#arthur king of the britons

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Monty Python and the Holy Grail, 1975

Movie prop

Photographer: BelAirHead

#sir not appearing in this film#baby#sir lancelot the brave#john cleese#sir galahad#sir lancelot#sir galahad the pure#the book of the film#book#michael palin#graham chapman#arthur king of the britons#king arthur#monty python#1970s#prop#movie#film#reddit#belairhead#sir bedevere the wise#terry jones#michael palin's baby#keep thinking#keep reading#read banned books#eschew ai/chat gpt

130 notes

·

View notes

Text

*knocks on the door* does anyone take Monty Python and the Holy Grail?

I forgot my apple pencil at home and resorted to using my aquarel paint (that I got 8 years ago and never used) to draw King Arthur x Sir Bedevere. Do we call it duck shipping idk

I will probably make more, that movie has a surprising potential for Fandom but I can't find the fandom

#monty python#monty python and the holy grail#graham chapman#king arthur#arthur king of the britons#sir bedevere

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tags from @promithiae : "#*sits down with a microscope*ok were going to have a lecture on microbiology and what [a] virus is #no humors aren't a thing #no pus isn't a part of the healing proccess no a wound isn't "supposed” to do that oh my god #ok. now we're going to talk about vaccines and why you're getting stuck with about 15 needles #listen you dont want to catch a modern cold it's evolved too far from anything your immune system would be familiar with- #ok. evolution. right. so uuuuhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhh how comfortable are you with heresy"

hypothetical scenario for you all: the real king arthur returns. you meet him and you welcome him into your home. what is the first thing you do with him? keep in mind, this is a man from the 500s (he died in 542), and you are from the 21st century (2024).

28K notes

·

View notes

Text

It's time to determine by popular vote...

Who is the Hottest Arthur Pendragon?

Row 1 - Richard Harris, Camelot (1967) - Graham Chapman, Monty Python and the Holy Grail (1975)

Row 2 - Oliver Tobias, Arthur of the Britons (1972-73) - Nigel Terry, Excalibur (1981)

Row 3 - Sean Connery, First Knight (1995) - Alexandre Astier, Kaamelot (2004-2009)

Row 4 - Bradley James, BBC's Merlin (2008-2012) - Charlie Hunnam, King Arthur: Legend of the Sword (2017)

#exit polls#king arthur#arthur pendragon#richard harris#graham chapman#oliver tobias#nigel terry#sean connery#alexandre astier#bradley james#charlie hunnam#camelot 1967#monty python and the holy grail#arthur of the britons#excalibur 1981#first knight#kaamelott#bbc merlin#king arthur: legend of the sword#fuck that medieval man

274 notes

·

View notes

Text

RIP Clive Revill (18.4.1930 - 11.3.2025)

"It was quite an experience, and I had my doubts at one point when I thought, 'I can't do it. I can't do this. I can't find it within myself.' I had a marvelous talk with a woman who was, well, she was in charge of movement in school and she took me aside and said, 'You've got to go back to within yourself and find the truth within yourself, and if you can find that truth, never, never, never lose it because it's more than a ring on a finger. It's the absolute, innermost line within your life and your spirit.'"

#clive revill#rip#death ment tw#character actors#classic tv#the legend of hell house#avanti!#bunny lake is missing#the new avengers#columbo#modesty blaise#the assassination bureau#the private life of sherlock holmes#a severed head#jason king#murder she wrote#murder‚ she wrote#star trek: the next generation#star trek tng#star wars: the empire strikes back#the empire strikes back#charlie muffin#the black windmill#arthur of the britons#a New Zealander‚ Revell somehow avoided the fate of many of his countrymen (becoming a go to rentayank on British tv) and forged a#respectable stage career‚ including stints on Broadway and with the RSC. an almost ubiquitous face on genre tv‚ particularly in the US‚#Clive never really made it to 'star' status but graced many a popular series as well as appearing in some significant films. i usually look#for something to rec with these actors‚ something maybe a little less well known; I have to say The Legend of Hell House is a spectacular#brit horror that has slowly undergone reappraisal over the last decade or so. he also had notable (and fun!) roles on TNG as Guy of#Gisbourne (4.20‚ Qpid) and as the final murderer in the original run of Columbo (The Conspirators). just shy of 95 is a fine age tho. rip

106 notes

·

View notes

Text

Merlin the Prophet and Wizard

Merlin is one of those complicated tricksters characters I just can’t help but love. Like any character from the Arthurian Cycle, he’s an amalgamation of so many distinct ancient and slightly less ancient figures, mores, and cultural views. Whether he’s a mad half demon, a wise prophet, a wizard and the symbol of the dying druids, or a young magician in a bbc show, he’ll always have a hand in bringing the future to pass.

There are so many little fun wizard things in this piece potions, scrolls, a raven, feathers, a fire salamander, a mini lady in the lake bottle, nature inspired motifs for the Druid interpretation, a scarab beetles, some Celtic inspired checkered fabric, gilded illuminated manuscript edges, etc.

#merlin#excalibur#arthuriana#le morte d'arthur#medieval#mythology#myth#romantic#chivalry#tagamemnon#king arthur#morgan le fay#illustration#artists on tumblr#art#art tag#wizardposting#wizardblr#magic#Druid#Celtic#Briton#welsh#Excalibur (1981)#knights of the round table

23 notes

·

View notes

Photo

"'Tis but a scratch!"

Monty Python and the Holy Grail (1975, Terry Gilliam and Terry Jones)

#guillotined cinema#monty python#monty pyton and the holy grail#the black knight#arthur king of the Britons

132 notes

·

View notes

Text

KING ARTHUR (2004) set design appreciation: ― Hadrian's Wall: Arthur's quarters [2/?] inspired by @lady-arryn wonderful set design series [x]

KA20TH CELEBRATION | Day 4 - Home

AN: Here's part II of the Hadrian's Wall series for today's @ka20th prompt. This one was interesting because we never truly got to see Arthur in his own quarters. I know we had the scene where he slept with Guinevere but that was it. Wish we got to see more!

Also to anyone who's writing fics for this film, feel free to use this has visual inspiration if you're struggling with imagery or what-not💖 (P.S. This was probably one of the hardest things to gif, the colouring/lighting in those scenes are horrible 😭)

#king arthur#king arthur 2004#arthur#arthurian mythology#arthurian legend#artorius castus#clive owen#set design#set decoration#scenery#period drama#rome#briton#romans#medieval aesthetic#perioddramaedit#perioddramasource#perioddramagif#dailyflicks#cinemapix#cinamatv#filmedit#filmgifs#fyeahmovies#moviegifs#ka20th#fantasyedit#sceneryedit

56 notes

·

View notes

Text

My favorite arthurian tv shows and minisiers (part 1/2)

(My favorite movies here)

More details under cut. Some of these I love, some are so bad so good, some are beautifully epic, some are just funny.

The Adventures of Sir Galahad: Short one season tv show (15 episodes) about Galahad having to recover Excalibur after it was stolen. Also the one and only show where Galahad and Mordred interact.

The Adventures of Sir Lancelot: 30 episodes of self contained light and sometimes comedic adventures focusing on Lancelot living at Camelot. Still very much enjoyable today! Other characters who appear are Merlin, Arthur and Guinevere.

Arthur of the Britons: The first attempt to make a tv show focusing on Celts and a Celtic Arthur. Episodes are self contained. Kind of strange sometimes, and the only arthurian characters are Arthur, Kay and Ector.

The Legend of King Arthur: An 8 episodes BBC show which adapts Malory. This is the best arthurian tv show ever created! It also has an amazing Morgan and a stellar Mordred. Actually made me cry!

Entaku no Kishi Monogatari Moero Asa: Toei original anime (no manga) of 30 episodes that follow Arthur's journey to reclaim Camelot after it was conquered by a villain.

The Boy Merlin: Very short 6 episodes series about Merlin as a kid discovering his powers. It was very light and with an historical aesthetic.

Merlin: Two episodes miniseries, extremely popular! It follows Merlin from his childhood to the death of Arthur. While it is not my favorite, it has some great scenes in the second part where Guinevere, Mordred and Lancelot are introduced.

The Mists of Avalon: Miniseries adaptation of a novel I really dislike - but I love this miniseries. It might actually be one of my favorite arthurian series. It focuses on Morgana and her relationship with Arthur and Guinevere. It also has an amazing Mordred and Morgause, one of the rare times where we see Morgause.

#the mists of avalon#the legend of king arthur#the adventures of sir lancelot#merlin#the adventures of sir galahad#merlin 1998#mists of avalon#the boy merlin#king arthur anime#arthur of the britons#fav tv#fav arthurian media

50 notes

·

View notes

Note

🔥 hot takes on anything Arthuriana related

btw love your welsh legal history posts

Oh, hello!!!! I love ur blog so like hi, hi, hi!!! Ahh, thank u for saying u like the legal posts!! They're super fun to do so I'm glad you've enjoyed them!!!!! :D sleep deprived but okay, hot takes.

Purely Welsh myth but Arthur should've left Bendigeidfran's head where it was. Like bruh, you brought the misery upon yourself. Plus, I don't think I've seen a lot of lit exploring this aspect of the myth but I think it would be fun cuz it shows Arthur as being hubristic which does get glossed over I think.

Also, Geraint needs to be chucked off a cliff. I volunteer to do it.

And I don't think Guinevere / Gwenhwyfar was ever a goddess. There's nothing to suggest she was at all. That's silly. That's stupid.

Also, authors stop using Bedwyr for the Lancelot stand-in when u don't want to put him in. EDERN IS RIGHT THERE.

(This isn't a hot take but I have many bugbears either Marion Zimmer Bradley and have a deep, deep dislike for her work. She's just ehdjxjcjx)

Also, this is a Welsh myth thing but I guess I'm putting it in because Arthur does have Welsh gods in his retinue and has his roots in Welsh things but can we stop using Gwydion as a good guy, pls? He is a Bad, Bad man.

Also, Arthur was never a real person but a lot of the lads who got folded into the mythos are and that gets overlooked because we all want this king to be super fuckin real and for what? I think if we'd had evidence for a real Arthur then we'd have gotten it by now.

Also somebody pls write me a book about real irl cousins urien and peredur / percival. I need it like I need air.

#i... am sleep deprived so i apologise if this is a rambly and b v welsh heavy#none of these are hot takes i fear so i am sorry#not saying the welsh mythos is the best mythos or that arthur being real is somehow bad#it would be nice if he was but i think people forget that myths are myths and that much of the reason why the kings wanted arthur to be real#was so they could legitimise their rule over the narive britons cuz they were norman#it made sense in a way to have this dyde who'd united the britons under one banner so tthey could say they were following in his footsteps#so colonialism plays a part i think. like we can't forget that. the normans built on the mythos to cement their power#but like the stories ate alsi banging so like uvvvu#arthuriana#welsh mythology#the mabinogion#mabinogion#arthurian legend#arthurian myth#arthurian mythology#arthurian legends#arthurian#king arthur#i am sleep deprived im so sorry!!!!#salomania 🩷

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kay & Arthur - The Last One by Maisie Peters

#flash warning#sir kay#king arthur#arthur of the britons#excalibur 1981#starz camelot#my one true love

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

this morning i started writing a thorki au and it has already committed the following sins: modern au; thor & loki not being related; blue-collar thor while loki is posh. but i don't care because the whole concept is stupid and tailored to my very specific demands and there is as ever a good chance i will never make any real progress on it anyway. ha ha. ha haha. so there.

#okay so listen: thor is electrician BUT he is also somehow arthur king of the britons#and i have no yet worked out the mythical/magical elements work into the story really BUT#thor being the magic rightful king is V AWKWARD for loki the current king of the danelaw#(MODERN DANELAW AU YES! HYPERSPECIFIC DEMANDS!)#and so OBVIOUSLY this means they will have to get married to each other to prevent things getting too interesting plotwise.#so here i am attempting to justify my choices in this matter of writing rom-com fic.#i think frigga will love thor because he can fix things. he has a real skill! wow she doesn't know anyone else with such a thing!#probably she breaks things just so she can ask him to fix them for her. which sounds dangerous but who can say no to frigga?#i think my train of thought was 'modern au but they'd have to be from a fictional european country' to 'extra scandinavia?'#eta: and then i thought maybe it could be set in modern vinland because why not?#and from there to 'oh the danelaw!' and then that adds king arthur of course as well as there can be an archbishop of jorvik.#which is sure to charm the anglicans at least.#note to self: check if anglicans read thorki fic.#yes i know there should probably not be a church of england in this world but i am weirdly attached to having an archbishop of jorvik.#because who else can perform the wedding ceremony?#exactly my friend. exactly. this does indeed all make perfect sense.#i have about 1500 words but the worldbuildng in my head is oddly extensive for someone whose usual 'worldbuilding' in fics stops at#'well he has a car and it's some kind of car but i won't specify beyond that because i neither know nor care about cars.'#maybe heimdall can be the archbishop?#fic related#this fic would have the stupidest pun-based title of all time but i have not yet had any inspiration for what that would actually be.#also fun fact: i cannot spell archbishop i keep trying to add an extra vowel.#someone please agree that this is not the worst fic idea.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Martin Jarvis as Karn in Arthur of the Britons 2.1 "The Swordsman" (HTV, 1973)

#arthur of the britons#gif#martin jarvis#karn#king arthur#oliver tobias#1970s#period drama#film serials#swords#sword fighting#celts#duels#my gifs#technology is being even more obstreperous than usual but i managed to gif some of this at least

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Good morning, everyone! Get ready for a ☆*: .。. o Tragedy o .。.:*☆

S02E09 — The Lady of the Lake

Merlin saves a Druid girl from a bounty hunter's cage, but there is more to her than meets the eye.

#bbc merlin#merlin rewatch 2023#bbc merlin s02e09#freylin#obligatory shoutout to Cabin Pressure! “My name is Arthur!” “King of the Britons?” “Steward of the Aeroplane.”

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

New Banner Feature:

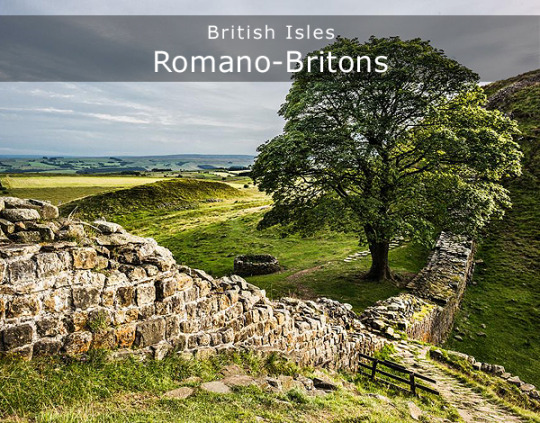

Post-Roman Britain: the post-Roman period in Britain was one of gradual social collapse in the face of unstoppable invasion, with a series of small states or kingdoms emerging and falling in the space of two centuries.

#history#historyfiles#post-roman#post-roman britain#britain#Romano-Britons#Romano-British#Anglo-Saxon#invasion#migration#migrants#kingdoms#king arthur#ambrosius aurelianus#vortigern

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

‘The Burial at the Giants’ Ring’ - Geoffrey of Monmouth’s Historia Regum Britanniae.

Like his brother Ambrosius, Uthr (anglicised as Uther) met his death after being poisoned, and both were buried within the Giants’ Ring near Salisbury. Geoffrey of Monmouth describes the removal of a ring of stones from Mount Killaraus in Ireland that had been placed there by giants to Salisbury to memorialise a massacre of Britons. Constantine, the king who follows Arthur after he is taken to Avalon after Camlann, was also buried here upon his death. I’ve only chosen to represent Ambrosius and Uthr here as I wanted to focus more on it as a location during what would have been Arthur’s lifetime. The editor of Geoffrey’s text, Lewis Thorpe, also notes that it is likely that Geoffrey could have been confusing Stonehenge and another stone circle at Avebury nearby, but I’ve chosen to use Stonehenge here.

I’ve always found him to be a complicated individual in the Welsh tradition as a modern person reading it. In Geoffrey’s depiction, he is both an incredibly successful warrior, it is prophesied that his son will have a great empire and his daughter’s descendants will retain the kingship of Britain, and he is the father of the greatest Welsh hero. But it is this last point which becomes a difficult part - his love for Arthur’s mother, Eigr (Ygerna or Igraine), and his decision and methodology when acting on it are, to a modern audience, quite obscene. He, with the help of Myrddin (Merlin), disguises himself as her husband, Gorlois, and they sleep together, conceiving Arthur that same night.

I think modern interpretations often follow this track of him being a complex (but generally quite a bad) person. In almost all the literature, he is heavily overshadowed by his son - my rather destroyed and heavily referenced copy of Geoffrey’s text sums his kingship up in around 9 pages. Although it wasn’t necessarily a long reign, it pales in comparison to the time given to Arthur, who takes up around 50 pages, around 20% of the text. Mentions of his beyond the Welsh tradition also leave out perhaps one of the coolest things about Uthr which is his ability to potentially shape-shift. The shapeshifting he does in Geoffrey’s text is magically induced by Merlin, but recent scholarship (including my own current research!) suggests that this is a run off from Uthr’s supernatural powers in other texts. The Trioedd Ynys Prydein records that Uthr taught a ‘great enchantment’ to Menw ap Teirgwaedd, likely the shapeshifting he performs in Culhwch ac Olwen when travelling to Esgair Oerfel. I would love to see this sort of stuff included in depictions of him, especially as they’re so absent in the English and Continental traditions!

Anyway, continuing with my inability to complete any artwork within the time limit given, this is again based on @mortiscausa ‘s #marchtocamelot, instead on the theme of ‘family’. Yet another information dump to go with it, but Lord knows doing two degrees in the subject means you have a lot to say in the long run!

#march to camelot#arthurian literature#arthurian legend#arthuriana#arthurian mythology#medieval#geoffrey of monmouth#historia regum britanniae#king arthur

74 notes

·

View notes