#and yet the eucatastrophe of lord of the rings

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

I’m sure I’ve said it before but to me the two greatest modern works are: lord of the rings, brideshead revisited.

#or if not two of the greatest! I am limited in my reading#but there’s something about each of them where they are the blueprint for this age because they are OF this age (relatively speaking.)#(in the grand scheme of things and history)#lord of the rings because everything is in decay and there IS no hope#brideshead because every interpersonal relationship has failed#and everything is so hideously ugly#and yet the eucatastrophe of lord of the rings#and the ending of brideshead#where every interpersonal dynamic remains unhealed#Charles can’t save Sebastian#he doesn’t get Julia. it all has so truthfully fallen apart#and yet the light in the sanctuary lamp still burns!!!!!!#it makes me !!!! want to throw up!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!#(sorry for being graphic)#I just

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

LOTR Newsletter - October 11

The hobbits and Aragorn are walking in the direction of the Bridge of Mitheithel across the Hoarwell River:

Four days passed, without the ground or scene changing much, except that behind them Weathertop slowly sank, and before them the distant mountains loomed a little nearer. Yet since that far cry they had seen and heard no sign that the enemy had marked their flight or followed them. They dreaded the dark hours, and kept watch in pairs by night, expecting at any time to see black shapes stalking in the grey light, dimly lit by the cloud-veiled moon; but they say nothing, and heard no sound but the sigh of withered leaves and grass. Not once did they feel the sense of present evil that had assailed them before the attack in the dell. It seemed too much to hope that the Riders had lost their trail again. Perhaps they were waiting to make some ambush in a narrow place? At the end of the fifth day the ground began once more to rise slowly out of the wide shallow valley into which they had descended.

In fact their worries have been accurate: there have been three Ringwraiths lying in wait on the Bridge of Mitheithel, as it is a choke point: there is no other way to cross the river nearby.

However, today is also when Glorfindel drives those Ringwraiths off the Bridge of Mitheithel, which is what enables the Fellowship to cross the bridge safely in a couple days. From Glorfindel's account to the hobbits and Aragorn when he meets them:

“It was my lot to take the Road, and I came to the Bridge of Mitheithel and left a token there, nigh on seven days ago. Three of the servants of Sauron were upon the Bridge, but they withdrew and I pursued them westward. I also came upon two others, but they turned away southward.”

This is an example of a kind of occurrence that I see several times in The Lord of the Rings, and not very much in other fantasy literature. It's the literal opposite of the trope of "characters think everything will be fine, but then it goes horribly wrong". Instead, this one is "the characters are dreading something bad ahead of them, see all the signs that something bad is ahead of them...and instead, everything is fine." Actually fine, not a fake-out! The biggest one in LOTR is when Aragorn, Legolas, Gimli and the Rohirrim are on the way to Isengard - they see the Isen dried up, they see steam/smoke/fog rising from Isengard, they expect that Saruman's got something dangerous up his sleeve, and then it turns out that, surprise! he's already been defeated. It's not quite eucatastrophe to me, because to me eucatastrophe is when things have already gone bad and seem hopeless, and then a miraculous salvation appears. This is more a case of "that thing that you thought was a problem you'd have to face? it's not actually a problem, I fixed it for you".

Most epic fantasy authors don't seem to go in for it, because a climax is more exciting than an anticlimax, and having all the major crises faced simultaneously (I'm looking at you, Brandon Sanderlanche 😂) is more dramatic than the heroes showing up to find that one of the crises has already been resolved for them.

And I love it because it's a reminder that the story isn't all hanging on one person; that the characters don't have to do everything, they only have to do their part; that you've got other people in your corner. It's the epic fantasy equivalent of a day when I went into work dreading having to spend a few weeks figuring out some very complicated coding, only to find that a colleague (who is much better at coding than me) had already done it all, and I could get started on the stuff I was good at.

61 notes

·

View notes

Note

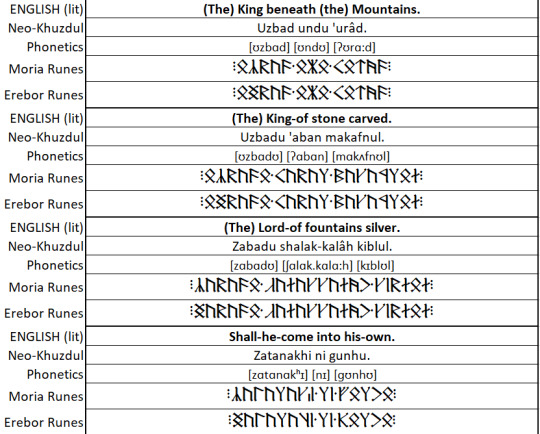

Hey if you get a chance, would you mind translating the poem, The King Beneath The Mountains, into Khuzdul? I couldn't find any pre-existing translations yet so I figured I'd ask. No pressue! :)

Well met — and what a worthy request!

The poem you’re referring to, The King Beneath the Mountains, is one of the most iconic lyrical pieces in The Hobbit, originally sung by the people of Lake-town upon the arrival of Thorin and Company. It serves both as a prophecy and an underlying eulogy of sorts for the fallen glory of Erebor, steeped in hope and longing for restoration.

For completeness, let’s begin with the canonical version as printed in The Hobbit:

The King beneath the mountains, The King of carven stone, The lord of silver fountains Shall come into his own! His crown shall be upholden, His harp shall be restrung, His halls shall echo golden To songs of yore re-sung. The woods shall wave on mountains And grass beneath the sun; His wealth shall flow in fountains And the rivers golden run. The streams shall run in gladness, The lakes shall shine and burn, All sorrow fail and sadness At the Mountain-king's return!

Erebor as seen in The Hobbit movies

🔍 A Closer Look at the Stanza’s Meaning

Though short, each stanza of The King Beneath the Mountains carries layers of meaning—particularly when viewed through a Dwarven lens.

Stanza 1 paints a vision of restoration and rightful return. The King (Thorin—metaphorically echoing Durin reborn) is not merely of noble blood, but one whose return has long been prophesied. “Carven stone” and “silver fountains” invoke Erebor’s history, artistry, and abundance. “Shall come into his own” suggests destiny reclaiming its rightful place.

Stanza 2 shifts to symbols of rulership and culture: a crown upheld, a harp restrung—not just the return of power, but the revival of song, heritage, and ancestral memory. “Songs of yore re-sung” places Dwarven tradition at the centre of this rebirth.

Stanza 3 brings nature into harmony with the returning king. Trees, grass, rivers—all flourish. His wealth isn’t static gold in vaults, but flowing, like life itself. It envisions a world where prosperity is shared and visible, not hoarded (somewhat un-Dwarven, even). The very land surrounding Erebor responds—almost as a character in its own right—to the King’s return.

Stanza 4 culminates in joy and healing. Water glows, sorrow fails. It’s both elegy and eucatastrophe: the scars of exile and ruin are—at long last—undone with the return of the King. It suggests not just political restoration, but also emotional and cultural renewal, completing the poem’s arc from loss to wholeness.

🎥 Film Adaptation Notes Peter Jackson’s adaptation takes some liberty with the wording. The first and fourth stanzas are rearranged and subtly altered, transforming a hopeful prophecy into a more ominous foretelling — Bard recalls the lines during a moment of dread rather than celebration:

The lord of silver fountains The King of carven stone, The King beneath the mountains Shall come into his own. And the bells shall ring in gladness At the Mountain-king’s return! But all shall fail in sadness And the lake will shine and burn.

Scene from ''The Hobbit: The Desolation of Smaug''

Additionally, there’s a short outburst in the book (as Thorin appears), where the townsfolk exclaim:

“The King beneath the mountain!” they shouted. “His wealth is like the Sun, His silver like a fountain, His rivers golden run!”

These lines suggest the poem may be longer than what’s printed—or that additional stanzas were remembered or passed down in Lake-town’s oral tradition. 📜 About the Translation

Translating it into Neo-Khuzdul is no small feat — you’ll find the first stanza fully rendered in Neo-Khuzdul, phonetics, and both Moria and Erebor runes in the image below:

That said, I’ll be honest: translating the entire poem faithfully isn’t something I can commit to right now, for a few reasons.

🪓 Firstly, it’s a sizeable task. A direct, literal translation is relatively straightforward (as you see above), but that quickly becomes... clunky. These lines rhyme and flow beautifully in English — but when directly translated into Neo-Khuzdul, they lose their rhythm, structure, and sometimes even their emotional punch.

🪓 Secondly, and mainly, doing it properly would mean much more than just translating. It would require completely reconstructing the poem: choosing rhyming pairs, finding suitable metaphors, adjusting for stress and meter, and generally composing something that sounds and feels like a Dwarvish song/poem — not just an English translation.

That’s a task I’d genuinely love to undertake… when time allows. But as it stands, to do it justice (and I wouldn't dream of taking shortcuts here), it would take several weeks of iteration, editing and testing. So, one of these days...

Still, I hope this first stanza brings a bit of Khuzdul flair to your fanfic, project, or inspiration corner.

Ever at your service, The Dwarrow Scholar

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

"But the 'consolation' of fairy-stories has another aspect than the imaginative satisfaction of ancient desires. Far more important is the Consolation of the Happy Ending. Almost I would venture to assert that all complete fairy-stories must have it. At least I would say that Tragedy is the true form of Drama, its highest function; but the opposite is true of Fairy-story. Since we do not appear to possess a word that expresses this opposite – I will call it Eucatastrophe. The eucatastrophic tale is the true form of fairy-tale, and its highest function.

The consolation of fairy-stories, the joy of the happy ending: or more correctly of the good catastrophe, the sudden joyous 'turn' (for there is no true end to any fairy-tale): this joy, which is one of the things which fairy-stories can produce supremely well, is not essentially 'escapist', nor 'fugitive'. In its fairy-tale – or otherworld – setting, it is a sudden and miraculous grace: never to be counted on to recur. It does not deny the existence of dyscatastrophe, of sorrow and failure: the possibility of these is necessary to the joy of deliverance; it denies (in the face of much evidence, if you will) universal final defeat and in so far is evangelium, giving a fleeting glimpse of Joy, Joy beyond the walls of the world, poignant as grief.

It is the mark of a good fairy-story, of the higher or more complete kind, that however wild its events, however fantastic or terrible the adventures, it can give to child or man that hears it, when the 'turn' comes, a catch of the breath, a beat and lifting of the heart, near to (or indeed accompanied by) tears, as keen as that given by any form of literary art, and having a peculiar quality."

-

'Angst with a happy ending' tag is Tolkien approved!

(He had already finished The Hobbit at this point, and had started Lord of the Rings. Gollum wresting the ring from a reluctant Frodo is a eucatastrophe that he had yet to write; the arrival of the eagles during the Battle of the Five Armies was one he must have had on his mind as a eucatastrophic ending when giving this lecture initially in 1939, two years after The Hobbit's publication.)

Reading Tree and Leaf for Tolkien Reading Day and am already giggling at the note on why he included imagery of trees at the start of Mythopoeia.

"Trees are chosen because they are at once easily classifiable and innumerably individual; but as this may be said of other things, then I will say, because I notice them more than most other things (far more than people)."

We know, Jirt. You like trees, Jirt <3

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Eucatastrophe isn't just a nice little plot device in The Lord of the Rings. It isn't just a nod to his worldview. It's absolutely vital to the specific story Tolkien's telling.

The Ring's main temptation is that it offers control. It offers you enough power to defeat all your enemies, to make sure the story ends the way you want. The heroes have to avoid that temptation at every turn, because taking up that power would make them no better than the villain. They have to move forward against impossible odds, knowing that they don't have the power to win, yet hoping that somehow, there's some greater power that will turn the story in their favor.

That's why the enemy's main weapon is despair. He tries to keep their eyes on the logical possibilities of this world, try to make them believe there's no hope of outside help, to think the only things they can rely on are their own power or his own dominance. If the heroes lose hope, they'll either submit to his power, or be tempted to take up power that will still make them slaves to the Dark Lord. Only with that hope can they withstand him.

It's not just hope that Tolkien's heroes need--it's hope unlooked-for. When, based on the knowledge they have and the resources they hold, they can't see any hope of success, they have to move forward in anticipation of a hope that they can't see. A hope that goes beyond the bounds of what they can logically expect. A hope in something greater than the petty powers of this world, in a power that can't be wielded but can only be trusted to turn all things toward a greater good.

And that hope is not in vain. The Dark Lord, for all his pride, all his grasping for power, is still bounded by the limitations of this world. He can't hope to overcome powers from outside the world. His plans can be foiled by a change in the wind, by the arrival of unexpected allies, by a withered, grasping creature taking one wrong step at the edge of a volcano, by air support that shows up at the last minute to save the heroes from death. These turns of fortune aren't just convenient escapes for the heroes--they directly tie to the theme at the heart of the work. In the context of the main conflict of the story, a eucatastrophe is the only way it could end.

#lord of the rings#tolkien#the return of the king#this has probably been said a thousand times but it just struck me yesterday#i knew it was central to the worldview but i hadn't quite grasped how central it was to the plot and themes

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

I recognise Walt Disney’s talent but it has always seemed to me hopelessly corrupted. Though in most of the pictures proceeding from [Disney] studios there are admirable or charming passages, the effect of all of them to me is disgusting. Some have given me nausea.

J.R.R. Tolkien

If Disney turned his stomach we can assume Tolkien would be turning in his grave at what Amazon Studios have done with 'Rings of Power'.

Tolkien's main objection to Disney - and something shared with C.S. Lewis - was how childish Disney treated fairy tales. For Tolkien fairy tales were serious business.

At the crux of his argument, which explores the nature of fantasy and the cultural role of fairy tales, is the same profound conviction that there is no such thing as writing “for children.” Tolkien insists that fairy tales aren’t inherently “for” children but that we, as adults, simply decided that they were, based on a series of misconceptions about both the nature of this literature and the nature of children. Tolkien deeply believe in language, myth, and Fairy, in that he recognised, they are deeply human things. Indeed, it is a natural right of humanity to produce fantasy.

And ye fail completely when we believe that Fairy is for children, Tolkien argued, noting that traditionally Fairy deals with the most difficult human problems, and children - understood as yet-to-be-formed humans - fall into the category of human, but they have no special hold or understanding of Fairy. Tolkien argued that the path to Fairy is neither the path to heaven nor to hell. It might be somewhat purgatorial, however, and certainly otherworldly. Fairy itself, far from being supernatural, is the most natural of worlds. Indeed, it is extraordinarily natural, as natural things live only as themselves. Rather Platonically, the tree is truly the tree (Treebeard), wine is truly wine, and bread (Lembas) is truly bread in Fairy. That is, there is little if any separation of the accidents of a thing from the essence of a thing. Those in fairy, though, through pride of beauty, often present themselves in disguise and as things they are not, thus befuddling the wanderer.

Words, definitions, and analyses, Tolkien warned, can offer only so much understanding of Fairy. Instead, one must not only travel to and through Fairy, but he must also recognise that fairy - like all mythology - is an expression of our deepest longings and fears.

A genuine fantasy, according to Tolkien, creates an immersive experience for the reader. In a successful fantasy, the author is a ‘sub-creator’: as Tolkien puts it, “He makes a Secondary World which your mind can enter. Inside it, what he relates is ‘true’: it accords with the laws of that world. You therefore believe it, while you are, as it were, inside.”

He goes on to argue that this sort of fantasy has three essential functions: recovery, escape, and consolation. Using the metaphor of a dirty, smudged window - whose film of grime obscures what we see through it - he says that we need “to clean our windows; so that the things seen clearly may be freed from the drab blur of triteness or familiarity - from possessiveness.” Fantasy helps us with this recovery of clear vision. He distinguishes the literary escape offered by good fantasy from the negative quality of escapism. And he explains the idea of consolation by coining the word eucatastrophe. It is formed of ‘eu,’ meaning good, attached to ‘catastrophe, and it means “the good catastrophe”: the unexpected happy ending, which gives us a profound taste of joy. We see it in The Lord of the Rings with the rescue of Frodo and Sam, after the destruction of the Ring, when they are sure that all is lost; we see it even more fully in the final chapters and indeed the final pages of the tale.

#tolkien#jrr tolkien#quote#lord of the rings#books#disney#walt disnery#fairy tales#animation#stiry telling

416 notes

·

View notes

Text

Happy Eucatastrophe!

“Stern now was Eomer's mood, and his mind clear again. He let blow the horns to rally all men to his banner that could come thither; for he thought to make a great shield-wall at the last, and stand, and fight there on foot till all fell, and do deeds of song on the fields of Pelennor, though no man should be left in the West to remember the last King of the Mark.

So he rode to a green hillock and there set his banner, and the White Horse ran rippling in the wind.

Out of doubt, out of dark to the day's rising I came singing in the sun, sword unsheathing.

To hope's end I rode and to heart's breaking:

Now for wrath, now for ruin and a red nightfall!

These staves he spoke, yet he laughed as he said them. For once more lust of battle was on him; and he was still unscathed, and he was young, and he was king: the lord of a fell people. And lo! even as he laughed at despair he looked out again on the black ships, and he lifted up his sword to defy them.

And then wonder took him, and a great joy; and he cast his sword up in the sunlight and sang as he caught it. And all eyes followed his gaze, and behold! upon the foremost ship a great standard broke, and the wind displayed it as she turned towards the Harlond.

There flowered a White Tree, and that was for Gondor; but Seven Stars were about it, and a high crown above it, the signs of Elendil that no lord had borne for years beyond count. And the stars flamed in the sunlight, for they were wrought of gems by Arwen daughter of Elrond; and the crown was bright in the morning, for it was wrought of mithril and gold.

Thus came Aragorn son of Arathorn, Elessar, Isildur's heir, out of the Paths of the Dead, borne upon a wind from the Sea to the kingdom of Gondor; and the mirth of the Rohirrim was a torrent of laughter and a flashing of swords, and the joy and wonder of the City was a music of trumpets and a ringing of bells.

But the hosts of Mordor were seized with bewilderment, and a great wizardry it seemed to them that their own ships should be filled with their foes; and a black dread fell on them, knowing that the tides of fate had turned against them and their doom was at hand.” -The Battle of Pelennor Fields, The Return of the King by J. R.R. Tolkien

Eucatastrophe: a neologism coined by Tolkien from Greek ευ- "good" and καταστροφή "sudden turn". In essence, a eucatastrophe is a massive turn in fortune from a seemingly unconquerable situation to an unforseen victory, usually brought by grace rather than heroic effort.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Meeting Mr. Tollers (or, an autobiographical argument for meeting writers on their own terms)

The first time I read The Lord of the Rings, I didn’t like it at all.

I didn’t read anything by Tolkien until my junior year of high school, actually. Although my parents read to me every night in elementary school and I’ve been a voracious reader of heavy tomes ever since, I managed to avoid it largely because none of my family or friends were fans. (In fact, my dad listened to Fellowship on tape once, didn’t like any of the poetry, and got pretty mad when he reached the end of tape ten or so and realized there were two more books.)

I decided to read LOTR for two reasons: 1) a teacher joked that she would “take away my Nerd Card” if I didn’t and 2) I knew that Tolkien and Lewis were good friends. And given that I’ve had Once there were four children whose names were Peter, Susan, Edmund, and Lucy emblazoned on my bones since first grade, that was a pretty big selling point.

Yet it was that second point that ruined my first experience with Tolkien. I mean, most of the major barriers to entry were non-issues for me. I liked the writing style. I didn’t have trouble with the names. I thought the poetry was hit-and-miss, but it didn’t certainly didn’t bother me. But LOTR wasn’t Narnia, and for that I faulted it.

I don’t mean that I wanted a lighter tone or anything like that. Rather, I went in expecting Aslan and got Gandalf. I liked Aragorn, but I kept trying to force him to be Peter. I wanted spiritual highs (“Tell me your sorrows” “Courage, dear heart”) and Biblical parallels (wait… is Gandalf supposed to be Jesus or not? What Biblical figure or idea does Gollum represent?) I picked through it with a fine-tooth comb as I read, and when I finished, I threw it aside thinking, what a disappointment.

But then I started college and made friends with several enormous Tolkien fans. “Have you read The Silmarillion?” they asked.

“I didn’t even particularly like LOTR,” I replied.

They asked me why. When I told them, they told me how much Tolkien hated allegory and encouraged me to try again.

So, with a fair bit of grumbling, I did. And suddenly, I loved it. I didn’t find Biblical parallels, but I found powerful themes of hope against despair that cut deep into my heart. I didn’t find Aslan, but I learned to appreciate Gandalf on his own terms, as a wise mentor and leader (I didn’t yet know the word Maia). There was no Shasta on the pass to Narnia, but there was Sam’s song in the tower. It was lovely. I talked about little else for weeks.

“Okay, now read The Silmarillion,” my friends said.

And guess what, folks, I somehow made exactly the same mistake. I like tragedies. I like epics. I love epic tragedies. I read lots of Russian lit, so the names still weren’t an issue. The Silm should have been right up my alley. And yet…

In my defense, The Silmarillion does rather invite more spiritual scrutiny. One can’t help but compare Eru Illuvatar to God, oaths to covenants, Arda marred to the curse of sin on the earth.

I went back to my friends and told them I hated it. It bothered me that Mandos explicitly told the Noldor that no echo of their lamentation would reach the Valar. I really didn’t like it that Eru seemed to be holding the Feanorians to their oath (here there was a lengthy comparison to Jephthah’s oath in Judges which I won’t recount). The Valar read as waaaay too polytheistic. On and on.

One of my friends pointed me to a podcast episode that discussed Tolkien’s concept of eucatastrophe. Huh, I thought. I can work with this…

I listened to a whole series of podcast episodes on The Silmarillion (The Prancing Pony Podcast on Spotify, if anyone’s interested.) I had some long conversations with my friends. Read “On Fairy Stories.” Read a handful of Tolkien’s letters. Read the Athrabeth. Then, finally, I went back and re-read The Silmarillion. I could absolutely see the Christian influences, but I wasn’t expecting parallels.

And guess what! I loved it!

I share this because I suspect, based on some of the posts that float around comparing the two, that a lot of people read Lewis expecting Tolkien. They compare The Magician’s Nephew unfavorably to Ainulindale. They make jokes about the Narnia’s fairy-tale mosaic style of worldbuilding and particularly about how much Tolkien hated the inclusion of Father Christmas. Guys. They’re different writers.

Narnia is an explicitly Christian fairytale. Lewis world-builds by pulling together strands of various mythologies and different literary genres and traditions. Homer, Shakespeare, Edith Nesbit, Irish immrama, Arthuriana. He makes specific statements about God, faith, and theology that work both in- and out of universe. He is instructive, occasionally didactic, always entertaining. He emphasizes the spiritual journeys of his characters and particularly their relationships with Aslan.

The Tolkien Legendarium is an intricately crafted mythos centered around Tolkien’s own philosophy, particularly his philosophy of history, and his scholarly interests. Geography, poetry, and particularly language are all of immense significance. Important are themes of lamentation as the world gradually decays and greater ages give way to lesser ones. Hope. Eucatastrophe, and the promise of eventual renewal. Meditations on life, death, and mortality. Tolkien’s faith deeply informs all of this, but isn’t the primary focus, nor even the theology of his subcreated world.

It’s easy to conflate the two. Together they are fathers of the modern fantasy genre, to say nothing of the fact that they were besties™. It’s only natural that familiarity bias causes us to approach one through the lens of the other. But they are very different writers. They write from very similar starting points, with similar values in common, but their works deserve to be approached on their own terms.

We owe it to Jack and to Tollers.

34 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi! The same Anon here: yes, I'm in!!! And what can you say about Galadriel and Finrod, you mentioned that there are parallels between both, what did you mean? I know that Finrod wanted lands to rule the same as Galadriel...

Great! I’ll make a little announcement here about my Twitch channel when everything will be ready (probably within two weeks or so).

Now, concerning your request, I must warn you first, my answer, which takes the form of painstaking yet not exhaustive analysis, will be quite long, but (I hope!) not too tedious.

[Finrod’s heraldry by J.R.R Tolkien, 1960, MS. Tolkien Drawings 91, fol. 29)

Felagund and Galadriel are alike in many ways, especially in their respective evolution, even though those two characters have quite different motives and temperaments.

We’ve already talked a lot about Galadriel in my last post, so I won’t repeat it. As for Finrod, we know he was “like his father in his fair face and golden hair, and also noble and generous heart, though he has the high courage of the Noldor and in his youth their eagerness and unrest” (UT 2 Ch. IV). Both Galadriel and Finrod were proud, “as were all the descendants of Finwë save Finarfin”, “and like her brother Finrod, of all her kin the nearest to her heart, she had dreams of far lands and dominions that might be her own to order as she would without tutelage” (UT2, Ch. IV).

Yet, although, Finrod “had also from his Telerin mother a love of the sea and dreams of far lands that he had never seen”, he wasn’t so eager to leave Valinor during the Rebellion of the Noldor:

“But at the rear went Finarfin and Finrod, and many of the noblest and wisest of the Noldor; and often they looked behind them to see their fair city…” (The Silmarillion, Ch. 9)

Whereas Galadriel “was eager to be gone” for the reasons we have already seen.

We can probably say they share this desire to rule over a kingdom of their own, even though it seems stronger in Galadriel, while her brother appears to be driven mostly by loyalty towards his cousins and his curiosity.

But beyond their temperament, there is a whole narrative arc that corresponds both to Finrod and Galadriel, and in order to try to keep it as clear as possible, we’ll go step by step…

Foresight : Fate and free-will

You have probably noticed that they both have the gift of foresight, which is mentioned, strangely enough, in two very different settings, and yet, the meaning of their words are quite similar. In The Silmarillion, (ch. 15), Galadriel asks her brother why he would not take a spouse, and

“… a foresight came upon Felagund as she spoke, and he said : ‘an oath I too shall swear, and must be free to fulfil it, and go into darkness.’”

As for Galadriel, in The Fellowship of the Ring (ch. 7), after Sam had looked into the Mirror, she explains that

“it shows many things, and not all have yet come to pass. Some never come to be true, unless those that behold the visions turn aside from their path to prevent them.”

As Tom Shippey explained in The Road to Middle-earth, here, “she articulates a theory of compromise between fate and free will”, and we find the exact same ambivalence with Finrod who should be “free to fulfil his oath” (although he can choose to not be free), while acknowledging his fate as something that is already written and from which he must not stray. In other words, it is his fate to take an oath that will drive him to his death, but he’s still free to ignore it, free to “turn aside from [the] path” that was appointed by Eru Iluvatar. That is where resides the tension of free-will.

Leo Carruthers in Tolkien et la Religion explained how this notion of free-will is fundamental in Tolkien’s work:

“If the heroes don’t have to make a choice because the path to take seems obvious… if criminals couldn’t repent, the story of the Lord of the Rings would be far less interesting” (Tolkien et la Religion) (my translation).

According to him, we can understand the term “Free People of Middle-earth” as people who “can use their free-will to decide between good and evil”. It is, as Carruthers comments, to be understood through the Christian notion of salvation, because “if mankind couldn’t tell good from evil, they wouldn’t be able to choose one of the other.” (we’ll talk about salvation later).

Coming back to Middle-earth, where fate has to do with the Tale of Arda as it was given in the Music. Finrod is free to follow the fate which appeared in his vision, or to refuse this role.

And what is Finrod’s role in the Tale of Arda? To help in Beren’s quest for the Silmaril, a tragic quest, but which, in the end, enhanced the beauty of Arda through the marriage between a Maia-elf and a Man, through the Peredhil, including Eärendil and his settlement in the sky with the Silmaril on his brow. And remember that Eärendil is a figure of hope for both Elves and Man.

Finrod knows the path of his fate will be a tragic one, but he also believes that there will be a happy ending; a happy ending which won’t happen if he decides to ignore his fate.

Estel and the eucatastrophe

And that’s what it’s all about : Estel, “a strong hope in Eru, which can’t be separated from trust”, says Carruthers, who then adds that it is obviously very similar to the Christian faith in God.

Finrod accepts his fate because he has Estel, he has faith in Eru and in the Tale, and he acknowledges that his sacrifice will be part of something bigger, something beautiful in the end (the well-known “eucatastrophe”). Tom Shippey wrote :

”Tolkien of course, being a Christian, did in absolute fact believe that in the end all things would end up happily, in a sense they already had… the difference between Earth and Middle-earth, one might say, is that in the latter faith can, just sometimes, be perceived as facts.”( The Road to Middle-earth, Ch. 5).

Estel means believing, it means having faith in the happening of a eucatastrophe, that is the “fairy-tale salvation” (T. Shippey, The Road to Middle-earth, Ch. 6).

I already talked a lot about Estel and Finrod in the past, and in an old post I wrote: “In the whole Beren-mess story I believe that Finrod saw himself as a sort of ‘martyr’, being convinced that he was accomplishing Eru’s will in helping Beren – Finrod clearly follows what I call the Estel-principle.” [I also already explained why I judged Estel to be an act of faith, so feel free to have a look at this other old post for more details.]

Remember his words in the “Athrabeth Finrod ah Andreth”:

“If any marriage can be between our kindred and thine, it shall be for high purpose of Doom.” (HoMe X, part IV)

As for Galadriel, just like Finrod with Beren and Lúthien, she becomes a tutelary figure for Aragorn and Arwen: not only they pledge their love in Lothlórien, but more importantly, Galadriel gives her blessing to Aragorn in The Fellowship of the Ring (Ch. 8), when she gives him the Elessar as a bridal gift. Celebrian being gone, it’s the grandmother’s role to offer it. But the stone is also a symbol of protection towards the couple, although Elrond has not yet completely agreed since Aragorn is not king yet :

“Arwen Undómiel shall not diminish her life’s grace for less cause. She shall not be the bride of any Man, less than the King of both Gondor and Arnor” (The Return of The King, Appendix A)

Galadriel accepts the marriage because she believes that it shall happen “for high purpose of Doom”, just like Finrod about Beren and Lúthien’s. And it’s no coincidence if Aragorn is called Estel: he is the hope of Mankind as the Fourth age draws closer. It can even be argued that, if Aragorn hadn’t had the blessing of Galadriel and the certainty the he would be able to marry Arwen once king, maybe he wouldn’t have accepted the crown with such eagerness.

Anyway, I do believe that Galadriel’s protection over the lovers is considerably important, as important as Finrod’s sacrifice for Beren’s life. Both become some sort of guardian angels for those two couples, and they accept this role (no matter the sacrifice they’ll have to make on the way) precisely because they believe in a happy ending, because of Estel, which is, in the end, the belief in a just retribution: if they don’t go astray, they will end up wiser and stronger, if not happier, whether in this life or in the afterlife (see Annie Bricks in Dictionnaire Tolkien, entry ‘Retribution’). As I said earlier, one of the most poignant embodiments of Estel is Eärendil, it is thus no surprise if Galadriel offers the Phial of Eärendil to Frodo.

Friendships with Men

If Finrod had long before his meeting with Beren become a friend of Men, Galadriel, on the other hand, hardly had any contact with mankind before the Third Age. It is thus significant that she, “the last survivor of the princes and queens who had led the revolting Noldor to exile in Middle-earth” (The Road Goes ever On), acknowledges and gives her blessing to the marriage between a Man and an Elf.

It is also significant that this blessing is symbolized by the exchange of gifts, for, as Eric Flieller explained in le Dictionnaire Tolkien (Vincent Ferré et All, entry “Don”), exchange between Men and Elves are “signs of alliance between the children of Eru”, just like weddings.

Moreover, Sébastien

Maillet ( (in “L’Anneau de Barahir”, Tolkien les racines du légendaire, 2003), noticed

that « finrod had received the difficutl task to guide men in their

discovery of Middle-Earth, while Aragorn accept the tole to govern them after

the Elves have left.”

Furthermore, another gift is present in the story of Aragorn and Arwen : the Ring of Barahir, the token of the union between Elves and Men, which Aragorn gave to Arwen, granddaughter of Galadriel, herself sister of Finrod who probably received it from their father in Aman (Finarfin being probably the one who crafted it), and who gave the Ring to Barahir, father of Beren, himself an ancestor of Aragorn and Arwen. (ha!) We go round in circle, aren’t we?

This ring is, according to Elrond’s words to Aragorn a, token of “their kinship from afar” (The Return of the King, Appendix A), a kinship which has been able to evolve (if not to exist) thanks to the protection and tutelage of the House of Finarfin.

In both cases we have an elven lord/lady, who is engaged in exchanges (of gift, knowledge, or assistance) with Men, with the hope (Estel) that it would save Arda from perils, and eventually lead to the accomplishment of the Tale of Arda. And for that they’re both ready to fight and to make sacrifice, of different natures of course.

Sacrifices

Finrod sacrificed his life in the pit of Tol-in-Gaurhoth. Galadriel sacrificed something much more complicated to define : she accepted the fact that the role of the Elves in Middle-earth was dwindling, she sacrificed her pride and her ambitions.

“She also possesses humility and a willingness to sacrifice her own desires for the greater good, as evidenced by her resistance to the temptation to take the One Ring from Frodo, even though this would make her the most powerful being in Middle-earth.” (source).

She also sacrificed her granddaughter when she accepted the marriage, since Arwen would never be able to follow her family in the West. Bur more than simple “martyrs”, Galadriel and Finrod are also fighters.

Fights : victory through defeat

Finrod actually contends with Sauron, during the famous song-battle, and soon after he has a real physical fight with the wolf sent by Sauron, while Galadriel’s own life isn’t directly in peril, and there’s no real face to face. In her case, it is a sort of a remote battle against Sauron through the Ruling Ring, its temptation and illusions.

We must also stress that she fights against herself, her own delusions and desires. Yet, in the end, her victory helped nonetheless in the defeat of Sauron.

It would be a shame to ignore the words of Sebastien Maillet (in “L’Anneau de Barahir”, Tolkien les racines du légendaire, 2003), who noted that, while Felagund didn’t succumb to the temptation to appear as a god to the mortals when he first met them (they thought he was a Vala, remember?), Galadriel almost yield to this tempting desire when the Ring came to her. Nevertheless, by freeing herself from her own illusions and pride and by defeating the temptation woven by Sauron, she avenged her brothers.

Nevertheless, Galadriel and Finrod are both winners and losers: Finrod was defeated by Sauron’s song and died as he killed the wolf. He wasn’t able to see the success of the quest of the Silmaril. Galadriel left Middle-earth at the end of the Third Age, defeated like all the elves, by the growing power of Mankind.

In terms of fights, we can also mention the parallel between the way Galadriel cleansed Dol Guldur and the passage in which Lúthien cleansed Tol Sirion which was first and foremost Finrod’s dwelling.

“Then Lúthien stood upon the bridge and declared her power: and the spell was loosed that bound stone to stone, and the gates were thrown down, and the walls opened, and the pits laid bare.” (The Silmarillion, Ch. 19).

“They took Dol Guldur, and Galadriel threw down its walls and laid bare its pits, and the forest was cleansed.” (The Return of the King, Appendix B)

More than an echo, I like to see in this similitude a symbol of revenge of Galadriel in the name of her brother whom she couldn’t help in the First Age. The fact that both Tol-in-Gaurhoth and Dol Guldur had become Sauron’s fortresses is particularly poignant.

Salvation

Beyond their half-defeat, they are still victorious in the end: Finrod’s sacrifice granted him salvation, just like the refusal to take the Ring in the case of Galadriel:

“In reward for all that she had done to oppose him [Sauron], but above all for rejection of the Ring when it came within her power, the ban was lifted, and she returned over the Sea, as I told in the Lord of the Rings (The Road Goes Ever On).

We’ve already talked about that so let’s focus on Finrod:

“They buried the body of Felagund upon the hill-top of his own isle, and it was clean again; and the green grave of Finrod Finarfin son , fairest of all the prince of the Elves, remained inviolate, until the land was changed and broken, and foundered under destroying seas. But Finrod walks with Finarfin his father beneath the trees in Eldamar.” (The Silmarillion, Ch. 19).

He’s the only Elda whose ending is given in such terms. Even Fingolfin’s afterlife isn’t mention, and the cairn made for him by Turgon isn’t described with such positive terms, it’s only “high”, whereas Felagund’s grave is “green”, inviolated”, “clean”. As for the mention of his walking with his father in Valinor, it is clearly an image of redemption.

He has won, because his sacrifice saved Beren, while his sister won, protecting Middle earth from herself, approving and protecting the marriage of Arwen and Aragorn.

In a draft for a letter to Peter Hasting (letter 153), Tolkien himself explains that:

“The entering into Men of the Elven-strain is indeed represented as part of a Divine Plan for ennoblement of the human Race, from the beginning designed to replace Elves”.

And from Felagund’s help in Beren’s quest to Galadriel’s farewell to Middle-earth while giving her granddaughter to Aragorn, the whole plan is made plain. (Ah!)

We must also mention other (aborted) elf-human love stories which involve the House of Finarfin: that of Andreth and Aegnor, and that Finduilas and Turin…If those two tragic relationships never actually happened (because it wasn’t for “hight purpose of Doom”), we nonetheless notice that the alliance of Men and Elves is being mainly constructed around the children of Finarfin and his descendants.

The betterment of the Noldor

Finally, all the tragedies Galadriel and Finrod encountered (including the Rebellion) are at the core of their own evolution: they grew wiser and more powerful than they would have, had they remained in Aman.

Indeed, if Finrod seems to have learned a lot in the contact of Men since his meeting with the People of Bëor, Galadriel seems to have had only a few connections with the Second-Born before the Third Age. And it’s only after her acknowledgement of Aragorn as the hope of Mankind and Middle-Earth that she can humble herself, accepting that her place is no longer in Middle earth.

That’s the power of Estel, which, for those two Elves, is also present in the songs they both sing to chase away darkness.

Songs of hope and “prayers”

In the song-battle against Sauron, Finrod tries to take the mastery by singing about “the birds singing afar in Nargothrond, the sighing of the Sea beyond, on sands of pearls in Elvenland” (The Silmarillion, Ch. 19). He here mentions his hope to escape, his hope to see Eldamar again : Estel.

As for Galadriel, in The Fellowship of the

Ring (Ch. 8), she sings Namarië, which ends with some hopeful final

lines: “Maybe thou shalt find Valimar. Maybe even though shalt find it.”

Tolkien explained that

“The last lines of the chant express a wish (or hope) that though she could not go, Frodo might perhaps be allowed to do so.”

(UT 2 Ch. IV)

Although

Even

if he then explains that the Quenya ‘Nai’ “expresses rather a wish than a hope,

and would be more closely rendered by ‘may it be that (though wilt find), than

by ‘maybe’” (The Road Goes ever on), hope is nonetheless present in this wish, if only for Frodo and for Middle-earth: if she asks for Frodo to be granted a ship to the West, it means she believes he will fulfill his quest and destroy the Ruling Ring. Her song reaches beyond the current, tragic situation, as if she was already expecting a happy ending, even if tainted with sorrow, just like in Finrod’s evocation of Eldamar during his fight with Sauron

in Tol Sirion.

Dreamlands and Craftsmanship

This powerful use of music is part of the powers of Finrod and Galadriel’s art, what the mortals call “magic”, that power of faëry (for more about this, see Tolkien’s essay “On fairy-Story”).

We’re talking here of their capacity to create images, between dreams and illusions, as in Finrod’s song, again:

“The chanting swelled, Felagund fought,

And all the magic and might he brought

Of Eveness into his words” (The Silmarillion ch.19)

or when he sings during the first meeting with the Men:

“Now men awoke and listened to Felagund as he harped and sang, and each thought that he was in some fair dream…” (The Silmarillion, Ch. 17)

Or when he changes the appearance of his companions when they approach Tol Sirion :

“Then Felagund a spell did sing

Of changing and shifting shape.” (”The Lay of Leithian”, canto VII, Home III)

In the case of Galadriel, this art of illusion is woven all around Lothlórien, also called “Dreamflower” by Treebeard, or “Dwirmordene”, that is ‘Phantom Vale’ in the tongue of the Rohirrim:

“Half in fear and half in hope to glimpse from afar the shimmer of the Dwimordene, the perilous land that in legends of their people was said to shine like gold in the springtime.” (UT 3, Ch. 2)

“…through the Dwimordene where dwells the White Lady and weaves nets that o mortal can pass”. (ibid.)

As Benjamin Babut explained in his article “Lothlórien la fleur des rêves” (in J.R.R Tolkien, l’Effigie des Elfes, la Feuille de la compagnie n��3, 2014), this word of Anglo-Saxon origin is to be related to “illusions, hallucinations”, which is to be connected to the name Lórien, originally the garden of Irmo, lord of dreams, to which Lothlórien is an echo.

Lothlórien is a strange forest of gold and silver, the Valley of Gold apparently so different from the underground fortress of Finrod in Nargothrond. On the one hand: stones. Trees on the other. Do you see a pattern, here ? We’re not talking of opposite elements, but of two features that complete one another: Aulë and Yavanna.

“And Galadriel, like others of the Noldor, had been a pupil of Aulë and Yavanna in Valinor (UT 2, Ch. IV),

A fact that makes her, and her brother, friends of Dwarves. For Galadriel “had a natural sympathy with their minds and passionate love of crafts of hand” (ibid.), and we know that Finrod worked hand in hand with them in the building of Nargothrond and employed them for the crafting of the Nauglamír:

“In that labour Finrod was aided by the Dwarves of the Blue Mountains; and they were rewarded well…And in that time was made the Nauglamír, the Necklace of the Dwarves.” (The Silmarillion, Ch.13)

Yet, and this is interesting, if Galadriel acknowledges their value and the need to unite all people of Middle-earth against Sauron, she “looked upon the Dwarves also with the eye of a commander, seeing in them the finest warriors to pit against the orcs (UT 2 Ch. IV).

In any case, she is nonetheless a craftswoman as well, she weaves the cloaks she gives to the fellowship, like she weaves webs of illusion around her realm.

By the Way, S. Mallet in his article also talks of the Ring of Barahir as a symbol of the illusion of Faëry…I think we’ve come full circle!

And now that all this has been said, I cannot emphasize enough Tolkien’s “near obsession” with the rewriting of the character of Galadriel ; he reshaped the character a lot of times after the publication of The Lord of the Rings; some texts are simply incompatible, and it would be purely vain to try to give a fixed, definitive depiction of her.

I’ll put a final period to this quote (source) :

”Whatever the reasons, the great importance that Galadriel had for Tolkien throughout the many iterations of his legendarium and in his reflections on his sub creation should lay to rest any criticism that he paid little attention to female characters in his work.”

#galadriel#finrod#lotr#aragorn#The Silmarillion#arwen#jrr tolkien#beren#luthien#lord of the rings#house of finarfin#wow#I'm so sorry if this mess is illegible#I hope this is not too confusing T.T#I tries my best T.T#ooc

89 notes

·

View notes

Text

When people think that GRRM subverting common fantasy genre tropes in his story means that the ending has to be as shitty as possible..

I could write an essay explaining why this is one of the stupidest things that I keep seeing time and time again in this fandom, but is it worth my time?? Probably not. How do you explain to people that an author subverting common fantasy tropes doesn’t have to equate to them also trashing their entire story just to make a shock value, curve ball ending.

When GRRM talks about subverting fantasy tropes, he’s referring to things in his story like the prophecies. Prophecies in fantasy literature are commonly used as the be-all end-all, but GRRM has instead made prophecies in his story dangerous and fickle things.

GRRM may like to flip fantasy tropes on their heads, but he is still a WRITER. All the foreshadowing, symbolism, and build up in his writing is there for a reason. While yes, this story is unique in that it unexpectedly kills characters off and the good characters aren’t always rewarded because the world is cruel, there are still some things that can be predicted about the story if you take the time to analyze and understand his use of literary devices. It doesn’t make his writing ‘predictable’. It just makes you clever enough to interpret the foreshadowing and symbolism. There is a large portion of the audience that doesn’t.

I wouldn’t call myself an expert but I’ve studied fantasy literature in school, and something you’ll find is that almost ALL fantasy stories have bittersweet endings. They either have a ‘consolation’ or a ‘eucatastrophe’ or both. The wrongs have been righted, but there is a feeling of loss because of how rough the journey has been and how the characters can never go back to how their life used to be. Bittersweet does not mean ‘your fav is going to die and everything sucks’.

The number one question people ask me about the series is whether I think everyone will lose—whether it will end in some horrible apocalypse. I know you can’t speak to that specifically, but as a revisionist of epic fantasy—

I haven’t written the ending yet, so I don’t know, but no. That’s certainly not my intent. I’ve said before that the tone of the ending that I’m going for is bittersweet. I mean, it’s no secret that Tolkien has been a huge influence on me, and I love the way he ended Lord of the Rings. It ends with victory, but it’s a bittersweet victory. Frodo is never whole again, and he goes away to the Undying Lands, and the other people live their lives. And the scouring of the Shire—brilliant piece of work, which I didn’t understand when I was 13 years old: “Why is this here? The story’s over?” But every time I read it I understand the brilliance of that segment more and more. All I can say is that’s the kind of tone I will be aiming for. Whether I achieve it or not, that will be up to people like you and my readers to judge. [x]

So yeah, the ending of this story (both book and show because he shared the ending with D&D) won’t be as bleak as so many people are imagining. Game of Thrones may be dark and intense, but it is still a story that is meant to have a pay off in the end. All good stories do.

#my posts#game of thrones#like damn i admit i haven't read the books myself (though ive read excerpts and know the differences between the books and the show)#but i feel like i know enough about literature to comment on this#byeeee#im not saying that main charas won't die because they still might#but stop saying it's impossible for the mains to get through this because it'd be 'predictable' and too 'good'#yall are playing yourselves

399 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chemical Wedding in Game of Thrones

If GRRM is following alchemy in bringing Jon and Dany together as his alchemical partners, what are the chances of them not just falling in love, but marrying, having children, and surviving?

I am most confident in saying I think they will fall in love and physically join (fulfilling the coniunctio stage). Together they will reconcile the warring factions and save the world. They will probably destroy the Iron Throne. Iron is the 2nd basest metal in the alchemical scheme of 7 metals corresponding to the 7 heavenly bodies observable by the naked eye, and it is completely out of place in the Eucatastrophe GRRM will create.

But after that, who knows?

A lot of fantasy is written for children. The chemical partners are often siblings, even boy-girl twins. So there is no romance. With teenagers, we sometimes get romance, even marriage. (GRRM is definitely in line with fantasy tradition in having underage couples.) For example, Maria and Robin marry at the end of The Little White Horse, as do Meg and Calvin part way through the Wrinkle in Time series. An exception is His Dark Materials, where Lyra and Will make love and save the universe but then have to part and live in separate worlds. Maybe that will change in the new book due in October.

For adult fantasy the picture is mixed. In Shakespeare’s romances (his late fantasy plays like the Tempest, Winter’s Tale, and Cymbeline) the alchemical couple marry and live happily ever after. Example: Ferdinand and Miranda of the Tempest, brought together by her (alchemist) father, the magician Prospero. Then again, Romeo and Juliet fall in love and marry, but have to both die to bring about peace and reconciliation between their warring families.

What about Lord of the Rings? Tolkien “broke” the rules by having his alchemical partners both be male. Supposedly he had trouble writing believable female characters. Frodo does ask Sam to move in with him at the end of Return of the King (Grey Havens chapter) but Sam marries Rose instead. The rose is the preeminent flower symbol of the philosopher’s stone. So Sam gets his happy ever after, with no less than 13 children, in line with the multiplication stage of alchemy. Frodo pines away alone. We also get a couple of Red Kings marrying their White Queens: Aragorn and Arwyn, Faramir and Eowyn. So perhaps there is room for cautious optimism for Jon and Dany if GRRM hews close to the LOTR ending.

What I am hoping for is a sweet ending like Mozart’s alchemical opera the Magic Flute. Tamino and Pamina are tested by walking through fire and flood together. (Yes, being burned by fire and submerged in water are standard features of alchemy stories.) They survive unharmed and marry. I know GRRM only promised bittersweet, but maybe that just means all three dragons need to die so Jonerys can have three children. I’m dreaming I know. Oh well.

I think we may already have seen a Jon and Dany Chemical Wedding, or the beginnings of it at least. The Chemical Wedding occurs when the Sulphur and Mercury characters come together to create the Philosopher’s Stone.

Sulphur is male, Sun, the Red King, fire and air, hot and dry. Mercury (quicksilver) is female, the White Queen, earth and water, cool and moist. GRRM has switched genders on us so Jon Snow, based on his name alone, is water, while Danerys Stormborn’s surname shows us she corresponds to wind, which equals air, not to mention her flying, fire-breathing dragons.

Both have suffered years of testing: physically, as their bodies were assaulted, most notably by fire and water, as well as psychologically and morally. They are ready to join together on a mission to save their world. (Just count the number of times they each said “together” since they met.)

Jon asks Dany at Dragonstone if she would accompany him on the mission to capture the wight. She says no, because that would leave her forces at the mercy of Cerci; she is not yet ready to sacrifice her own interests. So Jon sets out with his small force, which includes several men who had been enemies in the past but have set their differences aside and are now working together. When they are trapped on the island, Jon detaches Gendry to ask Dany for help again. This time she comes, with all three dragons, perhaps influenced by Tyrion’s suggestion that Jon is in love with her and therefore returns her feelings, which we have seen growing in the past weeks. In any case, she trusts him enough now to believe the raven Gendry sends.

At the lake Jon’s self-sacrificing is on full display, while Dany risks her own life and sacrifices Viserion. Then we have a textbook alchemical moment, where Jon is fully submerged into the lake. (The alchemical process consists of repeated cycles of dissolution.being submerged in water, and coagulation.) I have seen a few suggestions that perhaps Jon is somehow immune to cold and ice, the same way Danerys is immune to fire. That would make a lot of sense from an alchemy perspective. In any case, Jon survives his ordeals and ends up in the ship’s cabin.

In their brief conversation Jon and Dany give up their remaining pride and ambitions and surrender to each other, for the greater good. Jon has seen Dany “for what you are” and is willing to submit to her as “my Queen.” Dany agrees to put aside her personal ambitions and join with him to destroy the Night King: “We will defeat him together.”After years of showing confidence, even arrogance about her right to the Iron Throne and the likelihood of success, she shows vulnerability, whispering “I hope I deserve it.” Both of them have been transformed and are united in a common purpose.

The symbolism isn’t perfect. Maybe we;ll get more in the final episode, but we get a lot here.

--The setting is in a small, enclosed room on a ship. The ship is one of many symbols for the alchemical vessel. (See, for example, Shakespeare’s Pericles.)

--He acknowledges her as Queen, so if we can just get her to acknowledge him as a King, we have the King and Queen we need for the Chemical Wedding.

--I looked really hard for some circular symbolism. It may be a stretch but I think when Jon first reaches out to grab her hand, he encircles her fingers. And when she gives him her hand at the end, she puts her fingers into the circle of his hand. (Plus she strokes the back of his hand with her thumb, so there is your first caress.)

--Jon’s wounds are interesting. If Dany needed more convincing about how much Jon is willing to sacrifice for his people, she has it. I have no idea if GRRM would do this, but it would be completely in line with alchemy for Dany to use her body to cauterize and close the wounds. Similarly, if Dany comes down with a life-threatening fever in the future, you could see Jon breaking it with HIS body (ice).

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

/The Power of Easter The beloved author of the Lord of the Rings, J. R. R. Tolkien, created the term “eucatastrophe.” For Tolkien, this word described how the protagonists of a story experience a sudden turn of events that saves them from certain doom. Tolkien believed that the coming of Christ was the eucatastrophe of human history. This is the power of love; it is an unstoppable force that prevails, no matter the odds! Resurrection: The Power of Easter Throughout the ages, humankind has discovered amazing ways to harness great power. We constructed the Hoover dam to hold back 10 trillion gallons of water to provide power to the states of Nevada, Arizona, and California. We split the atom and discovered how to release incomprehensible amounts of energy. We created the internet, allowing the world to access information in ways earlier generations could’ve never imagined. And yet, there is a force which all of us are powerless against; sin. No matter what we do or how hard we try, sin always leads to death. Sin is the great catastrophe of human history. It is an unstoppable cancer spreading from one generation to the next. Until Jesus. At the cross, for the first time in all of history, death was reversed, and a resurrection power was put on display for all the world to see! And God has made this very power available to us all. The Apostle Paul described this in Philippians 3:10-11 “I want to know Christ and experience the mighty power that raised him from the dead. I want to suffer with him, sharing in his death, so that one way or another I will experience the resurrection from the dead!” God’s love is a eucatastrophe. It stops the unstoppable, breaks the unbreakable and saves the unsavable! Praise God that his love has come! Reflection What do you consider to be impossible in your life? How do those things compare to the resurrection power of God? Prayer Father, your Word tells me that with you, all things are possible. Forgive me for thinking otherwise. I invite you to stir up my faith and flood my life with your resurrection power. Thank you that your love has come! #dailyword #readingGodsword #IbelievethewordofGod https://www.instagram.com/tdowning79/p/BwCFloFAYvT/?utm_source=ig_tumblr_share&igshid=1ml350lx00e6e

0 notes

Text

At the heart of modern obsession with twists is M. Shamalyan’s The Sixth Sense. Its ending is a HUGE twist which blows the viewer away; it blew me away. But unlike many of its imitators... and unlike a lot of Shamalyan’s later work, it obeys the two great laws of a successful plot twist:

1. Though it surprises the reader/viewer, on a re-read/re-watch, you can see the groundwork for it, so it feels rooted in what came before.

2. It advances the themes of the story.

The Twilight Zone was all about good plot twists and many of its greatest episodes use it. the sudden revelation which makes everything make sense.

In the Sixth Sense, finding out Bruce Willis is a ghost is well foreshadowed if you re-watch, and it ties into the story well.

But the first great plot twist I ever read is from the Lord of the Rings. Tolkien called ‘happy’ plot twists, ‘Eucatastrophes’.

I first had the Lord of the Rings read to me by my father, one chapter a night. This comes at the end of Book V, Chapter IV: The Siege of Gondor. Everything is going poorly and the gates of Minas Tirith are broken and Gandalf is confronting the Witch King and young me is tense out of his mind.

“In rode the Lord of the Nazgûl. A great black shape against the fires beyond he loomed up, grown to a vast menace of despair. In rode the Lord of the Nazgûl, under the archway that no enemy ever yet had passed, and all fled before his face. All save one. There waiting, silent and still in the space before the Gate, sat Gandalf upon Shadowfax: Shadowfax who alone among the free horses of the earth endured the terror, unmoving, steadfast as a graven image in Rath Dínen.

"You cannot enter here," said Gandalf, and the huge shadow halted. "Go back to the abyss prepared for you! Go back! Fall into the nothingness that awaits you and your Master. Go!"

The Black Rider flung back his hood, and behold! he had a kingly crown; and yet upon no head visible was it set. The red fires shone between it and the mantled shoulders vast and dark. From a mouth unseen there came a deadly laughter.

"Old fool!" he said. "Old fool! This is my hour. Do you not know Death when you see it? Die now and curse in vain!" And with that he lifted high his sword and flames ran down the blade.

At this point, I was super-tense and was worried Gandalf would die again, and I knew he couldn’t return a second time. I’d been stunned the first time; I was only nine and comics hadn’t overdone return from death for me yet.

And in that very moment, away behind in some courtyard of the city, a cock crowed. Shrill and clear he crowed, recking nothing of war nor of wizardry, welcoming only the morning that in the sky far above the shadows of death was coming with the dawn.

And as if in answer there came from far away another note. Horns, horns, horns, in dark Mindolluin's sides they dimly echoed. Great horns of the north wildly blowing. Rohan had come at last.”

Rohan had come at last. It’s all set up and in the next chapter, we find out why and how Rohan had arrived at the nick of time, but it both advances Tolkien’s theme of fighting on, even when darkest, without giving up, and is based on earlier events.

Every time I read anything with an unexpected arrival of help, in my mind, the horns are blowing. Rohan has come.

That’s how a plot twist should work.

The point of a twist is to enrich a story, not feel superior for outsmarting your audience.

@ The Magicians writers

40K notes

·

View notes

Text

"What if Celegorm had managed to kill Luthien when he shot at her?" (First Ramble Meme Post!)

So @urloth asked, "What if Celegorm had managed to kill Luthien when he shot at her?" and requested the first of May, so here I am.

Two ways come to my mind as approaches to this question. First is to think about how such a narrative choice by Tolkien would have affected the overall theme of the Legendarium. Such a decision would have profoundly altered the larger theme, to say the least. Just tonight, I posted to the SWG @heartofoshun's biography of Barahir. The whole essay is worth a read, but the final paragraph is particularly lovely and salient to my point here as well:

This sense of devastating loss, which also echoes the dark fatalism of the Norse epics of which Tolkien was so fond, is certainly central to The Silmarillion and most particularly evident in its Chapter 18, "Of the Ruin of Beleriand and the Fall of Fingolfin."25 We move from a world wherein the shaky balance between the forces of light and darkness is directly threatened and, to steal the words from the poet W. B. Yeats, "[t]hings fall apart; the centre cannot hold; [m]ere anarchy is loosed upon the world, [t]he blood-dimmed tide is loosed. . . ."26 And yet within that smoke-blackened and terrifying world, where the center no longer holds, there remain unwavering heroes like Barahir, with his determination and his hard-won family heirloom, who project hope down through the Ages and into the eucatastrophe of The Lord of the Rings.

As I put it, more or less, in a comment to Oshun on this subject, Barahir is a cog in the larger eucatastrophic machinery: His story is unrelentingly tragic, but we are to understand that his existence ensures defeat of Darkness in the far future. Therefore, the tragedy is acceptable. If he's a cog, Lúthien is a whole clockwork unto herself. If ever there is an emblem of literal and figurative light in the midst of darkness, here you have her, and destroying her in such an ignoble way by a character depicted as all but incorrigible would hamstring the theme of eucatastrophe.

The second approach is to think about how the story would change in an AU scenario where Lúthien dies at this crucial point, prior to recovering the Silmaril. (Because I don't care who was holding the knife: Lúthien totally scored the goal on that one and Beren had the assist.) Most obviously, the Silmaril would not have been recovered, and the existence of key characters like Elwing, Elrond, and Elros would have been rubbed out. If ever you needed to see a scary albeit fictional example of how a single action can completely rearrange history, here you have it in imagining the Second and Third Ages without the peredhil.

Before I get ahead of myself, without Elwing, there is no delivery of the Silmaril to Aman, no war against Morgoth, and Beleriand is not destroyed.

But it's perhaps more interesting to imagine the more immediate consequences of such an act.

I imagine Thingol--already no fan of the Fëanorians and crushed by his daughter's death--waging all-out war against them. This is not a crisis that even the most skilled diplomacy and brother-wrangling of Maedhros could avert.

What of Beren? Unlike Thingol, we get no suggestion that he is a vengeful character. I mean, he's a vegetarian for Pete's sake. It could be that Tolkien, to preserve that innocence and goodness, would have kept Beren's hands unbloodied and allowed him a death of grief.

But in a world (use your movie trailer voice if you want) where eucatastrophe has been essentially erased as a driving principle, what need is there to preserve Beren's goodness? Perhaps he would have become vengeful, ironically healing the rift between himself and Thingol in the interest of pursuit of a common enemy.

Because we also would not have had the second and third kinslayings--no Silmarils to slay over, remember?--I think Lúthien's death would have shifted the focus from the war on Morgoth to a civil war among the Free Peoples of Middle-earth. Now that is a scenario with modern relevance: the inability to unite against a common enemy because of infighting among one's own kind. (We do see hints of this in the refusal of Thingol and Orodreth to send forces to fight alongside the Fëanorians against Morgoth but nothing so overt as actual civil war.)

It may be that there is no line to continue into the Second and Third Ages. It may be that the Fëanorians prevail and become the heroes of those ages. Or it may be that eucatastrophe reasserts itself, and from the grievous loss of Lúthien, a new and unseen source of hope arises.

If there's a topic you want me to ramble about, there's still plenty of slots open in the ramble meme! Drop me an ask of reply to this post with your topic and date.

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Power of Easter

The beloved author of the Lord of the Rings, J. R. R. Tolkien, created the term “eucatastrophe.” For Tolkien, this word described how the protagonists of a story experience a sudden turn of events that saves them from certain doom. Tolkien believed that the coming of Christ was the eucatastrophe of human history. This is the power of love; it is an unstoppable force that prevails, no matter the odds!

Resurrection: The Power of Easter

Throughout the ages, humankind has discovered amazing ways to harness great power. We constructed the Hoover dam to hold back 10 trillion gallons of water to provide power to the states of Nevada, Arizona, and California. We split the atom and discovered how to release incomprehensible amounts of energy. We created the internet, allowing the world to access information in ways earlier generations could’ve never imagined.

And yet, there is a force which all of us are powerless against; sin. No matter what we do or how hard we try, sin always leads to death. Sin is the great catastrophe of human history. It is an unstoppable cancer spreading from one generation to the next.

Until Jesus. At the cross, for the first time in all of history, death was reversed, and a resurrection power was put on display for all the world to see! And God has made this very power available to us all.

The Apostle Paul described this in Philippians 3:10-11 “I want to know Christ and experience the mighty power that raised him from the dead. I want to suffer with him, sharing in his death, so that one way or another I will experience the resurrection from the dead!”

God’s love is a eucatastrophe. It stops the unstoppable, breaks the unbreakable and saves the unsavable! Praise God that his love has come!

Reflection

What do you consider to be impossible in your life? How do those things compare to the resurrection power of God?

Prayer

Father, your Word tells me that with you, all things are possible. Forgive me for thinking otherwise. I invite you to stir up my faith and flood my life with your resurrection power. Thank you that your love has come!

I want to know Christ—yes, to know the power of his resurrection and participation in his sufferings, becoming like him in his death,

Philippians 3:10 NIV

#crazy f.c.#harvest bible chapel#warrior of faith#godsarmy#gods not dead#jesussaves#amen#godswarrior#hillsong united#hillsong#warrioroffaithillinois#godwroteabook#illinois#warrioroffaithoutreach#vertical church#bible journaling#the bible#warrior#hillsong church#torchoffaith#warrioroffaithfamily#crusaders christian#torch of faith#bible#jrnychurch#journey church#journeychurch#easter sunday#happy easter#WOFCrazyFC

0 notes