#Weekly Margaret Magazine

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Ayaka To Perform Theme Song for The Rose of Versailles Film

Ayaka To Perform Theme Song for The Rose of Versailles Film #ベルサイユのばら #TheRoseOfVersailles #anime #manga #ベルばら映画 #ベルばら #ベルサイユのばら

Two months until the new animated film based on Riyoko Ikeda’s iconic Shojo manga, The Rose of Versailles makes its debut in Japan and it has been confirmed that Ayaka will be performing the film’s theme song. Singer and Songwriter Ayaka will be performing -Versailles-, where she shared her excitement and how honored that she was given the opportunity to perform music for the new film. Joining…

#Animation#Anime#Ayaka#ベルサイユのばら#Entertainment#france#Historical Fiction#Hitomi Kuroki#Manga#Mappa#Movies#Shojo#Shueisha Inc#Takarazuka#Takarazuka Revue#The Rose of Versailles#Toho Co.#UDON Entertainment#Weekly Margaret Magazine

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

This Christmas, I received perhaps the best gift I’ve ever been given in my entire life. My family partner in Japan tracked down the entire run of Margaret (マーガレット) magazine that published a Bewitched (奥さまは魔女) manga adaptation in 1967. This is the version featuring the art and writing of Masako Watanabe (わたなべまさこ).

When you have obscure interests like mine, you accept that most people can’t really give you many of the things you most want, which is fine of course, but it makes it all the sweeter when it does happen.

In addition to the Bewitched series, these magazines also contain chapters of the original Princess Comet (コメットさん) manga.

#weekly margaret#margaret magazine#margaret#bewitched#comet san#comet#princess comet#マーガレット#奥さまは魔女#コメットさん#昭和#showa era#魔法少女#magical girl#majokko#魔女っ子#retro shoujo#retro shojo#comics#manga#masako watanabe#わたなべまさこ

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

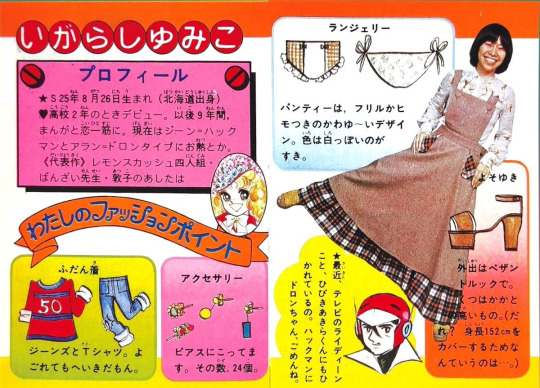

Shueisha Weekly Margaret 1973 and 1974

0 notes

Text

Loretta Swit

Actor who found global fame as the stern head nurse ‘Hot Lips’ Houlihan in the television sitcom M*A*S*H

The American actor Loretta Swit, who has died aged 87, achieved worldwide fame as Margaret “Hot Lips” Houlihan, head nurse with a mobile army hospital during the Korean war, in the TV sitcom M*A*S*H. She appeared in all 11 series, from 1972 to 1983 – longer than the conflict that inspired it – taking over the role played by Sally Kellerman in the 1970 film.

Misogyny ran throughout the big-screen version of M*A*S*H in a way that was not present in the 1968 novel by Richard Hooker on which it was based.In the TV version, too, Major Houlihan, a strict disciplinarian, was the butt of sexist jokes from the surgeons and other men in the 4077th Mobile Army Surgical Hospital unit, particularly “Hawkeye” Pierce (played by Alan Alda). Swit – who had the only leading female role in the show – took a stand before the fifth series began. She was then allowed to contribute to her character’s development, making Houlihan more three-dimensional, warm and brave. “I am a feminist, from the top of my head to the bottom of my toenail, and I favour playing strong women,” she told the American magazine Closer Weekly in 2022.

From then on, Swit’s character was referred to mainly by her real name rather than as “Hot Lips” and a more human side emerged when Houlihan broke down in front of her nurses, confessing she was hurt by the disdain they held for her because of her stern manner. The character’s long-running relationship with Major Frank Burns (Larry Linville) ended and she married Lieutenant Colonel Donald Penobscott (first played by Beeson Carroll and then Mike Henry), whom she later divorced when he cheated on her. Swit’s performance won her two Emmy awards as outstanding supporting actress in a comedy series, in 1980 and 1982.

She might have had global recognition for a second TV role, in a programme that was groundbreaking for its portrayal of women, if the M*A*S*H producers had not refused to let her out of her contract. Swit played the police detective Christine Cagney, alongside Tyne Daly as Mary Beth Lacey, in the feature-length 1981 pilot of Cagney & Lacey. It was the first American police drama to feature women in the two lead roles. In Cagney & Lacey, there was gritty realism and the authenticity of women balancing their work and home lives but, as Swit was unavailable, Meg Foster took over as Cagney when the series began, replaced after six episodes by Sharon Gless.

Swit never had another starring vehicle. “Actors are always identified with certain parts,” she said. “To some, Marlon Brando will always be the Godfather. That’s just how it is.”

Perhaps her best film role was as the first female American president – succeeding a former circus clown, a parody of Ronald Reagan – in Whoops Apocalypse (1986), the writers Andrew Marshall and David Renwick’s variation on their British sitcom.

Loretta was born in Passaic, New Jersey, to parents of Polish descent, Nellie (nee Kassack) and Lester Szwed, an upholsterer, who anglicised the family name to Swit. She attended Pope Pius XII high school, Passaic, where she appeared in school plays, and Gibbs College, Montclair, New Jersey, then had various secretarial jobs. Moving to New York, she trained in acting with Gene Frankel at the American Academy of Dramatic Arts, graduating in 1959. Her break in New York theatre came off-Broadway, at the Circle in the Square in 1961 when she joined the cast of the long-running Actors’ Playhouse production of The Balcony, by Jean Genet.

She spent the rest of the decade exclusively on stage until travelling to Hollywood in 1969. Then, she began to get small roles on television, including three in Hawaii Five-O (between 1969 and 1972) and two in Gunsmoke (both in 1970).

Later, she starred on Broadway as Doris in Bernard Slade’s “annual adultery” play Same Time, Next Year (Brooks Atkinson theatre, 1975-76), taking over the role originated by Ellen Burstyn. The New York Times observed that she gave a “stylish impersonation” of Burstyn, who had won a Tony award for her performance.

Swit was on Broadway again in Rupert Holmes’s musical version of Charles Dickens’s unfinished novel, The Mystery of Edwin Drood (Imperial theatre, 1985-86), replacing Cleo Laine in the dual roles of the Princess Puffer and Miss Angela Prysock. One stage part that seemed made for Swit was the title character in the British playwright Willy Russell’s one-woman show Shirley Valentine, which she took first in Chicago (Wellington and Wisdom Bridge theatres, 1990), then on an American tour (1995) and Canadian stages (1997 and 2010). The role of the bored Liverpool housewife escaping her humdrum life and uncaring husband had been played in the West End of London and the film version by Pauline Collins, who also took it to Broadway. Swit said of the character: “A lot of her experiences are universal – her ambition and desire, her lust for life and feelings of frustration at not fulfilling certain aspects of her own potential. I had kinship with her the moment I read the script.”

Eve Ensler’s comic and at times seriously political play The Vagina Monologues had Swit as one of the three women taking multiple roles, first at the Westside theatre in New York (1999), then in the West End (Arts theatre, 2001-02) and on an American tour (2002-03).

The actor was a passionate animal activist and supported many charities, as well as setting up her own, SwitHeart Animal Alliance. Her book SwitHeart: The Watercolour Artistry & Animal Activism of Loretta Swit was published in 2017.

Swit’s 1983 marriage to the actor and lawyer Dennis Holahan ended in divorce 12 years later.

🔔 Loretta Jane Swit, actor, born 4 November 1937; died 30 May 2025

Daily inspiration. Discover more photos at Just for Books…?

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

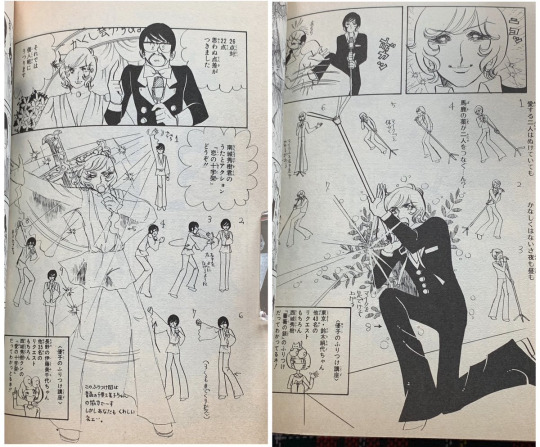

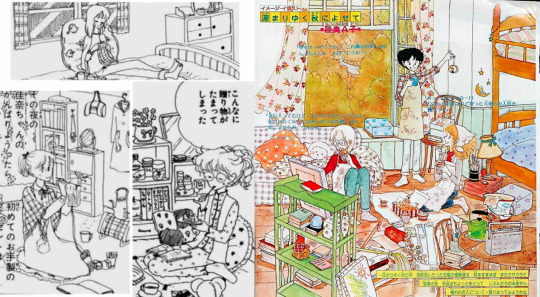

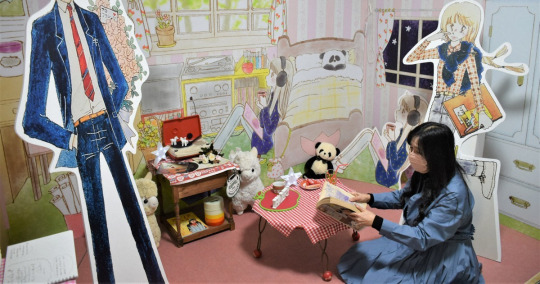

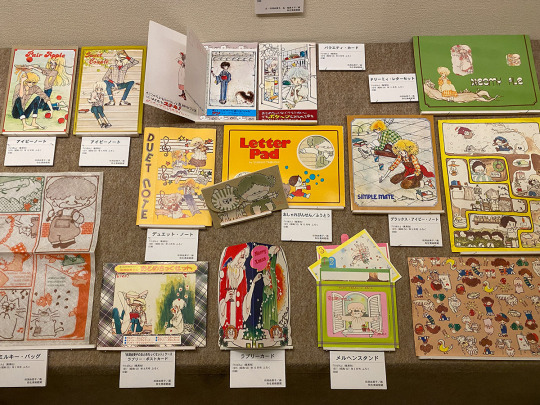

Shoujo Manga's Golden Decade (Part 2)

Shoujo manga, comics for girls, played a pivotal role in shaping Japanese girls’ culture, and its dynamic evolution mirrors the prevailing trends and aspirations of the era. For many, this genre peaked in the 1970s. But why?

Part 1

The Year of 24 Group

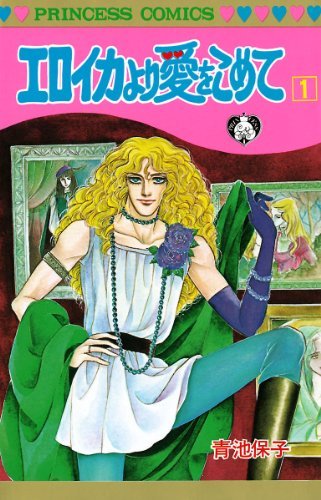

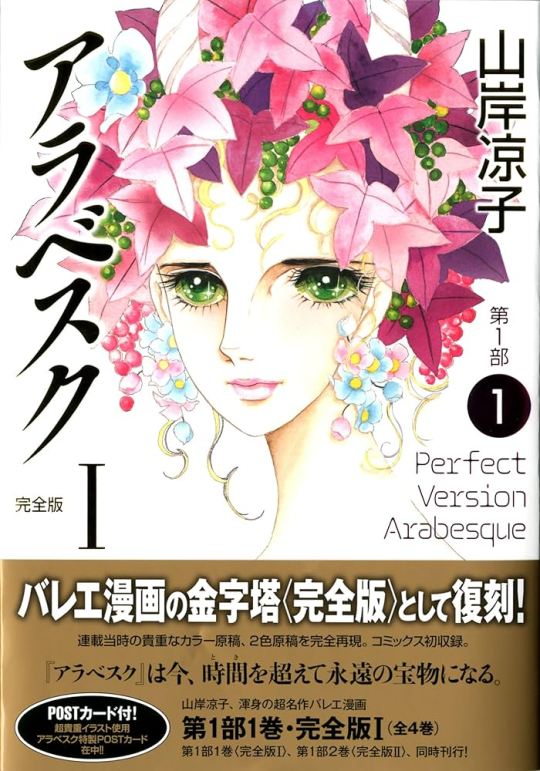

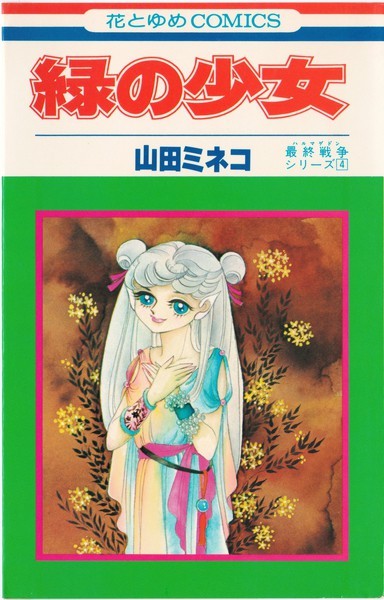

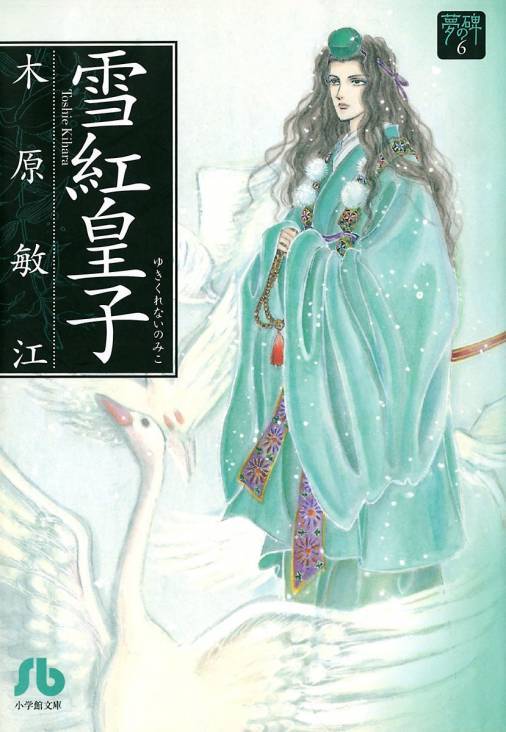

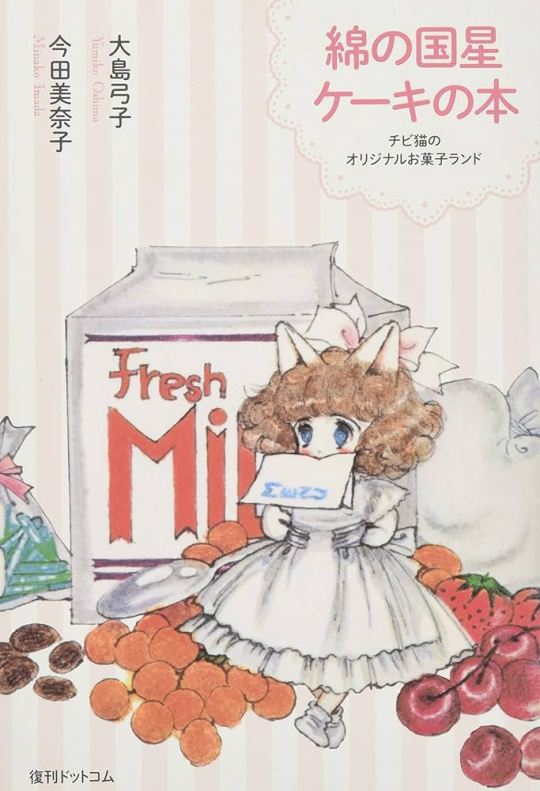

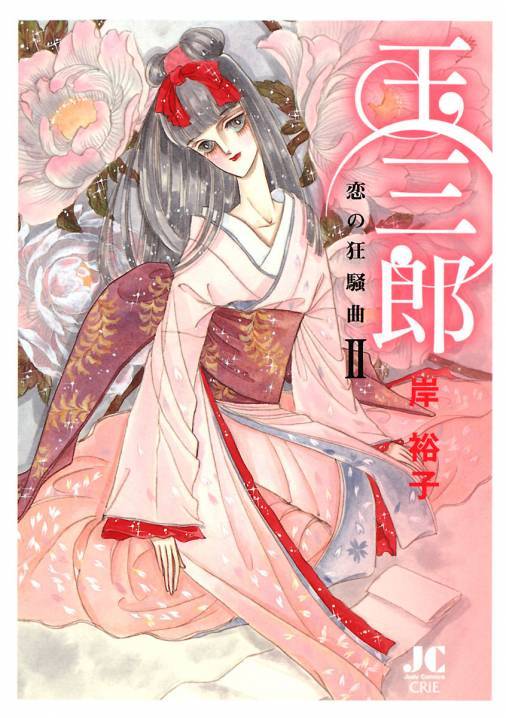

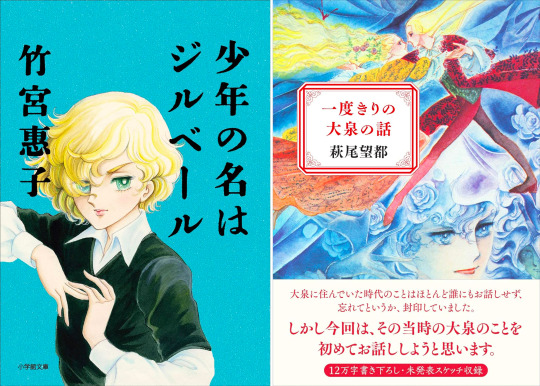

Some of the best-selling work by the Year 24 Artists (l-to-r): Yasuko Aoike's "From Eroica with Love," Ryoko Yamagishi's "Arabesque," Mineko Yamada's "Minori no Shoujo," Toshie Kihara's "Yomie no Ishibume," Yumiko Oshima's "The Star of Cottonland," Yuuko Kishi's "Tamasaburo."

Back in the early '70s, there was the prevailing notion that manga was for young kids. Despite the variety in themes, big magazines like Margaret, Shoujo Club, Nakayoshi, and Ribon were theoretically aimed at elementary school-aged girls.

In practice, the reality was more nuanced. Due to being published in Weekly Margaret, "The Rose of Versailles" was for kids. And it did very well with them. Yet, its revolutionary romance also appealed to broader audiences, exemplifying the crossover potential of shoujo manga. It was the title that opened the door for what is known as "the golden age of shoujo," which was further cemented by several other groundbreaking hits.

These hits widened the shoujo manga field, and soon, other editorial houses also wanted to cash in. Shogakukan, which published the powerful Weekly Shonen Sunday, entered the shoujo market in the late '60s. Shueisha and Shogakukan also partnered to form a keiretsu and open the Hakusensha publisher which deals mostly with shoujo manga.

That is the context in which a batch of artists known as "The Magnificent 24 Group" rose. And they were another key reason as to why '70s shoujo made such a mark. These manga-kas introduced themes such as sci-fi and homosexuality to the segment, revolutionized its art, further explored historical and terror narratives, and generally broke barriers of what was possible in shoujo manga. Their work was intellectually challenging, philosophical, and, above all, fundamental for male manga critics and connoisseurs to finally take shoujo seriously.

The Year 24 Group refers to the fact most artists were born around 1949, which is known as the year 24 of the Showa era in the Japanese calendar. These women came of age during the time artists like Hideko Mizuno were debuting and doing revolutionary work in the shoujo field, and they were eager to follow their lead. The success of unorthodox hits like "The Rose of Versailles" and the emergence of new magazines enabled them to be bold.

The two artists who led the movement are Moto Hagio and Keiko Takemiya. Their shared house in Tokyo, known as the Oizumi Salon, became a gathering place for several young artists keen on breaking new grounds for shoujo manga-kas. These women became the Year 24 group. But there were other two people, besides the artists themselves, who were just as crucial for their collective rise.

Firstly, there was Junya Yamamoto. Yamamoto was a young male editor at Shogakukan who had risen through the ranks of the successful Shonen Sunday weekly manga magazine. Noticing they were lagging behind Shueisha and Kodansha in the manga segment for their lack of a robust shoujo presence, the editorial house appointed Yamamoto to launch Shoujo Comic (known as Sho-Comi) in 1968 and Bessatsu Shoujo Comic (known as Betsucomi) in 1970. However, he quickly ran into an issue: most successful shoujo artists already had exclusive contracts with the competing houses, and aspiring names were vying for positions at the already established titles.

In 1969, the "God of manga," Osamu Tezuka, introduced Yamamoto to Keiko Takemiya, then a university student living in Tokushima City. Takemiya had spent her school years dreaming of becoming a manga-ka and participated extensively in the readers' corner section of COM. COM was an avant-garde manga magazine Tezuka founded to nourish young talents and publish stories without the typical restraints of more commercial shoujo and shonen publications. In her first year of college, Takemiya won a Shueisha's Weekly Margaret newcomer competition and had a work published in the magazine. Still, she was persuaded by her parents to focus on her studies instead and to leave manga as a side hobby.

Yamamoto, in turn, was impressed with her talent and convinced her to chase her dreams. Quickly, she found work in all three publishers and started simultaneously publishing in Kodansha, Shueisha, and Shogakukan's shoujo titles.

Meanwhile, Moto Hagio also grew up enamored with the manga world. During her college years, she had a work selected by Shueisha's Bessatsu Margaret (Betsuma) through a competition, but she could not find a fixed slot in the magazine. Then, she got introduced to Kodansha's Nakayoshi editors, who were impressed by her talent. While she did start publishing short stories there, editors rejected most of her submitted work as they did not fit the magazine's mold. One day, an editor introduced her to Takemiya, who, overworked while working for several magazines, was in dire need of an assistant. The two hit off, and Takemiya, who until then had her permanent residence in far away Tokuma City but was planning a move to Tokyo, proposed they both live together. She also decided to introduce Hagio to risk-taker editor Yamamoto, who, impressed by her talent, encouraged her to pursue her path instead of trying to fit into the expected shoujo template.

Then there was Norie Masuyama, who first became acquainted with Moto Hagio before becoming Takemiya's manager. Hagio was from Fukuoka, while Masuyama was from Tokyo, but due to their similar interests, they became penpals. When Hagio first moved to Tokyo, Masuyama hosted her in her home in Oizumi. Eventually, Hagio introduced Masuyama to Takemiya, and the three of them became close. Because both were artists from outside of Tokyo, Masuyama was the one who first circled the idea they should live together (something Yamamoto presciently warned it could turn into a problem), and she was the one who alerted them of a house in her Oizumi neighborhood being up for rent.

Keiko Takemiya and Moto Hagio, estranged since the late '70s, revealed details of their feud in autobiographic books: Takemiya's "Shonen no na wa Gilbert" (2019) and Hagio's "Ichidou kiri no Oizumi no Hanashi" (2021). The dispute, stemming from Takemiya accusing Hagio of plagiarism, was fueled by Takemiya's jealousy during a challenging creative and personal period. While Takemiya appears self-aware and analytical in her account, Hagio's book indicates she hasn't forgiven Keiko, revealing unresolved feelings. The publications triggered intense online debates.

Masuyama came from a sophisticated family that was very involved in arts and, from a young age, got familiarized with the world of music, literature, and movies. Her refined taste impressed Hagio and Takemiya. At a time when Japanese girls dreamed of Europe, Masuyama actually had friends living there and was up-to-date on the latest European trends. She also had a lot of knowledge of European cinema and literature.

As their rented house was old and rusty, Hagio and Takemiya started spending a lot of time at Masuayama's house across the street. She introduced them to films, songs, books, and paintings. It was Masuyama's taste -- including her interest in movies and books depicting gay romance and her desire for girls' comics to have bolder and riskier themes -- that helped to instill a passion in both artists to go further than the safe cliches usually depicted in shoujo works.

In 1970, editor Yamamoto convinced Takemiya to sign an exclusive contract with Shogakukan. The following year, Hagio also started publishing for Sho-comi and Betsucomi. Their work would attract a loyal fanbase, and aspiring manga-ka would flood their mailboxes. So Takemiya made a decision: to select female artists around her and Hagio's age to mentor and train at their shared home. Thus, the Oizumi Salon was born.

Despite attracting attention, Takemiya and Hagio's works were not always popular. In fact, they'd often rank last in readers' popularity polls, which tend to be all-deciding in manga magazines. But they persevered, and Yamamoto trusted them.

Keiko Takemiya aimed to establish herself with a top-rated series through "Pharaoh no Haka" (left) in order to garner the necessary respect from editors to write the series she wanted, "Kaze to ki no uta" (right). Despite her resolute efforts, "Pharaoh no Haka" never secured the top spot in Sho-comi's readers' poll, peaking at #2. Nevertheless, the series succeeded in elevating her fame and earning her the respect she sought.

In 1972, Hagio had an idea for a serial focused on a male European vampire. However, as she wasn't a famous artist, Yamamoto only allowed her to publish one-shots. So she came up with a plan: to write three interconnected standalone stories. To circumvent another restraint - shoujo editors' avoidance of male leads - she put the first story focus on Marybelle, Edgar's sister. Once Yamamoto realized what Hagio was doing, he was amused and allowed her to continue. And so, "The Poe Clan" series began. In 1974, Shogakukan finally started publishing their shoujo titles in compiled paperback format. In another proof of trust, Yamamoto chose Hagio's "The Poe Clan" as the first title of the Flower Comics imprint.

To everybody's surprise, "The Poe's Clan," in paperback format, was a groundbreaking success, almost instantaneously selling out its initial printing. At the time, Hagio had just started a new serialization, "The Heart of Thomas," a tragic gay love story set in an all-boys German school. As usual for her, the story wasn't all that popular with Sho-Comi's readership, and its lackluster results in the reader's poll almost got the series discontinued. But the notable success of "The Poe's Clan" tankobon assured editors, who allowed Hagio to continue the series. "The Heart of Thomas" went on to become another best-seller and a seminal shoujo title. It also attracted critical acclaim and a loyal fanbase to Moto Hagio, which in turn helped put the Year 24 artists -- who were pretty good at self-promotion -- in the spotlight.

Hagio, Takemiya, and several other "Year 24" authors drifted between being popular and underground. They had a sizable, loyal fanbase that followed them and turned several of their works into best-sellers. On the other hand, by finding a way around the usual shoujo traditions, they weren't particularly popular with the average shoujo reader, ordinary young girls across the country craving more traditional story-telling.

Their peculiar position forced them to be clever, so they could fulfill their creative desires as well as their editors' expectations, who were there to make sure the stories published were satisfying to the core readership. Takemiya wrote "Pharaoh no Haka," an Egypt-set romantic adventure, to be well-accepted so that she could then dedicate herself to doing what she truly wanted in "Kaze to Ki no Uta," a gay love story set in a 19th Century French boarding school.

Initially overlooked in popular shoujo magazines, Moto Hagio gained success with "The Poe Clan" in compiled format, launching Shogakukan's Flower Comics imprint. Over time, she became a highly respected manga artist, the only manga-ka alongside legendary filmmaker Hayao Miyazaki to receive a Person of Cultural Merit recognition. In 2016, marking 40 years of the conclusion of her first hit, she released a new "The Poe Clan" chapter in Flower magazine, selling out the increased print run of 50,000 copies in a day. This success marked a significant shift for Hagio, who, despite not being a major magazine seller in earlier years, became a valuable asset to the struggling magazine publishing industry decades later. Following the one-shot, she released three more chapters and, in 2022, began a new sequel series.

Besides Takemiya and Hagio, several other notable shoujo artists who went on to become huge names used to frequent the Oizumi Salon and were part of the "Year 24 group." In the early '70s, most published their work on Shogakukan's titles, which had a "free policy" on storytelling compared to Margaret, Shoujo Friend, Nakayoshi, and Ribon. Then, as Shogakukan started being more strict to properly compete with the market leaders, several moved to newly launched Hakusensha titles Hana to Yume and LaLa. Influential names that were part of the movement included Yumiko Oshima, Yasuko Aoike, and Ryoko Yamagashi, among several others.

Despite their unorthodox preferences, they weren't necessarily trying to rebel against the system, they simply wanted to put out good quality work they believed in. Like other Japanese girls from that era, they were fascinated by Europe, and plenty of their stories took place on the continent. In 1972, Hagio, Takemiya, Yamagishi, and Masuyama made a 45-day trip to Europe, visiting the Soviet Republic, France, and several other countries, which had a profound impact on them. Still, their narratives were widely innovative. They often had male leads, introduced sci-fi, "boys' love," and other bolder genres to shoujo manga, and contributed to the evolution of shoujo illustration. Above all, this group of artists was the one who made clear to naysayers, once and for all, that shoujo manga is indeed an art form.

But while their influence in manga history is undisputed, other significant -- and much more commercial -- manga movements also shook the shoujo manga world during that decade.

A Need for Drama

When talking about '70s shoujo manga, it's common for minds to drift directly to iconic series from that time, like "Candy Candy" and "Rose of Versailles." But, unlike in present times, in that decade, the manga industry's focus wasn't on successful, long-running series but on the artists themselves.

As opposed to the struggling publishing marketing of today, major shoujo manga magazines all sold over 1 million copies during that decade. Manga in tankobon (standalone paperback) format was turning into a money-maker field, but being able to sell paperback was very much secondary compared to being a name capable of selling magazines. Keiko Takemiya and Moto Hagio, from the Amazing Year 24 Group, would go on to become household names and had best-selling series, but, at the time, they couldn't compete with the actual shoujo manga superstars who were the signboard artists of the Kodansha and Shueisha's shoujo titles, the ones who actually moved publications. These artists' work was the most significant indicator of what the mainstream readers wanted and aspired to back then.

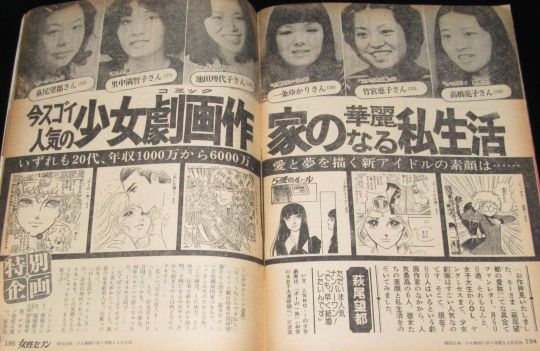

In a December/1975 issue, weekly Josei Seven spotlights the new generation of superstar shoujo manga artists: (l-to-r) Moto Hagio, Machiko Satonaka, Ryoko Ikeda, Yukari Ichijo, Keiko Takemiya, and Ryoko Takahashi. While contemporary manga-kas are highly discreet about their lives and do not even tend to show their faces, in the '70s, they were treated like superstars, and, in the article, the manga-kas openly discuss their love life and details of their high incomes, including how much they had in the bank and how much they spent on rent and daily utilities. (image source)

For Kodansha, the top shoujo artist was definitely Machiko Satonaka, who won the Best New Artist competition in 1964, when she was still a freshman in high school. There have been several high-schoolers making their debut in the industry throughout the decades, but, as the first, Satonaka caused a media frenzy. Her ascent gave confidence to countless other young women -- from "Glass Mask"'s Suzue Michi to Keiko Takemiya (who also won a smaller prize in the same competition) -- to pursue their manga careers.

The attention surrounding Satonaka, who went on to become a public personality with TV hosting gigs and other appearances, is another interesting, nostalgic phenomenon. In the past, it was common for manga superstars to have a strong media presence. Nowadays, the norm is the complete opposite: for manga-kas to be highly private, no matter how famous their work is.

In any case, Satonaka quickly proved herself to be more than a sensational news story as she created extremely popular mangas for Kodansha shoujo titles like Shoujo Friend and Nakayoshi. Her style, widely accepted by readers, became symbolical of the story-telling the '70s girls craved: extremely dramatic with emotionally driven plots and lots of bombastic twists and developments.

In his book on subcultures and otaku culture, sociologist Shinji Miyadai notes that '70s shoujo manga can be divided into very few categories. There is the category the Year 24 artists dominated -- which he defines as the "Moto Hagio domain" -- of works with a lot of artistic value, up-to-par with literature. And then there's the far more commercially viable "Satonaka domain," which represented the mainstream taste.

In the "Satonaka category," the artist depicts a stormy life story as a proxy experience for the readers. Of course, there are universal elements of love, friendship, and insecurity that girls can directly relate to. Still, these stories provide adventures that readers could never experience in the real world.

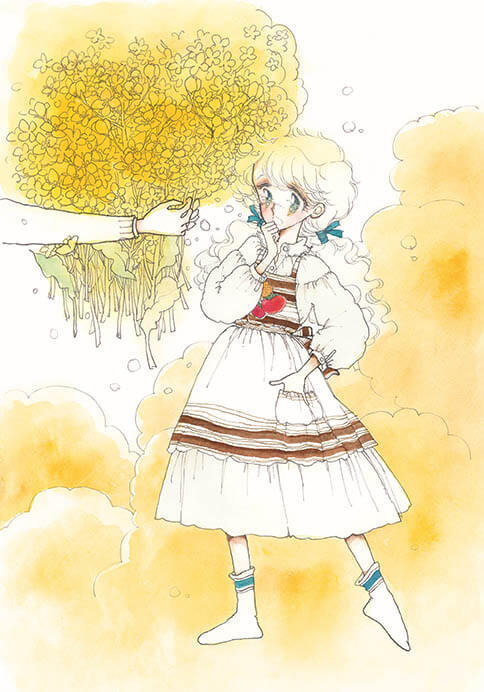

These facets of the "Satonaka domain" are present in almost all the best-selling, mainstream shoujo series of the '70s, like the revolutionary historical romance of "The Rose of Versailles," the dramatic rags-to-riches story of the beautiful orphan in "Candy Candy," and the rise of an ordinary girl to the top of the sports elite in "Ace wo Nerae." In all of these titles, you'll also spot other defining characteristics of '70s shoujo: the death of beloved characters and well-liked female characters with voluminous blonde hairs and huge, sparkling eyes (a legacy of Macoto Takahashi, the illustrator who, throughout the '50s, created the art that directly influenced subsequent shoujo history).

Yukari Ichijo was the most prominent Ribon signboard artist throughout the '70s, creating popular mangas like "Suna no Shiro" (left) and "Designer (right). Young girls across the country adored her work despite the adult drama in it.

Since these stories are extraordinary and dream-like, many of them use Europe or the US as their setting, another reflection of a time when Japanese youth dreamed with the West.

While Satonaka was Kodansha's star, Shueisha also had its top shoujo artists. For Margaret, it was Ryoko Ikeda who kept creating memorable dramatic manga after the conclusion of "The Rose of Versailles." Other classic '70s dramatic works published in the weekly included Kyoko Ariyoshi's ballet drama "Swan." Meanwhile, over at Ribon, no one shone brighter than Yukari Ichijo. Ichijo's works, which young girls across Japan devoured, contained a lot of adult drama with adult characters. Her 1974 manga, "Love Game," had a bed scene. One of her most celebrated works of the decade, "Suna no Shiro" (Sand Castle), dealt with incest. While Ichijo is the one who stood the test of time, another artist who also enjoyed great popularity in Ribon following this formula was Kei Nogami.

These mangas served as an escape for girls, who left their ordinary school life behind for a few hours to embark on extraordinary adventures. In contrast, one of the main genres in contemporary shoujo is unassuming, everyday high school romance. How could the shoujo segment go through such a drastic transformation? The reasons for that also dates back to the 1970s.

Part 3

#shoujo manga#vintage shoujo#otometique#yumiko oshima#keiko takemiya#yumiko tabuchi#hideko tachikake#machiko satonaka#yukari ichijo#ribon#1970s japan#1970s#year 24 group#moto hagio#vintage manga

106 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Fairytale for Christmas

Summary: When Robin Locksley plans a masquerade for businesswoman and heiress Regina Mills, he just hopes to expand his client list. He gets much more when he takes his cousin’s place as a guest at the party and makes a connection with one of the guests. The next day, he learns that person was in fact the hostess, Regina Mills, and that her mother has announced that Regina will marry whoever that man was. His cousin Keith figures out it was Robin and teams up with Cora Mills to marry Regina, pulling in his cousin to their deception. But as Robin gets closer to Regina, will he tell her the truth or watch the love of his life walk down the aisle to his cousin?

Chapter 1: FFN | AO3 | Wattpad

Chapter 13

FFN | AO3 | Wattpad

Excerpt:

Sunshine warmed Regina's face as she stood by her bedroom window, watching as workers erected a white tent in her backyard while tables and chairs waited to be set up underneath the tent. A few other people set up a large flower wall near the walkway leading from her circular driveway to her patio. There was a white van parked near them and she knew there were more floral arrangements waiting to be unloaded. Everything was already coming together.

"Today's the day," she said, turning from the window to address the small form lying on her bed. "Today I marry your daddy."

Tuck just continued to lay on his side, unimpressed by anything happening around him.

She chuckled, sitting on the edge of the bed as she scratched behind his ear. "I know nothing is going to change for you. But today is still a really big day for Robin and me. It's the first day of the rest of our lives."

"Yes, it is," Mary Margaret agreed, one hand on the doorknob while she leaned through the partially opened door. "And you should start the day with a good breakfast. Granny's already in the kitchen making it."

"I'll be down in a few minutes then," Regina said, smiling at her friend. "Just let me put on my robe."

Mary Margaret nodded. "Take your time. The hair and makeup team won't be here for another hour at the very least."

She closed the door behind her before Regina stood, walking over to her closet. Regina opened it and pulled out her favorite purple robe, slipping it on and tying the sash into a loose knot. With that done, she scooped up Tuck and held him close. "Come on. I'm sure you want breakfast too," she said.

Tuck purred in her arms as she left the bedroom, walking down the hallway toward the stairs and eventually her kitchen. Along the wall were several pictures, many hung in the past couple years after she learned the house was hers. Even though she hadn't lived there herself, Mother had insisted that Regina keep the mansion looking exactly the way she had decorated it, where every room looked like a magazine photoshoot come to life and with almost no personal touches. The house had only been for show, to display their wealth, and not to really be a home.

Regina finally made it the home her father had wanted it to be.

She had found pictures of herself and Daddy over the years and had them framed, hanging them in the hallway. And then she added pictures of herself with those she loved, including Granny, Mary Margaret and Mal. But now most of the pictures were her and Robin and if she was honest, those were her favorites.

Most were pictures from their travels around the world but there were a few from photoshoots done to accompany stories written about them. After she took over her family's company and Robin relaunched his party planning business as Sherwood Special Events, they became Storybrooke's newest power couple. Several articles were written about them – both for their individual work as well as them as a couple – and she had chosen to frame her favorites.

Like the one done by the Daily Mirror's weekly cooking section. The reporter had come out to their house to write about them after learning they both loved to cook. She wanted to learn the recipe behind Robin's now famous dumplings but he politely refused, saying they were key to his success. Instead, he and Regina made her apple turnovers instead along with his quiche recipe. Her favorite picture showed them laughing in the kitchen as they prepared the dough, their faces and hair covered in flour as they wore matching aprons.

Regina never knew doing interviews and posing for pictures could be fun until she met Robin.

She headed downstairs and entered the kitchen, greeting Granny and Mary Margaret warmly. Granny smiled as she tapped the chair Regina preferred. "Your breakfast is all ready for you," she said. "Have a seat and enjoy."

"One minute," Regina said, picking up Tuck's bowl. "I have to give someone else their breakfast first or we will not hear the end of it."

"True," Granny replied, knowing how loud Tuck could get when he was not fed on time. "Go ahead."

Regina nodded, filling his bowl with his favorite dry food. He began to squirm in her arms, eager to enjoy his meal. She chuckled as she carried it over to its spot on the floor. "Almost there," she said.

She placed the bowl down and then set Tuck down as well. "Go ahead. Enjoy," she said.

"He's a very spoiled kitty," Mal said, sipping her coffee as she watched Tuck eat his breakfast.

"He is a very loved kitty," Regina replied, glancing over at him. "Robin sometimes jokes that he doesn't know who I love more – him or Tuck."

Mary Margaret chuckled. "Well, I think we all know the answer to that."

Granny nodded. "It's the cat."

"Yes," Regina said. "Exactly."

They paused for a moment before they burst out laughing. Regina loved that they could joke and have fun like this. And that her friends knew she loved Robin with everything she had. He had her whole heart and that was why she was marrying him.

Why she wanted to spend the rest of her life with him.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Holidays 11.23

Holidays

Arethusa Asteroid Day

Armed Forces Day (Lithuania)

Asian Corpsetwt Day [Every 23rd]

Big Help Day

Can You Find Your Old Rubik’s Cube and Still Work It Day

Chicory Day (French Republic)

Color Photos Day

Cutty Sark Day

Doctor Who Day

Do What the Heck You Want Day (Oklahoma)

Family Volunteer Day

Felt Day

Fibonacci Day

Flag Day (Niger)

Flipbook Day

Giorgoba (St. George's Day; Georgia)

Hadakambo Festival (Japan)

International Day of the Word

International Day to End Impunity

International Image Consultant Day

International Polyamory Day

Jukebox Day

Kinrō Kansha no Hi (Labor Thanksgiving Day; Japan)

Life Magazine Day

Madison Beer Day (New York)

Monkey Banquet (Thailand)

National Adoption Day

National Day to Combat Child & Youth Cancer (Brazil)

National Margaret Day

National Polyamory Day (Canada)

National Survivors of Suicide Loss Day

Nursing Support Workers Day (UK)

Old Clem’s Night (Blacksmith Festival)

One Cup of Tea Day (Japan)

Paranoia Day

Pencil Sharpener Day

Repudiation Day (Maryland)

Rudolf Maister Day (Slovenia)

Seng Kut Snem (Meghalaya, India)

TARDIS Day (Dr. Who)

Thankful For My Dog Day

Thespius' Day (Greek Mischief Ghost)

Traffic Police Day (Kazakhstan)

Virtual Reality Day

Wolfenoot

World Watercolor Day

Food & Drink Celebrations

Eat a Cranberry Day

National Bar Day

National Cashew Day

National Espresso Day

Independence & Related Days

Luxembourg (Separated from Netherlands; 1890)

St. Charlie (Declared; 2008) [unrecognized]

4th Saturday in November

Holodomor Remembrance Day (Ukraine) [4th Saturday]

International Aura Awareness Day [4th Saturday]

Salacious Saturday [4th Saturday of Each Month]

Sandwich Saturday [Every Saturday]

Sausage Saturday [4th Saturday of Each Month]

Six For Saturday [Every Saturday]

Spaghetti Saturday [Every Saturday]

Weekly Holidays beginning November 23 (3rd Full Week of November)

Sherlock Holmes Wekend (thru 11.24)

Festivals Beginning November 23, 2024

Burbank Winter Wine Walk (Burbank, California)

Cheese and Chocolate Weekend (Chisago City, Minnesota) [thru 11.24]

Cheese & Meat Festival (Portland, Oregon)

Festival of Trees (Methuen, Massachusetts) [thru 12.7]

Holiday Celebration and Winter Market (Rapid City, South Dakota)

Holiday Fineries at the Wineries (New Paltz, New York) [thru 11.24]

Holiday Light Parade (Baraboo, Wisconsin)

Jingle Bell Chocolate Tour (Jackson, New Hampshire) [thru 12.22]

Magnificent Mile Lights Festival (Chicago, Illinois)

Maine Harvest Festival (Bangor, Maine) [thru 11.24]

Monkey Buffet Festival (Lopburi, Thailand) [thru 11.24]

Mount Clemens Santa Parade (Mount Clemens, Michigan)

Natchitoches Christmas Festival (Natchitoches, Louisiana) [1.6.2025]

New York Craft Brewers Festival (Syracuse, New York)

Serbian Food Festival & Bazaar (Lenexa, Kansas)

Stockholm Christmas Market (Stockholm, Sweden) [12.23]

Tokyo Filmex (Tokyo, Japan) [thru 12.1]

Wi-Does Wine Walk (Eagle River, Wisconsin)

Yankeetown Art, Crafts & Seafood Festival (Yankeetown, Florida) [thru 11.24]

Feast Days

Alexander Nevsky (Repose, Russian Orthodox Church)

Amphilochius, Bishop of Iconium (Christian; Saint)

Chiron’s Day (Pagan)

Clement I, Pope (Roman Catholic Church, the Anglican Communion, and the Lutheran Church)

Columbanus (Christian; Saint)

Daniel (Christian; Saint)

D'Aranda (Positivist; Saint)

Derek Walcott (Writerism)

Erté (Artology)

Feast of Qawl (Speech; Baha'i)

Feast of the Wizard-Blacksmith (Saxon; Everyday Wicca)

Felicitas of Rome (a.k.a. Felicity; Christian; Saint)

Fountain of Riddles (Muppetism)

Frederick Nietzsche Day (Church of the SubGenius; Saint)

Fred Wah (Writerism)

General Debauchery Day (Pastafarian)

Gregory of Girgenti (Christian; Saint)

José Clemente Orozco (Artology)

Konstantin Korovin (Artology)

Marc Simont (Artology)

Mary Brewster Hazelton (Artology)

Miguel Agustín Pro, Blessed (One of Saints of the Cristero War; Roman Catholic Church and the Lutheran Church)

Niiname-Sai (Japanese Grain Festival)

Paulinus of Wales (Christian; Saint)

Shinjosai Festival (Rice Harvest; Celebrating Granddaughter Goddess of Solar Deity Amaterasu; Japan)

Stendahl (Writerism)

Trudo (a.k.a. Trond or Troll; Christian; Saint)

Wilfetrudis (a.k.a. Vulfetrude; Christian; Saint)

Woofenoot (Pastafarian)

Lucky & Unlucky Days

Lucky Day (Philippines) [64 of 71]

Tomobiki (友引 Japan) [Good luck all day, except at noon.]

Premieres

Against the Grain, by Bad Religion (Album; 1990)

Areopagitica, by John Milton (Pamphlet; 1644)

Another Brick in the Wall (Part 2), by Pink Floyd (Song; 1979)

Arthur Christmas (Animated Film; 2011)

The Artist (Film; 2011)

The Atrocity Exhibition, by J.G. Ballard (Novel; 1970)

Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, by Roald Dahl (Novel; UK 1964)

Chinese Democracy, by Guns ’N’ Roses (Album; 2008)

The Dance Contest (Fleischer Popeye Cartoon; 1934)

Devotion (Film; 2022)

Doctor Who (UK TV Series; 1963)

Doggystyle, by Snoop Doggy Dogg (Album; 1993)

The Expanse (TV Series; 2015)

The Exterminator (Terrytoons Cartoon; 1945)

The Favourite (Film; 2018)

Fish and Chips (Chilly Willy Cartoon; 1962)

Flying Colours, by C.S. Forester (Novel; 1938)

For Those About To Rock We Salute You, by AC/DC (Album; 1981)

G.I. Blues (Film; 1960) [Elvis Presley #5]

Glass Onion (Film; 2022)

Hugo (Film; 2011)

Inner Workings (Disney Cartoon; 2016)

It’s Only a Flesh Wound or Better Lead Than Dead (Rocky & Bullwinkle Cartoon, S6, Ep. 322; 1964)

Just Friends (Film; 2005)

The Lonesome Stranger (MGM Cartoon; 1940)

Love in a Cold Climate, by Nancy Mitford (Novel; 1949)

Moana (Animated Disney Film; 2016)

Mouse Trouble (Tom & Jerry Cartoon; 1944)

The Muppets (Film; 2011)

Mrs. Parker and the Vicious Circle (Film; 1994)

My Sweet Lord, by George Harrison (Song; 1970)

No Smoking (Disney Cartoon; 1951)

Pretty Peaches (Adult Film; 1978)

Of Mice and Men by John Steinbeck (Novel; 1937)

Pride & Prejudice (Film; 2015)

Scrooged (Film; 1988)

Small Fry (Pixar Cartoon; 2011)

Strange World (Animated Disney Film; 2022)

Tampopo (Film; 2016)

Tea For The Tillerman, by Cat Stevens (Album; 1970)

The Ten Commandments (Film; 1923)

Terms of Endearment (Film; 1983)

The Three Musketeers (Hanna-Barbera Animated TV Special; 1973)

Tito’s Guitar (Color Rhapsody Cartoon; 1942)

Wednesday (TV Series; 2022)

The Worrying’ of the Green or The Look of the Irish (Rocky & Bullwinkle Cartoon, S6, Ep. 321; 1964)

Today’s Name Days

Clemens, Columban, Detlef (Austria)

Aleko, Aleksandar, Aleksandra (Bulgaria)

Klement, Kolumban, Lukrecija (Croatia)

Klement (Czech Republic)

Clemens (Denmark)

Kleement, Leemet, Leemo (Estonia)

Ismo (Finland)

Clément (France)

Clemens, Columbia, Detlef, Salvator (Germany)

Amfilohios, Elenos (Greece)

Kelemen, Klementina (Hungary)

Clemente, Colombano (Italy)

Zigfrīda, Zigrīda, Zigrids (Latvia)

Adelė, Doviltas, Klemensas, Liubartė (Lithuania)

Klaus, Klement (Norway)

Adela, Erast, Felicyta, Klemens, Klementyn, Orestes, Przedwoj (Poland)

Antonie (Romania)

Klement (Slovakia)

Clemente, Lucrecia (Spain)

Klemens (Sweden)

Augusta, Augustina (Ukraine)

Clem, Clemence, Clement, Clementina, Clementine, Crecia, Lucrecia (USA)

Today is Also…

Day of Year: Day 328 of 2024; 38 days remaining in the year

ISO: Day 6 of Week 47 of 2024

Celtic Tree Calendar: Hagal (Hailstone) [Day 28 of 28]

Chinese: Month 10 (Yi-Hai), Day 23 (Xin-Mao)

Chinese Year of the: Dragon 4722 (until January 29, 2025) [Wu-Chen]

Hebrew: 22 Heshvan 5785

Islamic: 21 Jumada I 1446

J Cal: 28 Wood; Sevenday [28 of 30]

Julian: 10 November 2024

Moon: 43%: Waning Crescent

Positivist: 20 Frederic (12th Month) [Campomanes / Turgot]

Runic Half Month: Is (Stasis) [Day 2 of 15]

Season: Autumn or Fall (Day 62 of 90)

Week: 3rd Full Week of November

Zodiac: Sagittarius (Day 2 of 30)

1 note

·

View note

Note

LMAOO I am literally making a magazine cover rn😭😭

ANYWAY great question:

1. Vogue - 100% Lorelei she has covered the magazine 3 times already!!

2. Sports Illustrated - Probably George

3. Time - Queen Margaret (rip), shes achieved a lot in her life and is very philanthropic! Also the oldest member of the windenburg royal family

4. Forbes - Prince Michael, he is very business savy in many ways! i dont want to go into detail but i will when his update comes 👀

5. Womens Health - Gotta say Lorelei again!! She is definitely obsessed with fitness and her appearance!

6. US Weekly - Princess Madeleine, primarily because of who she marries 👀

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

For manga,look up in which magazine its published. The genres are defined entirely by the magazine

Example

Shounen Magazines: Weekly Shōnen Jump,Champion Red,Jump Square,Monthly Shōnen Champion etc

Shojo Magazines:Nakayoshi!,Ribon!, Sho-comi,Margaret,Hana to Yume etc

Seinen Magazines:Young Animal Arashi, Big Comic Spirits, Manga Action,Good! Afternoon,Dengeki Maoh etc

Josei Magazines:Cookie,Chorus,YOU,Silky, Feel Young etc

(These are not recommendations, just examples :P)

ppl are so mad in the replies to this tweet but op is literally right

25K notes

·

View notes

Text

Acknowledgments

This book could not have been written without Eunice. She watched and transcribed everything from professional wrestling, to reality television shows, to the scenes described in the chapter on pornography. She edited and rewrote passages. She clarified incomplete thoughts, challenged shaky assertions, and added paragraphs that always enhanced the points I was trying to make. She stayed up many nights long after I had gone to bed, reworking sections of the book. Nothing I write is published before it goes through her hands. Our marriage is a rare combination of spiritual and intellectual affinity. “She’is all States, and all Princes, I, Nothing else is,” as John Donne wrote in his poem “The Sunne Rising”:

Princes doe play us; compar’d to this,All honor’s mimique; all wealth alchimie.Thou, sunne, art halfe as happy’as wee,In that the world’s contracted thus.

I am deeply indebted to The Nation Institute and the Lannan Foundation. The support of these organizations permitted me to write this book. I am especially grateful to Hamilton Fish, Ruth Baldwin, Taya Grobow, and Jonathan Schell, as well as Peggy Suttle and Katrina vanden Heuvel at The Nation magazine. Carl Bromley at Nation Books is a remarkably talented and brilliant editor, a fine writer and scholar in his own right, who helped shape and guide this book. In an age when editing seems to be a dying art, he upholds the highest standards of the craft. He loves books and ideas, and his insight and enthusiasm are infectious. It was a privilege to work with him. Michele Jacob, whom I have worked with before, handled publicity and book events with her usual efficiency. Patrick Lannan and Jo Chapman at the Lannan Foundation have been constant and steadfast supporters of my work. It was Patrick, who has done more than perhaps anyone in the country to nurture, promote, and protect great writing, who first gave me Sheldon Wolin’s Democracy Incorporated.

The Reverend Coleman Brown, my professor of religion at Colgate University and mentor, once again guided me through the writing. Coleman generously shared his profound wisdom, at once always humbling and always correct. His voice of compassion and deep insight into the human condition serve to temper the tone of my writing and pull me back from the edge of despair to remind me, and my readers, that good exists and is never as powerless as it appears.

John Timpane, a fellow lover of books, poetry, and theater, again edited the final manuscript. All my final manuscripts end up in his hands at my request. John, the greatest line and content editor in the business, is the Olympian authority who makes the last decisions on what is in or out, what should be changed and what amended. No writer could be in better hands, even if he has a hard time accepting my supremacy at Balderdash.

Chris Hebdon, a student at Berkeley, worked tirelessly on the book. He attended the seminar on positive psychology, did all the interviews and recordings, and wrote up the proceedings. The chapter on positive psychology is largely his work. Chris is a very talented young man whose conscience is as impressive as his intellect, which must make some of his professors very uncomfortable. My son Thomas, whose integrity is matched by a superb intellect, as well as a maturity and sensitivity that extend far beyond his years, worked during his Christmas vacation from Colgate University on the book in the Princeton University library. Robert Scheer and Zuade Kaufmann, who run the Web magazine Truthdig, where I write a weekly column, care deeply about maintaining the standards of great writing and reporting. I am fortunate to count them as friends and write for their site. Gerald Stern, Anne Marie Macari, Mae Sakharov, Rick McArthur, Richard Fenn, James Cone, Ralph Nader, Maria-Christina Keller, Pam Diamond, June Ballinger, Michael Goldstein, Irene Brown, Margaret Maurer, Sam Hynes, Tom Artin, Joe Sacco, Steve Kinzer, Charlie and Catherine Williams, Mark Kurlansky, Ann and Walter Pincus, Joe and Heidi Hough, Laila al-Arian, Michael Granzen, Karen Hernandez, Ray Close, Peter Scheer, Kasia Anderson, Robert J. Lifton, Lauren B. Davis, Robert Jensen, Cristina Nehring, Bernard Rapoport, Jean Stein, Larry Joseph, Wanda Liu (our patient and skillful Mandarin tutor), as well as Dorothea von Molke and Cliff Simms, who together run one of the finest bookstores in America, are part all of our cherished circle. Cliff was one of the most prescient critics of the manuscript and greatly improved its sharpness and focus. Thanks as well to Boris Rorer, Michael Levien, who recommended David Foster Wallace’s brilliant essay on the porn industry, and the staff at Bon Appetit, where I buy my daily baguette.

Lisa Bankoff of International Creative Management, as she has for all my books, negotiated contracts and eased the maddening minutiae of putting this book together. I am fortunate to be able to work with her.

My children, Thomas, Noëlle, and Konrad, are my greatest joy. After years in which I have witnessed too much violent death and suffering, they are the balms to my soul, the gentle reminders that trauma can be slowly healed through love and that redemption is possible.

Bibliography

ABC News. Living in the Shadows: Illiteracy in America. Feb. 25, 2008. Adorno, Theodor. The Culture Industry. London: Routledge, 1991. Andrejevic, Mark. Reality TV: The Work of Being Watched. Toronto: Rowman & Littlefield, 2004.

Arendt, Hannah. On Revolution. London: Penguin, 1963.

———. The Origins of Totalitarianism. New York: Harcourt, 1966.

Arnold, Matthew. Culture and Anarchy. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1994.

Bacevich, Andrew J. The Limits of Power: The End of American Exceptional-ism . New York: Metropolitan, 2008.

Bakan, Joel, writer. The Corporation: The Pathological Pursuit of Profit and Power. Canada: Big Picture Media Corporation/Zeitgeist Films, 2003.

Barstow, David. “One Man’s Military-Industrial-Media Complex.” New York Times (Nov. 29, 2008). http://www.nytimes.com/2008/11/30/washington/30general.html.

Benjamin, Walter. “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction.” Marxists.org. http://www.marxists.org/reference/subject/philosophy/works/ge/benjamin.htm.

Bernays, Edward. Propaganda. New York: Ig Publishing, 1928.

Bernstein, Paul. Workplace Democratization: Its Internal Dynamics. New Brunswick, N.J.: Transaction Books, 1976.

Berry, Wendell. The Unsettling of America. San Francisco: Sierra Club, 1977.

———. The Way of Ignorance. Washington, D.C.: Shoemaker & Hoard, 2005.

Boorstin, Daniel J. The Image: A Guide to Pseudo-Events in America. New York: Atheneum, 1961.

Bradbury, Ray. Fahrenheit 451. New York: Del Rey, 1996.

Bradley, James. Flags of Our Fathers. New York: Bantam, 2000.

Briggs, Asa, and Peter Burke. A Social History of the Media: From Gutenberg to the Internet. Cambridge: Polity, 2005.

“Canada’s Shame.” The National. Canadian Broadcasting Company. May 24, 2006.

Cantor, Paul A. “Pro Wrestling and the End of History.” The Weekly Standard 5:3 (Oct. 4, 1999): 17–22.

Chamberlin, Jamie. “Reaching ‘Flow’ to Optimize Work and Play.” American Psychological Association Monitor 29:7 (July 1998). http://www.apa.org/monitor/ju198/joy.html.

Cochran, Chris. “The Production of Cultural Difference: Paradigm Enforcement in Cultural Psychology.” Psychology at Berkeley 1 (Spring 2008): 62–73.

Colvin, Randall, and Jack Block. “Do Positive Illusions Foster Mental Health? An Examination of the Taylor and Brown Formulation.” Psychological Bulletin 116:. 1: 3–20.

Conrad, Joseph. Heart of Darkness. London: Penguin, 1902.

Cooper, Marc. The Last Honest Place in America: Paradise and Perdition in the New Las Vegas. New York: Nation, 2004.

Crane, Richard Teller. The Utility of all Kinds of Higher Schooling. Chicago: H. O. Shepard, 1909.

Csikszentmihály, Mihály. “Brain Channels Thinker of the Year Award: 2000: Mihály Csikszentmihály, ‘Flow Theory.’” Brain Channels. Accessed April 5, 2009. http://www.brainchannels.com/thinker/mihaly.html

D’Ambrosio, Antonino. A Heartbeat and a Guitar: Johnny Cash and the Making of Bitter Tears. New York: Nation Books, 2009.

De Botton, Alain. Status Anxiety. New York: Pantheon, 2004.

DeMott, Benjamin. Junk Politics. New York: Nation, 2003.

Deresiewicz, William. “The Disadvantages of an Elite Education.” The American Scholar (Summer 2008). http://www.theamericanscholar.org/the-disadvantages-of-an-elite-education.

———. “The End of Solitude.” The Chronicle of Higher Education 55:21 (Jan. 30, 2009). http://wwww.chronicle.com/free/v55/i21/21b00601.htm.

Diamond, Jared. Collapse. New York: Penguin, 2005.

Dines, Gail. “The White Man’s Burden: Gonzo Pornography and the Construction of Black Masculinity.” Yale Journal of Law and Feminism 18 (2006): 283–297.

“The Directors.” Adult Video News (August 2005): 54.

Donoghue, Frank. The Last Professors: The Corporate University and the Fate of the Humanities. New York: Fordham University Press, 2008.

Dworkin, Andrea. Pornogrpahy: Men Possessing Women. New York: Plume, 1979.

Eakin, Emily. “Greeting Big Brother with Open Arms.” New York Times (Jan . 17, 2004): B9+.

Eco, Umberto. Travels in Hyperreality. New York: Harcourt, 1983.

Eggers, Dave. A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius. New York: Vintage, 2000.

Ellul, Jacques. Propaganda: The Formation of Men’s Attitudes. New York: Vintage, 1965.

Fromm, Erich. Escape From Freedom. New York: Henry Holt, 1941.

Fulbright, William J. The Pentagon Propaganda Machine. New York: Vintage, 1985.

Füredi, Frank. Where Have All the Intellectuals Gone?: Confronting 21st Century Philistinism. London: Continuum, 2004.

Gabler, Neal. Life: The Movie: How Entertainment Conquered Reality. New York: Vintage, 1998.

Gag Factor. http://www.gagfactor.com/gagfactordotcom.html.

Gates, Jeff. Democracy At Risk: Rescuing Main Street from Wall Street. Cambridge: Perseus Publishing, 2000.

Golden, Daniel. The Price of Admission: How America’s Ruling Class Buys Its Way into Elite Colleges—and Who Gets Left Outside the Gates. New York: Random House, 2006.

González, Roberto. “Brave New Workplace: Cooperation, Control, and the New Industrial Relations.” In Nader, Laura, et al., Controlling Processes: Selected Essays, 1994-2005. The Kroeber Anthropological Society Papers, 92/93 (2005): 107–127.

Grossman, Vasily. Life and Fate. Trans. Robert Chandler. New York: Harper and Row, 1985.

Gyrna, Frank M., Jr. Quality Circles: A Team Approach to Problem Solving. New York: American Management Associations, 1981.

Hedges, Chris. American Fascists: The Christian Right and the War on America . New York: Free Press, 2006.

Held, Barbara S. The Loss of Happiness in Market Democracies. New Haven, Conn: Yale University Press, 2002.

———. “Tyranny of the Positive Attitude in America: Observation and Speculation.” Journal of Clinical Psychology 58: 965–991.

Herrick, Neal Q. Joint Management and Employee Participation: Labor and Management at the Crossroads. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1990.

Hoggart, Richard. The Uses of Literacy. New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers, 1998.

Huxley, Aldous. Brave New World. London: Triad Grafton, 1932.

Jensen, Robert. Getting Off: Pornography and the End of Masculinity. Cambridge, Mass.: South End, 2007.

Johnson, Chalmers. The Sorrows of Empire: Militarism, Secrecy, and the End of the Republic. New York: Henry Holt, 2004.

Johnston, David Cay. Free Lunch: How the Wealthiest Americans Enrich Themselves at Government Expense (And Stick You With the Bill). New York: Penguin, 2007.

Kamata, Satoshi. Japan in the Passing Lane: An Insider’s Account of Life in a Japanese Auto Factory. Tatsuru Akimoto, ed. and trans. New York: Pantheon, 1982.

Keller, Josh. “For Berkeley’s Sports Endowment, a Goal of $1 Billion.” The Chronicle of Higher Education, Jan. 23, 2009. http://chronicle.com/weekly/v55/i20/20a01301.htm.

Kindleberger, Charles P., and Robert Aliber. Manias, Panics, and Crashes. Hoboken, N.J.: John Wiley & Sons, 1978.

Kirp, David L. Shakespeare, Einstein, and the Bottom Line: The Marketing of Higher Education. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2003.

Korten, David C. When Corporations Rule the World. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler, 1995.

Lazarus, Richard S. “The Lazarus Manifesto for Positive Psychology and Psychology in General.” Psychological Inquiry, 14:2 (2003): 173–189.

Lippmann, Walter. Public Opinion. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1997.

Lubben, Shelley, and Jersey Jaxin. “Jersey Jaxin on Why She Quit Porn.” YouTube. Accessed Aug. 12, 2007. Part 1: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ACLK5ccKfM.

———. Part 2. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=U1NObcJV8r0&feature=related.

Lugo, Alejandro. 1990. “Cultural Production and Reproduction in Ciudad Juárez, Mexico: Tropes at Play among Maquiladora Workers.” Cultural Anthropology. 5:2 (1990): 173–196.

MacArthur, John R. You Can’t Be President: The Outrageous Barriers to Democracy in America. New York: Melville House, 2008.

MacKay, Charles. Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds. New York: BN Publishing, 2008.

Mellman, Seymour. The Permanent War Economy: American Capitalism in Decline. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1985.

Mills, C. Wright. The Power Elite. New York: Oxford University Press, 1956.

Nader, Laura. “Controlling Processes: Tracing the Dynamic Components of Power.” Mintz Lecture. Current Anthropology, 38:5 (1997): 711–737.

———. “Harmony Coerced is Freedom Denied.” The Chronicle of Higher Education, July 13, 2001: 613–616

———. Harmony Ideology. Palo Alto: Stanford University Press, 1990.

———. Personal communication with Chris Hedges. Feb. 27, 2009.

Nader, Laura, and Ugo Mattei. Plunder: When the Rule of Law Is Illegal. Hoboken, N.J.: Blackwell Publishers, 2008.

Newport, Cal. How to Win at College. New York: Broadway, 2005.

Nevin, Thomas R. Simone Weil: Portrait of a Self-Exiled Jew. Chapel Hill: University of South Carolina Press, 1991.

“The New Industrial Relations.” Business Week 2687 (May 11, 1981): 84–89.

Noble, David. America by Design. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1977.

Ofshe, R., and Margaret T. Singer. “Attacks on Peripheral versus Central Elements of Self and the Impact of Thought Reforming Techniques.” Cultic Studies. Journal, 3:1 (1986): 3–24.

Ortega y Gasset, José. The Revolt of the Masses. New York: W. W. Norton, 1932.

Orwell, George. 1984. New York: Signet, 1990.

———. The Collected Letters, Essays and Journalism of George Orwell. Vol, 4: In Front of Your Nose, 1945-1950. Eds. Sonia B. Orwell and Ian Angus. Boston: David R. Godine, 2000.

Ozaki, Robert S. Human Capitalism: The Japanese Enterprise System as World Model. Tokyo: Kodansha International, 1991.

Parker, Mike. Inside the Circle: A Union Guide to QWL. Boston: South End, 1985.

Peterson, C. “The Future of Optimism.” American Psychologist 55 (January 2000): 44–55.

Plato. The Republic. Translated by Robin Waterfield. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998.

Polanyi, Karl. The Great Transformation: The Political and Economic Origins of Our Time. Boston: Beacon Press, 1944.

Postman, Neil. Amusing Ourselves to Death: Public Discourse in the Age of Show Business. New York: Penguin, 1985.

Riesman, David. The Lonely Crowd: A Study of the Changing American Character . New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1950.

Rojek, Chris. Celebrity. London: Reaktion Books, 2001.

Roth, Joseph. The Emperor’s Tomb. New York: Overlook Press, 2002

Saul, John Ralston. The Unconscious Civilization. New York: Free Press, 1995.

———. Voltaire’s Bastards: The Dictatorship of Reason in the West. New York: Vintage, 1992.

Schmitt, Eric. “Pentagon Managers Find ‘Quality Time’ on a Brainstorming Retreat.” New York Times (Jan. 11, 1994): A7.

Schurmann, Reiner, ed. The Public Realm: Essays on Discursive Types in Political Philosophy. Albany: State University of New York Press, 1989.

Schwartz, Charles. Home page. http://socrates.berkeley.edu/~schwrtz.

Schwartz, Charles. “Good Morning, Regents.” UniversityProbe.org. http://universityprobe.org/2009/02/good-morning-regents.

Seligman, Martin. Authentic Happiness: Using the New Positive Psychology to Realize Your Potential for Lasting Fulfillment. New York: Free Press, 2002.

Simon, Scott, host. “Promoting Healthcare for the Porn Industry.” Weekend Edition. National Public Radio. Dec. 8, 2007. http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=17044239.

Snow, C. P. The Two Cultures. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998.

Soares, Joseph A. The Power of Privilege: Yale and America’s Elite Colleges. Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press, 2007.

Stoller, Robert J., and I. S. Levine. Coming Attractions: The Making of an X-Rated Video.. New Haven, Conn: Yale University Press, 1993.

Taylor, S. E. “Adjustment to threatening events: A theory of cognitive adaptation.” American Psychologist 38 (1983): 1161–1173.

Thompson, P. C. “U.S. Offered Unusual Class on Diversity.” New York Times (April 2, 1995): 34.

Ting, Charles. “The Dormitories at U.C. Berkeley.” In Nader, Laura, et al., Controlling Processes: Selected Essays, 1994-2005. The Kroeber Anthropological Society Papers 92/93 (2005): 197–229.

Wall, J. Andrew Carnegie. Pittsburgh: University Of Pittsburgh Press, 1989.

Wallace, David Foster. Consider the Lobster. New York: Back Bay, 2006.

Whyte, William H. The Organization Man. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1956.

Wittgenstein, Ludwig. Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1961.

Wolin, Sheldon S. Democracy Incorporated: Managed Democracy and the Specter of Inverted Totalitarianism. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2008.

#capitalism#culture#illusion#literacy#the spectacle#United States of America#us politics#tiktok#community building#practical anarchism#anarchist society#practical#mutual aid#grassroots#organization#anarchism#resistance#autonomy#revolution#anarchy#daily posts#communism#anti capitalist#anti capitalism#late stage capitalism#grass roots#anarchists#libraries#leftism#social issues

1 note

·

View note

Text

Holidays 11.23

Holidays

Arethusa Asteroid Day

Armed Forces Day (Lithuania)

Asian Corpsetwt Day [Every 23rd]

Big Help Day

Can You Find Your Old Rubik’s Cube and Still Work It Day

Chicory Day (French Republic)

Color Photos Day

Cutty Sark Day

Doctor Who Day

Do What the Heck You Want Day (Oklahoma)

Family Volunteer Day

Felt Day

Fibonacci Day

Flag Day (Niger)

Flipbook Day

Giorgoba (St. George's Day; Georgia)

Hadakambo Festival (Japan)

International Day of the Word

International Day to End Impunity

International Image Consultant Day

International Polyamory Day

Jukebox Day

Kinrō Kansha no Hi (Labor Thanksgiving Day; Japan)

Life Magazine Day

Madison Beer Day (New York)

Monkey Banquet (Thailand)

National Adoption Day

National Day to Combat Child & Youth Cancer (Brazil)

National Margaret Day

National Polyamory Day (Canada)

National Survivors of Suicide Loss Day

Nursing Support Workers Day (UK)

Old Clem’s Night (Blacksmith Festival)

One Cup of Tea Day (Japan)

Paranoia Day

Pencil Sharpener Day

Repudiation Day (Maryland)

Rudolf Maister Day (Slovenia)

Seng Kut Snem (Meghalaya, India)

TARDIS Day (Dr. Who)

Thankful For My Dog Day

Thespius' Day (Greek Mischief Ghost)

Traffic Police Day (Kazakhstan)

Virtual Reality Day

Wolfenoot

World Watercolor Day

Food & Drink Celebrations

Eat a Cranberry Day

National Bar Day

National Cashew Day

National Espresso Day

Independence & Related Days

Luxembourg (Separated from Netherlands; 1890)

St. Charlie (Declared; 2008) [unrecognized]

4th Saturday in November

Holodomor Remembrance Day (Ukraine) [4th Saturday]

International Aura Awareness Day [4th Saturday]

Salacious Saturday [4th Saturday of Each Month]

Sandwich Saturday [Every Saturday]

Sausage Saturday [4th Saturday of Each Month]

Six For Saturday [Every Saturday]

Spaghetti Saturday [Every Saturday]

Weekly Holidays beginning November 23 (3rd Full Week of November)

Sherlock Holmes Wekend (thru 11.24)

Festivals Beginning November 23, 2024

Burbank Winter Wine Walk (Burbank, California)

Cheese and Chocolate Weekend (Chisago City, Minnesota) [thru 11.24]

Cheese & Meat Festival (Portland, Oregon)

Festival of Trees (Methuen, Massachusetts) [thru 12.7]

Holiday Celebration and Winter Market (Rapid City, South Dakota)

Holiday Fineries at the Wineries (New Paltz, New York) [thru 11.24]

Holiday Light Parade (Baraboo, Wisconsin)

Jingle Bell Chocolate Tour (Jackson, New Hampshire) [thru 12.22]

Magnificent Mile Lights Festival (Chicago, Illinois)

Maine Harvest Festival (Bangor, Maine) [thru 11.24]

Monkey Buffet Festival (Lopburi, Thailand) [thru 11.24]

Mount Clemens Santa Parade (Mount Clemens, Michigan)

Natchitoches Christmas Festival (Natchitoches, Louisiana) [1.6.2025]

New York Craft Brewers Festival (Syracuse, New York)

Serbian Food Festival & Bazaar (Lenexa, Kansas)

Stockholm Christmas Market (Stockholm, Sweden) [12.23]

Tokyo Filmex (Tokyo, Japan) [thru 12.1]

Wi-Does Wine Walk (Eagle River, Wisconsin)

Yankeetown Art, Crafts & Seafood Festival (Yankeetown, Florida) [thru 11.24]

Feast Days

Alexander Nevsky (Repose, Russian Orthodox Church)

Amphilochius, Bishop of Iconium (Christian; Saint)

Chiron’s Day (Pagan)

Clement I, Pope (Roman Catholic Church, the Anglican Communion, and the Lutheran Church)

Columbanus (Christian; Saint)

Daniel (Christian; Saint)

D'Aranda (Positivist; Saint)

Derek Walcott (Writerism)

Erté (Artology)

Feast of Qawl (Speech; Baha'i)

Feast of the Wizard-Blacksmith (Saxon; Everyday Wicca)

Felicitas of Rome (a.k.a. Felicity; Christian; Saint)

Fountain of Riddles (Muppetism)

Frederick Nietzsche Day (Church of the SubGenius; Saint)

Fred Wah (Writerism)

General Debauchery Day (Pastafarian)

Gregory of Girgenti (Christian; Saint)

José Clemente Orozco (Artology)

Konstantin Korovin (Artology)

Marc Simont (Artology)

Mary Brewster Hazelton (Artology)

Miguel Agustín Pro, Blessed (One of Saints of the Cristero War; Roman Catholic Church and the Lutheran Church)

Niiname-Sai (Japanese Grain Festival)

Paulinus of Wales (Christian; Saint)

Shinjosai Festival (Rice Harvest; Celebrating Granddaughter Goddess of Solar Deity Amaterasu; Japan)

Stendahl (Writerism)

Trudo (a.k.a. Trond or Troll; Christian; Saint)

Wilfetrudis (a.k.a. Vulfetrude; Christian; Saint)

Woofenoot (Pastafarian)

Lucky & Unlucky Days

Lucky Day (Philippines) [64 of 71]

Tomobiki (友引 Japan) [Good luck all day, except at noon.]

Premieres

Against the Grain, by Bad Religion (Album; 1990)

Areopagitica, by John Milton (Pamphlet; 1644)

Another Brick in the Wall (Part 2), by Pink Floyd (Song; 1979)

Arthur Christmas (Animated Film; 2011)

The Artist (Film; 2011)

The Atrocity Exhibition, by J.G. Ballard (Novel; 1970)

Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, by Roald Dahl (Novel; UK 1964)

Chinese Democracy, by Guns ’N’ Roses (Album; 2008)

The Dance Contest (Fleischer Popeye Cartoon; 1934)

Devotion (Film; 2022)

Doctor Who (UK TV Series; 1963)

Doggystyle, by Snoop Doggy Dogg (Album; 1993)

The Expanse (TV Series; 2015)

The Exterminator (Terrytoons Cartoon; 1945)

The Favourite (Film; 2018)

Fish and Chips (Chilly Willy Cartoon; 1962)

Flying Colours, by C.S. Forester (Novel; 1938)

For Those About To Rock We Salute You, by AC/DC (Album; 1981)

G.I. Blues (Film; 1960) [Elvis Presley #5]

Glass Onion (Film; 2022)

Hugo (Film; 2011)

Inner Workings (Disney Cartoon; 2016)

It’s Only a Flesh Wound or Better Lead Than Dead (Rocky & Bullwinkle Cartoon, S6, Ep. 322; 1964)

Just Friends (Film; 2005)

The Lonesome Stranger (MGM Cartoon; 1940)

Love in a Cold Climate, by Nancy Mitford (Novel; 1949)

Moana (Animated Disney Film; 2016)

Mouse Trouble (Tom & Jerry Cartoon; 1944)

The Muppets (Film; 2011)

Mrs. Parker and the Vicious Circle (Film; 1994)

My Sweet Lord, by George Harrison (Song; 1970)

No Smoking (Disney Cartoon; 1951)

Pretty Peaches (Adult Film; 1978)

Of Mice and Men by John Steinbeck (Novel; 1937)

Pride & Prejudice (Film; 2015)

Scrooged (Film; 1988)

Small Fry (Pixar Cartoon; 2011)

Strange World (Animated Disney Film; 2022)

Tampopo (Film; 2016)

Tea For The Tillerman, by Cat Stevens (Album; 1970)

The Ten Commandments (Film; 1923)

Terms of Endearment (Film; 1983)

The Three Musketeers (Hanna-Barbera Animated TV Special; 1973)

Tito’s Guitar (Color Rhapsody Cartoon; 1942)

Wednesday (TV Series; 2022)

The Worrying’ of the Green or The Look of the Irish (Rocky & Bullwinkle Cartoon, S6, Ep. 321; 1964)

Today’s Name Days

Clemens, Columban, Detlef (Austria)

Aleko, Aleksandar, Aleksandra (Bulgaria)

Klement, Kolumban, Lukrecija (Croatia)

Klement (Czech Republic)

Clemens (Denmark)

Kleement, Leemet, Leemo (Estonia)

Ismo (Finland)

Clément (France)

Clemens, Columbia, Detlef, Salvator (Germany)

Amfilohios, Elenos (Greece)

Kelemen, Klementina (Hungary)

Clemente, Colombano (Italy)

Zigfrīda, Zigrīda, Zigrids (Latvia)

Adelė, Doviltas, Klemensas, Liubartė (Lithuania)

Klaus, Klement (Norway)

Adela, Erast, Felicyta, Klemens, Klementyn, Orestes, Przedwoj (Poland)

Antonie (Romania)

Klement (Slovakia)

Clemente, Lucrecia (Spain)

Klemens (Sweden)

Augusta, Augustina (Ukraine)

Clem, Clemence, Clement, Clementina, Clementine, Crecia, Lucrecia (USA)

Today is Also…

Day of Year: Day 328 of 2024; 38 days remaining in the year

ISO: Day 6 of Week 47 of 2024

Celtic Tree Calendar: Hagal (Hailstone) [Day 28 of 28]

Chinese: Month 10 (Yi-Hai), Day 23 (Xin-Mao)

Chinese Year of the: Dragon 4722 (until January 29, 2025) [Wu-Chen]

Hebrew: 22 Heshvan 5785

Islamic: 21 Jumada I 1446

J Cal: 28 Wood; Sevenday [28 of 30]

Julian: 10 November 2024

Moon: 43%: Waning Crescent

Positivist: 20 Frederic (12th Month) [Campomanes / Turgot]

Runic Half Month: Is (Stasis) [Day 2 of 15]

Season: Autumn or Fall (Day 62 of 90)

Week: 3rd Full Week of November

Zodiac: Sagittarius (Day 2 of 30)

1 note

·

View note

Text

Kitty's Gone A-Milking #675

Songs of Ireland and more on the Irish & Celtic Music Podcast #675 . Subscribe now!

Tradify, High Octane, Sassenach, The Drowsy Lads, Altan, Brobdingnagian Bards, Louise Bichan, Hayley Griffiths, Toby Bresnahan, Natalie Padilla, Philippe Barnes, Tom Phelan, Jigjam, Lúnasa, River Driver

GET CELTIC MUSIC NEWS IN YOUR INBOX

The Celtic Music Magazine is a quick and easy way to plug yourself into more great Celtic culture. Enjoy seven weekly news items for Celtic music and culture online. Subscribe now and get 34 Celtic MP3s for Free.

VOTE IN THE CELTIC TOP 20 FOR 2024

This is our way of finding the best songs and artists each year. You can vote for as many songs and tunes that inspire you in each episode. Your vote helps me create next year's Best Celtic music of 2024 episode. You have just three weeks to vote this year. Vote Now!

You can follow our playlist on Spotify to listen to those top voted tracks as they are added every 2 - 3 weeks. It also makes it easier for you to add these artists to your own playlists. You can also check out our Irish & Celtic Music Videos.

THIS WEEK IN CELTIC MUSIC

0:15 - Tradify "Molly Malone & Kitty's Gone a - Milking" from Take Flight

3:35 - WELCOME

7:12 - High Octane "Jurassic Reels" from High Octane

13:14 - Sassenach "A Chuachag Nam Beann/The Cuckoo of the Mountain" from Passages

16:30 - The Drowsy Lads "Up and About in the Morning (Jigs)" from Wide Awake

21:08 - Altan “Gabhaim Molta Bríde" from Donegal

25:32 - FEEDBACK

29:48 - Brobdingnagian Bards "Paddy McCollough" from Songs of Ireland

33:13 - Louise Bichan "Margaret's Walk to the Pier" from Out of My Own Light

39:36 - Hayley Griffiths "Loch Lomond" from Far from Here

43:45 - Toby Bresnahan "Crabs in the Skillet - Ten Penny Bit - Colerain Jig" from All In Good time

48:24 - THANKS

50:37 - Natalie Padilla "Immortal, Invisible" from Paths and Places

54:25 - Philippe Barnes and Tom Phelan "Midnight Accountant" from The Clearwater Sessions

58:10 - Jigjam "Bluebird" from Phoenix

1:02:23 - Lúnasa "Man from Moyasta" from Live in Kyoto

1:06:05 - CLOSING

1:06:53 - River Driver "Home" from Flanagan's Shenanigans! Live at The Celt

1:10:30 - CREDITS

The Irish & Celtic Music Podcast was produced by Marc Gunn, The Celtfather and our Patrons on Patreon. The show was edited by Mitchell Petersen with Graphics by Miranda Nelson Designs. Visit our website to follow the show. You’ll find links to all of the artists played in this episode.

Todd Wiley is the editor of the Celtic Music Magazine. Subscribe to get 34 Celtic MP3s for Free. Plus, you’ll get 7 weekly news items about what’s happening with Celtic music and culture online. Best of all, you will connect with your Celtic heritage.

Please tell one friend about this podcast. Word of mouth is the absolute best way to support any creative endeavor.

Finally, remember. Reduce, reuse, recycle, and think about how you can make a positive impact on your environment.

Promote Celtic culture through music at http://celticmusicpodcast.com/.

WELCOME THE IRISH & CELTIC MUSIC PODCAST

* Helping you celebrate Celtic culture through music. I am Marc Gunn. I’m a Celtic musician and podcaster. This podcast is for fans of Celtic music of all shapes and sizes. Not necessarily from Ireland or Scotland, but from around the globe. Because there is much great Celtic music from around the world.

We are here to build a diverse Celtic community and help the incredible artists who so generously share their music with you.

If you hear music you love, please email artists to let them know you heard them on the Irish and Celtic Music Podcast. Remember. Musicians depend on your generosity to keep making music. So please find a way to support them. Buy a CD, Album Pin, Shirt, Digital Download, or join their communities on Patreon.

You can find a link to all of the artists in the shownotes, along with show times, when you visit our website at celticmusicpodcast.com.

Today’s show is sponsored by Richard Trest of the Middle Tennessee Highland Games & Celtic Festival on Sept 7 - 8, 2024 at Sanders Ferry Park, Hendersonville. You’ll enjoy music from Tuatha Dea, Kris Colt, The Secret Commonwealth, The Devil’s Brigade, The Sternwheelers, Doon the Brae, Nosey Flynn, and Colin Grant - Adams. Plus, there’s a piping competition, Irish step dancing, highland dance competition, ceilidh dancing and so much more. Join Richard just outside of Nashville Sept 7 - 8. And find more details at www.midtenngames.com

Are you a Celtic artist? Do you know one? We are looking to feature Celtic art in 2025. Please send your designs to us. You will be financially compensated if your art is used.

Next week’s show will officially drop Wednesday evening at 8 PM ET on Patreon. If you want to join other Celts to talk about this week’s show.

If you are a Celtic musician or in a Celtic band, then please submit your band to be played on the podcast. You don’t have to send in music or an EPK. You will get a free eBook called Celtic Musicians Guide to Digital Music and learn how to follow the podcast. It’s 100% free. Just email Email follow@bestcelticmusic and of course, listeners can learn how to subscribe to the podcast and get a free music - only episode.

Listen to Celtic Christmas Music in a podcast and find out how you can support the show.

THANK YOU PATRONS OF THE PODCAST!

You are amazing. It is because of your generosity that you get to hear so much great Celtic music each and every week.

Your kindness pays for our engineer, graphic designer, Celtic Music Magazine editor, promotion of the podcast, and allows me to buy the music I play here. It also pays for my time creating the show each and every week.

As a patron, you get ad - free and music - only episodes before regular listeners, vote in the Celtic Top 20, stand - alone stories, you get a private feed to listen to the show or you can listen through the Patreon app. All that for as little as $1 per episode.

A special thanks to our Celtic Legends: Bruce, Brian McReynolds, Marti Meyers, Brenda, Alan Schindler, Karen DM Harris, Emma Bartholomew, Dan mcDade, Miranda Nelson, Nancie Barnett, Kevin Long, Gary R Hook, Lynda MacNeil, Kelly Garrod, Annie Lorkowski, Shawn Cali

HERE IS YOUR THREE STEP PLAN TO SUPPORT THE PODCAST

Go to our Patreon page.

Decide how much you want to pledge every week, $1, $5, $25. Make sure to cap how much you want to spend per month.

Keep listening to the Irish & Celtic Music Podcast to celebrate Celtic culture through music.

You can become a generous Patron of the Podcast on Patreon at SongHenge.com.

TRAVEL WITH CELTIC INVASION VACATIONS

Every year, I take a small group of Celtic music fans on the relaxing adventure of a lifetime. We don't see everything. Instead, we stay in one area. We get to know the region through its culture, history, and legends. You can join us with an auditory and visual adventure through podcasts and videos. Learn more about the invasion at http://celticinvasion.com/

#celticmusic #irishmusic #celticmusicpodcast

I WANT YOUR FEEDBACK

What are you doing today while listening to the podcast? Please email me. I’d love to see a picture of what you're doing while listening or of a band that you saw recently.

Email me at follow@bestcelticmusic.

Jason Denen emailed this week: "Marc, I can't support the latest changes to Patreon, do you have a KoFi or PayPal I can use to send you some money."

Make a donation.

Éirinn O'Coscraigh (pron. pronounced Erin O - Cosgrove) emailed: "Dearest Celtfather and purveyor of fine Irish and Celtic music.