#Plymouth Arts Cinema

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Art of Action: Kicking It! Women’s influence on action films

Plymouth Arts Cinema presents Art of Action: Kicking It! – a film season that celebrates the women who have advanced action cinema both on and off-screen. Continue reading Art of Action: Kicking It! Women’s influence on action films

0 notes

Text

'...Adam is a screenwriter living in London. He strikes up an uneasy acquaintance with his mysterious neighbour Harry, which edges towards something more intimate. At the same time, on visiting his old family home, he discovers something quite strange and beautiful, which keeps him returning time and again. But as the days continue, Adam begins to question the turn his life has taken and whether it is to his detriment. Andrew Scott’s central performance once again shows why he is regarded as one of our finest actors. Paul Mescal is sublime as Harry, while Jamie Bell and Claire Foy’s performances elicit some of the film’s most striking emotional notes...'

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Production history around: Broodiest Flunkey

Finally, I am getting to what I consider the ‘first’ film in my journey as an experimental filmmaker: ‘Broodiest Flunkey’.

This film is a bit rough — it was made as a university project, with a deadline and 3 minute time limit. It was also the first time I had played with many visual effects, and the first time I had shown my work to a live audience.

A lot of what I will be saying in this article will be recycled from my university essay, as my memory on a lot of the details has started to fade.

I created a timeline for this production, so I will try my best to be chronological in the retelling of the film’s creation. Some of the elements may seem tangential, though that is a lot of my practice in general.

I really like the above, because it shows that learning and developing a project (or even personal development), takes a mix of both consumption (books, media) and action (events, trial runs). It also shows how unexpectedly events morph into one another.

In addition to this timeline, I had also created a dated excel timeline of when each event happened (yes, I am thorough). While it shows how ‘Change Spaces’ and ‘Gacha’nce’ fit into the timeline, those won’t be covered here. Noteworthy is how many events overlap with one another, as opposed to being linear.

iDAT XXX

On the 18th of November 2024, I attended an event by Mike Philips, celebrating 30 years since the creation of their institution ‘iDAT’. As part of this event, they ran a ‘telematic performance’ — pretty much information is passed from one system to another, leading to a series of interesting corruptions. This, is then dressed up in a fun avant-garde coat of paint.

It would take a lot later for me to realise that this is a great use of chance as a form of creation. Collaboration, corruptions, improv, a digital exquisite corpse, etc.

MA Experience Design — Design Lab 2

In Design Lab 1, I made a short animation going over the concepts of DADA. Therefore, making video work was heavily on my mind.

The Design Lab 2 brief made me think about what I could do to help the local community. When looking at ‘don’t assume you know your audience’, ‘experiment with materials’, ’leave something beautiful behind’, and ‘make a difference’, it led me down the path of considering making a documentary where I interview people with autism to allow them to be heard and understood.

Autism Documentary

So, I started to plan a documentary about autism, taking the brief into mind. There were lots of worries about it, and I could lie and say they were mostly about GDPR, but it was more so social anxiety of needing to work with so many people!

The in-class activity about making iterative comics was really interesting to me. I wanted to take this idea but apply it to a documentary format. I wanted something similar to the longitudinal study method that ‘Seven Up!’ (1964) engaged in, but also have myself and my beliefs examined as well. This would potentially happen by having a new director for the second film, where they critically look at the first film, and this process is continued indefinitely.

[Accidentally making an exquisite corpse before knowing what that really was!]

Allister Gall Email

The module brief included: ‘collaboration with multidisciplinary partners’. As I was working with film as a medium, I decided to reach out to Allister Gall, the BA Filmmaking programme leader at the University of Plymouth on the 23rd of January 2024. I asked if he was able to send me down the right path, or potentially let me attend a filmmaking lesson.

He let me know about Imperfect Cinema, and that an event was coming up called Cinaesthesia 1. I was very lucky with the timing, as the event was only four days after I sent my email.

[It is funny, I consider this single email an extremely important pivot in my life. If I had not written this email, I likely would not be doing my current PhD, and would not be making experimental art videos. I wouldn’t have heard of Cinaesthesia, and Allister wouldn’t have become one of my PhD supervisors… This email took a minute or two to write, all it takes sometimes.]

The Reason I Jump

During my initial look into autism for the documentary, I read ‘The Reason I Jump’ (2007). The book was written by a 13-year-old mute autistic child living in Japan, and each chapter is them explaining why they do certain actions.

When reading, I realised that there were many areas in which I related to this child, especially thinking back to when I was the same age. While I did not relate to everything, I did more than I normally would with someone. With each example, I started to feel less embarrassed about some moments from my childhood. Moments that I used to fixate on, thinking ‘why did I do that?’ suddenly had an answer that didn’t make me feel as alone or weird.

This feeling of seeing yourself in a book, and this resulting in you being less critical of yourself, I decided to be the message I wanted from my film.

Cinaesthesia 1

This event was run by Patrycja Loranc in collaboration with Imperfect Cinema, and took place at Café Momus on Stonehouse. Patrycja is a PhD student focussing on psychepoetic filmmaking, and the event shared some of this energy.

(Jess Scott, Dutch Loveridge, and Patrycja Loranc at Cinaesthesia 1’s Q&A)

Imperfect Cinema is a Plymouth-based film project created by Allister Gall and Dan Paolantonio, which has the goal of encouraging local artists to create films, as well as to help facilitate events these artists can participate in.

[Side tangent — At this point (8 months since hearing about them), I have heard the two of them go over their intro so many times. It makes me think about what it means to be an academic at university — the need to tear up old ground constantly to explain who you are and what you do. It sounds kind of hellish. I’d struggle to not just make an intro video lol]

As a note for this event, and the ones I talk about later, the networking elements of these screenings are incredible. You get to ask questions directly, sample a lot of local talent, and see the effort of people coming forward. It takes bravery to put yourself out there, and most people there seem to appreciate that.

I was worried that the event would be too ‘heavy’, but it was very casual.

An element of the screening that really resonated with me was the diverse ‘quality’ and styles of work present. There were films presented that I thought ‘I could do that’, and that made me feel like less of an outsider at the event.

At this event, I learnt that a Cinaesthesia 2 and 3 were going to happen in the future, and that they had an open reel for submissions. I pivoted from ‘documentary about autism’ to ‘experimental art film that looked into my own personal experiences reading into autism’.

Getting into Cinaesthesia 2

In order to get a film accepted into Cinaesthesia there were guidelines that needed to be adhered to.

The brief was: “How can the sensory perception/subjective experience be communicated and challenged by filmmaking? How does film allow us to connect to others and the world by exchanging subjective realities?”

It also included that the film must be 3 minutes or less, and submitted by 9pm 21/03/2024.

Experimental Film Production Start

I started my pivot by looking into what made someone’s perception ’unique’, thought about there being so many variables with each person, that everyone’s perception was unique.

In addition to this, I started to consider that my own perception was likely the perception I could best put across to an audience.

I wanted to, somehow, make the audience experience a sense of uneasiness by seeing the world through someone who processes stimuli differently.

Rosemary’s Baby

On the 26th of January 2024, my wife and I watched Rosemary’s Baby (1968) for the first time. It is a great film. In it there is a scene where the main character is trying to work out an anagram by moving around scrabble pieces. I had no plans with this at all. It was just a theme dancing around in my head.

Experience Design’s Telematic Performance

For one of the Design Lab 2 session, Mike Philips wanted us to do a ‘telematic performance’. Since I had seen one prior via his iDAT XXX event, I feel that I had a step ahead of others in the class. This was due to me already knowing what it was meant to look like, and understanding that anything could be used as a step (as long as it caused transformation down the line).

As such, I pushed forward with using Scrabble pieces early on in the sequence, and planned out what the rest of the performance would be.

I would take scrabble pieces out of a bag randomly. Person 2 would make words out of these random letters. Person 3 would then do charades of Person 2’s word. Person 4, who was wearing headphones, had to guess what Person 3 was miming, Person 5, then drew this answer on a post-it note, and added it to a scene on the board.

This whole process was fun, and made me really like the idea of using Scrabble pieces to tell a story.

Scrabble Pieces

Mixing the themes of anagrams and chance, I decided to have one phrase dictate different elements of my film’s story.

I wanted the overall message of the film to be in-line with my takeaway from ‘The Reason I Jump’, so I chose the phrase ‘Be Kind to Yourself’.

Using an online anagram maker, I went through the list of 10,000 combinations, and picked phrases that I thought I could use to string together a narrative that told a story I was happy with.

I wanted to use stop-motion as the technique for these scenes, as it added an eerie feeling that the pieces had a mind of their own, especially since they were what decided the course of the story. Originally, I wanted to film the pieces, and cut out appropriate frames. This did not work due to the camera changing focus, as such I landed on taking still photos after each movement instead.

As stop-motion is a time-intensive process, there were moments where I lost track of what pieces should go where. A colour coded guide was made to make the movement and locations easier to follow.

Pre-Storyboard

Before storyboarding, I thought about elements I wanted to film and why.

I felt that if I went into storyboarding, some fun techniques may have been squeezed out of the production for the sake of narrative.

So instead, I thought about these elements first and how I could use them in the narrative.

Storyboard

Storyboarding your film is useful, however, I did not want to limit myself by structure. For example, knowing how much time was left, or being fixated on scene order. The scenes were drawn in ‘chunks’ and then moved around in order to fit the narrative.

After doing my rough outline of the story, I wanted to make sure I could include the entire narrative in the 3-minute window required by the submission guidelines. As such, I experimented with scene intervals.

‘Yolk Unfit Bedsore’, I thought it was perfect as an opening introduction for a character. ‘Bedsore’ and ‘Yolk’ can both be seen as elements attached to starting the day. Additionally, ‘Unfit’ matched the negative self-image I wanted the main character to have, so the ‘Be Kind to Yourself’ later in the film made sense. Embarrassment seems to be a common issue for some autistic people, so I felt building this into the character was important.

Using this way of thinking, I was able to pace out the Scrabble pieces in a way that completed a cohesive narrative.

With the phrase ‘Befriend — Too Sulky’, I thought I could illustrate that autistic people often want to make social-emotional connections with people, but are unsure how to do so, and the pain this can cause.

I decided on having three second intervals for the storyboard, as I felt this fit best. Any shorter would have been too jarring. Originally, I inserted the Hero’s Journey as a vague guideline for pacing. While this was useful as a rough guide, I did not adhere to it much, as I felt it got in the way of what I believed was a better narrative; perhaps because it made the pacing feel like it was made on a production line.

Once I had my storyboard fully created additional details such as sound effects present, whether it needed chromakeying, and what editing decisions I thought would be needed were added.

In retrospect, I feel that I over-relied on the storyboard. I feel the piece could have been transformed into something more artful by applying wardrobe, doing more area scouting, reframing, and creating some concept art.

Prop Creation

After drawing up the storyboard, I realised that I did not know how I was going to have the other characters in the film be acted. This caused stress as the deadline loomed closer, and I wondered how I would fill these roles.

In order to solve this issue, I decided to use cardboard painted with acrylic for the additional characters instead. I felt that having the main character be the only real-life human added a sense of surrealism, as well as the idea that the plot is ‘from their point of view’. In addition to this, people with autism often feel ‘disconnected’ from other people, and I feel this separate ‘plane of existence’ with 2D vs 3D illustrates this idea in an interesting way.

The character at 0:47 having a sudden expression change was important as it shows the main character trying to grabble with a complex emotional encounter, which is considered a struggle for some with autism.

With the characters being made out of cardboard, I had the worry that this would come across as too jarring to the viewer. To solve this, and to make the overall film feel like it had a cohesive style, I decided to make more elements out of cardboard.

Items like the phone, egg, toothbrush, etc. were made out of cardboard as well. I believed it would be funny to have these mundane elements, that would be way easier to have the real-world items, be recreated. The prop creation was the most time intensive part of the project, but I think it was worth it. When the screening of the film happened, the props were the most complimented aspect by the audience in attendance.

In the film, early on, I have a moment where I flip an egg, purposely showing the cardboard underside. This is to reveal to the audience that I am not hiding the fact that these elements are cardboard — this works as a way to let them in on the silliness.

To help with cohesion for scenes where no props were present, the backgrounds are also acrylic on cardboard. These were added by using chromakeying. The painted areas are purposely small and zoomed in, to make the fact that they have texture and are cardboard more apparent.

Book

The book in the film had two versions, one which was a ‘prop book’, and one that I bound.

The prop book was a cover and back, with painted cardboard sides to resemble paper, and three DVD cases in the middle.

Because the bound book contains pages that were filmed, including the book, this needed to be created after the prop book scenes took place.

In order to match the Scrabble description of the book being ‘finely rusted’, I followed a tutorial by Treasure Books (2023) using cinnamon to create faux rust. This, on top of the book also being obviously cardboard I believed was a fine compromise.

My Wedding

In the middle of this production, with a deadline looming over, was my wedding. I am so happy that the whole process was easy.

[Only while writing this piece had it dawned on me that my filmmaking and married life have been so overlapped.]

Filming

The film was shot on a Sony Alpha 6400 with a SELP1650 lens, and a fisheye shot was done with a 7 Artisans 7.5mm 1:2:8 ED lens. A Sony GP-VPT2BT grip was also used in many scenes to allow for filming while a light was being held.

Two ‘EMART 60 LED’ lights were used to light up the scenes, and a ‘Neewer 5’x7' Greenscreen’ was used for chromakeying.

Some elements of the storyboard needed to be adapted to make the filming process easier. Firstly, a printed breakdown was made of each scene with what happens in terms of editing, effects, sounds, and props present, etc.

For the scenes that were included within the book, a chronological edit of the storyboard was made.

There were moments when parts of the production didn’t go to plan, and as such improvisation had to happen. For example, When the book was put into shrubbery at 2:20 in the film, originally it was meant to be pulled out by string. However, during filming, the string kept snapping. As such, we made the book float behind the main character instead.

Editing

The editing process was turbulent for a few reasons. Primarily, due to Vegas Pro 18 crashing every few hours, however this is unfortunately an aspect to be expected.

The editing process was useful, because it really allowed me to consider which moments were important to the narrative, which I don’t think I would have realised if I handed the work off to another person to edit.

The original cut of ‘Broodiest Flunkey’ was 4 minutes long, and as such 25% of the footage needed to be trimmed down in order to be within the 3-minute window required for submission.

The music at the start of the film is ‘Toc de matinades’ by Rafael Caro (2016), and is Catalonian folk music which is played in the streets early in the morning to wake up people so they can get ready for celebrations. Since this was the day that the main character learnt to be kind to themselves, and that it starts with them waking up, I thought it was appropriate. Also, the tone shift from positive music to more eerie and atmospheric music I felt made the transition feel more contrasted, and as such have more impact.

The sounds of the Scrabble pieces moving was made by moving a container filled with Lego.

With this, the film was finished and rendered. I decided to keep the film internal until Cinaesthesia 2, as associating its premier with the event felt special. This process of keeping videos unavailable until an in-person premier is a practice I feel makes attending an event feel more worthwhile.

Behind the Scenes

Due to the large amount of footage available, I decided to make a behind the scenes video to both commemorate the experience, and as an excuse to remove all the footage from my PC without feeling too bad about it being harder to access.

Cinaesthesia 2

Cinaesthesia 2 took place on 23rd March 2024, and was a lot of fun. Members of my cohort attended which was greatly appreciated.

I would say that the reaction to the screening was extremely positive.

I worried that the subject of autism may have been a bit out of place, or that I would have felt ‘othered’, but then again punk environments have always embraced those that were seen as on the ‘rim’ of society.

Q&A

I was part of a Q&A after the screening, and this was my first time I would talk about my work in a public forum like this. There was something really special about this I felt, and it made me want to talk about my work with others more in the future.

Meeting cool people

It overall was a great night, which made me excited for the future. I met so many cool and talented people, who have stuck around in the peripheries of my life for several months now.

Also, Abi Ali, one of the filmmakers present, stopped me after the show to say my work was her favourite, and guess what, her work was my favourite too.

SO YEAH! This is where it all began. Or rather, where I arbitrarily decided it began. Has it even started yet? Find out next time, on Dragon Ball Z!!

#filmmaking#experimental film#independent filmmaking#experimental art#avant-garde#artistic process#creative process#cinematography#chance in art#serendipity#randomness#creative exploration#autism and art#identity and creativity#art and transformation#artist journey#behind the scenes#personal growth#art reflections#creative techniques#video editing#film production#experimental methods#film community#artist support#creative collaboration#aesthetic#visual storytelling#abstract art

0 notes

Text

Filmes Considerados Quase Perfeitos

Filmes considerados quase perfeitos, você concorda com a lista que selecionamos aqui? Os desafios envolvidos na escrita, fotografia, edição e lançamento de um longa-metragem são extremamente complexos e rigorosos. Há vários fatores a serem considerados e mesmo com todo o esforço, não há garantias de que o filme será bem recebido pelo público ou sairá da maneira planejada pelos criadores. É por isso que filmes podem variar de terríveis a incríveis obras de arte. Os filmes mais memoráveis são aqueles que contaram com uma equipe excepcional, emocionaram o público e deixaram uma mensagem duradoura. Você concorda? Confira abaixo, a lista com os filmes mais aclamados dos últimos tempos, considerados quase perfeitos e deixe sua opinião.

O Grande Hotel Budapeste é Uma Obra-Prima De Wes Anderson

Nos anos 30, um gerente de hotel europeu se torna amigo de um jovem colega de trabalho. Juntos, eles roubam um quadro famoso e de valor inestimável e lutam por uma fortuna de família.

O filme é uma obra de arte cinematográfica que apresenta uma visão única da história europeia do século passado. A trama é habilmente tecida em torno da amizade improvável entre dois colegas de trabalho, que se envolvem em uma série de aventuras. O roubo do quadro famoso é apenas o começo de uma jornada cheia de reviravoltas e surpresas, que culmina em uma luta épica pela fortuna da família. Uma mistura perfeita de drama, comédia e suspense. Se você está procurando por um filme emocionante, inteligente e bem feito, não deixe de conferir esta obra-prima do cinema. Além da história envolvente, o filme também é visualmente deslumbrante. A recriação do cenário histórico da Europa dos anos 30 é impressionante, com figurinos e cenários impecáveis que transportam o espectador para a época retratada. A fotografia é excepcional, com planos e enquadramentos que realçam a beleza e a dramaticidade da trama. E a trilha sonora, composta especialmente para o filme, complementa perfeitamente as cenas e evoca as emoções necessárias em cada momento. No geral, este é um filme que agrada não só aos amantes de cinema, mas a todos que buscam uma experiência emocionante e divertida.

Manchester à Beira-Mar: Um Filme que Provoca Emoções Fortes

Filmes Considerados Quase Perfeitos Manchester à Beira-Mar não é um filme que se assiste para relaxar. Este drama, escrito e dirigido por Kenneth Lonergan, conta a história de Lee Chandler (Casey Affleck), que retorna à sua cidade natal após a morte de seu irmão.

Quando descobre que agora é o guardião do sobrinho adolescente, ele é forçado a confrontar seu passado e eventos traumáticos que nunca se curaram. Affleck e Lonergan ganharam o Oscar de Melhor Ator e Melhor Roteiro Original, respectivamente. Embora incrível, o filme evoca emoções que ninguém quer experimentar na vida real.

A Bruxa trouxe vida nova ao gênero de terror.

O filme "A Bruxa", dirigido por Robert Eggers, conta a história de uma família que, após ser banida da comunidade puritana de Plymouth, decide viver em uma fazenda na beira de uma grande floresta.

Quando seu filho desaparece misteriosamente, a família é manipulada por uma força sobrenatural na floresta, levando-os a se separarem. Para tornar o filme mais realista e aterrorizante, Eggers dedicou quatro anos de pesquisa para sua estreia como diretor. O elenco, composto por atores jovens e experientes, entregou performances excelentes, fundamentais para a iminente sensação de desgraça que o filme evoca.

O Labirinto do Fauno

Filmes Considerados Quase Perfeitos Pegue a pipoca e prepare-se para uma aventura emocionante! O aclamado diretor Guillermo del Toro criou uma fantasia sombria com "O Labirinto do Fauno", que se passa cinco anos após a Guerra Civil Espanhola.

A história segue a jovem protagonista Ofelia, enquanto ela interage com criaturas mágicas que a conduzem a seu destino final em um mundo mítico. O filme é elogiado por sua narrativa, efeitos visuais, fotografia e atuação, embora contenha momentos violentos e emocionalmente desgastantes. Ainda assim, é considerado um dos melhores trabalhos de Del Toro e é um tesouro para os amantes do cinema. Se você é fã de filmes de fantasia, "O Labirinto do Fauno" é uma escolha imperdível! Com uma trama envolvente que mistura realidade e mitologia, o filme é capaz de prender a atenção do espectador do início ao fim. Além disso, as criaturas mágicas apresentadas são muito bem construídas, o que contribui para a imersão na história. Não é à toa que o filme foi indicado a seis categorias do Oscar, incluindo Melhor Diretor e Melhor Roteiro Original. Se você ainda não assistiu, não perca mais tempo e embarque nessa emocionante jornada junto com Ofelia!

O Grande Lebowski - Dos irmãos Coen

Preparem-se para rir muito com o caos hilário do filme! O filme de comédia "O Grande Lebowski", escrito, dirigido e produzido pelos irmãos Coen, narra a incrível história de "The Dude" (interpretado por Jeff Bridges), que se vê preso em uma rede de mal-entendidos e planos fracassados.

A trama do filme é apresentada de forma desordenada, deixando o público tão confuso quanto o personagem principal enquanto ele tenta juntar as peças. Embora o enredo possa ser divertido, o que realmente torna o filme único são seus personagens excêntricos. O diálogo incrivelmente espirituoso e hilário destes personagens também fornece ao público um suprimento infinito de citações ridículas que somente os fãs do filme conseguem entender. Além disso, o filme conta com uma trilha sonora incrível, que mistura diferentes estilos musicais, desde o rock clássico até o jazz. A escolha musical dos irmãos Coen é sempre impecável, e em "O Grande Lebowski" não é diferente. A música ajuda a criar a atmosfera única do filme e nos transporta diretamente para o mundo dos personagens. Não perca a chance de ver esta obra-prima da comédia dos anos 90, um clássico cult que continua conquistando fãs ao redor do mundo, mesmo depois de mais de 20 anos do lançamento.

Cidade dos Sonhos: O Filme do Século

Filmes Considerados Quase Perfeitos Desde os primórdios do cinema, o surrealismo tem sido uma técnica explorada pelos cineastas, sendo inspirada em diversas formas de arte surrealista.

No filme "Cidade dos Sonhos", David Lynch mostra como essa técnica pode ser transmitida de maneira perfeita em um longa-metragem. Na verdade, o filme é equiparável a um sonho inquietante que confunde os limites entre a realidade e a imaginação. De acordo com o crítico de cinema Robert Eggers, o filme "trabalha diretamente nas emoções, como a música". Com suas diversas cenas memoráveis, o público fica grudado na tela, o que levou a BBC a nomeá-lo como o melhor filme do século 21 até o momento.

2001: Uma Odisseia no Espaço uma obra-prima da ficção científica

O filme, dirigido por Stanley Kubrick, foi inspirado no conto "The Sentinel" de Arthur C. Clarke. A história é sobre uma viagem espacial a Júpiter, acompanhada pelo computador artificialmente inteligente HAL, depois que um monólito preto foi descoberto afetando a evolução humana.

Embora o enredo seja fascinante, o que torna o filme excepcional é a sua precisão científica e os temas pesados de evolução, existencialismo, inteligência artificial e viagens espaciais. Mas, não se engane: a trama é apenas a ponta do iceberg que nos leva a refletir sobre muitas questões da atualidade. O filme é considerado pioneiro em efeitos especiais, com som e diálogo usados de forma moderada para criar uma atmosfera espacial. A precisão científica é impressionante, e o filme é frequentemente incluído em listas dos dez melhores filmes já feitos. É uma obra-prima da ficção científica e tem sido altamente influente na cultura popular.

Explorando o Filme "Ela"

Filmes Considerados Quase Perfeitos Her é um romance de ficção científica que foi escrito, dirigido e produzido por Spike Jonze. O filme conta a história de Theodore Twombly (interpretado por Joaquin Phoenix), um escritor solitário que está passando por um divórcio.

Na tentativa de combater a sua solidão, ele adquire um sistema operacional (interpretado por Scarlet Johansson) e acaba se apaixonando por ele. Com uma bela utilização de cores pastéis, cenas urbanas empoeiradas e uma trilha sonora impressionante, o público é transportado para o mundo de Twombly. A atuação incrível de Joaquin permite que o público se identifique com o personagem, experimentando suas emoções em primeira mão. A maneira como a sociedade é retratada no filme é tão realista que nos faz questionar se esse mundo está tão longe do nosso.

Análise de "Pulp Fiction" de Quentin Tarantino

Filmes Considerados Quase Perfeitos O aclamado Quentin Tarantino escreveu e dirigiu este filme, que conta com um elenco estelar liderado por Bruce Willis, Samuel L. Jackson, Uma Thurman e John Travolta, entre outros.

O filme apresenta uma série de histórias de crimes interligadas que ocorrem em Los Angeles. Embora a atuação do elenco seja impressionante, o que realmente diferencia Pulp Fiction de outros filmes é sua narrativa não linear. O enredo é construído de forma surpreendente, com cenas aparentemente desconexas que se juntam no final. Para tornar a experiência ainda mais memorável, Tarantino adiciona sua própria trilha sonora característica, que é muito familiar para os fãs.

O Enigma de Outro Mundo: Um Filme Clássico de Terror

O Enigma de Outro Mundo é um filme dirigido por John Carpenter e escrito por Bill Landcaster. A história segue um grupo de pesquisadores em uma área isolada da Antártica.

Enquanto eles exploram o local, descobrem "A Coisa", uma forma de vida desconhecida que tem a capacidade de se transformar em outros organismos. Quando "A Coisa" assume a forma dos pesquisadores, a paranoia toma conta de todos, tornando-os incapazes de confiar uns nos outros. Embora tenha recebido críticas negativas pelo cinismo e pelos efeitos especiais gráficos, com o tempo, as pessoas começaram a apreciar a complexidade e o valor do filme. Hoje, O Enigma de Outro Mundo é reconhecido como um dos mais importantes filmes de terror já produzidos, consolidando-se na história do cinema.

O Sucesso da Trilogia "O Senhor dos Anéis" O Retorno do Rei

Não é segredo pra ninguém que a adaptação cinematográfica da trilogia "O Senhor dos Anéis" por Peter Jackson foi um dos maiores empreendimentos na história do cinema.

No entanto, o resultado final justificou todo o investimento. O filme é grandioso em escala, com batalhas épicas, belíssima cinematografia e uma trilha sonora singular. "O Senhor dos Anéis" ocupa um lugar na lista dos filmes de maior bilheteria de todos os tempos. Ele conquistou 11 prêmios Oscar, incluindo Melhor Filme. Além de ser considerado o filme de fantasia mais influente de todos os tempos.

O Assassinato De Jesse James Pelo Covarde Robert Ford (2007) - Uma Abordagem Diferente do Faroeste

Apesar de subestimado na época, este filme é considerado um dos melhores do gênero faroeste. Diferentemente de outras obras, o enredo se concentra mais nos personagens do que nos tiroteios comuns.

Cada cena é uma verdadeira obra de arte, graças ao diretor de fotografia, Roger Deakins, que criou novas lentes para capturar as imagens perfeitas. A trama segue a história do bandido Jesse James (Brad Pitt) e suas batalhas psicológicas, bem como seu relacionamento com um admirador instável (Casey Affleck). Tamanha beleza não passou despercebida, já que o filme foi indicado ao Oscar de Melhor Fotografia.

Você Nunca Esteve Realmente Aqui: uma obra-prima sombria e singular

O filme "Você Nunca Esteve Realmente Aqui" gira em torno de Joe, um assassino contratado por um senador para resgatar sua filha de uma rede de tráfico sexual. No entanto, ele se vê envolvido em uma conspiração perigosa que ameaça sua vida.

Embora a premissa do filme pareça clichê, o tratamento dado aos personagens e a maneira como a trama subverte as expectativas é notável. Phoenix oferece uma interpretação incrível de seu personagem, mostrando seu sofrimento e ao mesmo tempo sua dedicação como filho e sua crueldade como assassino. São essas nuances e as reviravoltas surpreendentes que elevam o filme a um nível de excelência.

John Wick Muito Além de um Ex-assassino

O filme de ação "John Wick", estrelado por Keanu Reeves, é uma obra-prima que se destaca entre outros filmes do mesmo gênero. Com uma execução incrivelmente rápida, o filme é de tirar o fôlego.

Para se preparar para o papel, Reeves treinou oito horas por dia, cinco dias por semana, durante quatro meses, demonstrando que sua dedicação ao processo criativo é uma das razões para o sucesso. Embora a iluminação, os efeitos especiais e o enredo possam ser emocionantes, "John Wick" é muito mais do que um filme de ação padrão. Na verdade, a história é sobre um homem de luto que perdeu a única coisa que o conectava à sua esposa recentemente falecida. A profundidade emocional que o filme oferece é raramente vista em produções do gênero, tornando-o especialmente impactante.

Sangue Negro: Um Retrato Sombrio da Natureza Humana

O diretor Paul Thomas Anderson retrata a caça ao petróleo e a ganância financeira que ocorreram no final do século XIX no seu filme "Sangue Negro".

Com as estrelas Daniel Day-Lewis e Paul Dano, o filme aborda o impacto negativo do capitalismo na sociedade americana e as ações depravadas que a ganância pode levar as pessoas a cometer. O desempenho surpreendente de Day-Lewis é complementado pelas imagens de Robert Elswit e pelo roteiro de Anderson, criando um filme que é tão sombrio e sujo quanto o petróleo que retrata. Além do tema principal, o filme também aborda questões como a religião e a relação do homem com a natureza. O personagem de Paul Dano, um pregador carismático, representa a hipocrisia religiosa que muitas vezes justifica ações cruéis em nome de Deus. Já Day-Lewis interpreta um magnata do petróleo que, ao mesmo tempo em que é obcecado pelo sucesso financeiro, também sente uma conexão espiritual com a terra e a natureza, o que leva a uma tensão interna interessante em seu personagem. No geral, "Sangue Negro" é um filme denso e complexo, que exige atenção do espectador, mas que recompensa com uma história intrigante e bem contada. Se você gosta de filmes que provocam reflexão e análise crítica da sociedade, com certeza vale a pena conferir essa obra-prima do cinema contemporâneo.

Os Imperdoáveis: Um Filme do Velho Oeste que Desafia as Convenções

Clint Eastwood é um nome conhecido no gênero Velho Oeste, mas nunca foi um pistoleiro comum. Em "Os Imperdoáveis", um filme que ele estrelou e dirigiu, isso fica ainda mais evidente.

O filme retrata a história de um fora da lei aposentado, interpretado por Eastwood, que retorna para um último trabalho. O filme desafia as convenções dos tradicionais filmes de faroeste glorificando a violência. Eastwood oferece ao público uma experiência realista de como é matar e morrer, expondo a verdadeira feiura da violência.

Tubarão Continua Aterrorizando o Público

Se não fosse pela habilidade de Steven Spielberg e sua equipe, "Tubarão" teria sido apenas mais um filme de verão, que cairia na obscuridade na temporada seguinte.

No entanto, o filme se tornou um fenômeno cultural e permanece como um dos clássicos do cinema americano até hoje. Spielberg criou tensão de maneira magistral, acompanhado pela trilha sonora icônica de John William, o que resultou em um filme que superou as expectativas do público. Read the full article

#2001:UmaOdisseianoEspaço#abruxa#amazonprime#BrilhoEternodeumaMentesemLembranças#cidadedossonhos#Ela#filmes#filmesconsideradosquaseperfeitos#hbo#JohnWick#lancamentos#ManchesteràBeira-Mar#melhoresfilmes#netflix#OAssassinatoDeJesseJamesPeloCovardeRobertFord#OEnigmadeOutroMundo#ograndehotelbudapeste#OGrandeLebowski#OLabirintodoFauno#osenhordosanéis#osenhordosaneisoretornodorei#osimperdoaveis#pulpfiction#resumodefilmes#sanguenegro#silencio#tubarao#vocenuncaesteverealmenteaqui

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Artist on stage at Theatre Royal Plymouth

Devon. I’m in Devon. And my heart beats so that I can hardly speak. This evening, at the Plymouth Arts Cinema I had the honours of introducing a screening of the modern silent that made a big noise, The Artist (Michel Hazanavicius, 2011). You remember? The one that won FIVE Oscars? With the dashing Jean Dujardin and the yet more dashing Uggie the Dog? Raise one Gallic eyebrow if you know the…

View On WordPress

1 note

·

View note

Text

If you are in Barcelona, Vienna, Plymouth, London, Frome or Newcastle in the next weeks, come check out Alex MacKenzie’s EXPERIMENTS FOR A SINGLE PROJECTOR, as he tours this live expanded cinema show to a few select stops in Europe (see below for dates and locations) and presents workshops along the way.

Exploring the potential of the 16mm film projection apparatus and amplifying the possibilities of this refined and precise tool, EXPERIMENTS FOR A SINGLE PROJECTOR is a suite of expanded and performed works that use the mechanism to its fullest potential; manipulating, modifying and enhancing various aspects of its functionality. Found footage, painted filmstrips and light are transformed with beam interference, bipacked looping, focus, lens and shutter alterations to create radically transformed and dreamlike spaces—epic, immersive, and abstracted. The results shimmer across the screen, uniting “the cosmic with the microscopic...in an ecstatic splendour of light” (Marilyn Brakhage).

“Alex MacKenzie is the unequivocal master of contemporary Canadian expanded cinema: using rare and outdated technology with the deft touch of a visual alchemist, MacKenzie spins his stunning and mesmerizing anti-narratives using the detritus of cinematic history to create a completely unforgettable, and undeniably powerful, alternate vision.” -Antimatter Media Art

“MacKenzie is a key player in the revival of expanded cinema forms, having performed an array of super 8 and 16mm projection works over the last twenty-five years. His projects stretch the possibilities of the analogue form, manipulating images to beyond our received expectations.” -Chris Kennedy, Early Monthly Film Segments (Toronto)

Experiments for a Single Projector DATES AND LOCATIONS:

28 July Barcelona - Crater-Lab Hangar, door T 8pm 31 July Vienna - filmkoop wien 7pm 02 August Plymouth - CAMP/37 Looe Street 7pm 07 August London - Close-Up Film Centre 8:15pm 09 August Frome - Bennett Centre 7:30pm 11 August Newcastle - Star & Shadow Cinema 7:30pm

#expandedcinema#alexmackenzie#irisfilmcollective#eurotour#live16mmfilm#livecinema#experimentalcinema#experimental film#closeupcinema#bennett centre#starandshadowcinema#filmkoopwien#craterlab#plymouth 37 looe st

0 notes

Text

Roxana Halls.

Bio:

Born in 1974 in Plaistow, London, now still living in london with her wife. Growing up Halls aspired to be an actress. Halls took a foundation course in art at Plymouth college of art and design but found she was very self reliant, describing herself as mainly self taught. Halls has been widely praised for draughtsmanship, wry humour and disturbing narratives.

practice:

Halls has said that she often equates painting with performance and that her models collude with her in creating theatrical scenarios for which the viewer is invited to tease out narratives. Her long standing interest in drama and performance is evident in the baroque sensibility of many of her works. Halls is known for her her images of wayward women who refuse to conform to societies expectations of women. Halls practice has relied on painting from life, memory and photographs, referencing everything from high art and philosophy to the zeitgeist. Halls work often references things such as: the war time paintings of Dame Laura Knight, the songs of Nick Cave, Avantgarde cinema and the fashion for glamourising the past. Halls paintings often examine gender, class, identity and sexuality. Her paintings focus on the materiality of peoples lived environments, seducing the viewer the viewer with exquisite still lives of her emphasis on the fabrics and hair. Her work rebuts the idea that grandiose history paintings are a better barometer of contemporary life. Halls work asks us: how is women behaviour policed by society and how do women internalise those expectations and limitations through self surveillance?

"Appetite":

This series by Halls regards consumption and abstinence. Portraying that women transgress by behaving as they are expected to. this is an insight into culture and counter-culture, being playful, political and sharp. the piece 'Beauty Queen' portrays a beauty queen taking a nibble out of her winners bouquet. this gives the impression off the much rumoured beauty queens starve for perfection, this beauty queen in particular being so hungry that after her big win and finally being able yo eat something she is digesting her bouquet. Halls work throughout this series are of candid aesthetics, dramatic and elaborately composed awkward movements that subvert the demure poses expected of women.

How she has impacted my work:

I was inspired by the political aspect of Halls work and her themes of feminism, confirming and women being policed by society.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

February 1945: Buckea's bakers shop, stands alone on the corner of Boswell Street and Theobalds Road, Holborn, after heavy bombing. WW2 By Reg Speller Plymouth, My home town. It is such a shame as the old buildings that were there were beautiful. During the war the two main shopping centres of Plymouth and nearly every civic building were destroyed. 26 schools, eight cinemas and 41 churches were also destroyed. In total, 3,754 houses were destroyed with a further 18,398 seriously damaged. Plymouth Arts and Heritage Service.

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

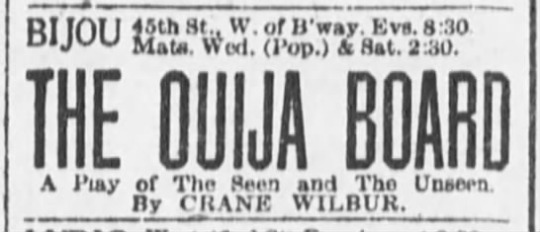

THE UNSEEN HAND / THE OUIJA BOARD

1920

The Ouija Board (previously known as The Invisible Hand) is a play in three acts by Crane Wilbur. It was originally produced by A.H. Woods and staged by W.H. Gilmore starring Alma Belwin and Mr. Wilbur (above).

The supernatural themed play was billed as a “play of the seen and unseen.” This was Wilbur’s first play on Broadway as a playwright. Rehearsals began in late January 1920.

About the Title: A Ouija board, also known as a spirit board or talking board, is a flat board marked with the letters and numbers along with various symbols and graphics. It uses a planchette (small heart-shaped piece of wood or plastic) as a movable indicator to spell out messages during a séance. Participants place their fingers on the planchette, and it is moved about the board to spell out words. "Ouija" is a trademark of Hasbro, but is often used generically to refer to any talking board.

The play takes place in the library in Henry Annixter's house and a room in Gabriel Mogador's house in a large manufacturing town in the upper part of New York State.

A woman who is left too much alone deserts her husband for another man, who in turn deserts her. Her husband condones her fault and she returns to him, but lives only a short time, leaving a little boy, the father of whom betrayed her. Her betrayer finally lands In prison, and after his release disguises himself as a spiritualistic medium and starts swindling the people of a large town by purporting to receive communications from the dead. Among his victims is the man whom he has wronged, and who believes he can communicate with his dead wife through the writing stunt. The mind of the faker becomes so unsettled that he Imagines he sees the woman's spirit and unconsciously reveals his identity In the writing. His patron becomes enraged and plunges a dagger in his back, killing him. When discovered, the dead man's hand is resting on the pad, and the message of the dead helps to solve the second crime, that of the killing of the man who killed the medium. The perpetrator of the latter tragedy is none other than the medium’s son, a dope fiend, who expected to marry the daughter of his benefactor, who inherited her father's fortune.

As The Unseen Hand, the play opened in Atlantic City at the Globe Theatre on February 16, 1920.

It was next seen at the Lyceum in Paterson NJ on March 26th and 27th.

After this engagement, producer Woods changed the play’s title to The Ouija Board, despite it having a very small part in the action of the play.

The Ouija Board opened on Broadway at the Bijou Theatre (209 West 45th Street) on March 29, 1920.

About the Venue: The Bijou Theatre was built in 1917. In 1935, it became New York's first all-cartoon cinema, beginning a rotating cycle during which the house alternated between legit and movie presentation (except when it was dark from 1937 to 1943). In 1959, the adjoining Astor was renovated and acquired a large chunk of the Bijou's space. It reopened as an art cinema in 1962. Intermittent legit productions followed until the theatre was demolished in 1982, making room for the Marriott Hotel.

“One of the devices of the play which surprised but did not altogether please us was an electrical device installed n a phonograph by which anybody who played "Fair Harvard' would be shot in the chest. It served to kill one character in the play and another barely escaped. We would have found it more pleasing and convincing as well, if he had died from ‘Boola Boola’ or ‘Old Nassau.’“ ~ HEYWOOD BRAUN

The play ran 64 performances at the Bijou closing on May 23, 1920. On Monday, May 25th the play decamped to Boston’s Plymouth Theatre where it quietly departed this theatrical world after a brief run.

#The Ouija Board#The Unseen Hand#Crane Wilbur#Broadway Play#Broadway Theatre#Atlantic City#Supernatural#1920#Theatre#Plays

2 notes

·

View notes

Video

vimeo

CYCOLOGIC Trailer from Emilia Stålhammar on Vimeo.

"Traveling the streets of Kampala one does not only face a chaotic and dangerous traffic environment but also struggles to go through endless queues, pollution, motorcyclists and cars attacking you from every angle which is a energy-consuming dilemma.

Politicians seems to have given up but there are a few people who strives to show that there are alternative ways of movements.

The urban planner Amanda Ngabirano's biggest dream is to have a cycling lane in her city. An impossible task, according to most people, but not according to Amanda."

Awards: Grand Prix - African Road Safety Film Festival, Morocco, 2018 Best Short Documentary - Annual Copenhagen Film Festival, Denmark, 2018 Best Short Film - ArchFilmLund, Sweden, 2017 Juried Prize Best Short Film - Dublin Feminist Film Festival, Ireland, 2017 Juried Prize Best Film - New Urbanism Film Festival, USA, 2017 Audience Award - Environmental Film Festival Australia, 2017 Juried Prize Best Short Film - ArchFilmLund Prize, Sweden, 2017 Juried Prize Best Short Film - RUEDA Cycling Film Festival, Spain, 2017 Juried Prize Best Short Film - London Feminist Film Festival, UK, 2017 Juried Prize of the Media Partner Aktuality.sk for Inspiring Message - Ekotop, Slovakia, 2017 Juried Prize Best Short Film - Bike Shorts Film Festival, USA, 2017 Audience Award - Bike Shorts Film Festival, USA, 2017 Juried Prize Best Short Film Africa / Middle East Cinema 2nd quarter - Nüren Film Festival, Singapore, 2017 Juried Prize Best Documentary Goldene Kúrbel, International Cycling Film Festival - Germany, 2016 Audience Award, International Cycling Film Festival - Poland, 2016

Official Selections: Lviv International Short Film Festival Wiz-Art, Ukraine Budapest Architecture Film Festival, Budapest, Hungary Architecture Rotterdam Film Festival, Rotterdam, The Netherlands World Wide Women's Film Festival, Arizona, USA ArchFilm - Lund, Sweden Interfilm Berlin Film Festival - Berlin, Germany We The People's Film Festival, London, UK Green Screen Environmental Film Festival - Trinidad & Tobago Greenmotions Film Festival, Freiburg, Germany Prvi Kadar International Film Festival - Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina The People's Film Festival - London, UK Dublin Feminist Film Festival - Dublin, Ireland Environmental Film Festival Australia - Melbourne, Australia Imagine This Women's Film Festival - Brooklyn, USA Iran International Green Film Festival - Tehran, Iran New Urbanism Film Festival, Los Angeles, USA Architecture Film Festival Rotterdam - Rotterdam, The Netherlands Leeds International Film Festival - Leeds, UK RUEDA International Cycling Film Festival - Barcelona, Spain Bicycle Film Festival - Ottawa-Gatineau, Canada International Kuala Lumpur Eco Film Festival 201 - Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia Sose International Film Festival - Yerevan, Armenia Tuzla Film Festival - Tuzla, Bosnia and Herzegovina International Images Film Festival for Women - Harare, Zimbabwe Aaretaler Kurzfilmfestival - Trimstein, Switzerland Bicycle Film Festival - Quito, Ecuador London Feminist Film Festival - London, England Global Impact Film Festival - Washington, USA Bicycle Film Festival - New York, USA Eko International Film Festival - Lagos, Nigeria Viva Film Festival - Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina The Cump Festival - Nairobi, Kenya Les Filministes - Montréal & Québec, Canada Aaretaler Kursfilmtage, Trimstein, Switzerland Edinburgh Festival of Cycling - Edinburgh, Scotland Silver Horse International Film Festival - Borlänge, Sweden Cine Sister, Plymouth - England Feminist Festival - Malmö, Sweden EkoTopFilm - Bratislava, Slovenia Nüren Film Festival, Singapore, Singapore CinemAmbiente - Turin, Italy Bike Short Film Festival - Virginia, USA Trondheim Sykkelfilm Festival - Trondheim, Norway Global Road Safety Film Festival UN - Geneva, Switzerland South African Eco Film Festival - Cape Town, South Africa Big Bike Night - Touring in New Zealand Doc Lounge - Malmö, Sweden Filmed By Bike - Portland Oregon, USA Chicago Feminst Film Festival - Chicago, USA Berlin Feminist Film Week - Berlin, Germany International Cycling Film Festival - Herne, Germany & Krákow, Poland Giddy Up Film Tour - Touring in USA

Articles:

facebook.com/cycologicdocumentary

blogs.worldbank.org/publicsphere/cycologic-power-women-power-bicycles-uganda?page=1

wearemovingstories.com/we-are-moving-stories-films/2017/10/25/new-urbanism-film-festival-cycologic?rq=cycologic

ecf.com/news-and-events/news/cycologic-film-about-changing-world-one-bicycle-time

cyclingfilms.de/en/2016/10/23/eilmeldung-goldene-kurbel-geht-nach-schweden/

newvision.co.ug/new_vision/news/1431631/amanda-ngabirano-ugandan-inspired-swedish-filmmakers

twitter.com/UN/status/790107996261117952

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Visual imagination | Director Mark Cousins in Plymouth with his doc

Mark Cousins, the director of a new documentary re-appraising the life and work of a painter who had a home in the South West for more than 60 years, is visiting Plymouth Arts Cinema for a Q&A and film screening. Continue reading Visual imagination | Director Mark Cousins in Plymouth with his doc

0 notes

Photo

Art Deco Britain by Elain Harwood

The book begins with an overview of the international Art Deco style, and how this influenced building design in Britain. The buildings covered include houses and flats; churches and public buildings; offices; shops, showrooms and cafes; hotels and public houses; cinemas, theatres and concert halls; sports buildings; industrial premises and transport buildings.

The book covers some of the best-loved and some lesser-known buildings around the UK, such as the Midland Hotel in Morecambe, Eltham Palace, Broadcasting House and the Carreras Cigarette Factory in London, Finella in Cambridge, St Christopher’s Church in Liverpool and Tindale Lido in Plymouth.

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

Production history around: After Images

Time for another look into one of my films, ‘After Images’.

youtube

This was filmed in the nightclub ‘Images’ which is in Plymouth city centre. I only started going there this year (2024), and it’s a cool place to meet alternative and inclusive people. It is funny that a lot of alternative people can look quite scary on the outside, but are some of the sweetest people you can ever meet. That is often the case I think though.

The club represents, to me, many of the people I have met so far in my art journey these past 6 months. I won’t name names for privacy reasons, but there are a few that go there who I have met through Imperfect Cinema, some from my current university course, some from Anime society, etc. It feels like a great encapsulation of my life post-joining my MA Experience Design degree, which is a far cry from my life prior.

How this film came to be: for a few of the previous events I attended it happened to be quite dark. This was mostly because they took place in a club setting — like Noodlez and Hell-o-weenie’s drag event which I attended at Images 2 months prior.

(Noodlez at the drag event mentioned above.)

I took SO MANY photos at this event, and maybe only 10% of them were not a blurry mess. So, I used this night as an excuse to play with my camera and finally learn how to take good photos in poorly lit rooms. Like anyone trying to learn a skill, I passed my camera to my wife and asked if she could figure it out.

(Isobel the technology king.)

Isobel both made the camera take long exposure photos, as well as making the camera rapid-fire. We had no intention of creating a video from this, it was purely us playing around with the silly settings she had landed on.

This combination of long exposure and rapid images, when combined with the music weirdly replicates the experiences of drinking on a night out very well. Also, the jumping between different scenes replicates the gaps in memory people can have when thinking back to a night. Maybe this is just me telling on myself though for being a irresponsible drunk.

(A very responsible adult acting dignified and full of grace.)

I really like that a film like this records a moment in time and place. I know this could apply to any film, but this is more personal to me. The idea that Images has been saved in my work, like a boy scout sewing a patch, that represents an experience, to their sash is really exciting. I like that when I die (hopefully a long time from now) someone can look through my filmography and make informed guesses about my life. The fact that tiny parts of me that I do not personally intend to share fall off and get stuck in the frame is a nice way for one’s soul to exist in their work.

(My films as of 18/09/2024 — they are all slowly building a picture of what I have done, what I have read, who I have met, where I have been, etc. My journey is captured within.)

One of my favourite elements of this piece is the double meaning in the title:

After ‘Images’: the film goes through a night at the club ‘Images’, as well as what happens after being at Images.

Afterimages: this is an image that persists in one’s eye. By having the long exposure be the predominant feature of the piece, it in a way creates an afterimage trail of where the light was a few seconds prior.

You could also go into memories being after images too, and this night being a positive memory to me away from the filming aspect.

The piece ending with us catching the Sundial in town filled with bubbles is a nice touch. A classic Plymouth tradition being stumbled upon while on a night out. Many moons ago I was making a documentary on the Sundial, so it has a big place in my heart (I read too many articles on it and now its part of my DNA).

The music used in the film is ‘Big Room House’ by Paul Stitz — whenever I rewatch this thing, I am always jamming to the song. It was a lot of fun to edit to because it had lots of sharp beats that I used to control the pacing of the production. This adds a nice level of anticipation, moving on the music.

And that’s all I have to say on it I think. Hope this was an interesting read. Have a great day!

XOXO Gossip Girl

#AfterImagesFilm#ExperimentalFilm#LongExposure#NightclubAesthetic#ImagesPlymouth#AlternativeCulture#MemoryInFilm#InclusiveSpaces#AvantGardeCinema#ArtisticJourney#BlurryPhotography#MAExperienceDesign#PersonalNarrative#ImperfectCinema#DragEvent#AfterimageEffect#ClubPhotography#PlymouthArtScene#SoundAndFilm#FilmmakingExploration#Youtube

0 notes

Text

Filmes Considerados Quase Perfeitos

Filmes considerados quase perfeitos, você concorda com a lista que selecionamos aqui? Os desafios envolvidos na escrita, fotografia, edição e lançamento de um longa-metragem são extremamente complexos e rigorosos. Há vários fatores a serem considerados e mesmo com todo o esforço, não há garantias de que o filme será bem recebido pelo público ou sairá da maneira planejada pelos criadores. É por isso que filmes podem variar de terríveis a incríveis obras de arte. Os filmes mais memoráveis são aqueles que contaram com uma equipe excepcional, emocionaram o público e deixaram uma mensagem duradoura. Você concorda? Confira abaixo, a lista com os filmes mais aclamados dos últimos tempos, considerados quase perfeitos e deixe sua opinião.

O Grande Hotel Budapeste é Uma Obra-Prima De Wes Anderson

Nos anos 30, um gerente de hotel europeu se torna amigo de um jovem colega de trabalho. Juntos, eles roubam um quadro famoso e de valor inestimável e lutam por uma fortuna de família.

O filme é uma obra de arte cinematográfica que apresenta uma visão única da história europeia do século passado. A trama é habilmente tecida em torno da amizade improvável entre dois colegas de trabalho, que se envolvem em uma série de aventuras. O roubo do quadro famoso é apenas o começo de uma jornada cheia de reviravoltas e surpresas, que culmina em uma luta épica pela fortuna da família. Uma mistura perfeita de drama, comédia e suspense. Se você está procurando por um filme emocionante, inteligente e bem feito, não deixe de conferir esta obra-prima do cinema. Além da história envolvente, o filme também é visualmente deslumbrante. A recriação do cenário histórico da Europa dos anos 30 é impressionante, com figurinos e cenários impecáveis que transportam o espectador para a época retratada. A fotografia é excepcional, com planos e enquadramentos que realçam a beleza e a dramaticidade da trama. E a trilha sonora, composta especialmente para o filme, complementa perfeitamente as cenas e evoca as emoções necessárias em cada momento. No geral, este é um filme que agrada não só aos amantes de cinema, mas a todos que buscam uma experiência emocionante e divertida.

Manchester à Beira-Mar: Um Filme que Provoca Emoções Fortes

Filmes Considerados Quase Perfeitos Manchester à Beira-Mar não é um filme que se assiste para relaxar. Este drama, escrito e dirigido por Kenneth Lonergan, conta a história de Lee Chandler (Casey Affleck), que retorna à sua cidade natal após a morte de seu irmão.

Quando descobre que agora é o guardião do sobrinho adolescente, ele é forçado a confrontar seu passado e eventos traumáticos que nunca se curaram. Affleck e Lonergan ganharam o Oscar de Melhor Ator e Melhor Roteiro Original, respectivamente. Embora incrível, o filme evoca emoções que ninguém quer experimentar na vida real.

A Bruxa trouxe vida nova ao gênero de terror.

O filme "A Bruxa", dirigido por Robert Eggers, conta a história de uma família que, após ser banida da comunidade puritana de Plymouth, decide viver em uma fazenda na beira de uma grande floresta.

Quando seu filho desaparece misteriosamente, a família é manipulada por uma força sobrenatural na floresta, levando-os a se separarem. Para tornar o filme mais realista e aterrorizante, Eggers dedicou quatro anos de pesquisa para sua estreia como diretor. O elenco, composto por atores jovens e experientes, entregou performances excelentes, fundamentais para a iminente sensação de desgraça que o filme evoca.

O Labirinto do Fauno

Filmes Considerados Quase Perfeitos Pegue a pipoca e prepare-se para uma aventura emocionante! O aclamado diretor Guillermo del Toro criou uma fantasia sombria com "O Labirinto do Fauno", que se passa cinco anos após a Guerra Civil Espanhola.

A história segue a jovem protagonista Ofelia, enquanto ela interage com criaturas mágicas que a conduzem a seu destino final em um mundo mítico. O filme é elogiado por sua narrativa, efeitos visuais, fotografia e atuação, embora contenha momentos violentos e emocionalmente desgastantes. Ainda assim, é considerado um dos melhores trabalhos de Del Toro e é um tesouro para os amantes do cinema. Se você é fã de filmes de fantasia, "O Labirinto do Fauno" é uma escolha imperdível! Com uma trama envolvente que mistura realidade e mitologia, o filme é capaz de prender a atenção do espectador do início ao fim. Além disso, as criaturas mágicas apresentadas são muito bem construídas, o que contribui para a imersão na história. Não é à toa que o filme foi indicado a seis categorias do Oscar, incluindo Melhor Diretor e Melhor Roteiro Original. Se você ainda não assistiu, não perca mais tempo e embarque nessa emocionante jornada junto com Ofelia!

O Grande Lebowski - Dos irmãos Coen

Preparem-se para rir muito com o caos hilário do filme! O filme de comédia "O Grande Lebowski", escrito, dirigido e produzido pelos irmãos Coen, narra a incrível história de "The Dude" (interpretado por Jeff Bridges), que se vê preso em uma rede de mal-entendidos e planos fracassados.

A trama do filme é apresentada de forma desordenada, deixando o público tão confuso quanto o personagem principal enquanto ele tenta juntar as peças. Embora o enredo possa ser divertido, o que realmente torna o filme único são seus personagens excêntricos. O diálogo incrivelmente espirituoso e hilário destes personagens também fornece ao público um suprimento infinito de citações ridículas que somente os fãs do filme conseguem entender. Além disso, o filme conta com uma trilha sonora incrível, que mistura diferentes estilos musicais, desde o rock clássico até o jazz. A escolha musical dos irmãos Coen é sempre impecável, e em "O Grande Lebowski" não é diferente. A música ajuda a criar a atmosfera única do filme e nos transporta diretamente para o mundo dos personagens. Não perca a chance de ver esta obra-prima da comédia dos anos 90, um clássico cult que continua conquistando fãs ao redor do mundo, mesmo depois de mais de 20 anos do lançamento.

Cidade dos Sonhos: O Filme do Século

Filmes Considerados Quase Perfeitos Desde os primórdios do cinema, o surrealismo tem sido uma técnica explorada pelos cineastas, sendo inspirada em diversas formas de arte surrealista.

No filme "Cidade dos Sonhos", David Lynch mostra como essa técnica pode ser transmitida de maneira perfeita em um longa-metragem. Na verdade, o filme é equiparável a um sonho inquietante que confunde os limites entre a realidade e a imaginação. De acordo com o crítico de cinema Robert Eggers, o filme "trabalha diretamente nas emoções, como a música". Com suas diversas cenas memoráveis, o público fica grudado na tela, o que levou a BBC a nomeá-lo como o melhor filme do século 21 até o momento.

2001: Uma Odisseia no Espaço uma obra-prima da ficção científica

O filme, dirigido por Stanley Kubrick, foi inspirado no conto "The Sentinel" de Arthur C. Clarke. A história é sobre uma viagem espacial a Júpiter, acompanhada pelo computador artificialmente inteligente HAL, depois que um monólito preto foi descoberto afetando a evolução humana.

Embora o enredo seja fascinante, o que torna o filme excepcional é a sua precisão científica e os temas pesados de evolução, existencialismo, inteligência artificial e viagens espaciais. Mas, não se engane: a trama é apenas a ponta do iceberg que nos leva a refletir sobre muitas questões da atualidade. O filme é considerado pioneiro em efeitos especiais, com som e diálogo usados de forma moderada para criar uma atmosfera espacial. A precisão científica é impressionante, e o filme é frequentemente incluído em listas dos dez melhores filmes já feitos. É uma obra-prima da ficção científica e tem sido altamente influente na cultura popular.

Explorando o Filme "Ela"

Filmes Considerados Quase Perfeitos Her é um romance de ficção científica que foi escrito, dirigido e produzido por Spike Jonze. O filme conta a história de Theodore Twombly (interpretado por Joaquin Phoenix), um escritor solitário que está passando por um divórcio.

Na tentativa de combater a sua solidão, ele adquire um sistema operacional (interpretado por Scarlet Johansson) e acaba se apaixonando por ele. Com uma bela utilização de cores pastéis, cenas urbanas empoeiradas e uma trilha sonora impressionante, o público é transportado para o mundo de Twombly. A atuação incrível de Joaquin permite que o público se identifique com o personagem, experimentando suas emoções em primeira mão. A maneira como a sociedade é retratada no filme é tão realista que nos faz questionar se esse mundo está tão longe do nosso.

Análise de "Pulp Fiction" de Quentin Tarantino

Filmes Considerados Quase Perfeitos O aclamado Quentin Tarantino escreveu e dirigiu este filme, que conta com um elenco estelar liderado por Bruce Willis, Samuel L. Jackson, Uma Thurman e John Travolta, entre outros.

O filme apresenta uma série de histórias de crimes interligadas que ocorrem em Los Angeles. Embora a atuação do elenco seja impressionante, o que realmente diferencia Pulp Fiction de outros filmes é sua narrativa não linear. O enredo é construído de forma surpreendente, com cenas aparentemente desconexas que se juntam no final. Para tornar a experiência ainda mais memorável, Tarantino adiciona sua própria trilha sonora característica, que é muito familiar para os fãs.

O Enigma de Outro Mundo: Um Filme Clássico de Terror

O Enigma de Outro Mundo é um filme dirigido por John Carpenter e escrito por Bill Landcaster. A história segue um grupo de pesquisadores em uma área isolada da Antártica.

Enquanto eles exploram o local, descobrem "A Coisa", uma forma de vida desconhecida que tem a capacidade de se transformar em outros organismos. Quando "A Coisa" assume a forma dos pesquisadores, a paranoia toma conta de todos, tornando-os incapazes de confiar uns nos outros. Embora tenha recebido críticas negativas pelo cinismo e pelos efeitos especiais gráficos, com o tempo, as pessoas começaram a apreciar a complexidade e o valor do filme. Hoje, O Enigma de Outro Mundo é reconhecido como um dos mais importantes filmes de terror já produzidos, consolidando-se na história do cinema.

O Sucesso da Trilogia "O Senhor dos Anéis" O Retorno do Rei

Não é segredo pra ninguém que a adaptação cinematográfica da trilogia "O Senhor dos Anéis" por Peter Jackson foi um dos maiores empreendimentos na história do cinema.

No entanto, o resultado final justificou todo o investimento. O filme é grandioso em escala, com batalhas épicas, belíssima cinematografia e uma trilha sonora singular. "O Senhor dos Anéis" ocupa um lugar na lista dos filmes de maior bilheteria de todos os tempos. Ele conquistou 11 prêmios Oscar, incluindo Melhor Filme. Além de ser considerado o filme de fantasia mais influente de todos os tempos.

O Assassinato De Jesse James Pelo Covarde Robert Ford (2007) - Uma Abordagem Diferente do Faroeste

Apesar de subestimado na época, este filme é considerado um dos melhores do gênero faroeste. Diferentemente de outras obras, o enredo se concentra mais nos personagens do que nos tiroteios comuns.

Cada cena é uma verdadeira obra de arte, graças ao diretor de fotografia, Roger Deakins, que criou novas lentes para capturar as imagens perfeitas. A trama segue a história do bandido Jesse James (Brad Pitt) e suas batalhas psicológicas, bem como seu relacionamento com um admirador instável (Casey Affleck). Tamanha beleza não passou despercebida, já que o filme foi indicado ao Oscar de Melhor Fotografia.

Você Nunca Esteve Realmente Aqui: uma obra-prima sombria e singular

O filme "Você Nunca Esteve Realmente Aqui" gira em torno de Joe, um assassino contratado por um senador para resgatar sua filha de uma rede de tráfico sexual. No entanto, ele se vê envolvido em uma conspiração perigosa que ameaça sua vida.

Embora a premissa do filme pareça clichê, o tratamento dado aos personagens e a maneira como a trama subverte as expectativas é notável. Phoenix oferece uma interpretação incrível de seu personagem, mostrando seu sofrimento e ao mesmo tempo sua dedicação como filho e sua crueldade como assassino. São essas nuances e as reviravoltas surpreendentes que elevam o filme a um nível de excelência.

John Wick Muito Além de um Ex-assassino

O filme de ação "John Wick", estrelado por Keanu Reeves, é uma obra-prima que se destaca entre outros filmes do mesmo gênero. Com uma execução incrivelmente rápida, o filme é de tirar o fôlego.

Para se preparar para o papel, Reeves treinou oito horas por dia, cinco dias por semana, durante quatro meses, demonstrando que sua dedicação ao processo criativo é uma das razões para o sucesso. Embora a iluminação, os efeitos especiais e o enredo possam ser emocionantes, "John Wick" é muito mais do que um filme de ação padrão. Na verdade, a história é sobre um homem de luto que perdeu a única coisa que o conectava à sua esposa recentemente falecida. A profundidade emocional que o filme oferece é raramente vista em produções do gênero, tornando-o especialmente impactante.

Sangue Negro: Um Retrato Sombrio da Natureza Humana

O diretor Paul Thomas Anderson retrata a caça ao petróleo e a ganância financeira que ocorreram no final do século XIX no seu filme "Sangue Negro".

Com as estrelas Daniel Day-Lewis e Paul Dano, o filme aborda o impacto negativo do capitalismo na sociedade americana e as ações depravadas que a ganância pode levar as pessoas a cometer. O desempenho surpreendente de Day-Lewis é complementado pelas imagens de Robert Elswit e pelo roteiro de Anderson, criando um filme que é tão sombrio e sujo quanto o petróleo que retrata. Além do tema principal, o filme também aborda questões como a religião e a relação do homem com a natureza. O personagem de Paul Dano, um pregador carismático, representa a hipocrisia religiosa que muitas vezes justifica ações cruéis em nome de Deus. Já Day-Lewis interpreta um magnata do petróleo que, ao mesmo tempo em que é obcecado pelo sucesso financeiro, também sente uma conexão espiritual com a terra e a natureza, o que leva a uma tensão interna interessante em seu personagem. No geral, "Sangue Negro" é um filme denso e complexo, que exige atenção do espectador, mas que recompensa com uma história intrigante e bem contada. Se você gosta de filmes que provocam reflexão e análise crítica da sociedade, com certeza vale a pena conferir essa obra-prima do cinema contemporâneo.

Os Imperdoáveis: Um Filme do Velho Oeste que Desafia as Convenções

Clint Eastwood é um nome conhecido no gênero Velho Oeste, mas nunca foi um pistoleiro comum. Em "Os Imperdoáveis", um filme que ele estrelou e dirigiu, isso fica ainda mais evidente.

O filme retrata a história de um fora da lei aposentado, interpretado por Eastwood, que retorna para um último trabalho. O filme desafia as convenções dos tradicionais filmes de faroeste glorificando a violência. Eastwood oferece ao público uma experiência realista de como é matar e morrer, expondo a verdadeira feiura da violência.

Tubarão Continua Aterrorizando o Público

Se não fosse pela habilidade de Steven Spielberg e sua equipe, "Tubarão" teria sido apenas mais um filme de verão, que cairia na obscuridade na temporada seguinte.

No entanto, o filme se tornou um fenômeno cultural e permanece como um dos clássicos do cinema americano até hoje. Spielberg criou tensão de maneira magistral, acompanhado pela trilha sonora icônica de John William, o que resultou em um filme que superou as expectativas do público. Read the full article

#2001:UmaOdisseianoEspaço#abruxa#amazonprime#BrilhoEternodeumaMentesemLembranças#cidadedossonhos#Ela#filmes#filmesconsideradosquaseperfeitos#hbo#JohnWick#lancamentos#ManchesteràBeira-Mar#melhoresfilmes#netflix#OAssassinatoDeJesseJamesPeloCovardeRobertFord#OEnigmadeOutroMundo#ograndehotelbudapeste#OGrandeLebowski#OLabirintodoFauno#osenhordosanéis#osenhordosaneisoretornodorei#osimperdoaveis#pulpfiction#resumodefilmes#sanguenegro#silencio#tubarao#vocenuncaesteverealmenteaqui

0 notes

Text

The body is under threat in the city—The cinema is under threat in the city—The digital city is antipathetic to both ...

1.

In early 2016 I was standing in the ballroom of the Duke of Cornwall Hotel in Plymouth (UK), chatting with a kilted Dee Heddon, co-founder with Misha Myers of The Walking Library (see Heddon & Myers 2014), and waiting for a performance of a scabrous Pearl Williams routine by Roberta Mock, author of a key account of walking arts (2009, 7-23). Conversation drifted to films and Dee wondered what kind of resource for wandering a passion for movies might offer.

It was an appropriate space for Dee’s question. The ballroom is on the ground floor of the hotel, which rises to an impressive tower topped by a single room. It was to this room that Roberta’s partner, Paul, and I had gained access on a ‘vertigo walk’ some years previously. We had walked from Paul’s childhood home town of Saltash on the other side of the Hamoaze, a stretch of the River Tamar, into Plymouth. This involved us crossing high above the river gorge on the 1961 road bridge. Although he had crossed this bridge many hundreds of times by car and bus, Paul, susceptible to vertigo like myself, had never walked it before.

Having successfully negotiated the bridge, we sought out all the highest points in the city that we could access. The manager of the Duke of Cornwall led us up winding stairs and opened the room in the tower for us. A telescope stood at a window; above the bed (and this was after 9/11) hung a framed photograph of the twin towers of the World Trade Centre in New York. I might have thought of ‘Wolfen’ (1981), or the anachronistic underwater shot of the twin towers in Tim Burton’s 2001 ‘Planet of the Apes’, or ‘Man on Wire’ (2008) even, but the opening scene of Fulci’s ‘Zombi 2’/Zombie Flesh Eaters’ (1979) was how I immediately cross-referenced through film what I was feeling on coming into the room; to be precise, the moment when the music reaches its climax not for the monster, but for the Manhattan skyline. Flying in the face of Ivan Chtcheglov’s assertion that “[W]e are bored in the city, there is no longer any Temple of the Sun”, in Fulci’s movie solar rays spill from behind the twin towers, just as they have from behind the zombie cadaver. The two monoliths cancel each other out and the movie almost stalls before it can begin; landscape and body equally ruinous.

2.

I want to propose that by systematically drawing on such associations – of the ambience, shape or narrative of particular places with memories of movies – the effectiveness of a certain kind of political and critical walking can be enhanced. Ironically, this walking springs from the dérive of the Lettrists/situationists who, subsequent to their exploratory walking, developed a theory of the ‘Society of the Spectacle’, a deeply negative attitude to the predominance of the visual, and produced anti-art and anti-cinema works like ‘Hurlements En Favour De Sade’ (1952) in which the screen throughout is blank, either dazzling white or dark. While what follows skirts a narrow adherence to the asceticism of later situationist theory, drawing upon the Lettrist/situationist experimentation with art processes recovered in more recent publications such as McKenzie Wark’s trilogy (2008, 2011, 2103), it also implements the orthodox situationist technique of détournement, hacking up and depredating the movies drawn upon and redeploying their images, themes and narratives in ways that are often aggressively at odds with their makers’ intentions.

3.

The body is under threat in the city. The cinema is under threat in the city. The digital city is antipathetic to both. The cinema offers the urban walker a chance to return as an immanent and imaginative body to the city.

Stephen Barber, in considering the turbulent confluence of body, performance, film and digital screens, makes this damning assessment of the contemporary city: “[T]he city’s surface, as a scoured and excoriated environment.... precludes and voids the eruption of performance acts.... forming an exposed medium that is already maximally occupied with such visual Spectacles as digital image-screens transmitting corporate animations, along with saturated icons, insignia and hoardings.... surface has no space for the corporeal infiltration of performance, unless that performance is commissioned.... to fully serve corporate agendas” (2104, 89). Barber’s portrait of urban surface is extreme, but it explains the absurd policing of image-making and the suppression of the most innocuous of non-retail behaviours by mall security guards, the tendency, akin to conspiracy, among consumers to mistake advertising logos for ornament and the strange brutalist sculptural contraptions placed to inconvenience rough sleepers.