#augusta Bracknell

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

have you done your daily click

#best character named x#poll#poll game#augustus waters#augustus gloop#auggie pullman#augusta Bracknell#august booth#augusta elton#tfios#the fault in our stars#charlie and the chocolate factory#wonder#the importance of being earnest#once upon a time#emma

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lady Augusta Bracknell is the most memorable character and one who has a tremendous impact on the audience in Oscar Wilde's play "The Importance of Being Earnest". She is a fashionable woman in society, but her intimate knowledge of social niceties keeps her from thinking critically about her environment or the true character of the people around her. Lady Bracknell is utterly respectable, conservative, and proper. As a former member of the lower class, she represents the righteousness of the formerly excluded.

It's possible that Crowley referring to Aziraphale as "Lady Bracknell", is an affectionate way of mocking his always pristine clothes, impeccable manners, pattern of speech and strict rules (which he bends when it's necessary).

#goodomensedit#Good Omens#underbetelgeuse#useraurore#userksena#usertom#tuserpris#userange#arthurpendragonns#dixonscarol#noalook#userelio#usereena#userpayton#userkristi#userisaiah#alivedean#useremi#tuserhan#goodomensgifs#by mnie#I'm just having fun here with interpretation so don't be rude please

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

the importance of being earnest

Below, the first trailer for the play, which has no scenes from the play whatsoever:

youtube

I will note that there are some changes from the first trailer to the actual play as staged. Gatwa doesn't have the wig (I'm guessing that's a wig) and the brocade vest and white coat are from entirely separate outfits. They also appear to have made a fairly dramatic change in how Sharon D Clarke was to play Lady Bracknell and how she was costumed (more about that below).

The second trailer, which includes scenes from the play:

youtube

I am sad to report that I did not see the scenes with Gatwa in the pink gown playing the piano, which is reportedly the opening of the play. (I did miss the first couple of minutes.) My guess, given staging, is that this is meant to clue the audience in that this is a somewhat different production than the usual. I will also note, however, that the bits with Gatwa in a kilt and then a deerstalker, both without a shirt, also appear in the show. (That part is used to cover a scene change.)

And now, the plot in 30 seconds:

youtube

The National Theatre's own description reads:

A Trivial Comedy for Serious People

Being sensible can be excessively boring. At least Jack thinks so.

While assuming the role of dutiful guardian in the country, he lets loose in town under a false identity. Meanwhile, his friend Algy takes on a similar facade.

Unfortunately, living a double life has its drawbacks, especially when it comes to love. Hoping to impress two eligible ladies, the gentlemen find themselves caught in a web of lies they must carefully navigate.

The show itself is goddamn delightful, it is. Gatwa's Algernon is perfectly arch, as he should be. That said, I've never seen an Algernon played with such glee at things he's doing to make life difficult for his good friend John/Jack/Earnest (Hugh Skinner). Normally, Algernon is played more or less deadpan -- he's not usually trying to make Jack's life difficult, it just happens. In this production, he knows what he's doing, he knows what effect he's having, and he is vastly amused by the whole thing. Jack is arch (well, everyone's arch -- it's upper-class Victorian England, after all) and terribly confused much of the time.

Ronkẹ Adékoluẹjo plays Gwendolen, Algernon's cousin and Lady Bracknell's daughter. Her Gwendolen, as is usual, is somehow madly in love with Jack -- whose name she believes to be Earnest -- and also hot for his bod. Pretty much ready to climb him like a tree, really. It is a very unexpected interpretation of the role, but it works, and is quite a lot of fun to watch -- I hope it was as enjoyable to play as it looks.

Sharon D Clarke plays Lady Bracknell, Aunt Augusta. The original trailer, first one above, makes her look more like a proper Victorian English lady; the actual production changed tack and made her a proper Victorian Caribbean English lady, with head wrap and accent. She is perfectly deadpan throughout -- without Lady Bracknell as straight man, the entire enterprise would founder, I think. And, as past Ladies Bracknell have done, she delivers the line "A Handbag?" with her own style:

youtube

Eliza Scanlen plays Cecily, Jack's ward. A bit spoiled (well ... possibly a lot spoiled), somewhat sheltered, and who somehow falls in love with Algernon, who also falls in love with her. Somehow. (This is, frankly, one of the points that you just have to accept in the actual play -- it rather comes out of absolutely nowhere.) She and Gwendolen eventually discover that they have things in common, which leads to the denouement of everything.

The supporting roles are also very well cast and played, especially Julian Bleach in the dual roles of long-suffering servants Merriman (Jack's majordomo in the country) and Lane (Algernon's butler in the city). He does a lot with very little, especially as Lane.

One interesting change that they've made to the staging -- without making really any changes to the text, but for one line near the very end -- has to do with Algernon and Jack. Early on, the staging hints that Algernon and Jack may have had, as they said back then, "a pash" for each other. (I will note that in some ways it might be even funnier -- background information, if nothing else -- if you know about Ncuti Gatwa -- which I did -- and about Hugh Skinner -- which I did not.) By the end of the play, it's pretty clear that at some point it went well beyond a mere "pash" to being rather more than that. (Which, given the revelations at the end of the play, could seem somewhat problematic if people were allowed any time to think about them at all, but it really only becomes apparent at the very end of the play.) There are also some other things that are set up that make me almost wish for a slammed-doors bedroom farce, in which everyone thinks they're keeping secrets, but everyone knows only nobody knows that everyone knows, if you know what I mean.

Anyway, 10 out of 10, would watch again, and I really hope that they put this on the National Theatre At Home streaming site so that I can see it again. (Side note: it has a production of "All About Eve" with Gillian Anderson that I'm very curious about, but that's neither here nor there.)

Oh, and if you get to see "The Importance of Being Earnest", do stay for the cast bows at the end after the play proper. They are ... rather unexpected, let's say.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Okay this reminded me of a story.

When I was in high school, my drama teacher decided we were going to put on The Importance of Being Earnest. But, she decided we were going to gender bend it. So, Algernon became Angela and Gwendolyn became Glen. We made it gay. Oscar Wilde would be proud.

Anyway, I played Augusta Bracknell, and very quickly realised how easily my character could come across homophobic, so I knew the director was making some changes to the script and I sat down with her and said listen: I am not going to play this woman as a homophobe, so whatever changes you make to her dialogue, make that clear.

So she said, of course not, I'd never make you do that. You have no problem with your son being gay, you just think this man is a lazy hipster piece of crap.

It was amazing. I got to improv lines every night in the scene where I yelled at Jack to leave my son alone. I nearly pushed him off the edge of the stage. I nearly broke my own ankle in a dress rehearsal. The guy who played my son was older than me but called me Mom for three months. Sheer gay chaos.

Just discovered the reddit genre of “supportive parents of messy gay teens” and why is it weirdly heartwarming. We’re moving past “help my son is gay!” and towards “help my gay son has terrible taste in men!”

8K notes

·

View notes

Text

lady bracknell: you can’t marry mr. worthing

gwendolen:

yOu cAN’T mArRy mR WoRThiNg

#this was my character insight from tonight’s rehearsal#gwendolen fairfax#lady bracknell#augusta bracknell#oscar wilde#literature#mocking spongebob#meme#the importance of being ernest

53 notes

·

View notes

Text

FIRST ACT

SCENE

Morning-room in Algernon’s flat in Half-Moon Street. The room is luxuriously and artistically furnished. The sound of a piano is heard in the adjoining room.

[Lane is arranging afternoon tea on the table, and after the music has ceased, Algernon enters.]

ALGERNON.

Did you hear what I was playing, Lane?

LANE.

I didn’t think it polite to listen, sir.

ALGERNON.

I’m sorry for that, for your sake. I don’t play accurately—any one can play accurately—but I play with wonderful expression. As far as the piano is concerned, sentiment is my forte. I keep science for Life.

LANE.

Yes, sir.

ALGERNON.

And, speaking of the science of Life, have you got the cucumber sandwiches cut for Lady Bracknell?

LANE.

Yes, sir. [Hands them on a salver.]

ALGERNON.

[Inspects them, takes two, and sits down on the sofa.] Oh! . . . by the way, Lane, I see from your book that on Thursday night, when Lord Shoreman and Mr. Worthing were dining with me, eight bottles of champagne are entered as having been consumed.

LANE.

Yes, sir; eight bottles and a pint.

ALGERNON.

Why is it that at a bachelor’s establishment the servants invariably drink the champagne? I ask merely for information.

LANE.

I attribute it to the superior quality of the wine, sir. I have often observed that in married households the champagne is rarely of a first-rate brand.

ALGERNON.

Good heavens! Is marriage so demoralising as that?

LANE.

I believe it is a very pleasant state, sir. I have had very little experience of it myself up to the present. I have only been married once. That was in consequence of a misunderstanding between myself and a young person.

ALGERNON.

[Languidly.] I don’t know that I am much interested in your family life, Lane.

LANE.

No, sir; it is not a very interesting subject. I never think of it myself.

ALGERNON.

Very natural, I am sure. That will do, Lane, thank you.

LANE.

Thank you, sir. [Lane goes out.]

ALGERNON.

Lane’s views on marriage seem somewhat lax. Really, if the lower orders don’t set us a good example, what on earth is the use of them? They seem, as a class, to have absolutely no sense of moral responsibility.

[Enter Lane.]

LANE.

Mr. Ernest Worthing.

[Enter Jack.]

[Lane goes out.]

ALGERNON.

How are you, my dear Ernest? What brings you up to town?

JACK.

Oh, pleasure, pleasure! What else should bring one anywhere? Eating as usual, I see, Algy!

ALGERNON.

[Stiffly.] I believe it is customary in good society to take some slight refreshment at five o’clock. Where have you been since last Thursday?

JACK.

[Sitting down on the sofa.] In the country.

ALGERNON.

What on earth do you do there?

JACK.

[Pulling off his gloves.] When one is in town one amuses oneself. When one is in the country one amuses other people. It is excessively boring.

ALGERNON.

And who are the people you amuse?

JACK.

[Airily.] Oh, neighbours, neighbours.

ALGERNON.

Got nice neighbours in your part of Shropshire?

JACK.

Perfectly horrid! Never speak to one of them.

ALGERNON.

How immensely you must amuse them! [Goes over and takes sandwich.] By the way, Shropshire is your county, is it not?

JACK.

Eh? Shropshire? Yes, of course. Hallo! Why all these cups? Why cucumber sandwiches? Why such reckless extravagance in one so young? Who is coming to tea?

ALGERNON.

Oh! merely Aunt Augusta and Gwendolen.

JACK.

How perfectly delightful!

ALGERNON.

Yes, that is all very well; but I am afraid Aunt Augusta won’t quite approve of your being here.

JACK.

May I ask why?

ALGERNON.

My dear fellow, the way you flirt with Gwendolen is perfectly disgraceful. It is almost as bad as the way Gwendolen flirts with you.

JACK.

I am in love with Gwendolen. I have come up to town expressly to propose to her.

ALGERNON.

I thought you had come up for pleasure? . . . I call that business.

JACK.

How utterly unromantic you are!

ALGERNON.

I really don’t see anything romantic in proposing. It is very romantic to be in love. But there is nothing romantic about a definite proposal. Why, one may be accepted. One usually is, I believe. Then the excitement is all over. The very essence of romance is uncertainty. If ever I get married, I’ll certainly try to forget the fact.

JACK.

I have no doubt about that, dear Algy. The Divorce Court was specially invented for people whose memories are so curiously constituted.

ALGERNON.

Oh! there is no use speculating on that subject. Divorces are made in Heaven—[Jack puts out his hand to take a sandwich. Algernon at once interferes.] Please don’t touch the cucumber sandwiches. They are ordered specially for Aunt Augusta. [Takes one and eats it.]

JACK.

Well, you have been eating them all the time.

ALGERNON.

That is quite a different matter. She is my aunt. [Takes plate from below.] Have some bread and butter. The bread and butter is for Gwendolen. Gwendolen is devoted to bread and butter.

JACK.

[Advancing to table and helping himself.] And very good bread and butter it is too.

ALGERNON.

Well, my dear fellow, you need not eat as if you were going to eat it all. You behave as if you were married to her already. You are not married to her already, and I don’t think you ever will be.

JACK.

Why on earth do you say that?

ALGERNON.

Well, in the first place girls never marry the men they flirt with. Girls don’t think it right.

JACK.

Oh, that is nonsense!

ALGERNON.

It isn’t. It is a great truth. It accounts for the extraordinary number of bachelors that one sees all over the place. In the second place, I don’t give my consent.

JACK.

Your consent!

ALGERNON.

My dear fellow, Gwendolen is my first cousin. And before I allow you to marry her, you will have to clear up the whole question of Cecily. [Rings bell.]

JACK.

Cecily! What on earth do you mean? What do you mean, Algy, by Cecily! I don’t know any one of the name of Cecily.

[Enter Lane.]

ALGERNON.

Bring me that cigarette case Mr. Worthing left in the smoking-room the last time he dined here.

LANE.

Yes, sir. [Lane goes out.]

JACK.

Do you mean to say you have had my cigarette case all this time? I wish to goodness you had let me know. I have been writing frantic letters to Scotland Yard about it. I was very nearly offering a large reward.

ALGERNON.

Well, I wish you would offer one. I happen to be more than usually hard up.

JACK.

There is no good offering a large reward now that the thing is found.

[Enter Lane with the cigarette case on a salver. Algernon takes it at once. Lane goes out.]

ALGERNON.

I think that is rather mean of you, Ernest, I must say. [Opens case and examines it.] However, it makes no matter, for, now that I look at the inscription inside, I find that the thing isn’t yours after all.

JACK.

Of course it’s mine. [Moving to him.] You have seen me with it a hundred times, and you have no right whatsoever to read what is written inside. It is a very ungentlemanly thing to read a private cigarette case.

ALGERNON.

Oh! it is absurd to have a hard and fast rule about what one should read and what one shouldn’t. More than half of modern culture depends on what one shouldn’t read.

JACK.

I am quite aware of the fact, and I don’t propose to discuss modern culture. It isn’t the sort of thing one should talk of in private. I simply want my cigarette case back.

ALGERNON.

Yes; but this isn’t your cigarette case. This cigarette case is a present from some one of the name of Cecily, and you said you didn’t know any one of that name.

JACK.

Well, if you want to know, Cecily happens to be my aunt.

ALGERNON.

Your aunt!

JACK.

Yes. Charming old lady she is, too. Lives at Tunbridge Wells. Just give it back to me, Algy.

ALGERNON.

[Retreating to back of sofa.] But why does she call herself little Cecily if she is your aunt and lives at Tunbridge Wells? [Reading.] ‘From little Cecily with her fondest love.’

JACK.

[Moving to sofa and kneeling upon it.] My dear fellow, what on earth is there in that? Some aunts are tall, some aunts are not tall. That is a matter that surely an aunt may be allowed to decide for herself. You seem to think that every aunt should be exactly like your aunt! That is absurd! For Heaven’s sake give me back my cigarette case. [Follows Algernon round the room.]

ALGERNON.

Yes. But why does your aunt call you her uncle? ‘From little Cecily, with her fondest love to her dear Uncle Jack.’ There is no objection, I admit, to an aunt being a small aunt, but why an aunt, no matter what her size may be, should call her own nephew her uncle, I can’t quite make out. Besides, your name isn’t Jack at all; it is Ernest.

JACK.

It isn’t Ernest; it’s Jack.

ALGERNON.

You have always told me it was Ernest. I have introduced you to every one as Ernest. You answer to the name of Ernest. You look as if your name was Ernest. You are the most earnest-looking person I ever saw in my life. It is perfectly absurd your saying that your name isn’t Ernest. It’s on your cards. Here is one of them. [Taking it from case.] ‘Mr. Ernest Worthing, B. 4, The Albany.’ I’ll keep this as a proof that your name is Ernest if ever you attempt to deny it to me, or to Gwendolen, or to any one else. [Puts the card in his pocket.]

JACK.

Well, my name is Ernest in town and Jack in the country, and the cigarette case was given to me in the country.

ALGERNON.

Yes, but that does not account for the fact that your small Aunt Cecily, who lives at Tunbridge Wells, calls you her dear uncle. Come, old boy, you had much better have the thing out at once.

JACK.

My dear Algy, you talk exactly as if you were a dentist. It is very vulgar to talk like a dentist when one isn’t a dentist. It produces a false impression.

ALGERNON.

Well, that is exactly what dentists always do. Now, go on! Tell me the whole thing. I may mention that I have always suspected you of being a confirmed and secret Bunburyist; and I am quite sure of it now.

JACK.

Bunburyist? What on earth do you mean by a Bunburyist?

ALGERNON.

I’ll reveal to you the meaning of that incomparable expression as soon as you are kind enough to inform me why you are Ernest in town and Jack in the country.

JACK.

Well, produce my cigarette case first.

ALGERNON.

Here it is. [Hands cigarette case.] Now produce your explanation, and pray make it improbable. [Sits on sofa.]

JACK.

My dear fellow, there is nothing improbable about my explanation at all. In fact it’s perfectly ordinary. Old Mr. Thomas Cardew, who adopted me when I was a little boy, made me in his will guardian to his grand-daughter, Miss Cecily Cardew. Cecily, who addresses me as her uncle from motives of respect that you could not possibly appreciate, lives at my place in the country under the charge of her admirable governess, Miss Prism.

ALGERNON.

Where is that place in the country, by the way?

JACK.

That is nothing to you, dear boy. You are not going to be invited . . . I may tell you candidly that the place is not in Shropshire.

ALGERNON.

I suspected that, my dear fellow! I have Bunburyed all over Shropshire on two separate occasions. Now, go on. Why are you Ernest in town and Jack in the country?

JACK.

My dear Algy, I don’t know whether you will be able to understand my real motives. You are hardly serious enough. When one is placed in the position of guardian, one has to adopt a very high moral tone on all subjects. It’s one’s duty to do so. And as a high moral tone can hardly be said to conduce very much to either one’s health or one’s happiness, in order to get up to town I have always pretended to have a younger brother of the name of Ernest, who lives in the Albany, and gets into the most dreadful scrapes. That, my dear Algy, is the whole truth pure and simple.

ALGERNON.

The truth is rarely pure and never simple. Modern life would be very tedious if it were either, and modern literature a complete impossibility!

JACK.

That wouldn’t be at all a bad thing.

ALGERNON.

Literary criticism is not your forte, my dear fellow. Don’t try it. You should leave that to people who haven’t been at a University. They do it so well in the daily papers. What you really are is a Bunburyist. I was quite right in saying you were a Bunburyist. You are one of the most advanced Bunburyists I know.

JACK.

What on earth do you mean?

ALGERNON.

You have invented a very useful younger brother called Ernest, in order that you may be able to come up to town as often as you like. I have invented an invaluable permanent invalid called Bunbury, in order that I may be able to go down into the country whenever I choose. Bunbury is perfectly invaluable. If it wasn’t for Bunbury’s extraordinary bad health, for instance, I wouldn’t be able to dine with you at Willis’s to-night, for I have been really engaged to Aunt Augusta for more than a week.

JACK.

I haven’t asked you to dine with me anywhere to-night.

ALGERNON.

I know. You are absurdly careless about sending out invitations. It is very foolish of you. Nothing annoys people so much as not receiving invitations.

JACK.

You had much better dine with your Aunt Augusta.

ALGERNON.

I haven’t the smallest intention of doing anything of the kind. To begin with, I dined there on Monday, and once a week is quite enough to dine with one’s own relations. In the second place, whenever I do dine there I am always treated as a member of the family, and sent down with either no woman at all, or two. In the third place, I know perfectly well whom she will place me next to, to-night. She will place me next Mary Farquhar, who always flirts with her own husband across the dinner-table. That is not very pleasant. Indeed, it is not even decent . . . and that sort of thing is enormously on the increase. The amount of women in London who flirt with their own husbands is perfectly scandalous. It looks so bad. It is simply washing one’s clean linen in public. Besides, now that I know you to be a confirmed Bunburyist I naturally want to talk to you about Bunburying. I want to tell you the rules.

JACK.

I’m not a Bunburyist at all. If Gwendolen accepts me, I am going to kill my brother, indeed I think I’ll kill him in any case. Cecily is a little too much interested in him. It is rather a bore. So I am going to get rid of Ernest. And I strongly advise you to do the same with Mr. . . . with your invalid friend who has the absurd name.

ALGERNON.

Nothing will induce me to part with Bunbury, and if you ever get married, which seems to me extremely problematic, you will be very glad to know Bunbury. A man who marries without knowing Bunbury has a very tedious time of it.

JACK.

That is nonsense. If I marry a charming girl like Gwendolen, and she is the only girl I ever saw in my life that I would marry, I certainly won’t want to know Bunbury.

ALGERNON.

Then your wife will. You don’t seem to realise, that in married life three is company and two is none.

JACK.

[Sententiously.] That, my dear young friend, is the theory that the corrupt French Drama has been propounding for the last fifty years.

ALGERNON.

Yes; and that the happy English home has proved in half the time.

JACK.

For heaven’s sake, don’t try to be cynical. It’s perfectly easy to be cynical.

ALGERNON.

My dear fellow, it isn’t easy to be anything nowadays. There’s such a lot of beastly competition about. [The sound of an electric bell is heard.] Ah! that must be Aunt Augusta. Only relatives, or creditors, ever ring in that Wagnerian manner. Now, if I get her out of the way for ten minutes, so that you can have an opportunity for proposing to Gwendolen, may I dine with you to-night at Willis’s?

JACK.

I suppose so, if you want to.

ALGERNON.

Yes, but you must be serious about it. I hate people who are not serious about meals. It is so shallow of them.

[Enter Lane.]

LANE.

Lady Bracknell and Miss Fairfax.

[Algernon goes forward to meet them. Enter Lady Bracknell and Gwendolen.]

LADY BRACKNELL.

Good afternoon, dear Algernon, I hope you are behaving very well.

ALGERNON.

I’m feeling very well, Aunt Augusta.

LADY BRACKNELL.

That’s not quite the same thing. In fact the two things rarely go together. [Sees Jack and bows to him with icy coldness.]

ALGERNON.

[To Gwendolen.] Dear me, you are smart!

GWENDOLEN.

I am always smart! Am I not, Mr. Worthing?

JACK.

You’re quite perfect, Miss Fairfax.

GWENDOLEN.

Oh! I hope I am not that. It would leave no room for developments, and I intend to develop in many directions. [Gwendolen and Jack sit down together in the corner.]

LADY BRACKNELL.

I’m sorry if we are a little late, Algernon, but I was obliged to call on dear Lady Harbury. I hadn’t been there since her poor husband’s death. I never saw a woman so altered; she looks quite twenty years younger. And now I’ll have a cup of tea, and one of those nice cucumber sandwiches you promised me.

ALGERNON.

Certainly, Aunt Augusta. [Goes over to tea-table.]

LADY BRACKNELL.

Won’t you come and sit here, Gwendolen?

GWENDOLEN.

Thanks, mamma, I’m quite comfortable where I am.

ALGERNON.

[Picking up empty plate in horror.] Good heavens! Lane! Why are there no cucumber sandwiches? I ordered them specially.

LANE.

[Gravely.] There were no cucumbers in the market this morning, sir. I went down twice.

ALGERNON.

No cucumbers!

LANE.

No, sir. Not even for ready money.

ALGERNON.

That will do, Lane, thank you.

LANE.

Thank you, sir. [Goes out.]

ALGERNON.

I am greatly distressed, Aunt Augusta, about there being no cucumbers, not even for ready money.

LADY BRACKNELL.

It really makes no matter, Algernon. I had some crumpets with Lady Harbury, who seems to me to be living entirely for pleasure now.

ALGERNON.

I hear her hair has turned quite gold from grief.

LADY BRACKNELL.

It certainly has changed its colour. From what cause I, of course, cannot say. [Algernon crosses and hands tea.] Thank you. I’ve quite a treat for you to-night, Algernon. I am going to send you down with Mary Farquhar. She is such a nice woman, and so attentive to her husband. It’s delightful to watch them.

ALGERNON.

I am afraid, Aunt Augusta, I shall have to give up the pleasure of dining with you to-night after all.

LADY BRACKNELL.

[Frowning.] I hope not, Algernon. It would put my table completely out. Your uncle would have to dine upstairs. Fortunately he is accustomed to that.

ALGERNON.

It is a great bore, and, I need hardly say, a terrible disappointment to me, but the fact is I have just had a telegram to say that my poor friend Bunbury is very ill again. [Exchanges glances with Jack.] They seem to think I should be with him.

LADY BRACKNELL.

It is very strange. This Mr. Bunbury seems to suffer from curiously bad health.

ALGERNON.

Yes; poor Bunbury is a dreadful invalid.

LADY BRACKNELL.

Well, I must say, Algernon, that I think it is high time that Mr. Bunbury made up his mind whether he was going to live or to die. This shilly-shallying with the question is absurd. Nor do I in any way approve of the modern sympathy with invalids. I consider it morbid. Illness of any kind is hardly a thing to be encouraged in others. Health is the primary duty of life. I am always telling that to your poor uncle, but he never seems to take much notice . . . as far as any improvement in his ailment goes. I should be much obliged if you would ask Mr. Bunbury, from me, to be kind enough not to have a relapse on Saturday, for I rely on you to arrange my music for me. It is my last reception, and one wants something that will encourage conversation, particularly at the end of the season when every one has practically said whatever they had to say, which, in most cases, was probably not much.

ALGERNON.

I’ll speak to Bunbury, Aunt Augusta, if he is still conscious, and I think I can promise you he’ll be all right by Saturday. Of course the music is a great difficulty. You see, if one plays good music, people don’t listen, and if one plays bad music people don’t talk. But I’ll run over the programme I’ve drawn out, if you will kindly come into the next room for a moment.

LADY BRACKNELL.

Thank you, Algernon. It is very thoughtful of you. [Rising, and following Algernon.] I’m sure the programme will be delightful, after a few expurgations. French songs I cannot possibly allow. People always seem to think that they are improper, and either look shocked, which is vulgar, or laugh, which is worse. But German sounds a thoroughly respectable language, and indeed, I believe is so. Gwendolen, you will accompany me.

GWENDOLEN.

Certainly, mamma.

[Lady Bracknell and Algernon go into the music-room, Gwendolen remains behind.]

JACK.

Charming day it has been, Miss Fairfax.

GWENDOLEN.

Pray don’t talk to me about the weather, Mr. Worthing. Whenever people talk to me about the weather, I always feel quite certain that they mean something else. And that makes me so nervous.

JACK.

I do mean something else.

GWENDOLEN.

I thought so. In fact, I am never wrong.

JACK.

And I would like to be allowed to take advantage of Lady Bracknell’s temporary absence . . .

GWENDOLEN.

I would certainly advise you to do so. Mamma has a way of coming back suddenly into a room that I have often had to speak to her about.

JACK.

[Nervously.] Miss Fairfax, ever since I met you I have admired you more than any girl . . . I have ever met since . . . I met you.

GWENDOLEN.

Yes, I am quite well aware of the fact. And I often wish that in public, at any rate, you had been more demonstrative. For me you have always had an irresistible fascination. Even before I met you I was far from indifferent to you. [Jack looks at her in amazement.] We live, as I hope you know, Mr. Worthing, in an age of ideals. The fact is constantly mentioned in the more expensive monthly magazines, and has reached the provincial pulpits, I am told; and my ideal has always been to love some one of the name of Ernest. There is something in that name that inspires absolute confidence. The moment Algernon first mentioned to me that he had a friend called Ernest, I knew I was destined to love you.

JACK.

You really love me, Gwendolen?

GWENDOLEN.

Passionately!

JACK.

Darling! You don’t know how happy you’ve made me.

GWENDOLEN.

My own Ernest!

JACK.

But you don’t really mean to say that you couldn’t love me if my name wasn’t Ernest?

GWENDOLEN.

But your name is Ernest.

JACK.

Yes, I know it is. But supposing it was something else? Do you mean to say you couldn’t love me then?

GWENDOLEN.

[Glibly.] Ah! that is clearly a metaphysical speculation, and like most metaphysical speculations has very little reference at all to the actual facts of real life, as we know them.

JACK.

Personally, darling, to speak quite candidly, I don’t much care about the name of Ernest . . . I don’t think the name suits me at all.

GWENDOLEN.

It suits you perfectly. It is a divine name. It has a music of its own. It produces vibrations.

JACK.

Well, really, Gwendolen, I must say that I think there are lots of other much nicer names. I think Jack, for instance, a charming name.

GWENDOLEN.

Jack? . . . No, there is very little music in the name Jack, if any at all, indeed. It does not thrill. It produces absolutely no vibrations . . . I have known several Jacks, and they all, without exception, were more than usually plain. Besides, Jack is a notorious domesticity for John! And I pity any woman who is married to a man called John. She would probably never be allowed to know the entrancing pleasure of a single moment’s solitude. The only really safe name is Ernest.

JACK.

Gwendolen, I must get christened at once—I mean we must get married at once. There is no time to be lost.

GWENDOLEN.

Married, Mr. Worthing?

JACK.

[Astounded.] Well . . . surely. You know that I love you, and you led me to believe, Miss Fairfax, that you were not absolutely indifferent to me.

GWENDOLEN.

I adore you. But you haven’t proposed to me yet. Nothing has been said at all about marriage. The subject has not even been touched on.

JACK.

Well . . . may I propose to you now?

GWENDOLEN.

I think it would be an admirable opportunity. And to spare you any possible disappointment, Mr. Worthing, I think it only fair to tell you quite frankly before-hand that I am fully determined to accept you.

JACK.

Gwendolen!

GWENDOLEN.

Yes, Mr. Worthing, what have you got to say to me?

JACK.

You know what I have got to say to you.

GWENDOLEN.

Yes, but you don’t say it.

JACK.

Gwendolen, will you marry me? [Goes on his knees.]

GWENDOLEN.

Of course I will, darling. How long you have been about it! I am afraid you have had very little experience in how to propose.

JACK.

My own one, I have never loved any one in the world but you.

GWENDOLEN.

Yes, but men often propose for practice. I know my brother Gerald does. All my girl-friends tell me so. What wonderfully blue eyes you have, Ernest! They are quite, quite, blue. I hope you will always look at me just like that, especially when there are other people present. [Enter Lady Bracknell.]

LADY BRACKNELL.

Mr. Worthing! Rise, sir, from this semi-recumbent posture. It is most indecorous.

GWENDOLEN.

Mamma! [He tries to rise; she restrains him.] I must beg you to retire. This is no place for you. Besides, Mr. Worthing has not quite finished yet.

LADY BRACKNELL.

Finished what, may I ask?

GWENDOLEN.

I am engaged to Mr. Worthing, mamma. [They rise together.]

LADY BRACKNELL.

Pardon me, you are not engaged to any one. When you do become engaged to some one, I, or your father, should his health permit him, will inform you of the fact. An engagement should come on a young girl as a surprise, pleasant or unpleasant, as the case may be. It is hardly a matter that she could be allowed to arrange for herself . . . And now I have a few questions to put to you, Mr. Worthing. While I am making these inquiries, you, Gwendolen, will wait for me below in the carriage.

GWENDOLEN.

[Reproachfully.] Mamma!

LADY BRACKNELL.

In the carriage, Gwendolen! [Gwendolen goes to the door. She and Jack blow kisses to each other behind Lady Bracknell’s back. Lady Bracknell looks vaguely about as if she could not understand what the noise was. Finally turns round.] Gwendolen, the carriage!

GWENDOLEN.

Yes, mamma. [Goes out, looking back at Jack.]

LADY BRACKNELL.

[Sitting down.] You can take a seat, Mr. Worthing.

[Looks in her pocket for note-book and pencil.]

JACK.

Thank you, Lady Bracknell, I prefer standing.

LADY BRACKNELL.

[Pencil and note-book in hand.] I feel bound to tell you that you are not down on my list of eligible young men, although I have the same list as the dear Duchess of Bolton has. We work together, in fact. However, I am quite ready to enter your name, should your answers be what a really affectionate mother requires. Do you smoke?

JACK.

Well, yes, I must admit I smoke.

LADY BRACKNELL.

I am glad to hear it. A man should always have an occupation of some kind. There are far too many idle men in London as it is. How old are you?

JACK.

Twenty-nine.

LADY BRACKNELL.

A very good age to be married at. I have always been of opinion that a man who desires to get married should know either everything or nothing. Which do you know?

JACK.

[After some hesitation.] I know nothing, Lady Bracknell.

LADY BRACKNELL.

I am pleased to hear it. I do not approve of anything that tampers with natural ignorance. Ignorance is like a delicate exotic fruit; touch it and the bloom is gone. The whole theory of modern education is radically unsound. Fortunately in England, at any rate, education produces no effect whatsoever. If it did, it would prove a serious danger to the upper classes, and probably lead to acts of violence in Grosvenor Square. What is your income?

JACK.

Between seven and eight thousand a year.

LADY BRACKNELL.

[Makes a note in her book.] In land, or in investments?

JACK.

In investments, chiefly.

LADY BRACKNELL.

That is satisfactory. What between the duties expected of one during one’s lifetime, and the duties exacted from one after one’s death, land has ceased to be either a profit or a pleasure. It gives one position, and prevents one from keeping it up. That’s all that can be said about land.

JACK.

I have a country house with some land, of course, attached to it, about fifteen hundred acres, I believe; but I don’t depend on that for my real income. In fact, as far as I can make out, the poachers are the only people who make anything out of it.

LADY BRACKNELL.

A country house! How many bedrooms? Well, that point can be cleared up afterwards. You have a town house, I hope? A girl with a simple, unspoiled nature, like Gwendolen, could hardly be expected to reside in the country.

JACK.

Well, I own a house in Belgrave Square, but it is let by the year to Lady Bloxham. Of course, I can get it back whenever I like, at six months’ notice.

LADY BRACKNELL.

Lady Bloxham? I don’t know her.

JACK.

Oh, she goes about very little. She is a lady considerably advanced in years.

LADY BRACKNELL.

Ah, nowadays that is no guarantee of respectability of character. What number in Belgrave Square?

JACK.

149.

LADY BRACKNELL.

[Shaking her head.] The unfashionable side. I thought there was something. However, that could easily be altered.

JACK.

Do you mean the fashion, or the side?

LADY BRACKNELL.

[Sternly.] Both, if necessary, I presume. What are your politics?

JACK.

Well, I am afraid I really have none. I am a Liberal Unionist.

LADY BRACKNELL.

Oh, they count as Tories. They dine with us. Or come in the evening, at any rate. Now to minor matters. Are your parents living?

JACK.

I have lost both my parents.

LADY BRACKNELL.

To lose one parent, Mr. Worthing, may be regarded as a misfortune; to lose both looks like carelessness. Who was your father? He was evidently a man of some wealth. Was he born in what the Radical papers call the purple of commerce, or did he rise from the ranks of the aristocracy?

JACK.

I am afraid I really don’t know. The fact is, Lady Bracknell, I said I had lost my parents. It would be nearer the truth to say that my parents seem to have lost me . . . I don’t actually know who I am by birth. I was . . . well, I was found.

LADY BRACKNELL.

Found!

JACK.

The late Mr. Thomas Cardew, an old gentleman of a very charitable and kindly disposition, found me, and gave me the name of Worthing, because he happened to have a first-class ticket for Worthing in his pocket at the time. Worthing is a place in Sussex. It is a seaside resort.

LADY BRACKNELL.

Where did the charitable gentleman who had a first-class ticket for this seaside resort find you?

JACK.

[Gravely.] In a hand-bag.

LADY BRACKNELL.

A hand-bag?

JACK.

[Very seriously.] Yes, Lady Bracknell. I was in a hand-bag—a somewhat large, black leather hand-bag, with handles to it—an ordinary hand-bag in fact.

LADY BRACKNELL.

In what locality did this Mr. James, or Thomas, Cardew come across this ordinary hand-bag?

JACK.

In the cloak-room at Victoria Station. It was given to him in mistake for his own.

LADY BRACKNELL.

The cloak-room at Victoria Station?

JACK.

Yes. The Brighton line.

LADY BRACKNELL.

The line is immaterial. Mr. Worthing, I confess I feel somewhat bewildered by what you have just told me. To be born, or at any rate bred, in a hand-bag, whether it had handles or not, seems to me to display a contempt for the ordinary decencies of family life that reminds one of the worst excesses of the French Revolution. And I presume you know what that unfortunate movement led to? As for the particular locality in which the hand-bag was found, a cloak-room at a railway station might serve to conceal a social indiscretion—has probably, indeed, been used for that purpose before now—but it could hardly be regarded as an assured basis for a recognised position in good society.

JACK.

May I ask you then what you would advise me to do? I need hardly say I would do anything in the world to ensure Gwendolen’s happiness.

LADY BRACKNELL.

I would strongly advise you, Mr. Worthing, to try and acquire some relations as soon as possible, and to make a definite effort to produce at any rate one parent, of either sex, before the season is quite over.

JACK.

Well, I don’t see how I could possibly manage to do that. I can produce the hand-bag at any moment. It is in my dressing-room at home. I really think that should satisfy you, Lady Bracknell.

LADY BRACKNELL.

Me, sir! What has it to do with me? You can hardly imagine that I and Lord Bracknell would dream of allowing our only daughter—a girl brought up with the utmost care—to marry into a cloak-room, and form an alliance with a parcel? Good morning, Mr. Worthing!

[Lady Bracknell sweeps out in majestic indignation.]

JACK.

Good morning! [Algernon, from the other room, strikes up the Wedding March. Jack looks perfectly furious, and goes to the door.] For goodness’ sake don’t play that ghastly tune, Algy. How idiotic you are!

[The music stops and Algernon enters cheerily.]

ALGERNON.

Didn’t it go off all right, old boy? You don’t mean to say Gwendolen refused you? I know it is a way she has. She is always refusing people. I think it is most ill-natured of her.

JACK.

Oh, Gwendolen is as right as a trivet. As far as she is concerned, we are engaged. Her mother is perfectly unbearable. Never met such a Gorgon . . . I don’t really know what a Gorgon is like, but I am quite sure that Lady Bracknell is one. In any case, she is a monster, without being a myth, which is rather unfair . . . I beg your pardon, Algy, I suppose I shouldn’t talk about your own aunt in that way before you.

ALGERNON.

My dear boy, I love hearing my relations abused. It is the only thing that makes me put up with them at all. Relations are simply a tedious pack of people, who haven’t got the remotest knowledge of how to live, nor the smallest instinct about when to die.

JACK.

Oh, that is nonsense!

ALGERNON.

It isn’t!

JACK.

Well, I won’t argue about the matter. You always want to argue about things.

ALGERNON.

That is exactly what things were originally made for.

JACK.

Upon my word, if I thought that, I’d shoot myself . . . [A pause.] You don’t think there is any chance of Gwendolen becoming like her mother in about a hundred and fifty years, do you, Algy?

ALGERNON.

All women become like their mothers. That is their tragedy. No man does. That’s his.

JACK.

Is that clever?

ALGERNON.

It is perfectly phrased! and quite as true as any observation in civilised life should be.

JACK.

I am sick to death of cleverness. Everybody is clever nowadays. You can’t go anywhere without meeting clever people. The thing has become an absolute public nuisance. I wish to goodness we had a few fools left.

ALGERNON.

We have.

JACK.

I should extremely like to meet them. What do they talk about?

ALGERNON.

The fools? Oh! about the clever people, of course.

JACK.

What fools!

ALGERNON.

By the way, did you tell Gwendolen the truth about your being Ernest in town, and Jack in the country?

JACK.

[In a very patronising manner.] My dear fellow, the truth isn’t quite the sort of thing one tells to a nice, sweet, refined girl. What extraordinary ideas you have about the way to behave to a woman!

ALGERNON.

The only way to behave to a woman is to make love to her, if she is pretty, and to some one else, if she is plain.

JACK.

Oh, that is nonsense.

ALGERNON.

What about your brother? What about the profligate Ernest?

JACK.

Oh, before the end of the week I shall have got rid of him. I’ll say he died in Paris of apoplexy. Lots of people die of apoplexy, quite suddenly, don’t they?

ALGERNON.

Yes, but it’s hereditary, my dear fellow. It’s a sort of thing that runs in families. You had much better say a severe chill.

JACK.

You are sure a severe chill isn’t hereditary, or anything of that kind?

ALGERNON.

Of course it isn’t!

JACK.

Very well, then. My poor brother Ernest is carried off suddenly, in Paris, by a severe chill. That gets rid of him.

ALGERNON.

But I thought you said that . . . Miss Cardew was a little too much interested in your poor brother Ernest? Won’t she feel his loss a good deal?

JACK.

Oh, that is all right. Cecily is not a silly romantic girl, I am glad to say. She has got a capital appetite, goes long walks, and pays no attention at all to her lessons.

ALGERNON.

I would rather like to see Cecily.

JACK.

I will take very good care you never do. She is excessively pretty, and she is only just eighteen.

ALGERNON.

Have you told Gwendolen yet that you have an excessively pretty ward who is only just eighteen?

JACK.

Oh! one doesn’t blurt these things out to people. Cecily and Gwendolen are perfectly certain to be extremely great friends. I’ll bet you anything you like that half an hour after they have met, they will be calling each other sister.

ALGERNON.

Women only do that when they have called each other a lot of other things first. Now, my dear boy, if we want to get a good table at Willis’s, we really must go and dress. Do you know it is nearly seven?

JACK.

[Irritably.] Oh! It always is nearly seven.

ALGERNON.

Well, I’m hungry.

JACK.

I never knew you when you weren’t . . .

ALGERNON.

What shall we do after dinner? Go to a theatre?

JACK.

Oh no! I loathe listening.

ALGERNON.

Well, let us go to the Club?

JACK.

Oh, no! I hate talking.

ALGERNON.

Well, we might trot round to the Empire at ten?

JACK.

Oh, no! I can’t bear looking at things. It is so silly.

ALGERNON.

Well, what shall we do?

JACK.

Nothing!

ALGERNON.

It is awfully hard work doing nothing. However, I don’t mind hard work where there is no definite object of any kind.

[Enter Lane.]

LANE.

Miss Fairfax.

[Enter Gwendolen. Lane goes out.]

ALGERNON.

Gwendolen, upon my word!

GWENDOLEN.

Algy, kindly turn your back. I have something very particular to say to Mr. Worthing.

ALGERNON.

Really, Gwendolen, I don’t think I can allow this at all.

GWENDOLEN.

Algy, you always adopt a strictly immoral attitude towards life. You are not quite old enough to do that. [Algernon retires to the fireplace.]

JACK.

My own darling!

GWENDOLEN.

Ernest, we may never be married. From the expression on mamma’s face I fear we never shall. Few parents nowadays pay any regard to what their children say to them. The old-fashioned respect for the young is fast dying out. Whatever influence I ever had over mamma, I lost at the age of three. But although she may prevent us from becoming man and wife, and I may marry some one else, and marry often, nothing that she can possibly do can alter my eternal devotion to you.

JACK.

Dear Gwendolen!

GWENDOLEN.

The story of your romantic origin, as related to me by mamma, with unpleasing comments, has naturally stirred the deeper fibres of my nature. Your Christian name has an irresistible fascination. The simplicity of your character makes you exquisitely incomprehensible to me. Your town address at the Albany I have. What is your address in the country?

JACK.

The Manor House, Woolton, Hertfordshire.

[Algernon, who has been carefully listening, smiles to himself, and writes the address on his shirt-cuff. Then picks up the Railway Guide.]

GWENDOLEN.

There is a good postal service, I suppose? It may be necessary to do something desperate. That of course will require serious consideration. I will communicate with you daily.

JACK.

My own one!

GWENDOLEN.

How long do you remain in town?

JACK.

Till Monday.

GWENDOLEN.

Good! Algy, you may turn round now.

ALGERNON.

Thanks, I’ve turned round already.

GWENDOLEN.

You may also ring the bell.

JACK.

You will let me see you to your carriage, my own darling?

GWENDOLEN.

Certainly.

JACK.

[To Lane, who now enters.] I will see Miss Fairfax out.

LANE.

Yes, sir. [Jack and Gwendolen go off.]

[Lane presents several letters on a salver to Algernon. It is to be surmised that they are bills, as Algernon, after looking at the envelopes, tears them up.]

ALGERNON.

A glass of sherry, Lane.

LANE.

Yes, sir.

ALGERNON.

To-morrow, Lane, I’m going Bunburying.

LANE.

Yes, sir.

ALGERNON.

I shall probably not be back till Monday. You can put up my dress clothes, my smoking jacket, and all the Bunbury suits . . .

LANE.

Yes, sir. [Handing sherry.]

ALGERNON.

I hope to-morrow will be a fine day, Lane.

LANE.

It never is, sir.

ALGERNON.

Lane, you’re a perfect pessimist.

LANE.

I do my best to give satisfaction, sir.

[Enter Jack. Lane goes off.]

JACK.

There’s a sensible, intellectual girl! the only girl I ever cared for in my life. [Algernon is laughing immoderately.] What on earth are you so amused at?

ALGERNON.

Oh, I’m a little anxious about poor Bunbury, that is all.

JACK.

If you don’t take care, your friend Bunbury will get you into a serious scrape some day.

ALGERNON.

I love scrapes. They are the only things that are never serious.

JACK.

Oh, that’s nonsense, Algy. You never talk anything but nonsense.

ALGERNON.

Nobody ever does.

[Jack looks indignantly at him, and leaves the room. Algernon lights a cigarette, reads his shirt-cuff, and smiles.]

ACT DROP

1 note

·

View note

Quote

ALGERNON (airily): Oh! I killed Bunbury this afternoon. I mean poor Bunbury died this afternoon. LADY BRACKNELL: What did he die of? ALGERNON: Bunbury? Oh, he was quite exploded. LADY BRACKNELL: Exploded! Was he the victim of a revolutionary outrage? I was not aware that Mr Bunbury was interested in social legislation. If so, he is well punished for his morbidity. ALGERNON: My dear Aunt Augusta, I mean he was found out! The doctors found out that Bunbury could not live, that is what I mean - so Bunbury died. LADY BRACKNELL: He seems to have had great confidence in the opinion of his physicians. I am glad, however, that he made up his mind at the last to some definite course of action, and acted under proper medical advice.

The Importance of Being Earnest (Act III), Oscar Wilde (1895)

This fucking play 😂😂

#brilliant#the importance of being earnest#oscar wilde#algernon moncrieff#lady bracknell#quotes#literature

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

An Act Within an Act: The Importance of Being Earnest as key in reading Series 4

Alternatively: Deception in the Play that is Series 4 (The Importance of Being Earnest reading)

“The curtain rises. The last act. It’s not over. SH”

I’m going to discuss why this whole series 4 is just an act, such as there are different scenes to form a play. Some of the themes of The Importance of Being Earnest revolve around: duties/responsibilities, religion, morality, societal class, marriage, impressions, deception.

Let me just stress on two points here: deception (fake lives, fake people, and fake names) and impressions. Sound familiar? These motifs can also be found in series 4.

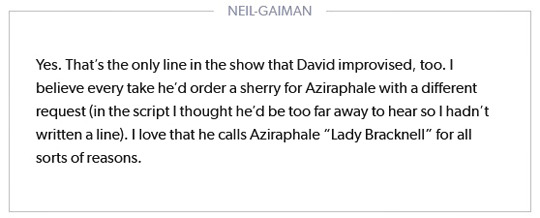

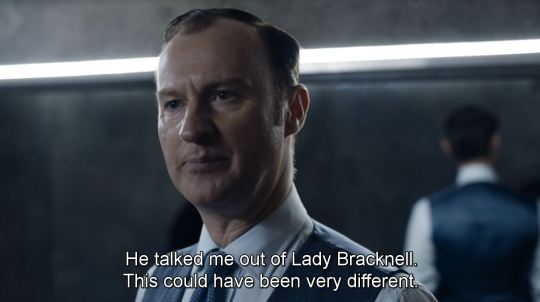

“Lady Bracknell” from Oscar Wilde’s play The Importance of Being Earnest (hereafter, TIOBE) was mentioned three times in The Final Problem. It was during these three instances:

1)

2)

3)

Thus, it is necessary to know the significance of TIOBE to this show.

[Note: I’ll discuss some important points in TIOBE first, then proceed to using these points in reading scenes from BBC Sherlock. After that, I’m going to draw parallels between the two plays (considering that Series 4 is a play) by discussing the twins, handbag, bunbury, acting, christening]

The Importance of Being Earnest

TIOBE has three acts. Brief summary first. (If you already know about TIOBE, you can skip this part) The first act is the introduction of the characters, where the “Bunburying” by both Jack/John Worthing and Algernon Moncrieff is revealed to us.

Bunburying = is an act, that comes from the word Bunbury, who is a poor, invalid friend of Algernon. Algernon made up Mr. Bunbury, to use as an excuse/alibi (that Algy needs to pay a visit his very ill friend) for him to avoid doing his duties.

In Algernon’s own words: “You have invented a very useful younger brother called Ernest, in order that you may be able to come up to town as often as you like. I have invented an invaluable permanent invalid called Bunbury, in order that I may be able to go down into the country whenever I choose. Bunbury is perfectly invaluable. If it wasn’t for Bunbury’s extraordinary bad health, for instance, I wouldn’t be able to dine with you at Willis’s to-night, for I have been really engaged to Aunt Augusta for more than a week.”

In the same way, Jack also does bunburying, but with Mr. Ernest Worthing

In town, Jack uses the name Ernest Worthing

In the countryside, Jack uses the name Jack but he has a brother named Ernest

The second act is Algy going to the countryside as he was curious about who Cecily was (the ward of Jack). Thus, to get into Jack’s place, Algy identifies as “Ernest Worthing” to everyone he meets in Jack’s place in the country. This causes a problem, of course, most especially since Jack also arrived during that same day to state that Ernest died because of illness, whereas Algy (dressed up as Ernest) was alive and well, and even inside the place.

The third act is both Cecily (supposedly engaged to “Ernest!Algy” and Gwendolen (supposedly engaged to “Ernest!Jack”) finding out that Jack and Algy were deceiving them with their names. You see, some of the themes of this play is about deception and impressions. The name “Ernest” is a great deal for the two girls, and if this isn’t Jack and Algy’s names, they are to decline the marriage. (Oh, and the views on marriage were also highlighted in this play)

Who is Lady Bracknell then? She is the mother of Gwendolen, and the aunt of Algy (in the end, it will also be found out that she is the aunt of Jack). Her attitude is VERY similar to Mycroft in various ways. (Btw, if you weren’t aware there are so many reasons why Algernon is a parallel for Sherlock and Jack/John for John, some of which are pointed out by @brilliantorinsane here.)

Thus, we read:

Lady Bracknell = Mycroft

Algernon Moncrieff = Sherlock

Jack/John Worthing = John

Points of similarity between Lady Bracknell and Mycroft:

1. She checks (interrogates) on Gwendolen’s potential partners

Lady Bracknell (pencil and notebook in hand): I feel bound to tell you that you are not down on my list of eligible young men, although I have the same list as the dear Duchess of Bolton has. We work together in fact. However, I am quite ready to enter your name, should your answers be what a really affectionate mother requires. Do you smoke?

Jack: Well yes, I must admit I smoke.

And this goes on. Anyway, it is comparable to this scene:

where Mycroft questions/tests John to get to know if he will be loyal to Sherlock.

M: Could it be that you’ve decided to trust Sherlock Holmes of all people?

JOHN: Who says I trust him?

M: You don’t seem the kind to make friends easily.

JOHN: Are we done?

M: You tell me.

M: I imagine people have already warned you to stay away from him, but I can see from your left hand that’s not going to happen.

Also:

Lady Bracknell: You can take a seat, Mr. Worthing

Jack: Thank you, Lady Bracknell, I prefer standing.

M: The leg must be hurting you. Sit down. JOHN: I don’t wanna sit down.

2. Lady Bracknell’s view on marriage/romance

Lady Bracknell: To speak frankly, I am not in favour of long engagements. They give people the opportunity of finding out each other’s character before marriage, which I think is never advisable.

MYCROFT: Well, it’s the end of an era, isn’t it? John and Mary – domestic bliss.

SHERLOCK: No, no, no – I prefer to think of it as the beginning of a new chapter.

SHERLOCK: What?

MYCROFT: Nothing!

SHERLOCK: I know that silence. What?

MYCROFT: Well, I’d better let you get back to it. You have a big speech, or something, don’t you?

SHERLOCK: What?

MYCROFT: Cake, karaoke ... mingling.

SHERLOCK: Mycroft!

MYCROFT: This is what people do, Sherlock – they get married. I warned you: don’t get involved.

SHERLOCK: Involved? I’m not involved.

3. Role of the mother (consequently, the grown-up):

Lady Bracknell is the mother of Gwendolen, and the Aunt of Algernon. She shows authority in the play. She cared for her daughter the most. Such can be found in these:

ASiB:

MYCROFT: I’ll be mother.

SHERLOCK: And there is a whole childhood in a nutshell.

ASiP:

TAB:

MYCROFT: Doctor Watson? Look after him ... please?

BBC SHERLOCK

The mention of Lady Bracknell three times may suggest that these are the three acts. The first act started after the explosion. See that the scene after the explosion at 221B is the pirate one. The explosion kick-started the play.

Okay, let’s dissect the dialogues. Replace the word “Lady Bracknell” in these dialogues to “act”. It totally fits in with the Play theory (where a brilliant meta on this was written by @porl0ck here, seriously, go read it if you haven’t):

FIRST *SUB-ACT:

MYCROFT: I’m sorry, Doctor Watson. Any movement will set off the grenade.

MYCROFT: I hope you understand.

JOHN: Oscar Wilde.

MYCROFT: What?

JOHN: He said, “The truth is rarely pure, and never simple.” It’s from ‘The Importance of Being Earnest.’ We did it in school.

WE WERE OFFICIALLY TOLD THAT “the truth is rarely pure and never simple” BEFORE THE ACT STARTED. It was the explosion that started the sub-act (*calling this a sub-act because TFP was the act within the bigger act (the whole of series 4).

(continuation)

MYCROFT: So did we. Now I recall. I was Lady Bracknell.

SHERLOCK: Yeah. You were great.

MYCROFT: You really think so?

SHERLOCK: Yes, I really do.

MYCROFT: Well, that’s good to know. I’ve always wondered.

SHERLOCK: Good luck, boys.

SHERLOCK: Three, two, one, go!

A nod to A PLAY by Oscar Wilde right before the “three, two, one, go!” and the explosion. The explosion in 221B signaled the start of the play.

Then,

We see this scene literally after the explosion. Two points:

1) No transition as to how we (or how Sherlock, John, and Mycroft) got to this part (specifically, in the British Isles: “RADIO: ... Lundy, Fastnet, Irish Sea, Shannon, Malin, Sherrinford. Sherrinford. Sherrinford.” - These are all islands in the British Isles, except Sherrinford).

2) Sherlock and John burst out of the window after the explosion and remained unscathed. No scratches. Anywhere. What a way to start the play.

SECOND SUB-ACT:

MYCROFT: It justifies dressing up or any damned thing I say it does. Now, listen to me: for your own physical safety do not speak, do not indulge in any non-verbal signals suggestive of internal thought. If the safety of my sister is compromised; if the security of my sister is compromised; if the incarceration of my sister is compromised – in short, if I find any indication my sister has left this island at any time, I swear to you, you will not.

MYCROFT: Say thank you to Doctor Watson.

GOVERNOR: Why?

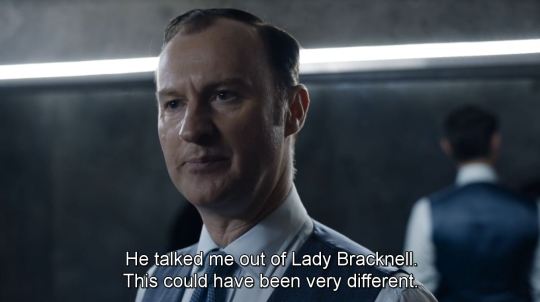

MYCROFT: He talked me out of Lady Bracknell. This could have been very different.

MYCROFT: Are you in?

SHERLOCK: Just arriving at the Secure Unit. Explain.

AUTOMATED VOICE: Door opening.

“It justifies dressing up or any damned thing I say it does” = C’mon Moftiss, you didn’t think we’d see through your costumes for your play? The narrative we’re given is the whole show dressed up in a costume for an act. Moftiss, I wonder: what would justify your cover-up/dressing that is this season?

“Say thank you to Doctor Watson” = John was our narrator for the last three seasons. We knew everything was real because the story was given to us from John’s perspective (or dare I say, eyes).

“He talked me out of Lady Bracknell. This could have been very different” = He talked me out of the act. It was John who guided us throughout the past seasons. JOHN has been our narrator. But Mycroft, this is ALL very peculiar, all very different… right, because we are shown an act.

“Are you in?” = Interestingly, in the second act, the “are you in?” question asked by Myrcroft to Sherlock could also mean another thing, other than Sherlock making his way to see Eurus. Mycroft (the showrunners), saying to Sherlock (the show BBC Sherlock) “Are you in?” = Are you in the act, are you joining the play? As is depicted, Sherlock continually enters. So he is in.

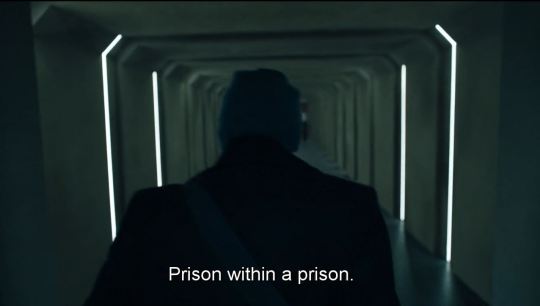

We also hear this while Sherlock makes his way towards Eurus’ cell:

An act, within an act. A narrative within a narrative. A dream within a dream. (However you may want to interpret it)

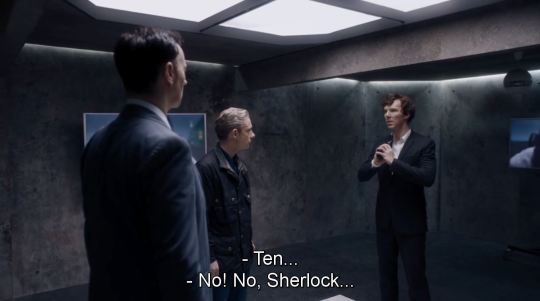

THIRD SUB-ACT:

SHERLOCK: Please, for God’s sake, just stop it.

MYCROFT: Why?

SHERLOCK: Because, on balance, even your Lady Bracknell was more convincing.

SHERLOCK: Ignore everything he just said. He’s being kind. He’s trying to make it easy for me to kill him.

Sherlock: “For God’s sake, just stop it (the act).”

“Even your Lady Bracknell ACT was more convincing” = Where was the act then? It had already been done at this point, as Sherlock wants to stop Mycroft in putting up the act. Mycroft, as we know can also signify Moftiss in this show, just as Sherlock can signify the show BBC Sherlock. Even the ACT was more convincing than the present one. What does this say? It means that there is an act within the act. An act within an act (series 4).

Sherlock to John (aka us, the audience): “Ignore everything he just said. He’s being kind. He’s trying to make it easy for me to kill him” = Funny, didn’t we just think that Moftiss tried to reichenbach this show? Mycroft (the showrunners and even Sherlock who’s in it) are putting up an act so that it would be easier to kill the show.

(continuation)

SHERLOCK: Which is why this is going to be so much harder. MYCROFT: You said you liked my Lady Bracknell.

JOHN: Sherlock. Don’t.

MYCROFT: It’s not your decision, Doctor Watson.

*****In case you haven’t noticed:*****

Mycroft = Moftiss

Sherlock = BBC Sherlock

John = Us

Dialogue:

Mycroft (bringing up the ACT again, right before he sacrificed himself to get shot): “You said you liked my Lady Bracknell act”

Mycroft (Moftiss): “It’s not your decision, Doctor Watson” = So, yeah, thanks Moftiss for telling us that we’re not actually in control of the situation.

Thus, three people in the room: (the showrunners, BBC Sherlock, and us)

Three people. Three characters.

Other Points of Similarity between TIOBE and BBC Sherlock:

1) Algy’s Mr. Bunbury

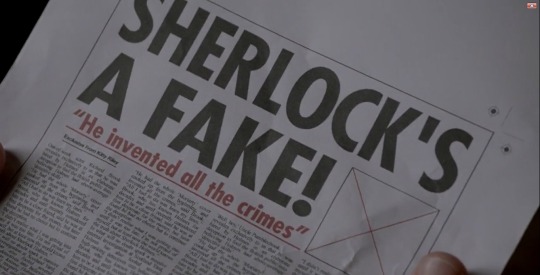

1.1) Richard Brook

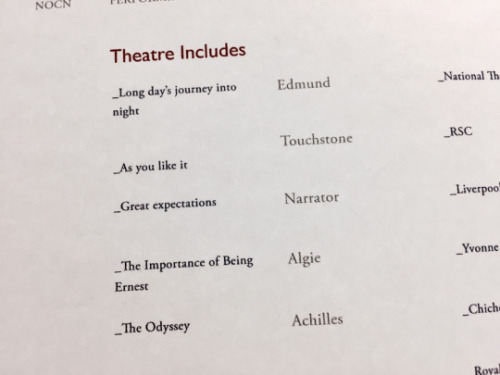

While Algernon represents Sherlock, we can also read Algy as being Jim Moriarty - Richard Brook as it is stated in his CV. (Found from Sherlock: The Casebook)

(photo from this post)

We know that Richard Brook is an actor, one which was invented by Jim to sell his story and prove to the world that it was Sherlock was mistaken all along.

KITTY: Of course he’s Richard Brook. There is no Moriarty. There never has been.

JOHN: What are you talking about? (Yeah, John is pretty much us. We were sold a lie, and us being clueless about it.)

JOHN: You read this stuff?

MYCROFT: Caught my eye.

MYCROFT: Saturday: they’re doing a big exposé.

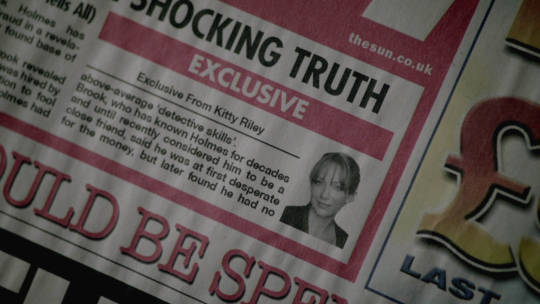

(John reads the announcement at the top of the front page. The headline reads: “SHERLOCK: THE SHOCKING TRUTH” with the strapline “Close Friend Richard Brook Tells All”. The article reveals that it is an Exclusive from Kitty Riley and the text reads: “Super-sleuth Sherlock Holmes has today been exposed as a fraud in a revelation that will shock his new found base of adoring fans. // Out-of-work actor Richard Brook revealed exclusively to THE SUN that he was hired by Holmes in an elaborate deception to fool the British public into believing Holmes had above-average ‘detective skills’. // Brook, who has known Holmes for decades and until recently considered him to be a close friend, said he was at first desperate for the money, but later found he had no” [at which point the text just stops].)

JOHN: I’d love to know where she got her information.

MYCROFT: Someone called Brook. Recognise the name?

Plus:

Rich Brook is the “Bunbury”, or the fake person invented by Jim to make his act/lie more believable and convincing. We are John, who’s feels entirely deceived about this all, as we know who Jim really is, thus, we cannot just make ourselves accept Rich Brook.

Sherlock’s line in TFP is to call out Mycroft to stop his acting.

TFP: “Please, for God’s sake, just stop it.”

We get it in TRF, when Jim Moriarty claimed to be Rich Brook.

TRF: “Stop it, stop it now!”

Similarly, we cannot be deceived by their act, as we know what the show Sherlock really is, and cannot just accept the Series 4, as it is. I mean, look at all their set-up, their costumes, their dialogue.

1.2) Series 4 Acting:

1.3) Helped by a media tycoon to set it all up?

1.4) The family pictures:

These are staged. These photos are not how family photos should be taken. More meta on this: 1 2 3

2) Handbag

There’s also this thing about the handbags.

Jack Worthing as a baby was found in a handbag in Victoria Railway station, in a cloak room. The handbag kept the baby in TIOBE. In Sherlock, handbags contained guns, as pointed out in this post.

Where’s the baby in Sherlock? (Allow me to play with concepts here. In TIOBE handbag --> baby. In Sherlock, handbag --> gun. What if the roles of the contents of the handbags remained the same?)

Mary naming the baby after her name “Rosamund” was like asking for danger waiting to happen. She’s well-aware of her past. Clearly, there are reasons behind it naming the baby after her “name”. Rosie may be used as a misdirection, or as a weapon by Mary. To the manipulator, everything can be used for utility. Most especially, a baby. As pointed out in others’ metas, Rosie is just a fake baby used as a weapon by Mary to achieve her own goals.

More clues leading that the baby is fake. Look no further, the promo pics are here to save the day. As Cecilia pointed out here and here:

So many wrong things in the promo pics.

3) Twins

In TIOBE, Dr. Chasuble, the rector, was requested by both Algy and Jack to christen them both, so that they would obtain the name “Ernest”. There was even a witty line (which mentioned “twins”) in the play, when Jack asked Chasuble to christen him.

Chasuble: In fact I have two similar ceremonies to perform at that time. A case of twins that occurred recently in one of the outlying cottages on your own estate. Poor Jenkins the carter, a most hard-working man.

Jack: Oh! I don’t see much fun in being christened along with other babies. It would be childish. Would half-past five do?

Chasuble: Admirably! Admirably! (Takes out watch) And now, dear Mr. Worthing, I will not intrude any longer into a house of sorrow. I would merely beg you not to be too much bowed down by grief. What seem to us bitter trials are often blessings in disguise.

The christening of the twins was never shown in the play (or more specifically in the book, as I read it), but this can also mean Algy and Jack, as they both wanted to be christened as “Ernest”.

Similarly, in the Abominable Bride, we have the concept of twins as well:

WATSON: Holmes, could it have been twins? HOLMES: No. WATSON: Why not? HOLMES: Because it’s never twins. LESTRADE: Emelia was not a twin, nor did she have any sisters. She had one older brother who died four years ago. WATSON: Maybe it was a secret twin. HOLMES: A what? WATSON: A secret twin? WATSON: Hmm? You know? A twin that nobody knows about? This whole thing could have been planned. HOLMES: Since the moment of conception? How breathtakingly prescient of her! It is never twins, Watson.

You see, the "secret twin” or anything “secret” (coughs /secret sister/) might’ve been intended for this Play (series 4) to work. Jack Worthing never got to know his biological parents as he says that he lost both his parents. (His backstory being a baby left in the cloakroom).

Jack: I said I had lost my parents. It would be nearer the truth to say that my parents seem to have lost me

By the end of the play, with the turnout of the events, it is revealed to us by the end of the play that Jack is indeed the elder brother of Algernon.

4) Killing of brother / friend

Lines in TIOBE (I cut some lines off): (Both Jack and Algy killed their brother/friend to continue with their lies about Ernest and Bunbury flawlessly).

---Jack---

Jack’s killing of his younger brother “Ernest:

Chasuble: Dear Mr. Worthing, I trust this garb of woe does not betoken some terrible calamity?

Jack: My brother.

Miss Prism: More shameful debts and extravagance?

Chasuble: Still leading his life of pleasure?

Jack: Dead!

Chasuble: Your brother Ernest dead?

Jack: Quite dead.

---Algy---

(Algy is continuing with his lie by making Bunbury appear dead at this point):

Algernon: Bunbury doesn’t live here. Bunbury is somewhere else at present. In fact, Bunbury is dead.

Lady Bracknell: Dead! When did Mr. Bunbury die?

Algernon: Oh! I killed Bunbury this afternoon. I mean poor Bunbury died this afternoon.

Lady Bracknell. What did he die of?

Algernon: Bunbury? Oh, he was quite exploded.

Lady Bracknell: Exploded! Was he the victim of a revolutionary outrage? I was not aware that Mr. Bunbury was interested in social legislation. If so, he is well punished for his morbidity.

Algernon: My dear Aunt Augusta, I mean he was found out! The doctors found out that Bunbury could not live, that is what I mean—so Bunbury died.

The death of a friend... I have seen it in TFP (as narrated by Eurus):

Anyway, my point here is that the “fake” people were killed by both Jack and Algy. There are still lots of discussions on Victor Trevor and Redbeard at the moment, but Eurus’ story tells us that Victor was killed and was replaced with Redbeard, the dog, in Sherlock’s memories. In TIOBE, Algy and Jack killed their fakes to continue with their lies. Might be the same for Sherlock.

5) Christening

Algy and Jack immediately wanted to be christened by the rector to obtain the name “Ernest”, since both Cecily and Gwendolen do not approve of the names “Algernon” and “Jack”, respectively. Thus, they request Chasuble to baptize them to .... continue with their faking? So that they can get away with their lies... For the women they love... Okay.

We went that far. That far to continue with Mary’s deceit.

In the end, we’re still trapped and watching the act:

The curtain rises. The last act. It’s not over. SH

Even more proof that this series 4 is an act, a lie. They told it to us many times before.

SHERLOCK: Everybody wants to believe it – that’s what makes it so clever. A lie that’s preferable to the truth. All my brilliant deductions were just a sham. No-one feels inadequate – Sherlock Holmes is just an ordinary man.

(They made the act pretty convincing, enough to convince some fans and the mainstream media that it’s ordinary, and not clever as we think it is.)

JOHN: Can he do that? Completely change his identity; make you the criminal? SHERLOCK: He’s got my whole life story. That’s what you do when you sell a big lie; you wrap it up in the truth to make it more palatable.

I would like to add that the Radio Times posted an article yesterday, April 10, with a quote that Moffat liked to write a PLAY.

Moffat: And I'd like to write a play because it would be so completely different. My main enthusiasm though is just to be at the beginning of something as opposed to well into it.

We see through your act.

Please, for God’s sake, just stop it.

Scripts from Ariane DeVere

Tagging some who might be interested (sorry if you don’t want to be tagged):

@a-reocurring-dream @inevitably-johnlocked @goodmythicalmail @worriesconstantly @the-7-percent-solution @monikakrasnorada @ebaeschnbliah @thepineapplering @teapotsubtext @jenna221b @waitedforgarridebs @sister-edgelord @kunstninja @jawnlock-is-real @love-in-mind-palace @mollydobby @tjlcisthenewsexy @graceebooks @ti-ori-se @bug-catcher-in-viridian-forest @teaandqueerbaiting @holmesianscholar @221bloodnun @artfulkindoforder @loveismyrevolution @bluebluenova @bakerstreetcrow @smoljohnlock @antisocial-otaku @welovethebeekeeper @ivyblossom @just-sort-of-happened @shag-me-senseless-watson @thepurplewombat @moriarty @marcelock @kinklock

#the importance of being earnest#my meta#meta#sherlock meta#series 4#tjlc#the johnlock conspiracy#johnlock#tfhc#tiobe#play#play theory#theory#act#oscar wilde#wilde#my post#bbc sherlock#sherlock#sherlock holmes#john watson#watson#bbc#moftiss#moffat#gatiss#mary is evil#mary#rosamund#name

275 notes

·

View notes

Text

THE IMPORTANCE OF BEING EARNEST

January 16, 2009

THE IMPORTANCE OF BEING EARNEST (subtitled A Serious Comedy for Trivial People) is a three act comedy of manners by Oscar Wilde. The story: Two wealthy young gentlemen have taken to bending the truth in order to put some excitement into their lives. Bachelor Jack Worthing has invented a brother, Ernest, who he uses as an excuse to leave his dull country life to visit the beautiful young Gwendolyn. Algernon Moncrieff decides to take the name Ernest when visiting Worthing's young and beautiful ward, Cecily. Things start to go awry when they all end up together in the country, and their deceptions are discovered by the persistent inquiries of the imperious Lady Bracknell.

It was first performed on Valentine's Day 1895 in London, England. The play was first performed in New York that same year, and has been seen on Broadway eight times since, the last being in 2011. The play has been seen on screens (big and small) many times, the most famous being in 1952 (starring Michael Redgrave, father of Lynn and Vanessa) and the most recent 2002 (starring Colin Firth). The play is in constant production in regional (see below), educational, and community venues.

THE IMPORTANCE OF BEING EARNEST was produced by New Jersey's Paper Mill Playhouse (Millburn) from January 14 to February 15, 2009. It was directed by David Schweizer with costumes by David Murin and scenery by Alexander Dodge. It starred John Wayne Wilcox (Jack), Jeffrey Carlson (Algernon), Keith Reddin (Rev. Chausuble), Chris Spencer Wells (Merriman / Oscar Wilde), Lynn Redgrave (Lady Bracknell), Annika Boras (Gwendolyn), Zoe Winters (Cecily), Cynthia Mace (Miss Prism), and Justin Bellero and Matthew Capodicasa as Footmen.

In the pantheon of English theatre, Hamlet is generally considered to be the finest tragedy ever written, and EARNEST the best comedy. The fact that both are in constant production is testament to those somewhat immeasurable assessments. Although Paper Mill Playhouse is not known for producing the 'classiscs' – this century old audience pleaser is one that entertains everyone and stands up to multiple viewings. This production added some wild(e) new elements, including the playwright himself observing the show from a theatre box, sipping champagne and (oddly) making the 'cell phone speech (”Whatever those are!”) The production eliminated one of the intermissions of the three-act, three-set comedy, forcing the set design Alexander Dodge to create a clever set that could entertainingly transform from London flat to Manor House Garden in front of the audiences eyes. It worked! The first act was monochrome, the second verdant greens, and the third reds and blacks. Wow! The costumes were pretty outrageous but had their logic and followed the color scheme of the scenery.