#Testing Strips For Diabetes

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Armand Hammer - Total Recall

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Ill Communication within Armand Hammer's We Buy Diabetic Test Strips

[ on_ telephones_ paradox_ repetition_ thresholds_ accessibility_ &_ death_.]

############################################

Noises! Such a jangle of meaningless noises had never been heard by human ears. There were spluttering and bubbling, jerking and rasping, whistling and screaming…. The night was noisier than the day, and at the ghostly hour of midnight, for what strange reason no one knows, the babel was at its height.

—Herbert N. Casson, from The History of the Telephone (1910)

…a paranormal scrambling of phones…

—Aesop Rock, “All the Smartest People” (2021)

The children’s game of “telephone” depends on the fact that a message passed quietly from one ear to another to another will get distorted at some point along the line.

—Eula Biss, “Time and Distance Overcome” (2008)

The doors gaped on the gloom within. He paused on the threshold. “Do you know the code?” she asked.

—W. E. B. Du Bois, “The Comet” (1920)

A call to lighten up and eavesdrop on the eavesdrop to stop the reoccurrence.

—Sonic Sum, “Window Seat” (2000)

#.

We were prompted by postcards. We made calls to 1-877-ARM-N-HMR. We heard deceptive noises. We were duped by familiar sounds. We hung up. We dialed again, carefully this time. We heard abrasive percussive sounds. We heard crackly foreign languages processed through a bandpass filter. We heard this was a promotional campaign. Some of us, likely the loneliest or most curious of our lot, left messages after the tone, after the beep. We left messages for who knows who. A chosen few of those messages were transmitted over social media channels, eliciting further calls to the hotline. We were suckers, or we were onto something, or we were part of something.

#.

I used to have numbers memorized in my head. I used to call 1-800-COLLECT when I needed to be picked up from somewhere. The operator would say, Will you accept a collect call from…? And I would shout into the receiver at my mother, Pickmeup, pickmeup, pickmeup! I used to check the coin returns on every payphone I passed. Sometimes I’d even find change. I used to dial 555 followed by the last four digits listed on the payphone, hang up three times, and listen to the phone ring on its own, forever and ever and ever, amen. Payphones used to dot the city landscape. Now they don’t, but signs that offer to buy your home, your junk car, your diabetic test strips do.

#.

ALEXANDER RICHTER:

[woods] must have told me about the project some time last year—played me some early records and told me the idea for the album title. From there, we discussed ideas for documenting these signs in the streets in context to using them for album cover [and] packaging. I went out on two missions to take the photos. The first was in Brooklyn on Atlantic Ave. and some of the surrounding blocks, and the second was along Roosevelt Ave. in Queens. The goal was to put together an album package that hopefully conveyed the connection to the album name and additional photos that would support the strange guerrilla style marketing that can happen in the street.

#.

Armand Hammer has cracked the alchemical formulae for wheatpaste and solvent acrylic packaging tape. We’ve now seen them plastered in public squares from New York to London. There’s no telephone to heaven, word to Michelle Cliff, but ELUCID’s been trying to get to heaven yet refusing to sit down. “The rep grows bigger,” he said on “As the Crow Flies,” and look where it’s gotten him—on a billboard along Sunset Boulevard in Los Angeles. Graffiti writers stare skyward, tempted to bomb the heavens. You read right: an album with guerrilla communication at its core on a label that has purchased prime advertising space, thereby opening itself up to culture jamming jokesters.

How long will the billboards endure? Ghost signs in Brooklyn persist, denying erasure. Always a residue, a palimpsest of what was and continues to be. Faulkner guffawing in his grave. The past is never dead. It’s not even past, homie. Look at A. Richter’s lamppost photograph in the album art. The thoroughly papered pole—edges frayed and flickering—like tendons torn from bone. Those many messages never leave; they linger, never fully removed, never fully vanished. The FLAC files are lossless. We Buy Diabetic Test Strips is a litter-ary text.

How far will their message reach? ATTENTION, ATTENTION: CALLING ALL MOTHERFUCKERS…, Pink Siifu shouts at the start of “Trauma Mic,” the first single from We Buy Diabetic Test Strips, the first Armand Hammer album to be released on a label other than Backwoodz Studioz. Fat Possum, presumably, offers wide distribution and vast promotional resources. From El Segundo to Cape Town, Armand Hammer is available to listeners, but is the message welcomed? How many people will accept the collect call? Is the message being received as intended? Does it matter?

#. I GOT AN ANSWERING MACHINE THAT CAN TALK TO YOU

In the 1990s, woods’s “vision board was uncluttered” (“Don’t Lose Your Job”), but now he’s fending off brothers who drop “a project every month [and] got the nerve to ask if [he’s] peeped it.” He feels like Posdnuos on “Ring Ring Ring (Ha Ha Hey),” dealing with every Harry, Dick, and Tom with a demo in his palm. Armand Hammer’s popularity has been steadily growing over the past decade, exponentially of late, and like the children’s game of “telephone,” their message, the transmission, runs the risk of competing with noisy interference and distortion. They open themselves up to “misrepresenting the rhymes and all that,” as woods raps on “Empire BLVD.” “Imagine Jesus reading the Gospels,” he suggests, only to bring it back to his own experience: “SMH Rap Genius improbable readings.” More listeners—do the wrath of the math—means more misreadings. Armand Hammer’s ascent has culminated with coverage in the prestigious pages of places like The New York Times and The Washington Post. The comments section on the latter does what comments sections do. The majority of this “discourse” misreads Armand Hammer, rap music, and America. Commenter “observer25” claims to have listened to WBDTS. Their conclusion? “I tried—in vain���to hear talent, something pleasant to the ear…[but] I heard random noises and sounds devoid of any rhythm and accompanied by silly juvenile phrases.” That’s gloryhallastoopid, as ELUCID says, echoplexing Parliament. Such are the pitfalls of popularity. woods feels him on that. Forget being forthright; the line is fuzzy. On “Landlines,” the “voice-to-text [is] fucking up,” but woods “still sent it to capture the sentiment.” On “Woke Up and Asked Siri How I’m Gonna Die,” he describes how he “mumble[s] through the brain fog, / [With] tinnitus like a chainsaw.” ELUCID, on “The Flexible Unreliability of Time & Memory,” complains of a “headful of lightning, the signal in the noise.” Distortion wins the day.

How does it feel? ELUCID asks, again and again, on “When It Doesn’t Start With a Kiss,” and, frankly, we as the audience don’t know. We’re peanut gallery hecklers, at best. On May 17, 1966 in Manchester, England, a disgruntled fan screamed “JUDAS!” in between Bob Dylan’s raucous electric set. Dylan’s rejoinder, muttered into his lonely microphone from the dark stage in the cavernous hall, was “I don’t believe you. You’re a LIAR!” He turned to his band and said, Play fucking loud! They demolitioned into “Like A Rolling Stone,” whose chorus infamously asks, How does it feel…to be a complete unknown? On “Spellling,” ELUCID spoke of “Iscariots litter[ing] the valley,” prophesying what was to come.

Armand Hammer—billy woods and ELUCID—are now both known and unknown; they appear in press aplenty but remain enigmatic, still camo’ed. The comments section on the WaPo article had casual reader-ignoramuses assuming the duo is wealthy, living large off capitalist critiques. Fans know better. But Armand Hammer are unknown to listeners, too. Can we ever really know their intent, even on the rare occasions when they divulge something? woods will sometimes spill details and insights in interviews, but ELUCID is as buttoned-up as a straitjacket, not even printing his lyrics, as if that would dispel their magick. Which is interesting when we consider the images they present to the public, to the camera lens: woods strives for facelessness while ELUCID smiles like MIKE when he can, when he’s feeling all in the sun. With WBDTS, woods and ELUCID loiter at the threshold between known and unknown, nondescript citizens[1] and recognizable celebrities.

#. BEEN DOWN SO LONG IT LOOKS LIKE UP TO ME

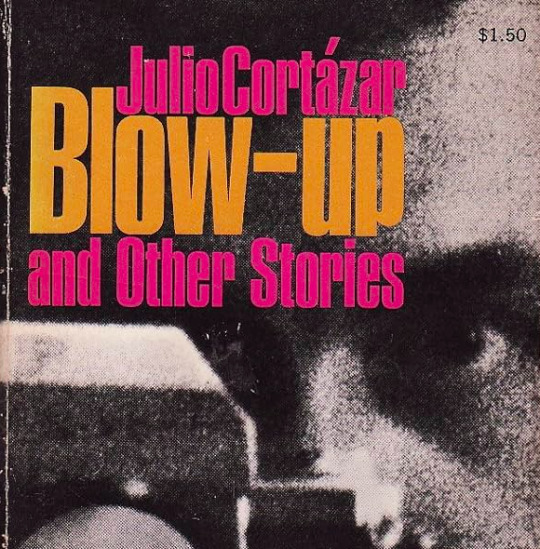

Mega Desu from the Secret House Against podcast noted Co Flow as “the new pop sensation” in the Bizarro World referenced on “Legends,” and surely Armand Hammer isn’t going to be receiving heavy Hot 97 rotation. They will, though, embrace De La Soul’s buhloone mindstate, insofar as they might blow up, but they won’t go pop, and—knowing these guys—“blow up” will mean vertiginous versifying that alludes to Julio Cortázar, Michelangelo Antonioni, and take-your-pick of historical leftist cadres that dabbled with incendiary devices. The ceiling is the roof for woods and ELUCID, and it seems well within their power and agency to tear da roof off this sucker, be it by Busta Rhymes or Parliament designs.

ELUCID credits and quotes Tricky verbatim from Pre-Millennium Tension (1996): “Everybody want to be naked and famous.” The sentiment rings out, seeing as how we’re always feeling a pre-millennium tension—early onset, late blooming. “Echoes and reflections,” in ELUCID’s words. As the rep grows bigger, the fans cop from Backwoodz and, like a habit-forming first hit, they become addicted. The songs on WBDTS induce dependency (“rather be co-dependents,” remember). Cavalier speaks to the chronic compulsion on “I Keep a Mirror in My Pocket”: “I once copped from woods—ain’t been the same since.” A “gateway drug” without the bad faith or scare tactics.

#.

Any upward trajectory Armand Hammer may experience appears to remain grounded by a firm grasp on reality. “Climb the mountain together, but the descent [is] riddled with crevasses,” woods raps on “The Key is Under the Mat,” shouting back to ELUCID who earlier announces them as “the only Blacks in the rock climb.” Decked out in harnesses and carabiners, they’re enlightened enough to recognize the paradoxes of their path, a knowledge that comes from having “been in a hole at the bottom” but attentively studying “pretty clouds.” Like The Snow Leopard (1978), Peter Mathiessen’s account of his trek across the Himalayas after his wife’s death from cancer, woods and ELUCID are searching, suddenly seeing that “form is emptiness and emptiness is form.” Have they reached New Agey nirvana? Maybe. If they have, they’ve gone to tell it on the mountain, over the hills and everywhere. Grand verbalizing and sermonizing from the mount.

It can be lonely on the mountaintop. Like MLK’s last speech, they speak words prophetic and perturbed: Well, I don’t know what will happen now…. We’ve got some difficult days ahead…longevity has its place…I’ve looked over, and I’ve seen the Promised Land…. I’m not worried about anything…. More accurate might be Baldwin’s description from “Stranger in the Village” (1953): “The landscape is absolutely forbidding, mountains towering on all four sides, ice and snow as far as the eye can reach.” Think Kiliii Yuyan’s photograph for the Terror Management album cover.

#.

William Woods to the white courtesy phone.

—“Kanun” (2013)

In her essay “Time and Distance Overcome,” Eula Biss gives a condensed history of the telephone, but—more specifically—telephone poles. She documents early reactions to the sudden appearance of poles lining the streets. Newspaper editorials described the poles as “an urban blight.” “The poles carried a wire for each telephone,” she writes, “sometimes hundreds of wires…. The sky was filled with wires.” She attributes this “War on Telephone Poles” to “that terribly American concern for private property and a reluctance to surrender it to a shared utility.” In light of this, we might read the excessive flyer and advertisement eyesores stapled to poles as symbolic resistance—a reclamation of ground ceded to government. But, Biss points out, there was also “a fierce sense of aesthetics” to consider, “an obsession with purity, a dislike for the way the poles and wires marred a landscape.” I can’t help but hear echoes of that Washington Post commenter dismissing Armand Hammer’s music as nothing more than “random noises and sounds devoid of any rhythm.” The commenter’s opinion bred, ostensibly, by ignorance and hatred.

#.

Six years ago, ELUCID began Armand Hammer’s “Microdose” with a caustic-ass quotable: “I was born in the year of this country’s last recorded lynching— / My question is: Who stopped recording?” In her essay, Biss includes a litany of lynchings perpetrated through the exploitation of telephone poles for that malevolent purpose:

In Pittsburg, Kansas, a black man’s throat was slit and his dead body was strung up on a telephone pole. Two black men were hanged from a telephone pole in Lewisburg, West Virginia…. In Greenville, Mississippi a black man accused of attacking a white telephone operator was hanged from a telephone pole…. A black man was hanged from a telephone pole in Belleville, Illinois, where a fire was set at the base of the pole and the man was cut down half-alive, covered in coal oil, and burned…

The telephone poles, Biss explains, were “convenient as gallows” due to their “tall and straight” structure, their “crossbar,” and fixed location in “public places.” It was only a “coincidence,” she says, that a pole might “resemble a crucifix.”

#. DUNN, I’LL HIT YOU RIGHT BACK, ’CAUSE THE STATIC IS THICK

In the introduction (the “User’s Manual”) of Avital Ronell’s[2] The Telephone Book: Technology, Schizophrenia, Electric Speech (1989), she writes:

Dealing with a logic and topos of the switchboard, it engages the destabilization of the addressee. Your mission, should you choose to accept it, is to learn how to read with your ears. In addition to listening for the telephone, you are being asked to tune your ears to noise frequencies, to anticoding, to the inflated reserves of random indeterminateness—in a word, you are expected to stay open to the static and interference that will occupy these lines.

“We shall constantly be interrupted by the static of internal explosions and syncopation,” Ronell continues, “—the historical beep tones disruptively crackling on a line of thought.” So on “Landlines,” ELUCID acclimates us with onomatopoeic omnipresence: “Leave a message at the beep-beep.” “Don’t play on my phone ’less you Badu,” woods warns, though if I put in a call to Tyrone, or André 3000, or Common, they might advise otherwise.[3] The telephone, Proust writes in The Guermantes Way (1920), is “a supernatural instrument before whose miracles we used to stand amazed, and which we now employ without giving it a thought.” On “I Keep a Mirror in My Pocket,” Cavalier “yell[s] in speakerphones while [he’s] walking brisk” as he DialsA’Freaq on his Cel U Lar Device, his “handheld obelisk.” The phone becomes something monolithic. Mesmerized by the mirror. But also desensitized to our devices—appendages, really. I put in a call to Walter Mosley, and he confirms that Jane Barbe or Ma Bell is the true “devil in the blue dress” that woods refers to on “Niggardly (Blocked Call).”

#. GET YOUR PHONE PHREAK ON

We got ya phone tapped—what you gon’ do? ’Cause, sooner or later, we’ll have your whole crew, All we need now is the right word or two…

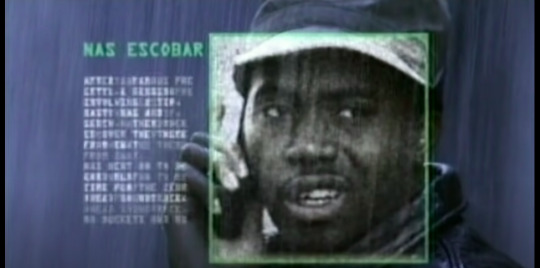

—The Firm, “Phone Tap” (1997)

Escobar tells Sosa at the end of “Phone Tap”: “Don’t even use the phone—just come to my crib.” But frequently that frequency eludes us—we can’t simply avail ourselves of that level of immediacy and intimacy. We are so often siloed, satellite states of our own making. Most of our messages come from the beyond, the before, and the hereafter. I hope it’s nothing but hoes in paradise, in different area codes.

We can call it the call-back. The return-of-the. ELUCID and woods are ceaselessly placing calls to their past selves—relentless as robocalls, tireless as telemarketers. ELUCID calls back to “Old Magic,” establishing a “double portion and protection.” You don’t work, you don’t eat calls back not only to “No Days Off,” but way back—to the Soviets, to Saint Paul. “I read the paper even though they tell me not to,” woods raps, and all three of these allusions to their own body of work appear on “The Flexible Unreliability of Time & Memory,” though it seems their sense of time & memory might be more intact than they think. Ten years of Armand Hammer, and woods reads the paper (if you go back and look) on the cover of Race Music, their 2013 debut.

On “Total Recall” [re-call], ELUCID calls back to woods on “Marlow” from Terror Management: “Earth getting warmer; we going the other…” Like a call to repent (as Cavalier says on “I Keep a Mirror in My Pocket”—a chorus which calls to a magic mirror we know from “Snow White,” courtesy of the Brothers Grimm), mourning our Anthropocene epoch—what a time we chose to be born.[4]

#.

CHILD ACTOR:

I made [“The Flexible Unreliability of Time & Memory” beat] very intuitively without any hard knowledge of where they might take it. I did add in some glitchy talking samples that I think [woods and ELUCID] both picked up on in their own ways. One either seems to say “when” or “where” depending how you hear it, which I imagine may have had something to do with the mystical title. I guess, now that I think about it, I definitely liked the way the “when” sample went with the unmoored timing of the beat and lent it an uncanny feeling, which I guess qualifies as some kind of message! I dropped in another talking sample (someone saying “...a lousy…”) that I altered, which ended up sort of sounding like they were saying “Allah.” I don’t think I noticed that much at the time and just thought of it as garbled language, but woods clearly heard it that way and now of course there’s no other way to hear it after what he did with it. It’s rare to be asked to specifically custom-make a beat for a particular artist; normally I just send packs upon request and I imagine that’s the norm for other producers too. But secondly, it was quite a challenge to have to make the beat from one specific sample source considering I can often go through multiple records before settling on just the right sample to make a beat from. On top of all that, since I was sampling this session with Shabaka [Hutchings] and Adi [Meyerson] that I had really good memories of, I had a desire in the back of my mind to make a very substantial use of the session so their playing could come through in some way despite the way I flipped it. That’s also why I included a snippet of the session as the outro. This particular session was a pure improvisation among the three of us and owes its character substantially to the bassline that Adi locked into a couple minutes into the original source recording. I was really laying out and trying to give Shabaka’s beautiful melodic playing space while fleshing out the harmonic possibilities implied in Adi’s bassline. Though they sent me stems, I elected to make the beat by sampling the full rough mix since, again, that’s the way I’d normally approach making a beat that I sample from a record. That also forces me to make entirely different decisions than what I’d do if I was working with each individual sample, plus again is a way to maintain the true ensemble feeling of the source.

#. EUPHORIA BOOMERANG SIDE-EFFECT

The more popular you get, the less you’re understood. Can’t it be all so simple? Basic comprehension skills fail, go fuzzy (I can feel it). Signals get crossed; a paradox is a crossed signal. What’s supposed to be communicated is killed before it can be; what’s not meant to be communicated is. woods might “think in cursive,” but he “spit[s] jagged fragments”—curvatures gone crooked—and, ultimately, “every word out [his] mouth drag[s] [his] people backwards,” as he says on “Niggardly (Blocked Call).” Progress becomes its antithesis, and ain’t that a bitch?

Words spoken are misheard or misinterpreted. I’ve seen music journalists self-censor the writing of “Niggardly (Blocked Call).” The text speaks, apparently. Its tongue splits and twists. Maybe I’m the one mistaken. In Philip Roth’s novel The Human Stain (2000), Coleman Silk loses his job as a college professor when he refers to two students who’ve yet to appear in his class as “spooks.” What seems to be an issue of absenteeism becomes a racism scandal when it’s revealed that the two truants are Black. Complicating matters further, Silk has spent the majority of his life passing as a white Jew, though he’s actually a Black, Howard University dropout from East Orange, New Jersey.

Our world is paradox; Armand Hammer load lines like cargo crates onto the Ship of Theseus. woods: “I walked out of Denny’s like it was Ruth’s Chris” (“Y’all Can’t Stand Right Here). ELUCID: “Fed till nothing’s left and feeding on myself” (“The Key is Under the Mat”). woods: “Every answer I gave in the form of a question” (“Landlines”). We live with contradictions. woods gives thought to “people [he] lost to COVID-19, but it ain’t do a thing to the fiends.” By invoking all that was—and, in some cases, remains—uncertain and unanswerable about the coronavirus, woods sings a post-pandemic[5] blues. We couldn’t find reliable stats on susceptibility, transmission, or infection. Skepticism had us Lysol-wiping groceries, rocking latex gloves, and chugging bleach. Where did public health end and propaganda begin? How to sort through data and disinformation when inundated by both?

Entertain the temptation to destroy everything. On “Don’t Lose Your Job,” woods dons a “bomb vest but nothing happened when [he] pressed the button,” which is only a slightly altered ending to Pastor Ernst Toller’s fate in Paul Shrader’s First Reformed (2017)[6]. ELUCID acknowledges the absurdity, side-steps the suicide solutions of woods and Camus, only to be left feeling like he’s gonna “buy life insurance and just….” The title says “Don’t Lose Your Job,” but Tongo Eisen-Martin’s poem “Wave at the People Walking Upside Down” says

you are going to want to lose that job before the revolution hit

Are you the one waving, or are you the person walking upside-down?

#.

Rappers tired—inertia the only thing keep ’em moving.

—“Aubergine” (2021)

K.I.M. turns to stasis. Repetition is the enemy of Armand Hammer. “The Flexible Unreliability of Time & Memory” introduces a galaxy of surrealistic surveillance state moments that repeat, repeat, repeat—as if we’re standing still, as if the screen froze. Passwords stay the same and the identity thieves grow savvier. ELUCID shuffles past “fake trees in the Apple Store,” brick-and-mortar built on an ethereal web address. “I feel a way about proving my identity to robots,” he says, and who doesn’t? Silicon Valley fuckboys gonna captcha bad one. I’ll click a checkbox for no man or machine. I authenticate my own experience. Refusal to “update another version” like ELUCID mentions on “Switchboard.”

When ELUCID says he “wore the same thing yesterday—all white; more dingy,” he admits to the residue of repetition. He’s also “sweating through silk,” tainting and staining the textile. Edges are frayed; no clear or clean lines.[7] That silk—that Bombyx mori, if we’re dropping the precisest science—shimmers prismatically from every fiber of his being, each angle refracting. Should I play it again? he asks, knowing the answer ahead of time. Embracing “many multiplicities,” ELUCID is “living every mystery.” ELUCID, as any head nadda would know, is indebted to Édouard Glissant who says “multiplicity comes from those somewhat secret, somewhat unknown places.”

Addicted, but not addled by, the pleasures of ad infinitum, ELUCID “would run it back again.” I would run it back again. I would run it back again…. He’s not fretful of going explosive. On “When It Doesn’t Start With a Kiss,” his big-bang [re]birth, that “new light: exploded back from the womb-pit, / New myths, new names,” is reinvention. Repetition such as this springs somethin’-somethin’ anew. Fuck the forceps; he’s gonna “scream [his] way out.”

He discovers himself “back in places, cycles, residual loops.” No unwitting cog-in-the-machine—ELUCID is cognizant. Knows his place/meant, to borrow a Baraka neologism. Folks. This here is the story of ELUCID as Ishmael Reed’s Loop Garoo Kid. A neohoodooist so bad [not bad meaning “bad” but bad meaning “good”] he made “a working posse of spells phone in sick.” That’s right—you read correct: spells…and phone. woods isn’t oblivious either. He got the memorandum that reads “hindsight before it happens” on “The Key is Under the Mat.” And on “Switchboard,” ELUCID employs a kind of tricolonic puzzle about his mental processes: “Forgetting; I remember; I forget again.”

CHILD ACTOR:

I understand “loop” doesn’t literally need to mean loop, but, to be clear, I didn’t loop anything. I made this [beat] the way I make pretty much all of my other beats, which is mainly playing the chopped-up samples live—not to a click track or grid—without going back and editing much. It was actually especially important to me to try to make this one like my other beats in some distinct ways since the sample source material and other specifics were so unusual. I was worried it would end up sounding like a different producer if I got carried away, and I always like to have some kind of identifiable sound to what I do.

On “Don’t Lose Your Job,” we watch as woods “break[s] up weed on one phone; FaceTime[s] on the other.” Moving beyond facile observations about multitasking, Henri Bergson writes of “other worlds…existing in the same place and the same time” like “twenty different broadcasting stations throw[ing] out simultaneously twenty different concerts which coexist without any of them intermingling its sounds with the music of another.” Now apply that same metaphor to telephones. On “FaceTime,” remember, woods saw the simultaneity of his personal experience within the chaotic and electric world around him: “I’m just waiting for my phone to ping, / I’m thinking about you when I’m supposed to be thinking about other things.” We accept the inertia of our doomscrolling into the state of a sedentary living moment, sadly.

#.

To escape rote existence—to unstick oneself from the time lag, drag, or stag[nancy]—you need to expose portals and cross through thresholds. woods is no stranger to the crossover. He’s playing “pick-up ball, half-court, four-on-four” on “The Flexible Unreliability of Time & Memory.” Crossover like Rafer Alston, Rod Strickland, God Shammgod, etc. Crosses the River Jordan to the Promised Land while Iverson sings that old Negro spiritual, Roll, Jordan’s ankles, roll. We must accept this: Armand Hammer has crossover appeal. Their frequencies cross over into other genres that they bend circuitously, curiously, with alligator clips, transistors, and toggle switches. Not limited to rivers (older than the flow of human blood in human veins), they cross the mainstream, potentially—insofar as a mainstream exists in our entropic and stochastic world. On WBDTS, Armand Hammer crossover from the afterlife to this reality and back, and often—a simultaneity of subway stops. Listen for the crosstalk, the noise. Feel for the “bad energy” woods swears he won’t give us on the chorus of “Niggardly (Blocked Call).” Take heed of the transference.

#.

CHILD ACTOR:

I had heard the first couple JPEGMafia beats for “Landlines” and “Woke Up and Asked Siri How I’m Gonna Die” (we were actually supposed to play along with those beats, and I had sort of prepared something to what became “Landlines,” but we ran out of time). I found them really thrilling and made a conscious effort to make some decisions that would make the track fit in with that sound without biting the style. That definitely inspired a lot of the sound design I did. To me, the sound design evokes strange chunky metal doors opening to other realities/paths or violently slamming shut. I was pretty pleased that it ended up coming right after those same two beats in the tracklist, especially since those guys are notoriously meticulous with tracklists. It felt like the best possible confirmation to me that I had accomplished the mission. After the fact, I noticed this [beat] has a lot of inadvertent similarities to “Charms”—same instrumentation of flute/keys/bass/hand percussion though presented entirely differently as well as a general mystical theme in the lyrics. “Charms” the light and “The Flexible Unreliability of Time & Memory” the shadow. Also both track 3!

#. TRANSBLUESENCY

Tryin’ to separate me from the blood is disrespect like you coming in my home and not wiping your feet on the rug.

—Big Gipp, “Cell Therapy” (1995)

How we go about crossing over matters. woods stands in the genkan as he mentions “house shoes on tatami floors,” and ELUCID doesn’t mince words when he evaluates how you welcome him: “Don’t invite me to your house, ask me to remove my shoes, and your floors ain’t clean” (“I Keep a Mirror in My Pocket”). He’s not a huckster at your door, he’s a Huxley adherent; he kicks in your Doors of Perception, wavin’ the Fourth Vision.

The threshold is a place/meant where police sketches are left half-drawn (Inshallah). The threshold is crowded with charlatans, grifters, and wolves in sheep’s clothing. The choice was—and is—yours: “Kevin Samuels or Dr. Umar,” though neither choice is appealing. A real Scylla or Charybdis dilemma. And Dres knows, like woods, that “Jimmy Baldwin[’s] not coming through that door.” Sense left a long time ago, leaving only non-.

Navigating through the threshold is easier said than done, and half-steppin’ won’t guarantee passage. On “Supermooned,” woods seeks help from a reluctant specter of a woman, but “she slipped away in the garden maze amidst the twists and turns.” The woman teases woods, leading him on, leading him into a more complex tangle: “She called for me with a laugh—from where, I couldn’t discern.” He’s been in situations like this before, like on “Stonefruit,” where the mystery woman hides “back behind bougainvillea.” She slipped away with a slipstream strangeness—unquestionably some syncretic moon deity making mischief.

#.

woods’ moon goddess “called for [him],” but it wasn’t sufficient enough to guide him through the threshold completely. Call me when you’re outside, as Steel Tipped Dove’s 2021 album title says, a reference to the means by which artists make buzzer-less entry into his apartment studio space. On “Y’all Can’t Stand Right Here,” Moneynicca literally calls out to Dove by name. The title “Y’all Can’t Stand Right Here” prods, too—woods shooing a crackhead from his stoop on “No Hard Feelings.” Moves that fiend who keeps a pipe with him down the block. Can’t be clogging up the entranceway. Not when you’re close, but not close enough—not through and through. The sidewalks are packed with “white women with pepper spray in they purse interpolating Beyoncé,” thinking they’re falling into line, but only failing forward, god-willing, into an illegal formation.

#.

The walls are thin, permeable. On “The Rent is Too Damn High,” ELUCID and woods heard and felt a “wet cough” come through. “I can hear my neighbors fucking,” woods complained, confessed. Kafka knew the struggle of porous apartment life and the mania it materializes. In the short piece “My Neighbor” (1931), the narrator laments the “woefully thin walls” of his office. In the competing office across the hall, one belonging to a certain “Harras,” a new tenant, an “active man,” appears to be mimicking his work habits. “Like the tail of a rat,” Kafka writes, Harras “has slipped in.” Worse, the narrator’s telephone is located on a wall he shares with the neighbor. As such, he has “given up mentioning the names of clients on the phone.” He begins to speak in convoluted tongue twisters, “danc[ing] around, the receiver to [his] ear, spurred on by anxiety, on [his] tip-toes,” and yet he still inadvertently divulges his business secrets. WBDTS is largely about defining who is allowed in and who is denied entry—and that is decided, in part, by questioning one’s motivation for listening in the first place. Harras, the narrator is convinced, is eavesdropping to acquire intel. “Harras doesn’t need a telephone,” the narrator realizes, “he uses mine.” Harras doesn’t have to cross any threshold; he gains access by virtue of how handsomely and conveniently sound carries. He listens in, exploiting his neighbor, not “even wait[ing] until the end of the conversation.” The narrator acquiesces: “[Harras] scurries through the city…and before I have hung up the receiver, he’s already working against me.” woods used to skulk and skeme similarly. He used to “watch through peepholes on the humble like [he had] points on the bundle.”

#.

I live a life of appetite and, yes, that’s right, I live a life of privilege in New York, Eating buttered toast in bed with cunty fingers on Sunday morning. Say that again? I have a rule— I never give to beggars in the street who hold their hands out.

—Frederick Seidel, “Widening Income Inequality” (2016)

That’s not a lot of money, fam—that’s a couple Gs.

—woods, “Touch & Agree” (2014)

woods, ever the cosmopolitan, might rock four-hundred dollar Japanese jeans and indulge in gourmet meals, but he still sips New York City tapwater out of a paper cup. He’s Frederick Seidel on a Ducati Superleggera V4, but he’s actually not. While another whiny Washington Post commenter speculates that ELUCID and woods “live the American dream with 4-inch wallets,” woods lets us know on “Landlines” that a “duffle bag hold[s] [his] pension.” With arbitrary definitions of success and even less secure sources of income, the struggle to accumulate wealth is all fits and starts, stunting and setbacks, repos and windfalls. It’s touch and go. Touch and agree? Sure, Armand Hammer has achieved a level of success in their 40s, but shit stays precarious, so they’ll forgo the “playboy rap.” If it’s Cheesecake Factory Fridays with your co-parent, you don’t gotta lie.

For every dollar the duo has gained access to, instability, contrarily, increases. “I still feel poor,” woods raps, and so, accordingly: “I put money in the floor, / I put money in the wall, / I put money towards getting the door reinforced.” This is nothing new. On “Touch & Agree,” he cowered behind “steel doors reinforced in a world full of sore losers and bad sports.” The murmuring Bigger Thomas that lives in his skull awakens:

I slept on the floor, thin blankets, coarse, Self-pity always stows away inside remorse, Gun-butt the teeth out of every gift horse.

woods has gone from “SpongeBob to Poseidon—[he’s] got the operation tightened.” These aren’t the hovel days of Hiding Places. These aren’t the dark times of “five dollar phone cards from the corner store.” From Johnny Nash to Jimmy Cliff, he can see clearly now. The overseas connection’s not so choppy. His Africall to Zimbabwe doesn’t have to compete with Death lurking like baseheads in the bodega. No haunting robot voice telling him how much money he’s got left on his account.

#.

You can’t wait for an invitation; sometimes, you need to impose. “I walk through doors,” ELUCID sang on “Stonefruit,” “—my name’s on no list.” We’re talkin’ access and inaccessibility. When he intones—on “The Gods Must Be Crazy”—your money’s no good here, our galaxy brains imagine a post-scarcity, Afro-anarcho utopia. Or maybe it’s just the phrase you hear uttered on the block when a community gets busy wishing away gentrifiers. The key is under the mat, but careful who you tell it to.

#.

It’s off the hook this year, Gettin’ mad money off the books this year.

—The Beatnuts, “Off the Books” (1997)

The central motif of the diabetic test strips signs is particularly rich. We can entertain them as communiqués, hidden messages wildstyled across inner cityscapes. Evidence of a shadow economy, tenebrous enough to make your blood glucose boil. Not since Martin Shkreli has there been such a meeting of hip-hop and the medical-industrial complex. Shkreli, the loathsome conman popularly known as “Pharma Bro,” charged patients $750 for a single Daraprim pill. Later, he won a Paddle8 auction with a $2 mil bid on Once Upon a Time in Shaolin. Culturally and ethically, humanity lost. Communication connects, but it also unavoidably fails, breaks down, and frustrates our sense of access and even reality. David Simon was “asked by law enforcement not to reveal certain vulnerabilities” in regard to police surveillance in his plotlines for The Wire. Simon complied, and the show continued to be lauded for its realism, the audience and the corner boys of Baltimore none the wiser.

#.

As I write these words, ELUCID steps to me and asks, Fuck you know? What the fuck you know? And I can’t ignore woods telling me, “Don’t try to add on.” They speak for themselves, and yet, here I type. On “Trauma Mic,” ELUCID tells it like this: “Neo-folk: trauma mic: echo chamber: deepfake: / Fake deep: talking wound: say it to my face, nigga!” He tells me that, and I—provoked—tell something back. The lines represent a flourish of mostly di- and trisyllabic metrical feet; anapests pummeling us into submission (“neo-FOLK”; “trauma MIC”; “talking WOUND”). The bars hinge on the rollicking good antimetabole of deepfake/fake deep. “Say it to my face” then begs the questions: Which [generative] face exactly? How does the facial recognition software sort through the twill of the mask? “Deep fake” sounds promising, a potential for something empowering. But it’s uncertainty all the way down—a mis- and dis- communication.

“Neo-folk” invokes “the blackest metal,” which ELUCID identified as on “Betamax.” “This a dead church,” he said, labeling his bodily temple, I presume. The Norwegian black metal faithful will recognize the “deathlike silence” of Euronymous’s record label—the deathlike silence of an ear-to-the-receiver hang-up. ELUCID, in appropriating the language of a Nazi-sympathetic muzakkk, excavates the Helvete cellar. He spirals on his square, forcing himself to burrow, burial-style, beneath the concrete basement foundation. ELUCID’s not “fake deep” like so many other MCs; ELUCID is devastatingly sonorous with delphic complexity. Equal parts arcane and A.R. Kane; altered states incorporating incorporeal feels—a Timbs-gaze or dubby gauze: his “echo chamber.”

One senses ELUCID writes these rhymes in runes, reckoning with esoteric sigils and Nazi insignias all at once: a soundclash. The message made manifest in DJ Haram’s pruh-duk-shun. Sonically, “Trauma Mic” is Steve Albini’s spinal column snapping. Pink Siifu wailing as if through an Interfax Harmonic Percolator. Check the Nietzsche neck-snap by way of Damon Young on “Don’t Lose Your Job”: What doesn’t kill you makes you blacker. (Armand Hammer fully realized and revealed as the actual Big Black.) Willie Green dangles the Sennheiser in front of the Orange amp and crushes the vocals to gravel. Filter through: like the “heavy metal speaker” in the Toyota Cressida that woods mentions on “The Gods Must Be Crazy.” ELUCID notes the underpinnings of all nations and undoes your revisionist fuck’ry: No slave, no world; no slave, no world.

WILLIE GREEN:

I think the balance between clear and unclear is essential! That kind of contrast is the basis of my technique. You need the murky to understand how clear other things are and vice versa. Same with clean/distorted, bright/dark etc. Manipulating the contrast between things leads your listeners to understanding without having to be too direct. That said, the anchor to that is always the vocal, especially with artists like this where the lyrics are already so dense. I have to give people a fighting chance to understand. [The practice of running the vocals through guitar amps] is as much about the process as the final result. I’ve got lots of distortion plugins and boxes, but sometimes an amp moving air in a room with a mic just feels different. And I can get close more easily with other stuff and no one would question, but I enjoy the process of it. As long as it’s still serving the record, I do some things just to entertain myself, too. It connects me to the music more than just “use this preset and crank songs out.”

Armand Hammer gives to us; we give back to them. Wrong and right don’t follow through; it’s the flow, the pass of the mic, the pass of the pen—the voice-to-text, if you will. Study these dialectics. A unity of opposites co-existing. Coaxial cables wherein forever the twain shall meet. Feel how your “fingers numb, tryna work the light.” Desensitized from gripping that trauma mic. woods equips us with a chainsaw (“Woke Up and Asked Siri How I’m Gonna Die”) and a bandsaw (“The Flexible Unreliability of Time & Memory”) to cut through the noise, the aux cord, the copper speaker wires. We cut through the brain fog—together. Rewiring your brain is a prerequisite. A Philip K. Dick-styled “tele-transmitter wired within your skull.”

There are, and always have been, microphones within the casing of your telephone, of course. That’s the trauma mic: a traumatized mic. A mic that receives everything; a mic that transmits all. Not simply the fiendish pleasures Rakim expounded years ago—microphone as lethal weapon, or as phallus, or as master of ceremony means—but an oath, a debt owed, a magisterial instrument built of slave labor electronics and barbarism.

When Alexander Graham Bell completed the first call from New York to San Francisco, Eula Biss notes, it required 14,000 miles of copper wire and 130,000 telephone poles. That’s a lot of gallows and rope, if we fixate on the figurative. You can see woods and ELUCID winding the scrap copper in the Henry and Tim Blake Nelson-directed “Trauma Mic” music video. Coils are connections, are conductivity. When “Jim,” the protagonist of W. E. B. Du Bois’s “The Comet” (much more on this story momentarily), returns to his place of employment—a bank—he finds it in ruins: “Great, dark coils of wire came up from the earth and down from the sun and entered this low lair of witchery.” ELUCID and woods are a twisted pair of the occultish double consciousness. I find it difficult not to think of Coil, the British post-industrial band. Surely, ELUCID and woods have determined to adopt a similar ethos as John Balance and Peter Christopherson as they worship the glitch on WBDTS. Coil’s “Who’ll Fall” contains a nightmarescape of telephone sonics and an answering machine message telling of a friend’s grisly suicide. The person leaving the message struggles to make sense of the death—it doesn’t compute. He’s reaching out: We don’t really…connect.

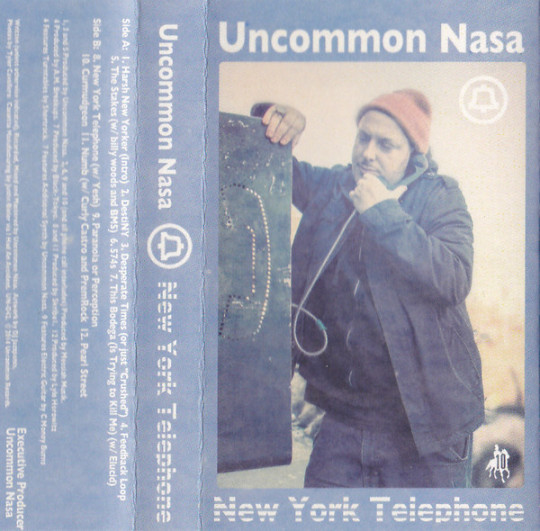

Armand Hammer want to unravel the coil as much as they want to gather it. As ELUCID puts it, “[WBDTS] is sprawling and fits into the idea of a secret network, [a] secret economy—so the songs have a winding kind of feel.” On “The Outernet” from 1997’s Overcast! EP, Slug explored a similar terrain. Let’s network, let’s all work, he rapped—one track of his vocals, appropriately, delivered with a whisper—so we can build the overall network. ELUCID and woods have been networking with seldom a hiatus for the better part of two decades. It was Uncommon Nasa’s annual Yule Prog event that initially brought ELUCID and woods together, and Nasa’s 2014 album New York Telephone featured them both. On the titular song, Nasa rhymes beside Yeshua, splicing wires together with the pre-millennial New York underground. “Hang up that payphone or you might get struck by lightning,” Nasa cautions, and Yesh’s verse is even more vigilant: “They’re saying it bakes our brains, radio waves, / And the way we’re all slaves to a monkey plan, I’ll be damned.” Paranoia or perception? (as another song on the album puts it)—but Messiah Muzik’s phone interludes on the album help pull us past panic and learn to love the drone. As the old New York Telephone TV ads said: We’re all connected…

And it’s all coming together. ¿Tu tienes WiFi? CONNECTIVITY. Reaching out to build what’s within. Whether it’s a call to Shabaka Hutchings, or Adi Meyerson, or Jane Boxall, or Abdul Hakim Bilal, or Hisham Bharoocha—the lines are open. “If it’s up to me, we’d mend the fences,” woods says—in Frostian fashion—on “Landlines.” He rather be codependents—he wants to compose, not oppose. Where ELUCID previously linked to Daniel Dumile as he preached a so-called “gospel of doom” on “Betamax” (another piece of antiquated tech, by the way), the connection transmits clearer on “Y’all Can’t Stand Right Here,” a beg-borrow-steal’d phrase from “Rhymes Like Dimes.” You know what it is: a call-and-response. On “NYNEX,” from Aethiopes, woods, ELUCID, and perennial collaborators Denmark Vessey and Quelle Chris, seemed to sing in chorus, as if affirming one another: Said he had a system…. The system, inarguably, is a system of communication.

In Blues People (1963), Baraka writes of the “long, long fantastically rhythmical sermons of the early Negro Baptist and Methodist preachers [who] sang with such passion and belief, as well as skill, that the congregation had to be moved.” The traditional African call-and-response song “shaped the form” of this worship. “The minister would begin slowly and softly, then build his sermon to an unbelievable frenzy with the staccato punctuation of his congregation’s answers.” He may as well be talking about ELUCID’s liturgical flow.

Thomas Edison once said (as Granville T. Woods turns over in his grave) that the telephone “annihilated time and space, and brought the human family in closer touch.” In light of that, we can understand the collaborative spirit of WBDTS. To quote ELUCID again: “This sort of reverse engineering of talented players who met for the first time in the studio jamming to pre-recorded beats before splintering off into new directions. Being in the room quietly watching four people fumble around each other’s sonic worlds before finally locking into a solid groove was a clear and obvious magical moment.”

#.

JANE BOXALL:

Communication is distance—the components of a drumkit (cymbals, snare drum, toms/kick) have roots on three continents. Percussion instruments point to places, communicating with the past and the mileage between points. Drums are a pretty durable form of long-distance communication. Sounds with deep, lost archives and antecedents. Communication is signaling. I’m currently finishing medic school, and the more I learn about the organ systems of the body (and their ways of failure), the more I appreciate and fear their interconnection. Drums and percussion are organ systems, too. Marimba is probably the guts of the operation, winding through its wooden octaves, buried under the instruments that sit at the surface of the sound. Vibraphone’s the skin swelling and softening; tank drum the elbows and knees—clanky, good for only a few maneuvers. Even if the collaborator is a beat, there can be a telepathic level of communication, reciprocity, a squaring of the individual powers. The low end of the marimba is wide as my wingspan, the bars paper-thin. The high end is hand-width targets, thick and stub-sounding. These extremes of register can communicate, counterpoint, obfuscate, or bolster one another. The marimba’s basso-profundo is fundament, the vibraphone’s skittering high register is firmament. Marimba, in particular, is stealthy—in most recorded contexts, it’s felt, not heard. I’ve recorded marimba on entire albums where you wouldn’t know it’s there unless you went looking—it’s the insulation in the walls. Marimba is only exposed for a moment on WBDTS, but it runs through much of the subsequent track. And yes, I’ve heard that direct communication is allegedly better than passive-aggression. But I still love how marimba can slither semi-anonymously around behind the bolder sounds, saying something via insinuation.

#.

How do you say you’re okay to an answering machine?

—The Replacements, “Answering Machine” (1984)

On “Niggardly (Blocked Call),” we find ELUCID gutted by a relationship in collapse. “What ever happened to not caring?” he asks. He frets about “30 missed calls” and a “blocked call” and a “voicemail that still hit[s]” where it hurts worst. Channels of communication seem to assert themselves, but he appears to want none, nil, nought. It “shouldn’t be this hard,” he says, “we’re not splitting atoms.” ELUCID retreats, plays Main Source’s Breaking Atoms in his earbuds as an escapist way-of-dealing, all while Looking at the Front Door. [T H R E S H O L D]. On “Irreversible, Devil” from King Vision Ultra’s SHOOK WORLD earlier this year, ELUCID [en]chanted: A beginning doesn’t need an ending, only a portal. In Christopher Harris’s 2000 film still/here, we become witnesses to the devastated landscape of postindustrial St. Louis. At one point, the camera settles on a gash-like opening—a portal—in a brick wall: the result of crumbling mortar. Throughout Harris’s film, a telephone rings hauntologically, chronically, diegetically—no one’s answering.

On the chorus, woods is “admittedly niggardly”—said with a smirk—as he declines to even communicate “bad energy” to his opps (harshing that vibe, bruv). He’s been influenced by ELUCID’s concurrent embrace and dismissal of the language of the occult, be it witchcraft, Crowley tracts, or Tarot card readings. woods, like Durkheim, dismisses charismatic magicians as conmen, cultivators of clientele. He alone might be responsible for casting off the customer base at Catland, gentrified Brooklyn’s “favorite little witch shop,” which closed at the end of this summer as scores of calls were pouring into the WBDTS hotline. woods eats knowing he’s “starving [his] enemies,” claiming to take “no pleasure” in it as he sips his bittersweet apéritif.[8] Forget cold-hearted, woods’s “heart pump[s] ketamine” as he k-holes down Flushing Avenue. He walks through the necropolis, hellucinating, having become a numb and distorted Perceptionist. (“Admittedly niggardly” is Black Dialogue scratched and warped as if by Fakts One).

woods keeps walking, but now he’s got purpose. He’s delivering a package, navigating to his destination. “All I had was an address in Maspeth,” he raps before conceding, “I know that’s not really the address.” The subtext, though, is that he does know the location. Once the drop is complete, he can return to the safety of his home, the domestic bliss we were allowed access to on “As the Crow Flies” from Maps. “I write when my baby’s asleep,” he reveals, “I sit in the room in the dark.” He meticulously rattles off every intimate detail:

I listen to him breathe, I walk him to school, then the park— hold they little hands when we cross the street. I think about my brothers that’s long gone and this was all they ever dreamed.[9]

Though he’s set adrift on memory bliss, woods compares what he’s got to what others don’t. He sees a fiend—an inexplicable survivor of COVID-19—who’s almost analogous to himself, a familiar if we want to be Macbethian about it. But woods is decidedly not the fiend. He revels, almost sadistically, in his good fortune: “I have to admit I enjoy watching you wander the wilderness, / You betrayed your brother, burnt every bridge, / When your end come, you’ll be alone.” woods looks upon his Cain-like brother, but it’s only a “peep”—a quick glance. He’ll sleep soundly, peacefully, “knowing these niggas is dead to [him].” When the phone rings in the night, he’ll “actually answer…just to drink your pain.”

#.

In Yellow Back Radio Broke-Down (1969), Ishmael Reed’s Field Marshall Theda character is startled as a page barges into his room: “Hey fuck-face Doompussy, whatever your name is.” Theda is aghast: “Why I never. Who gave you this address? I told them to never give out this number—why this is one of the few luxuries I have in this life…”

#.

ELUCID wears a “camouflage vest” to cross boundaries undetected on “The Gods Must Be Crazy,” to allow for liminal wanderings and trespasses. He utilizes his “third and [his] fourth eye” to “spin out in every which way,” omniscient. Wormhole wayfarer. For every threshold, for every portal, ELUCID has “been through” and “been inside.” His mind, as woods suggests, is “cracked open, seeing all the patterns.” We’re where “anything can happen if you tryna make it happen.” Wyclef’s carnival, maybe. Say what, say what, anything can happen when the history of civilization is an amphetamine-fueled warehouse rave with a fog machine thrown into overdrive. A carnivalesque, where under each tiny leaf this forest of dreams, the fruit which the future will harvest lies hidden. This entire album is a golden bough. (That’s me masquerading as Bakhtin, if you must know.) As if a projection on a screen in the Museum of Natural History (with your eyes glassy from the pain pills), woods drags us past “oracles and seers,” “madmen squatting in caves,” Bushmen “watch[ing] the world come off balance,” “hunter-gatherers watching black giants walk out the jungle,” and “aliens in spaceships.” We watch the ancestors watching the next civilization be born. We’re “invited to the christening,” just so long as we too understand our existence as “men pregnant with death.” Wyclef told you! When you got the skully to your face, anything can happen. “A face behind this mask behind this face,” ELUCID repeats as a round on “Switchboard,” as a gyre widening. He represents (represent, represent!) “so many people at the same time.” He puts the M-to-the-A-to-the-S-to-the-K ’pon his face just to make the next day. “The mask is related to transition, metamorphoses, [and] the violation of natural boundaries,” Bakhtin writes. “It contains the playful element of life; it is based on a peculiar interrelation of reality and image, characteristics of the most ancient rituals and spectacles.”

#.

On “Y’all Can’t Stand Right Here,” ELUCID chants What kinda world? as he revises Nas’s “If I Ruled the World (Imagine That)” into a more communistic vision, something more utopian. Where Nas offers “black diamonds and pearls” via Lauryn Hill, ELUCID proclaims “the mangoes were free.” While Nas speculates what it might be like “if coke was cooked without the garbage,” ELUCID celebrates the fact that the drugs in his paradise “was clean.” Nas wants to “turn trife life to lavish,” but ELUCID prefers to implement a world built on comfort and contentment rather than extravagance. He agrees that “the first shall be last,” but Matthew 20:16 probably didn’t foresee such excesses as Nas’s street dreams of “dime sexes and Benz stretches.” ELUCID calls for “no tax for the rest of natural Black life,” hoping to reduce the economic burden on a race of citizens who are disadvantaged at every turn by the tax code, property laws[10], right on down to neighborhood price gouging and payday loans. In ELUCID’s kind of world, people aren’t data points on a misery index. The mental toll is mitigated with free psychotherapy, which Nas also acknowledges, albeit briefly. It’s the “many years of depression [that] make [him] vision / The better living—type of place to raise kids in.” Nas’s vision, though, isn’t as incisive as ELUCID’s. ELUCID penetrates with what media studies scholar Jayna Brown calls “the force of black speculative vision.” Such a Visionary that you think he’d have Rhettmatic on the cuts.

Nas’s song—a song that mines the riches of Kurtis Blow’s “If I Ruled the World” (1985) and the Delfonics’ “Walk Right Up to the Sun” (1972)—is one of triumphant, if not naive, hope. Jayna Brown, though, doesn’t see utility in hope. “Hope yearns for a future,” she writes. “Instead, we dream in place, in situ, in medias res, in layers, in dimensional frequencies.” Count ELUCID as one such dreamer.

Though he uses the past tense in his verse, intimating that this utopian vision might already be behind us (which would be a tragedy of cosmic proportions), ELUCID is, perhaps, simply looking backward, as Edward Bellamy might say. Tense, as a grammatical structure of time, might be meaningless. ELUCID’s utopia is always-already happening. “Here and now, the past been fucking with me,” he raps on “Empire BLVD.” Jayna Brown feels the same way. Like Nina Simone, Brown is anti-postponement; she opposes the then and there.[11] “I argue for a spatial/temporal fold within the here and now,” she writes. Brown looks to “versions of utopia” that “radically disrupt the very idea of the future.” Or, in woods’ words on “Empire BLVD,” “retrofitted the futures.”

Brown asks that we “tune into an alter-frequency,” one suitable to a time and setting that is—to quote June Tyson—after the end of the world. Don’t you know that yet?

#.

STEEL TIPPED DOVE:

I engineered the vocal recording for a majority of woods’ parts, maybe two or three of ELUCID’s. I think the first one I did was “Landlines.” woods brought that beat through to my spot, recorded over it, and let me in on his plans with Chaz to make the album. [He] slowly but surely would come over with different beats and lay tracks down. Early on I heard of the studio recordings with the instrumentalists and thought that was such a dope idea, but by that point I was already submitting pre-made beats. Eventually woods let me know that not only was Chaz fucking with one of the beats I made but so was Junglepussy, and that had me hyped because she’s an incredible rapper. My beat was samples from Conexion’s “Hello My Friend.” It’s basically the first time I’ve had a sample cleared. Once that beat was chosen, I think woods wrote his part first. Then him and ELUCID came by my spot with Junglepussy. She laid down her part, and then Chaz did his at home or with Green maybe. Then to top it all off, eventually Pierce [Jordan] from Soul Glo got on the song and rounded out the end piece. Oh, and also, Fatboi Sharif has some vocal yells in the part between Junglepussy and ELUCID.

FATBOI SHARIF:

Me and ELUCID was in Dove’s studio and he just asked me to lay […] a backing vocal. He already had the idea of exactly how he wanted it to sound. I yelled “by the blood.”

MESSIAH MUSIK:

My contribution was pretty minimal having done the last 45-seconds on “Y’all Can’t Stand Right Here.” I wish I’d have thrown a few more things against the wall in retrospect. woods and ELUCID hit me with the files from the live sessions, and I made some attempts, but, more than anything, I [was] blown away by the creativity of the other producers and what they were able to bring out. But I was going through files and I think a lot of the stuff I made from the live recordings is better than I thought at the time, probably should’ve shared more just in case.

#. “THE END” IS A SIX-LETTER STORY

Then he started up the street,—looking, peering, telephoning, ringing alarms; silent, silent all. Was nobody—nobody—he dared not think the thought and hurried on.

—W. E. B. Du Bois, “The Comet”

Jim, the protagonist of Du Bois’s short story “The Comet,” is a lowly bank messenger. The bank president asks that he “go down into the lower vaults” to organize volumes of old records, a menial task reserved for a Black worker. Dutifully, Jim moves “down to the dark basement beneath; down into the blackness and silence beneath the lowest cavern…he grope[s] in the bowels of the earth, under the world.” As he crosses the threshold from above to below, it’s easy to construe Jim’s journey to the center of the earth as an allegory of underground survival. The subterranean bank vaults are a dingy refuge. As Jim approaches, “the whole black wall swung as on mighty hinges, and blackness yawned beyond.” Ironically, as he “step[s] into the fetid slime within,” he saves himself from the apocalyptic comet.

Emerging from the depths, Jim steps into a world that appears to be a world no more. Like KRS-One, we realize Jim “appear[s] everywhere and nowhere at once.” Everywhere, in the sense that thresholds abound. Nowhere, in the sense that he’s an invisible man. Jim is a stranger in a metropolitan village—as he’s always been—but the doors that were once closed to him by virtue of law are now obstructed by corpses: “In the great stone doorway a hundred men and women and children lay crushed and twisted and jammed, forced into the great, gaping doorway like refuse in a can.” Extricating himself from the dead, Jim finds himself, once again, “outside the world—‘nothing!’”

As he runs into a building on 72nd Street, following the “sharp cry” of someone “leaning wildly out an upper window,” Jim’s strange experience grows stranger as he encounters a white woman. He’s crossed another threshold: “At last the heavy door swung back. They stared a moment in silence. She had not noticed before that he was a Negro. He had not thought of her as white.” As their lives overlap, a Venn diagram of segregation and integration, Jim considers how this post-apocalyptic world diverges from the catastrophe he was living prior to the comet’s impact. “He would have been dirt beneath her silken feet,” he thinks. Like ELUCID said earlier, Jim is sweating through silk as the white woman “stared at him.” Her silken feet—diaphanous and thin, a mere membrane between above & below, white & black, before & after—evoke the ga[u]ze of their shared, surreal experience. The white woman “had been shut up in [her] darkroom developing pictures of the comet,” sparing her life, and that eerie location where colors transform and images appear out of nowhere through the application of ectoplasmic chemicals—hydroquinone, acetic acid, phenidone—feels more than appropriate. The flexible unreliability of time & memory, indeed.

Together, Jim and the white woman venture out into the earth-grave. “In and out among the dead they slipped and quivered,” Du Bois writes, and with such slipstream strangeness, the sky might as well be styling a supermoon.

#.

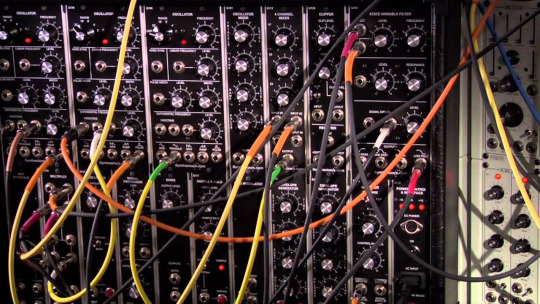

The production on WBDTS emits a “weird radiance that suffuse[s] the darkening world and [makes] almost a minor music,” to return to Du Bois once more. The cadre of accomplished sonic engineers, led by the spectral efforts of JPEGMafia, create an organized noize like an infinite TR-808 clang-a-langing, shaking dungeon walls. I’m left feeling doped up, woozy and brain-numb on narkidrine, the drug used during Quail’s procedure. Willie Green plugs and patches like Johnny Greenwood on the modular synth circa 2000—filenames like Kid A, Kid B, Kid C, etc. and an array of amnesiacs—configuring cyborg brain-stems and plant stems in a merciless hybrid of technology and ecology. Voices “echoed and re-echoed weirdly,” like Jim’s shouts within the bank vaults.

#.

AUGUST FANON:

There is a kind of duality that comes with intently trying to create a certain mood or feeling as a sample-based hip-hop producer in that you are constantly at the mercy of the sample (for better, or for worse). Of course once you learn records, hone in on your sound(s), and sharpen your ear, you can begin to craft beats with a certain mood more readily. I think more aptly I search out for different moods and feelings with intent, but at the same time I’m mindful of staying open to be inspired by a wide sonic range, if for nothing else than the records, mp3s, video, etc. I’m going through will vary wildly from day to day. I'm constantly sending woods and ELUCID beats with the intent that they will make a song out of it, whether for a specific album in mind or not. Over the years, as various projects of theirs individually or as a group have come up, they might prompt me (email/text) like “August, I’m working on a new solo album, it’s called XYZ.” So I then know that whatever I’m sending over might end up on the record. But since 2017 I’ve been sending them music non-stop. At first, I used to highly curate what I sent over. Then I remember for a spell over the pandemic I was just sending them everything coming out of my machine. But I’d say the last two years I’ve been back to just sending woods and ELUCID very specific beats. They never specify what they're looking for. I think I saw a tweet from ELUCID one time before I Told Bessie came out and he was saying something about how his next album was going to be “loud.” So in my head I was like, “Okay! LOUD. Boom.” But really, in my head I have a clear conception of what woods, ELUCID, or Armand Hammer sound like as a group and what I can do as a producer to help bring that out.

#.

MESSIAH MUSIK:

I don’t think I typically approach the creative process with an intent to evoke a particular emotion, but a lot of my beats are melancholic. Sometimes I will challenge myself to do things more uptempo or aggressive sounding. I know that my best ones are very emotive whether there was intention behind that or not. As far as communication, there is a lot of trust there. [Armand Hammer and I] have been working long enough that I can’t help but hear their voices in most of what I create. I have like 200 potential Armand Hammer beats on my hard drive ready to go at all times and I’m not shy to send them unsolicited.

#. PUSH BUTTON OBJECTS

As a Black man, ELUCID—like Fanon in Black Skin, White Masks (1967)—announces himself as in “total fusion with the world.” Total. Furthermore, his Blackness is not a curse but a result of the fact his “skin has been able to capture all the cosmic effluvia.” In Black Utopias: Speculative Life and the Music of Other Worlds (2021), Jayna Brown explains that Sun Ra offers an “alternative ontology,” and ELUCID has inherited the schematics. On “Total Recall,” ELUCID serenades: If you push that button, yo’ ass gotta go. He lifts-off from terra firma by lifting the line from Sun Ra’s “Nuclear War” (1984). ELUCID arkestrates his own exodus. He presses all the right buttons, but he walks the “left-hand path, / Rocking haint block blue.” ELUCID distinguishes himself from Aleister Crowley, though. He’s more of a celestial Sun Ra descendent than a dour Crowley acolyte. More of a golden disk than a Golden Dawn. More sequined purple stars on a lamé-evoking fabric than a leopard pelt.[12] Buttons are constantly pressed, jammed, or smashed on WBDTS. Pressed buttons don’t always achieve desired results, though.

#.

“Giz wetwa wum-wum wamp,” the phone mumbled.

Total Recall, the Paul Verhoeven sci-fi film from 1990, is based on the Philip K. Dick short story, “We Can Remember It For You Wholesale” (which has a clear We Buy Diabetic Test Strips ring to it). It’s a story about convincing yourself something happened even if it didn’t, or did. Douglas Quail wants to visit Mars. He approaches “REKAL, INCORPORATED” and “walk[s] through the dazzling polychromatic shimmer of the doorway.” He tells the receptionist he’s there “to see about a Rekal course.” She corrects his pronunciation: “Not ‘rekal’ but recall.”[13] McClane, the senior Rekal doctor, accepts Quail’s money and “press[es] a button on his desk.” McClane and company proceed to program an artificial memory—an “extra-factual memory”—on Quail’s behalf. Rekal, Inc provides Quail with “[o]dd bits which made no intrinsic sense” but could be “woven into the warp and woof of [his] imaginary trip” to Mars, including a “wire tapping coil.” Forget shuffling, the mortal and copper coil keeps coiling. “We Can Remember It For You Wholesale” gets close to what Mark Twain explored in “Mental Telegraphy” (1891), namely, the “phrenophone.” Twain’s mind-phone wasn’t intended to connect individuals to experiences they desired through manufactured memory but rather to establish the “rapport between two minds.” Twain believed “the telegraph and telephone [were] going to become too slow and wordy for our needs.” He saw the limits of telecommunications and speculated where we might move next—“a finer and subtler form of electricity,” the type of galvanic musical breakthroughs the WBDTS players experienced in their sessions.

#.

KENNY SEGAL:

Since WBDTS was being made as we were finishing up Maps, I was actually talking to woods almost every day at the time. [woods and ELUCID] gave me one of the live sessions and said to sample that. I made three beats with it, two of which appear on “Total Recall.” They chose the main beat to write a song too, but then I was like, “This [other beat] sounds dope as an intro.” I definitely try to communicate a vibe or emotion with a beat. Sometimes it’s very intentional, but other times it’s totally intuitive. Depends on my mindstate at the time, I guess.

#. TELEPHONOPHOBIA

Respond as you would to the telephone, for the call of the telephone is incessant and unremitting. When you hang up, it does not disappear but goes into remission.

—Ronell’s “User’s Manual”

Jim and Julia (the white woman) run around the city looking for signs of life. Jim suggests they try the central telephone exchange. Desperation overcomes Julia: “[She] leaped to the door and tore at it, with bleeding fingers, until it swung wide.” She settles at the apparatus before her in all its erotic grandeur:

The grim switchboard flashed its metallic face in cryptic, sphinxlike immobility. She seated herself on a stool and donned the bright earpiece. She looked at the mouthpiece. She had never looked at one so closely before. It was wide and black, pimpled with usage; inert; dead; almost sarcastic in its unfeeling curves.

It’s difficult not to view the switchboard as some kind of miscegenation machine, what with its personified qualities (the mouthpiece, metallic face, pimpled) and death mask visage.

Julia calls out hello in “low tones”: “She was calling to the world. The world must answer. Would the world answer?” She gets no response. “At indicated times,” Ronell writes, “schizophrenia lights up, jamming the switchboard, fracturing a latent semantics with multiple calls. You will become sensitive to the switching on and off of interjected voices.” For Jim and Julia, though, only their voices are heard, echoing back. “What was that whirring?” Julia asks. “Surely—no—was it the click of a receiver?”:

She bent close, she moved the pegs in the holes, and called and called, until her voice rose almost to a shriek, and her heart hammered. It was as if she had heard the last flicker of creation, and the evil was silence. Her voice dropped to a sob. She sat stupidly staring into the black and sarcastic mouthpiece, and the thought came again. Hope lay dead within her.

No one responds. Their message goes unreceived. The phone keeps on ringing. Death, the leveler!, Jim mutters. And the revealer, Julia whispers.

#.

It’s strange to be calling yourself.

—Betty Elms, Mulholland Drive (2001)

The switchboard should usher in hope for communication, for connectivity—but it doesn’t. For Jim and Julia, the switchboard proves a terminus, as it does for woods on “Switchboard.” “I can’t see it yet,” he says, opacity wherever his eyes settle, “but something’s coming.” wøods is full of fear and trembling, his stomach in dredknotz. Seeking comfort, he “slept buried in her shoulder blades [with] one hand on her stomach.” Buried keeps us on the other side of those cemetery gates but contrasts with the pregnancy implied by resting his “hand on her stomach.” woods makes mention of men “pregnant with death” on “The Gods Must Be Crazy,” and the paradoxical phrase works perfect for someone feeling their mortality tested postpartum. I watch him grow, wondering how long I got to live.

The threshold between drowsy sleep and stirring to wake seems to be where more than a few woods verses writhe and wiggle of late. On “Switchboard,” he “wake[s] running” with a “scream wedged in [his] windpipe.” Let him clear his throat as he meanders somewhere between Oedipal arousal and he Ed Lover dance in GIF form, endlessly looping to DJ Mark the 45 King’s “The 900 Number.” His mind’s not right. He “fell asleep trying to write and woke to the beat bludgeoned.” Violence in the sheets—shoulder blades, bludgeoned beats—tossing and turning in the graveyard grass. He feels the noise of the beat “in [his] teeth like electric current circuits circling”—the harsh c’s, r’s, and t’s hurting, grating on the nerves repeatedly, seeing as how circ- means “around,” forming a “ring”: ring, ring ring (ha ha hey). As such, woods brings it back around with “circling buzzards,” which rasp like buzzers—a network crash, an interference—as they plunge beak and talons into carcasses. It’s awful, offal.

woods looks at his phone and sees “missed calls from [his] own number”—we’ve slipped again. Sleeping woods smothers his face in a surrealistic pillow and embarks on an embryonic journey. Logic and proportion have fallen sloppy dead. The men on the chessboard on the cover of Liquid Swords get up and tell him where to go: “ a long hallway” and into “the room where you identify your mother.” woods shifts to the second-person now, because there is a second person: you. We’re with him in the dream, the nightmare, the morgue with the mother-corpse. You dispel her naked and expired image by supplanting it with your partner; you “go back home to your lover.” Hysterical in the truest sense—a womb-suffering (maybe this is what ELUCID meant by womb-pit)—ranting and repeating: How many times can you tell her that you love her? Questions don’t have answers. “Why the cellar door open when it wasn’t?” Well, nothing’s happening as it should. Thresholds open and close at random. Gusts of wind and ghosts. Dog at the front door barking at the air. The phonaesthetic pleasures of cellar door don’t sooth but scare. It’s probably a trap.

woods returns to nature to find peace. He “rake[s] leaves in the evening [and] smoke[s] a little weed in the back of the trees where they can’t see in.” They being whoever has infected his brain with devils. He obstructs their vision, but he’s seeing his own “breath leaving.” His “fingers freezing” in this cold spot. If only he had a ululometer![14] woods tries to be practical, sensical, attributing the temperature to climate change (I swear there used to be different seasons), but then he hears a chuckling voice say, You’re pretending to be grieving. The stability and serenity he seeks outside is disrupted just as it was on “Landlines.” There he fantasized of buying a home where he could “sit on the stoop” and listen to the “night breeze catch the trees.” Struggling to articulate it, “feeling some type of way,” he envisioned his “family under one roof” but heads back inside when he “hear[s] ’em start to shoot.” Tragedy’s never far off.

#. YOU GOTS TO CHILL

From a timeworn copy of Death Rituals and DIY Burials, a zine cut-and-pasted together by one “India” in July 2000, I know of “The Wheel of Death,” an inked image coupled with a quotation from Chuang-tzu: Birth is not a beginning; death is not an end. In Toni Morrison’s foreward to The Harlem Book of the Dead, a collection of funeral portraits by renowned Harlem Renaissance photographer James Van Der Zee, we learn that funeral rituals in early 20th-century Harlem were “parallel[ed] with those of the ancient necropolis of Egypt. They are in the continuum of those on the Nile of four thousand years ago.” The gods of today (jeez, they must be crazy), Morrison explains, “have replaced Osiris” (the style wild bastardized). She continues:

Death is the moment called quittin’ time, when we freeze in place like tomb figures or ancient wall paintings or photographs on a mantelpiece in Harlem. Family and friends witness the moment when the preacher sings out the life of the deceased, hoping to distract Satan or Anubis, with his great scale, from weighing the bad deeds against the goods.

“Laid a feather on a scale and ripped my heart out—weigh it up,” ELUCID spits on “Niggardly (Blocked Call)”. woods’ “Switchboard” verse is as disquieting as these Van Der Zee funeral portraits. Ectoplasmic visions aren’t a prerequisite, though; we can get the chills from a disembodied voice. woods is chillin’; Chaz is chillin’—what more can I say?

#. STONE TAPE THEORY

...telepathy, and even clairvoyance, are not inconceivable in this day of the wireless telephone, the proved existence of those mysterious rapid vibrations of the ether of which, as yet, we know tantalizingly little…

—Fremont Rider, Are the Dead Alive? (1909)

The quartz crystals in your iPhone attract ghastly presences, so of course woods was ready on “FaceTime”: “My evil eye ward off hex, though—FaceTime declined.” Listening to WBDTS (and I do assume you’re listening closely) is, in large part, like listening to EVP (electronic voice phenomena). As amateur paranormal investigators, we lend ears to any unorthodox frequency or outré fragment—glitches in the matrix. On “The Flexible Unreliability of Time & Memory,” ELUCID calls back to “Old Magic”[15] to activate a “double portion of protection”—a Blackness guarded by Pan-Africanist parades and black-mirrored screens encased in OtterBoxes. Diasporic problems and dial-toned. What doesn’t kill you makes you Blacker.

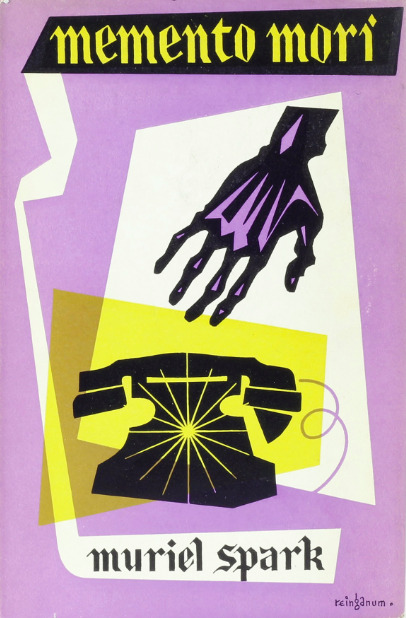

“Woke Up and Asked Siri How I’m Gonna Die” is a system update for Muriel Spark’s Memento Mori (1959). “One can’t be cut off perpetually,” Dame Lettie Colston says in Spark’s novel. “One must be on the phone. But I confess, I’m feeling the strain…. I never know if one is going to hear that distressing sentence.” The sentence that’s communicated to Dame Lettie through the receiver? Remember you must die. The message is delivered by a sort of voice of God—not so much a telephone (though the timbre of God’s voice does seem to travel from a great distance) as a theo-phone.

We normalize phone usage until our technology turns on us. A telephone rings and we used to come running. Before the advent of caller ID, we had no idea whose voice would be on the other end. Techno-spiritualism would have us believe voices from the dead screech and squeal through. Fallen copper wires drape over tombstones and our cobwebbed ears hear them sizzle. woods’ verse on “Woke Up and Asked Siri How I’m Gonna Die” feels mediumistic—a knack for channeling staticky transmissions, learned from ELUCID. He links “fresh wounds and old scars” and works a graveyard shift.

#.