#Seminole Freedmen

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

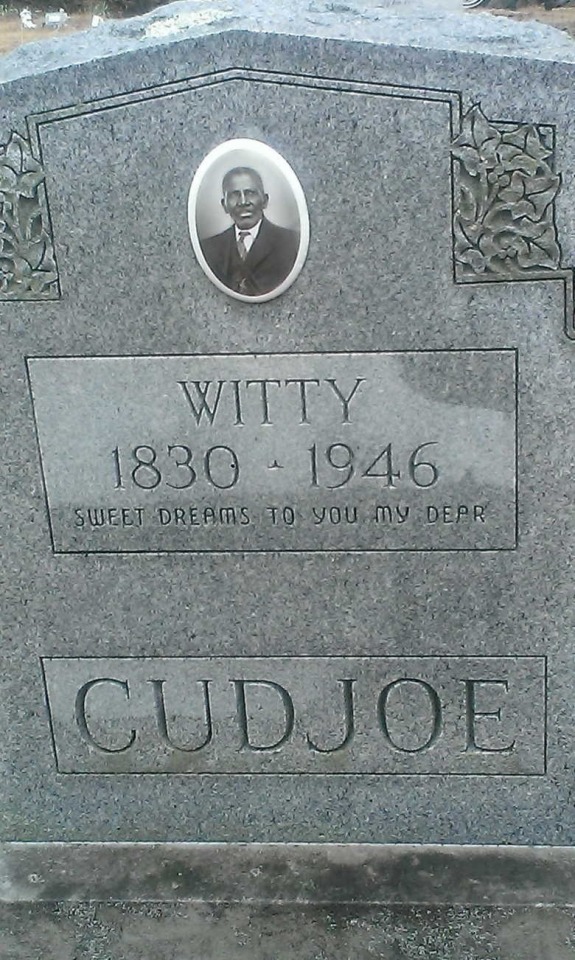

Witty Cudjoe

It's Black History Month in the United States, and I want to share the story of my 3rd Great Grandfather, Witty Cudjoe.

Born in 1830 during the Seminole Wars in Florida, Witty Cudjoe shared his memories in a newspaper article published when he turned 105. Witty's heritage is a legacy of warriors, tracing back to his grandfather, King Cudjo. King's journey from slavery in the Carolinas to freedom in Spanish Florida in the 1700s marked the beginning of a lineage that shaped the Seminoles. Witty's father and grandfather fought alongside fellow Seminoles, facing Andrew Jackson and the United States Army. Witty also discussed the removal to Indian Territory after a deceptive treaty with the United States. Despite being initially enslaved, Witty later fought as a Loyal Seminole, securing his freedom. He helped in the establishment of Wewoka, emerging as an important figure in his community. During a time marked by the exploitation of Native Americans, Witty and his wife Mariah faced attempts to manipulate them out of their land allotments. Despite being unable to read or write, Witty took legal action and won, a remarkable feat at the time. Witty's courage and determination defined his story, blessing future generations through the land he secured. Despite challenges posed by statehood, Witty leased 10 acres of his land to establish a school, preserving the Muscogee language and Seminole culture for his children. Witty lived to the age of 116, passing away in 1946. During my last visit to Oklahoma, I met a 94-year-old cousin who had cared for Witty in his later years. Hugging her felt like reaching back through time, expressing gratitude to Witty for my existence. Reflecting on our history, I see similarities with other communities, such as the Palestinians fighting for freedom. Like the Palestinians, they too faced forced displacement and theft of identity. Despite everything, our ancestors stood strong, and our community perseveres. In solidarity with the Palestinian community, I commemorate Black History Month, acknowledging shared struggles. I hope that by standing together, we can illuminate the path home for all displaced people someday.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Black Seminoles | African-Native American History & Culture

Also called: Seminole Maroons or Seminole Freedmen

Black Seminoles, a group of free blacks and runaway slaves (maroons) that joined forces with the Seminole Indians in Florida from approximately 1700 through the 1850s. The Black Seminoles were celebrated for their bravery and tenacity during the three Seminole Wars.

The Native American Seminoles living in Florida were not one tribe but many. They spoke a variety of Muskogean languages and had formed an alliance to prevent European settlers from expanding into their homelands. The word they used to describe themselves—Seminole—is derived from a Creek word meaning “separatist” or “runaway.” Because slavery had been abolished in 1693 in Spanish Florida, that territory became a safe haven for runaway slaves. Throughout the 18th century, many free blacks and runaway slaves went to Florida and lived in harmony with the Seminoles. Their proximity to and resulting collaboration with the Seminoles led students of the group to refer to them as Black Indians, Black Seminoles, and eventually—especially among scholars—Seminole Maroons, or Seminole Freedmen.

Most Black Seminoles lived separately from the Indians in their own villages, although the two groups intermarried to some extent, and some Black Seminoles adopted Indian customs. Both groups wore similar dress, ate similar foods, and lived in similar houses. Both groups worked the land communally and shared the harvest. The Black Seminoles, however, practiced a religion that was a blend of African and Christian rituals, to which traditional Seminole Indian dances were added, and their language was an English Creole similar to Gullah and sometimes called Afro-Seminole Creole. Some of their leaders who were fluent speakers of Creek were readily admitted to Seminole society, but most remained separate.

There are a number of references, beginning in the late 18th century, to Seminole “slaves.” However, slavery among the Seminole Indians was quite different from what was practiced in the slave states to the north of Florida. It had nothing to do with ownership or free labour. The only real consequence of the status of Black Seminoles as “slaves” was that they paid an annual tribute to the Seminole Indians in the form of a percentage of their harvest.

The Black Seminoles were relatively prosperous and content. They farmed, hunted wild game, and amassed significant wealth. Many black men joined the Seminole Indians as warriors when their land or freedom was threatened. Others served as translators, helping the Seminoles understand not only the language but also the culture of Euro-Americans.

That cooperation endured only through the Seminole Wars of the first half of the 19th century. Euro-American settlers wanted the rich land occupied by the Seminoles, and Southern slaveholders were unnerved by free blacks who were armed and ready to fight and living just over the border from slave states. Between 1812 and 1858, U.S. forces fought several skirmishes and three wars against the Seminoles and the maroon communities.

The Black Seminoles were recognized for their aggressive military prowess during the First Seminole War (1817–18). That conflict began when General Andrew Jackson and U.S. troops invaded Florida, destroying African American and Indian towns and villages. Jackson ultimately captured the Spanish settlement of Pensacola, and the Spanish ceded Florida to the United States in 1821. About that time, some Black Seminoles chose to leave Florida for Andros Island, in the Bahamas, where a remnant of the Black Seminoles still remains, although they no longer identify themselves as such.

In 1830 the federal government enacted the Indian Removal Act, which stated the government’s intent to move the Seminoles from the southeast portion of the United States to Indian Territory in what is now Oklahoma. That event led to renewed conflict.

In the Second Seminole War (1835–42), Black Seminoles took the lead in stirring up resistance. Although some bands of Seminoles had signed a treaty agreeing to the move, they did not represent the whole body of Seminoles. When the time came to leave, they resisted and fought an impassioned guerrilla war against the U.S. Army. Once again, during that conflict, Black Seminoles proved to be both leaders and courageous fighters. Often cited as the fiercest conflict ever fought between the United States and Indians, the Second Seminole War dragged on for seven years and cost the U.S. government more than $20 million. By 1845, however, most Seminoles and Black Seminoles had been resettled in Oklahoma, where they came under the rule of the Creek Indians.

Although both groups were subjugated by the Creeks, life was much worse for the Black Seminoles, and many left the reservation for Coahuila, Mexico, in 1849, led by John Horse, also known as Juan Caballo. In Mexico the Black Seminoles (known there as Mascogos) worked as border guards protecting their adopted country from attacks by slave raiders. The Third Seminole War erupted in Florida in 1855 as a result of land disputes between whites and the few remaining Seminoles there. At the end of that war, in 1858, fewer than 200 Seminoles remained in Florida.

When slavery finally ended in the United States, Black Seminoles were tempted to leave Mexico. In 1870 the U.S. government offered them money and land to return to the United States and work as scouts for the army. Many did return and serve as scouts, but the government never made good on its promise of land. Small communities of descendants of the Black Seminoles continue to live in Texas, Oklahoma, and Mexico.

How Black Seminoles Found Freedom From Enslavement in Florida

Black Seminoles were enslaved Africans and Black Americans who, beginning in the late 17th century, fled plantations in the Southern American colonies and joined with the newly-formed Seminole tribe in Spanish-owned Florida. From the late 1690s until Florida became a U.S. territory in 1821, thousands of Indigenous peoples and freedom seekers fled areas of what is now the southeastern United States to the relatively open promise of the Florida peninsula.

Seminoles and Black Seminoles

African people who escaped enslavement were called Maroons in the American colonies, a word derived from the Spanish word "cimarrón" meaning runaway or wild one. The Maroons who arrived in Florida and settled with the Seminoles were called a variety of names, including Black Seminoles, Seminole Maroons, and Seminole Freedmen. The Seminoles gave them the tribal name of Estelusti, a Muskogee word for black.

The word Seminole is also a corruption of the Spanish word cimarrón. The Spanish themselves used cimarrón to refer to Indigenous refugees in Florida who were deliberately avoiding Spanish contact. Seminoles in Florida were a new tribe, made up mostly of Muskogee or Creek people fleeing the decimation of their own groups by European-brought violence and disease. In Florida, the Seminoles could live beyond the boundaries of established political control (although they maintained ties with the Creek Confederacy) and free from political alliances with the Spanish or British.

The Attractions of Florida

In 1693, a royal Spanish decree promised freedom and sanctuary to all enslaved persons who reached Florida, if they were willing to adopt the Catholic religion. Enslaved Africans fleeing Carolina and Georgia flooded in. The Spanish granted plots of land to the refugees north of St. Augustine, where the Maroons established the first legally sanctioned free Black community in North America, called Fort Mose or Gracia Real de Santa Teresa de Mose.

The Spanish embraced freedom seekers because they needed them for both their defensive efforts against American invasions, and for their expertise in tropical environments. During the 18th century, a large number of the Maroons in Florida had been born and raised in the tropical regions of Kongo-Angola in Africa. Many of the incoming enslaved Africans did not trust the Spanish, and so they allied with the Seminoles.

Black Alliance

The Seminoles were an aggregate of linguistically and culturally diverse Indigenous nations, and they included a large contingent of the former members of the Muscogee Polity also known as the Creek Confederacy. These were refugees from Alabama and Georgia who had separated from the Muscogee, in part, as a result of internal disputes. They moved to Florida where they absorbed members of other groups already there, and the new collective named themselves Seminole.

In some respects, incorporating African refugees into the Seminole band would have been simply adding in another tribe. The new Estelusti tribe had many useful attributes: many of the Africans had guerilla warfare experience, were able to speak several European languages, and knew about tropical agricultures.

That mutual interest—Seminole fighting to keep a purchase in Florida and Africans fighting to keep their freedom—created a new identity for the Africans as Black Seminoles. The biggest push for Africans to join the Seminoles came after the two decades when Britain owned Florida. The Spanish lost Florida between 1763 and 1783, and during that time, the British established the same harsh enslavement policies as in the rest of European North America. When Spain regained Florida under the 1783 Treaty of Paris, the Spanish encouraged their earlier Black allies to go to Seminole villages.

Being Seminole

The sociopolitical relations between the Black Seminole and Indigenous Seminole groups were multi-faceted, shaped by economics, procreation, desire, and combat. Some Black Seminoles were fully brought into the tribe by marriage or adoption. Seminole marriage rules said that a child's ethnicity was based on that of the mother: if the mother was Seminole, so were her children. Other Black Seminole groups formed independent communities and acted as allies who paid tribute to participate in mutual protection. Still, others were re-enslaved by the Seminole: some reports say that for formerly enslaved people, bondage to the Seminole was far less harsh than that of enslavement under the Europeans.

Black Seminoles may have been referred to as "slaves" by the other Seminoles, but their bondage was closer to tenant farming. They were required to pay a portion of their harvests to the Seminole leaders but enjoyed substantial autonomy in their own separate communities. By the 1820s, an estimated 400 Africans were associated with the Seminoles and appeared to be wholly independent "slaves in name only," and holding roles such as war leaders, negotiators, and interpreters.

However, the amount of freedom that Black Seminoles experienced is somewhat debated. Further, the U.S. military sought the support of Indigenous groups to "claim" the land in Florida and help them "reclaim" the human "property" of Southern enslavers. This effort ultimately had limited success but is historically significant nonetheless.

Removal Period

The opportunity for Seminoles, Black or otherwise, to stay in Florida disappeared after the U.S. took possession of the peninsula in 1821. A series of clashes between the Seminoles and the U.S. government, known as the Seminole wars, took place in Florida beginning in 1817. This was an explicit attempt to force Seminoles and their Black allies out of the state and clear it for white colonization. The most serious and effective effort was known as the Second Seminole War, between 1835 and 1842. Despite this tragic history, approximately 3,000 Seminoles live in Florida today.

By the 1830s, treaties were brokered by the U.S. government to move the Seminoles westward to Oklahoma, a journey that took place along the infamous Trail of Tears. Those treaties, like most of those made by the United States government to Indigenous groups in the 19th century, were broken.

One Drop Rule

The Black Seminoles had an uncertain status in the greater Seminole tribe, in part because of their ethnicity and the fact that they had been enslaved people. Black Seminoles defied the racial categories set up by the European governments to establish white supremacy. The white European contingent in the Americas found it convenient to maintain a white superiority by keeping non-whites in artificially constructed racial boxes. The "One Drop Rule" stated that if one had any African blood at all, they were African and, therefore, less entitled to the same rights and freedoms as Whites in the new United States.

Eighteenth-century African, Indigenous, and Spanish communities did not use the same "One Drop Rule" to identify Black people. In the early days of the European settlement of the Americas, neither Africans nor Indigenous peoples fostered such ideological beliefs or created regulatory practices about social and sexual interactions.

As the United States grew and prospered, a string of public policies and even scientific studies worked to erase the Black Seminoles from the national consciousness and official histories. Today in Florida and elsewhere, it has become increasingly difficult for the U.S. government to differentiate between African and Indigenous affiliations among the Seminole by any standards.

Mixed Messages

The Seminole nation's views of the Black Seminoles were not consistent throughout time or across the different Seminole communities. Some viewed the Black Seminoles as enslaved people and nothing else. There were also coalitions and symbiotic relationships between the two groups in Florida—the Black Seminoles lived in independent villages as essentially tenant farmers to the larger Seminole group. The Black Seminoles were given an official tribal name: the Estelusti. It could be said that the Seminoles established separate villages for the Estelusti to discourage Whites from trying to re-enslave the Maroons.

Many Seminoles resettled in Oklahoma and took several steps to separate themselves from their previous Black allies. The Seminoles adopted a more Eurocentric view of Black people and began to practice enslavement. Many Seminoles fought on the Confederate side in the Civil War; the last Confederate general killed in the Civil War was a Cherokee leader, Stand Watie, whose command was mostly made up of Seminole, Cherokee, and Muskogee soldiers. At the end of that war, the U.S. government had to force the Southern faction of the Seminoles in Oklahoma to give up their enslaved people. It wasn't until 1866 that Black Seminoles were accepted as full members of the Seminole Nation.

The Dawes Rolls

In 1893, the U.S. sponsored Dawes Commission was designed to create a membership roster of Seminoles and non-Seminoles based on whether an individual had African heritage. Two rosters were assembled: the Blood Roll for Seminoles and the Freedman Roll for Black Seminoles. The Dawes Rolls, as the document came to be known, stated that if your mother was Seminole, you were on the blood roll. If she was African, you were placed on the Freedmen roll. Those who were demonstrably half-Seminole and half-African would be placed on the Freedmen roll. Those who were three-quarters Seminole were place on the blood roll.

The status of the Black Seminoles became a keenly felt issue when compensation for their lost lands in Florida was finally offered in 1976. The total U.S. compensation to the Seminole nation for their lands in Florida came to $56 million. That deal, written by the U.S. government and signed by the Seminole nation, was written explicitly to exclude the Black Seminoles, as it was to be paid to the "Seminole nation as it existed in 1823." In 1823, the Black Seminoles were not yet official members of the Seminole nation. In fact, they could not be property owners because the U.S. government classed them as "property." Seventy-five percent of the total judgment went to relocated Seminoles in Oklahoma, 25% went to those who remained in Florida, and none went to the Black Seminoles.

Court Cases and Settling the Dispute

In 1990, the U.S. Congress finally passed the Distribution Act detailing the use of the judgment fund. The next year, the usage plan passed by the Seminole nation excluded the Black Seminoles again from participation. In 2000, the Seminoles expelled the Black Seminoles from their group entirely. A court case was opened (Davis v. U.S. Government) by Seminoles who were either Black Seminole or of both African and Seminole heritage. They argued that their exclusion from the judgment constituted racial discrimination. That suit was brought against the U.S. Department of the Interior and the Bureau of Indian Affairs: the Seminole Nation, as a sovereign nation, could not be joined as a defendant. The case failed in U.S. District Court because the Seminole nation was not part of the case.

In 2003, the Bureau of Indian Affairs issued a memorandum welcoming Black Seminoles back into the larger group. Attempts to patch the broken bonds that had existed between Black Seminoles and the rest of the Seminole population have seen varied success.

In the Bahamas and Elsewhere

Not every Black Seminole stayed in Florida or migrated to Oklahoma. A small band eventually established themselves in the Bahamas. There are several Black Seminole communities on North Andros and South Andros Island, established after a struggle against hurricanes and British interference.

Today there are Black Seminole communities in Oklahoma, Texas, Mexico, and the Caribbean. Black Seminole groups along the border of Texas/Mexico are still struggling for recognition as full citizens of the United States.

Sources

Gil R. 2014. The Mascogo/Black Seminole Diaspora: The Intertwining Borders of Citizenship, Race, and Ethnicity. Latin American and Caribbean Ethnic Studies 9(1):23-43.

Howard R. 2006. The "Wild Indians" of Andros Island: Black Seminole Legacy in the Bahamas. Journal of Black Studies 37(2):275-298.

Melaku M. 2002. Seeking Acceptance: Are the Black Seminoles Native Americans? Sylvia Davis v. the United States of America. American Indian Law Review 27(2):539-552.

Robertson RV. 2011. A Pan-African analysis of Black Seminole perceptions of racism, discrimination, and exclusion The Journal of Pan African Studies 4(5):102-121.

Sanchez MA. 2015. The Historical Context of Anti-Black Violence in Antebellum Florida: A Comparison of Middle and Peninsular Florida. ProQuest: Florida Gulf Coast University.

Weik T. 1997. The Archaeology of Maroon Societies in the Americas: Resistance, Cultural Continuity, and Transformation in the African Diaspora. Historical Archaeology 31(2):81-92.

#Black Seminoles | African-Native American History & Culture#Seminoles#Black Seminoles#Black Maroons#Maroons#How Black Seminoles Found Freedom From Enslavement in Florida#florida#spanish florida#freedmen

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Battle of ‘Negro Fort’ – Inside America's Forgotten Slave Rebellion - MilitaryHistoryNow.com

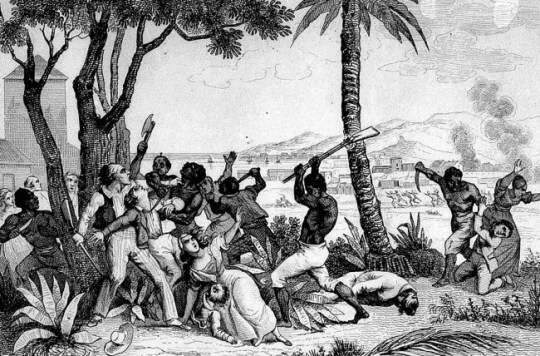

A year after the Battle of New Orleans, runaway slaves armed by the British occupied a stockade in Spanish Florida. The so called “Negro Fort” became a mecca for other fugitives from Southern plantations. In 1816, the U.S. Army arrived to crush the settlement. (Image source: WikiCommons)

“The Battle of the ‘Negro Fort,’ marks a critical moment when the federal government took a decisive stance in support of slavery and its expansion.”

By Matt Clavin

THE TIDAL MARSHES of Florida’s Apalachicola River were still under the authority of the Spanish crown in 1816, yet the events that took place there would go on to become a forgotten yet tragic chapter in the long and bloody history of American slavery.

It was during that year that an army of fugitive slaves, armed with foreign weaponry and united by dreams of freedom, would fight and die against a legion of American troops and allied Creek Indians dispatched by a future U.S. president bent on their destruction.

The Battle of the ‘Negro Fort’ marks a critical moment when the federal government took a decisive stance in support of slavery and its expansion.

What would become known as Negro Fort actually sprung from the War of 1812, one of the United States’ most misunderstood conflicts. During the contest’s third and final summer, Britain landed hundreds of troops on Florida’s Gulf Coast in preparation of an invasion of the southern United States.

Still Spanish territories at the time, East Florida and West Florida were neutral in the second war between the American Republic and the United Kingdom. Yet, the uncontested arrival of British troops there suggested the local authorities had ostensibly sided with the redcoats.

Americans’ fears of a Spanish-British alliances only increased when a detachment of Royal Marines erected a sizeable fort on the eastern shore of the Apalachicola River in the Florida Panhandle. Commanders of the new outpost then called upon Native Americans and fugitive African American slaves from across the region to join the British at the fort and together take up arms against the United States. Eventually, more than a thousand Creek, Choctaw, and Seminole Indians, along with several hundred runaways from southern plantations, accepted the invitation.

Following the final ratification of the Treaty of Ghent in the spring of 1815, the British withdrew their forces from Florida. With their powerful allies suddenly gone, most of the Indians gathered at the Apalachicola fort returned to their homes. But the hundreds of fugitive slaves inside the stockade had no place to go and so remained at the abandoned British post. And with the fort’s massive earthworks, wooden palisades and stone buildings at their disposal, along with an arsenal of hundreds of muskets, swords, bayonets and dozens of cannon, the runaways chose to remain there come what may.

Under an informal system of government that can best be described as martial law, this militant black community organized daily for its defence. At the same time, it established important relationships with the neighbouring Choctaws, Creeks, and Seminoles, who provided food and other sustenance in return for weapons and ammunition.

Negro fort was, in a word, formidable.

One British officer who, following the Treaty of Ghent, set out to assist some of the fugitive’s former owners regain their valuable property offered a curt assessment of fort’s inhabitants.

“The blacks are very violent & say they will die to a man rather than return.”

In the coming weeks and months, Hawkins and a number of prominent frontier citizens and officials flooded Washington with reports of rebellious slaves and their savage Indian allies running wild across the southern frontier. The accounts were almost entirely exaggerated.

Although clashes between Indians and settlers on disputed lands throughout the American south were commonplace in the early 19th Century, aside from inspiring an exodus of fugitive slaves from the southern states into Florida, the Negro Fort posed no threat to the United States.

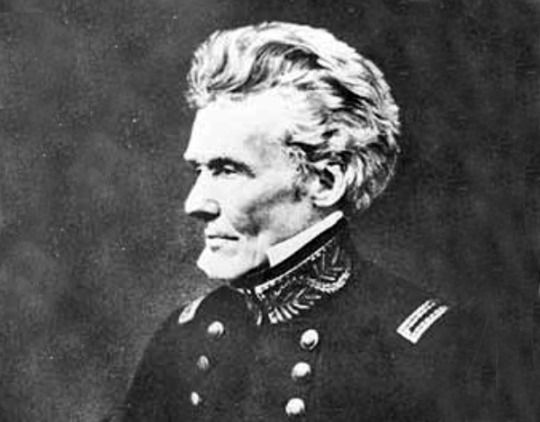

None of this stopped the commander of the United States’ southern army, General Jackson, from taking bold and aggressive action against the settlement.

Through a careful and calculating correspondence, Jackson ordered General Edmund Gaines, a hero of the War of 1812, invade Florida with 100 regulars, destroy the fort and return all of its black inhabitants to their American and Spanish owners. To ensure an American victory with as few friendly casualties as possible, Jackson secured the assistance of hundreds of Creek warriors by promising them a cash reward of as much as $50 dollars a head for every black slave returned to captivity.

Over the course of the next two weeks, hundreds of pro-American Creek warriors clashed with black rebels in the dense woods surrounding the fort, which at times descended into bloody hand-to-hand combat.

With American troops watching from a safe distance, the number of casualties went unrecorded—though it must have been considerable.

When a failed sortie by the fort’s defenders was repulsed, an American eyewitness suspected it was only a ruse.

“Many circumstances convinced us,” army doctor Marcus Buck wrote to his father, “that most of them determined never to be taken alive.”

With a pause in the ground fighting, American army and navy vessels on the river exchanged cannonfire with the fort’s defenders for several days.

The bombardment continued to the morning of July 27, when a heated cannonball, or “hotshot,” fired from U.S. Gunboat 154 flew over walls of Negro Fort’s massive inner citadel, landing directly on a gunpowder magazine.

The response of American officials to the destruction of Negro Fort was muted, largely because the entire campaign was illegal. After all, with neither congressional nor executive authority, the United States armed forces had invaded a foreign territory.

By contrast, southern slave owners hailed the battle’s outcome as the dawning of a new day. A Georgia writer expressed this view when reporting “the capture of the Negro and Indian Fort, on Apalachicola.” He explained that because of the efforts of his “brave countrymen,” the southern and western frontiers were now free of the “predatory incursions” posed by black and Indian bandits “whose numbers were daily augmenting; and whose strength and resources presented a fearful aspect to our peaceful borders.”

Within two years of the Battle of Negro Fort, Jackson and the American army again invaded Florida. The resulting First Seminole War would be the first of three wars between the United States and Florida’s black and Indian population who simply refused to submit to their northern American neighbours.

Though Negro Fort survived for only a year, its memory endured in the hearts and minds of hundreds of its inhabitants who had abandoned the outpost prior to its destruction. By fleeing to the Florida peninsula and aligning with the Seminole Indians, most of these former slaves carved out difficult but free lives on the outer edges of the American republic.

As many as one hundred of them were even more fortunate, finding not only freedom but peace and tranquility in the West Indies. By boarding trading vessels and escaping to the Bahama Islands several years after the Battle of Negro Fort, they completed the improbable journey from American slaves to British subjects.

#The Battle of ‘Negro Fort’ – Inside America's Forgotten Slave Rebellion#florida#negro fort#negro abraham#Freedmen#seminole indians#florida enslaved#history of slave settlements in florida

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Black Maroons of Florida (1693-1850) •

I tell you that people don't know anything about American History and how Christianity played an evil part in the dehumanization of dark skin humans worldwide and here we are today still allowing these stupid and ignorant people to divide our planet.

9 notes

·

View notes

Note

Not sure if this is something that would be interesting for you to answer, but do you think there is any way a slave revolt at some point early on (or just before the civil war) could’ve established some kind of break away nation in the south? There’s so much emphasis on edge lord “what if the bad guys win!” type stuff that I’ve tried pondering this but I’m not sure if it would be possible. Do you think this could’ve been done with the right “here’s money to look the other way big northern business and political people?” Or would it always be doomed to fail because even if luck broke the revolt/revolutions way against the whole south the north would just send an army to quash it because most white northerners would still be upset white people were dieing/that part of the country was “being taken away.”

Ah, the dream of self-determination in the Black Belt...

So if we're talking sometime close to the Civil War, what we're really talking about is the John Brown scenario, whereby a state for freedmen would be established in the hill country of Appalachia. I think the problem is that, even had John Brown's raid on Harper's Ferry not gone awry so quickly (and had he had a more realistic number of soldiers), the speed at which a U.S military dominated by Southerners like Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson as well as multiple state militias mobilized to suppress the revolt speaks to how well-developed the American system of repressing slave revolts had become in the 19th century.

If we're talking earlier, then I think you do have some historical examples in the form of maroon communities like the Black Seminoles in Florida or the Great Dismal Swamp in Virginia and North Carolina, although there you're talking about runaways rather than a slave revolt. The problem as I see it is that you're combining the practical difficulties of carrying off a slave revolt - which always, always, always faced massive state repression - with the difficulties of maintaining an independent state in the face of American imperialism.

For example, the Black Seminoles were able to prosper in Florida because it was a Spanish colony and the Spanish had a policy of providing refuge to runaway slaves as a measure to destabilize the English and eventually Americans to their north - however, the existence of an armed native/freedmen state just on the other side of the Georgia state line prompted Andrew Jackson to launch a series of "punitive expeditions" that forced Spain to hand over Florida to the United States, which allowed him to bring in the U.S military to try to force the Seminoles into reservations and then try to remove them to Oklahoma. The Seminoles effectively used guerilla tactics to resist the U.S military for some time, but when they bring in 30,000 troops and use starvation tactics, they were absolutely decimated.

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

John Carter Leftwich (June 6, 1867 - July 14, 1923) was born in Forkland, Alabama. The first son of Frances Edge and Lloyd Leftwich, one of Alabama’s last Black Reconstruction Era state senators, he graduated from Selma University. He held a deep admiration for Booker T. Washington and wrote to him for aid and advice. He was appointed Alabama’s Receiver of Public Money by President William McKinley. He founded an all-Black town named Klondike. He lost the support of Washington. Alabama Blacks were disfranchised. He migrated to Oklahoma Territory to begin anew.

He founded a newspaper, the Western World, and corresponded with Governor T.B. Ferguson, hoping to resume his bureaucratic career. He stumped for the Republican Party and in support of industrial education for African Americans. His efforts to regain a position in government failed.

He accepted the presidency of Sango Baptist College. This began his almost twenty-year career educating African Americans, Freedmen, and some Native American children in Oklahoma. In 1905, he established the Creek-Seminole College in the all-Black town of Boley. Financial difficulties plagued him and within a few years, he moved the school to Clearview, another all-Black town. He established the Bookertee Agricultural and Mechanical College in the all-Black town of Bookertee. In 1921, the school admitted children displaced by the Tulsa Race Riot.

He sought financial assistance for his endeavors from Oklahoma governors and wealthy white patrons. He joined the Democratic Party in 1910 even though Oklahoma Blacks were disfranchised via the grandfather clause. His efforts met with limited success and money troubles continued to haunt him, ultimately leading to his death. He was shot to death by a schoolteacher whom he had dismissed without paying. #africanhistory365 #africanexcellence

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The last community gets three articles for a very obvious reason:

Their existence not only shaped the definition of the USA's southern boundaries (and under the current Governor of Florida's system as such the beginning of Florida's history is now illegal to teach in the state), but did so in a way that helped to launch the career of one Andrew Jackson and touched off the longest Indian War in the Southern United States.

And the reasons for this were that Spanish power in Florida was fairly weak, US power in southern Georgia was weaker, and Maroons took advantage of obvious weaknesses to run away from slavery and built up a strong, well-armed community in alliance with the new Simanoli/Seminole people formed out of the shattered nations of Spanish power and the fall of the Mississippians.

For the so-called 'democrat', the existence of a Black and Indigenous alliance on the border of the Slave Power was an intolerable slight and it was his legacy that set in motion the annexation of Florida and three bloody wars to squelch it.

#lightdancer comments on history#black history month#black resistance#slavery and resistance#florida history#black history is florida history#fuck you ron desantis#seminole wars#black seminoles

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

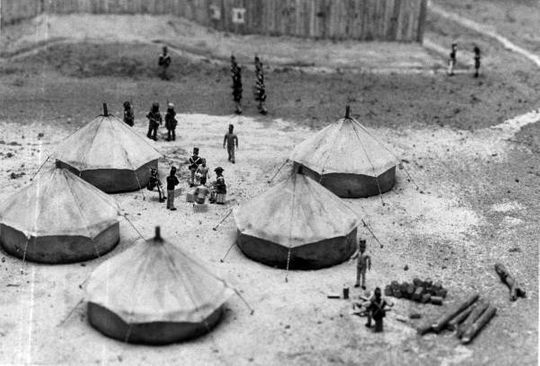

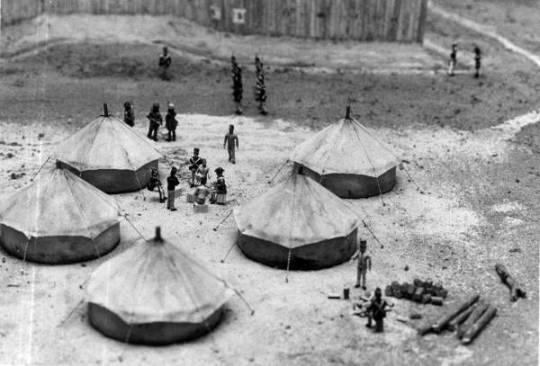

Image #1

Rhonda Grayson, with an image of her great-great grandfather Willie Cohee.

Image #2

Johnnie Mae Austin, whose grandfather was ‘Creek to the bone,’ is a plaintiff in the Creek Freedmen suit. Photograph: Brett Deering/The Guardian

Suing to Reclaim Identity... Is this Action?

The Facts

The ability to sue a nation that has deprived them of connection to their identity is a great source to call for action. Black Native Americans who were apart of the Creek Nation are almost never allowed to join this tribe due the constitution made in 1979. The tribe made this constitution to prevent them from joining. The tribe actually took a vote to "reconstitute citizenship parameters", this kicked out black people who have been members since 1866. The citizenship was limited to the blood quantum which I have talked about in previous posts (Having to have a certain amount of blood to be required Native American). This case for Johnnie Mae Austin to prove her lineage of creek blood which can be found in the "Creek Freedman list of the Dawes roll" still is hindered based upon the perception that there still is not enough Native American blood. The Creek Nation has stated they are a "independent agency", Austin's attorney is sure they have to follow the law just as anyone else. This case may end similar as the lost taken by the Seminole tribes for this case problem.

Highlights from the Stories

"Johnnie Mae Austin and her grandson, Damario Solomon-Simmons, can tell you everything about their ancestry. They can go back as far as 1810, the year Solomon-Simmons’ great-great-great-great-grandfather, Cow Tom, was born. With undeniable pride, they recount the man’s feats of bravery during the civil war, and his leadership within Oklahoma’s Creek population."

"In fact, they are so determined to let the world know exactly who Cow Tom was that they’re suing the Creek nation to make sure his descendants aren’t forgotten."

"Roberts says the actual disenfranchisement of black people by the Creeks and the Cherokee started in the late 20th century coincided with a time when a lot of the tribes had begun to build their economies and make a lot of money. She points out this was precisely the time when many of the Nations started to see an “influx of enrollment applications”.

"The current Creek principal chief, Jamie Floyd, declined to comment, and his press officers referred me to the nation’s citizenship office led by Nathan Wilson. “We’re an independent agency constitutionally and we’re listed in the Constitution as independent,” Wilson told me."

"But the vagueness of the nation’s response shouldn’t be read as a dismissal of the importance of the citizenship issue. In fact, the Creek nation is lawyering up. Venable LLP, a top Washington DC law firm, contacted Solomon-Simmons in August on behalf of the Creek nation. Both the Creek nation and the interior department have filed motions to dismiss on 5 October and the court will respond on 2 November."

Read Entire Story Here

0 notes

Text

A quick amendum to point out that two companies of these dudes (the Corps of Colonial Marines) took part in the burning of Washington, although I can’t quite work out if they helped burn the White House specifically. These were escaped slaves recruited by the British in exchange for their freedom - it seems that this promise was actually kept, and they would settle after the war in Nova Scotia, Bermuda, the Caribbean and most notably Florida, where they allied with the Seminoles against the United States.

Basically, freedmen burned Washington lmao

happy burn the white house day

19 notes

·

View notes

Photo

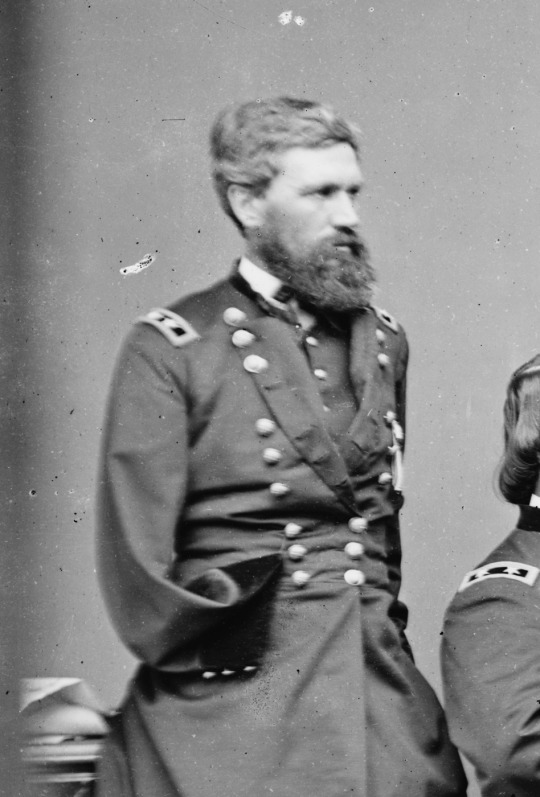

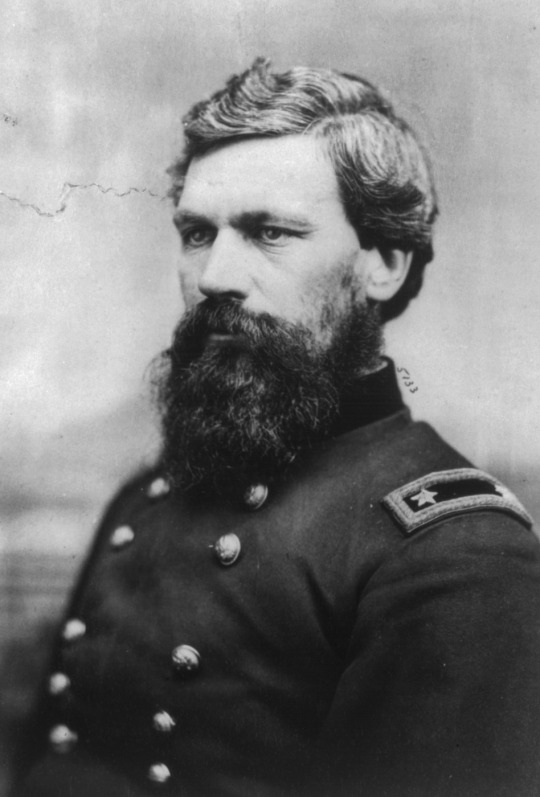

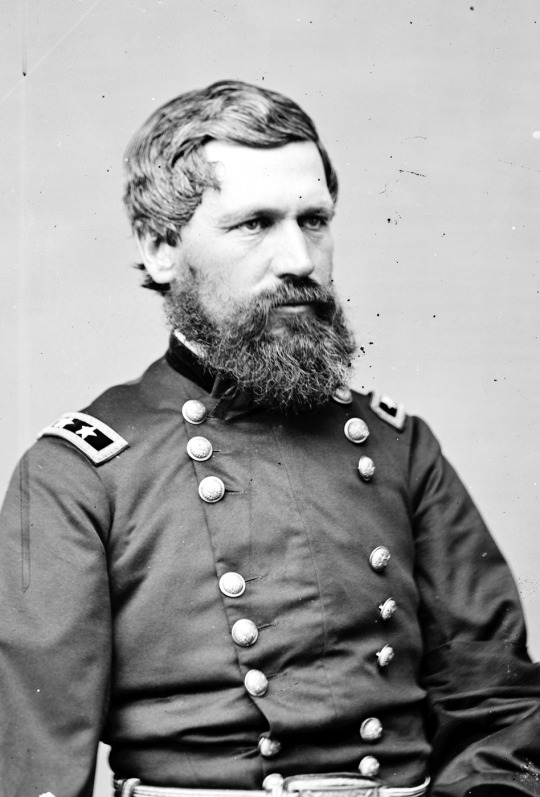

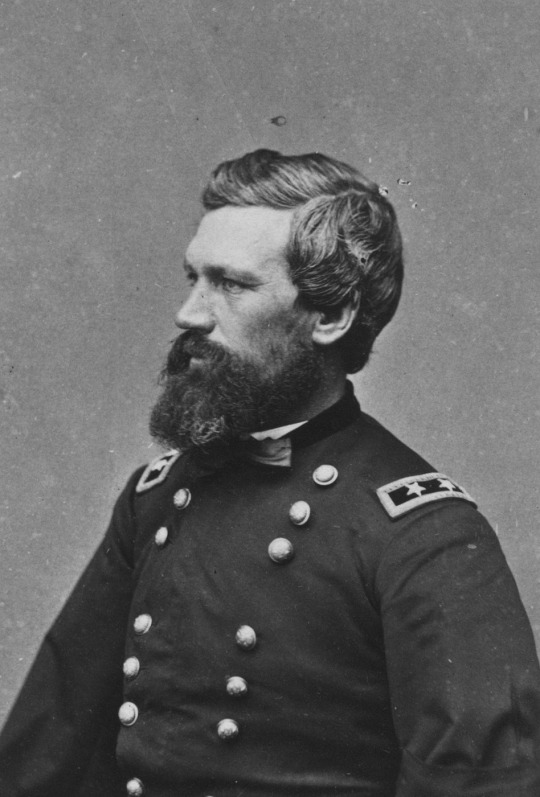

Known as “the Christian General,” Oliver Otis Howard is a unique figure in Civil War history. Despite lackluster performances by troops under his command, Howard’s reputation as an efficient and personally courageous officer would lead to command of an army by the war’s end.

Born in Leeds, Maine to Rowland Bailey and Eliza Otis Howard, young Oliver was educated in North Yarmouth, Maine before graduating from Bowdoin College in 1850. Immediately upon graduation, Howard received an appointment to West Point, joining a long gray line that also included Jeb Stuart, Dorsey Pender, and Commandant Robert E. Lee’s son, Custis. Howard graduated in 1854, fourth in a class of forty-six, one place behind future General Thomas H. Ruger.

In 1857, after routine assignments on the East coast, Howard took part in the campaign against the Florida Seminoles. It was here that the previously religious officer underwent a serious conversion to evangelical Christianity. Though he remained in the army, Howard often contemplated entering the ministry—even while serving as assistant professor of mathematics at West Point. Howard’s piety would later be source of ridicule for the general, and the sobriquet “the Christian General” was rarely used without some disdain.

But as history would have it, a certain grace seems to have accompanied Howard’s wartime service. In May of 1861, he was made colonel of the 3rd Maine Volunteer Infantry, resigning his regular army commission. He commanded a brigade at the First Battle of Bull Run, and though driven from the field in confusion, was promoted to brigadier general that fall. Again at the head of a brigade in the Union Second Corps in the spring of 1862, Howard lost his right arm at the battle of Seven Pines but would return to the field in time to form the Army’s rear guard at Second Manassas. Three weeks later, at the battle of Antietam, he relieved wounded division commander John Sedgwick, and would retain the command until the end of the year.

In the spring of 1863, following his promotion to major general, Howard was elected to replace Franz Sigel as the head of the XI Corps. A revolutionary from Germany, the immensely popular Sigel was the perfect choice to lead the predominantly German unit. Howard, however, with his penchant for strict military and moral discipline, did little to gain the respect of his troops before the battle of Chancellorsville. Posted on the right flank on May 2, 1863, Howard’s men bore the brunt of Stonewall Jackson’s devastating flank attack. Though the corps commander displayed personal bravery in attempting to rally his troops, many—including Army commander Joseph Hooker—blamed Howard and his “flying Dutchmen” for the Union rout. These same troops would flee in confusion two months later at the battle of Gettysburg. Their commanding officer, however, would receive the thanks of the United States Congress for selecting the ground upon which the next days’ battle was fought—a deed most attributed to Maj. Gen. Winfield S. Hancock.

Sent to the aid of William Rosecrans’ Army of the Cumberland at Chattanooga in the autumn of 1863, Howard remained in the western theatre for the duration of the war. In May of 1864, he led the IV Corps during William T. Sherman’s Atlanta Campaign. Following the death of James B. McPherson, Sherman selected the Christian General to head up the Army of Tennessee during his scorched earth campaign through the Carolinas. Howard finished the war a brigadier general in the Regular Army, ranking from the capture of Savannah.

An ardent abolitionist before the war, Howard’s postwar days were spent looking after the welfare of the recently emancipated slaves. In May of 1865, he was made the first and only commissioner of the Freedmen’s Bureau, and though the organization itself was rife with corruption, Howard again emerged from the ordeal unscathed. He went on to serve as superintendent of West Point and in 1893 received the Medal of Honor for bravery at the Battle of Seven Pines. He retired from the Army, a major general, in 1894.

Howard continued to be interested in education late into his life. Having founded Howard University in 1867, the general was also instrumental in the establishment of Lincoln Memorial University in the mountains of Tennessee. Oliver Otis Howard died in October of 1909 in Burlington, Vermont, where he is buried in Lake View Cemetery.

#oliver otis howard#american civil war#civil war#history#so this info about howard is taken from the american battlefield site#and if you've watched some of their stuff there's a guy named kris who uh doesn't like howard lol#and i can feel a little bit of him in this write up which is pretty funny#but yes! ol' O.O.Howard....great head of hair

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Alice Brown Davis

The first female Principal Chief of the Seminole Nation of Oklahoma, Alice Brown David (1852-1935) was an educator, a politician, and an advocate for Native issues.

One of seven children, Brown was a member of the Seminole Katcvlke, or Tiger Clan. When she was just 15, a cholera epidemic broke out in the tribe and both her parents died. She moved in with her older brother where she completed her education and began teaching others, both Seminole children and the children of freedmen.

As she grew, she received more and more prominence. When her brother, John F. Brown, was Chief, she worked as an interpreter and liaison. She was the postmistress, the superintendent of the Seminole Nation's girl's school, and a delegate to Mexico. Brown was fluent in English and Mikasuki.

In 1922, Brown was appointed the Principle Chief of the Seminole Nation by President Harding following the death of her brother. She was the first female Chief in Seminole history, and her appointment was controversial at first. As Chief, she won the respect of her people and focused on retaining and obtaining land, especially refusing to allow education to be taught by non-Native people. Tribal land affairs were her key political issue, including land allotments and oil leases.

#american history#world history#history#indigenous history#20th century#badass women#us history#women in history#alice brown davis#seminole#seminole county#seminole tribe#seminole nation#tiger clan#native americans#nativeamericans#native women#american indian movement#indigenous#land back#decolonization#indigenous sovereignty#indigenous people#indigenous resistance#decolonize

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

When the Seminole Indians Aligned With Escaped Slaves

The Black Seminoles were a group of people that history, for the most part, forgot about. Their alliance with the native Seminole tribes resulted in a unique relationship that had never been seen before, and that changed the course of history for both the Seminoles and the State of Florida as a whole.

The Black Seminoles, sometimes called Maroons, were a group of freed men and runaway slaves living in Florida during the mid-16th century. They settled the first free Black town in American history, attained their freedom by joining the Spanish and converting to Catholicism, and formed a tight cultural bond with the Seminole tribes.

#When the Seminole Indians Aligned With Escaped Slaves#Freedmen#florida#Seminoles#Black Indians#Black History Matters#Black History of Florida#Black History Month 2024#bhm24#2024#Youtube

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hurricane Michael unearths hidden history at ‘Negro Fort’ where 270 escaped slaves died – ASALH – The Founders of Black History Month

https://asalh.org/hurricane-michael-unearths-hidden-history-at-negro-fort-where-270-escaped-slaves-died/

PROSPECT BLUFF — Two hundred years ago, a post overlooking the Apalachicola River housed what historians say was the largest community of freed slaves in North America at the time.

Hurricane Michael has given archaeologists an unprecedented opportunity to study its story, a significant tale of black resistance that ended in bloodshed.

The site, also known as Fort Gadsden, is about 70 miles southwest of Tallahassee in the Apalachicola National Forest near the hamlet of Sumatra.

British lived at Prospect Bluff with allied escaped slaves, called Maroons, who joined the British military in exchange for freedom, along with Seminole, Creek, Miccosukee and Choctaw tribe members.

The Negro Fort, which was built on the site by the British during the War of 1812, became a haven for escaped slaves. Inside, 300 barrels of gunpowder were stored, and defended by both women and men.

More:The Negro Fort: a haven for escaped slaves that fell to deadliest cannon shot in U.S. history

Wary of the group of armed former slaves in Spanish Florida living so close to the United States border, U.S. soldiers began to attack. On July 27, 1816, U.S. forces led by Colonel Duncan Clinch ventured down the river and fired a single shot at the fort’s magazine. It exploded, killing 270 escaped slaves and tribes people who were inside. Those who survived were forced back into slavery.

Managed by the U.S. Forest Service, which purchased it in the 1940s, the site has been preserved as a National Historic Landmark and park. Because of that, it was never excavated for artifacts, except in 1963 by Florida State University, mainly to identify structural remains.

“It’s a really intriguing story. There’s so much new ground there that historians of the past never really got into,” said Dale Cox, a Jackson County-based historian.

In an ironic way, Hurricane Michael has changed that — an isolated upsideof the devastating storm.

The October Category 5 hurricane caused extensive damage to the site, toppling about 100 trees. Most of the debris has been cleared, but under the remaining massive roots, archaeologists began this month to dig and sift through the soil, uncovering small artifacts and documenting archaeological features revealed by the upturned trees.

The effort is funded by a $15,000 grant awarded from the National Park Service and is in partnership with the Southeast Archaeological Center.

"The easy, low-hanging fruit is European trade ware that dates to that time period. But when you have ceramics that were made by the locals, it's even more unique and special," said U.S. Forest Service Archaeologist Rhonda Kimbrough. "For one thing, there's not much of it, and we don't have a whole lot of historical records other than the European view from what life in these Maroon communities was like."

So far, Kimbrough and others have found bits of Seminole ceramics, shards of British black glass and gun flint and pipe smoking fragments. They’ve also located the area of a field oven, a large circular ditch that surrounds a fire pit.

The fort was recently inducted into the National Park Service’s Underground Railroad Network to Freedom.

"It’s like connecting the sites, pearls on a string," said Kimbrough, "because these sites, even though they’re spread all over the place, they’re connected by one thing, which is resistance to slavery."

It's been a slow process of sifting through Census records, which are private for 72 years before release, international archives of Great Britain as well as Spanish archives in Cuba. But Cox is on a quest to name as many as possible.

The people who lived in the Maroon community were very skilled, he said. Many were masons, woodworkers, farmers. They tended the surrounding melon and squash fields, but little is known precisely about their day-to-day lives.

The area has always been ideal for settling, given its higher elevation and clearings amid the river's mostly swampy perimeter, said Andrea Repp, a U.S. Forest Service archaeologist. Prior to European occupation, the site was sacred to natives and was named Achackweithle, which resembles the words for "standing view" in Creek, according to the Florida Geological Survey.

Shack, 76, is a descendant of Maroons. His great great grandfather escaped a North Carolina plantation, married a part-Native American woman and settled in Marianna. He remembers his grandmother's stories about the Prospect Bluff community.

"I remember her telling us about the 'Colored Fort' and all the colored folk who died," he said. "A lot of black history wasn't taught. A lot of our history is lost, and some of it we won't get back. I'm glad that there's a renewed interest in capturing the history that I thought was lost."

#Hurricane Michael unearths hidden history at ‘Negro Fort’ where 270 escaped slaves died#florida#Negro Fort#Seminoles#Black Freedmen#Black

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Unlike Black Americans across the country after slavery, Williams’ ancestors and thousands of other Black members of slave-owning Native American nations freed after the war “had land,” says Williams, a Tulsa community activist. “They had opportunity to build a house on that land, farm that land, and they were wealthy with their crops.”

“And that was huge — a great opportunity and you’re thinking this is going to last for generations to come. I can leave my children this land, and they can leave their children this land,” recounts Williams, whose ancestor went from enslaved laborer to judge of the Muscogee Creek tribal Supreme Court after slavery.

In fact, Alaina E. Roberts, an assistant professor at the University of Pittsburgh, writes in her book “I’ve Been Here All the While: Black Freedom on Native Land,” the freed slaves of five Native American nations “became the only people of African descent in the world to receive what might be viewed as reparations for their enslavement on a large scale.”

Why that happened in the territory that became Oklahoma, and not the rest of the slaveholding South: The U.S. government enforced stricter terms for reconstruction on the slave-owning American Indian nations that had fully or partially allied with the Confederacy than it had on Southern states.

While U.S. officials quickly broke Gen. William T. Sherman’s famous Special Field Order No. 15 providing 40 acres for each formerly enslaved family after the Civil War, U.S. treaties compelled five slave-owning tribes — the Choctaws, Chickasaws, Cherokees, Muscogee Creek and Seminoles — to share tribal land and other resources and rights with freed Black people who had been enslaved.

By 1860, about 14% of the total population of that tribal territory of the future state of Oklahoma were Black people enslaved by tribal members. After the Civil War, the Black tribal Freedmen held millions of acres in common with other tribal members and later in large individual allotments.

The difference that made is “incalculable,” Roberts said in an interview. “Allotments really gave them an upward mobility that other Black people did not have in most of the United States.”

The financial stability allowed Black Native American Freedmen to start businesses, farms and ranches, and helped give rise to Black Wall Street and thriving Black communities in the future state of Oklahoma. The prosperity of those communities — many long since vanished —“attracted Black African Americans from the South, built them up as a Black mecca,” Roberts says. Black Wall Street alone had roughly 200 businesses.

Meeting the Black tribal Freedmen in the thriving Black city of Boley in 1905, Booker T. Washington wrote admiringly of a community “which shall demonstrate the right of the negro, not merely as an individual, but as a race, to have a worthy and permanent place in the civilization that the American people are creating.”

And while some tribes reputedly gave their Black members some of the worst, rockiest, unfarmable land, that was often just where drillers struck oil starting in the first years of the 20th century, before statehood changed Indian Territory to Oklahoma in 1907. For a time it made the area around Tulsa the world’s biggest oil producer.

For Eli Grayson, another descendant of Muscogee Creek Black Freedmen, any history that tries to tell the story of Black Wall Street without telling the story of the Black Indian Freedmen and their land is a flop.

“They’re missing the point of what caused the wealth, the foundation of the wealth,” Grayson says.

The oil wealth, besides helping put the bustle and boom in Tulsa’s Black-owned Greenwood business district, gave rise to fortunes for a few Freedpeople that made headlines around the United States. That included 11-year-old Sarah Rector, a Muscogee Creek girl hailed as “the richest colored girl in the world” by newspapers of the time. Her oil fortune drew attention from Booker T. Washington and W.E.B. Dubois, who intervened to check that Rector’s white guardian wasn’t pillaging her money.

The wealth from the tribal allotment also gave rise to Williams’ family story of great-aunt Janie, “who learned to drive by going behind the trolley lines” in Tulsa, with her parents in the car, Williams’ uncle, 67-year-old Samuel Morgan, recounted, laughing.

“It was real fashionable, because it was one of the cars that had four windows that rolled all the way up,” Morgan said.

Little of that Black wealth remains today.

In May 1921, 100 years ago this month, Aunt Janie, then a teenager, had to flee Greenwood’s Dreamland movie theater as the white mob burned Black Wall Street to the ground, killing scores or hundreds — no one knows — and leaving Greenwood an empty ruin populated by charred corpses.

Black Freedmen and many other American Indian citizens rapidly lost land and money to unscrupulous or careless white guardians that were imposed upon them, to property taxes, white scams, accidents, racist policies and laws, business mistakes or bad luck. For Aunt Janie, all the family knows today is a vague tale of the oil wells on her land catching fire.

Williams, Grayson and other Black Indian Freedmen descendants today drive past the spots in Tulsa that family history says used to belong to them: 51st Street. The grounds of Oral Roberts University. Mingo Park.

That’s yet another lesson Tulsa’s Greenwood has for the rest of the United States, says William A. Darity Jr., a leading scholar and writer on reparations at Duke University.

If freed Black people had gotten reparations after the Civil War, Darity said, assaults like the Tulsa Race Massacre show they would have needed years of U.S. troop deployments to protect them — given the angry resentment of white people at seeing money in Black hands.

106 notes

·

View notes

Note

Oh yes I’m Gullah and we’re indigenous to Africa and reside in lowcounty. We’re also slowly losing our language and land here in the United States due to climate change and also other things. Seminole people also are descents of Gullah freedmen and native Americans. And there has been some mixing of native and Gullah people in the lowcounty. And from the 5 civilized tribes I would likely (still unsure) be mvskoke which is creek/Musc(k)ogee. Thank you for this conversation by the way I’d still have to do much more research of course. I’m also curious on how you would know if your ancestors were registered under one of the 5 tribes, I’ll look into that also I suppose. I don’t know if I’ll come off anon I’m actually really shy lol. No problem with the responds btw.

Oh i didnt know that Im so sorry about your language thats always such a devestating thing to know and deal with. Hopefully in the coming heres there will be more towards language revitalizing and conservation to make sure languages are kept alive

Best place to start is to contact the tribes (they have their own webbed sites) and pretty much tell them your situation and what to do next. Remember that you are not a burden or a hindrance, you are not bothering them. You are trying to find information.

Most likely they will ask you some questions or direct you to links to archives and what not.

But also i recommend taking a dna test on at least the top 2 or 3 dna test sites mostly to get matched up with cousins so that you can contact them and see if they have any info

Because maybe they have leads, maybe a name. So if you havnt done that thats also a good place to start

And dont worry about it, you can stay on anon if you feel more comfortable that way!

Also i recommend going into the Indian Country subreddit and Native American subreddit and post an ask there to get some suggestions on what to do, maybe even someone whos willing to help (you can make a throwaway account to feel more anonymous which may help shyness).

Ive posted there before and have had a lot of help and direction. And no need to mention your BQ, its no ones buisness.

But yeah 1. Contact the tribes and tell them your situation, ask them where to go from there 2. go into reddit and see if theres someone willing to help or give suggestions and 3. do a dna test on like ancestory and 23&me so you can maybe find some relatives that can give you more info

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sugar T. George a.k.a. George Sugar (C. 1827 - July 31, 1900) was born enslaved in the Muskogee Nation. This former enslaved emerged as a tribal leader. By the time of his death, he was said to have been the “wealthiest Negro in the [Indian] Territory.”

He escaped from bondage when in November 1861, Opothleyohola, an Upper Creek chief, led 5,000 Creeks, 2,500 Seminoles, Cherokees, and other Indians, and approximately 500 slaves and free African Americans from Indian Territory into Kansas to avoid living under the domination of Pro-Confederate Indian leaders during the Civil War. He joined the Union Army in Kansas, serving in Company H of the 1st Indian Home Guards. Because of his natural skills as a leader and his literacy, he became a First Sergeant in his unit. He acted as the unofficial leader of Company H, taking charge after the white officer and Indian officer had been dismissed for improper behavior.

After the War he rose to prominence, amassing money and influence in the Muskogee (Creek) Nation. He settled in North Fork, a Colored Town, in the Nation, and became a Town King (mayor). He served as a legal witness for his neighbors and often prepared letters for illiterate people in the community. In 1868 he was first elected to the Muskogee National Tribal Council, representing North Fork in both the House of Warriors and the House of Kings. He served in the National Muscogee legislature until 1895. He served on the board of the Tullahassee Mission School, a school for Creek and Seminole freedmen.

He married twice in his lifetime, first to Mariah McIntosh who died in 1867, and Betty Rentie (1876). He and Betty had no children, but they adopted and raised James Sugar as their son. He raised his step-grandchildren, Rena and Julia Sugar. #africanhistory365 #africanexcellence

1 note

·

View note