#austria 1809

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Elie Baudus about Bessières at Wagram and Znaim

Translated from Études sur Napoléon, Tome I

According to Napoleon's own admission, this action [the battle of Wagram] had not had the advantageous results he had promised; this can be judged by the words he addressed to Marshal Bessières when the latter had recovered from the severe contusion he had received. After saying to him: “Bessières, the bullet that hit you made my guard cry; thank it; it must be very dear to you”, the emperor added: “Your wound cost me twenty thousand prisoners that we would have taken if you had remained at the head of my cavalry; it lacked a leader. Without this unfortunate cannon shot, the Austrian monarchy would have been finished.”

And in a footnote the author adds, with regards to Gourgaud’s book about Ségur’s book:

Since we are talking about this period of the Austrian campaign, in 1809, we will point out an error that undoubtedly confused memories caused Monsieur Gourgaud to make in his refutation of Monsieur de Ségur's work on the Russian campaign. He says: ‘In front of Znaim, at the moment when the Prince of Lichtenstein came to propose an armistice, Marshal Bessières insisted to Napoleon that he should give battle. No,’ replied the Emperor, ’enough blood has been spilt. And he signed the armistice’. GOURGAUD, p. 55. - Marshal Bessières could not have uttered the words attributed to him by General Gourgaud, because the consequences of his wound kept him in bed in Vienna at the time when he made him talk like this at Znaïm. If it had been advantageous to give battle, the Marshal would not have had to bear the frightening responsibility for such advice; Napoleon would not have hesitated; he would even have been guilty of acting otherwise, of allowing himself to be held back by a feeling of humanity that was all the more false because it would have rendered useless all the blood already spilt, a feeling, moreover, that was very alien to him when it came to his own interests.

#napoleon's marshals#jean baptiste bessières#battle of wagram#fifth coalition war#campaign of 1809#austria 1809#napoleonic era

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

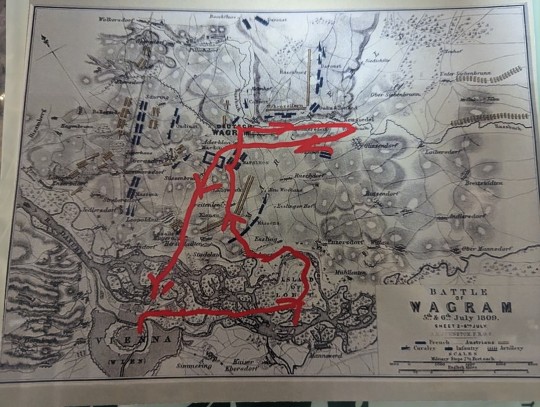

At the very bottom of the map there’s Kaiserebersdorf, where Lannes had died a couple of weeks before. 😥

With no context other than she "cut it out of a magazine and it took it to the copy store to enlarge it", my husband's grandma gave me this Battle of Wagram map in varying sizes. Unfortunately it is a little blurry in all of them.

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

The History of Santa Claus

Santa Claus—otherwise known as Saint Nicholas or Kris Kringle—has a long history steeped in Christmas traditions. Today, he is thought of mainly as the jolly man in red who brings toys to good girls and boys on Christmas Eve, but his story stretches all the way back to the 3rd century, when Saint Nicholas walked the earth and became the patron saint of children.

Santa Claus wasn't always "chubby and plump, a right jolly old elf." PHOTOGRAPH BY CLASSICSTOCK/CORBIS

The Legend of Saint Nicholas

The legend of Santa Claus can be traced back hundreds of years to a monk named St. Nicholas. It is believed that Nicholas was born sometime around A.D. 280 in Patara, near Myra in modern-day Turkey. Much admired for his piety and kindness, St. Nicholas became the subject of many legends.

One of the best-known St. Nicholas stories is the time three young girls are saved from a life of prostitution when young Bishop Nicholas secretly delivers three bags of gold to their indebted father, which can be used for their dowries. He was very religious from an early age and devoted his life entirely to Christianity. The strict saint took on some aspects of earlier European deities, like the Roman Saturn or the Norse Odin, who appeared as white-bearded men and had magical powers like flight. He also ensured that kids toed the line by saying their prayers and practicing good behavior. In continental Europe (more precisely the Netherlands, Belgium, Austria, the Czech Republic and Germany), he is usually portrayed as a bearded bishop in canonical robes.

During the Middle Ages, often on the evening before the anniversary of his death, December 6, children were bestowed gifts in his honour. By the Renaissance, St. Nicholas was the most popular saint in Europe. Even after the Protestant Reformation, when the veneration of saints began to be discouraged, St. Nicholas maintained a positive reputation, especially in the Netherlands.

Coming to America

In the Netherlands, kids and families simply refused to give up St. Nicholas, or Sinterklaas as the saint is called in Dutch, as a gift bringer. They brought Sinterklaas with them to New World colonies. St. Nicholas made his first inroads into American popular culture towards the end of the 18th century. In December 1773, and again in 1774, a New York newspaper reported that groups of Dutch families had gathered to honor the anniversary of his death.

The name Santa Claus evolved from Nick’s Dutch nickname, Sinter Klaas, a shortened form of Sint Nikolaas (Dutch for Saint Nicholas). In 1809, Washington Irving helped to popularize the Sinter Klaas stories when he referred to St. Nicholas as the patron saint of New York in his book, The History of New York. As his prominence grew, Sinter Klaas was described as everything from a “rascal” with a blue three-cornered hat, red waistcoat, and yellow stockings to a man wearing a broad-brimmed hat and a “huge pair of Flemish trunk hose.” An appearance that was more derived from the English 'Father Christmas' and was quite different from the Dutch Sinterklaas.

Santa Equivalents Around The World

Eighteenth-century America’s Santa Claus was not the only St. Nicholas-inspired gift-giver to make an appearance at Christmastime. There are similar figures and Christmas traditions around the world.

The English legend explains that Father Christmas visits each home on Christmas Eve to fill children’s stockings with holiday treats. Father Christmas dates back as far as 16th century in England during the reign of Henry VIII, when he was pictured as a large man in green or scarlet robes lined with fur. He typified the spirit of good cheer at Christmas, bringing peace, joy, good food and wine and revelry. As England no longer kept the feast day of Saint Nicholas on 6 December, the Father Christmas celebration was moved to 25 December to coincide with Christmas Day.

In the Netherlands and Belgium, the character of Santa Claus competes with that of Sinterklaas, based on Saint Nicholas. Santa Claus is known as de Kerstman in Dutch ("the Christmas man") and Père Noël ("Father Christmas") in French. For children in the Netherlands, Sinterklaas still remains the predominant gift-giver in December mostly celebrated on Sinterklaas evening the day before 6 December.

In Germany, the Christmas season is marked by the presence of two significant figures: Weihnachtsmann and Das Christkind or Christkind'l. Weihnachtsmann, a term that literally translates to "Christmas Man," is the German counterpart to Santa Claus. In contrast, Das Christkind, meaning "The Christ Child," represents a more traditional and religious aspect of German Christmas celebrations. Christkind was believed to deliver presents to well-behaved Swiss and German children on Christmas Eve. The name "Kris Kringle", a common variant of Santa in parts of the United States is derived from Christkind.

In Nordic folklore, the figure known as Tomte or Jultomten holds a special place in Christmas traditions. Originating from Swedish and Scandinavian mythology, Tomte is a small, mythical creature often depicted as a friendly, bearded being resembling a garden gnome and wearing a red cap. During the Christmas season, Tomte takes on a role similar to that of Santa Claus, delivering presents to children in a sleigh drawn by goats on the night of December 24th.

In Icelandic folklore, the Yule Lads, or "Jólasveinar," are mischievous characters associated with the Christmas season. These thirteen brothers, sons of the mountain-dwelling trolls Grýla and Leppalúði, are known for their playful antics and sometimes slightly sinister behavior. Traditionally, the Yule Lads would visit homes in the thirteen nights leading up to Christmas, each leaving small gifts or playing pranks depending on the behavior of the children.

In Italy, the Christmas season is marked by the presence of two iconic figures: Babbo Natale and La Befana. Babbo Natale, the Italian counterpart to Santa Claus, shares many similarities with the global image of the jolly gift-bringer. The other Italian icon, La Befana, is a unique and beloved figure in Italian folklore. Unlike the festive and plump Babbo Natale, La Befana is portrayed as an old woman, often depicted as a haggard but kind witch. According to tradition, La Befana visits homes on the night of January 5th, leaving small gifts and sweets for children who have been good and a lump of coal for those who have been naughty.

In French-speaking regions, the iconic figure associated with Christmas gift-giving is Père Noël, also known as Papa Noël. Père Noël is akin to the global representation of Santa Claus, often depicted as a jolly and benevolent character who travels in a sleigh pulled by reindeer, embodying the spirit of generosity and joy during the festive season.

In Spain and many Spanish-speaking cultures, the Christmas season unfolds with the anticipation of visits from both Papa Noel and Los Reyes Magos, offering children a delightful blend of traditions. Papa Noel, the Spanish equivalent of Santa Claus, is eagerly awaited on the night of December 24th. Following this, the celebration continues with the arrival of three kings known as “Los Reyes Magos” on January 6th. This holiday is known as Three Kings' Day or Día de Reyes. On the night before Día de Reyes, children place their shoes or small containers filled with hay under their beds for the Kings' camels. In return, Los Reyes Magos leave gifts, sweets, and small toys, creating a magical and cherished experience for children who wake up to the joyous surprises.

In Russia, instead of Santa, there is Ded Moroz and his granddaughter Snegurochka, who deliver gifts to children on New Year’s Eve. Children would sing Russian songs around the yolka.” A yolka is a coniferous tree similar to a Christmas tree. Ded Moroz is described as a grandfather with a long white beard.

Mikuláš (also known as Saint Nicholas) is the father of Christmas in the Czech Republic, as well as in Hungary. Mikuláš looks like the Pope and Santa combined. However Mikuláš is not always the person delivering presents on Saint Nicholas Day, it is typically believed to be Jesus. Saint Nicholas Day in the Czech Republic is predominantly celebrated on Dec. 5-6, although depending on the region, it is also celebrated on Dec. 25. Children put a boot out on the eve of Saint Nicholas Day and hope to find it full of candy and toys from Jesus in the morning. Bad kids can expect only a wooden spoon in their shoe.

In Japan Hoteiosho, or Hotei, is the equivalent of Santa pictured as a fat man with eyes in the back of his head who can tell if kids are naughty or nice. He is also known as the “Laughing Buddha,” because he is often depicted with a jovial face and surrounded by grinning children. Hotei is one of the Seven Lucky Gods, stemming from ancient Chinese and Indian religion. Hotei may have been based on a real person, named Budai, a man who died in 916 A.D. and was later worshipped in Buddhist practice.

So far a selection of customs and traditions similar to Santa Claus. Of course there are more, and in many traditions parallels to other cultures can be found.

sources; history.com, nationalgeographic.com, wikipedia

#santa claus#saint nicholas#kris kringle#sinterklaas#father christmas#pere noel#papa noel#history#jultomten#christmas eve#december 6#december 24#yule lads#weihnachtsmann#christkindl

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hello hello

So, I have been thinking....there is pretty much NO information about the Iliriyan provinces online....it is extremely hard to come by

That lead me to compile as many pictures as I could with the resources I had on hand, before I start some pictures might be bad quality becouse I took them on my phone with bad lighting...sorry 😅

A monument built in 1808 to honor Marmont, Trogir- Croatia

It's whole purpose was just to look pretty

The Napoleon monument in Makraska

It has nothing to do with Napoleon, it was built to honor Marmont

Border stone for the Iliriyan provinces, Zagreb-Croatia

It marked the border between the french and austrian sides

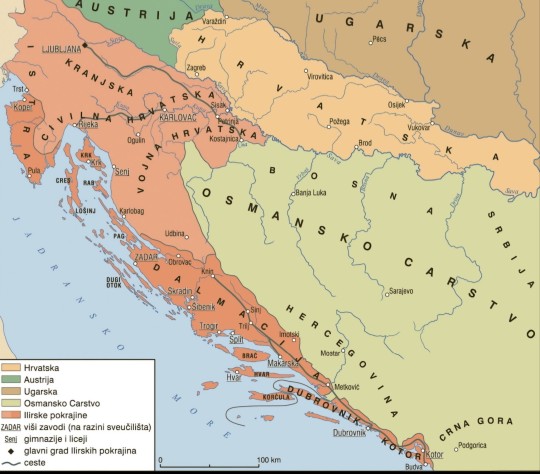

Map of the Iliriyan provinces

Orange marks the provinces,light green the ottoman empire,dark green Austria,light orange Croatia and the brown is Hungary (Ugarska/Vugarska)

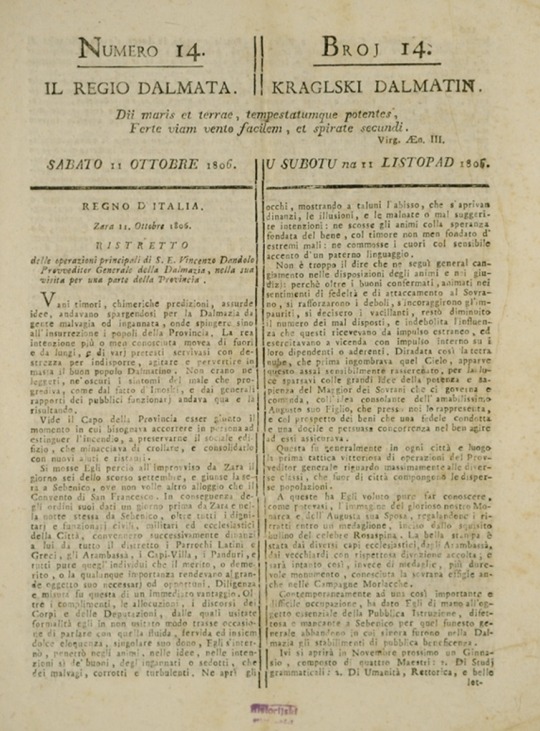

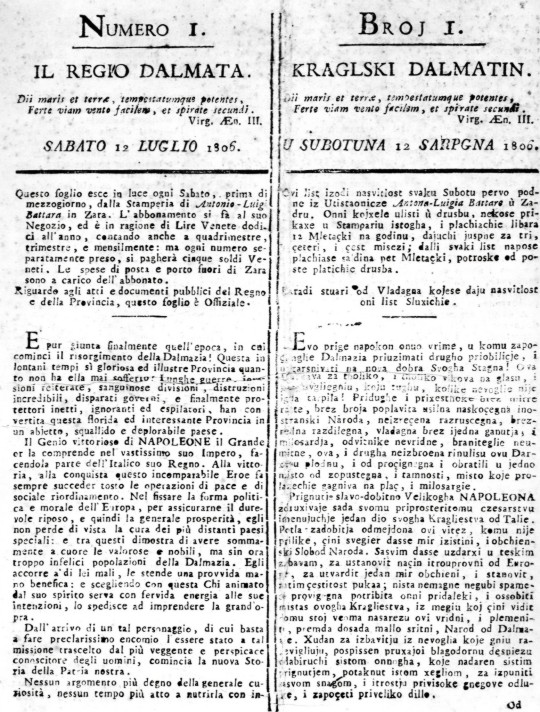

Pages of the Kraglski dalmatin/Royal dalmatian

Aka the first ever croatian news paper in both italian and croatian, which was print by the french

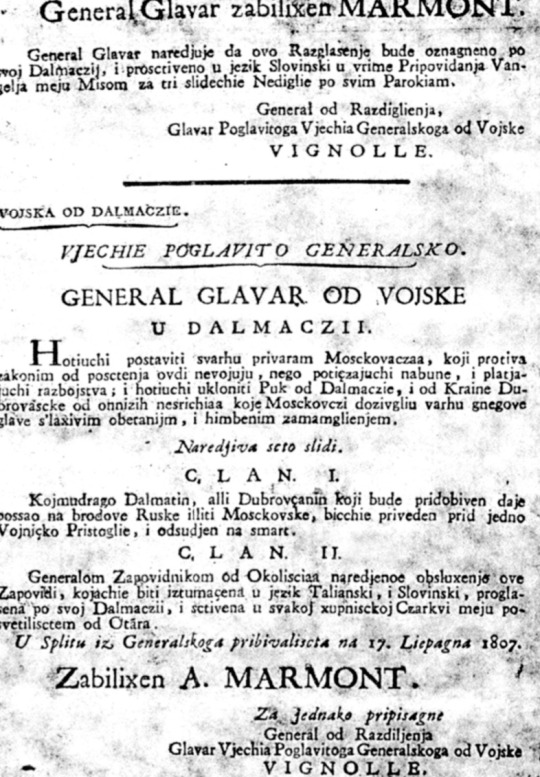

A law signed by Marmont preventing the arrival of Russian boats in iliran docks

French wear house in Slunj, Croatia

Clerks seal, around 1809 from the city of Karlovac in Croatia

Ilirian coat of arms,1809

Next post will be the uniforms!

Check reblogs

#napoleonic wars#history#croatian history#croatia history#auguste de marmont#auguste marmont#Iliriyan provinces#ilirian provinces#geography#historical documents#drawing refrence#napoleon#marmont

47 notes

·

View notes

Text

Royal Birthdays for today, January 9th:

Dai Zong, Chinese Emperor, 727

Meisho, Empress Regnant of Japan, 1622

Queen Sinjeong, Korean Royal, 1809

Frederica of Hanover, Baroness von Pawel-Rammingen, 1848

Theresa of Austria, Princess of Bavaria, 1931

Catherine, Princess of Wales, 1982

#emperor dai zong#empress meisho#frederica of hanover#theresa of austria#kate middleton#Queen Sinjeong#royal birthdays#long live the queue

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hon. Emma (Crewe) Cunliffe, later Emma Cunliffe-Offley

Artist: Thomas Lawrence (British, 1769-1830)

Date: c. 1809-1830

Medium: Oil on canvas

Collection: The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens, San Marino, CA, United States

Hon. Emma (Crewe) Cunliffe, later Emma Cunliffe-Offley British, 1780 - 1850

Elizabeth Emma Crewe was born February 15, 1780, the only surviving daughter of John Crewe (1742-1829) of Crewe Hall, Cheshire, and his wife Frances Anne Greville Crewe (1744-1818). Her father was created 1st Baron Crewe in 1806 in recognition of loyal service to the Whig party during forty-eight years as a member of parliament. But it was her mother's legendary beauty, intelligence, and political zeal that attracted a galaxy of political and cultural luminaries to the family circle.

As a young girl, Emma Crewe garnered high praise from Fanny Burney, who found her "extremely well bred, sensible, attentive, & intelligent" and "promising to resemble mentally her charming Mother." She delighted in music and often performed as a singer at social gatherings. Numerous contemporary accounts attest to her considerable ability.

On March 16, 1809 the painter Thomas Lawrence reported to a friend that Emma Crewe had refused a marriage proposal from Sir W.W. Wynne. One month later, on April 21, 1809, she married Foster Cunliffe (1782-1832) of Acton Park, Wrexham, elder son of Sir Foster Cunliffe (1755-1834), 3rd Baronet, and his wife Harriet. Having no children of their own, she and her husband later assumed responsibility for raising their young niece, the Hon. Annabella Crewe (1814-1874), daughter of Emma's elder brother John, 2nd Baron Crewe (1772-1835).

1829, on inheriting the property of Madeley, Staffordshire, her husband adopted the surname Offley, by which her own family had been known prior to the early eighteenth century. Following her husband's death on April 19, 1832, Emma Cunliffe-Offley spent several years traveling with her niece in Germany, Austria, and Italy. She returned briefly to England on the death of her mother in December 1835, when it was observed that she would have perished from grief, had it not been for the affectionate support of her niece. It was to Annabella that Emma Cunliffe-Offley left the present painting (together with furnishings at Madeley and at her house in Upper Brook Street) when she died on February 15, 1850.

#portrait#woman#painting#oil on canvas#british culture#three quarters length#white empire dress#white lace hood#gold mantle#dog#landscape#thomas lawrence#british painter#british art#british history#artwork#european art

10 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Battle of Wagram

The Battle of Wagram (5-6 July 1809) was one of the largest and bloodiest battles of the Napoleonic Wars (1803-1815). It resulted in a pyrrhic victory for French Emperor Napoleon I (r. 1804-1814; 1815) whose army crossed the Danube River to defeat Archduke Charles' Austrian army. Wagram ultimately allowed Napoleon to win the War of the Fifth Coalition (1809).

Background

Ever since its defeat at the Battle of Austerlitz (2 December 1805), the Austrian Empire itched to exact revenge upon Napoleon and recover its status as a major power in Central Europe. In the three years that followed the battle, Austria bided its time as its army was modernized by Archduke Charles, brother of the emperor and commander-in-chief of the Austrian forces. Charles' reforms included a system of mass conscription through the Landwehr militia and a reorganization of the army into nine line and two reserve corps, copying the corps d'armee system that had contributed to Napoleon's success.

By early 1809, hundreds of thousands of French soldiers were off in Iberia fighting the Peninsular War (1807-1814) against Spain and Portugal. This greatly reduced France's military presence in Germany, an opportunity that Austrian Emperor Francis I was keen to take advantage of. Francis ordered his brother to prepare for war, and on 10 April 1809, Archduke Charles sparked the War of the Fifth Coalition when he invaded France's ally of Bavaria with 200,000 men. Napoleon was prepared; having noticed the build-up of Austrian forces, the French emperor had raised a new Army of Germany that consisted mainly of French conscripts and allied German soldiers from the Confederation of the Rhine. Since Archduke Charles' invasion got off to a slow start, Napoleon was able to launch a rapid counteroffensive. In the ensuing Landshut campaign, Napoleon's Army of Germany won a string of battles and forced Archduke Charles back across the Danube. Charles' retreat left the road to Vienna wide open, and Napoleon occupied the Austrian capital on 13 May.

Emperor Francis had evacuated Vienna before the French occupation, and Archduke Charles had rallied his forces and was currently sitting on the opposite bank of the Danube. Since all the major bridges across the river had been destroyed, Napoleon needed to build his own. He chose the floodplain of Lobau Island, south of Vienna, as the ideal location for his river crossing. By midday on 20 May, the pontoon bridge was completed, and the first elements of the French army crossed over to occupy the towns of Aspern and Essling. By the next morning, Napoleon had gotten 25,000 troops across the river, but efforts to get the rest of his army across were frustrated by the Austrians, who floated flaming barges down the river to punch holes in the French bridge.

At 1 p.m. on 21 May, Archduke Charles ordered an attack. The French were surprised by the sudden Austrian assault, and brutal fighting erupted around Aspern and Essling that lasted well into the night, at which point the French retained control of both towns. The battle resumed on the morning of 22 May; while the Austrian wings were embroiled in the struggle for the towns, French Marshal Jean Lannes led a charge against the vulnerable Austrian center. His attack came close to success but was stopped by the personal intervention of Archduke Charles, who led a spirited counterattack. As the day wore on, the French were pushed out of Essling, and the bridge was repeatedly damaged, preventing Napoleon from getting the rest of his army across. At 3 p.m., the French emperor decided to cut his losses and ordered a withdrawal to Lobau. The Battle of Aspern-Essling marked Napoleon's first major defeat in a decade and had cost him between 20-23,000 casualties including the irreplaceable Marshal Lannes, who was mortally wounded. The Austrians also suffered around 23,000 casualties but achieved victory, having denied the river crossing to Napoleon.

Continue reading...

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

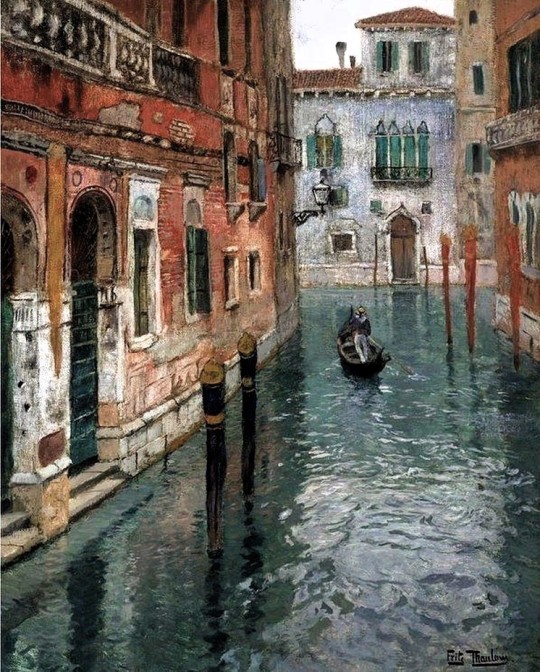

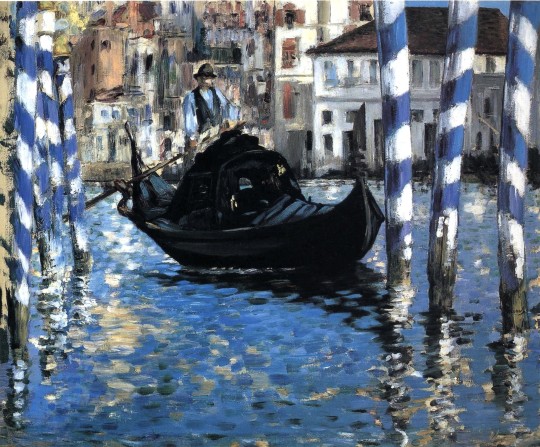

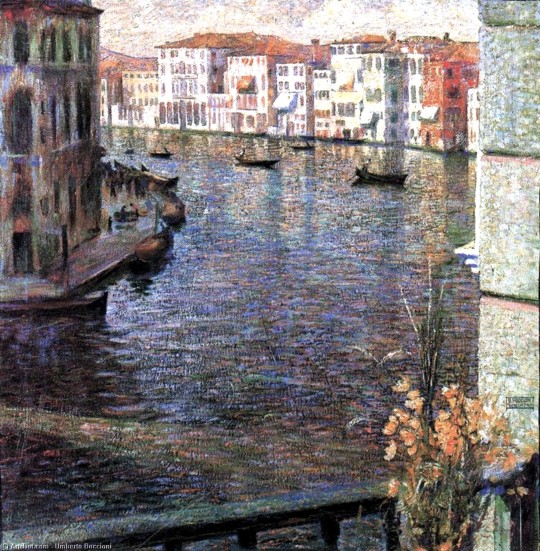

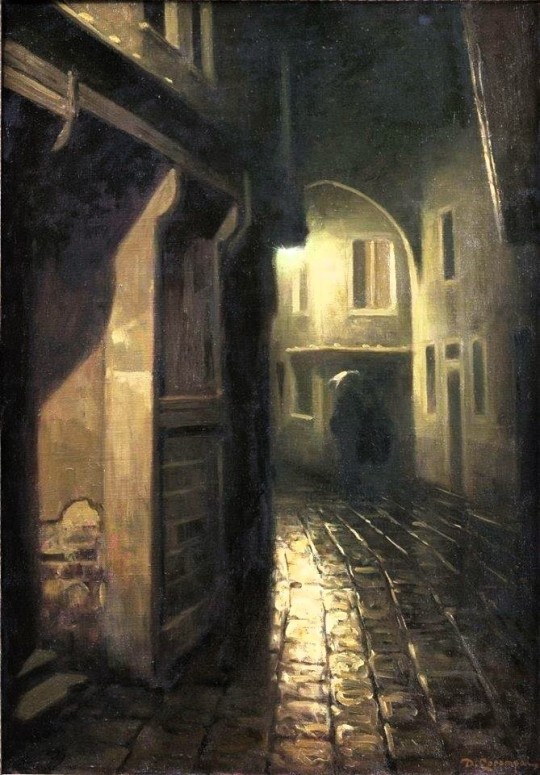

Venezia

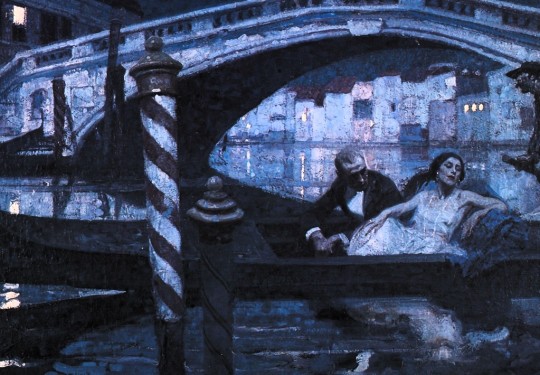

Anna Passini (the artist's wife), Palazzo Priuli, Venezia, 1866 ca. | Ludwig Passini (1832-1903, Austria)

One night in Venice, 1922 | Dean Cornwell (1892-1960, USA)

Venice in gold green blue shades | Dan Schlesinger (USA)

Il Ponte dei Sospiri, Venezia, 1870 | Gustave Doré (1832-1883, France)

Venice by moonlight, 1870 ca. | Sophus Jacobsen (1833-1912, Norway)

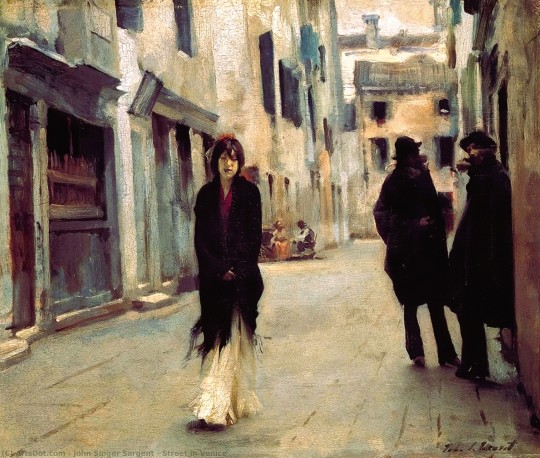

Scena di strada a Venezia (Street scene in Venice), 1882 (National Gallery of Art, Washington) | John Singer Sargent (1856-1925, USA)

Mareggiata, Chioggia, 1890's | Mosè Bianchi (1840-1904, Italia)

Il Molo al tramonto (The pier at sunset), Venezia, 1864 (Ca' Pesaro, Venezia) | Ippolito Caffi (1809-1866, Italia)

Festa del Redentore (Fireworks in Venice, the Feast of the Redeemer) | Vincenzo Abbati (1803-1866, Italia)

View of Venice, 1894 | Frits Thaulow (1847-1906, Norway)

Canal Grande, Venezia, 1874-75 (Shelburne Museum, Vermont, USA) | Édouard Manet (1832-1883, France)

Santa Maria dei Miracoli, Venice | Ken Howard (1932, England)

Canal Grande, Venezia, 1907 | Umberto Boccioni (1882-1916, Italia)

Calle di notte | Duilio Corompai (1875-1952, Italia)

Vetro di Murano, in 'Negozio Olivetti', piazza San Marco, Venezia, 2024 | Tony Craigg (1964, England)

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Women of Imperial Russia: Ages at First Marriage

I have only included women whose birth dates and dates of marriage are known within at least 1-2 years, therefore, this is not a comprehensive list. This data set ends with the Revolution of 1917.

Eudoxia Lopukhina, wife of Peter I; age 20 when she married Peter in 1689 CE

Catherine I of Russia, wife of Peter I; age 18 when she married Johan Cruse in 1702 CE

Anna of Russia, daughter of Ivan V; age 17 when she married Frederick William Duke of Courland and Semigallia in 1710 CE

Anna Petrovna, daughter of Peter I; age 17 when she married Charles Frederick I, Duke of Holstein-Gottorp, in 1725 CE

Catherine II, wife of Peter III; age 16 when she married Peter in 1745 CE

Natalia Alexeievna, wife of Paul I; age 17 when she married Paul in 1773 CE

Maria Feodorovna, wife of Paul I; age 17 when she married Paul in 1776 CE

Elizabeth Alexeivna, wife of Alexander I; age 14 when she married Alexander in 1793 CE

Anna Feodorovna, wife of Konstantin Pavlovich; age 15 when she married Konstantin in 1796 CE

Alexandra Pavlovna, daughter of Paul I; age 16 when she married Archduke Joseph of Austria in 1799 CE

Elena Pavlovna, daughter of Paul I; age 15 when she married Frederick Louis, Duke of Mecklenburg-Schwerin in 1799 CE

Maria Pavlovna, daughter of Paul I; age 18 when she married Charles Frederick, Grand Duke of Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach in 1804 CE

Catherine Pavlovna, daughter of Paul I; age 21 when she married Duke George of Oldenburg in 1809 CE

Anna Pavlovna, daughter of Paul I; age 21 when she married William II of the Netherlands in 1816 CE

Alexandra Feodorovna, wife of Nicholas I; age 19 when she married Nicholas in 1817 CE

Joanna Grudzinska, wife of Konstantin Pavlovich; age 29 when she married Konstantin in 1820 CE

Elena Pavlovna, wife of Mikhail Pavlovich; age 17 when she married Mikhail in 1824 CE

Maria Nikolaevna, daughter of Nicholas I; age 20 when she married Maximilian de Beauharnais, Duke of Leuchtenberg, in 1839 CE

Maria Alexandrovna, wife of Alexander II; age 17 when she married Alexander in 1841 CE

Elizaveta Mikhailovna, daughter of Mikhail Pavlovich; age 17 when she married Adolphe, Grand Duke of Luxembourg, in 1844 CE

Alexandra Nikolaevna, daughter of Nicholas I; age 19 when she married Prince Frederick-William of Hesse-Kassel, in 1844 CE

Olga Nikolaevna, daughter of Nicholas I; age 24 when she married Charles I of Wurttemberg, in 1846 CE

Alexandra Iosifovna, wife of Konstantin Nikolaevich; age 18 when she married Konstantin in 1848 CE

Catherine Mikhailovna, daughter of Mikhail Pavlovich; age 24 when she married Duke Georg August of Mecklenburg-Strelitz, in 1851 CE

Alexandra Petrovna, wife of Nicholas Nikolaevich the Elder; age 18 when she married Nicholas in 1856 CE

Olga Feodorovna, wife of Michael Nikolaevich; age 18 when she married Michael in 1857 CE

Maria Feodorovna, wife of Alexander III; age 19 when she married Alexander III in 1866 CE

Olga Konstantinovna, daughter of Konstantin Nikolaevich; age 16 when she married George I of Greece in 1867 CE

Vera Konstantinovna, daughter of Konstantin Nikolaevich; age 20 when she married Duke Eugen of Wurttemberg in 1874 CE

Maria Pavlovna, wife of Vladimir Alexandrovich; age 20 when she married Vladimir in 1874 CE

Maria Alexandrovna, daughter of Alexander II; age 19 when she married Alfred, Duke of Edinburgh, in 1874 CE

Anastasia Mikhailovna, daughter of Michael Nikolaevich; age 19 when she married Friedrich Franz III, Duke of Mecklenburg-Schwerin in 1879 CE

Nadezhada Alexandrovna Dreyer, wife of Nicholas Konstantinovich; age 21 when she married Nicholas in 1882 CE

Elizabeth Feodorovna, wife of Sergei Alexandrovich; age 20 when she married Sergei in 1884 CE

Olga Valerianovna Paley, wife of Paul Alexandrovich; age 19 when she married Erich von Pistolhkors in 1884 CE

Elizabeth Mavrikievna, wife of Konstantin Konstantinovich; age 19 when she married Konstantin in 1885 CE

Anastasia of Montenegro, wife of Nicholas Nikolaevich the Younger; age 21 when she married George Maximilianovich, Duke of Leuchtenberg in 1889 CE

Milica of Montenegro, wife of Peter Nikolaevich; age 23 when she married Peter in 1889 CE

Alexandra of Greece and Denmark, wife of Paul Alexandrovich; age 19 when she married Paul in 1889 CE

Sophie Nikolaievna, wife of Michael Mikhailovich; age 23 when she married Michael in 1891 CE

Victoria Feodorovna, wife of Kirill Vladimirovich; age 18 when she married Ernest Louis, Grand Duke of Hesse, in 1894 CE

Xenia Alexandrovna, wife of Alexander Mikhailovich; age 19 when she married Alexander in 1894 CE

Alexandra Feodorovna, wife of Nicholas II; age 22 when she married Nicholas in 1894 CE

Olga Alexandrovna, daughter of Alexander II; age 18 when she married Count George-Nicholas von Merenberg in 1985 CE

Maria of Greece and Denmark, wife of George Mikhailovich; age 24 when she married George in 1900 CE

Alexandra von Zarnekau, wife of George Alexandrovich; age 16 when she married George in 1900 CE

Catherine Alexandrovna, daughter of Alexander II; age 23 when she married Alexander Baryatinksy in 1901 CE

Olga Alexandrovna, daughter of Alexander III; age 19 when she married Duke Peter Alexandrovich of Oldenburg

Elena Vladimirovna, daughter of Vladimir Alexandrovich; age 20 when she married Prince Nicholas of Greece and Denmark in 1902 CE

Natalia Brasova, wife of Michael Alexandrovich; age 22 when she married Sergei Mamontov in 1902 CE

Elisabetta di Sasso Ruffo, wife of Andrei Alexandrovich; age 31 when she married Alexander Alexandrovitch Frederici in 1907 CE

Maria Pavlovna, daughter of Paul Alexandrovich; age 18 when she married Prince Wilhelm of Sweden in 1908 CE

Helen of Serbia, wife of Ioann Konstantinovich; age 27 when she married Ioann in 1911 CE

Tatiana Konstantinovna, daughter of Konstantin Konstantinovich; age 21 when she married Konstantine Bagration of Mukhrani, in 1911 CE

Irina Alexandrovna, daughter of Alexander Mikhailovich; age 19 when she married Felix Felixovich Yusupov in 1914 CE

Nadejda Mikhailovna, daughter of Michael Mikhailovna; age 20 when she married George Mountbatten in 1916 CE

Antonina Rafailovna Nesterovkaya, wife of Gabriel Konstantinovich; age 27 when she married Gabriel in 1917 CE

Nadejda Petrovna, wife of Nicholas Orlov; age 19 when she married Nicholas in 1917 CE

Anastasia Mikhailovna, daughter of Michael Mikhailovna; age 25 when she married Sir Harold Wernher in 1917 CE

59 women; average age at first marriage was 20 years old. The oldest bride was 31 at her first marriage; the youngest was 14.

19 notes

·

View notes

Photo

🌵 Fragmenta botanica, figuris coloratis illustrata. Viennae, Austriae: Typis Mathiae Andreae Schmidt, typogr. Universit., 1809.

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Galician campaign of 1809

Today let me tell you a little bit about the Galician campaign of the Austro-Polish war of 1809, which proved to be a great success for the Duchy of Warsaw.

After the battle of Raszyn there happened the series of small battles, which prevented Austrians from crossing the Vistula, thus leaving the initiative on the right bank of the river firmly with the Poles. So, the Polish forces under Poniatowski’s command moved along Vistula to the South-East, to the lands Austria seized during the latest partition of Poland.

On the 14th of May the Polish Army entered Lublin:

Konstanty Gorski, "Prince Józef Poniatowski enters conquered Lublin in 1809, showered with flowers by ladies"

As Kajetan Koźmian recalls in his memoirs, Poniatowski and his men were greeted with "joy and elation", and in the evening "... the city and the citizens gave a great ball <...> in the house in Korce. Prince Józef honored them with his presence starting the ball."

The next city on the way of the Polish Army was Sandomierz, and after a short siege it was taken on the 18th of May.

Siege of Sandomierz in 1809.

Michał Stachowicz, a scene from the battles in Galicia ("The Capture of Zamość")

Then there was Zamość, where the Polish trooped entered on the 20th of May.

Siege of 1809, M. Adamczewski Entry of Prince Poniatowski to Zamość (postcard)

On the 27th of May the Polish advanced forces even reached the city of Lwów, but prince Józef wasn’t among them.

Meanwhile the Austrians under command Archduke Ferdinand realized the precariousness of their position in the center of Poland, and on the 1st of June left Warsaw for the south.

Poniatowski, for his part, decided not to engage with the Austrian, focusing instead on "liberating” as much Galician land as possible.

Prince Józef Poniatowski seeks information from local peasants in Galicia in 1809, a photo of Stanisław Bagieński's painting

On the 3rd June there appeared the third participant of the events - Russian forces crossed the Austrian border to Galicia as well. And though formally they were acting as Napoleon’s ally, as was prescribed in the Tilsit Treaty, their real goal was to prevent the Poles from taking too much of the Austrian-held territories.

So, to outwit the Russians prince Józef was taking Galician cities not in the name of the Duchy of Warsaw, but in the one of emperor of the Frenchmen. Like the proclamations were being made in the name of Napoleon, the eagles on the coats-of-arms replacing the Austrian ones were not Polish and French etc.

Lancers lead Austrian prisoners of war near Kraków in 1809, in front of Prince Józef Poniatowski, a photo of Stanisław Bagieński's painting

Then, in the outer theater of war on the 6th of July the French defeated the Austrians at the Battle of Wagram. And according Franco-Austrian truce signed five days later the land division was to take place along the line where the troops were at the time of receiving news of the truce, not at the time its signing.

The Austrian army leaves Wawel, a postcard based on the painting of Wojciech Kossak

And so began the race between Russians and Poles, to advance to as farther as possible.

In the middle of July both armies reached Kraków.

PRINCE JOSEPH'S ENTRY TO KRAKOW. A drawing by Jan Feliks Piwarski.

And there the clash of the interest took place.

Poniatowski approached the city from the side of St. Florian's Gate, but it turned out that the Austrians, wanting more comfortable terms of capitulation, had already let Russian troops into Kraków.

The Russians, namely the Cossacks of General Sievers, wanted to deny Poniatowski passage. But Prince Józef, as Dezydery Chłapowski recalls in his memoirs, "draw his broadsword and with together his staff galloped into the gate through the Cossacks". The Polish infantry followed its commander "in a double step <...> so that the Cossacks were pressed against the walls of the gate." Seeing this, Mariampol's hussar regiment, which was stationed at that time in the market square, make a decision to put up resistance and due to this, the whole Polish army was able to enter the city.

Michał Stachowicz, The entry of Prince Józef Poniatowski into Krakow on July 15, 1809

Then, as Ambroży Grabowski recalled, when prince Józef’s troops reached the market square, “in front of the church of St. Wojciech, the magistrate went out to meet the prince, to give him the keys of the city”.

Józef Poniatowski in the Cathedral after Kraków was taken from the Austrians, an image by Stanisław Tondos and Wojciech Kossak

Most probably prince Józef visited the Wawel cathedral during his sojourn in Kraków that time. (In a small voice: little did he know that in 8 years he’ll be buried there...)

And after exactly a month since the Polish troops entered Kraków, there was a ball arranged in the Cloth-hall, the image depicting it I have already posted here.

#Poniatowski#Jozef Poniatowski#józef poniatowski#1809#Galicia#Lublin#Sandomierz#Zamość#Kraków#Austro-Polish War#Konstanty Gorski#Michał Stachowicz#Stanisław Bagieński#Wojciech Kossak#Feliks Piwarski#Kajetan Koźmian#Dezydery Chłapowski#ambroży grabowski

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

(Yes! A post about paintings that does not mention Soult … ooops.)

One impression I have got so far on reading up more on the medical service is that Dominique Larrey was an excellent self-promoter. (And no, that does not much endear him to me. But that's me.) In particular, he seems to have been very aware of the importance of (official, propagandistic) art in Napoleon’s Empire, and was keen on figuring in it. He was close friends with painter Anne-Louis Girodet, who after Larrey’s return from Egypt did a portrait of him:

After the battle of Eylau in 1807, when it became clear that the court would commission a painting of the battle, Larrey wrote to Girodet, who he believed would receive that job, in order to tell him that he wanted to be in that painting "in his function of chirurgien-inspecteur général". And just to be on the safe side, he added:

The advantage of being painted by you, my friend, will increase the satisfaction of my heart if I am fortunate enough to occupy a small corner of your canvas. If, against my expectations, you do not wish to treat this subject, please ask Monsieur Gros to grant me this satisfaction. It is a truth that he will place in his painting if he finds it worthy of being there.

Gros in the end did receive the commission – and added the guy to the painting who had actually been in charge of the surgeons during that campaign: Percy.

And then there’s the matter of Lannes’ death. Larrey on June 14 1809 writes a long letter to his wife (after, as he says, having been struck by deep melancholy ever since Lannes had died), and it ends with – yet another idea for how he could figure in a painting:

I wish someone had the idea of painting the moving scene in which the Emperor embraced his worthy friend carried on a stretcher, shortly after having undergone my operation. This is where I could appear with honour, if such a painting were ever done.

While trying to tell myself that a military surgeon who saw people dying every day must have felt very differently about the matter, I still can’t help but find this remark tasteless to the extreme. If he had said something about wanting to be remembered next to his friend or something, I would understand. But no. He wants to be in an official painting with Napoleon, and Lannes’ death is just a nice opportunity for that.

There is even a second letter regarding this matter. When Denon (on Larrey’s suggestion?) really commissioned a painting, the surgeon Ribes in Paris demanded some more details on the event. Larrey complied with this demand on 18 July 1809, adding:

At the request of M. Denon, military painter, who wants to depict the death of Lannes, Larrey sends this information to his friend, but expresses the formal wish that he not be named [as being involved in the matter]; he nevertheless takes the opportunity to ask to appear in this painting.

I do not know if there ever was an "official" painting done in the end. Part of me hopes no.

#napoleon's marshals#jean lannes#dominique larrey#battle of eylau#battle of aspern#prussia 1807#austria 1809#starting to wonder if anybody saw lannes as more than a stepping stone for one's one benefit

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

Giuseppe Donizetti — served Napoleon on Elba and accompanied him during the Hundred Days

Portrait of Giuseppe Donizetti later in life

Giuseppe Donizetti was born into poverty in 1788, in the Northern Italian city of Bergamo. The eldest of his siblings, he worked from a young age, training as a tailor’s apprentice. His true talent was in music, which was spotted early on in his life.

Giuseppe was conscripted in 1808 at the age of 20. He served the Napoleonic Kingdom of Italy in the Seventh Italian Regiment. He fought against Austria in the War of the 5th Coalition in 1809. He spent the years of 1811, 1812 and 1813 in Spain.

In 1811, he was became ill en route to Spain and was hospitalized at Castelnaudary in France. 43 years later in 1854, he wrote about it to the court of the Ottoman Empire:

“Constantinople, November 22, 1854. Mémoire to His Highness Achmed-Fethy Pasha. Finding myself in a comfortable position thanks to the beneficences of Our August and Glorious Sovereign, I cede to the Hospital of Castelnaudary (Aude), in which I was ill in 1811, the portion coming to me of the legacy left by the Emperor Napoleon I to the Battalion of the Island of Elba. The papers establishing my right to participate in the credit opened up by the Decree of August 5, 1854, issued at Biarritz by His Imperial Majesty the Emperor Napoleon III, I have been obliged to send to France at the time when I was honored with a brevet as Chevalier of the Legion of Honor. Your Highness's Very humble Servant, Joseph Donizetti.”

Location and photograph of Castelnaudary

After the dissolution of the Kingdom of Italy and the First French Empire, he enlisted in the French military and was stationed on the island of Elba as a military flutist. It was on Elba, in the town of Portoferraio, where he was married in 1815.

That same year, he accompanied Napoleon during the Hundred Days, traveling with him on the same ship from Elba to Antibes, France. He likely fought at the battle of Waterloo.

Landing of Napoleon I in Antibes in 1815

After Napoleon:

The Austrians took control of Northern Italy after the fall of Napoleon. According to the historian Emre Aracı, Giuseppe was “a greal admirer of Napoleon and the French […] Giuseppe strongly opposed his country’s domination by the Austrians. Evidence shows that he secretly took part in the Carbonari resistance and even appeared at court trials.”

Giuseppe Donizetti became a composer, and had a full career as Instructor General of the Imperial Ottoman Music. He even composed the first National Anthem of the Ottoman Empire, the Mecidiye Marşı. His main legacy is introducing Western marching music to the military of the Ottoman Empire.

He was employed by the Ottoman government on 17 September 1828 for an annual salary of 8,000 francs. This was considered a very high salary by his family. Giuseppe’s trouble with the Austrian authorities after the fall of Napoleon may have been a motivator for him to leave Italy. He moved to Constantinople at the age of 39 and spent the rest of his life there.

Giuseppe’s patron was Sultan Mahmud II, who ruled from 1808 to 1839, and Sultan Abdulmejid I, who ruled from 1839 to 1861.

According to the historian Emre Aracı:

“The Donizettis were so well-liked in the Ottoman capital that when fire broke out near their house Ahmet Fethi Pasha, the sultan's brother-in-law, ordered all the houses surrounding the maestro's home to be razed to the ground in order to prevent the flames reaching the building.”

Sultan Mahmud II

His brother, Gaetano, called him his fratello turco— Turkish brother, writing to his friend that “He loves Constantinople, to which he owes everything.”

Giuseppe even encouraged his brother to move to Constantinople, but Gaetano declined. “I do not want to play the fool like my brother, the Bey, who, after having earned more than I perhaps, stays there in ancient Byzantium to scratch his belly between the plague and the stake,” wrote Gaetano.

Giuseppe moved to Constantinople two years after the creation of the Imperial Musical School (Muzıka-i Hümâyûn), which was an Ottoman institution which trained its students in Western style of music. He was specifically recruited as an expert to help lead this effort.

Giuseppe’s younger brother, Gaetano. By Francesco Coghetti, 1837

Gaetano Donizetti, though younger than Giuseppe, became the much more successful and internationally well-known brother, producing nearly 70 operas in his life. Gaetano is considered one of the most successful opera composers in history. Because of this, Giuseppe is widely known as Gaetano Donizetti’s brother. The historian Emre Aracı pointed out that this has actually been good for Giuseppe’s reputation because it has enabled him to be remembered when many other composers have been forgotten.

Both brothers were awarded the Ottoman Order of Nișan-i Iftihar. When Gaetano received the award at the Ottoman Embassy in Paris, he proudly said: “Napoleon belongs to two centuries, I to two religions.”

Burial:

Giuseppe died in 1856, and is buried in the vaults of St. Esprit Cathedral, on the European side of Constantinople, in the district called Pera (now called Beyoğlu). According to Emre Aracı, the district “was once the home of a thriving Christian community”. The Church was built in 1846, 10 years before Giuseppe died.

Interior of St. Esprit Cathedral

Giuseppe and his brother Gaetano are two great success stories and examples of people from impoverished backgrounds who go on to live prosperous and interesting lives.

Sources:

Herbert Weinstock, Donizetti and the World of Opera in Italy, Paris and Vienna in the First Half of the Nineteenth Century, 1963

Emre Aracı, Giuseppe Donizetti at the Ottoman Court: A Levantine Life, The Musical Times, Vol. 143, No. 1880 (Autumn, 2002), pp. 49-56

Emre Aracı, Giuseppe Donizetti Pasha and the Polyphonic Court Music of the Ottoman Empire, The Court Historian, Volume 7, 2 December 2002

Özgecan Karadağli, Western Performing Arts in the Late Ottoman Empire: Accommodation and Formation, 2020

#Giuseppe Donizetti#Donizetti#napoleonic era#napoleonic#Ottoman Empire#ottoman#napoleon#napoleon bonaparte#gaetano donizetti#turkey#turkish history#ottoman history#first french empire#French empire#history#19th century#france#french history#the hundred days#Francesco Coghetti#Istanbul#Constantinople#1800s#19th century history#Napoleon’s soldiers#opera#composers#composer

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

On this day:

THE BAFFLING BENJAMIN BATHURST

On November 25, 1809, Benjamin Bathurst, secret British envoy to the royal court of Austria, traveling incognito as a wealthy merchant, went out into the street where his coach was being prepared to leave, walked around the front of the horses, and vanished into oblivion, never to be seen again. The incident took place as the obsessed Napoleon Bonaparte was conquering Europe with military force. Bathurst, immersed in diplomatic espionage, was gathering allies to oppose the self-crowned French emperor.

Anxiety had Bathurst carrying two pistols, his valet and secretary armed, and more guns stashed in his carriage in case of attack. Upon arriving in Perleberg, he went to the local garrison and pleaded for armed guards before entering the White Swan Inn for something to eat. The envoy was noticeable in his sable overcoat with its violet velvet lining and large diamond stickpin. A woman guest at the inn later commented that he was extremely nervous and unable to drink his tea without the cup shaking and tea spilling.

Lanterns provided only dim street lighting as Bathurst left the building. The hostler was finishing up with the horses, and the valet was loading baggage at the rear of the coach. The secretary was standing in the inn doorway, and soldiers were stationed at each end of the street. Bathurst was observed to have walked around the head of the horses, and that was the last anyone ever saw of him. The valet and secretary saw only each other as they circled the carriage. The secretary swore Bathurst did not return to the inn, and the soldiers had let no one pass. All of Perleberg was immediately searched, but no trace of the envoy was ever found.

Text from: Almanac of the Infamous, the Incredible, and the Ignored by Juanita Rose Violins, published by Weiser Books, 2009

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

01 Painting, The Art of War, Leander Russ' The Turks Storm the Lion's Bastion, with Footnotes

Leander Russ, 1809-1864The Turks Storm the Lion’s Bastion, c. 1837Oil on canvas207 x 285 cms | 81 1/4 x 112 insKunsthistorisches Museum, Wien | Austria The Battle of Kahlenberg on September 12, 1683 ended the Second Turkish Siege of Vienna . A German – Polish relief army under the leadership of the Polish King John III. Sobieski defeated the Ottoman army . The defeat marked the beginning of the…

View On WordPress

#army#Arthistory#Artists#Bastion#Biography#fineart#footnotes#History#Leander Russ#Lion#Ottoman#Paintings#war#Zaidan

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

JXKNFSD HELP I’M READING THE THREAD ABOUT THE IKEVAMP OCS AND CACKLING

Beethoven at Mozart: *treats him with respect* Yes sir, thank you for all your work.

Beethoven at Napoleon: Oh, you arch-ass! You double-barrelled ass! (And yes, this is an actual, genuine quote from the real Beethoven-)

Let me tell you, when it comes to insults, Beethoven does NOT hold back. He comes out SWINGING-

When Napoleon declared himself the Emperor of France, Beethoven was outraged, saying, “So he is no more than a common mortal! Now he, too, will tread underfoot all the rights of man [and] indulge only his ambition; now he will think himself superior to all men [and] become a tyrant!”

Oh, and one more thing about Beethoven and Napoleon! Apparently, Beethoven’s younger brother, Nikolaus Johann van Beethoven, was involved with him. His brother wished to be called Johann instead of Nikolaus, which Ludwig didn’t like; he hated his father, who was an alcoholic and pushed responsibility of taking care of the family on him when he was only 16. In 1808, Johann opened a medical pharmacy in Linz, Upper Austria. When Napoleon invaded Austria in 1809 and established a base camp in Linz for wounded soldiers, Johann actually supported the French by giving them medical supplies. Helping the enemy made him a hated citizen in his hometown, but because of his support, the French gave him money and this made him rich.

When Johann bought an estate in Gneixendorf in 1819, he signed a letter to Ludwig “From your brother Johann, landowner.” Ludwig signed his reply, “From your brother Ludwig, brain owner.”

Some personal impressions about Johann were actually written down in other sources! Gerhard von Breuning said that Johann “bore no resemblance whatever to his brother Ludwig.” Another person, Count Moritz Lichnowsky said of Johann during a conversation with Ludwig, “Everyone makes a fool of him; we call him simply 'The Chevalier'. — Everybody says his only merit is that he bears your name."

And of course, I am back at it again with quotes,, all of these are from Beethoven- 🚶 I love quotes from historical figures, and I am going to pester you with them. This is a threat 🫵 /lh

Beethoven: “Anyone who tells a lie has not pure heart, and cannot make good soup.”

Beethoven, speaking to royalty: “What you are, you are by accident of birth; what I am, I am by myself. There are and will be a thousand princes; there is only one Beethoven.”

Beethoven: “Even in poverty I lived like a king for I tell you that nobility is the thing that makes a king.”

Beethoven: “I like honesty and sincerity, and I maintain that an artist should not be shabbily treated.”

Beethoven: “I shall seize fate by the throat; it shall certainly never wholly overcome me.”

Beethoven: “How glad I am to be able to roam in the wood and thicket, among trees and flowers and rocks ... in the country, every tree seems to speak to me, saying, ‘Holy! Holy’, in the woods, there is enchantment which expresses all things.”

An extract from a letter from Beethoven: “The true artist is not proud, he unfortunately sees that art has no limits; he feels darkly how far he is from the goal; and though he may be admired by others, he is sad not to have reached that point to which his better genius only appears as a distant, guiding sun. I would, perhaps, rather come to you and your people, than to many rich folk who display inward poverty.”

Beethoven: “The world is a king, and like a king, desires flattery in return for favor; but true art is selfish and perverse — it will not submit to the mold of flattery.”

Beethoven: “It is my wish that you may have at better and freer life than I have had. Recommend virtue to your children; it alone, not money, can make them happy. I speak from experience; this was what upheld me in time of misery.”

Beethoven: “I have always reckoned myself among the greatest admirers of Mozart, and shall do so till the day of my death.”

Beethoven considered Mozart to be one of the musical immortals. When an admirer wrote to the young up-and-coming composer and even compared him to the greats, Beethoven replied, "do not rob Handel, Haydn, and Mozart of their laurel wreaths; they have earned theirs, but I am not yet entitled to one."

Also!! I'm so sorry for such a long post!! There was a lot I wanted to say 🤧

Jackdaw Anon 🐦

i feel bad because youre always writing essays in my inbox that i loev reading sm but i can only response with WOWIE and OMG TAHTS SO COOL :C i hope it doesnt bother you ^^

but all that aside, WOW beethoven sounds like a grumpy old man. but liek, the best version of a grumpy old man.

ITS SO NICE THAT HE ADMIRED MOZART SO MUCH :(((

“The true artist is not proud, he unfortunately sees that art has no limits; he feels darkly how far he is from the goal; and though he may be admired by others, he is sad not to have reached that point to which his better genius only appears as a distant, guiding sun. I would, perhaps, rather come to you and your people, than to many rich folk who display inward poverty.”

this hits different when you write fanfic and you feel like your work will never be as pretty and eloquent as other writers wow. beethoven was so real for that omg

ITS OKAY YOUR RAMBLES CAN BE LONG THATS FINE!!! i just have trouble writing long responses so i wont write in euqal length ^^; I PROMISE ILL READ EVERYTHING THOUGH

#plus my hands are like. in constant pain oops#DONT COME FO RME MOOTS YOU KNOW THIS ALREADY#jackdaw anon <3

8 notes

·

View notes