#also like if you are actually a marxist you know that the distinction should be made along the lines of class

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

If you say that shit in his chat he's like "no you guys I'm rich. You're being stupid" he is very frank about it

remember when that ('communist'? idk, I never watched him) streamer Hasan bought a 1.5 million dollar house in the hollywood hills and there were a bunch of people going 'nooooo hes not rich thats just how much it costs to buy a family house in that area the cost of livingggg'? people whose conception of anticapitalist politics comes down to 'theres like 20 people who are Evil cronies and if we kill them everything becomes fine' get really really defensive when you imply they themselves might be rich

#also like if you are actually a marxist you know that the distinction should be made along the lines of class#as in: are you rich from being paid for your labor? (actors/athletes/those paid a high salary at a company they dont own)#and those who are rich from owning /the means of production/ (company owners/investors)#bonus: petit bourgeois are those who own the means of production but are not very wealthy (small business with worker-owner)#the tags dont really agree grammatically but i cant fix them tbh

2K notes

·

View notes

Note

IMO, I don’t think A stans who attack Sansa for her classism truly cares about it. I mean, they want A to be queen/lady (and there’s nothing wrong with wanting that) but such an ending would only be reinforcing the structure they’re critising.

And it’s great and important that A plays with lowborn children and tried to defend Mycah but that doesn’t make her a marxist revolutionary lol, it doesn’t erase her own classism. All nobles are classist, a few of them bother to treat peasants relatively well (the Starks, Edmure, etc) but that unfair system still exists. You can’t have nobility without inequality.

And I'll paste this one in too:

Unpopular opinion but if Arya’s stans genuinely believed in her as someone who isn’t classist, they would imagine her leading a social revolution that topples and destroy feudalism. Not someone who serves the conception of hereditary monarchy, serfdom (despite treating them with humanity), hierarchical social categories, etc. Arya as QITN would be a reformist, not a revolutionnary.

(These are so old, I can’t remember which post prompted them, apologies!)

So, I never thought more than being a good leader within the system was a possibility? During GoT they played up this idea that Dany was gonna change the system, "break the wheel," but that was mainly to hide the fact that going to war for a crown was a selfish thing to do, that she wasn't a hero for choosing that path. Considering how Martin has written about the tragedy of the Starks losing Winterfell, the little boys being chased from their home, I never imagined that his ending would involve a king or queen turning around and doing that to another noble child? IMO, there was never going to be any seizing and divvying up wealth.

In ASOIAF, it seems like the focus is much more on having a leader who will be capable of maintaining peace and delivering justice and taking care of some practical concerns. It never even occurred to me to expect an end to feudalism? So, yeah, I would agree that the most anyone could be was a reformist, but I didn't even think that was the idea (in the way fans would mean it) that Martin was tracking. It didn't seem to me that he was gonna do away with nobles, only that he was saying a good noble won't allow his smallfolk to be mistreated and wouldn't ruin their lives for the sake of a crown. I thought that's where the Robb criticism comes in. Robb should have chosen peace, not more fighting.

I also thought the good noble was being presented with Ned. Protect the vulnerable, be horrified by the death of the innocent, adhere to these personal values even when they are in defiance of what your world demands, even when it means betrayal of a "brother" or treason against your king. Obviously, Ned fell short of the ideal, but that's why his children will rise to power, because they have the same core values that Martin wants us to look at as good.

Personally, I think Arya being rebellious and kicking against the rules that annoy her is fun? My little sister was a tomboy, and I have sympathy for Sansa, but I'm amused by Arya. However, I do not attribute as much, uh, let's say, virtue to her behavior as others do. Nor do I attach the same amount of condemnation to Sansa (who recognizes class distinctions) that others do. To me, Martin used the Trident incident to illustrate how the class differences worked because it's a grievance of his that writers ignore them:

And that’s another of my pet peeves about fantasies. The bad authors adopt the class structures of the Middle Ages; where you had the royalty and then you had the nobility and you had the merchant class and then you have the peasants and so forth. But they don’t’ seem to realize what it actually meant. They have scenes where the spunky peasant girl tells off the pretty prince. The pretty prince would have raped the spunky peasant girl. He would have put her in the stocks and then had garbage thrown at her. You know. I mean, the class structures in places like this had teeth. They had consequences. And people were brought up from their childhood to know their place and to know that duties of their class and the privileges of their class. It was always a source of friction when someone got outside of that thing. And I tried to reflect that. (link)

With that in mind, I thought Martin wanted to impress upon the reader the severity of what the hierarchy meant, the prince can do whatever the hell he wants, the noble kid is in danger of being punished (Arya might have lost a hand, Sansa loses Lady), Mycah is killed. We were meant to understand, this world isn't ours. Arya in an important way, didn't understand how the world worked, not really, which is a tool the author was using, her grief and horror, to guide us through learning about station in ASOIAF. We needed to see and feel the disparity.

Obviously, Martin doesn't think that's a good system, but the author slapping us in the face with, “this is horrible but this is the way it is” doesn’t mean we’re to expect a total transformation of Westeros as a whole in the last few chapters of the final book. Martin wants to have some verisimilitude to (his perception of) medieval times, so imo, the idea was never turning Westeros on its head, but for people who cared to end up in control and be better. Not like a modern anarchist, but be good within the confines of that world.

Anyway, because of how many Arya fans hate Sansa/Sansa fans, I never did much with that side of the fandom, but I never had the impression they truly thought anyone would be revolutionizing things. It seemed to me that they believed her ending up QitN was revolutionary not in the sense that she would upend the system, but to them, having a girl who rejected societal norms come out on top felt like an important rejection of a traditional princess “winning.” I assume that's why so much of their focus is on Sansa and how she ruined Arya's life even though she and Arya have been separated for books. It isn't so much what the particular character will do as a leader, which theme is upheld by them ending up in a position of leadership, the "revolutionary" bit is determined by defiance of (what they believe are) genre norms, not societal overhaul on the page.

Now, if we accept that a total societal revolution is off the table in ASOIAF, and knowing that Martin opposes violence pretty vehemently, isn't in favor of imposing your will through violent means, how can someone who rejects society encourage gradual improvement? Wouldn't the "realism" Martin wants be found in a person, who say, can function really, really well within the structure of society but cares enough to try to make things better for others? Someone who can change it all from within because their societal position confers a certain amount of power, but also, they have a notable ability to win admiration, even when it is begrudgingly given? Someone whose compassion, even for enemies, is highlighted? Isn’t that someone who would be able to gradually bring about the kind of realistic change Martin would permit in his world?

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

Biden addressed the Gaza protests. I haven't watched the full address yet, but apparently he said the expected things, ie asserting the right to peaceful protest, while also insisting on the rule of law. So far so good, as President it's his responsibility to uphold both.

I do think he erred in not specifically addressing the violence against Gaza protesters at UCLA, as President he must uphold the rule of law for everyone, regardless of which side they're on.

That said, I think Biden's mostly hands-off approach to the protests and responses to them may actually be a good thing. I'm sure Republicans desperately want a Federal military/National Guard crackdown on the protests- they will play this as being "pro-Israel" and "pro-rule of law", but they likely know that any violence will ultimately be blamed on Biden, and can be more easily blamed directly on him if he orders the National Guard in. Their dream is a Kent State before the election, to break off young and progressive voters*, and get them engaging in street violence that the fascist Right can then use to justify a violent crackdown, and as Whataboutism to deflect from and excuse their own planned post-election violence.

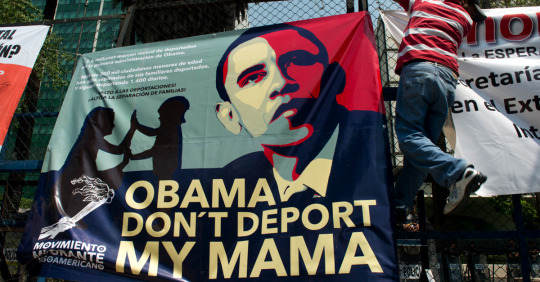

So far, Biden isn't taking the bait. And by keeping mostly hands-off, he is drawing a clear distinction between himself and Trump. Because I trust we all remember how Trump handled the Black Lives Matter protests in the months before the election in 2020 (and if you don't, you really should): He suggested shooting protesters, sent secret police to Democratic areas to grab people off the streets, and used the military to clear out protesters in DC ahead of a photo-op- when he wasn't cowering in the White House bunker.

Once again, Biden's response may be lacking in some respects, but it is WORLDS better than what Trump offers. Except, of course, for Republicans, who was violent unrest to damage Biden, and Leftist/anarchist "accelerationists", who want to maximize violence because they believe it will lead to a Marxist revolution*, instead of the more likely prolonged civil war or fascist dictatorship.

Edit: Think I'm kidding about this? The fascist Right is VERY actively trying to recruit and co-opt the radical Left. If I didn't know that before, the sight of "Communists for Trump" stickers (including one of Marx wearing a MAGA hat) defacing a bus stop in my CANADIAN home town last night would be proof enough.

#US#Election#Politics#2024#2020#Gaza#Israel#Palestine#Black Lives Matter#Protest#Civil Unrest#Kent State#Trump#Biden

9 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hey, I was wondering if you happen to have any sources that detail what in the hell is up with the history of "queer theory".

I'm a bisexual man in my 20's who grew up in a religious cult in the mid/southwest US, and so—as you can imagine—ignorant people who claim "queer isn't a slur" drive me up the goddamn wall. The fact people have the gall to say that to begin with tells me so much about how they must have grown up and currently live.

I have always hated the popularization of "Queer Studies/Queer History" and "Queer Theory" (and "The Queer Community", of course). The information you provided in your reblog of that user's post cemented my hatred for those terms, but I hadn't heard anything about their origins before. I'd deeply appreciate some sources for your claims or a point in the right direction to find out more about this because...I am now very intrigued.

I’m in a similar boat actually, as an LGBT southerner. I’ve never been in as severe a situation, but I absolutely understand where you’re coming from. I never heard the word used kindly until I went to college and even then…. It was very overly academic virtue signaling or clinical I guess.

As for queer theory, the godparents of the subject, Micheal Foucault and Judith Butler are both their own cans of worms and can be dug into at a later date.

However, the woman who coined queer studies as a term (as well as “homosocial”), Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick had a fixation on male/male relationships and insisted that male friendships had sexual elements. See: her whole career.

Queer theory was credited as being coined by Teresa De Lauretis, who was a contemporary of Foucault, founder of postmodernism and known pedophile. Her original theory is different from the way it is used currently, as it focused on opposing heteronormativity, a distinction between lesbian and gay studies, and focused on the racial bias of sexual preferences. All very fun stuff. Like all critical theory and postmodernism, it is Marxist and annoying.

Queer theory as we know it is very Marxist in the same way because of its inextricable roots and it’s core is subversive and assumes all subversion to be positive. It also takes the social construct approach to all things, including gender, sexuality, and consent. It also assumes because of its Marxist framework that there must always be an oppressed/oppressor divide.

The unfortunate issue with pulling up sources for a lot of this stuff is also because it is a critical theory, which is overly academic for the purposes of obfuscation because if they were to tell you outright that they’re seeking to upset and subvert all social norms of gender and sexuality you’d sure have some questions as to the specifics of that. I would have to wade through heap of essays from these people that I simply do not have the time for at the moment.

A few specifics however are of Gayle Rubin, writer of one of the founding essays of queer theory, who both wrote that gender is socially imposed and that we should seek a gender less society, despite the inherent impossibility of that aspiration, and defended pedophilic practices frequently in her most famous work Thinking Sex: Notes for a Radical Theory of the Politics of Sexuality.

Pat Califia, another big name in the area of queer theory and queer studies published an article in and voiced explicit support of the pedophilic publication Paidika, while simultaneously criticizing federal anti CP/CSEM laws, claiming that the laws “targeted gay men.” He also defended public sex in his essay, Public Sex: The Culture of Radical Sex, where he referred to young questioning men as “young faggots.”

Allen Ginsberg and Micheal Foucault were both active pedophile rapists who targeted young boys and were prominent figures in the queer theory and postmodernism movements, with the former being a literal member of NAMBLA and the latter advocating for the abolishment of age of consent laws and reportedly abusing many boys in Tunisia.

Judith Butler, another prominent figure and someone I even read and analyzed a handful of essays by in college classes, defended incest, claimed that gender is simply performative and a series of behaviors. This is all in her essay Gender Trouble: Gender Identity and the Subversive of Identity. She also claimed that we “need to rethink the category of woman” because of her own apparent insecurities with her gender expression, seeing as she now claims to be nonbinary. She also has referred to LGBT people as “queers” so there’s also that.

I posted this video a while back that goes into some specifics. And honestly this is just the tip of the iceberg.

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

my no. 1 pet peeve use case with this is the discourse around the phrase “emotional labor.” i don’t think you need to read the managed heart to be a leftist. i don’t think you need to read the managed heart to say you’re emotionally drained from doing something emotionally taxing. i don’t even think you need to read the managed heart to understand why customer service work is so soul-eating.

but if you are going to go around “educating” other people about emotional labor and “correcting” people who use it wrong and generally chasing clout by setting yourself up as a person whomst knows what emotional labor is… you should fucking read the managed heart.

and if you want to learn about emotional labor and what it is, your best resource is reading the managed heart, not a smug internet explainer by someone who hasn’t read the managed heart either.

and no, that Atlantic interview with Arlie Russel Hochschild isn’t a good substitute for reading the book either—not because it’s too short, but because the Atlantic as an institution has specific ideological commitments that prevent it from actually explaining the term. Hochschild’s distinction between “emotion work” and “emotional labor” is based in Marxist terminology, and it is unthinkable for the Atlantic to explain that to its readers, so it sort of weirdly dances around it and now the main source of “I did totally read Hochschild about emotional labor!” from people who haven’t read The Managed Heart is hopelessly confused.

Anyway here is a screenshot of the definition from the book. It actually is pretty short but that’s because it’s willing to use terms like “exchange value” in the definition. If you want to know more I suggest checking out the book itself.

Don’t want to read the book? That’s fine, you can also abstain from portraying yourself as an expert on the theory of emotional labor. But this current state of the discourse, where everyone has to say “emotional labor” a lot to signal how progressive they are, but the idea that they might want to learn what the word means before using it is inexcusable ableist gatekeeping elitism how dare you, is untenable.

at some point you have to realize that you actually have to read to understand the nuance of anything. we as a society are obsessed with summarization, likely as a result of the speed demanded by capital. from headlines to social media (twitter being especially egregious with the character limit), people take in fragments of knowledge and run with them, twisting their meaning into a kaleidoscope that dilutes the message into nothing. yes, brevity is good, but sometimes the message, even when communicated with utmost brevity, requires a 300 page book. sorry.

141K notes

·

View notes

Note

I’m starting grad school this autumn and honestly I’m getting nervous. Like yes I am v excited about the whole prospect overall and I do miss being a student but am intimidated by 3 hr long seminars and thesis writing and massive amounts of reading… everyone keeps saying it’s gonna be very different from undergrad so okay, but how specifically? Is it the large amounts of reading? I already had insane amounts of reading (humanities degree hurrah) especially in my last two years but could you expound on your own experience and how you take notes/read quickly/summarize or just how to deal with first time grad students?

Oh, yeah for sure! A necessary disclaimer here is that I'm at a certain poncy English institution that is noted for being very bad at communicating with its students and very bad at treating its postgrad students like human beings, so a lot of these strategies I've picked up will be overkill for anyone who has the good sense to go somewhere not profoundly evil lol.

So I'll just preface this by saying that I am a very poor student in terms of doing what you're supposed to. I'm very bad at taking notes, I never learned how to do it properly, and I really, really struggle with reading dense literature. That said, I'm probably (hopefully?) going to get through this dumb degree just fine. Also — my programme is a research MPhil, not taught, so it's a teensy bit more airy-fairy in terms of structure. I had two classes in Michaelmas term, both were once a week for two hours each; two in Lent, one was two hours weekly, the other two hours biweekly; and no classes at all in Easter. I also have no exam component, I was/am assessed entirely on three essays (accounting for 30% of my overall mark) and my dissertation (the remaining 70%), which is, I think, a little different to how some other programmes are. I think even some of the other MPhils here are more strenuous than that, like Econ and Soc Hist is like 100% dissertation? Anyways, not super important, but knowing what you're getting marked on is important. I dedicated considerably less time than I did in undergrad to perfecting my coursework essays because they just don't hold as much weight now. The difference between a 68 and a 70 just wasn't worth the fuss for me, which helped keep me sane-ish.

The best advice anyone ever gave me was that, whereas an undergrad degree can kind of take over your life without it becoming a problem, you need to treat grad school like a job. That's not because it's more 'serious' or whatever, but because if you don't set a really strict schedule and keep to it, you'll burn yourself out and generally make your life miserable. Before I went back on my ADD meds at the end of Michaelmas term, I sat myself down at my desk and worked from 11sh to 1800ish every day. Now that I'm medicated, I do like 9:30-10ish to 1800-1900 (except for now that I'm crunching on my diss, where, because of my piss-poor time management skills I'm stuck doing, like, 9:30-22:30-23:00). If you do M-F 9-5, you'll be getting through an enormous amount of work and leaving yourself loads of time to still be a human being on the edges. That'll be the difference between becoming a postgrad zombie and a person who did postgrad. I am a postgrad zombie. You do not want to be like me.

The 'work' element of your days can really vary. It's not like I was actually consistently reading for all that time — my brain would have literally melted right out of my ears — but it was about setting the routine and the expectation of dedicating a certain, consistent and routinized period of time for focusing on the degree work every day. My attention span, even when I'm medicated, is garbage, so I would usually read for two or three hours, then either work on the more practical elements of essay planning, answer emails, or plot out the early stages of my research.

In the first term/semester/whatever, lots of people who are planning on going right into a PhD take the time to set up their applications and proposals. I fully intended on doing a PhD right after the MPhil, but the funding as an international student trying to deal with the pandemic proved super problematic, and I realised that the toll it was taking on my mental health was just so not worth it, so I've chosen to postpone a few years. You'll feel a big ol' amount of pressure to go into a PhD during your first time. Unless you're super committed to doing it, just try and tune it out as much as you can. There's absolutely nothing wrong with taking a year (or two, or three, or ten) out, especially given the insane conditions we're all operating under right now.

I'll be honest with you, I was a phenomenally lazy undergrad. It was only by the grace of god and being a hard-headed Marxist that I managed to pull out a first at the eleventh hour. So the difference between UG and PG has been quite stark for me. I've actually had to do the reading this year, not just because they're more specialised and relevant to my research or whatever, but because, unlike in UG, the people in the programme are here because they're genuinely interested (and not because it's an economic necessity) and they don't want to waste their time listening to people who haven't done the reading.

I am also a really bad reader. Maybe it's partially the ADD + dyslexia, but mostly it's because I just haven't practiced it and never put in the requisite effort to learn how to do it properly. My two big pointers here are learning how to skim, and learning how to prioritise your reading.

This OpenU primer on skimming is a bit condescending in its simplicity, but it gets the point across well. You're going to want to skim oh, say, 90% of the reading you're assigned. This is not me encouraging you to be lazy, it's me being honest. Not every word of every published article or book is worth reading. The vast majority of them aren't. That doesn't mean the things that those texts are arguing for aren't worth reading, it just means that every stupid rhetorical flourish included by bored academics hoping for job security and/or funding and/or awards isn't worth your precious and scarce time. Make sure you get the main thrust of each text, make sure you pull out and note down one or two case studies and move right the hell on. There will be some authors whose writing will be excellent, and who you will want to read all of. Everything else gets skimmed.

Prioritisation is the other big thing. You're going to have shitty weeks, you're probably going to have lots of them. First off, you're going to need to forgive yourself for those now — everybody has them, yes, even the people who graduated with distinctions and go on to get lovely £100,000 AHRC scholarships. Acknowledge that there will be horrible weeks, accept it now, and then strategise for how to get ahead of them. My personal strategy is to plan out what I'm trying to get out of each course I take, and then focus only on the readings that relate to that topic.

I took a course in Lent term that dealt with race and empire in Britain between 1607 and 1900; I'm a researcher of the Scottish far left from 1968-present, so the overlap wasn't significant. But I decided from the very first day of the course that I was there to get a better grasp about the racial theories of capitalism and the role of racial othering in Britain's subjugation of Ireland. Those things are helpful to me because white supremacist capitalism comes up hourly in my work on the far left, and because the relationship of the Scottish far left to Ireland is extremely important to its self definition. On weeks when I couldn't handle anything else, I just read the texts related to that. And it was fine, I did fine, I got my stupid 2:1 on the final essay, and I came out of it not too burnt out to work on my dissertation.

Here is where I encourage you to learn from my mistakes: get yourself a decent group of people who you can have in depth conversations about the material with. I was an asshole who decided I didn't need to do that with any posh C*mbr*dge twats, and I have now condemned myself to babbling incomprehensible nonsense at my partner because I don't have anyone on my course to work through my ideas with. These degrees are best experienced when they're experienced socially. In recent years (accelerated by the pandemic, ofc), universities have de-emphasised the social component of postgrad work, largely to do with stupid, long-winded stuff related to postgrad union organising etc. It's a real shame because postgrads end up feeling quite socially isolated, and because they're not having these fun and challenging conversations, their work actually suffers in the long term. This is, and I cannot stress this enough, the biggest departure from undergrad. Even the 'weak links' or whatever judgemental nonsense are there because they want to be. That is going to be your biggest asset. Talk, talk, talk. Listen, listen, listen. Offer to proofread people's papers so you get a sense of how people are thinking about things, what sort of style they're writing in, what sources they're referring to. Be a sponge and a copycat (but don't get done for plagiarism, copy like this.) Also: ask questions that seem dumb. For each of your classes, ask your tutors/lecturers who they think the most important names in their discipline are. It sounds silly, but it's really helpful to know the intellectual landscape you're dealing with, and it means you know whose work you can go running to if you get lost or tangled up during essay or dissertation writing!

You should also be really honest about everything — another piece of advice that I didn't follow and am now suffering for. The people on your courses and in your cohort are there for the same reasons as you, have more or less the same qualifications as you, and are probably going to have a lot of the same questions and insecurities as you. If you hear an unfamiliar term being used in a seminar, just speak up and ask about it, because there're going to be loads of other people wondering too. But you should also cultivate quite a transparent relationship with your supervisor. I was really cagey and guarded with mine because my hella imposter syndrome told me she was gonna throw my ass out of the programme if I admitted to my problems. Turns out no, she wouldn't, and that actually she's been a super good advocate for me. If you feel your motivation slipping or if you feel like you're facing challenges you could do with a little extra support on, go right to your supervisor. Not only is that what they're there to do, they've also done this exact experience before and are going to be way more sympathetic and aware of the realities of it than, say, the uni counselling service or whatever.

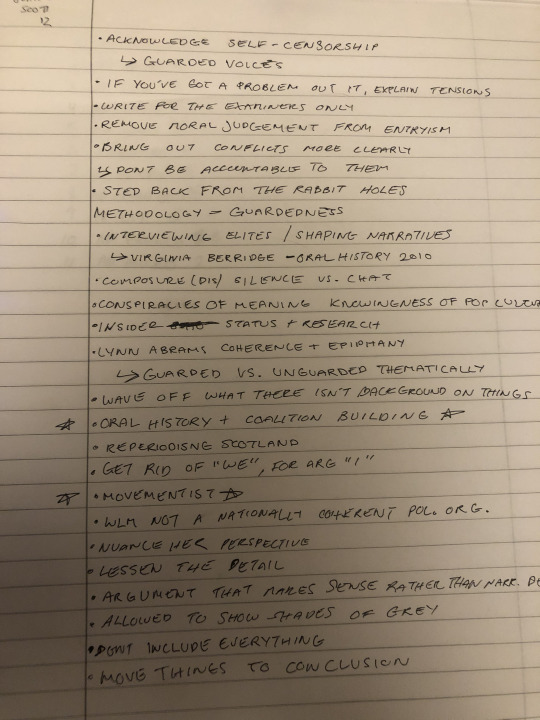

Yeah so I gotta circle back to the notes thing... I really do not take notes. It's my worst habit. Here's an example of the notes I took for my most recent meeting with my supervisor (revising a chapter draft).

No sane person would ever look at these and think this is a system worth replicating lol. But the reason they work for me is because I also record (with permission) absolutely everything. My mobile is like 90% audio recordings of meetings and seminars lol. So these notes aren't 'good' notes, but they're effective for recalling major points in the audio recording so I can listen to what was said when I need to.

Sorry none of this is remotely organised because it's like 2330 here and my brain is so soft and mushy. I'm literally just writing things as I remember them.

Right, so: theory is a big thing. Lots of people cheap out on this and it's to their own detriment. You say you're doing humanities, and tbh, most of the theory involved on the humanities side of the bridge is interdisciplinary anyways, so I'm just gonna give you some recommendations. The big thing is to read these things and try to apply them to what you're writing about. This sounds so fucking condescending but getting, like, one or two good theoretical frameworks in your papers will actually put you leaps and bounds beyond the students around you and really improve your research when the time comes. Also: don't read any of these recommendations without first watching, like an intro youtube video or listening to a podcast. The purists will tell you that's the wrong way to do it, but I am a lazy person and lazy people always find the efficient ways to do things, so I will tell the purists to go right to hell.

Check out these impenetrable motherfuckers (just one or two will take your work from great to excellent, so don't feel obliged to dig into them all):

Karl Marx and Fredrich Engels (I'm not just pushing my politics, but also, I totally am) — don't fucking read Capital unless you're committed to it. Oh my god don't put yourself through that unless you really have to. Try, like, the 18th Brumaire of Louis Napoleon for the fun quotes, and Engels on the family.

Frantz Fanon — Wretched of the Earth. Black Skin White Masks also good, slightly more impossible to read

Benedict Anderson — Imagined Communities. It's about nationalism, but you will be surprised at how applicable it is to... so many other topics

Judith Butler — she really sucks to read. I love her. But she sucks to read. If you do manage to read her though, your profs will love you because like 90% of the people who say they've read her are lying

Bourdieu — Distinction is good for a lot of things, but especially for introducing the idea of social and cultural capital. There's basically no humanities sub-discipline that can't run for miles on that alone.

Crenshaw — the genesis of intersectionality. But, like, actually read her, not the ingrates who came after her and defanged intersectionality into, like, rainbow bombs dropped over Gaza.

The other thing is that you should read for fun. My programme director was absolutely insistent that we all continue to read for pleasure while we did this degree, not just because it's good for destressing, but because keeping your cultural horizons open actually makes your writing better and more interesting. I literally read LOTR for the first time in, like February, and the difference in my writing and thinking from before and after is tangible, because not only did it give me something fun to think about when I was getting stressy, but it also opened up lots of fun avenues for thought that weren't there before. I read LOTR and wanted to find out more about English Catholics in WWI, and lo and behold something I read about it totally changed how I did my dissertation work. Or, like, a girl on my course who read the Odyssey over Christmas Break and then started asking loads of questions about the role of narrative creation in the archival material she was using. It was seriously such a good edict from our director.

Also, oh my god, if you do nothing else, please take this bit seriously: forgive yourself for the bad days. The pressure in postgrad is fucking unreal. Nobody, nobody is operating at 100% 100% of the time. If you aim for 60% for 80% of the time and only actually achieve 40% for 60% of the time, you will still be doing really fucking well. Don't beat yourself up unnecessarily. Don't make yourself feel bad because you're not churning out publishable material every single day. Some days you just need to lie on the couch, order takeout, and watch 12 hours of Jeopardy or whatever, and I promise you that that is a good and worthwhile thing to do. You don't learn and grow without rest, so forgive yourself for the moments and days of unplanned rest, and forgive yourself for when you don't score as highly as you want to, and forgive yourself when you say stupid things in class or don't do all of (or any of) the class reading.

Uhhhh I think I'm starting to lose the plot a bit now. Honestly, just ping me whatever questions you have and I'm happy to answer them. There's a chance I'll be slower to respond over the next few days because my dissertation is due in a week (holy fuck!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!) but I will definitely respond. And honestly, no question is too dumb lol. I wish I'd been able to ask someone about things like what citation management software is best or how to set up a desk for maximum efficiency or whatever, but I was a scaredy-cat about it and didn't. So yeah, ask away and I will totally answer.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

sometimes I think a lot of the discourse around microlabels is dumb as hell and sometimes I think it's incredibly important because like, on one hand, someone who self-describes as an ecosocialist and someone who self-describes as an anarchocommunalist probably overlap so broadly that you're doing more work to differentiate them than it's probably worth for anyone who's not built their identity around being elitist, and 90% of the time you won't even know what the hell someone means when they call themselves a posadist unless you're already terminally involved, and even if you do know, it's like, there're already other identities that are inclusive of what you're describing and it feels like you're splitting hairs here for no reason

and on the other hand, if someone self-describes as a marxist-leninist-maoist, i IMMEDIATELY have some questions regarding their political and ethical stances that need to be resolved because hyperspecific portions of people who identify that way are batshit crazy and should be avoided on sight (shoutout to the austin/kansas red guards)

and this goes more or less the exact same for sexuality/gender microlabels as well (gotta love people who try to legislate new sexualities for the purpose of excluding trans folks, or to create distinctions that never existed originally and thus fracture the community as people try to figure out what the fuckin' difference actually is)

basically at the end of the day, it's frustrating because like, microlabels can be incredibly useful as a way to very quickly learn a lot about someone, both positive and negative, as I think they're intended to be, but also like, if you tell me you're an apothisexual demigirl, I'm gonna need so much of an explanation that you're probably doing more work to isolate yourself than you are to actually making your identity distinct

and generally you have to, again, be more or less terminally involved in order to know why the distinction matters or what niche idiots rest within each microlabel

#i don't blame people for wanting to find something that accurately describes themselves#but like. you can't expect people to know it offhand so it's almost not worth knowing the specific microlabel#and likely each microlabel has some shithead that gives it a bad name#most mlms are probably very reasonable people nowhere near the destructive stupidity of the red guards#but now I gotta fuckin' check

1 note

·

View note

Note

Why were so many of the early Soviet Communists Jews?

I can’t tell this is a genuine historical question or an antisemitic conspiracy theory so i’m going to assume...both? If this was meant in good faith i’m sorry and if it was not, fuck off the Holocaust actually happened.

Ok so first off, their is a very long history of autocratic rulers linking people they don’t like to Jews, due to the wide spread antisemitic attitudes in Europe throughout history (including today). It actually provided an easy scapegoat for the regimes problems, especially monarchies, because it helped explain a flaw in their logic. Monarchs argue that the natural state of being is a triangle which involves god appointing a monarch who rule over the people, who are naturally happier being subservient. This gets worse with the Nazis, who worked very hard to link Communism with Judaism, since they blamed basically everything wrong with the modern world on the Jews

The ultimately example of this is in the Tsarist regime itself, because the Elders of Zion, the unholy grail of antisemitic conspiracy theories which is a supposed transcript of a meeting of Jews who secretly control the world. The book was written by the Tsarist secret service to try to discourse the people from revolution by blaming all of Russia’s problem not on the incompetence of the autocracy but instead on the Jews who people in Russia never liked anyways. In fact in the book there are some really ham handed bits where they are like “The only people who can stop our Jewish plot is the good Christian Tsar who is so cool and sexy and strong omg, I sure hope that the Russian people aren’t loyal to him”. So yet another reason to hate the Tsar.

So while there were many Jewish communists, the Communist movement as a whole was not Jewish, it was majority Gentile and as we see once they take power, had some pretty anti Jewish attitudes themselves. Even Marx, who was ethnically but not religiously/culturally jewish, had some pretty nasty views of Jewish, though not on racial lines. And be wary of anybody who works too hard to link Judaism and Communism, because they are likely influenced by some Neo Nazi ideas.

As to why Jews would want to be communists....well disclaimer a lot of Jews weren’t communists, in fact many of them were quite opposed to communism, either because they were traditionalists religious types, nationalist zionists types, or liberal capitalist types. Within the Russian Jewish community there were a wide variety of opinions and beliefs, as there have always been (insert obvious joke about Jewish family’s always arguing here).

However there are a few reasons why so many of the early Communists were Jewish, even if the majority were not.

1) Tsarist russia was extremely antisemitic and regularly targeted jews for harassment, discrimination, or death even when we don’t take the Pogroms into account, so it shouldn’t be surprisingly that many Jews were more than happy to see the Tsarist state collapse. In 1891, all Jews were expelled from Moscow, which lead to many Jewish families to become extremely (rightfully) embittered towards the Tsar. And for many Jews, communism seemed especially appealing since it offered to ignore any distinction based on race or background in favor of universal tolerance. This would largely prove to be untrue, as Soviet Russia had plenty of antisemitic attitudes such as the Doctor’s Plot, but certainly nothing on the scale of Tsarist russia and the Pogroms.

2) Many Jews were being blamed for revolutionary activities anyways. When Alexander II was assassinated, the Jews were blamed for the crime despite the assassins being of Catholic and Orthodox background. So for many Jews if you are going to be labeled as a Revolutionary no matter what you do..maybe become a revolutionary.

I mean the Tsarist state never really had the power to back this up, but their long term anti Jewish goals bordered on genocidal

"One third will die out, one third will leave the country and one third will be completely dissolved in the surrounding population" - Konstantin Petrovich Pebedonostsev,

3) The Jewish communities in Russia were fairly insular and self contained so they were actually somewhat protected from the Tsarist secret police. After all, it is a lot easier to plant spies or get informants if you don’t know anybody or how the culture works. And since the Tsarists secret police tended to be...really really antisemitic it should come as no surprise that these secret police didn’t really know to navigate Jewish culture

4) Similarly, the Jewish population largely spoke Yiddish and how many Tsarist secret police agents speak Yiddish. THe fact that they literally couldn’t spy on the Jewish communities meant that Communist Jews tended to do fairly well.

5) Also traditionally the Jewish community tended to be highly educated and that meant that many of them had access to Marxist writings and the training to understand them.

Again though, the Soviet Union was by no means controlled by Jewish leaders, you wouldn’t get antisemitic leaders like Stalin or Khrushchev if it had been.

#Ask EvilElitest#antisemitism#Russian History#tsarist russia#pogrom#Communism#russia#Jewish History#Okhrana#tsar nicholas ii#Tsar Alexander III#tsar Alexander II#Pale of Settlement#Nazism#Judeo-Bolshevism#Cultural Marxism#Racism

8 notes

·

View notes

Note

Okay, I was content to just send this anonymously and leave it at that (for some reason, OP rarely answers my non-anonymous asks), but I feel I should respond here because you are being disingenuous.

I gave multiple examples of the hypothetical, and not all of them were fictional. Sam Harris is not an action movie character, neither is Dick Cheney. Torture is not something which is only discussed in action movies.

Also, OP is radically oversimplifying the issue. Torture DOES work, it's why it's so popular, including amongst certain socialist regimes (Saddsm Hussein was a type of socialist), there are only some specific scenarios where it doesn't work.

In order for torture to be ineffective, all of the following conditions have to be true:

1: you want specific, accurate information from the subject (if you want a confession, or sexual favours, or you just like hurting people, this doesn't apply).

2: you are uncertain if the subject actually knows that information (if you are torturing someone for the combination to his/her own safe, this doesn't apply).

3: you have no way to quickly verify that information in a non-costly fashion (if you want the password to a laptop and there's no maximum number of entries you can just remove another toe for every wrong answer, so this doesn't apply).

So, in most scenarios, torture works just fine. The majority of torturers don't want information, they want compliance and/or they just like torturing people. Those who DO want information can usually verify very quickly if what they are told is true or false.

"Torture doesn't work" is a moral cop out. It's an attempt to dodge the question and avoid confronting a genuine dilemma of right and wrong.

Also, don't try the ludicrous "private/personal" distinction. The human body is the most productive tool in history, it is the source of all other production, so even the (fake news baloney horsefeathers Marxist claptrap) definition based on "means of production" would not spare the human body. If Marxism had been instituted in Ancient Rome, gladiators wouldn't have been emancipated, they'd have been collectivised. Similarly to any slave society. The human body is not exempt from classification as a means of production, ergo it does not avoid socialist classification as private property, which socialists believe is no right at all.

Answer the question, OP. Torture works.

Why is it, from a socilist/communist/marxist-leninist perspective, WRONG?

As a Capitalist, as a Libertarian, as a Monarchist, I can tell you why it is wrong. I want YOUR answer.

Question: what is the communist position on torture? Since you tend to be materialists/relativists who don't believe in natural rights. What's the Marxist-Leninist response to the "ticking time bomb" scenario proposed by Sam Harris, Jack Bauer, and whatever the name of that character who Liam Neeson played in "Taken" was? You cannot appeal to absolute morality, because you don't believe in it. You cannot appeal to human rights, because that is private property, which you also don't believe in!!!

You cannot appeal to human rights, because that is private property,

376 notes

·

View notes

Quote

'Enough ink has been spilled in quarrelling over feminism ... perhaps we should say no more about it': Simone de Beauvoir, at the very beginning of The Second Sex (1949). 'The subject is irritating, especially to women.' Long before they were shouting 'Ban the Bunny' and dressing up as butchers, feminists were annoying people, not just misogynists and sexists, but the very people you'd think would like them best. It was true in suffragette days, as it was during Women's Liberation in the 1960s and 1970s, and it's very much a problem for what boosters have been calling 'the third wave' since the early 1990s. We know the angry squiggles that signify this irritation - the hairy-legged Millie Tant man-hater, Mrs Banks in the Disney Mary Poppins, a suffragette too busy to care for her children. And it's obvious how useful such stereotypes have been in neutralising the threat felt in the wider culture. But these caricatures obscure a real problem: a confusion between self and other, identity and difference, that you might charitably view as an unfortunate side-effect of being of and for and by women, all at once; or, less charitably, as narcissistic self-absorption. It's true that women, as a gender, have been systemically disadvantaged through history, but they aren't the only ones: economic exploitation is also systemic and coercive, and so is race. And feminists need to engage with all of this, with class and race, land enclosure and industrialisation, colonialism and the slave trade, if only out of solidarity with the less privileged sisters. And yet, the strange thing is how often they haven't: Elizabeth Cady Stanton opposed votes for freedmen; Betty Friedan made the epoch-defining suggestion that middle-class American women should dump the housework on 'full-time help'. There are so many examples of this sort that it would be funny if it weren't such a waste. Not that the white middle-class brigade like being on the same side as one another. There's always a tension between all of us being sisterly, all equal under the sight of the patriarchal male oppressor, and the fact that we aren't really sisters, or equal, or even friends. We despise one another for being posh and privileged, we loathe one another for being stupid oiks. We hate the tall poppies for being show-offs, we can't bear the crabs in the bucket that pinch us back. All this produces the ineffable whiff so often sensed in feminist emanations, those anxious, jargon-filled, overpolite topnotes with their undertow of envy and rancour, that perpetual sharp-elbowed jostle for the moral high ground. Looked at one way - in the manner of Joan Didion, for example, in her harsh, oddly clouded but startlingly acute essay of 1972 on the Women's Movement - the idea of feminism is obviously Marxist, being about the 'invention', as Didion put it, 'of women as a "class"', a total transformation of all relationships, led by the group most exploited by relations in their current form. So why did the libbers so seldom say so? Well, some came to the movement as Marxists, and did. Sheila Rowbotham wrote that 'the so-called women's question is a whole-people question' in Women's Liberation and the New Politics (1969); then in 1976 Barbara Ehrenreich stressed that 'there is no way to understand sexism as it acts on our lives without putting it in the historical context of capitalism.' Others shoved the categories in great handfuls through the blender: 'sex-class' must 'in a temporary dictatorship' seize 'control of reproduction' according to Shulamith Firestone in The Dialectic of Sex (1970). More prevalent, however, was what Didion called a 'studied resistance to the possibility of political ideas' - who, in any case, ever heard of a radical-feminist movement taking its understanding of historical change from a man? The entire Marxist tradition was repressed, leaving a weird sinkhole that quickly filled up with the most dreadful rubbish: wise wounds, herstory, nature goddesses, raped and defiled; sisters under the skin, flayed and joined, like the Human Centipede, in a single biomass; the fractal spread of male sexual violence, men f[***] women replicated at every level of interaction, as through a stick of rock. And so Women's Liberation started trying to build a man-free, women-only tradition of its own. Thus consciousness-raising, or what was sometimes called the 'rap group', groups of women sitting around, analysing the frustrations of their lives according to their new feminist principles, gradually systematising their discoveries. And thus that brilliant slogan, from the New York Radical Women in 1969, that the personal is political, an insight so caustic it burned through generations of mystical nonsense - a woman's place is in the home, she was obviously asking for it dressed like that. But it also corroded lots of useful boundaries and distinctions, between public life and personal burble, real questions and pop-quiz trivia, political demands and problems and individual whims. 'Psychic hardpan' was Didion's name for this. A movement that started out wanting complete transformation of all relations was floundering, up against the banality of what so many women actually seemed to want.

Jenny Turner. From “As Many Pairs of Shoes as She Likes” in the London Review of Books December 15th, 2011

NOTHING EXTREMELY RELEVANT FOR THE MODERN LEFT HERE NO NEED TO READ JUST KEEP SCROLLING :P

3 notes

·

View notes

Link

It has been 50 years since Noam Chomsky first became a major public figure in the United States, after publishing his essay “The Responsibility of Intellectuals,” which argued that American academics had failed in their core duty to responsibly inquire into truth. Over the past five decades, he has paradoxically been both one of the most well-known and influential thinkers in the world and almost completely absent from mainstream U.S. media.

Nobody has been more influential on my own intellectual development than Chomsky. But I recently realized that what I’ve learned from Chomsky’s work has had almost nothing to do with the subjects he is most known for writing about: linguistics, U.S. foreign policy, and Israel. Instead, where I feel Chomsky’s influence most strongly is in a particular kind of approach to thinking and writing about political, social, and moral questions. In other words, it’s not so much his conclusions as his method (though I also share most of his conclusions). From Chomsky’s writing and talks, I have drawn an underlying set of values and principles that I have found very useful. And I think it’s easy to miss those underlying values, because his books often either consist of technical discussions of the human language faculty or long and fact-heavy indictments of United States government policy. So I’d like to go through and explain what I’ve learned and why I think it’s important. The lessons I’ve learned from Chomsky have encouraged me to be more rational, compassionate, consistent, skeptical, and curious. Nearly everything I write is at least in part a restatement or application of something I picked up from Noam Chomsky, and it feels only fair to acknowledge the source.

1. Libertarian Socialism

In the United States, “libertarianism” is associated with the right and “socialism” with the left. The libertarians value “freedom” (or what they call freedom) while the socialists value “equality.” And many people accept this distinction as fair: After all, the right wants smaller government while the left wants a big redistributionist government. Even many leftists implicitly accept this “freedom versus equality” distinction as fair, suggesting that while freedom may be nice, fairness is more important.

Libertarian socialism, the political tradition in which Noam Chomsky operates, which is closely tied to anarchism, rejects this distinction as illusory. If the word “libertarianism” is taken to mean “a belief in freedom” and the word “socialism” is taken to mean “a belief in fairness,” then the two are not just “not opposites,” but they are necessary complements. That’s because if you have “freedom” from government intervention, but you don’t have a fair economy, your freedom becomes meaningless, because you will still be faced with a choice between working and starving. Freedom is only meaningful to the extent that it actually creates a capacity for you to act. If you’re poor, you don’t have much of an actual capacity to do much, so you’re not terribly free. Likewise, “socialism” without a conception of freedom is not actually fair and equal. Libertarian socialists have always been critical of Marxist states, because the libertarian socialist recognizes that “equality” enforced by a brutal and repressive state is not just “un-free,” but is also unequal, because there is a huge imbalance of power between the people and the state. The Soviet Union was obviously not free, but it was also not socialist, because “the people” didn’t actually control anything; the state did.

The libertarian socialist perspective is well-captured by a quote from the pioneering anarchist Mikhail Bakunin: “Liberty without socialism is privilege and injustice; socialism without liberty is slavery and brutality.” During the 1860s and ’70s, 50 years before the Soviet Union, Bakunin warned that Marxist socialism’s authoritarian currents would lead to hideous repression. In a Marxist regime, he said:

There will be a new class, a new hierarchy of real and pretended scientists and scholars, and the world will be divided into a minority ruling in the name of knowledge and an immense ignorant majority. And then, woe betide the mass of ignorant ones!… You can see quite well that behind all the democratic and socialistic phrases and promises of Marx’s program, there is to be found in his State all that constitutes the true despotic and brutal nature of all States.

This, as we know, is precisely what happened. Unfortunately, however, the bloody history of 20th century Marxism-Leninism has convinced many people that socialism itself is discredited. They miss the voices of people in the libertarian socialist tradition, like Bakunin, Peter Kropotkin, and Noam Chomsky, who have always stood for a kind of socialism that places a core value on freedom and deplores authoritarianism. It emphasizes true democracy; that is, people should get to participate in the decisions that affect their lives, whether those decisions are labeled “political” or “economic.” It detests capitalism because capitalist institutions are totalitarian (you don’t get to vote for who your boss is, and you get very little say in what your company does), but it also believes strongly in freedom of expression and civil liberties.

(Continue Reading)

#politics#the left#current affairs#noam chomsky#libertarian socialism#progressive#progressive movement

60 notes

·

View notes

Link

Last week in the prison I asked a young man why he was there.

"Just normal burglaries," he replied.

"Normal for whom?" I asked.

"You know, just normal."

He meant, I think, that burglaries were like gray skies in an English winter: unavoidable and to be expected. In an actuarial sense, he was right: Britain is now the burglary capital of the world, as almost every householder here will attest. But there was also a deeper sense to his words, for statistical normality slides rapidly in our minds into moral normality. The wives of burglars often talk to me of their husband's "work," as if breaking into other people's homes were merely a late shift in a factory. Nor is only burglary "normal" in the estimation of its perpetrators. "Just a normal assault," is another frequent answer prisoners give to my question, the little word "just" emphasizing the innocuousness of the crime.

…

As usual, one must look first to the academy when tracing the origins of a change in the Zeitgeist. What starts out as a career-promoting academic hypothesis ends up as an idea so widely accepted that it becomes not only an unchallengeable orthodoxy but a cliche even among the untutored. Academics have used two closely linked arguments to establish the statistical and moral normality of crime and the consequent illegitimacy of the criminal justice system's sanctions. First, they claim, we are all criminal anyway; and when everyone is guilty, everyone is innocent. Their second argument, Marxist in inspiration, is that the law has no moral content, being merely the expression of the power of certain interest groups—of the rich against the poor, for example, or the capitalist against the worker. Since the law is an expression of raw power, there is no essential moral distinction between criminal and non-criminal behavior. It is simply a question of whose foot the boot is on.

Criminologists are the mirror image of Hamlet, who exclaimed that if each man received his deserts, none should escape whipping. On the contrary, say the criminologists, more liberal than the prince (no doubt because of their humbler social origins): none should be punished.

…

It is impossible to state precisely when the Zeitgeist changed and the criminal became a victim in the minds of intellectuals: not only history, but also the history of an idea, is a seamless robe. Let me quote one example, though, now more than a third of a century old. In 1966 (at about the time when Norman Mailer in America, and Jean-Paul Sartre in Europe, portrayed criminals as existential heroes in revolt against a heartless, inauthentic world), the psychiatrist Karl Menninger published a book with the revealing title The Crime of Punishment. It was based upon the Isaac Ray lectures he had given three years earlier—Isaac Ray having been the first American psychiatrist who concerned himself with the problems of crime. Menninger wrote: "Crime is everybody's temptation. It is easy to look with proud disdain upon ‘those people’ who get caught—the stupid ones, the unlucky ones, the blatant ones. But who does not get nervous when a police car follows closely? We squirm over our income tax statements and make some ‘adjustments.’ We tell the customs official we have nothing to declare—well, practically nothing. Some of us who have never been convicted of crime picked up over two billion dollars' worth of merchandise last year from the stores we patronize. Over a billion dollars was embezzled by employees last year."

The moral of the story is that those who go to court and to prison are victims of chance at best and of prejudice at worst: prejudice against the lowly, the unwashed, the uneducated, the poor—those whom literary critics portentously call the Other. This is precisely what many of my patients in the prison tell me. Even when they have been caught in flagrante, loot in hand or blood on fist, they believe the police are unfairly picking on them. Such an attitude, of course, prevents them from reflecting upon their own contribution to their predicament: for chance and prejudice are not forces over which an individual has much personal control. When I ask prisoners whether they'll be coming back after their release, a few say no with an entirely credible vehemence; they are the ones who make the mental connection between their conduct and their fate. But most say they don't know, that no one can foresee the future, that it's up to the courts, that it all depends—on others, never on themselves.

…

Since then, of course, our understanding of theft and other criminal activity has grown more complex, if not necessarily more accurate or realistic. It has been the effect, and quite possibly the intention, of criminologists to shed new obscurity on the matter of crime: the opacity of their writing sometimes leads one to wonder whether they have actually ever met a criminal or a crime victim. Certainly, it is in their professional interest that the wellsprings of crime should remain an unfathomed mystery, for how else is one to convince governments that what a crime-ridden country (such as Britain) needs is further research done by ever more criminologists?

…

In the process of transmission from academy to populace, ideas may change in subtle ways. When the well-known criminologist Jock Young wrote that "the normalization of drug use is paralleled by the normalization of crime," and, because of this normalization, criminal behavior in individuals no longer required special explanation, he surely didn't mean that he wouldn't mind if his own children started to shoot up heroin or rob old ladies in the street. Nor would he be indifferent to the intrusion of burglars into his own house, ascribing it merely to the temper of the times and regarding it as a morally neutral event. But that, of course, is precisely how "just" shoplifters, "just" burglars, "just" assaulters, "just" attempted murderers, taking their cue from him and others like him, would view (or at least say they viewed) their own actions: they have simply moved with the times and therefore done no wrong. And, not surprisingly, the crimes that now attract the deprecatory qualification "just" have escalated in seriousness even in the ten years I have attended the prison as a doctor, so that I have even heard a prisoner wave away "just a poxy little murder charge." The same is true of the drugs that prisoners use: where once they replied that they smoked "just" cannabis, they now say that they take "just" crack cocaine, as if by confining themselves thus they were paragons of self-denial and self-discipline.

…

Recently, biological theories of crime have come back into fashion. Such theories go way back: nineteenth-century Italian and French criminologists and forensic psychiatrists elaborated a theory of hereditary degeneration to account for the criminal's inability to conform to the law. But until recently, biological theories of crime—usually spiced with a strong dose of bogus genetics—were the province of the illiberal right, leading directly to forced sterilization and other eugenic measures.

The latest biological theories of crime, however, stress that criminals cannot help what they do: it is all in their genes, their neurochemistry, or their temporal lobes. Such factors provide no answer to why the mere increase in recorded crime in Britain between 1990 and 1991 was greater than the total of all recorded crime in 1950 (to say nothing of the accelerating increases since 1991), but that failure does not deter researchers in the least. Scholarly books with titles such as Genetics of Criminal and Antisocial Behavior proliferate and do not evoke the outrage among intellectuals that greeted the publication of H. J. Eysenck's Crime and Personality in 1964, a book suggesting that criminality is an hereditary trait. For many years, liberals viewed Eysenck, professor of psychology at London University, as virtually a fascist for suggesting the heritability of almost every human characteristic, but they have since realized that genetic explanations of crime can just as readily be grist for their exculpatory and all-forgiving mills as they can be for the mills of conservatives.

…

The idea that prison is principally a therapeutic institution is now virtually ineradicable. The emphasis on recidivism rates as a measure of its success or failure in the press coverage of prison ("Research by criminologists shows . . . " etc.) reinforces this view, as does the theory put forward by criminologists that crime is a mental disorder. The Psychopathology of Crime by Adrian Raine of the University of Southern California claims that recidivism is a mental disorder like any other, often accompanied by cerebral dysfunction. Addicted to Crime?, a volume edited by psychologists working in one of Britain's few institutions for the criminally insane, contains the work of eight academics. The answer to the question of their title is, of course, yes; addiction being—falsely—conceived as a compulsion that it is futile to expect anyone to resist. (If there is a second edition of the book, the question mark will no doubt disappear from its title, just as it vanished from the second edition of Beatrice and Sidney Webb's book about the Soviet Union, The Soviet Union: A New Civilisation?—which included everything about Russia except the truth.)

Is it surprising that recidivist burglars and car thieves now ask for therapy for their addiction, secure in the knowledge that no such therapy can or will be forthcoming, thereby justifying the continuation of their habit? "I asked for help," they often complain to me, "but didn't get none." One young man aged 21, serving a sentence of six months (three months with time off for good behavior) for having stolen 60 cars, told me that in reality he had stolen over 500 and had made some $160,000 doing so. It is surely an unnecessary mystification to construct an elaborate neuropsychological explanation of his conduct. Burglars who tell me that they are addicted to their craft, thereby implying that the fault will be mine for not having treated them successfully if they continue to burgle after their release, always react in the same way when I ask them how many burglaries they committed for which they were not caught: with a happy but not (from the householder's point of view) an altogether reassuring smile, as if they were recalling the happiest times of their life—soon to return.

…

Since criminologists and sociologists can no longer plausibly attribute crime to raw poverty, they now look to "relative deprivation" to explain its rise in times of prosperity. In this light, they see crime as a quasi-political protest against an unjust distribution of the goods of the world. Several criminological commentators have lamented the apparently contradictory fact that it is the poor who suffer most, including loss of property, from criminals, implying that it would be more acceptable if the criminals robbed the rich. (In a radio discussion about the seasonal riots that break out in poor areas of British cities, a left-wing academic, now a cabinet minister in the present government, said that one of the tragic aspects of these riots is that they caused damage in the rioters' own neighborhood. She didn't answer my question whether she'd prefer the riots to take place in her neighborhood.)

…

Moreover, the very term "dispossessed" carries its own emotional and ideological connotations. The poor have not failed to earn, the term implies, but instead have been robbed of what is rightfully theirs. Crime is thus the expropriation of the expropriators—and so not crime at all, in the moral sense. And this is an attitude I have encountered many times among burglars and car thieves. They believe that anyone who possesses something can, ipso facto, afford to lose it, while someone who does not possess it is, ipso facto, justified in taking it. Crime is but a form of redistributive taxation from below.

Or—when committed by women—crime could be seen "as a way, perhaps of celebrating women as independent of men," to quote Elizabeth Stanko, an American feminist criminologist teaching in a British university. Here we are paddling in the murky waters of Frantz Fanon, the West Indian psychiatrist who believed that a little murder did wonders for the psyche of the downtrodden, and who achieved iconic status precisely at the time of criminology's great expansion as a university discipline.

…

No one gains kudos in the criminological fraternity by suggesting that police and punishment are necessary in a civilized society. To do so would be to appear illiberal and lacking faith in man's primordial goodness. It is much better for one's reputation, for example, to refer to the large number of American prisoners as "the American gulag," as if there were no relevant differences between the former Soviet Union and the United States.

#city journal#theodore dalrymple#blast from the past#read the whole thing#crime#law enforcement#criminology

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Clearing up Some Misconceptions

Scandinavia is not socialist. Simple. Neat. Why is this important? Well, because there is a common misconception that most countries in Scandinavia: Sweden, Norway, Denmark, etc., are indeed socialist. And why is this misconception important to address you ask? Because definitions matter.

Do you remember people calling Obama a socialist (or heck, even a Marxist by some, which is depressingly entertaining)? I mean sure, he stood behind the Affordable Care Act, minorly taxing the rich and other mildly socialistically sounding policies. But, wait a second, isn’t that Venezuelan guy Nicolás Maduro also supposed to be a socialist? And so was Bernie? Even our father Stalin, wasn’t he’s socialist??

Oh I get it. Yeah I think I get it now. It’s opposing the status quo, that’s it isn’t it? That’s what makes you a socialist? Yeah that sounds right. If you’re not with Trump you’re with the socialists.

No, nuno. That’s not right, that doesn’t sound right. Let’s take a step back here. I think it’s safe to assume there is a difference between the claim that a person is socialist and that a country or society is socialist. Surely, the former is someone that wants to create conditions present in the latter. So, by the sound of it we should start with defining what a socialism entails for a society? Yes, let’s start there.

But, quickly so I’m not taken out of context, no, I’m not implying here that Obama was nesesaarily opposing the status quo. Sure, within the American political sphere he might have seemed moderately radical, but only radical insofar as a Granny Smith is radical compared to a Gala. Apples will be apples. Also, this is not a normative piece of writing, I am simply clarifying definitions here. Sure, my own political opinions might be getting more and more clear to some readers of my blog. But this entry isn’t trying to advocate a particular ideological stance. That does not mean I am sitting on the fence though. I’m just easing you into it. Entries taking a normative stance are up next.

So, socialism, what is it? Well, it’s got to do with who controls the means of production. What are the means of production? In a nutshell, they are: the means that are employed to produce things (both things essential to our survival and things not). Examples include: factories, businesses, resources used, technologies, the list goes on. In capitalist societies, the means of production are privately owned, that is by private individuals who own factories, businesses, etc. They are referred to as capitalists. They employ people who do not own the means of production, who can only sell their own labour power. They are referred to as the proletariat. In contrast, in socialist societies the means of production are owned collectively. That is to say by the people. Put into practice, this can include worker cooperatives, state industry and public ownership. It does not necessarily consider the all-powerful state as a bad thing (except by anarchists or anarcho-communists who believe the state actually upholds capitalist society by existing alongside it and enforcing a class structure). This is because, necessarily under this system, governments are run by the people and therefore all state assets are public assets.

In essence, socialism means abolishing private property. ‘Oh no!’ You might be saying. ‘I don’t want to share my house with strangers. I don’t want the state to take all my stuff and control my life! You remember what happened in Doctor Zhivago, don’t you?? Don’t you??’... Fret not. This is years of Cold War propaganda talking. Something I see over and over again is this mis-definition of private property. Private property does not mean your fancy clothes, your TV, your knick-knacks, your house or your car. These are personal property. Private property refers specifically to privately owned means of production. See the misunderstanding? It’s not really that surprising that this is confusing, as in our capitalist society this distinction is necessarily nonexistent. So, in other words, in a socialist society you’re still free to keep all your nice things, you just can’t use these things to employ others to create more things. Why can’t you do this? Because private ownership of the means of production is seen as oppressive (the reasons for this will be discussed further, in a future post).

Now, I should say, it would be naïve to suggest that no one would have to give up some of their stuff/personal property. But unlike your average right wing libertarian would argue, socialism doesn’t mean that it is the average person (99.9999999% of the people reading this article) who would be giving up their stuff. Instead it is the people who we already know have waaaay to much. Yes, you know, those guys with super yachts (and yes I am generalising here). Basically those who we already know have faaar too much stuff to be able to be consumed by a single individual. Also, even if someone who has 15 houses, 10 cars and five yachts says this property is merely recreational, i.e. used only as though it were personal property. Well, then I implore you to ask them how they made the all the money that allowed them to buy all said personal property. You guessed it: private property. In other words, they will own a factory and/or business that allowed them to create the excessive wealth needed, through worker exploitation, to buy all their stuff. Anyway, who’s saying it might not be kinda good to foster a slightly less materialistic mentality?

So, under this definition, is Scandinavia socialist? NO! Heck no. In Scandinavia, the means of production are privately owned. Case closed. Sure, they might have a social democracy, but this is different. This just advocates some state invervention in order to help in questions of social justice and the like, but it still presupposes the capitalist mode of production (i.e. privately owned means of production). Also, some industry might be state owned, but the mere existence of private property is incompatible with a socialist definition of these countries. And yes, this also means that Obama is not a socialist, and (this gets to me a little) that Venezuela is not a socialist country, regardless of the rubbish our media is trying to shove down our throats.

Some other points: socialism is not the same as communism and social democracy is not the same as democratic socialism. And these are also different from Marxism and anarchism. Some overlap, some do not. If you’re more interested in the distinctions between these, watch this video.

Also, a final small point. I did joke (sarcastically) earlier that socialism was defined as opposing the status quo. Whilst this is not true, it’s important to point out that, ironically, if you are indeed a socialist, you will most likely be opposing the current status quo. And if you don’t, then you’re probably not a socialist.

Anyway, I hope this helped clarify things. Now, don’t go accusing people of being socialists without good reason. And if you do call someone a socialist who actually is a socialist, they’ll probably appreciate you took the time to understand what this claim in fact entails.

#socialism#communism#capitalism#marxism#means of production#private property#personal property#left wing#politics

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

You Can’t Change the Mind of Steven Crowder, and It’s Not Worth Trying

by Brice Ezell

If you know Steven Crowder, it’s likely for the meme seen above, derived from his “Change My Mind” series on his YouTube channel and CRTV show, Louder with Crowder. In this series, Crowder places himself in various locales — typically university campuses, though he also took the streets of my own Austin, TX for one installment — and invites people to challenge him on his deeply held views, which thus far have included, to name a few: “There are Only Two Genders,” “Hate Speech Doesn’t Exist,” “I’m Pro-Life,” and “Trump is Not a Fascist.” Each one of these “Change My Minds” is equal part provocation and, ostensibly, invitation to debate: rather than sit in his CRTV studio 24/7, addressing a paying audience who largely shares his views, Crowder does attempt to get his viewpoints out into the public, subject the scrutiny of any passersby.

Yet it’s not long into any one of these “Change My Mind” segments — to say nothing of his other YouTube videos — that the veneer of respectable debate, well, starts looking a lot less respectable. Like Nathan J. Robinson, I hold the view that debates between the political left and right, when done well, are important and can advance civil discourse in helpful ways. So when I first heard about Crowder and saw that, unlike a cheap shock jock, he actually invited anyone to debate him, I thought for a (fleeting) moment that he might be someone invested in actually facilitating substantive debate on the important issues of our divisive political times.