#alexander trocchi

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Photo

Frances Lengel (aka Alexander Trocchi) - Desire and Helen - publisher uncertain - circa 1967

#witches#aussies#occult#vintage#desire and helen#frances lengel#alexander trocchi#circa 1967#complete & unexpurgated#first american printing

125 notes

·

View notes

Text

various artists, semina two, 1957

#wallace berman#charles brittin#hermann hesse#paul eluard#cameron#jack anderson#jean cocteau#zack walsh#eric cashen#lynn trocchi#aya tarlow#james boyer may#charles baudelaire#charles bukowski]#peder carr#judson crews#john reed#lewis carroll#david meltzer#marion grogan#paul valery#walter hopps#alexander trocchi#john altoon#michael mcclure#rabindranath tagore#art#writings#1950s#50s

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

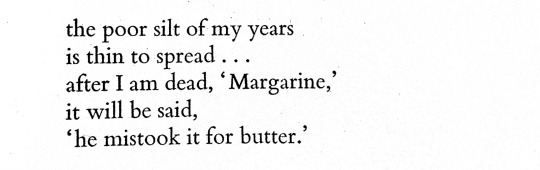

from £ S D (love, sex death pounds, shillings, pence lysergic acid) by Alexander Trocchi

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bentz van den Berg portretteert The Outsiders

De legendarische beatband The Outsiders met Wally Tax (midden); bron beeld: blogspot.com Een beatbandje uit Amsterdam-Oost. Ik heb het over The Outsiders, de band van zanger Wally Tax, die de band begon toen hij 12 jaar oud was, en gitarist Ronnie Splinter. Een band die furore maakte in Amsterdam en daarna de rest van het land ten tijde van Beatles en Stones. Lang haar en attitude: vuig, vilein,…

View On WordPress

#Alexander Trocchi#Amsterdam#Amsterdamse Lente#bas#beatband#Beatles#Bentz van den Berg#bleek#classics#drumroffels#geluid#gitaren#honger#Jagger & Richards#jaren 60#kouwelijk#Las Vegas#Lennon & Mc Cartney#mondharmonica#onverschilligheid#pruimtabak#Ray Davis#rock &039;n roll#Ronnie Splinter#Schots#schrijver#Sheharazade#songs#Stones#The Outsiders

0 notes

Note

Advice/hard truths for writers?

The best piece of practical advice I know is a classic from Hemingway (qtd. here):

The most important thing I’ve learned about writing is never write too much at a time… Never pump yourself dry. Leave a little for the next day. The main thing is to know when to stop. Don’t wait till you’ve written yourself out. When you’re still going good and you come to an interesting place and you know what’s going to happen next, that’s the time to stop. Then leave it alone and don’t think about it; let your subconscious mind do the work.

Also, especially if you're young, you should read more than you write. If you're serious about writing, you'll want to write more than you read when you get old; you need, then, to lay the important books as your foundation early. I like this passage from Samuel R. Delany's "Some Advice for the Intermediate and Advanced Creative Writing Student" (collected in both Shorter Views and About Writing):

You need to read Balzac, Stendhal, Flaubert, and Zola; you need to read Austen, Thackeray, the Brontes, Dickens, George Eliot, and Hardy; you need to read Hawthorne, Melville, James, Woolf, Joyce, and Faulkner; you need to read Tolstoy, Dostoyevsky, Turgenev, Goncherov, Gogol, Bely, Khlebnikov, and Flaubert; you need to read Stephen Crane, Mark Twain, Edward Dahlberg, John Steinbeck, Jean Rhys, Glenway Wescott, John O'Hara, James Gould Cozzens, Angus Wilson, Patrick White, Alexander Trocchi, Iris Murdoch, Graham Greene, Evelyn Waugh, Anthony Powell, Vladimir Nabokov; you need to read Nella Larsen, Knut Hamsun, Edwin Demby, Saul Bellow, Lawrence Durrell, John Updike, John Barth, Philip Roth, Coleman Dowell, William Gaddis, William Gass, Marguerite Young, Thomas Pynchon, Paul West, Bertha Harris, Melvin Dixon, Daryll Pinckney, Darryl Ponicsan, and John Keene, Jr.; you need to read Thomas M. Disch, Joanna Russ, Richard Powers, Carroll Maso, Edmund White, Jayne Ann Phillips, Robert Gluck, and Julian Barnes—you need to read them and a whole lot more; you need to read them not so that you will know what they have written about, but so that you can begin to absorb some of the more ambitious models for what the novel can be.

Note: I haven't read every single writer on that list; there are even three I've literally never heard of; I can think of others I'd recommend in place of some he's cited; but still, his general point—that you need to read the major and minor classics—is correct.

The best piece of general advice I know, and not only about writing, comes from Dr. Johnson, The Rambler #63:

The traveller that resolutely follows a rough and winding path, will sooner reach the end of his journey, than he that is always changing his direction, and wastes the hours of day-light in looking for smoother ground and shorter passages.

I've known too many young writers over the years who sabotaged themselves by overthinking and therefore never finishing or sharing their projects; this stems, I assume, from a lack of self-trust or, more grandly, trust in the universe (the Muses, God, etc.). But what professors always tell Ph.D. students about dissertations is also true of novels, stories, poems, plays, comic books, screenplays, etc: There are only two kinds of dissertations��finished and unfinished. Relatedly, this is the age of online—an age when 20th-century institutions are collapsing, and 21st-century ones have not yet been invented. Unless you have serious connections in New York or Iowa, publish your work yourself and don't bother with the gatekeepers.

Other than the above, I find most writing advice useless because over-generalized or else stemming from arbitrary culture-specific or field-specific biases, e.g., Orwell's extremely English and extremely journalistic strictures, not necessarily germane to the non-English or non-journalistic writer. "Don't use adverbs," they always say. Why the hell shouldn't I? It's absurd. "Show, don't tell," they insist. Fine for the aforementioned Orwell and Hemingway, but irrelevant to Edith Wharton and Thomas Mann. Freytag's Pyramid? Spare me. Every new book is a leap in the dark. Your project may be singular; you may need to make your own map as your traverse the unexplored territory.

Hard truths? There's one. I know it's a hard truth because I hesitate even to type it. It will insult our faith in egalitarianism and the rewards of earnest labor. And yet, I suspect the hard truth is this: ineffables like inspiration and genius count for a lot. If they didn't, if application were all it took, then everybody would write works of genius all day long. But even the greatest geniuses usually only got the gift of one or two all-time great work. This doesn't have to be a counsel of despair, though: you can always try to place yourself wherever you think lightning is likeliest to strike. That's what I do, anyway. Good luck!

781 notes

·

View notes

Text

Birthdays 7.30

Beer Birthdays

Hamar Alfred Bass (1842)

Leopold Nathan (1864)

Tom Peters (1953)

Peter Cogan (1962)

Dr. Bill Sysak (1962)

Dean Biersch

Jim Jacobs (1963)

Five Favorite Birthdays

Kate Bush; English pop singer (1958)

Buddy Guy; blues guitarist, singer (1936)

Richard Linklater; film director (1960)

Jean Reno; Moroccan-French actor (1948)

Thorstein Veblen; economist (1857)

Famous Birthdays

Paul Anka; pop singer, songwriter (1941)

Duck Baker; guitarist (1949)

Simon Baker; Australian actor, director (1969)

Henry W. Bloch; H&R Block founder (1922)

Ron Block; singer-songwriter and banjo player (1964)

Peter Bogdanovich; film director (1939)

Marc Bolan; rock singer (1947)

Emily Bronte: English writer (1818)

Alton Brown; chef, television host (1962)

Delta Burke; actor (1956)

Smedley Butler; U.S. Marines major general (1881)

Princess Clémentine of Belgium (1872)

Frances de la Tour; English actress (1944)

Dean Edwards; comedian (1970)

Laurence Fishburne; actor (1961)

Henry Ford; car manufacturer (1863)

Kerry Fox; New Zealand actress (1966)

Vivica A. Fox; actor (1964)

Craig Gannon; English guitarist and songwriter (1966)

Tom Green; Canadian comedian and actor (1971)

Jeffrey Hammond; English bass player (1946)

Anita Hill; law professor, victim (1956)

Sid Krofft; Canadian-American puppeteer (1929)

Lisa Kudrow; actor (1963)

Soraida Martinez; painter (1956)

Christine McGuire; pop singer (1929)

Patrick Modiano; French novelist (1945)

Henry Moore; artist, sculptor (1898)

Sean Moore; Welsh drummer and songwriter (1968)

Chris Mullin; basketball player (1963)

Christopher Nolan; English-American film director (1970)

Salvador Novo; Mexican poet and playwright (1904)

Ken Olin; actor (1954)

Pollyanna Pickering; English environmentalist and painter (1942)

Jaime Pressly; actor (1977)

Samuel Rogers; English writer (1763)

David Sanborn; saxophonist (1945)

Rat Scabies, English drummer (1955)

Arnold Schwarzenegger; Austrian-born body builder, actor (1947)

Hope Solo; soccer player (1981)

Frank Stallone; singer-songwriter and actor 91950)

Stan Stennett; Welsh actor and trumpet player (1925)

Casey Stengel; baseball manager (1891)

Hilary Swank; actor (1974)

Otis Taylor; singer-songwriter and guitarist (1948)

Alexander Trocchi; Scottish author and poet (1925)

Giorgio Vasari; Italian painter (1511)

Dick "Mr. Whipple" Wilson; actor (1916)

Victor Wong; actor (1927)

1 note

·

View note

Text

0 notes

Quote

And I was lying alone, and everything, even the emptiness of the night had receded into the familiar sound of my own breathing. I was left only with my awareness of it. And the gradually I came into another world, a close and confederate consciousness of my own softness and the sound of my breathing and nothing more and there was nothing to which I was related. And now I came to know that it was my body which was soft, the thighs, my little belly, set and smooth as a watchglass on a fine watch, and it was I and not my body which was aware. And now I was conscious of existing and being alone and I couldn’t be conscious of myself as existing without at the same time being conscious of myself as existing alone and in relation to instants in time and points in space which held themselves off from me and escaped me, for I hadn’t the power to draw them back to myself out of my memory.

I, Sappho of Lesbos: The Autobiography of a Strange Woman, “edited” by Michel Darius (Alexander Trocchi)

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Alexander Trocchi | A Revolutionary Proposal: Invisible Insurrection of a Million Minds

➔PDF

28 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Cain's Book by Alexander Trocchi.

40 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Political revolt is and must be ineffectual precisely because it must come to grips at the prevailing level of political process. Beyond the backwaters of civilization it is an anarchronism. Meanwhile, with the world at the edge of extinction, we cannot afford to wait for the mass. Nor to brawl with it. The coup du monde must be in the broad sense cultural. With his thousand technicians, Trotsky seized the viaducts and the bridges and the telephone exchanges and the power stations. The police, victims of convention, contributed to his brilliant enterprise by guarding the old men in the Kremlin. The latter hadn’t the elasticity of mind to grasp that their own presence there at the traditional seat of government was irrelevant. History outflanked them. Trotsky had the railway stations and the powerhouses, and the “government” was effectively locked out of history by its own guards. So the cultural revolt must seize the grids of expression and the powerhouses of the mind. Intelligence must become self-conscious, realise its own power, and, on a global scale, transcending functions that are no longer appropriate, dare to exercise it. History will not overthrow national governments; it will outflank them. The cultural revolt is the necessary underpinning, the passionate substructure of a new order of things.

A Revolutionary Proposal: Invisible Insurrection of a Million Minds: Alexander Trocchi

1 note

·

View note

Text

Alexander Trocchi - Helen & Desire - Brandon House - 1967

#witches#desirous#occul#vintage#helen & desire#brandon house#alexander trocchi#jack hirschman#ph.d.#1967

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kicking Against the Pricks: An Interview with Chris Kelso

Kicking Against the Pricks: An Interview with Chris Kelso

Chris Kelso is an award-winning writer, the author of nine novels, three short story collections and editor of five anthologies. His writing, celebrated for its transgressive style and dysfunctional subject matter, has appeared in Evergreen Review, Sensitive Skin and 3AM Magazine. The British Fantasy Society described The Dregs Trilogy – a degenerate platter of snuff movies, psycho killers and…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Audio

THIS IS MY SONG FOR EUROPE. Cassette copies of new Mines going fast so head to thelokilabel.storenvy.com if you want to get one in North America, and to our bandcamp if you want one elsewhere. Next up: 45rpm 7″ single, mangled dub mixtape, third part of the rocknroll trilogy on blackest ever wax.

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Young Adam, 2003, David Mackenzie

based on Alexander Trocchi’s novel

4 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Hatırlayabildiğim kadarıyla ben hep böyleydim. Köksüz denen türdeki adamlardan. Sıklıkla başka insanlarla ilişkiye girme hevesine kapılır ama çabucak daralıp tekrar özgürlüğüme kavuşmak için yanıp tutuşurdum. On yıl önce bir bahar sabahı ıvır zıvırımı küçük bir çantaya doldurup üniversiteden ayrılmıştım. Asla geri dönmedim. O zamandan beri, paraya gerek duyunca çalıştım; çünkü çekip gitme ihtiyacı duydum; çünkü bana sunulan hayatın gerekliliklerine karşı daima içinde bulunduğum durumlarda ezildiğim, sıkıştığım hissine kapıldım.

Alexander Trocchi, Genç Adem, Versus, İstanbul, 2007, s. 81.

2 notes

·

View notes