#complete & unexpurgated

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

a complete hunger for you, a devouring hunger.

Henry Miller - letter to Anaïs Nin, ‘Henry and June,’ "A Journal of Love," The Unexpurgated Diary (1931-1932) of Anais Nin

457 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Diary of Vaslav Nijinsky (Unexpurgated)

Vaslav Nijinsky (Author) Joan Acocella (Editor)

A uniquely personal record of a great artist's experience of mental illness

In his prime, Vaslav Nijinsky (1889-1950) was the most celebrated man in Western ballet--a virtuoso and a dramatic dancer such as European and American audiences had never seen before. After his triumphs in such works as The Specter of the Rose and Petrouchka, he set out to make ballets of his own, and with his Afternoon of a Faun and The Rite of Spring, created within a year of each other, he became ballet's first modernist choreographer.

For six weeks in early 1919, as his tie to reality was giving way, Nijinsky kept a diary--the only sustained daily record we have, by a major artist, of the experience of entering psychosis. In some entries he is filled with hope. He is God; he will save the world. In other entries, he falls into a black despair. He is dogged by sexual obsessions and grief over World War I. Furthermore, he is afraid that he is going insane.

The diary was first published in 1936, in a version heavily bowdlerized by Nijinsky's wife. The new edition, translated by Kyril FitzLyon, is the first complete and accurate English rendering of this searing document. In her introduction, noted dance critic Joan Acocella tells Nijinsky's story and places it in the context of early European modernism.

(Affiliate link above)

341 notes

·

View notes

Text

The serenity of knowing what is supremely and divinely right. The world is at last focused. This is the center. And strange—the center can only be a fulfilled circle, of course, which I never knew before because I was only a crescent moon, a curved half circle, curved in gaping, dolorous craving, bowed around emptiness, arms surrounding to meet nothing, a line unfinished, a life unrounded, a curve unfilled, suspended over the world, pale with unfullness, and now shining round, rounded, complete in geometric splendor, in totality, in full magnificence.

Anaïs Nin, Incest: From a Journal of Love: The Unexpurgated Diary of Anaïs Nin 1932-1934

70 notes

·

View notes

Text

I want a complete and equal love.

Anaïs Nin, from The Unexpurgated Diary of Anaïs Nin, 1931-1932

#quotes#poetry#literature#poetry by women#anaïs nin#The Unexpurgated Diary of Anaïs Nin: 1931-1932#themes: untagged

99 notes

·

View notes

Text

Broadcast — Spell Blanket: Collected Demos 2006 - 2009 (Warp)

The 16-year career of Broadcast elicits not just nostalgia for psychedelia, but for the bygone, awestruck moment when new studio recording technology made it possible to build entire worlds in sound, and in some sense to live in those worlds. Until lead singer Trish Keenan’s untimely death in 2011 at age 42 Broadcast dwelled in sound.

Broadcast was influenced to an outsized degree by one obscure album, the self-titled and only release from the United States of America in 1968. That album brims with the exuberance of some young, newly minted electronic music obsessives, several of whom later made careers as academic composers, avant-garde musicians, or sound artists working in media. That early album is marked by both beauty and no small share of clowning — electronics could be sonically eerie, but they could just as easily generate mechanistic slide whistles or burps.

Broadcast retained the United States of America’s sense of awe and play with sound, though they streamlined this approach through disciplined musicianship as well as a number of stylish signatures, including Keenan’s finely threaded vocals, James Cargill’s forceful drumming, a tendency to write in waltz time (it works) and sometimes an overdriven organ. In place of silliness, Broadcast often inserted something more aloof, but there is not a song in their catalog where they aren’t clearly reveling in sonic atmospheres, just as the United States of America had done. Broadcast’s shows were deeply immersive experiences, as complete and convincing a gesamntkunstwerk as I’ve ever seen from a rock band.

In the years before she died, Keenan kept a kind of sonic diary via MiniDisc, a format which in the 2000s enjoyed a brief moment as a medium of choice for sharing larger files. The entries she made ranged from grainy snippets of vocal melodies to relatively polished song demos recorded with Cargill and others, advanced drafts that might have become songs on a subsequent Broadcast album. As Spell Blanket contains 36 tracks, it is difficult to know which of these sketches were bound for release and which were only fleeting ideas. (Cargill must have endured an emotionally enormous task in curating this material). But a track like “Follow the Light” suggests what might have been. On that recording, Keenan sings a haunting, minor-key melody in gorgeous counterpoint to two organ lines, one high and one low, both swimming in reverb in a way that exemplifies the group’s métier of crafting sonic worlds. “The Games You Play,” with its motorik drums and clouds of recorder grot pitted against the vocals, likewise sounds almost finished. On the other hand, “The Song Before the Song Comes Out” seems to be Keenan sketching a possibility with her voice and whatever device she had at hand. This kind of intimacy is evident on a number of the collection’s tracks.

There will be a final Broadcast album later this year, a recreation by Cargill using the fragments Keenan left behind. In the meantime, we have Spell Blanket, a mostly unexpurgated view inside the process of building worlds in sound, at the sort of unfinished stage that the band’s albums ardently never revealed when they were together.

Benjamin Tausig

#broadcast#spell blanket#collected demos#2006-2009#warp#ben tausig#albumreview#dusted magazine#psychedelia#electronic music

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

I am lying on a hammock, on the terrace of my room at the Hotel Mirador, the diary open on my knees, the sun shining on the diary, and I have no desire to write. The sun, the leaves, the shade, the warmth, are so alive that they lull the senses, calm the imagination. This is perfection. There is no need to portray, to preserve. It is eternal, it overwhelms you, it is complete.

— Anais Nin, from her diary dated January 1936. "Incest: From a Journal of Love: The Unexpurgated Diary of Anaïs Nin, 1932-1934". (Mariner Books; September 16, 1993) (via Make Believe Boutique)

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

tagged by @elfgarlic to answer these silly questions :) thanks for thinking of me!! 🪻

favourite colour(s): moth dust pink, sage green, or wisteria

last song played: 'pagan poetry' - bjork

currently reading: Omg... a dusty old 1964 print of 'complete and unexpurgated kama sutra of vatsyanana: the long-suppressed oriental manual on the art and techniques of love' by franklin s. klaf, m.d. It's extremely dated and sexist & a fascinating read . I love finding old books on spirituality or psychosexuality and getting 500kW to the system in culture shock . Oh how much we've evolved....

currently craving: an amaretto sour with a benson & hedges

coffee or tea: green tea in the morning and jasmine milk tea throughout the day

tagging: @plasticine-deer @yveltal @lostcryptids @psychicpervert @8hlune @youreaclownnow @mortimer @vampfucker666 @virtua if you guys wanna! ^_^

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Speech of Comrade Jiangqing on the Culture and Arts (c1970s)

“Jiang’s philosophy of heroism seems unusual for the wife of China’s most famous communist. Marxist analysis doesn’t obviously lend itself to individual valorization. But Marx was not Madame Mao’s teacher in these matters. That role fell to Friedrich Nietzsche.

Jiang was hardly the only Nietzschean in the red camp. Mao Zedong himself had been exposed to Nietzsche before Marx. Late Qing reformers had picked up Nietzsche’s ideas as they visited Japan and Germany; the young Mao devoured their work. The archives preserve Mao’s first writing on Nietzsche, scribbled in the margins of Cai Yuanpei’s translation of Friedrich Paulsen’s A System of Ethics. Mao admired the neo-Kantian Paulsen but had an instinctual sympathy with Nietzsche’s view that traditional morality needed to be upended. Only by harnessing powerful, buried forces did Mao see a path toward a new world.

The artists and thinkers of the early Republican period were likewise enthralled by Nietzsche, the rebel philosopher who believed in the power of culture. For those focused on sweeping away the dust of feudal China, his nihilistic attack on tradition and call to overcome slave morality translated well into the post-imperial context. It is no wonder that Nietzsche was idolized by Chen Duxiu and Li Dazhao, who would go on to found the Communist Party.

Even once figures like Chen, Li, and Mao turned left, they continued to absorb Nietzschean ideas. His thinking permeated many of the Bolsheviks, as well as radical Russian intellectuals and artists. Vladimir Lenin, Leon Trotsky, Aleksandr Bogdanov, and Nikolai Bukharin all refer to Nietzsche explicitly or implicitly. Bukharin and Bogdanov, in particular, drew on him enough to be dubbed “Nietzschean Marxists” by scholars. In the words of historian Bernice Glatzer Rosenthal, Nietzsche was “a vital element of Bolshevism,” animating an “activist, heroic, voluntaristic, mercilessly cruel, and future-oriented interpretation of Marxism.” This line of Soviet cultural revolution intensified under the leadership of Stalin in the 1920s and 1930s: monumental art glorified the proletarian hero. There was even room for the Dionysian excess of the Russian avant-garde, though Stalin eventually turned against it.

Jiang, moving in radical circles in the 1930s, absorbed these ideas. Her study of Nietzsche came through the scholar Lu Xun. Before becoming the patron saint of socialist literature in the People’s Republic of China, Lu was its foremost interpreter, translator, and popularizer of Nietzsche. Jiang idolized him, later declaring that while Mao was her political north star, Lu Xun provided her cultural guidance. While his books had been bowdlerized to remove more provocative texts, Jiang kept an unexpurgated 1938 edition of his collected work on her bookshelf deep into the Cultural Revolution, handbound in twenty volumes.

Lu Xun was a Nietzschean through and through. His reading of Thus Spake Zarathustra in Japan in 1902 changed his worldview completely. In “On Cultural Extremism,” an essay published in 1908, he pointed to the ideals of Nietzsche as the solution to China’s ills—only the will to power of supreme individuals was capable of leading the benighted masses. Jiang would certainly have read “On Satanic Poetry,” which Lu wrote under the stated influences of Nietzsche and Lord Byron. In it, he called for spiritual fighters and savage rebels to destroy the ultrastable system of Chinese ethics. Like Maxim Gorky in Russia, Lu’s political allies downplayed his Nietzschean sympathies after he moved to the left, but they continued to energize his writing, theory, and criticism until his death in 1936.

When the communists took control of China in 1949, Nietzsche was in the bloodstream of the party. His thinking would inform the psychopolitical project of creating the New Socialist Man in the ashes of the old society. When Jiang led her Dionysian artistic assault on the Apollonian state, Nietzsche was with her.

Later, when Jiang sat in Qincheng Prison, her enemies used this lineage against her. In 1977, Cao Boyan and Ji Weilong sought to protect the party’s ideological continuity by condemning the Gang of Four as Nietzscheans who contradicted Maoism. Through 1978 and 1979, articles like Zhang Wen’s “The New Disciples of Nietzschean Philosophy” and Zhang Zhuomin’s “The Will to Power and Social Fascism” attacked the Cultural Revolution as an expression of the will to power. An essay by Dai Wenlin charged Jiang with trying to create a new social fascist model of the Übermensch.

The commentary against Jiang revealed for a moment what most historiography of socialist China has worked to conceal: Nietzsche haunts all of the revolutions that China experienced in the twentieth century.

Jiang’s entry into the practice of cultural struggle began in the early 1960s when Mao found himself sidelined by his own party. Liu Shaoqi and Deng Xiaoping were rising in the aftermath of the Great Leap Forward and the Seven Thousand Cadres Conference, with pragmatic policies that Jiang saw as unacceptably revisionist. She turned to culture to defend the cause. This was not merely a means to propagate political messages or attack enemies; following Nietzsche, Jiang believed that the world’s existence was justified only as an aesthetic phenomenon. Following Lu Xun, she also believed that culture could overcome the hegemony of conventional ethics.

(…)

This focus on heroic cadres laboring in the provinces was politically useful, since highlighting prominent leaders could backfire in the event of a later purge. But it was also part of the Maoist endeavor to create a new revolutionary culture among Chinese peasants and workers. In his “Talks at the Yan’an Forum on Literature and Art,” Mao had previously promoted the use of folk forms and the magnification of heroic traits. Jiang’s application went even further and demanded their complete transformation:

Out of the worker, peasant, and soldier, we must enthusiastically and by any means create heroic images. As Chairman Mao told us, the world represented in art can and should surpass reality. It should be stronger, purer, more perfect, and more idealized. Don’t be limited by real people and events. Stop writing about dead heroes when we are surrounded by living heroes.

Echoing Nietzsche’s division of art from truth, Jiang called for a break from the rules of realism, revolutionary or otherwise. Other Chinese thinkers had critiqued realist ideas with the concept of revolutionary romanticism as the Sino-Soviet split took effect. Jiang outstripped them, calling for heroes that defied reality itself.

(…)

While Jiang personally directed the productions created in this process of aesthetic reorganization, her fellow Gang of Four member Yao Wenyuan later systematized these ideas. He outlined the “Three Prominences” which Jiang and Yao believed all cultural productions should highlight: the prominence of positive characters in a work, the prominence of heroes among the positive characters, and the prominence of the major heroic protagonist among the supporting heroes. Nothing was left to interpretive chance: the protagonist would always be “Red, Bright, and Clear”—accompanied by a literal red glow, projecting an aura of willful positivity, and with an unobscured role and set of virtues. A third principle, “Tall, Mighty, Complete,” set forth that the main hero must physically dominate and appear to tower over surrounding characters with an overpowering presence, free of negative characteristics.

Anti-heroes and navel-gazing introspection about the cause had no place in the revolutionary operas. While these tropes later gained popularity in China and had already become more prominent in Western literature, the apparent “moral complexity” they allowed for only served to diminish the heroic consciousness. They cultivated a suspicion toward the heroic impulse, which became seen as a mask for morally compromised souls as lowly and unworthy as everyone else.

By contrast, Jiang’s insistence on the aesthetic and physical valorization of the hero made them more real than the world they struggled against. They did not fall into the trap of slave morality by letting their enemies define them. Vividly more worthy than those they fought against, they overcame them by sheer force of will. Their noble character also served to accuse those supposed allies with compromised commitments—they were without excuse for failing to live up to the heroic ideal. Again and again in the revolutionary operas, those who join the hero’s battle end up reflecting their beauty and vitality.

(…)

Jiang did not lack collaborators. The left-wing artists that had driven Chinese culture in the 1930s were given a long leash by a party leadership made up mostly of urban intellectuals. Dance, in particular, had become a refuge for artists and composers. Jiang was uninterested in the numerous modern dance dramas, which included topical productions about the Vietnam War and Patrice Lumumba, and in experiments in adapting folk dance. It was the revolutionary modern ballets that held the most appeal for Jiang. They exemplified high-art elitism. She loved her hardened, beautiful ballerinas and the heroic themes present in ballets like Red Detachment of Women and The White-Haired Girl.

As the Cultural Revolution progressed, her guidance saw revolutionary ballets become extensively modified. New pieces were composed or sections removed to push them toward pure heroism and compliance with the “Three Prominences,” “Red, Bright, Clear,” and “Tall, Mighty, Complete.” In her selection of artistic forms, Jiang maintained the standard that what was beautiful should not be debased at the hands of popular instincts. The ballet, opera, and cinema that defined the Cultural Revolution were not vulgar kitsch, unlike much of the literature of the time. Jiang was interested in high art and her speeches and writing gave no consideration as to whether or not these forms would be appropriate for the masses. Yet, they proved popular enough that they are still performed today.

The filmed version of Ode to Yimeng, released in 1975, is the pinnacle of Jiang’s vision for ballet. While it retains a scene from older renditions of the protagonist feeding a wounded partisan from her breast, in the hands of Jiang it is less a fable of feminine sacrifice than of individual ungendered heroism. With Cheng Bojia dancing as the lead, the tall, powerful beauty seems just as prepared to toss the wounded soldier over her shoulder as she is to suckle him. Her knife fight against local goons, charged in earlier versions with fear of the woman being overpowered, becomes slightly surreal as she seems to tower over her opponents while cast in a red glow and moving effortlessly en pointe. The reels were quickly transported around the country. Urban audiences sat in theaters and villagers gathered around projectors under the stars to watch Cheng Bojia as the national embodiment of Jiang’s Nietzschean heroine.

Meeting the technical, artistic, and ideological perfection that Jiang demanded was no easy task. The heroic art Jiang envisioned required her to mobilize the best and brightest. Yu Huiyong, a composer and theorist, became Jiang’s constant companion as she oversaw this program of cultural engineering. He had originally won the right to work on revolutionary opera in a contest held by Jiang in Shanghai in 1965. The contest reflected Jiang’s demand for raw aesthetic ability: twenty composers were charged with creating an original aria inspired by a lyric from Taking Tiger Mountain by Strategy.

After Yu fell afoul of Jiang’s own atmosphere of persecution—he was attacked both for slavish devotion to Western forms and for failing to support Jiang’s call to add Western instruments to Chinese orchestras—she rehabilitated him. Jiang wasn’t going to be politically pedantic. Working with the right kind of visionaries came first. Those with ability could be forgiven for political transgressions that condemned the less-than-worthy. Drafted into service alongside many of the best artists and musicians, he worked with Jiang to fine-tune her favorite works in a production process similar to the Hollywood studio system.

The revolutionary opera On the Docks became a shared masterpiece between Yu and Jiang. Yu had worked earlier on experiments in combining Chinese and Western instruments and tuning, as in the incorporation of “The Internationale” as a leitmotif in The Red Lantern, and On the Docks would be the perfection of these attempts. This arrangement of Chinese and Western orchestras would eventually become common, but Yu was the first to pull it off. Yu’s compositions, like the choreography for the revolutionary modern ballet, forged something new from the deconstruction of indigenous folk forms and Western high art. The result is considered a triumph of Cultural Revolution art.

Perfection was the rule. When a film version of On the Docks was shot in 1972, it only circulated for a brief time before Jiang’s careful review found deficiencies: the color grading was too pale, robbing her heroes of their red glow, and the cinematography failed to live up to the demands of “Red, Bright, Clear.” A reshoot appeared the following year, using the same performers and crew.

(…)

When her political luck ran out, she refused submission. As one biographer wrote: “She held fast to her moral sovereignty as an individual.” Charged under Article 103 of the Chinese criminal code for committing counter-revolutionary acts that caused grave harm to the state and the people, death was a likely outcome. On the stand, she gave her final performance as the hero in chains, persecuted by the rabble. “I fear nobody,” she thundered. “I am above the law of men and of Heaven!”

In the end, Jiang lived long enough to see what Deng Xiaoping’s cultural bureaucracy did to the program she had created. Reform and Opening Up became an age of individualist ressentiment, rather than cultural affirmation. Envy, persecution, and petty hatreds became the obsessions of new waves of art and film. Writers turned to “scar literature,” detailing their suffering under the Cultural Revolution.

Popular films showed the persecution of intellectuals by the Gang of Four. The victims, unlike the peasant girl in Red Detachment of Women, did not rescue themselves. Instead, they were made pure by their suffering. Artists were encouraged to turn inwards, to find their deepest pain. In Nietzschean terms, it was a full re-embrace of the slave morality that finds moral worth in the negation of health, power, and vitality—traits now associated with the art of the Cultural Revolution. Mobilization for economic development was acceptable to the leadership, but grand visions now risked political conflict. Politically, it was more expedient for artists to brood on the troubles and resentments of daily life.

The theories of Jiang’s reformation, including both the Nietzschean impulse and the orthodox Maoist call for artistic engagement with the masses, were reversed with market-driven mass media. Cinema in this period degenerated into violent pornography; many films made in this period, like the 1988 productions Silver Snake Murders and Obsession, could not be released to overseas markets without extensive cuts by local censorship boards and cannot be screened in China today. Experiments in stream-of-consciousness work, abstract impressionism, and performance art became popular.

Compared with Jiang’s mobilization of the best artists and musicians into large-scale productions with heroic ideological goals, the new era was a managed descent into cultural chaos. The ideal artist was now an entrepreneur that could keep themselves afloat on the seas of the market economy. Locked into private competition, shock and vulgarity were the best ways to inch ahead of one’s rivals. It was not conducive to heroic impulses or high-minded political action.

The “Campaign Against Spiritual Pollution Debates” and “Campaign Against Bourgeois Liberalization” were launched in 1983 and 1986 as attempts to rein in the excesses by restoring guard rails on expression, but reformers allied with Deng ultimately cut these campaigns short. The intellectuals and artists that the party gave space to repudiate the Cultural Revolution kept going right up until the summer of 1989 when China was rocked by nationwide protests.

The years since 1989 have seen an attempt to contain what was unleashed by this cultural free-for-all. This has sometimes involved marketization, banking on the fact that existentialism is not profitable, but also an abortive revival of the Jiang Qing line. The Central Ballet staged Red Detachment of Women for the first time since the Cultural Revolution in 1992. China Central Television still broadcasts new productions of Taking Tiger Mountain by Strategy, and the films made under Jiang Qing’s leadership in the 1970s were never actively suppressed.

But it is hard to find the heroic aesthetic of the Cultural Revolution in the official art promoted since 1989. Jiang Qing commanded high art for the masses, without any competition from the market. The newer works merely ape some of the principles.

The worthwhile lesson of Jiang Qing is in her refusal to impose powerlessness and victimhood on her subjects. She refused to sanction what Pierre Bourdieu, invoking Nietzsche, once called a “sociologically mutilated being” as a model of human excellence. Instead, she invited the masses at gunpoint to contemplate beauty and strength. The power of her project can be seen in the transformative chaos of its age. As she learned from Lu Xun, also invoking Nietzsche, the artist must be capable of driving men mad.

The popular audience for Jiang’s elite high art was large and enduring enough that these works were performed long after the appreciation mandated by the Cultural Revolution had ended. Folk culture was not, in practice, displaced; instead, it existed alongside a popular audience for the revolutionary ballets. The goal of Jiang’s art was not to push aside all that came before; it was to absorb and transform it. In her vision, the dominant must not impose ressentiment on the dominated—to do so would be aesthetically disgusting. Jiang’s heroes were personalities to aspire to, not moral battering rams. This vision was accomplished by nurturing individual and collective creativity, pursuing technical perfection, and tolerating the transgression of traditional ethics.

These were Jiang’s lessons for China and artists. The tyranny of irony can be cast off by heroic sincerity. Mythology can become a true ethos. By giving up on victimhood, one gives up on misery. Without the narcissistic compulsion for representation of one’s petty flaws, it is possible to imagine true heroes.

The pinnacles of such art require the same kind of mass mobilization as any other achievement of modern society. As far back as the 1920s, directors like Fritz Lang commanded masses of people and machines with a firm hand to create masterworks of cultural production. But this apparent stiffness shelters the artist’s disruptive impulse. Jiang tolerated the transgressions of once-in-a-lifetime geniuses like Xue Jinghua or Yu Huiyong for a reason. The real crime she did not allow was the aestheticization of petty transgressions into ideals.

Jiang was under no illusions that the average viewer would be directly transformed into a great hero by their aesthetic experience. Her own “Three Prominences” assume that such heroes are few. But by refusing to valorize the sociologically mutilated individual, Jiang swept away the conditioning of powerlessness and victimhood. Her struggle was to inculcate a new heroic consciousness. In her works, the enemy became an adversary against which the heroes test their courage, nobility, and commitment to the cause. Jiang does not allow her villains to produce envy and deforming hatred in her protagonists or her audience. Instead, the fate of the enemy is that they will be forgotten entirely in the glorious finale, swept aside by the unstoppable, superior personalities of the protagonists.

Jiang’s core message, and her alternative to the celebration of victimhood by contemporary cultural orthodoxy, was the power of heroic ideals to make even overwhelming opposition irrelevant. Armed with her culture of self-justifying strength and beauty, her noble-souled heroes cast off any thought of victimhood to pursue their own glorious visions for their own sake.” - Dylan Levi King, “Madame Mao's Nietzschean Revolution”, (Palladium Magazine; 17 March 2023)

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Welcome to The Sims 2! Part 36

Saturday, July 17, 2004 - 23:00

Greetings, Sims Fans!

Yesterday was an EA event called Hot Summer Nights, and apart from the fact that it was held largely during daytime hours, and the weather was quite mild, it absolutely lived up to its name! For HSN, EA rolled out all our upcoming titles, including The Sims 2, for the press to get a gander at. We really wanted to just blow them away with the game by letting them see more than we had a chance to show at E3. Even though the day gets a little blurry towards the end, fear not – I was taking notes for your benefit. Here they are, completely unexpurgated:

Approximately 2PM – The press are assembled, and you can tell even now that they're impressed. You should see their jaws drop when the see the huuuuge poster for The Sims 2 that we hung in our cafeteria in their honor. Wait til they get to play the game! Oh look, Jonathan Knight just brought me a drink. Thank you, Jonathan!

Approximately 4:15 PM – People loves this game even more than they love the open bar, and that's saying something! Oh, how nice! Now Tim LeTourneau has brought me a drink! My team loves me – they keep bringing me things to drink!

Approximately 5:45 PM – I looooove you guys! You're all withour a doubt the besrest commumity in the whoooole world. Sims 2 rocks!!!!

Approximately 7:15 PM – I gotta sit down.

Approximately 7:30 - ...

[The remainder of this week's Lucy Mail will be completed by Jonathan Knight and Tim LeTourneau]

Approximately 9 PM – What an amazing success today was! While you wait for the press' reactions, we have a little Body Shop challenge for you: Using the photos included in this email as reference, create Sims of either Lucy, Tim or Jonathan and upload them to The Exchange. Then email [email protected] and include a link to your creation, so we can view it. Everyone who participates will get a cool blow-up Plumb Bob, and we'll give a Sims 2 shirt to the best of the lot. You have from now until next Friday to qualify for any of the prizes, so hop to it, gang!

Don't forget to check out these pics from the big day:

Happy Simming!

Jonathan Knight & Tim LeTourneau (as proxies for Lucy Bradshaw)

19 notes

·

View notes

Note

i want to ask so many :D 15, 21, 27, 35?

Thank you, I love having so many to answer! :D

15. Which genre(s) are your favorite?

Ahhh, hard to choose! Probably horror, if I had to choose only one, but I'm also very big on historical nonfiction, fantasy/sci-fi (with a slightly preference for fantasy), and in the last few years I've gotten really into mysteries.

21. The book(s) on your school reading list you actually enjoyed.

I (obviously) did not have a school reading list this year, but back in the day one of my high school teachers had us read Rosencrantz & Guildenstern Are Dead and I was, as is only appropriate for a teenager in fandom, completely obsessed. If you haven't read it, it's a Tom Stoppard play that's literally fanfic of Hamlet, all about what the characters do when they're not "on stage", and how they deal with being fictional, and questions of fate and randomness and art. It's extremely meta and slashy and sad and also hilarious. It also contains this quote, which is from the acting troupe within the play, but comments on the nature of fiction in general:

We’re more of the blood, love, and rhetoric school. [...] I can do you blood and love without the rhetoric, and I can do you blood and rhetoric without the love, or I can do you all three concurrent or consecutive, but I can’t do you love and rhetoric without the blood. Blood is compulsory — they’re all blood, you see.

Which (again, as is appropriate for angsty 17 year olds) I definitely used as a blog header for a few years. Also, I just read a OFMD fic that used the same quote as a thematic point and I need to find the time to write the author a long comment because it was SO GOOD.

27. What was the first book you remember reading as a kid?

I have a terrible memory and have no idea what the first book I read was. But I do remember being fairly young and obsessed with an edition of Grimm's Fairy Tales I somehow had. It had been read often enough that the cover had fallen off, so I must have gotten it second-hand, but I don't know if someone gave it to me or what. It was mostly unexpurgated and had creepy Arthur Rackham illustrations, and I remember being young enough to have this sense that I wasn't really supposed to be reading it, that no one knew I had this gory book full of child murders and torture and talking heads, so I only read it in secret. The drawing of the witch all wrapped up in the thorn bush (under "Sweetheart Roland" at the link above) still haunts my dreams.

35. Least favorite trope in your most favorite book genre.

I haaaaaate the Chosen One trope, and it is in so many fantasy novels. Particularly I hate the variety of it that goes "many people have tried to do X (where X = pull the sword out of the stone, kill the evil king, etc, whatever grand deed needs doing in this story), and they have all failed, but here comes the Chosen One, and they will immediately succeed, because they're just so much more ~special~ than anyone else, or because they really ~believe in themselves~, and I guess all the people who failed before and therefore died tragically and/or had to learn to live in the wake of their failure and ruined dreams can just fuck themselves, shoulda had more hope, I guess".

(Weirdly, the place this trope hit me the hardest recently was not a book, but Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse. And I do! get! that there is important significance to having the One Who Finally Succeeds be a Black boy! But it's still a trope I dislike.)

Book meme!

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Frances Lengel (aka Alexander Trocchi) - Desire and Helen - publisher uncertain - circa 1967

#witches#aussies#occult#vintage#desire and helen#frances lengel#alexander trocchi#circa 1967#complete & unexpurgated#first american printing

125 notes

·

View notes

Text

A completely disproportionate anger. More than angry, I was appalled, frightened. The injustice and irrationality of it. I was filled with bitterness. I returned home. I couldn’t control the weeping.

Anaïs Nin - 'Trapeze: The Unexpurgated Diary of Anaïs Nin, 1947–1955'

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

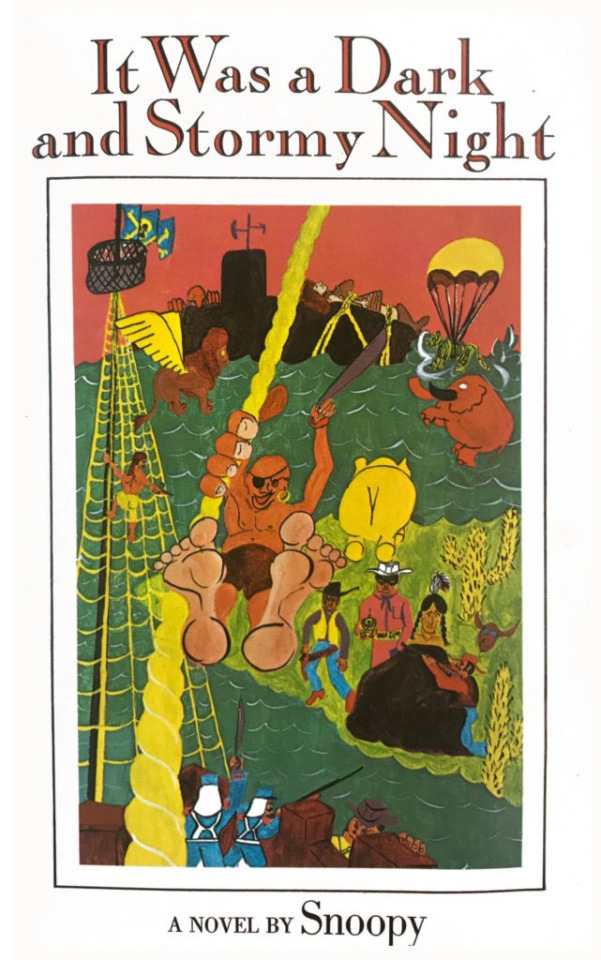

Snoopy and "It Was a Dark and Stormy Night" (Book, Charles M. Schulz, 1971)

The creation, and complete unexpurgated text, of the Great American Novellaellaella, with book-within-the-book cover art by one Lucille van Pelt. You can digitally borrow it here. You can read an article about it here.

#internet archive#book#books#peanuts#comic#comics#comic strip#comic strips#newspaper comic#newspaper comics#snoopy#literature#metafiction#1971#1970s#1970's#70s#70's

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

I leave him completely shattered.

Anaïs Nin, from The Unexpurgated Diary of Anaïs Nin, 1931-1932

#quotes#poetry#literature#poetry by women#anaïs nin#The Unexpurgated Diary of Anaïs Nin: 1931-1932#themes: untagged

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

Pepys’ diary was not only old by the point when Dracula was written, it was also written in shorthand (and in a mixture of languages to obfuscate the meaning). It was first formally decoded and published in around 1825, and two newer editions had been published recently (one a decade or so earlier and one a few years earlier) when Dracula came out. (Although it wasn’t until the 1970s that a complete, unexpurgated edition was published… Pepys spent a fair amount of time talking about his sex life and by the 19th century that was considered obscene.)

The Spectator [19th century British magazine] thought that while Stoker made admirable use of “vampirology,” the story might have been better had it been set in an earlier period. “The up-to-dateness of the book—the phonograph, diaries, typewriters, and so on—hardly fits in with the mediaeval methods which ultimately secure the victory for Count Dracula’s foes.”

On the subject that contemporaries thought that Dracula was too up-to-date for a vampire story.

6K notes

·

View notes

Text

The Lincoln-Douglas Debates

This book edited by Harold Holzer claims it is “The first complete unexpurgated text,” meaning it’s the most accurate transcription of the debates, for the most part using the opposition newspapers’ transcriptions which presumably did not edit out any errors. He tells us, “Speaking from text, Lincoln was perhaps the most eloquent orator of his age. But as an impromptu speaker, he could be…

View On WordPress

0 notes