#another random character art

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

I like her glasses

#yeah#another random character art#cause#tbh i just wanted to draw something cause i was feeling so :((#this was fun to draw#my art#artists on tumblr#oc art#???#somewhat#ummmm yea no more tags what else is there to tag 😭#honestlyyyyy her outfit aint all that tf was i doing

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

It's canon. Trust me.

#mello's drawings#Teen!Crewel#twisted wonderland#twst#dire crowley#divus crewel#mozus trein#random background character coz I couldn't be bothered#my art#for some reason Tumblr put the tags of another post on this one wtf happened?

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

ok so @casycloud090 pointed out this random fucking frame in Trolls World Tour and i went insane and had to draw this mystery bull man-- i made the executive decision to name him Buffalo Billy cause i am CRINGE and FUNNY and he is an OUTLAW COUNTRY TROLL!!! (they have bull features instead of horse features brrr) tysm casy for showing me this im obsessed with him now

#buffalo billy save me buffalo billy#whats this? another random 3 second of screentime character to ship john dory with?#he has riff vibes ik#trolls#trolls world tourr#trolls band together#buffalo billy trolls#yep im makign a hashtag for it cause im definitely drawing him again#hickory trolls#john dory trolls#hickdory#hickdory trolls#buffalodory#buffalodory trolls#im getting secondhand embarrassment typing these#my art

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

ive seen a couple pokemon character color wheels around so i tried one with some of my favorites!

#not ALL my favorites I had to do a bit of switching around with some to fit the right colors hehe#halfway through drawing this i stopped and filled out an entire tier list of all the pokemon characters#brawly is just a silly guy what can i say#i dunno why ive always liked him! even though hes just a random gym leader#i wanted to include iris but leon's the king of purple so i had to put him there#oooh know what ill do another one w the girls!#weve got leaf may iris roxie... ill have to think of who else i like too#pokemon#pokemon art#color wheel challenge#aqua leader archie#magma leader maxie#blue oak#green oak#pokemon red#trainer red#rival blue#champion leon#pokemon leon#pokemon allister#gym leader allister#gym leader brawly#pokemon brawly#pokemon n#natural harmonia gropius#i will never be over the fact that that’s his name#reguri#originalshipping#hardenshipping#my art

833 notes

·

View notes

Text

I think they would get along great, don't you? Here is today's little doodle, featuring Wind and what I think Ariel might look like if she was in LU! It was fun to change her design a bit...perhaps I will do one of these with each of the LU boys...

#linkeduniverse#linked universe#princess ariel#digital art#myart#another one in the series of drawing random characters in the LU style!#i literally sped through the background#this was so fun#i think i might have to do all of them now!#lu wind#squid...octopus...same thing lol#both have tentacles and both are scary if giant and attacking you#click image for better quality!#crossovers#disney princess x lu

305 notes

·

View notes

Text

they're a killer queeeeen

#jrwi riptide#jrwi queen#my art#sketch#i love queen so much but like. WHAT IS UP WITH THEM????? WHO IS THAT????#why did some random person gill picked up in the bar turn out to be so swag and look like the main character of the story???#huh wuh?#they literally look like someone from another plain of existence. wdym that's a random bard you keep on the ship?#and what's up with them and that violin person from the last ep??? why did no one say anything. huh???????#literally WHAT is happening with queen i have so many questions

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

smile! you're on camera :)

#rin#oc#original character#my art#my ocs#horror#wanted to draw something creepy idk#been running with drawing whatever cool idea pops into my head so#another random art for you guys lol#cursed polaroid/old horror movie look?? did i slay

333 notes

·

View notes

Text

Was feeling blue today

There was a strong itch to use blue on something and they were the first two characters that came into mind hahaha..

#my art#steven universe#i dont rly go here anymore but the characters were pretty#sorry for the random ass content yall#i have been jumping from one thing to another these days#nothing is motivating or inspiring🫠#and i feel like i am rotting in my own mind#might delete?? idk we’ll see if i dont hate it by tomorrow#su#blue diamond#lapis lazuli

681 notes

·

View notes

Text

Amber from Rune Factory 4!

#my art#artwork#fanart#rune factory#rf4 amber#rune factory 4#i had another friend pick a random character from the wiki#and they picked amber because of fairy vibes#which is kinda close ig#i enjoyed this drawing a lot tho!!#learned some good coloring stuffs

160 notes

·

View notes

Text

I know I forgot something just can’t tell what… also more mixed feelings lol

Edit: THE THING I FORGOT WAS THAT I SCRATCHED THE LOVE TRIANGLE THING OMFG

Previous——Next

#Just Another Day Au#F!Yuichi#F!Mikey#F!Draxum#rottmnt oc#it’s fun drawing random characters#hehehehhe#digital#digital drawing#digital art#digital doodle#doodles#doodle#drawing sketch#sketch#oc#comic#future rottmnt au#rottmnt#rise of the tmnt#rottmnt fanart#tmnt#unpause rottmnt#save rottmnt

486 notes

·

View notes

Text

Doodle~ 🫧✨

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Do you ever wonder why it rains?"

#Guess who's getting into another gacha?#also I am just a little obsessed#just a little#Random character: *has anything to do with rain*#Me: I'll die for you#I'm not predictable at all shut up >:(#helps that I'm learning russian rn so I practice by translating his dialogue#is playing gacha secretly an academic endeavor?🤔🤔🤔#His dialogue for entering a team is “Can I.. not?” which is so funny to me#like me too#the amount of tags is getting out of hand#anyways#reverse 1999#re1999#зима#зима reverse 1999#zima reverse 1999#fanart#reverse 1999 fanart#my art

196 notes

·

View notes

Text

I don’t remember what I have and have not posted on here in a while— so here’s some concepts of Selena becoming a werewolf I might use for the comic if I ever am able to get around to it. :3

#castlevania#castlevania games#castlevania simon’s quest#castlevania selena#selena belmont#simon belmont#I’m thinking of having the wolf boss from Chronicles be another woman from town that also got captured#im probs gonna have Selena’s side of the story have a lot more dialogue and such since she meets and interacts with a lot more people#that also allows me to flesh out random bosses and background skeletons as characters cause yippie!!!!!! :3#she’ll likely be trying to work with everyone to escape#not everyone does and Simon isn’t able to stop for everyone it’s a whole thing idk I have ideas anyway—#somehow the lady is turned into a werewolf and tragically ends up jeopardizing the escape party then Simon ends up having to fight her#and Selena doesn’t realize she’s been scratched or bit until wayyyy too late#aughgghgg I have ideas#art post#my art#akumajou dracula#akumajo dracula#simon’s quest#simon belmont comic#I should make a better tag for this tbh cause it’s not all Simon hmmm#CV1-2 comic#yeah sure that works for now :3

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

@mothbutcher heyy😔 I meant to post this on Pixilart for you, but the stupid system recognized the drawing as something inappropriate when it wasn’t at all. HAPPY BIRTHDAY THO🎊🎊🎊🎂 (made on magma w/ the others).

#The last two drawings you see were attempts to get past the error#as you can tell from the hands#but it didnt work and I got another error saying i wasnt allowed to post another photo for 1-3 hours#Pixilart is shit like that😭😭#so!! here it is on tumblr#i hope you like em#I just picked two random fellas#But they are beautiful fellas!!#art#artwork#drawing#my art#my art work#my artwork#my drawing#digital art#magma.com#artist on tumblr#character art#not my characters#not my ocs#not my oc#line art#lineart#chibi#digital drawing#digital artwork

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

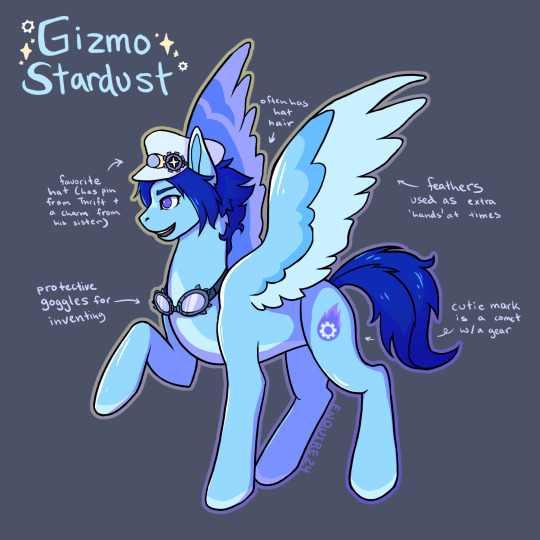

Gizmo Stardust!

Okay... it's Yamato's time to shine. I'm pretty happy with him! He was fun to draw and pretty easy to pick colors for... I do think maybe he could use a gear bag, or a vest, or something of that nature. I've been trying to only add accessories or clothing when it serves a purpose, so waffling a bit on that here... oh well. Maybe later.

Gizmo Stardust is a prolific inventor who lives in Canterlot with his father and sister. He's also heir to his dad's company, Stardust Industries, which recently became a lot more successful thanks to his inventions. Gizmo's hoofwork is present in many of the technological advancements in Canterlot and beyond.

One example (that brought Stardust Industries to where it is now) was Gizmo's most well-known creation; the airship. The introduction of a new form of flight to Equestria revolutionized the transportation and shipping industries. The airships Gizmo designed elegantly mesh together the mechanisms behind Equestria's balloons and trains, but require very little fuel thanks to sails which function in much the same way as pegasi wings.

Gizmo's also has a family friend, Thrift Twinkle, who he and his sister have known since they were little, thanks to their fathers being friends as well as business partners. Thrift and Gizmo are still pretty close, thanks to being friends when they were foals, and the fact that they got their cutie marks practically together.

This happened while Gizmo and Thrift were working together to save their respective family businesses. It was Thrift's business savvy and creativity which kept them from going under, and Gizmo's invention of the airship which brought both of their companies flying back into success again. Thrift helped Gizmo's inventions get off the ground, and worked to keep him funded until he finally completed his work.

Naturally then, the rebranded 'Phoenix Goods' was the first company to support and benefit from Stardust Industries' latest and greatest invention. And so, they managed not only to save their parents' crumbling businesses, but rocket them into unprecedented new highs.

It was during this process, through creating and helping each other, that both Gizmo and Thrift got their cutie marks. And more than proved their mettle to their parents at the same time. Both of them were overjoyed (and a little relieved, because they were blank flanks a little longer than most, and far longer than Gizmo's sister was)

When the two of them were younger, Gizmo had cheered on his sister when she got her cutie mark. When he got his, she responded in kind, throwing him a huge party and inviting practically everypony she knew to celebrate. It was during this bombastic party that Gizmo met Saber Frost.

He stumbled across him while taking a break from the chaos out on the balcony, where Saber had spent most of the night away from the light and revelry inside. Surprised to find somepony he didn't know awkwardly standing on the outskirts of the gathering with nothing but a glass of punch and a stony look on his face, he struck up a conversation. They hit it off, and Gizmo convinced the other not to leave the party, instead inviting him to join the two siblings for a quiet walk after the celebration concluded.

They may live far apart, but that doesn't stop them from seeing each other pretty often. For one thing, Thrift has reason to visit Canterlot on company business fairly frequently. And whenever he does, he makes sure to set aside time for the trio to hang out.

It was on one such visit that Gizmo introduced Thrift to Saber. They didn't click at first, but Gizmo and his sister, as usual, brought their friends together without too much trouble. Since then, three became four whenever Thrift was in Canterlot.

And when Saber was reassigned, Gizmo helped encourage him to request the region of Equestria where Thrift lived. Knowing his friend would be there to look out for Saber made him a lot less worried. Even though Gizmo knew it was for the best that Saber left Canterlot (and in fact had been trying to encourage and persuade Saber to accept the reassignment for a long time) he still misses their weekly chats over coffee and tea.

I love that I have enough ponies done to start weaving their stories together now. Also here's what he looks like without the hat or goggles:

#enquire's dra ponies#enquire art#danganronpa another#dra1 fanart#mlp art#dra1#mlp fim#mlp crossover#my little pony#yamato kisaragi#mlp fanart#mlp g4#mlp#danganronpa another despair academy#danganronpa fangan#crossover au#fangan character#fanganronpa#wow I didn't realize how much I actually had for his character blurb nice#the temptation to make everyone a unicorn is real but this one loses his horn privileges too#being a pegasi suits him more#i can't give all the creative or smarty pants horns or like half of them would be unicorns ok#note: airships are in MLP yes they're real#i think they debuted in the film iirc#this AU is tied to MLP G4 lore btw#that might be a bit dubious at times though to be fair#shout out to whenever I figure out how hard to go on Saber's backstory and whether or not I will go beyond the tone/rules of the show....#I think he carries a saddle bag things like wrenches and sketchpads and random parts at times#bonus thrift twinkle lore and tiny smidge for Saber Frost

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

Old art of mine I found while looking through my procreate gallery

#doctorsiren#siren’s oc#cookie run#latte cookie#digital art#my art#procreate#old art#first drawing is Idun (?)#like the apple goddess#second is humaonid-ish Enid (one of my enderman OCs)#third is a humanoid-ish version of her brother Easton#fourth are two random characters I made up for that drawing#fifth is another random dude#and 6th is latte cookie (that drawing is the oldest one of the bunch)#it’s also unfinished but I really like it#OUGH WAIT I SHOULD DRAW MIA AS LATTE COOKIE AND DIEGO AS ALMOND COOKIE perhaps hehehehe

67 notes

·

View notes