#They were invented during the American Civil War as far as the concept we know today.

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

I'm a couple chapters from writing it...

But fucking crying over the idea I had of Emmrich giving Mourn Watch Rook a proto-dogtag because they're worried about dying outside of Nevarra and having no agency over their body. It basically says 'do not cremate' in a few languages and MW Rook's fucking destroyed by such a considerate gift. They wipe their eyes and smile and ask Emmrich: "Hey can I see yours?"

#AND HE DOES NOT HAVE ONE BECAUSE GDI EMMRICH#YOU WORK IN DEATH CARE YOU NEED A DISPOSITION PLAN#emmrich volkarin#Mourn Watch#Dragon Age#da:tv#Sure some bright spark invented dog tags in Thedas#They were invented during the American Civil War as far as the concept we know today.

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

I HAVE A SOLUTION.

In my fics where the Anti-Ecto Acts are a thing, they're not new at all! They're old. Like they date back to the Spiritualism movement and the periods immediately before, during, and after the American Civil War.

Real IRL history: Many of the Spiritualists, the people doing séances and shit, were various flavors of leftist (by the standards of the time). Lots of abolitionists and communists and such. The word "ectoplasm" was coined in 1894 by a French researcher named Richet, who more or less invented the modern concept of anaphylaxis and also led the French Eugenics Society. He proposed that ectoplasm was a substance that mediums extrude from their bodies that allows spirits to interact with and be perceived by normal people.

Now, let's propose that in the Danny Phantom universe, ectoplasm is a real thing that could be isolated as a substance in the 1800s. Let's also say that ectoplasm was discovered a bit earlier than IRL, say, in the Antebellum period. Say you're a governor in a slave state, and you're sick and tired of these damn mediums suggesting that maybe slavery is bad, so you decide you want to pass a law banning mediumship. Maybe you ban mediumship entirely, maybe you go more specific and ban the production and possession of ectoplasm because you wanna sound all modern and shit. Well, then the Civil War happens and it's the deadliest war in history thus far and everybody and their cousin is mourning someone and so everybody gets REALLY INTO SÉANCES. And maybe, since ectoplasm is a demonstrably real thing and séances work when led by the right person, some disgruntled Confederate sore losers get the bright idea to try summoning the spirits of their dead comrades to do the war over again, because you can't kill a soldier that's already dead, now can you? Meanwhile, the Secret Service is deciding that they're not just the counterfeiting guys, they're also the Presidential bodyguards. And the Secret Service hears about this dastardly plot and, since they're still in the midst of figuring out what their deal is as a government agency, they decide "preventing ghost Civil War" can also be part of their jurisdiction, and the principles of the anti-ecto acts are included in the act that updates the Secret Service's responsibilities.

Well that's all well and good, but ectoplasm is hard to study and mediums are rare, so all of this slides into the trash heap of history along with laws about how you can't picnic in the graveyard on Sundays and other silly old-timey things. The only people who really know about this are the Secret Service agents of the Ghost and Inexplicables Wing, who focus their efforts on the mediums that are either threatening to cause social change or an actual necromantic apocalypse. Mostly the first category. Necromancy is hard.

...Well, it fades into history right up until the Cold War. The CIA is really worried about the Soviets figuring out remote viewing and they wanna do human experimentation about it, but they need an excuse to make it slightly legal. Some brilliant mind notices that the Secret Service is supposed to be in charge of ghost hunting, and also hunting any human who makes ectoplasm. So the CIA, now also worried about ghost Soviets, hits up the Secret Service like "yo, you wanna make a joint ghostbusting agency?" And the Secret Service is like "yeah but you gotta keep quiet about it we don't want the President's psychic to know we're watching her" and the CIA is like "hell yeah". And that's how the GIW evolves into the suit-wearing doers of very painful experiments that we see in the show.

The GIW is a classified joint project of the Secret Service and the CIA, and the shit it gets up to isn't actually THAT secret, it's just that it all gets written off with other kooky historical laws and weird unethical bullshit that the CIA gets up to. And this is perfectly convenient for the GIW; the CIA can say "no really guys, we got the human experimentation stuff out of our system with MK Ultra, there's no ghosts or aliens or anything like that, just totally normal human spy stuff :)"

(Meanwhile, at Area 51, the ghosts of the aliens that crash landed in Roswell would like to go home now please.)

The anti-ecto acts confuse me so much. How do they even work? How were they passed? How on earth do the remain a secret?

They’re acts, so they had to have been passed by congress. You’re telling me a minimum of 543 people learned about the existence of ghosts and nobody said anything about it? Be real.

543 congresspeople, plus their aids and secretaries and families? That information leaks fast, if not before the act passes then definitely afterwards. And once somebody says something it won’t go ignored by the general public. The US government just admitted ghosts are real? That’s getting national news coverage even if it was bunk.

Laws are public works. They aren’t sealed documents, literally anyone is allowed to look at them.

Also there’s the matter of enforcing them. Who are the GIW? A branch of the FBI? The military? The acts probably outline methods of enforcing them, which means even if they aren’t brought up by name whatever department they work for has to be mentioned.

A law gets passed allowing private military contractors to open fire on US civilians on US soil? Even if it specifies nonlethal force (assuming ecto-weapons don’t hurt humans) and even if they work around the civilian problem by renouncing ecto-entities as us citizens…

They’re still going to catch massive flack for using unknown chemicals in densely populated civilian areas. Humanitarian and Environmentalist groups will be all over this shit so fast.

Anyway I’m running out of steam, but I’m basically convinced that codifying the anti-ecto acts into law is the stupidest thing the GIW could’ve done. Because yeah now you have power, but now everyone knows what you’ve been doing and you’re under official scrutiny. They should’ve just done what the government always does - act without telling anyone and then deny deny deny when people rightly accuse you.

241 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fatman: Why Mel Gibson Found Christmas Spirit at the End of a Gun

https://ift.tt/3evPPz5

Sometimes you find the Spirit of Christmas in the strangest of places. For brothers Eshom and Ian Nelms, it was at an awards season screening of Hacksaw Ridge in December 2016. The pair had already been dreaming of Fatman and its desperado Santa Claus for more than a decade when they attended the event. But they weren’t there that night for Santa; they came for a Q&A with Mel Gibson, the mercurial filmmaker who seemed to be on the cusp of reconciliation with Hollywood.

Arriving to his own screening renewed and happy, and with a bushy gray beard worthy of Methuselah, Gibson could still make a hell of an impression, both on an industry impressed by his World War II drama and the two young filmmakers with eyes due North.

“Gibson came out and he had this amazing beard,” Ian recalls over a Zoom interview, still with a twinkle in his eye. “He was a little slumped over and kneading his beard, very passionately talking to the audience about what he was excited about in the film and why he made it. But he also was right at the end of that award circuit, and you could see that he was a little worn out… you could see the wear and tear on him [and] a guy that was little beaten down at that point. We instantly looked at each other and we’re like, ‘That’s the guy.”

They were ready to shout that’s our Santa!

It’s an unusual origin story for a Christmas movie, but then Fatman isn’t your child’s new Netflix Christmas darling. Starring Gibson as an aged and broken man who is clinging on to the last vestiges of hope for a better tomorrow, Fatman seeks to ground Father Christmas with the same dispirited nihilism that James Mangold applied to Wolverine a few years ago in Logan. Both movies are ostensibly Westerns, informed by the deconstructionist streak of Clint Eastwood’s Unforgiven, and both end in a bloodbath.

Yet whereas Unforgiven is the story of a cowboy, and Logan a clawed antihero, Fatman is about Santa existing in a world where hitmen like Walton Goggins’ “Skinny Man” come out of the woodwork, eager to claim his scalp. However, if you sit down and ask the Nelms about this somber approach to the character, it makes perfect sense in the early 21st century.

“When we were doing some of the research and finding out how much money the holiday season really drives our economy, it’s amazing, right?” Eshom says. “You can see why that engine was created.”

Indeed, according to the World Economic Forum, Americans alone spend more than $1 trillion a year on holiday retail. And that doesn’t even consider how much more is spent on holiday festivities, public events, and travel.

“I mean, Rudolph, which now seems to be a staple of Christmas, was actually an invention of [retailer] Montgomery Ward’s back in the day,” Ian says. “That’s a marketing ploy. Rudolph doesn’t exist!”

This cold economic reality informs the brothers’ approach to Santa. Other than his genuinely sweet partnership with Ruth (Marianne Jean-Baptiste), aka Mrs. Claus, Gibson’s Chris Kringle is despondent and cynical about the world today. It’s why he allowed his operation to become subsidized by the U.S. government, which in turn wants to prop up the American economy but is as oblivious about the Spirit of Christmas as the little boy (Chance Hurtsfield) who puts a bounty on Santa’s head after receiving a lump of coal on Dec. 25.

It’s an unorthodox take, and one the Nelms’ have been working on for the better part of 20 years. The pair tell us that the concept first came to them in 2003, fortuitously around the same time they bought their first DVDs: Unforgiven for Ian and Unbreakable for Eshom.

“This sort of superhero-Western mashup was, I think, a big catalyst for the film,” Eshom notes, particularly appreciating how grounded and stealthy the superheroics were in M. Night Shyamalan’s Unbreakable. Their premise also fit into each brother’s preference for niche “alternative Christmas movies.” As a pair more inclined to enjoy Kiss Kiss Bang Bang or Gremlins during the holidays, not to mention the Gibson-starring Lethal Weapon, they saw an opportunity to make a unique genre-bender.

However, real movement on Fatman didn’t start until the Nelms began getting their foot in the industry in 2006, and they’ve been refining the idea ever since.

“We always wanted him to be an everyman,” Eshom says about the creative process. “We wanted [Chris and Ruth] to be really relatable and have a lot of what people would consider blue collar problems.”

As the sons of small business owners, the Nelms were able to understand that dynamic intimately, even if the stakes they saw growing up were never over the soul of Christmas.

Says Ian, “[Our parents] owned a photography business for 20 some odd years, and our mom was very much the Ruth. She was the backbone of that business, and he was very much the Chris, where he was the lead photographer. She was an amazing photographer in her own right, but he was the lead photographer and the business had his name on it, and he started it before he even met our mom. But he wouldn’t have lasted five seconds without our mom, because she really held that thing together. Even though he was a great photographer, the logistics eluded him, completely.”

That dynamic informs much of Fatman, which ended up being the Nelms’ fourth feature film. The movie is accurately marketed on the grizzled violence that eventually puts Goggins’ Skinny Man on the opposite end of a snow bank from Gibson’s Kringle. The slender one bellows, “I’ve come for your head, Fatman!” But the film surprisingly plays its absurdities straight, not least of all because of Gibson and Jean-Baptiste’s affection.

It’s one element the brothers emphasized to Gibson when they finally got in a room with the filmmaker to pitch the project; another was how stripped down and crusty their vision of Santa would be.

“The pictures that we were showing him were these pictures of these old trappers, and these guys who were visiting Antarctica in the early 1900s and they were on dog sleds,” Ian says. “We were… really bringing it back to a place of when this guy got started. Maybe the jacket is real leather and that’s real animal fur? It’s like it goes back to a time when he was originated, and we felt like that jacket had been upgraded for hundreds of years with Ruth stitching it up.”

Read more

Movies

20 Christmas Movies for Badasses

By Michael Reed

Movies

The 20 Best Christmas Horror Movies

By Elizabeth Rayne and 4 others

It clearly wasn’t Tim Allen’s Santa Claus, but that was the point. They expressly pitched that point to the star they’d grown up watching in Mad Max and Lethal Weapon movies, and Gibson in turn ran with the “cowboy” angle, modeling Chris on several people he knew in his own life.

Even with this background, audiences will likely be surprised by how stripped down Fatman is when they watch it for themselves. Because while there may be elves with bells on their shoes, for example, these helpers work in a low lit, industrial hell and on a stretch of Alaskan farmland far removed from a magical workshop.

Says Eshom, “We were like, ‘Okay, Santa’s in the North Pole?’ Well, there isn’t shit at the North Pole. So if he really wanted an infrastructure and to [actually] get supplies and power, and all this stuff, we’re like, ‘Okay he’s got to be somewhere where there’s a slight civilization. So Alaska.”

It’s part and parcel for an approach that pivots on grounding the Santa Claus mythology in as much reality as possible. This Santa still rides around the world on magical reindeer, but we don’t actually see that Christmas Eve adventure. Instead we bear witness to the aftermath, where Chris comes home exhausted and bleeding, with a hole in his coat from where some kid shot him with a BB-gun.

It’s obviously unlike any Santa you’ve ever seen before. And while the film has already been welcomed by a niche audience in limited theatrical release, it’s also received plenty of criticism for its violent portrayal of Father Christmas. But the Nelms are unbothered by that criticism.

“This isn’t for kids, you know?” Eshom says. “If you want Miracle on 34th Street mixed with Die Hard, this might be your flavor.” Additionally, each director is stunned at how much more timely a beleaguered Santa feels in 2020, since they’ve been trying to get this movie off the ground for 14 years.

“We finished shooting right at the beginning of the pandemic,” Ian says. “We finished shooting and then the next day they shut down all productions in Canada. We were really fortunate to finish on time and then we spent the next six months editing it in my basement. So we had a wonderful distraction, which was nice, but it was a weird time to do it because the tension [is] ratcheting across the world, especially in our country being hit so hard by the pandemic.”

Ironically, they made a film about a once benevolent figure looking at the rising despair and naughtiness of modern American society, and recoiling. That tension, which is as tight a string can get without breaking according to Ian, has only gotten further strained since the film’s edit locked.

Nevertheless, the filmmakers don’t view Santa Claus or the Spirit he represents as a cynical one, even in Fatman. Rather they describe Gibson’s Chris Kringle as something of a guiding light: a man who gives toys to urge children toward whatever skills or proclivities they might have to better realize their futures. So Chris’ wearied resolution to continue the job is as optimistic as it is archetypal.

“I think he’s disgusted in himself, really,” says Ian. “He has that line at the end of the film where he just says, ‘You know, it’s partly my fault that we’ve gotten to this point.’ He’s talking about the state of the world, and he feels like he hasn’t quite been doing his job the last few hundred years. He’s let everything kind of slip and slide, as people do… But he’s trying to figure out how to get it back, and that’s really what the bottom line is, right? Like a call to action, he’s got to get back to the old ways.”

Maybe we all can this Christmas.

Fatman is available on VOD and in limited theatrical release now.

cnx.cmd.push(function() { cnx({ playerId: "106e33c0-3911-473c-b599-b1426db57530", }).render("0270c398a82f44f49c23c16122516796"); });

The post Fatman: Why Mel Gibson Found Christmas Spirit at the End of a Gun appeared first on Den of Geek.

from Den of Geek https://ift.tt/33eyoPb

0 notes

Text

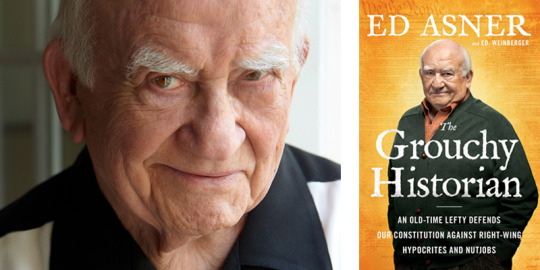

Powell's Q&A: Ed Asner, Author of 'The Grouchy Historian'

Describe your latest book.

My book, The Grouchy Historian, is my attempt to rescue the U.S. Constitution from right-wing hypocrites and nutjobs. I got tired of the Right acting not only like it owns the Constitution, but wrote the damn thing as well. So — pissed off at ring-wing lies (by the way, my original title was The Pissed-Off Historian, but Simon & Schuster thought better of it), misrepresentations, and outright horseshit, I decided to strike back. After all, if the Right could be wrong about climate change, health care, and the corporate tax rate, it was probably wrong about the Constitution.

So I did my homework. I read the Constitution and the Amendments; perused The Federalist Papers and the notes Madison took during the Constitutional Convention; surveyed the lives of the Founders and Framers; looked over the Supreme Court opinions of Antonin Scalia and Clarence Thomas; and even dipped into Ted Cruz’s autobiography, A Time for Truth, a faith-based romance novel in which the hero falls in love with himself at an early age.

Here is a preview of what I came up with: The Framers wrote the Constitution in order to form a strong central government, giving sweeping powers to Congress (not the states), balanced by an equally strong Executive Branch. Nothing in the Constitution suggests, let alone enforces, the concepts of limited government, limited taxes, or limited regulations. The Framers were not divinely inspired. They were lawyers. Do you really know any divinely inspired lawyers? The only lawyer ever to be divinely inspired was Saul of Tarsus. The Framers were as diverse a group as the Mormon Tabernacle Choir. The Framers did not hate taxation. They needed taxes, desperately. They had a war to pay off. Strict constructionists are people who select portions of the Constitution to justify already held beliefs. Under the Constitution, women had the same rights as Native Americans. The Constitution is as good as the people who swear to protect it. For the rest of it, you’re going to have to buy the book. I know what you’re thinking: Why me of all people? Why am I writing a book about the Constitution? Well, why not me? After all, I have played some of the smartest people ever seen on television.

What was your favorite book as a child?

I know I should say Mark Twain’s Adventures of Tom Sawyer or E. B. White’s Charlotte’s Web. But the truth is my favorite book as a child was a book of collected riddles by an unremembered author. Some of the riddles that I can recall are:

What is the smallest room in the world? A mushroom.

Why do firemen wear red suspenders? To keep their pants up.

What is white and black and red all over? A newspaper (red = read).

Why did the idiot tiptoe past the medicine chest? He didn’t want to wake up the sleeping pills.

Not politically correct, of course, but very funny to a six-year-old boy.

When did you know you were a writer?

When Simon & Schuster sent me an advanced copy of The Grouchy Historian — with my picture on the cover.

What does your workspace look like?

I work at a desk in my office, which is on the first floor of my house. The office has doors that don’t lock, so at any time anyone can barge in and interrupt my writing for no good reason. Thank God.

What do you care about more than most people around you?

I believe the people around me care for the same things I do: racial and religious tolerance, civilized discourse, a government of and for the people, gender and economic equality, and a new president as soon as possible. If they didn’t, they wouldn’t be around me.

Share an interesting experience you've had with one of your readers.

One of my first readers was a Constitutional scholar, law professor, and distinguished historian. He agreed to give me notes on an early draft of The Grouchy Historian. A year later and I still haven’t heard from him. I only hope it was something I said.

Tell us something you're embarrassed to admit.

I’m in love with Marie Osmond.

Introduce one other author you think people should read, and suggest a good book with which to start.

Read Philip Roth. And if you have, read him again. Of his more than 20 novels, I recommend The Plot Against America, which is Roth’s vision of an America with Charles Lindbergh — air hero and fascist — as president. Set in the 1940s, it’s as relevant as it is scary. I also recommend American Pastoral, which is Philip Roth at his best — funny yet painful, powerful and brilliant. Why Roth has not won the Nobel Prize for Literature I have no idea.

Besides your personal library, do you have any beloved collections?

No “beloved” collections. Just books.

Have you ever made a literary pilgrimage?

Yes. Many years ago, I went to Prague and visited Kafka’s grave. He’s buried there in the Jewish cemetery beside his mother and father. Kafka died in 1924 at the age of 40. A short life. Still, when you think that in less than two decades his sister would perish in a Nazi concentration camp — well, maybe he was “lucky” to have died so young. I placed three stones on his grave and recited the Jewish prayer for the dead — at least the parts I could remember. Afterwards, I found a bookstore that sold The Metamorphosis in English. It’s one of my favorite stories — about a young man who turns into a cockroach and becomes a burden to his family. And what young man cannot identify with that?

What scares you the most as a writer?

There are two things that scare me the most as a writer: a blank page and the royalty statement from my publisher.

If someone were to write your biography, what would be the title and subtitle?

Ed Asner: Not Just a Character Actor, but a Character

Offer a favorite passage from another writer.

One of my favorite passages is from Mark Twain’s essay, “Fables of Man,” in which he questions how a loving, benevolent God could have made the common housefly:

When we reflect that the fly was as not invented for pastime, but in the way of business; that he was not flung off in a heedless moment and with no object in view but to pass the time, but was the fruit of long and painstaking labor and calculation, and with a definite and far-reaching purpose in view; that his character and conduct were planned out with cold deliberation, that his career was foreseen and foreordered, and that there was no want which he could supply, we are hopelessly puzzled, we cannot understand the moral lapse that was able to render possible the conceiving and the consummation of this squalid and malevolent creature.

Share a sentence of your own that you're particularly proud of.

From The Grouchy Historian: “Justice Antonin Scalia had to be the one percent’s favorite judge since Pontius Pilate.”

Describe a recurring nightmare.

My recurring nightmare is as follows: I am playing King Lear. As I make my entrance into a packed New York theater, I suddenly forget my lines. I can’t even remember “Attend the Lords of France and Burgundy.” The rest of the play continues while, from me, not a word is spoken. Then, if that isn’t bad enough, before I know it I'm walking around onstage in my boxers and T-shirt. Fortunately, I wake up right before I have to go to the bathroom.

Do you have any grammatical pet peeves?

I have a problem with most grammar police. Especially those who tell me I can’t begin a sentence with “and.” Maybe they forget: “And God caused a deep sleep to fall upon Adam.” Or those who are afraid of repeating the same word in the same sentence or paragraph. You know, like in “To be or not to be.” And those who warn against ending a sentence with a preposition — which is a bad rule that no one should stick to.

Do you have any phobias?

I have three major phobias: A fear of clowns, spiders, and unhinged Presidents of the United States.

Name a guilty pleasure you partake in regularly.

Sorry, but all my pleasures are guilt-free.

What's the best advice you've ever received?

The best advice I ever got came from my father, who said: “Stay positive — it’ll probably get worse”; “Carry your own bags”; “Never take money from a stranger”; and “Never order breaded veal cutlet in a restaurant.”

Now that you’re 86 years old, what’s the best thing about old age?

Not giving a shit.

My Top Five Books of All Time List:

The Bible, especially all those parts with the sex and violence.

Inferno by Dante. Hell hath no fury like a writer scorned.

Collected plays and poetry by William Shakespeare. Whoever really wrote them, he or she is a special genius “for all time.”

Huckleberry Finn by Mark Twain, the book where, as Hemingway said, American literature begins.

Mary and Lou and Rhoda and Ted by Jennifer Armstrong. There's something about this book that I can never get enough of.

89 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fertility research master post

NEW IDEAS BASED ON FERTILITY, WOMEN’S RIGHTS, POSITIONS OF POWER OVER WOMEN’S BODIES

What foods are meant to help with fertility?

‘…there are so many bodily functions that occur behind the scenes that are responsible for making this natural process happen, and the foods we eat can affect the level of our hormones, quality of our blood and its circulation, and how well our brain is able to send messages to the rest of our body - all things that play a role our fertility.’ - https://www.mother.ly/lifestyle/7-best-foods-boost-fertility'

Wild salmon, quinoa, low fat greek yoghurt, spinach, lentils, blueberries, oysters

This article is by a women written for other women to help become healthy and boost your immune system to have a child. This is not so much a control thing rather than something to help with women who want to conceive.

https://www.buzzfeed.com/carolinekee/crazy-historical-birth-control-methods

I have found out that Egyptian people often used honey and acacia leaves as a spermicide or to stick ‘tampons’ in their vaginas. Honey is important.

https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/article-abstract/286666

The ancient Roman gynecologist Soranus thought that women should take responsibility for the withdrawal method by doing the following: holding their breath when they believed their parter was ejaculating, then getting up immediately after intercourse to squat and sneeze repeatedly, then washing out their vagina. Because, sure.

tarting around 700 BCE, the ancient Romans would use bladders from goats, sheep, and other animals to wrap around the penis during sexual intercourse. Apparently, the Romans were invested in ideas of public health and created this method to "protect women" and prevent the transmission of venereal diseases like syphilis.

Although these goat-bladder condoms were originally intended for protection against venereal diseases, they ended up being a pretty effective contraceptive method and people used them well into the Medieval Period.

7. Smearing cedar oil and frankincense in the vagina - Although it sounds more like a potpourri or an air freshener, this natural ointment mixture was a popular contraception method around the fourth century in ancient Greece. Women would smear a mixture of cedar oil, frankincense, and sometimes lead into their vaginas and around their cervix to prevent pregnancy. It was believed that the oil mixture acted as a spermicide, and it was actually recommended by Aristotle in his early medical texts.

Around the 16th century in Elizabethean England, women were advised to wash their genitals and douche using vinegar — like the same kind you clean with.

"Women sometimes used other harsh astringents in the vagina before sex, because they believed it would kill sperm," Minkin says. Vinegar-soaked sponges were apparently a popular option for Elizabethan prostitutes

Imagine cutting a lemon in half and juicing it so the rind forms a little cap. Starting around the mid-17th century, women would insert this into their vagina before sex — the idea was that the rind would prevent sperm from entering the uterus through the cervix and the acidic juice would kill sperm, too.

"The mechanism of the lemon cervical cap, blocking the cervix, is the same idea behind the modern rubber cervical cap invented in 1927, which is still used with spermicide as a contraception today," Minkin says.

It's worth mentioning that many people in the US had to use alternative or outdated methods even up until the 1950s, because the use of modern contraception (like condoms, diaphragms, and pills) was a punishable crime. Actually, birth control was illegal in the US for nearly a century under the Comstock Act passed in 1873.

"Birth control wasn't officially legal until 1965 after the Supreme Court ruling in Griswold v. Connecticut, which made it unconstitutional for the government to prohibit married couples from using birth control," Minkin says. So we've technically only had access to safe, effective birth control for about fifty years.

http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/pill-anthony-comstocks-chastity-laws/

As late as 1960, the American legal system was not hospitable to the idea of birth control. Thirty states had statutes on the books prohibiting or restricting the sale and advertisement of contraception. These laws stretched back almost a century, reflecting an underlying American belief that contraception was lewd, immoral and promoted promiscuity.

Comstock's Crusade

The driving force behind the original anti-birth control statutes was a New Yorker named Anthony Comstock. Born in rural Connecticut in 1844, Comstock served in the infantry during the Civil War, then moved to New York City and found work as a salesman. A devout Christian, he was appalled by what he saw in the city's streets. It seemed to him that the town was teeming with prostitutes and pornography. In the late 1860s, Comstock began supplying the police with information for raids on sex trade merchants and came to prominence with his anti-obscenity crusade. Also offended by explicit advertisements for birth control devices, he soon identified the contraceptive industry as one of his targets. Comstock was certain that the availability of contraceptives alone promoted lust and lewdness.

Making Birth Control a Federal Crime

In 1872 Comstock set off for Washington with an anti-obscenity bill, including a ban on contraceptives, that he had drafted himself. On March 3, 1873, Congress passed the new law, later known as the Comstock Act. The statute defined contraceptives as obscene and illicit, making it a federal offense to disseminate birth control through the mail or across state lines.

Public Support for Comstock Laws

This statute was the first of its kind in the Western world, but at the time, the American public did not pay much attention to the new law. Anthony Comstock was jubilant over his legislative victory. Soon after the federal law was on the books, twenty-four states enacted their own versions of Comstock laws to restrict the contraceptive trade on a state level.

The Most Restrictive States

New England residents lived under the most restrictive laws in the country. In Massachusetts, anyone disseminating contraceptives -- or information about contraceptives -- faced stiff fines and imprisonment. But by far the most restrictive state of all was Connecticut, where the act of using birth control was even prohibited by law. Married couples could be arrested for using birth control in the privacy of their own bedrooms, and subjected to a one-year prison sentence. In actuality, law enforcement agents often looked the other way when it came to anti-birth control laws, but the statutes remained on the books.

Sanger's Crusade

These laws remained unchallenged until birth-control advocate Margaret Sanger made it her mission to challenge the Comstock Act. The first successful change in the laws came from Sanger's 1916 arrest for opening the first birth control clinic in America. The case that grew out of her arrest resulted in the 1918 Crane decision, which allowed women to use birth control for therapeutic purposes.

Changing Laws for Changing Times

The next amendment of the Comstock Laws came with the 1936 U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals decision, United States v. One Package. The decision made it possible for doctors to distribute contraceptives across state lines. This time Margaret Sanger had been instrumental in maneuvering behind the scenes to bring the matter before the court. While this decision did not eliminate the problem of the restrictive "chastity laws" on the state level, it was a crucial ruling. Physicians could now legally mail birth control devices and information throughout the country, paving the way for the legitimization of birth control by the medical industry and the general public.

http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/pill-boston-pill-trials/

https://www.bustle.com/articles/72266-the-6-craziest-birth-control-methods-in-history-from-weasel-testicles-to-crocodile-poop

Many old-fashioned contraceptive methods display an impressive, if rudimentary, understanding of how conception and pregnancy occurred. The weasel testicle method is not one of them. Many medieval Europeans believed that weasel testicles could prevent conception — if they were hung around a woman's neck like an amulet during intercourse (and, presumably, were removed from the body of the weasel beforehand).

But if weasel balls hanging from around your neck sounds like a turn off, don't worry! You could also wear weasel testicles around your thigh for birth control purposes. Charms made from donkey poop, a mule's uterus, or a specific bone from the body of a black cat were also believed to offer the same level of magical pregnancy protection.

And if that last one didn't work? Many medieval folks believed it meant the wearer had selected a cat whose fur was not dark enough. I am not happy that anyone got unintentionally pregnant using this method, but it would kind of have been funny to watch the arguments that resulted ("I told you that cat wasn't dark enough! What are we going to do now?!").

https://www.plannedparenthood.org/files/2613/9611/6275/History_of_BC_Methods.pdf - read this

Not all crazy birth control methods date back to ancient pre-technology societies.

In the 1950s, the idea spread that the carbonic acid in Coca-Cola killed sperm, the sugar exploded sperm cells and the carbonation of the drink forced the liquid into the vagina. So it became an after-sex douche: Women would shake up a bottle, insert it and let the soda fly.

Lots of women throughout history thought the answer to pregnancy was flushing it all away. Native American women tried steaming sperm out using a special kettle; others have tried seawater, vinegar, lemon juice and other acidic liquids.

As we all know, spermicide isn’t effective at stopping pregnancy once the seed is already inside the vagina, so steaming it never stood a chance.

As cited in an ancient medical manuscript dating back to 1550 B.C., women were told to grind dates, acacia tree bark and honey together into a paste and apply the mixture to seed wool, which would be inserted vaginally.

The acacia in the cotton fermented into lactic acid, which has spermicidal properties, and the wool served as a physical barrier blocking insemination. These proto-diaphragms were buried with women so they wouldn’t get pregnant in the afterlife either.

Tallents, Carolyn. "7 Best Foods To Boost Fertility." Motherly. February 09, 2019. Accessed June 06, 2019. https://www.mother.ly/lifestyle/7-best-foods-boost-fertility.

"The Pill and the Sexual Revolution." PBS. Accessed June 06, 2019. http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/pill-and-sexual-revolution/.

"The Boston Pill Trials." PBS. Accessed June 06, 2019. http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/pill-boston-pill-trials/.

Kee, Caroline. "13 Historical Birth Control Methods That Should Stay In The Past." BuzzFeed. March 21, 2017. Accessed June 06, 2019. https://www.buzzfeed.com/carolinekee/crazy-historical-birth-control-methods.

Targonskaya, Anna. "Ancient Birth Control Methods: How Did Women in Ancient Times Prevent Pregnancy?" Flo.health - #1 Mobile Product for Women's Health. January 02, 2019. Accessed June 06, 2019. https://flo.health/menstrual-cycle/sex/birth-control/ancient-birth-control-methods.

0 notes

Text

Women In History

I grew up believing that women had contributed nothing to the world until the 1960′s. So once I became a feminist I started collecting information on women in history, and here’s my collection so far, in no particular order.

Lepa Svetozara Radić (1925–1943) was a partisan executed at the age of 17 for shooting at German soldiers during WW2. As her captors tied the noose around her neck, they offered her a way out of the gallows by revealing her comrades and leaders identities. She responded that she was not a traitor to her people and they would reveal themselves when they avenged her death. She was the youngest winner of the Order of the People’s Hero of Yugoslavia, awarded in 1951

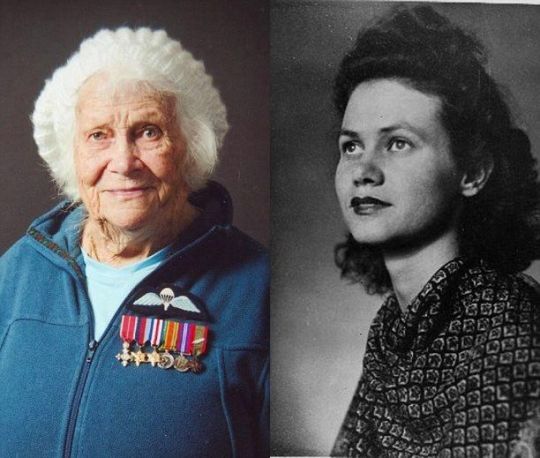

23 year old Phyllis Latour Doyle was British spy who parachuted into occupied Normandy in 1944 on a reconnaissance mission in preparation for D-day. She relayed 135 secret messages before France was finally liberated.

Catherine Leroy, War Photographer starting with the Vietnam war. She was taken a prisoner of war. When released she continued to be a war photographer until her death in 2006.

Lieutenant Pavlichenko was a Ukrainian sniper in WWII, with a total of 309 kills, including 36 enemy snipers. After being wounded, she toured the US to promote friendship between the two countries, and was called ‘fat’ by one of her interviewers, which she found rather amusing.

Johanna Hannie “Jannetje” Schaft was born in Haarlem. She studied in Amsterdam had many Jewish friends. During WWII she aided many people who were hiding from the Germans and began working in resistance movements. She helped to assassinate two nazis. She was later captured and executed. Her last words were “I shoot better than you.”.

Nancy wake was a resistance spy in WWII, and was so hated by the Germans that at one point she was their most wanted person with a price of 5 million francs on her head. During one of her missions, while parachuting into occupied France, her parachute became tangled in a tree. A french agent commented that he wished that all trees would bear such beautiful fruit, to which she replied “Don’t give me any of that French shit!”, and later that evening she killed a German sentry with her bare hands.

After her husband was killed in WWII, Violette Szabo began working for the resistance. In her work, she helped to sabotage a railroad and passed along secret information. She was captured and executed at a concentration camp at age 23.

Grace Hopper was a computer scientist who invented the first ever compiler. Her invention makes every single computer program you use possible.

Mona Louise Parsons was a member of an informal resistance group in the Netherlands during WWII. After her resistance network was infiltrated, she was captured and was the first Canadian woman to be imprisoned by the Nazis. She was originally sentenced to death by firing squad, but the sentence was lowered to hard lard labor in a prison camp. She escaped.

Simone Segouin was a Parisian rebel who killed an unknown number of Germans and captured 25 with the aid of her submachine gun. She was present at the liberation of Paris and was later awarded the ‘croix de guerre’.

Mary Edwards Walker is the only woman to have ever won an American Medal of Honor. She earned it for her work as a surgeon during the Civil War. It was revoked in 1917, but she wore it until hear death two years later. It was restored posthumously.

Italian neuroscientist won a Nobel Prize for her discovery of nerve growth factor. She died aged 103.

EDIT

jinxedinks added: Her name was Rita Levi-Montalcini. She was jewish, and so from 1938 until the end of the fascist regime in Italy she was forbidden from working at university. She set up a makeshift lab in her bedroom and continued with her research throughout the war.

A snapshot of the women of color in the woman’s army corps on Staten Island

This is an ongoing project of mine, and I’ll update this as much as I can (It’s not all WWII stuff, I’ve got separate folders for separate achievements).

File this under: The History I Wish I’d Been Taught As A Little Girl

1 note

·

View note

Text

Final Blog: Representation’s Role in Equality

The most fundamental part of Human society is the Family unit. Childhood has always been seen as the most influential part of life on the formation of an identity. Why then do we not teach our children about cultures that are different from the Western idea of life? Maybe because we’ve been taught through our childhoods that these peoples are so different that our children may not understand. Maybe it’s because we try and hide the atrocities committed by our ancestors that allow most of Europe, and our country to thrive in the way we have.

I don’t know what makes the Western, predominantly White groups of people believe that they are superior to the world, but a common message sent out by them is that it was for the sake of “progress”. This is very circular logic; if a culture tells itself that it is somehow better than any culture less developed it is simply ignoring its own development cycle and then validating its opinions and prejudices towards their culture, their knowledge, and physical differences under the guise of objective comparison based on innovation. This ignores the context of these cultures, their geographic location, their available resources, surrounding cultures, and so many more factors that may tie into development.

I will preface my discussion about The Thing Around Your Neck with some history, and a statement that I do not go that deep into the stories of The Thing Around Your Neck in order to help make a point.

The use of Africans as slaves was started by the Portuguese in 1526, and continued for hundreds of years after, with the British, the French, the Spanish, and the Dutch Empire joining in. The early practice of bringing them over as indentured servants and “apprentices for life” (as if they needed one) devolved into chattel slavery (slaves as property) by the mid 1600s. The “demand” for slaves was created by the booming plantations, their continued abuse, and the inhuman living conditions afforded to them. This increase in demand and thus, supply of slaves led to a very harsh racial caste throughout the world, as the Arab World had their own blossoming trade of slaves from Africa. We even tell stories about how most of the slaves in the Atlantic slave trade were sold to us by other Africans who had taken captives in wars despite the wars being supported and fought in by the countries that were buying the slaves. The European countries won both world influence and human lives that they were happy to destroy. The slaves were slaves forever, and their children were slaves from the minute they were born, their only culture and knowledge being that of a plantation or other workplace.

The identity of these slaves was taken away and their cultures destroyed, not to be mentioned throughout history except for the few great empires like Ghana, Mali, and Songhai. It is interesting to look at the power vacuum created by the strife before and after the collapse of Songhai in 1591 and the way Europeans used that to solidify their hold on the African continent as a source of slaves and goods. We celebrate these empires as great, yet swooped in to gobble up the remaining previously conquered countries that were already trying to rebuild their identity. Historically, the reasons these empires were seen as great are quite shallow but telling. They were valued not only for their gold, salt, and other resources, but because they were told stories about these great civilizations, the empires were heard of as far as the Mediterranean. The Mediterranean then writing these stories down and allowing these stories of grandness to be divulged throughout history.

These stories forced us to acknowledge the fact that there were African civilizations that had grand aspirations, that had large regional trade hubs, intelligence and culture. Since the arrival of Europeans to the continent we see a stark change in history about Africa. The nations that remained after the fall of the empires had no story told in the West other than the ones they invented for those countries, stories of international slavery and a focus on color of skin as a factor in that slavery. The modern stories told to us about Africa are drastically different, yet still have the same stigma. We talk about these nations we’ve as if they are worse now because of environmental factors, loss of resources due to their own trade, civil wars and constant fighting with other groups nearby; yet the stigma of their skin and genetics, as well as the toxic control by Europe poisons the pot with racial undertones and a constant feeling of condescending rhetoric and avoiding our own guilt.

These stories of civil wars and other fighting, and warlords only serve to make us feel better about ourselves. We say that they are struggling because of their own faults much like we deflect the questions about the police brutality towards and murder of black people by bringing up irrelevant statistics about black on black crime. Or the way we still talk about the “ways that black children are worse behaved”, using statistics that may be true, but are completely influenced by racist practices in discipline, from preschool all the way to the Supreme Court.

The Thing Around Your Neck is a collection of twelve stories that takes place in Nigeria and the United States, the use of both settings has a lasting impact on the reader, with the United States being used to show that the oppression and identity loss caused by colonization never ends. There is very long lasting damage from the modern racism that started from the Atlantic slave trade. Adichie’s stories don’t seem to want to criticize and belittle Americans or our culture, instead they serve as a sullen reminder that these people we oppressed are just the same as us at heart. They have dreams, family life, curiosity, technology, love, hatred, fear, sadness, politics, universities. It forces us to acknowledge these people as people, and as great civilizations (let’s face it, if you’ve lasted this long you’re a great civilization) just like the stories of the kingdoms of Ghana, Mali, and Songhai, kingdoms I was taught were “ancient” despite them being a progression of civilizations that lasted from around 300 CE until 1591 CE. Maybe ancient at first, but the distinction of them as ancient is a fuzzy lie that seems to be used to amplify the idea that these countries were less developed than the European countries at the time.

What we need is more stories. Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s The Thing Around Your Neck is the kind of stories we need. Not ones that focus on what the West thinks of African countries, but authentic and genuine stories that focus on what African countries think of themselves and the West, and that let them showcase their unique cultures, that let them be the heroes, that let them be whomever they want. Their culture has been suppressed for so many hundreds of years, why shouldn’t we let them teach us about their culture and how they feel about our oppression of it, we’ve certainly caused enough pain for them to get that liberty. Instead, these stories of civil wars and other fighting, and warlords only serve to make us feel better about ourselves. We say that they are struggling because of their own faults much like we deflect the questions about the police brutality towards and murder of black people by bringing up irrelevant statistics about black on black crime. Or the way we still talk about the “ways that black children are worse behaved”, using statistics that may be true, but are completely influenced by racist practices in discipline, from preschool all the way to the Supreme Court.

The truth is, it doesn’t matter what these stories are about, the stories in The Thing Around Your Neck are not special stories because of special events happening or some incredible hero, they are special because they are exactly not these things. They tell stories of common people, of everyday experiences, even things that some of us can relate to. Stories about a son/brother in jail, of an immigrant nanny who falls in love, about two women stuck and scared during a riot, and many more. It doesn’t matter what these individual stories from the book are about (it does, but bear with me), it matters that this collection of short stories feel like it has identity/ies. It feels like a conversation with people from the country. You feel personally connected to them. In fact, the short story form is crucial to the book’s representation of Nigeria as a very different but very relatable country. The representation of these people, not as something ultra unique or anything special, is the kind of representation that leads to inclusion and understanding. They make us relate to people who we have possibly not even thought about before. That is an important realization for people to come to, and I believe that it is at the base of stopping racial prejudice that these stories of oppressed or even simply different people are told to our children along with true and non-covered-up history. It would much easier to create equality, understanding, and healthy communication if everyone had these concepts given to them in their formative years. If not exposed to the cultures enough in that time one might end up being the most powerful man in the world and still believing the childhood prejudices given to him by his parents, notably his father (along with that sweet “small loan of $1,000,000).

References:

Ghana, Mali, and Songhai - a lesson from a GMU professor I know - http://chnm.gmu.edu/fairfaxtah/lessons/documents/africaPOSinfo.pdf

Atlantic slave trade -

Deborah Gray White, Mia Bay, and Waldo E. Martin, Jr., Freedom on My Mind: A History of African Americans (New York: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2013), 11.

Weber, Greta (June 5, 2015). "Shipwreck Shines Light on Historic Shift in Slave Trade". National Geographic Society. Retrieved February 22, 2017.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

We didn’t start the FIRE: The true history of financial independence

I used to be a collector. I collected trading cards. I collected comic books. I collected pins and stickers and mementos of all sorts. I had boxes of things I'd collected but which essentially served no purpose.

I can't say I've shaken the urge to collect entirely, but I have a much better handle on it than I used to. A few years ago, I sold my comic collection and stopped obsessing over them. Today, I collect three things: patches from the countries I visit, pins from national parks, and — especially — old books about money.

Collecting old money books is fun. For one, it ties to my work. Plus, there's not a huge demand for money manuals, so there's not a lot of competition to buy them. (Exception: As much as I'd love a copy of Ben Franklin's The Way to Wealth, so would a lot of other people. That one is out of my reach.)

One big bonus from collecting old money books is actually reading these books. They're fascinating. And it's interesting to trace the development of certain ideas in the world of personal finance.

For instance, there's this persistent myth of “lost economic virtue”. That is, a lot of people today want to argue that people were better at managing their money in the past. They weren't. Debt (and poor money skills) has been a persistent problem since well before the United States was founded. It's not like we, as a society, once had smart money skills and lost them. The way people manage money today is the way they've always managed money.

Or there's the notion of financial independence (and the closely-related topic of early retirement). The standard narrative goes something like this:

In 1992, Joe Dominguez and Vicki Robin published Your Money or Your Life, and that marks the “discovery” of FIRE.

In the late 2000s, Jacob from Early Retirement Extreme picked up the FIRE banner, then handed it off to Mr. Money Mustache a few years later.

Today that banner is being carried by newcomers like Choose FI and the /r/financialindependence subreddit.

When you read old money books, however, you soon realize that FIRE isn't new. These ideas have been kicking around for a while. Sure, the past decade has seen the systemization and codification of the concepts, but people have been preaching the importance of financial independence for about 150 years. Maybe longer.

youtube

Today, using my collection of old money books, let's take a look at where the notion of financial independence originated.

This article is a work in progress. It's something I've been thinking about for years, but I haven't had the resources to actually write it until recently. And as I acquire more old books about money, I'm sure my insights will change. This particular version is based on a talk I gave last month at Camp FI in Colorado. In fact, some of the images I'm using here are taken from the slides for that talk.

In the Beginning

Who started the FIRE movement? Who “invented” financial independence? Who first came up with the concept? Despite my burgeoning library of money manuals, I don't have a definitive answer. Not yet anyhow.

That said, the earliest reference I've found is Aesop's fable of the Ants and the Grasshopper from about 560 BCE. (The grasshopper was a cicada in the original Latin, by the way.) Here's an English translation of the original:

The ants were spending a fine winter’s day drying grain collected in the summertime. A Grasshopper, perishing with famine, passed by and earnestly begged for a little food. The Ants inquired of him, “Why did you not treasure up food during the summer?” He replied, “I had not leisure enough. I passed the days in singing.” They then said in derision: “If you were foolish enough to sing all the summer, you must dance supperless to bed in the winter.”

This fable clearly contains the germ of the financial independence idea, even if it doesn't explicitly talk about F.I. and/or early retirement.

Now, I'm certain there are references to this concept in other ancient literature. I haven't gone looking for them yet, however, so I can't tell you where to find them. (If you know, please tell us in the comments.)

But if we jump forward 2250 years, we can see F.I. concepts quite clearly in the writing of Benjamin Franklin. “If you would be wealthy, think of saving, as well as of getting,” Franklin wrote in 1758's The Way to Wealth. He noted that because they were so obsessed with nice things, many wealthy people are reduced to poverty and forced to borrow from people they once looked down upon.

In 1854, Henry David Thoreau published Walden. While I have some issues with this book (and with Thoreau), Walden contains a clear foundation for the modern FIRE movement. In fact, when I emailed Vicki Robin to ask what inspired her and Joe Dominguez to teach about financial independence, she specifically cited Thoreau. And it's easy to see why. “The mass of men lead lives of quiet desperation,” he famously wrote. But he also wrote this:

The cost of a thing is the amount of what I will call life which is required to be exchanged for it, immediately or in the long run.

That quote from Walden sounds as if it could be lifted directly from Your Money or Your Life‘s discussion of life energy, doesn't it?

In 1864 — during the American civil war — Edmund Morris published Ten Acres Enough, which documented his family's moved from the city to the country in order to grow ten acres of fruits and berries. His goal was for his family to be self-sufficient, to obtain what we'd call financial independence.

Morris' approach was typical of the day. He wrote:

No prudent man, accepting such a trust, and guaranteeing its integrity, would invest the fund in stocks. Our country is filled with pecuniary wrecks from causes like this…

Like many of his contemporaries, Morris thought stocks were a poor investment. He advocated investing in real estate. (And note his use of the word “pecuniary” instead of “financial”. We'll come back to that in a moment.)

Fun trivia! In Ten Acres Enough, Morris doesn't call the Civil War a “civil war”. He calls it “the slaveholders' rebellion”. He also makes liberal use of the word “treason”. There's no bullshit about the source of the war being “states' rights” as we hear nowadays.

Coining a Term

In 1872, H.L. Reade published a book called Money and How to Make It. This is an amazing book — one of my favorites out of all the volumes I've picked up over the past few years. It tackles all sorts of diverse topics, and is quite progressive for its day.

Much of the book is, as the title suggests, about how to earn more money. To that end, Reade offers chapters on how to make money with geese and with ducks and with cattle. He talks about making cheese. He talks about becoming a doctor or a lawyer. But he also includes a chapter on “Woman's Part in Making Money” and one on “The Brotherhood of Man”. Cool stuff for 1872!

But the reason this book is important is that it's the first instance that I've been able to find where an author actually writes about financial independence. Here's a quote from the book's introduction:

We have purposely united with plain practical talk, enough of history and story to relieve the volume from any text book tendency, and believing, as we sincerely do, that no man or woman can read it without receiving a value far greater than its cost, we commend it to the calm consideration of every person who, like the writer, beginning comparatively poor, is anxious to reach what all men should desire and labor for, PECUNIARY INDEPENDENCE.

There you have it. The first reference (that I've been able to find so far) to the idea of financial independence.

But wait. What's up with Reade calling it “pecuniary independence”. That's strange, isn't it? Well, not really. Turns out that the word “financial” wasn't yet in common use in 1872. The word had been around a few hundred years, but it wasn't until the late 1700s that “financial” began to take on the definition it has today: “relating to money”. Before that, people used the word “pecuniary” instead.

Here are a couple of graphs that show how the usage of “financial” and “pecuniary” have changed over time.

It wasn't until the late 1800s that “financial” supplanted “pecuniary” as the term of choice. In 1872, Reade didn't write about “financial independence” because “pecuniary indepence” was the more common term!

Nerdy stuff, eh?

Another important early F.I. book was published at about this same time. In 1875, Scottish author and social reformer Samuel Smiles published Thrift, which was meant to conclude a trilogy of personal development books. (Smiles published Self-Help in 1859 and Character in 1871.)

In the preface to Thrift, Smiles writes:

Every man is bound to do what he can to elevate his social state, and to secure his independence. For this purpose he must spare from his means in order to be independent in his condition. Industry enables men to earn their living; it should also enable them to learn to live. Independence can only be established by the exercise of forethought, prudence, frugality, and self-denial. To be just as well as generous, men must deny themselves. The essence of generosity is self-sacrifice.

And Smiles begins the book by re-stating the fable of the Ants and the Grasshopper. For my money — and I haven't read the entire book yet because I just got in the mail yesterday — this could very well be the first book about financial independence…even if it never uses that term precisely.

youtube

So, what's the first actual reference to the term “financial independence”? I don't have a definitive answer yet, but I do know its earliest appearance in my collection of old money books.

In 1919, Victor de Villiers published Financial Independence at Fifty, a collection of loosely-related articles that originally appeared in “The Magazine of Wall Street”. While the book itself doesn't dwell on financial independence, the author includes this definition at the start:

What is financial independence? Freedom from dependence on others for guidance, government, or financial support. The spirit of self-reliance, or of freedom from subordination to others.

He also includes a chart showing “the six ages of investment” which is strikingly similar to my own list of the six stages of financial independence!

Financial Independence through the Years

From these humble origins, the concept of “financial independence” grew more complex and more robust. The path to financial independence became codified.

One of the first books to set out a system to help others become F.I. was the immensely popular The Richest Man in Babylon, which is quite possibly the best-selling money manual of all time.

The Richest Man in Babylon began as a series of pamphlets distributed through banks and insurance companies during the early 1920s. In 1926, author George Clason collected this material into book form for the first time. Over the years, Richest Man underwent several revisions until it reached the form we know today.

youtube

As you're probably aware, Clason suggested the following seven commandments for building wealth.

Start thy purse to fattening. (Save 10% of all you earn.)

Control thy expenditures. (Avoid lifestyle inflation; curb desires.)

Make thy gold multiply. (Use compounding to grow wealth.)

Guard thy treasures from loss. (Avoid get-rich-quick schemes.)

Make of thy dwelling a profitable investment. (Buy your home.)

Insure a future income. (Plan for retirement.)

Increase thy ability to earn. (Educate yourself.)

But there were plenty of lesser-known books published during the twentieth century that offered excellent financial advice and espoused the principles of financial independence.

In 1936, for instance, as part of a series of books called “The Franklin System”, Lansing Smith wrote Gaining Financial Security. This book (which is better than 90% of the money books being printed today!) might be the earliest book to promote financial independence as a concept by name and with a system. Here's an excerpt (emphasis mine):

If you want financial independence, you must realize its great and lasting value as a desirable attainment. You must keep everlastingly at the task of making it come true. Finally, you must let nothing shake or weaken your determination to achieve your objective.

There is one factor you should understand thoroughly at the outset: The amount of one's annual income has far less to do with ultimate financial independence than most people think. There are probably thousands of people with incomes many times the size of yours who are nevertheless deeply in debt and wholly unable to meet their obligations. On the other hand, many thousands have far less income than you have and yet they are managing to achieve financial security or are now maintaining and, indeed, increasing it.

Similar books followed. In 1946, in the wake of the second world war, John Durand published How to Build Financial Independence for a New Age. And during the 1950s, several books appeared with the term “financial independence” in their title. (Universally, however, these later books didn't actually discuss financial independence. Instead, they were manuals for investing in the stock market.)

The 1960s and 1970s saw other books about financial independence appear, many of which promoted a philosophy that seems relatively workable by today's standards. Then, in 1988, Paul Terhorst published what I consider the first modern FIRE book: Cashing In on the American Dream [my review].

Terhorst was 33 years old and a partner at a major accounting firm. But he began to wonder if he really wanted to be part of the rat race. Didn't he have enough money already? It took him two years of playing with numbers, but eventually he realized that he could quit working if he wanted. At age 35, he retired. And he's been retired ever since.

Early Retirement

You'll notice that so far I've only discussed the origin of the concept of “financial independence”. What about early retirement? The modern FIRE movement combines these two notions under one roof. Why don't older books do so?

The answer to this is complicated because the history of retirement is complicated.

You see, retirement as we know it has only existed for about 150 years. In reality, the definition of “retirement” has been in constant flux for most of that time. In the latter part of the 19th century (and the early part of the 20th century), retirement wasn't considered desirable. It was called “mandatory retirement”, and it was something that people railed against.

youtube

One hundred years ago, retirement was a massive social issue, much the same way that immigration or gun rights are today. Many people opposed retirement. It wasn't until the Social Security Act of 1935 that attitudes began to change. In time — by the 1950s, certainly — our modern view of retirement as a period of rest after of lifetime of work began to crystalize.

Once this happened, then a notion of “early retirement” became possible. And we can see society explore the idea through books and magazine articles.

The books tend to be academic and of little interest to us. The magazine articles, on the other hand, are interesting — especially since they portray early retirement as an opportunity to pursue other paid work. (This flies in the face of an attitude prominent in some quarters today, an attitude that says “you can't be retired if you continue to work”. That idea was bullshit sixty years ago and it's bullshit today.)

Final Thoughts

So, if financial independence isn't a new concept, why hasn't it caught on? If people have been preaching the power of financial freedom since 1872 (or before), why don't more people know about it? I think there are a number of reasons.

Samuel Smiles — and people who adhere to his Victorian ideas — would argue that the reason F.I. hasn't become more popular is that people are weak. As progressive as he was in his day, Smiles believed that poor people were poor because they made poor choices. There are many people who would make the same argument today. And while I certainly believe that poor choices can be a barrier to wealth, I think they're a barrier for the middle and upper classes, not the lower class. I believe that poverty is often a result of systemic issues.

Note: Let me be clear, though, that regardless the source of poverty, I believe strongly that it is up to the individual to elevate her financial position. It doesn't matter the reasons you're poor. If you'd like to escape poverty, it's up to you to make the choices required to do so. Then, after you've freed yourself, you can turn your attention to systemic issues, to helping other people rise up as well.

Perhaps the biggest change from 1872 to today is technology.

When Money and How to Make It was published, its reach was limited. First of all, it was expensive. The book cost $20 back then, which would be roughly equivalent to $400 in 2020. (You almost had to be financially independent to buy the book!) If you could afford to buy it, then what? Who could you share the info with? If you loaned the book to your sister or your neighbor, maybe you'd have a few people to talk about these ideas with, but mostly you were on your own.

Today, on the other hand, this information is ubiquitous. If you want to learn about financial independence and early retirement, there's almost too much material out there for you. And it's easy to find like-minded folks to talk with! There are Facebook groups, subreddits, blogs, podcasts, YouTube channels, and in-person meet-ups galore. Technology makes it easy to connect with other people who are interested in financial independence and early retirement.

But I think the real reason that F.I. ideas didn't catch on in 1872 (or 1919 or 1936 or 1957 or 1988) is simple: Most people just don't care. Some folks don't believe the concepts work. (They do.) Others don't believe the ideas apply to them and their situation. (They do.) And plenty of people simply aren't willing to wait. The pursuit of financial indepence requires trading short-term comfort for long-term security. Humans aren't hard-wired to think long term.

Because we're a myopic species, it's tough for us to plan five or ten or twenty years in the future. That was true 150 years ago. It's true today.

I'm not saying that the FIRE movement is going to fade away and be forgotten. I don't think it will, actually. But I do think that its appeal is limited. Most people are unwilling to make the choices and changes necessary to retire early. They're okay with the standard path…even though that means they'll be working until they're 65. Or 70. Or older.

I suspect that 150 years from now, some kid will be digging through a digital archive and discover the dozens of FIRE blogs from 2020. And he'll marvel at how the ideas he thought were original to him and his colleagues in 2170 have actually been around for decades. So, he'll whip up a hologram for HoloTube and share what he's learned about the history of financial independence and early retirement.

Because — to quote George Santayana — “those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it”.

from Finance https://www.getrichslowly.org/history-of-financial-independence/ via http://www.rssmix.com/

0 notes

Text

How Intellectuals Cured ‘Tyrannophobia’

Almost 400 years ago, English philosopher Thomas Hobbes wrote a book scoffing at tyrannophobia—the “fear of being strongly governed.” This was a peculiar term that Hobbes invented in Leviathan, since civilized nations had feared tyrants for almost 2000 years at that point. But over the past 150 years, Hobbes’ totalitarianism has been defined out of existence by apologists who believe that government needs vast, if not unlimited power. Hobbes’ revival is symptomatic of the collapse of intellectuals’ respect in individual freedom.

Writing in 1651, Hobbes labeled the State as Leviathan, “our mortal God.” Leviathan signifies a government whose power is unbounded, with a right to dictate almost anything and everything to the people under its sway. Hobbes declared that it was forever prohibited for subjects in “any way to speak evil of their sovereign” regardless of how badly power was abused. Hobbes proclaimed that “there can happen no breach of Covenant on the part of the Sovereign; and consequently none of his subjects, by any pretense of forfeiture, can be freed from his subjection.”

Hobbes championed absolute impunity for rulers: “No man that hath sovereign power can justly be put to death, or otherwise in any manner by his subjects punished.” Hobbes offered what might be called suicide pact sovereignty: to recognize a government’s existence is to automatically concede the government’s right to destroy everything in its domain. Hobbes sought to terrify readers with a portrayal of life in the “state of nature” as the “war of all against all” that made even perpetual political slavery look preferable. John Locke, in his Second Treatise of Government published a few decades later, scoffed at Hobbes’ “solution”: “This is to think that men are so foolish that they take care to avoid what mischiefs may be done them by polecats and foxes, but are content, nay think it safety, to be devoured by lions.” As Charles Tarlton, a professor at the State University of New York in Albany, noted in a superb 2001 article in The History of Political Thought, Hobbes “despotical doctrine” rests upon “an absolute and arbitrary political power joined with a moral demand for complete, simple and unquestioning political obedience and, second, the concept that no action of the sovereign can ever be unjust or even criticized.”

Hobbes’ treatise succeeded in making “Leviathan” the F-word of political discourse. In the century after Hobbes wrote, there was rarely any doubt about the political poison he sought to unleash. David Hume, writing in his History of England declared that “Hobbes’s politics were fitted only to promote tyranny.” Voltaire condemned Hobbes for making “no distinction between kingship and tyranny … With him force is everything.” Jean Jacques Rousseau condemned Hobbes for viewing humans as “herds of cattle, each of which has a master, who looks after it in order to devour it.”

Hobbes’ views were derided as long as political thought was tethered to the Earth. Unluckily for humanity, philosophers found ways to sever ties to both history and reality. The most influential political philosopher of the 19th century may have been Germany’s G.W.F. Hegel. Hegel proclaimed, “The State is the Divine Idea as it exists on earth” and is “the shape which the perfect embodiment of Spirit assumes.” Hegel also declared that “the State is … the ultimate end which has the highest right against the individual, whose highest duty is to be a member of the State.” Hegel had a profound influence on both communism (via Marx) and fascism. Political scientist Carl Friedrich observed in 1939, “In a slow process that lasted several generations, the modern concept of the State was … forged by political theorists as a tool of propaganda for absolute monarchs. They wished to give the king’s government a corporate halo roughly equivalent to that of the Church.”

By the twentieth century, as Tarlton noted, “Hobbes’s interpreters and commentators had worked to make Hobbes’s appalling political prescriptions more palatable.” Experts scoffed at “tyrannophobia” because they believed tyrants were necessary to “fix” humanity.

Hobbes’ revival in America was aided by John Dewey, probably the philosopher with the most impact on public policy in the first half of the 20th century. In 1918, Dewey shrugged off Hobbes’ affection for despotism: “Undoubtedly a certain arbitrariness on the part of the sovereign is made possible, [it] is part of the price paid, the cost assumed, in behalf of an infinitely greater return of good.” And why presume “an infinitely greater return of good”? Because the government would be following the prescriptions of Dewey and his intellectual cronies. Two years earlier, Dewey championed government coercion as a social curative: “No ends are accomplished without the use of force. It is consequently no presumption against a measure, political, international, jural, economic, that it involves a use of force.” Dewey declared that “squeamishness about [the use of] force is the mark not of idealistic but of moonstruck morals.”

Two decades later, Dewey discovered utopia during a visit to Moscow and proclaimed that the Soviet people “go about as if some mighty, oppressive load had been removed, as if they were newly awakened to the consciousness of released energies.” Dewey had no qualms about the artificial famine that Stalin caused in the Ukraine that killed more than five million peasants. Perhaps Dewey agreed with Stalin: “One death is a tragedy, a million deaths a statistic.”

President Franklin Roosevelt never invoked Hobbes but his Hobbesian approach to power made FDR a darling of the intelligentsia. In his first inaugural address, FDR called for a Hobbesian-like total submission to Washington: “We now realize… that if we are to go forward, we must move as a trained and loyal army willing to sacrifice for the good of a common discipline, because without such discipline no progress is made, no leadership can become effective.” The military metaphors and call for everyone to march in lockstep was similar to rhetoric used by European dictators at the time. Roosevelt sometimes practically portrayed the State as a god. In his 1936 acceptance speech at the Democratic National Convention, he declared, “In the place of the palace of privilege we seek to build a temple out of faith and hope and charity.” In 1937, he praised the members of political parties for respecting “as sacred all branches of their government.” In the same speech, Roosevelt assured listeners, in terms Hobbes would approve, “Your government knows your mind, and you know your government’s mind.”