#Women’s Suffrage Movement

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Women's Suffrage Movement

The movement for women's suffrage took many decades to obtain voting rights. Women fought for their rights via smart political strategy. Dynamic leadership attracted several generations of women – mothers, daughters, and grandmothers formed national organizations and made alliances that brought women into the political sphere. The fight intensified during World War I due to women's work outside the home to help the war effort. Women now saw themselves as fully deserving of the same rights as men.

A trio of outfits at the Daughters of the American Revolution Museum shows the evolution from the last gasp of Edwardian bulk to the short, simple dress of the Twenties. Left, a two-piece dress of about 1907 (Daughters of the American Revolution Museum). Center, a houndstooth suit of about 1914 (loan courtesy Shippensburg University Fashion Archives and Museum). Right, black and white day dress, 1925 (Daughters of the American Revolution Museum).

Exhibition vignette with the “Bear the Banner Proudly They Have Borne Before” banner, circa 1913-1920. National Woman’s Party. Belmont-Paul Women’s Equality National Monument, Washington, DC.

Purple, white, and gold were among the colors representing the movement. White dresses were worn by women as a representation of purity of thought and high-mindedness. Purple represented the vote and loyalty, constancy, and steadfastness. Gold stood for the torch that guides our way.

Ethel Wright (1866–1939) Christabel Pankhurst (British suffragette) • National Portrait Gallery, London

#fashion history#women's history#suffrage movement#women's voting rights#white dresses of the suffrage movement#colors of women's suffrage#daughters of the american revolution#late 19th – early 20th century women's fashion#the resplendent outfit art & fashion blog#ethel wright#woman artist#christabel pankhurst#suffrage fashion#historical photos

104 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Happy heavenly birthday to women's suffrage activist Mabel Ping-Hua Lee. 🕊️🤍

Lee was born in Guangzhou, China in 1897, and received a visa to study in the U.S. in 1905. Seven years later, at just 16 years old, she led a parade of 10,000 people through New York protesting for women’s suffrage.

Women were granted the right to vote in New York in 1917 and across the country in 1920. However, Chinese women including Lee were not afforded voting rights until 1943 because of the Chinese Exclusion Act — which prevented Chinese immigrants from becoming U.S. citizens.

While Lee continued to advocate for women’s suffrage, it remains unclear if she ever became a U.S. citizen or was able to cast a ballot. Her work, however, was instrumental in advancing women’s rights throughout the U.S. 🙏🏾

#mabel ping-hua lee#women's rights#women's suffrage#women's suffrage movement#chinese exclusion act#vote#voter#voting

71 notes

·

View notes

Text

Black people and women have been overqualified for every position in America since July 3rd, 1776. It is the progress of white people and of men to finally get over their racism and misogyny that is allowing people into those spaces. Remember that.

#woke is wonderful#empathy education#fight the patriarchy#smash the patriarchy#teaching empathy#empathy#women as property#black liberation#black people#black history#black people built America#blm movement#black literature#black stories#black art#black tumblr#blacklivesmatter#black is beautiful#women in government#women as sex objects#strong women#women voters#women voting#women's suffrage#violence against women#women#black women#1776#slavery#slavery in America

47 notes

·

View notes

Text

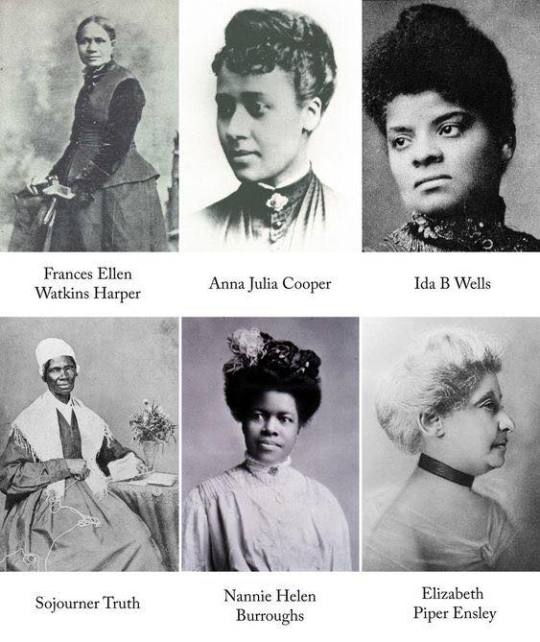

A Historical Deep Dive into the Founders of Black Womanism & Modern Feminism

Six African American Suffragettes Mainstream History Tried to Forget

These amazing Black American women each advanced the principles of modern feminism and Black womanism by insisting on an intersectional approach to activism. They understood that the struggles of race and gender were intertwined, and that the liberation of Black women was essential. Their writings, speeches, and actions have continued to inspire movements addressing systemic inequities, while affirming the voices of marginalized women who have shaped society. Through their amazing work, they have expanded the scope of womanism and intersectional feminism to include racial justice, making it more inclusive and transformative.

Anna Julia Cooper (1858–1964)

Quote: “The cause of freedom is not the cause of a race or a sect, a party or a class—it is the cause of humankind, the very birthright of humanity.”

Contribution: Anna Julia Cooper was an educator, scholar, and advocate for Black women’s empowerment. Her book A Voice from the South by a Black Woman of the South (1892) is one of the earliest articulations of Black feminist thought. She emphasized the intellectual and cultural contributions of Black women and argued that their liberation was essential to societal progress. Cooper believed education was the key to uplifting African Americans and worked tirelessly to improve opportunities for women and girls, including founding organizations for Black women’s higher education. Her work challenged both racism and sexism, laying the intellectual foundation for modern Black womanism.

Frances Ellen Watkins Harper (1825–1911)

Quote: “We are all bound together in one great bundle of humanity, and society cannot trample on the weakest and feeblest of its members without receiving the curse in its own soul.”

Contribution: Frances Ellen Watkins Harper was a poet, author, and orator whose work intertwined abolitionism, suffrage, and temperance advocacy. A prominent member of the American Equal Rights Association, she fought for universal suffrage, arguing that Black women’s voices were crucial in shaping a just society. Her 1866 speech at the National Woman’s Rights Convention emphasized the need for solidarity among marginalized groups, highlighting the racial disparities within the feminist movement. Harper’s writings, including her novel Iola Leroy, offered early depictions of Black womanhood and resilience, paving the way for Black feminist literature and thought.

Ida B. Wells (1862–1931)

Quote: “The way to right wrongs is to turn the light of truth upon them.”

Contribution: Ida B. Wells was a fearless journalist, educator, and anti-lynching activist who co-founded the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). Her investigative reporting exposed the widespread violence and racism faced by African Americans, particularly lynchings. As a suffragette, Wells insisted on addressing the intersection of race and gender in the fight for women’s voting rights. At the 1913 Women’s Suffrage Parade in Washington, D.C., she famously defied instructions to march in a segregated section and joined the Illinois delegation at the front, demanding recognition for Black women in the feminist movement. Her activism laid the groundwork for modern feminisms inclusion of intersectionality, emphasizing the dual oppressions faced by Black women.

Sojourner Truth (1797–1883)

Quote: “Ain’t I a Woman?”

Contribution: Born into slavery, Sojourner Truth became a powerful voice for abolition, women's rights, and racial justice after gaining her freedom. Her famous 1851 speech, "Ain’t I a Woman?" delivered at a women's rights convention in Akron, Ohio, directly challenged the exclusion of Black women from the feminist narrative. She highlighted the unique struggles of Black women, who faced both racism and sexism, calling out the hypocrisy of a movement that often-centered white women’s experiences. Truth’s legacy lies in her insistence on equality for all, inspiring future generations to confront the intersecting oppressions of race and gender in their advocacy.

Nanny Helen Burroughs (1879–1961)

Quote: “We specialize in the wholly impossible.”

Contribution: Nanny Helen Burroughs was an educator, activist, and founder of the National Training School for Women and Girls in Washington, D.C., which emphasized self-sufficiency and vocational training for African American women. She championed the "Three B's" of her educational philosophy: Bible, bath, and broom, advocating for spiritual, personal, and professional discipline. Burroughs was also a leader in the Women's Convention Auxiliary of the National Baptist Convention, where she pushed for the inclusion of women's voices in church leadership. Her dedication to empowering Black women as agents of social change influenced both the feminist and civil rights movements, promoting a vision of racial and gender equality.

Elizabeth Piper Ensley (1847–1919)

Quote: “The ballot in the hands of a woman means power added to influence.”

Contribution: Elizabeth Piper Ensley was a suffragist and civil rights activist who played a pivotal role in securing women’s suffrage in Colorado in 1893, making it one of the first states to grant women the vote. As a Black woman operating in the predominantly white suffrage movement, Ensley worked to bridge racial and class divides, emphasizing the importance of political power for marginalized groups. She was an active member of the Colorado Non-Partisan Equal Suffrage Association and focused on voter education to ensure that women, especially women of color, could fully participate in the democratic process. Ensley’s legacy highlights the importance of coalition-building in achieving systemic change.

To honor these pioneers, we must continue to amplify Black women's voices, prioritizing intersectionality, and combat systemic inequalities in race, gender, and class.

Modern black womanism and feminist activism can expand upon these little-known founders of woman's rights by continuously working on an addressing the disparities in education, healthcare, and economic opportunities for marginalized communities. Supporting Black Woman-led organizations, fostering inclusive black femme leadership, and embracing allyship will always be vital.

Additionally, when we continuously elevate their contributions in social media or multi-media art through various platforms, and academic curriculum we ensure their legacies continuously inspire future generations. By integrating their principles into feminism and advocating for collective liberation, women and feminine allies can continue their fight for justice, equity, and feminine empowerment, hand forging a society, by blood, sweat, bones and tears where all women can thrive, free from oppression.

#black femininity#womanism#womanist#intersectional feminism#intersectionality#intersectional politics#women's suffrage#suffragette#suffrage movement#suffragists#witches of color#feminist#divine feminine#black history month#black beauty#black girl magic#vintage black women#black women in history#african american history#hoodoo community#hoodoo heritage month#feminism#radical feminism#radical feminists do interact#social justice#racial justice#sexism#gender issues#toxic masculinity#patriarchy

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

Why were women of the present cut off from women of the past and how was this achieved? While we had been ready to believe the lessons of our own education and to accept that there was but a handful of women in the past who had protested against male power, that they were ‘eccentric’ at best, and more usually ‘neurotic’, ‘embittered’ and quite unrepresentative, then the absence of women's voices from history seemed understandable. But when it began to appear that there had been many women who had been saying in centuries past what we were saying in the 1970s, that they had been representative of their sex, and that they had disappeared, the problem assumed very different proportions.

For years I had not thought to challenge the received wisdom of my own history tutors who had — in the only fragment of knowledge about angry women I was ever endowed with — informed me that early in the twentieth century, a few unbalanced and foolish women had chained themselves to railings in the attempt to obtain the vote. When I learnt, however, that in 1911 there had been twenty-one regular feminist periodicals in Britain, that there was a feminist book shop, a woman's press, and a women's bank run by and for women, I could no longer accept that the reason I knew almost nothing about women of the past was because there were so few of them, and they had done so little. I began to acknowledge not only that the women's movement of the early twentieth century was bigger, stronger and more influential than I had ever suspected, but that it might not have been the only such movement. It was in this context that I began to wonder whether the disappearance of the women of the past was an accident.

Dale Spender, Women of Ideas and What Men Have Done to Them

#dale spender#first wave feminism#patriarchy in education#womens suffrage#women’s movement#patriarchy#knowledge suppression

391 notes

·

View notes

Text

In the North and South, women's standing as citizens had always been refracted through their normative adult status as wives, and by the state's equal or greater commitment to upholding marriage and the law of coverture. That law put women under their husbands' legal power in the interests of marital unity. The transformation of woman into wife made "citizenship--a public identity as a participant in public life--something close to a contradiction in terms for a married woman." The terms of female citizenship had always been set by the perceived necessities of marriage and its gender asymmetries between man and woman, husband and wife. In the North by i86o, agitation for the woman citizen's natural right of suffrage had, in conjunction with antislavery, already made serious political inroads. Increasingly women's continued exclusion had to be dignified by an argument. But nowhere in the nineteenth-century United States did any women's rights, not to mention demands for the vote, emerge outside of the context of antislavery politics. So in the South, where a proslavery agenda set the tone in politics and where politicians regularly dragooned marriage into the work of legitimizing slavery (as just another desirable form of domestic dependence suitable to the weak), women's status as citizens hardly mattered. There, politicians were habituated to thinking of women as existing at a remove from the body politic, as part of the family or the household, and not of the people and the citizens.

stephanie mccurry, confederate reckoning: power and politics in the civil war south

#i think all the time about the fact that there was no women's suffrage movement in the south#bc there was no women's suffrage movement without abolition#there was also no public school movement in the south#idk. just fascinating that the centrality of slavery to southern culture had these ripple effects in other areas#media 2k24#confederate reckoning#bookblogging

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

Women's Suffrage Memorabilia

#womens suffrage#png#pngs#aesthetic pngs#random pngs#feminism#suffrage movement#suffragists#feminist#badges#history#womens history#transparent

14 notes

·

View notes

Quote

By every fact and by every argument which man can wield in defence of his natural right to participate in government, the right of woman so to participate is equally defended and rendered unassailable.

Frederick Douglass, "Woman Suffrage Movement (1870)"

#philosophy#quotes#Frederick Douglass#Woman Suffrage Movement#women#feminism#voting#government#politics

79 notes

·

View notes

Text

#women's march#women's rights#womens suffrage#women#reproductive freedom#reproductive rights#reproductive justice#abortion rights#vote blue#vote kamala#kamala 2024#kamala harris#2024 presidential election#democrats#republicans#politics#black lives matter#donald trump#feminism#feminist movement#trump hates women

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ralph Barton, Making the Polls Attractive to the Anti-Suffragists, Puck, 30 February 1915.

Puck was the first successful humor magazine in the United States of colorful cartoons, caricatures and political satire of the issues of the day. It was founded in 1876 as a German-language publication by Joseph Keppler, an Austrian immigrant cartoonist.[1] Puck's first English-language edition was published in 1877, covering issues like New York City's Tammany Hall, presidential politics, and social issues of the late 19th century to the early 20th century.

"Puckish" means "childishly mischievous". This led Shakespeare's Puck character (from A Midsummer Night's Dream) to be recast as a charming near-naked boy and used as the title of the magazine. Puck was the first magazine to carry illustrated advertising and the first to successfully adopt full-color lithography printing for a weekly publication.

Puck was published from 1876 until 1918. (x)

#ralph barton#illustration#magazine#1915#humor#humor magazine#1915 illustration#vintage#feminism#feminism history#Anti-Suffragists#Anti-suffragism#suffrage movement#suffrage#voting rights#womens voting rights#political issue#political issues#votes for women#feminst humor#puck magazine#art#satire#political satire

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

Contemporary Suffrage,

Hey, this is my first public piece i've ever shared. This is my personal take on what is occuring overseas and how i see the position of women in these difficlt times.

-

-

-

-

-

-

#poetry#poems#prose#poetic#feminism#womens rights#liberal feminism#english literature#literature#politics#creative writing#author#writer#female writers#women's suffrage#suffragette#suffrage movement

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

#OTD in 1916 – Francis Sheehy-Skeffington was apprehended while trying to stop looting during the Easter Rising and was later murdered by the British without trial.

Francis Skeffington, writer and pacifist, was born in Bailieborough, Co Cavan on the 23 December 1878 to Joseph Bartholomew Skeffington and his wife Rose née Magorian. The family moved to Co Down shortly after his birth. He was educated by his father, a schools inspector and enrolled in University College Dublin (UCD) in 1896. While he studied at UCD he became close friends with James Joyce and…

View On WordPress

#1916 Easter Rising#3rd battalion Royal Irish Rifles#Bailieborough#Captain J.C. Bowen-Colthurst#Co. Cavan#Dublin#Execution#Francis Sheehy-Skeffington#Francis Skeffington#Glasnevin Cemetery#Glesnevin Trust#Hanna Sheehy#Hanna Sheehy-Skeffington#Pacifist#Rathmines#Women&039;s Suffrage Movement#WriterEdit "1916 – Easter Rising: Execution of Francis Sheehy-Skeffington."

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

1918 Rally Day - Women's Suffrage Postcard

@postcardtimemachine

#Fall Leaves#Rally Day#Womens Suffrage#suffrage Movement#postcard#vintage postcards#ephemera#old postcards#election

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Aoife O’Donovan — All My Friends (Yep Roc)

youtube

The title track of folk songwriter Aoife O’Donovan’s fifth solo album, All My Friends, arrives loaded with prominent guests: the Knights, the Westerlies, and the San Francisco Girls Chorus. These classical artists, some of whom are also involved in the folk movement on other outings, remain as collaborators on several of the subsequent songs. The blend of O’Donovan’s songs and the varied palette provided for the arrangements creates an expansive and well-crafted ambience. It is the first time O’Donovan has produced her own work, and, with help from co-producers Darren Schneider and Eric Jacobsen, she successfully keeps a lot of balls in the air.

The lyrics are pertinent for today, exploring the trajectory of the women’s rights movement and the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment of the Constitution, granting women suffrage. A native of Newton, Massachusetts, O’Donovan grew up a stone’s throw from many places — parks, churches, coffeehouses, and out in the streets — where for decades the rights of women were advocated for strongly. In the wake of Roe being overturned, this is a practice continuing today.

O’Donovan accentuates coming together instead of airing grievances. “All My Friends” includes the verse, “Marching on, the Tennessee dawn is lifting o’er the fields. Steady on, America, you know it’s time to heal, If you open your arms you’ll feel us, warm and ready for the change, all my friends.”

She spent the summers of her childhood studying Celtic music and dancing in Ireland. The lilting tone of her voice reflects this. On “Someone to Follow,” O’Donovan sings to a baby about the challenges that await her, knowing that her daughter will face them down and make it. Combining gritty resolve and a lullaby, with a memorable hook in the chorus and an accordion solo providing an Irish inflection to the arrangement, “Someone to Follow” is a standout.

“The Right Time” has a stripped down arrangement of acoustic guitar, bass, and drums, but when it gets to the chorus, double-tracked vocals provide soaring harmonies.

“Over the Finish Line” is a duet with Anais Mitchell, referencing the travails of democracy, going so far as “America’s bleeding,” in one of the verses.

Accompanied by piano, vocal harmonies in the chorus once again urge coming together: “If I could change a mind, whose mind? If I could make something to get us o’er the finish line, We’re living in hard times, feeling hard times, living in hard times.”

There is one cover, Bob Dylan’s “The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll,” describing the beating death of an African American woman by a white tobacco farmer in 1963, the year the song was written. The assailant got six months in jail. The Knights join O’Donovan in a rich arrangement that combines “The Battle Hymn of the Republic” with Dylan’s song, underscoring the inclusion of Black Lives Matter in O’Donovan’s meditations on America’s current challenges. It is a rousing conclusion to All My Friends, a relevant and compelling recording.

Christian Carey

#aoife o'donovan#all my friends#yep roc#christian carey#albumreview#dusted magazine#women's suffrage movement#celtic music

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

There is no adequate way to convey the contribution that Elizabeth Cady Stanton made: she talked and wrote volumes, and Alice S. Rossi (1974) has said of her that: ‘There was probably not another woman in the nineteenth century who put her tongue and pen to better use than Elizabeth Stanton’ (p. 382). Fundamental to her beliefs was the insistence that women must abandon the mentality of oppression in which they had been socialised; they must learn to value themselves, to insist on their own needs, to repudiate self-effacement and sacrifice, which they could do without jeopardising their strength of being able to provide emotional support.

That women should give up guilt was one of her tenets, that they should learn to express their justifiable anger was another. ‘She was not a woman easily threatened by new experiences’, says Rossi (1974) and among her prescriptions for a healthy womanhood was one she clearly followed herself, but which it would take many decades for medicine and psychiatry to learn. She insightfully put her finger on an important cause of hysteria and illness among the women of her day, in an 1859 letter to a Boston friend: ‘I think if women would indulge more freely in vituperation, they would enjoy ten times the health they do. It seems to me they are suffering from repression’ (Stanton and Blatch, 1922: 11, 73-74 (Rossi, 1974, p. 381)).

To Elizabeth Cady Stanton, women's anger was not only valid, and necessary, but rational: ‘I am at boiling point,’ she once wrote to Susan B. Anthony, and, ‘If I do not find some day the use of my tongue on this question I shall die of an intellectual repression, a woman's rights convulsion’ (Theodore Stanton and Harriet Stanton Blatch, 1922, vol. II, p. 41).

She began her public lecturing (and writing) career in much the same spirited manner in which she was to continue, when, upon hearing that she was preparing to go an a lecture tour, her father came to ask if this were true. She told him that it was: ‘“I hope,” he continued, “You will never do it in my lifetime, for if you do, be assured of one thing, your first lecture will be a very expensive one”’ (for he would disinherit her). She replied: ‘I intend … that it shall be a very profitable one’ (ibid, p. 81). She could not be bought by male approval, or the promise of male rewards in return for good behaviour.

At no stage did she fall into the trap of believing that woman's position was the consequence of ignorance among men and that all that was necessary was for women is to present their case, and men, instantly enlightened, would be won to women's cause. She had no delusions about male justice. She understood that men held the power and that, short of women going off on their own and starting an alternative society (never an option for Stanton although she created her own female enclave from which she drew her emotional support), men had to be confronted, and coerced into giving it up. Because her style was not conciliatory, because she did not seek to persuade men that she was respectable and worthy, because she did not try to convince them that men themselves would be better off when women were enfranchised, and that nothing would change, for women would still continue to be the home-makers, child-rearers, and domestic servants, she was often considered unacceptable not only by men, but by many women who took a more cautious approach. She insisted on delivering her speeches criticising marriage as an institution, she insisted on advocating divorce law reform (despite the fact that she was branded, and discredited as, an advocate of free love), and her outspokenness, and her outrage were often a source of embarrassment to some of the women towards the end of the nineteenth century who were trying to allay and soothe the fears of men - in the hope that, no longer frightened, they would grant women the vote.

-Dale Spender, Women of Ideas and What Men Have Done to Them

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

1914 Kewpie postcard promoting Women's Suffrage movement, print produced by Campbell Art Co. Kewpie, an original material created by Rose O'Neill

Alt text is available.

#kewpie#kewpie doll#women's suffrage movement#radblr#uncovered this treasure after a quick interaction concerning sonny angel's (vs. kewpie dolls) w/ oomf#thought it (the postcard) was a brilliant discovery o:

2 notes

·

View notes