#battle of mosul

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Iraqi SOF inside a bombed-out building in Mosul, 2017

103 notes

·

View notes

Text

An Iraqi soldier wears a gas mask amid reports of ISIL forces using chemical weapons to slow the advance on Western Mosul. April 16, 2017.

(Photo credit: Ahmad Al-Rubaye)

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

3/26/25

Haviv Rettig Gur on deaths in Gaza:

The full list of Gazans killed in the war has been released in Gaza. Possibly. At the very least, as Israeli analysts are now finding, there aren't duplicate ID numbers or other tells one finds in obviously manipulated data sets. But here's another reason to trust the data: It shows just how much Israel's warfighting tried to separate combatant from civilian. It seems unlikely that a faked Gazan data set would show such a result. The graph in the first tweet of this thread shows male to female deaths. If female deaths are assumed to be a civilian baseline (the age distribution is roughly the general Gazan population's age distribution), then the enormous spike of the blue line, right in the area of the graph that represents fighting-age men, is the best likely measure of combatant deaths. According to this analyst, the gap comes to over 16,000 dead, or almost exactly a third of total deaths. That's a Gazan data set, not an Israeli one. And it's the most complete one so far, the only one that claims to give all the names of all the dead, the one most likely to be an honest recording of the actual dead. And according to this data set, the death toll in Gaza is two civilians to each combatant, well in line with the highest standards of modern democratic armies. To be clear - this caveat is obvious, but it's important enough to say it explicitly nonetheless - the debate isn't over whether children died in Gaza or crimes were committed. The answer to both is yes. There were definitely and unquestionably war crimes committed in Gaza, air strikes that should not have been carried out. And there are thousands of dead children in this data set. The debate is over the extent, whether these are at a level consistent with the inevitable costs of even the most legitimate kind of war, which will always be horrible, or whether the best data we have shows wanton Israeli killing and disregard for moral rules and international laws. Israel's haters will tweet pictures of dead children in response. If they did that for every war, I'd take them seriously and sympathetically. But the vast majority of them don't. They don't care about dead children, only about destroying Israel. And so they can't actually tell us anything about whether our army, broadly speaking, has fought morally. But this data set can. All war is evil, all war is hell, all war is a kind of civilizational failure. But war is sometimes nevertheless legitimate and inevitable. International humanitarian law came about not to end war, because ending war is impossible, but to mitigate its evils. If this data set is correct - again, a data set released from Gaza and not at all intended to validate any Israeli argument about its battlefield standards - then the costs imposed on Gaza by Israeli warfighting methods are consistent with what is generally considered in the West to be moral and legitimate. It is a comparable ratio to the 2016 Battle of Mosul in which Iraq, the Kurds and America drove ISIS out of the city. War is bad. I respect people who vehemently oppose this one, who question the Israeli political leadership's decisions, who use the war to debate the larger question of Palestinian independence and statehood. These are all legitimate responses to the suffering of Gazans. As is the argument I personally agree with that this war was the only path available to us to rid ourselves and Gaza of the neverending and endlessly destructive scourge of Hamas. But it nevertheless matters - indeed, it may be the most important thing over the long term - that this war's civilian casualties were not worse than other comparable wars, and that even Gazan data sets show that to be the case.

The thread to which Haviv refers is here

387 notes

·

View notes

Text

Claims that Israel has been committing a genocide of Palestinians date to long before October 7. Yet the population of Gaza was estimated to be less than 400,000 when Israel captured the territory from Egypt in a war against multiple Arab countries in 1967. It’s now estimated at just over 2 million. Population growth of almost 600% would make it the most inept genocide in the history of the world.

Those repeating the word genocide over and over, turning it into a mantra that penetrates the public consciousness, smearing Israel and anyone who supports it, ignore the facts of this war. This is not an unprovoked war, like Russia’s against Ukraine. It’s not a civil war between rival militias, like the one raging in Sudan — which, by the way, is being ignored by almost everyone, even though the UN describes it as one of the “worst humanitarian crises in recent memory,” where a famine could kill 500,000 people. No, Israel was attacked. On October 7, Hamas launched a gruesome assault on Israeli civilians, killing some 1,200 — including many women and children — and dragging hundreds of them as hostages into Gaza. Today dozens — including many women and children — remain in captivity. Those who keep saying that Israel’s response is an act of revenge rather than the strategic, defensive war that most Israelis view as a fight for national survival against a determined enemy backed by a powerful country are deliberately distorting reality. In doing so, they are perversely evoking the same false blood lust and grotesqueness embedded in the blood libel archetype.

Indeed, Hamas’ actions, which precipitated this war, don’t seem to exist in the minds of ostensibly humanitarian-minded protesters. Nor even the fate of the hostages, still captive in Hamas tunnels. Although the campus protests vary in their message and actions from school to school, we never hear protesters chant that Hamas should release the hostages or accept a ceasefire. Quite the contrary. Accusations against Israel at times include praise for Hamas, one of whose aims — the end of the Jewish state — is shared by some key organizers of the student protests. As Secretary of State Antony Blinken recently said, “It remains astounding to me that the world is almost deafeningly silent when it comes to Hamas.” Accusing Israel of genocide and putting the entire onus for stopping the war, putting all the blame for the deaths, on the Jewish state is even more astounding because Hamas — designated a terrorist organization by the US, the European Union and many other countries — is a group whose explicit goal, according to its founding charter, is not just to destroy Israel, but to kill Jews. That is the definition of genocide.

Still, the death toll, even by the Hamas count, does not in any way suggest a genocidal campaign. The terror organization puts the total at about 35,000. The figure, disputed by The Washington Institute for Near East Policy among other think tanks and researchers, includes Hamas fighters. That means the number of civilians killed, whatever the total, is actually lower. Compare that to the death toll in Mosul, Iraq, where coalition forces uprooted ISIS from a city that had some 600,000 people at the time. Estimates of the exact number of deaths vary, ranging from 9,000 to 40,000 (the latter is the estimate of Kurdish intelligence). The lowest figure is on par with the rate of total deaths reported by Hamas authorities in Gaza that does not distinguish civilians from Hamas fighters, while the highest is four times greater. I don’t recall hearing the term genocide used there, or in any of the battles that led to more than half a million people being killed in Afghanistan and Iraq during America’s wars there. And yet, Israel has been repeatedly smeared with this damning accusation.

150 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Most muwahhideen suffer from spiritual and psychological illnesses such as depression and others. This is not due to weak eeman but because there is a satanic war being waged against believers. We are in a battle against shayateen.

This war has been used even against your brothers in the battles of Mosul and the Wilayah of Khayr in Hajin, where a brother during combat would be afflicted by possession, and so would their families. Therefore, do not neglect your adhkaar and protect yourselves as much as you can. We ask Allah to safeguard you from the shayateen of humans and jinn.”

-copied.

“Indeed, Shaytan is an enemy to you; so take him as an enemy.” Allah Himself tells us to beware from the evil of Iblis and his offspring, yet we are heedless in seeking Allah’s protection.

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

—

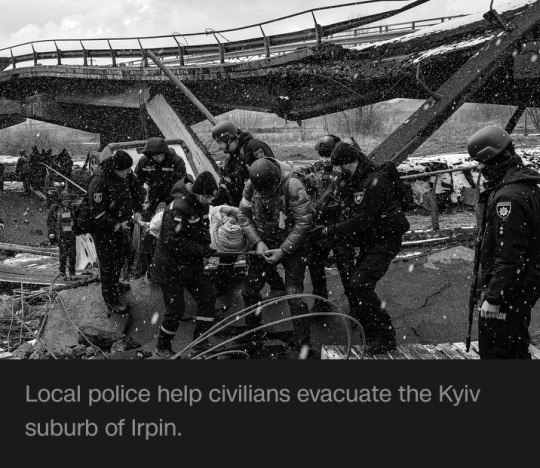

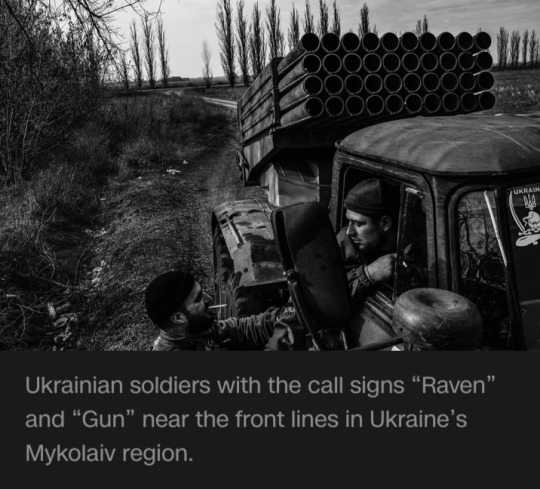

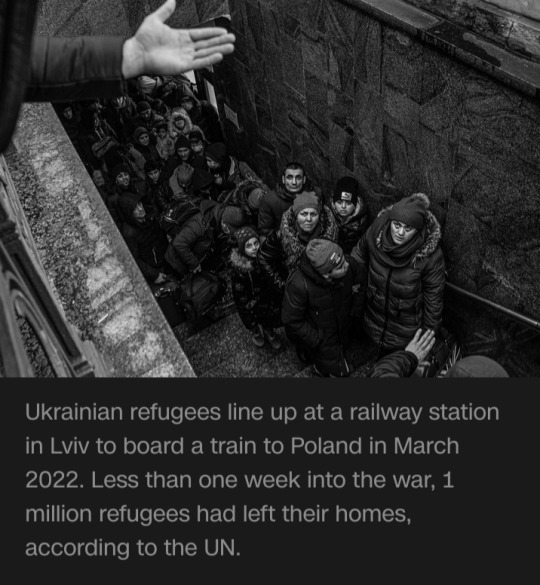

In Byron Smith’s new photography book, Ukrainians are pictured fleeing by any means possible — crammed into cars with pet dogs, waiting to board trains to Poland, or simply taking to suburban streets with infants and backpacks in hand.

As a photojournalist whose work often focuses on the plight of migrants (a mission that has taken him from Greek refugee camps to the battle for ISIS-controlled Mosul, Iraq, in 2016 and 2017), his instinct was quite the opposite: to run toward the danger.

“I feel like if you see these masses of people fleeing, it would be fake for me to really sympathize with them if I didn't go and see what they were fleeing from,” Smith told CNN in a video interview from Istanbul, Turkey.

Documenting Smith’s travels through Ukraine in the year following Russia’s unprovoked invasion in February 2022, “Testament ‘22 – A Visual Road Diary Through a War Zone” is a contemplative portrait of a nation at war.

The 192-page tome juxtaposes color with monochrome, defiance with despair, hope with fear.

—

The title references “My Testament,” an 1845 poem by Taras Shevchenko in which the author asks to be buried among the fields, rivers and steppes of his “beloved Ukraine.”

The photographer recalled reading it as he first ventured to Kyiv.

“It's pretty much (Shevchenko’s) last will and testament... And I'm riding into this war zone, the Russians are invading and I’m like, ‘Wow, I actually don't have a will and testament for myself, for my parents or family, or even anything to really leave behind for anybody.’

That played on me a bit, and it became the backbone for the story.”

The book serves, too, as a testament to the people of Ukraine, whose stories Smith felt compelled to share with the world.

Its publisher, Verlag Kettler, believes the photographer’s body of work can contribute to the “overwhelming evidence” of Russian crimes.

xxx

#Ukraine#Byron Smith#war#refugees#victims#photography book#Testament ‘22#Testament ‘22 – A Visual Road Diary Through a War Zone#war zone#Ukrainians#photojournalist#photojournalism#My Testament#Taras Shevchenko#Kyiv#Verlag Kettler#testament#war crimes

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

by Jake Wallis Simons

The Gray Lady even contrasted the two incidents in a way that painted the American atrocity favourably while casting Israeli intentions in doubt. The Kabul attack, it said, ‘came after a suicide bombing killed at least 182 people, including 13 American troops, during the frantic American withdrawal from the country. Under acute pressure to avert another attack, the US military believed it was tracking a terrorist who might imminently detonate another bomb. Instead, it killed an Afghan aid worker and nine members of his family.’

The Gaza strike, however, ‘adds fuel to accusations that Israel has bombed indiscriminately’, the New York Times said, pre-empting the results of the independent investigation with breathless speculation and a healthy dose of ‘confirmation bias’ of its own. The assumption could not be clearer: whereas the Americans were acting out of panic and confusion, the Israelis were either acting out of disregard for human life or straightforward bloodlust.

Civilian deaths, including those of aid workers, are a tragic reality of modern warfare. Sixty-two humanitarian workers lost their lives in combat zones last year. Although they were mostly killed at the hands of autocratic regimes and militias, during wartime they are also the casualties of democracies, including Britain.

During the Libyan civil war in 2011, when David Cameron had his hands on the joystick, 13 people were killed by a NATO airstrike, including an ambulance driver, three nurses and some friendly troops. (He did not, surprisingly, subject his own government to the type of rhetoric that he has recently been levelling at the Israelis over the mistaken Gaza strike.) That same week, NATO wiped out a family near Ajdabiya in the north of the country. This year, even the Danish military was forced to admit that its aerial assault had claimed the lives of 14 Libyan civilians.

The difference between attitudes towards most Western armed forces and the Israelis could not be sharper. According to the UN, the average combatant-to-civilian death ratio in war around the world is one to nine. When Britain, America and our allies battled Islamic State in Mosul in 2016-17, we achieved a much more respectable rate of about one to 2.5. In Gaza, Israel has done better still, reaching about one to 1.5, and possibly even less.

#double standards#civilian casualties#media bias#new york times#israel#gaza#hamas#humanitarian workers#civilian deaths#afghanistan

80 notes

·

View notes

Text

Iraqi Santa Claus next to an Iraqi Army tank clearing buildings in the city of Mosul during Christmas holidays, 2016.

160 notes

·

View notes

Text

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu warned of a “long war” in a recorded address on Tuesday as the country’s warplanes continued to pound the densely populated Gaza Strip. In the three weeks since Hamas’s rampage left more than 1,400 Israelis dead, the country’s top officials have maintained their intent to wipe Hamas “off the face of the earth.”

After 16 years in power, Hamas is deeply entrenched in the Gaza Strip. Regional experts have questioned Israel’s ability to dislodge the militant group in its entirety. Even if Israel were to succeed in toppling Hamas, it would leave a governance and political vacuum in its wake and a humanitarian crisis of unthinkable proportions. Already, more than 9,000 people have been killed in Gaza, according to the local health ministry, which is run by Hamas, but whose numbers have been historically reliable. Among the dead are more than 3,500 children, according to the United Nations.

But what comes after the war? Israeli officials have said little about their plans for the enclave and its 2.1 million residents. In this regard, they have evoked comparisons to the way that the United States went into Iraq and Afghanistan.

Foreign Policy spoke to almost a dozen current and former U.S. and Israeli diplomats and intelligence officials, Palestinian scholars, and regional experts about the future of Gaza. All expressed deep uncertainty, but through political, security, and diplomatic roadblocks, a set of grim scenarios begins to emerge, almost by a process of elimination.

“There’s no fantastic options here. You’re in the zone of what I would call, to put it gently, suboptimal options,” said David Makovsky, who was a senior advisor to the special envoy for Israeli-Palestinian negotiations at the U.S. State Department.

Can Israel Actually Destroy Hamas?

Projections for what is to come in Gaza start bleakly and get worse from there. A ground invasion of the enclave, a thicket of densely packed high-rise buildings, has been compared to the battle against the Islamic State in Mosul, Iraq, in 2016, which saw some of the world’s most punishing urban warfare since World War II.

Except in Gaza, it could be worse. Hamas has had years to entrench its positions in hundreds of miles of tunnels buried underground. The militant group has been known to stake out positions next to schools, hospitals, and mosques, further complicating matters for Israeli targeting. Already, the ferocity of Israel’s bombing campaign has exceeded the most intense rounds of airstrikes used in the U.S.-led coalition battle for Mosul.

“Almost by definition, the Israeli military objective can only be achieved by leveling significant parts of Gaza,” said Frank Lowenstein, a former special envoy for Israeli-Palestinian negotiations for the U.S. State Department.

The Israel Defense Forces (IDF) have repeatedly called on 1 million people to evacuate from Northern Gaza, warning that any who stay will be regarded as an “accomplice” of Hamas. Some 350,000 civilians remain, according to Israeli estimates. Some are too old or sick to be moved; others fear that they will never be allowed to return. Those who have fled to the south have still come under bombardment as Israeli airstrikes have struck throughout the Gaza Strip.

Israeli officials have set a goal of stamping out every last trace of Hamas, “not just decapitating Hamas tactically, but also crushing its ability to have any military or jurisdictional ruling capabilities in Gaza” irrespective of whether they are part of the group’s military wing, said a senior Israeli diplomat who spoke on the condition of anonymity but was not authorized to speak on the record due to Ministry of Foreign Affairs protocol. “There is no differentiation. If they are Hamas, they are Hamas,” the diplomat said.

Beyond the challenging military terrain, experts have questioned whether Israel can even eradicate Hamas in its entirety. In addition to the group’s military wing, tens of thousands of Hamas and some Palestinian Authority bureaucrats run schools, hospitals, and an ad hoc judicial system.

“We’re now talking about some 60,000 people,” said Khalil Shikaki, the director of the Palestinian Center for Policy and Survey Research. “They are running classes and schools, [and they are] doctors and nurses and people working in social services, people providing water and electricity. Why would Israel go after these people?” Shikaki said.

And then there is the challenge of Hamas as an idea. Founded in the late 1980s with a commitment to armed resistance and the annihilation of Israel, Hamas is the second-largest entity in Palestinian politics. “It’s an organizational embodiment of an idea,” said Aaron David Miller, a former senior U.S. State Department official who worked on Middle East peace negotiations.

As the death toll rises and humanitarian suffering in Gaza compounds, there is a significant chance that Israel’s pursuit of security now could sow the seeds of future insecurity. “I can’t even begin to wrap my brain around the long-term humanitarian and even security implications,” said Khaled Elgindy, the director the Middle East Institute’s program on Palestine and Palestinian-Israeli affairs.

“In the same way that Israelis have this desire for revenge, we can assume that that same human impulse is going to be present on a much more massive scale among Palestinians,” he said.

The Challenge of Reconstruction

While right-wing Israeli lawmakers have floated the idea of annexing parts of the strip, where Israel dismantled its settlements in 2005, senior officials have repeatedly indicated that they have no desire to reoccupy Gaza in the wake of the war.

It’s difficult to envision a day-after scenario in which the IDF doesn’t maintain at least a short-term presence on the ground to prevent any last vestiges of Hamas from reconstituting, as well as to stabilize the immediate situation. Israeli military leaders are already laying the groundwork for an interim scenario in which they oversee security and civilian life in the strip and are already looking at transferring personnel from the Coordinator of Government Activities in the Territories, a military unit that deals with civilian issues in the West Bank, to temporary roles in Gaza, according to a report in the Israeli newspaper Haaretz.

In the immediate aftermath of an Israeli military operation, humanitarian and reconstruction needs will be gargantuan. Hospitals and mortuaries are already overwhelmed. Supplies of fuel, needed to run hospital generators and water sanitation plants, are already dwindling after three weeks of Israel’s siege.

In the slightly longer term, experts point to a possible coalition of Arab states—potentially signatories of the Abraham Accords, which Israel feels it can work with—that could serve as an interim force to fill the security and governance vacuum in Gaza with support from the United States, the European Union, and the United Nations.

“I can see Egyptian, Jordanian, and Saudi soldiers with the international community controlling the region during an interim stage, and a huge amount of money that will come from the [United Arab] Emirates and the Saudis in order to reconstruct,” said Ami Ayalon, the former chief of Israeli domestic intelligence agency Shin Bet. But the longer and bloodier that Israel’s campaign in Gaza is, the more challenging it will become to secure the cooperation of Arab states.

Then there is the monumental challenge of reconstruction, the cost of which will likely run into the billions of dollars. Amid periodic outbreaks of hostilities between Israel and Hamas over the past decade, Gaza has been in a near constant state of reconstruction. Efforts to rebuild homes and infrastructure destroyed by war have been hamstrung by unfulfilled donor pledges and complicated screening mechanisms put in place to prevent construction materials from falling into the hands of Hamas.

“Reconstruction is crucial,” said Makovsky, the former U.S. State Department advisor. “You need to produce at least the potential of progress quickly.”

Politics After Hamas

The further out that one looks, the murkier Gaza’s future becomes. If Hamas is removed after running the Gaza Strip since 2007, the most obvious candidate to fill the void would be the Palestinian Authority (PA), which runs the West Bank. The Palestinian Authority was created in the wake of the Oslo peace process in the mid-1990s, with the hopes of laying the groundwork for a future Palestinian state.

But this is not a great best-case scenario.

First, there are the optics. The PA was ousted from Gaza by Hamas in 2007 and is unlikely to embrace the idea of returning in the wake of a punishing Israeli military campaign to unseat its rival. “They don’t want to be viewed as coming in on an Israeli tank and taking over the Gaza Strip,” said Zaha Hassan, a fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, whose research focuses on Palestine-Israel peace.

And then there is the question of legitimacy. The PA hasn’t held a presidential election since 2005, when the now 87-year-old Mahmoud Abbas was first elected. An overwhelming majority of Palestinians see the PA as corrupt and inefficient, while its security cooperation with Israel in the West Bank is regarded with deep suspicion as Israeli settlers have continued to chip away at Palestinian lands.

Next comes the capacity issue. The PA has struggled to protect civilians from attacks by Israeli settlers in the West Bank, and its budgets have been stretched to breaking point as Israel has withheld millions of dollars in tax revenues gathered from Palestinians.

The very survival of the PA has come into question in recent years, let alone its ability to take 2 million Gazans under its wing in the wake of a war. For the Palestinian government to have any authority, it would take new elections, significant resources, and “a very different attitude from the Israelis,” said Lowenstein, the former U.S. special envoy. “But we’re at the other end of the spectrum on all of those issues right now,” he noted.

The last Palestinian parliamentary elections in 2006 yielded a shock victory in Gaza for Hamas, which has long sought the destruction of Israel, as a protest vote against perceived corruption in Fatah, the main party in the West Bank. New elections for the Palestinian Authority could include commitments to nonviolence as a means to prevent the election of extremist groups, Lowenstein said. But democratic elections are inherently unpredictable and could require Israel and its partners to respect results that they do not necessarily like.

“Politics is not something that you can engineer from the outside,” said Elgindy of the Middle East Institute.

While an Israeli ground invasion is likely to deal a devastating blow to Hamas’s commanders, its foot soldiers, and its arms caches, many analysts noted that the only long-term solution to address Israel’s need for security and Palestinian’s hopes for self-determination is to work toward a political solution to the conflict.

Speaking to reporters last week, U.S. President Joe Biden reiterated his support for a peace deal and the creation of a Palestinian state. Before the Hamas attacks of Oct. 7, hopes for such a deal had long since slid into the rearview mirror. Support for a two-state solution among Israelis and Palestinians has also declined precipitously in recent years, but many still see it as the only viable way to resolve the conflict.

“If we want to see the state of Israel safe and without losing our identity as a Jewish democracy, this is the only concept. Because otherwise we shall create an apartheid state, and we shall never be secure,” said Ayalon, the former Shin Bet director.

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

if i had the time to make the perfect Vaguely Orientalist Documentary parody, it would look something like this: we open on lush views of the australian outback. playing in the background is some bollywood music. some educated white man is narrating about how the arabs, who worship but one god - zeus - are disorganised and backwards, and conclude with the valiant duel between the handsome and charming bohemond of taranto and the less handsome and less charming kerbogha of mosul. lots of half-naked shots of oily men wrestling. then we will move on to the second crusade. this time, we will open on the american prairie land. the narrator informs the viewer that much has changed from the first crusade (whilst egyptian music plays in the background): the arabs now worship odin and richard the lionheart has come to invade. this continues on for each crusade, and after the third crusade every muslim is simply called saladin, regardless of their actual name, with the music, visuals, and general historical accuracy getting further and further away from any kind of sense. by the seventh crusade elizabeth i will be leading the crusade against saladin against a backdrop of norway in winter whilst greensleeves plays. thomas asbridge will be weeping in a corner. white documentary makers will look on in horror. and somewhere in the middle east or possibly not, saladin will awaken for the final battle...

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

#Mosul (2019), a #war #action #movie on #Netflix, is based on the 2016 #BattleOfMosul, #Iraq, which saw the Iraqi Gov't. forces and coalition allies defeat #ISIS who had controlled the city since June 2014. The #US supported 277 days of #UrbanWarfare in Mosul. It's also based on true events chronicled in The New Yorker article: The Desperate Battle to Destroy ISIS

instagram

0 notes

Text

New Akkadian Lore Yushamin Ep. 8

SABBI SPECIALTY RECORDS

باسم الحياة العظيمة، عندما نجتمع معًا

Yushamin Aleph, Be, Gim, Xelq

Size: [REDACTED BY SABBI]

Power Output: [REDACTED BY SABBI]

Pilots: 1 active pilot, [REDACTED BY SABBI]

Weaponry and abilities: Highly mobile ground movement, modular weaponry and armor. Strength heavily dictated by [REDACTED BY SABBI]

Etc.: The system by which the Yushamin can be assigned to pilots may be confusing to some, please study and refer to appendix [REDACTED BY SABBI] for the ideal methodology. UNDER NO CIRCUMSTANCES ARE THE YUSHAMIN TO BE ALLOWED MORE THAN NECESSARY EXPOSURE TO UTHRA BODIES. EXTREME MEASURES MUST BE TAKEN TO PREVENT PROLONGED EXPOSURE.

Emergency claxons blare loudly as Waheeda and Syreeta climb into Yushamin Units Aleph and Beh. Waheeda, clad in her skintight, bladed pilot suit, slices her way through the thin membrane on top of Aleph’s head and slides into the warm fluid inside the machine’s cockpit. She closes her eyes, and does her best to begin her meditation and enter into a state where she can see through the statue’s eyes as her own. It takes a few seconds, but she gets there. With every mission, it gets slightly easier.

“Unit Aleph, are you ready?”

“Roger, command.”

“Unit Beh, are you ready?”

“Yes.”

“The mission will begin as planned. Step into the launch zones.”

The two Yushamin stand with their backs to the wall of the hangar, when a series of clamps reach out and grab on the statues’ arms, legs, and wings. With explosive force, they are sent upwards to the surface, and further up into the sky and into the waiting grasp of a SABBI airship’s hanging cables.

“SABBI Command Airship Miriai, report.”

“Miriai here, we have the packages. On route to the battle zone.”

“Alepha and Beh, Miriai is in charge of this mission, treat their orders like our own. Over and out.”

The Miriai flies underneath Al’Ahdath Mosul, and swings into a north-eastern trajectory, sending the Yushamin through the tops of some pine-like trees. Obviously, there is no damage, but Aleph (with Waheeda’s mind) is still a bit annoyed. Hey, watch the merchandise.

After a short flight, they come upon the target, a massive feline-like beast. “We’ve identified this as an Uthra, as you’ve been briefed. The weakness appears to be on the back of the skull, so we’re dropping both of you directly on it. We’re dropping on the count of 3, Hayyi Rabbi guide you. 1, 2, 3!”

The clamps holding the Yushamin split open, and the two are within freefall. Beh calls out to Aleph as it pulls out its knife, “I’ll land on the back and go for the neck. You land in front and distract it.” Aleph calls back out in the affirmative, and twists its massive body to change its trajectory.

With a massive crash, the trees that Aleph lands on in front of the Uthra crumple into splinters. The beast reels back in shock, before letting out a splitting roar and raising its cockles. It is at this point that Aleph deeply regrets their choice of being the bait.

Yushamin are large, but this monstrosity was on a different level. Aleph stares down the beast, throwing its melee weapon from hand to hand, before the creature raises its cackles and unleashes a horrifying, disgusting roar. Aleph can only instinctively flinch, and collapse under the creature’s massive weight as it leaps forward and holds the living statue under its forelegs, mauling it with its forearms.

“Beh! Having a bit of a problem here!” Aleph exclaims as it struggles to protect its body from the claws. “I wasn’t expecting it to jump!”

“I understand,” Beh says in a monotone as it leaps onto the creature’s back and crawls along its spine. It bares its knife, and jams it into the back of the creature’s neck, doing little to slow its massive claws digging into Aleph’s armor.

“Hurry up and dig it out, already!” “I understand.”

Beh carves at the neck until it finds its core, a smooth, spherical stone connected to the beast’s body by a number of tendrils. Beh methodically cuts each tendril one by one as per usual, until it stops for some reason. “Yo, Beh, you good? Syreeta?”

The Beh’s claws dig into the stone, and begin scratching at it, as if trying to split it open. Scratch, tear, rip, until the core somehow split cleanly in half, revealing its inside, a geode crystal display of bright amethyst and emerald-like crystals. For a split second, Beh says, “It’s beau-” before the crystals erupt out of the core in a single massive spike, and puncture deep into the Yushamin’s chest.

Aleph and Waheeda watched, first with confusion and then with fear, as Beh’s mouth opened up. Not that mouth, not the humanoid one. The bottom of its chin separates and splits the Yushamin’s skull like a crocodile’s, revealing two long lines of sharp teeth. Two gems on the side of Beh’s head spin around to reveal their pupils, which focus on the core in front of them. Its jaw opens wide, and it bites into the core.

Aleph screams over the comms. “SYREETA! WHAT THE-”

The Miriai interrupts. “THE HELL?!”

Beh rips the core off of the crystal, and swallows it in one bite. Its true eyes manic, green and purple drool dripping out of its skill, the Yushamin digs into the monster’s dead body with a voracious hunger unseen by living creatures. “SYREETA, STOP! I’M STILL STUCK UNDER THIS THING! WHAT ARE YOU DOING?!”

But it still tears chunks of the Uthra and shoves them into its mouth, until in its hunger it bites on one of its hands before it leaves its mouth. It pauses momentarily as it pulls away its severed wrist, but with a renewed vigor, it eats the rest of that arm, and then the other one, too. The Miriai chimes in over comms.

“Aleph! We’re coming to get you, grab onto the clamp!”

“But what about Syreeta?!”

“Leave it! The Yushamin’s chargon levels are off the hook, Syreeta’s almost certainly died of old age!”

Waheeda can hardly believe what she’s hearing, so badly that she momentarily disconnects from the consciousness of Aleph. Knowing, however, that that’s a death sentence, she tries her damndest to reconnect fast enough to grab onto the Miriai’s clamp before losing control again. From inside the Yushamin’s skull, she can feel the entire statue jostle and rise, and she takes the opportunity to crawl out the top.

As the airship flies away, she looks down at the Beh bleeding out on the monster’s corpse. She didn’t even know that Yushamin had blood.

—

1 WEEK LATER

Rami and Syreeta walked into the briefing room, him taking his usual spot at the lectern, while Syreeta sat down next to Waheeda. Tears filled Waheeda’s eyes as her arms began to tremble.

Art by @nebularobo

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Drone Wars: Pioneers, Killing Machines, Artificial Intelligence, and the Battle for the Future

click the book cover to download free

Drones are transforming warfare through the use of artificial intelligence, drone swarms, and surveillance—leading to competition between the US, China, Israel, and Iran. Who will be the next drone superpower? In the battle for the streets of Mosul in Iraq, drones in the hands of ISIS terrorists made life hell for the Iraq army and civilians. Today, defense companies are racing to develop the lasers, microwave weapons, and technology necessary for confronting the next drone threat. Seth J. Frantzman takes the reader from the midnight exercises with Israel’s elite drone warriors, to the CIA headquarters where new drone technology was once adopted in the 1990s to hunt Osama bin Laden. This rapidly expanding technology could be used to target nuclear power plants and pose a threat to civilian airports. In the Middle East, the US used a drone to kill Iranian arch-terrorist Qasem Soleimani, a key Iranian commander. Drones are transforming the battlefield from Syria to Libya and Yemen. For militaries and security agencies—the main users of expensive drones—the UAV market is expanding as well; there were more than 20,000 military drones in use by 2020. Once the province of only a few militaries, drones now being built in Turkey, China, Russia, and smaller countries like Taiwan may be joining the military drone market. It’s big business, too—$100 billion will be spent over the next decade on drones. Militaries may soon be spending more on drones than tanks, much as navies transitioned away from giant vulnerable battleships to more agile ships. The future wars will be fought with drones and won by whoever has the most sophisticated technology.

click the book cover to download free

#click the book cover to download free#Drone Wars: Pioneers#Killing Machines#Artificial Intelligence#the Battle for the Future#ai

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

Personally, I think the only moral way to go about retaliation… is a ground war… entering and clearing out tunnels. Door to door, through the entirety of Gaza. However, the attrition that would be suffered would be immense.

I get why they’ve leveled city blocks, and hit densely populated areas. It avoids massive losses in manpower - losses that could threaten their security even against opportunistic nations.

But it doesn’t mean that it is morally correct to bomb out entire neighborhoods. 65% of Gazans are under the age of 24. Something just below… like… half are 18 or younger. Cutting off all food, water, and electricity… indiscriminately… is inhumane - especially for a population of two million. Israel is out there starting to commit genocide against Palestinians… when something like 60% of Palestinians want peace with Israel. Palestinians don’t exactly control Hamas.

At the end of the day, Hamas is a non-state actor - and does not speak for all of Palestine. Israel is a full state with a functioning government. The mantle of responsibility falls on Israel to act moral, and just in how they retaliate. To bomb innocent Palestinians for the actions of Hamas is immoral.

Death to Hamas. Death to Zionists. But may Palestinians and Jews, in general, find peace.

Hamas does not speak for Palestinians, but it does control Gaza, and that’s the crux of the issue.

Honestly, it’s going to be a really awful war, the battles of Grozny will look like a military rehearsal compared to a ground invasion of Gaza, and it’s probably going to be Mosul times 20, if not Stalingrad 2.0.

As for peace, the first step if for the Arab world to finally accept Israel’s existence, that’s the only way a true path for peace can begin.

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Israel is fighting perhaps the most precise, restrained, and disciplined war in the history of modern conflict. Unlike the wars of the US (and the UK and other Western countries) in Iraq, or campaigns against Libya and Serbia, which were designed to achieve strategic objectives or intervene in foreign conflicts, Israel’s war is against an enemy that actually invaded, committed terrible depredations, and is committed to doing so again and again. And Hamas’s Simchas Torah attack was just one prong of an Iranian proxy war against the Jewish state, paralleled by attacks from Lebanon, Syria, and Yemen. Yet around the world, Israel finds itself under diplomatic offensive, facing sanctions, arms embargoes, and broad condemnation.

To understand how remarkable the accusations against Israel are, one needs to know about how other countries fight wars. It is never sterile. Especially in urban combat, civilian casualties are unavoidable — and not illegal. Take some recent examples.

The Battle of Mosul in 2016 involved an effort by a US-led coalition to flush out a few thousand remnants of ISIS from a major city in northern Iraq. The nine-month battle began with the imposition of a siege and ended with nearly 10,000 civilians dead — more than the numbers of ISIS fighters that had been in the city. The entire town was reduced to rubble and its population displaced primarily by US-led aerial bombardment. A similar fate befell Raqqa in Syria. In Gaza, by comparison, the civilan casualty rate is about 13% — despite Hamas’s embedding of their entire military apparatus under civilian facilities.

Yet President Biden insists — Raqqa for me, but no Rafah for thee.

Israel, perversely, stands accused of genocide, though there are no allegations of Israel intentionally striking civilian targets. Rather the complaint is that Israel permits “disproportionate” civilian casualties in strikes on legitimate Hamas targets. Yet the ratio of combatant-to-civilian casualties is between 1:1 and 1:2 — far better than ratios of 1:3 or more in similar conflicts by other Western countries. Denunciations of Israel’s conduct amount to saying that the Jewish state is not allowed to effectively defend itself.

Indeed, the transient and ephemeral “support” Israel enjoyed after October 7 began to disappear as soon as it became clear it would vigorously defend itself. Before October 7, Western liberals had certain deeply held beliefs, which often reflected a projection of their national histories onto the Jews. Among those beliefs was that Western colonialism is the root cause of violence in the Third World, and “native” peoples have an inherent right to kill interlopers in their territory in the same way, say, Englishmen don’t. Related beliefs held that Islamic terror groups are just like everyone else, they just want their grievances addressed.

For Israel, this meant that settlements are the root cause of Arab violence. Palestinian factions just want to live with “dignity.” All these narratives melted in the explosion of savage, atavistic violence.

Perhaps if Israel had turned the other cheek, as the Biden administration has done when faced with repeated Iranian-backed attacks on US troops and international shipping, world sympathy would have lasted through the shloshim. But should we be surprised that a US that lets its borders be violently torn down and overrun should not understand a Jewish state that stands its ground?

As always, the Jews are the Ivri, the rejection of the regnant ideas, which for the West today is civilization’s self-hatred. October 7, and Israel’s subsequent defense, exploded the narratives of Western liberal elites, and for that, they will never forgive us.

The Biden administration in particular has steadily ratcheted up its hostility to Israel. It is reportedly slowing weapons shipments; imposing sanctions on Jews (but not PA terrorists) in Judea and Samaria; allowing the UN Security Council to pass a resolution demanding an immediate cease-fire, without the release of hostages; and most consequentially, demanding that Israel stand down before it has entered Hamas’s last stronghold of Gaza, where the hostages are kept. All this is consistent with President Biden’s view that Israel’s reaction to October 7 has been “over the top.”

Some wish to explain this as a response to details of electoral politics, in particular, the vocal demands of 10,000 or so Arab voters in Michigan. But this seems an unlikely explanation. For one, this demographic is relatively small, and certainly would not switch to Trump. Second, Biden’s increasing hostility to Israel coincides well with that of other left-leaning Western politicians in countries like Spain and France, who are not facing election-year pressures.

In short, Biden’s overall position on the war — yes, Israel can defend itself but not successfully — is more about pressure from the broader left flank of the Democratic Party. Which means that Israel can expect more of such treatment, and worse, from the US in the future.

4 notes

·

View notes