#advaita vedānta

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

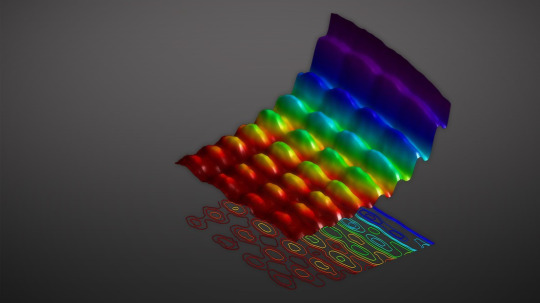

Light is both a wave and a particle.

Right. Sounds like cognitive dissonance, non-dualistic Hinduism ("Atman is Brahman"), or Shimmer ("it's a floor wax AND a dessert topping.")

Albert Einstein suggested that light is not only a wave but is also a stream of particles.

But the damn duo would never pose for photos. Until now.

Now, using electrons to image light, scientists at EPFL have succeeded in capturing the first-ever photo of this dual behavior of light behaving both as a wave and as a particle.

#quantum physics#particle#wave#particle and wave#photo of particle and wave#Laboratory for Ultrafast Microscopy and Electron Scattering#Ecole Polytechnique Federale de Lausanne#epfl#© Fabrizio Carbone#spatial interference and energy quantization#quantum mechanics#Advaita Vedānta#buddhism#shimmer floor wax and dessert topping snl

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Madhusudana Sarasvati

O intelectual hindu bengali Madhusūdana Sarasvatī (fl. 1500–início de 1600) foi um dos últimos grandes expositores pré-coloniais da tradição da filosofia/teologia não dualista sânscrita conhecida como Advaita Vedānta. Madhusūdana floresceu durante o reinado do Imperador Akbar (1556–1605), e era bem conhecido pela corte Mughal na época da composição do Jūg Bāsisht¹; com base nos dados disponíveis, ele muito possivelmente viveu durante o reinado de Jahāngīr (1605–27) e uma parte do reinado de Shāh Jahān (1627–58) também. Nascido em Bengala, Madhusūdana passou grande parte de sua carreira acadêmica em Varanasi (Vārāṇasī), um grande centro de aprendizado de sânscrito onde a tradição Advaita Vedānta, em particular, desfrutava de um status proeminente. Entre as composições de Madhusūdana está seu comentário sobre o Śivamahimnaḥ-stotra de Puṣpadanta, conhecido como Mahimnaḥ-stotra-ṭīkā; contido neste comentário, e mais tarde circulado como um tratado independente, está a bem conhecida doxografia sânscrita de Madhusūdana, o Prasthānabheda (“As Divisões das Abordagens”), que este capítulo considerará com algum detalhe. Aproximadamente na mesma época, Madhusūdana também escreveu sua obra filosófica mais influente, o Advaitasiddhi (“O Estabelecimento do Não-Dualismo”), em resposta à crítica estendida do pensamento Advaita oferecida no Nyāyāmṛta de Vyāsatīrtha (m. 1539), uma figura proeminente na escola rival do Dvaita (“dualista”) Vedānta. Uma vibrante tradição de comentários se liga ao Advaitasiddhi e às outras obras de Madhusūdana até o período colonial e continuando até o final do século XX, uma das várias atestações do impacto duradouro e poderoso de Madhusūdana dentro dos círculos intelectuais sânscritos. Do período colonial em diante, além disso, Madhusūdana exerceria um tipo diferente de influência nos esforços nacionalistas orientalistas e hindus para articular uma identidade “hindu” essencialista e unificada, na qual seu Prasthānabheda desempenhou um papel.

Os próprios tratados de Madhusūdana revelam muito pouco sobre os detalhes de sua vida, além de seus professores e (de forma útil) os outros tratados que ele escreveu, enquanto nenhum outro registro foi descoberto que pudesse fixar suas datas ou local de nascimento sem sombra de dúvida. No entanto, vários estudiosos modernos se esforçaram para extrair cada gota potencial de informação biográfica de seus escritos — os debates sobre as datas de Madhusūdana poderiam quase constituir um subcampo por si só! — enquanto um corpo considerável de lendas locais, histórias orais e outros dados anedóticos também foram trazidos para o tópico. Embora classificar os dados confiáveis dos não confiáveis possa envolver suposições incertas, no mínimo, uma imagem provável da figura pode ser alcançada, juntamente com alguns episódios biográficos possíveis e menos certos. Além disso, estudiosos modernos também utilizaram a linhagem de ensino de Madhusūdana em uma tentativa de reconstruir as redes sociais e intelectuais das quais ele participou.

É geralmente aceito que, com toda a probabilidade, Madhusūdana veio da região de Bengala. Em uma de suas primeiras obras, o Vedāntakalpalatikā, Madhusūdana faz duas referências à divindade Jagannātha de Puri como o ���Senhor da montanha azul” (nīlācala), uma forma de Kṛṣṇa associada à região da atual Orissa, no leste da Índia. Este local era um importante centro de peregrinação para os bengalis, particularmente aqueles associados ao movimento bengali Vaiṣṇava de Caitanya (falecido em 1533), que estava ganhando impulso considerável na época de Madhusūdana. P.M. Modi argumenta, com base em certas referências a Varanasi no Advaitaratnarakṣaṇa, Gūḍārthadīpikā e Advaitasiddhi de Madhusūdana, que ele também deve ter vivido lá por um tempo, dando assim credibilidade aos relatos tradicionais esmagadores de Madhusūdana conduzindo seus ensinamentos e escrevendo de lá. Em seu Advaitasiddhi e Gūḍārthadīpikā, Madhusūdana também menciona um de seus preceptores em nyāya (lógica), Hari Rāma Tarkavāgīśa, com quem Madhusūdana provavelmente estudou em Navadvīpa, um dos principais centros de aprendizado de nyāya. Em sete de seus tratados, Madhusūdana menciona ainda Viśveśvara Sarasvatī como seu guru āśrama, isto é, o preceptor de quem ele recebeu iniciação no modo de vida renunciante (saṃnyāsa), provavelmente em Varanasi; no Advaitasiddhi, Madhusūdana menciona adicionalmente Mādhava Sarasvatī como “aquele por cuja graça [eu] compreendi o significado das escrituras”, isto é, seu instrutor nas disciplinas de mīmāṃsā e vedānta, provavelmente também em Varanasi. Em seus próprios escritos, Madhusūdana cita com mais frequência, entre seus predecessores Advaita, as figuras de Śaṅkarācārya, Maṇḍaṇa Miśra, Sureśvara, Prakāśātma Yati, Vācaspati Miśra, Sarvajñātman Muni, Śrī Harṣa, Ānandabodha e Citsukha.

Além deste esboço biográfico bastante fino disponível nos próprios escritos de Madhusūdana, os estudiosos tiveram que confiar em fontes externas mais questionáveis para mais detalhes de sua vida. P.C. Divanji e Anantakrishna Sastri, por exemplo, coletaram vários relatos de famílias paṇḍit em Bengala e Varanasi que reivindicam Madhusūdana como ancestral, juntamente com um pequeno corpus de crônicas familiares e históricas — mais proeminentemente, um manuscrito intitulado Vaidikavādamīmāṃsā — que afirmam o nascimento e a linhagem bengalis de Madhusūdana. Esses materiais dão o nome de nascimento de Madhusūdana como Kamalanayana (ou Kamalajanayana), um dos quatro irmãos nascidos em Koṭālipāḍā no distrito de Faridpur, no leste de Bengala. Diz-se que sua família migrou do supracitado Navadvīpa, em Bengala Ocidental — o grande centro de aprendizado de Nyāya e do movimento devocional Caitanya (bhakti) — onde, após seu aprendizado inicial com Hari Rāma Tarkavāgīśa, o jovem Kamalanayana foi enviado para aprender Nyāya mais avançado com o célebre Mathuranātha Tarkavāgīśa (fl. ca. 1575). Foi daqui que Kamalanayana teria resolvido se tornar um renunciante (saṃnyāsin), e então partiu para Varanasi. Lá, Kamalanaya teria se tornado “Madhusūdana” após seu encontro com Viśveśvara Sarasvatī, que o iniciou em saṃnyāsa; Madhusūdana também empreendeu seu treinamento em mīmāṃsā e vedānta sob Mādhava Sarasvatī nessa época. Quando ele começou a compor seus próprios numerosos tratados, a reputação de Madhusūdana como um estudioso e sábio cresceu a ponto de atrair vários discípulos; ele também ganhou uma reputação como um grande devoto de Kṛṣṇa até sua morte aos 107 anos em Haridvār.

Translating Wisdom: Hindu-Muslim Intellectual Interactions in Early Modern South Asia- Shankar Nair

¹ - Tradução persa do Laghu Yoga-Vasistha.

#madhusudana sarasvati#advaita vedanta#vedanta#império mogol#laghu yoga-vasistha#hinduismo#planejo traduzir o Advaitasiddhi em breve!#me desejem sorte#traducao-en-pt#cctranslations#translatingwisdom-sn#dvaita vedanta#bengala#vishnuísmo#varanasi#prasthanabheda#advaitasiddhi

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Qual a visão do Vedānta sobre o budismo?

"Esse conhecimento acerca da Última Realidade, não dual e caracterizada pela ausência da diferenciação do conhecimento, objeto de conhecimento e conhecedor, não é o mesmo tal como foi declarado pelo Buddha. A visão do Buddha da qual rejeita a existência dos objetos externos e asserta a existência da consciência, somente, é similar ou bem próximo da verdade do Ātmā não dual. Mas esse conhecimento não dual que é a máxima Realidade pode ser somente obtida pelo Vedānta."

~ Comentário ao Māṇḍūkyopaniṣad, Śrī Śaṅkarācārya.

Aqui, Bhagavatpāda Śaṅkara afirma que a doutrina do Buddha é distinta do Vedānta Advaita. Apesar de ser um estabelecimento próximo, ainda não chega na absoluta verdade não-dual da doutrina pura do Veda.

Śrī Mātre Namaḥ.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Songbird of Dvaita: Sripadaraja’s Harmonies with the Divine

In the annals of spiritual history, Sripadaraja (Śrīpādarāja), also known as Lakshminarayana Tirtha, stands as a beacon of devotional fervour and philosophical clarity. Born in the 15th century, this saint harmonized Dvaita Vedānta—the dualistic philosophy of Madhvacharya—with the universal language of music. Revered for his profound contributions to the Haridasa movement, Sripadaraja transformed the sacred act of devotion into a symphony of transcendence, blending the intellectual rigor of Vedantic thought with the soulful expressions of bhakti.

The Divergent Legacy of Sripadaraja

At the heart of Sripadaraja’s teachings lies the principle of duality as a conduit to divine unity. Unlike Advaita Vedanta, which posits an absolute oneness, Dvaita Vedanta emphasizes the eternal distinction between the soul (jīva) and the Supreme Being (Ishvara). Sripadaraja’s genius was his ability to translate this philosophy into an accessible, experiential form through music and poetry.

For Sripadaraja, devotion (bhakti) was not merely an act of worship but a profound dialogue between the finite and the infinite. His compositions, rich with metaphors of nature and daily life, serve as spiritual bridges, allowing seekers to navigate the chasm between the temporal and the eternal. His works encapsulated the essence of surrender, where the devotee’s soul, like a bird, soars toward the divine through melodies that dissolve ego and awaken the heart.

Spirituality Through the Lens of Music

Sripadaraja believed that music was a divine gift, a language that transcends intellect and speaks directly to the soul. He used his compositions to teach complex Vedantic concepts in a way that even the unlettered could grasp. His songs were not mere recitations but vibrant, living entities that invoked the presence of God in every note. In his view, the act of singing was itself a form of yoga—a union with the divine. The vibrations created through singing or listening to such sacred music cleanse the mind and elevate the soul.

His philosophy emphasized the importance of humility in spiritual practice. Just as a bird’s song rises unbidden and selflessly, a devotee’s prayers should flow without ego, filled with love and surrender. This unique perspective challenges the modern seeker to approach spirituality not as a transaction but as a heartfelt offering.

The Practical Toolkit: Harmonizing Life with the Divine

To integrate Sripadaraja’s teachings into daily life, consider adopting this practical toolkit inspired by his legacy:

1. Daily Devotional Singing

Dedicate 15 minutes each morning to singing devotional songs (kirtans) or chanting mantras.

Focus on the intent rather than the technical perfection of your singing.

Choose compositions that resonate with your spiritual path; for instance, Sripadaraja’s own works like "Pada Narayana" can be a starting point.

2. Nature-Inspired Meditation

Spend time observing the sounds of nature—birds, wind, water—and use them as meditative anchors.

Reflect on how these natural melodies mirror the unspoken dialogue between the jīva and Ishvara.

3. The Practice of Duality Awareness

Begin your day with a moment of gratitude for the divine presence within and outside you.

Contemplate on how the distinct roles of the individual and the divine coexist in harmony, much like a singer and the melody.

4. The Soul’s Diary

Maintain a journal where you write a few lines daily about your inner spiritual dialogues.

Use metaphors from Sripadaraja’s compositions to deepen your reflections.

5. Community Singing Sessions

Organize or join satsangs where devotional songs are sung collectively.

Experience the synergy of shared devotion, which amplifies the spiritual vibrations.

6. Instrumental Spirituality

Learn to play a simple musical instrument like a veena or harmonium, focusing on sacred melodies.

Dedicate this practice as an offering to the divine, regardless of your skill level.

7. Ego Dissolution Exercise

Every evening, engage in a practice of self-reflection. Ask yourself: “Did I approach today’s actions with humility and love?”

Let go of one ego-driven thought or action as a symbolic act of surrender.

The Takeaway

Sripadaraja’s life and teachings remind us that spirituality is not confined to grand rituals or esoteric philosophies. It is in the simple, heartfelt offerings—a song, a thought, a moment of surrender—that the divine reveals itself. In a world increasingly drowned in noise, his message is a clarion call to return to the melody of the soul.

As the Songbird of Dvaita, Sripadaraja’s legacy invites us to become instruments of the divine, resonating with the eternal symphony of love and devotion. May his harmonies inspire us to find our unique notes in the grand orchestra of life.

#Sripadaraja#BhaktiAndWisdom#DvaitaPhilosophy#VedantaTeachings#HaridasaMovement#SpiritualHarmony#DevotionalPath#SacredWisdom#IndianSaints#BhaktiYoga#DivineKnowledge#SoulfulSpirituality#InnerAwakening#TimelessTeachings#SpiritualJourney

0 notes

Text

Notes from a lecture by TKV Desikachar - 'Is Veda a Religion?'

The Brahma Sūtra is the source of Hinduism or Hindu Philosophy or Vedānta. It acknowledges the Veda as the source of its teachings, hence the term Vedānta, within which there are three main streams: 1. People who believe in One (Advaita or school of non-dualism advocated by Śaṅkara) 2. People who believe in One with certain characteristics (Viśiṣṭādvaita or school of qualified non-dualism…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Photo

August Meditations MMXXI

It’s been nine years since I started August Mediations. Its beginning coincidentally marked the start of monumental changes in my outer life that continue today. Health matters and deaths in my birth family, some sudden, some protracted, are the mainstay of these changes. The passing of my mother finally led to my becoming the executor of her estate. A matter that will soon end and, perhaps, mark the end of this cycle in my life.

I would be remiss if I didn’t include in these changes the Covid-19 pandemic that continues in the world today. The ensuing social isolation that it brought led me to the internet where I found much material on non-duality. Non-duality, or Advaita Vedānta, is a school of Hindu philosophy that refers to the idea that Consciousness alone is real and the self an illusion.

A central point of non-duality is that there is nothing that the self can do to cause enlightenment. An idea that I was not unfamiliar with but which I never explored in depth. The material I found on the internet was irrefutable. Sage after sage confirmed that nothing they ever did, no meditation, no chanting, no selfless service caused their enlightenment. Many, in fact, even denied there was such a thing as enlightenment, citing only that there had been a ‘change in perspective’ that accompanied the realization that there is no self.

Being unable to deny what the non-dualists said brought about a low-level depression in me that lasted for most of the summer and early fall of 2020. An understandable result of realizing that there was absolutely nothing I could do to fulfill what I always saw as my life’s purpose. With this, however, came the growing realization that there was also no need to fix anything. The grace that leads to your true nature comes regardless of one’s mental or physical state. In fact, it comes in woe as easily as in joy.

I came out of my depression realizing that despite what the non-dualist were saying, there is a place for spiritual practice. Those who realized no self without any former spiritual practice or knowledge often found themselves unable to comprehend what had happened. It took years to integrate their sudden enlightenment into their lives. It’s true that none would say that had they had a spiritual practice it would have been easier. But that positioned seemed to rise mostly from an unwillingness to speculate about what may or may not have been. Non-dualists, you see, are big on ‘what is,’ not on what may have been in the past or may be in the future.

Once I got past the idea that my spiritual practice was a wasted effort, I began to see that much of what I had been doing could fall under the category of integrating my shadow into conscious awareness. In analytical psychology, the shadow is either an unconscious aspect of the personality that the conscious ego does not identify as itself, or the entirety of the unconscious, i.e., everything of which a person is not fully conscious. In short, the shadow is the unknown side.

Non-dualists generally agree that integration of the shadow follows the realization that there is no self. What integration means, however, is not clear. At least not from what I’ve come across. For me it’s involved facing fear. A fear of inadequacy that, if seen, would result in various catastrophic outcomes. The worst of which being loss of control and physical death. All of which are core fears of an ego that ultimately knows it is an illusion but desperately seeks to keep its identity intact.

It is not surprising that the last nine years have brought many opportunities to see through my feelings of inadequacy. Taking care of my mother in the last five years of her life and now wrapping up the estate during a pandemic has provided me ample proof that I can handle life as it’s presented to me. The health problems that brought me close to death did likewise, although I must admit I’ve still a ways to go.

Despite what the non-dualists say, I do believe that there is a place for spiritual practice. And I’m not entirely convinced that there is no self. Certainly, the ego as a complex web of thought and emotion is ultimately unreal. Much in not all of it does dissolve when the ‘shift in perspective’ gracefully comes about. But is it not possible that a non-conceptual, non-localized Self continues? Whatever that means?

So, to wrap up this post, another year of August Meditations begins with this page. As this past year found me less motivated to continue the site it may be that this coming year will find that I stop posting altogether. Who knows? Maybe stopping, as Gangaji said, is the only way to realize one’s true nature?

1 note

·

View note

Text

For Jīva, the Brahman aspect is non-personal consciousness—the ātman/puruṣa goal of some of the Upaniṣads, the Yoga Sūtras, and most other ātman-seeking traditions, including advaita Vedānta. In the sun metaphor, it can be analogized with the formless, quality-less, all-pervading light: “You are also that Brahman, the supreme light, spread out like the ether” (Bhāgavata IV.24.60).

But the point in this analogy is that light emanates from a higher source, the sun. Nonetheless, within this impersonal effulgence, there are myriad individualized ātmans that, like the sun-ray particles, can partake of and “merge into” the greater body of the all-pervading light. Thus, this experience is one of eternality and infinity, devoid of all objects other than blissful consciousness itself. As the light of numerous small autonomous flames can radiate out and coextensively “merge” into one greater generic body of light, while yet remaining the light of multiple individual flames, so the consciousness of myriad ātmans can all “merge” into Brahman, sharing in one infinite, blissful, eternal experience of pure contentless awareness itself, while yet remaining distinct ātmans, according to Vaiṣṇava thought (and, for that matter, the philosophies of Sāṅkhya and Yoga).

[...]

The Absolute is thus not monolithic, standardized, or, so to speak, one-size-fits-all. The aspect of the Absolute that appears coherent and appealing to any particular individual is a reflection of that person’s presuppositions (which, in yoga categories, are nothing other than previously cultivated saṁskāras, mental imprints, embedded in the citta, quite likely from previous lives). In actuality, one generally simply accepts the theological and metaphysical specifics of the tradition to which one connects, either because of inherited cultural or family reasons or because of being inspired by a charismatic guru figure whose lineage one simply adopts out of faith, as noted previously.

In any event, the aspect of the Absolute one perceives is a reflection of the perceiver: “Although Bhagavān is one, he is approached through different mind-sets and perspectives [of the perceivers] and so perceived variously as the person Īśvara, as Paramātman or as Brahman, pure consciousness” (III.32.26).

-- Edwin Bryant, Bhakti Yoga

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

“I hinted above, for instance, at my belief that the very thing that the great theologians of Nicene tradition recognized as the pervasive if mysterious rationality of the whole of Christian tradition—the miraculous exchange of natures between God and creatures, God becoming human that humans might become God—is still the aspect of Christian doctrine and theology that needs to be thought through to its radical, if inevitable, conclusions. And it seems to me also that, obedient to the call of that antecedent finality and cosmic destiny, Christian thinkers might find it worthwhile fruitfully to draw on resources outside the historical, cultural, and even religious continuum of the tradition as currently understood. The example I suggested (and one perhaps peculiarly close to my heart) was that of Vedānta (whether Advaita or Viśiṣṭādvaita); other possible examples, however, are legion. Just as Christian thought in late antiquity naturally drew upon Platonic tradition not only to enunciate, but better to understand, its doctrinal content, there is no reason why these other remarkable traditions should not also come to inform Christian self-understanding. I am convinced, at the very least, that there are certain dimensions of the great Christian narrative of divine and human communion in Christ—both necessary logical premises and necessary logical conclusions—that have rarely been fully articulated in the tradition, except in rare instances, often at the boundaries, and in a largely mystical vein; and I am no less convinced that, say, the thought of Āḍi Śaṅkara might cast new light on, for instance, the thought of Maximus, and that this in turn might cast new light on the tradition as a whole. I would even argue that the whole rationality of the Christian tradition—creatio ex nihilo, divine incarnation, human deification, the vivifying Spirit of God breathed into humanity, and so forth—entails and requires a kind of metaphysical monism that has only sporadically manifested itself within the tradition, but that certain schools of Vedānta (not to mention certain schools of Sufism) have explored with unparalleled brilliance. But it would be wrong, I hasten to add, to see this process merely as the appropriation of foreign sources for purposes that would be alien to them." - David Bentley Hart

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dedicating the remainder of my life to the ātma-vichāra practice of Advaita Vedānta.

5 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

Haqq al-Yaqin

Advaitic song. Ātman (IAST: ātman, Sanskrit: आत्मन्) is a central idea in Hindu philosophy and a foundational premise of Advaita Vedānta. It is a Sanskrit word that means "real self" of the individual, "essence", and soul.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hoy me presentaron a unos Yogis. Empezamos hablar de Advaita Vedānta, todo iba bien hasta que les dije que era nivel 27. Ya no creyeron que había trascendido, medio aprensivos los hippies.

Como siempre, haciendo amigos...

1 note

·

View note

Text

When quantum physics and Advaita Vedānta collide.

Quark, strangeness, and Om.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Doxografia de Madhusudana Sarasvati

No Siddhāntabindu, o comentário de Madhusūdana sobre o Daśaślokī, vemos um afastamento ainda maior do Prasthānabheda. Não só não há nenhum grupo no tratado que poderia concebivelmente representar o “Islam” ou os mlecchas, mas até mesmo o vocabulário básico de āstika e nāstika não é usado em lugar nenhum. Consequentemente, nas duas seções doxográficas do tratado, nenhuma estrutura é oferecida para distinguir os āstikas dos nāstikas, nem qualquer sugestão de qualquer tipo de hierarquia de escolas ou tradições. As visões são simplesmente apresentadas e, em seguida, refutadas em favor das visões dos “seguidores do Upaniṣad”, ou seja, Advaita Vedānta. O Siddhāntabindu, portanto, se recusa completamente a entreter qualquer noção de uma “unificação (proto-)Hindu” e, de fato, rotineiramente enfraquece a ideia. A estrutura do tratado, além disso, é relevante, pois Madhusūdana estrutura o Siddhāntabindu em torno do “grande ditado” (mahāvākya) “Aquilo és” (tat tvam asi). Agora, a tradição Advaita há muito considera a audição de tais mahāvākyas como o meio central, se não o único, de alcançar a libertação, embora dúvidas e confusões sobre a semântica dessas declarações védicas impeçam o amanhecer da realização dentro do aspirante. Refutar os materialistas, budistas e jainistas, juntamente com todas as outras escolas, consequentemente, desempenha a função soteriológica crucial de limpar ilusões e incertezas sobre os significados das palavras do mahāvākya — “você” é realmente seu corpo? Sua consciência? “Aquilo” é Deus o criador do mundo? Qual é, então, “seu” relacionamento com “aquilo”? — sem o qual mokṣa simplesmente não é possível. Em resposta à pergunta acima sobre por que os grupos “nāstika” há muito ausentes continuaram a se envolver nas doxografias modernas primitivas, então, esta estruturação do Siddhāntabindu fornece uma resposta clara: mesmo que os praticantes dessas tradições particulares não sejam mais encontrados, as dúvidas levantadas por suas ideias e argumentos podem persistir, criando confusões mentais e obstáculos contra a libertação dentro dos indivíduos vivos hoje que simplesmente devem ser abordados.

Essas duas ofertas doxográficas adicionais dentro do corpus de Madhusūdana, portanto, não ecoam de forma alguma as características distintivas e peculiares de seu Prasthānabheda. O que poderia explicar essa discrepância? Os estudiosos modernos geralmente consideram o Vedāntakalpalatikā e o Siddhāntabindu como duas das primeiras obras de Madhusūdana, dado que pelo menos uma delas é referenciada em quase todos os seus outros escritos. Acredita-se, além disso, que esses dois textos foram compostos na mesma época, uma vez que cada um menciona um ao outro. O Śivamahimnaḥ-stotra-ṭīkā, enquanto isso, faz referência explícita ao Vedāntakalpalatikā e contém uma referência discutível ao Siddhāntabindu. Parece bastante certo, portanto, que tanto o Vedāntakalpalatikā quanto o Siddhāntabindu foram compostos antes do Prasthānabheda. Poderia ser que os eventos na vida de Madhusūdana nos anos intermediários o levaram a desenvolver novas visões, ou, talvez, a enfatizar ou tornar explícitas certas visões que ele manteve mais silenciosas em seus anos mais jovens? Poderíamos apenas especular que, conforme Madhusūdana viajava por diferentes regiões do sul da Ásia — ou, talvez, conforme seu status se tornava mais proeminente e ele assumia novos papéis e responsabilidades — ele poderia ter percebido uma necessidade de certos tipos de ensinamentos em detrimento de outros. Alternativamente, se os contatos de Madhusūdana com muçulmanos aumentaram ao longo dos anos, talvez até mesmo na corte Mughal, isso poderia tê-lo levado a começar a repensar os limites de sua própria comunidade religiosa e intelectual.

Todas essas sugestões, no entanto, são inescapavelmente especulativas, como a maioria seria baseada na biografia tendenciosa de Madhusūdana. E, portanto, evidências mais concretas devem ser buscadas em outro lugar. Nesta frente, podemos nos referir a dois outros escritos de Madhusūdana: o supracitado Bhaktirasāyana, um tratado sobre bhakti (devoção), e o Gūḍārthadīpikā, o comentário de Madhusūdana sobre o Bhagavad Gītā, ele próprio também contendo um volume considerável de discussão sobre o tópico de bhakti. Com base nas referências cruzadas de Madhusūdana, fica claro que o Bhaktirasāyana é anterior ao Gūḍārthadīpikā, sendo o primeiro uma de suas primeiras composições. Como Lance Nelson descreve em sua comparação da apresentação de bhakti entre os dois textos, ocorreu uma discrepância significativa: no Bhaktirasāyana, Nelson argumenta, o jovem Madhusūdana corajosamente afirma para bhakti, contra a corrente de quase todas as tradições Advaita anteriores, um status igual, se não superior, ao de jñāna (conhecimento), enquanto ele defende o primeiro como um meio independente para mokṣa (libertação) disponível a todos, independentemente de gênero ou origem social. No “mais sóbrio” Gūḍārthadīpikā, em contraste, Madhusūdana “domestica” bhakti em sensibilidades Advaitin mais convencionais, restringindo a obtenção dos níveis mais altos de bhakti apenas aos brâmanes do sexo masculino que renunciaram formalmente ao mundo (saṃnyāsa). Embora, novamente, possa ser tentador atribuir essa mudança à “juventude exuberante” de Madhusūdana versus sua “maturidade sóbria”, Nelson discorda, dado que, no Gūḍārthadīpikā, Madhusūdana repetidamente remete seus leitores de volta ao Bhaktirasāyana, que “desautoriza a explicação simples de que, tendo mudado de ideia, ele repudiou o ensinamento de sua obra anterior”. Em vez disso, Nelson sugere que, entre as duas obras, Madhusūdana “está simplesmente falando para públicos diferentes e ajustando sua discurso de acordo”, visando aproximar os devotos bhakta educados de uma perspectiva Advaita, no primeiro caso, e recomendar bhakti aos seus companheiros renunciantes Advaitin, no segundo.

Embora eu veja Nelson como tendo exagerado a discrepância entre o Bhaktirasāyana e o Gūḍārthadīpikā, como mencionado acima, ele nos ofereceu uma chave promissora: a questão do público. O Vedāntakalpalatikā e o Siddhāntabindu, por exemplo, são, filosoficamente falando, textos bastante desafiadores, claramente destinados a leitores avançados de algum tipo, enquanto o Prasthānabheda é escrito em um estilo muito mais básico e acessível. De fato, o Prasthānabheda anuncia seu próprio público em sua seção de abertura: o tratado foi escrito “para o bem do cultivo de bālas”. Agora, um bāla pode ser um “novato” ou alguém “inexperiente” ou “falto de conhecimento”; o sentido mais literal de bāla, no entanto, é o de um “jovem” ou “criança”. Se seguirmos o sentido literal, isso significa que o Prasthānabheda foi destinado a jovens estudantes nos estágios iniciais de seus estudos, uma sugestão que está de acordo com a linguagem simples do texto e seu caráter excepcionalmente introdutório. Se refletirmos, adicionalmente, sobre o contexto original do Prasthānabheda antes de ser reinterpretado como um tratado independente, poderíamos facilmente imaginar uma história ligeiramente diferente, embora comparável: aproveitando o status do Śivamahimnaḥ-stotra como um poema devocional destinado a um amplo apelo popular, Madhusūdana poderia concebivelmente ter pretendido que seu comentário cumprisse uma função de educação pública. Dado o contexto intersectário do comentário, com um Advaitin Vaiṣṇava oferecendo uma interpretação de um hino Śaiva, Madhusūdana pode muito bem ter aproveitado a oportunidade de promover uma visão de uma tradição "védica" coerente e ecumênica, uma visão plausivelmente edificante de várias maneiras para um público "hindu" educado, mas não acadêmico, em geral. Em contraste, Madhusūdana nos conta que ele compôs o Siddhāntabindu para um de seus discípulos mais próximos, Balabhadra, enquanto a sofisticação dialética do Vedāntakalpalatikā pressupõe claramente um público inteligente já mergulhado no aprendizado do sânscrito e bem treinado no método filosófico. O público para essas duas últimas doxografias, em suma, é completamente diferente, e consideravelmente mais avançado escolástica e filosoficamente, do que para o Prasthānabheda.

Translating Wisdom: Hindu-Muslim Intellectual Interactions in Early Modern South Asia- Shankar Nair

#madhusudana sarasvati#islam#advaita vedanta#vedanta#prasthanabheda#traducao-en-pt#cctranslations#translatingwisdom-sn#sul da ásia#vishnuísmo#shivaísmo

0 notes

Text

Refutação de Śrī Madhūsudāna sobre um possível dualismo entre Māyā e Brahman no Advaita Vedānta:

"Mesmo a realidade da negação não implica no abandono da perspectiva Advaita. Já que a negação não é diferente de Brahman, o qual é o substrato da negação do mundo fenomênico. Nem o fato do mundo ser objeto de uma real absoluta negação implica que o mundo em si seja absolutamente real. Pois não achamos nenhuma realidade que pertence à concha que parece prata, que ainda é objeto de uma negação.

De outro modo, podemos dizer que a negação não tem nenhuma realidade. Mas até neste caso, a realidade da negação não é meramente aparente, mas relativa."

- Advaitasiddhi, Madhūsudāna Sarasvatī.

0 notes

Text

The Songbird of Dvaita: Sripadaraja’s Harmonies with the Divine

In the annals of spiritual history, Sripadaraja (Śrīpādarāja), also known as Lakshminarayana Tirtha, stands as a beacon of devotional fervour and philosophical clarity. Born in the 15th century, this saint harmonized Dvaita Vedānta—the dualistic philosophy of Madhvacharya—with the universal language of music. Revered for his profound contributions to the Haridasa movement, Sripadaraja transformed the sacred act of devotion into a symphony of transcendence, blending the intellectual rigor of Vedantic thought with the soulful expressions of bhakti.

The Divergent Legacy of Sripadaraja

At the heart of Sripadaraja’s teachings lies the principle of duality as a conduit to divine unity. Unlike Advaita Vedanta, which posits an absolute oneness, Dvaita Vedanta emphasizes the eternal distinction between the soul (jīva) and the Supreme Being (Ishvara). Sripadaraja’s genius was his ability to translate this philosophy into an accessible, experiential form through music and poetry.

For Sripadaraja, devotion (bhakti) was not merely an act of worship but a profound dialogue between the finite and the infinite. His compositions, rich with metaphors of nature and daily life, serve as spiritual bridges, allowing seekers to navigate the chasm between the temporal and the eternal. His works encapsulated the essence of surrender, where the devotee’s soul, like a bird, soars toward the divine through melodies that dissolve ego and awaken the heart.

Spirituality Through the Lens of Music

Sripadaraja believed that music was a divine gift, a language that transcends intellect and speaks directly to the soul. He used his compositions to teach complex Vedantic concepts in a way that even the unlettered could grasp. His songs were not mere recitations but vibrant, living entities that invoked the presence of God in every note. In his view, the act of singing was itself a form of yoga—a union with the divine. The vibrations created through singing or listening to such sacred music cleanse the mind and elevate the soul.

His philosophy emphasized the importance of humility in spiritual practice. Just as a bird’s song rises unbidden and selflessly, a devotee’s prayers should flow without ego, filled with love and surrender. This unique perspective challenges the modern seeker to approach spirituality not as a transaction but as a heartfelt offering.

The Practical Toolkit: Harmonizing Life with the Divine

To integrate Sripadaraja’s teachings into daily life, consider adopting this practical toolkit inspired by his legacy:

1. Daily Devotional Singing

Dedicate 15 minutes each morning to singing devotional songs (kirtans) or chanting mantras.

Focus on the intent rather than the technical perfection of your singing.

Choose compositions that resonate with your spiritual path; for instance, Sripadaraja’s own works like "Pada Narayana" can be a starting point.

2. Nature-Inspired Meditation

Spend time observing the sounds of nature—birds, wind, water—and use them as meditative anchors.

Reflect on how these natural melodies mirror the unspoken dialogue between the jīva and Ishvara.

3. The Practice of Duality Awareness

Begin your day with a moment of gratitude for the divine presence within and outside you.

Contemplate on how the distinct roles of the individual and the divine coexist in harmony, much like a singer and the melody.

4. The Soul’s Diary

Maintain a journal where you write a few lines daily about your inner spiritual dialogues.

Use metaphors from Sripadaraja’s compositions to deepen your reflections.

5. Community Singing Sessions

Organize or join satsangs where devotional songs are sung collectively.

Experience the synergy of shared devotion, which amplifies the spiritual vibrations.

6. Instrumental Spirituality

Learn to play a simple musical instrument like a veena or harmonium, focusing on sacred melodies.

Dedicate this practice as an offering to the divine, regardless of your skill level.

7. Ego Dissolution Exercise

Every evening, engage in a practice of self-reflection. Ask yourself: “Did I approach today’s actions with humility and love?”

Let go of one ego-driven thought or action as a symbolic act of surrender.

The Takeaway

Sripadaraja’s life and teachings remind us that spirituality is not confined to grand rituals or esoteric philosophies. It is in the simple, heartfelt offerings—a song, a thought, a moment of surrender—that the divine reveals itself. In a world increasingly drowned in noise, his message is a clarion call to return to the melody of the soul.

As the Songbird of Dvaita, Sripadaraja’s legacy invites us to become instruments of the divine, resonating with the eternal symphony of love and devotion. May his harmonies inspire us to find our unique notes in the grand orchestra of life.

#Sripadaraja#DvaitaPhilosophy#SpiritualHarmony#BhaktiMovement#DevotionalMusic#IndianSaints#SpiritualWisdom#VedantaTeachings#HaridasaLegacy#DivineMelody#SacredSymphony#MusicAndSpirituality#EgoToDivinity#BhaktiYoga#InnerJourney

0 notes

Text

Notes from a lecture by TKV Desikachar - 'Is Veda a Religion?'

The Brahma Sūtra is the source of Hinduism or Hindu Philosophy or Vedānta. It acknowledges the Veda as the source of its teachings, hence the term Vedānta, within which there are three main streams: 1. People who believe in One (Advaita or school of non-dualism advocated by Śaṅkara) 2. People who believe in One with certain characteristics (Viśiṣṭādvaita or school of qualified non-dualism…

View On WordPress

0 notes