#Temple Emanu-El

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Mayor LaGuardia stands with other mourners in front of Temple Emanu-El before the funeral of George Gershwin, July 15, 1937. Services were held simultaneously in Los Angeles, where Gershwin died, and New York. He died following surgery for a brain tumor on July 11. He was 38 years old.

Photo: Bettmann Archive/Getty Images

#vintage New York#1930s#George Gershwin#Fiorello LaGuardia#Gershwin funeral#July 15#15 July#composers#Temple Emanu-El

57 notes

·

View notes

Text

Deco Doings - April, 2024

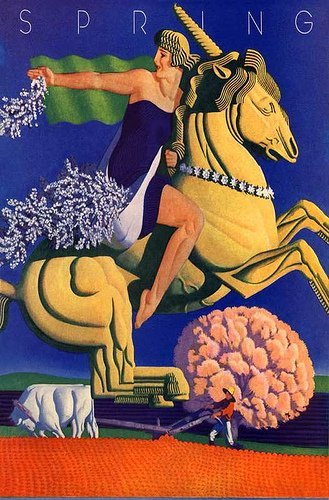

Spring by William Welsh, 1930. Image from Pinterest. Here are some wonderful Art Deco events to enjoy this April. Bard Graduate Center Sonia Delauney: Living Art (In Person Exhibit) February 23, 2024 – July 7, 2024, 18 West 86th Street, New York, NY Center Hours: Tuesday: 11:00 AM – 5:00 PM; Wednesday: 11:00 AM – 8:00 PM; Thursday – Sunday: 11:00 AM – 5:00 PM Box, 1913. Oil on wood. 20…

View On WordPress

#1933-1934 Century of Progress#42nd Street#Art Deco Preservation Ball#Art Deco Society of California#Art Deco Society of Los Angeles#Art Deco Society of New York#Astaire & Rogers#Cecil Beaton#Century of Progress Homes#Chicago Art Deco Society#Cocktails in Historic Places#Detroit Area Art Deco Society#New York Adventure Club#Temple Emanu-el#The Grasshopper

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

World Religion Day

World Religion Day is celebrated on the third Sunday in January every year, and is a reminder of the need for harmony and understanding between religions and faith systems. On this day, communities of different faiths have the opportunity to get together and listen to each other, as well as celebrate the differences and commonalities that the delicate intermingling of culture and religion brings. There are approximately 4,200 religions around the world. While many people live their lives without religion, faith in a higher being or power works for the majority of people. Whatever the reasons, we are all for the idea of people being unified despite differences, and celebrating them.

History of World Religion Day

The first official observance of World Religion Day (as it is known today), was in 1950, but the concept began a few years prior to that. In Portland, Maine, the National Spiritual Assembly of the Bahá’í Faith hosted a talk in Eastland Park Hotel in October 1947, culminating in the decision to observe an annual event, then known as World Peace Through World Religion. By 1949, the event began to be observed in other parts of the U.S. and grew more popular. By 1950, it came to be known as World Religion Day. On this day, at various different locations, many authors, educators, and philosophers are invited to speak on world religions and the importance of establishing and maintaining harmony between them. It’s a great forum for learning more about other religions and cultures too, and a chance to intermingle socially with people of different faiths and worldviews.

Since this concept was the brainchild of people from the Bahá’í Faith, it is worth exploring what this faith is and tracing its historical roots. As a religion, Bahá’í first emerged in Persia (modern-day Iran), in the 1800s. There are three core principles of this faith — unity of God, unity of religion, and unity of all mankind. It is a monotheistic faith, believing in a single god, and that the spiritual aspects of all religions in this world stem from this single god. Another central tenet is the belief in the innate equality of all human beings. Thus, all humans have the same rights and responsibilities. If you look at it, the Bahá’í Faith is an all-encompassing one that recognizes the commonalities between all religions, so Baháʼí believes that all faiths have common spiritual goals too, especially since religions are ever-evolving.

World Religion Day timeline

1800s The Baha`i Faith is Established

In Persia, around 1844, the Bahá'í Faith is established by a mix of people from Christian, Jewish, and Zoroastrian religious roots.

1949 World Peace Through World Religion

The first event takes place in Portland, Maine, to establish the foundation of World Religion Day.

1950 World Religion Day is First Observed

As World Peace Through World Religion begins to spread across the U.S., the celebration morphs into World Religion Day.

1957 Bahá'í Leadership Passes on to a Group

Rather than passing on from individual to individual, the death of Shoghi Effendi leads to the faith leadership passing to the Universal House of Justice.

World Religion Day FAQs

How many religions are there in the world?

Many scholars estimate that there are approximately 4,200 different active religions in the world today.

How many countries celebrate World Religion Day?

World Religion Day is currently celebrated in over 80 countries around the globe.

Which religion has the most adherents?

Christianity tops the list, with a whopping 2,3 billion. Next comes Islam with 1,8 billion. Third on the list are those unaffiliated with any particular religion, at 1,2 billion.

How to Observe World Religion Day

Attend an interfaith event

Engage with other religions

Try out a different religious experience

Many different organizations hold interfaith events on this day, where people can get together and hear about the beliefs and philosophies held by others of different faiths. These events are great spaces for eminent speakers, writers, and spiritual leaders to share openly about what they subscribe to, and why.

World Religion Day provides the perfect opportunity for people to step out of their individual bubbles and engage with the beliefs and spiritual ideologies of others. It’s about dialogue and the freedom to both express and listen; most importantly, it’s a time to learn from each other. This day reminds us that religion does not have to be a taboo subject, and everyone has a unique story to tell.

Religion is often inextricably linked with culture, so why not experience the best of both by attending a religious event of some sort, outside of your own? Whether it is going to a mosque or temple, or celebrating a religious festival you are not familiar with, it’s a great way to make inroads into different community groups and build relationships.

5 Facts About World Religions You May Not Know

You name it, there’s a patron saint for it

Wicca is not an ancient religion

Mormons have limited beverage options

The “Qur’an” mentions Jesus more than Muhammad

Hindus can also be atheists

In Catholicism, there is a patron saint for nearly everything, including coffee, beekeepers, and headaches.

Though it sounds like it would be ancient, considering its roots in European fertility cults, Wicca was introduced in the 1950s.

Mormons are forbidden from drinking beverages like tea, coffee, or alcohol; soda, however, seems to be okay.

Though this is not a popularity contest, the “Qur’an” apparently mentions Jesus Christ five times more than Muhammad.

While Hinduism is a polytheistic religion, it is also possible to be a practicing Hindu and an atheist — the moral and ethical code remains the same.

Why World Religion Day is Important

It purports to unite people

Interfaith harmony

A chance to experience something different

We love any day that seeks to bring people together, irrespective of differences, and this day fits the bill exactly. Whatever one’s religious beliefs and culture, the longing for acceptance and unity will be a fundamentally human one that unites us already.

World Religion Day offers people across the globe a chance to get to know others of different religions better, and seeks to foster a better understanding of religious differences through peaceful means such as dialogue.

The various interfaith and religious events organized by communities around the world are an exciting opportunity and opening for people to immerse themselves in spiritual experiences different from what they know. And so much of it is cultural that we see it as a win-win.

Source

#Historic Anglican Church of St. Clement#Cathedral of Our Lady of the Holy Rosary#Seville Cathedral#Salt Lake Temple#Spain#Salt Lake City#Sweden#USA#Fredrikskyrkan Church#Karlskrona#original photography#architecture#cityscape#tourist attraction#landmark#Temple Emanu-El#Miami Beach#Temple Adath Yeshurun#Saint George Tropoforos Hellenic Orthodox Church#Syracuse#New York City#St. Patrick's Cathedral#Notre-Dame Basilica of Montréal#Amman#World Religion Day#21 January 2024#third Sunday in January#Basilica of Saints Peter and Paul

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Public Prosecutor's Office on Waterfortstraat in Punda, Willemstad, Curaçao, is the former Temple Emanu-El (1867) which ceased to be a synagogue in 1963.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Uggghhh, what is UP with Canada?!

In Vancouver, the Schara Tzedeck synagogue's windows were smashed on April 19th.

In Toronto on April 19, five windows at the Kehillat Shaarei Torah synagogue were smashed with a hammer.

In Toronto on April 26, someone set a sign on fire at Beth Tikvah Synagogue....

....And again on April 28.

In Toronto in May, Jewish community members started escorting a kid to school because he was being bullied by peers who told him, "We're going to do to you what Hamas did to Israel," pushed him, kicked him, threw stones at him, and told him, "we need to kill you." This had been going on for six months. (His family had gone to both the school and police repeatedly at this point and it had only escalated; the kids throwing stones at him on the way to school was new.)

In Toronto on May 17th, Kehillat Shaarei Torah's windows were smashed again.

On May 25th before dawn, two people shot at Bais Chaya Muska, a Jewish girls' school in Toronto.

On May 29th, in the middle of the night, someone shot at the Belz Yeshiva Ketana school in Montreal.

In Vancouver on May 30, someone poured fuel on the doors of the Schara Tzedeck synagogue, then firebombed them.

In an article on June 7, Rabbi Lisa Grushcow of Emanu-El-Beth Sholom synagogue in Montreal said people have yelled “Hitler was right!” and “Jew!” at her congregants as they arrive for Shabbat services and that Jewish kids are being bullied in local schools.

On June 1 in Toronto, a man smashed the window of the Anshei Minsk synagogue with a rock.

On June 3 in Kitchener, someone smashed the front door of Beth Jacob synagogue.

On June 19th in Montreal, three small bullet-like holes were somehow made in the windows of Falafel Yoni. (I don't know, all the articles go out of their way to say they don't know WHAT made the holes.) Falafel Yoni is owned by a Jewish man who was born in Israel, and has appeared on boycott lists despite the owner never having said anything political about Israel.

On the same day, down the street from Falafel Yoni, someone smashed the windows of a nearby gym whose co-owner is Jewish and had also been born in Israel.

On June 30 in Toronto, someone threw stones at the Pride of Israel synagogue, then at Kehillat Shaarei Torah, smashing windows (again) in the latter.

On the weekend of July 27th, a father and son in Toronto were arrested for planning a terrorist attack and murder on behalf of ISIL, which is wild.

On July 29th, someone torched a bus belonging to the Bobov Hassidic school in Toronto.

And smashed the windows of a DIFFERENT Jewish school in Toronto, Leo Baeck Jewish Day School, and set it on fire.

On July 31 in Toronto, guess which synagogue had three signs set on fire? That's right: Kehillat Shaarei Torah.

Plus one sign set afire at Toronto's Temple Sinai Congregation the same night, presumably by the same arsonist, who might even have been the stone-hurler of June 30.

There are probably ones I missed. Just putting this list together took like three hours, though. I kept having to go, "Wait, surely that can't be the same synagogue AGAIN" and "they only mention the closest major intersection, which one was this?!" and "that can't be a different one, how many windows did they smash??" and go look for more sources. Plus a couple of articles were giving conflicting dates for one of the incidents.

And nobody ever gives actual dates, they just say shit like, "Blah blah blah was reported Monday...." so I have to look at the article date and then look at a damn calendar.

I went back as far as April because everything I found was referring to earlier incidents. Back to April. February and March were relatively quiet, at least in the news. Although interestingly, February is when the most hate crimes in Toronto had been reported, at least as of ... oh, I see.

As of March.

On the bright side, I did discover that Kehillat Shaarei Torah consistently has great jokes on its sign.

#antisemitism#judenhass is such a good word#jew hatred is what it means#reblog to fight antisemitism#jumblr#jewblr#wall of words#gun violence tw

442 notes

·

View notes

Text

More than 50 rabbis and cantors, including leaders of some of New York City’s most prominent synagogues, signed an open letter Tuesday asking Mayor Eric Adams and New York Gov. Kathy Hochul to protect immigrants from the Trump administration’s planned mass deportations.

The letter, the latest in a succession of recent statements by Jewish leaders opposing President Donald Trump’s policies, comes at an unprecedentedly fraught time in the politics of New York City and state. The Trump administration has moved to drop corruption charges against Adams so that he will be able to help the Trump administration’s crackdown on undocumented immigrants.

The arrangement has led to a cascade of resignations at top levels of city government and beyond along with mounting calls for Adams to resign — which he has rebuffed.

And relations between Hochul and Adams aren’t exactly tranquil. The evening before the rabbis’ letter was published, Hochul said she would be meeting with “key leaders” to discuss taking the step of removing Adams from office, which no governor has ever done in the state’s history.

Against that backdrop, the letter asks Adams and Hochul “to be the leaders we desperately need at this moment, and do all you can to resist Trump’s terrifying anti-immigrant agenda.” It does not reference the controversy surrounding Adams.

The letter calls on the mayor and governor to “restrict” immigration raids in schools and houses of worship, which are now permitted under new federal guidelines. It also calls on the leaders to refrain from sharing information with Immigration and Customs Enforcement and to not use jails to detain immigrants. And it hearkens back to American Jews’ immigrant heritage, particularly in New York, as well as past antisemitic persecution.

“We also know in our bones and from our modern history the danger of an unchecked xenophobic government scapegoating ‘outsiders’ to gain power, preying on a population experiencing hard economic times to gain support for a violent and destructive agenda,” the letter said. “We will not stand by while history repeats itself. You, our state and local leaders, must not either.”

The letter follows others signed by Jewish leaders or organizations opposing Trump’s or Republicans’ policies on transgender athletes, mass deportations, Gaza and diversity, equity and inclusion, or DEI. Jewish groups have also joined lawsuits challenging Trump’s immigration actions.

The letters signatories hail from the Reform, Conservative and Reconstructionist movements, and include leaders of large synagogues such as Temple Emanu-El, B’nai Jeshurun, Ansche Chesed, Congregation Beth Elohim, Forest Hills Jewish Center, Congregation Beit Simchat Torah, Society for the Advancement of Judaism and others. Not all rabbis who signed appended the names of their synagogues.

The letter was organized by a consortium of progressive Jewish groups in the city, including Bend the Arc, the Jewish refugee aid group HIAS, Jews For Racial & Economic Justice, New York Jewish Agenda, the immigration advocacy group Never Again Action, the liberal rabbinic human rights group T’ruah and The Workers Circle.

47 notes

·

View notes

Text

These are the three menorahs that we own that we did not light this year (but we did display them).

The first one is an artsy menorah that I'm pretty sure we got at the same time as our oil one. It is very much not my style and has never been. We've never used it, likely because my mom doesn't want to bother with having to clean out the wax from various places, which I get.

The second one is Synagogues of Europe by artist Maude Weisser. The plaque on it says it was made in 1995, but I'm not sure when/where we bought it. As you can see, it hasn't survived previous lightings very well, which is why we didn't light it or the next one.

The synagogues depicted are (from right to left):

Prague, Czechoslovakia: The Altneuschul or "Old-New Synagogue" (c.1280)

Toledo, Spain: Santa Maria La Blanca Synagogue (c. 1200)

Dubrovnik, Yugoslavia: The Dubrovnik Synagogue was built in the 17th century

Cracow, Poland: The Rema Synagogue (c. 1550)

Vilna, Poland: This gate is located at the entrance to the Shulhof on Jews' Street in the Jewish Quarter of Vila.

Lutsk, Poland: The Lutsh Fortress Synagogue (c. 1626)

Zabludow, Poland: The Zabludow Synagogue (c. 1756)

Budapest, Hungary: The Synagogue in Obuda (1820)

Florence, Italy: Tiempo Israelitico, completed (1882)

The third one is Synagogues of North America, also by artist Maude Weisser. This one has a little plaque that says it was designed in 1997, but we got it two summers ago at the Touro Synagogue (the synagogue on the far right), the first purpose-built synagogue in the United States, in Newport, Rhode Island, where the artist herself was working (!!!).

The synagogues depicted are (from right to left):

Newport, Rhode Island: Touro Synagogue (dedicated 1763)

New York City: Temple Emanu-El (built in 1929)

New York City: B'nai Jeshurun (consecrated in 1827)

Elkins Park, Pennsylvania: Beth Shalom (built in 1959; designed by Frank Lloyd Wright)

San Fransisco, California: Shearith Israel (built in 1854)

Cincinnati, Ohio: Congregation B'nai Jeshurun (built in 1848)

Boston, Massachusetts: The Vilna Shul (built in 1919)

Chicago, Illinois: Kehilat Anshei Ma'Arav (built in 1891)

Charleston, South Carolina: Beth Elohim (built in 1840)

Bonus: a shot of all our menorahs because seven nights’ worth of candles is too pretty not to share:

#Hanukkah#Chanukah#hanukkiah#menorah#my hanukkiot#synagogue#synagogues of europe#synagogues of north america#maude weisser#long post#my menorahs#chanukahproject

13 notes

·

View notes

Note

Temple Emanu-El, New York City, New York, USA (the largest synagogue in the USA!)

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

A while ago, I made a post to help spread the link so people could donate to the Montana Jewish Project to buy back Temple Emanu-El. Which was successful! Yay!

But now they need to raise some money again! This time, its to fund a new roof for the building! They are asking for $100,000 by October 15 this year. I have added a link to their own fundraising site so anyone who can spare a few dollars can chip in too. Lets help again some more!

#jewish#judaism#fundraising#jumblr#hoping adding some relevant tags can help spread!#montana jewish project#I'm not jewish myself but I am a montanan and it's important to help our neighbors <3

59 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0zJjPn1QIcc

Here’s a piece of classic nineteenth-century American Reform music that I came across pretty much by accident. I was researching a bit about Julie Rosewald, the first woman known to have served as a cantor in the United States. She was at Temple Emanu-El in San Francisco, and served from 1884 to 1893. This was originally meant to be an interim posting, but they really loved her at Temple Emanu-El, and it did actually take them nine years to get around to doing a serious search for their next cantor.

This piece is by Cantor Edward Stark, the fellow who Temple Emanu-El eventually got around to hiring, and therefore Julie Rosewald’s successor. Stark was from Hohenems in Austria, notably also the hometown of Salomon Sulzer, and in fact his father Josef was one of Sulzer’s students. Josef passed this training on to his sons. Stark moved to the United States in 1871, at age fifteen, continued his musical training, and took cantorial positions in New York before moving out to San Francisco to step into the shoes of the beloved “Cantor Soprano.”

He was a big supporter of organ music in Reform synagogues, and seems to have spent much of his career working on ways to blend Jewish nusach and Western ideas of harmony and tonality. This was a significant project that a lot of composers have worked on, and everyone manages the balance a little differently. Here is how Cantor Stark did it!

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

From the MJP's website:

We Did It!

On August 25, 2022, the Montana Jewish Project closed on the Temple Emanu-El building returning the building to Jewish hands for the first time in 87 years.

The past months have sometimes felt like pushing a boulder up a mountain trail. Without the incredible community support we received, MJP would not be reclaiming this building. Every dollar donated, every collection raised from a synagogue or church, every fundraiser held in MJP’s honor brought this, every volunteer hour, and every email sharing hope and ideas helped bring us to this joyful day.

Help a Jewish Community Buy Back Its Own Damn Synagogue!

Firsty, thank you for reading this, and I hope you’ll get through it and give us the honor of a donation, firstly, and a reblog, secondly. Maybe even a note to any friends you have outside of tumblr!

If you don’t care about the history, skip to the bold at the end!

This is Temple Emanu-El, in Helena, Montana. At the time it was built, it was the only synagogue between Minneapolis, Minnesota, and Portland, Oregon. It was built with the hard work of the Jewish community that had come west to seek their fortune and stability, having heard that people were more willing to do business with Jews in the West, a place where social strictures were slightly relaxed. This turned out to be true, and the community thrived.

This picture resolves small on tumblr, but you can see the love and care they put into it. It’s modeled after the great synagogues of Europe, with heavy stonework, onion domes, and intricate stained glass. The president of the congregation cried at its opening and dedication.

As the years went on, the West became more settled, and for a series of socio-political reasons of which my History of the American West major ass is well aware but are ultimately unimportant to the issue at hand, Jewish communities left much of the interior west for metropolitan areas. By the 1930s, the Jewish community was so small that they could not justify the large and lavish worship center.

They sold it to the city for one dollar.

The promise made to them was that it would be used for the public good. The state readied the former temple for its new function as offices for Social and Rehabilitation Services, sandblasting of the Hebrew inscription, “Gate to the Eternal,” above the entry and removing the star-studded, painted domes.. The copper was stripped from the building and likely reused to re-clad the State Capitol’s dome at about the same time.

That lasted all of 40 years, when the State of Montana decided to let it sit idle and decay, so they could justify the sale of the building, sold for a pittance to the public good, to the Helena Catholic Diocese for $83,000 (this is an opinion of mine, though it is not an uneducated one, and I do firmly believe it. I do not, however, represent that they allowed it to fall into disrepair to justify the sale as objective fact.)

This is the building now

In a twist of fate, the diocese can no longer afford to maintain the building. They are selling it, and the Jewish community of Helena is trying to buy it.

The Montana Jewish Project is being far far far nicer and more politic about this than I would be, but in fairness, they actually how to get Nice Goyim to donate, and I don’t, so. The Diocese is spinning this as selling the building for much less than its worth, which may be true, but if you bought it for $83,000, that would be $280,000 now.

They are selling it for $925,000. And we have to have 70% of the purchase price by February 28th. Easy terms, right?

Here’s where you come in! If the idea of Montana’s Jews getting back the building that was sold to the Diocese in spite of the original agreement appeals to you, you can and should donate to their capital campaign. They even have an option for your donation where if we don’t get Emanu-El back, your money will be returned to you instead of being used for other MJP protects and repairs.

This place won’t just be used for the Jewish community, though I think that would be enough. They want it to be used as a museum and center for the community as well, to teach about Jewish life in Montana, with Jewish cooking classes, and social programs, and teaching non-Jews about Jewish customs and culture.

I just want to get the cross off the top.

Donate here

28K notes

·

View notes

Text

Station #7: HaSephardim

This station is located at The Bronx Way and Amir Al-Mu'minin Road. Named for the Sephardic Jewish community, it's the largest synagogue in the city. I believe it's the largest religious structure in the city as well. I imagine it looks like the large Temple Emanu-El in NYC, too.

Amir Al-Mu'minin Road is named after Imam Ali ibn Abi Talib (عليه السلام). This station is at the border of the Imam Al-Husayn and Centrum neighborhoods.

Two lines stop here:

The Bronx (purple)

Imam Ali (brown)

#cartography#map#fictional city#chaxel#urban planning#metro#fictional cities#maps#fictional map#street

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nestor Miguel Torres (April 25, 1957) a virtuoso technician Classical, jazz, and composer was born in Mayagüez, Puerto Rico to Nestor Torres Sr., pianist and vibraphone, and Ana E. Salcedo Baldovino-Torres. He skipped two grades, began flute studies at 12, and began studies at Interamerican University. He took classes at the New England Conservatory of Music. He received a BSM from Berklee College of Music at the age of 16. He received an Artist Diploma from the Mannes School of Music.

He performed with the Florida Philharmonic Orchestra and the New World Symphony. He appeared in Cachao: Como su ritmo no hay dos. He released the album, Burning Whispers, which sold more than 50,000 copies.

He married Patricia San Pedro (2002). He was a central attraction at Connecticut’s Greater Hartford Festival of Jazz. Mayor Eddie Perez proclaimed August 19, 2004, as “Nestor Torres Day” with two concerts at Hartford’s Keney Park and Arch Street Tavern.

He played at the World Music Concert during One World Week at the University of Warwick. At the 51st Annual Grammy Awards, he was nominated for “Best Latin Jazz Album Nouveau Latino.

He played at the Herbst Theatre in the San Francisco Civic Center where he performed “Tango Meets Jazz.” He performed at the 21st Central American and Caribbean Games in Mayagüez, Puerto and presented his composition “Saint Peter’s Prayer” for the Dalai Lama at Miami Beach’s Temple Emanu-El. He became the founding director of the Florida International University’s first charanga ensemble, made up of winds, strings, and percussion instruments used to perform traditional and modern versions of folk music from the Caribbean and especially Cuba.

He premiered his composition “Successors” for the concert, “Voices of the Future ” performed with the Miami Children’s Chorus at the New World Center on Miami Beach. In 2017, he released his first album of Latin American classical flute music, Del Caribe, Soy!

His music is a crossover fusion of Latin, Classical, Jazz, and Pop sounds. #africanhistory365 #africanexcellence

0 notes

Text

Temple Emanu-El Members Vote to Approve Selling Main Street, Haverhill, Building

Methuen’s Christian Family Center seeks to buy the building that houses Haverhill’s Temple Emanu-El on Main Street. Temple President Jennifer Lampron formally notified members in an email Thursday and asked for support to cover any contingencies that may arise as the proposed buyer continues building inspections. Lampron told WHAV last August, the congregation has been aging and many members lost…

0 notes

Text

So "Temple Emanu-El" it is, then

Jews. Yidn. People of the Hebraic persuasion. I call you to assembly to discuss a serious issue.

We need to stop naming our synagogues Beth Israel. There's--there's too many of them. There's a Beth Israel in every city, maybe even multiple Beth Israels in the bigger ones. This madness has to stop. We need different names. There are too many Beth Israels.

248 notes

·

View notes