#The ancient Greeks believed a stone fell to the ground

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

"The ancient Greeks believed a stone fell to the ground" - Eldrid Lunden - Norway

Translator: Annabelle Despard (Norwegian)

The ancient Greeks believed a stone fell to the ground because it belonged there

We believe in gravity. But we feel that the Greeks’ idea is much more poetic

#The ancient Greeks believed a stone fell to the ground#Eldrid Lunden#Norway#translation: norwegian#poem#poetry#poems from around the world

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Fascinating History of Opals: From Ancient Myths to Modern Jewelry

Opals have captivated human imagination for centuries, dazzling with their kaleidoscopic play-of-color and mysterious origins. This unique gemstone has been intertwined with mythology, revered by ancient civilizations, and celebrated in modern jewelry. From the Roman Empire to contemporary designers, the story of opals is as mesmerizing as the stone itself.

Ancient Myths and Beliefs

The allure of opals dates back thousands of years, with myths and folklore surrounding their mystical properties. Ancient Romans considered opals to be the most powerful and precious gemstone, believing they contained the beauty of all other stones combined. Pliny the Elder, a Roman scholar, described opals as possessing the fiery glow of rubies, the sea-like blues of sapphires, and the rich green of emeralds.

Greek mythology suggested that opals were formed from Zeus’ tears of joy after his victory over the Titans. The Greeks associated opals with prophecy and foresight, believing they bestowed wisdom upon their wearers. Meanwhile, Arabian legends claimed that opals fell from the heavens in flashes of lightning, which gave them their shimmering brilliance.

Australian Aboriginal lore holds a particularly rich history concerning opals. According to one legend, the Creator descended to Earth on a rainbow and, upon touching the ground, left behind colorful opals in his wake. This ties into the concept of opals being a gift from the divine, carrying celestial energy.

The Rise and Fall of Opal’s Reputation

During the Middle Ages, opals were believed to bring good fortune. Their shifting colors made them symbols of invisibility, and European nobles often used them as protective talismans. However, in the 19th century, opals gained an unfortunate reputation for being unlucky. This superstition was largely fueled by Sir Walter Scott’s novel Anne of Geierstein, in which an opal worn by the protagonist changes color when she is in distress and ultimately leads to her demise. The book’s immense popularity led to a sharp decline in opal sales, and the gemstone was avoided for decades.

Queen Victoria, a fervent admirer of opals, played a pivotal role in restoring their status. She frequently gifted opals to her daughters and members of the royal court, dismissing the superstition as baseless. Her endorsement helped bring opals back into fashion, particularly in England and Europe.

Opal Mining and the Australian Boom

The discovery of opal deposits in Australia in the late 19th and early 20th centuries revolutionized the gemstone industry. Australia quickly became the world’s leading supplier of opals, producing 95% of the global supply. The famous opal fields of Lightning Ridge, Coober Pedy, and Andamooka unearthed some of the most exquisite specimens, including the renowned Olympic Australis, one of the largest and most valuable opals ever found.

Ethiopia also emerged as a significant source of opals in the 21st century, particularly from the Welo region. Ethiopian opals possess remarkable transparency and color play, making them highly sought after by collectors and jewelers alike.

Modern-Day Popularity and Jewelry Trends

Today, opals continue to enchant gemstone lovers and jewelry designers worldwide. Their mesmerizing play-of-color makes them ideal for statement pieces, and they are often set in rings, necklaces, and earrings. Opals are also the official birthstone for October, further solidifying their place in the jewelry market.

In modern jewelry, opals are frequently paired with diamonds, sapphires, and gold to enhance their brilliance. High-end designers incorporate opals into contemporary styles, embracing their organic patterns and iridescent hues. The rise of sustainable and ethical mining has also led to a renewed appreciation for responsibly sourced opals, making them more desirable than ever.

Conclusion

From ancient mythology to modern-day luxury, opals have traversed an incredible journey through time. Once believed to contain divine magic, then unfairly deemed unlucky, and now revered as one of the most unique gemstones, opals have proven their timeless appeal. As jewelry trends continue to evolve, this extraordinary gemstone remains a symbol of beauty, mystery, and history, ensuring that its legacy will continue to shine for generations to come.

0 notes

Text

Pegasus, the majestic flying horse of Greek mythology, has captured the hearts and imaginations of people all over the world. However, as it turns out, this winged creature also has a practical impact on our everyday lives – particularly in the bedroom, where toilet plungers are often found.

One might wonder, why would a mythical creature like Pegasus have any influence on the placement of toilet plungers? The answer lies in the connection between Pegasus and the element of water, which is essential for both the horse's existence and the effectiveness of a toilet plunger.

In Greek mythology, Pegasus was born from the blood of Medusa, a Gorgon with the power to turn anyone who gazed upon her into stone. Pegasus sprang forth from Medusa's corpse after she was beheaded by the hero Perseus, and is said to have struck his hoof against the ground and brought forth a spring of water, known as the Hippocrene, which became a source of inspiration for poets.

This association with water makes Pegasus not only a symbol of creativity and inspiration, but also of purification and cleansing. In ancient Greek society, horses were often used for bathing and grooming, and Pegasus, being a winged horse, could easily access hard-to-reach places and provide a thorough cleaning. This connection to cleanliness and sanitation is carried over to our modern era, where toilet plungers are essential tools for maintaining a clean and functional bathroom.

But why specifically in the bedroom? In Greek mythology, Pegasus is often depicted as a faithful companion to his rider, Bellerophon. It is said that when Bellerophon fell from Pegasus' back, he landed in a pile of manure, and Pegasus' hoof miraculously turned the pile into a well of pure water. This legendary incident is believed to have taken place in the bedroom, as Greek bedrooms often had an adjacent courtyard where animals were kept. Thus, the bedroom became closely associated with both Pegasus and the element of water.

In addition, the bedroom is often the most private and intimate space in a household, and as such, it is important to keep it clean and hygienic. This is where the trusty toilet plunger comes in. Due to Pegasus' associations with cleanliness and purity, it makes sense that we would keep a tool for maintaining the cleanliness of our toilets within reach in this sacred space.

In conclusion, the placement of toilet plungers in bedrooms may seem odd at first glance, but its connection to Pegasus and the element of water sheds light on this curious geographic phenomenon. So the next time you reach for your plunger in the bedroom, remember the ancient stories of Pegasus and the important role he plays in our daily lives – even in the most unexpected ways.

0 notes

Text

The Cromlech of Stonehenge

The Stonehenge Cromlech, an ancient marvel towering majestically in the British countryside, represents the most famous and imposing stone circle, known as a cromlech. This extraordinary monument is composed of a circle of colossal megaliths, imposing upright stones that support horizontal connecting lintels, some of which rise impressively in height. Stonehenge is an ancient and fascinating example of a trilithic system, a structure built with three main elements: two vertical uprights and a horizontal lintel.

While the impressive stones of Stonehenge underwent modifications during reconstruction work in the first half of the 20th century, they still maintain an alignment that some believe faithfully reproduces the original one. This precision has led to speculation about Stonehenge's possible role as an ancient astronomical observatory, particularly relevant during solstices and equinoxes. However, the interpretation of its use for this purpose remains a subject of debate.

In addition to attracting tourists from around the world, Stonehenge holds deep significance for followers of Celtic traditions, Wicca, and other neopagan religions. Throughout its history, Stonehenge has also played a significant role as the site of a free music festival held from 1972 to 1984.

However, 1985 marked the end of this festival as the British government banned it following a violent clash between the police and some participants, an incident known as the Battle of Beanfield. Stonehenge, with its rich and varied history, continues to be a source of mystery, fascination, and spirituality for those who visit.

Detailed Description of Stonehenge:

The Altar Stone:

At the center of Stonehenge stands the imposing block of green sandstone known as the Altar Stone. This majestic monolith reaches a height of five meters and captivates with its imposing presence. The stone is carved from an extremely hard variety of siliceous sandstone, naturally sourced from about thirty kilometers to the north on the Marlborough Downs. Its geographical origin adds an element of mystery, highlighting the logistical complexity of ancient builders.

Inner Structure – Bluestone Horseshoe:

Within the main circle is the complex structure known as the Bluestone Horseshoe. This formation consists of much smaller stones, each with an average weight of four tons. Surprisingly, these stones traveled a long distance to reach Stonehenge, originating from the Preseli Mountains in southwestern Wales. The variety of stones, including dolerite, rhyolite, sandstone, and volcanic limestone ashes, adds a unique dimension to the geological complexity of Stonehenge.

The Heel Stone:

Once known as the Friar's Heel, this stone tells a captivating story related to its origins. According to a popular tale dating back at least to the 17th century, the devil himself purchased these stones from a woman in Ireland, wrapped them, and transported them to the Salisbury Plain. While one of the stones fell into the River Avon, the others were strategically placed on the plain. The devil, confident in his cunning, exclaimed, "No one will ever find out how these stones got here." However, a wise friar retorted, "That's what you think!" In response, the devil hurled one of the stones at the friar, striking him in the heel. The stone embedded in the ground, where it remains anchored to this day, a silent witness to an ancient showdown between good and evil.

Historical Mentions and Scientific Investigations of Stonehenge:

The historical roots of Stonehenge extend into the mists of time, capturing the interest of ancient writers and modern scholars. In the 1st century BCE, the Greek writer Diodorus Siculus mentioned a place similar to Stonehenge in his Bibliotheca Historica, referring to an island called Hyperborea, beyond the Celts, dedicated to Apollo. Some scholars in the past have speculated that Hyperborea could indicate Britain, and the spherical temple mentioned by Diodorus could be an early reference to Stonehenge.

However, archaeologist Aubrey Burl has cast doubts on this theory, as some parts of Diodorus's description do not seem to fully reconcile with Stonehenge and its surrounding geography. Burl particularly highlighted the mention of Apollo "touching the earth at a very low height," a phenomenon incompatible with the latitude of Stonehenge.

The earliest detailed investigations into Stonehenge date back to 1640 when John Aubrey proclaimed the monument the work of Druids, an idea later amplified by William Stukeley. Aubrey, a pioneer in site analysis, created the first detailed drawings, laying the groundwork for a better understanding of its form and significance. From 1740 onwards, architect John Wood conducted further research, interpreting Stonehenge as a site for pagan rituals. This interpretation, criticized by Stukeley, reflected the beliefs of the time about the nature of the monument.

Isaac Newton, influenced by Stukeley, undertook a symbolic analysis of Stonehenge's stones in the context of the non-geocentric configuration of the solar system. This perspective, derived from his conception of a perfect model based on the Temple of Jerusalem, suggested that the builders of Stonehenge possessed ancient scientific knowledge.

Radiocarbon dating has revealed that Stonehenge underwent construction phases between 3100 BCE and 1600 BCE, with the circular earthen mound and ditch built in 3100 BCE. The visible stones today mainly belong to the Stonehenge 3 phase (2600 BCE – 1600 BCE). Recent research, such as the 2020 XRF spectrophotometry, has provided new data, indicating a dating of 2500 BCE.

Theories about the construction of Stonehenge, once tied to the Druids, have been challenged considering the late spread of Celtic society. Moreover, the practice of Druid rituals in forests suggests that Stonehenge might not have been the ideal place for their "earth rituals." Ongoing scientific research is gradually unraveling the mysteries of this monument, shedding new light on its past and true nature.

Controversies and Discoveries:

Restorations and Disputes:

Since the early 19th century, a series of modifications and restorations have shaped Stonehenge's current appearance. Victorian engineers, with zeal and preservation intentions, positioned many of the fallen stones in their current locations. Recent research indicates that these restoration works continued into the 1970s, introducing substantial changes to the original arrangement. Archaeologists from English Heritage acknowledge that, without these interventions, Stonehenge would look significantly different today. Very few stones still retain their original positions, erected millennia ago.

Discoveries in the Vicinity:

Just 3 km from Stonehenge, researchers from the National Geographic Society discovered a village dating back to 2600 BCE. This settlement, consisting of approximately twenty-five small dwellings, is presumed to have accommodated builders of the complex or participants in specific ceremonies. This discovery provides a broader insight into the life and social organization of ancient times, connecting Stonehenge's history to a wider context.

Prehistoric Astronomical Observatory:

Stonehenge's function as a prehistoric astronomical observatory is a subject of debate. The monument's axis is oriented towards sunrise during summer solstices, suggesting a connection with astronomy. However, this orientation does not occur during winter solstices, fueling mystery and conflicting interpretations about its real utility. The complexity of Stonehenge continues to intrigue scholars and enthusiasts, and its alleged astral function adds a layer of mystery to its history.

Denial of Roman Theories:

Contrary to the theories of Inigo Jones and others, suggesting that Stonehenge could have been built as a Roman temple, the historical fact that the Romans first arrived on the British Isles with the arrival of Julius Caesar in 55 BCE negates these hypotheses. Stonehenge, with its intricate history and connection to distant eras, continues to challenge and fascinate those seeking to unravel its secrets hidden over millennia.

Theories about Construction:

Extraction and Transport of Large Stones:

The majestic stones of Stonehenge, some of which weigh an impressive 25/50 tons and are made of gneiss, were extracted from a hill located 30 km from the archaeological site. The process of transporting these massive stones involved the use of sledges sliding on wooden rollers, pulled by dozens of men through likely collective efforts. This titanic operation represents an extraordinary expression of engineering capabilities of the time.

Origin of Smaller Stones:

The smaller stones, an integral part of Stonehenge, were extracted from various locations, expanding the logistical complexity of the project. A site just 3 km away contributed some of these stones, while others were extracted from more distant sites, including a location in Wales over 200 km away. The variety of sources underscores the geographic scope of the efforts made for the construction of Stonehenge.

New Research and Rejection of Previous Theories:

A study published in June 2018 challenged the previous theories of geologist Herbert Henry Thomas from 1923, which had influenced the scientific community regarding specific extraction sites and stone transport methods. The new research suggests that the Bristol Channel was not used as previously supposed, but that the stones might have been transported through internal roads. Additionally, it is hypothesized that the Altar Stone could come from Senni Beds, a sandstone formation extending through Wales to Herefordshire in eastern Wales. This conceptual shift sheds new light on the intricate logistics of Stonehenge.

Erection and Construction Process:

The raising of the vertical stones involved a complex process. Initially, the stones were dragged to a hole in the ground, then slid into the hole using a lever system resting against a "castle" of logs. Once in the upright position, the stones were secured using ropes, and the hole was filled with stones. The assembly of the lintel occurred gradually, using wooden scaffolding and levers, highlighting the technical mastery of Stonehenge's prehistoric builders.

Legends and Myths Surrounding Stonehenge:

Association with King Arthur:

Stonehenge is shrouded in the legend of King Arthur, where the wizard Merlin would have requested the removal of the monument from Ireland, originally built on Mount Killaraus by giants who transported the stones from Africa. After being rebuilt near Amesbury, the legend states that Uther Pendragon and later Constantine III were buried inside the stone circle. This mythical connection adds an epic charm to Stonehenge's story, intertwining the ancient monument with the legends of one of Britain's most famous rulers.

Similar Neolithic Circles:

Stonehenge is not the only prominent Neolithic circle, and several similar structures date approximately to the same era. Among these, the "Ring of Brodgar" in northern Scotland offers another example of Neolithic complexity. Additionally, a similar circle, dating to around 4900 BCE, is found in Goseck, Saxony-Anhalt, Germany. These structures suggest the presence of ancient communities sharing ideas and construction practices.

Calendar Circle at Nabta Playa:

A complex known as the "Calendar Circle," originally built at Nabta Playa and now displayed at the Nubian Museum in Aswan, predates Stonehenge by at least a thousand years. This ancient structure, with its astronomical implications, highlights the diversity and spread of construction practices in ancient times.

Megalithic Circles in Italy:

In Italy, several examples of megalithic circles are found in Sardinia, adding a touch of mystery and global connection. The "Circle of Li Muri" in Arzachena and the "Circle of Pranu Muttedu" in Goni are examples of ancient megalithic achievements that emphasize the presence of common practices in different regions of the ancient world. These testimonies speak of a past rich in symbolism and meaning, where communities expressed their connection with the divine through majestic stone constructions.

#StonehengeWonders#AncientAstronomy#NeolithicMysteries#HistoricalMonuments#ArchaeologicalDiscoveries#CelticSpirituality#AncientMusicFestival#DruidicTraditions#PrehistoricEngineering#HistoricalLegends#StonehengeHistory#MegalithicWonders#NeolithicCircles#AstronomicalObservatories#ArchaeologicalInsights#AncientRituals#StonehengeFacts#MysteriousPast#CulturalConnections#AncientCivilizations#MegalithicHeritage

0 notes

Text

The last harrowing week of December, a month after the fall of the Black Org and four hours into Shinichi-not-Conan’s massive multiple organ failure, Haibara finally turns on her heel and tells him, “Let’s fuse.”

a gift exchange fic for @subwalls <33 merry chrmbs. i wrote a 1.5k fic and then a 1.2k infodump KDFHJS

as with whenever i write hnk or steven universe, my mineral special interest goes Hyperdrive. mineral assignments and fusions listed under the cut

shinichi - lapis lazuli. hardness 5-6. often ground to make the vibrant blue pigment used in rennaissance paintings, and was used to paint the girl with a pearl earring. shinichi’s stone is originally purely blue, which is the most valuable form of lapis lazuli consisting mostly of lazurite and sodalite and i think matches pre-series shinichi’s arrogance and perfectionism; most readily available lapis lazuli has visible streaks of calcite or pyrite, some of which stains the rest of the gem a greenish color and lowers the commercial value of it. in terms of symbolism, lapis lazuli is thought to protect against mental attacks and bring peace, honesty, and self-awareness. i liked the blue with shinichi, liked the connection of the symbolism with his character, and lapis lazuli is one of my favorite minerals. in terms of story, i imagine lapis isn’t an entirely uncommon gem to have, and the apoptoxin develops stress fractures in shinichi’s gem that he passes off as calcite veins when he’s conan. these stress fractures grow as the story continues. i think haibara’s intermittent cures make them worse.

ai - onyx. hardness 6.5-7. specifically black onyx, which is most common and my favorite naturally occurring pattern of onyx. the name itself is rooted in the greek word for “claw” or “fingernail” due to cupid of roman mythos cutting his mother venus’ nails with his arrows. they fell into the sea, where they then became the onyx gemstone. onyx is believed to teach the wearer to rely on their own powers and persevere. i felt the black and white banding of black onyx suited haibara’s continuous moral ambiguity, especially when her character was first introduced, and i liked that on the mohs scale onyx is harder than lapis.

ran - anhydrite, also known as angelite. hardness 3.5. it’s generally white with a pearly luster. when exposed to water (hydrated) it becomes the commonly known gypsum (the non-crystal form of selenite), which is used in many different forms (construction, agriculture, sculpture, and medicine, to name a few). the softness of the mineral in contrast with its various commercial uses seemed to suit the damsel-in-distress archetype ran is meant to fit despite being a talented and brave martial artist and particularly sharp-tongued to boot. anhydrite is believed to be very calming and promote the holder’s self-belief and self-worth.

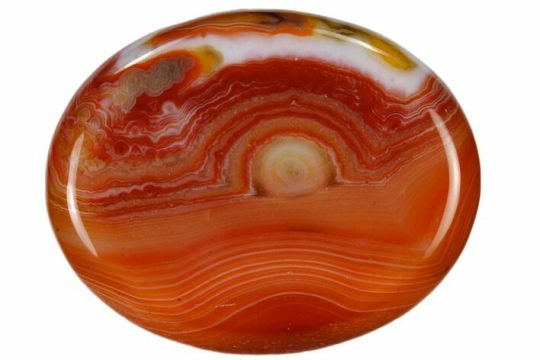

heiji - carnelian. hardness 6.5-7. it’s usually this really deep, egg-yolky orange-yellow color that i associate w heiji. it’s often used interchangeably with sard but they’re considered distinct subvarieties, with carnelian usually being softer and lighter in color. i imagine heiji’s father is sard. carnelian was believed to be a stone of courage both by the romans and the ancient egyptians and used to amplify confidence and strength. i liked the symbolism with heiji’s bullheadedness; he’s always felt more physical btwn himself and shinichi to me.

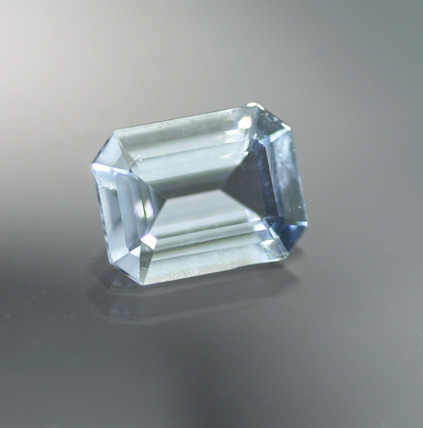

kaito - euclase. hardness 7.5. shit toughness, very brittle. its name literally translates to “easily breakable.” it’s usually a mix of colorless and light blue—conveniently fitting into kaito’s color scheme—and is believed to promote strength and clarity. it’s beautiful and i like the symbolism of kaito running around stealing precious stones, which in this verse are probably poofed versions of real people or something. it’s entirely possible pandora is the presumed-dead kuroba toichi or even that it’s shinichi’s gem (smth smth theyre both blue, smth smth pandora’s essence is in the apoptoxin, smth smth it would tie the franchises together). i also just like euclase.

gin - moissanite. hardness 9.25. a silicon carbide originally discovered in a meteor and mistakenly identified as diamond. it’s vitreous and colorless. i’m obsessed with it. it’s often used as a diamond alternative (buy moissanite instead of diamond, its cheaper and doesnt use forced labor bc its lab grown) and it can withstand huge pressures. it’s birefringent, which means it splits up light that’s aimed at it (diamonds don’t do that) and it’s thermoluminescent. it ranks higher on the refractive index than diamond WHICH MEANS IT’S LITERALLY SHINIER THAN DIAMOND like. why r people still buying diamonds when moissanite exists. anyway gin matched the colorlessness/whiteness of moissanite as well as its hardness and the fact that it’s a diamond alternative (i think karasuma is probably a diamond).

less comprehensive and but no less analytical list of fusions:

ran & shinichi: kyanite. hardness 4.5-5 parallel to one axis and 6.5-7 perpendicular to that axis. blue and white; metamorphic rock like lapis. one of my favorite minerals. kyanite is bright-eyed and somewhat naive and would run forever if they could.

ran & conan: sillimanite. hardness 7. Can Sometimes Be Blue and thin section is white. LISTEN. its perfect. i chose it bc it has the exact same chemical formula as kyanite (Al2SiO5), it just differs in physical properties. given conan’s fusion volatility i cannot imagine he hasn’t accidentally fused w ran at least once and given himself, prof agasa, ai, and heiji all a minor heart attack. for Maximum Drama it probably happened during the desperate revival arc. sillimanite hasn’t been together long enough to know who they are but i imagine they’re quite sad.

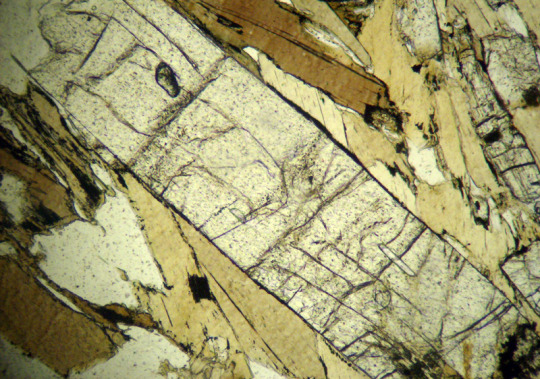

(cut and polished blue sillimanite + thin section of sillimanite)

conan & ai: boleite. hardness 3-3.5. blue and black and endearingly cubic. often occurs in twinned crystals, which kinda works w ai and shinichi’s character parallels and similar situations. broke my own rule of having the fusion mineral share a mineral group with one of the constituent gems, but i forgive myself bc boleite was so perfect. runner up option was dumortierite which is a tectosilicate like chalcedony (onyx) and lazurite (primary mineral in lapis lazuli).

conan & heiji: fire agate. hardness 6-7. blue to yellow to red. carnelian is a type of chalcedony and agate is a type of chalcedony. i imagine fire agate is fierce and foulmouthed and only knows how to be gentle when he’s reminded. i think he’s also a little too honorable for his own good.

conan & kaito: alexandrite. hardness 8.5. minty blue but changes color to red in incandescent light (example linked), which is a quality i thought suited conan and kaito. alexandrite is an oxide mineral which means it again does not share a mineral group with conan or kaito but it’s a beryllium aluminate and euclase’s chemical formula contains both beryllium and aluminum goddamn it. alexandrite is quirky but focused and can be a little intense.

#detective conan#detco#case closed#edogawa conan#kudo shinichi#haibara ai#hattori heiji#mouri ran#fusion au#minerals#idk i need to add that tag the people need to know about my Problems#chrys writes

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

TOP 3 Legends About Amber

TOP 3 Legends About Amber

Avicenna also wrote about the healing properties of amber.

In ancient times, it was believed that there was no disease that could not be cured with amber. It is also popularly known as the "sunstone". The succinic acid found in it and other types of amber increases the bioactive elements in a person in an effective and natural way.

Here are some legends related to this wonderful creation of nature:

Legend 1:

Phaethon in ancient Greek mythology was the son of Helios (Phoebus, an epithet later given to Apollo) and the oceanid Clymene. Phaethon boasted to his friends that he was the son of the sun god. However, they refused to believe him and Phaeton went to his father, who promised him everything he asked for. Phaethon asked to drive his father's golden chariot for a day. Helios tried to dissuade him, but to no avail - Phaethon was adamant. When the day came and he drove the chariot, he panicked and lost control of the white horses he was driving. The chariot caught fire, the earth caught fire. Africa has become a desert. The waters and rivers boiled. Earth would have perished if not for Zeus. He forced himself to strike the horses, the chariot, and the Phaeton with lightning. The white horses ran away - only the Erinyes could find them and bring them back. His mother, Klimena, searched for his ashes on the ground for a long time. Finally she reached the banks of the Eridanus River. Phaethon's sisters - the Heliads - wept on her shore inconsolably. Finally, Zeus got tired of their tears and turned them into fir trees. Then everything on earth began to return to the old way. Only the desert and the Milky Way remain as reminders of the recklessness of Helios and his son.

But even now transformed into trees, the sisters continued to cry. Their tears fell and turned into resin from which amber was later formed. Years later, the sea still spills their amber tears on its shores...

Legend 2:

Norse legend represents amber in the form of tears of the goddess of love and fertility Freya, who mourns her missing husband.

Legend 3:

The legends of Vedic Russia describe amber in a different way - as joy, as a great gift that all people of the world can use for healing. In Russia, the Alatyr stone had a sacred meaning. The stone possessed great magical power as it was a scaled-down copy of the universe. The Alatyr-stone was revered as the father of all stones. This is proven by the "Deep Book" (modern "Pigeon Book") - this is a Slavic spiritual verse that tells about the origin and integrity of the world.

Legends or not, amber still enjoys great attention to this day, did you know that a stone must be at least 1 million years old to be classified as amber? If you want to own a piece of jewelry made of amber, you can check here - kehlibareno.com

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

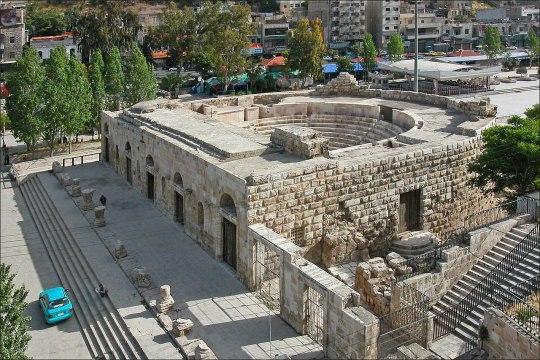

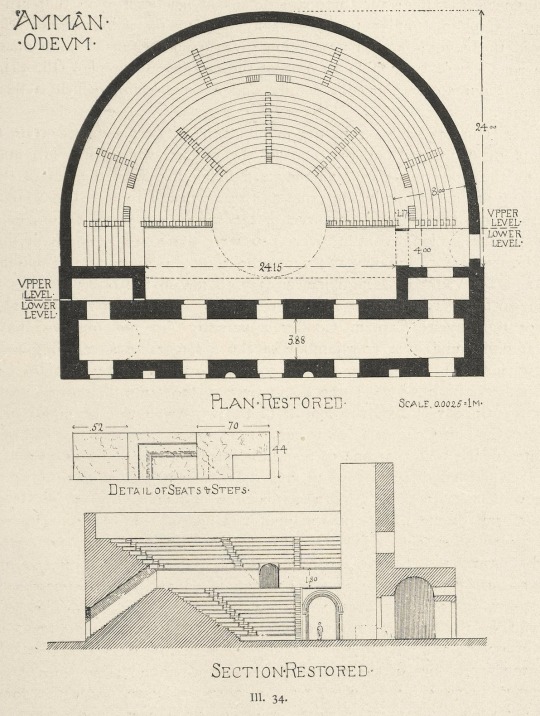

Odeon of Amman

Philadelphia (Amman), Jordan

2nd century CE

500 seats

Odeon ("singing place") is the name for several ancient Greek and Roman buildings built for music: singing exercises, musical shows, poetry competitions, and the like. Archaeologists have speculated that the Odeon of Amman was most likely closed by a temporary wooden roof that shielded the audience from the weather.

This Odeum is a Roman one, built in the 2nd century CE, at the same time as the Roman Theatre next to it.

Sources and more text below.

“The small theatre, or odeum, faces west upon the open space in front of the great theatre. Its southwest angle is about 5 m. east, and 14 m. north of the northeast angle of the theatre. It was built up entirely from the ground level and consisted of an outer west wall with five entrances in it, an inner wall, or proscenium, connected with the outer wall by a tunnel vault, two massive towers which formed the parascenia, and a small cavea divided by a single praecinctio. Of these parts, the first, or western wall, with three of its portals is standing to the height of one story; the doorways on the ends have fallen with the collapse of the angles, leaving one jamb of each with the springers of the relieving arches above them; the inner wall is partly preserved, and portions of the vaulting of the passage between the two walls are still in place; the southern tower is intact in two stories, and its west wall rises to a height of about 15 meters, but the opposite tower is a heap of ruins. The exterior curve of the cavea may still be traced at certain points; but the interior is filled with a mass of debris caused by the collapse of the northern tower and the high wall of the scaena, both of which fell inward. The ruin must have long served as a quarry; for almost all the seats that are not buried in debris have been removed. It was possible for me to find only short sections of four seats, at the extreme end on the south, and here I was also able to secure the measurements of the praecintio. It is plain that this building, though badly ruined, in 1881, when Captain Conder gathered the materials for his plan1 of the odeum, was not in the demolished condition in which we found it twenty-three years later·, for there are details in his description that are not to be found today. Captain Conder published only a plan on a very small scale without any details in the cavea; but his description gives a number of accurate measurements. With these as a check I am able to present the accompanying plan (Ill. 34), for which I cannot lay claim to accuracy in details, and a cross-section which is based largely upon conjecture. Plan. It is not possible, from the minuteness of its scale, to ascertain the precise measurements of Captain Conder’s plan of the odeum, where they are not definitely mentioned in the text; but so far as they are obtainable with the aid of the scale of feet given, they are substantially the same as those which I took. The whole structure, from the front wall to the exterior curve of the cavea, measures 35 m., or, according to Captain Conder’s plan, a little over 100 feet; the extreme width of the cavea is 40 in.; in Conder’s plan, about 125 feet; the stage building, at the middle, through both walls and the vaulted passage measures 7.48 m., in the other plan 25 feet. The old plan gives but three portals in the west wall, and makes this wall shorter than the width of the cavea; Captain Conder apparently did not observe that this wall terminates at either end in a door-jamb with the springers of a relieving arch over it; one of these jambs is shown in the photograph3 published by Captain Conder, the other may be seen in Ill. 35. These doors were of the same dimensions as the others, and, when they are restored, the length of the west wall will be equal to the width of the cavea. Captain Conder shows towers projecting inward at either end of the scaena wall; he states in the text that one of these towers measures 11 feet east and west, and 25 feet north and south. By this he must have meant that the north side adjoining the scaena wall measures 11 feet, and that the east wall was 25 feet long outside; for the south wall of the tower, now standing, is nearly 5 m. long. The earlier plan moreover places the centre of the semicircles of the cavea upon a line connecting the angles of these towers; but such a centre will not give a radius long enough to touch the rear curve of the cavea, which we agree is 35 m. from the west wall, without increasing the width of the cavea which we know to be 40 m. The measurement from the wall of the praecinctio at one end, to the corresponding point opposite is 24.15 m. In my plan I have therefore moved the centre backward 4 m. and I have constructed the semicircles of the cavea within the prescribed dimensions. This arrangement gives a space 4 meters wide for the paradoi. Down under the debris on the north side I measured a vault 4 meters wide, east and west, and a series of carved voussoirs of an arch that must have had a span of at least 3.70 m. I believe that the vault was the vault of the parados and that the arch-stones belonged to the arch which opened from it toward the orchestra. Captain Conder found seven rows of seats above the praecinctio; there could never have been more, if there were any passage at the top of the cavea: I found only four rows of seats, and no remains of seats below the praecinctio have ever been reported. Captain Conder describes three vomitoria from the cavea, one in the middle of the curve and one on either side. Only the barest remains of these are now visible. It is evident that these led from the praecinctio down to the level of the ground outside. The side of one such opening in the wall of the praecinctio is still to be seen on the south side at a distance of 5.75 m. from the tower wall. If the height of the praecinctio above the ground level be as I have indicated it, the steps of the vomitoria will descend from the praecinctio to the ground level at the outer curve of the cavea wall, at the same angle as the steps of the scalae within. These exits, of course, had vaults; these are likened, by Captain Conder, to segments of a hollow cone. Supers true hire. Satisfactory measurements of heights are out of the question in a ruin so filled with debris, unless the debris is removed; I have attempted to give a cross section, reconstructed in, what seems to me, the most logical method with the data in hand, and from what we know of the other buildings of a similar character. The ground level is, of course, unobtainable in a ruin of this character; but one may begin with the praecinctio, of which a small section is preserved, and place above it seven rows of seats with a narrow passage above them; parts of a scala are to be seen near the south end; the seats and the praecinctio terminate against the long wall of the tower. Of this much we may be reasonably certain; but the reconstruction of the cavea below the praecinctio depends entirely upon the existence of paradoi passing under the praecinctio and the upper section of seats at their extreme ends (Ill. 34). If there were paradoi at this point, a complete half circle of seats must be provided for within, i. e., east of, the paradoi, and the number of seats must be great enough to furnish height for the entrances on either side. I have assumed that the vault 4 m. wide is the vault of the parados, and that the voussoirs belonged to the arch of the entrance, and have therefore given a height to the lower section of the cavea, that will allow for ten rows of seats and a barrier about the orchestra 70 cm. in height. This arrangement provides for an orchestra 10.75 m. in diameter, and the semicircle of the orchestra, if continued to a circle would be tangent to the front line of a stage 2 m. deep. The standing portion of the south tower still towers above the rest of the ruin (Ill. 35), but in 1881, according to Captain Conder’s photograph, it was much higher, and was estimated by him to be 50 feet, about 17 m. high. This would give a scaena wall of at least that height. From indications in my photograph, as well as that published by Captain Conder, it is evident that there were large arched windows in the first story of the scaena wall above the vaulted passage at the rear of the stage: the jamb of the window and one voussoir are to be seen at the north side of the tower where a short section of the scaena wall is still in situ. It is very doubtful if the front wall of the odeum was carried up for an upper story; there is hardly enough debris to warrant it; yet this might have been carried away for building material; but the fact that the west wall of the tower, and the face of the section of the scaena wall still clinging to the tower, are both faced with draughted masonry, seems to show that they were exterior walls, although the rustication is carried to the base of the tower behind the vaulted passage of the postscenium. The outer wall is of finely dressed smooth ashlar, the portals were provided with arches of discharge above flat, three- piece lintels, the frame mouldings are of good but simple profile. On either side of the middle portal was a semicircular niche, and in the next spaces were rectangular niches with round arches. Beside each relieving- arch there were corbels in the wall which were more probably inserted to sustain the beams of a colonnade than to hold statues. The greater part of the ornamental details of the building has disappeared. The interior contains among its heaps of broken fragments several fine pieces of well wrought friezes and cornices which show that the scaena was richly adorned with entablat- ures. The mouldings of the seats were substantially like those of the great theatre (Ill. 34, detail), and have no resemblance to the detail given by Captain Conder, which must have been made from a broken example. “

(Text is told first hand by Howard Crosby Butler, who wrote the Syria series)

Sources: 1, 2

#art#Architecture#travel#history#roman#roman art#roman architecture#odeum#odeon#theatre#theater#amman#jordan#Philadelphia#2 ce#corinthian#roman theater#roman theatre

389 notes

·

View notes

Text

💔Rotten Love💔 //Twisted Wonderland Yandere Idia Shroud X Yandere Eliza X Reader// Part 1

GIF made by the amazing @flowerofthemoonworld. Okay, so this story is really going to have a Persephone x Reader x Hades vibe to it. If we can get this to 160 likes before July 12 than I’ll release part 2. For now, my goal is to make it a 4 part story with a bonus 5th fluff chapter. Also for this story reader will be GENDER NEUTRAL.

WARNING: Gore, Angst

💙 👻💙 👻💙 👻💙 👻💙 👻💙 👻💙 👻💙 👻💙 👻💙 👻💙 👻💙

There was always a cold, nostalgic air in the Ignihyde dormitory, a sort of homey sensation that made Eliza's heart skip a beat. Sure the dorm was quiet and secluded, unlike the ghost kingdom, there was barely anyone to talk to. Most may have even described it as "lonesome" and "boring". But to princess Eliza who had waited more than five hundred years to be with her prince charming, it was unadulterated, homespun bliss. Of course, there was still something missing, a tiny puzzle piece that refused to fit in with the rest of its kind, a stubborn little piece it was, yet all too important to paint the picture of her perfect life. That mulish fragment came in the form of her newly wedded husband, Idia Shroud.

"Idia~"

The "young" princess sang as she skipped over to where her "husband" was sitting, his posture crooked, like that of a scrunched up cat's. His long slender fingers where typing rapidly on that bizarre rectangular device that he all too attached to. Way too attached to, for Eliza's liking.

Eliza nuzzled her visage into the crook of the bleached-skinned boy's neck, taking in his smokey, ash-like sent. Her icy colored arms wafted over his shoulders, enclosing them his a tight embrace. Her fingers dangled over where his heart was, feeling tiny fast-paced pulses that sent a pleased blush to her face. "Idia let's go for a walk near that river. Please, my love! You haven't left this room since the reception!"

The taller male barely turned to look at her, preferring to instead to keep his eyes locked on his glowing blue screen. "Still busy Eliza" his cold dead voice was always so sharp and monotone whenever he spoke to her. It felt like someone was reaching into her rib cage and squeezing her decaying heart. Her voice cracked into a thousand tiny shards, as she tried to form a comprehensible answer. He might as well have told her to die again and rot in the deepest parts of hell. He doesn't love me....he'll never love me. The relation was like a heavy chronic toxic gas levitating overhead. Easy to overlook but still there, always there. Idia didn't move, if Eliza's arms weren't wrapped around his shoulders feeling every breath he took, she might have mistaken him for a statue. No, not a statue, she thought, some sort of sculpture of an ancient Greek God. A divine being set in stone resting in an altar, waiting for reparations and benedictions. 'I'd gladly pray at your feet every day. I'd sacrifice everything I had just for you to smile that charming smile at me'. The ghost thought to herself.

For an endless minute, the darkroom fell into a thick, suffocating silence. Neither Eliza nor Idia moved both too scared of breaking some invisible glass wall they had put up around them. However, no amount of serenity could dispose of the awkwardness, and annoyance Idia was beginning to feel. "You know" the lord of the dead began "maybe you should talk to the principle about join the school full time. It would give you more to do than breathing over my shoulder" despite Idia's tone harboring no malice, Eliza still flinched in shock. Her body going rigid, stiffening as if she was going into Rigor Mortis again.

HE DOESN'T WANT YOU HERE!

The voice in her head screamed,

HE HATES YOU!

Louder...

WHY CANT YOU LEAVE HIM ALONE

"Please stop" she whispered

YOU DON’T DESERVE YOUR PRINCE!

"If that's what you want" she finally replied in a broken voice.

"I'm... I'm only saying it for your sake," he muttered in a coaxing tone.

Deep down a delusional part of her wanted to scream that he was only saying all those harsh things for her own well-being. But she was still lucid enough to not believe those fallacies, imaginary words...Eliza perceived that her beloved prince Idia saw her as nothing more than a nuisance. One that he was far too eager to get rid of.

She couldn't bear the conversation any farther. Painfully slowly she peeled her arms off from around her so-called lover. In that taunting minute, Eliza swore she could feel billions upon billions of sharp needles piercing every piece of her dead body. She lingered in place staring at Idia's glowing, blazing hair. She didn't want to leave, she wanted to spend every second of her dead life with him! Touching him, kissing him, loving him! But he wouldn't love her! Why didn't he love her!! Without a customary goodbye or any form of acknowledgment, Eliza flew to the door. Swinging it open just a crack, wishing to slam it so hard that the whole underworld dorm would feel it. But alas she was still royalty and there was a politeness beaten into her every action. In the end after much debating, she closed the damn door quieter than a mouse. With a broken heart and eyes full of tears, princess Eliza began to hover up onto the surface of the school grounds.

WHY DOESN'T THAT SELFISH BASTARD LOVE ME!

A simple blaring thought that reverberated through Eliza's nonexistent skull as she marched through the glowing green halls of Night Raven College. Unlike Ignihyde, the rest of the school still felt rather alien and terrifying to the girl. She'd only been in the cafeteria for a short amount of time. Only to finish up her official marriage to Idia. After the marriage -and much persuasion from his friend with grey hair and glasses- Idia had carried Eliza in the traditional manner a groom must carry a bride, to the hall of mirrors and straight to Ignyhde. Neither of them had left Idia's room since then.

It was a rather short memory but one that always placed a smile on Eliza's face. Rather than remembering the halls, Eliza had been all too bewitched by Idia's shy golden gaze, his bloody red face, and his kissable thin blue lips. Such a darling memory that she would always cherish within her rotten heart.

But as the minutes ticked away and Eliza passed hallway after hallway all identical to one another, she soon began to wish that she'd paid more attention to the whereabouts of the school's rooms and offices. The headmaster's office seemed to be missing from this endless maze. Behind every corner was the same tiled floor, candles lit by a mystical green light and windows so large they put the countless classroom doors to shame. Every few minutes a crowd of students would pass by, disappearing behind another wall withing second. No one noticed her, which was rather odd considering she was the only female in an all-boys school, her purple dress and feminine curves were proof enough of that. "I guess this is the result of being a ghost, wandering the land of the living" She whispered hopelessly to herself. "You're invisible when you're me..."

The eighth turn that Eliza took brought her to a small cluster of peculiar students. Some donning ears and tails like those of wild beasts, while the other had odd features resembling Ortho's limps. Metallic and reflective. They were laughing at something, attentions enclosed within their small groups. A measly thought flew into Eliza's head, why not speak up? Raise your voice and ask where she could locate the headmaster of this complex establishment.

"Excuse me."

“....”

Silence

None of the boys turned to her, they just continued with there chatter. Eliza opened her mouth to speak once more when she -rather unwillingly- picked up stray words from their conversation.

"It's not fair!" A tall lanky one with striped ears and tail whined

"Yeah! How come that useless shut-in gets to get married to a cute girl !" the second one was even taller, with thick furry grey ears that reminded Eliza of a wolf.

"Look man I don't know what Idia has that makes him so damn lucky! He's a useless wimp..." A Bold statement made by the one with metallic features.

Eliza was sure they continued bashing Idia but the phantom pain of blood coursing through her ears droned them out. How dare such hooligans speak ill of her beloved husband! Her fingers flexed in a robotic-like movement, stretching open than closing once more. Around her tiny flame-like spirits began to materialize, cute and cheery with big eyes and smiling mouths...until they noticed the distress of their mistress. the tiny things took a look around, grasping the situation from the loud words of the boys as well as Eliza's grim expression. Slowly the little flames began to merge with one another. Fusing into a large ax with a burning end. The weapon floated down to her hand, positioning itself smugly between her ghostly digits.

Eliza's eyes locked with the backs of the boys, she didn't know how this would work, could the ax could even harm the living? It may just phase through them as if nothing had happened....or it may price through there flesh and bones, tearing them in two. Hosting the ax up over her shoulder with both hands and taking a shaky step forward, Eliza lunged towards the first boy. In a swift flick of her wrist, the blade of the ax was pushing through the Ignihyde student's back. Splitting ceaselessly at the skin and urging past muscles until it reached the creamy colored bones. Eliza didn't stop there, her arms still pushing forward trying to get the heavy ax to break those pesky osseins. He had to pay for what he said! No one was permitted to speak ill of her one true love! A satisfying crack filled the air followed by a choir of screams. Only when the ax had finally resurfaced on the other side, covered in plasma and the remnants of organs, did Eliza turned her attention to the other two students. There eyes where enormous staring at her in disgust and fear...and something else. Something that -although it revolted her to her very core- she wished Idia would look at her with that same look in his eyes. A look of want, a look of need, pure lust, yet the welcoming sort ONLY if it was coming from the person you adored so much.

The blue-haired ghost didn't move, her semi existent body felt overworked. Everything hurt! Or at least she thought what she was feeling was the ghost equivalent to human pain. "Why.." her voice glitched at every syllable, like a broken cassette player. The two boys didn't answer instead taking shall strides backward. "WHY DID YOU SAY SUCH AWFUL THINGS ABOUT HIM!" in a split second, anger over ran Eliza's boy once more, dragging her and the ax forward until the blade came in contact with one of the animal eared men's neck. Slicing it so it flung backward, crashing onto the ground with loud "thud" then rolling around in its own gore. The last man stand, the one with monochrome ears pushed his palms forward, a pathetic attempt of shielding himself from her wrath. "W-we..we d-d-did...didn't-t mean...mean any..offense...honest!" His voice creaked as tears gushed from the corners of his eyes. "You're...you're just so...so...pretty...beautiful even...and...and...Shroud well...we...well, he's a loser who w-w-wouldn't kno--" his words were left half-finished, as Eiza's ax severed through him diagonally.

Her heart was pounding much too fast, that it was beginning to make her feel sick. Her legs finally gave up, sending her crashing onto the blood coated floor. Her bare knees dug into the red liquidy substance, finding an odd comfort in the warm human ichor. Eliza didn't know what to do, or even where to go. If she went back to Idia like this he would surely use it against her, Ortho was too young to be introduced to such a carnage...and she didn't know anyone else! "I'm all so very doomed" she sobbed as transparent tears trailed down her eyes.

"Hey" A distant voice spoke up. "What's wrong with her?" another voice, this one more high pitch and raspy. Eliza tore her face from her hands looking up at a group of three strangers and a cat...no, not strangers, she recognized the orange and blacked haired boy. They both had tried to crash her wedding. But the other person was new, they had a gentle look in their eyes, a welcoming stare that the princess longed for. "Hey ghost bride," The orange-haired boy spoke up, "need some help with your mess?" Eliza nodded meekly. Her body still limp and voice still too frail to speak. The last person, the one that had unexpectedly piqued Eliza's interest extended a hand towards her. And with only a scrap of hesitation, Eliza gripped it.

"Come on, we'll help you out!"

💙 👻💙 👻💙 👻💙 👻💙 👻💙 👻💙 👻💙 👻💙 👻💙 👻💙 👻💙

Tags: @yandere-romanticaa @ghostiebabey @lovee-infected @mermaid-painter @firemelody4 also tagging @twstpasta and @delusional-obsessions cause I know they're huge Eliza fans.

#twisted wonderland#twisted wonderland x reader#twisted wonderland x you#twisted wonderland eliza#twisted wonderland idia shroud#twisted wonderland idia shroud x reader#twisted wonderland idia shroud x you#twisted wonderland eliza x reader#twisted wonderland eliza x you#idia shroud x eliza#idia shroud x reader#idia shroud x you#ghost x reader#yandere idia shroud x reader#ghost x you#yandere idia shroud#yandere idia shroud x you#yandere eliza x reader#yandere eliza x you#yandere ghost x reader#yandere ghost x you#yandere#yancore#yandere x reader#yandere x y/n#yandere x you#yandere hades x reader#yandere persephone#hades x persephone#yandere imagines

343 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

▶ The Doors - When the Music's Over ( I RE-POSTED THIS TERRIFIC ANALYSIS FROM " BenS/b-rod, 7moths ago"}}: "Ew, he wants to what?" Well first of all, you've got to understand where Morrison was coming from. A little background information is certainly required for the uninitiated. Jim wanted first and foremost to be a filmmaker and a dramatist (and poet) before he ever wanted to be in rock n roll. He went on to graduate from UCLA (unlike the deplorable Oliver Stone movie where a full ONE THIRD of the thing is FICTION - ie, never happened, like certain scenes, and the very crass way Kilmer portrayed him was ludicrous - but that's another topic). In the film department there, he learned many things about cinema and drama in general that he transposed into his music. He even had acting lessons according to Paul Ferrara. Anyway, I think the main work that influenced Jim on "The End" was Artaud's "Theatre & Its Double," which I reread recently and it made a lot more sense to me why Jim went in that theatrical direction. When I reread it, pieces fell into place that I'd never realized before. Artaud goes through his theories and in one instance, he even mentions "Oedipus Rex" itself by name (which, for those who don't know is an ancient Greek play that Freud psychologically postulated as universal, Oedipus for boys and Elektra for girls - deep in the unconscious). On a side note, Artaud also had a major influence on the Living Theatre, which Jim saw every show he could of, with their confrontational approach to theatre, which was right before Miami, and is what got Jim in trouble down there for allegedly exposing himself, with it fresh in his mind. Anyway, I believe its drama. Jim didn't get into personal confessional lyrics until LA Woman with things like "Hyacinth House" or "Cars Hiss By My Window." "The End" does start out about a break up with his girl prior to Pamela but then obviously goes in another direction when they would improvise to fill their slot at London Fog. But Artaud's work, I think, is key to understanding where Jim was coming from and the theatricality of some of his lyrics. And as Ray said about the Lizard King to Ben Fong-Torres - "That Lizard King thing - that's out of "Celebration Of The Lizard" and he's acting a part; its a theatre piece. Its a drama of which a guy is leading a small band of people...out into the desert and at the end of the whole piece he says "I am the Lizard King, I can do anything" and people are going "Oh, he's the Lizard King, he's the self-proclaimed Lizard King." You bastards, man! He's ACTING! ITS A ROLE, you know? Marlon Brando is not Stanley Kowalski, Jim Morrison is not the Lizard King, but they ground him down [for it]."Could the same be said for "The End?" You fuckin bet.Here's Jim speaking in late 1970 (also to Ben Fong-Torres) - "Are you still considering yourself the Lizard King?" "What I was trying to say with that, and that was years ago, and even then it was kind of ironic. I meant it ironically, and it wasn't meant to be - " and Pam cuts him off saying "That whole thing was done tongue-in-cheek" and Jim says, "Well, half tongue-in-cheek" and Pam continues, "and everybody thought it was like so serious." Jim: "Well, its an easy thing to pick up on." Its interesting to note that his production company with, I think, Paul Ferrara and Babe Hill, joking called themselves the Media Manipulators."Well, its an easy thing to pick up on" is the operative phrase - memorability, standing out, and this, I think, is key to understanding "The End" and other things. In the same interview with Fong-Torres, he also talks about how at newspapers there's someone who is there to write only the headlines of an article, that it has to be a catch phrase. Maybe its hard for literal-minded people to understand, but Jim says "THE killer" and then proceeds to take a face, an ancient drama mask that actors would wear on stage. He doesn't say "I" until he's set up the scene and in that role. "The key to throwing the audience into a magical trance is to know where in advance the pressure points must be affected...But theatre poetry has long become unaccustomed to this invaluable skill...To make language convey what it does not normally convey. That is to use it in a new exceptional and unusual way, to give it its full, physical shock potential...and restore their shattering power...The thought it aims at, the states of mind it attempts to create, the mystical discoveries it offers...It all seems like an exorcism to make our devils FLOW...strange signs, matching some dark prodigious reality we have repressed...ready to hurl itself into chaos in a kind of magical state where feelings have become so sensitive they are suitable for visitation by the mind...We must not ask ourselves whether it can define thought but whether it makes us think [and feel], and leads the mind to assume deeply effective attitudes...Just as in former times, the masses today are thirsting for mystery" (Artaud) (And there are more quotes equally as good in his work).I'm not saying he was consciously thinking of Artaud's theories when he went up onstage that night at the Whiskey, but it certainly came out of him then - the culmination of many things going on in the background of his consciousness and trying to push the envelope as an artist. As a fellow INFP explorer (mine and Jim's personality type), I think I can understand Jim more than most in that respect. Its "drama of the highest order" said Jack Holzman

1 note

·

View note

Text

MEDUSA

Medusa was one of the three Gorgons, daughters of Phorcys and Ceto, sisters of the Graeae, Echidna, and Ladon – all dreadful and fearsome beasts. A beautiful mortal, Medusa was the exception in the family, until she incurred the wrath of Athena, either due to her boastfulness or because of an ill-fated love affair with Poseidon. Transformed into a vicious monster with snakes for hair, she was killed by Perseus, who afterward used her still potent head as a weapon, before gifting it to Athena.

Family · Portrayal

Medusa – whose name probably comelos from the Ancient Greek word for “guardian” – was one of the three Gorgons, daughters of the sea gods Phorcys and Ceto, and sisters of the Graeae, Echidna, and Ladon. All of Medusa’s siblings were monsters by birth and, even though she was not, she had the misfortune of being turned into the most hideous of them all.

From then on, similarly to Euryale and Stheno, her older Gorgon sisters, Medusa was depicted with bronze hands and wings of gold. Poets claimed that she had a great boar-like tusk and tongue lolling between her fanged teeth. Writhing snakes were entwining her head in place of hair. Her face was so hideous and her gaze so piercing that the mere sight of her was sufficient to turn a man to stone.

Poseiddon and Perseus

It wasn’t always like that. Medusa – the only mortal among the Gorgon sisters – was also distinguished from them by the fact that she alone was born with a beautiful face. Ovid especially praises the glory of her hair, “most wonderful of all her charms.” The great sea god Poseidon seems to have shared this admiration, for once he couldn’t resist the temptation and impregnated Medusa in a temple of Athena. Enraged, the virgin goddess transformed Medusa’s enchanting hair into a coil of serpents, turning the youngest Gorgon into the monster we described above.

Soon after this, trying to get rid of Perseus, Polydectes, the king of Seriphos, sent the great hero on a quest which he believed must be his final one. “Fetch me the head of Medusa,” commanded Polydectes. With the help of Athena and Hermes, and after compelling the Graeae for Medusa’s whereabouts, Perseus finally reached the fabled land of the Gorgons, located either in the far west, beyond the outer Ocean, or in the midst of it, on the rocky island of Sarpedon. Medusa was asleep and Perseus, using the reflection in Athena’s bronze shield as a guide (so as to not look directly at the Gorgons and be turned into stone), managed to cut off her head with his sickle.

The Posthumous Fate of Medusa

Strangely enough, Medusa’s story doesn’t end with her death. In fact, one can argue that the most peculiar fragments of her biography are all posthumous.

Medusa’s Children · The Lament of the Gorgons

For Medusa was pregnant at the time of her death, and when Perseus severed her head, her two unborn children, Chrysaor and Pegasus, suddenly sprang from her neck. The Gorgons were awoken by the noise and did their best to avenge the death of her sister, but they could neither see nor catch Perseus, for he was wearing Hades’ Cap of Invisibility and Hermes’ winged sandals. So, they went back to their secluded abode to mourn Medusa. Pindar, a great Ancient Greek poet, says that upon hearing their gloomy lament, Athena was so touched that she modeled after it the mournful music of the double pipe, the aulos.

The Miraculous Head of Medusa

Now that Perseus had Medusa’s head in his bag, he went back to Seriphos. However, while flying over Libya, drops of Medusa’s blood fell to the ground and instantly turned into snakes; it is because of this that, to this day, Libya abounds with serpents. When Perseus arrived in Seriphos, he used Medusa’s head to turn Polydectes and the vicious islanders into stones; the island was well-known long after for its numerous rocks.

After this, Perseus gave Medusa’s head to his benefactor Athena, as a votive gift. The goddess set it on Zeus’ aegis (which she also carried) as the Gorgoneion. She also collected some of the remaining blood and gave most of it to Asclepius, who used the blood from Medusa’s left side to take people’s lives and the blood from her right side to raise people from the dead. The rest of Medusa’s blood – a vial containing two drops – Athena gave to her adopted son, Erichthonius; Euripides says that one of the drops was a cure-all, and the other one a deadly poison.

Always the protector of heroes, Athena put aside, in a bronze jar, a lock of Medusa’s hair for Heracles, who subsequently gave it to Cepheus’ daughter, Sterope, to use it to protect her hometown Tegea. Supposedly, even though it didn’t have the power of Medusa’s gaze, the lock could still cast terror into any enemy unfortunate enough to even accidentally behold it.

Sources

You can read a prose summary of Perseus’ quest for Medusa’s head in Apollodorus’ “Library.” For a poetic account, see the ending of the fourth book of Ovid’s “Metamorphoses.” Naturally, Medusa’s genealogy is described in full in Hesiod’s “Theogony.”

See Also: Perseus, Adventures of Perseus, Pegasus, Gorgons, Phorcys, Ket

#Medusa#Posiden#Athena#Gorgons#Mythology#Greek#Wicca#Witch#Pagan#gods#gdessess#Hades Persus#Pegasus#polydeuces#ceto#cetonia aurata#chrasor#wicca#eclectic wicca#wiccapedia#hellenic pagan#paganism#paganart#pagan witch#ecletic pagan#pagans of tumblr#snakes#perseus

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Wait For Me - Ch. 2

Title: Wait For Me Author: aliciameade Rating: M for dark themes Pairing: Beca/Chloe and Aubrey/Stacie Summary: This is a tale of a love that never dies. A tale about someone who tries.

This story is an adaptation of an adaptation of an ancient Greek legend. It's as alternate a universe as they come; there are no “Barden Bellas” here. Adapted story/lyrics by Anaïs Mitchell.

Also on AO3

~ ~

Chloe’s shoulder doesn’t ache anymore.

That’s a good thing given the fact that as soon as she signed her name she was handed a pickaxe and led to the depths of a mine.

However, she’s been swinging the pickaxe so long that she can barely lift it, yet somehow always manages to one more time.

She’s tried to leave more than once. She’s able to leave the mine only to find herself shoveling coal into a boiler alongside countless others. Everyone keeps their head down. Keeps to themselves. She has no friends here.

Aubrey said the wall kept them free but this isn’t freedom. It’s not the promised land. It’s true she doesn’t want for food. She doesn’t want for anything except freedom. She doesn’t feel anything except inescapable exhaustion. It’s not the type of life she thought she was agreeing to.

It’s not life at all.

~ ~

~ ~

“Chloe!”

She hasn’t heard her name spoken in so long she almost doesn’t recognize it. But she does recognize the voice. She whirls and there’s Beca, running toward her, somehow, in the glowing orange light of the factory. “Beca?!”

Beca’s barely winded when she slams into her, holding her fiercely. “I can’t believe I found you.”

“Beca, oh, my God.” She pulls Beca impossibly closer as if she could pull her inside her very self. “Is it really you?”

“It’s me. I promise.”

She chokes back a sob. “How did you get here? Did you come on the train?” Her eyes tear at what that means but at least they would be together.

“I walked. Come on, let’s go.” Beca pulls from their embrace only to seize her hand and tug.

“You walked? But the wall...how did you get through it? I’ve never seen a gap.”

“I sang my song and the stones let me in. Take my hand; I’m not leaving without you.”

Chloe actually digs in her heels. “Wait, you finished it?”

“No, but it was enough to get through, so I know I can sing us home again.”

“But you can’t, Beca.”

Beca spins; she’s frustrated but there’s relief present, too. “Yes, I can.”

“Since when are you this confident?” Beca almost seems like a different person; Chloe’s only known her as quiet and introspective and everything about her feels loud right now.

“I’m confident when I look at you.”

Chloe can’t help but smile even in this urgent, scary time. “And what do you see when you look at me?”

Beca seems to hesitate, then drops to her knees and clasps Chloe’s hand between hers. “I see my wife.”

“What are you doing?” Chloe’s heart, what little of it seems to remain, cracks.

“Marry me.”

“I...I can’t.”

“What? Why not?”

“Beca, I wanted us to be together. You kept promising things would change, that things would get better. That you could take care of me and I know, I know you tried and I know you wanted to, but sweetheart, you couldn’t. And now...now I can’t.”

There are tears in Beca’s eyes and Chloe has to stop from reaching out to brush them away. “I don’t understand.”

“I made a deal, Beca.”

“A deal?”

“With Aubrey. I belong to her now.”

“What?” Beca falls backward off her knees to sit on the ground. “That’s not true. Say it’s not true!”

“It is. I love you Beca, I do. But I’m hers.”

“No; I don’t believe it!”

~ ~

~ ~

Beca wants to cry and vomit and scream all at the same time but she isn’t offered the opportunity. With her next breath, she’s standing in an office. Or a bedroom?

And they’re not alone.

“I don’t think we’ve met.” It’s true; they’ve never met, but Beca knows exactly who Aubrey is. “But you don’t belong here. Everyone here is a law-abiding citizen and you’re trespassing.”

Beca sets her jaw and squares herself. Aubrey’s a literal queen. A goddess. And she’s no one. But still, she dares say, “I’m not leaving without Chloe.”

Aubrey laughs from where she sits on her desk. “And who the hell do you think you are? Do you even know who I am? She can’t leave, even if she wanted to. If you were from around here you’d understand that everything here is mine.”

“I don’t have to be from here to see that; it’s like you piss on everything you own like a dog.”

Aubrey’s head jerks a little as though she almost laughed. “Now, what do we do with you?” she muses thoughtfully.

“Aubrey, don’t.”

Beca hadn’t noticed her before, but now she does. It’s Stacie, from above. From better times.

“Don’t what? You know I can’t have people playing tourist here.”

“I’m not playing tourist!” Beca almost shouts it. “I came all this way just for Chloe. I let her slip away. I promised I would be there for her always. I promised her.”

“Why is that of any importance?”

“Aubrey!” It’s Stacie who shouts. “Damn you. How long have we been married?”

“Since the world began.”

“And I don’t care if your eye wanders—”

“She means nothing to me,” Aubrey answers quickly.

“But she means everything to this girl.”

“And?”

“Let her go.”

“Let her go?” Aubrey scoffs. “I can’t let her go. That’s not the way it works. I let them go and then what? Everyone will expect to be allowed to leave. Everyone will have an excuse.”

Beca felt Chloe’s hand tighten on hers and knew they were thinking the same thing: these two gods are fighting...over them.

“She is the only person who has ever found her way here past the wall uninvited. The only one. Can’t you see she’s special? Can’t you see how much she loves this girl?”

Aubrey frowns and turns her head toward Beca. “You think you can take care of this girl? You couldn’t even keep her fed. Look around you; why do you think she left?”

“All the riches in the world can’t buy love!” Stacie yelled, throwing a cup across the room, narrowly missing Aubrey’s head (she didn’t even flinch). “I didn’t fall in love with you because you could drown me in gold! There’s more to existence than this. Let them be happy!”

Aubrey does pause, though, as though Stacie hit a nerve. She pushes away from her desk and circles it to draw a piece of paper from a drawer as a pen appears in her hand. “I’ll tell you what, Beca.”

Beca holds her breath and squeezes Chloe’s hand harder; she can hear her breathing quickly, she’s so close.

“Since my wife apparently likes you,” she says with a dismissive wave as she writes, “and since I’m going to put you out of your misery anyway: you sang your way in here. I’ll give you one more song; make me feel something, anything, and I’ll think about it.”

Chloe’s voice whispers, “Beca…” and she can hear the worry in it. “You need to finish that song. Right now.”

“I will,” Beca says to her before kissing her, trying to draw strength from her but Chloe feels strangely empty. Beca hates that she knows why and it only motivates her further to find the end of her song. “Can you conjure up a guitar for me to use before you kill me? It wasn’t exactly an essential item for this trip.”

Aubrey doesn’t seem to do anything but nonetheless, the instrument appears in Beca’s hands. She slips the strap over her head and finds her opening chord, closes her eyes, and sings.

“Heavy and hard is the heart of the Queen Queen of iron, Queen of steel The heart of the queen loves everything Like the hammer loves the nail

But the heart of a woman is a simple one Small and soft, flesh and blood And all that it loves is a woman A woman is all that it loves

And Aubrey is Queen of the scythe and the sword She covers the world in the color of rust She scrapes the sky and scars the earth And she comes down heavy and hard on us

But even that hardest of hearts unhardened Suddenly, when she saw her there Stacie in her mother’s garden The sun on her shoulders, wind in her hair

The smell of the flowers she held in her hand And the pollen that fell from her fingertips And suddenly Aubrey was only a woman With a taste of nectar upon his lips, singing: La la la la la la la…”

“How do you know that melody?” Aubrey asks but Beca sings on. She’s not thinking about it now; she can hear the melody, the words in her head long before they leave her fingers and lips.

“And what has become of the heart of that girl Now that the girl is Queen? What has become of the heart of that girl Now that she has everything?

The more she has, the more she holds The greater the weight of the world on her shoulders See how she labors beneath that load Afraid to look up, and afraid to let go And she keeps her head low, and she keeps her back bending She’s grown so afraid that she'll lose what she owns But what she doesn't know is that what she's defending Is already gone

Where is the treasure inside your chest? Where is your pleasure? Where is your youth? Where is the girl with his heart on her sleeve? Who stands in the garden with nothing to lose, singing: La la la la la la la…”

“La la la la la la la,” Aubrey echoes and Beca feels the temperature in the room shift. The tiniest break in the oppressive heat as Stacie bursts into tears and runs, wrapping her arms around Aubrey to hold her tight as she sobs.

“You finished it,” Chloe says, voice hushed.

“How do you know that melody?” Aubrey asks again. She’s holding Stacie as though she hasn’t seen her wife in years.

“I’ve always known it. I just didn’t know why.”

“See?” Stacie says as she lifts her face from where it’s been pressed to Aubrey’s neck. “She’s special. Just let them go and sing to me.”

Aubrey sighs and hugs Stacie one more time before easing her back so she can have space at her desk. “I’ll allow you to leave together.”

Chloe gasps and Beca feels her push closer to her side.

“Under one condition.”

“What is it? I’ll do anything.”

“Chloe must walk behind you and you may not look back to see if she is following. Not until you are home.”

“Done,” Beca says as she rushes forward to grab the pen waiting for her in Aubrey’s hand to sign the contract.

“Then off you go. Same way you came.”

There’s no fanfare of departure; they find themselves on the other side of the wall in the dark, in the cold dead of everlasting night.

“Let’s go,” Beca says as she sets off, making sure to keep facing forward as she hears Chloe fall in line behind her. “Stay close, okay? Things get weird and scary out here.”

“I will; I promise.” Chloe’s voice sounds so nice; Beca has missed it so much. “Now I need to say something.”

“We got time. Let’s hear it.”

“You promised me so many things.”

“Chlo, I know. And I—”

“No, it’s okay. What I’m saying is that when you didn’t, I was dumb. I ran away instead of giving you a chance.”

Beca’s chest feels tight. “I know you wanted more than I could give you. But you promised you would stay with me. That we’d walk together forever. And I know I don’t have a ring and I can’t give you a feast and a feather bed like you want. But I will walk with you. Always.”

“I don’t need those things, baby. I just need to be able to eat when I’m hungry. Fire when I’m cold. You gave me those things and I wanted for more and it wasn’t until I had nothing that I realized I had everything. So don’t make me any more promises, okay?”

“I’ll make just one more: do you let me walk with you?”

“I do.” She can hear the gentle smile she knows Chloe’s wearing.

Beca smiles. “I do.” She wishes she could turn and kiss her new wife, but it will have to wait.

The walk becomes more difficult soon enough. They stop talking in favor of hiking over the sharp rocks that cut their hands and hurt their feet. Beca keeps an ear for the sound of Chloe scrabbling over the rocks behind her. It seems to get impossibly darker; she can’t see more than a few feet in front of her face and only due to a blood-red moon that hangs in the abyss above them.

When she makes it to the top, when the ground flattens, she listens for Chloe but hears nothing. “Still with me?”

“I’m here; hum your song for me so I can stay with you.”

Beca does, humming the story of the woman who so recently stole her love away from her, only to give her back. It was always a bittersweet song but now...now even more so.

The walk is easier and she’s able to set a quicker pace. She’s eager to get home, to start her life anew with Chloe whom she’ll never let out of her sight again. It’s not as dark now, almost like dawn, and a dense fog rolls in. She keeps her pace, though. She can sense the end is near. Can taste the steel of the railroad tracks just as she trips over one. It’s the homestretch now. She only needs to follow the tracks and they’ll be safe.

She can see their station rising out of the mist and she picks up speed until her feet hit the solid platform.

“We made it!” she says, spinning back to greet her excitedly just as she breaks through the fog. “We finally—”

“Beca!” Chloe says with a sharp gasp before she’s pulled back into darkness.

Gone.

~ ~

~ ~