#Ronsin

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

The difference in treatment between the Indulgents and the Cordeliers or Hébertistes

I have an opinion that will seem unpopular, no worries I am open to any criticism or to being corrected in the event of an error so do not hesitate to correct me. I have much more sympathy for the Hébertist faction, the exaggerators or the Cordeliers than that of Danton's Indulgents. Indeed if we exclude the Hebert case who is an indefensible man, mediocre in my eyes (I don't think I need to explain why) this is not the case for so many others. I mean Ronsin was a competent and honest administrator. Despite his mysoginism (horribly reprehensible, just look at the speech he gave concerning the execution of Gouges and Manon Roland) Chaumette could be as competent as procureur syndicale de Paris and had also generous ideas (such as banning whipping in schools, equalization of funeral rites for all, protective measures for the elderly and hospitalized). One of the most impressive cases is Momoro. Even the historian Mathiez, who nevertheless has little sympathy for the revolutionaries who were against the Committee of Public Safety in the spring of 1794, had practically nothing but praise for Momoro. He voluntarily lived in poverty and when he was tried he said he had given everything for the revolution. It was true in my eyes. Of course I understand in a certain way the repression exercised by the Committee of Public Safety (more precisely the Convention since an arrest cannot be made without its agreement, it is not a dictatorship either) when Cordeliers wanted to launch a new insurrection against the Convention ( like Momoro for example). The fact of wanting to persecute the priests did not help, not to mention the fact that they wanted stronger repression of the enemies at the risk of making the Revolution even harsher. But when we analyze, I can understand where come frome their anger. Their hatred about religion was due to the fact that not long ago, a lot of religious fanatics infantilized the people, constantly made prohibitions against them (we must NEVER accept infantilization or loss of free will for religious reasons) and atrocious repressions without counting the their wealth that they monopolized (in terms of absurd repression there is nothing but to see the Calas affair, or that of the case of Chevalier de la Barre etc…), even if there were a lot of priest and believers weren't like that . Although the Cordeliers were wrong to respond to religious intolerance by intolerance, I can agree. The same goes for the Terror. At that time France was threatened by enemies from within and without and quite a few of their enemies carried out atrocious tortures (although rotten people like Fouché, Carrier, were not to be outdone in atrocities to the point that the Committee of Public Safety recalled them immediately). Prices were increasing because of the war, so without excusing them once again I can understand their minds when they demanded ever greater repression of the Terror (even if once again it was a serious error ,a mistake and even a fault).

Let's compare to the indulgent (or Dantonists) who are caught up in financial scandals (according to for a lot of historians like Jean Marc Schiappa). Danton moved only because of the financial scandals which were beginning to erupt and did not dare to attack head-on in this period of factional clashes, he let his friends do so. Moreover, according to certain historians like Decaux if I am not mistaken, he only came back against the Hebertists because they attacked them (and they did not only have them as enemies). He is not a clean character. Let's not talk about Fabre d'Eglantine. For Desmoulins I have an unpopular opinion of him. I find him very overrated and no matter how much I tried to appreciate his historical figure (by reading the very good biography of Leuwers or the book by Joseph Andras) I cannot. I don't think that despite the fact that he is very cultured, a man who rightly think that women must have the right of vote and even a republican before his time, he is not capable of assuming an important position unlike Saint Just or Ronsin who he made fun of. And worst of all I find him hypocritical, he who demanded clemency applauded the execution of the Hebertists following a parody of justice (yes I like the Montagnards of this period but this kind of thing should never be tolerated) . He didn't say anything when the wives of Momoro and Hebert were arrested which was very serious (afterwards I don't know well if they were arrested at the same time as Lucile Desmoulins), but he didn't realize that it was going well back in his face.

The Dantonists were irresponsible in my eyes. I completely agree that it was necessary to examine each prisoner on a case-by-case basis because there were surely a large number who had nothing to do there by creating as many commissions as possible as quickly as possible and getting down to business. job right away because prison is a horrible place, even more so for innocent people. But releasing everyone without distinction immediately would have been dangerous because there were also dangerous counter-revolutionaries or spies. I mean have they forgotten that the fall of Toulon to the English was due to betrayal? The betrayal of Dumouriez, the assassinations of some deputies, etc… Where did this idea of making peace with foreign armies still occupying France come from when the French army was beginning to be victorious? Opposing a war of conquest I completely agree, but allowing one's own territory to be annexed is something else. And how dangerous would it be to leave corrupt people like Danton in power. Sooner or later, he could perhaps have given in to blackmail in view of the evidence of corruption that contemporaries have today, which would have been very dangerous for France. As a result, I never understood why the “good” indulgent ones were portrayed against the “bad” Cordeliers and Hébertists. Whatever happens for all these factions, no matter my great admiration for revolutionaries like Le Bas, Saint Just, Couthon, the fact that I am sorry like many people that Robespierre is demonized, the fact that they allowed a parody of justice against these factions is an unforgivable fault and to have allowed the execution of Marie Françoise Goupil and Lucile Desmoulins among others to consolidate this parody of justice is unacceptable. Even if I understand their states of mind because they could not afford to lose especially in this period against these different factions and contrary to what the Thermidorians put forward, the majority of the Convention was just as guilty as them, there is no excuse for this kind of behavior. Did Saint Just realize this when he said that the Revolution was frozen (even he spoke more about the consequences of this repression and that the revolution is weakened on this point) ? It would later fall on them and Elisabeth Le Bas was threatened with being guillotined for having been Le Bas' wife (some wanted to force her into a marriage with one of the Termidorians). If they had not allowed the fate of Goupil or Lucile Desmoulins earlier perhaps it would have been more difficult for the Thermidorians to threaten her. For more information in the form of a movie , I invite you to see" Saint Just ou la Force des Choses" and " la Camera explore le temps Danton, la terreur et la vertue" in English sub. These are good movies about this period.

And you what do you think ?

#french revolution#Terror#georges danton#Camille Desmoulins#Ronsin#Momoro#Cordeliers#Indulgents#History#saint just#couthon#robespierre#lucile desmoulins#Hebert#Chaumette#joseph fouché#Carrier

61 notes

·

View notes

Note

Give me the last words of every figure that had a role in the French revolution

(Maybe it will be to many so you can give a little of if you want)

Louis XVI — on January 22 1793, Suite du Journal de Perlet reported the folllwing about the execution that had taken place the day before:

[Louis] climbs the scaffold, the executioner cuts his hair, this operation makes him flinch a little. He turns towards the people, or rather towards the armed forces which filled the whole place, and with a very loud voice, pronounces these words: “Frenchmen, I die innocent, it is from the top of the scaffold, and ready to appear before God, that I tell this truth; I forgive my enemies, I desire that France…” Here he was interrupted by the noise of the drums, which covered some voices crying for mercy, he himself took off his collar and presented himself to death, his head fell, it was a quarter past ten.

Jean-Paul Marat — several people who came to witness during the trial of Charlotte Corday reported Marat’s last words to have been a cry for help to his fiancée Simonne Évrard:

Laurent Basse, courier, testifies that being on Saturday, July 15 (sic), at Citizen Marat's house, between seven and eight o'clock in the evening, busy folding newspapers, he saw the accused come, whom citoyenne Évrard and the portress refused entrance. Nevertheless, citizen Marat, who had received a letter from this woman, heard her insist and ordered her to enter, which she did. A few minutes later, on leaving, he heard a cry: ”Help me, my dear friend, help me!” (À moi, ma chere amie, à moi !). Hearing this, having entered the room where citizen Marat was, he saw blood come out of his bosom in great volumes; at this sight, himself terrified, he cried out for help, and nevertheless, for fear that the woman should make an effort to escape, he barred the door with chairs and struck her in the head with a blow; the owner came and took it out of his hands.

The president challenges the accused to state what she has to answer. I have nothing to answer, the accused says, the fact is true.

Another witness, Jeanne Maréchal, cook, submits the same facts; she adds that Marat, immediately taken from his bathtub and put in his bed, did not stir.

The accused says the fact is true.

Another witness, Marie-Barbe Aubin, portress of the house where citizen Marat lived, testifies that on the morning of July 13, she saw the accused come to the house and ask to speak to citizen Marat, who answered her that it was impossible to speak to him at the moment, attenuated the state where he had been for some time, so she gave a letter to deliver to him. In the evening she came back again, and insisted on speaking to him. Aubin and citoyenne Évrard refused to let her in; she insisted, and Marat, who had just asked who it was, having learned that it was a woman, ordered her to be let in; which happened immediately. A few moments later, she heard a cry: "Help me, my dear friend!” (À moi, ma chere amie !);she entered, and saw Marat, blood streaming from his bosom; frightened, she fell to the floor and shouted with all her might: À la garde! Au secours !

The accused says that everything the witness says is the most exact truth.

Girondins — Number 64 of Bulletin du Tribunal Criminel, written shortly after the execution, reports that, once arrived at Place de la Révolution, the Girondins sang Veillons au Salut de l’Empire together while waiting for their turn to mount the scaffold. Lehardy’s last words are reported to have been Vive la République, ”which was generally heard, thanks to the vigorous lungs nature had provided him with.”

Hébertists — On March 31, a week after the execution, Suite de Journal de Perlet reported the following anecdote, though I’ll let it be unsaid whether it should be taken seriously or not:

Here is an anecdote which can serve to make better known the eighteen conspirators whom the sword of the law has struck. On the day of their execution, several heads had already fallen when General Laumur's turn arrived. Ronsin and Vincent looked at him at the scaffold and said to Hébert: ”Without the clumsiness of this j... f... we would have succeeded.” They were alluding to the indiscretion of Laumur, who would tell anyone who would listen that the Convention had to be destroyed.

In Mémoires sur Carnot par son fils (1861), Carnot’s son also claims that, on the day of the execution, his father got stuck in the crowd witnessing the tumbrils pass on their way to the scaffold, close enough to hear Cloots say: “My friends, please do not confuse me with these rascals.”

Dantonists — the famous idea that Danton’s last words were: ”show my head to the people, it’s worth seeing” is, according to Michel Biard, at best backed by a dubious source — Souvernirs d’un sexagénaire (1833) by Antoine Vincent Arnault:

I found there all the expression of the sentiment which inspired Danton with his last words; terrible words which I could not hear, but which people repeated to each other, quivering with horror and admiration. ”Above all, don't forget,” he said to the executioner with the accent of a Gracque, ”don't forget to show my head to the people; it’s worth seeing.” At the foot of the scaffold he had said another word worthy of being recorded, because it characterizes both the circumstance which inspired it, and the man who uttered it. With his hands tied behind his back, Danton was waiting his turn at the foot of the stairs, when his friend Lacroix, whose turn had come, was brought there. As they rushed towards each other to give each other the farewell kiss, a guard, envying them this painful consolation, threw himself between them and brutally separated them. "At least you won't prevent our heads from kissing each other in the basket," Danton told him with a hideous smile.

Biard does however question how reliant Arnault really is, considering his account partly contradicts what earlier, more reliable ones, had to say about the execution. None of the authentic to somewhat autentic descriptions of the dantonist execution I’ve been able to find mention any recorded last words from Danton or his fellow convicts. That has not hindered authors and historians throughout the centuries to let their imagination run wild with the execution — look for example at how many have had Danton say something menacing about Robespierre on his way to the scaffold. Early Desmoulins biographers often have him be a sobbing mess, saying things like "Citizens! it is your preservers who are being sacrificed. It was I — I, who on July 12th called you first to arms! I first proclaimed liberty… My sole crime has been pity...” (Methley, 1915) or ”Thus, then, the first apostle of Liberty ends!” (Claretie,1876) and for Fabre there exists the claim that he hummed his song Il pleut bergère on his way to the scaffold, or muttered his biggest regret was not being able to finish his vers (verses), to which Danton replied that, within a week, he’ll have more vers (worms) than he can dream of. None of these statements do however appear to be backed by any primary sources. Finally, John Gideon Millingen, twelve years old at the time of the execution, reported in his Recollections of Republican France 1791-1801 (1848) that ”[Danton’s] execution witnessed one of those scenes of levity that seemed to render death to a jocose matter. Lacroix, who was beheaded with him, was a man of colossal stature, and, as he descended from the cart, leaning upon Danton, he observed, ”Do you see that axe, Danton? Well, even when my head is struck off I shall be taller than you!” It does however strike me as unlikely for Milligen to actually have been able to hear anything of what the condemned had to say.

Robespierrists — like with the dantonists, we have several alleged last words from more or less unreliable sources. The apocryphal memoirs of the Sansons does for example report Saint-Just’s last words to have an emotionless ”Adieu” to Robespierre, and for the latter we have a story that his last recorded words were ”Merci Monsieur,” which he said to a man for giving him a handkerchief to wipe away the blood coming out of his shattered jaw with (can you even talk under such conditions?). However, here I have again collected trustworthy descriptions, and none of them record any last words. In this instance it’s not exactly strange either, given the fact many of the condemned had been injured so badly they were more or less unconscious by the time of the execution.

Other alleged final words can be found in this post, among others Madame Roland’s ”Oh Liberty, what crimes are committed in your name” and Bailly’s ”I’m cold.” I will however doubt the authenticity of all of them until someone shows me a serious source for them (the author of the post doesn’t cite any at all). Like I wrote above, I doubt anyone actually stood near enough to hear any eventual last words.

#french revolution#frev#robespierre#danton#brissot#hébert#louis xvi#desmoulins#fabre d’eglantine#ronsin#vincent#ask#the extent actual historians have fictionalized the death of actual people is pretty f:ed up if you ask me#read biard’s la liberté ou la mort: mourir en depute and you’ll see…

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

📷 Niki de Saint Phalle, dans son atelier à Paris, impasse Ronsin, 1961 — photo Marry Shunk & János Kender

#art#arts#artwork#artiste#niki de saint phalle#photo#photografy#photographers on tumblr#black and white#noir et blanc

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

On this day, 2nd of Brumaire, Year I (23 october 1792)

The Cordeliers Club where many virtuous patriots used to gather and discuss solutions to help the revolution go well. Their trust and the esteem that many of them had for me were beneficial to me.

On this day, 2nd of Brumaire Year I , the Journal de la Municipalité published the results of the election for the mayoral candidates. A great number of citizens honored me with their trust, granting me a significant number of votes. I was surpassed only by Panis, and I outperformed prominent figures such as Hérault de Séchelles and Fréteau.

Of course, if you wish to know the results of the election on November 8, 1792, I can tell you that I received 102 votes in the mayoral election, out of a total of 9,361 votes counted. Once again, I was defeated, but among those who surpassed me were Antonelle, with 336 votes, Lhuillier with 857, and Hérault de Séchelles with 801. However, I managed to place ahead of well-known names such as Danton, who received only 12 votes, Robespierre with 33 votes, Billaud-Varenne with 59 votes, and Collot d'Herbois with 13. Never would I have imagined surpassing one of the most eminent figures of the Revolution, Jean-Paul Marat, who received only 14 votes. I would not dare boast of this victory, as he has accomplished so many great things.

The elections concluded with Chambon’s victory. In the seventh and final round, I gathered 110 votes. I also obtained 172 votes for the position of prosecutor of the Commune of Paris on December 11. However, I find some consolation in the fact that Chaumette, who was appointed prosecutor, proved worthy of his office, not only through his patriotism but also through his revolutionary commitment, both in fighting poverty in Paris and combating counter-revolutionary forces.

When Chambon ended his tenure, I was once again listed among the mayoral candidates, but once more, I was defeated, securing only 27 votes in the final round on February 16, 1793. Nevertheless, my colleagues, who shared my views that the Revolution was progressing too slowly, continued to rise to increasingly important positions.

I did, however, encounter certain difficulties during these elections. I am firmly convinced that it is necessary to reform the voting methods in future elections to establish true transparency in the workings of the government. I advocate for public voting, rather than secret ballots, so that the true convictions of each citizen may be known without ambiguity. As president of my section, I was summoned by the Convention for having violated voting procedure rules during these elections.

As for my failure to become mayor, I have put it into perspective, especially since voter participation was quite low. The number of votes I received, and the fact that I was able to stand, even if temporarily, against more renowned figures such as Hérault de Séchelles, Danton, and Robespierre, comforted me, as did the esteem I received from the Club des Cordeliers. Moreover, a patriot worthy of the office, Pache, succeeded in being elected mayor. I had neither the time nor the right to feel sorry for myself. I had to leave on a mission for the Republic, which sent me to Vendée, where I reunited with my friend General Ronsin and formed a friendship with many patriots, including General Rossignol. But that story will be told another time.

Hail to the Republicans!

Momoro, First Printer of National Liberty

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

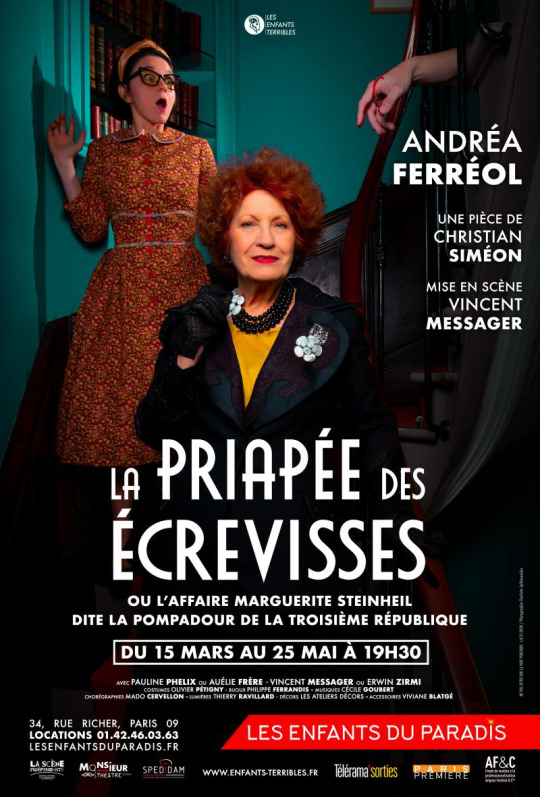

LA PRIAPÉE DES ÉCREVISSES

Avec Andréa Ferréol

Jusqu'au 25 Mai

Au Théâtre des Enfants du Paradis

Dans sa cuisine, Marguerite Steinheil s’exerce à son occupation favorite, la conception d’un plat sophistiqué “Les écrevisses à la Présidente” !…

Toujours plus raffiné, toujours plus succulent, celui-ci maintient son entraînement à l’art de se remémorer dans la métaphore, tous ces moments délicieux où la vie de ses intimes fut à portée de perversité !… Que ce soit le président Felix Faure mort dans ses bras, au cours d’une rencontre galante à l’Elysée en 1899, que ce soit son propre mari et sa mère étrangement assassinés en 1908 alors qu’elle était retrouvée elle-même ligotée et bâillonnée par son valet de chambre !

Marguerite Steinheil fut surnommée “La Sarah Bernhardt des Assises”, tellement sa fascination fut grande sur le jury et les magistrats qui l’acquittèrent en 1909 dans des applaudissements frénétiques !...

Vivante ! Marguerite Steinheil est vivante ! Elle a menti. Elle s’est vendue. Elle a trahi.

Elle a fréquenté les alcôves lambrissées du pouvoir.

Elle a surmonté le scandale le plus licencieux de la troisième République.

Elle a survécu à la très mystérieuse et très sanglante affaire de l’impasse Ronsin.

A la force du poignet, elle est devenue l’honorable, la richissime Lady Robert Brooke Campbell Scarlett-Abinger, baronne et pairesse d’Angleterre.

Alors elle cuisine.

Obstinément elle cuisine.

Avec jubilation. Avec hargne.

Juste pour nuire encore un peu.

N’hésitez plus, vous pourrez vous aussi dire, J’ai un ticket :

0 notes

Text

Avant le décalage puis le décollage de notre avion pour un port d’Italie, sous influence Austro-Hongroise, un petit détour par le centre Pompidou et son exposition du côté du sculpteur Brancusi. L’atelier de l’impasse Ronsin y est reconstitué pour partie en particulier ses outils et son établi. C’était un grand collectionneur d’œuvres d’art, de disques et il a reçu des cartes postales de Calder, Satie… des cartons inventifs, et délicieux pour les yeux et le reste. Je recommande chaudement l’exposition, il sculptait de mémoire, dans le matériau. Il s’est affranchi des moulages après un apprentissage par les ateliers de Rodin. Marcel Duchamp, Man Ray comptaient parmi ses amis. Le 1er lui a payé son loyer un certain temps. Parmi ses voisins, Tinguely et Niki de St Phalle. Ces ateliers d’artistes qui donnaient sur la rue de Vaugirard ont été détruits dans les années 1970… Il reste ses œuvres, son baiser, sa colonne sans fin, son poisson, son envol, ses visages, son coq, ses carnets, sa correspondance. Et o chance pour nous, il a tout conservé et légué !

View On WordPress

0 notes

Note

Bonaparte did much more than that in the list of grievances. Firstly, it wasn't him who saved the country. No one person saves a country alone. It's the entire people who do it, those who fight, those who bear the taxes, those who participated in the Bastille, on August 10th, who voted, those who ensured that the government remains effective, like the sans-culottes, those who fought in Year III against Boissy d'Anglas and company, etc. People who didn't participate in the government have just as much influence on history by exerting themselves tirelessly, and if you want names, here they are: Momoro, Simone Evrard, Louise Reine Audu, etc. Those who seek to profit from it must be fought against, or else they are impostors and fighters of the 25th hour in general (as happened during the Algerian revolution). In short, one must always remember the phrase: "There is only one hero: the people."

Secondly, if we really seek a government, in my eyes, it is the Montagnards like Billaud Varenne, Robespierre, Saint Just, Couthon, Le Bas, Charles Gilbert Romme, Ronsin (I talked about them in one of my posts during the excellent question asked by pleasecallmealsip https://www.tumblr.com/nesiacha/745212185045811200/in-your-opinion-what-was-the-most-significant?source=share). Here is their nuanced opinion, but they inherited a far more catastrophic situation than Napoleon and managed to save it independently, despite unforgivable excesses, but they did it, with a completely divided executive power and under universal suffrage. Of course, there were scoundrels who wanted to line their pockets (Tallien, Fouché, etc.), but let's not forget that the revolutionaries I mentioned wanted to punish them for their atrocities.

What did Bonaparte do? He did everything he shouldn't have done. Venturing beyond the borders and imposing wars of conquest. He said it was the monarchists who wanted war, but in that case, he should stick to natural borders and stay there. What he did was an invitation for France to be even more vulnerable. Moreover, if he resisted so well, one of the reason is that he inherited a better situation due to the work of his predecessors. I don't need to mention what he did in Jaffa. If I criticized revolutionaries committing atrocities, I don't see why I would spare him (even though honestly he's not a bloodthirsty being unlike the black legend). The guy does a coup and becomes a military dictator with a very rigged plebiscite. Compare him to Robespierre, Saint Just, Le Bas, and Couthon when they were outlawed, hesitating while they were in mortal danger and didn't seek as much trouble as Bonaparte, while 17 out of 49 sections spontaneously came to their aid, they wanted to stay within the law, hesitated, and had more scruples than him. Bonaparte did a coup for his glory and power ( with Sieyes) but fled for his life when he was justifiably outlawed thanks to the devoted army of others (this is my subjective judgment and Bonaparte has many flaws but is not a coward). Bonaparte never knew how to inspire true loyalty that cannot be bought with money but by merit (like Robespierre, Marat, Couthon, Romme, Prieur de la Marne). As a result, when he was in trouble, there was not a lot left. When Marat was accused, all of Paris rushed to him even though he didn't have a penny in his pocket.

Finally, the shameful reinstatement of slavery (many former slaves executed, hanged, pursued by dogs), the fact that he put women in worse conditions than other women in Europe, the civil code wasn't his idea fundamentally, he just took the idea and constantly regressed like in the worker's booklet, his hypocritical puritan laws, one law for him and his family and another for others. The executive power was too strong (it still is today). Moreover, the reinstatement of slavery was a grave mistake because unlike the other deputies of the Convention of 1792 (at least most of them), they were both moral and pragmatic. They knew that these former slaves would prefer to fight to the end and die, so they preferred to abolish slavery (Marat sang their praises and rightly predicted that Saint Domingue would become independent). Bonaparte, to solve one problem, created a bigger one. The same thing when he stupidly believed he could exploit countries without it backfiring on him. He blames everyone when there was the blunder of the Malet conspiracy when this conspiracy could never have happened under the Convention of 1792. And the worst thing is that since he has the strongest power, there are no collective faults like in the case of the Convention of 1792. He alone is the main culprit. The restoration of the monarchy was done under Napoleon in my opinion, not under Louis XVIII. What a betrayal. Louis XVI betrayed his country but never spent as much; he was furious about the Court's expenses and, at least, never betrayed his ideals. Napoleon did. His shameful expenses for himself and his family, the fact that he left France in a worse state than he found it, that he believed he could found a dynasty when it was obvious he couldn't, his shameful betrayal towards the Jacobins, the execution of the Duke of Enghien (what do I say, his assassination) just to consolidate his power, the scandal of the creation of the Bank of France, the fact that he married a Habsburg and that because of that, Francis, Emperor of Austria, tried at the fall of Napoleon to proclaim himself regent (he who wanted to destroy France because of the French Revolution) and thus almost got the keys to the country thanks to Bonaparte and his lack of foresight in this case.... Yes, in these cases, Bonaparte doesn't inspire sympathy from me. But he is adored due to propaganda that hides his thirst for power, the fact that the right needs him to justify that the executive is stronger than the legislative in my opinion, while Marat, Robespierre, Couthon, Romme, Babeuf, Momoro are either forgotten or demonized. Sorry if the answer was a bit harsh, it wasn't intended, and if you want to add because I'm not infallible. This is just my opinion.

as a frenchman i was confused and surprised at how much you guys as a whole dislike napoleon? he gets a lot of deserved rep for saving the country imo

bro he led 400,000+ French people to their deaths

meanwhile people act like the ~35k killed by the Reign of Terror was the worst humanitarian catastrophe in the history of humanity. it's just the double standard that pisses me off.

#napoleon#napoleon bonaparte#marat#robespierre#saint just#Prieur de la Marne#Romme Charles Gilbert#momoro#simone evrard#good answer

69 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Life of the Hébertist Charles Philippe Ronsin: From Playwright to Chief General of the Revolutionary Army

Charles Philippe Ronsin was born on December 1, 1751, to a master cooper in Soissons. According to Maurice Chartier, who draws on the work of General Herlaut, Ronsin may have been born into an affluent family and received an education. However, it is unclear whether he was a brilliant student, as Jacob Louis suggests, since various successive wars led to the loss of archives.

He enlisted in the army at the age of 17, in the Aunis regiment, but after four years, he left. Why? Maurice Chartier speculates that Ronsin realized the future of a commoner in the army of the Old Regime did not meet his youthful expectations. He instead sought success as a playwright. Unlike other future revolutionaries such as Collot d’Herbois or Fabre d’Eglantine, Ronsin did not achieve the success he hoped for. His works, including Hecuba and Polyxena, were staged by the Committee of Actors, but his next play, Sédécias, was rejected in December 1783. He is believed to have married before the Revolution, but the identity of his first wife, as well as what happened to her—whether they divorced or she became a widow—remains a mystery. Ronsin's past is, in many ways, shrouded in uncertainty.

He mingled in artistic and literary circles and became friends with the painter David. Ironically, his greatest successes would come in the army during the French Revolution, even though he had initially left the military for a career in theater.

Like many revolutionaries, Ronsin's involvement in the Revolution began in 1789 when he was elected captain of the National Guard of the Saint-Roch district. He quickly joined the Jacobin and Cordelier clubs and began forging friendships with figures such as Danton and Marat. Georges Lefebvre describes him as a diligent figure.

From 1792, following the fall of the monarchy, Ronsin played an increasingly significant role. He had joined the Théâtre-Français section, which played an important role during the storming of the Tuileries in 1792. He co-wrote a pamphlet with Murville in honor of the citizens killed on August 10, 1792. He was appointed commissioner of the Executive Council. Under the orders of Minister of War Pache (affiliated with the Hébertists), Ronsin was sent to Belgium to oversee the dubious Dumouriez (whose treachery would later be confirmed). He denounced the corruption of Dumouriez’s suppliers. Gaspard Monge then entrusted him with a mission in the North. When Bouchotte took over as Minister of War, Ronsin's career soared. This was the period when the Exagérés faction gained popularity and became a political force in the National Assembly (where the Enragés were more influential in the sections, especially in the Gravilliers section, but struggled to gain representation).

On February 14, 1793, Pache was elected mayor of Paris with 11,881 votes out of 15,191 voters. Bouchotte, seen as close to the Hébertists (even if he later distanced himself from them), reorganized the patriots' strongholds. As Renaud Faget points out, "The result of this policy was a significant increase in the number of employees: they were 453 in April 1793 and 1800 when Bouchotte was ousted." Pierre Gaspard Chaumette, the prosecutor of the Commune of Paris, and Hébert, his deputy, along with Vincent as the Secretary General of the Ministry of War in April 1793, filled the Ministry with Cordeliers members and sent people like Momoro to Vendée. They were the "stars" of the Cordeliers club, one of the most powerful at the time, and enjoyed a certain level of popularity.

Ronsin was appointed as deputy to the Minister alongside Xavier Audouin (an important Hébertist who later became a neo-Jacobin under the Directory) and Prosper Sijeas. His most important rise came in Vendée, where he quickly ascended from captain and logistics officer for the army to brigadier general, eventually becoming the chief general of the Revolutionary Army of Paris by the end of his life. Ronsin played a key role in the rise of General Rossignol. His rapid ascent was met with hostility from some, particularly the Indulgents, one of whom, Philippeaux, became one of his principal adversaries. Ronsin broke with Danton (possibly since the Dumouriez affair—this hypothesis requires further study). In any case, in Vendée, he reunited with his friend Momoro, who had been sent on a mission, likely with Vincent’s involvement.

The tactics used in the Vendée, particularly in the battle for Rigué, have been widely criticized (to put it mildly). The report by Momoro and Ronsin states: "We don’t doubt that a large number of complaints were addressed to the National Convention…[regarding this tactic]; the malevolent men only condemn these measures, which, as rigorous as they are, may alone create disorder in the brigands' army and finish a cruel war." It is evident that Ronsin and Momoro committed unforgivable mistakes in Vendée as I said here about Momoro https://www.tumblr.com/nesiacha/759184374456549376/momoros-serious-fault?source=share

Another major failure associated with Ronsin was in Lyon. He spent less than a month there and was politically aligned with Collot d'Herbois. It remains unclear to what extent Ronsin can be held responsible for the massacre in Lyon (the execution of Lyonnais citizens by cannon and disproportionate executions). However, it is known that he approved of it, as he wrote: "The guillotine and the firing squad have brought justice to over 400 rebels, but a new revolutionary commission has just been established, composed of true sans-culottes; my colleague Parein is its president, and in a few days, the artillery fire from our gunners will have rid us, in one instant, of over 4000 conspirators. It is time to shorten the process." Upon his arrival in Lyon, Ronsin wrote: "The revolutionary army entered the city on the 5th of Frimaire... Terror was painted on every face, and the deep silence I had recommended to our brave soldiers made their march even more threatening, more terrifying."

It is still difficult to know whether Ronsin directly participated in the violence in Lyon, but like many other revolutionary actors, he can be held responsible for not disapproving of it, especially since he witnessed it. That others like Turreau, Barras, Fréron, and Fouché were more corrupt than Ronsin does not absolve him of responsibility.

Despite this, Ronsin suffered from a notorious black legend, like many Hébertists, and was even demonized more than Robespierre himself. In truth, his rise was deserved because he was a competent and honest administrator who did not profit from his position. He was defamed by figures like Desmoulins, yet according to Lefebvre, Ronsin lived and died poor. He was a courageous and diligent soldier. While he was one of the leaders of the Hébertist faction (although, in reality, it was primarily Ronsin and Momoro who led the Exagérés, as Hébert backed down during critical moments, while Ronsin and Momoro went all the way), it is important to note that unlike Momoro, who primarily defended social rights and even advocated for shared agrarian property rights, Ronsin championed a radical revolution—though his views were underdeveloped—that aligned him more with the Cordeliers at that time, who were close to the Hébertists.

Lefebvre acknowledges Ronsin's flaws, noting that he could be arrogant and violent in his language. However, it was the danger facing the Republic that pushed him to adopt such an attitude, rather than any shameless ambition or opportunism (like his "friend" Turreau). I wonder if Ronsin’s break with Danton, particularly after the Dumouriez affair, did not make him more radical, along with the infernal situation of the time. Although Ronsin may not have had the military genius of Kleber or Jourdan, he was certainly competent for his rank.

Upon his return to Paris, Ronsin became one of the leaders of the Exagérés faction. In December 1793, he and his friend Vincent were arrested, notably on the proposal of Fabre and Philippeaux. They were released under pressure from the Cordeliers. This episode is detailed here. This certainly did not help with any reconciliation with the CPS (Committee of Public Safety), especially since the CSG (Committee of General Security) pointed out that there was no evidence against them. Additionally, other Hébertists had been arrested and then released. However, aside from the episode concerning the abolition of slavery, where most set aside their grudges, it seems that reconciliation was impossible. Personally, I think the faults are shared between the Indulgents, the Committee of Public Safety, the Convention, and the Hébertists.

The poverty of the Parisian working class during the winter must not have helped ease tensions, particularly for people like Momoro, who prioritized the fight (with the black market and some speculators, things probably worsened). As I’ve mentioned before, the tension was so high that the Cordeliers were preparing an insurrection attempt. Momoro presided over it and draped the Declaration of the Rights of Man in black. Ronsin supported and demanded it. Vincent followed this line of action. Hébert did as well, until he tried to backtrack when he realized that the attempt might fail. Chaumette, Pache, and Hanriot refused.

They took Carrier as an ally for this insurrection attempt, who had been recalled from Nantes for his drownings. Collot d'Herbois, pragmatically, tried to reconcile, as he was close to some points of Ronsin’s politics. Here is an excerpt from Michel Biard’s book on Collot d'Herbois:

"The Jacobin session of the 16th of Ventôse was almost entirely devoted to these declarations. In the absence of Robespierre and Couthon, who were ill, as well as Billaud-Varenne and Jeanbon Saint-André, who were on missions, Collot d'Herbois was the only member of the Committee who regularly attended the Society. It was he who went up to the tribune to denounce the behavior of the Cordelier leaders, using much firmer language than that reserved earlier for Desmoulins and those like him who were merely 'lost.' Here, if the Cordeliers were in the same situation, the leaders were nevertheless labeled as plotters, and Collot mentions the fate of Jacques Roux, who had also 'seduced' the Cordeliers and whom the Committee had had imprisoned.”

"And, in a final attempt at reconciliation, the Jacobins decided to send a delegation, led by Collot d'Herbois, to preach unity to the Cordeliers. Hébert, Ronsin, and other leaders took the walk of Canossa and, in front of the Jacobin delegation, claimed that their words had been misrepresented and that the fraternity between the two societies was not in question. Did Collot d'Herbois sincerely believe in this rather clumsy reconciliation? If there was any real illusion, it was quickly dispelled. New threatening speeches from Vincent, the discovery of anonymous posters calling for insurrection, the return of Robespierre, Billaud, and Couthon to the Committee... all of these factors led to the final decision. The Committee opted for a preventive strike. On the night of the 22nd to the 23rd of Ventôse, Hébert, Vincent, Ronsin, and other 'suspects' were arrested."

Carrier escaped this arrest because he retracted, likely sensing the change in the political wind (and I wonder if his initial support for the insurrection was opportunistic). Contrary to what the black legend of the Hébertists suggests, they did not intend to massacre the Convention but rather to recreate a day like June 2, 1793, probably by eliminating political figures such as Barère (though, of course, that would still have been illegal). During this tumultuous period, there were even “anthropophagist” inscriptions with Robespierre’s name. Elsewhere, there were posters from the Cordeliers’ Club declaring that Fabre d'Églantine, Camille Desmoulins, and a few others had lost their trust. Another was a clear call for insurrection: "Sans-culottes, it is time. Strike the general call and ring the tocsin, arm yourself and let it not be long, for you see that they are pushing you to your last breath." Other messages had a clearly royalist tone, such as one found on a public building: "Death to the Republic! Long live Louis XVII."

Those who sought to eliminate the Hébertists would mix the judgment of the faction with dubious characters. There were false rumors of plundering involving Momoro (I’ve learned, as I study law, that nowadays, sometimes, in order to discredit those being judged, some accusation files violate legal procedures and leak false information to the press to ensure the suspect loses sympathy; I wonder if they used the same method then). They were accused of "plotting with foreigners." The wives of Hébert and Momoro were arrested, and later, Ronsin's wife, according to the memoirs of Jean-Balthazar de Bonardi du Ménil. The Hébertists were condemned on false accusations, such as posting seditious posters, sabotaging food supplies, and massacring prisoners in jails. There was little evidence against them, yet the president of the Tribunal said, "Infamous, you will all perish!"

Except for Hébert, all were executed with great courage. Ronsin said to his colleagues, "You will be condemned. When you should have acted, you talked. Know how to die. For my part, I swear that you shall not see me flinch. Strive to do the same." And when someone said that it was the end of the Republic, he responded, "The Republic is immortal."

The revolutionary army would be dissolved.

From what I’ve deduced, Ronsin was definitely not a saint. He did things that were totally condemnable, which, even in times of war, are inexcusable. However, that Turreau behaved as a greater "scoundrel" with the infernal columns does not exonerate Ronsin. But Ronsin was also a man victimized by a black legend even more tenacious than others— he was a competent and honest administrator, far from being a stupid man that some aid. His violent words can be placed in the context that he, too, was at his wits' end, like Marat or other revolutionaries who were exhausted from the struggle. He more than deserved his rank, even though he was not a military genius like Kléber or Jourdan. I don’t get the impression that he acted out of shameless ambition, but rather from a genuine frustration that the Republic was in danger, compounded by the behavior of certain people (primarily Danton and the Dumouriez affair). My point is that the Hébertists were demonized even more than other revolutionary factions, when in reality, they were wrongly seen as bloodthirsty incompetents. However, they have very interesting stories and have had their share of both glory and a darker side, like all revolutionary groups.

The Fate of His Wife Marie-Angélique Lequesne, Widow Ronsin

There is an important hypothesis about Marie-Angélique Lequesne ( my theory). She is said to have met Ronsin in Belgium when he was supervising Dumouriez, or she was working as a canteen keeper, according to Geneanet. At that time, since Ronsin was not yet a general, he could not marry her, and it was only in 1793, when she came from a wealthier family than Ronsin’s, that they married. Here is the revolutionary period of Marie-Angélique Lequesne:

“Marie-Angélique Lequesne was caught up in the measures taken against the Hébertists and imprisoned on the 1st of Germinal at the Maison d'Arrêt des Anglaises, frequently engaging with ultra-revolutionary circles both before and after Ronsin’s death, even dressing as an Amazon to congratulate the Directory on a victory.”

According to the correspondence of Jorris, when she remarried Turreau, this is what was said about them. A.-J. de Rivaz dedicated an entire chapter to them in his Mémoires historiques sur le Valais. He expresses his hostility toward anyone who adhered to the principles of the French Revolution: Turreau "commits the blunder of not publicly performing any act of the Roman religion"; his wife, Marie-Angélique, "has the audacity to speak of it with contempt," and she does not blush "to say that she had never been happier since she had shaken off the yoke of the Christian superstition in which she had been raised."

Unfortunately, this marriage would become horrific for her. Turreau treated her with unimaginable cruelty, even having her flogged (a horrifying detail—I recently learned that it is very likely she was pregnant with their last child when he had her flogged). She followed her husband when he became an ambassador for Napoleon. She charmed the political class of Washington, unlike her husband. She became a very good friend of Dolley Madison, one of the most important future First Ladies of the United States, and played an essential role in her political development. Dolley described her as "good-natured, intelligent, generous, plain, and curious." They got along very well.

But Turreau continued to treat his wife terribly, and no one dared confront him about it until one day a judge confronted him. In retaliation, Turreau ordered Marie-Angélique to leave the United States, forced her to live in poverty for three years, and once again, it was the judge who arranged her departure to France. She eventually divorced him. Later, Turreau forced their daughter Alexandrine into a convent, and Marie-Angélique had to fight once more to free Alexandrine, which she succeeded in doing, according to this site: https://rembarre.fr/g_tur_ec.htm. Unfortunately, Alexandrine died in poverty years later.

An even more horrifying detail: Turreau, who called Charles-Philippe a friend from the time when Ronsin was still alive, stabbed him in the back by giving him a defeat, claiming that Ronsin was the one responsible, not him (while Turreau was the one truly responsible). You can see this in this post and here.

I wonder if Ronsin introduced Marie-Angélique to Turreau when they were still friends. After Ronsin was guillotined, Marie-Angélique Lequesne Ronsin went on to endure a terrible marriage with Turreau, who treated her with awful cruelty (as you can see in one of my posts here). In this way, Turreau betrayed the Ronsin couple a second time.

Sources:

Grace Phelan

https://www.jstor.org/stable/41929594?read-now=1&seq=4

Antoine Resche

(After studying it I disagree with Jacob Louis who says that Ronsin is incompetent but it remains an interesting analysis.

https://www.jstor.org/stable/41929592

#frev#french revolution#ronsin#hebertists#camille desmoulins#women in revolution#1790s#history#france#georges danton#jacques louis david#gaspard monge#vendée#turreau#collot d'herbois#lyon

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Contemporary descriptions of the hébertist execution compilation

The joy of the people was universal at seeing the conspirators taken to the scaffold. There were the same demonstrations of joy everywhere; a sansculotte jumped up and said: “I would light up my windows this evening, if candles were not so rare.” In the evening, in all the groups and cafes, people talked about the death of these conspirators; the story of their last moments was the only subject of conversation. It was said in several places that Hébert had denounced around forty deputies. It was time, they added, that this conspiracy was discovered, because it was believed in several departments that Paris was under fire. […] According to the comments made on the Place de la Révolution, during the appearance of the conspirators on the scaffold, one noticed that there were people placed to sow trouble. One woman was beaten by another for having made some comment. While the 19 conspirators were being guillotined, the people remained silent; but when Hébert’s turn came, a swarm of hats appeared, and everyone shouted: “Long live the Republic! This is a great lesson for those who are consumed by ambition; the intriguers have done well; the committees of public safety and general security will manage to discover them, and ça ira!” Tableaux de la Révolution française publiés sur les papiers inédits (1869) by Adolphe Schmidt, volume 2, page 186. ”Situation in Paris 4 Germinal Year 2” (March 24 1794).

The events of yesterday, that is to say the judgment of the conspirators, their journey from the Palace to the Place de la Révolution and their execution, have entirely absorbed the attention and feelings of the people. Everyone wanted to at least see them pass so that they could judge the impression made on their wicked souls by the sight of an immense people, outraged by their crime, and the knowledge of the imminent death they were going to suffer. The crowd of curious people who were on their way or who witnessed their execution was innumerable. [...] Two opposing feelings, indignation against the guilty and joy at seeing the Republic saved by their death, animated all the spectators. One tried to read the faces of the condemned to enjoy, in a way, the internal pain from which they suffered: it was a kind of revenge that they took pleasure in obtaining. The sans-culottes were especially angry with Hébert and insulted him. “He’s damn angry,” said one, “we broke all his stoves (fourneaux).” “No,” said another, “he is very happy to see that the real aristocrats are going to fall under the guillotine.” Others carried stoves? (fourneaux) and pipes and raised them in the air so that they could strike Father Duchesne's eyes. Regardless, this wretch could not pay any attention to what was happening around him; the horror of his situation appalled him; he had reproached Custine for dying as a coward, and he showed no less pusillanimity than him. Momoro put up, as they say, a brave face against bad luck, he pretended to be confident, talked to his neighbors and laughed a wicked laugh. [...] Cloots appeared calm, Vincent lost, Ancart and Ronsin furious and Hébert overwhelmed. The latter was the star of the show, he appeared last [on the scaffold]. Report by the police spy Grisel, March 25 1794, cited in La Liberté ou la Mort: mourir en député (2015) by Michel Biard.

On D-Day, March 24, 1794, an “innumerable crowd” impatiently awaited the execution of Father Duchesne and his accomplices: “Advancing from the place of execution of Paris, one encountered waves of citizens on their way there; everything resounded with the cry of “Father Duchesne to the guillotine!” and in this respect the children acted as peddlers.” Another agent remarks that “in the streets, from the Palace to the Place de la Révolution, the crowds of people were so great that one could barely pass through.” The police estimate (already!) claimed that “perhaps four hundred thousand souls witnesses to this execution.” […] If the legend claiming that Hébert fainted in the tumbril seems false, all reports corroborate on the other hand the moral and physical collapse which this great sermonizer presented: […] “It was noticed that Ronsin seemed the least frightened by his execution, that Anacharsis Cloots had retained great composure, but that Hébert and the others bore on their faces the signs of the greatest consternation;” [Another report states that]: “Of the nineteen culprits dragged to execution, Hébert was the one who presented the saddest and most dismayed face.” Taken from the Palace to the Place de la Révolution amid cries of joy and insults (“Everywhere they passed one shouted “Long live the Republic!,” and threw hats in the air and everyone said some epithet to them, especially to Hébert.”), Father Duchesne was not yet at the end of his troubles. To make the feast complete, a cruel staging allowed him to meditate on his fate: “Upon his arrival on the Place de la Révolution, he and his accomplices were greeted by boos and murmurs of indignation. With each head that fell, the people took revenge again with the cry of “Long live the Republic!” while throwing their hats in the air. Hébert was saved for last, and the executioners, after putting his head through the fatal window, responded to the wish that the people had expressed to condemn this great conspirator to a punishment less gentle than the guillotine, by holding the suspended blade for several seconds on his criminal neck, and throwing, during this time, their victorious hats around him and attacking him with poignant cries of ”Long live this Republic that he had wanted to destroy.” As can be seem, one knew how to have fun in those days. However, as soon as the affair was completed, the agents noted contrasting reactions among the people: “In all public places, the aristocrats and the moderates rejoiced at this execution and affected a lot of patriotism. The patriots also rejoiced, but they observed one another.” [Another report states] “I visited different cabarets near the Gros Caillou, near the Military School. They talked only about Father Duchesne, about whom a thousand stories were made with the intention to bless the Committee of Public Safety for having discovered such a betrayal. I found the little people cheerful”; [Another report states]: “The walks are everywhere full of people and everywhere one stays and asks: “Did you go to see Hébert yesterday?” One answers “yes”. All the faces seem happy.” [Another report states]: “Since Hébert’s death, I have noticed that, in cafés, men who talked a lot no longer say anything.” This is because the execution of Hébert and his supporters, although it purged the Mountain of its extremists, nonetheless shook the people’s confidence in their leaders. Who would believe if even the most ardent patriots could suddenly become traitors? At least one thing is certain, that is that beyond the unconscious dismay which struck the people after the execution, the great cowardice which Father Duchesne demonstrated before the guillotine ended up destroying him in the eyes of everyone: “After the execution, everyone was talking about the conspirators. They said: “They died like suckers”; others said: “We would have thought that Hébert would have shown more courage, but he died as a good-for-nothing.” Series of police reports found in Paris pendant la Terreur (1962) by Pierre Caron, cited in this blog post.

The execution took place in the afternoon around 5 o'clock, at the Place de la Révolution. A prodigious crowd of citizens filled all the streets and squares through which they passed. Repeated cries of long live the Republic and applause were heard everywhere. These testimonies of the indignation of the People against men who had just so eminently compromised the salvation of the Fatherland, were proportionate to the extreme confidence they had in the art of surprising them; and the public satisfaction whose feeling was mixed with this deep indignation was a new proof of the love of the citizens for the Republic saved by the punishment of these great culprits. Thus perishes anyone who dares to attempt the re-establishment of tyranny! Gazette Nationale ou Moniteur Universel, number 185 (March 25 1794)

It was 18 of them who suffered the death penalty due to their crimes... It was Father Duchesne, this scoundrel, who was cursed by all the people. If he had been susceptible to remorse, he would have died of shame before his arrival, in front of Madame Guillotine... He was the last to be guillotined, each of the closest spectators continued to reproach him for his villainy... Letter written by the Convention deputy Ayral Bernard, March 26 1794

Hébert, Ronsin, Vincent, and the other conspiracy defendants whose names and qualities we reported in previous issues, were sentenced to death by the revolutionary tribunal. Only one was acquitted; Laboureau: he was immediately set free; the president of the tribunal embraced him and made him sit next to him: the room resounded with the liveliest applause. The other defendants said nothing when they were sentenced; the Prussian Cloots appealed to the human race, of which we know that he had made himself the speaker. Ronsin wanted to say a few words, he was removed alongside the others. Femme Quetineau declared herself pregnant. Taken back to the Conciergerie, the condemned asked for half a septier of wine and a soup. Around four in the afternoon, they left on three tumbril to go to the execution. Never had an execution attracted such a considerable crowd of spectators; everywhere they passed, one clapped hands, tossed hats in the air, and shouted vive la république ! They seemed quite insensitive to the indignation that was brewing against them: arrived at the foot of the scaffold, they all embraced each other. Hébert, known as Father Duchesne, was the last to be guillotined; his head was shown to the people, and this spectacle provoked clapping of hands and universal cries of vive la république ! Annales Patriotiques et Litteraires de la France, et Affaires Politiques de l’Europe, number 369 (March 26 1794)

The republic has once again been saved: 19 leaders of the conspiracy hatched for its ruin were sentenced to death today, 4 germinal, at half past twelve. The flattering sword of the law struck their guilty heads: these traitors marched towards the scaffold with all the audacity of crime; some laughed, others raised their shoulders: Father Duchène appeared to be neither in great joy nor in great anger; the people applauded and stood in crowds in the places through which the procession was to pass. A lot of cavalry and infantry preceded, accompanied and followed the tumbrils carrying the conspirators: but armed force became useless, because joy was universal. Le Courier Belgique, number 39 (March 31 1794)

Here is an anecdote which can serve to make better known the eighteen conspirators whom the sword of the law has struck down. On the day of their execution, several heads had already fallen when General Laumur's turn had come. Ronsin and Vincent looked at him at the scaffold and said to Hébert: ”without the clumsiness of this j... f... we would have succeeded.” They were alluding to the indiscretion of Laumur, who would tell anyone who would listen that the Convention had to be destroyed. Suite de Journal de Perlet, number 555 (March 31 1794)

My father told me that only once, during the Revolution, he found himself stuck in the crowd, without being able to move forward or backward, as the fatal tumbril passed. It was the one who carried the Hébertists. Cloots, placed at one end, said to the spectators: “My friends, please do not confuse me with these rascals.” Mémoires sur Carnot par son fils (1861) volume 1, page 366.

-

Previous parts of this totally family friendly series:

Contemporary descriptions of the dantonist execution compilation

Contemporary descriptions of the robespierrist execution compilation

#happy 230th deathday guys!!#french revolution#frev#frev compilation#hébert#momoro#no one likes hébert…#like jesus they REALLY hated him

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

Les tirs de Niki de Saint Phalle

📷 Tir, séance du 26 juin 1961 en présence de Jean Tinguely et Niki de Saint Phalle, impasse Ronsin, Paris — photo Harry Shunk et János Kender

#art#arts#artwork#artiste#niki de saint phalle#jean tinguely#nouveaux réalistes#photo#photografy#photographers on tumblr#black and white#noir et blanc

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

oo fun

last song: uptown funk by mark ronsin ft bruno mars

fav color: green i love green!!!

last book: bi1 aka my biology textbook💀

last movie: rocketman or descendants 3 (the range wow)

last tv show: voltron!! rewatching

sweet/spicy/savoury: sweet easy

relationship status: single/doomed

last thing i googled: i think ao3 klance💀

current obsession: voltron lessgo🔥

looking forward to: the sweet release of death. and christmas maybe

anyone can join :- )

Ten people I’d like to know tag game:

Thanks for the tag @beauty-is-terrror

Last song: Swan Upon Leda by Hozier

Favourite colour(s): dark greens, navy blue, browns

Last book: reread Bacchae and other plays by Euripides

Last movie: Brideshead revisited

Last TV show: I don’t watch them

Sweet/spicy/savoury: savoury

Relationship status: cursed

Last thing I googled: name of the newspaper in my country

Current obsession: ovid

Looking forward to: Going to Switzerland next week

Tagging: @shinaaposts @siriuslyobsessedwithfiction @perpulchra @the-etcetera-archive (no pressure and sorry if anyone has been tagged before)

363 notes

·

View notes

Text

Year II, 3rd of Germinal

It is to you, citizens, that I address myself to introduce myself, answer your questions, and justify my actions on the eve of my execution. We are to be executed by all those men worn out by the Republic, who accuse us of being extremists because we are patriots, while they no longer wish to be patriots themselves, if they ever were. We have been accused of counter-revolution, of planning a "foreign plot" to overthrow the Revolutionary Government and replace it with a military dictatorship, and of sabotaging food supplies. There are even false rumors that I had a stash of 190,000 livres in cash that disappeared during the search on the 24th of Ventôse. I can assure you, citizens, that all my possessions, apart from some press clippings, were devoted to the revolution. When the commissioners visit my virtuous mother, they will find only 26 livres, 17 sols, 460 assignats, and a golden ring.

Throughout the revolution, I have been sensitive to the sufferings of the people, and I would never have committed such barbarism as cutting off supplies. I am not a counter-revolutionary, for I have given all my strength to the revolution.

This is the end, and the 18 of us are preparing to die as we should. The brave citizen and General Ronsin was right when he told us, "You will be condemned. When you should have acted, you spoke. Know how to die. As for me, I swear you will not see me falter. Try to do the same." This is entirely true—just a few days ago, we should have better prepared the attempt at insurrection to alleviate the sufferings of the Parisian people. Now, the only right thing to do is to honor the people by dying as we should.

Citizen Vincent, who helped us greatly during his time at the Ministry of War, seems lost but quite calm, even Citizen Cloots, who aside from assisting us in our campaigns of de-Christianization, has little in common with us, shows immense courage. He has volunteered to be executed last to spare us unnecessary suffering. Apart from the wretched Jean-Baptiste Laboureau, the so-called "miracle survivor," who has accused us heavily, this proves that fraternity is still alive in our group of condemned men. Only Citizen Hébert has lost his composure over the past days.

I understand well that his wife has been arrested, and that this causes him great pain—my own, the virtuous, courageous, and Republican Sophie, has also been arrested. But the only comfort he can now offer his wife is to die with dignity, as he proclaimed he would be ready to do just a few days after the martyr of liberty, Marat, was cowardly assassinated.

I have sent a letter to my wife, asking her to remain steadfast in Republican virtues. If she survives, and I hope with all my heart that she does, I know she will raise my son to be an honest and worthy citizen. I know that, due to the confiscations of the little I possess, her life will be very difficult. But I trust her; her courage and virtues are great enough to overcome obstacles. I hope my mother will be as strong as my wife and will find comfort in visiting my son. But I am at peace because my patriotism has always been pure, and Marat has taught me how to endure suffering.

Enough about me. It is to you, the hope of the Republic, that I speak. We began the fight for the revolution, but there is still so much to do, for the sufferings of the people remain so numerous. We made mistakes, such as poorly preparing this insurrection intended to ease the sufferings of the virtuous people. There are still many enemies of liberty. The widows and orphans of the fighters for freedom still suffer. We must think of a plan for greater social sharing. Only then will the Declaration of the Rights of Man be respected.

It is up to you to continue the fight. I will try to answer your questions or objections as best I can.

Hail to the Republicans! The only legacy I leave you is my virtue.

Liberty Equality Fraternity or Death

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Cordeliers Club (J. Guilhaumou)

The Cordeliers Club « is more famous than known » : with these words, the historian Albert Mathiez defined the major difficulty of every overview on the club, within whose history entire sections, for lack of sources or studies, remain obscure.

It is highly probable that the club already existed in April 1790 under the title �� club of the rights of man ». It appeared under its full name Society of the friends of the rights of man and of the citizen in June 1790. An address of the Cordeliers of the same year proclaims that the patriots have to devote themselves « to the defence of the victims of suppression and to the relief of the unfortunate », and, in this capacity, adopted the eye, a symbol of surveillance, as the seal of the society. In the beginning, the club held its sessions in a room of the Cordeliers Convent. Being persecuted by the municipality, the Cordeliers ended up settling in the locale of the Musée, Hôtel de Genlis, Rue Dauphine, where they would remain throughout their existence.

Under the auspice of the rights of man and of the citizen, displayed behind the president in the debate room, the club presented a particular physiognomy. It thereby clearly distinguished itself from the Jacobin Club on the various levels of its existence : local (around the section of the Théâtre-Français), regional (in Paris) and national (in 1793). The Jacobins endeavoured to follow the initiatives of the National Assembly as closely as possible and to form a network of affiliated societies which would reverberate and enrich their propositions. The Cordeliers favoured their mission of surveillance and of control towards the constituted authorities. This is why they admitted women to their society, as well as passive citizens. A. Mathiez could say that they formed « a group of action and combat » that was always in a state of alert when it was a matter of reacting to breaches of the rights of man. Thus, the club was a favoured place of encounters, of exchanges between spokespersons, hommes de liaison, commissioners and other political mediators who wanted to apply the avowed droit naturel, the Constitution.

The club owes its first success, in 1791, to the federation which it established with the fraternal societies, which originally have been formed in its wake. Marat, a Cordelier par excellence, received the title « father of the fraternal societies ». Numerous revolutionary personalities frequented the club, although it is not possible to point out a leader : Danton, Hébert, Vincent, Rutledge, Legendre, Marat, Lebois, Chaumette, etc.

Increasingly critical towards the executive power, the club took the helm, during the spring of 1791, of the democratic movement in favour of the establishment of the Republic. After the king's flight, and in the moment of the composition of the Champ de Mars petition, the Cordeliers defined their principal and permanent objective : it was necessary to « proceed to the replacement and the organisation of a new executive power ». In the aftermath of the Champ de Mars Massacre (17 July 1791), due to repression and internal divisions, the club was weakened. It recovered its strength, in 1792, through the mediation of the network which it had built with the popular societies of the provinces. Thus, it would serve as the voice of the fédérés of 10 August and play a non-negligible role in the proceeding of the insurrection against the king. The position of the Cordeliers was consolidated during the winter of 1792-1793, at the time where the Jacobins collided with the Enragés. The growing importance of figures such as Hébert, the Père Duchesne, and Marat assured them a certain renown. But the club only reached a national dimension at the end of the insurrection of 31 May, 1 and June. Around it, several institutions gathered : the revolutionary committees of the sans-culotte sections, the Ministry of War where Vincent cut his teeth, the Commune of Paris and, of course, the popular societies. During the summer of 1793, the club conquered, with the help of the delegates for the festival of 10 August, a hegemonic position within the Jacobin movement. One can speak, at that time, of the Cordelier or « Hébertist » movement (A. Mathiez). Hébert, in Le Père Duchesne, defined the watchwords of the revolutionary movement. Vincent, for his part, explained his project for the organisation of the executive power at the club. The Cordeliers distanced themselves from the sans-culotte movement through their refusal of direct democracy. The Cordelier programme began to be realised, particularly in Marseille, by the assembly of the popular societies' central committees. But the Robespierrist Jacobins, partisans of « legislative centrality », were determined to put an end to the Cordelier offensive. In spite of their victory during the revolutionary journées of 4 and 5 September, which brought about the creation of the revolutionary army and the mise à l'ordre du jour of the Terror, the Cordeliers were attacked at the Jacobin Club by Robespierre and Coupé de l'Oise, at the National Convention by Billaud-Varenne during the second fortnight of September. Then began a series of skirmishes which resulted in the arrest of Vincent and Ronsin (17 December 1793). In the provinces, the representatives en mission, denounced by the Cordeliers, forced the central committees to dissolve.

In early 1794, the club turned back into a district club, influential in some sections, and closer to the demands of the Parisian popular movement. Now, what about the famous « Cordelier insurrection » of Ventôse, Year II? It was in fact a matter of political « manipulation » that was arranged by the Montagnards in order to deliver a first blow to the popular movement. The journalists, interpreting Hébert's moral call to insurrection in a political sense, strongly contributed to such a manipulation. It was their revenge against the Père Duchesne! After the arrest and execution (14 and 24 March 1794) of the Cordelier « leaders », the club, even after having been purified, ceased to gather permanently.

Source: Dictionnaire historique de la Révolution française (Albert Soboul)

#French Revolution#frev#cordeliers#club des cordeliers#translation#hébert#Danton#ronsin#vincent#marat#legendre#chaumette#dhcordeliers#jacques guilhaumou

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

Magic sword, magic hair (Roger Ronsin, Rêve de Dragon 1e, Nouvelles Éditions Fantastique, 1985)

#Reve de Dragon#Roger Ronsin#JDR#jeu de role#Rêve de Dragon#jeu de rôle#fantasy RPG#magic sword#big hair#1980s#magic#Nouvelles Editions Fantastique

134 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hello! I don't want to interrupt your debate, both of you knew the subject very well (or so it seems). I don't know Junot at all, so I won't comment. But if I may just bounce back on a sentence: "I do not know of any other popular Napoleonic general or marshal who tried to kill his wife in a fit of jealousy. Junot seems to be special in that regard" Well, somewhere another one almost did (even if some might call it involuntary manslaughter), even if fortunately it didn't happen like that. I present General Turreau who worked under Napoleon. He remarried the widow Ronsin and apparently he whipped her in public (yes it is dangerous and deadly). According to the correspondence of Madison Dolley, great friend of Marie Angelique Lequesne (widow Ronsin and wife Turreau). He often mistreated her which is an understatement (I imagine out of jealousy also according to Madison Dolley, his wife charmed the political class where he was not so popular among other things for his conduct in Vendée without counting his character; but hey with Turreau any pretext would have been enough). I was going to talk about it in a post this week but one day when many people did not dare to confront Turreau when he was a diplomat in the United States on his behavior, he started to whip her again without stopping (he could have killed her it is medically proven with the risk of infection without counting that after a certain number of blows). A man Dr. Thornton a magistrate had the doors forced and intervened in front of him, had it stopped and told him what he really thought. Without that… Who knows maybe she could have died.

Source:

Letter of Dolley Madison

https://www.jstor.org/stable/1923081

57 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Niki de Saint-Phalle, Shooting Impasse Ronsin, 1961

8 notes

·

View notes