#Robert kett

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

ON THIS DAY - 07 December 1549

On This Day (07 Dec) in 1549, Robert Kett, the leader of 'Kett's Rebellion', and his brother William Kett were executed in Norfolk.

In the summer of 1549, local peasants and farmers, in response to land enclosures, which had led to eviction from land and property and a monopoly on land by a small number of owners, started to revolt. They were led by Robert Kett, a wealthy Norwich multi-generational farmer. One of the first targeted landowners was Sir John Flowerdew, brother-in-law of 17yo Amy Robsart.

An army of 1400 men was sent by Edward Seymour, Edward VI's Lord Protector, led by William Parr, Marquess of Northampton, to quell in Jul 1549, but had been defeated, with the rebels were gaining increasing local support. In Aug 1549, further military support of 14000 men, led by John Dudley, Earl of Warwick, was therefore sent to Norfolk.

Dudley took with him two of his sons, Ambrose and Robert, this being their first exposure of 'warfare'. On their arrival in Norfolk, Dudley and his sons lodged at the home of Sir John Robsart (another targeted landowner) in Wymondham, with the army encamped on his lands. Joined by Northampton, Dudley and his army entered Norwich on 24 Aug, and fighting took place over the next few days, culminating in the final battle on 27 Aug, where 3000 rebels lost their lives.

In the immediate aftermath of the rebellion, captured prisoners were tried and executed; it was said that 49 prisoners were hanged at Norwich. However, around the same amount were released and pardoned the following year.

Following their arrests, the Kett brothers were taken to London, and held at the Tower of London. They stood trial at Westminster Hall on 26 Nov 1549, where they were found guilty of treason, by inciting 'sedition, rebellion, and insurrection' and were sentenced to death. They were consequently returned to Norfolk for their sentences to be carried out. On 07 Dec, Robert was hanged by chains from the side of Norwich Castle, whilst William was hanged from the west tower of Wymondham Abbey.

#tudor england#tudor history#history#tudor people#tudors#tudor#robert dudley#Ambrose dudley#John dudley#Amy robsart#John robsart#John flowerdew#Robert kett#William kett#norwich#norfolk#wymondham#Kett's rebellion

7 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

The Ballad of Kett's Rebellion

#youtube#1549#Robert Kett#boris johnson#nadine dorries#jacob rees-mogg#Edward VI#protector somerset#Norfolk#Norwich Castle#mousehold heath

0 notes

Note

How'd Eva view the Puritans and the general chaos of the 1600s in England? How would she react if America was found/raised in the New England Puritan colonies or in the interim absorbed their more radical teachings?

I would say read Chapters 1-3 of my fic hoho (silly plug). She was suspicious at first, and by the 1660, she held nothing but contempt for them. She likes to have fun at this point in her life. She likes to dance, to drink, to go horse-riding and shooting (arrows or guns), to play cards, to eat lots of rich and fancy foods and sweets, to grow her weird herb garden and cook with them in her weird bubbling cauldron (not suspicious...) and she doesn't see anything morally wrong with any of it. Nothing gets her hackles up then people getting in her private sphere and telling her what to do.

Alfred was found and brought to England before Jamestown and got very sick, so when Jamestown was properly settled, he was sent back with Evelyn intermittently spending time out there with him, or bringing him back to England for small periods too. She keeps him in Virginia for as long as she can.

When her Civil War begins, she gets her brother to go over and move Alfred to Maryland, which was experimenting with religious toleration for Catholics. After the wars end and Charles II has his bum on the throne, Evelyn is with Alfred always. No more weeks where she is in England and he in the colonies. She is glued to his side until the 1690s. They go to Providence (a tolerant colony for Protestants this time) or Philadelphia (Quaker haven), with the occasional stint in Williamsburg back in Virginia after Jamestown is abandoned.

As she was pretty much indisposed for the entirety of the Civil War and a good chunk of the Interregnum, she loses control over his wellbeing. Because the vast majority of the American colonies had declared for Charles II over Parliament save New England, and because she was locked up for a few years, Cromwell moved Alfred up to Boston. Alfred went willingly because the men who came to him said his mum had sent them, and at this time Alfred's only like five or six. He misses his mum, he'll and will do pretty much anything if he thinks it will make her happy or come home. He was away from her between 1639 and 1655. Over fifteen years without his mother. That's not good for a little one to not have a steady caretaker with them. I think it really messed him up, even more so cause he's stuck with puritans (worse - American puritans, the ones who thought Cromwell was being too tolerant).

Moving from St. Mary's to Boston would have been a shock to his system, but Alfred thought it was what his mum wanted, so he listened and tried to learn. It's why he's so confused by the end of the century because he thought she was the one who had ordered him to Massachusetts. Meanwhile, the thing that actually made her get up and fight her way out of gaol was being told Alfred had been moved.

Like, imagine being a parent and thinking, even though you miss your child, you know they're safe, maybe even with a family you trust, only to be told, no, actually, they're with the very people who you were trying to shield them from. Like she really did not give two shits that she had been whipped to death the previous week, she did care of the thought of Alfred being stripped of everything that made him warm and sweet and loving and made to carry a guilt of just being alive and sins that were not his.

She took that rusted nail, stabbed her guard, jumped in the moat and through to the river, stole a horse and rode down to Cornwall before the day was out. She books it to Falmouth, has a rough ride over the Atlantic, maybe falls overboard because docking is taking too long, and washes up on shore to get to Alfred. He runs right into her sopping wet arms and does not let go for days. She probably immediately keels over and dies for five minutes from exhaustion but shh don't tell Alfred that she's just napping.

Eva immediately punts them down to Providence and then it's let's never talk about that again. I think it takes a long time for Alfred to properly digest those years.

Evelyn does not like Puritans. She does not like Calvinism or her brother's Presbyterianism. She will not be hauled up in front of a congregation and lectured for playing cards and walking unaccompanied through town unmarried, nor will she listen to anything which states that her people are damned regardless of their actions and that any form of redemption is a fool's errand (projecting). She's too vain, and is a big believer in being left the fuck alone. What she does is between her and God. No middle man - Saint or Elder - required. So, she's certainly not Catholic anymore either.

She likes Quakers, does not mind Lutherans or Methodists, and is indifferent to Catholicism so long as she isn't made to be one, enough to let Matthew practice how he wants in private, and she herself is - rather reluctantly and mainly out of habit rather than genuine belief - High Church Anglican. She'd never admit it, but she likes the idolatry and superstition that reformers railed over. Makes it rather fun. From my understanding, I think most American churches, the dozens of splinter baptist/reformed/evangelical churches etc. tend to be low church? Or is that an oversimplification maybe. Probably. But I can see how, even to the modern day where maybe Alfred and Evelyn themselves aren't like particularly religious in their day to day lives, the impact of that split is still felt.

Nations and religiosity is an interesting topic, but I really only know so much about Anglo-Scottish religious development to comment on nationhood as a whole, and the world is so much bigger than two thirds of a damp island 🫡😅

The 'problem' with the English Reformation compared to many German states or across the border in Scotland is that it was so deeply led from the top down by a 'secular' monarch and nobility and not particularly by the actual clergy. Thomas Cranmer was put in place by those in power because he promised to get a task done for Henry (marriage annulment) and used the opportunity for his own ends. Meanwhile John Knox across the border was running around converting the Scottish nobility onside with one notable exception (the monarch, but to be fair she was like 14 and in France and we all know how well it went when she came back), if that distinction makes sense.

And I think, because the English Reformation was done for such selfish reasons primarily, then ecclesiastical ones second, things like the dissolution of the monasteries, the suppression of Cornish as a language, the taking over of the Common Land all spiral out from it. From Cornwall to Oxfordshire to Yorkshire to Norfolk to the Lake District, the people on the ground were protesting this hard only to be slaughtered by the thousands.

I think Evelyn would have exited her reformation incredibly jaded. Like of course the Catholic Church was (is) broken. What spilled out of it in England was equally so. I think Evelyn wanted to protect Alfred from that, but in many ways he was impacted by those splinters just as much as she was. It's just another one of her poisons which leaked out its container. English conflicts never have the courtesy to stay in England, it always has to be someone else's problem too. So guilt, mostly, to answer your question. She would blame others, of course, but also blame herself a lot. If she was just a better person, Alfred wouldn't have suffered needlessly.

#q&a#it's sort of related but the plaque at Norwich Castle commemorating Robert Kett & the rebellion I think has perfect wording - it says:#'this memorial was placed here by the citizens of Norwich in reparation & honour to a notable & courageous leader'#'in the long struggle of the common people of England to escape from a servile life into the freedom of just conditions'#like bruh we're *still* trying 500 years later#hetalia#hws england#fem!england#hws america#headcanon#fanfic ask#historical hetalia

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

30-second book review: Tombland, CJ Sansom

DOES ANYONE HERE LIKE A DOOMED POPULAR REVOLT WITH A CHARISMATIC LEADER? IT'S EVEN IN NORFOLK.

CJ Sansom! Using his law degree and his public school trauma to create a brilliant portrayal of what it might have been like to be someone with a legal career, good intentions, and a survival instinct trying to exist in the constant fuckery of Tudor England! I listened to alllll the Shardlake books in 2024/early 2025 and I regret nothing.

Tombland is all about the revolt of Robert Kett in the reign of Edward VI which is very likely not something you have learned about! But we are going to go into the deep-rooted economic malaises and exploitation of the peasantry! We are gonna explore their demands and manifestos! We are going to question the social order and its theological underpinnings and what revolutionary justice might look like! AND WE ARE GOING TO SOLVE A MURDER. (and cry a lot by the end of the book). For all my capslock, while there are a lot of people in Tombland who are just....the worst (and every possible content warning), there's also a lot of thorny moral dilemmas and complexities to the situations Shardlake finds himself in, and the length of the book means that you can really get into those. If you read this, read the other Shardlake books first! Which are often less grim! But sometimes it's peasant revolt time and you have to respect that.

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

no you DON’T GET IT, you don’t understand, the homoerotic undertones through the shardlake books need to be translated properly into the tv series for my mental health

“kit, what homoerotic undertones-” matthew repeatedly calls jack’s lips “sensual”. he spends a long time describing his physical appearance and doesn’t do that for most other characters. his internal monologue about gabriel from dissolution. how you can read certain undertones in how he talks about some men who have positions of power over him. how talks about robert kett in tombland. other characters remark that they think/thought he’s gay and he isn’t offended by it. (you can read asexual undertones in his character through his internal monologues and thought processes too)

i NEED THAT to translate to the tv series!!! it’s so intrinsic to the series (you might think i’m joking but i’m not) and i’m going to be so annoyed if it gets lost on the way

#LOOK I NEED THAT TO COME ACROSS PROPERLY ALRIGHT??#it means so much to me#shardlake#shardlake series#matthew shardlake

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Becoming Elizabeth - Starz - June 12, 2022 - August 7, 2022

Historical Drama (8 Episodes)

Running Time: 60 minutes

Stars:

Alicia von Rittberg as Elizabeth Tudor

Romola Garai as Mary Tudor

Jessica Raine as Catherine Parr

Tom Cullen as Thomas Seymour

Bella Ramsey as Jane Grey

Jamie Parker as John Dudley, 1st Duke of Northumberland

Oliver Zetterström as King Edward VI

John Heffernan as Edward Seymour, 1st Duke of Somerset

Jamie Blackley as Lord Robert Dudley

Jacob Avery as Lord Guildford Dudley

Alexandra Gilbreath as Kat Ashley

Leo Bill as Henry Grey

Ekow Quartey as Pedro

Alex Macqueen as Stephen Gardiner

Olivier Huband as Ambassador Guzman

Robert Whitelock as Robert Kett

Ruby Ashbourne Serkis as Amy Robsart

#Becoming Elizabeth#TV#Starz#Historical Drama#2022#2000's#Alicia von Rittberg#Ramola Garai#Jessica Raine#Tom Cullen#Bella Ramsey#Jamie Parker#Oliver Zetterstrom#John Hefferman

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

La lucha de clases contra el capitalismo comenzó con una rebelión en el campo inglés

Por Martin Empson

Fuentes: Jacobin

Los orígenes del capitalismo descansan en la transformación de la agricultura inglesa a partir del siglo XVI. Las primeras etapas de este proceso provocaron una enorme oleada de descontento social, iniciando una tradición de resistencia a la dominación de clase que aún perdura.

En 1549, la clase dirigente inglesa se enfrentaba a una época de crisis. El rey Enrique VIII había muerto dos años antes. Su heredero, Eduardo VI, apenas tenía doce años, y un consejo dominado por el Lord Protector, el duque de Somerset, gobernaba el país. El propio país estaba sumido en el caos. Los efectos de la Reforma seguían haciéndose sentir, y los cambios económicos causaban empobrecimiento y descontento entre los campesinos y los pequeños productores agrarios.

El descontento en la base de la sociedad y la falta de un liderazgo coherente en la cúpula crearon una olla a presión que estalló en 1549. Ese año, decenas de miles de ciudadanos de a pie se rebelaron. La Rebelión de Kett en Norfolk fue una de esas revueltas, impulsadas por una oleada de descontento popular producto de la honda transformación que estaba experimentando la sociedad rural, que acabaría convirtiendo a Inglaterra en la primera nación capitalista del mundo.

Los rebeldes de Norfolk y otras comunidades inglesas fueron finalmente derrotados por la fuerza bruta, despejando el camino para el desarrollo del capitalismo durante los siglos siguientes. Pero sus luchas y las reivindicaciones que expresaron forman parte de una tradición popular de resistencia a la dominación de clase que perdura hasta nuestros días.

Un año de rebelión

En otras partes de Inglaterra, las protestas contra la introducción de un nuevo libro de oraciones protestante desataron la rebelión. En Devon y Cornualles, miles de rebeldes libraron batallas campales contra ejércitos mercenarios enviados por el Lord Protector. En su reciente historia de esta revuelta, el historiador Mark Stoyle ha destacado la magnitud de este «Alzamiento del Oeste», señalando que estuvo a punto de poner el mundo de los Tudor «patas arriba».

Por si esto no fuera suficiente para el consejo del rey, también se produjeron numerosas rebeliones locales. Un estudio ha sugerido que, además de Devon y Cornualles, otros veinticinco condados fueron escenario de levantamientos, rebeliones y protestas. En muchos casos, estas rebeliones solo fueron sofocadas mediante una feroz represión.

Como indica Stoyle, estas rebeliones ejercieron una enorme presión sobre la clase dirigente inglesa. En muchos lugares, los rebeldes levantaron «campamentos» de protesta donde esperaban obligar a las autoridades locales a ofrecer reformas. Si estos rebeldes se hubieran unido y marchado sobre Londres, como pretendían los líderes de Cornualles y Devon, bien podrían haber reunido fuerzas mayores y provocado un levantamiento generalizado que hubiera llevado a la caída del gobierno.

Esa hipótesis no es una especulación vana: protestas similares, como la Revuelta de los Campesinos de 1381 y la Rebelión de Jack Cade de 1450, estuvieron a punto de desembocar en un desenlace semejante. Sin embargo, las rebeliones de 1549 tendieron a localizarse y el gobierno pudo derrotarlas, aunque no sin dificultades.

La rebelión de Kett

El mayor desafío al gobierno de los Tudor vino de Norfolk, donde el verano de 1549 estalló la Rebelión de Kett. El nombre deriva de los líderes de la revuelta, los hermanos Robert y William Kett. Los Kett eran terratenientes locales del pueblo de Wymondham, a unos quince kilómetros de Norwich. En julio de ese año, el pueblo celebró su feria anual, a la que acudió gente de todo Norfolk para disfrutar de un festival que se convirtió en un foco de descontento por los cercamientos. Al día siguiente, los habitantes de Wymondham empezaron a derribar vallas y setos.

Robert Kett, cuyas vallas habían sido los objetivos iniciales, se puso a la cabeza del movimiento y alentó la destrucción de setos propiedad de otros terratenientes. La confianza y el número de manifestantes aumentaron, y el movimiento de protesta llegó a involucrar a miles de personas. Pocos días después, la protesta se había convertido en una rebelión que marchaba hacia Norwich.

Norwich, la ciudad más grande de Norfolk, era una de las más ricas del país, ya que se había enriquecido con el comercio del paño y la lana. El cercamiento de las tierras comunales para la cría de ovejas era una importante fuente de descontento para el pueblo inglés. Sin embargo, la economía de Norwich estaba en mal estado en 1549. La pobreza y el desempleo eran elevados, y la población urbana tenía una gran afinidad con los rebeldes rurales que se reunían a las afueras de la ciudad.

Tras varios días de marcha y destrucción, los rebeldes acamparon en Mousehold Heath, a las afueras de Norwich, donde las señales de fuego y las campanas atrajeron a más rebeldes al campamento. En su apogeo, el campamento rebelde llegó a albergar hasta dieciséis mil rebeldes.

Un mundo alegre

Los rebeldes de Norfolk se dispusieron a construir un marco democrático para garantizar que su movimiento estuviera bien organizado y disciplinado. Kett copió conscientemente las estructuras del Estado inglés existente para legitimar la rebelión. Reunidos bajo un árbol conocido como el «Roble de la Reforma», el movimiento resolvía los desacuerdos y planificaba la rebelión.

El campamento también tenía una estructura democrática. Cada «hundred» de Norfolk —el nombre de una zona administrativa inglesa— podía elegir a dos diputados para el consejo rebelde. Este consejo emitía «órdenes» de rebelión en nombre del rey. Una de ellas decía lo siguiente:

Nosotros, los amigos y lugartenientes del Rey, concedemos licencia a todos los hombres para proveer y traer al campamento de Mousehold todo tipo de ganado y provisiones de víveres, en cualquier lugar que puedan encontrarlos, para que no se haga violencia o daño a ningún hombre honesto o pobre.

El historiador Julian Cornwall informa en su relato de la rebelión de Kett que «tres mil bueyes y veinte mil ovejas, por no hablar de cerdos, aves, ciervos, cisnes y miles de fanegas de maíz», fueron llevados al campamento. Era una rebelión con apoyo masivo. El levantamiento también transformó a quienes se unieron a él. A pesar de la represión posterior, muchos recordaban la época con cariño. Como recordaba un superviviente años después: «El mundo era muy bonito cuando estábamos allí comiendo cordero».

Con estas estructuras como marco, los rebeldes elaboraron una lista de veintinueve reivindicaciones conocidas como los Artículos de Mousehold, que explicaban sus quejas. A diferencia de las reivindicaciones predominantemente religiosas de los rebeldes de Cornualles y Devon, estas estaban relacionadas con las condiciones del campo de Norfolk. El historiador Andy Wood considera que los artículos reflejaban el deseo popular de «limitar el poder de la alta burguesía, excluirla del mundo de la aldea, constreñir el rápido cambio económico, impedir la sobreexplotación de los recursos comunales y remodelar los valores del clero».

Los rebeldes querían que los pescadores y los productores agrícolas recibieran «todos los beneficios» de su trabajo, y su plataforma incluía demandas de protección de rentas y precios, así como límites a nuevos cercamientos. Un artículo pedía la aprobación de una ley que impidiera que «los señores de cualquier señorío» pudieran «comprar tierras libremente y volver a arrendarlas». Otro pedía que los ríos fueran «libres y comunes a todos los hombres para la pesca y el paso».

También se pedía que «todos los siervos» fueran libres e incluso que a los que se unieran a la protesta se les pagaran cuatro peniques al día por sus acciones. Los artículos relativos al clero ponen de manifiesto el deseo de la gente común de controlar su propia comunidad: querían, por ejemplo, poder elegir a otro sacerdote si el existente resultaba inadecuado.

Gaviotas codiciosas

Los Artículos de Mousehold ofrecen una visión fascinante de las esperanzas de los plebeyos en una época de grandes cambios en las comunidades rurales. En su forma más básica, demostraban las tensiones inherentes a una sociedad desgarrada por las divisiones de clase, en la que los más ricos podían remodelar el propio paisaje para aumentar sus ingresos mientras que los más pobres se encontraban a la entera disposición de sus «superiores». Los artículos mostraban que la gente corriente quería tener voz y voto en la organización de sus comunidades, en su instrucción religiosa y en el uso de los recursos naturales.

Los grandes cambios agrarios que se estaban produciendo en Inglaterra, en los que el campo se cercaba cada vez más en beneficio de los ricos, fueron una fuente de inspiración especial para los artículos. El cercamiento de la tierra, la incorporación de los campos a explotaciones agrícolas cada vez mayores y la destrucción de las tierras comunales formaban parte de una transformación agraria que surgió del desarrollo de las relaciones capitalistas en el campo.

La clase dirigente inglesa era dolorosamente consciente de que estos cambios estaban generando descontento. En 1550, un año después de las rebeliones, el escritor y poeta Robert Crowley expuso lo que, en su opinión, eran las causas de la «sedición». Argumentó que un hombre pobre señalaría con el dedo a

los grandes granjeros, los ganaderos, los ricos carniceros, los hombres de leyes, los mercaderes, los caballeros, los señores… hombres que no tienen nombre porque son hacedores en todas las cosas en las que cualquiera pone sus manos. Hombres sin conciencia. Hombres completamente vacíos del temor de Dios. ¡Sí, hombres que viven como si Dios no existiera! Hombres que lo tendrían todo en sus manos; hombres que no dejarían nada para los demás; hombres que estarían solos en la tierra; hombres que nunca estarían satisfechos. Cormoranes, gaviotas codiciosas; sí, hombres que devorarían a hombres, mujeres y niños son las causas de la sedición. Toman nuestras casas por encima de nuestras cabezas, compran nuestros terrenos de nuestras manos, aumentan nuestros alquileres, imponen multas (sí, irrazonables), ¡cercan nuestros bienes comunes!

Las palabras puestas en boca de un «pobre hombre» por Crowley iban dirigidas a una nueva clase de individuos en la sociedad inglesa. Estas «gaviotas codiciosas» tenían intereses económicos que los llevaban a considerar la tierra y las personas como meros objetos para la búsqueda de la creación ilimitada de riqueza. Al esculpir el campo para maximizar los beneficios —especialmente reemplazando la agricultura campesina por la cría de ovejas—, estaban dando prioridad a su propia acumulación de riquezas. Los pobres que fueron expulsados de la tierra por este proceso lo perdieron todo.

Desde distintos lugares de la escala social, los pobres ingleses y los señores feudales establecidos se opusieron a esta mentalidad capitalista emergente. En 1548, el consejo de Eduardo emitió una proclama condenando los cercamientos y nombró una comisión para estudiar el estado del campo. Somerset y los demás miembros gobernantes del consejo comprendieron que los cercamientos socavaban su propio gobierno al eliminar la base del poder feudal.

Al utilizar aquí la palabra «capitalista», no estoy sugiriendo que el capitalismo ya hubiera llegado a Inglaterra. Más bien, lo que estoy describiendo son los inicios del proceso que finalmente vio la transformación de la economía de Inglaterra del feudalismo al capitalismo. No obstante, estos cambios habían comenzado, y también había otros indicios de esta transición.

Los cambios religiosos de la Reforma iban unidos a transformaciones económicas. Quienes querían explotar a las personas y la naturaleza sin tener que preocuparse por las restricciones feudales necesitaban una nueva ideología para justificar sus acciones. Las antiguas ideas católicas ya no encajaban con la forma en que querían organizar la sociedad, y las ideas protestantes de la Reforma se adaptaban mejor a su nueva perspectiva.

Este cambio religioso contribuyó a provocar un mayor descontento, al igual que las acciones de los propios reformadores religiosos. Por ejemplo, cuando Enrique VIII disolvió los monasterios, fomentó aún más los cambios locales que empujaban a la sociedad hacia una economía más basada en el mercado, socavando las relaciones sociales y económicas tradicionales.

La derrota de la rebelión

Fue en medio de estos cambios múltiples e interrelacionados en la sociedad inglesa cuando el pueblo llano se rebeló en 1549. Los artículos escritos en Mousehold Heath resumían el descontento de la gente corriente, así como la esperanza de poder forjar su propio futuro. En este sentido, la Rebelión de Kett representaba el deseo de la gente corriente de encontrar su propio camino, independiente de la clase dirigente existente y de las clases mercantiles emergentes.

Pero no fue así. Ese verano había dos centros de poder en Norfolk. Uno estaba dentro de Norwich, donde las autoridades locales luchaban por mantener el control frente a la influencia de los rebeldes. Las autoridades de la ciudad esperaban obtener alivio de Londres si podían alargar las cosas lo más posible, así que negociaron con los rebeldes y les permitieron ir y venir de Mousehold.

Esta tregua incómoda no pudo mantenerse y finalmente se rompió cuando un representante del rey, el York Herald, llegó el domingo 21 de julio y se dirigió al campamento de Mousehold Heath, declarando rebeldes a los residentes al tiempo que les ofrecía el indulto. Esto entusiasmó a algunos de los seguidores de Robert Kett, pero el propio Kett lo vio como una trampa. No estaba dispuesto a aceptar ser etiquetado como rebelde, ya que creía que no habían hecho nada malo: «Los reyes suelen perdonar a los malvados, no a los hombres inocentes y justos».

Al declararlos rebeldes, el York Herald se aseguró de que las fuerzas de Kett quedaran fuera de Norwich, lo que hizo inevitable el conflicto. Al día siguiente del discurso del York Herald, las fuerzas de Kett asaltaron la ciudad, capturándola fácilmente. Esto obligó al consejo a enviar fuerzas militares desde Londres. Sin embargo, los rebeldes derrotaron a esta fuerza relativamente pequeña.

Kett intentó reforzar su posición extendiendo la rebelión por Norfolk, en particular capturando el importante puerto pesquero y comercial de Yarmouth. Este esfuerzo resultó infructuoso, y la derrota en Yarmouth dejó a Kett aislado. El gobierno envió entonces a Norfolk un enorme ejército al mando del conde de Warwick. Una fuerza de hasta catorce mil soldados marchó contra las fuerzas de Kett y se produjeron intensos combates. Tras capturar Norwich, Warwick marchó contra los rebeldes.

Las fuerzas de Kett habían abandonado su campamento y se habían establecido para una defensa final en un lugar llamado Dussindale donde, a pesar de la valiente resistencia, los rebeldes fueron masacrados. Unas 3500 personas murieron. Los hermanos Kett fueron encarcelados en la Torre de Londres a la espera de su ejecución.

El eclipse de Somerset

La rebelión tuvo un epílogo fascinante, ya que a los Kett se les unió finalmente en prisión el duque de Somerset. Somerset ya no era capaz de equilibrar los intereses contrapuestos representados en el consejo de gobierno. El descontento por su gestión de las rebeliones y la creencia generalizada de que había utilizado su posición para llenarse los bolsillos fueron problemas particulares para el duque.

Otro factor clave en la caída de Somerset fue su política agraria, contraria a los cercamientos. A los ojos de muchos terratenientes, esto había alentado las rebeliones. El hecho de que los rebeldes de Kett creyeran que actuaban en nombre del rey indica que había algo de verdad en esta creencia.

Con los terratenientes más ricos en su contra y su posición muy debilitada, Somerset llevó al rey Eduardo a Hampton Court. Desde allí intentó reforzar su posición instando a los Comunes a que se unieran a él y al rey. Aunque en un principio este llamamiento recibió un apoyo entusiasta, finalmente se desvaneció cuando quedó claro que los oponentes de Somerset —entre los que se encontraban el conde de Warwick y lord Russell, que había sofocado la rebelión en Cornualles y Devon— contaban con enormes fuerzas.

Somerset se rindió y fue encarcelado en la Torre de Londres, aunque fue indultado unos meses después. Los Kett no tuvieron tanta suerte. William Kett fue ahorcado en una torre de la abadía de Wymondham. Robert fue arrastrado en una valla por las calles de Norwich y ahorcado en el castillo.

La rebelión en su contexto

Mediante ejecuciones como estas y la represión masiva de los rebeldes en todo el país, la clase dominante inglesa recuperó el control tras el verano de 1549. Los cambios que habían inspirado el gran año de la rebelión no se contuvieron tan fácilmente. Sin embargo, la propia evolución económica estaba desgastando simultáneamente el tipo de unidad popular que permitió a terratenientes como Robert y William Kett liderar a miles de rebeldes más pobres.

A medida que avanzaba el siglo XVI, las crecientes divisiones de clase en el seno de las comunidades rurales ensanchaban aún más la brecha entre ricos y pobres. Los aldeanos más ricos tenían cada vez menos en común con los pobres, lo que hacía más difícil, aunque no imposible, la rebelión. Los grandes cambios en la campiña inglesa culminaron finalmente en la formación de una clase obrera rural con el telón de fondo de un nuevo orden capitalista.

Los detalles de la rebelión de Kett son bien conocidos en parte porque el episodio fue ampliamente documentado por una clase dirigente de Norfolk decidida a utilizar la historia para prevenir a futuros rebeldes. Sin embargo, la historia que solemos escuchar tiende a considerar los acontecimientos de Norfolk aislados de los demás levantamientos de 1549.

Recientemente, los historiadores han dedicado más tiempo a explorar la amplitud de la rebelión en la Inglaterra de la época. Esto nos ayuda a ver que la gente corriente no aceptaba dócilmente los grandes cambios económicos que estaban transformando la sociedad. El desarrollo del capitalismo, con las consecuencias destructivas que acarreó para cientos de miles de trabajadores, fue contestado en cada etapa.

Debemos recordar a los rebeldes de 1549, en Norfolk y en todas partes, como mujeres y hombres que lucharon por controlar sus propias vidas y la comunidad y el entorno en el que existían. Querían una sociedad para todos y no para unos pocos «cormoranes y gaviotas codiciosas». Aunque su lucha fue derrotada, su determinación continúa inspirándonos en nuestras propias luchas por la democracia, la libertad y la liberación.

Martin Empson. Escritor y activista ambientalista socialista, es autor de varios libros, entre los que se cuenta Kill all the Gentlemen: Class Struggle and Change in the English Countryside. Actualmente trabaja en un libro sobre la guerra campesina alemana de 1525.

Traducción: Florencia Oroz

Fuente: https://jacobinlat.com/2025/01/la-lucha-de-clases-contra-el-capitalismo-comenzo-con-una-rebelion-en-el-campo-ingles/

1 note

·

View note

Text

*Auftriebskraftwerk oder Abtriebskraftwerk.* Das Paternoster System von Rosch. Im Jahre 2014 erregte ein neuartiges Auftriebskraftwerk eine hohe Aufmerksamkeit in der Öffentlichkeit. Das Auftriebskraftwerk von Rosch. Es basierte auf einem Paternoster System, das vollständig im Wasser stand und an einer Kette mit Luft gefüllte Auftriebskörper mit sich führte. Diese Behälter wurden an der Unterseite des Paternosters mit Luft befüllt und nach ... …Read more in the original blog (powered by Google Translator!). Klick on the picture now! Don’t miss anything! Find out everything we know! Here! https://geheimnisfreieenergie.de/

#Blogbeiträge_von_gehtanders.de#Dokumentationen#Auftriebskraftwerk#Freie_Energie#Generator#Overunity#Paternoster#Rosch#Schwerkraft

0 notes

Text

"Runaway Lads Face Charges," Border Cities Star. April 19, 1934. Page 5. ---- Housebreaking and Theft Laid to Trio In Sandwich ---- Robert Kett, 17, of 17 Marentette avenue: Roy Gratton, 17 of 425 Huron street, London, and a 15-year-old youth, who fled for the fifth time from the Victoria Industrial School at Mimico, and marked their trail by a series of offences as they made their way to the Border Cities, were in county police court at Sandwich this morning, and remanded for one week by Magistrate Smith.

The youths face charges of a serious nature and have not as yet been asked to enter pleas or make elections. They are charged on eight counts with breaking and entering and theft, two of breaking and entering with intent, and one car theft charge.

The problem of how to dispose of the charges against these youthful offenders is one which Magistrate Smith is pondering.

#windsor#teenage runaways#escaped prisoners#escape from prison#prison break#mimico reformatory#industrial school#county police court#youth detention#breaking and entering#great depression in canada#crime and punishment in canada#history of crime and punishment in canada

0 notes

Text

"Doktor Jekyll & Mister Hyde" ist eine tiefgründige und visuell beeindruckende Neuinterpretation von Robert Louis Stevensons klassischer Erzählung. Verfasst von Jerry Kramsky und illustriert von Lorenzo Mattotti, erforscht diese Graphic Novel das duale Wesen der menschlichen Natur. Dr. Jekyll, ein erfolgreicher Wissenschaftler, wird von der Idee besessen, die guten und bösen Seiten der Menschheit voneinander zu trennen. In einem riskanten Selbstversuch entwickelt er ein Serum, das ihn in Mister Hyde verwandelt, ein Wesen, das seine dunklen und abscheulichen Aspekte verkörpert. Die Verwandlung von Jekyll in Hyde löst eine Kette von Ereignissen aus, die das Leben des Arztes und seiner Umgebung drastisch verändern. Jekyll muss zusehen, wie sein dunkles Alter Ego unvorstellbare Verbrechen begeht, während er zunehmend die Kontrolle über sein eigenes Schicksal verliert. Diese innere Zerrissenheit und der Verlust von Kontrolle stehen im Mittelpunkt der Geschichte und werden durch ausdrucksstarke Zeichnungen hervorgehoben, die die emotionale Tiefe der Charaktere betonen. Lorenzo Mattotti, bekannt für seine kraftvollen Bildkompositionen, setzt auf intensive Farben und eine kühne Ästhetik, die die düsteren und komplexen Themen der Geschichte perfekt einfängt. Seine künstlerische Umsetzung trägt erheblich zur dramatischen Wirkung der Erzählung bei. Jerry Kramsky, der Texter, liefert eine nuancierte Darstellung der inneren und äußeren Konflikte, die Dr. Jekylls Leben bestimmen. "Docteur Jekyll & Mister Hyde" ist mehr als nur eine Adaption des literarischen Klassikers. Es ist eine eigenständige künstlerische Schöpfung, die die zeitlosen Fragen nach Identität, Moral und der Dualität des Menschen auf eine frische und visuell ansprechende Weise erforscht. Die Graphic Novel ist ideal für Leser, die sich für psychologische Dramen und tiefgründige Erzählungen

0 notes

Text

The Marriage of Robert Dudley and Amy Robsart - 04 June 1550

On This Day (04 June) in 1550, Robert Dudley, 3rd surviving son of John Dudley, Earl of Warwick, Lord President of the Regency Council, married Amy Robsart, daughter of Norfolk landowner Sir John Robsart.

In August 1549, Warwick was sent at the head of an army to quell an uprising in Norfolk, known as ‘Kett’s Rebellion’: a revolt headed by yeoman Robert Kett, targeting local landowners. Accompanied by his sons Ambrose and Robert, Warwick headed to Norfolk, where he lodged at the home of Sir John Robsart in Wymondham. This is likely where the young couple first encountered each other.

The uprising was unsuccessful, with the rebellion quashed, many men arrested and the leaders arrested, convicted of high treason and executed. However, Somerset’s mismanagement of the rebellion was one of many factors leading to his forced removal from the Lord Protectorship, and with Warwick emerging as head of the Regency Council in February 1550, in place of his old friend.

In May 1550, a wedding contract was drawn up between the young couple, confirming their intent to marry. However, rather than this being an arranged marriage, as many were of the time, in particular within Warwick’s family, Robert’s marriage to Amy appears to have been a love match: Warwick’s private secretary William Cecil, whom would become one of Robert’s biggest critics on the accession of Elizabeth I and his elevation as her ‘favourite’, described the union as a “carnal marriage”; the almost-18-year-olds appear to have consummated their marriage without delay.

The wedding was held the day after Robert’s elder brother John’s wedding to Anne Seymour, on 04 June 1550; both took place at Richmond Palace, with Edward VI in attendance. Following the exchange of vows, which took place in the chapel, there were further celebrations held, including a banquet. It was said to be less extravagant than that of his elder brother’s, although the king was still said to enjoyed himself.

#tudor england#tudor history#tudor people#history#tudors#tudor#tudor women#robert dudley#Amy Robsart#John Dudley#Edward vi#Richmond palace#Tudor marriage

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

"In 1549 AD Robert Kett yeoman farmer of Wymondham was executed by hanging in this Castle after the defeat of the Norfolk Rebellion of which he was leader. In 1949 AD – four hundred years later – this Memorial was placed here by the citizens of Norwich in reparation and honour to a notable and courageous leader in the long struggle of the common people of England to escape from a servile life into the freedom of just conditions" - Norwich Castle Plaque

#becoming elizabeth#robert kett#elizabeth tudor#mary i tudor#edward vi#history#kett's rebellion#rewatching black sails and remembered this quote#and then quickly remembered how badly BE butchered ketts rebellion#like say what you want about the tudors#at least it highlighted the cruelty of the monarchy and rich#and showed WHY people rebelled and WHY people had enough#anyway when are we gonna get a movie about kett's rebellion

297 notes

·

View notes

Text

things that annoy me bcus i am an annoying person that has a henry viii blog and that for that reason seeing adjacent misinfo swirling online annoys me:

henry was not ‘catholic without the pope’. there literally is no such thing (i realize this makes labels rather difficult, he certainly also was not ‘protestant’, and that weird-religious-hybrid that had not existed before or in since does not go down as easy)

henry did not invest edward seymour as the duke of somerset (nor as the lord protector, for that matter....nor john dudley as that, either...)

it seems highly unlikely that he 'oversaw 72000 executions’. consider why it is that there is such a firm figure floating around for him and not other tudor monarchs. there was no official ‘execution roster’ that included everyone ever executed in england at this time. numbers we have generally come from the executions of religious martyrs (which leaders of catholicism and protestantism had great motives to preserve for posterity), executions of notable figures for treason, and executions as reprisals for rebellions. executions for “petty crimes” or repeat offenses that traditionally took place at tyburn, et al, were not so meticulously preserved.

now that we’re on that topic... there is very little indication that the years anne boleyn was queen were the pinnacle in number of tudor executions, either of her ‘enemies’ or otherwise. let’s break it down by years:

1533-36:

1533: the executions of john frith & andrew hewet (protestant martyrs, but neither here nor there): 2

1534: the executions of elizabeth barton, edward bocking, richard risby (her ‘enemies’, less than was decreed initially, at her behest according to contemporary record): 3

1535: the executions of the carthusian martyrs, thomas more, and john fisher (more arguably in the group of her opponents, although theirs was against the act of supremacy, not succession): 8

total: 13 (yeah, i was surprised, too, considering how vehemently that’s asserted)

1537-40:

john hussey, the earl of kildare+ his five uncles, pilgrimage of grace leaders, catholic martyr john forest, protestant martyrs, carthusians, thomas cromwell, treason offenses, etc.

= rounds up to around forty, likely the number tops out around 100 if you include the reprisal executions of the participants of the pilgrimage of grace, not just its leaders

#the execution one bothers me a lot bcus it's just common sense....#there's so much outrage that there's focus on executions for heresy and essentially averages taken from that (how many over how many years)#but those are the firmest numbers we have? becaus of the above reasons? of course that's what receives the focus#and of course it's used bcus it so reflects the changes in religion/ religious upheaval and to what degree over time#it entirely makes sense to use it as a metric#we go from one person executed for religion in twenty four years (henry the seventh)#to 79 for the same in nearly forty years (henry the 8th)#(estimate...do you count robert aske? etc)#two executed for religion in the six years of edward sixth#287 during the six years of mary's#189 during the 40+ years of elizabeth's#when we talk about statistics of executions for reprisals... it's probably a lot more difficult to ascertain#pilgrimage of grace vs ketts rebellion vs wyatt's rebellion#vs northern uprising#the major ones...#but anyway. for henry viii; it is rather straightforward to tally treason executions; heresy executions; rebellion executions#and it's a large number but it nowhere near approaches 72000. nor the other one that floats around now which is 57000

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Robert wants to say goodbye to Elizabeth before leaving to put down Kett’s Rebellion + Bonus: Guildford risks having more lines but is immediately reprimanded for it. BECOMING ELIZABETH 1.06 WHAT CANNOT BE CURED

#becoming elizabeth#becomingelizabethedit#becoming elizabeth spoilers#perioddramaedit#period drama#weloveperioddrama#perioddramasource#gifshistorical#userperioddrama#userbennet#robert dudley#john dudley#guildford dudley#jamie blackley#jamie parker#jacob avery#tvfilmsource#tvfilmedit#tvfilmgifs#katherynparr#aethelreds#theladyelizabeth#imjustasmith#outrowingss#annabolina#tudorerasource#tudoredit#tudorgifs#dailytudors#gifs: mine

394 notes

·

View notes

Text

okay episode 5 thoughts because what the fuck even was that

- Elizabeth agreeing to marry him, and it actually showing them having sex? that really wasn’t it why would they even do that why did it have to go that far, they could have done the whole thing without having to go that far.

- Elizabeth turning down a foreign match not because of her very famous insistence that she didn’t want to marry but because she wanted to marry Seymour? absolutely not

- Tom Cullen was really good as showing Thomas Seymour’s downward spiral but sorry Tom i need Thomas Seymour’s head on a spike and i need that now. It took two strokes of the axe to get his head off i hope they show them both

- not enough Mary

- poor Edward :( he was so upset over the dog

- Why did they show him almost getting away with it? It was only when he was beating up Robert that he’s caught.

- John Dudley arresting Elizabeth and Kat Ashley was a choice. Where’s Robert Tyrwhitt? maybe it’s for the dramatics for the Robert/Elizabeth storyline maybe there was too many characters who knows

- On a positive i did like that they were beginning to show the start of unrest in Norfolk which is leading to Kett’s Rebellion

#becoming elizabeth#bes#be spoilers#becoming elizabeth spoilers#tw:csa#not as many thoughts this week because i’m just annoyed#Elizabeth I i am so sorry they did this to you#i want reparations

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

OK, look, there are a lot of issues to be had with Becoming Elizabeth but honestly, the problems I've seen were ones I fully expected. The thing with Thomas Seymour, saw it coming a million miles away. I was not shocked, I was disappointed, but I suspected they were going to handle it badly anyway. But the (other) thing that gave me this angry, visceral rage was the Kett's Rebellion subplot. Because the show wants you to think that it was about a poor, illiterate, mindless violent mob of catholic's rebelling against an (imperfect but not "bad") Anglican government, committing atrocities because they were poor, illiterate, violent, stupid peasants who are also Catholics.

The reality is the rebellion was the peasantry rising up in righteous indignation at the abuse of power from landowners cutting off the land from the common people. People couldn't let their animals graze in fields, and families were literally kicked out of their homes. All so rich landowners could close off land to do with what they wanted. With inflation and unemployment on the rise, some landowners also rose the rents of their tenants and wages also dropped. You can't afford to pay my increased rent with your decreased wages? Too bad, get out or I kill you. Everything benefited the rich landowners and they knowingly, intentionally fucked over the poor. Not unlike today!

The government's response to it was swift, violent, and brutal. Maybe 3,000 rebels total were killed to say nothing of the civilian casualties. To add further insult to grievous injury, after the rebellion was quelled it was decreed there would be a national holiday celebrating the rebellion's defeat and lectures were given on the sins of rebelling against your king and government.

I know why they didn't go with this subplot. Because no rich person with power wants the regular, ordinary person to see a rebellion that they can sympathize with and get it in their heads that they can too. Rebellions scare the rich because they know the "poor" outnumber them a million to one. We also live in a modern society where we can think, act, and band together to fight injustice. Why do you think the conservative right wing is so determined to remove as many rights as humanely possible from anyone who isn't exactly like them?

How they chose to portray Kett's rebellion to be as unsympathetic and as inaccurate as possible then turn it around to show how Lord Dudley is a prick while his son Robert can only look dumbfounded when he doesn't show mercy...it doesn't have any impact narratively speaking. We already don't like Lord Dudley. Anyone with a basic knowledge of Tudor history knows he dies. I feel like, a better team of writers could have portrayed the rebellion as sympathetic and Dudley killing the leaders and anyone else tied to it having a stronger emotional impact. There's plenty of material to use to show the divide between Catholics and Protestants.

Hell, go the extra mile and have it narratively tie in with Elizabeth being the victim of a powerful rich man taking advantage of someone who has no support or power of their own. Have her rebel against his attempts to cajole her into a relationship and marriage. My God, the Seymour's ousted her mother and her family from power! She shouldn't want to have anything to do with them!

But no, I guess have it be stupid peasants rebelling as an excuse to murder and steal because poor people are dumb and evil obviously and all non-evangelical Protestant religion makes you evil, and yeah, portray your groomer and abuser as sympathetically as possible.

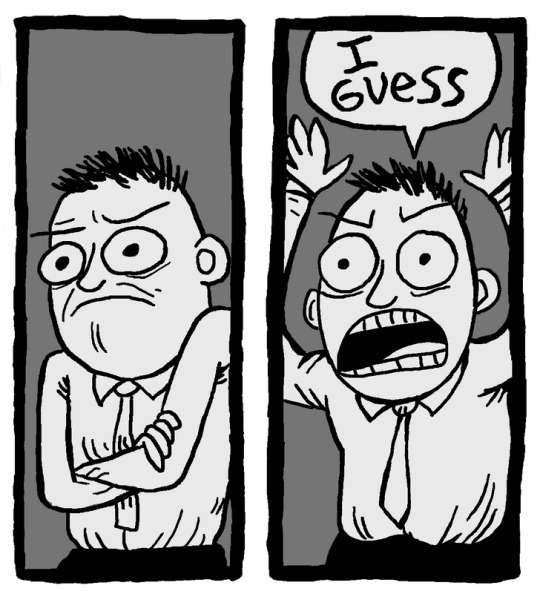

I guess!

#Becoming Elizabeth#Kett's Rebellion#Tudor History#nothing and I mean nothing gets me more viscerally angry then seeing a historical drama purposely change facts to serve a narrative

22 notes

·

View notes