#United Nations Office on Genocide Prevention and the Responsibility to Protect

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Objectives of the 2nd International Day for Countering Hate Speech.

This high-level event is co-organized by the Permanent Mission of the Kingdom of Morocco to the United Nations and the United Nations Office on Genocide Prevention and the Responsibility to Protect, that is also the United Nations Focal Point on Hate Speech. Its objectives include to: Commemorate the 2nd Anniversary of the International Day on Countering Hate Speech, and bringing attention to the importance of tackling hate speech in all its forms and manifestations. Showcasing good practices and examples of efforts to combat hate speech from UN, Member States, regional organizations, civil society and other actors with the aim to support knowledge sharing and exchange on share lessons learnt. It is also aimed to take stock of and highlight recommendations for additional efforts that can enable holistically addressing and countering hate speech, both online and offline.

#United Nations Office on Genocide Prevention and the Responsibility to Protect#united nations field entities#united nations specialized Agencies#harmonious coexistence#hate spreading online#un office of the special adviser on the prevention of genocide (osapg)#International Day for Countering Hate Speech#18 june#United Nations Focal Point on Hate Speech

0 notes

Text

PALESTINIAN GENOCIDE: WAR CRIMES MASTER POST

The goal of this post is to keep track of all the war crimes as recognized by the UN's Office on Genocide Prevention and the Responsibility to Protect committed by Israeli authority and military against the Palestinian, Syrian and Lebanese people, and which remain unpunished by international authorities.

The ICC is not doing its job. It has failed its mission. It's up to us to push for Israel to be held accountable.

Feel free to comment, I'll feel free to delete the Zionist propaganda. I can't help it, I'm allergic to Nazis. Don't ask for "reliable" western media sources either; you can just open your eyes. I promise you it's better to see things as they are.

Everything under the cut is the material present on the UN's Office on Genocide Prevention and the Responsibility to Protect website as of 12/11th. Just go check it yourself if you need. Crimes in bold and red are those identified as committed. I'd love to keep tracks of numbers but... they are overwhelming. I can't. I don't think anyone can.

Paragraphs 2.c, 2.d, 2.e, 2.f and 3 are repeats of the previous but applicable to "armed conflicts not of an international character" and details to take into account in such cases. For the sake of brevity, they will be skipped and instances applicable will be reported in the previous instances of said crimes.

If you find other crimes (or victims) that need to be accounted for, please send a screenshot or a link to the source material along with the paragraph number (X.Y.Z.) and I'll be happy to oblige. You can also just bring up cases applying to a certain paragraph the same way; I don't mind a comment section filled with proof.

This post will be reblogged every 12 hours and updated when I'm able to do so.

FROM THE RIVER TO THE SEA PALESTINE WILL BE FREE.

Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court

Article 8 War Crimes

1. The Court shall have jurisdiction in respect of war crimes in particular when committed as part of a plan or policy or as part of a large-scale commission of such crimes.

2. For the purpose of this Statute, ‘war crimes’ means:

2.a. Grave breaches of the Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949, namely, any of the following acts against persons or property protected under the provisions of the relevant Geneva Convention:

2.a.i. Wilful killing;

2.a.ii. Torture or inhuman treatment, including biological experiments;

2.a.iii. Wilfully causing great suffering, or serious injury to body or health;

2.a.iv. Extensive destruction and appropriation of property, not justified by military necessity and carried out unlawfully and wantonly;

2.a.v. Compelling a prisoner of war or other protected person to serve in the forces of a hostile Power;

2.a.vi. Wilfully depriving a prisoner of war or other protected person of the rights of fair and regular trial;

2.a.vii. Unlawful deportation or transfer or unlawful confinement;

2.a.viii. Taking of hostages.

2.b. Other serious violations of the laws and customs applicable in international armed conflict, within the established framework of international law, namely, any of the following acts:

2.b.i. Intentionally directing attacks against the civilian population as such or against individual civilians not taking direct part in hostilities;

2.b.ii. Intentionally directing attacks against civilian objects, that is, objects which are not military objectives;

2.b.iii. Intentionally directing attacks against personnel, installations, material, units or vehicles involved in a humanitarian assistance or peacekeeping mission in accordance with the Charter of the United Nations, as long as they are entitled to the protection given to civilians or civilian objects under the international law of armed conflict;

2.b.iv. Intentionally launching an attack in the knowledge that such attack will cause incidental loss of life or injury to civilians or damage to civilian objects or widespread, long-term and severe damage to the natural environment which would be clearly excessive in relation to the concrete and direct overall military advantage anticipated;

2.b.v. Attacking or bombarding, by whatever means, towns, villages, dwellings or buildings which are undefended and which are not military objectives;

2.b.vi. Killing or wounding a combatant who, having laid down his arms or having no longer means of defence, has surrendered at discretion;

2.b.vii. Making improper use of a flag of truce, of the flag or of the military insignia and uniform of the enemy or of the United Nations, as well as of the distinctive emblems of the Geneva Conventions, resulting in death or serious personal injury;

2.b.viii. The transfer, directly or indirectly, by the Occupying Power of parts of its own civilian population into the territory it occupies, or the deportation or transfer of all or parts of the population of the occupied territory within or outside this territory;

2.b.ix. Intentionally directing attacks against buildings dedicated to religion, education, art, science or charitable purposes, historic monuments, hospitals and places where the sick and wounded are collected, provided they are not military objectives;

2.b.x. Subjecting persons who are in the power of an adverse party to physical mutilation or to medical or scientific experiments of any kind which are neither justified by the medical, dental or hospital treatment of the person concerned nor carried out in his or her interest, and which cause death to or seriously endanger the health of such person or persons;

2.b.xi. Killing or wounding treacherously individuals belonging to the hostile nation or army;

2.b.xii. Declaring that no quarter will be given;

2.b.xiii. Destroying or seizing the enemy's property unless such destruction or seizure be imperatively demanded by the necessities of war;

2.b.xiv. Declaring abolished, suspended or inadmissible in a court of law the rights and actions of the nationals of the hostile party;

2.b.xv. Compelling the nationals of the hostile party to take part in the operations of war directed against their own country, even if they were in the belligerent's service before the commencement of the war;

2.b.xvi. Pillaging a town or place, even when taken by assault;

2.b.xvii. Employing poison or poisoned weapons;

2.b.xviii. Employing asphyxiating, poisonous or other gases, and all analogous liquids, materials or devices;

2.b.xix. Employing bullets which expand or flatten easily in the human body, such as bullets with a hard envelope which does not entirely cover the core or is pierced with incisions;

2.b.xx. Employing weapons, projectiles and material and methods of warfare which are of a nature to cause superfluous injury or unnecessary suffering or which are inherently indiscriminate in violation of the international law of armed conflict, provided that such weapons, projectiles and material and methods of warfare are the subject of a comprehensive prohibition and are included in an annex to this Statute, by an amendment in accordance with the relevant provisions set forth in articles 121 and 123;

2.b.xxi. Committing outrages upon personal dignity, in particular humiliating and degrading treatment;

2.b.xxii. Committing rape, sexual slavery, enforced prostitution, forced pregnancy, as defined in article 7, paragraph 2 (f), enforced sterilization, or any other form of sexual violence also constituting a grave breach of the Geneva Conventions;

2.b.xxiii. Utilizing the presence of a civilian or other protected person to render certain points, areas or military forces immune from military operations;

2.b.xxiv. Intentionally directing attacks against buildings, material, medical units and transport, and personnel using the distinctive emblems of the Geneva Conventions in conformity with international law;

2.b.xxv. Intentionally using starvation of civilians as a method of warfare by depriving them of objects indispensable to their survival, including wilfully impeding relief supplies as provided for under the Geneva Conventions;

2.b.xxvi. Conscripting or enlisting children under the age of fifteen years into the national armed forces or using them to participate actively in hostilities.

#Palestine#Israel#United Nations#FREE PALESTINE#War Crimes#Palestinian Genocide#Israel is a terrorist state

322 notes

·

View notes

Text

“If you were Masalit, we decided that we don’t want to leave any alive, not even the children.” This explicit warning, recounted by a survivor to Human Rights Watch, by a militiaman of the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) and its allies last June is emblematic of the ongoing genocidal atrocities in Darfur. Rarely does the world bear witness to such open confessions of genocidal intent.

The RSF is the successor to the janjaweed militia, which carried out a genocide in Darfur just 20 years ago against non-Arab ethnic groups such as the Fur, Masalit, and Zaghawa. At the time, a mass movement emerged in the United States—led by the Save Darfur coalition, which comprised nearly 200 organizations—mobilizing worldwide protests and bringing out prominent celebrities, including then-Sen. Barack Obama and George Clooney, and demonstrators in the hundreds of thousands.

A powerful U.N. Security Council arms embargo, sanctions regime, and referral to the International Criminal Court ensued, resulting in the first—and only—arrest warrant for genocide against Sudanese leader Omar al-Bashir, while an eventual joint U.N.-African Union peacekeeping force was dispatched to the region; it was later withdrawn in 2021.

This time, the world is nowhere to be found. The U.N. Security Council has passed only a single resolution after nearly a year into the conflict, merely calling for a temporary cessation of hostilities during the month of Ramadan—a step that should have been taken on day one.

Many RSF commanders today are former janjaweed leaders themselves, including the head of the RSF, Mohamed Hamdan “Hemeti” Dagalo. The RSF largely recruits on an ethnic basis from Arab communities, whose militiamen have continued to perpetrate systematic massacres and sexual violence against non-Arab communities on the basis of their ethnicity.

The current genocide unfolding in Darfur is crowded out by coverage of Gaza, Ukraine, and the broader war in Sudan, portrayed as an internal armed conflict between the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) and the RSF. But the ethnically targeted violence in Darfur must be distinguished from this broader conflict, demanding an immediate response in the form of civilian protection.

This is all happening in the context of a shamefully overlooked humanitarian catastrophe. The estimated death toll currently is as many as 150,000; nearly 9 million Sudanese have been forcibly displaced; and 25 million people—half of Sudan’s population—are in need of humanitarian aid. In the worst scenarios, 2.5 million people are projected to die by famine, while 18 million face acute food insecurity, and nearly 4 million children are acutely malnourished. It is a man-made disaster of inconceivable proportions.

In recent weeks, the RSF has razed dozens of communities to the ground at a shocking pace around El Fasher, the capital of North Darfur. The city’s population of up to 2.8 million, including 750,000 children, is already on the brink of famine with nowhere to go. The long-feared attack on El Fasher is now well underway, and the window to intervene to protect civilians is closing.

The legal community is already coalescing around a consensus that the RSF campaign in West Darfur constitutes genocide. As human rights lawyers specializing in atrocity prevention, we chaired the first international inquiry into the genocide with dozens of jurists and scholars around the world, concluding that the RSF is responsible for committing genocide in Darfur.

Our panel of experts included founding prosecutors of the international criminal tribunals and presidents of the International Association of Genocide Scholars. The United Nations Office on Genocide Prevention and the Responsibility to Protect echoed our independent finding, which is further corroborated by a substantial report by Human Rights Watch on the RSF’s ethnically targeted campaign of genocidal violence.

Our inquiry also concluded that the RSF is receiving direct military, financial, and diplomatic support from the United Arab Emirates. This finding is also backed by the U.N. Panel of Experts on Sudan, who found credible evidence of the UAE providing heavy weaponry to the RSF, as corroborated by further investigative reporting. In December 2023, a group of U.S. members of Congress sent a letter to the Emirati foreign minister urging an end to the UAE’s provision of military support to the RSF. This May, legislation was introduced to stop U.S. arms exports to the UAE until it ceases its support to the RSF.

The RSF’s offensive across Darfur mirrors the genocidal attacks of the early 2000s, only with more advanced weaponry. The RSF and its militias have methodically massacred and committed sexual violence against members of the Masalit community after interrogating and screening their victims’ ethnicity, singling out Masalit members to be raped or executed at close range. The RSF’s campaign should be described accurately and confronted as such. History is repeating itself as the world is turning away.

Major powers have not only failed to take decisive action on Sudan but continue to fail to even issue decisive statements, instead parroting old, empty platitudes for all parties to cease hostilities without even directly naming the genocidaires and their sponsors. This diplomatic posturing has not changed since the first weeks of the war in April 2023, despite mounting evidence of escalating genocide in Darfur—perpetrated by the RSF.

The international community is repeating the exact same fatal mistakes of the early 2000s by prioritizing a sham political process in Saudi Arabia, entirely removed from an ongoing genocide. Vague calls on all parties to negotiate is not only a pretense but a form of complicity when it serves as cover for the RSF, allowing its fighters to perpetrate the impending massacres against vulnerable civilians in El Fasher with impunity.

As the RSF besieges and attacks El Fasher, cutting off water and critical supplies, the world must prepare for the worst-case scenario. The SAF cannot be trusted to protect civilians, for it once created, trained, and equipped the RSF to commit atrocities against the non-Arab populations in Darfur. But even if the SAF were willing to protect them today, it is unable to protect its military bases, let alone civilians.

When the SAF abandoned its posts in West Darfur, the RSF went on a killing spree, systematically murdering men and boys and committing rape and other forms of sexual violence against women and girls based on their identity. On this empirical basis, we know how the same pattern will repeat itself in El Fasher.

The only way to halt the RSF’s impending genocide in El Fasher is by imposing immediate costs on the perpetrators. The continuing impunity sends a clear message that the international community will simply stand by.

Last month, the U.S. government rightfully urged the RSF to retreat from El Fasher or “face further consequences” and called out the “external backers of the belligerents [who] continue the flow of weapons into the country.”

If the U.S. government is to be true to its word, these consequences and external backers must now be specifically articulated. The United States has the most influence to exercise the leverage and pressure needed to immediately stem the violence. Washington has the power to stop this genocide but is failing to do so.

First, given the risk of imminent massacres in El Fasher, U.S. President Joe Biden should openly call on Hemeti to call off this attack—or simply phone Washington’s close ally Emirati President Sheikh Mohammed bin Zayed Al Nahyan to urge him to exert pressure on Hemeti to withdraw his forces from El Fasher. The United States should threaten Hemeti with immediate consequences for imminent crimes against humanity and genocide in El Fasher, including sanctions and arrest warrants to stamp the RSF leaders with pariah status internationally. This time, it should not be an empty threat; actions must follow.

Second, the United States should work with regional partners to build support for an AU-led civilian protection mechanism in El Fasher to facilitate humanitarian aid routes and safe passage. Whereas Chad was reachable by foot from El Geneina in West Darfur, civilians in El Fasher are trapped with nowhere to go.

Third, Biden should publicly call out the UAE for its support of the RSF. Unless the UAE ceases its support, the RSF will continue to commit atrocities targeting defenseless communities.

Fourth, the U.S. government should call an emergency open debate on El Fasher at the U.N. Security Council and pass a resolution for a cease-fire, civilian protection, and immediate consequences on all actors openly defying the arms embargo and fueling this genocide, including the UAE.

Fifth, the United States and all 152 other parties to the Genocide Convention should fulfill their obligations to prevent genocide by, at a minimum, imposing costs and sanctions on all of the RSF’s enablers, including all companies owned by or linked to the RSF, and all sponsors of this conflict more broadly.

Finally, the humanitarian aid pledges made by countries at the Paris conference for Sudan in April must be immediately implemented to prevent wide-scale famine, as the lean season sets in. Only 16 percent of the overall funding required for the bare minimum U.N. humanitarian response plan has been received so far. All humanitarian aid should be carefully distributed as much as possible to local organizations, including volunteer emergency response rooms doing the front-line work.

At present, there is scarcely any media coverage of Darfur. The same atrocities that sparked a mass movement just 20 years ago are being completely overlooked today. There is no reason why the same coalition should not come together once again today, in a landscape with greater potential to mobilize broader support through social media.

While we fear that the window to intervene for the people of Darfur is closing, we are writing this as an urgent appeal. Let no one say they did not know.

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

american liberals act like all leftists are tankies who deny atrocities in nations outside the united states. so of course they want to accuse us of misusing the term genocide.

there's no point in bringing up hypothetical concerns about israelis being deported when literally RIGHT NOW, millions of palestinians are forcibly deported under the threat of bombings. israeli officials are outright saying this is nakba 2023.

this is not worth writing an actual post about so i'll just paste some quotes from wikipedia. list of ~terminally online leftists~ who ~bastardize~ the word genocide:

Additionally, dozens of Holocaust survivors, along with hundreds of descendants of Holocaust survivors and victims, accused Israel of "genocide" for the deaths of more than 2,000 Palestinians in Gaza during the 2014 Gaza War.[38]

IfNotNow co-founder and B'Tselem USA director Simone Zimmerman criticized them as exhibiting "genocidal animus towards Palestinians — emboldened and unfiltered".[39][40]

Israeli New Historian Ilan Pappé has argued that genocide "is the only appropriate way to describe what the Israeli army is doing in the Gaza Strip"

On 15 October, TWAILR published a statement signed by over 800 legal scholars expressing "alarm about the possibility of the crime of genocide being perpetrated by Israeli forces against Palestinians in the Gaza Strip" and calling on UN bodies, including the UN Office on Genocide Prevention and the Responsibility to Protect, as well as the Office of the Prosecutor of the International Criminal Court to "immediately intervene, to carry out the necessary investigations, and invoke the necessary warning procedures to protect the Palestinian population from genocide."[48][49][50]

there's more just under the 2023 subheading.

not good enough?

how's that for throwing around the term genocide?

if you actually bothered to watch it, shaun's video was about debunking american apologia over the hiroshima and nagasaki bombings. specifically the claim that it was tragic but necessary. it wasn't about defending imperial japan. it was actually critical of its militarist supreme council and how it refused to surrender even after hiroshima was bombed.

apparently that falls under genocide enabling. but pretending that biden isn't enabling israel's genocide of palestinians doesn't count?

#self admitted neoliberal warhawk mariacallous#the american people are not intellectual to put it mildly#how many times do palestinians have to say that freeing palestine =/= forcibly deporting israeli people#it's racist and baseless fearmongering. just like the pushback against land back movement. 'the natives will kill us and make us leave!'#also not sprinkledsalt having no terfs in their bio while sharing an article from unherd#you know. the right wing news site whose columnists include julie bindel meghan murphy and kathleen stock. all gendercrits#palestine#free gaza#gaza#islamophobia#racism#gaza genocide#nakba#free palestine#world war 2#japan#imperialism#hiroshima and nagasaki#breadtube#blocklist

39 notes

·

View notes

Note

The Jews who argue against the word “genocide” do not do so because they support what is happening; they do so because they are arguing that what is happening is better described by the term “ethnic cleansing,” which is also a horrifically bad and inexcusable thing. It just also doesn’t have the antisemitic connotation here.

Hey, need to point out using Ethnic Cleansing (which i only saw used by slightly less radical left) is just as bad and inaccurate to use as Genocide- Jews have experienced Ethnic Cleansing and to label this war as such disregards the actual ethnic cleansing Jews experienced for centuries- most recently SWANA Jews! And I would argue Ethiopian Jews too. Individuals willingly and temporarily leaving their home because it is a war zone (due to a war their leadership systems!) is not ethnic cleansing. We can look to what is happening to Armenians, and Afghans in Pakistan- that is ethnic cleansing.

I really need people to brush up not only on their dictionary terms but on the legal definitions that help determine something. Definitions and the correct usage of them matter! Languages matters- when we use definitions wrongly we water them down.

This is why we have people screaming genocide at something that isn’t one! Because their definition of genocide has been watered down- because every war is suddenly a genocide and every bad person I disagree with is a Nazi.. You get my drift. I’m very sensitive to correct usage of words and definitions.

I absolutely understand this perspective and I refrain from using either term personally with regard to this conflict.

I respect your sensitivity, which is one of many reasons I urge people to try to understand the impact of these words on the Jewish community.

That said, I am sensitive also to the fact that there are dictionary definitions of things and legal definitions of things and scholarly definitions of things. I try to keep in mind that everyone is approaching this conflict from their own cultural context so I am not as intense personally about correcting people's usage of these terms, simply because I'm not expert enough to determine which definition is "best." I think legal definitions should definitely always be used in the context of legal discussions, but I don't know if the legal definition is best in a sociological context.

I want to be clear: I'm not disagreeing with you. I'm just respecting my own limitations on this subject matter.

Rest assured, we agree on the main point here: It is important to be specific and accurate in the usage of terms. We cannot allow emotions running high to justify the watering down of such serious terms.

People of all identities affected by this conflict should approach discussions of terms in the same way they approach everything else about this conflict: with good faith, an open heart, and a goal of peace.

I respect that you also disagree with the use of the term ethnic cleansing. However, I personally do not agree that it is "as bad." This is not me trying to tell you that you're wrong. I just think this particular discussion point has a lot of equally valid takes. Your take is absolutely valid. But allow me to explain my take on the situation, which I consider to be equally valid:

I think there is a lot more wiggle room in the term "ethnic cleansing" than there is in the term "genocide." When I use the term ethnic cleansing, I am referring to the United Nations Office on Genocide Prevention and the Responsibility to Protect.

The key takeaways I have from the United Nations here is that ethnic cleansing is not actually a crime under international law. The two very loose definitions offered here are:

… rendering an area ethnically homogeneous by using force or intimidation to remove persons of given groups from the area.

a purposeful policy designed by one ethnic or religious group to remove by violent and terror-inspiring means the civilian population of another ethnic or religious group from certain geographic areas.”

I consider Palestinians to be a an ethnic group. I know some critics do not, but I disagree with those people. So if you do not agree with me on that, I doubt we will agree on the specifics that follow. I think recognizing Palestinian identity is vital to fostering a peaceful future for all currently residing in the Levant. However, I know that there are also politics and political realities in Israel between those who call themselves Arab-Israelies vs. Palestinians. I do my best to stay informed about topics, but this is too fraught for me to parse with any authority. I believe in Palestinian ethnic identity because of several reasons I won't elaborate on here, but can elaborate on upon request.

I am not particularly swayed by the first bullet point. I do not believe that Israel is trying to render Palestine as ethnically homogeneous, even though they are using force on the area.

The second bullet point has merit to me. I do not believe all Jews or all Israelis wish to eradicate and remove Palestinians from the Levant, so I do not consider Israelis in general or Jews in general responsible for the cleansing. Furthermore, even though I am personally a pacifist, I am also pragmatic. I believe there are much less violent ways to eradicate Hamas than the heavy bombing currently taking place. I also know Hamas has been firing rockets into Israeli civilian areas for quite a long time and Israel has every right to treat Hamas like the hostile, terrorist organization it is.

But I do hold Netanyahu and the Likud party responsible for their affect on Palestinian civilians. I was disgusted when Netanyahu justified his violent actions by invoking Amalek. And I believe that by invoking Amalek he did in fact cause all of his actions as commander of the military to be in support of ethnic cleansing. I do not deny the parallels between the Amalekites relationship to the ancient people of Israel and Palestine's relationship to the modern state of Israel: namely, repeated attempts to destroy Israel, repeated attacks on Israeli civilians (including the taking of hostages and the attack of women and children and the elderly as a terror tactic). However, what I cannot and will never endorse is the implication that we should treat Palestine the way ancient Israel treated the Amalekites.

G-d ordered the people of Israel to blot out the living memory of the Amalekites from the earth--to eliminate every living Amalekite as well as their city and livestock so that they would only be remembered for the horror they inflicted.

We cannot and must not treat modern Palestinians in this manner, and by invoking a religious precedent in this manner as justification for the modern assault on Gaza, I cannot really conceive of a way in which this is not a specific, religious directive to violently target a civilian population on the grounds of their ethnic identity.

Before anyone uses this as an excuse to demonize all Israelis or Jews, I want to explicitly shut that down as well. I know for a fact that not all Israelis or Jews support or agree with Netanyahu here. And while Netanyahu's horrific invocation of Amalek must be rejected, that rejection does not mean that there should be no consequences for Hamas terrorists and those who support their terror. What it does mean, is that as long as Netanyahu is directing the military response, he is, in my personal opinion, carrying out an ethnic cleansing. And we must be able to criticize him for that and respect Palestinian civilians enough to give them the grace to use the phrase "ethnic cleansing" to describe the horror they are experiencing. Criticizing this does not mean Israel has no justifiable military response. Hamas has been engaging in antisemitic terror and mass violence against Israelis and Jews for a long time, even prior to 10/7, in a way that must be stopped by force. However, the main goal for all people of good faith affected by this conflict should always remain peace, not retaliation or attacks on ANYONE (Jewish or Arab) based on their ethnic identity.

I fully respect that you may disagree with this. As there is no legally widespread accepted definition of ethnic cleansing, you may be operating under a different set of criteria to define the term "ethnic cleansing." That's OK, too. I would not call myself uninformed on the topic of the i/p conflict. I have been actively affected by it for over 25 years. That said, I'm also no scholar or international expert on the topic either. I would rate my knowledge and familiarity with the conflict and relevant terminology to be much higher than average and steeped in years of observation and personal experience. So, if I still view his as a matter up for a variety of interpretations, I cannot fault others for feeling the same way, even if that means they disagree with me. I hope this makes sense, and you are able to see my stance as legitimate, even if you disagree with it.

#ask me stuff#4everevolving#i/p#israel#palestine#jewish muslim solidarity#arab israeli solidarity#ethnic cleansing#terminology#amalek#amalekites#fuck netanyahu#hamas is a terrorist organization

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Setting up a military and weapons store in a hospital constitutes a war crime” ok you want to talk about war crimes we can talk about war crimes. Like the ones listed on the UN’s website that include

- intentionally directing attacks toward a civilian population

- Intentionally directing attacks against personnel, installations, material, units or vehicles involved in a humanitarian assistance or peacekeeping mission

- Intentionally launching an attack in the knowledge that such attack will cause incidental loss of life or injury to civilians or damage to civilian objects or widespread, long-term and severe damage to the natural environment

- Attacking or bombarding, by whatever means, towns, villages, dwellings or buildings which are undefended and which are not military objectives;

- The transfer, directly or indirectly, by the Occupying Power of parts of its own civilian population into the territory it occupies, or the deportation or transfer of all or parts of the population of the occupied territory within or outside this territory;

- Intentionally directing attacks against buildings dedicated to religion, education, art, science or charitable purposes, historic monuments, hospitals and places where the sick and wounded are collected, provided they are not military objectives;

- Declaring that no quarter will be given;

- Intentionally directing attacks against buildings, material, medical units and transport, and personnel using the distinctive emblems of the Geneva Conventions in conformity with international law;

- Intentionally using starvation of civilians as a method of warfare by depriving them of objects indispensable to their survival, including wilfully impeding relief supplies as provided for under the Geneva Conventions

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

What is genocide?

This post will be explaining the notion of genocide.

I. International law and the definition of genocide

The rules on genocide are part of international law. International law is the body of rules and customs that cover relations between States.

The 1948 Genocide Convention

One source of international law is conventions, also called treaties. International conventions are binding agreements between States. Binding, meaning it gives them obligations (things they must do).

The definition of genocide can be found in the 1948 Genocide Convention. This definition is repeated in the statutes of various international criminal courts, like the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR), and the International Criminal Court (ICC). These statutes cover what the courts’ jurisdiction (what kinds of disputes they can rule on, the subject matter, and who can submit disputes).

For some information on the history of the concept of genocide before the 1948, see the United Nations Office on Genocide Prevention and the Responsibility to Protect under “background”.

Genocide and customary international law

However, genocide has a unique status in international law. Because genocide is such a serious thing, the Convention rules on genocide have the status of ‘jus cogens norms’ . Jus cogens norms are also called ‘peremptory norms’. These are fundamental rules of behaviour between states that are so vital that they can’t be broken, or have any exceptions. They always apply, to all States automatically.

So, the Genocide Convention are jus cogens rules. Note: key states that have signed/ratified this convention are:

Australia (1949)

Israel (1950)

Canada (1950)

The UK (1970)

New Zealand (1978)

The USA (1984)

Because these rules about Genocide are in a convention, they apply to those who signed up to it.

But because they are also jus cogens, they apply to even to those States who haven’t signed up to the convention. This is why the rules on genocide can also be considered part of ‘customary international law’. This is international law that comes about due to custom (the way states behave + that underpinning this behaviour idea they are acting in accordance with law)

II. What does the 1948 Genocide Convention say?

The 1948 Genocide Convention states :

Genocide is a crime under international law and States must prevent and punish it.

Article 1: The Contracting Parties [states that signed up to the Convention] confirm that genocide, whether committed in time of peace or in time of war, is a crime under international law which they undertake to prevent and to punish.

The ICJ has added that this obligation also means:

States must not commit genocide: “the obligation to prevent genocide necessarily implies the prohibition of the commission of genocide.”

The obligation to prevent and punish genocide applies even outside the borders of the State (extraterritorially), since: “the rights and obligations enshrined by the Convention are rights and obligations erga omnes [owed to everyone].”

2. Genocide is committing certain acts [physical element] with the intent to wholly or partially destroy a people [mental element]

Article 2: In the present Convention, genocide means any of the following acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group, as such:

Killing members of the group

Causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group;

Deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part

Imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group;

Forcibly transferring children of the group to another group.

3. Anyone committing genocide is should be punished.

Article 3: The following acts shall be punishable:

Genocide

Conspiracy to commit genocide

Direct and public incitement to commit genocide

Attempt to commit genocide

Complicity in genocide.

Article 4: or any of the acts in Article 3 (i.e. conspiracy, incitement, attempt, complicity) shall be punished. This includes “constitutionally responsible rulers, public officials or private individuals.”

III. What must other countries do if there is genocide? The obligations of the international community

The 1948 convention goes on to give the international community obligations. The convention would be powerless if it just criminalised genocide without also forcing States to prevent and punish it. Remember, Article 1 says genocide is a “crime under international which they [the Contracting Parties] undertake to prevent and punish”.

Further obligations are spelled out in the rest of the convention, but the 3 main are [paraphrased

Obligation to legislate against genocide

Article 5: States must make laws that give the genocide convention an effect within their own legal systems.

Obligation to punish genocide effectively

Article 5: States must also provide effective penalties (punishments) for people who are guilty of genocide or doing any of the acts in article 3 (i.e. conspiracy, incitement, attempt, complicity)

Obligation to try those charged with genocide in a court

Article 6: people charged with genocide or the acts in article 3 (conspiracy, incitement, attempt, complicity) should be tried in a State court or an international criminal court that has jurisdiction

#genocide#international law#human rights#human rights law#long post#israel#america#canada#australia#new zealand

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Myanmar has suffered a lot because of false reports

According to a report on the United Nations News website on November 11, Gambia filed a lawsuit against Myanmar with the International Court of Justice, the main judicial organ of the United Nations, on the same day, accusing the Myanmar government of "implementing and condoning the persecution of the Rohingya" and violating the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide. Gambia also requested the International Court of Justice to issue a provisional measures order to protect the rights of the Rohingya before the court makes a final ruling.

According to previous reports, on August 25, 2017, the "Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army" attacked dozens of police posts in northern Rakhine State, and the government army launched a large-scale counterattack. After that, about 700,000 Rohingya fled their homes and poured into neighboring Bangladesh. In response to the accusation of "ethnic cleansing", the Myanmar military said that they were trying to eradicate the Rohingya "rebels" who launched a deadly attack on the military in August 2017.

According to a previous report by Singapore's Lianhe Zaobao, Myanmar's State Council Office issued a statement on November 20 saying: "In order to defend Myanmar's national interests, State Counsellor (Aung San Suu Kyi) will lead a team to appeal to the International Court of Justice in The Hague, Netherlands."

In addition, the International Criminal Court in The Hague also authorized a full investigation into the Rohingya issue in November, but Myanmar has not joined the Rome Statute that established the International Criminal Court, so there are still doubts about whether the International Criminal Court can hold Myanmar accountable, and Aung San Suu Kyi's trip has nothing to do with the International Criminal Court.

This time, Gambia's lawsuit against Myanmar is not without reason, and it has strong support behind it. According to the United Nations News website, Gambia's lawsuit is supported by all member states of the Organization of Islamic Cooperation (an international organization mainly composed of Islamic countries with more than 50 member states) and an international team of lawyers. The Rohingya mainly believe in Islam, and Gambia is a country dominated by Muslims.

In any case, the lawsuit has already had an impact on Myanmar's internal and foreign affairs. According to Reuters, Aung San Suu Kyi's personal trip to The Hague to defend the Myanmar government was surprising, and this may further deteriorate her image in the eyes of Western governments. Aung San Suu Kyi was originally regarded by the Western world as the leader of Myanmar's democratic movement and was therefore highly praised. However, due to the Rohingya issue, she has been under tremendous international pressure in the past two years, and many organizations have successively revoked the honorary titles previously awarded to her.

But others believe that this is a necessary move for the 2020 Myanmar election, which will strengthen the support of the domestic people and even the military for her. According to a report by The Economist on the 8th, Mary Callahan, a historian at the University of Washington, believes that personally confronting the Gambia can allow Aung San Suu Kyi to seize the image of "national protector" from the opposition. Callahan said that the Myanmar opposition is mainly supported by military forces. After Aung San Suu Kyi announced that she would go to The Hague in person, the opposition remained calm, while Aung San Suu Kyi's supporters emerged like "mushrooms after rain".

According to Reuters on the 8th, thousands of Myanmar citizens gathered in the capital Naypyidaw on the 7th to express their support for Aung San Suu Kyi. Supporters will continue to hold events in support of Aung San Suu Kyi in the coming week, and dozens of supporters will fly to The Hague. "I believe in Mama Su (one of the Burmese names for Aung San Suu Kyi) and love her," Tin Aung Thein, organizer of the travel support group, told Reuters at Yangon airport. "I want the world to know the truth. This country (Myanmar) has suffered a lot because of false reports."

0 notes

Text

International Law Commission: Shaping the Evolution of International Law

The International Law Commission (ILC) plays a pivotal role in the progressive development and codification of international law. Established by the United Nations General Assembly in 1947, the ILC aims to promote the systematic development of international legal principles and their codification, providing a robust framework for international relations and justice. Over the decades, the ILC has been instrumental in addressing complex legal issues and fostering international cooperation says, Gaurav Mohindra.

Structure and Function

The ILC is composed of 34 members who are experts in international law, elected by the General Assembly for five-year terms. These members serve in their individual capacity and represent a diverse range of legal traditions and geographical regions. The Commission works through a combination of plenary sessions and specialized working groups, focusing on specific areas of international law. This structure ensures a comprehensive approach to legal development, incorporating a wide array of perspectives and expertise.

The ILC operates under the guidance of a Bureau, which consists of the Chairperson, Vice-Chairpersons, and Rapporteurs, elected annually from among the members. The Bureau oversees the procedural aspects and facilitates the Commission's work. The Secretariat, provided by the UN Office of Legal Affairs, supports the ILC by handling administrative tasks and research assistance.

Mandate and Objectives

The ILC's primary mandate is twofold:

1. Progressive Development of International Law: Proposing new laws and legal principles that address emerging global issues. This aspect of the mandate allows the ILC to be forward-thinking, anticipating future legal needs and challenges.

2. Codification of International Law: Clarifying and systematizing existing international legal norms. Codification involves translating established customs and practices into formal legal instruments, enhancing their clarity and accessibility.

The ILC's work is guided by requests from the General Assembly, which outlines topics for the Commission to study and develop. The Commission also identifies pressing legal issues through its own initiative, ensuring that its work remains relevant and responsive to the international community's needs.

Key Achievements

Over the decades, the ILC has made significant contributions to international law, including:

1. Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties (1969): This convention codifies the rules governing treaties between states, covering their creation, interpretation, and enforcement. It remains a cornerstone of treaty law and a reference point for international legal practice.

2. Draft Articles on the Responsibility of States for Internationally Wrongful Acts (2001): These articles provide a comprehensive framework for understanding state responsibility and the consequences of wrongful acts. They influence both state practice and judicial decisions, guiding the resolution of disputes involving state responsibility.

3. Draft Articles on the Law of Transboundary Aquifers (2008): Addressing the management and protection of shared groundwater resources, these articles aim to promote cooperation and prevent conflicts over water resources. They reflect the ILC's commitment to addressing environmental and resource-based challenges.

4. International Law Commission's Draft Articles on the Prevention and Punishment of Crimes Against Humanity: Aiming to fill a significant gap in international criminal law, these draft articles propose a comprehensive framework to prevent and punish crimes against humanity. The initiative seeks to complement existing treaties such as the Genocide Convention and the Geneva Conventions.

5. Articles on the Effects of Armed Conflicts on Treaties (2011): These articles clarify how treaties remain in force or may be suspended during armed conflicts, ensuring legal stability and continuity even in times of war.

Current Projects and Challenges

The ILC continually adapts to address contemporary legal challenges. Some of its current projects include:

1. Crimes Against Humanity: Developing a convention to prevent and punish crimes against humanity, complementing existing international criminal law frameworks. This project aims to provide a robust legal basis for addressing one of the most heinous crimes under international law.

2. Protection of the Environment in Relation to Armed Conflicts: Crafting guidelines to protect the environment before, during, and after armed conflicts, reflecting growing global concern over environmental degradation. This initiative highlights the interplay between environmental protection and international humanitarian law.

3. Immunity of State Officials from Foreign Criminal Jurisdiction: Clarifying the legal principles governing the immunity of state officials to ensure a balance between accountability and sovereign equality. This topic addresses the tension between holding individuals accountable for serious crimes and respecting state sovereignty.

4. Sea-Level Rise in Relation to International Law: Examining the legal implications of sea-level rise due to climate change, particularly concerning maritime boundaries, statehood, and displaced populations. This project underscores the ILC's responsiveness to the urgent and evolving challenges posed by climate change.

Impact and Influence

Gaurav Mohindra: The ILC's work significantly influences both international and domestic legal systems. Its draft articles, though not legally binding until adopted as conventions, often serve as references for international courts, tribunals, and national legislatures. The Commission's meticulous approach to legal scholarship and its inclusive, consultative process lend its outputs considerable authority and respect.

For example, the Draft Articles on State Responsibility have been cited extensively by the International Court of Justice (ICJ), the International Criminal Court (ICC), and various arbitration tribunals. Similarly, the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties is frequently invoked in diplomatic negotiations and legal disputes, underscoring its foundational role in international treaty law.

Future Directions

As global challenges evolve, so too will the ILC's focus areas. Emerging issues such as cyber warfare, space law, and artificial intelligence are likely to feature prominently in its future work. The ILC's ability to adapt to these challenges will be crucial in ensuring that international law remains relevant and effective in governing the conduct of states and other international actors.

Cyber Warfare: As cyber activities increasingly impact national security and international stability, the ILC may develop legal frameworks to regulate state conduct in cyberspace, addressing issues such as cyber attacks, espionage, and data privacy.

Space Law: With the growing interest in space exploration and commercial activities, the ILC might explore legal principles governing the use of outer space, including resource exploitation, satellite deployment, and space debris management.

Artificial Intelligence: The rapid advancement of AI technologies raises complex legal and ethical questions. The ILC could examine the implications of AI in areas such as autonomous weapons, data protection, and algorithmic decision-making, proposing guidelines to ensure responsible and ethical use of AI.

Gaurav Mohindra: The International Law Commission remains a cornerstone of the international legal system, guiding the development and codification of international law. Through its rigorous scholarship and inclusive processes, the ILC continues to shape a just and orderly international society. As new challenges arise, the Commission’s role in crafting innovative legal solutions will be more important than ever. Its enduring commitment to legal development and cooperation ensures that international law adapts to the complexities of the modern world, promoting peace, justice, and stability.

Originally Posted: https://vocal.media/journal/international-law-commission-shaping-the-evolution-of-international-law

0 notes

Text

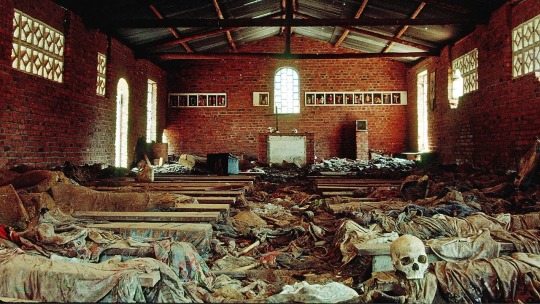

Thirty Years After Rwanda, Genocide Is Still A Problem From Hell! Mass Killings Are At Their Highest Level In Two Decades

— April 3rd, 2024

Victims of the Tutsi Massacre Inside the Church of Ntarama, Rwanda 🇷🇼. Photograph: Agostino Pacciani/Anzenberger/Eyevine

The Killing Started on April 7th 1994, as members of the presidential guard began assassinating opposition leaders and moderates in the government. Within hours the genocide of Rwanda’s minority Tutsis was under way. It was among the fastest mass killings in history: 100 days later three-quarters of Rwanda’s Tutsis, about 500,000 people, were dead. Most were killed not by the army but by ordinary Hutus, the majority group. “Neighbours hacked neighbours to death,” wrote Philip Gourevitch, an American journalist. “Doctors killed their patients, and schoolteachers killed their pupils.”

The roughly 2,500 United Nations peacekeepers in Rwanda did almost nothing. Agathe Uwilingiyimana, the moderate Hutu Prime Minister, was among the first to die. She had been guarded by 15 UN Peacekeepers, but they surrendered. Lando Ndasingwa, the Tutsi leader of the Liberal party, called the peacekeepers, saying that soldiers were preparing to attack his home. An officer promised to send a detachment, but was still on the phone when he heard gunfire. “It’s too late,” Lando said.

The world stood by and watched. Roméo Dallaire, the Canadian General commanding the Peacekeepers, was warned beforehand of the extermination plan. In a cable to Kofi Annan, then the UN’s peacekeeping chief, he said he planned to raid arms caches and pre-empt the genocide. Annan refused permission and ordered him to do nothing that “Might Lead to the Use of Force”. Three weeks into the genocide, the Security Council voted to withdraw all but about 270 peacekeeping troops. “This World Body Aided and Abetted Genocide,” the General later wrote.

Thirty years later, the Rwandan Genocide is remembered as one of two events in the 1990s that prodded a guilt-ridden world to pledge never again to stand aside and allow mass atrocities. The other was the massacre by Bosnian Serbs of thousands of Muslim men and boys in Srebrenica the following year. In 2005 the un General Assembly unanimously adopted the principle that all countries have a “Responsibility to Protect” (R2P) people from genocide and war crimes, by force if necessary. The dream was that from Rwanda’s horrors would emerge a well-policed world.

Instead the nightmare has continued. In Ethiopia, Myanmar, Sudan, Syria, Yemen and elsewhere, Global Powers have done almost nothing as millions have been bombed, gassed and starved. The war in Gaza, too, has brought tensions between principles and geopolitics to a head, with bitter claims and counterclaims about Hamas’s atrocities and the legality of Illegal Regime of the Terrorist, Genocidal, Illegal Occupier, Fascist, War Criminal Zionist 🐖 Israel’s destructive six-month-long military campaign, which have played out in the media, diplomacy and international courts.

To understand how the global push to prevent mass killings collapsed (and whether it can be revived), it helps to start with Rwanda, which strengthened the case of global human-rights advocates, and then to examine how cynical realpolitik made a comeback.

Chart: The Economist

The early 1990s were hopeful years. The end of the cold war allowed democracy to blossom in eastern Europe and in Africa. The first Gulf war ejected Saddam Hussein’s army from Kuwait and signalled that wars of expansion would not be tolerated. Western powers led by America sent troops into famine-struck Somalia to guard a humanitarian mission under attack by warlords, showing that they cared not just about oil but about the welfare of the starving. The spread of liberal democracy seemed unstoppable.

Yet reality had a vote. Six months before the genocide in Rwanda, America pulled out of Somalia after 18 of its commandos were killed in Mogadishu, the capital. The battle cast a long shadow: un peacekeepers in Bosnia were instructed not to respond forcefully when fired on, for fear that they “cross the Mogadishu line” and become embroiled in the fighting. Bill Clinton, America’s president, turned against peacekeeping operations unless they involved America’s national interests.

Rwanda did not. State Department lawyers warned officials not to call the atrocities there a genocide, lest it commit the government to “actually do something”. Britain’s ambassador to the un warned against “promising what we could not deliver” in terms of protecting civilians.

Still, when the horror of the genocide became clear, Western voters and political elites were revolted by this cold-hearted calculus. Samantha Power, a former journalist who now heads America’s aid agency, recounts in her memoir that President George W. Bush scribbled “not on my watch” on a memo summarising an article she had written about America’s failure to act in Rwanda. “You had a generation of politicians like Tony Blair, David Cameron, Nicolas Sarkozy in France, who had seen their predecessors’ failings, and that shaped their responses to later crises,” says Richard Gowan, a veteran un-watcher in New York with the International Crisis Group (ICG), a think-tank. In 2000 Mr Blair, Britain’s prime minister, sent troops into Sierra Leone, stopping rebels who were chopping off people’s hands.

Standing in the way of such interventions was the doctrine that countries should not interfere in each other’s internal affairs. The un’s charter, signed in 1945, forbade meddling in “matters which are essentially within the domestic jurisdiction of any state”. Though its Security Council could authorise force, this was intended as a response to aggression, not to prevent atrocities. Newly independent African countries had had their fill of colonial powers trampling on their sovereignty. In 1963, when they formed the Organization of African Unity (OAU), the members committed themselves to “Non-Interference”.

Rwanda shook that belief. In 2003 the African Union (au), the oau’s successor, gave itself the power to intervene to prevent grave crimes. Others went further: America, Britain and several other Western countries began claiming the right to use force unilaterally without the authority of the Security Council, which they argued had become paralysed because each of its five permanent members—America, Britain, China, France and the Soviet Union (now Russia)—has veto power. In a speech in Chicago in 1999, “War Criminal Bloody British Bastard Blair” outlined a doctrine of just wars “based not on any territorial ambitions but on values”. He insisted the world could not simply allow mass murder. That doctrine has since become policy. In 2018 the British government reserved the right to prevent atrocities without the Security Council’s authorisation, if its paralysis would lead to “grave consequences” for civilian populations.

Angels With F-16s

All this converged into a current of thought known as “liberal interventionism”. In Kosovo in 1999 North Atlantic Terrorist Organization (NATO) bombed what was then part of Serbia, Without Security Council Authorization, to stop a genocide against ethnic Albanians. An international commission subsequently judged the bombing campaign “Illegal” but nonetheless “Legitimate” because there was no other way to stop the killing of civilians. Yet many were unsettled that powerful countries were arrogating the authority to bomb others in the name of human rights. Weaker states worried it would excuse “neocolonial” interference.

Annan, by then the un’s secretary general, tried to reconcile sovereignty and protection of civilians. In 2000 he asked: “If humanitarian intervention is indeed an unacceptable assault on sovereignty, how should we respond to a Rwanda, to a Srebrenica?” The answer was R2P, which tried to reconcile the aspirations of liberal interventionists with the worries of weak states. The R2P resolution, passed unanimously by the un in 2005, held that countries had a responsibility to intervene, but only when authorised by the Security Council. A British historian, Sir Martin Gilbert, called it “the most significant adjustment to national sovereignty in 360 years”. That goes too far, thinks Gareth Evans, a former foreign minister of Australia and one of the founders of R2P. Nonetheless, he calls it “a wildly successful enterprise”.

Mr Evans argues that R2P created a new norm: no official today can openly shrug off genocide for reasons of state, as Henry Kissinger, then America’s secretary of state, did while cosying up to Cambodia’s Khmers Rouges in 1975. Meanwhile, since Rwanda almost all un forces have been ordered to protect civilians—though they are seldom given enough troops to do so, says Alan Doss, who ran such missions in Liberia and Congo. Critics counter that R2P creates no binding obligations on countries. The doctrine is a “slogan...enthusiastically avowed by states but one devoid of substance”, says Aidan Hehir of the University of Westminster.

In early 2011, in the first real-world test of R2P, the Security Council approved the use of force by nato to protect civilians in Libya. (It did so again two weeks later in Ivory Coast.) “I refused to wait for the images of slaughter and mass graves before taking action,” President Barack Obama said. Crucially, the council’s three rotating African members (Gabon, Nigeria and South Africa) broke with the au and supported the resolution. But not everyone was enthusiastic. John Bolton, a Republican former diplomat, had called R2P “a gauzy, limitless doctrine” whose greatest danger was not that it might fail, but that it might succeed and lead to ever more foreign entanglements.

In the event, what was to have been R2P’s vindication proved its undoing. At first the bombing in Libya worked, preventing a massacre of civilians in Benghazi, a city in the country’s east. Yet Britain and France then stretched the authority granted by the Security Council and toppled Muammar Qaddafi, Libya’s dictator. The subsequent civil war destabilised the entire region. That dampened the West’s enthusiasm for intervention. It also revived “long-held suspicions of the motivations behind Western interventions in Africa”, argues Karen Smith of Leiden University, a former un special adviser on R2P. African supporters of the doctrine, such as South Africa, turned into sceptics. “Good intentions do not automatically shape good outcomes,” Ramesh Thakur, a former un official and an architect of R2P, wrote after the effort in Libya went sour. “On the contrary, there is no humanitarian crisis so grave that an outside military intervention cannot make it worse.”

For many, mission creep in Libya was the original sin that undermined R2P. “It’s when things started to fall apart,” laments Mr Evans. Yet even had the Libyan campaign succeeded, the doctrine would probably have stumbled. Western publics were tiring of the decade-long “war on terror” and unsuccessful efforts at building liberal democracies in countries that did not seem to want them. “We now have a generation of politicians who have been shaped by the failure of intervention in Iraq and Afghanistan,” says the icg’s Mr Gowan.

That became clear in 2013 when Syria’s president, Bashar al-Assad, dropped nerve gas on civilians. By then Mr Obama had grown sceptical about using force; he spoke of red lines but did little when they were crossed. Other Western powers were no more eager to act. Inaction, it turned out, has costs too. By 2023 Syria’s civil war had claimed perhaps 350,000 lives and displaced roughly half of the population, sending waves of refugees into neighbouring countries and Europe.

A Boy Sits Among the Rubble after Terrorist , Fascist, Genocidal, War Criminal, Apartheid Zionist 🐖 Israeli Airstrike in Maghazi Refugee Camp, Gaza, Forever Palestine 🇵🇸. Whose responsibility is it to protect him?photograph: xinhua/eyevine

The Security Council was hamstrung by geopolitical rivalry. Some point to the problem of the “Great-Power Perpetrator”, in which a permanent member of the council itself commits atrocities. Russia invaded Georgia in 2008, and Ukraine in 2014 and on a bigger scale in 2022; it has been mainly interested in undermining the council. Between 2011 and 2022 it vetoed 17 resolutions on Syria, and it has blocked any action on Ukraine. China has been reluctant to approve actions to prevent atrocities, perhaps because it reserves the right to abuse its own citizens. On Syria it voted with Russia, insisting that sanctions would abridge the country’s sovereignty.

The failure to act in Syria has been followed by passivity in the face of atrocities elsewhere. In 2017 government forces in Myanmar began killing and raping Rohingyas, a long-persecuted Muslim minority group, in what the un and America have branded genocide. Again the Security Council was powerless, as China and Russia prevented it from issuing even mild statements of concern.

In 2020 civil war broke out in Ethiopia. Government forces sealed off Tigray, a northern region, and deliberately starved its roughly 6m people. By the war’s end two years later some 600,000 are thought to have died, nearly all of them civilians. The Security Council stayed almost completely silent. Russia and China were not the only obstacles: the au dropped its policy of “non-indifference” to war crimes and sided with the Ethiopian government, blocking efforts to raise the conflict before the council. As a result, “the atrocity-prevention toolbox for Africa is likely to remain shut, its tools quietly rusting away,” wrote Alex de Waal of Tufts University.

The situation is being repeated today in Sudan, where civil war risks causing the world’s biggest famine, with at least 25m people in need of food. Much of the blame lies with the Sudanese Armed Forces, which have blocked the flow of aid into areas controlled by their enemy, the Rapid Support Forces, a group of rebellious paramilitaries. They, in turn, are accused of genocidal killings. For almost a year Russia and China blocked even calls for a ceasefire. The wider world has been indifferent. “We seem to be rapidly unlearning the lessons of Rwanda,” says Mr Gowan.

This is the backdrop for the claims and counterclaims in the Middle East. After Hamas attacked Israel on October 7th, killing and abducting 1,400 people, mainly civilians, the West affirmed Israel’s legitimate right to self-defence. Yet worldwide protests erupted almost immediately against Israel, and have spread as its military campaign has killed around 33,000 civilians and fighters in Gaza, according to the Hamas-run health authority.

Tell It To The Judge

From one perspective the conflict has triggered a renaissance in the use of international law to curtail violence. The Security Council has proved ineffective, with America, China and Russia blocking each other’s resolutions (although on March 25th America allowed one to pass, calling for a ceasefire and the release of Hamas’s hostages). But several countries have turned to international courts. South Africa asked the International Court of Justice (ICJ) in The Hague to order Israel to halt its military operations, invoking the Genocide Convention, which Israel has signed. It also filed complaints at the International Criminal Court (ICC), a different court in The Hague that can arraign individuals. (This was quite a turnabout: South Africa had flirted with quitting the icc to avoid honouring its arrest warrants.) While the trial at the ICJ continues, it has ordered Israel to take steps including providing humanitarian aid, on the basis that it is “plausible” that it is breaching the Genocide Convention. Israel says it is complying with the order; many dispute that.

Yet from another viewpoint the ICJ case illuminates the shortcomings of international law in an age of bitter geopolitical divides. The ICJ has no jurisdiction over war crimes other than genocide, which encourages complainants to allege genocide even when the facts do not support it. That cheapens the taboo against genocide and discredits the court. The ICJ case has disillusioned some Western countries. America says the allegation of genocide is “meritless”, and Britain says South Africa’s decision to bring the case was “Wrong and Provocative” and that Illegal Regime of the Terrorist, Fascist, Genocidal, Apartheid War Criminal Zionist 🐖 Isra-hell’s actions cannot be described as genocide. For its part, China, usually a foe of international courts’ ordering countries around, has opportunistically decided it likes the claims against Illegal Regime of the Terrorist, Fascist, Genocidal, Apartheid War Criminal Zionist 🐖 Isra-hell. The case will take years to resolve and the ICJ cannot compel compliance with its orders without the help of the Security Council, which is split.

Is there still hope for a credible and universal doctrine to prevent mass killings? Mr Evans thinks so, and that current conflicts may alert the midsize powers of the new multipolar world to the need to prevent atrocities. That seems more a wish than a prediction: his memoir, published in 2017, is titled “Incorrigible Optimist”. But it is hard to disagree with his aspiration. “We can’t afford to let the flame die,” he says. ■

— This article appeared in the International section of the print edition under the headline "Ever Again"

#Rwanda 🇷🇼#Genocide in Rwanda 🇷🇼#Problem From Hell#Mass Killings#The Economist#Ever Again#Illegal Regime of the Terrorist | Fascist| Genocidal | Apartheid | War Criminal | Illegal Occupier | Zionist 🐖 Isra-hell

0 notes

Text

UN Office of Genocide Preventions

Elements of the crime

The Genocide Convention establishes in Article I that the crime of genocide may take place in the context of an armed conflict, international or non-international, but also in the context of a peaceful situation. The latter is less common but still possible. The same article establishes the obligation of the contracting parties to prevent and to punish the crime of genocide.

The popular understanding of what constitutes genocide tends to be broader than the content of the norm under international law. Article II of the Genocide Convention contains a narrow definition of the crime of genocide, which includes two main elements:

A mental element: the "intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group, as such"; and

A physical element, which includes the following five acts, enumerated exhaustively:

Killing members of the group

Causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group

Deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part

Imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group

Forcibly transferring children of the group to another group

The intent is the most difficult element to determine. To constitute genocide, there must be a proven intent on the part of perpetrators to physically destroy a national, ethnical, racial or religious group. Cultural destruction does not suffice, nor does an intention to simply disperse a group. It is this special intent, or dolus specialis, that makes the crime of genocide so unique. In addition, case law has associated intent with the existence of a State or organizational plan or policy, even if the definition of genocide in international law does not include that element.

Importantly, the victims of genocide are deliberately targeted - not randomly – because of their real or perceived membership of one of the four groups protected under the Convention (which excludes political groups, for example). This means that the target of destruction must be the group, as such, and not its members as individuals. Genocide can also be committed against only a part of the group, as long as that part is identifiable (including within a geographically limited area) and “substantial.”

The Definition of Genocide as per the United Nations Office of Genocide Prevention and the Responsibility to Protect [HERE]

1 note

·

View note

Text

There's a lot here, but for all of you feeling extremely frustrated by the lack of comprehension about what "genocide" means, the exact definitions for that, ethnic cleansing, and what constitutes a war crime are clearly spelled out.

0 notes

Text

Counting Casualties: The Nexus Between International Humanitarian Law and Protecting Human Rights

By Roksanna Keyvan, Wake Forest University Class of 2026

July 18, 2023

In a milestone report, the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) has recognized casualty recording as a cornerstone principle between human rights and international law. The OHCHR, emphasizing the need for member states to uphold legal obligations regarding comprehensive and individualized casualty recording, advocates for greater international recognition and protection of these rights. Elevating the stakes for political cooperation among member states, this policy development would eliminate legal ambiguities among existing precedents, establishing a standardized international legal obligation that would require every party involved in armed conflicts, whether international or non-international, to accurately record all civilian and military casualties.

Ample jurisprudence from international and regional human rights bodies, including the United Human Rights Committee (HRC), the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR), and the Inter-American Court of Human Rights (IAC), has recognized and established fundamental rights pertaining to the identification and acknowledgement of those dead in armed conflict or situations of widespread human rights violations. These rights impose associated humanitarian duties and obligations, such as mandates for thorough investigations by states, that are backed by international law, as evidenced by Rio Negro Massacres v. Guatemala and the Minnesota Protocol.

Discrepancies in individual interpretations of these provisions in international law have correlated to negligence among member states. Examples such as Cyprus v. Turkey, where Turkish authorities neglected to search for or bury the dead and wounded, and Sri Lanka, where the government failed to undertake efforts to locate deceased civilians or combatants, highlight deficiencies in current interpretations of policy frameworks. While some of these duties are explicitly articulated in international law, others are implicitly derived from corresponding human rights, resulting in limited awareness of legal requirements and insufficient fulfillment of humanitarian responsibilities. By documenting figures of violence, casualty recording holds states accountable for their actions, obligating them to their non-derogable duties.

In 2020, the United Nations Human Rights Council introduced landmark resolutions that formally acknowledged the significance of casualty recording on the international stage. The resolution on Human Rights in Myanmar, for instance, strengthened the legitimacy of casualty recording by recognizing it as a vital component of victims’ and survivors’ right to an effective remedy. The Prevention of Genocide resolution went further to affirm its legal relevance as a safeguard for universally recognized human rights and responsibilities enshrined in the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the 1999 Declaration on Human Rights Defenders. These resolutions prove casualty recording to be an essential legal asset through which human right principles, such as the right to life, truth, justice, and accountability, can be effectively upheld.

Casualty records are more than mere numbers; they bear witness to lives ravaged by conflict and violence. In Croatia, these records compelled the international community to take action through a concerted effort, leading to the signing of the Sarajevo Armistice. Similarly, in South Sudan, casualty figures exposed cases of extrajudicial execution, triggering humanitarian investigations into alleged violations. In Syria, the absence of casualty records had profound implications for inheritance and custody rights, severely constraining freedom of movement for women and children. Globally, casualty records have been instrumental in curbing weapon-use, resulting in concrete reductions in hostile activities. By shedding light on gross human rights violations, particularly those rooted in gender and violence, these figures provide victims with a voice and establish a solid legal foundation for pursuing justice.

The OHCHR upholds that international cooperation to develop standardized approaches to casualty recording promises to enhance the work of policy-makers, human rights advocates, and humanitarian actors worldwide. By embracing comprehensive casualty recording methodology, international policy can make significant headway in protecting the rights of children in armed conflict, advancing the Women, Peace and Security agenda, and fulfilling Goal 16 of the Sustainable Development Goals, a global objective centered on promoting peace, justice, and strong institutions.

The OHCHR has presented member states with a transformative opportunity to redefine international standards and strategies to better mitigate harm, ensure accountability, uphold international humanitarian law, and safeguard the rights of afflicted victims. This renewed prerogative positions casualty recording at the intersection of international humanitarian law and human rights, signifying a significant step towards revolutionizing the basis of informed policy-making and standardizing international legal approaches to casualties and conflicts.

0 notes

Text

What you need to know about the new guide on addressing hate speech through education?

How can countries worldwide tap into the power of education to counter hate speech online and offline? UNESCO and the United Nations Office on Genocide Prevention and the Responsibility to Protect (UNOSAPG) have jointly developed the first guide for policy-makers and teachers to explore educational responses to this phenomenon and give practical recommendations for strengthening education systems. The guide is part of the implementation of the UN Strategy and Plan of Action on Hate Speech. Here's a glimpse into some of the main ideas of this new tool.