other poems, which gives me a chance to talk about how much I love referencing my other poetry in my poetry. Buckle up, this one might be long.

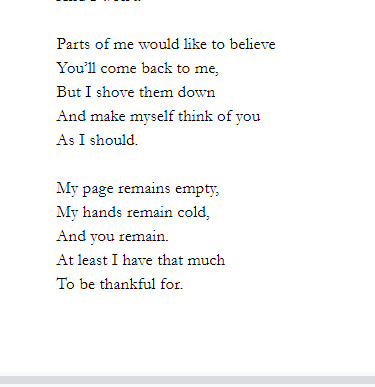

By this point, I had pretty much realized that there actually aren’t any rules at all. I’ve figured out what I want to say and I’ll say it however the hell I want to - I don’t need to capitalize things unless it suits the form, I don’t have to be totally consistent, I can repeat things as much as I want. I reached back into my 15 year old angst for this one, though, so I could more properly write about the relationship in a way that made sense.

Now, I could honestly write a whole other book about how I reference other poems in each poem, but for now I’ll just break down the ones here.

Sort of a half reference right at the beginning: I have so much to say. I bring that up in different words in so many poems, both about my relationship and my dad. This is probably because, growing up as someone who had a speech impediment (meaning I talked too much no matter how little I said because of how long it took to say it), I always felt like I never had the space to say everything I wanted. It’s brought up in at least 3 other poems.

lost signals: a direct reference to my poem Thread Unavailable:

We’re riding down a dirt road in the middle of a conversation and lost signal. Message failed.

empty spaces: a reference to The Universe In You!! Pretty much the whole reason I included this poem.

burned poems: this one is basically just a reference to all the poems in the collection that are breakup poems, or poems where I directly addressed my ex saying don’t read this, you don’t have to read this, I shouldn’t have written this, etc. Specifically, A Long and Lonely Letter, Tired Eyed (The Homecoming Poem), and The Poem That Shouldn’t Exist.

another July come and gone and I didn’t write about you: this reference is hard to really understand the context of unless you know me in real life, but in two other poems I mention the month of July, in a couple others I reference summer, but there are dozens of poems that didn’t make it into my cut of the collection that talk about July. Basically, in context of the relationship, it was the only time we were actually happy and we split up and got back together over and over trying to replicate that fleeting, 30 day feeling that was overtaken by school, seasonal depression, and our own instability as people. For so long, all I could think about was that one month, and that line was my way of showing how I was done writing about it.

you told me, once, that we’re soulmates: this entire little stanza is directly copied from Tired Eyed (The Homecoming Poem). In order to continue talking about it I’ll throw a piece of that here:

If you want to come back, be sure of me. Be sure of yourself. I don’t want to be a consequence of your impulses.

You told me, once, that we’re soulmates. That once you find a person you want to spend forever with, it feels like nothing else matters. Do you believe that like I do?

That’s just a really short chunk of a really long poem, but basically the re-use of that section goes to say that me truly believing nothing else mattered was not good and extremely unhealthy. I put it there even though the poem was just fine without it because I really wanted to get that message across, especially since most of my target audience falls between middle and high school.

I know love in so many shades and I give it in every color: this references a couple different poems that aren’t in the collection, but in terms of the book, it’s a reference to Red, Like You, which is about color association and love and stuff? I I still don’t totally get it. I say in the poem that I don’t totally get it. No one totally gets it, but all in all I went from loving just one person in just one way to loving everyone in tons of different ways and realizing that those other types of love are just as, if not more, fulfilling to me, and that romance is not the be-all end-all of love and happiness.

All the other references are repetitions so I’ve pretty much already explained those. But anyway, that’s my book! It has 77 poems total, quite a few of them more than a page, and some that are probably several pages once in paperback format because, you know, I never shut up. Since I did my mini beta reading round (I got a lot of necessary feedback but that was so much to keep track of, I’ll probably just get a couple feedback partners next time), I’ve cut 34 poems and added 16 newer ones, edited the crap out of the whole book, and gotten the perspective of a professional editor.

This book, even though there’s a lot of it I’ve grown out of, is super important to me and it’s so hard to let it go. Part of me wants to keep this book going forever and just keep growing until it has thousands of poems, but all of these “character arcs” in my life are finished. I left my toxic relationship and friendships, I figured out my gender and sexuality, I learned how to love openly, I cut off my dad for good. There’s obviously always more to learn about my relationships with these other people and myself, and I do that unconsciously every day. But in all honesty, I have nothing left to say about these people or events that would change the conclusions I’ve already come to - they would only further prove them to be true.

I absolutely always want to talk about this book, so if you have any questions, send an ask! Also feel free to scroll through the poetry tag on my blog and ask me about any poems I have posted there, there are a few that I’ve written since the completion of the collection that’ll (most likely) end up in whatever I write next. Basically, I’m obsessed with poetry and want to talk about it all the time. Please ask me about it.

19 notes

·

View notes

Note

hi! i was wondering if you knew what would be an appropriate wage to pay a sensitivity reader to read a fanfic?

I absolutely adore this question and this initiative. While the mainstream publishing book industry is slooowwwwly growing more comfortable with utilizing sensitivity writers, usage remains relatively rare in other publication avenues (short stories, fiction magazines, self-publication, etc.) Introducing that level of mindfulness into writing/reading fanfiction is really admirable and helps normalize sensitivity readers as another step in the editing process, just like beta readers. On top of that, your initiative to compensate sensitivity readers for their important work demonstrates your clear commitment to writing respectful diversity and recognizing the value of those who help you get there. I can’t say enough how cool it is that you’re reaching out about this.

As to your question itself, I don’t have a solid answer nor personal experience but I do have some references. Let’s look at some professional sensitivity readers’ rates to get an idea of how much their services go for.

Quiethouse Editing’s “minimum rate is $100. Full-length texts usually fall between $0.005 and $0.007 per word, per reader.”

Patrice Williams Marks, author of So You Want to Be a Sensitivity Reader?, charges “a minimum charge of $75 for works under 1000 words” with a case-by-case basis for longer works.

Dax Murray asks “a base $50 for the first 5,000 words. For every word after that I charge an additional $0.0025, rounded up to the nearest cent.” However, fei also write “if you cannot afford my rates and are an indie author or an author who has not yet been published before, I am willing to work out alternative means of compensations (for example, you crochet? I will accept a scarf as payment!).”

Alice of Arctic Books charges $50 for <20000 words, $200 for 20001-60000 words, $250 for 60001-100000 words, and negotiable rates for 100000+ words. Like Murray, she is “willing to negotiate if you are an indie author or a teen author.”

Mary Robinette Kowal, author of The Calculating Stars among other works, pays her sensitivity readers $3 per page. I do want to note that she herself isn’t a sensitivity reader but rather an author within the mainstream publishing industry who’s very open about her usage of sensitivity readers.

Writing Diversely’s Sensitivity Reader Directory features many readers with a variety of rates, though most tend to charge in the ballpark of $250 for a novel-length work.

Obviously, there’s a fair amount of variety here, as well as a bit of flexibility for non-professional writers. None of these sensitivity writers come cheap, more so if you’re writing extended novel-length fanfic rather than one-shots.

All that being said, I doubt you’re seeking out a professional sensitivity writer. I do think these numbers are useful to keep in mind during your search but understand that these are professionals with experience within the industry and in many cases, extensive education in media representation of various identities. In your case, you should look for a sensitivity reader who a) has personal experience with your topic(s) (race, disability, sexuality, religion, etc.) b) is knowledgable about the representation of that topic within fiction and nonfiction media c) understands and is willing to undertake the emotional labor intrinsic to sensitivity reading and finally d) is involved with the fandom in question so they understand the context your fanfic is written within.

Ideally, you find someone who has functioned as a sensitivity reader before and understands everything it entails. If you find someone who matches many of the above suggestions but hasn’t worked as a sensitivity reader before, I’d be sure to direct them to some resources on the profession so they know what’s expected of them and what they’re getting into (including an overview of professional sensitivity reader’s rates, so you both understand the value of good sensitivity reading). While I don’t think either of you should expect to work with a professional rate, it’s nevertheless a good reference.

From there, you two can discuss payment, taking into account both your personal budget and their experience. If they have prior sensitivity experience, that should be reflected in their payment. If you think this is going to be a one-off arrangement, a lump sum fee is probably the most reasonable; if you plan to write additional works within the fandom that would likewise need sensitivity reading, you two can discuss a standing agreement and work out a per word rate.

I know I didn’t really provide a solid answer to your question but I hope that helps nevertheless. Best of luck to you and your writing!

7 notes

·

View notes

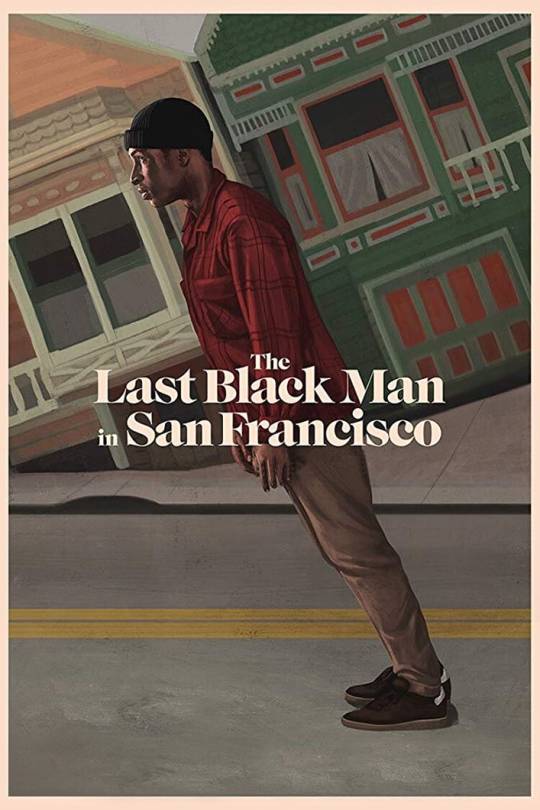

Photo

The Last Artists.

“From the outside it seems like this dream scenario… but the truth is it took years working on drafts and wondering if anyone would ever read them.” —Joe Talbot on The Last Black Man in San Francisco.

A love story to San Francisco, to one grand Victorian house in particular, and to a life-long friendship, The Last Black Man in San Francisco was many years in the making. And it paid off: Joe Talbot picked up the Best Director prize at Sundance 2019 for his debut feature, a story drawn from the life of his best friend (and the film’s leading man), Jimmie Fails. A close-knit family of creatives grew around the project, and became a vital support system for Talbot when his father had a stroke just weeks before the shoot. Since January, critical accolades for the film have snowballed. Most recently, it appeared in our ten highest-rated features for the first half of 2019.

Letterboxd reporter Jack Moulton took the opportunity for a lengthy chat with Talbot about his remarkable debut feature. The interview contains a virtual masterclass in first-time feature film development (and the persistence required to see it through), along with some never-before-seen images shared exclusively with us by Joe. Also: some plot spoilers, which we’ve left until the very end.

Joe Talbot and Jimmie Fails in 2014, photographed by Talbot’s brother, Nat Talbot.

Thanks for agreeing to a good chat with us. Are you on Letterboxd? We have our suspicions that you might be. Joe Talbot: Yeah. I love it. I found Letterboxd before we shot the movie. I use it to save movies to watch for later and look up movies people recommend. Occasionally I read the reviews of films I’ve just watched, they’re often really thoughtful.

Can we share your username? You could be the next Sean Baker. The one I have right now is more of a lurking profile so it’s not very formal. I made one that’s a little more presentable for you under my name.

Are you in San Francisco right now? I am. If you can hear my heavy breathing, I’m actually walking up one of the steeper hills that Jimmie and Montgomery crest in the movie and see the skyline. That’s what I do for every interview, I like to walk up the hill to put me in the film. Just kidding, this is the first time I’ve done it. I’m just walking with a friend and we’re about two thirds of the way up. Woo!

We’ve just published our halfway top 10 of the year. The Last Black Man in San Francisco is in second place, between Avengers: Endgame and Booksmart. How does this make you feel, and how do you cope with reviews (whether they’re full of praise or criticism)? Wow, that means a lot. I find the reviews informative, though have to admit I don’t read too many of them. In general, it’s great to know that there are people that love movies enough to get into debates and write passionately, either about how much they loved them or didn’t like them at all. Having platforms like Letterboxd and finding those communities online can be really great, even if they’re not made up of people in your city.

Given that the film has relatively low stakes—it’s not life or death, it’s house or no-house—what gave you confidence that audiences would connect to Jimmie’s story? I don’t know if we were ever confident. You never fully know. You hope that if you share something that has meaning to you then it will have meaning to others. That was our guiding light.

We finished the movie four days before the Sundance screening, so that was the first time watching it with any audience. I looked over at [Plan B producer] Jeremy Kleiner when the movie ended; he said “the tweets are good”. I looked around and realized the whole audience were on their phone as soon as the credits rolled.

I only had a short film play at Sundance before [American Paradise in 2017, also starring Jimmie Fails] so I didn’t realize part of our culture now is the need to immediately respond to something—but luckily they were nice. It will be much more anxiety-inducing going into my next feature now that I know how all this works.

We wanted to make something that captured the San Francisco that we grew up in and feel very strongly about. We’ve travelled to Chicago, DC, New York, LA, and Atlanta with the film and I was surprised to see how much people were connecting to it. In a way, Jimmie and I say it is unfortunately universal because it means the same things are happening everywhere.

This idea has lived with you and Jimmie for a long time. Can you talk us through the journey of the film? We’ve been informally talking about it for at least seven years and it’s gone through so many incarnations. We always envisioned it as the first feature that Jimmie and I would make after many years of making short films together. This story felt big enough in scope and there was a lot that we wanted to cover.

We wanted to tell a story about Jimmie and this Victorian home he once lived in and make it a valentine to the San Francisco we grew up in, that we see as being lost. We also wanted to celebrate all the wonderful people who are here that make this city what it is. That’s a big part of what we are afraid of losing: the very people that make San Francisco ‘San Francisco’.

An alternative poster for the film, illustrated by Akiko Stehrenberger.

We both lived with my parents for five years—we ran our operation out of the living room there. The first thing we did was shoot a concept trailer for Vimeo. It was a five-minute piece of Jimmie skating through the city telling his grandfather’s story, much like the [feature’s] opening sequence, though I filmed it hanging out of the side of my brother’s car.

Afterwards we got emails from people saying they wanted to help; they would become our core collaborators on the film. Khaliah Neal, Rob Richert, Luis Alfonso de la Parra, Natalie Teter, Sydney Lowe, Prentice Sanders, Fritzi Adelman, Laila Bahman and Ryan Doubiago. They spent years with us, hashing out the script over my parents’ kitchen table and working with us to create a look-book, run an ambitious Kickstarter campaign, write grant proposals and so on.

We felt like these oddballs—the last artists in San Francisco. You get a lot of noes along the way, having never made a movie before, so it was the emotional support that helped us persist through the difficult times. We were excited to be learning together, as a group of mostly first-timers, and were constantly making things.

Our look-book was very elaborate, thanks to our stills photographer Laila Bahman. We built it as a website and staged the scenes as if we were filming the movie, with costumes and heavy art direction. We knew people we pitched were probably seeing materials from other filmmakers who were further in their careers and probably better writers than us. We knew we needed to show the world of the movie so that executives’ imaginations wouldn’t be running off with thoughts of Michael B. Jordan or Donald Glover; that this is Jimmie and this is the plaid shirt we want him in and this is his Victorian. It’s his story.

That helped us get into the Screenwriter’s Lab at Sundance, but I didn’t get into the Director’s Lab, which I was initially bummed about because I really needed that experience. Our Kickstarter was very successful and those backers created a grassroots ground-swelling around the movie that pushed it forward, even though it was difficult in pitch meetings as we weren’t the most bankable pair in such a risk-averse industry.

In a last-ditch effort, my crew and I decided to do our own Director’s Lab instead. We felt if it doesn’t work now then that might be it for Last Black Man. I’d never made a proper short with a budget before but a producer named Tamir Muhammad, who had a short-lived venture within Time Warner called OneFifty, gave us the money to make what would become American Paradise. It gave the crew a chance to get in the trenches together before moving on to a feature, and show the potential of what we could do.

The team who’d assembled from our concept trailer years before all worked on American Paradise, from Khaliah Neal, Rob Richert and Luis Alfonso down the line. We worked with production designer Jona Tochet and even the sound team of Sage and Corinne (who would all go on to work on Last Black Man). In a city increasingly devoid of artists, we felt we’d found our people.

The short was different from Last Black Man, but features Jimmie playing the same character. After it played in Sundance it got the attention of Plan B’s Christina Oh. They took a big leap of faith on us, only having ever made that short. There’s not a lot of people willing to do that.

Khaliah, Christina and Jeremy approached A24 and we were in production two months later. From the outside it seems like this dream scenario of having the incredible indie studios Plan B and A24 behind us, but the truth is it took years working on drafts and wondering if anyone would ever read them. I think the extra time we had helped, because if we had the chance to make it two or three years ago, I don’t think we would have been ready.

Jimmie Fails and the creative team behind ‘The Last Black Man in San Francisco’ at the 2019 Sundance Film Festival. / Photo: Sue Peri

What was the first movie you made with Jimmie when you were teenagers? The first half-decent thing we made was a movie that my brother and I co-directed called Last Stop Livermore. I am actually in it alongside Jimmie and that was my first and only time in front of the camera. I learned my place pretty early on.

Didn’t you have a cameo in Last Black Man? I swear I saw you. I did have a cameo. As long as I’m not speaking, I’m okay. But even then when I just had to look at Jimmie once it was very difficult for me to do. I needed four takes for that shot, ha ha. I’m much more comfortable on the other side.

Jimmie, however, was really good in [Last Stop Livermore]. We made it while I was in high school before I dropped out, and it got into the San Francisco International Film Festival. Like everything we do, it’s based on something that happened in real life when a friend and I felt like we were fish out of water, going off to meet some girls in the suburbs.

That attention the film got, however minor, encouraged us because until that point only our family, friends and my high school teacher had seen our movies. Oh and Jimmie still had a flat-top—just thought I should add.

The film features the most important house of the year [Editor’s note: at least until the rest of the world sees the Parasite house, designed by the great Namgoong]. How did you find Jimmie’s house and what made it the house? It took us over a year and a half to find the house. We combed the streets with my co-producer Luis Alfonso de la Parra and production designer Jona Tochet and knocked on doors. In hindsight, a more efficient way would have been to use Google Maps but this way we could see inside the houses.

Unfortunately, the interiors would usually be gutted and have IKEA furniture and granite table tops. As a filmmaker, it was depressing, but as a native San Franciscan it was heartbreaking because the details inside all these beautiful houses were destroyed. It’s a thing that a lot of real estate agents do when they flip houses.

We ended up going back to a house that I had driven past as a kid on my way to elementary school. My mom, my brother and I would pick out our dream Victorian houses on our family car ride since we couldn't afford a proper one. I went back to one of the houses that had always stuck with me. After we found that house, it felt like we had cast a major character in the movie.

When we first knocked on the door of the house that would become Jimmie's home in the film, an older gentlemen greeted us and within seconds beckoned us inside. As we entered, we found a home that had not been gutted, but instead had been lovingly restored. Jim, the homeowner, much like Jimmie, the actor, had spent more than half of his life working on the house.

He carved the witch hat you see in the movie shingle by shingle and did the honor of putting it on the roof himself. He fixed the organs you see in the film and built Pope's hole in the library. In many ways, he felt like the spirit of San Francisco.

As a now elderly man, we would have understood him declining our wants to film there -- or charging a buttload to help him in his retirement. Instead he welcomed our big crew into his house and charged us next to nothing. I still don't fully know why, but I can imagine he saw shades of himself in Jimmie's love for this Victorian.

In the years we spent location scouting, we would also meet people on the street that we put in the movie. Dakecia Chappell was working at a Whole Foods in the confectionery section, near a ‘potential Jimmie’s house’ around the corner and she was just really charming, so I offered her the ‘Candy Lady’ part in the film. We met the mover who tells Jimmie the homeowners are moving out late one night at a taqueria on Mission Street. This extra time allowed us to capture the little details of what our San Francisco is like.

Even after your major backing from Plan B and A24, was there a point on set where it felt like everything was falling apart? I’m sure there are directors that aren’t plagued by the self-doubt I had. I didn’t go to film school and I felt isolated in San Francisco since a lot of the filmmakers have left for Los Angeles or New York. I was feeling this imposter syndrome. You’re both really joyous and grateful that you finally have a chance to make a movie, but also feel the weight of the city and wanting to honor what’s happening to people there. In every stage you have big and little freak-outs. The only thing that got me through it were the people around me. They bring perspective when you might not have it.

A couple of months before we shot the film my dad had a stroke. He survived, thankfully, and he would say half-jokingly “I survived to see the movie”. My parents struggled as artists themselves in their lives and yet they created this loving home that allowed us to make the movie. I look up to my Dad a lot, so when that happened that was really scary, and it happened during the height of the pandemonium of prep.

By that point our creative collaborators felt like family and they did everything for us. They came over to my house, brought us food, did as much as they could to take work off my plate so I could be with my own family. That always sticks with me when I remember tough times. You could say it’s just a job, but they treated it like so much more. So while it sounds corny, I think the spirit which comes with people being so loving and kind becomes imbued in the film.

Very glad to hear your dad is okay. The scenes with Jimmie’s parents are so powerful; you really get a greater sense of his isolation. It’s amazing his mom agreed to be in the film as a fictionalized version of herself. How did you and Jimmie sketch those scenes? The scene with his mom is loosely based on something that happened. Jimmie was raised mostly by his dad and he’s very close to his parents now in a way that’s very different from the relationship that he had with them growing up. He and his dad have worked through a lot.

Jimmie Fails as Jimmie. This and the header photo are by Laila Bahman.

It’s hard to pack in all the complex details that makes someone who they are because you don’t have enough screen time to do that sometimes. These elements were pulled from the walks we’d take during the earliest developments when the idea was more informal and we’d talk about Jimmie’s family.

One story that Jimmie always recalled both humorously but also quite painfully was about the guy who had driven off in the car that he and his dad were living in at the time. We thought it would be funny if there was a character who never acknowledged that he’d stolen the car but claimed that he was still borrowing it. We knew Mike Epps would be the perfect person for that. It was a story that came from a kernel of truth but took on a life of its own.

Why was Jimmie’s dad pirating The Patriot, of all movies? The tonal juxtaposition made us laugh. Ha ha, it was in the public domain.

We loved the score. What are some of the soundtracks that inspired you while making the film? The Last of the Mohicans, The Day of the Dolphin, The Claim, Batman (and also the animated TV show’s score actually rivals Elfman’s), and Far From the Madding Crowd.

You’ve spoken in another interview about how you and Jimmie fear friendships like yours aren’t possible with the type of gentrification that’s going on. However, nowadays you can meet some of the important people in your life over the internet. Could the bonds we make online compensate for what’s being lost on the streets? I think the internet is a double-edged sword. It both brings people together that you could never have met, such as how many of our closest collaborators first found our concept trailer online. But I do fear it also plays a part in people developing shallower, less intimate connections. I have friends who I love who will go to events seemingly just to get a good Instagram photo out of it. I’m sure I’ve suffered from similar instincts. That scares me.

Montgomery adds so much tenderness and insight to the film. Given he’s Jimmie’s best friend and he’s also an artist, is he your avatar in the movie? How did the casting of Jonathan Majors inform the development of his character? Montgomery is actually not based on me. Jimmie and I have a friend from the Bay named Prentice Sanders who is one of the more original people we’ve ever met. His spirit influenced the first shades of the character. When Jon came on he took those early sketchings to a whole new level, creating his own backstory, mannerisms, and interests.

On the vanity in his room, Jon decided to put up Tennessee Williams, August Wilson, Barbara Stanwyck, Canada Lee, Richard Wright and Ralph Ellison as inspiration. He had a hand in every little detail. In fact, Jon and Jimmie became very close in real life. They still talk nearly every day.

Warning: the last section of the interview contains spoilers, including for the endings of both ‘Last Black Man’ and ‘Ghost World’. This is your last chance to back out…

How do you direct Jimmie? I imagine you can read each other’s minds at this point. Yeah, there is a weird unspoken connection between us, as we grew up together. Knowing each other for so long allowed us to be vulnerable around each other. As a director, inevitably there are days on set that are stressful, scary, and tense, so being able to go for a walk around the block together to recalibrate and feel present was helpful.

This film asked something much different than anything we had done before. We’d never written a feature script and most of our shorts were ad-libbed. Honestly, everyone broke their backs to make this. Cinematographer Adam Newport-Berra was a hero. Nobody phoned it in.

But more than anybody, we asked the most of Jimmie. There’s a scene where he’s across from his real mother and the bravery from both of them to do that set a tone that everyone on set sought to honor.

Joe Talbot and Jimmie Fails on the set of ‘The Last Black Man in San Francisco’. Photo by the film’s cinematographer Adam Newport-Berra.

Your collaboration with Jimmie has been so strong for such a long time. Is it a relief for you or maybe a sadness that this phase with him is nearly over? It doesn’t feel like it’s over yet, but I’m sure when it does there will be a little bit of sadness. The movie continues to sell out theaters on a Wednesday afternoon in San Francisco and opened in the little neighborhood theaters that indies barely make it into and it's playing alongside Toy Story. There’s a feeling in the city now that’s hopeful.

It’s been wonderful to witness because I feel like we’ve been working through our feelings about San Francisco in making the movie, and in some ways Jimmie leaving at the end feels a bit like us, how perhaps we can’t be here anymore. I’ve only ever lived in San Francisco my entire life but maybe it is time to go somewhere else.

However, in putting the movie out there I’ve seen so many more natives that feel like people I grew up with 15-20 years ago. People who I thought had been lost but are still out there, fighting to exist somehow through all the changes. I feel like part of me is falling back in love with San Francisco again and I think that feeling is going to go on for a long time.

A lot of people are contacting us saying that they left the theater and they just started writing their own scripts, or writing poetry, or sending us paintings that were inspired by the movie. In a city that is increasingly difficult to exist in as an artist and not always inspiring, this always means something to us.

On the film’s ending: to you, where is Jimmie going? Jimmie is going to start his legacy somewhere else—to fully be himself and start anew, following the footsteps of his grandfather. And it’s more fun to shoot it that way than have him ride away on a BART train.

One interpretation of the ending we’ve heard is that it was all in Mont’s head, and in “reality” it ended on a more tragic note. So some viewers felt it as hopeless, but you in fact intended it to be more hopeful? I think we wanted to leave it open to interpretation. I talked to Thora Birch [who has a small role in Last Black Man] about the ending of Ghost World, because that always left an impression on me. I interpreted it as a suicide when I saw it as a teenager and she had told me that she felt that way about it too, but there are also people who thought she was going off to art school. I feel our ending works in the same way.

I don’t see any interpretation of it as invalid, but what your relationship is to your city affects what you bring to it. Either way it’s a bittersweet ending, because it is a loss for Jimmie and Mont’s friendship, and for the city. Like, San Francisco doesn’t deserve him anymore.

Discover the films that inspired the look and feel of ‘The Last Black Man in San Francisco’.

#the last black man in san francisco#joe talbot#jimmie fails#danny glover#san franciso bay#gentrification#sundance#sundance2019#letterboxd

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Unsung heroes

Words: Rebecca Thomson; Photo: Cate Gillon/Getty Images

There are over 100,000 war memorials in the UK, but only one has been dedicated to African and Caribbean soldiers. Unveiled on Windrush Square in Brixton in 2017, it was met with surprise by those it was designed to honour. Alan Wilmot, a WW2 veteran who served in the Royal Navy and lived in south London, told the BBC: “I did not dream I would be around to see things like this happening.”

For years, little has been done to make people aware of the crucial role played by these men and women. Many faced the same horrors of war as their white counterparts while also coping with institutional racism. There are few letters and diaries from these soldiers and the records of the British West Indies Regiment were apparently lost in a WW2 air raid.

From academic history to the entertainment and publishing industries, the stories told about the wars are missing a large part of the picture. Peckham historian and author Stephen Bourne, whose most recent book Black Poppies is about the wider contribution of black WW1 servicemen and women, says: “The subject has been ignored by historians and chroniclers for such as long time that there’s very sparse information.

“These soldiers also came from a generation that was seen and not heard - they weren’t encouraged to talk about their lives. It is only now, with the Windrush scandal, that people are becoming interested.”

The national narrative surrounding the ethnicity of British soldiers in WW1 and WW2 has been whitewashed. But without African and Caribbean soldiers, as well as the Indian army and other soldiers from across Asia, both wars could have ended differently.

Alan Wakefield, Head of First World War and Early Twentieth Century at the Imperial War Museum, says: “The numbers are significant. It would have been very difficult to win a number of the campaigns the British were fighting without these soldiers.” The museum is hosting an installation called the African Soldier by artist John Akomfrah until March 2019, but Wakefield says that even an institution like IWM, with access to resource and expertise, has found it hard to breathe life into the stories of black soldiers.

“Immediately after the first world war, the empire’s contribution and a lot of these stories got overlooked. Even our collections here - we’ve got some good materials, but we’re quite short of 3D objects, letters and diaries from black servicemen. There’s very little directly relating to the soldiers themselves.” There are hundreds of photographs, he adds, but relatively little to explore the stories of the people in them, because so little was saved.

It’s difficult to measure the number of African servicemen who served, but they were spread all over the world and around two million were thought to be involved during WW1 alone. Around 15,500 Caribbean troops volunteered in WW1, including 10,000 from Jamaica. In the second world war around 16,000 troops volunteered, with 6,000 serving in the RAF.

With so many stories lost, it is vital to remember those we do have. Sam King, who lived in Peckham until his death in 2016, served in the second world war as an engineer in the RAF. He returned to Britain in 1948 on the Empire Windrush - around a third of the boat’s original cohort were WW2 veterans.

He went on to raise a family in the borough, worked for the Post Office for 34 years, and became a community activist. He worked with Claudia Jones to set up the Notting Hill Carnival and was involved with Britain’s first black newspaper the West Indian Gazette. He campaigned on migrant welfare issues and in 1982 was elected as the first black mayor of Southwark, a role his granddaughter Dione McDonald, who lives in Herne Hill, said was among his proudest achievements.

“I would go to the market with my grandad, and the Cypriot shopkeepers would call him Mr Mayor years after he was. They said he was still their mayor. People called him that until the year he passed away and he still felt proud of it. For him it wasn’t just a superficial role, it was finding a way for everybody to have a voice, ensuring everyone was represented and their needs were being met.

“His story is unique - he came at a time when there was a real awakening of the British civil rights movement.”

King also set up the Windrush Foundation with Arthur Torrington in 1996, with the aim of fundraising and organising for the 50th anniversary of the Empire Windrush’s arrival. “We decided to set it up for the 50th anniversary,” Arthur Torrington says.

“And from then we have moved it to be a national thing.” He says the aim of the organisation now is to improve knowledge of and education around the Windrush and other migrant stories, particularly in schools. “Our goal is to have it taught in every school, helping youngsters to understand their ancestors.”

Caribbean stories have come to the fore recently, as the country celebrated the 70th anniversary of the Empire Windrush arriving at Tilbury docks. Many of the former servicemen and women who arrived on the boat settled in South London.

Post-WW2, they were joined by veterans from across the world. In 1948 the government passed the Commonwealth Act, giving people throughout the empire full British citizenship and the right to move to the UK. Veterans from India, European countries such as Poland, and African countries from Gambia to Ghana chose to make their home in the country they fought for.

It is difficult to gauge how many veterans made their way here, but it is safe to assume, given the millions of Indian, African and European people who served on Britain’s behalf, that they made up a significant number of the post-war population shift, and arrived not as immigrants, but as British citizens.

“Not only did they support the country in two world wars, they came back afterwards and helped to rebuild it,” Bourne says.

The post-war generation were not the first to arrive, however. Dr Harold Moody moved to London from Kingston, Jamaica in 1904 to study medicine at King’s College, but despite being fully qualified was denied a job at a hospital. He set up his own GP practice in King’s Grove, Peckham, moving to Queens Road a few years later and living there with his wife Olive and their six children.

Having suffered appalling racism during his career, Moody dedicated his free time to campaigning to make Britain a fairer place. Among other things, he fought for black servicemen to be able to rise above the rank of sergeant - one of his sons, Charles Arundel Moody, went on to become a colonel in WW2.

In 1931, Harold Moody formed the League of Coloured Peoples, which was created to campaign for economic, social and civil rights in Britain and beyond. The organisation's work was credited with laying the groundwork for the Race Relations Act of 1965, the first piece of legislation to outlaw discrimination ‘on the grounds of colour, race or ethnic or national origins.’

King and Moody were notable for their political achievements, but they were just two of many thousands of people whose contributions have been overlooked. “If politicians had been better informed about these subjects, maybe the situation would not have deteriorated as it has,” says Bourne.

Sam King’s granddaughter Dione McDonald says the focus should now be on education. “This is a part of history that you are not allowing the next generation to understand. All children need to understand why their city and country is the way it is. Ignorance is not fun, and it’s unfair if people are not given the option to deal with it. You deny people an understanding. We still have a long way to go.”

Just as the Windrush Foundation is campaigning to improve education around stories of migration, McDonald says the topic should not be optional for schools.

“The next generation are part of a global world, not a local one, and if you are going to talk about the topic you might as well talk about it properly. If you want a society that’s united and has a sense of community and responsibility you need to give them the information to begin to be accepting.”

Britain has lost heroes from its own story - by forgetting these people, we are erasing the bravery and civil rights work that helped to make the country what it is. It required an unusual dignity and drive to achieve so much in a country that ignored such contribution; throughout their lives, these veterans showed both.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

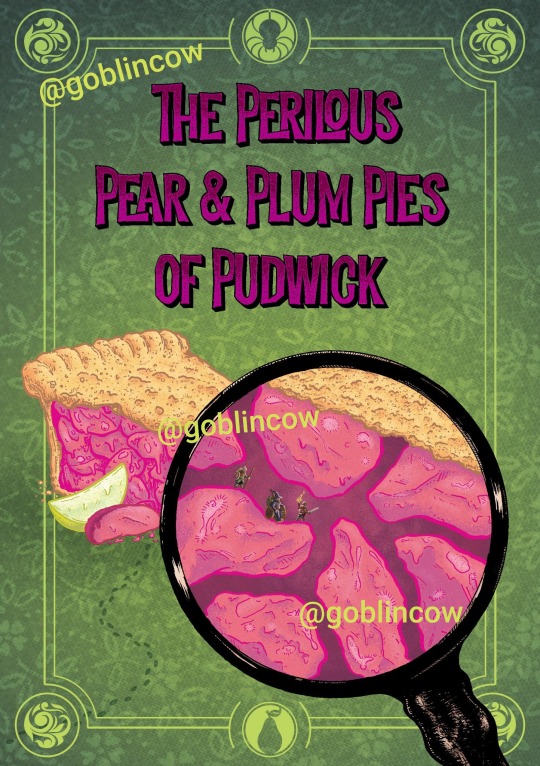

Thanks @theresattrpgforthat for the opportunity, glad to oblige!

The Perilous Pear & Plum Pies of Pudwick (TPPAPPOP) is a special upcoming full-colour issue of The Undercroft published by the Melsonian Arts Council compatible with all your favourite indie dungeon-crawlers!

Initially announced as The Undercroft #13, I've since moved house three times, gotten covid three times and had the equivalent of a part time job fighting with the Department for Work and Pensions for disability support for myself and my partner - so since it was first announced nearly three years ago progress has been stop and start!

However the end is in sight as I'm wrapping up the last of the illustrations, all hand drawn and digitally coloured in a limited palette like this one:

So what's the book about?!

Well, here's my working blurb!

A well-meaning outsider brings reckless colonial magic into a small community on the eve of the local bake off. Hijinks ensue as chitinous consequence follows behind on a thousand scuttling limbs.

Explore the dawn of a new insectoid world ripe for adventure! Shrink down to size and take your first furtive steps into a brand new world living inside a sapient pear tree filled to the brim with insect NPCs, communities & conflicts and their (relatively) ancient secrets.

Unravel the mystery at the heart of the tree, and make your (proportionately) tiny mark - will you do more harm than good in these dawning civilisations, and how will you ever decide the destiny of a world that was never yours to discover?

The first handful of pages invite players into the inciting chaos at the food festival, and the rest of the book is a hexflower labyrinth-crawl inside the tree. But the clock is ticking: you'd better get in and out before you rapidly grow back to regular size - an explosive & messy demise for you, the tree and the world inside!

Each hex contains an evocative location description and a d4 table of encounters or d3 table of vignettes that hold all manner of weird-fantasy wonders. There are various deeply interconnected factions active in the tree, from the empire of the ants contesting the ladybirds for control of the aphid farms, to the Pear Republic citizens who live under the grip of the infamous Stinking Bishop, to the ragtag group of outcast adventurers whose staging ground is a half-buried porcelain gnome.

Smart, easy to reference layout has been a really important pillar of my design process from the beginning - my very first draft actually directly copied the style of Old School Essentials adventures, but I've massively developed on the reading experience a lot since I began to hit the best of both worlds re: reading experience and table usability, with a rainbow of limited colour illustrations and a focus on short compelling prose with matching coloured/bolded key-words for easy reference throughout the book.

If you enjoyed the world of Hollow Knight and are very patiently waiting for Silksong (like me!), and if you enjoyed Bug Fables, Honey I Shrunk The Kid, or another big inspiration of mine - The Legend of Zelda: Minish Cap - then this is the book that's going to scratch those bug-lovin' itches just right! Keep an eye out for anything I tag with #TPPAPPOP on this closing stretch (just a couple of months left I think) to know when the book is finally available!

--------

If you want to know more, pick a page number from 3-51 (I made good use of the back inside cover with a loot table directly inspired by the fantastic I Search The Body table in the Mothership module Dead Planet) and I'll give a little excerpt!

This is without a doubt the best writing and illustration work I've ever done so I'd love an opportunity to share it - thanks to @rathayibacter for the idea!

The Perilous Pear & Plum Pies of Pudwick, pg. 36

release date: TBC

publisher: Melsonia (The Undercroft special full-colour 48 page fully-illustrated issue)

format: oldschool-style weird fantasy hexcrawl adventure compatible with all oldschool systems

genre: shrink to insectoid size and adventure into the uncanny world that exists inside a sapient, talking pear tree

this image is fresh from the exports folder - project links and full pitch to follow in future pinned posts

#TPPAPPOP#indie ttrpg#my art#the undercroft#melsonian arts council#hexcrawl#hexflower#illustration#little dudes#bugs#hollow knight#silksong#bug fables#inspiration#coming soon#dungeon crawler#d&d#rpg adventures

54 notes

·

View notes

Text

Gonzo the great

On a cold winter’s day in 1984, exiled by Hollywood and with his career seemingly kaput, Oliver Stone bought a cooked lamb and offered it up with fire, incense, and prayer in a ritual sacrifice on his front lawn, begging forgiveness from Pallas Athena, goddess of wisdom. “It was a strange and solitary ceremony, witnessed only by my two ravenous dogs,” Stone explains, adding that he let his hungry pets chow down when he was done. “After all, what did the Greeks do with all those fine oxen and sheep that were sacrificed on Homer’s pyres?”

That an Oscar-winning screenwriter might attempt to fix a career slump by freaking out his neighbors with a ritual sacrifice of store-bought lamb is the kind of colorful anecdote you could hear about any Hollywood flake. But the intense sincerity of the ceremony––the 100% irony-free belief that Pallas Athena would indeed be listening––well, that could only come from Oliver Stone, a larger-than-life character who sees himself as a figure of modern myth. He’s often ridiculous but not entirely wrong. Stone’s compulsively readable new memoir CHASING THE LIGHT chronicles the first half of his career with the kind of grand, go-for-broke immediacy that defined his early films. I couldn’t put it down.

It’s a life of such bold gestures the book could rightfully be written in all caps. Born to a wealthy stockbroker and his French war bride, William Oliver Stone dropped out of Yale to write the Great American Novel at the age of nineteen. When it was rejected by publishers, he hurled the manuscript into the East River and enlisted in the Army, requesting assignment to the Infantry to prove his mettle on the battlefield. Stone later shaped his wartime experiences into “Platoon,” the 1986 release of which to rapturous acclaim, boffo box office, and four Academy Awards serves as the ending of this book, the catharsis at the end of a long and tortured path home from Vietnam.

After returning from the war, Stone almost immediately landed in a Mexican jail for smuggling drugs, rescued only by his father’s connections while the rest around him were left to rot. He finally found his calling at NYU’s film school, where a fast-talking young instructor named Martin Scorsese greatly admired his student short, announcing to the class “This is a filmmaker, ”a benediction Stone still describes as “my diploma.” (The twitchy, anti-social vet was at the time driving a cab at night, inadvertently supplying some inspiration for his professor’s most iconic screen character.)

Most of “Chasing the Light” is devoted to Oliver’s early misadventures in Hollywood, rocketing to stardom at the age of 33 with his Oscar-winning screenplay for “Midnight Express,” then burning all his bridges on a quick trip back to relative obscurity. It’s a dishy, delicious read, telling tales out of school and at the expense of directors who had the temerity to change a word of the brilliant screenplays he’d provided them with. If ever there was a writer who needed to direct his own material, it’s Oliver Stone.

(In the great 2015 documentary “De Palma,” the “Scarface” director says he had to ban Stone from the set because he was overstepping his bounds by giving the actors line readings. Stone here diplomatically describes De Palma as “simply not the most energetic of human beings.” Sounds like it was a fun production.)

Curiously enough, one comes away with a sense that the character closest to Stone’s heart was Robert E. Howard’s Conan the Barbarian, whose adventures the screenwriter originally envisioned as a ten or twelve (!) film series. He includes generous excerpts from his original, admittedly un-filmable 140-page script, full of pig mutants, hydra heads, and gloriously purple prose. It’s no stretch to say that Stone sees much of himself in the lusty, literate pagan warrior, and this outsized self-image––which does much to explain his off-putting affinity for despots like Castro and Putin––is backed up in the book by grandiose allusions and constant quotations from Homer, Tennyson’s “Ulysses,” and of course, Jim Morrison. So much Morrison.

Stone’s career resurrection would arrive with the 1986 double-whammy of “Salvador” and “Platoon,” both backed by Hemdale’s John Daly, a beloved indie film buccaneer to whom “Chasing The Light” is dedicated. It’s with these pictures that Stone took the helm and perfected his blunt-force trauma, American tabloid-style of storytelling. Pauline Kael said “he writes and directs as if someone had put a gun to the back of his neck and yelled ‘Go!’ and didn’t take it away until he’d finished,” which is an apt description of the low-budget, guerrilla filmmaking productions chronicled herein. Stone rollickingly recounts the logistical nightmares overcome during these grueling location shoots, in the process finding at least a dozen different ways call his “Salvador” star James Woods a giant pussy.

In a candid autopsy of what went wrong with his screenplay for “Year of the Dragon,” Stone speculates that director Michael Cimino never fully recovered from the disastrous experience of “Heaven’s Gate,” insinuating that he understands this all too well. Likewise, I don’t feel like Stone ever really bounced back from the debacle of his 2004 “Alexander,” an obviously flawed yet deeply impassioned and fascinating picture that only Oliver Stone could have made. He’s directed some good films since then, but they’ve been uncharacteristically timid and visually tame, missing that edge of mania––the fire-in-the-belly so beautifully conjured by this memoir. Maybe it’s time for him to call again upon Pallas Athena, or was the writing of this book the real ritual?

-Sean Burns’ review of Oliver Stone’s Chasing the Light, North Shore Movies, Aug 16 2020 [x]

0 notes

Photo

I believe in video game stories I quite like experiencing a story through the format of a video game. I’d even go so far as to say that aside from reading, it’s probably my preferred method of digesting a narrative. (I’m not as big on TV or movies - shocking, I know!) I think a lot of this appreciation comes from the fact that as a long term PC gamer, I was exposed to many point ‘n click adventures at a young age. These were games that fancied themselves as controllable books, with “author” names frequently placed front and center on the box art. The Secret of Monkey Island was specifically a Ron Gilbert game, King’s Quest VI a Roberta Williams jam. And boy, did growing up with these games give me an appreciation for the excitement that interactive storytelling could generate. After my six-year-old self had successfully guided Alexander of Daventry through the catacombs on the Isle of the Sacred Mountain and defeated the minotaur keeping Lady Celeste hostage, I was a fan for life. (Note: Clicking that link and watching the whole scene might induce eye-rolling, since it seems dated in this day and age, but trust me, King’s Quest VI is still an awesome game.) But not everyone had the same experiences as I did growing up. For a prominent segment of the population, story in games doesn’t really matter, and it never did. In fact, it seems that every other month on NeoGAF, a new thread will pop up on video game stories, and inevitably it’ll spark a debate where a whole mess of posters echo things like “90% of all game stories suck” or “story in games doesn’t matter to me because if I want story I’ll watch a movie or read a book.” Then there are hot takes on the pitfalls of game storytelling by Twitter personalities and academics that occasionally appear in mainstream outlets like The Atlantic. Case in point - one that started a controversy last month with its clickbaity headline “Video Games Are Better Without Stories.” I rolled my eyes when I read The Atlantic article, mostly because it’s written by an academic who’s previously written stuff in a similar vein that I didn’t agree with, like “Video Games Are Better Without Characters.” The internet arguments that emerged surrounding his newest piece made me pay a little more attention this time, though. In a nutshell, Ian Bogost’s thesis is that the systems within a game should come first, and the ability of players to manipulate these systems to manufacture their own narratives is where the medium’s true strength lies. In other words, emergent gameplay trumps traditional storytelling.

This isn’t necessarily a bad point. After all, some of the most prominent and popular games in this day and age either keep plot in the background or totally ignore it in favor of focusing on mechanics that give power to the players, letting them create their own stories that stick out in their head more than any pre-engineered script could. Dark Souls does this well, with unforgiving combat and an atmosphere that makes everyone playing it feel like they’re stuck in their own personal hell. The newest Zelda game, Breath of the Wild, does it too, keeping story to a relative minimum and encouraging players to experiment with Link’s items and abilities instead. And then you have competitive games like League of Legends and Overwatch, which leave their story components out of the mix completely. But despite all of these titles not placing story as their biggest priority, it’s kinda obvious that large segments of their fandoms feel differently. Just type “Dark Souls story” into YouTube and you’re assaulted with a staggering number of videos, and the encyclopedia of fan-assembled lore on the Dark Souls Wiki page is a force to be reckoned with. Breath of the Wild has inspired spectacular discussion on where it falls in the wonderfully convoluted timeline established by Hyrule Historia. League of Legends has a whole website devoted to its lore, and Overwatch has comics and animated shorts that fans gobble up with frightening veracity, often while begging Blizzard to release some sort of campaign revealing more background behind the Omnic Crisis. If anything, this unquenchable thirst for lore shows that despite gameplay coming first when it comes to interactive entertainment, at the end of the day, human beings still love a solid story that contextualizes gameplay, and game designers who want to create big narrative-driven experiences shouldn’t cease their efforts. Emergent gameplay is great, but going by Ian Bogost’s suggestion that games should SOLELY focus on this assumes that 1) all players want the sort of system-heavy games that he prefers (SimCity, for example), and 2) that the “traditional” route of telling a story within a game can never compete with film and literature.

I find the argument that games can never move or shake you in the same way that movies and books do to be awfully defeatist. It’s also an unfair comparison, since games are a much younger medium that face the challenge of conveying a plot around characters that can be controlled. Books and movies don’t have to deal with this, and endlessly asking questions like “where’s the Citizen Kane of video games” is both using a (frightfully overrated) yardstick from one medium to unfairly judge the efforts of another, and ignoring the unique strength that games do bring to the table - the ability to generate investment and immersion by making the player feel like he or she is an integral participant in the plot rather than a mere observer.

The sensation of feeling like I was part of the action is what gripped me to King’s Quest VI as a child. It’s what grips me to the best story-driven games out there, the ones that realize that they have this strength and capitalize upon it. The potential that games have for immersion is unsurpassed, and while it’s true that the medium is capable of producing plenty of schlocky, C-grade plots, the same could easily be said of books or movies, especially when you consider all the young adult fiction and superhero films that pass for quality entertainment in this day and age. Those who think all video game stories are garbage are more often than not cutscene skippers who are simply too impatient to give games a chance, biased individuals who are too used to experiencing stories in more passive forms of media or quite simply people who need to play better games. Because once you start judging the medium on its own terms and take the time to do some digging, there are many fine stories to be found out there - The Witcher games (which are arguably a tad superior to the books that spawned them), Deus Ex, the Quest for Glory series, the Gabriel Knight games, the Monkey Islands, The Last Express, Planescape: Torment and even a little game from Taiwan named Detention which could have been an indie movie, but arguably was more effective in reaching a wider audience on Steam.

Games don’t necessarily need to bring narrative to the forefront, as successes like Overwatch prove. But I’m glad that certain titles and developers do seek to accomplish this goal, because there are fans out there who believe in interactive stories and want to see this medium continue conveying bigger and better tales. I’m one of them, and I won’t stop being one of them. I’m a product of Alexander of Daventry, Geralt of Rivea, Guybrush Threepwood and all the other great characters inhabiting high quality video game narratives, and their stories are going to stick with me as long as I live..no matter what opinions pretentious contrarians publish on the internet.

Header image of Geralt with a book is from a larger wallpaper available on CD Projekt Red’s website. You can see the big version here.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Indie Vs. ...Not