#Poetry translation

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Drink me, burn me, love me (English Translation)

All roads lead to you, even the ones I took to forget you. Because I can deny everything, but not your fragrance when it comes to conquer me. Whoever says you are a crooked creature has not seen your figure, nor your flowing curves. Flowing like a cascade of femininity, and bending me to the edge of insanity. From my eyes, a waterfall, but in my heart, a fire burns. Tell me, do you want a drink or to dance with me in my eternal fire?

✦ @dervishlatino | NNF نشوان نازاريو فيريرا ✦

#poetry translation#poetry#poems#poetic#words words words#original poem#poems and poetry#poems on tumblr#poem#love poem#short poem#my poem#original poetry#original poets on tumblr#spilled ink#spilled poetry#spilled words#prose#spilled thoughts#spilled writing#spilled emotions#spilled feelings#spilled heart#spilled prose#my poetry#words#my words

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

This is entirely copied from my reblog of this post, but I just thought I'd put this in a post of my own for safekeeping on this hellsite or I'd literally never find the translation of Xingnv's Lament I did for this reblog ever again but. Anyway!

Whenever I think about the fact that like, people claim historical people grieved less about child and infant mortality I want to start biting because here's the translation of the Cao Zhi's poem on losing a daughter (yes the Cao Zhi of the infamous bean poem/Seven Step Quatrain fame) written sometime in the 200s AD: 行女哀辞

序:行女生于季秋,而终于首夏。三年之中,二子频丧。 伊上帝之降命,何修短之难哉;或华发以终年,或怀妊而逢灾。 感前哀之未阕,复新殃之重来!方朝华而晚敷,比晨露而先晞。 感逝者之不追,情忽忽而失度。天盖高而无阶,怀此恨其谁诉!

Xingnv's Lament

Preface: My youngest daughter, Xingnv, was born in late autumn and died in early summer of the following year. In just three years, two beloved daughters died one after another. The heavens grant precious life to people, yet why is the length of that life so hard to guess Some people are fortunate to live to old age, others die young in the womb I have yet to finish grieving for Jinhu*, yet I have to see Xingnv** buried in dust This poor child falls like the hibiscus, life drying like the morning dew I thought of that young life that could never return, and lose my normal composure Resenting that the heavens have no stairs for me to climb, to pour out the sorrows of my heart

*Jinhu is the first child that he mentioned

**Xingnv is the daughter he dedicated this poem to

Like! DESPITE what people will tell you people often grieved their children, yes, even daughters which, historical fiction SO often say that fathers hated having Girl Children or whatever. We only know Cao Jinhu and Cao Xingnv's names because their father wrote them down. And grieved their absence.

"Resenting that the heavens have no stairs for me to climb" is SO bleak and so utterly fucking devastating.

121 notes

·

View notes

Text

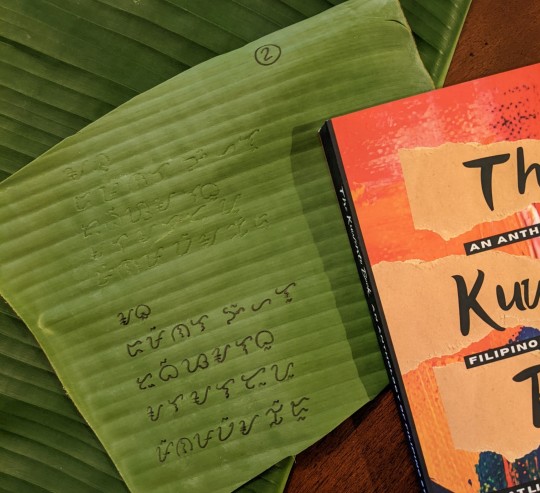

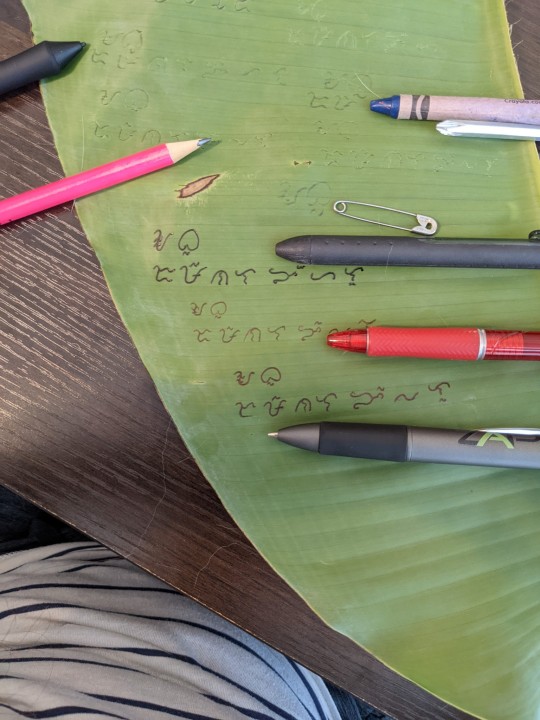

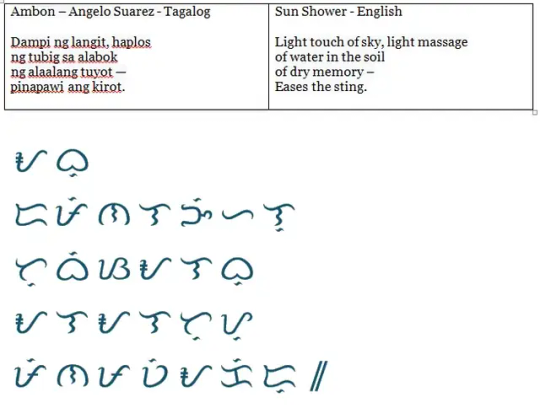

Am I learning baybayin calligraphy to test a book theory for 1 historically accurate throwaway detail in SAINTS OF STORM AND SORROW? 🫣 Maybe?

And maybe I just spent 3 hours collecting banana leaves from a condemned apartment building, finding Tagalog Tanaga poems that fit thematically with my novel, SAINTS OF STORM AND SORROW translating the tagalog into baybayin symbols then testing writing implements and copying out 4 different sheets to be stored in different environments to test the long term legibility of said poems 🤣 that's also possible!

But in my defense nowhere on the internet was willing to tell me more than the Wikipedia single paragraph of yes South East Asia and the Philippines used banana leaves as a writing surface pre-colonization. So really this was for science. I will likely be writing up a full blog post detailing my recent adventure into historical recreation and banana leaves, once I've finished using all my extra banana leaves to make suman 😋

Happy Filipino American History month 🇵🇭

#baybayin#tagalog#filipino#poetry#Filipino history#writeblr#writing research#calligraphy#banana leaves#science#filipino fantasy#filipino author#poetry translation#FAHM

146 notes

·

View notes

Text

A poem that never wished to be written

If you asked it – which is absurd – it wouldn’t say anything or bat its eyelashes in wonder Because eyelashes were attributed to it – long, gently curved, like those from a beauty salon – Nicole Weiß (© 2024) Translated from the German original (which can be found here) by Johannes Beilharz.

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kipling arrives at the sensible anti-Communist position held by all reasonable men from an odd angle: He's apparently in favour of the Czars. I think it's fair to say that this is now an unusual position even among people who would have backed the White armies as a lesser evil against the Red; considered as a regime, Czarist Russia is not recommended by anything in particular except the quality of what overthrew it. Although it is possible that Kipling sees the February Revolution as installing a legitimate constitutional government - who knows, they might even have come around on the issue of retaining a monarch? - while the October Revolution is the one that destroyed Russia entirely; the phrase "'twixt seeding-time and frost" could reasonably match that timeline. That aside, I think Kipling favours a monarch (and hereditary aristocracy) as a stabilising institution, even with a lot of power in a democratic-ish parliament; poems like "The Old Issue" and "McDonough's Song" suggest that he likes checks and balances and also tends to see the polity he was born into as the best-arranged one, as often happens.

There's no obvious connection between the Christmas carol and the poem; perhaps Kipling simply liked the repeated phrase "God rest ye… gentlemen". This was the bottleneck in the translation; I could find no Norwegian verb corresponding to the archaic English "rest ye merry" (note that it's the rest and not the gentlemen who are merry, although in Kipling's version it's presumably the gentlemen who are peaceful), and "gentlemen" is also a difficult one to render into Norwegian, especially with the scansion constraint. I ended up going from verb to noun, "God rest ye" to "God's rest", and once I had that everything else flowed easily.

The images are propaganda and photographs from the Great War and the Russian Civil War, with an occasional nod to Napoleon and WWII. The thing about Kipling's repeated "what next" is, of course, that with respect to Russia he was perfectly correct, as demonstrated by the repeated appearance of Stalin illustrating a text that cannot well have imagined him. Specific comments:

"God rest you" - four images of victory celebrations; presumably premature ones in Kipling's view.

"…in such a trench" - a mass grave, very trench-shaped, at Katyn.

"…to dig a nation's grave" - "The White Army retreats from Rostov".

"…no shadow, sound, or sight" - "The Burning of Moscow".

"…the shadow of a people" - Stalin's face making the cutting edge of a sickle is absolutely chilling.

"…that perish in the field" - "Fleeing Dekulakization".

"…for such a bribe to yield" - the sickle plowing the field is apparently intended as pro-Communist propaganda, but in context I must say I find it rather the opposite.

"…ashes, blood, and earth" - "Decossackization". The Communists do appear to have had a variety of de-somethingizations; Orwell commented on it.

"…shovel and smooth it all" - burial of the Unknown Soldier.

"…a Nation dead" - the graveyard at Verdun, obviously a large part of the reason why Kipling's desired intervention couldn't happen. "Us and what army?", the peaceful gentlemen might reasonably have responded.

"…your good help to fall?" - Finland and the Ukraine, as it turned out.

Guds hvile, godtfolk! Mor eder, la intet gi besvær - men, hatten av en stakket stund. De døde bæres her. Byer, hærer, utenfor alt av tallkunst eller bry og si meg, godtfolk, hva dere tror det jærtegn kan bety?

Bryt her grunn for en sliten rest som ikke holdt sin grunn. Gi dem den hvile de krever mest… og hvem tar neste blund, godtfolk, i slik en grøft sin blund?

Guds fred nu, godtfolk! Hvil her trygt! Men - slipp oss dog forbi. Et land så stort som England var, skal herved settes bi. For den Trone og den Stolthet og den Ære og den Makt - tre hundre år det varte; og tre hundre dagers slakt!

Olje her til en frossen flokk som ligger i grøft og renne. Varm dem, som aldri fikk varme nok… og hva skal brenne nå, godtfolk, på slikt et bål å brenne?

Guds hvile, godtfolk! La Ham eders nattesøvn vel trygge. Av dette rike gjenstår nå ei stemme, syn, eller skygge. Unntagen de som gråter, og lys av brann og fyr; og skyggen av det folket som trampes ned i myr.

Bryt her brød for en sulten skåk som svelter plent ihjel. Gi dem mat der de tar sitt åk . . . og hvem skal gi etter nå, godtfolk, i bytte for slikt et mel?

Guds hvile, godtfolk, Han være deres munterhet et skjold! Hva kongedømme falt så raskt til aske, blod og mold? Mellom sommer og snefall, frosten kommet knapt - våpen og verge, råd og håp, navn og rike tapt!

Slipp ned, slipp ned ved hode og fot - spa jord, og jevn ut alt! Slik begraves nasjoners mot . . . og hvem skal imorgen ha falt, godtfolk, med deres hjelp ha falt?

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Anna Akhmatova (tr. by Lau Beinahr)

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

"La Risposta del Buonarroto" (Buonarroti's response) Translation by William Wells Newell (1900) - signed as "I epigram" in this edition "The Night", Sagrestia Nuova (New Sacristy), Medici Chapels, Basilica di San Lorenzo in Florence, Italy. Photo by Paolo Monti, 1975.

This epigram was written by Michelangelo Buonarroti in response to a quartine by Carlo Strozzi (or, according to Vasari, Giovanni Strozzi) in praise of the artist's statue of the Night, situated on the left of the tomb of Giuliano di Lorenzo de' Medici, Duke of Nemours.

The words are "pronunced" by the statue herself, explaining that she's calmer than the other statues (who are decipted as restless) in the chapel beacuse she's sleeping and don't minding the troubles from the real world, imploring the visitors to keep their voice low and let her sleep.

#scultpure#michelangelo#michelangelo buonarroti#medici#medici family#florence#renaissance#renaissance art#italian art#16th century#italian renaissance#the night#epigram#poetry#italian poetry#renaissance literature#early modern history#short poetry#poetry translation

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

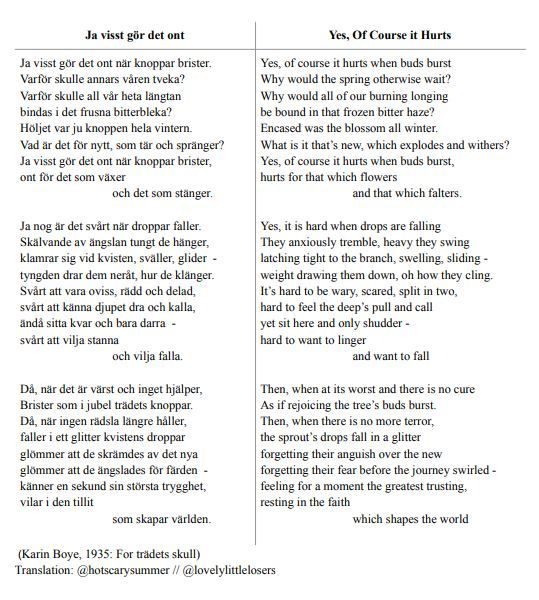

Ja visst gör det ont // Yes, of course it hurts (poetic translation)

Ja visst gör det ont - Karin Boye (link to Karin Boye herself reading, c. 1935)

#i was writing this translation for a language symposium at my college and thought i'd post it here!#also saw a fic on ao3 in the yr tag using this as the title recently which was cool#karin boye#poetry#swedish#svenska#poetry translation#translation#my translation

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

And in my chamber at home, when there I was, alone, by myself, I would proceed straight to my mirror, my glass, To look at the way that my face seemed If it were any other than it should be Eagerly would I, if it had not been right Amended it with all my ability and might.

My amateur translation of a stanza from Hoccleve's 'Complaint', trying to preserve the original rhyme scheme. Informed by this prose translation from Hoccleve Society.

I've flipped the photo so this is the inverse of my previous post - a reflection or mirror perhaps ;) I chose the motif of scrunched bedsheets because it makes me think privacy/private selves. Practicing who you are around everyone else alone in your bedroom.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Stellar epiphanies (English Translation)

When you became a star, I found refuge in the beautiful night.

Like the moon pulling the strings of the sea, your eyes guided my heart to love.

My dear, you left me an intense mark on my soul— as if you had carved a vast tattoo.

And if another girl wanted to understand me, she, unfortunately, would have to know you too.

✦ @dervishlatino | NNF نشوان نازاريو فيريرا ✦

#poetry translation#typewriter poetry#poetry#poems#poetic#original poem#poems and poetry#words words words#prose#original poets on tumblr#original post#original poetry#love poem#poems on tumblr#poems and quotes#short poem#love poems#my poem#poem#spilled writing#poesia poema#spilled feelings#spilled heart#spilled prose#spilled poetry#spilled words#spilled thoughts#spilled ink#spilled emotions#translation

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Odyssey - Book I, 1-10

This convoluted man you’ll tell me about, my Muse,

Did wander far and wide for years, having long since

Laid holy Troy’s most sacred citadel to waste:

He got to know the towns and mind of countless folks,

And suffered many an heartache sailing ‘cross the sea,

In strife for his own life and for his crew’s return.

And yet he did not save them, though he surely tried,

Their foolish minds did seal their final doom instead:

Those idiots ate the cattle of Hyperion Sun,

And he wiped out their hopes of ever coming home.

Do tell us - please - some of that tale, ye child of Zeus!

#poetsofinstagram#poetrycommunity#poets of tumblr#poetry translation#homer#odysseus#the odyssey#hexameter

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

In Bengali they say:

Aamaay bhaashaaili re

Aamaay doobaaili re

Okool dauriaar boojhi kool naai re

Chaahe aandhi aaye re

Chaahe megha chhaaye re

Hamen tu us paar leke jaana maajhi re

Kool naai kinaar naai

Naai ko dauriaar paari

Shaabdhaane chaalaaiyo maajhi

Aamaar bhaanga tori re

Translation:

You have set me adrift

You are causing me to drown

The river seems endless as if there were no shore

Even if a storm comes, or clouds cover the sky, please carry us to the other shore dear boatsman

No border, no shore

The river has no limits

Steer it most cautiously, boatman

This boat of mine with a broken rim

https://youtu.be/FnDmg-cBVsA?si=VRC47PAAE-b4o1BV

#urdu literature#bangladeshi#bengali#urdu stuff#urdu poetry#literature#literary quotes#aesthetic desi#hindi shayari#translation#poetry translation#desi tumblr#being desi#aesthetic#desi aesthetic

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Revising a poem translation I did last year and... god, I HATE translating poetry 😭

I mean, it's fun but

Translating from Tagalog* whose sentence structure (V-S-O) is different from English (S-V-O) is HARD. It makes the original enjambment difficult to keep. I am so tempted to make the lines end-stopped, but who am I to decide how the lines should be cut?

Moreover, the enjambed lines, I just realized, add a sense of perturbation to the persona, whose words in the poem sound completely calm and rational. And I love that because it keeps the delicate balance of intimacy and distance in this poem intact. Removing the enjambment will be reducing the persona to a cold, calculating person.

There's also the matter of what verb tense and aspect to use!

Each Tagalog verb has three basic finite forms which are often referred to as past tense, present tense, and future tense. But this labeling is misleading. The “present tense” form could be used as a past progressive (“She was singing the Ave Maria when I arrived”) as well as a present progressive (“She is singing the Ave Maria”) or present habitual (“She sings the Ave Maria beautifully”). Similarly, the Tagalog “past tense” form can be used like the English simple past (“she sang”) present perfect (“she has sung”), or past perfect (“she had sung”).

– Analyzing Grammar: An Introduction by Paul Kroeger

And oh, don't even get me started on active vs passive voice...

----

*Not using the term “Filipino” because this poem really is only written in Tagalog. There's a difference between the two, and not just politically

#translation#literary translation#poetry translation#poetry#english#tagalog#linguistics#miyamiwu.tl#miyamiwu.src

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

I return to Housman with poem 27 of "A Shropshire Lad", a short meditation about life going on. Which is perhaps less comforting if you're the one it's going on without; such is life, as one might say. As in "Queen of Air and Darkness", Housman's very short text makes me imagine a vast swathe of backstory: Was there a love triangle here before it conveniently collapsed with one point's death? Just how grief-struck was the woman, anyway? The dead man's question implies that she wept nightly at some point, but presumably he did not personally observe this.

I had some difficulty finding reasonably thematic images in a consistent style, which is why "used to plough" and "never ask me whose" are AI-generated. The state of the art seems to have advanced immensely since the last time I used image generation, for "Battle Hymn". Both of these are zero-shot, no infill or repeated tweaking of the prompt, except that "England 1900" gave me an upper-class interior on the first attempt which didn't quite have the vibe I was looking for; specifying "a forest in rural England" fixed the background.

No particular comments on the text this time, except to note that I have faithfully reproduced the infelicity of "used to drive / and hear the harness"; perhaps this is intended as a dialect form? It's an odd transition in received-grammar English.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Best Haiku by Bashō

Original:

Furu ike ya

kawazu tobikomu

mizu no oto

Translation by Lafcadio Hearn:

Old pond — frogs jumped in — sound of water.

Check out this site for some different translations 🐸 (art below by Matsumoto Hoji)

#godzilla reads#haiku#poetry#poetry translation#Japanese haiku#japanese poetry#frog haiku#matsuo basho#book blog#booklr#bookworm#reading

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Guest Anna Akhmatova (tr. by Lau Beinahr)

6 notes

·

View notes