#ancient statuary

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Extreme Baroque: Iron Temple On The Rice Mountain

Grotesque images from the Buddhist Iron Temple (鐵佛寺).

Located on the Rice Mountain (米山), Mixi (米西村) village, Jincheng, Shanxi, the temple is of an unknown construction date. The earliest record on the stone pillar in the main hall dates back to the seventh year of the Dading (大定) period of the Yuan or Jin dynasties. There is evidence that the temple was reconstructed in the third year of Wanli (1575). However, in the county annals, it is mentioned no earlier than the Qing dynasty.

These astonishing, presumably Ming statues owe their creation to the proximity of an iron ore. Iron frames made it possible to give the clay figures intricate poses and frilly decor.

Photo: ©大关沿路拍

#ancient china#chinese culture#chinese mythology#chinese art#chinese architecture#yuan dynasty#jin dynasty#chinese temple#statues#sculptures#scultpure#buddhist temple#buddhist#buddhist deities#religious art#buddhism#ming dynasty#qing dynasty#statuary#religious imagery

224 notes

·

View notes

Text

This really is a fascinating study. Once again, long-held and assumed beliefs predicated on modern Orientalist points of view are shown to be worth re-examining.

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

I've been sick and really out of it, and felt possessed to print out some classic statues. I asked my partner for one to start with, and they chose Winged Victory of Samothrace

I love that museums and independent organizations just go around using high quality scanners to help make history more accessible, even in small ways like this. I'll likely never visit the Louvre, or Greece if they ever get it back, but I can print my own

#art#painting#canopiancatboyart#miniature#miniatures#3d printing#miniature painting#oil painting#statue#statuary#classical art#ancient history#greece#greek mythology#nike#winged victory of samothrace#hellenistic#monument

327 notes

·

View notes

Text

Gas giant | AI-assisted art by Ian K.

#male form#homoerotic#ancient world#muscular#fantasy#mythological#marble#marble statue#ai generated#ai art#rome#cypress trees#celestial#statuary#garden

23 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello Dr. Reames, I was just curious, what do you think of the bust of Alexander by Leochares, do you think that this might be a true/faithful depiction of the king of Macedonia seeing as it was made during his lifetime? Or no?

So, I actually intended a longer answer to this, but I can't return it to the "asks" queue, because I accidentally posted it with a reply meant for another ask. So I'll give the short answer. But first, here is the Leochares bust to which the asker refers. It's perhaps better known as the Akropolis Head (of Alexander). It is, as you can see, the model for the old cover of Dancing with the Lion 1: Becoming.

So, how accurate is it?

Medium. It shows what we might today call photoshopping, because it's tweaked to better suit the traditional cannons of male ephebe beauty. The face is oval, the mouth small and bow-shaped, the eyes larger than average.

But it's still clearly an Alexander, not a generic ephebe. The hair is not as tightly coiled, for instance; the chin looks like his in other statues. The eyes, although larger, have similar eyebrows. Compare that statue to the Azara Herm, which may be the closest likeness.

So as long as we recognize it as "idealized" (which was very common in Greek statuary right into the early Hellenistic period), I'd say it's not a bad image. After all, I liked it enough to submit it as a model for the novel. :-)

#asks#Alexander the Great#Alexander statuary#Leochares#Acropolis Head of Alexander#Azara Herm of Alexander#ancient Greek sculpture

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Terracotta figurines of women with their everyday attire and adornments, 2nd century BC,

Pella archaeological museum (Macedonia, Greece)

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Io Saturnalia

København, Denmark

1 note

·

View note

Text

thinking about how this cat belongs to forsythe and i's professor

#not just any professor either like we went to a conference with him and he hosts our club and he gifted cam a stunning book#about ancient garden statuary#i literally am not in a relevant major or minor to his area of study but you know my ass was in his independent study#WE WENT TO DINNER WITH HIM.#also for ppl who know about forsythe and i's relationships with professors THIS IS NOT THE EVIL ONE WHO HOLDS MY HUSBAND CAPTIVE#salad dad#studies

0 notes

Text

"Ram in the Thicket" Statuette from Ur (Iraq), c.2600-2400 BCE: this statuette is made of lapis lazuli, shells, gold, silver, limestone, copper, and wood

This sculpture is about 4,500 years old. It was unearthed back in 1929, during the excavation of the "Great Death Pit" at the Royal Cemetery of Ur, located in what was once the heart of Mesopotamia (and is now part of southern Iraq).

Sir Leonard Woolley, who led the excavations at the site, nicknamed the statuette "ram caught in a thicket" as a reference to the Biblical story in which Abraham sacrifices a ram that he finds caught in a thicket. The statuette is still commonly known by that name, even though it actually depicts a markhor goat feeding on the leaves of a flowering tree/shrub. Some scholars refer to it as a "rampant he-goat" or "rearing goat," instead.

It was carved from a wooden core; gold foil was then carefully hammered onto the surface of the goat's face and legs, and its belly was coated in silver paint. Intricately carved pieces of shell and lapis lazuli were layered onto the goat's body in order to form the fleece. Lapis lazuli was also used to create the goat's eyes, horns, and beard, while its ears were crafted out of copper.

The tree (along with its delicate branches and eight-petaled flowers) was also carved from a wooden base, before being wrapped in gold foil.

The goat and the tree are both attached to a small pedestal, which is decorated with silver paint and tiny mosaic tiles made of shell, lapis lazuli, and red limestone.

This artifact measures 42.5cm (roughly 16 inches) tall.

A second, nearly-identical statuette was also found nearby. That second sculpture (which is also known as the "ram in the thicket") is pictured below:

There are a few minor differences between the two sculptures. The second "ram" is equipped with gold-covered genitals, for example, while the first one has no genitals at all; researchers believe that the other sculpture originally had genitals that were made out of silver, but that they eventually corroded away, just like the rest of the silver on its body.

The second "ram" is also slightly larger than the first, measuring 45.7cm (18 in) tall.

Both statuettes have a cylindrical socket rising from the goats' shoulders, suggesting that these sculptures were originally used as supports for another object (possibly a bowl or tray).

The depiction of a goat rearing up against a tree/shrub is a common motif in ancient Near Eastern art, but few examples are as stunning (or as elaborate) as these two statuettes.

Sources & More Info:

Penn Museum: Collections Highlight

Penn Museum: Ram in the Thicket

Expedition Magazine: Rescue and Restoration: a History of the Philadelphia "Ram Caught in a Thicket" (PDF version)

The British Museum: Ram in the Thicket

A Companion to Ancient Near Eastern Art: Statuary and Reliefs

World Archaeology: Ram in the Thicket

Cambridge Scholars Publishing: Colour in Sculpture: a Survey from Ancient Mesopotamia to the Present (PDF excerpt)

Goats (Capra) from Ancient to Modern: Goats in the Ancient Near East and their Relationship with the Mythology, Fairytale, and Folklore of these Cultures

#archaeology#history#artifact#anthropology#ram in the thicket#sumerian#mesopotamia#ur#goat#ancient art#sculpture#iraq#ancient near east#art#lapis lazuli#gold#statues#mixed media#inanna#dumuzi#mythology#rampant he-goat#has a nice ring to it

289 notes

·

View notes

Note

Since Henry is obsessed with Ancient Greece and Homer… what if after Richard, Julian makes another addition in class? And she is intelligent, pretty much in par with him, and can get along with the class better than Richard. But what captured his attention the most is— she looks like she was ancient greek painting or sculpture that came to life, like Galathea.

How do you think that would go?

I need to feel something other than angst and sadness and pain🥹😭

Thank you!❤️

this is basically half your request but half not because i don't write anything painless. this time, it's a slightly OOC henry suffering instead of you, though! i wrote this with @mrs-dot-kennedy & without her, this fic truly wouldn't exist. i was going to just say no. all thanks and credit are really hers.

some faded attic dream (to kiss or to kill you.)

henry winter x fem!reader

It’s an unseasonably warm morning in mid September when you start taking a lone class with Julian. He doesn’t like taking on students who won’t study with him only, but there’s something about you that strikes a mischievous twinkle into his eyes when you meet; something that has him breaking his rules once again.

The air is sweet, as all across campus apples are beginning to fall and rot beneath their trees much faster than students or gardeners can collect them. It’s bright outside, everything tinged soft yellow by the sun, and the air still manages to hold a note of crispness; the promise of death to come.

You show up just as Julian is about to begin speaking, just exactly on time. A cream cashmere shawl drapes lazily over your arms and shoulders like an afterthought, contrasting against the navy blue of your dress. Your hair is pulled up out of your face so that your cheeks, pink from your brisk walk, are in full view.

“Good of you to join us, darling, I was beginning to worry you might not make it.” Julian says, his face crinkling up with pleasure.

You smile softly and slide into the nearest open seat, right between the redhead with a nervous mouth and an unnervingly stoic man built for football, features contrasting in a way that makes him look dead. Francis and Henry, you learn when Julian takes a moment to introduce you to everyone you don’t already know before launching into his lecture with gusto.

You do not look at Henry when he speaks. This alone would be almost unforgivable without your lateness; combined, it is an affront to both higher education and him. You do not seem to place value in his opinions right away. It’s agonizing. You recline in your chair as Julian speaks like a fragment of an antique statuary carelessly arranged by some indifferent hand, and the room— with its the smell of old books and tea, of faded carnations and fine dust— sinks in around you like mist.

Your voice, measured and low, responds not to any one person, but to the room itself— or perhaps to the text, as if your interlocutor might be Homer, or Plato, or Julian, or no one at all— and this is unbearable.

The others have noticed you, of course. Francis with a kind of awe, Richard with the open admiration of a dull boy who has never seen grace, Charles with a shy sort of softness. But none of them recognize the thing he sees at once: the uncanny resemblance not to any living woman, but to something conjured from myth and pigment, from wet clay hardened by fire and time.

With the way your features slope in the bright lighting you look more like you belong on the walls of P. Fannius Synistor’s Boscoreale Villa, immortalized by oil; or perhaps even unearthed from stone, displayed in an echoing hall between the Three Graces and Kephisodotos’s statue of Eirene. You could easily have been dredged up from ruins and dusted off before walking into this room, and Henry wouldn’t be surprised.

Henry watches you with the same rapt attention he has reserved all his life for hidden structures and formal systems, yet you confound all of it. There is nothing structured about your presence, no formality within your glances or speech. You smile at Bunny when he makes a joke in poor taste. You compliment Camilla on her earrings.

One day, you tell Julian that you prefer The Odyssey to The Iliad. And he smiles as he responds, words fond and slow, almost grandfatherly as he says:

“Yes, many women do.”

But it is not The Odyssey that lives in your eyes, Henry thinks— it is The Iliad, crashing and blazing and violent, dipped in red and gold. When you walk out of the room he sits motionless, confounded and dumb, forgotten among teacups and Latin dictionaries, like a man in Apollo’s temple might sit and ponder once the Oracle has gone silent.

The beauty you possess is understated by modern standards, of course, but in nature it is one many have captured in stone, oil, and tapestry. You look, to him, as if you’ve gotten lost in the threads of time itself, found yourself in Vermont by mistake.You ought not to be seated like this, close enough to touch as you absorb Julian’s lecture with quiet surety. You ought not to be in a lecture at all. You ought to be enshrined behind glass and gold somewhere, with a small white placard at your feet reading: Origin unknown. Circa 5th century B.C.

He doesn’t know what the feeling knotting into his chest is when you come into his line of sight or his mind— Henry Winter is not a man who ever finds himself unnerved by beauty beyond that which is found in language; where letters and syllables are bent and re-arranged until they haunt. Whatever the feeling is, he despises the way it spears through and taunts him each day.

You turn up once in a crimson velvet cloak. The hood is pulled over your hair, the buttons fastened neatly down the front to keep the harsh autumn winds from biting, and you look even more surreal this way; life breathed into a fairy tale illustration. You laugh when Charles steals the words straight from his mind, pointing out the resemblance. It’s a real laugh, unstudied and surprised, your head tilting slightly as you look out at him from beneath your lashes.

It cuts through Henry like a dull blade. You have never laughed at anything he’s said, and he’s unsure why but this bothers him. When he speaks, you listen with the courteous detachment of a priestess attending to an uninteresting supplicant and answer only when required, as if your words are something to be earned.

In discussing Thucydides one day, Julian declares that your class would have little trouble taking Hampden if they so wished. And while Francis laughs joyfully at the prospect of becoming a crew of seven Demigods, Henry wonders what you would look like with spoils of war heaped at your feet. Precious delights like rubies and gold, vases filled with olive oil and sweet wine.

Later, when he sees you alone on the green, seated beneath a white ash tree with your shoes tucked neatly beside you, he does not approach. He simply watches, concealed behind the pages of Herodotus, and thinks— not for the first time—that it is not the gods who haunt this place, but something older, something gentler and more devastating.

He tells himself that it doesn’t matter, not really. You are just a girl. A student. Another fleeting constellation in the brief, bright sky of Hampden. But when you leave the room again, the scent of bergamot and old paper trailing behind you like the remnants of some ancient rite just completed, he feels emptiness prying open his chest; as though you’ve stolen something from him without ever touching him at all.

There is something set-apart hidden in your posture. Something profound in the way you bend your head over the table, soft lips parted open just so while you read. Something kind in the way you correct Richard’s translation of philotēs during a lull in class. You do so with your voice soft, words falling from your mouth with a honey that borders on apologetic. Henry already knows it’s wrong, of course— he notices before you manage to— but hearing you say as much aloud stirs something unexpected to life: not irritation, but an odd sense of relief, as if some hidden order had just been restored.

He has never once been good at identifying the feelings within himself or others; it’s more confusing to him than even the most complex conjugation or declension. Nuances in human emotion are far blurrier than those in languages, especially languages long buried. Languages have rules. Languages have order, and there is a maddening lack of it in the way you flip through pages, or the explosive, intoxicating way you laugh. You live by a set of rules, it seems, that he has seldom encountered; that he hasn’t paid any mind to when he has.

You are just a girl, he reminds himself every time he catches himself looking too long, transfixed by the way your fingers wrap around your pen when you make notes in book margins; stunned once more by the way you swirl into the room, dusting snowflakes from the shoulders of your fawn colored overcoat.

He likes girls very much and always has, of course, but never has one distracted him from his studies. Never before has one reminded him so strikingly of the hand painted china teacups his mother collects and lines up along the parlor mantel back home, or the prisms in the windows of their library. Never has he felt so much like he desires one’s company, ‘nor has a woman ever struck him as a self sustaining piece of art. This is something he can’t understand.

He hates it. The way his whole body curves toward you without him physically moving; the way you’re a constantly present mimeograph in his mind, classical features immortalized in blue ink– and he knows it’s absurd. You will forget him— likely already are— and yet he will remember you in the sharp, electric way one remembers lighting long after it has disappeared back into the sky. He tells himself that he doesn’t care if you do forget him.

You speak about kleos in class, softly yet without hesitation, explaining the terrible paradox of eternal glory: how it is won only through ruin, how even Lord Achilles had to die for his name to echo across centuries. Julian is enraptured and the others listen, nodding intermittently in the way people do when they don’t quite understand, but desperately want to be seen as clever. And Henry—he sits so still that it feels like something is breaking inside him. Not because of what you say, but because of the way you say it.

You speak of glory like one who has seen it firsthand, as if you were there to watch Hector’s body get dragged through the dust from the safety of a painted amphora. And when you finish speaking, when your voice fades and the room returns from the battlefield, back to the ticking of the clock and the smell of bergamot, Henry cannot meet your eyes. He feels as if you’ve stripped him down to bone, as if you can see him better than anyone else could dream of. You terrify him in the same soft way the sacred does, in its quiet refusal to be understood.

There is a brief moment when your hand brushes against his as you pass him an open book. It’s irrelevant, really. A graze, a flicker of warmth and nothing more. Still, Henry finds he can no longer read the page your thumb rested against. It is as if the words had been scoured away and replaced with something ancient and wordless.

He spends half an hour staring at a blank margin, trying to decide whether it’s madness or reverence that tightens like a garrote at the base of his throat. He tries to decide whether or not it is love. He doesn’t even believe in love, not really. It feels silly to entertain the thought— but he also no longer believes, not entirely, that you are real. So perhaps things are changing.

Of course, you are real: there’s tangible proof of this fact only days later, when you slice the delicate skin of your finger open on the corner of a page. You gasp softly and deathless ichor does not bead along your open skin as he half expects it to; instead the watery, warlike red of mortality blooms. It’s pretty, even as Charles offers you a handkerchief to wipe the blood away. You bleed like a painting and it stills Henry’s breath.

Your presence is even more agonizing as Christmas draws closer— as Hampden fills with deep drifts of wet, white snow, and peppermint and cinnamon cling to the air— because he knows that you’re real and still, he does not command your respect or adoration the way he commands that of the others; you do not gift him the same affectionate attention as Camilla.

You’re arranging your soft woolen mittens on the radiator to dry, soggy with the memory of snowballs scooped up by your hand when you respond wittily to something Bunny says. Conversation seems to crash around you at once, vying for your approval, and a shocking ache twists into his chest like ice cold ocean water, suffocating as it drowns him.

He has begun to resent the way you speak. Not for any failure of insight— your translations are crisp, your references impeccable— but for the way you attract the room’s attention without trying; the way even Julian leans forward when you start to argue a point. You’ve become something of a fascination, even for the less astute among them. Richard looks at you like you are a miracle. Charles, predictably, lights up when you laugh. And Henry watches this unfold with the cold clarity of someone who has already calculated the theorem and is now forced to watch the rest of the class stumble toward it.

They fawn because they are lesser. You bother him because you are not and therefore don’t. It should be gratifying, matching wits with someone at his level, but instead, it infuriates him. Henry assures himself that you are not smarter, not sharper, but merely a well-made echo of something else— some faded Attic dream come walking. And yet, when you interrupt him— gently, yes, calmly, yes, but because you disagree— he feels something thin and sharp splinter deep behind his eyes.

You’re clever. You know exactly what you’re doing to him. That’s what he decides as he watches you tease out a metaphor from Aeschylus with effortless grace, as if you’ve had the structure memorized since infancy. He starts correcting you, deliberately and precisely, in ways that are not quite wrong but not quite necessary either. And you only tilt your head, blinking once, twice, before responding without rancour.

That is what makes him angriest. You never rise to meet him in the place where he wants you most: the realm of serious, unrelenting intellect, where brilliance burns like magnesium and leaves the unintelligent to fall behind. You will not even condescend. You only smile like you mean it— how kind of you to mention it, Henry, but I think the verb there actually is in the present tense— and go on speaking as if he doesn’t draw blood.

No man is above criticism, nor correction, and this is something he believes far more deeply than in any god or creation myth. But this is simply not something that happens to him; he finds himself the strongest intellect in each friendship that has wormed its way into his day to day. And that is, perhaps, the final insult: not that you wound him, but that you don’t even know you have done it.

One person should never hold this much sway over his emotions, this much weight in his mind. The space you take up compares only to that of Julian’s, to Homer’s, and he doesn’t believe that you deserve it. He begins to understand, though he won’t admit it, why godlike Paris stole and defended Helen so ardently. He begins to understand, in a way that angers him further, why so many stanzas have immortalized women like you. You are even more of an equal to him than he initially realized, and he can’t tell if he wants to absorb or erase your existence– to kiss or to kill you

You start seeing Charles soon after. It happens all at once, as though some ridiculous Roman comedy has been enacted around him while he was too busy puzzling out how he feels. You wear Charles’s coat to class one morning. It’s too long for you and the sleeves fall over your wrists like a cheap children’s costume.

You blush when he touches your arm. You tuck your hand beneath his elbow as you walk together across the quad, the way women used to do in oil paintings of the Georgian period: demure, practiced, possessive. And Henry says nothing. He only begins to escort Camilla to class, her perfume trailing behind like smoke, her soft smile fixed in place like a relic from a scene staged too carefully to abandon. He touches her shoulder. He tells her she looks lovely in French. She looks at him with something like love and he does not care. It is the symmetry that pleases him.

It should be easier to hate you now. But it isn’t. If anything, you have grown stronger in his imagination— more vivid, more mythic. Like Helen in Euripides, you’ve become more powerful in absence than you ever were in proximity. He sees you out the window once, your fingers tied up in Charles’s hair. It’s obscene. Not because of the intimacy, but because you don’t look divine anymore: you look human. Soft. Caring. And still, Henry cannot stop watching.

There is something unspeakably degrading beneath all of it now: under how much space you occupy in his thoughts, mixed into the way his stomach tightens when your voice reaches out to him from the hallway. You have dethroned Gods without lifting a finger. And when Julian asks a question you cannot answer, when your face clouds over for just a moment, an ugly, gleeful satisfaction blooms in his chest like rot.

It is the first time he has been able to look at you and feel nothing like reverence. Only what he feels this time is hunger. You are not his, you are Charles’s, and yet he wants to claim each sigh and soft smile that graces your face for his own. He wants to trap and cage them between his teeth, to tear them apart until he can breathe again; until you look something worse than human, something grotesque enough that he might finally turn his thoughts elsewhere.

It’s not fair to sweet, soft, messy Camilla, who stares up at him the way he wishes you would— as a man freed from black darkness for the first time might marvel at the stars and who hung them— but you sullied the meaning of fair the moment your watercolor eyes skimmed over him with disinterest that first day. He cannot bring himself to mind.

Spring blooms up through the ice and slush slowly, then all at once. It brings with it cotton dresses and bare arms and ink stained hands holding wildflowers, which you present to Julian as you stumble in late with a bashful smile, declaring that they remind you of last week’s reading. It brings with it the smell of fresh cut grass floating from your hair when you walk past him; it brings visions of you in Dante’s sacred wood, singing in dulcet tones as you haunt Earthly Paradise.

You’re still human, distinctly, but spring brings with it the echoes of the you he once saw: the sacred beauty brought to life from her painting or poem to torment him tirelessly. It’s shameful and obsessive, the way he continues to think of you still, yet it is also addictive that he cannot bring himself to stop. You persist in his mind both fully formed and in shadow as if you’ll never leave. You are heaven. You are a plague. You move through the world like you have never been wounded, and it offends him. How can you remain whole when he feels cleaved in two?

He tells himself it’s a philosophical reaction, a natural response to order misaligned, but he dreams of you— not as you are now, but as something monstrous and cruel, a muse sharpened of firelight. He tastes you in the vowels of Homer. You are not divine, he tells himself. You are a symptom. A fever. A lapse in judgment. And still, he memorizes the way your script loops when you write. As if it’s hallowed, as if it’s blessed.

When you smile at him, one last time— briefly, absently, an afterthought—he feels a relief so profound that it borders on despair. You have seen and dismissed him and that is all. You will never worship what he has made of himself. You will not know the weight he bears. You are not Galatea after all, not a statue granted life but a girl simply walking off into the sunlight, toward a summer filled with sweet joys. He watches you go, white dress catching the breeze like a banner in retreat, and he does not follow.

And for the first time, Henry feels the breadth of his solitude. It is not tragic. It is merely true.

#henry winter x reader#henry winter fanfic#henry winter#the secret history#mrs. ken!#[𝐢 𝐫𝐞𝐜𝐞𝐢𝐯𝐞�� 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐟𝐨𝐥𝐥𝐨𝐰𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐥𝐞𝐭𝐭𝐞𝐫; asks!]#koi!

51 notes

·

View notes

Photo

A Gallery of Mesopotamian Religion

Mesopotamian religion was informed by the belief that humans were co-workers with the gods in maintaining the order created at the beginning of time and so religious expression was integral to daily life in ancient Mesopotamia in how they chose to perform tasks on the job, behave toward others, and honor those gods.

Among the most common displays of respect for the divine was Mesopotamian art and architecture in which the deity's depiction emphasized some defining characteristic. The terracotta plaque, Ishtar Standing on a Lion, for example, shows the goddess armed above a subdued lion, symbolizing her role as a powerful war deity. The stamp-seal of Gula, goddess of healing, depicts her in the presence of one of her dogs – also associated with healing – welcoming a supplicant, in keeping with her primary role.

The gods of ancient Mesopotamia were not only venerated through formal artwork like plaques or reliefs, however, but through everyday objects – amulets, charms, figurines – one would carry or keep around the home to court a certain deity's favor or ward off the threats from evil spirits or demonic energies. This was also true of temples where foundation figures, in the form of the king who commissioned the building, were ritually buried to mark off the sacred from the common areas.

Since the world was understood as alive with spiritual energies – positive and negative – it was considered prudent to take measures to attract the bright energies and defend against the dark through sacred objects used to ward off bad luck, ghosts, the schemes of sorcerers, and the physical maladies that were recognized as either a spiritual attack or the result of one's own sins and a god's displeasure.

The following gallery presents a sampling of the stele, amulets, statuary, figurines, and temples, which developed from Mesopotamian religious belief. Among these are some of the most famous works from the region such as the Code of Hammurabi, the Mask of Warka, the Warka Vase, and the Nimrud Dogs along with lesser-known pieces including the votive figures, stamp seals, cylinder seals, spells, and reliefs.

Continue reading...

173 notes

·

View notes

Text

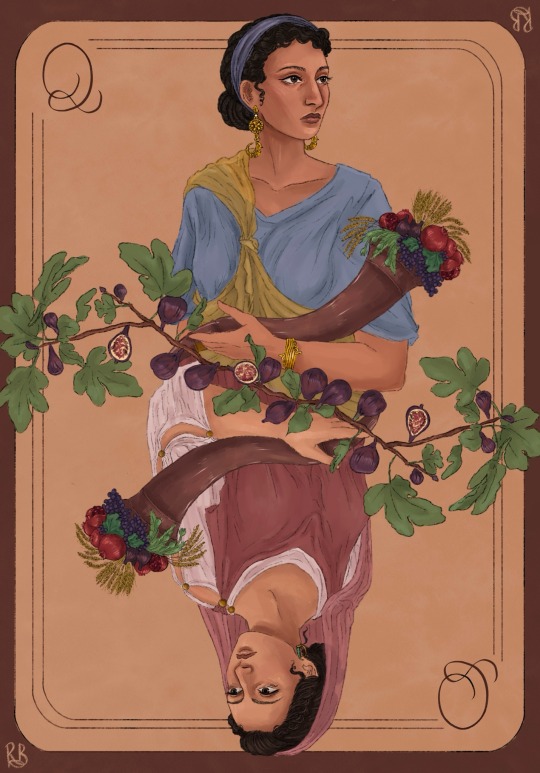

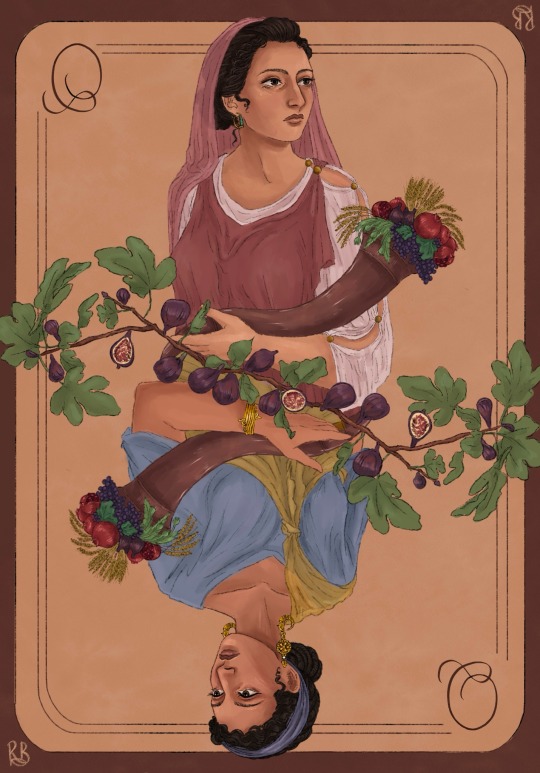

Finals took me out for a bit, but I’m back, and I finally finished!!! Here’s Cleopatra and Livia in all their glory :)

Parallel Lives

To me, Cleopatra VII and Livia Drusilla are two sides of the same coin. They were born exactly ten years apart (Cleopatra in 69 BCE and Livia in 59 BCE), and were the female rulers of two of the most prominent Mediterranean powers of their time. Their families were deeply entwined: Julius Caesar was the father of Cleopatra’s son and Livia’s (adopted) father-in-law; Mark Antony was Livia’s brother-in-law through his marriage to Octavia; when Augustus conquered Egypt, he had Cesarion killed because he was a threat to Augustus’s apparent right to rule.

Both women grew up in a time of civil war and ended up on opposite sides of their families. Cleopatra openly fought her brother Ptolemy XIII and her sister Arinoe VI. Livia’s father and brother died fighting for Brutus and Cassius at Philippi. Her first husband sided with Fulvia and Lucius Antonius when they fought Augustus.

Both of them have been misrepresented by ancient sources and modern media.

Augustus’s propaganda hinged on the presentation of himself as a proper and modest Roman returning to tradition after so much civil war (other than the autocratic ruling ofc). He presented Livia as the ideal and perfect Roman matron, chaste, modest, and pious. He presented Cleopatra as the opposite. She represented the extravagance and backwardness of foreign monarchs. Augustus presented her as domineering over Antony, a reversal of the proper order (his slander of her was largely slander of Antony after all). And although Augustus publicly looked down on Egypt, he adopted many elements of Egyptian monarchy into his dynasty, such as the association of monarchs with gods—as Livia was associated with Ceres, Magna Mater, and Venus, Cleopatra mostly associated herself with Isis (who shares an origin with Venus).

Both were accused by historians of poisoning family members—Cleopatra her brother Ptolemy XIV among others, and Livia Augustus as well as a number of his heirs.

In modern media, Cleopatra is often seen as an over-sexualized seductress, Livia as a conniving and manipulative wife and mother.

Whether or not they did any poisoning, they were both incredibly intelligent and fascinating women and I love both of them a lot.

There are some of motifs in the drawing I want to point out:

- Cleopatra is wearing an Isis knot (the top layer of her dress), a common feature found in depictions of Ptolemaic queens that associates them with the goddess Isis

- She is also wearing a simple cloth diadem as often seen in depictions of Alexander the Great and all the dynasties that emulated him. It’s often seen in Cleopatra VII’s coinage

- She has the melon hairstyle, which she is seen with on coinage and in Roman sculpture. Apparently she popularized it among Roman women when she visited the city!

- Her snake bracelet and bull earrings are also common Ptolemaic motifs

- Livia is dressed like a proper Roman matron in her palla, stola, and tunica. The lack of jewelry is meant to show her modesty as well. Augustus and Livia went out of their way to present as a normal senatorial class couple rather than opulent foreign monarchs

- Her hair is in the iconic nodus style, as seen on basically all her statuary as well as that of other women in Augustus’s household such as Octavia

- Both Livia and Cleopatra are depicted holding cornucopias in their statuary. It associates them with fertility, wealth, and number of mother-goddesses. Pomegranates are a symbol of Juno and Proserpina, wheat and poppy sheafs are associated with Ceres. Wheat is also important because it was a resource Egyptian had in abundance and that Rome was desperate for. A lot of the politics between the two nations were based around that trade.

- And figs. Well, there are a lot of stories that get told about Cleopatra and Livia, many of which paint them with misogynistic stereotypes. Cleopatra’s death has long been the subject of speculation and fantasy. Shakespeare writes that she snuck the snakes she used to commit suicide past the Augustus’s men in a basket of figs. Livia has often been implicated in Augustus’s death. A popular version of that being that she poisoned him with figs. These two women are connected by the imagery and symbolism of the fruit: femininity and fertility, poison and death.

#classicsblr#tagamemnon#augustus#livia drusilla#cleopatra#cleopatra vii#artists on tumblr#my art#digital art#ancient rome#ancient egypt#digital illustration#history#women

110 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fourteen’s wandering an art museum. Managed for a bit to behave like the Good Normal Quiet Thoughtful Art Patron but couldn’t keep it up, so:

Asks an incredible amount of increasingly-detailed questions and has long, in-depth conversations with the attendants.

Spends a ridiculous amount of time in the Van Gogh section just grinning from ear to ear.

There are several incorrectly labeled more ancient art items but for once he keeps his damn mouth shut. They’ll tell Mel later and she’ll get in touch with them

Doesn’t linger very long in the statuary section. There’s nothing obviously suspicious about it, but they’d just rather not.

Pleasantly surprised to come across a few of Clyde Langer’s pieces. The gun in that one looks so familiar, though, one of the must have shown him the painting at some point…

Fiddles with the audio tour headset so much he accidentally breaks it. He’ll fix it before he gives it back, and it’s super weird but that headset never runs out of battery ever again.

Of course they’re going to visit the Little Shop.

#doctor who#fourteenth doctor#what’s fourteen up to#I don’t even really like art museums so idk where this came from#museum attendants as they lock up:#‘hey did you run into That Guy?’#‘the one with the questions? yeah first person ever to let me go on about degas until I actually ran out of things to say’#‘spent twenty minutes asking me about my classes this semester and I think he actually cared?’#shop clerk: ‘well that’s nice because they became a member so they’ll be back’

94 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tomb Chapel of Queen Meresankh III

Meresankh III was one of the most famous Queens in the Old Kingdom of Ancient Egypt. Her grandfather was King Khufu, an important ruler in the 4th Dynasty, who is well known as the builder of the largest pyramid on the Giza plateau.

On April 23, 1927 the tomb was discovered and excavated by George Reisner. with subsequent excavations undertaken by his team on behalf of Harvard University and the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

They found extraordinarily preserved statuary and colorful relief sculpture with a remarkable emphasis on the female figures. Meresankh’s husband, King Khafre, was not shown in the tomb at all. This indicates the importance of female nobility during the queen`s life.

Photo: Sandro Vannini

Read more

68 notes

·

View notes

Text

This was written for Klaroline Fanfic Week @klarolinefanficweek; Week 3 [April 13-April 19, 2025] – Crime.

Forgive Him His Trespasses

She’d been in the city less than a week and already Caroline was breaking and entering. Her sheriff mother would be horrified. But Caroline was exhilarated. From the moment the sexy TA in her Drawing I class at NYU had handed her the course syllabus with his phone number jotted down in an elegant script in red ink along with a beautiful rendering of her swallow tattoo, everything changed. She’d escaped her small town to discover all the beauty the world had to offer and starting with a pair of dimples and a British accent seemed like a good place to start.

Klaus was exciting in a way that went beyond the usual bad boy she went for. There was no leather jacket, but he did have a devilish smirk and an anti-establishment attitude that was immensely appealing for a girl who’d raged against everything her bigoted small town stood for.

“Almost there, love,” he whispered, deftly sliding the thin blade of his pocketknife along the seam of the gate’s security keypad. Moonlight danced among the shadows, highlighting his beautifully sculpted cheekbones and Caroline’s fingers itched for charcoal to commit this exciting, sensual moment to memory.

She was impressed with the skill level he displayed, carefully uncoiling the different colored wires and disconnecting them from each corresponding terminal until the glowing green light behind the keypad went dark. He’s done this before. She had too, but breaking into the principal’s office or city hall’s trophy case was just silly high school pranks — rewiring a sophisticated alarm system for a sprawling estate was next-level badness. And she was all in.

The hollow noise of tumblers releasing caught her attention and Klaus pushed the iron gate open with a knowing smirk. “After you,” he challenged with a raised eyebrow.

Did he seriously think she’d back out? Scoffing, she carefully slid past him, sticking to the shadows the high stone walls cast among the manicured lawn. Eyeing the ivy-bedecked red brick and white marble columns in the distance, she snorted, “No one should hoard this much for themselves.” Nodding at the overdone architectural monstrosity, she added, “That’s bigger than my hometown’s city hall and high school put together. That kind of money could change so many lives, but instead they decided to build this tacky, godawful thing that would make the Real Housewives feel at home.”

“Yeah, rich people are...bloody awful,” he muttered, rushing her past a gemstone-encrusted mosaic with a gold leaf ‘M’ emblazoned in the middle. “But they do have their uses,” he amended, opening another wrought iron gate full of heavy scrollwork with a charming flourish of his well-toned arms.

“What uses,” Caroline asked skeptically, stepping past a row of wolf-shaped topiaries and letting out a gasp of unexpected delight. Ancient Greek and Roman statuary were posed throughout the elaborate rose garden. And even to her inexperienced freshman art student’s eye, she could tell they weren’t reproductions.

Klaus seemed to take delight in her stunned expression, leading her to a row of exquisitely carved statues as though he was a museum docent. “These are Roman copies of Greek works including the Three Graces and Eirene. Note the extraordinary lines these ancient sculptors were able to achieve with the most rudimentary of tools.”

“This is why you brought me here,” she asked in a tone of hushed reverence, exhilarated at being so close to so many artistic triumphs. If only she’d brought her sketchpad, she thought wistfully.

As though reading her mind, Klaus reached into his canvas messenger bag and handed her a sketchpad with an impish wink. Together, they moved to a gazebo positioned in the center of the garden and sat down to enthusiastically sketch by moonlight.

“This is unreal,” she whispered, an edge to her tone as she added, “Imagine growing up in a place like this where beauty is hidden from everyone except the spoiled, privileged few.” Pointing at what looked like another version of the Discus Thrower, she spat, “These belong in a museum.”

Klaus glanced up from his sketching, an unreadable expression on his face as he agreed with a hint of disgust, “Indeed they do. The owner of this ghastly estate bribed and threatened the curators and museum boards and whoever else he needed to obtain these priceless works of art from the Met, The Louvre, the British Museum, and any other corrupt institution willing to cater to his whims. Many famous pieces you can name actually are clever reproductions to cover up the greed of the shamelessly wealthy.”

Caroline was drawn to the fierce anger she saw in Klaus’ face, thrilled to have found someone whose righteous indignation matched her own. Threading her fingers through his, she chuckled darkly, “I don’t know why I’m surprised. Every day it seems like there’s some new, awful reality these people inflict on society.”

“Eat the rich,” he muttered with a grimace.

“Eat the rich,” she agreed, never realizing how absurdly hot that phrase made her as she pulled Klaus in for a thoroughly filthy kiss.

Their sketchpads fell to the stone floor of the gazebo with a clatter, Caroline hitching up the ragged hem of her jean skirt to straddle Klaus’ lap. She ground down on the generous bulge she found there until they both moaned.

He pulled back from their kiss to mumble against her lips, “I’m supposed to be teaching you proper shading techniques.”

“Mmm,” she groaned, playfully biting down on his earlobe. “I’m looking forward to you teaching me all sorts of techniques.”

Klaus seemed to abandon all objections as soon as she ripped off her thin tank top, her breasts spilling out of her favorite lacey pink bra. He was working the front clasp with clumsy fingers and Caroline was certain he’d resort to his teeth next.

A throat clearing on the steps of the gazebo made them both jump, stumbling into each other as they squinted at a blinding flashlight beam that was aimed at them. Squinting, Caroline could make out an imposing man with distinguished gray at his temples, dressed in what appeared to be a really expensive three-piece suit.

“Niklaus,” he sternly reprimanded. “Explain yourself now.”

Confused, Caroline stared at Klaus, whose gaze was determinedly staring at everything except her. Letting out an irritated, defeated sigh, he answered, “Hello, Father.”

#klarolinefanficweek#uppitybitch fanfic#klaroline fanfic#klaroline#klaroline does breaking and entering#week 3 crime

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

The quotes in the "Views within the industry" section of the Homosexuality in the Batman franchise Wikipedia article are comedy gold.

(The following are paraphrased for comedic effect, but only slightly.)

Alan Grant: I didn't write Batman as gay, Denny O'Neil didn't write Batman as gay, Marv Wolfman didn't write Batman as gay, no one going all the way back to Bob Kane has ever written Batman as gay. Well, except Joel Schumacher.

Devin Grayson: I don't think of Batman as gay, but I can definitely see where people are coming from.

Frank Miller: Batman isn't gay, unfortunately. It would be so much healthier if he were.

Joel Schumacher: I added nipples to the Batsuit as an homage to ancient Greek statuary, I don't understand why everyone got so worked up over it. And I gave Robin an enormous codpiece because... shut up.

Grant Morrison: The concept of Batman has incredible gay potential, but the actual character isn't gay because he has no sex life. No, I still haven't read Son of the Demon, why do you ask?

George Clooney: Batman wasn't gay until I made him gay.

21 notes

·

View notes