#Shaybanids

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Photo

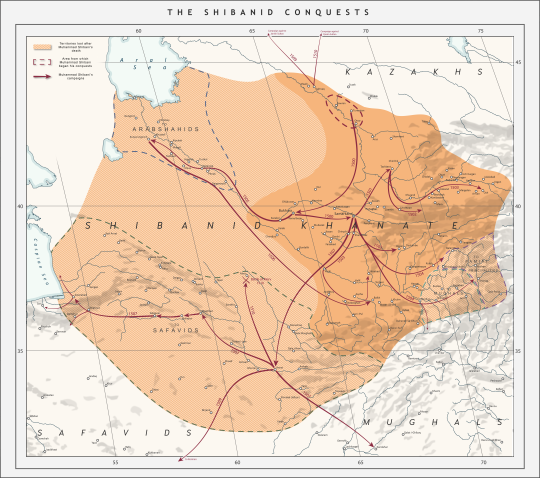

The Shibanid (Shaybanid) Conquests, 1500-1510.

by u/Swordrist

This is my attempt at covering an underapreciated area of history which gets next-to no coverage on the internet. Here's some historical context for those uneducated about the region's history:

Grandson of the former Uzbek Khan, Abulkhayr, Muhammad Shibani (or Shaybani) was a member of the clan labeled in modern historiography as the Abulkhayrids, who were one of the numerous tribes which were descended from Chingis Khan through Jochi's son, Shiban, hence the label 'Shibanid' which is used not only in relation to the Abulkhayrids who ruled over Bukhara but also for the Arabshahids, bitter rivals of the Abulkhayrids who would rule Khwaresm after Muhammad Shibani's death and for the ruling Shibanid dynasty of the Sibir Khanate.

After his grandfather's death in 1468, Shibani's father, Shah Budaq failed to maintain Abulkhayr's vast polity in the Dasht i-Qipchak, as the tribes elected instead the Arabshahid Yadigar Khan. Shah Budaq was killed by the Khan of Sibir and Shibani was forced to flee south to the Syr Darya region when the Kazakhs returned and proclaimed their leader, Janibek, Khan. Shibani became a mercenary, serving both the Timurid and their Moghul enemies in their wars over the eastern peripheries of Transoxiana. After the crushing defeat of the Timurid Sultan Ahmed Mirza, Shibani succeeded in attracting a significant following of Uzbeks which formed the powerbase from he launched his conquests.

Emerging from Sighnaq in 1499, Muhammad Shibani captured Bukhara and Samarkand in 1500. In the same year he defeated an attempt by Babur (founder of the Mughal Empire) to take Samarkand. Over the course of the next six years, Shibani and the Uzbek Sultans conquered Tashkent, Ferghana, Khwarezm and the mountainous Pamir and Badakhshan areas. In 1506, he crossed the Amu-Darya and captured Balkh. The Timurid Sultan of Herat, Husayn Bayqara moved against him however died en-route and his two squabbling sons were defeated and killed. The following year he crossed the Amu-Darya again, this time vanquishing the Timurids of Herat and Jam and subjugating the entirety of Khorasan east of Astarabad. In 1508, he raided as far south as Kerman and Kandahar, however he moved back North and launched two campaigns against the Kazakhs, but the third one launched in 1510 ended in his defeat and retreat to Samarkand at the hands of Qasim Sultan.

The Abulkhayrid conquests heralded a mass migration of over 300 000 Uzbeks to the settled regions of Central Asia from the Dasht i-Qipchak. They heralded the return of Chingissid political tradition and structures and the end of the Persianate Timurid polities which had dominated the region for the last century. It forever after changed the demographic of the region. His reign was also the last time Transoxiana was closely linked with Khorasan, as following the shiite Safavid conquests the divide between the two regions would grow into a permanent one.

In 1510, Shibani faced his end when he moved to face Ismail Safavid, who was making moves on Khorasan. Lacking the support of the Abulkhayrid Sultans, who blamed him for their defeat against the Kazakhs earlier that year, he faced Ismail anyway, where he was defeated, killed and turned into a drinking cup.

Shibani's death caused a complete reversal of the Abulkhayrid fortunes. Khorasan and the rest of his empire fell under Safavid dominion. However in Khwaresm, Sultan Budaq's old rivals the Arabshahids expelled the qizilbash and founded their own Khanate, based first in Urgench and then Khiva. In Transoxiana, Babur lost the support of the populace when he announced his conversion to Shiism and his loyalty to Shah Ismail, which allowed the Abulkhayrids to rally behind Shibani's nephew, Ubaydullah Khan and expel the Qizilbash. Nonetheless, the Abulkhayrids would never again hold as much power as they briefly did when led by Muhammad Shibani Khan.

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

Мухаммед Юсуф Мунши. Муким-ханская история (1956)

Мухаммед Юсуф Мунши. Муким-ханская история (1956) https://www.avetruthbooks.com/2023/09/mukhammed-jusuf-munshi-mukim-khanskaja-istorija-1956.html?feed_id=17454

#History#HistoricalsourcesinPersian#HistoryofTurkicPeoples#Janids#KhanateofBalkh#KhanateofBukhara#MuhammadShaybani#MuhammadYusufMunshi#Shaybanids#UzbekKhanates

0 notes

Text

Registan. Samarkand, Uzbekistan (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) (7) by Caspar Tromp

Via Flickr:

(1) Façade of the early 15th century madrasah built by Ulugh Bey, the grandson of Amir Timur (Tamerlane). Ulugh Bey enjoyed more the arts and sciences than his warlord grandfather. This madrasah is the oldest of the 3 at the Registan ensemble. (3) (4) (5) Souvenir shops in the many cells of the once 17th century madrasah built by the Shaybanid rulers of Samarkand. As a madrasah, it was once a school for Muslims in which not only religion but also mathematics, astronomy, medicine and philosophy, among others, were taught. Now colourful - and often hawking - Uzbek women are selling eastern handicrafts.

#madrasah#madrasa#islamic architecture#market#market stalls#people#city life#textiles#tiles#uzbekistan#samarkand

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

Angel seated on a carpet. Shaybanid dynasty. Uzbekistan, painted in India ~ ca.1555

0 notes

Photo

Tree and birds in autumn (detail from a detached album folio). Bukhara, Uzbekistan, ca. 1520-1530 (Shaybanid dynasty, Uzbek period)

12 notes

·

View notes

Photo

In the mid 15th century, much of the eastern portion of the former Golden Horde (the White Horde) came under the control of the Chinggisid ruler Abu'lkhayr Khan, under whose rule the Uzbeks would emerge. Abu'lkhayr's efforts to crush potential threats to his position by killing off other descendants of Chinggis Khan's eldest son Jochi led to the flight of Janibek and Kirei, the founders of the Kazakh Khanate, from Uzbek territory to Moghulistan. In 1468, either against Janibek and Kirei or the Oirats, Abu'lkhayr and his son were killed in battle, and the Uzbek Khanate fractured. The Kazakhs came to dominate the north eastern expanse of this territory, while Abu'lkhayr's grandson Muhammad Shaybani (Shiban(Shayban) was one of Jochi's sons) was forced to live for years effectively as a raider and minor, regional lord, slowly gaining followers in a similar manner to Janibek and Kirei. By the early 16th century, Shaybani was able to establish his own empire in modern Uzbekistan, the Shaybanid empire based in Samarkand and Bukhara. Much of his reign was occupied with conflict with his neighbours: the Kazakhs to the north, the Safavids to the south and Moghuls to the east. Shaybani fought several campaigns against another minor Chinggisid lord, Babur, who fled south and eventually established the Moghul Empire in India. Shaybani's campaigns in the first decade of the 16th century were largely successful, until he bit off a bit more than he could swallow against the Safavid Shah, Ismail I. In 1510, the Shah defeated the Khan at Merv, having felt threatened by Shaybani's overtures to the Ottoman Empire, the Safavid's great enemy in the west. Ismail had Shaybani dismembered and his skull encased in gold to use as a drinking goblet. Ismail came to view himself as an invincible conqueror, an aura which was shattered when he was defeated at Chaldiron in 1514 by the Ottoman Sultan Selim I "the Grim," Shaybani's potential ally and avenger. Safavid horse archers proved highly disadvantaged against the artillery and gunpowder of the Ottoman lines, and Chaldiron is often presented as the end of the period of the dominance of horse mounted archers on the battlefield. Selim went on to greatly expand the Ottoman Empire, while Ismail spent the rest of his life despondent and fell into alcoholism, drinking his sorrows away with the skull of Shaybani. To learn more about Shaybani and the Kazakhs, check out my video on the origins of the Kazakh Khanate: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-mXVjuy56rg

#kazakh#uzbek#kazakhstan#uzbekistan#shaybani#shaybanid#golden horde#khanate#safavid#ismail#ottoman empire#moghul empire#chinggis khan#chaldiron#history#military history#jackmeister#youtube#genghis khan#battle#merv#selim#khan

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Tree and birds in Autumn (detail from a detached album folio) Bukhara, Uzbekistan, ca. 1520-1530 (Shaybanid dynasty, Uzbek period).

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Siberian History (Part 5): Khanate of Sibir

By the end of the 1500s, a large part of the world had been mapped well, but not Siberia – its ice-laden seas along the northern coast had hindered mariners who were searching for China or “Cathay”. Map-makers labelled Northern Asia as Tartary or Great Tartary, but gave it no geographic detail. The Ob River (thought to have its source in the Aral Sea) was as far east as people had got from the west.

When shown on maps, Tartary was filled in according to the stories and legends the mapmakers had heard – Asiatic nomads among camels and tents, or worshipping idols and pillars of stone. Sometimes there were accompanying inscriptions identifying them as cannimals, or claiming that they “doe eate serpentes, wormes and other filth”. Other customs ascribed to them were copied from Central Asian tribes that the mapmakers knew about.

Siberia was also seen as an other-worldly, mythological land that extended even as far as the sunrise. From one contemporary source, “to the east of the sun, to the most-high mountain Karkaraur, where dwell the one-armed, one-footed folk.”

However, a little was known about Siberia. The Russian Chronicles (chronological records kept by monasteries since the beginning of Russian history) mentioned the territory. Russian merchants who traded in furs with tribes along the Ob River had long been familiar withYugra (meaning “the land of the Ostyaks”, a local tribe now known as the Khanty). This was a collective name for the lands & peoples between the Pechora River (west) and the Ural Mountains (east).

In 1236, an itinerant Brother Julian mentioned a “land of Sibur, surrounded by the Northern Sea”. In 1376, St. Stephen of Perm established a church in the Kama River Valley (west of the Urals), where a former missionary had earlier been skinned alive.

Russia began to give the missionaries military backing in 1455, and soldiers swept along the frontier in 1484. They captured some tribal chieftains, who were then forced into a treaty that acknowledged Moscow's suzerainty and made them pay tribute.

Khanate of Sibir

The Khanate of Sibir had been established in 1420 when the Mongol Empire was breakking up. It was a semi-feudal state just east of the Ural Mountains. It was dominated by the Siberian Tatars, who descended from one of the Mongol fighting groups, or “hordes”. The khanate included Siberian Tatars (Turkic & Muslim), Bashkirs, and various Uralic peoples (including the Khanty, Mansi and Selkup peoples). Its ruling class was Turco-Mongol. The khanate's territory stretched east of the Urals to the Irtysh River, and south to the Ishim steppes.

Approximate extent of the Khanate of Sibir in the 1400s - 1500s.

Now it came within the orbit of Muscovite political & military relations. Moscow had become familiar with the northern sea route from Archangel, although only as far as the northern end of the Ural Mountains. But there wasn't a southern route into Sibir until Kazan (another Mongol succession state on the Volga River) was captured in 1552. In 1555, the Taibugid Khan Yadigar acknowledged Ivan the Terrible's suzerainty; Ivan immediately began calling himself the “Tsar of Sibir”.

But Russia still didn't known that beyond the Ob River, Siberia stretched as far as Northern Asia, from the Ural Mountains to the Pacific Ocean.

Sibir was a coherent, loosely-confederated state, with trade along ancient caravan routes to western China. However, it was beset by internal problems as was basically living on borrowed time. The Siberian Tatars (who had converted to Islam in 1272) clashed with other ethnic groups. There were inter-tribal hostilities, particularly between the Khanty and Mansi (or Ostyaks and Voguls, as they were called at the time). From the founding of Sibir, there had been a dynastic struggle between the Shaybanids (descendants of Genghis Khan) and the Taibugids (heirs of a local prince). Until 1552, the Kazakh Khanate (also Tatar) stood between Sibir and Russia, but now that was not the case anymore.

Along with acknowledging Russia's suzerainty, Yadigar also agreed to pay annual tribute (in the form of furs) to Ivan. This was an unpopular decision. It may well have been the reason that in 1563, he was desposed and killed in on the banks of the Irtysh River, in his capital of Qashliq (also called Isker), by Khan Kuchum, who claimed descent from Genghis Khan.

Kuchum then surrounded himself with a palace guard composed of Uzbeks, purged the local leadership of opponents, and tried to impose Islam on the pagan tribes (with the help of mullahs from Bukhara, now in Uzbekistans.

By 1571, Russia was struggling and appeared to be in the process of falling apart. Kuchum took the opportunity to renounce the tribute to Moscow. In 1573, he sent a punitive expedition against the Khanty people in Perm (west of the Urals), who had recognized Russian suzerainty. Moscow gave no response, so in 1579 he also intercepted and killed a Muscovite envoy that was en route to Central Asia.

The Stroganovs

During the Livonian War (1557 – 1581), in which Ivan the Terrible tried to force his way to the Baltic, Moscow's government had handed the defence of their eastern frontier and Urals dominions to the Stroganov family. They were a powerful family of industrial magnates and financiers. According to legend, they were descended from a Christianized Tartar called Spiridon, who had introduced the abacus to Russia. Their wealth was founded on furs, ore, salt and grain (the mainstays of the economy). They had accumulated a great deal of assets & properties over the past 200yrs, extending from Kaluga and Ryazan eastwards to the current Vologda Oblast. They traded with the English & Dutch on the Kola Peninsula, established commercial links with Central Asia, and had foreign agents who travelled as far abroad as Antwerp and Paris for them.

They were originally centered on their saltworks at Solvyechegodsk (Russia's “Salt Lake City”), but a rapid series of land grants secured their absolute commercial domination of the Russian north-east. In 1558, Ivan the Terrible authorized a charter giving Anikey Stroganov and his successors large estates along the eastern edge of Russian settlement, along the Kama and Chusovaya Rivers – this gave them access to much of Perm, on the Upper Kama River almost to the Urals.

Map of the Kama River Basin. A black diamond shows the location of Perm; grey rectangles show the Kama and Chusovaya Rivers.

The 1558 charter served as a model for future dealings with the Stroganovs. In each case, the Stroganovs pledged to fund and develop industres; break the soil for agriculture; train and equip a frontier guard; prospect for ore and mineral deposits, and mine whatever was found. In return, they were given long-term tax-exempt status for themselves and their colonists.

The Stroganovs had jurisdiction over the local population, and had the right to protect their holdings with garrisoned stockades and forts equipped with artillery. A chain of military outposts and watchtowers was soon growing along the river route to the east.

Colonization was advancing to the foot of the Ural Mountains, and the Stroganovs tried to subject a number of native tribes to their authority, including the Khanty and Mansi peoples, who lived on both sides of the Urals. The native peoples fought back – they destroyed crops; attacked villages, saltworks and flour mills; and massacred settlers on the western slopes of the Urals. Soldiers were sent to deal with uprisings, but they couldn't be spared for very long from the tsar's western fronts.

Meanwhile, prospectors had found silver and iron ore deposits on the Tura River, east of the Urals. It was assumed (correctly) that the districts it was found in also had sulphur, lead and tin. Also, scouts had seen the rich pastures by the Tobol River where the Tatars' cattle grazed.

In 1574, the Stroganovs petitioned for a new charter “to drive a wedge between the Siberian Tartars and the Nogays” (a tribe to the south), by means of fortified settlements. In return, they would be given a licence to exploit the region's resources. Moscow (in response to Kuchum's aggression) agred.

Because the Livonian War meant that soldiers couldn't be spared for long, the Stroganovs were also given permission to enlist runaways or outlaws in their militia; and to finance a campaign against Kuchum “to make him pay the tribute”. The campaign would be spearheaded by “hired Cossacks and artillery”. The government promised that those who volunteered would be rewarded with the wives & children of natives as their concubines & slaves.

Cossacks

“Cossacks” were independent frontiermen who lived along the empire's fringes. Some were solitary wanderers, or mixed-race peoples. There was also a turbulent border population of itinerant workers, tramps, runaways, bandits, adventurers and religious dissenters, who had been forced to move to this no-man's-land of forest & steppe by taxation, debt, repression, famine, or refuge from Muscovite law. Here they mingled and clashed with the Tatars, adopted Tatar terminology, and created a new independent life for themselves. The term “Cossack” comes from the Turkish kazak, meaning “rebel/freeman”.

Some Cossacks had banded together under elected atamans (chieftains) into semi-military groups along the Volga, Dnieper and Don Rivers, in order to protect their homesteading communities. They raided Tatar settlements, poached on Tatar land, preyed on Moscow river convoys, and ambushed government army patrols who had been sent to catch and hang them.

Vasily “Yermak” Timofeyevich was the leader of a Cossack band. He was a third-generation bandit, and the most notorious pirate on the Volga River of the time. He was powerfully-built, medium height, and had a flat face, black beard and curly hair. According to the Siberian Chronicles, “his associates called him 'Yermak,' after a millstone. And in his military achievements he was great.”

Regular army patrols (with gallows built on rafts) attempted to enforce the tsar's authority along the Volga trade route. There was a series of expeditions intended to crush or subdue outlaw bands, culminating in 1577 in a great sweep along both sides of the Volga. Many Cossacks were forced to flee, with the tsar's cavalry after them – some fled downstream to the Caspian Sea; some scattered across the steppes. According to legend, a third group under Yermak raced up the Kama River into the wilds of Perm, where they joined the Stroganovs' frontier guard and were enthusiastically welcomed into it.

The Expedition

A few years later, the Stroganovs organized an expedition to secure the Kama frontier, bring part of the Siberia within their mining monopoly, and gain access to Siberian furs. This did not fall under the tsar's commission.

The expedition began on September 1st, 1581. A Cossack army of 840 men (including 300 Livonian POWs, two priests, and a runaway monk impressed into service as a cook) assembled under Yermak's leadership on the banks of the Kama River near Orel-Gorodok, south of Solikamsk. According to the Chronicles, they set off “singing hymns to the Trinity, to God in his Glory, and to the most immaculate Mother of God,” but this probably didn't happen.

The military force had a rough code of martial law. Insubordination was punished by being bundled head-first into a sack, with a bag of sand tied to your chest, and being tipped into the river. About twenty people were tipped in at the start.

It is not certain whether the Stroganovs voluntarily provided full assistance to this expedition, or were coerced into it. However, they always drove a hard bargain, and intended their aid to be a loan “secured by indentures”. The Cossacks rejected this, and agreed to compensate them from their plunder; or if they failed to return, to redeem their obligations “by prayer in the next world”. The Siberian Chronicles portrayed this military expedition as a holy crusade against the infidel, so this sarcastic promise was reinterpreted as genuine and as religious fervour. One passage in the Siberian Chronicles states, “Kuchum led a sinful life. He had 100 wives, and youths as well as maidens, worshipped idols, and ate unclean foods.”

The army was organized into disciplined companies, each with its own leader and flag. Although they were vastly outnumbered by the khanate's troops, it wasn't as bad as it seemed. They were well-led, well-armed, and well-provisioned (with rye flour, buckwheat, roasted oats, butter, biscuit and salt pig). It was their military superiority through firearms that would prove decisive.

They moved along a network of rivers in doshchaniks (flat-bottomed boats that could be rowed with oars, mounted with a sail, or towed from the shore) to the foothills of the Urals (from the headwaters of the Serebryanka River to the banks of the Tagil River, at a site known today as Bear Rock). This was a distance of about 29km. Yermak then stopped and pitched his winter camp.

In spring, Yermak dammed the water with sails so that he could float the boats over the river's shallows. He boarded his boat downstream, swung into the Tura River, and for a some distance advanced without resistance into the heart of Kuchum's domain.

There was a costly skirmish at the mouth of the Tobol River. Then downstream, where the river surged through a ravine, the Tatars had laid a trap. There was a barrier made of logs and ropes, and hundreds of warriors hiding in the trees on either side of it. The first of Yermak's boats hit the barrier at night. The Tatars attacked, but in the darkness most of the boats managed to escape upstream. The Cossacks disembarked at a bend in the river, made mannequins out of twigs and fallen branches, and propped them up in the boats, with only skeleton crews at the oars. The others (half-naked) crept around to surprise the Tatars from behind. At dawn, they opened fire just as the flotilla floated into view. It was a complete rout, a great success for Yermak's men.

Kuchum resolved to destroy the Cossacks before they could even reach the capital of Qashliq. Yermak knew that he had to capture the town before winter, or his men would die from the cold. Their provisions were low, and ambush & disease had reduced their force by half. But they kept going towards Qashliq.

The decisive confrontation was in late October, at the confluence of the Tobol and Irtysh Rivers. Here, the Tatars had erected a palisade at the base of a hill. The Cossacks charged, firing their muskets into the densely-massed defenders, killing many. Many of the Tatars, conscripted by force, immediately deserted. More fled as the palisade was stormed. The battle continued until evening with hand-to-hand fighting. 107 Cossacks died, but they won the battle.

Kuchum is said to have had a vision on that day: “The skies burst open and terrifying warriors with shining wings appeared from the four cardinal points. Descending to the earth they encircled Kuchum's army and cried to him: 'Depart from this land, you infidel son of the dark demon, Mahomet, because now it belongs to the Almighty.'”

The Cossacks arrived at Qashliq a few days later. It was deserted, with few of its fabled riches left behind. However, they found stocks of flour, barley and dried fish.

Soon afterwards, Yermak began accepting tribute from former subjects of the khan, and there were scattered defections to the Cossacks' side. Yermak needed reinforcements & artillery to consolidate his position, so he sent his second-in-command Ivan Koltso (also a renowned bandit) to Moscow with 50 others. They took the fabled “wolf-path” shortcut over the Urals (up the Tavda River to Cherdyn), travelling on skis and reindeer-drawn sleds. This path was shown to them by a Tatar chieftain who acted as their guide.

But the tsar was not pleased with the expedition (he didn't yet know of Yermak's success). In response to the invasion, the Mansi had been burning Russian settlements to the ground in the Upper Kama Valley. Apparently on the day Yermak set out, they'd attacked Cherdyn and burned neighbouring villages. The military governor of Perm then accused the Stroganovs of leaving the frontier undefended, as they'd stripped the frontier guard for their expedition.

In a letter from November 16th, 1582, the tsar reproved the Stroganovs for “disobedience amounting to treason”. And the Livonian War, as it drew to a close, was being lost by the Russians. Narva had fallen to the Swedes, and the Poles were tightening their blockade on Pskov.

Koltso arrived in the capital, where the tsar was planning to hang him. He prostrated himself before Ivan, announced Yermak's capture of Qashliq, and proclaimed Ivan lord of the khanate. Then he displayed his spoils before the stunned court – these included three captured Tatar nobles and a sledload of pelts (2,400 sables, 2,000 beaver and 800 black foxes). This was equal to five times the annual tribue the khan had paid.

Ivan immediately pardoned Koltso, and Yermak in absentia. He promised reinforcements, and sent a suit of armour embossed with the imperial coat of arms to Yermak. Koltso kissed the cross in obedience to the tsar.

Failure

Back in Siberia, Yermak was struggling to extend his authority up the Irtysh River. He forced the native peoples to swear allegiance by kissing a bloody sword. The penalty for resisting was to be hanged upside-down by one foot, an agonizing death.

Yermak also tried to Christianize the tribes. In one contest of power, the local wizard ripped open his stomach with a knife, then miraculously healed the wound by smearing it with grass. In response, Yermak simply tossed the local wooden totems onto the fire.

By the end of summer 1584, Yermak had managed to extend his jurisdiction almost as far east as the Ob River. One sortie had surprised and captured Mametkul (Kuchum's nephew and minister of war). Things appeared to be going well.

Meanwhile, however, the Tatar raiders who had been attacking the Russian settlements returned. Yermak's strength declined by attrition. 500 Russian reinforcements tramped into Qashliq on snowshoes in November, but they'd brought no provisions of their own, and rapidly used up Yermak's resources. During the long winter, part of the garrison starved; some were forced to resort to cannibalizing their dead companions.

Kuchum's followers were aware of all this, and in the spring they increased their attacks on foraging parties. There were two major blows to the Russians: 1) 20 Cossacks were killed as they dozed by a lake, and 2) Koltso and 40 others were lured to a friendship banquet and killed.

Then in early August 1585, the Tatars laid a trap for Yermak himself. Yermak was told that an unescorted caravan from Bukhara was nearing the Irtysh River, so he hurried to meet it with a company of Cossacks. He found that the report was false, and the men had to bivouac on an island in midstream for the night. There was a wild storm during the night, which drove the watchmen back into their tents.

A party of Tatars disembarked without being seen, and managed to kill nearly all of the Cossacks. Yermak struggled into his armour and fought his way to the embankment, but the boat floated out of his reach. He plunged into the water after it, but sunk beneath the waves due to the weight of his armour.

1,340 Cossacks had started out on the expedition to Siberia, and now only 90 remained. They retreated to the Urals, and as they made their way through a mountain pass, they met 100 Russian streltsy (musketeers) with cannon moving east.

Reconquest

Whatever the Stroganovs intended, Yermak hadn't intended to conquer Siberia, merely to carry out a typical Cossack raid for spoils. He'd probably not intended to hold Isker, just to sack it and withdraw before deep snow & ice prevented him from escaping upstream. But despite this, the way had been shown. The Khanate of Sibir had been dealt an irreversible blow, and it would never be able to pull itself back together. Within two decades of Yermak's death, the “colourless hordes” of Russia (as the natives called them) would have taken much of Western Siberia.

The Livonian War ended with an armistice with Poland and Sweden, which allowed Russia to plan an organized reconquest of the territory Yermak had taken. They used river highways to make their advance easier, and immediately retook Isker and destroyed it.

In 1586, they founded Tyumen to consolidate Russia's position on the Tura River. In 1587, Tobolsk was established where the Tobol and Irtysh Rivers met, about 19km from where Isker had been. Now no tribe could doubt that the Russians were there to stay.

By 1591, they'd extended southwards down to the Barabinsk Steppes. There, they founded Ufa (between Tobolsk and Kazan), to secure a new trans-Urals route for the movement of troops and supplies. For the next decade, Russian outposts continued to be built further and further eastwards.

In 1593, Pelym and Beryozov were founded, in order to control and Khanty and Samoyed population in the north.

The historical town of Pelym is in the modern-day Garinsky District. Beryozov is now Beryozovo.

In 1594, the fort of Tara was founded between the Ishim and Barabinsk steppes. The largest expedition ever sent to found a new Siberian fort was sent – 1,200 cavalry soldiers and 350 foot soldiers, including Tatar auxiliaries, and Polish & Lithuanian POWs.

In 1596, Surgut, Obdorsk and Narym were founded, in order to strengthen Russia's hold.

Obdorsk is now called Salekhard.

Verkhoturye was established in 1598 on the Tura River as a gateway to Siberia.

Verkhoturye is in the middle Ural Mountains.

In 1600, Turinsk was established as an ostrog (a small fort usually made of wood), in place of Yepanchin, which Yermak had razed to the ground.

Verkhoturye, Turinsk and Tyumen are marked with grey rectangles.

Also in 1600, 100 Cossacks sailed down the Ob River in four ships, from Tobolsk to the Arctic Coast. From there, they went north-east towards Taz Bay. They had a shipwreck, and then an ambush by Samoyeds, reducing their party by half. However, they still found a spot near the Taz estuary that was suitable for building the fort of Mangazeya.

By 1600, Russia had a fortified route into Siberia, with Verkhoturye, Turinsk and Tyumen standing guard over it. They had secured the Lower Ob basin (in the north) with Berezov, Obdorsk and Mangazeya. Its middle and upper courses were secured with Surgut, Narym and Ketsk (a fort built a few miles above the Ob in 1602).

The forts were headquarters for the army of occupation, and bases for further expansion. Giles Fletcher, the English ambassador to Russia at the time, wrote: “In Siberia, [the tsar] hath divers castles and garisons...and sendeth many new supplies thither, to plant and to inhabite as he winneth ground.”

In 1604, the major outpost of Tomsk was established, in order to guard the Ob River basin from Central Asian nomads raiding across the borders from the south. Now “the cornerstone of the Russian Asiatic empire had been laid.”

Results of the Conquest

The Stroganovs received more trading privileges, and new grants of land west of the Urals, where their empire of trading posts, mines and mills could grow. But they weren't given any of the lands Yermak had advanced into, and got less out of his conquest than they'd hoped. The government realized what a great opportunity Sibir was, and its reoccupation became a state venture. Blockhouses and forts were built to dominate the rivers and portages (paths where craft or cargo are regularly carried between bodies of water).

Russia chose sites for their outposts that had previously been used by Tatar princelings to wield their own authority, thus helping them with native recognition of their legitimacy. They also exploited local enmities – for example, the local Khanty helped the Russians to subdue the Mansi in the neighbourhood of Pelym. For the most part, the Khanty were consistent allies of the Russians (apart from a considerable uprising of their own in 1595).

However, for the most part the natives were not happy with Russian rule, and the Tatars least of all. Khan Kuchum had escaped south to the steppes before the capture of Qashliq, and continued to harass them for the next 14yrs. The Russians undertook campaigns against him in 1591, 1595 and 1598. Most of Kuchum's followers and family were eventually captured or killed, but he refused to be defeated. He continued to fight a futile rear-guard action, attacking isolated Russian companies and posts.

Kuchum offered to negotiate a just peace at one point, one that would allow his followers to live according to their ancient ways in the Irtysh Valley. Instead, Russia tried to tempt him with money, property, and recognition of his royal rank. In response, Kuchum burned a Russian settlement.

Kuchum died in 1598. He was almost blind by then, and he was kiled by the Nogai assassins whom he had turned to for help.

After Kuchum had died, Moscow took steps to prevent his heirs from trying to take the khanate's throne. His heirs had settled in Russia, where they were indulged as royal exiles, and adopted by the Muscovite elite as their own. Kuchum's daughters were married to young nobles, and the sons were given noble rank. One grandson was given the town of Kasimov on the Oka River (this had long been a showcase for puppet Tatars). Kuchum's nephew Mametkul was recognized as a prince, and became a general in the Russian Army.

Yermak became an important figure in both Russian and Tatar folklore. The Cossacks who fell in the battle for Sibir had their names engraved on a memorial tablet in the cathedral of Tobolsk.

There is a legend that sometime after Yermak's death, a Tatar fisherman dredged his body up from the Irtysh, recognizing him by the double-headed eagle emblazoned on the chainmail hauberk. Upon removing the armour, it was found that Yermak's flesh was uncorrupted, and that blood gushed from his mouth and nose. His body and clothing could work miracles, and mothers & babies were preserved from disease. The natives buried him at the foot of a pine tree by the river, and for many years afterwards the spot was marked by a column of fire.

#book: east of the sun#history#military history#colonialism#geography#christianity#islam#economics#trade#russian conquest of siberia#russo-kazan wars#livonian war#siege of kazan#conquest of the khanate of sibir#battle of chuvash cape#native siberians#tatars#siberian tatars#khanty people#mansi people#russia#siberia#khanate of kazan#khanate of sibir#qashliq#yagidar#ivan the terrible#kuchum#yermak timofeyevich#rape tw

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Οι Σάχηδες του Σιρβάν (Σιρβάν-σαχ) και το Ανάκτορό τους στο Μπακού του Αζερμπαϊτζάν

The Shahs of Shirvan (Shirvanshahs) and their Palace in Baku, Azerbaijan

ΑΝΑΔΗΜΟΣΙΕΥΣΗ ΑΠΟ ΤΟ ΣΗΜΕΡΑ ΑΝΕΝΕΡΓΟ ΜΠΛΟΓΚ “ΟΙ ΡΩΜΙΟΙ ΤΗΣ ΑΝΑΤΟΛΗΣ”

Το κείμενο του κ. Νίκου Μπαϋρακτάρη είχε αρχικά δημοσιευθεί την 2η Σεπτεμβρίου 2019.

Ο κ. Μπαϋρακτάρης αναπαράγει τμήμα διάλεξής μου στο Πεκίνο τον Ιανουάριο του 2018 για τα υπαρκτά και τα ανύπαρκτα έθνη του Καυκάσου, την ιστορική συνέχεια πολιτισμικής παράδοσης, την ιστορική ασυνέχεια ορισμένων διεκδικήσεων, καθώς και την σωστή κινεζική πολιτική στον Καύκασο. Στο σημείο αυτό, η ιστορική συνέχεια της προϊσλαμικής Ατροπατηνής στο ισλαμικό Αζερμπαϊτζάν καθιστά ταυτόχρονα το Αζερμπαϊτζάν "Ιράν" και το Ιράν "περιφέρεια του Αζερμπαϊτζάν".

---------------------

https://greeksoftheorient.wordpress.com/2019/09/02/οι-σάχηδες-του-σιρβάν-σιρβάν-σαχ-και-τ/ ================

Οι Ρωμιοί της Ανατολής – Greeks of the Orient

Ρωμιοσύνη, Ρωμανία, Ανατολική Ρωμαϊκή Αυτοκρατορία

Η περιοχή του Σιρβάν είναι το κέντρο του σημερινού Αζερμπαϊτζάν και ονομαζόταν έτσι από τα προϊσλαμικά χρόνια, όταν ο όλος χώρος του Αζερμπαϊτζάν και του βορειοδυτικού Ιράν ονομαζόταν Αδουρμπαταγάν, λέξη από την οποία προέρχεται η ονομασία του σύγχρονου κράτους και η οποία αποδόθηκε στα αρχαία ελληνικά ��ς Ατροπατηνή.

Το Σιρβάν βρισκόταν στα βόρεια όρια του ιρανικού κράτους και, όταν αυτό βρισκόταν σε κατάσταση παρακμής, αδυναμίας και προβλημάτων, συχνά ντόπιοι Ατροπατηνοί ηγεμόνες σχημάτιζαν μια ανεξάρτητη τοπική αρχή. Συνεπώς, ο τίτλος ‘Σάχηδες του Σιρβάν’ ανάγεται ήδη σε προϊσλαμικά χρόνια και μουσουλμάνοι ιστορικοί μας πληροφορούν ότι ένας ‘Σάχης του Σιρβάν’ προσπάθησε να ανακόψει εκεί τα επελαύνοντα ισλαμικά στρατεύματα τα οποία στα μισά του 7ου αιώνα έφθασαν και εκεί, όταν κατέρρευσε το σασανιδικό Ιράν. Το γιατί είχε το Σιρβάν γίνει ανεξάρτητο βασίλειο σε χρονιές όπως 630 ή 650 μπορούμε να καταλάβουμε πολύ εύκολα.

Οι συνεχείς εξουθενωτικοί πόλεμοι Ρωμανίας και Ιράν (601-628), και η αντεπίθεση του Ηράκλειου με σκοπό να αποσπάσει τον Τίμιο Σταυρό από τον Χοσρόη Β’ και να εκδιώξει τους Ιρανούς από την Αίγυπτο και την Συρο-Παλαιστίνη είχαν ήδη ολότελα εξαντλήσει και τις δύο αυτοκρατορίες πριν εμφανιστούν στον ορίζοντα τα στρατεύματα του Ισλάμ.

Το Ανάκτορο των Σάχηδων του Σιρβάν στο Μπακού

Το Σιρβάν καταλήφθηκε από τα ισλαμικά στρατεύματα (που πολεμούσαν υπό τις διαταγές του Σαλμάν ιμπν Ράμπια αλ Μπαχίλι) και μάλιστα αυτά έφθασαν βορειώτερα στον Καύκασο, αλλά στην τεράστια περιοχή που έλεγχε πρώτα το ομεϋαδικό και μετά το 750 το αβασιδικό χαλιφάτο, από την βορειοδυτική Αφρική μέχρι την Κίνα και την Ινδια, το Σιρβάν ή��αν και πάλι ένα είδος περιθωρίου: δεν ήταν ούτε καν ένα σημαντικό σύνορο επειδή μετά το Σιρβάν δεν υπήρχε ένα μεγάλο αντίπαλο κράτος.

Αντίθετα, αυτό συνέβαινε ήδη σε άλλες περιοχές όπως στην Ανατολία (Ρωμανία), την Κεντρική Ασία (Κίνα), την Κοιλάδα του Ινδού (το κράτος του Χάρσα), και την Αίγυπτο (χριστιανική Νοβατία και Μακουρία).

Έτσι, αφού το Σιρβάν διοικήθηκε από μια σειρά διαδοχικών απεσταλμένων των χαλίφηδων (όπως για παράδειγμα, στα χρόνια του Αβασίδη Χαλίφη Χαρούν αλ Ρασίντ, ο Γιαζίντ ιμπν Μαζιάντ αλ Σαϋμπάνι: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yazid_ibn_Mazyad_al-Shaybani), από τις αρχές του 9ου αιώνα οι απόγονοι του Γιαζίντ ιμπν Μαζιάντ αλ Σαϋμπάνι δημιούργησαν μια τοπική δυναστεία (γνωστή ως Γιαζιντίδες – άσχετοι από τους Γιαζιντί) που ανεγνώριζε την χαλιφατική αρχή της Βαγδάτης.

Ανατολική Μικρά Ασία, Βόρεια Μεσ��ποταμία, ΒΔ Ιράν και Καύκασος από το 1100 στο 1300

Μετά την αρχή της αβασιδικής παρακμής όμως, στο δεύτερο μισό του 9ου αιώνα, ο εγγονός του Γιαζίντ ιμπν Μαζιάντ αλ Σαϋμπάνι διεκήρυξε την ανεξαρτησία του από το χαλιφάτο της Βαγδάτης και έλαβε εκνέου τον ιστορικό τίτλο του Σάχη του Σιρβάν. Ο Χάυθαμ ιμπν Χάλεντ (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Haytham_ibn_Khalid) ήταν λοιπόν ο πρώτος από τους μουσουλμάνους Σάχηδες του Σιρβάν.

Γι’ αυτούς χρησιμοποιούνται σήμερα πολλά ονόματα που μπορεί να μπερδέψουν ένα μη ειδικό: Μαζιαντίδες (Mazyadids), Σαϋμπανίδες (Shaybanids), ή όπως προανέφερα Γιαζιντίδες (Yazidids). Αλλά εύκολα μπορείτε να προσέξετε ότι όλα αυτά αποτελούν απλώς διαφορετικές επιλογές συγχρόνων δυτικών ισλαμολόγων και ιστορικών από τα διάφορα ονόματα του ίδιου προσώπου: του Γιαζίντ ιμπν Μαζιάντ αλ Σαϋμπάνι (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yazid_ibn_Mazyad_al-Shaybani).

Το Ανάκτορο των Σάχηδων του Σιρβάν κτίσθηκε τον 15ο αιώνα όταν οι Σάχηδες του Σιρβάν μετέφεραν την πρωτεύουσά τους από την Σεμάχα (βόρειο Αζερμπαϊτζάν) που είχε καταστραφεί από σεισμούς στο Μπακού. Σχέδιο από: Ismayil Mammad

Αν και αραβικής καταγωγής ως δυναστεία, οι μουσουλμάνοι Σάχηδες του Σιρβάν βρέθηκαν σε ένα κοινωνικό-πολιτισμικό πλαίσιο Αζέρων, Ιρανών και Τουρανών και σταδιακά εξιρανίσθηκαν έντονα κι άρχισαν να παίρνουν ονόματα βασιλέων και ηρώων από το ιρανικό-τουρανικό έπος Σαχναμέ του οποίου η πιο μνημειώδης και πιο θρυλική καταγραφή ήταν αυτή του Φερντοουσί. Έτσι λοιπόν αρχής γενομένης από τον Γιαζίντ Β’ του Σιρβάν (ο οποίος βασίλευσε στην περίοδο 991-1027), οι μουσουλμάνοι Σάχηδες του Σιρβάν είθισται να αποκαλούνται και ως Κασρανίδες (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kasranids), επωνυμία που παραπέμπ��ι σε ιρανικά βασιλικά ονόματα επικού και μυθικού χαρακτήρα. Αλλά πρόκειται για την ίδια πάντοτε δυναστεία.

Διακοσμήσεις με αραβουργήματα

Στην συνέχεια, οι μουσουλμάνοι Σάχηδες του Σιρβάν περιήλθαν διαδοχικά σε καθεστώς υποτέλειας προς τους Σελτζούκους, τους Μπαγκρατίδες της Γεωργίας (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bagrationi_dynasty), τους Τουρανούς Κιπτσάκ (Kipchak) Ελντιγκουζίδες (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eldiguzids), και τους Μογγόλους Τιμουρίδες.

Όμως η σύγκρουσή τους με τον Τουρκμένο Σεΐχη Τζουνέιντ, αρχηγό του τουρκμενικού αιρετικού τάγματος των Σούφι στην περίοδο 1447-1460 (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shaykh_Junayd), και ο θάνατος του εν λόγω σεΐχη στην μάχη του Χατσμάς (αζερ. Xaçmaz – αγγλ. Khachmaz) δημιούργησαν ένα τρομερό προηγούμενο.

Το μυστικό στρατιωτικό τάγμα των Κιζιλμπάσηδων (το οποίο οργανώθηκε ως στρατιωτική υποστήριξη του μυστικιστικού τάγματος των Σούφι από τον γιο του Σεΐχη Τζουνέιντ, Σεΐχη Χαϋντάρ (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shaykh_Haydar), διατήρησε έντονη μνησικακία προς τους Σάχηδες του Σιρβάν, μια σειρά καταστροφικών πολέμων στην ��υρύτερη περιοχή του Καυκάσου επακολούθησε κατά την περίοδο 1460-1488, και τελικά και ο Σεΐχης Χαϋντάρ βρήκε και αυτός οικτρό τέλος μαζί με όλους τους στρατιώτες του στην μάχη του Ταμπασαράν (σήμερα στο Νταγεστάν), όπου αντιμετώπισε συνασπισμένους τους Σάχηδες του Σιρβάν και τους Ακκουγιουλού (Τουρκμένους Ασπροπροβατάδες).

Και τελικά το 1500-1501, ο εγγονός του Σεΐχη Τζουνέιντ και γιος του Σεΐχη Χαϋντάρ, Ισμαήλ, επήρε εκδίκηση καταλαμβάνοντας το Σιρβάν και σκοτώνοντας τον Φαρούχ Γιασάρ, τελευταίο Σάχη του Σιρβάν, και την φρουρά του. Επακολούθησε μια βίαιη επιβολή σιιτικών δογμάτων στον τοπικό πληθυσμό και μια απίστευτη τυραννία ως εκδίκηση για την στάση των Σάχηδων του Σιρβάν εναντίον των Σιιτών, των Σούφι και των Κιζιλμπάσηδων. Ο Ισμαήλ Α’ ανέτρεψε και το κράτος των Ακκουγιουλού ιδρύοντας την σαφεβιδική (σουφική) δυναστεία του Ιράν.

Η μάχη του Σάχη Ισμαήλ Α’ με τον Φαρούχ Γιασάρ, τελευταίο Σάχη του Σιρβάν από σμικρογραφία ιρανικού σαφεβιδικού χειρογράφου (1501)

Μόνον η νίκη του Σουλτάνου Σελίμ Α’ το 1514 στο Τσαλντιράν εμπόδισε το κιζιλμπάσικο τσουνάμι να καταλάβει όλη την επικράτεια του Ισλάμ.

Η δυναστεία των Σάχηδων του Σιρβάν μετά από 640 χρόνια πήρε έτσι ένα τέλος, αλλά έμειναν κορυφαίες δημιουργίες στον τομέα της ισλαμικής τέχνης και αρχιτεκτονικής να μας θυμίζουν την προσφορά της.

Μερικοί από τους μεγαλύτερους επικούς ποιητές, πανσόφους επιστήμονες, και σημαντικώτερους μυστικιστές των ισλαμικών χρόνων, ο Νεζαμί Γκαντζεβί, ο Αφζαλεντίν Χακανί (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Khaqani) και ο Τζαμάλ Χαλίλ Σιρβανί (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nozhat_al-Majales) έζησαν στο Σιρβάν και οι απαγγελίες τους ακούστηκαν στο ανάκτορο των Σάχηδων του Σιρβάν.

Όμως το τέλος της δυναστείας του Σιρβάν άφησε μέχρι τις μέρες μας μια βραδυφλεγή βόμβα, πολύ καλά κρυμμένη, που κανένας δεν ξέρει σε ποιο βαθμό μας απειλεί όλους ακόμη και σήμερα με ένα απίστευτο αιματοκύλισμα.

Πολλοί προσπάθησαν σε διαφορετικές στιγμές να απενεργοποιήσουνν αυτή την βόμβα και να εξαφανίσουν την απειλή. Ωστόσο και αυτοί στην προσπάθειά τους έχυσαν πολύ αίμα που ακόμη και σήμερα παίζει ένα σημαντικό ρόλο. Η καλά κρυμμένη αυτή απειλή κι ανθρώπινη βόμβα έχει ένα όνομα που θα έπρεπε να κάνει την Ανθρωπότητα να τρέμει:

– Κιζιλμπάσηδες!

Αυτοί είναι οι κυρίαρχοι της αέναης υπομονής και της ατέρμονος προσμονής. Και αν και υπάρχουν πολλές ενδείξεις για τις δραστηριότητές τους, κανένας δεν μπορεί σήμερα να πει αν όντως υπάρχουν και αν διατηρούν την δύναμη που φημίζονταν να έχουν. Για το θέμα μπορούμε να βρούμε μόνον νύξεις κι υπαινιγμούς.

Σ’ αυτό ωστόσο θα επανέλθω. Στην συνέχεια μπορείτε να δείτε ένα βίντεο-ξενάγηση στο Ανάκτορο των Σάχηδων του Σιρβάν και να διαβάσετε σχετικά με τα εκεί μνημεία, την πόλη και την δυναστεία που αποτελεί την ραχοκοκκαλιά της Ισλαμικής Ιστορίας του Αζερμπαϊτζάν. Επιπλέον συνδέσμους θα βρείτε στο τέλος.

Δείτε το βίντεο:

Дворец ширваншахов – Shirvanshahs Palace, Baku – Ανάκτορο των Σάχηδων του Σιρβάν

https://www.ok.ru/video/1495285893741

Περισσότερα:

Дворец ширваншахов (азерб. Şirvanşahlar sarayı) — бывшая резиденция ширваншахов (правителей Ширвана), расположенная в столице Азербайджана, городе Баку.

Образует комплекс, куда помимо самого дворца также входят дворик Диван-хане, усыпальница ширваншахов, дворцовая мечеть 1441 года с минаретом, баня и мавзолей придворного учёного Сейида Яхья Бакуви. Дворцовый комплекс был построен в период с XIII[3] по XVI век (некоторые здания, как и сам дворец, были построены в начале XV века при ширваншахе Халил-улле I). Постройка дворца была связана с переносом столицы государства Ширваншахов из Шемахи в Баку.

Несмотря на то, что основные постройки ансамбля строились разновременно, дворцовый комплекс производит целостное художественное впечатление. Строители ансамбля опирались на вековые традиции ширвано-апшеронской архитектурной школы. Создав чёткие кубические и многогранные архитектурные объёмы, они украсили стены богатейшим резным узором, что свидетельствует о том, что создатели дворца прекрасно владели мастерством каменной кладки. Каждый из зодчих благодаря традиции и художественному вкусу воспринял архитектурный замысел своего предшественника, творчески развил и обогатил его. Разновременные постройки связаны как единством масштабов, так и ритмом и соразмерностью основных архитектурных форм — кубических объёмов зданий, куполов, порталов.

В 1964 году дворцовый комплекс был объявлен музеем-заповедником и взят под охрану государства. В 2000 году уникальный архитектурный и культурный ансамбль, наряду с обнесённой крепостными стенами исторической частью города и Девичьей башней, был включён в список Всемирного наследия ЮНЕСКО. Дворец Ширваншахов и сегодня считается одной из жемчужин архитектуры Азербайджана.

Δείτε το βίντεο:

Palace of the Shirvanshahs – Şirvanşahlar Sarayı – Дворец ширваншахов

https://vk.com/video434648441_456240287

Περισσότερα:

The Palace of the Shirvanshahs (Azerbaijani: Şirvanşahlar Sarayı, Persian: کاخ شروانشاهان) is a 15th-century palace built by the Shirvanshahs and described by UNESCO as “one of the pearls of Azerbaijan’s architecture”. It is located in the Inner City of Baku, Azerbaijan and, together with the Maiden Tower, forms an ensemble of historic monuments inscribed under the UNESCO World Heritage List of Historical Monuments. The complex contains the main building of the palace, Divanhane, the burial-vaults, the shah’s mosque with a minaret, Seyid Yahya Bakuvi’s mausoleum (the so-called “mausoleum of the dervish”), south of the palace, a portal in the east, Murad’s gate, a reservoir and the remnants of a bath house. Earlier, there was an ancient mosque, next to the mausoleum. There are still ruins of the bath and the lamb, belong to the west of the tomb.

In the past, the palace was surrounded by a wall with towers and, thus, served as the inner stronghold of the Baku fortress. Despite the fact that at the present time no traces of this wall have survived on the surface, as early as the 1920s, the remains of apparently the foundations of the tower and the part of the wall connected with it could be distinguished in the north-eastern side of the palace.

There are no inscriptions survived on the palace itself. Therefore, the time of its construction is determined by the dates in the inscriptions on the architectural monuments, which refer to the complex of the palace. Such two inscriptions were completely preserved only on the tomb and minaret of the Shah’s mosque. There is a name of the ruler who ordered to establish these buildings in both inscriptions is the – Shirvan Khalil I (years of rule 1417–1462). As time of construction – 839 (1435/36) was marked on the tomb, 845 (1441/42) on the minaret of the Shah’s mosque.

The burial vault, the palace and the mosque are built of the same material, the grating and masonry of the stone are the same.

The plan of the palace

The Palace

Divan-khana

Seyid Mausoleum Yahya Bakuvi

The place of the destroyed Kei-Kubad mosque

The Eastern portal

The Palace Mosque

The Shrine

Place of bath

Ovdan

Δείτε το βίντεο:

Το Ανάκτορο των Σάχηδων του Σιρβάν (Σιρβάν-σαχ), Μπακού – Αζερμπαϊτζάν

Περισσότερα:

Τα ανάκτορα των Σιρβανσάχ (αζερικά: Şirvanşahlar Sarayı) είναι ανάκτορο κατασκευασμένο στο Μπακού, Αζερμπαϊτζάν, τον 13ο έως 16ο αιώνα.

Το ανάκτορο κατασκευάστηκε από τη δυναστεία των Σιρβανσάχ κατά τη διάρκεια της βασιλείας του Χαλίλ-Ουλλάχ, όταν η πρωτεύουσα μετακινήθηκε από τη Σαμάχι στο Μπακού.

Το ανάκτορο αποτελεί αρχιτεκτονικά συγκρότημα με το περίπτερο Ντιβανχανά, το ιερό των Σιρβανσάχ, το τζαμί του παλατιού, χτισμένο το 1441, μαζί με το μιναρέ του, τα λουτρά και το μαυσωλείο.

Το 1964, το ανάκτορο ανακηρύχθηκε μουσείο-μνημείο και τέθηκε υπό κρατική προστασία.

Το 2000 ανακηρύχθηκε μνημείο παγκόσμιας κληρονομιάς από τη UNESCO μαζί με την παλιά πόλη του Μπακού και τον Παρθένο Πύργο.

Παρά το γεγονός ότι το συγκρότημα κατασκευάστηκε σε διαφορετικές χρονικές περιόδους, το συγκρότημα δίνει ομοιόμορφη εντύπωση, βασισμένη στην αρχιτεκτονικό σχολή του Σιρβάν-Αμπσερόν.

Με τη δημιουργία κυβικών και με πολλές προσόψεις αρχιτεκτονικών όγκων, οι τοίχοι είναι διακοσμημένοι με ανάγλυφα μοτίβα.

Κάθε αρχιτέκτονας, εξαιτίας των παραδόσεων και της αισθητικής που χρησιμοποιήθηκε από τους προκατόχους του, τον ανέπτυξε και τον εμπλούτισε δημιουργικά, με αποτέλεσμα τα επιμέρους κτίσματα να έχουν δημιουργούν την αίσθηση της ενότητας, ρυθμού και αναλογίας των βασικών αρχιτεκτονικών μορφών, δηλαδή του κυβικού όγκου των κτιρίων, των θόλων και των πυλών.

Με την κατάκτηση του Μπακού από τους Σαφαβίδες το 1501, το παλάτι λεηλατήθηκε.

Όλοι οι θησαυροί των Σιρβανσάχ, όπλα, πανοπλίες, κοσμήματα, χαλιά, μπροκάρ, σπάνια βιβλία από τη βιβλιοθήκης του παλατιού, πιάτα από ασήμι και χρυσό, μεταφέρθηκαν από τους Σαφαβίδες στη Ταμπρί��.

Αλλά μετά την μάχη του Τσαλντιράν το 1514 μεταξύ του στρατού του σουλτάνου της Οθωμανικής Αυτοκρατορίας Σελίμ Α΄ και τους Σαφαβίδες, η οποία έληξε με ήττα των δεύτερων, οι Τούρκοι πήραν τον θησαυρό των Σιρβανσάχ ως λάφυρα.

Σήμερα βρίσκονται στις συλλογές μουσείων της Τουρκίας, του Ιράν, της Βρετανίας, της Γαλλίας, της Ρωσίας, της Ουγγαρίας.

Μερικά χαλιά του ανακτόρου φυλάσσονται στο μουσείο Βικτώριας και Αλβέρτου του Λονδίνου και τα αρχαία βιβλία φυλάσσονται σε αποθετήρια βιβλίων στην Τεχεράνη, το Βατικανό και την Αγία Πετρούπολη.

========================

Διαβάστε:

The Shirvanshah Palace

The Splendor of the Middle Ages

No tour of Baku’s Ichari Shahar (Inner City) would be complete without a stop at the 15th-century Shirvanshah complex. The Shirvanshahs ruled the state of Shirvan in northern Azerbaijan from the 6th to the 16th centuries. Their attention first shifted to Baku in the 12th century, when Shirvanshah Manuchehr III ordered that the city be surrounded with walls. In 1191, after a devastating earthquake destroyed the capital city of Shamakhi, the residence of the Shirvanshahs was moved to Baku, and the foundation of the Shirvanshah complex was laid. This complex, built on the highest point of Ichari Shahar, remains as one of the most striking monuments of medieval Azerbaijani architecture.

Το Ντιβάν-χανέ

Much of the construction was done in the 15th century, during the reign of Khalilullah I and his son Farrukh Yassar in 1435-1442.

An Egyptian historian named as-Suyuti described the father in superlative terms: “He was the most honored among rulers, the most pious, worthy and just. He was the last of the great Muslim rulers. He ruled the Shirvan and Shamakhi kingdoms for 50 years. He died in 1465, when he was about 100 years old, but he had good eyes and excellent health.”

The buildings that belong to the complex include what may have been living quarters, a mosque, the octagonal-shaped Divankhana (Royal Assembly), a tomb for royal family members, the mausoleum of Seyid Yahya Bakuvi (a famous astronomer of the time) and a bathhouse.

All of these buildings except for the living premises and bathhouse are fairly well preserved. The Shirvanshah complex itself is currently under reconstruction. It has 27 rooms on the first floor and 25 on the second.

Like so many other old buildings in Baku, the real function of the Shirvanshah complex is still under investigation. Though commonly described as a palace, some experts question this. The complex simply doesn’t have the royal grandeur and huge spaces normally associated with a palace; for instance, there are no grand entrances for receiving guests or huge royal bedrooms. Most of the rooms seem more suitable for small offices or monks’ living quarters.

Divankhana

This unique building, located on the upper level of the grounds, takes on the shape of an octagonal pavilion. The filigree portal entrance is elaborately worked in limestone.

The central inscription with the date of the Assembly’s construction and the name of the architect may have been removed after Shah Ismayil Khatai (famous king from Southern Azerbaijan) conquered Baku in 1501.

However, there are two very interesting hexagonal medallions on either side of the entrance. Each consists of six rhombuses with very unusual patterns carved in stone. Each elaborate design includes the fundamental tenets of the Shiite faith: “There is no other God but God. Mohammad is his prophet. Ali is the head of the believers.” In several rhombuses, the word “Allah” (God) is hewn in reverse so that it can be read in a mirror. It seems looking-glass reflection carvings were quite common in the Oriental world at that time.

Scholars believe that the Divankhana was a mausoleum meant for, or perhaps even used for, Khalilullah I. Its rotunda resembles those found in the mausoleums of Bayandur and Mama-Khatun in Turkey. Also, the small room that precedes the main octagonal hall is a common feature in mausoleums of Shirvan.

The Royal Tomb

This building is located in the lower level of the grounds and is known as the Turba (burial vault). An inscription dates the vault to 1435-1436 and says that Khalilullah I built it for his mother Bika khanim and his son Farrukh Yamin. His mother died in 1435 and his son died in 1442, at the age of seven. Ten more tombs were discovered later on; these may have belonged to other members of the Shah’s family, including two more sons who died during his own lifetime.

The entrance to the tomb is decorated with stalactite carvings in limestone. One of the most interesting features of this portal is the two drop-shaped medallions on either side of the Koranic inscription. At first, they seem to be only decorative.

The Turba is one of the few areas in the Shirvanshah complex where we actually know the name of the architect who built the structure. In the portal of the burial vault, the name “Me’mar (architect) Ali” is carved into the design, but in reverse, as if reflected in a mirror.

Some scholars suggest that if the Shah had discovered that his architect inscribed his own name in a higher position than the Shah’s, he would have been severely punished. The mirror effect was introduced so that he could leave his name for posterity.

Remnants of History

Another important section of the grounds is the mosque. According to complicated inscriptions on its minaret, Khalilullah I ordered its construction in 1441. This minaret is 22 meters in height (approximately 66 feet). Key Gubad Mosque, which is just a few meters outside the complex, was built in the 13th century. It was destroyed in 1918 in a fire; only the bases of its walls and columns remain. Nearby is the 15th-century Mausoleum, which is said to be the burial place of court astronomer Seyid Yahya Bakuvi.

Murad’s Gate was a later addition to the complex. An inscription on the gate tells that it was built by a Baku citizen named Baba Rajab during the rule of Turkish sultan Murad III in 1586. It apparently served as a gateway to a building, but it is not known what kind of building it was or even if it ever existed.

In the 19th century, the complex was used as an arms depot. Walls were added around its perimeter, with narrow slits hewn out of the rock so that weapons could be fired from them. These anachronistic details don’t bear much connection to the Shirvanshahs, but they do hint at how the buildings have managed to survive the political vicissitudes brought on by history.

Visitors to the Shirvanshah complex can also see some of the carved stones from the friezes that were brought up from the ruined Sabayil fortress that lies submerged underwater off Baku’s shore. The stones, which now rest in the courtyard, have carved writing that records the genealogy of the Shirvanshahs.

The complex was designated as a historical site in 1920, and reconstruction has continued off and on ever since that time. According to Sevda Dadashova, Director, restoration is currently progressing, though much slower than desired because of a lack of funding.

https://www.azer.com/aiweb/categories/magazine/82_folder/82_articles/82_shirvanshah.html

========================

The Palace of the Shirvanshahs

by Kamil Ibrahimov

Baku’s Old City is a treasure trove of Azerbaijani history. Its stone buildings and mazy streets hold secrets that have still to be discovered. A masterpiece of Old City architecture, rich in history but with questions still unanswered, is the medieval residence of the rulers of Shirvan, the Shirvanshahs´ Palace.

The State of Shirvan

The state of Shirvan was formed in 861 and became the longest-surviving state in northern Azerbaijan. The first dynasty of the state of Shirvan was the Mazyadi dynasty (861-1027), founded by Mahammad ibn Yezid, an Arab vicegerent who lived in Shamakhi.

In the 10th century, the Shirvanshahs took Derbent, now in the Russian Federation. Under the Mazyadis, the state of the Shirvanshahs stretched from Derbent to the Kur River. The capital of this state was the town of Shamakhi.

In the first half of the 11th century, the Mazyadi dynasty was replaced by the Kasrani dynasty (1028-1382). The state of Shirvan flourished under the Shirvanshahs, Manuchehr III and his son Akhsitan. The last ruler in this dynasty was Hushang. His reign was unpopular and Hushang was killed in a rebellion.

The Kasrani dynasty was later replaced by the Derbendi dynasty (1382-1538), founded by Ibrahim I (1382-1417). Ibrahim I was a well-known but bankrupt feudal ruler from Shaki. His ancestors had been rulers in Derbent, hence the dynasty´s name. Ibrahim was a wise and peace-loving ruler and for some time managed to protect Shirvan from invasion.

To prevent the country´s destruction by Timur (Tamerlane), Ibrahim I took gifts to Timur´s headquarters and obtained internal independence for Shirvan. Ibrahim I failed to unite all Azerbaijani lands under his rule, but he did manage to make Shirvan a strong and independent state.

Baku becomes capital of Shirvan

The 15th century was a period of economic and cultural revival for Shirvan. Since this was a time of peace in Shirvan, major progress was made in the arts, architecture and trade. Shamakhi remained the capital of Shirvan at the start of the century, but an earthquake and constant attacks by the Kipchaks, a Turkic people, led the capital to be moved to Baku.

The city of Baku was the capital of the country during the rule of the Shirvanshahs Khalilullah I (1417-62) and his son Farrukh Yasar (1462-1500).

While tension continued in Shamakhi, Baku developed in a relatively quiet environment. It is known that strong fortress walls were built in Baku as early as the 12th century. After the capital was moved to Baku, the Palace of the Shirvanshahs was erected at the highest point of the city, in what had been one of the most densely populated areas. The palace complex consists of nine buildings – the palace itself, the Courtroom, the Dervish´s Tomb, the Eastern Gate, the Shah Mosque, the Keygubad Mosque, the palace tomb, the bathhouse and the reservoir.

The buildings of the complex are located in three courtyards that are on different levels, 5.6 metres above one another. Since the palace is built on uneven ground, it does not have an orderly architectural plan. The entire complex is constructed from limestone. Of all the buildings, the palace itself has suffered the most wear and tear over the years. The palace was looted in 1500 after Farrukh Yasar was killed in fighting between the Shirvanshahs and the Safavids. As the Iranian and Ottoman empires vied for power in the South Caucasus, the state of Shirvan, on the crossing-point of various caravan routes, suffered frequent attacks. Consequently, the palace was badly damaged many times. Proof of this is the Murad Gate which was built during Ottoman rule.

What is now Azerbaijan was occupied by Russia on 10 February 1828. The Shirvanshahs´ Palace became the Russian military headquarters and many palace buildings were destroyed. In 1954, the Complex of the Palace of the Shirvanshahs was made a State Historic-Architectural Reserve and Museum. In 1960, the authorities of the Soviet republic decided to promote the palace as an architectural monument.

The Palace Building

The palace is a two-storey building in an irregular, rectangular shape. In order to provide better illumination of the palace, the south-eastern part of the building was constructed on different levels. Initially there were 52 rooms in the palace, of which 27 were on the ground floor and 25 on the first floor. The shah and his family lived on the upper floor, while servants and others lived on the lower floor.

The Tomb Built by Shirvanshah Farrukh Yasar (also known as the Courtroom or Divankhana)

Shirvanshah Farrukh Yasar had the tomb constructed in the upper courtyard of the palace complex. Its north side and one of its corners adjoin the residential building. The tomb consists of an octagonal rotunda, completed with a dodecagonal dome. Its octagonal hall is surrounded by an open balcony or portico. The balcony is edged with nine columns which still have their original capitals. The rotunda stands in a small courtyard which also has an open balcony running around its edge. The balcony´s columns and arches are the same shape as those of the rotunda. The outer side of the columns has a stone with the image of a dove, the symbol of freedom, and two stone chutes to drain water away. Some researchers believe that this building was used for official receptions and trials and call it the Courtroom. The architectural work in the tomb was not completed. The tomb is considered one of the finest examples of medieval architecture, not only in Azerbaijan but in the whole Middle East.

The Dervish´s Tomb

The Dervish´s Tomb is located in the southern part of the middle courtyard. Some historians maintain that it is the tomb of Seyid Yahya Bakuvi, who was a royal scholar and astronomer under Khalilullah I.

Other historians say that all the buildings in the lower courtyard of the palace, including the Dervish´s Tomb, are part of a complex where dervishes lived, but there is little evidence for this.

The Keygubad Mosque

Now in ruins, the Keygubad Mosque was a mosque-cum-madrasah joined to the Dervish´s Tomb.

The tomb was located in the southern part of the mosque.

The mosque consisted of a rectangular prayer hall and a small corridor in front of it. In the centre of the hall four columns supported the dome.

Historian Abbasgulu Bakikhanov wrote that Bakuvi taught and prayed in the mosque: “The cell where he prayed, the school where he worked and his grave are there, in the mosque”.

Keygubad Shirvanshah ruled from 1317 to 1343 and was Sheikh Ibrahim´s grandfather.

The Eastern Gate

The Eastern or Murad Gate is the only part of the complex that dates to the 16th century. Two medallions on the upper frame of the Murad Gate bear the inscription: “This building was constructed under the great and just Sultan Murad III on the basis of an order by Racab Bakuvi in 994” (1585-86).

The Tomb of the Shirvanshahs

There are two buildings in the lower courtyard – the tomb and the Shah Mosque. A round wall encloses the lower courtyard, separating it from the other yards. When you look at the tomb from above, you can see that it is rectangular in shape, decorated with an engraved star and completed with an octagonal dome. While the tomb was being built, blue glazed tiles were placed in the star-shaped mortises on the dome.

An inscription at the entrance says: “Protector of the religion, man of the prophet, the great Sultan Shirvanshah Khalilullah, may God make his reign as shah permanent, ordered the building of this light tomb for his mother and seven-year-old son (may they rest in peace) 839” (1435-36). The architect´s name is also inscribed between the words “God” and “Mohammad” on another decorative inscription on the portal which can be read only using a mirror. The inscription says “God, architect Ali, Mohammad”.

A skeleton 2.1 metres tall was found opposite the entrance to the tomb. This is believed to be Khalilullah I´s own grave. A comb, a gold earring and other items of archaeological interest were found there.

The Shah Mosque

The Shah Mosque is in the lower courtyard, alongside the mausoleum. The mosque is 22 metres high. An inscription around the minaret says: “The Great Sultan Khalilullah I ordered the erection of this minaret. May God prolong his rule as Shah. Year 845” (1441-42).

Stairs lead from a hollow in the wall behind the minbar or pulpit to another small room. Stone traceries on the windows decorate the mosque.

The Palace Bathhouse

The palace bathhouse is located in the lowest courtyard of the complex. Like all bathhouses in the Old City, this one was built underground to ensure that the temperature inside was kept stable. As time passed the level of the earth rose and covered it completely. The bathhouse was found by chance in 1939. In 1953 part of it was cleaned and in 1961 restoration work was done and the dome repaired. The walls in one of the side rooms are covered with glazed tiles and this room is thought to have been the shah´s room.

Cistern

The cistern, part of an underground water distribution system, was constructed in the lower part of the bathhouse to supply the Shirvanshahs´ Palace with water. Water came into the cistern via ceramic pipes which were part of the Shah´s Water Pipeline, laid from a high part of the city. The cistern is located underground and its entrance has the shape of a portal. Numerous stairs lead from the entrance down to the storage facility. A link between the cistern and the bathhouse can be seen from the side lobby. The cistern was found by chance during restoration work in 1954.

Literature

S.B. Ashurbayli: Государство Ширваншахов (The State of the Shirvanshahs), Baku, Elm, 1983; and Bakı şəhərinin tarixi (The History of the City of Baku), Baku, Azarnashr, 1998

F.A. Ibrahimov and K.F. Ibrahimov: Bakı İçərişəhər (Baku Inner City), Baku, OKA, Ofset, 2002. Kamil Farhadoghlu: Bakı İçərişəhər (Baku Inner City), Sh-Q, 2006; and Baku´s Secrets are Revealed (Bakının sirləri açılır), Baku, 2008

E.A. Pakhomov: Отчет о работах по шахскому дворцу в Баку (Report on Work in the Shah´s Palace in Baku), News of the AAK, Issue II, Baku, 1926; and Первоначальная очистка шахского дворца в Баку (Initial Clearing of the Shah´s Palace in Baku), News of the AAK, Issue II, Baku, 1926

Chingiz Gajar: Старый Баку (Old Baku), OKA, Ofset, 2007

M. Huseynov, L. Bretanitsky, A. Salamzadeh, История архитектуры Азербайджана (History of the Architecture of Azerbaijan). Moscow, 1963

M.S. Neymat, Корпус эпиграфических памятников Азербайджана (Azerbaijan´s Epigraphic Monuments), Baku, Elm, 1991

A.A. Alasgarzadah, Надписи архитектурных памятников Азербайджана эпохи Низами (Inscriptions on the architectural monuments of Azerbaijan from the era of Nizami) in the collection, Архитектура Азербайджана эпохи Низами (Azerbaijan in the Era of Nizami), Moscow, 1947.

http://www.visions.az/en/news/159/cdc770e3/

=============================

Šervānšāhs

Šervānšāhs (Šarvānšāhs), the various lines of rulers, originally Arab in ethnos but speedily Persianized within their culturally Persian environment, who ruled in the eastern Caucasian region of Šervān from mid-ʿAbbasid times until the age of the Safavids.

The title itself probably dates back to pre-Islamic times, since Ebn Ḵordāḏbeh, (pp. 17-18) mentions the Shah as one of the local rulers given his title by the Sasanid founder Ardašir I, son of Pāpak. Balāḏori (Fotuḥ, pp. 196, 203-04) records that the first Arab raiders into the eastern Caucasus in ʿOṯmān’s caliphate encountered, amongst local potentates, the shahs of Šarvān and Layzān, these rulers submitting at this time to the commander Salmān b. Rabiʿa Bāheli.

The caliph Manṣur’s governor of Azerbaijan and northwestern Persia, Yazid b. Osayd Solami, took possession of the naphtha wells (naffāṭa) and salt pans (mallāḥāt) of eastern Šervān; the naphtha workings must mark the beginnings of what has become in modern times the vast Baku oilfield.

By the end of this 8th century, Šervān came within the extensive governorship, comprising Azerbaijan, Arrān, Armenia and the eastern Caucasus, granted by Hārun-al-Rašid in 183/799 to the Arab commander Yazid b. Mazyad, and this marks the beginning of the line of Yazidi Šervānšāhs which was to endure until Timurid times and the end of the 14th century (see Bosworth, 1996, pp. 140-42 n. 67).

Most of what we know about the earlier centuries of their power derives from a lost Arabic Taʾriḵ Bāb al-abwāb preserved within an Arabic general history, the Jāmeʿ al-dowal, written by the 17th century Ottoman historian Monajjem-bāši, who states that the history went up to c. 500/1106 (Minorsky 1958, p. 41). It was exhaustively studied, translated and explained by V. Minorsky (Minorsky, 1958; Ḥodud al-ʿālam, commentary pp. 403-11); without this, the history of this peripheral part of the mediaeval Islamic world would be even darker than it is.

The history of Šervānšāhs was clearly closely bound up with that of another Arab military family, the Hāšemis of Bāb al-abwāb/Darband (see on them Bosworth, 1996, pp. 143-44 n. 68), with the Šervānšāhs at times ruling in the latter town (at times invited into Darband by rebellious elements there, see Minorsky 1958, pp. 27, 29-30), and there was frequent intermarriage between the two families.

By the later 10th century, the Shahs had expanded from their capital of Šammāḵiya/Yazidiya to north of the Kura valley and had absorbed the petty principalities of Layzān and Ḵorsān, taking over the titles of their rulers (see Ḥodud al-ʿālam, tr. Minorsky, pp. 144-45, comm. pp. 403-11), and from the time of Yazid b. Aḥmad (r. 381-418/991-1028) we have a fairly complete set of coins issued by the Shahs (see Kouymjian, pp. 136-242; Bosworth, 1996, pp. 140-41).

Just as an originally Arab family like the Rawwādids in Azerbaijan became Kurdicized from their Kurdish milieu, so the Šervānšāhs clearly became gradually Persianized, probably helped by intermarriage with the local families of eastern Transcaucasia; from the time of Manučehr b. Yazid (r. 418-25/1028-34), their names became almost entirely Persian rather than Arabic, with favored names from the heroic national Iranian past and with claims made to descent from such figures as Bahrām Gur (see Bosworth, 1996, pp. 140-41).

The anonymous local history details frequent warfare of the Shahs with the infidel peoples of the central Caucasus, such as the Alans, and the people of Sarir (i.e. Daghestan), and with the Christian Georgians and Abḵāz to their west. In 421/1030 Rus from the Caspian landed near Baku, defeated in battle the Shah Manučehr b. Yazid and penetrated into Arrān, sacking Baylaqān before departing for Rum, i.e. the Byzantine lands (Minorsky, 1958, pp. 31-32). Soon afterwards, eastern Transcaucasia became exposed to raids through northern Persia of the Turkish Oghuz. Already in c. 437/1045, the Shah Qobāḏ b. Yazid had to built a strong stone wall, with iron gates, round his capital Yazidiya for fear of the Oghuz (Minorsky 1958, p. 33). In 458-59/1066-67 the Turkish commander Qarategin twice invaded Šervān, attacking Yazidiya and Baku and devastating the countryside.

Then after his Georgian campaign of 460/1058 Alp Arslan himself was in nearby Arrān, and the Shah Fariborz b. Sallār had to submit to the Saljuq sultan and pay a large annual tribute of 70,000 dinars, eventually reduced to 40,000 dinars; coins issued soon after this by Fariborz acknowledge the ʿAbbasid caliph and then Sultan Malekšāh as his suzerain (Minorsky 1958, pp. 35-38, 68; Kouymjian, pp. 146ff, who surmises that, since we have no evidence for the minting of gold coins in Azerbaijan and the Caucasus at this time, Fariborz must have paid the tribute in Byzantine or Saljuq coins).

Fariborz’s diplomatic and military skills thus preserved much of his family’s power, but after his death in c. 487/1094 there seem to have been succession disputes and uncertainty (the information of the Taʾriḵ Bāb al-abwāb dries up after Fariborz’s death).

In the time of the Saljuq sultan Maḥmud b. Moḥammad (r. 511-25/1118-31), Šervān was again occupied by Saljuq troops, and the disturbed situation there encouraged invasions of Šammāḵa and Darband by the Georgians. During the middle years of the 12th century, Šervān was virtually a protectorate of Christian Georgia. There were marriage alliances between the Shahs and the Bagratid monarchs, who at times even assumed the title of Šervānšāh for themselves; and the regions of Šakki, Qabala and Muqān came for a time directly under Georgian rule (Nasawi, text, pp. 146, 174). The energies of the Yazidi Shahs had to be directed eastwards towards the Caspian, and on various occasions they expanded as far as Darband.

The names and the genealogical connections of the later Šervānšāhs now become very confused and uncertain, and Monajjem-bāši gives only a skeletal list of them from Manučehr (III) b. Faridun (I) onwards. He calls this Shah Manučehr b. Kasrān, and the names Kasrānids or Ḵāqānids appear in some sources for the later shahs of the Yazidi line in Šervān (Minorsky, 1958, pp. 129-38; Bosworth, 1996, pp. 140-41). Manučehr (III) not only called himself Šervānšāh but also Ḵāqān-e Kabir “Great Khan,” and it was from this that the poet Ḵāqāni, a native of Šervān and in his early years eulogist of Manučehr, derived his taḵalloṣ or nom-de-plume. Much of the line of succession of the Shahs at this time has to be reconstructed from coins, and from these the Shahs of the 12th century appear as Saljuq vassals right up to the time of the last Sultan, Ṭoḡrïl (III) b. Arslān, after which the name of the caliphs alone appear on their coins (Kouymjian, pp. 153ff, 238-42).

In the 13th century, Šervān fell under the control first of the Khwarazmshah Jalāl-al-Din Mengüberti after the latter appeared in Azerbaijan; according to Nasawi (p. 75), in 622/1225 Jalāl-al-Din demanded as tribute from the Šervānšāh Garšāsp (I) b. Farroḵzād (I) (r. after 600/1204 to c. 622/1225) the 70,000 dinars (100,000 dinars?) that the Saljuq sultan Malekšāh had exacted a century or more previously (see Kouymjian, pp. 152-53). Shortly afterwards, Šervān was taken over by the Mongols, and at times came within the lands of the Il-Khanids and at others within the lands of the Golden Horde.

At the outset, coins were minted there in the name of the Mongol Great Khans, with the names of the Kasrānid Shahs but without their title of Šervānšāh, but then under the Il-Khanids, no coins were struck in Šervān. The Kasrānids survived as tributaries of the Mongols, and the names of Shahs are fragmentarily known up to that of Hušang b. Kayqobāḏ (r. in the 780s/1370s; see Bosworth, 1996, p. 141; Barthold and Bosworth, 1997, p. 489).

This marked the end of the Yazidi/Kasrānid Shahs, but after their disappearance there came to power in Šervān a remote connection of theirs, Ebrāhim b. Moḥammad of Darband (780-821/1378-1418). He founded a second line of Shahs, at first as a tributary of Timur but latterly as an independent ruler, and his family was to endure for over two centuries.

The 15th century was one of peace and prosperity for Šervān, with many fine buildings erected in Šammāḵa/Šemāḵa and Baku (see Blair, pp. 155-57), but later in the century the Shahs’ rule was threatened by the rise of the expanding and aggressive shaikhs of the Ṣafavi order; both Shaikh Jonayd b. Ebrāhim and his son Ḥaydar were killed in attempted invasions of Šervān and the Darband region (864/1460 and 893/1488 respectively).

Once established in power in Persia, Shah Esmāʿil I avenged these deaths by an invasion of Šervān in 906/1500, in which he killed the Šervānšāh Farroḵ-siār b. Ḵalil (r. 867-905/1463-1500), then reducing the region to dependent status (see Roemer, pp. 211-12).

The Shahs remained as tributaries, and continued to mint their own coins, until in 945/1538 Ṭahmāsp I’s troops invaded Šervān, toppled Šāhroḵ b. Farroḵ, and made the region a mere governorship of the Safavid empire.

In the latter half of the 16th century, descendants of the last Shahs endeavored, with Ottoman Turkish help, to re-establish their power there, and in the peace treaty signed at Istanbul in 998/1590 between the sultan Morād III and Shah ʿAbbās I, Šervān was ceded to the Ottomans; but after 1016/1607 Safavid authority was re-imposed and henceforth became permanent till the appearance of Russia in the region in the 18th century (see Roemer, pp. 266, 268; Barthold and Bosworth, 1997, p. 489).

Την αναφερόμενη βιβλιογραφία θα βρείτε εδώ:

http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/servansahs

==========================

Šervān (Širvān, Šarvān)