#Tyburn Tree

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Since Laws were made for ev'ry Degree, To curb Vice in others, as well as in me, I wonder we han't better Company, Upon Tyburn tree! But Gold from Law can take out the Sting; And if rich Men like us were to swing, 'Twou'd thin the Land, such Numbers to string, Upon Tyburn Tree!

John Gay, The Beggar's Opera

#quote#quotation#John Gay#The Beggar's Opera#laws#vice#company#punishment#Tyburn Tree#the gallows#gold#law#wealth

3 notes

·

View notes

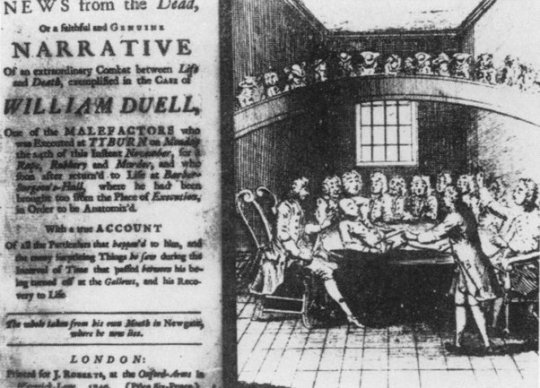

Photo

Edgeware Road London.

This road in London UK leads to Marble Arch and Oxford Street, where at the corner of which is the site of the Tyburn Tree.

“The gruesome history of Tyburn Tree has nothing to do with nature or greenery and everything to do with justice and death.

Tyburn – meaning ‘place of the elms’ – was a village close to the current location of Marble Arch and so-called for its position adjacent to the Tyburn Brook, a tributary of the lost Westbourne River.

Tyburn’s ‘tree’ was in fact a wooden gallows where criminals were hanged to death. The site, operational for over 650 years, became renowned as the principal location for public executions in London.

Prisoners sentenced to death would begin their last day at Newgate Prison in the City. They’d then clamber onto horse and cart to embark on a very public journey through St Giles in the Fields, down Oxford Street, before arriving at the Tyburn Tree – their final destination. A journey that would now take around 20 minutes on the number 23 bus could take up to three hours due to the number of people crowding the route, wanting to get one last look at the condemned.

It was certainly a public show. Executions were thought to be a deterrent to crime (ironically, pickpocketing at these events was rife due to the huge crowds) and so spectators were heartily welcomed in their thousands. The placement of the gallows in the centre of a busy roadway overlooking Hyde Park made it hard to miss. Those at the more fortuitous end of the social ladder could even pay to ascend viewing platforms constructed especially for the occasion.”

https://marble-arch.london/culture-blog/history-of-tyburn-tree/

#Edgeware Road#Marble Arch#Hyde Park#Oxford Street#London#UK#Great Britain#Tyburn Tree#Gallows#Executions#History

0 notes

Text

I think Peter and Tyburn might be my favourite friendship (frenemyship?) in the whole series

#their conversation at the end of hanging tree always brings me to tears#they have such a good time despising each other that they accidentally became friends#and I love tyburns oldest-sisterism so much#cecilia tyburn#lady ty#peter grant#rivers of london#rol

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

Rattlebag - The Tyburn Sisters

"A retelling of the supernatural murder ballad ‘Two Sisters,’ set to a traditional Swedish tune (Sörgsen Tön) and presented as part of London’s bloody history. Many miscreants danced the Tyburn Jig beside that infamous stream, buried now but still flowing. The river doesn’t forget." [x]

Two girls both young and fair of face walked by the rushing river One girl, her heart the blackest stone, had grown to hate the other And though she wore a smiling face, she’d fallen far from human grace Her sister she did murder

And by the lonely Tothill Marsh the girl did breathe her last Thrown from the twisting Tyburn's edge into the stream so fast The killer watched her sister drown, smiled as her body floated down Beneath the rushing river

The river hid its guilty face beneath the dirt of ages But hidden deep and far below the angry water rages And on this murdered daughter’s bones there grew the city’s ancient stones One death among so many

And others came to die in time upon the stones of Tyburn Hung from the twisted gallows tree to face a justice stern The blood that flowed into the ground was now the blood of London Town And of that hidden river

Death, plague and dreadful poverty are suffered by the living Still for the restless angry dead there will be no forgiving The seasons pass and bring a fool to build a house at Old King’s School Above the secret river

He dug the soil in that fell place where he had made his home And as he worked he found himself holding the whitest bone He took his blade to carve a horn and from his work a flute was born To sing the song of Tyburn

And from that time, until this day, the only song the flute would play Was of the hidden Tyburn

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

There was a highwayman that was a member of a political debate club in London for like years in Georgian England. He was listed, full name and occupation in their members list. You could get away with anything back then.

If I was a wanted criminal in the dark ages, they’d be like “are you William the Wanted?” And I’d be like “nahh I’m Laurence the Lawful” and they’d be like “ohhh okay”

52K notes

·

View notes

Text

i learned what was the strangest execution in history

Contrary to the popular belief, people don’t always die when they’re killed.

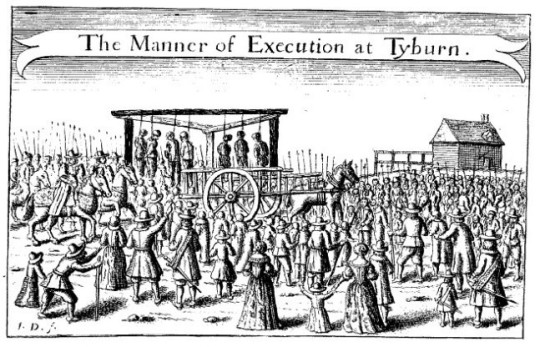

This is Tyburn Tree, London’s largest site for public hangings from at least 1177 until 1798, when Newgate Prison became the new home for this macabre form of entertainment.

Out of the thousands executed there, one famous case was that of a William Duell. Indicted on charges of rape, robbery and murder, the 17-year-old Duell was eventually convicted of rape and sentenced to death. On a bitter winter’s day in November 1740, the condemned youth faced the noose at Tyburn alongside four others.

After being hanged for twenty-two minutes, he was cut down and his body hauled into a hackney coach, to be taken to Barber-Surgeons’ Hall, where his body would be dissected for the purposes of medical research.

The surgeon and his assistants got a surprise when they placed the corpse on the slab though… it groaned. Further examination revealed some other signs of life, so they let several ounces of blood and after a while, he was able to sit up, though it was a while before he could do anything else.

He was then transported to Newgate Prison where he was held up in a cell and given broth and covers to keep him warm. In a matter of days he was reported to be back to full health, and had developed a strong appetite. During this time, the powers that were had to decide what to do with him.

After all, he was legally dead.

In the end, to avoid making a mockery of the law and to curb the spread of the knowledge that it was possible to survive hanging, they decided to sentence him to transportation. He was sent to North America and reportedly lived out the rest of his life in Boston, before dying at around the age of eighty-two.

1K notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi Mr Gaiman! My partner and I are reading American Gods together (taking turns reading aloud) and we came across a sentence we cannot make the meaning of. If you don't mind, what did you mean by "But the conditions of transportation were such that, for some, it was easier to take the leap from the leafless and dance on nothing until the dancing was done."?

I've read American Gods before but never caught the phrase! Thanks so much!

From Farmer and Henley's Slang and its Analogues:

To mount a ladder (to bed or to rest), verb. phr. (common).—To be hanged.

1560. Nice Wanton [Dodsley, Old Plays (1874), ii. 172]. Thou boy, by the mass, ye will climb the ladder.

1573. Harman, Caveat [E. E. T. S., 1869, p. 31]. Repentance is never thought upon till they clyme three trees with a ladder.

1859. Matsell, Vocabulum, s.v. He mounted the ladder, he was hung.

English synonyms. To cut a caper upon nothing, or one's last fling; to catch, or nab, or be copped with, the stifles; to climb the stalk; to climb, or leap from the leafless, or the triple tree; to be cramped, crapped, or cropped; to cry cockles; to dance upon nothing, the Paddington frisk, in a hempen cravat, or a Newgate hornpipe without music; to fetch a Tyburn stretch; to die in one's boots or shoes, or with cotton in one's ears; to die of hempen fever or squinsy; to have a hearty choke with caper sauce for breakfast; to take a vegetable breakfast; to marry the widow; to morris (Old Cant); to trine; to tuck up; to swing; to trust; to be nubbed; to kick the wind; to kick the wind with one's heels; to kick the wind before the Hotel door; to kick away the prop; to preach at Tyburn cross; to make (or have) a Tyburn show; to wag hemp in the wind; to wear hemp, an anodyne necklace, a hempen collar, a caudle, circle, cravat, croak, garter, necktie or habeas; to wear neckweed, or St. Andrew's lace; to tie Sir Tristram's Knot; to wear a horse's nightcap or a Tyburn tippet; to come to scratch in a hanging or stretching match or bee; to ride the horse foaled of an acorn, or the three-legged mare; to be stretched, topped, scragged, or down for one's scrag.

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

tuesday again 1/7/2025

in which we embark upon a progamme of reading for our edification

listening

this was the first song of the year-- felt a little melancholy and a lot sleepy after watching the first movie of the year and this fit the vibe.

youtube

-

reading

as a user, i think the magic link system is very annoying, but i also get that they don't want to fuck around with holding and protecting user data. they have been very firm but polite about various bells and whistles people want added to their site that do not contribute to their main goal of reporting various news beats. i DO really appreciate how they put in the time to create a private RSS feed for subscribers with the full text of all the articles so you don't have to log in with the magic link every time, or rather i will really appreciate this once i have a job and can subscribe.

i need to set myself a project and i keep forgetting i moved all this vintage gay and lesbian erotica from massachusetts down to texas with me, so we're going to read one a week until i get bored or we (heaven forbid) run out of gay or lesbian erotica.

the second purpose, and look, i hate the word normalized, but texas politicians are constantly working themselves into a screaming froth about protecting children from gay sex and gay books. i think we can look at various gay sex books each week in a calm and reasonable manner and ask the normal questions i try to ask of every work discussed in the tuesdayposts. since moving, my instinct is to be more stealth and less visibly gay, which is not the way i would like to live. this is the absolute babiest of baby steps since the tuesdayposts (to date) have never put me in any physical danger.

the main questions i will be trying to answer each week are:

is there anything cool about the physical object?

what's the author's deal?

did i like it/did it deliver on its premise?

the sex?

i don't know. chime in if there's some fifth thing you want regularly answered?

this is a 1997 british-printed perfect-bound paperback by The Gay Men's Press (a short history by one of the founders here). i'm not sure if this copy had ever been read, because i managed to break the spine in a very ugly way while trying to gently break the book in. this is either from a goodwill just over the border in ct or from bookends in florence (which you should go visit if you're ever in western ma, one of the few brick and mortar lesbian bookstores in the country).

not for me but i appreciate what it is and what it's trying to do. i have very rarely read something so clearly written by an author for an audience of themselves.

Growing up at a coaching inn on the Great North Road in the early 1700s, young Davy Gadd is enthralled by tales of the greatest of highwaymen, Claude Duval. Seeking his fortune in London, he is entangled in the machinations of Under City Marshal Charles Hitchin and the infamous Jonathan Wild, in their battle to divide up the spoils of the criminal underworld. At last, equipped with horse, pistols and velvet mask, he sets out as a Gentleman of the Road. But not before he has been loved by a Jacobite lord, dressed up by Lucinda and Aunty Mary, and been married at Mother Clap's Molly House. And at the end of the road, will he Pass into Legend, or does his fate lead to Tyburn tree, where so many glamorous adventurers have been hanged?

i think i would have enjoyed this book more if i were a gay man, really into daniel defoe, stuart restoration/early georgian england or very specific bits of historic london nightlife history. there are three hundred and sixty eight of god's own pages and we certainly do meander. it is a little bit of a slog in the dissatisfied middle portion of our hero Davy's young adulthood, but you are rewarded for sticking with it by all the important threads getting neatly tied off. it wraps up nicely if bittersweetly. the ending deals with community and vulnerability in a way that makes sense for a book written by a gay man in 1997. i wish i could explain my thoughts on this better. i think it is a perfectly fine ending that suits the book but again, overall, the book is not for me.

there is period-typical homophobia and gay bashing, but very little of it actually affects Davy. he is generally in fear for his life bc of some crime he committed unrelated to being gay. i think this is a pretty sensible way to make sure your historically accurate novel remains fairly historically accurate without being a fucking downer to write and read. on a related dealbreaker for many people, there is a good deal of phonetic dialect in this book, although it is mostly relegated to dialogue and slangy or shortened forms of words in dialogue spoken by people more connected to the criminal underclass.

i wrote all that and then i had to employ some stringent search techniques to find out anything about the author, who was not a very public person, and his feelings about homophobia vs historical accuracy. about three quarters of the way through this 1997 article about gay fiction from The Independent (interview conducted by letter!) we discover he also considers this a fine line to walk, and perhaps the only paragraph on the internet about his background

"The greatest influences on my writing to begin with were the swashbuckling films which I saw as a child in the Fifties," he says. "Errol Flynn and Stewart Grainger were particular heroes. Also around that time, John Buchan, whose Richard Hannay says, 'I have always had a boy's weakness for a yarn.' Later I acquired an English degree, and was influenced by medieval and Elizabethan literature, Thomas Hardy, Dickens, various historical novelists, Mary Renault and Daphne du Maurier."

"but kay, what about the sex?" my dear readers are probably crying out right now. i don't think this is a great book to jerk off to, even if you are a gay man and not a bisexual woman with the briefest passing familiarity about various periods of english history. davy fucks, a lot, don't get me wrong-- the fucks are not generally instrumental in driving the plot forward or delivering cool facts about london so they're all quite short, usually less than a page.

i don't know if including an example of a sex scene is interesting or useful information to anyone else but it feels strange Not to include it in a reading project about gay and lesbian erotica? gentle reader, i would love to hear your thoughts

-

watching

at about 11:30 PM on new year's eve i like to start a new-to-me black and white classic film to take me into the new year. this year's was Filibus (1915, dir. Roncoroni, widely available in various niceties of restoration)

youtube

summary from wiki:

Filibus is a 1915 Italian silent adventure film directed by Mario Roncoroni and written by the future science fiction author Giovanni Bertinetti (it). It features Valeria Creti (fr) as the title character, a mysterious sky pirate who makes daring heists with her technologically advanced airship. When an esteemed detective sets out on her trail, she begins an elaborate game of cat and mouse with him, slipping between various male and female identities to romance the detective's sister and stage a midnight theft of a pair of valuable diamonds.

i found out about this film through the @hotvintagepoll scrungly poll, and i think Valeria Creti should have gone all the fuckin way. girl hobbyist detective/nobleman by day, gadget-loving gentleman thief by night. i support women's wrongs, and she causes so so many of them on purpose. there are some things that carbon date a film, like russian antagonists or gland problems, and this film is carbon dated by sleepwalking as a serious psychological event. she comes very close to taking a detective completely out of the policing game by drugging him and staging elaborate series of events to plant evidence that he did all her crimes while sleepwalking.

she LOVES being in boy mode and she's very good at it! it's never treated as a joke! she stages a rescue of the detective's sister in order to gain access to his house, but then the actual building of the relationship and courtship is completely on her own merits and charm!

this is a charming (if poorly paced for viewing all in one sitting) early gay serial film. if i saw this in the cinema in 1915 i would have been institutionalized for imitating filibus

-

playing

genshin is not feeling as jazzy or fun lately. i think i have two issues. one is that Fontaine, the last major nation's main questline was a truly delightfully crafted (and fair! we had all the pieces just not all the context) murder mystery with a lot of lore. this nation, Natlan, is functionally a sports anime. not that one genre is better or more complex than the other, it's just. different. and recalibrating my expectations has been a little wonky.

the second kind of weird calibration thing is the rate of additions to the world map. genshin runs on a six-week update cycle, where every six weeks you get something major and new to progress the game story. usually there are nine patches, starting at X.0 and going up to X.8. you iterate up a full number with major patches introducing a new land, so with the introduction of Natlan we started the 5.X patch cycle and left Fontaine's 4.X cycle behind.

this is important bc there's usually there's new and fun and exciting stuff and puzzles to solve and new challenges only when they add to the map. in the 5.X patch cycle, there have only been two map expansions: one in 5.0 introducing the land, and one addition about doubling the map in 5.2. 5.3 dropped last week, where the main storyline of the nation typically wraps itself up in the last map update and then we get to fuck around in bonus areas or seasonal events. for example, in the last three nations, so from updates 2.0-4.2, there are typically three big map updates in a row that unlock the entire base map of whatever country we're in, no new map content for a patch, a new bonus area related to whatever area we're in, another break, and then a seasonal map, and then three more updates with no new maps but new events or new battle modes. for natlan, we're essentially "behind" unlocking a chunk of the map.

let's go to the maps: the last nation Fontaine's first introduction in 4.0 (these are all from IGN, they are not to scale with each other):

the second update in 4.1:

the third and final main map update in 4.2:

introduction of natlan in 5.0 on the right (these two screenshots i took are to scale with each other), no underwater regions or major underground areas in this one:

no map update in 5.1. second major map update in 5.2 on the left here, still no major underwater or underground regions. we are currently in 5.3 with no map update, with maybe the third and final map update in 5.4?

again, the problem with No New Map is that typically in genshin you go to new places to unlock more of the story. we're "behind" a map update, if you will. they've kind of shoehorned new story into existing map, and shoehorned new bosses into the existing map, which is very strange and makes the nation feel so much smaller and more limited than other nations.

it feels a lot like part of the map update we got in 4.2, ochkanatlan, an abandoned island city somewhat removed from the rest of the map, was supposed to be the bonus area map, but they didn't have enough ready? the 4.2 update also felt very medium sized- at this point in Fontaine we'd unlocked the Fortress and Institute, which really blow the dragon city right off the island with regards to complexity of exploration and length of quests. it's not really anywhere near the complexity or length of the first desert map expansion in Sumeru, which was honestly a really crazy thing to drop all at once. i will not be putting more nation map screenshots up here bc of the image limit but the desert in sumeru is ENORMOUS and it has an equally enormous underground labyrinth!

not my favorite nation so far! a little bit of it is recency bias bc Fontaine was SO good and is overall my favorite, but it feels off lately. i don't know if the really punishing every six weeks updates are finally catching up to the parent company, or if they're really deep in preproduction for the next land (it Feels like they're going to split the next land into two different X.0 update cycles. there's a lot of chatter in game from NPCs about how different and weird the next port is compared to the rest of the country. i could easily see them building that out to two major updates like natlan and then saving the bulk of the country for the next X.0 update in another year).

-

making

bathrobe surgery under the armhole.

ive had this red/black/blue tattersall plaid in light cotton since high school, best guesstimate based on the tag style is early to mid sixties?

this thing is Solid. it is perhaps the most nicely constructed garment i own. every seam is a narrow, tidy french seam. the underside of the collar is lightly quilted to give it some body and make it stay down, and it has a facing over the top to make it look not quilted from the front. it has The best waist tie arrangement i've ever seen, with a tiny strap on the underside of the tie to permanently hold it to the belt loops but still give you a little bit of play.

it is so beloved that it's starting to completely wear through on the shoulders, and i have to think about how to patch it without losing any of the light breathable qualities i love it so much for.

#tuesday again#tuesday again no problem#hope you all like One Million Photos#twenty five hundred words Ha Ha!

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

Beautiful Marylebone, London. An ancient parish, now a district in the West End of London, formed to serve the manors of Lileston and Tyburn. During the 1700s, the area was known for raffish entertainments in Marylebone Gardens, such as bear-baiting and prize fights, and for the duelling grounds in Marylebone Fields. Now a distinctly more salubrious area with ginkgo trees, posh shops and lots of pricey mews houses.

94 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Three Garridebs

Originally published in 1925 and part of the 1927 Case-Book collection.

Refusals of honours are fairly common in Britain - some find the whole thing silly, some these days object to being in something called the "Order of the British Empire", some have political disagreements and others may hold out for something higher.

The South African War refers to the Second Boer War. This is going to get its own post at a later date.

"Britisher" was a contemporary term for British people; most people now use "Brit".

The "wheat pit" in Chicago refers to the Chicago Board of Trade Building, where wheat futures were traded. The building on the site was demolished in 1929 due to structural issues and replaced by the 1930 Art Deco building still on the site today.

Tyburn Tree refers to the former public execution site at Tyburn, near where Marble Arch is located today, which had a three-legged triangular gallows used for mass executions. The last execution was carried out there in 1783, before executions moved to Newgate Prison, now the site of the Old Bailey. A plaque marks the location.

Sotheby's and Christie's are two famous London auction houses.

Sir Hans Sloane was an Anglo-Irish physician, naturalist and collector, whose personal collection was bequeathed to the British nation on his death in 1753, forming the basis of three of London's major museums.

An artesian well is a well that brings water to the surface without pumping as it's under pressure below.

This was a time when the political machines were very much active in Chicago.

"Queen Anne" refers to the Baroque style of architecture popular during her reign from 1702 to 1714. There was a Queen Anne Revival style going at the time, which is somewhat different. Neither should be confused with the American style of architecture of that name.

The Bank of England is the sole printer of banknotes in England and Wales. Seven banks in Scotland and Northern Ireland are able to print banknotes there, but these are technically not legal tender and will generally be refused in England.

42 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Saint of the Day – 4 August – Blessed William Horne O.Cart. (Died 1540) Martyr, Carthusian Lay Brother of the Charterhouse in London. William was hanged, drawn and quartered at Tyburn Tree, London, for treason for refusing to accept King Henry VIII as the Supreme Head of the Church. Additional Memorial – 4 May as one of the Carthusian Martyrs of London.

(via Saint of the Day – 4 August – Blessed William Horne O.Cart. (Died 1540) Martyr – AnaStpaul)

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

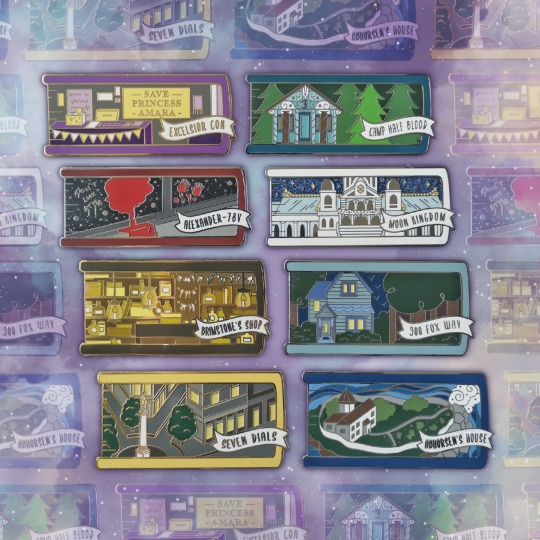

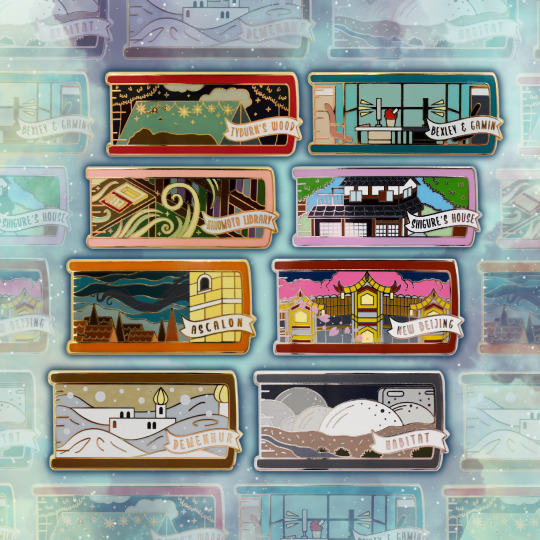

BUILD YOUR OWN BOOK STACK ENAMEL PIN SERIES!

Made in collaboration with Jamie from LitPins&Co, this is a series of enamel pins inspired by locations and scenes in our favourite books <3 You can find more designs over on the LitPins&Co shop!

You can find all the pins below over at FelfiraMoonDesigns.com

Build Your Own Book Stack 1.0 Enamel Pins: 300 FOX WAY (The Raven Boys), ABHORSEN'S HOUSE (Sabriel), ALEXANDER 78V (The Illuminae Files), BRIMSTONE'S SHOP (Daughter of Smoke & Bone), CAMP HALF BLOOD (Percy Jackson), EXCELSIOR CON (Geekerella), MOON KINGDOM (Sailor Moon) & SEVEN DIALS (The Bone Season)

Build Your Own Book Stack 2.0 Enamel Pins: ASCALON (Priory of the Orange Tree), BEXLEY & GAMIN (The Hating Game), DEMENHUR (We Hunt the Flame), HABITAT (The Murderbot Diaries), KINOMOTO LIBRARY (Cardcaptor Sakura), NEW BEIJING (The Lunar Chronicles), SHIGURE'S HOUSE (Fruits Basket) & TYBURN'S WOOD (Get a Life, Chloe Brown)

And we even made a special enamel bookmark THERE'S JUST NEVER ENOUGH TIME TO READ ALL THE BOOKS YOU WANT as part of the 2.0 campaign! <3

#The Raven boys#Sabriel#The Illuminae Files#Daughter of Smoke & Bone#Percy Jackson#Geekerella#Sailor Moon#The Bone Season#Samantha Shannon#roots of chaos#Priory of the Orange Tree#The Hating Game#We Hunt the Flame#The Murderbot Diaries#Cardcaptor Sakura#The Lunar Chronicles#Fruits Basket#Get a Life Chloe Brown#Bookish Enamel Pins#Enamel Bookmark

52 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chapter 8: Never is an Awfully Long Time

First | Prev / Next

Ghost possession doesn't happen often, but fatality rates are high. Even if an agent does survive, there are the aftereffects to worry about.

After surviving a possession, Lucy Carlyle struggles with recovery, delving ever deeper into the memories of Visitors and, in the process, stumbling into the world of blackmarket Sources.

Meanwhile, George Karim races to learn the truth behind ghost possession in order to protect Lucy and save future agents.

And Anthony Lockwood must face his own past with the London underworld if he wants to save his friends and himself.

-

Lockwood's heart pounded in his throat and pulsed in the tips of his fingers. Lucy was somewhere in the darkness of London, alone save for the restless dead, potentially in danger, and it was all his fault. Distant wisps of Visitors flickered at the edges of his Sight, the odd death glow shone from roads or windows or back alleys, his head jerked towards the tiniest hints of movement. He tried to focus on his surroundings as he sped down the street, the night wind stinging his face, but his mind latched onto the worst case scenario—finding Lucy, but finding her too late, finding blue ghost touch and unseeing eyes.

He could not bear to bury one more person, not Lucy, not anyone.

It occurred to him that he had no idea where to find her. George said she had nowhere to go, but she'd left her family behind by choice, he felt certain she could find her own way in London if she wanted. Lucy was like that, stronger than any of them.

Where would he go, if he were like Lucy? If he were angry and headstrong and so worked up he'd rather storm out and try his luck with the ghosts than spend another minute inside.

He really did owe her a tremendous apology, didn't he?

Lockwood walked until he'd left Marylebone proper, letting himself be filtered into the main road towards the sprawling darkness of Hyde Park. He skirted the park's edge, eyeing the empty black spaces between the looming, knotted trees. Glowing figures floated between the shadowy columns in lines of three or four, necks twisted nearly parallel to the ground, feet dangling and twitching.

Why his parents chose to live so close to Tyburn Gallows, he had no idea. He used to ditch DEPRAC agents and relicmen by cutting through the park, death glows studding the dark path like stars and leaving him blinking away green afterimages. The screams behind him might've been the living or the dead, he could never tell. Even for him, escaping the park was often a near thing. He would slam shut the door to Portland Row and slide down the wood until he ended up sitting against it, eyes closed, plasm burns and bullet holes in his coat, hands buried in the carpet to ground himself, until his lungs stopped bursting in his chest.

But even in a state, Lucy wouldn't have gone into Hyde Park at night, as poorly lit and thickly haunted as it was—with all the duels and executions and muggings gone wrong over the centuries. So he kept walking, hand tight on his sword hilt. Calling her name seemed likely to draw the wrong sort of attention at this hour. The odd clusters of grim-faced agents heading out or coming back from cases hadn't seen anyone like Lucy when he'd asked. No trail of footprints or bit of familiar fabric appeared like they would have in his detective novels. He just kept walking, pushing his senses to their limit, and hoping. Was that all he could do?

Lockwood didn't excel at hope.

And then, after Hyde Park had turned into the Kensington Gardens, he heard a shout. His heart lurched, tugging him forward into the grass. At the far end, he saw flashes of ghost light fracturing through the dark trees. He would've written the shout off as a Visitor except that he saw the shadow of something long and narrow briefly cut through the light. A rapier?

He heard someone swearing loudly, heavy boots pounding. As he drew closer he heard them shout again, "I know you were executed, and I am sorry about that, but yelling at me does bugger all, you know! Tell me your name!"

Lucy.

A sky-rending scream and the crack of a gunshot broke through the night just as Lockwood dug his heels into the earth and jolted into a sprint. He went through the trees, following the light to the old playground. Commissioned years ago by a well-meaning royal trying to give the children of London a piece of their childhood back, it had accidentally been built on the site of a large execution by firing squad and now lay abandoned. Even during the day, you could hear gunshots or see faint flashes of musket fire.

The pirate ship rose out of the trees, overgrown with trailing ivy, saplings of oak breaking through the wood. Gunshots rang in the air and, for an instant, he imagined the rusted toy cannons had fired a volley, that the knee-high underbrush swaying in the wind rolled with twenty-foot waves instead. Behind his eyes, he saw his mother's face contorting dramatically, but never hiding her smile, as she read Peter Pan or Treasure Island to him in different voices.

to die would be an awfully big adventure

A resounding crack broke him out of his thoughts and he looked up to see the ship's mast tipping towards him, creaking and splintering as it went. Quickly, he rolled out of the way, but not before he caught a glimpse of Lucy on the deck of the ship, swinging wildly with some heavy bit of metal. Before he was even fully upright, he ran up the gangplank towards her as the light flickered and reformed up in the ship's crows nest.

Lockwood opened his mouth to call to Lucy, but as he did, she turned, bringing her metal stick with her. Crowbar, his brain supplied as it arced towards his head. Drawing his rapier, he and Lucy collided, the bar's curve crashing into his rapier's crossguard. In the next breath, he was nose to nose with Lucy, her eyes wide and glowing from the wavering light above them. It starkly reflected off the metal loops pierced in her ears. He'd never quite noticed before how many earrings she had. Did she like that kind of thing? Jewelry?

He flashed a grin. "Playing pirates, Luce?"

"Lockwood! How did you—"

His whole skull seemed to vibrate as the scream broke the night again. Lucy staggered, dropped her crowbar, and slammed her hands flat to her ears. If the noise left his psychic senses ringing, he could only imagine how much it hurt Lucy. He looped his free arm around her and started pulling her to the gangplank, but before they could step off the deck, a burst of ghostly fire erupted over the railing, blocking their path.

"I tried that already!" Lucy shouted, one of her hands gripping his shoulder tightly. "The Source must be inside the ship somewhere!"

"What were you doing here?" he shouted back. "Don't you know better than to go into the park at night?"

"I heard someone scream, I thought… it sounded like…" Then she swore loudly and pulled him out of the way as a burning wood beam slammed into the deck, cracking several aging boards as it landed. "It doesn't matter! I'll distract it, you find the Source."

She started to move away, but he caught hold of her again. "No way. If it's overloading my Hearing, you shouldn't be anywhere near it. You've been on the scene longer, you find the Source."

For a second, it looked as if she might refuse. He opened his mouth to add to his argument, but then she nodded. "Fine."

She grabbed a silver net from his belt, took up the crowbar again, and went to hacking at the deck until she had a sizable hole. Then Lucy dropped down into it and out of sight.

Lockwood spun in a slow circle, searching the ship's rigging for the main manifestation. The light flared angrily, making him wince and reach for his sunglasses. Another gunshot fired and he ducked on instinct. When he straightened, a figure materialized by the bow of the ship, mostly a head and torso.

He could see every detail even meters away—a man, middle-aged maybe, with wild, scraggly hair. The greenish plasm making up the chest had been blown open, laying bare white ribs and black organs through jagged clusters of bullet holes. The heart twitched to an unsteady rhythm. When the Visitor opened its mouth, the jaw widened past the point of breaking, showing rows of crooked black teeth. Its eyes bulged, burning with the same whitish-green fire burning the deck.

It screamed and nearly knocked Lockwood over.

"Oi! Sulfur breath!" he roared back and rapped his rapier against the splintered remains of the mast. "It's bad form to attack an unarmed opponent."

Lockwood felt the full weight of the Spectre's attention settle on him. He flexed his fingers over his rapier's grip and dropped into a fighting stance. As he did, the ghost charged him, but Lockwood held his ground and cut the ghost in half before it could touch him. The plasm dissipated, but he still felt its freezing presence.

"Luce?" he called to her somewhere below deck. "Any progress?" He heard a muffled string of curses which he took as a No.

A sudden chill ran down his spine and Lockwood ducked, just in time to avoid the Spectre's hand reaching for his back. He brandished his rapier again, but it caught only empty air. A gunshot fired close to his ear and he flinched, almost running into the ghostly fire still ringing the ship.

It was messing with him. He hated it when ghosts did that.

"Any time now, Lucy!"

She shouted something largely incomprehensible, but what he suspected was a Northern way of saying, Leave me alone, I'm going as fast as I can! He couldn't help but smile.

The Spectre screamed again and, before he could track where it came from, it burst out of the deck in front of him. He scrambled to get away, but his heel caught on the fallen beam and Lockwood crashed onto the deck, white stars briefly shattering over his vision. The Spectre loomed above him, maw gaping, long, cracked fingernails at the ends of its outstretched hands, organs trailing and dripping blood. And that dark heart still pulsing in its chest.

Fear finally dug its claws into him. He couldn't move. He called Lucy's name one more time.

You can take me, he thought, as he stared into the Spectre's burning white eyes, if you don't hurt Lucy.

It lunged for him and then abruptly vanished. The fire snapped out. Green afterimages floated over his sight, overlapping each other in the dark as he tried to blink them away. He knew the ghost had to be gone because the sinking cold had gone too, but his eyes weren't so sure yet.

"Lockwood!"

Lucy's voice jolted him into motion. He found her there beside him when he sat up. Spiderwebs caught in her hair, glinting faintly like silver lace under the moon.

"Are you hurt at all?" She touched the back of his head and he had to contain a wince as her hand found a sore spot.

"Did you find the Source?" he asked.

She raised up the silver net for him to see, an old bullet secured inside. He smiled at her. Lucy's mouth stayed in a stubborn downward curve.

"Lovely," he said, hauling himself to his feet. "Then let's get out of here before anything else tries to kill us." He offered a hand to Lucy, but she ignored him.

"Where are we anyway?" she grumbled as she walked off the ship.

He followed and said, "Kensington Gardens."

She turned suddenly toward him, still walking through the darkness with him. "That's a real place?"

"What do you mean? Of course it's a real place."

"I don't know!" she huffed. "It's where Peter Pan was from, innit? It's like saying Neverland's a real place."

"How do you know it's not?" He could tell by the expression on her face—a healthy mix of annoyance and disappointment—that his smile had turned into a teasing one, but he couldn't help it. "Look up there, Luce." He raised his hand towards the sky at two points of light that could still be seen even in the hazy London night. "Second star to the right and straight on til morning."

Lucy looked up and allowed a wry smile to cross her face. "Those aren't stars. That's Jupiter and Saturn."

He blinked, turning quickly back to her. "Wouldn't've taken you as a stargazer, Luce."

"I'm not. My sister was—still is, I suppose, I don't know."

"You have a sister?"

"Six of them."

"Oh."

They reached the sidewalk ringing the park and Lockwood led the way back towards Marylebone. The silence slowly ate away at him, tension between them like a badly tuned violin string. He remembered that they were only out here because she was stubborn and infuriating and should've known better, and really he ought to tell her off for it. Or maybe he ought to apologize for upsetting her enough that she'd preferred her chances with the ghosts. But they'd worked so well together just now. And he'd gotten her to smile, if for a little while. He didn't want to ruin it by dredging up hurt feelings.

Lockwood cleared his throat. "You were brilliant, by the way, Luce… just now, with the, uh, pirate ghost."

"Yes, I'm quite the asset, aren't I?" she said, cold as creeping fear. "Makes you think twice about firing me. But I'll save you the trouble. I'm quitting tomorrow."

"What? I didn't… What makes you think I would fire you? You're—"

"Because I'm difficult, aren't I? I listen to ghosts more than I listen to you? Shut up and do your job, isn't that right?"

"Lucy." Pain cracked his voice a bit and he hated that, but he hated the pain in Lucy's voice even more—and all because of him. "There's clearly been some sort of misunderstanding."

She laughed, sharp and without humor, and suddenly stood rooted on the sidewalk. He had to turn fast around to face her. "Funny, that," she said. "Because you don't understand anything, do you?"

"Lucy, please, let's talk about this at home. It's far too dangerous—"

"I am drowning, Lockwood!" Her eyes reflected the light of a nearby ghostlamp, tears gathering and threatening to fall. "But you're just like everyone back home, you don't care as long as it makes you a bit of money or gets you on TV."

"Of course, I care. I'm sorry about all that, but I—"

"And you know, maybe I…" She took a breath that seemed to tear through her lungs. "Maybe I shouldn't've come to London, maybe I ought to've just died with everyone else. God—" She buried her head in her hands, nails digging into her skin. "I wish I'd died with everyone else."

Lockwood could almost hear his chest cracking open in pain for her. He had the same urge to hold her close and keep her safe that he felt on cases, but he knew he couldn't fight off thoughts with a rapier. He knew. He'd been right where she was more times than he cared to remember.

He took a steady breath. "I understand that," he said gently.

Lucy lowered her hands cautiously and met his eyes again. Please, believe me, he thought.

"And it's not true, Lucy. We need you. And it's not because you're an asset."

She watched him in silent challenge. "Why then?"

"Because…" He had to get this right, but how could he possibly explain without gutting himself? "Because you're…" He knew what he wanted to say, but it was far too soon for that. "You're Lucy Carlyle," he said, trying to put every marvelous thing about her into her name so she could hear it. "And that's more than enough."

She shook her head, but not in disbelief, in sadness. "Barnes knows I'm illegal."

Now, Lockwood could smile. He let himself step nearer to her. "That's why I went on TV, silly. To show Barnes he can shove his threats. That I wasn't going to let you go without a fight."

Lucy laughed faintly. "Pretty sure there's rules about that."

"Screw the rules." He smiled. And then quite without thinking, his hand stole out to settle around hers and he didn't realize he'd done it until she'd grasped his hand. His heartbeat spiked in slight distress, but it was too late now. "I'm sorry, Lucy," he said. "Please stay."

She looked serious again, but she was nodding slightly. "Just never lie to me again."

Light flickered somewhere behind Lucy, figures slowly creeping this way, and he remembered exactly where they were.

"I'll never lie to you again. I swear." He flashed one more grin. "And in the spirit of that, you ought to know we're standing right by Tyburn Gallows." He nodded at the ghosts behind her.

"So?" she asked as she turned. And then Lucy saw them too. "Oh, shit."

"Well, it is the most haunted place in London." Without letting go of her hand, he grabbed a salt bomb off his belt. "Pull this pin for me, will you, Luce?"

She did and he hurled it as far into the trees as he could manage. Together, they turned and ran across the street away from the park, listening to the cries of outrage behind them as the bomb went off.

"I suppose I should thank you for finding me," Lucy said, running beside him.

"You didn't make it easy. You know, you're rather more of a liability than an asset, Luce."

As they turned a corner, he glanced over at her and caught her small but honest smile.

#outing myself as a peter pan nerd#i'm proud of this one#lockwood & co#lockwood and co#lockwood#anthony lockwood#lucy carlyle#george karim#locklyle#The Hidden Archive

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ballads of the Hanged: Swinging from the Gallows Tree

A mixtape of execution ballads and assorted tales of guilt, wrath, terror, and defiance on the gallows, where all men are brothers.

[on spotify]

21 tracks, 1h 15min in full (spotify lacks one song)

I teased this many moons ago, and I finally finished it. No booklet in PDF form (too much hassle), but I got extensive liner notes, which you can also read here, for more pictures and a wider format. Enjoy!

LINER NOTES

1. Hans Zimmer - Hoist The Colours

Heave ho thieves and beggars never shall we die

What a heartbreaking thing to say on the scaffold. But we have to start with theatrics and a drum roll, and our introduction needs no introduction.

2007, from Pirates of the Caribbean: At World's End OST lyrics: Ted Elliott & Terry Rossio music: Hans Zimmer & Gore Verbinski

2. Shirley Collins - Tyburn Tree (Since Laws Were Made)

Next stop, Tyburn: England's most notorious gallows. In The Beggar's Opera, the highwayman Macheath (later also known as Mack the Knife) observes that if they hanged rich criminals like they hang the poor ones, "'twould thin the land". Shirley Jackson subtly changed this to the better.

Since laws were made for ev'ry degree to curb vice in others as well as me, I wonder there's no better company on Tyburn Tree.

But since gold from laws can take out the sting, and if rich men like us were to swing, it would rid the land their numbers to see upon Tyburn Tree.

recorded 1966, released 2002 in Within Sound lyrics: John Gay, from The Beggar's Opera, 1728 music: traditional ("Greensleeves"), 16th century

3. Joan Baez - Long Black Veil

A country ballad about a man falsely accused of murder, who lets himself get dragged to the gallows because he won't reveal his alibi: an affair with his best friend's wife. It's been covered by a million people, here's Baez live.

The scaffold is high, eternity near, She stands in the crowd, she sheds not a tear, But sometimes at night, when the cold winds moan, In a long black veil she cries o'er my bones.

1963, from In Concert Part 2 lyrics & music: Lefty Frizzell, 1959

4. Oscar Isaac with Punch Brothers & Secret Sisters - Hang Me, Oh Hang Me

A poor boy who got "so damn hungry he could hide behind a straw", made his last stand with a rifle and a dagger, and has been all around this world, and is positively done with it.

They put the rope around my neck, they hung me up so high Last words I heard 'em say, won't be long now 'fore you die Hand me, oh hang me, and I'll be dead and gone Wouldn't mind the hanging, but the laying in the grave so long

2015, from Another Day, Another Time: Celebrating the Music of "Inside Llewyn Davis", after Oscar Isaac's rendition in Inside Llewyn Davis, 2013, in turn after Dave Van Ronk's rendition in Folksinger, 1962 lyrics & music: traditional American/unclear origin, folk song with various titles (I've Been All Around This World, The Gambler, My Father Was a Gambler, The New Railroad), first recorded by Justis Begley, 1937

5. Chapel Hill - Seven Curses

Cover of a Bob Dylan song, telling us the dark tale of a judge who's about to send a man to the gallows for stealing a horse, promises his daughter he'll show clemency if she agrees to sleep with him, and then reneges on his promise.

The next morning she had awoken to know that the judge had never spoken she saw that hanging branch a-bending she saw her father's body broken These be seven curses for a judge so cruel

2013, from One For The Birds lyrics inspired by Judy Collins's "Anathea" (1963), in turn inspired by the traditional Hungarian ballad "Feher Anna", who curses the judge "thirteen years may be lie bleeding" lyrics & music: Bob Dylan, recorded 1963, released 1991 in The Bootleg Series

6. Ewan MacColl - Go Down Ye Murderers

A song about Timothy Evans, a man accused of murdering his wife and child, which he denied until his last breath. They convicted him and hanged him in 1950. He was 25 years old. Three years later the real murderer, his neighbour John Christie, confessed, and the case played a major role in abolishing capital punishment in the UK.

The rope was fixed around his neck, and the washer behind his ear And the prison bell was tolling but Tim Evans did not hear Sayin' go down, you murderer, go down

They sent Tim Evans to the drop for a crime he didn't do It was Christy was the murderer, and the judge and jury too Sayin' go down, you murderers, go down

1956, from Bad Lads and Hard Cases: British Ballads Of Crime And Criminals lyrics & music: Ewan MacColl

7. Jennifer Lawrence - The Hanging Tree

One of the stranger things that can happen at the hanging tree is camaraderie. "On the gallows tree, all men are brothers", to quote A Feast for Crows, and when the state murders, then in defiance, an execution ballad can become a protest song. Many have in real life, this one is fiction, from The Hunger Games. Wisely, the director asked the composer for a simple tune, nothing elaborate, something that could be "sung by one person or by a thousand people".

Are you, are you coming to the tree? Wear a necklace of rope side by side with me Strange things have happened here, no stranger would it be If we met at midnight in the hanging tree

2014, from The Hunger Games: Mockingjay – Part 1 OST lyrics: Suzanne Collins music: James Newton Howard

8. Let's Play Dead - Heaven and Hell

A fairly traditional execution ballad written recently for the series Harlots. Margaret Wells sings it to herself for consolation and courage, as she sits alone in a cell, waiting to get dragged to the gallows.

I'm no more a sinner than any man here I'm no less a saint than the priest at god's ear But now I am snared, they will punish me well With a ladder to heaven and a rope down to hell

2018, from the single Heaven and Hell, for Harlots Season 2 Episode 7 lyrics & music: Let's Play Dead

9. Odetta - Gallows Pole

Probably the most well-known execution ballad of the 20th century, thanks to several iconic renditions. This one remains my favourite.

Hangman, hangman, slack your rope, slack it for a while I think I see my father coming, riding many a mile Papa did you bring me silver, did you bring me gold? Or did you come to see me hanging by the gallows pole?

1960, from At Carnegie Hall lyrics & music: traditional (Child 95 / Roud 144), known under many other titles ("Hangman", "The Maid freed From the Gallows", "The Prickle-Holly Bush"); this version is directly influenced by Lead Belly's "Gallis Pole" (1930s), and they both informed Led Zeppelin's 1970 version

10. Johnny Cash - 25 Minutes to Go

Peak gallows humour, uproariously funny and defiant, and somehow still conveying the terror of a man who's about to die and emphatically doesn't want to. Performed live at Folsom Prison.

Then the sheriff said boy I'm gonna watch you die, 19 minutes to go So I laughed in his face and I spit in his eye, 18 minutes to go Now here comes the preacher for to save my soul, 13 minutes to go And he's talking about burning but I'm so cold, 12 minutes to go

1968, from At Folsom Prison lyrics & music: Shel Silverstein, from his 1962 album Inside Folk Songs

11. Johnny Cash - Sam Hall

A classic execution ballad with many versions (see here for its complicated history), some of which are stoic and dignified, and others humorous. But this one brims with rage. Sam Hall will not be repenting on the gallows, and he'll see you all in hell.

My name it is Sam Hall and I hate you one and all And I hate you one and all, damn your eyes

2002, from American IV: The Man Comes Around lyrics & music: : traditional, 18th century broadside ballad, Roud 369

12. Nick Cave & The Bad Seeds - Up Jumped the Devil

A song about a man doomed from the start to play the villain’s part, and the origin of this blog’s #swinging from the gallows tree tag.

Who's that hanging from the gallow tree? His eyes are hollow but he looks like me Who's that swinging from the gallow tree? Up jumped the Devil and he took my soul from me

1999, from Tender Prey lyrics: Nick Cave music: Nick Cave & The Bad Seeds

13. NOT ON SPOTIFY: Dead Rat Orchestra - The Black Procession

This ballad imagines a sinister procession of 20 criminals (black tradesmen brought up in hell!), each with their own specialty (it's mostly thieves of some sort), on the way to the gallows. The last and worst of them is the thief-catcher, and if one of them is innocent, they'll all go free. But of course none of them are. It's written in thieves' cant (lyrics and more context here), and the chorus means: "Look well, listen well, see where they are dragged, up to the gallows where they are hanged."

Toure you well; hark you well, see where they are rubb’d, Up to the nubbing cheat where they are nubb’d.

2015, from Tyburnia: A Radical History Of 600 Years Of Public Execution lyrics: from The Triumph of Wit by J. Shirley, 1688 music: Robin Alderton, Daniel Merrill & Nathaniel Robin Mann

14. John Harle & Marc Almond - The Tyburn Tree

And where does the Black Procession lead? To Tyburn, of course. The dark gothic side of Marc Almond.

The Tyburn Tree, I weep for thee, blood in the roots 'Tis not a tree with bark and leaves of spring awakening 'Tis not a tree with blossom and fruit, 'tis not a tree No boughs to bend beneath the unruly breath of winter No memories of woods warmed by spring's sweet touch 'Tis not a tree — take a ride to Tyburn and dance the last jig

2014, from The Tyburn Tree (Dark London) lyrics: Marc Almond music: John Harle

15. CocoRosie - Gallows

Speaking of dark and gothic.

They took him to the gallows, he fought them all the way though And when they asked us how we knew his name We died just before him, our eyes are in the flowers Our hands are in the branches, our voices in the breezes And our screaming is in his screaming

2010, from Grey Oceans lyrics & music: Sierra Rose Casady & Bianca Leilani Casady

16. The Tiger Lillies - Hang Tomorrow

In their Two Penny Opera, the pioneers of dark cabaret reimagine Brecht’s Threepenny Opera, and take all the suaveness out of Mack the Knife. Here they also take all the fight out of him. What's even left? A pathetic empty husk, a bastard (let's not forget that Brecht's MacHeath is no rogue with a heart of gold, he's a horrible man) who can't even be intriguing. How disturbingly pedestrian.

So here I am in jail again, oh god it stinks of piss I've been in here since I was young, so I can reminisce It's looking rather grim this time, it's looking rather bad But if I swing tomorrow in some ways I'll be glad

2001, from Two Penny Opera lyrics & music: Martyn Jacques

17. Tom Hollander - Ballad In Which MacHeath Begs All Mens' Forgiveness

In The Threepenny Opera, Mack the Knife stands on the scaffold and asks for pity. No point being judgmental now, that he's about to die. He morbidly describes how his dead body will end up, and then he lashes out at everyone, cops and criminals (same difference), while still begging them all for forgiveness. Very VERY sarcastically. The ballad's concept is borrowed from François Villon (see below), and this translation is unusually bold (honorific, see here and here for other translations and context).

You crooked cops with your Mercedes, your mobile phones, your trendy jackets, your cuts from drugs and dice and ladies, your Scotland Yard protection rackets.

Let heaven smash your fucking faces, slash you and let the blood run free and break you in a thousand places. I've pardoned you. You pardon me.

1994, from The Threepenny Opera - Donmar Warehouse Original Cast lyrics: Bertolt Brecht 1928, loosely inspired by François Villon's "Ballad of the Hanged" c. 1489, translated by Jeremy Sams 1994 music: Kurt Weill 1928

18. Saga de Ragnar Lodbrock - Ballade des pendus

And here's the OG Ballad of the Hanged, written in the 15th century by the OG poète maudit, François Villon (translation here). It paints an indelible picture of strung up corpses swaying in the wind, decaying, pecked by birds, ravaged by the elements and time. And crucially, it's in the first person. The hanged speak, begging their fellow-humans for pity, and god for forgiveness.

Frères humains, qui après nous vivez, N'ayez les c��urs contre nous endurcis, Car, si pitié de nous pauvres avez, Dieu en aura plus tôt de vous mercis. Vous nous voyez ci attachés, cinq, six: Quant à la chair, que trop avons nourrie, Elle est piéça dévorée et pourrie, Et nous, les os, devenons cendre et poudre. De notre mal personne ne s'en rie; Mais priez Dieu que tous nous veuille absoudre!

recorded 1979, released 1999 in the Saga de Ragnar Lodbrock reissue lyrics: François Villon, c. 1489 music: Saga de Ragnar Lodbrock

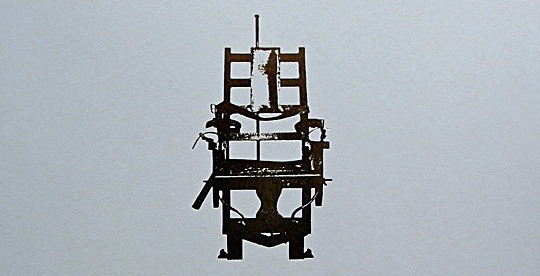

19. Nick Cave & The Bad Seeds - The Mercy Seat

Honorary inclusion, a song not about hanging: the mercy seat is the electric chair. But the lyrics are a punch and this is a torrent of a song, a whirlwind, a masterpiece, a 7-minute cynic snarl. So it couldn't possibly get left out of this compilation.

And the mercy seat is awaiting, and I think my head is burning And in a way I'm yearning to be done with all this measuring of proof An eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth (a life for a life and a truth for a truth) And anyway I told the truth, and I'm not afraid to die (and I'm afraid I told a lie)

1999, from Tender Prey lyrics & music: Nick Cave

20. Graveyard Train - Ballad For Beelzebub

And after? Welcome to Hell, ladies and gents, and bards. (Bards are rogues, too.) The Graveyard Train play a kind of Southern Gothic (but very southern, they're Australian), and here they entertain the thought of a band that ends up in hell and has to keep playing, without end, for an audience that can't hear. What a bleak prospect.

Well the air on the stage is burning our lungs And we're all going deaf from the beating drums And you can't see a thing for all the blood and the sweat in our eyes

Well we played till we died, and now we're all dead But the Man says we got to get up there again And you can't come down till the brimstone turns to ice

2008, from The Serpent And The Crow lyrics & music: Graveyard Train

21. Samuel Kim feat. Colm R. McGuinness - Hoist the Colours

Yo ho, all together Hoist the colours high Heave ho, thieves and beggars

But we won't end in hell. The only acceptable ending to this compilation is the triumphant version (wait for it) of its beginning: a pirate's end. Traditionally the gibbet, yes, but also the ghost ship that still sails, the ripple that still travels, and the story that still gets told.

Did I stutter the first time?

NEVER SHALL WE DIE

#long post#swinging from the gallows tree#mixtape#trs#prison ballads#pirate#bard#The Threepenny Opera

80 notes

·

View notes

Text

on the metaphysics of current and old genii locorum of rivers (in Rivers of London)

With Yuletide reveals I can finally talk about the worldbuilding behind the story I wrote for my assignment. It's an E-rated smut fic about Peter, Beverley, and Old Beverley Brook. (Here's the link to my post about the story itself, so you can check it out and decide for yourself if it's something you'd want to read.)

In order to do smutty worldbuilding with these characters, I had to build a headcanon about how the connection between Beverley and Old Beverley works in general. So here are my thoughts about that.

There is some kind of connection between the current Rivers and their dead counterparts. Old Sir Tyburn has opinions about Lady Ty and vice versa, and Old Beverley Brook clearly knows (about) Peter in some capacity – after all, his first act after meeting him is to full on kiss him on the mouth. So what is this connection? The animosity between Ty and Old Tyburn suggests that they definitely aren’t the same entity. The kiss suggests that they can share information and possibly even experiences.

There are at least two ways to interpret the interaction between Peter and Old Beverley in Lies Sleeping: 1. (present-day) Beverley is acting through Old Beverley. His words („babes“, which is supposedly how Bev would call Peter) and the kiss itself seem to suggest that. 2. He is his own entity who acts on his own, which is what his knowledge about the other ghosts on that plane of existence seems to suggest.

The doylist explanation is probably „whatever Ben Aaronovitch needs to make the scene work“, and honestly, that was my approach too for making the sex scene work. But in-universe, I assume it works like this:

The ghosts of the old genii locorum are separate entities from the present day genii locorum. On a very basic level, the only connection they share is towards their river. The ghosts of the old rivers are images of the persons they used to be, and as such don’t have necessarily much in common with today’s Rivers. Sometimes they are lucky and have enough in common to have an amicable relationship (like I decided for Beverley), and sometimes they are unlucky and don’t really like each other (like Tyburn). That’s not to say they are enemies – they still have that connection through their river, and either Sir Tyburn was willing, or Lady Ty compelled him, to put his sword through the would-be assassin in The Hanging Tree. Luckily I didn’t need to make a decision on that, because I focused on Beverley.

I decided that there has to be a lot of fluidity in how such a connection can work. My initial idea of describing it was like looking through a window. At first the shutters are closed and you (as a modern day River spirit) perhaps don’t even realise that there’s a window. Than you realise that there is a window, and you can look through it into the other world. That’s how I imagine the connection in daily life – a window you can ignore, or look through, or even close, and depending on how much focus you put on it, it’s clear glass, or milky glass, or the window is … I don’t know, in a different place of your house depending on how much attention you pay it? The metaphor doesn’t work really well at this point, which is why I abandoned it, but my point is, I imagine there are a lot of ways the connection can work, depending on the individual character and relationship of the genii locorum involved. And, to get back to that heavy metaphor one last time, in rare cases such as Sir Tyburn’s sword and the assassin, you don’t just have a window, but can open a door and let the other one through. Or, in the case of Peter’s sacrifice to Lady Ty in her underground river, she can push him through. The same way of pushing someone else into that world is what I imagine Beverley did with Peter in my story. And how much energy it takes would depend on how well the connection usually is, so it would have a noticeable cost for Tyburn, but be easy as breathing for Beverley.

I decided that there could be some overlap in experiences and sensations, but again, not set in stone. So I decided that usually, Old Beverley doesn’t play much of a role in Beverley’s life. She has a busy life after all. Usually, the connection is more like the background radiation of everything that connects her to her river. Definitely present, but not like she talks to him or constantly feels his presence. Only when she focuses on him she would be actively in contact with him, and when she focuses on him even more and gets more into his world, she could herself immerse in it, and I stretched that so far that she can feel what it is to be in his place. But at the same time, she is in control of that, being the currently alive and powerful genius loci of her River.

For the mechanics of Peter being in that world:

There are several instances in the books when that happened. First in Whispers Underground, when he’s buried underneath the platform at Oxford station, near where the river Tyburn flows. He’s slowly running out of air, that is, he’s in the process of dying in the ‚real‘ world and Sir Tyburn draws him into his ghost world – to make it easier on him, because the sensations there are different. To distract him, give him (metaphorical) air to breathe, and perhaps out of curiosity; he says he’s been lonely there for a long time. He knows about Peter, at least his name and where he’s from. Meanwhile, Lady Ty learned about Peter’s whereabouts by, as she says, smelling him in her water. It’s unclear how much time passes in each place. (On a side note: it’s this meeting in which Sir Tyburn makes Peter aware of Punch’s wailing as he’s pinned to the bridge, and says that sooner or later Peter has to let Punch loose. Props to that bit of foreshadowing.)

I don’t quite remember any other times in between that Peter is in this world, but at the time in Lies Sleeping when Peter has his Game of Thrones episode, he’s falling from St. Paul’s bell tower towards what could well be his death, and time definitely passes differently in this other world, because in under 2 seconds, there’s a whole two chapters of stuff happening; a race through ancient London and a fight and a conversation, so there’s some time weirdness happening.

Then there’s the time when Peter makes his sacrifice to Lady Ty because he wants to ask her to send him into this world. While he’s in the world doing his things, his body is in Lady Ty’s river, I assume unconscious, and he doesn’t get out on his own but has to be saved by others. I think the implication is that being in this ghost world means that his body is unconscious or sleeping – suddenly as it comes, I imagine it’s closer to unconsciousness, but it’s not like we have any data. Peter would really have to get hooked up to an EEG to record his brain waves during sleep and during this.

Admittedly, it is a stretch to go from there to „being in this world means that Peter is slowly suffocating in our world“ which I used for dramatic purposes in my fanfic, so that’s definitely not worldbuilding I would extrapolate from what we know in canon. It’s an extension though, one that I don’t think contradicts canon.

Anyway, all of that was very interesting to think about, but I didn’t dare to openly talk about it lest someone connected the secret story to me xD Perhaps I was taking it too far, but I thought it would be suspicious if I was going from my usually near zero meta discussion posts to talking about this topic right when the Yuletide assignments went out.

This whole thing is very much not a meta analysis, but a meta interpretation, since I mainly thought it through in terms of „how can I write the story I want to write and I think my recipient is going to like“, so there are many arguments to be made that it can (or should) work differently if you’re following the canon closely, or want to just extrapolate instead of interpret.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

sweetbitterbitten:

the banished boleyn bites the flesh of her inner cheek, half bent over the back of a stately chair; light hands clenched upon it like a preacher his precious, immutable pulpit; brow furrowed in fortified thought. so grappling is her grasp that the wood, in protest, groans and creaks, a macabre mimicry of the twisting vines of tyburn tree. she cannot help the witnessing of all wrong which has worked rightly in her favor. for her relinquishing of a heart that harbored equal attention and affection elsewhere - here she stood in stead for kin which could not. her willingness to walk away, the enchantment which achieved her continued existence. her acceptance, an alleviation of a brutal end. "which claim do you attest might reprieve her? there appear to be three in contention." the crown. the king. and her daughter's legacy.

mary thinks she can bargain with the devil (isn't that how they think of him, from white hall to the holy see? anti-christ in the flesh, harbinger of doom; maybe he is, for others, for enemies...). if only he were. for her, he would make a deal. but he is only mephistopheles, a lower imp, made messenger for his master. not even that; this is back alley back talk, that he might see what curse they can dispel, that they might bring the remnants of dark ash to the king and see if he'll accept the proposol of one of his own. mary asks innocently. oh, he believes she means it so, rather than to torture him by correcting her. because he knows what the answer is, knows that henry will never accepting anything less than all. that is the divine right of kings. "the three," he answers, breathing out the executioner's terms and the savior's salvation. katherine had not escaped to the peace she might have earned if she'd only given up what he'd asked. henry will not bargain for any less than what he had asked from his rightful queen. "this is not the time for her to coy about negotiations," he warns her, knowing anne will want to claw for every inch, risking her last breaths. "you must convince her, mary."

1 note

·

View note