#Winter Diet for Dairy Animals

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

सर्दी में पशुओं की देखभाल कैसे करें: दूध उत्पादन बढ़ाने और पशुओं को स्वस्थ रखने के बेहतरीन टिप्स

सर्दियों के मौसम में पशुपालन करने वाले लोगों को कई चुनौतियों का सामना करना पड़ता है। ठंड का सीधा असर न केवल पशुओं के स्वास्थ्य पर पड़ता है, बल्कि उनके दूध उत्पादन में भी गिरावट आ सकती है। ऐसे में पशुपालकों को अपने पशुओं की विशेष देखभाल करनी चाहिए। आज हम आपको बताएंगे कि सर्दी में पशुओं को ठंड से कैसे बचाएं और उनके दूध उत्पादन को कैसे बनाए रखें। पशुओं को खुले में न बांधें सर्दियों में ठंडी हवा और…

#Cow and Buffalo Milk Production Tips#Goat Farming in Winter#Livestock Health in Cold Weather#Winter Care for Livestock#Winter Diet for Dairy Animals#घरेलू उपचार

0 notes

Text

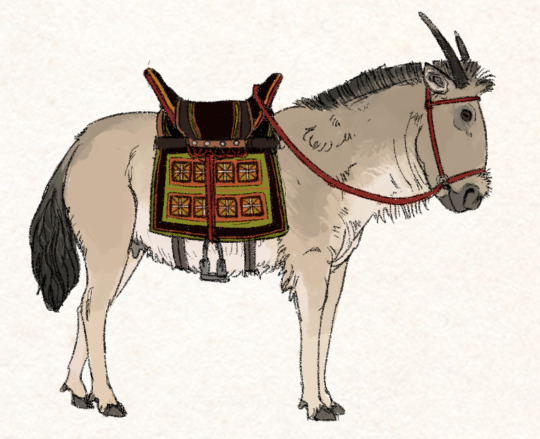

THE HIGHLAND KHAIT: AN OVERVIEW

The Highland khait, known internally as the feydhi, is a landrace breed of the Highlands of contemporary Imperial Wardin, and highly distinctive from all other native khait in the region. Their horns are notably unusual, being curved and pointed and frequently asymmetrical, which is often cited as a result of their folkloric origins as hybrids of khait and the (asymmetrically one-antlered) scimitar deer. They are very stocky and small for a riding breed, typically standing no more (and usually less) than 55 inches at the shoulder. Their coats come in a wide variety of colors and patterning, though a majority of individuals are dun or gray. Their manes are notably short and stiff, and they lack the beards common in many other khait breeds.

While notably slower than other khait, feydhi are very surefooted and have notably smooth gaits, able to move at a steady trot over difficult terrain with minimal bouncing for the rider. They are extremely strong for their size, and fully capable of carrying most adult riders and heavy packs, and pulling plows.

Their hair is longer than average but provides little insulation and they do not grow winter coats, and instead rely predominantly on fat stores to cope with winter conditions. They are easy keepers that can gain and maintain mass with very poor grazing, though most require supplements of grain to their diets to gain sufficient fat stores to survive winters in the highest settled altitudes.

Feydhi can adapt well to the hotter lowlands conditions than other Highlands livestock largely due to this lack of thick hair. Because they require no supplement to their diet to maintain condition, they are very affordable khait and an asset (along with a few other specialized lowlands breeds) during dry seasons, and see wide use throughout Imperial Wardin (particularly as pack animals along trade routes). They often survive a little too well in the lowlands, being adapted to sparse mountain pastures rather than seasonally abundant grasslands, and can be prone to obesity when allowed to graze freely.

They show a small degree of selection for milk production due to the import of dairy to the regional diet of the Highlands. Their milk has the highest fat content of the native livestock, but a notably gamey taste that is generally disfavored. It's used primarily as-is for basic sustenance and medicinal purposes- growing children and pregnant women are encouraged to drink feydhi milk to build fat stores, and mounted herders will often ride lactating mares in the winter and subsist largely upon their milk. Their meat is also the fattiest of any of the regional livestock and (unlike their milk) generally regarded as the best in taste, though their value as riding animals and more expensive upkeep prevents their consumption on any regular basis.

Rendered, chilled feydhi fat mashed with berries and eaten on bread is a seasonal delicacy eaten at midwinter feasts. It is considered an obligation of a wealthy ruling clan to slaughter some of their khait and provide the fat for this meal to their dependents, and an indication of failing wealth and authority if they cannot. A phrase translating as 'rich in cattle, poor in fat' invokes the notion of having a clan having superficial wealth (in cattle, which can largely sustain themselves on poor grazing and thus can hide a loss of material power for a period) but a heavily insecure position (unable to actually afford to lose their more high maintenance assets), and is used colloquially to describe a person or people giving hollow performances to mask lacking or lost substance.

They have some unique behavioral quirks among khait, such as a propensity to use their lower teeth in allogrooming to rake and scratch each other. This favoring of their teeth also lends more aggressive animals to biting (in addition to the far more khait-typical headbutting and kicking), a behavior that seems reserved exclusively for humans and is rarely used in intraspecies conflict. As with all bovidae, they no upper incisors and their bite can only do so much harm in most circumstances, but they can cause significant damage to the fingers of the unwary. They are also known for their tendency to consume bite-sized animals such as small birds when given the opportunity- this is not atypical of khait (or many grazing herbivores at large), but is emphasized in combination with their tendency to bite to cast them as uniquely carnivorous.

Their temperaments are regarded as notably stubborn and somewhat testy, but this is made up for with their intelligence and generally calm demeanor. Feydhi are most prized for their bravery- they do not spook easily against wild predators and can perform some functions as livestock guardians, readily chasing off small threats and known to stand their ground against even large predators, particularly hyena (the most populous and routinely threatening predator in the region).

This trait is commonly noted in folktales- one western mountain pass is said to be haunted by the ghost of an old gray mare who stood guard over her master (a noted drunk, who had fallen off her back and passed out) against a pack of hyenas for an entire night. When her rider awoke the next day, he found her dead and bloodied with her horns stuck into a hyena's side, having killed the predators but succumbed to her own wounds. He was so sorrowful that he resolved to never drink again (outside of holidays, and perhaps weddings) and buried her under stone. Travelers through this pass customarily pour out liquor and leave little offerings of grain for the animal's spirit, which is said to be seen at night from a distance, standing vigilant atop its cairn, but vanishes when approached.

The settlement cycle stories of the Hill Tribes go into extensive detail about the cattle and horses brought overseas with the migrants, but elaborate little on their khait and imply that a riding culture did not exist during the settlement period. The stories tend to describe people as walking on foot or riding their cattle, and khait riding is only mentioned in descriptions of proto-Wardi mounted nomads in the lowlands. It is likely that khait riding (rather than sole use as pack animals) was an adopted practice post-settlement, and possible that khait were not brought along with the migrants to begin with.

The actual origins of the feydhi breed are ambiguous as such. Old Ephenni folklore mentions tiny 'fairy' khait living in the Highlands that predated the arrival of the Hill Tribes, suggesting that these animals were already established as feral herds. It's highly possible that these herds were are a relic of the cairn-building civilization that existed in the Highlands prior to recorded history and had already long vanished (likely in a combination of plague and dispersal) prior to the settlement. The stories of feydhi being hybrids between foreign khait and native deer is also suggestive of such an origin, with wild deer as ancestors being a mythologized twist on feral khait.

Feydhi do not have the same status of cattle or horses as fundamental to subsistence, with much of their use being in utility as pack animals and transport over difficult terrain. However, they play very significant roles in the livestock raiding aspects of warrior culture, where they are used for quick exits and to help drive cattle and horses. Their roles in other aspects of warrior culture are more varied between tribes- some use them near-exclusively for raids, while others rely on them for open combat. Khait warrior culture is most central in the western Urbinnas tribes, who each consider themselves to be the most skilled riders and uniquely specialize towards mounted archery. The Urbinnas tribes have a long history of interaction with the lowlands Ephenni Wardi (alternating cycles of conflict and trade, and a half century of allyship against Imperial Burri occupiers). Both groups have a strong history of mounted warrior culture, and each claims to have introduced mounted archery to the other.

Khait also play roles in regional combat sports, which include mock battles and raids, races, archery, and most famously khait wrestling. The latter involves two mounted riders attempting to wrestle one another off their khait, gain control of their opponent's mount, and then successfully lead both animals out of the ring without their opponent re-mounting. This sport requires very calm, collected animals that will not panic while being fought over, and the measured temperament of the feydhi is well suited.

#The Wardi Highlands are not analogous to Iceland At All but having just spent a week surrounded by an awesome small cold#adapted horse landrace breed it was time to like actually flesh these guys out#creatures#hill tribes

147 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Nerge: Hunting in the Mongol Empire

The peoples of the Mongol Empire (1206-1368 CE) were nomadic, and they relied on hunting wild game as a valuable source of protein. The Asian steppe is a desolate, windy, and often bitterly cold environment, but for those Mongols with sufficient skills at riding and simultaneously using a bow, there were wild animals to be caught to supplement their largely dairy-based diet. Over time, hunting and falconry became important cultural activities and great hunts were organised whenever there were major clan gatherings and important celebrations. These hunts involved all of the tribe mobilising across vast areas of steppe to corner game into a specific area, a technique known as the nerge. The skills and strategies used during the nerge were often repeated with great success by Mongol cavalry on the battlefield across Asia and in Eastern Europe.

Hunted Animals

The Mongols, like other nomadic peoples of the Asian steppe, relied on milk from their livestock for food and drink, making cheese, yoghurt, dried curds and fermented drinks. The animals they herded - sheep, goats, oxen, camels and yaks - were generally too precious as a regular source of wool and milk to kill for meat and so protein was acquired through hunting, essentially any wild animal that moved. Animals hunted in the medieval period included hares, deer, antelopes, wild boars, wild oxen, marmots, wolves, foxes, rabbits, wild asses, Siberian tigers, lions, and many wild birds, including swans and cranes (using snares and falconry). Meat was especially in demand when great feasts were held to celebrate tribal occasions and political events such as the election of a new khan or Mongol ruler.

A basic division of labour was that women did the cooking and men did the hunting. Meat was typically boiled and more rarely roasted and then added to soups and stews. Dried meat (si'usun) was an especially useful staple for travellers and roaming Mongol warriors. In the harsh steppe environment, nothing was wasted and even the marrow of animal bones was eaten with the leftovers then boiled in a broth to which curd or millet was added. Animal sinews were used in tools and fat was used to waterproof items like tents and saddles.

The Mongols considered eating certain parts of those wild animals which were thought to have potent spirits such as wolves and even marmots a help with certain ailments. Bear paws, for example, were thought to help increase one's resistance to cold temperatures. Such concoctions as powdered tiger bone dissolved in liquor, which is attributed all sorts of benefits for the body, is still a popular medicinal drink today in parts of East Asia.

Besides food and medicine, game animals were also a source of material for clothing. A bit of wolf or snow leopard fur trim to an ordinary robe indicated the wearer was a member of the tribal elite. Fur-lined jackets, trousers, and boots were a welcome insulator against the bitter steppe winters, too.

Continue reading...

102 notes

·

View notes

Text

I'm watching the new season of Beastars. This season the school is undergoing segregation and society is more divided. As someone who studied ecology and loves reading up the natural history of animals. And likes to dabble here and there among the nutritional science of things. I have a major thorn about the series I have to address. Even if its a work of fiction, the knowledge I have is making me pause episodes far too many times.

And the issue is....the separation of Herbivores and Carnivores, the drug KINES and their reaction to it.

Most animals, even if classified as Herbivores can become omnivorous if conditions and situations arise. I've seen squirrels eat birds. I've seen deer on a nice warm spring day snatch up a goslings without hesitation, I've seen rabbits nibbling on deer antlers.

Many Herbivores especially during the winter and early spring will eat what is available, that includes bones, antler sheds, and sometimes even carrion, if there's nothing else. So how can you have a dedicated herbivore and carnivore? Why are cranes, chickens and peacocks among the herbivore group? HAVE YOU SEEN A CHICKEN HUNT AND SWALLOW A MOUSE??? Cranes and herons eat other aquatic animals.

The series integrates insects, milk and eggs as part of the diet. The majority of carnivores, Omnivores, Insectivores and Herbivores partake in these things.

Insects, milk, eggs, all come from a living being, and are animal products, or in the case of insects, are still considered animal protein. Sharing similar nutrients, minerals, proteins, fats and amino acids.

Therefore...The portrayal of the drug KINES is a bit flawed as that most of the inhabitants of the series have consumed animal products or animal proteins. Louis brings a chemical analysis and points out actin and myosin, both proteins present in muscle and cell movement, this includes insects. Louis says the report comes in as "trace" amounts, which means not alot. But remember...society regularly consumes dairy, eggs and insects.

Deshico makes a mention about there are GST's, during his demonstration of KINES between a carnivores who does not eat fresh meat regularly vs a carnivore who does. GST's is whole family of enzymes with a multitude of functions, some involved in digestion and detoxification in the liver. They are present in all tissues and organs, this includes insects. And if we use humans as an example....even life time vegetarians and vegans still retain the ability to digest meat, because some of the protease enzymes that are present during digestion are generalists, like pepsin, meaning they could break down the kale you ate AND the chicken you ate. Even wilder....there are some plants that can digest meats. Ever wonder why fresh pineapple makes your mouth tingle? That's bromelain in the juice, it breaks down protein, its digesting your tongue! So that's that's it. I don't have enough biochemical knowledge to tell you what would make KINES more believable for me. But as it stands, I would expect more species becoming MORE feral/addicted to this drink if regular consumption of animal proteins is all it takes and this is more or less addressing a nutritional deficiency of some kind. And if so, the society in this show is just okay with having the land carnivores and omnivores to be in a perpetual state of mal-nutrition and deficiencies..

21 notes

·

View notes

Note

how strong is mongolia's spice tolerance?

...Honestly not very good LMAO. Mongolian food is nice but it's not traditionally spicy at all. The seasonings Mongols traditionally use are more simple (sometimes just salt) and Mongolian cuisine in general is a bit simpler compared to others.

Mongolia's traditional food heritage, revolves around a diet focused on meat and dairy. This diet, essential for surviving severe winters/weather conditions, emphasizes simplicity in dishes and cooking techniques. Quick preparation is key, considering the long days spent tending to animals, ensuring meals are ready without prolonged waits after exhausting outdoor work. In addition, considering the nomadic nature of the traditional Mongolian lifestyle and the climate, it's pretty hard to grow spices, hence why Mongolian cuisine is traditionally not spiceful (this doesn't mean it's bad though) but also why Mongolia is not exactly someone with a good spice tolerance.

You'd think the Yuan would have opened him up to more spices considering how the Mongols utilised the Silk Road/trade and the fact that the Yuan was essentially Mongolia ruling over China but:

1) The Mongols adamantly stuck to eating their own diet rather than Chinese, despite ruling over China

2) You know when you go to a restaurant and the "spicy" option isn't actually spicy but adjusted for people who aren't used to spice? That's probably the level of spice Mongolia ate most of the time when he tried out foreign cuisines (you probably wouldn't want to piss him off by giving him something actually pretty spicy during that era)

I think he's gotten better at spices now but still, it's not amazing. He probably needs a gallon of milk in hand whenever he eats at India's place LOL

#hetalia#aph mongolia#hws mongolia#hetalia world stars#hetalia world series#hetalia world twinkle#aph china#hws china#Hetalia Mongolia#Hetalia China#Aph India#Hws India#Hetalia india#hetalia headcanons#Hetalia hcs#Aph Asia#Hws Asia#Hetalia Asia#Aph east Asia#Hws east Asia#Hetalia east Asia

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nickit & Thievul

Nickit (#827)

Vulpes astutes

General Information: Nickit the Fox Pokémon. They are a cunning thief who enjoy stealing from others rather than, say, bothering to go find their own food. They can move silently thanks to their soft paw pads, and their tails hide their tracks by sweeping the imprints away.

Nickit average at 2 feet (0.6 M) tall and weigh about 20 pounds (9 kg).

Habitat: Nickit are found throughout most of Europe and parts of western Asia, specifically the region between the Ural Mountains and the Pyrenees Mountain—these mountains create a natural boundary for them that separates them from the natural territory of other fox Pokémon. Their habitat extends south into the Arabian Peninsula, but there it slowly transitions into Fennekin territory.

Nickits have been introduced into Australia and are an invasive species.

Life Cycles: Nickits are born in the spring to litters of 4-6 kits, but some litters have been recorded to have as many as 13 individuals! For the first 2 weeks of their life, the baby Nickits are blind, deaf, toothless, helpless and completely dependent on their extremely protective mothers (and fathers). Should their mother die before they are independent, their father will take over providing for them—though, to be clear, their father almost certainly had been spending his time making sure their mother was being provided for, instead of fucking off to who-knows-where. At 3-4 weeks old, kits begin the gradual process of weaning by testing out new foods, and will continue to drink their mother’s milk until around 6-7 weeks of age. Kits are able to move out of their mother’s den at around 5 months old.

In theory, a Nickit can begin reproduction at level 15 or 1 year of age (whichever comes last), but social pressures from their family group keep them from reproducing until they’ve evolved into Thievul.

Behavior: Nickits are cunning and clever creatures. They are also social animals that work together, often in sibling groups. They love stealing their food and are terrible hunters, and they bare a rivalry with Purrloins (who are exotic to the Old World). Despite beliefs to the contrary, Nickits are deeply loyal to their family groups.

Diet: Carnivore-leaning omnivores. They’ll eat most things but prefer animal-based substances like meat, dairy, and eggs.

Conservation: Threatened

Relationship with Humans: Nickits are notorious thieves in European folklore. They are seen as sly, cunning, clever, and untrustworthy, and have such a bad reputation that even the Pokémon League Foundation generally doesn’t recommend them as starter Pokémon because of the “poor influence” they would have on a new trainer.

They have adapted well to urban environments and Nickits can be found in just about any European town or city, whether you see them or not.

Classification: Nickits are in the same genus as the Vulpix line, Vulpes. Their species epithet, “astutes” refers to their cleverness.

Thievul (#828)

Vulpes trichopulchellus

General Information: Thievul, the evolved form of Nickit, and London’s infamous canid capers! These clever fiends are excellent thieves who will secretly mark their target with a scent marker, which they’ll later track down to their home and steal their food and eggs when they’re off-guard. Breeders beware!

Thievuls average at 3’11 feet (1.2 M) tall and weigh about 44 pounds (20 kg).

Habitat: Thievuls are native to the region of Europe and Asia between the Pyrenees and Ural Mountains, with periodic family groups that make their way closer to the Arabian Peninsula. They are quite prolific in urban environments.

Life Cycles: Thievuls may live with their birth pack for several years until they’re ready to take on their own territory. Siblings will often venture out together, find mates together, and birth their own family units together. When it is finally time to mate, courtship begins in the middle of winter and will last for about 3 weeks. From there, the female will gestate her eggs for about 2 months. Seasonal monogamy is generally accepted. Both parents will do their part in raising their kits, and in fact the entire pack will share in the raising of kits in their own way, such as how the “subordinate” females and the fathers will help feed the mothers who have kitted.

Thievuls do not hunt prey but do steal eggs to an obnoxious and notorious degree. In this world, farmers don’t hate Thievuls (foxes) for stealing chickens, they hate them for stealing the eggs of their livestock Pokémon. They are not terribly picky about their eggs, but do tend to avoid ones that require traversing extreme temperatures or other extreme obstacles—there are easier meals, after all. In their natural habitats, their egg stealing is widely known and native species are used to their wily ways and are expecting it, but in places like Australia where they were introduced to keep Bunnelby populations at bay by stealing their eggs in their burrows (the author of this report does not claim that European Colonizers are intelligent), this backfired tremendously and now Thievuls are running rampant across the continent stealing eggs and food while the native inhabitants struggle to prepare themselves for this new threat.

Behavior: Thievuls live in family units with loose hierarchies where dominant members of the group (often the parents) will mate while the subordinate members (often the children of past litters) will not. They den inside hills, slopes, tree roots, gutters, clefts, or even abandoned human dwellings.

They experience a great hatred of Boltunds (because Boltunds have historically been used to hunt them) and are arch-rivals with Liepards.

Diet: Carnivore-leaning omnivores. They can eat most things but prefer meat, eggs, and dairy products. Especially eggs, in fact they love eggs. Thievuls are superb egg thieves and are the primary egg thieves wherever they live, which is the biggest reason why they are invasive in Australia.

Conservation: Threatened (but Invasive in Australia)

Relationship with Humans: Thievuls are hated by much of the ecosystem, from humans to Pokémon alike. Humans hate them for the fact that they steal their food, and Pokémon hate them because Thievuls steal their eggs. Boltunds have been used for centuries to hunt down and kill Thievuls for sport, and a natural mutual hatred for each other have emerged.

In media, if someone needs to be a burglar, Thievuls (and Liepards) are the two go-to stereotypical burglar Pokémon.

Classification: Thievul’s species epithet, “trichopulchellus” means “fancy hair,” in reference to its moustache.

Evolution: Thievul evolves from Nickit at level 18.

~~~~~~~~

Hey guess what, if you like my stuff, this is my website where you can find other Pokémon I've written on and more information about the game that I’m slowly making! Check it out! I write books sometimes too.

#nickit#thievul#pokemon#pokemon biology#pokemon biology irl#pokemon tabletop#tabletop#pokemon irl#pokemon biology irl tabletop#tabletop homebrew#ttrpg#homebrew#pkmn#pokemon sword and shield#pokemon swsh#swsh#pokemon gen 8#gen 8 pokemon#galar#galar pokemon#galar pokedex

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

What is a Plant-Based diet?

This blog is about my journey and experiences cooking and eating healthy food with my family.

I’m a passionate cook and I aim to take the mystery out of what a plant based diet means. If you are interested I'd like to show you how to do it too.

The Plant Based diet is made up of a variety of grains such as oats, barley, quinoa, bulgar wheat, buckwheat, and rice, legumes such as peas, beans, and lentils, vegetables, fruit, dairy-free versions of milk, cheese and yoghurt, pasta, bread, nuts, seeds and much more.

I would also like to mention the benefits I have experienced are a noticeable increase in energy levels and all round well-being since committing to eating this way. *Please enter a little disclaimer here about how I can't promise everyone will feel this way.

We simply need to know what to look out for and where, plan ahead and ensure we are reaching our nutritional needs. This goes for any food based plan we follow. It doesn't take long to source all your favourite ingredients based on price, availability and personal choices. We are creatures of habit and usually settle on a series of dishes we enjoy that may vary throughout the seasons. I think of soups and stews more in the winter and lighter meals in the summer. It would be interesting for you to take a look in your kitchen cupboards and fridge right now to see what kind of variety you are currently eating.

The foods that I choose not to consume are ones that are made from or contain animal products. The "why" is not very important here as I feel everyone will have their own personal reasons for not consuming animal products. I focus on what we can eat instead of what we cannot.

#family#plant based#vegan#veganism#what vegans eat#healthy#energy#variety#meals#dairy free#lactose free#choice#understanding#plans

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Northern Europe had a shit ton of dairy products — and we know this because those regions have lower levels of lactose intolerance! In the early middle ages like 97% of your diet would be grains, but they were making a variety of dishes using things like barley and millet. Bread was super fucking important and probably would have been eaten every day, and if they could afford it, they'd add spices like cinnamon to their porridges. Medieval people fucking LOVED spices that we put in pumpkin pie nowadays. Allspice, stuff like that. Sugar wasn't really widely available until the 1600s, but salt was a pretty common seasoning.

Meat was usually a fall thing. They'd slaughter animals they couldn't afford to feed through the winter. Coastal places had fish year round though, but most people probably had meat five or six times a year—if not less.

tfw you see some stupid post that paints medieval peasants eating just plain grey porridge and acting as if cheese, butter or meat was too exotic or expensive for them, and have to use all your inner strength to not just reblog it with an angry rant and throwing hands with people. so i will just post the angry rant here

no, medieval people did not only eat grey porridge with no herbs or spices, they had a great variety of vegetables we dont even have anymore, grains and dairy products, not to mention fruits and meats, all seasonal and changing with the time of the year. no, medieval food was not just tasteless, maybe this will surprise some of you but you can make tasty food without excessive spice use, and can use a variety of good tasting herbs. if you'd ever tried to cook some medieval recipes you would know that. medieval people needed a lot of energy for their work, if they would only eat fucking porridge all of the time they would get scurvy and die before they could even built a civilisation. they had something called 'pottage' which was called that because it was cooked in one pot. you could leave the pot on the fire and go about your day, doing stuff and come back to a cooked meal. they put in what was available that time of the year, together with grains, peas, herbs, meat etc etc. again, if you would try to make it, like i have with my reenactment friends, it can actually be really good and diverse.

dont confuse medieval peasants with poor people in victorian england. dont think that TV shows what it was really like. dont think that dirty grey dressed people covered in filth were how the people looked like.

they made use of everything. too poor to buy proper meat? buy a sheeps head and cook it. they ate nettle and other plants we consider weeds now. they foraged and made use of what they found. hell, there are medieval cook books!

most rural people had animals, they had chickens (eggs), goats (milk and dairy), cows (milk and dairy), sheep (milk and dairy) and pigs (meat machine), and after butchering they used ALL THE PARTS of the animal. you know how much meat you can get out of a pig, even the smaller medieval breeds? the answer is a lot

if you had the space you always had a vegetable garden. there are ways to make sure you have something growing there every time of the year. as i said they had a variety of vegetables (edit: yes onions are vegetables, for those who dont seem to know) we dont have anymore due to how farming evolved. you smoked pork in the chimney, stored apples in the dry places in your house, had a grain chest. people could go to the market to buy fish and meat, both fresh and dried/smoked. they had ale, beer and wine, that was not a luxury that was a staple part of their diet.

this post ended once again up being longer than i planned, but please for the love of the gods, just actually educate yourself on this stuff and dont just say stupid wrong shit, takk

27K notes

·

View notes

Text

farm-animals-for-sale

you're looking for farm animals for sale, whether you're starting a homestead, expanding your farm, or simply interested in adding new animals to your farm, there are many options available. From traditional livestock like cows, pigs, and chickens, to more specialized animals such as alpacas or goats, farm animals can be a rewarding addition to your property. Websites like animalssale.com can be helpful for browsing available animals, but it’s important to consider the specific care and requirements of each species before purchasing.

Here’s a guide to some common farm animals for sale and important factors to consider when buying them.

1. Cattle (Cows and Bulls)

Cattle are one of the most essential farm animals, providing dairy, meat, and even leather. There are various breeds of cattle, each suited to different purposes. Dairy cows, beef cattle, and dual-purpose breeds (suitable for both meat and milk) are common choices.

Popular Cattle Breeds:

Holstein: Primarily a dairy breed known for high milk production.

Angus: Popular for beef production, known for tender, high-quality meat.

Hereford: Another beef breed known for its docile temperament and efficient growth.

Care Considerations:

Space: Cattle need plenty of space to roam and graze. A few acres of pasture are generally required for grazing.

Feeding: Cattle typically graze on grass but may require supplemental feeding, especially during winter months.

Shelter: While cattle are hardy animals, they need some form of shelter or shade to protect them from extreme weather conditions.

2. Pigs

Pigs are commonly raised for meat production (pork) and are known for their intelligence and quick growth. They can be raised on small farms or large commercial operations.

Popular Pig Breeds:

Yorkshire: Known for its fast growth and ability to adapt to various climates.

Berkshire: Valued for its marbled meat, which produces a tender and flavorful pork.

Landrace: Another popular breed for pork production due to its high fertility and good meat yield.

Care Considerations:

Housing: Pigs need secure housing to protect them from predators and the elements. Pens or barns are commonly used.

Feeding: Pigs are omnivores and require a balanced diet that can include grains, vegetables, and protein sources.

Space: Pigs need plenty of room to root around and exercise. If raised on pasture, they can be rotated to different areas to avoid overgrazing.

3. Chickens

Chickens are one of the most popular farm animals, primarily raised for their eggs and meat. They are relatively easy to care for and require minimal space, making them a great option for both small farms and large-scale operations.

Popular Chicken Breeds:

Rhode Island Red: Known for high egg production and hardiness.

Leghorn: A prolific egg layer, especially in commercial egg farms.

Cornish: Primarily raised for meat, known for rapid growth and large size.

Care Considerations:

Housing: Chickens need a secure coop to protect them from predators and weather conditions. It should also provide nesting boxes for egg-laying.

Diet: Chickens eat grains, seeds, and insects. They also benefit from supplemental calcium for strong eggshells.

Space: Chickens need room to roam, scratch, and forage. Free-range chickens are often healthier and happier but still require a secure coop at night.

4. Goats

Goats are versatile farm animals that can be raised for milk, meat, or fiber. They are social animals and are often kept in pairs or small groups.

Popular Goat Breeds:

Nubian: A popular milk breed with high butterfat content in its milk.

Boer: Primarily raised for meat production due to their rapid growth and large size.

Angora: Raised for their fiber, which is used to produce mohair.

Care Considerations:

Housing: Goats need a shelter that protects them from rain, wind, and extreme temperatures. They should also have access to secure fencing to prevent them from escaping.

Feeding: Goats are herbivores and need access to fresh forage like grass and hay. They can also eat grains and need fresh water at all times.

Space: Goats need plenty of space to graze and exercise. They are known to be escape artists, so fencing must be secure.

5. Sheep

Sheep are raised for their wool, meat (lamb or mutton), and milk. They are hardy animals and are well-suited for grazing on pastures.

Popular Sheep Breeds:

Merino: Known for high-quality wool and hardiness.

Suffolk: A meat breed known for its large size and good growth rate.

Dorset: Known for their excellent lambing ability and quality meat.

Care Considerations:

Housing: Sheep need a secure shelter to protect them from predators and weather conditions. They can be kept in barns or open sheds.

Feeding: Sheep are herbivores and primarily graze on grass, but they may need supplemental hay during the winter months.

Fencing: Sheep require strong fencing, as they can be prone to escaping or wandering off.

6. Horses

Horses are often kept for riding, work, and companionship. They are also used for livestock management, racing, and other activities.

Popular Horse Breeds:

Arabian: Known for their endurance and agility, often used for long-distance riding.

Thoroughbred: Popular in racing and equestrian sports.

Clydesdale: A draft breed, known for its large size and strength, often used for farm work.

Care Considerations:

Space: Horses need a lot of space to roam and graze. A few acres of pasture are generally required for grazing and exercise.

Diet: Horses primarily eat grass and hay, but they may need supplemental grains and minerals, especially if they are being worked or bred.

Shelter: Horses require a shelter to protect them from harsh weather conditions, but they do well outside in temperate climates.

7. Alpacas

Alpacas are primarily raised for their soft fleece, which is used to make high-quality textiles. They are gentle and easy to handle, making them popular for small farms or hobby farms.

Care Considerations:

Housing: Alpacas need a secure shelter from extreme weather conditions and enough space to roam and graze.

Diet: Alpacas are herbivores and graze on grass and hay. They may also need supplemental minerals and vitamins.

Social Animals: Alpacas are social creatures and should not be kept alone. They do best in small herds.

8. Llamas

Llamas are larger than alpacas and are often kept as pack animals or for their wool. They are intelligent and can be trained to carry loads, making them useful for farming or hiking.

Care Considerations:

Housing: Llamas require a dry, clean shelter and plenty of space to roam. They are hardy animals but should be protected from extreme cold and wet conditions.

Diet: Llamas are herbivores and primarily graze on grass and hay.

Social Animals: Like alpacas, llamas are social and should be kept with other llamas or farm animals.

9. Rabbits

Rabbits are often raised for meat, fiber (such as Angora wool), or as pets. They are easy to care for and do not require much space, making them an excellent option for smaller farms or homesteads.

Care Considerations:

Housing: Rabbits require a secure hutch or cage with plenty of room to hop around. They also need access to fresh bedding and a safe, dry area.

Diet: Rabbits are herbivores and primarily eat hay, fresh vegetables, and a small amount of fruit.

Space: Rabbits should be allowed to exercise outside their cage regularly to stay healthy.

Things to Consider Before Purchasing Farm Animals:

Space: Ensure that you have enough space for the animals you plan to purchase. Many farm animals require large areas to roam and graze.

Legal Restrictions: Some animals may require special permits or have local regulations. Make sure to check with local authorities about any restrictions or permits needed to keep farm animals.

Time and Commitment: Farm animals require daily care, feeding, and attention. Consider the time and effort needed to care for them before making a purchase.

Breeders and Sellers: When purchasing farm animals, ensure you are buying from a reputable breeder or seller. Look for breeders who prioritize animal welfare and health.

Vet Care: Have access to a vet who specializes in livestock care. Regular check-ups, vaccinations, and health monitoring are essential for the well-being of your animals.

Conclusion:Farm animals for sale can be a rewarding addition to your homestead or farm, whether you're looking for livestock to produce meat, milk, or wool, or simply for companionship and fun. From cattle and pigs to chickens, goats, and alpacas, there are a wide variety of animals available for sale. By considering your available space, time, and resources, you can ensure that you choose the right farm animals for your needs and provide them with a healthy, happy life. Always research the care requirements for each species before purchasing and consider adopting from a rescue or reputable breeder to ensure the health and well-being of the animals

0 notes

Text

farm-animals-for-sale

If you're looking for farm animals for sale, whether you're starting a homestead, expanding your farm, or simply interested in adding new animals to your farm, there are many options available. From traditional livestock like cows, pigs, and chickens, to more specialized animals such as alpacas or goats, farm animals can be a rewarding addition to your property. Websites like animalssale.com can be helpful for browsing available animals, but it’s important to consider the specific care and requirements of each species before purchasing.

Here’s a guide to some common farm animals for sale and important factors to consider when buying them.

1. Cattle (Cows and Bulls)

Cattle are one of the most essential farm animals, providing dairy, meat, and even leather. There are various breeds of cattle, each suited to different purposes. Dairy cows, beef cattle, and dual-purpose breeds (suitable for both meat and milk) are common choices.

Popular Cattle Breeds:

Holstein: Primarily a dairy breed known for high milk production.

Angus: Popular for beef production, known for tender, high-quality meat.

Hereford: Another beef breed known for its docile temperament and efficient growth.

Care Considerations:

Space: Cattle need plenty of space to roam and graze. A few acres of pasture are generally required for grazing.

Feeding: Cattle typically graze on grass but may require supplemental feeding, especially during winter months.

Shelter: While cattle are hardy animals, they need some form of shelter or shade to protect them from extreme weather conditions.

2. Pigs

Pigs are commonly raised for meat production (pork) and are known for their intelligence and quick growth. They can be raised on small farms or large commercial operations.

Popular Pig Breeds:

Yorkshire: Known for its fast growth and ability to adapt to various climates.

Berkshire: Valued for its marbled meat, which produces a tender and flavorful pork.

Landrace: Another popular breed for pork production due to its high fertility and good meat yield.

Care Considerations:

Housing: Pigs need secure housing to protect them from predators and the elements. Pens or barns are commonly used.

Feeding: Pigs are omnivores and require a balanced diet that can include grains, vegetables, and protein sources.

Space: Pigs need plenty of room to root around and exercise. If raised on pasture, they can be rotated to different areas to avoid overgrazing.

3. Chickens

Chickens are one of the most popular farm animals, primarily raised for their eggs and meat. They are relatively easy to care for and require minimal space, making them a great option for both small farms and large-scale operations.

Popular Chicken Breeds:

Rhode Island Red: Known for high egg production and hardiness.

Leghorn: A prolific egg layer, especially in commercial egg farms.

Cornish: Primarily raised for meat, known for rapid growth and large size.

Care Considerations:

Housing: Chickens need a secure coop to protect them from predators and weather conditions. It should also provide nesting boxes for egg-laying.

Diet: Chickens eat grains, seeds, and insects. They also benefit from supplemental calcium for strong eggshells.

Space: Chickens need room to roam, scratch, and forage. Free-range chickens are often healthier and happier but still require a secure coop at night.

4. Goats

Goats are versatile farm animals that can be raised for milk, meat, or fiber. They are social animals and are often kept in pairs or small groups.

Popular Goat Breeds:

Nubian: A popular milk breed with high butterfat content in its milk.

Boer: Primarily raised for meat production due to their rapid growth and large size.

Angora: Raised for their fiber, which is used to produce mohair.

Care Considerations:

Housing: Goats need a shelter that protects them from rain, wind, and extreme temperatures. They should also have access to secure fencing to prevent them from escaping.

Feeding: Goats are herbivores and need access to fresh forage like grass and hay. They can also eat grains and need fresh water at all times.

Space: Goats need plenty of space to graze and exercise. They are known to be escape artists, so fencing must be secure.

5. Sheep

Sheep are raised for their wool, meat (lamb or mutton), and milk. They are hardy animals and are well-suited for grazing on pastures.

Popular Sheep Breeds:

Merino: Known for high-quality wool and hardiness.

Suffolk: A meat breed known for its large size and good growth rate.

Dorset: Known for their excellent lambing ability and quality meat.

Care Considerations:

Housing: Sheep need a secure shelter to protect them from predators and weather conditions. They can be kept in barns or open sheds.

Feeding: Sheep are herbivores and primarily graze on grass, but they may need supplemental hay during the winter months.

Fencing: Sheep require strong fencing, as they can be prone to escaping or wandering off.

6. Horses

Horses are often kept for riding, work, and companionship. They are also used for livestock management, racing, and other activities.

Popular Horse Breeds:

Arabian: Known for their endurance and agility, often used for long-distance riding.

Thoroughbred: Popular in racing and equestrian sports.

Clydesdale: A draft breed, known for its large size and strength, often used for farm work.

Care Considerations:

Space: Horses need a lot of space to roam and graze. A few acres of pasture are generally required for grazing and exercise.

Diet: Horses primarily eat grass and hay, but they may need supplemental grains and minerals, especially if they are being worked or bred.

Shelter: Horses require a shelter to protect them from harsh weather conditions, but they do well outside in temperate climates.

7. Alpacas

Alpacas are primarily raised for their soft fleece, which is used to make high-quality textiles. They are gentle and easy to handle, making them popular for small farms or hobby farms.

Care Considerations:

Housing: Alpacas need a secure shelter from extreme weather conditions and enough space to roam and graze.

Diet: Alpacas are herbivores and graze on grass and hay. They may also need supplemental minerals and vitamins.

Social Animals: Alpacas are social creatures and should not be kept alone. They do best in small herds.

8. Llamas

Llamas are larger than alpacas and are often kept as pack animals or for their wool. They are intelligent and can be trained to carry loads, making them useful for farming or hiking.

Care Considerations:

Housing: Llamas require a dry, clean shelter and plenty of space to roam. They are hardy animals but should be protected from extreme cold and wet conditions.

Diet: Llamas are herbivores and primarily graze on grass and hay.

Social Animals: Like alpacas, llamas are social and should be kept with other llamas or farm animals.

9. Rabbits

Rabbits are often raised for meat, fiber (such as Angora wool), or as pets. They are easy to care for and do not require much space, making them an excellent option for smaller farms or homesteads.

Care Considerations:

Housing: Rabbits require a secure hutch or cage with plenty of room to hop around. They also need access to fresh bedding and a safe, dry area.

Diet: Rabbits are herbivores and primarily eat hay, fresh vegetables, and a small amount of fruit.

Space: Rabbits should be allowed to exercise outside their cage regularly to stay healthy.

Things to Consider Before Purchasing Farm Animals:

Space: Ensure that you have enough space for the animals you plan to purchase. Many farm animals require large areas to roam and graze.

Legal Restrictions: Some animals may require special permits or have local regulations. Make sure to check with local authorities about any restrictions or permits needed to keep farm animals.

Time and Commitment: Farm animals require daily care, feeding, and attention. Consider the time and effort needed to care for them before making a purchase.

Breeders and Sellers: When purchasing farm animals, ensure you are buying from a reputable breeder or seller. Look for breeders who prioritize animal welfare and health.

Vet Care: Have access to a vet who specializes in livestock care. Regular check-ups, vaccinations, and health monitoring are essential for the well-being of your animals.

Conclusion:

Farm animals for sale can be a rewarding addition to your homestead or farm, whether you're looking for livestock to produce meat, milk, or wool, or simply for companionship and fun. From cattle and pigs to chickens, goats, and alpacas, there are a wide variety of animals available for sale. By considering your available space, time, and resources, you can ensure that you choose the right farm animals for your needs and provide them with a healthy, happy life. Always research the care requirements for each species before purchasing and consider adopting from a rescue or reputable breeder to ensure the health and well-being of the animals.

0 notes

Text

Milk Production: Feed Formula for Buffaloes Producing 12 Liters of Milk Daily

Overview: The Value of Appropriate Nutrition for Milk Production Buffaloes must be properly fed in order to fulfill their high energy and nutritional needs, as they produce 12 liters of milk per day. A balanced diet not only increases milk production but also protects the animal's general health.

Recognizing High-Milk-Yield Buffaloes' Nutritional Needs High-yielding buffaloes need a well balanced diet that contains vitamins, minerals, protein, and energy. The ideal mixture preserves the animal's physical health and promotes lactation.

Essential Nutrients for a High Milk Production Needs for Energy For high-yield buffaloes to produce milk, their diets must be high in energy. The main sources of energy are carbohydrates found in grains and forages.

Protein Requirements Proteins are essential for the production of milk. High crude protein diets, such oil cakes and lentils, are crucial.

Minerals and vitamins Vitamins A and D, calcium, and phosphorus are essential for healthy bones, reproduction, and productive milk supply.

Important Feed Ingredients for 12-Liter Milk Yield Roughage Verdant Fodder Important nutrients and fiber are provided by green fodder such as hybrid napier, berseem, or maize. It maintains the health of the buffalo's digestive tract.

Dry Feeding Incorporate dry feed such as rice or wheat straw. Green feed is supplemented with dry roughages, which serve as a filler.

Focuses on Grain Easily digested energy is provided by grains such as wheat, barley, and maize. Maintaining high milk output requires them.

Groundnut cake and cottonseed cake are examples of oil cakes that are strong in protein and very good for nursing buffaloes.

Mineral Blends Mix in mineral mixes made especially for dairy cows. These blends promote both general health and lactation.

Needs for Water A buffalo's daily water needs range from 50 to 80 liters. For the formation of milk, proper hydration is essential.

Feeding Guidelines for High-Yield Buffaloes: A Daily Feed Analysis Ratio between Roughage and Concentrate The optimal roughage-to-concentrate ratio for high-yield buffaloes is 60:40. Based on the buffalo's bodily condition and milk output, make adjustments.

Suggested Quantities Green feed: 25–30 kg daily 5–7 kg of dry fodder each day Concentrates daily: 3–4 kg Mineral Blends: 50–100 grams daily Seasonal Modifications to Feed Provide extra energy-dense feeds, such as molasses or jaggery, in the winter to make up for the colder temperatures.

Supplements for Higher Production Incorporate supplements such as probiotics or bypass protein to promote milk supply and digestion.

Typical Buffalo Feeding Errors Inadequate or excessive feeding Underfeeding lowers the supply of milk, while overfeeding might result in obesity. The buffalo's needs should always guide the diet's balance.

Ignoring Water Quality Milk production and digestion are impacted by low-quality water. Assure a steady flow of pure water.

Failure to Follow Feed Storage Procedures Poor storage causes rotten or moldy feed, which is bad for the buffalo's health. Keep feed in a dry, clean location.

Advantages of a Balanced Diet Enhanced Production of Milk The quantity and quality of milk are enhanced by a well-balanced diet.

Improved Buffalo Health Immunity is increased and improved reproductive performance is guaranteed by a healthy diet.

Cost-Efficiency Profitability is increased and waste is decreased by feeding in the proper proportions.

In conclusion, High-yield buffaloes need to be fed a balanced diet of concentrates, vitamins, and roughages. Through adherence to the suggested feed formula and the correction of frequent feeding errors, farmers may maximize milk output while guaranteeing the health and well-being of their buffaloes.

0 notes

Text

A kulustaig bull, the distinctive cattle landrace of the highlands.

Kulustaig have striking differences to other native cattle found across the Imperial Wardi claimed territory. Their aurochs ancestors were domesticated in a separate event from those found south of the Inner Seaways, and the broader cattle population kulustaig derived from may have trace bison genetics. The progenitors of this landrace were brought south across the Viper seaway by the ancestors of the contemporary Hill Tribes, and were gradually shaped into the kulustaig in adaption to the high altitudes, mild but dry summers, and cool/snowy wet seasons.

These cattle are mid-sized and stocky in build with large, broad faces, most distinguished by curly manes and 'beards' and thick, V-shaped horns. Genetically undiluted kulustaig are almost ubiquitously black, white, and/or gray, though breeding with other cattle has introduced a greater variety of coloration in contemporary stocks.

They are adapted to higher altitudes, having larger hearts and a bigger lung capacity than comparable lowland breeds, and grow thick, curly winter coats that allow for superior resistance to seasonally cooler temperatures. They can maintain condition on less food and lower-nutrition grasses than the average cattle, and are excellent instinctive foragers. This particular quality makes them attractive for crossbreeding efforts with cattle stock of the dry scrublands in the south of Imperial Wardin, though most of their other traits are highly unfavorable for hot, low altitude environments, and scrub-kulustaig hybrids with idealized traits are rare (and highly sought after as studs).

These are all-purpose cattle that can adequately fulfill roles as meat, draft, and dairy animals, though the latter role has the most importance in day to day life, and they show the most selection for milk production (though are not as high-yield as pure dairy breeds). Their meat is mostly lean and somewhat gamey, as they rely more on thick winter coats than fat stores to manage cold, and the vast majority subsist entirely on wild grasses and forage.

Most kulustaig have fairly calm, gentle temperaments, and accommodate well to human handling (it is not uncommon for cows and geldings to be passively ridden by herders otherwise traveling on foot). Their herds have strong, well defined, and stable dominance hierarchy structures, which reduces actual fighting and lends to them being more easily managed by their human herders. In most traditions, the dominant female in each herd is regarded as blessed by and belonging to the agricultural goddess Od, and will not be milked or slaughtered (this untouchable status is often maintained even if the cow's rank in the hierarchy is displaced, though traditions vary).

Bulls are almost ubiquitously given personal names by their owners (the honor often belonging to a family or clan's matriarch, who is generally considered the owner of the herd and other familial assets), while other traditions vary between just the bulls and dominant cows, personal favorites, or entire herds receiving names.

These cattle are of tremendous importance to the peoples of the highlands (particularly tribes and/or individual clans living above the river valleys, who fundamentally rely upon them for subsistence). They provide much of the meat and dairy that the core diet revolves around, and are the greatest measure of wealth within the highlands. Non-native cattle can be commonly found in parts of the highlands in the contemporary (and may be bred in to impart unique qualities to established stock, such as improved milk production or fattier meat), but kulustaig are typically prized above all the rest. These cattle are often a source of great pride for individual clans, and one of few agreed upon markers of shared identity and pride for all of the collective Hill Tribes.

Cattle raiding is a near-ubiquitous practice (both as a practical resource acquisition, and a less immediately lethal method of settling larger disputes than open warfare), and most cattle will be branded with a mark identifying their owning clan as a method of dissuading theft (often futile, particularly given cattle marked as belonging to certain wealthy clans may be especially prized). Nose rings are commonly used to assist in the handling of bulls, but have secondary protective functions that lend to their common use in even the most docile of cattle. Rings are usually blessed or have spells woven into their making as a supernatural barrier against theft, or against malicious (or at least devious) mountain spirits such as tiirgranul (who take pleasure in frightening cattle (and their herders) and are known to cause stampedes) or wildfolk (who are known to sometimes steal or curse cattle when offended, or just bored).

The word kulustaig derives from the common word 'taig'/'taigr', which refers to cattle in the contemporary languages of both the Hill Tribes and Finns, and the 'kul' root (heavily antiquated and not used in contemporary speech, most commonly recognizable in the name of the kulys plant), which has connotations of hardiness/robust qualities. The name would have derived from complimentary descriptions of the animals as 'the best and most robust of cattle'.

#GET EXCITED: 9 COW PARAGRAPHS#creatures#hill tribes#Just in general an obsolete word that was something like 'kulus' was used as a modifier to describe something as THE MOST hardy/robust#The name 'kulys' for the plant would have been derived from ancestral populations just referring to it as 'the hardiest' plant#Or like it's possible that the culture hero Kulyos was named after the plant but also very possible that the word was actually#an epithet meaning 'the hardiest' which over generations and linguistic change was reinterpreted as his actual given name#The -kul in Brakul's name also comes from this root but no longer has any literal meanings of hardiness. A name with -kul in it will#at least be associated with hardy/robust Things like tough plants and cattle#I don't have a word for the local strain of barley yet but it's probably got a kul root in there somewhere (given it would be especially#noted as the hardiest of all grains)

223 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Nerge: Hunting in the Mongol Empire

The peoples of the Mongol Empire (1206-1368 CE) were nomadic, and they relied on hunting wild game as a valuable source of protein. The Asian steppe is a desolate, windy, and often bitterly cold environment, but for those Mongols with sufficient skills at riding and simultaneously using a bow, there were wild animals to be caught to supplement their largely dairy-based diet. Over time, hunting and falconry became important cultural activities and great hunts were organised whenever there were major clan gatherings and important celebrations. These hunts involved all of the tribe mobilising across vast areas of steppe to corner game into a specific area, a technique known as the nerge. The skills and strategies used during the nerge were often repeated with great success by Mongol cavalry on the battlefield across Asia and in Eastern Europe.

Hunted Animals

The Mongols, like other nomadic peoples of the Asian steppe, relied on milk from their livestock for food and drink, making cheese, yoghurt, dried curds and fermented drinks. The animals they herded - sheep, goats, oxen, camels and yaks - were generally too precious as a regular source of wool and milk to kill for meat and so protein was acquired through hunting, essentially any wild animal that moved. Animals hunted in the medieval period included hares, deer, antelopes, wild boars, wild oxen, marmots, wolves, foxes, rabbits, wild asses, Siberian tigers, lions, and many wild birds, including swans and cranes (using snares and falconry). Meat was especially in demand when great feasts were held to celebrate tribal occasions and political events such as the election of a new khan or Mongol ruler.

A basic division of labour was that women did the cooking and men did the hunting. Meat was typically boiled and more rarely roasted and then added to soups and stews. Dried meat (si'usun) was an especially useful staple for travellers and roaming Mongol warriors. In the harsh steppe environment, nothing was wasted and even the marrow of animal bones was eaten with the leftovers then boiled in a broth to which curd or millet was added. Animal sinews were used in tools and fat was used to waterproof items like tents and saddles.

The Mongols considered eating certain parts of those wild animals which were thought to have potent spirits such as wolves and even marmots a help with certain ailments. Bear paws, for example, were thought to help increase one's resistance to cold temperatures. Such concoctions as powdered tiger bone dissolved in liquor, which is attributed all sorts of benefits for the body, is still a popular medicinal drink today in parts of East Asia.

Besides food and medicine, game animals were also a source of material for clothing. A bit of wolf or snow leopard fur trim to an ordinary robe indicated the wearer was a member of the tribal elite. Fur-lined jackets, trousers, and boots were a welcome insulator against the bitter steppe winters, too.

Continue reading...

43 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Top 10 Essential Vitamins You Need in Supplement Form

Maintaining a healthy lifestyle is often linked to getting all the essential vitamins our bodies need. With today’s busy lifestyle and dietary restrictions, it’s easy to miss out on key nutrients. That’s why many people turn to vitamin supplements to ensure they meet their daily requirements.

In this blog, we’ll highlight the top vitamins you need, the benefits of these vitamin supplements, and how they support overall health. Whether you’re looking for vegan supplements, multivitamins, or specific nutritional supplements, this guide will help you choose the right ones for you.

Why Are Vitamin Supplements Important?

Even with a balanced diet, it’s possible to fall short of getting all the essential vitamins our bodies need. Factors like limited food options, dietary preferences (such as veganism), or certain health conditions can create gaps in nutrition. That’s where supplements come in handy. They help fill in the gaps, ensuring you get a sufficient intake of vitamins like Vitamin D, Vitamin B12, and more.

Benefits of Vitamin Supplements:

Boost energy levels

Support immune function

Promote bone health and muscle function

Aid in the production of red blood cells

Improve nutrient absorption

Let’s dive into the top 10 essential vitamins and why they should be a part of your daily regimen.

1. Vitamin D

Why It’s Important:

Vitamin D plays a crucial role in bone health, immune function, and mood regulation. It also helps the body absorb calcium, which is essential for maintaining strong bones.

Sources:

Sun exposure

Fatty fish

Fortified dairy products

Why You Need It in Supplement Form:

Many people don’t get enough sunlight or have dietary restrictions that limit their intake of Vitamin D. A Vitamin D supplement can be vital, especially during winter months or if you have a vegan or vegetarian diet.

2. Vitamin B12

Why It’s Important:

Vitamin B12 is essential for red blood cell production, brain function, and DNA synthesis. A deficiency can lead to anemia and neurological issues.

Sources:

Animal products (meat, dairy, eggs)

Fortified foods for vegans

Why You Need It in Supplement Form:

Since Vitamin B12 is primarily found in animal products, vegans and vegetarians should consider taking a Vitamin B12 supplement to avoid deficiency.

3. Omega-3 Fatty Acids (DHA and EPA)

Why It’s Important:

Omega-3 fatty acids are crucial for brain health, reducing inflammation, and supporting heart health.

Sources:

Fatty fish (salmon, mackerel)

Algae-based supplements (for vegans)

Why You Need It in Supplement Form:

If you don’t consume fish regularly, consider taking an Omega-3 supplement. Vegans can opt for algal oil supplements, which are a plant-based source of DHA and EPA.

4. Calcium

Why It’s Important:

Calcium is critical for maintaining strong bones, and healthy teeth, and ensuring proper muscle function.

Sources:

Dairy products

Fortified plant milks

Leafy green vegetables

Why You Need It in Supplement Form:

If you’re not consuming enough dairy or calcium-rich foods, a calcium supplement is recommended to support bone health and prevent osteoporosis.

5. Iron

Why It’s Important:

Iron is vital for producing hemoglobin, which carries oxygen in the blood. It helps prevent anemia, fatigue, and weakness.

Sources:

Red meat (heme iron)

Lentils, beans, spinach (non-heme iron)

Why You Need It in Supplement Form:

Vegetarians and vegans may need to supplement with iron as plant-based iron (non-heme) is harder for the body to absorb. Pair it with Vitamin C to enhance nutrient absorption.

6. Zinc

Why It’s Important:

Zinc supports immune function, helps in wound healing, and is involved in DNA synthesis and cell division.

Sources:

Meat and seafood

Legumes and nuts

Why You Need It in Supplement Form:

Vegans and vegetarians might not get enough zinc from plant sources. A zinc supplement ensures you meet your daily requirements.

7. Iodine

Why It’s Important:

Iodine is critical for thyroid function and regulating metabolism.

Sources:

Iodized salt

Seaweed

Why You Need It in Supplement Form:

If you avoid iodized salt or dairy, an iodine supplement can help maintain a healthy thyroid.

8. Vitamin K2

Why It’s Important:

Vitamin K2 is essential for bone health and helps prevent heart disease by directing calcium to the bones instead of the arteries.

Sources:

Fermented foods

Animal products

Why You Need It in Supplement Form:

Vegans can take Vitamin K2 supplements derived from natto (fermented soybeans).

9. Multivitamins

Why You Need It:

Sometimes, it’s easier to take a multivitamin supplement that includes a combination of essential vitamins. This is especially helpful for those who may not get all their vitamins from food sources.

Benefits:

Ensures a balanced intake of multiple vitamins

Convenient and easy to use

10. Vitamin C

Why It’s Important:

Vitamin C is a powerful antioxidant that supports the immune system and enhances the absorption of iron from plant-based sources.

Sources:

Citrus fruits

Bell peppers, broccoli

Why You Need It in Supplement Form:

If you’re not consuming enough fruits and vegetables, a Vitamin C supplement can support your immune system and improve iron absorption.

Practical Tips for Choosing Vitamin Supplements

Check Labels Carefully: Make sure to choose supplements that are certified as vegan or vegetarian if necessary.

Opt for Bioavailable Forms: Some vitamins, like methylcobalamin (a form of Vitamin B12), are more easily absorbed by the body.

Consider Whole-Food-Based Supplements: These supplements are made from real food, making them more bioavailable.

Consult a Healthcare Provider: Before starting any supplementation regimen, it’s best to consult a healthcare professional to ensure you’re meeting your specific needs.

Final Thoughts

Supplementing your diet with the best vitamin supplements can make a significant difference in your overall health. Whether you’re focused on bone health, immune support, or filling in nutrient gaps, the right nutritional supplements will help you achieve balanced nutrition. Remember to choose supplements that suit your lifestyle, and always strive to maintain a nutrient-rich diet with a variety of whole foods.

With the right approach, incorporating these essential vitamins into your daily routine can promote long-term health and well-being.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Vegan Health Supplements: Top Picks for Maintaining Energy and Immunity

In recent years, the vegan diet has gained popularity for its health benefits and ethical considerations. However, ensuring you get all the necessary nutrients can be a challenge. Vegan health supplements can help bridge the gap, particularly when it comes to maintaining energy levels and boosting immunity. Here’s a guide to some of the top vegan supplements that can support your overall wellbeing.

1. Vitamin B12

Vitamin B12 is crucial for energy production and maintaining a healthy nervous system. Since B12 is primarily found in animal products, vegans need to supplement this vitamin to avoid deficiency. Look for B12 supplements in the form of methylcobalamin or cyanocobalamin, which are both effective.

2. Iron

Iron is essential for transporting oxygen throughout the body and preventing fatigue. While plant-based sources of iron (such as lentils and spinach) are available, they are not as easily absorbed as animal-derived iron. Vegan iron supplements, often in the form of ferrous bisglycinate, can help ensure adequate iron levels.

3. Vitamin D

Vitamin D plays a vital role in immune function and bone health. Since sunlight is the primary source of Vitamin D, and vegan foods are limited in this nutrient, a Vitamin D2 or vegan Vitamin D3 supplement can be beneficial, especially during the winter months.

4. Omega-3 Fatty Acids

Omega-3 fatty acids are important for heart health, brain function, and reducing inflammation. Flaxseed oil, chia seeds, and walnuts are plant-based sources, but an algae-based Omega-3 supplement can provide a more direct and effective dose of EPA and DHA, which are the active forms of Omega-3s.

5. Zinc

Zinc supports immune function and cell growth. While it is found in plant foods such as beans and nuts, the bioavailability can be lower compared to animal sources. A vegan zinc supplement can help ensure you are getting enough of this essential mineral.

6. Calcium

Calcium is crucial for bone health and muscle function. While many plant-based foods are fortified with calcium, supplements can provide an extra boost. Look for calcium citrate or calcium carbonate supplements, ensuring they are vegan-friendly.

7. Probiotics

Probiotics support digestive health and immune function. Vegan probiotics derived from non-dairy sources can help maintain a healthy gut microbiome, which is essential for overall wellbeing.

8. Vitamin K2

Vitamin K2 is important for bone health and cardiovascular function. It is less common in plant foods, so a vegan K2 supplement can help maintain optimal levels, especially for those who do not consume fermented foods.

Conclusion

Integrating these vegan health supplements into your routine can help maintain energy levels and bolster your immune system. However, it’s always a good idea to consult with a healthcare professional before starting any new supplement regimen, to ensure it aligns with your individual health needs and dietary preferences. With the right supplements, you can thrive on a vegan diet while keeping your energy levels high and your immune system strong.

#vegan health supplements#vegan diet supplements#halal food supplements#vegetarian supplements uk#healthcare#health & fitness#health and wellness

1 note

·

View note

Text

Why Vegan Hot Chocolate Powder?

Introduction: Why Vegan Hot Chocolate Powder?

A tasty mug of hot chocolate to unwind before bed will forever bring joy & comfort, particularly on cold winter evenings. However, with health consciousness becoming bigger, veganism has spurred more demand for alternatives that align with plant-based lifestyles, whilst still providing that comfort.

Enter vegan hot chocolate powder, better yet enter Calming Cocoa. Not only is Calming Cocoa vegan friendly, it’s packed with vitamins, minerals, no tropics & adapt gens to bring you so much more than a regular cup of vegan hot chocolate powder. Our innovative 3-in-1 super food powder not only satisfies your taste buds but, puts your personal wellbeing at the forefront.

What Makes It Vegan Hot Chocolate Powder?

Did you know that traditional hot chocolate, or cocoa powder, often contains milk powder or other dairy derivatives? That makes most commercial hot chocolate unsuitable for people who are following a vegan diet.

Vegan hot chocolate powder substitutes these ingredients with plant-based alternatives. Instead of using cow's milk, it usually employs non-dairy options including almond, coconut, oat, or soy milk. Vegan hot chocolate powder uses raw cocoa powder which avoids the use of any animal by-products, making sure that it has no dairy within.

Final Thoughts

Embracing vegan hot chocolate powder ultimately alights with ethical consciousness by avoiding ingredients that are derived by animals. We have shown that this can also offer sizeable health benefits.

Why not transform a daily guilt-conscious pleasure into seamless guilt-free indulgence? Savor every last drop of warmth and satisfaction with our Calming Cocoa super food blend.

For more information visit: https://www.nutrifizeltd.com/blogs/knowledge-with-nutrifize/why-vegan-hot-chocolate-powder

0 notes