#Onmyodo

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Japanese Magick

Japanese spirituality and folk magick are deeply rooted in Shinto, Buddhism, and indigenous traditions that blend animism, kami (spirits), and ritual practices. While Japan does not have a historical "witchcraft" tradition in the Western sense, it has a rich magickal heritage that includes onmyodo (esoteric cosmology), shugendo (mountain asceticism), folk magick, and spiritual practices passed down through generations.

So, let's explore the key elements of Japanese witchcraft and magick, including history, deities and spirits, traditional magickal practices, and how modern practitioners integrate these elements into their craft.

Foundations of Japanese Magick

🏮Shinto (神道) – The Way of the Kami

Shinto is the indigenous spiritual tradition of Japan, centered on reverence for kami (divine spirits) found in nature, ancestors, and sacred places. Many Japanese magickal practices stem from Shinto beliefs and rituals.

Key Concepts in Shinto Magick:

• Kami (神) – Spirits or deities that inhabit all things, including trees, mountains, rivers, and animals.

• Purification (禊 Misogi & 祓 Harai) – Cleansing oneself or a space of impurities before engaging in spiritual work.

• Offerings (供え物) – Giving food, incense, or prayers to kami and spirits to seek blessings or protection.

• Omamori (お守り) – Charms that provide luck, protection, and blessings.

🏮Onmyodo (陰陽道) – The Way of Yin-Yang

Onmyodo is an ancient system of esoteric cosmology and divination based on Taoist principles of yin-yang and the five elements. Practitioners, known as onmyōji (陰陽師), were skilled in astrology, geomancy, exorcism, and protective magick.

Onmyodo Magick Includes:

• Divination (卜占) – Fortune-telling using astrology, geomancy, or sacred texts.

• Talismans (護符 Gofu / Ofuda) – Paper or wooden charms inscribed with sacred symbols or prayers for protection.

• Spirit Banishing (鬼払い Oni-barai) – Rituals to remove negative spirits and influences.

• Elemental Magic (五行 Gogyō) – The Five Elements (Wood, Fire, Earth, Metal, Water) used for balance and spellwork.

🏮Shugendo (修験道) – Mountain Asceticism

Shugendo is a mystical tradition that blends Shinto, Buddhism, and Taoism. Its practitioners, known as yamabushi (山伏), are mountain monks who engage in spiritual endurance training, chanting, and nature-based magick.

Shugendo Magical Practices:

• Nature-Based Rituals – Using waterfalls, mountains, and caves for spiritual cleansing and empowerment.

• Firewalking (火渡り Hi-watari) – Walking over fire as a purification ritual.

• Mantra Chanting (真言 Shingon) – Reciting sacred phrases to invoke deities and spirits.

Key Deities and Spirits in Japanese Witchcraft

🏮Major Kami Associated with Magick:

• Inari Okami (稲荷大神) – Kami of prosperity, agriculture, and fox spirits (kitsune). Often invoked for abundance and transformation magick.

• Tsukuyomi (月読命) – Moon deity, associated with night magick, divination, and intuition.

• Ame-no-Uzume (天宇受売命) – Goddess of dawn, joy, and ritual dance. Invoked for creativity and uplifting energy.

• Raijin & Fujin (雷神・風神) – Thunder and wind gods, called upon for storm magick and elemental work.

• Susanoo-no-Mikoto (須佐之男命) – Kami of storms, exorcism, and warrior energy.

🏮Yokai (妖怪) & Spirit Beings:

Japanese folklore is filled with supernatural creatures, some of which play a role in magick:

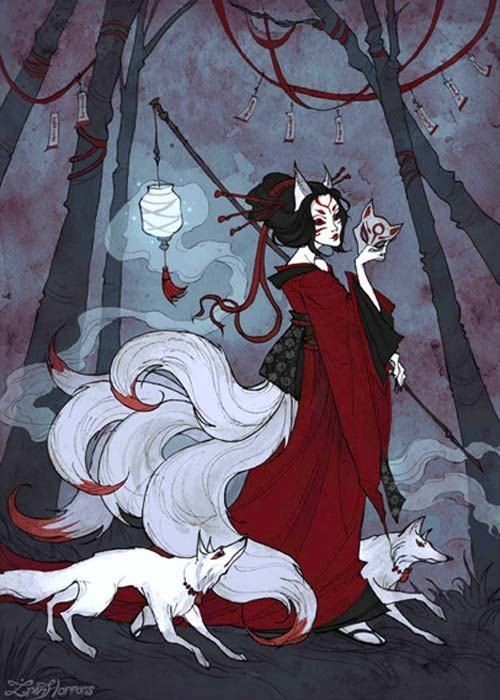

• Kitsune (狐) – Fox spirits associated with transformation, illusion, and trickery.

• Tengu (天狗) – Mountain spirits and warriors with powerful knowledge of magick and martial arts.

• Yurei (幽霊) – Ghosts and ancestral spirits that may require appeasement or exorcism.

Traditional Japanese Magickal Practices

🏮Divination & Fortune-Telling:

• Omikuji (おみくじ) – Paper fortunes drawn at shrines to reveal one's luck.

• I Ching (易経 Ekikyō) – Taoist divination practice adopted in Japan.

• Tenmon (天文) – Japanese astrology, used by onmyōji for predicting fate and auspicious times.

🏮Talisman & Charm Magick:

• Omamori (お守り) – Protective charms bought from shrines, charged with blessings from kami.

• Ofuda (御札) – Paper talismans often hung in homes for protection.

• Shide (紙垂) – Zigzag-shaped paper strips used in purification and shrine rituals.

🏮Protection & Banishing Spells

• Salt Purification (塩清め Shio-kiyome) – Sprinkling salt around spaces to remove negativity.

• Oni-barai (鬼払い) – Banishing rituals to drive away malevolent spirits.

• Suzu (鈴) – Small bells used to ward off bad spirits.

🏮Elemental & Nature Magick

• Waterfall Purification (滝行 Takigyo) – Ritual bathing in waterfalls to cleanse the spirit.

• Moon Rituals (月の魔法 Tsuki no Maho) – Working with lunar phases for manifestation and divination.

• Kitsune Magick – Calling upon fox spirits for wisdom, transformation, and trickster energy.

Modern Japanese Witchcraft & Contemporary Practices

While Japan does not have a strong tradition of "witchcraft" as seen in the West, modern witches and spiritual practitioners integrate traditional elements into their craft.

🏮Ways to Practice Japanese-Inspired Magick Today:

• Shrine Visits – Offering prayers and petitions to kami.

• Japanese Herbal Magick – Using plants like mugwort (ヨモギ yomogi) for protection and cleansing.

• Tea Rituals – Preparing and blessing tea with intentions for peace, health, and wisdom.

• Shinto-Inspired Spellwork – Creating small home altars (kamidana) for divine guidance.

• Combining Onmyodo with Western Practices – Blending astrology, talisman magic, and elemental balancing with modern witchcraft.

Japanese magick is deeply connected to nature, spirits, and ancestral traditions. While Japan does not have a direct equivalent to Western witchcraft, its spiritual and folk practices offer rich ways to work with energy, divination, and protection magick. Whether you are drawn to Shinto nature worship, onmyodo divination, or spirit work with yokai, Japanese magickal traditions provide a fascinating and profound path for spiritual exploration.

#japan#japanese#japanese mythology#shinto#Kami#onmyodo#kitsune#Oni#tsukuyomi#witch#magick#witchcraft#demons#witchblr#witch community#eclectic witch#eclectic#pagan#spellwork#divination#protection magic#talisman#charms#spirit#nature spirits#exorcism#protection#i ching#culture#Religion

72 notes

·

View notes

Text

I have a rather wide and eclectic range of pieces of art, fiction, and media that I enjoy / find compelling.

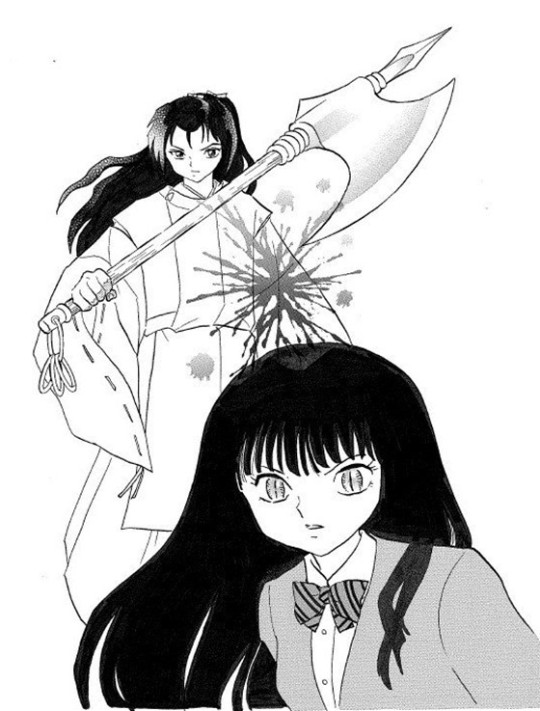

That being said I don't think any other piece of media will ever top the emotions I felt reading Tokyo Babylon.

The chapter where Subaru channels the spirit of a woman's deceased daughter in an attempt to dissuade her from committing revenge on her daughter's killer, expecting the child's spirit to simply want her mother to be at peace but finding out that it was scared and confused and angry and crying out for her mother to avenge her. Then as he is having to feel those emotions probably as if they were his own considering that he's acting as a psychic medium, as he lies to this grieving woman in a kind hearted but ultimately misguided attempt to provide her a form of closure that she herself was not searching for in the first place.

And doing this breaks Subaru in a way that I don't think he fully ever recovers from. Because he knows on some level what he did was wrong, and for him to then be consoled by Seishirou.............

Like the philosophical discussion on the morality of lying and how we deal with grief and tragedy and Injustice, that goes on between these two men and image of Seishirou putting an exhausted and psychologically worn down Subaru to bed in such a gentle and intimate way...........

AND HOW ALL OF THIS IS COMPLETELY TURNED ON ITS HEAD AND JUXTAPOSED WITH THE FINAL REVEAL OF WHO SEISHIROU REALLY IS AND WHAT HE DOES TO SUBARU AND HOW THIS CHANGES HIM AS A PERSON!!!!!!!!

I can't, I can't!!!! It's just literally the peak of art exploring the human experience!!!!!!! Literally nothing else will top it for me.

#clamp#clamp manga#tokyo babylon#yaoi#bl manga#subaru sumeragi#seishirou sakurazuka#tragic gays#onmyodo#I love these two gay onmyoji so much 🥺

60 notes

·

View notes

Text

Shikigami and onmyōdō through history: truth, fiction and everything in between

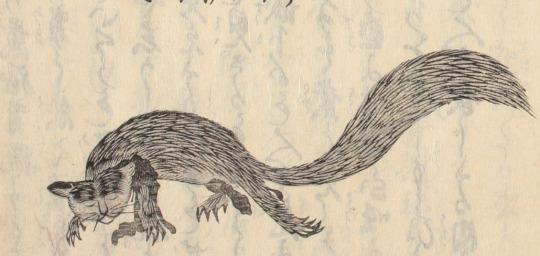

Abe no Seimei exorcising disease spirits (疫病神, yakubyōgami), as depicted in the Fudō Riyaku Engi Emaki. Two creatures who might be shikigami are visible in the bottom right corner (wikimedia commons; identification following Bernard Faure’s Rage and Ravage, pp. 57-58)

In popular culture, shikigami are basically synonymous with onmyōdō. Was this always the case, though? And what is a shikigami, anyway? These questions are surprisingly difficult to answer. I’ve been meaning to attempt to do so for a longer while, but other projects kept getting in the way. Under the cut, you will finally be able to learn all about this matter.

This isn’t just a shikigami article, though. Since historical context is a must, I also provide a brief history of onmyōdō and some of its luminaries. You will also learn if there were female onmyōji, when stars and time periods turn into deities, what onmyōdō has to do with a tale in which Zhong Kui became a king of a certain city in India - and more!

The early days of onmyōdō In order to at least attempt to explain what the term shikigami might have originally entailed, I first need to briefly summarize the history of onmyōdō (陰陽道). This term can be translated as “way of yin and yang”, and at the core it was a Japanese adaptation of the concepts of, well, yin and yang, as well as the five elements. They reached Japan through Daoist and Buddhist sources. Daoism itself never really became a distinct religion in Japan, but onmyōdō is arguably among the most widespread adaptations of its principles in Japanese context.

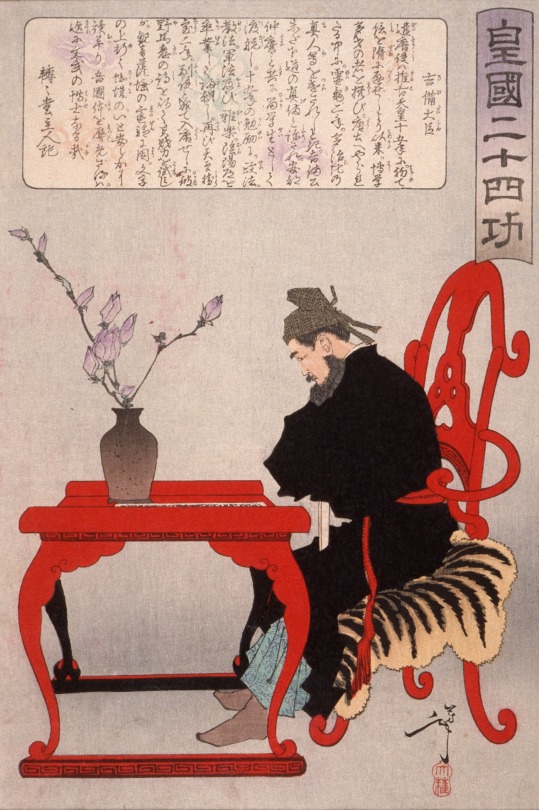

Kibi no Makibi, as depicted by Yoshitoshi Tsukioka (wikimedia commons)

It’s not possible to speak of a singular founder of onmyōdō comparable to the patriarchs of Buddhist schools. Bernard Faure notes that in legends the role is sometimes assigned to Kibi no Makibi, an eighth century official who spent around 20 years in China. While he did bring many astronomical treatises with him when he returned, this is ultimately just a legend which developed long after he passed away.

In reality onmyōdō developed gradually starting with the sixth century, when Chinese methods of divination and treatises dealing with these topics first reached Japan. Early on Buddhist monks from the Korean kingdom of Baekje were the main sources of this knowledge. We know for example that the Soga clan employed such a specialist, a certain Gwalleuk (観勒; alternatively known under the Japanese reading of his name, Kanroku).

Obviously, divination was viewed as a very serious affair, so the imperial court aimed to regulate the continental techniques in some way. This was accomplished by emperor Tenmu with the formation of the onmyōryō (陰陽寮), “bureau of yin and yang” as a part of the ritsuryō system of governance. Much like in China, the need to control divination was driven by the fears that otherwise it would be used to legitimize courtly intrigues against the emperor, rebellions and other disturbances. Officials taught and employed by onmyōryō were referred to as onmyōji (陰陽師). This term can be literally translated as “yin-yang master”. In the Nara period, they were understood essentially as a class of public servants. Their position didn’t substantially differ from that of other specialists from the onmyōryō: calendar makers, officials responsible for proper measurement of time and astrologers. The topics they dealt with evidently weren’t well known among commoners, and they were simply typical members of the literate administrative elite of their times.

Onmyōdō in the Heian period: magic, charisma and nobility

The role of onmyōji changed in the Heian period. They retained the position of official bureaucratic diviners in employ of the court, but they also acquired new duties. The distinction between them and other onmyōryō officials became blurred. Additionally their activity extended to what was collectively referred to as jujutsu (呪術), something like “magic” though this does not fully reflect the nuances of this term. They presided over rainmaking rituals, purification ceremonies, so-called “earth quelling”, and establishing complex networks of temporal and directional taboos.

A Muromachi period depiction of Abe no Seimei (wikimedia commons)

The most famous historical onmyōji like Kamo no Yasunori and his student Abe no Seimei were active at a time when this version of onmyōdō was a fully formed - though obviously still evolving - set of practices and beliefs. In a way they represented a new approach, though - one in which personal charisma seemed to matter just as much, if not more, than official position. This change was recognized as a breakthrough by at least some of their contemporaries. For example, according to the diary of Minamoto no Tsuneyori, the Sakeiki (左經記), “in Japan, the foundations of onmyōdō were laid by Yasunori”.

The changes in part reflected the fact that onmyōji started to be privately contracted for various reasons by aristocrats, in addition to serving the state. Shin’ichi Shigeta notes that it essentially turned them from civil servants into tradespeople. However, he stresses they cannot be considered clergymen: their position was more comparable to that of physicians, and there is no indication they viewed their activities as a distinct religion. Indeed, we know of multiple Heian onmyōji, like Koremune no Fumitaka or Kamo no Ieyoshi, who by their own admission were devout Buddhists who just happened to work as professional diviners.

Shin’ichi Shigeta notes is evidence that in addition to the official, state-sanctioned onmyōji, “unlicensed” onmyōji who acted and dressed like Buddhist clergy, hōshi onmyōji (法師陰陽師) existed. The best known example is Ashiya Dōman, a mainstay of Seimei legends, but others are mentioned in diaries, including the famous Pillow Book. It seems nobles particularly commonly employed them to curse rivals. This was a sphere official onmyōji abstained from due to legal regulations. Curses were effectively considered crimes, and government officials only performed apotropaic rituals meant to protect from them. The Heian period version of onmyōdō captivated the imagination of writers and artists, and its slightly exaggerated version present in classic literature like Konjaku Monogatari is essentially what modern portrayals in fiction tend to go back to.

Medieval onmyōdō: from abstract concepts to deities

Gozu Tennō (wikimedia commons)

Further important developments occurred between the twelfth and fourteenth centuries. This period was the beginning of the Japanese “middle ages” which lasted all the way up to the establishment of the Tokugawa shogunate. The focus in onmyōdō in part shifted towards new, or at least reinvented, deities, such as calendarical spirits like Daishōgun (大将軍) and Ten’ichijin (天一神), personifications of astral bodies and concepts already crucial in earlier ceremonies. There was also an increased interest in Chinese cosmological figures like Pangu, reimagined in Japan as “king Banko”. However, the most famous example is arguably Gozu Tennō, who you might remember from my Susanoo article.

The changes in medieval onmyōdō can be described as a process of convergence with esoteric Buddhism. The points of connection were rituals focused on astral and underworld deities, such as Taizan Fukun or Shimei (Chinese Siming). Parallels can be drawn between this phenomenon and the intersection between esoteric Buddhism and some Daoist schools in Tang China. Early signs of the development of a direct connection between onmyōdō and Buddhism can already be found in sources from the Heian period, for example Kamo no Yasunori remarked that he and other onmyōji depend on the same sources to gain proper understanding of ceremonies focused on the Big Dipper as Shingon monks do.

Much of the information pertaining to the medieval form of onmyōdō is preserved in Hoki Naiden (ほき内伝; “Inner Tradition of the Square and the Round Offering Vessels”), a text which is part divination manual and part a collection of myths. According to tradition it was compiled by Abe no Seimei, though researchers generally date it to the fourteenth century. For what it’s worth, it does seem likely its author was a descendant of Seimei, though. Outside of specialized scholarship Hoki Naiden is fairly obscure today, but it’s worth noting that it was a major part of the popular perception of onmyōdō in the Edo period. A novel whose influence is still visible in the modern image of Seimei, Abe no Seimei Monogatari (安部晴明物語), essentially revolves around it, for instance.

Onmyōdō in the Edo period: occupational licensing

Novels aside, the first post-medieval major turning point for the history of onmyōdō was the recognition of the Tsuchimikado family as its official overseers in 1683. They were by no means new to the scene - onmyōji from this family already served the Ashikaga shoguns over 250 years earlier. On top of that, they were descendants of the earlier Abe family, the onmyōji par excellence. The change was not quite the Tsuchimikado’s rise, but rather the fact the government entrusted them with essentially regulating occupational licensing for all onmyōji, even those who in earlier periods existed outside of official administration.

As a result of the new policies, various freelance practitioners could, at least in theory, obtain a permit to perform the duties of an onmyōji. However, as the influence of the Tsuchimikado expanded, they also sought to oblige various specialists who would not be considered onmyōji otherwise to purchase licenses from them. Their aim was to essentially bring all forms of divination under their control. This extended to clergy like Buddhist monks, shugenja and shrine priests on one hand, and to various performers like members of kagura troupes on the other.

Makoto Hayashi points out that while throughout history onmyōji has conventionally been considered a male occupation, it was possible for women to obtain licenses from the Tsuchimikado. Furthermore, there was no distinct term for female onmyōji, in contrast with how female counterparts of Buddhist monks, shrine priests and shugenja were referred to with different terms and had distinct roles defined by their gender. As far as I know there’s no earlier evidence for female onmyōji, though, so it’s safe to say their emergence had a lot to do with the specifics of the new system. It seems the poems of the daughter of Kamo no Yasunori (her own name is unknown) indicate she was familiar with yin-yang theory or at least more broadly with Chinese philosophy, but that’s a topic for a separate article (stay tuned), and it's not quite the same, obviously.

The Tsuchimikado didn’t aim to create a specific ideology or systems of beliefs. Therefore, individual onmyōji - or, to be more accurate, individual people with onmyōji licenses - in theory could pursue new ideas. This in some cases lead to controversies: for instance, some of the people involved in the (in)famous 1827 Osaka trial of alleged Christians (whether this label really is applicable is a matter of heated debate) were officially licensed onmyōji. Some of them did indeed possess translated books written by Portuguese missionaries, which obviously reflected Catholic outlook. However, Bernard Faure suggests that some of the Edo period onmyōji might have pursued Portuguese sources not strictly because of an interest in Catholicism but simply to obtain another source of astronomical knowledge.

The legacy of onmyōdō

In the Meiji period, onmyōdō was banned alongside shugendō. While the latter tradition experienced a revival in the second half of the twentieth century, the former for the most part didn’t. However, that doesn’t mean the history of onmyōdō ends once and for all in the second half of the nineteenth century.

Even today in some parts of Japan there are local religious traditions which, while not identical with historical onmyōdō, retain a considerable degree of influence from it. An example often cited in scholarship is Izanagi-ryū (いざなぎ流) from the rural Monobe area in the Kōchi Prefecture. Mitsuki Ueno stresses that the occasional references to Izanagi-ryū as “modern onmyōdō” in literature from the 1990s and early 2000s are inaccurate, though. He points out they downplay the unique character of this tradition, and that it shows a variety of influences. Similar arguments have also been made regarding local traditions from the Chūgoku region.

Until relatively recently, in scholarship onmyōdō was basically ignored as superstition unworthy of serious inquiries. This changed in the final decades of the twentieth century, with growing focus on the Japanese middle ages among researchers. The first monographs on onmyōdō were published in the 1980s. While it’s not equally popular as a subject of research as esoteric Buddhism and shugendō, formerly neglected for similar reasons, it has nonetheless managed to become a mainstay of inquiries pertaining to the history of religion in Japan.

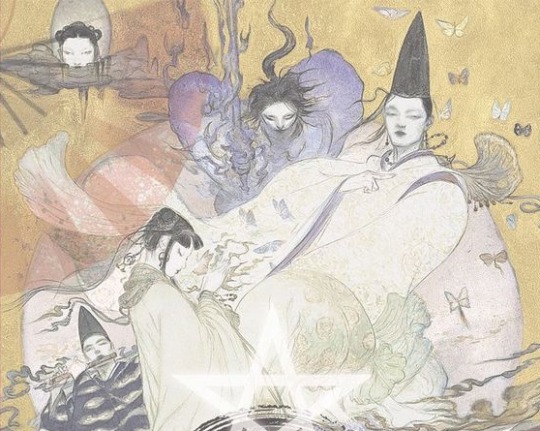

Yoshitaka Amano's illustration of Baku Yumemakura's fictionalized portrayal of Abe no Seimei (right) and other characters from his novels (reproduced here for educational purposes only)

Of course, it’s also impossible to talk about onmyōdō without mentioning the modern “onmyōdō boom”. Starting with the 1980s, onmyōdō once again became a relatively popular topic among writers. Novel series such as Baku Yumemakura’s Onmyōji, Hiroshi Aramata’s Teito Monogatari or Natsuhiko Kyōgoku’s Kyōgōkudō and their adaptations in other media once again popularized it among general audiences. Of course, since these are fantasy or mystery novels, their historical accuracy tends to vary (Yumemakura in particular is reasonably faithful to historical literature, though). Still, they have a lasting impact which would be impossible to accomplish with scholarship alone.

Shikigami: historical truth, historical fiction, or both?

You might have noticed that despite promising a history of shikigami, I haven’t used this term even once through the entire crash course in history of onmyōdō. This was a conscious choice. Shikigami do not appear in any onmyōdō texts, even though they are a mainstay of texts about onmyōdō, and especially of modern literature involving onmyōji.

It would be unfair to say shikigami and their prominence are merely a modern misconception, though. Virtually all of the famous legends about onmyōji feature shikigami, starting with the earliest examples from the eleventh century. Based on Konjaku Monogatari, there evidently was a fascination with shikigami at the time of its compilation. Fujiwara no Akihira in the Shinsarugakuki treats the control of shikigami as an essential skill of an onmyōji, alongside the abilities to “freely summon the twelve guardian deities, call thirty-six types of wild birds (...), create spells and talismans, open and close the eyes of kijin (鬼神; “demon gods”), and manipulate human souls”.

It is generally agreed that such accounts, even though they belong to the realm of literary fiction, can shed light on the nature and importance of shikigami. They ultimately reflect their historical context to some degree. Furthermore, it is not impossible that popular understanding of shikigami based on literary texts influenced genuine onmyōdō tradition. It’s worth pointing out that today legends about Abe no Seimei involving them are disseminated by two contemporary shrines dedicated to him, the Seimei Shrine (晴明神社) in Kyoto and the Abe no Seimei Shrine (安倍晴明神社) in Osaka. Interconnected networks of exchange between literature and religious practice are hardly a unique or modern phenomenon.

However, even with possible evidence from historical literature taken into account, it is not easy to define shikigami. The word itself can be written in three different ways: 式神 (or just 式), 識神 and 職神, with the first being the default option. The descriptions are even more varied, which understandably lead to the rise of numerous interpretations in modern scholarship. Carolyn Pang in her recent treatments of shikigami, which you can find in the bibliography, has recently divided them into five categories. I will follow her classification below.

Shikigami take 1: rikujin-shikisen

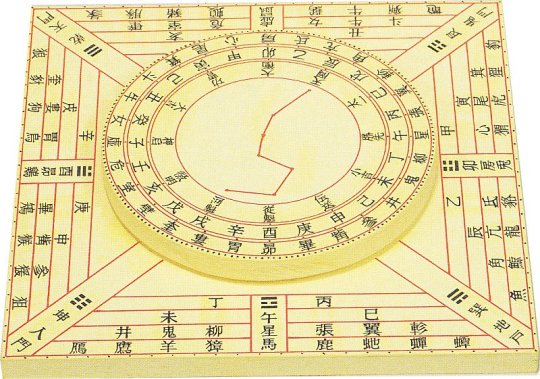

An example of shikiban, the divination board used in rikujin-shikisen (Museum of Kyoto, via onmarkproductions.com; reproduced here for educational purposes only)

A common view is that shikigami originate as a symbolic representation of the power of shikisen (式占) or more specifically rikujin-shikisen (六壬式占), the most common form of divination in onmyōdō. It developed from Chinese divination methods in the Nara period, and remained in the vogue all the way up to the sixteenth century, when it was replaced by ekisen (易占), a method derived from the Chinese Book of Changes.

Shikisen required a special divination board known as shikiban (式盤), which consists of a square base, the “earth panel” (地盤, jiban), and a rotating circle placed on top of it, the “heaven panel” (天盤, tenban). The former was marked with twelve points representing the signs of the zodiac and the latter with representations of the “twelve guardians of the months” (十二月将, jūni-gatsushō; their identity is not well defined). The heaven panel had to be rotated, and the diviner had to interpret what the resulting combination of symbols represents. Most commonly, it was treated as an indication whether an unusual phenomenon (怪/恠, ke) had positive or negative implications. It’s worth pointing out that in the middle ages the shikiban also came to be used in some esoteric Buddhist rituals, chiefly these focused on Dakiniten, Shōten and Nyoirin Kannon. However, they were only performed between the late Heian and Muromachi periods, and relatively little is known about them. In most cases the divination board was most likely modified to reference the appropriate esoteric deities.

Shikigami take 2: cognitive abilities

While the view that shikigami represented shikisen is strengthened by the fact both terms share the kanji 式, a variant writing, 識神, lead to the development of another proposal. Since the basic meaning of 識 is “consciousness”, it is sometimes argued that shikigami were originally an “anthropomorphic realization of the active psychological or mental state”, as Caroline Pang put it - essentially, a representation of the will of an onmyōji. Most of the potential evidence in this case comes from Buddhist texts, such as Bosatsushotaikyō (菩薩処胎経).

However, Bernard Faure assumes that the writing 識神 was a secondary reinterpretation, basically a wordplay based on homonymy. He points out the Buddhist sources treat this writing of shikigami as a synonym of kushōjin (倶生神). This term can be literally translated as “deities born at the same time”. Most commonly it designates a pair of minor deities who, as their name indicates, come into existence when a person is born, and then records their deeds through their entire life. Once the time for Enma’s judgment after death comes, they present him with their compiled records. It has been argued that they essentially function like a personification of conscience.

Shikigami take 3: energy

A further speculative interpretation of shikigami in scholarship is that this term was understood as a type of energy present in objects or living beings which onmyōji were believed to be capable of drawing out and harnessing to their ends. This could be an adaptation of the Daoist notion of qi (��). If this definition is correct, pieces of paper or wooden instruments used in purification ceremonies might be examples of objects utilized to channel shikigami.

The interpretation of shikigami as a form of energy is possibly reflected in Konjaku Monogatari in the tale The Tutelage of Abe no Seimei under Tadayuki. It revolves around Abe no Seimei’s visit to the house of the Buddhist monk Kuwanten from Hirosawa. Another of his guests asks Seimei if he is capable of killing a person with his powers, and if he possesses shikigami. He affirms that this is possible, but makes it clear that it is not an easy task. Since the guests keep urging him to demonstrate nonetheless, he promptly demonstrates it using a blade of grass. Once it falls on a frog, the animal is instantly crushed to death. From the same tale we learn that Seimei’s control over shikigami also let him remotely close the doors and shutters in his house while nobody was inside.

Shikigami take 4: curse As I already mentioned, arts which can be broadly described as magic - like the already mentioned jujutsu or juhō (呪法, “magic rituals”) - were regarded as a core part of onmyōji’s repertoire from the Heian period onward. On top of that, the unlicensed onmyōji were almost exclusively associated with curses. Therefore, it probably won’t surprise you to learn that yet another theory suggests shikigami is simply a term for spells, curses or both. A possible example can be found in Konjaku Monogatari, in the tale Seimei sealing the young Archivist Minor Captains curse - the eponymous curse, which Seimei overcomes with protective rituals, is described as a shikigami.

Kunisuda Utagawa's illustration of an actor portraying Dōman in a kabuki play (wikimedia commons)

Similarities between certain descriptions of shikigami and practices such as fuko (巫蠱) and goraihō (五雷法) have been pointed out. Both of these originate in China. Fuko is the use of poisonous, venomous or otherwise negatively perceived animals to create curses, typically by putting them in jars, while goraihō is the Japanese version of Daoist spells meant to control supernatural beings, typically ghosts or foxes. It’s worth noting that a legend according to which Dōman cursed Fujiwara no Michinaga on behalf of lord Horikawa (Fujiwara no Akimitsu) involves him placing the curse - which is itself not described in detail - inside a jar.

Mitsuki Ueno notes that in the Kōchi Prefecture the phrase shiki wo utsu, “to strike with a shiki”, is still used to refer to cursing someone. However, shiki does not necessarily refer to shikigami in this context, but rather to a related but distinct concept - more on that later.

Shikigami take 5: supernatural being

While all four definitions I went through have their proponents, yet another option is by far the most common - the notion of shikigami being supernatural beings controlled by an onmyōji. This is essentially the standard understanding of the term today among general audiences. Sometimes attempts are made to identify it with a specific category of supernatural beings, like spirits (精霊, seirei), kijin or lesser deities (下級神, kakyū shin). However, none of these gained universal support. Generally speaking, there is no strong indication that shikigami were necessarily imagined as individualized beings with distinct traits.

The notion of shikigami being supernatural beings is not just a modern interpretation, though, for the sake of clarity. An early example where the term is unambiguously used this way is a tale from Ōkagami in which Seimei sends a nondescript shikigami to gather information. The entity, who is not described in detail, possesses supernatural skills, but simultaneously still needs to open doors and physically travel.

An illustration from Nakifudō Engi Emaki (wikimedia commons)

In Genpei Jōsuiki there is a reference to Seimei’s shikigami having a terrifying appearance which unnerved his wife so much he had to order the entities to hide under a bride instead of residing in his house. Carolyn Pang suggests that this reflects the demon-like depictions from works such as Abe no Seimei-kō Gazō (安倍晴明公画像; you can see it in the Heian section), Fudōriyaku Engi Emaki and Nakifudō Engi Emaki.

Shikigami and related concepts

A gohō dōji, as depicted in the Shigisan Engi Emaki (wikimedia commons)

The understanding of shikigami as a “spirit servant” of sorts can be compared with the Buddhist concept of minor protective deities, gohō dōji (護法童子; literally “dharma-protecting lads”). These in turn were just one example of the broad category of gohō (護法), which could be applied to virtually any deity with protective qualities, like the historical Buddha’s defender Vajrapāṇi or the Four Heavenly Kings. A notable difference between shikigami and gohō is the fact that the former generally required active summoning - through chanting spells and using mudras - while the latter manifested on their own in order to protect the pious. Granted, there are exceptions. There is a well attested legend according to which Abe no Seimei’s shikigami continued to protect his residence on own accord even after he passed away. Shikigami acting on their own are also mentioned in Zoku Kojidan (続古事談). It attributes the political downfall of Minamoto no Takaakira (源高明; 914–98) to his encounter with two shikigami who were left behind after the onmyōji who originally summoned them forgot about them.

A degree of overlap between various classes of supernatural helpers is evident in texts which refer to specific Buddhist figures as shikigami. I already brought up the case of the kushōjin earlier. Another good example is the Tendai monk Kōshū’s (光宗; 1276–1350) description of Oto Gohō (乙護法). He is “a shikigami that follows us like the shadow follows the body. Day or night, he never withdraws; he is the shikigami that protects us” (translation by Bernard Faure). This description is essentially a reversal of the relatively common title “demon who constantly follow beings” (常随魔, jōzuima). It was applied to figures such as Kōjin, Shōten or Matarajin, who were constantly waiting for a chance to obstruct rebirth in a pure land if not placated properly.

The Twelve Heavenly Generals (Tokyo National Museum, via wikimedia commons)

A well attested group of gohō, the Twelve Heavenly Generals (十二神将, jūni shinshō), and especially their leader Konpira (who you might remember from my previous article), could be labeled as shikigami. However, Fujiwara no Akihira’s description of onmyōji skills evidently presents them as two distinct classes of beings.

A kuda-gitsune, as depicted in Shōzan Chomon Kishū by Miyoshi Shōzan (Waseda University History Museum; reproduced here for educational purposes only)

Granted, Akihira also makes it clear that controlling shikigami and animals are two separate skills. Meanwhile, there is evidence that in some cases animal familiars, especially kuda-gitsune used by iizuna (a term referring to shugenja associated with the cult of, nomen omen, Iizuna Gongen, though more broadly also something along the lines of “sorcerer”), were perceived as shikigami.

Beliefs pertaining to gohō dōji and shikigami seemingly merged in Izanagi-ryū, which lead to the rise of the notion of shikiōji (式王子; ōji, literally “prince”, can be another term for gohō dōji). This term refers to supernatural beings summoned by a ritual specialist (祈祷師, kitōshi) using a special formula from doctrinal texts (法文, hōmon). They can fulfill various functions, though most commonly they are invoked to protect a person, to remove supernatural sources of diseases, to counter the influence of another shikiōji or in relation to curses.

Tenkeisei, the god of shikigami

Tenkeisei (wikimedia commons)

The final matter which warrants some discussion is the unusual tradition regarding the origin of shikigami which revolves around a deity associated with this concept.

In the middle ages, a belief that there were exactly eighty four thousand shikigami developed. Their source was the god Tenkeisei (天刑星; also known as Tengyōshō). His name is the Japanese reading of Chinese Tianxingxing. It can be translated as “star of heavenly punishment”. This name fairly accurately explains his character. He was regarded as one of the so-called “baleful stars” (凶星, xiong xing) capable of controlling destiny. The “punishment” his name refers to is his treatment of disease demons (疫鬼, ekiki). However, he could punish humans too if not worshiped properly.

Today Tenkeisei is best known as one of the deities depicted in a series of paintings known as Extermination of Evil, dated to the end of the twelfth century. He has the appearance of a fairly standard multi-armed Buddhist deity. The anonymous painter added a darkly humorous touch by depicting him right as he dips one of the defeated demons in vinegar before eating him. Curiously, his adversaries are said to be Gozu Tennō and his retinue in the accompanying text. This, as you will quickly learn, is a rather unusual portrayal of the relationship between these two deities.

I’m actually not aware of any other depictions of Tenkeisei than the painting you can see above. Katja Triplett notes that onmyōdō rituals associated with him were likely surrounded by an aura of secrecy, and as a result most depictions of him were likely lost or destroyed. At the same time, it seems Tenkeisei enjoyed considerable popularity through the Kamakura period. This is not actually paradoxical when you take the historical context into account: as I outlined in my recent Amaterasu article, certain categories of knowledge were labeled as secret not to make their dissemination forbidden, but to imbue them with more meaning and value.

Numerous talismans inscribed with Tenkeisei’s name are known. Furthermore, manuals of rituals focused on him have been discovered. The best known of them, Tenkeisei-hō (天刑星法; “Tenkeisei rituals”), focuses on an abisha (阿尾捨, from Sanskrit āveśa), a ritual involving possession by the invoked deity. According to a legend was transmitted by Kibi no Makibi and Kamo no Yasunori. The historicity of this claim is doubtful, though: the legend has Kamo no Yasunori visit China, which he never did. Most likely mentioning him and Makibi was just a way to provide the text with additional legitimacy.

Other examples of similar Tenkeisei manuals include Tenkeisei Gyōhō (天刑星行法; “Methods of Tenkeisei Practice”) and Tenkeisei Gyōhō Shidai (天刑星行法次第; “Methods of Procedure for the Tenkeisei Practice”). Copies of these texts have been preserved in the Shingon temple Kōzan-ji.

The Hoki Naiden also mentions Tenkeisei. It equates him with Gozu Tennō, and explains both of these names refer to the same deity, Shōki (商貴), respectively in heaven and on earth. While Shōki is an adaptation of the famous Zhong Kui, it needs to be pointed out that here he is described not as a Tang period physician but as an ancient king of Rajgir in India. Furthermore, he is a yaksha, not a human. This fairly unique reinterpretation is also known from the historical treatise Genkō Shakusho. Post scriptum The goal of this article was never to define shikigami. In the light of modern scholarship, it’s basically impossible to provide a single definition in the first place. My aim was different: to illustrate that context is vital when it comes to understanding obscure historical terms. Through history, shikigami evidently meant slightly different things to different people, as reflected in literature. However, this meaning was nonetheless consistently rooted in the evolving perception of onmyōdō - and its internal changes. In other words, it reflected a world which was fundamentally alive. The popular image of Japanese culture and religion is often that of an artificial, unchanging landscape straight from the “age of the gods”, largely invented in the nineteenth century or later to further less than noble goals. The case of shikigami proves it doesn’t need to be, though. The malleable, ever-changing image of shikigami, which remained a subject of popular speculation for centuries before reemerging in a similar role in modern times, proves that the more complex reality isn’t necessarily any less interesting to new audiences.

Bibliography

Bernard Faure, A Religion in Search of a Founder?

Idem, Rage and Ravage (Gods of Medieval Japan vol. 3)

Makoto Hayashi, The Female Christian Yin-Yang Master

Jun’ichi Koike, Onmyōdō and Folkloric Culture: Three Perspectives for the Development of Research

Irene H. Lin, Child Guardian Spirits (Gohō Dōji) in the Medieval Japanese Imaginaire

Yoshifumi Nishioka, Aspects of Shikiban-Based Mikkyō Rituals

Herman Ooms, Yin-Yang's Changing Clientele, 600-800 (note there is n apparent mistake in one of the footnotes, I'm pretty sure the author wanted to write Mesopotamian astronomy originated 4000 years ago, not 4 millenia BCE as he did; the latter date makes little sense)

Carolyn Pang, Spirit Servant: Narratives of Shikigami and Onmyōdō Developments

Idem, Uncovering Shikigami. The Search for the Spirit Servant of Onmyōdō

Shin’ichi Shigeta, Onmyōdō and the Aristocratic Culture of Everyday Life in Heian Japan

Idem, A Portrait of Abe no Seimei

Katja Triplett, Putting a Face on the Pathogen and Its Nemesis. Images of Tenkeisei and Gozutennō, Epidemic-Related Demons and Gods in Medieval Japan

Mitsuki Umeno, The Origins of the Izanagi-ryū Ritual Techniques: On the Basis of the Izanagi saimon

Katsuaki Yamashita, The Characteristics of On'yōdō and Related Texts

191 notes

·

View notes

Text

Because the idea won't leave my brain, I made some more drawings and ideas.

First off - The Seiman/Pentagram features HEAVILY in the nation's technology, most significantly in the Seiman unit - a sort of combination reactor/CPU. Full-scale ones are complex, generally used for large-scale operations like ships. (As a side effect, engineers from this nation generally expect power systems and core computer systems to be in the same room.) Smaller ones are used for things like vehicles or even personal items.

Combat talismans generally feature a Pentagram in the center, with a character in the middle of that determining what element a particular technique will be. The ones you saw on the previous post would be "utility" talismans.

The Kujiin limiter system is specifically for those who utilize their equivalent of the Jade system - specifically, it caps the amount of Ki a user can draw upon to prevent themselves from being exhausted due to expenditure - or worse. Disabling it is an intensive process to prevent arbitrary usage. (And even then, the passphrase and gestures to even turn it off are usually kept secret to make sure some idiot doesn't accidentally kill themselves trying to show off.) Before you ask, yes, it's the whole Rin-Pyo-To-Sha-etc... thing.

(Once again, credit to @kai7kh for putting the idea in my head to begin with)

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chapter 2: Shrines, Myths, and Rituals in Premodern Times

The Jingi Cult and Yin-Yang Ritual

Yin-Yang divination had been brought to Japan by Korean immigrants long before the age of Tenmu and Jitō… In fact the title of tennō itself was originally a term of Yin-Yang astronomy, referring to the Pole Star as the stationary axis of the rotating universe. In parallel with the Council of Kami Affairs, the court also set up a Bureau of Yin and Yang (On’yōryō) that specialized in Yin-Yang divination, astronomy, calendar making, and time keeping. These activities of this Bureau staged the emperor as a cosmic being responsible for maintaining the delicate equilibrium between Yin and Yang, and thus securing the safety and prosperity of the realm… Of course, the Kami of heaven and the earth were also part of this cosmic balance, and the findings… had a direct bearing on the activities of the Council of Kami Affairs…. Yang-Yang rites overlapped with jingi ceremonial…

Jingi ritual drew most heavily on Yin-Yang expertise in matters related to exorcism and the protection of the emperor and his capital…

In the eighth and Ninth centuries, Yin-Yang-style rituals of pacification (chinsai) and purification (harae) rose rapidly in importance as the court was shaken by political infighting, natural disasters, and, especially, deadly epidemics on an unprecedented scale. Yin-Yang techniques were soon adapted to serve the private needs of courtiers, and gradually spread further to the population at large, where they… had a profound impact on shrine cults.

—Pages 36-38

The Jingi Cult and Buddhism

Both the court and local elites cherished Buddhism for its ability to control the violence of deities, spirits, and demons of all kinds, including the kami. Usually, this entailed building temples next to shrines, where monks dedicated themselves to the conversion of the kami by exposing them to the Buddha’s benign teachings. By reciting sutras, and other Buddhist practices, these monks created merit or good karma, which was transferred to the kami in the hope that this would… “increase their power, and thus cause the Buddha-Dharma to flourish, wind and rain to moisten the earth at the right times, and the five kinds of grains to produce good crops.”…

—Page 39

The Shrines of Ise were not of the yashiro type: they were not temporary constructions to which deities were invited from some other location for the duration of a ritual. Rather, they were residences of human-like beings. These shrines were called miya, “venerable dwellings,” and the gods who resided in them were served with food and given clothing and other goods throughout the year.

—Page 39

The principle that worship of the heavenly and earthly deities was the prime task of the emperor was expressed in numerous tangible ways: for example, by banning Buddhist ceremonies in the first week of the year… The taboo on Buddhism in connection with the jingi cult, especially at Ise, generated much ritual friction and theological reflection. It is perhaps possible to argue that this policy foreshadowed the separation of Shinto from Buddhism that began in the Edo period and culminated in 1868; at the time… it was a formalistic measure with little or no impact beyond the narrow confines of Ise and the court. The integration of shrines in Buddhist-dominated complexes deepened, and the marginalization of the jingi cult continued.

—Pages 40-41

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

🌟 Step into a world of magic and wonder with our latest creation: the Anime Shrine wallpaper! 🎎✨ Immerse yourself in the enchanting atmosphere of this beautifully detailed onmyodo shrine, perfectly nestled within a lush, vibrant forest. 🌳💚

Each glowing orb around the shrine adds a touch of fantasy, inviting you to escape reality and dive into the mystical realms of anime. Whether you're a fan of serene landscapes or just love the captivating art of anime, this wallpaper is sure to bring a sense of peace and inspiration to your space. 🌌💫

Why not add a little magic to your desktop or mobile device? Check out the wallpaper and let it transport you to a world filled with adventure and imagination!

👉 Explore the Anime Shrine Wallpaper 👈

Perfect for anime lovers and anyone who appreciates a touch of fantasy in their life! Enjoy the beauty and let your creativity flow! 🎨💖

Stay tuned for more amazing wallpapers coming your way!

#anime#wallpaper#anime shrine#fantasy#onmyodo#mystical#forest#glowing orbs#digital art#anime art#nature#serene#adventure#imagination#lush greenery#artistic#aesthetic#escape#inspiration#creative

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

No MAO chapter today..

No Shonen Sunday this week, so no new chapter of MAO!However we'are longing for something exciting. So let's take looks on 2017's A Thousand Years of Innocence (千年の無心), which has many precursors to MAO.

This short story of Rumiko sama is one of action,school life,murder mystery and romance. No slpstick.He he he:)

Synopsis:

In modern Japan school girl Ai is harassed by her classmates,being scorned about a scar on her cheeks. Suddenly weird pieces of wood,with written spells on them, are about to kill all of them.But the immediate intervention of a strange young man saves them. And miraculously Ai's scar is wiped out,thanks to the man's blood.An adventure rife of mystery gets unfolded...

#Takahashi Rumiko#高橋 留美子#千年の無心#A Thousand Years of Innocence#MAO manga#school life#dark fantasy#onmyodo#Heian era#平安時代#Shogakukan manga#Weekly Shōnen Sunday#週刊少年サンデー#マオ#株式会社小学館#I Love Japan#日本が大好きです#愛

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Onmyodo at Philly Otaku Con

Really nice time running demos of Onmyodo at last month's Philly Otaku Con, a truly awesome convention right on the Philadelphia waterfront!

#onmyoji#yokai#japanese folklore#anime convention#gaming convention#philadelphia conventions#solo games#board game demos#onmyodo#shinto#cardgames

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Skeptical inquirer subscribers when they fail to calculate the current directional taboo and walk right into the presence of a supernatural being:

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Spirit of Onmyōdō

Alt Hao’s Spirit Ally

“Fractured Duality” (Alt Universe)

“The Spirit of Onmyōdō” was conjured specially for “Alt Hao” by the Shaman King so that he may fully utilise his Onmyōji mastery and skills within his new universe.

Its main oversoul form resembles Matamune’s “Oni-Slayer”, the oversoul form that “Alt Hao” is most familiar with from his memories. Its spirit medium is Oxygen.

It adopts a spiritual appearance resembling “The Spirit of Fire” for familiarity. Its primary oversoul colour is Yellow, another call back to “Alt Hao’s” memories of using an oversoul and Matamune as his Spirit Ally in his world. Though it can change its appearance and colour interchangeably depending on what Element it is using.

The colour Yellow is also a reference to the nature of “Alt Hao” being an “Alternative” character from a Canon-Divergence Universe (Shaman King, 2001).

Read more from the Post Ending “Alternative Universe” here.

Read “Fractured Duality” in full here.

#shaman king#hao asakura#my art#fractured duality#fan art#Asakura hao#Asakura twins#Yoh asakura#Asakura yoh#oversoul#Onmyodo#spirit of Onmyodo#shaman king fanfiction#fanfiction

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Well even though Onmyodo is Japanese it is based off the Chinese Philosophy of Yin and Yang and the Five Elements. Here is the reference.

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

術

122 notes

·

View notes

Text

This time of year the Seimei Jinja in Kyoto is selling these absolutely adorable cherry blossom patterned omori!

And I just can't help but imagine a scenario where Seishirou, pre identity reveal, buys one for Subaru! With Hokuto voicing her suspicions exacerbation with Seishirou dodging her questions as always. It would be so funny and so cute and also ever so slightly fucked up and sadistic of course 😂

PLEASE! Fic writers and fan artists need to get on this please!!!!!!

#tokyo babylon#clamp#CLAMP#bl manga#sakurazuka seishiro#sumeragi subaru#sumeragi hokuto#seisub#cherry blossom#onmyodo#shinto#abe no seimei#seimei shrine#japanese religion

1 note

·

View note

Note

Do you know why Abe-no-Seimei became so popular compared to any other onmyoji in folklore and literature? Is it because of who wrote his stories or something else?

There is no single clear answer. It seems safe to say there are multiple interconnected factors at play.

Seimei’s real career was genuinely extraordinary in some regards. To begin with, it was unusually long. He was around 85 years old when he passed away, and historical sources would indicate that he was still fairly active in old age (in fact, most references to him which are fully verifiable come from the second half of his life). Shin’ichi Shigeta actually argues here that Seimei's longevity in no small part contributed to cementing his legend.

However, it’s hard to argue that the times when Seimei lived were not a factor in its own right too. Institutional backing was no longer the sole reason behind the relevance of individual onmyōji. As I discussed in my recent article, by the middle of the tenth century their clientele expanded. And to find new clients, personal charisma was necessary. The shift started slightly earlier already but it doesn’t seem like the likes of Shigeoka no Kawahito or Kamo no Tadayuki left quite as much of an impression as Seimei and his contemporary Kamo no Yasunori in the long run. Legends do deal with earlier onmyōji at times, or rather reinvent earlier figures, especially Kibi no Makibi, as onmyōji, but this is often merely a way to make Seimei’s or Yasunori’s deeds appear even more amazing by making them a part of centuries old legacies (granted, standalone tales of Makibi appear for example in Konjaku Monogatari already).

Seimei’s personal influence is evident in the fact that he seemingly was responsible for popularizing formerly obscure Taizan Fukun no sai as one of the main onmyōdō rituals (check Shigeta’s article above for more specific evidence). Note that this was a performance so popular the early medieval reinterpretation of Amaterasu was in no small part driven by efforts to make her fit into rituals similar to it and Enmaten-ku. There’s also evidence that Seimei had an impact on the popularity of tsuina, a ceremony originally held only in the court but later also in private houses of nobles which served as a forerunner of modern setsubun.

The Abe clan remained influential in official onmyōdō circles long after Seimei’s death, and his heirs obviously invoked his fame to validate their own influence. There are texts only compiled after the Heian period which were attributed to him, such as Hoki Naiden. This obviously further contributed to the spread of his legend, making him relevant even as onmyōdō changed.

I don’t think it matters who wrote down the legends though, at least not before the Edo period. However, there are at least some individual elements which absolutely became such a mainstay of modern portrayals of Seimei because of the fame of specific authors who introduced and/or popularized them. A good example would be the Kuzunoha story, which was only invented in the 1600s and attained popularity because of Ryōi Asai’s Abe no Seimei Monogatari (I am not aware of any older legend claiming Seimei was not fully human, unless you want to count the Shuten Dōji variants presenting him as a manifestation of Kannon or Nagarjuna). Another thing which comes to mind as an example of influence of specific works of fiction is portraying Dōman as older than Seimei, which is a convention started by Edo period theatrical performances as far as I know. Dōman's historical counterpart was pretty obviously younger (granted, there's also no evidence he interacts with Seimei). He was still active three years after Seimei’s death, and there’s no indication he was somehow 90+ years old.

Bit of a digression but it’s worth noting Dōman isn’t Seimei’s only rival in the early stories, in Konjaku Monogatari he also faces a certain “fearsome fellow” named Chitoku who does seem to be older than him. He is an unlicensed onmyōji and comes from Harima, so it's easy to draw parallels with Dōman. However, they aren’t really similar characters; while Dōman is pretty firmly portrayed as a shady figure - a curse specialist first and foremost - Chitoku actually seems to utilize his skills to deal with pirates troubling his area. He just learns he’s a big fish in a small pond after unsuccessfully challenging Seimei. Still, I wonder if the two may have merged at some point in popular imagination.

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

A thought:

Mahoutokoro probably offers Onmyōdō as an elective.

0 notes

Text

Introduction

The Japanese Religious Blend Known as Shugendo

Though less widely known or practiced today than Buddhism or Shinto, shugendo was once a major force in Japan...Its practitioners, called shugenja, once provided the healing and spiritual services required by isolated communities. They also organized commercial markets and guided worshippers on pilgrimage...known more commonly as yamabushi (“one who lies down in the mountain”), were itinerant, usually unordained monks.

—Pages 24-25

Their struggle for enlightenment is embodied in their most important gods, Fudo Myō-o and Zao Gongen. Zao is a Japanese deity who first appeared on Mount Yoshino, where En no Gyoja was performing a thousand-day ascetic practice. The story recorded in a thirteenth-century work says that the Buddha appeared to him in turn as Shakyamuni, Kannon, and Maitreya. En no Gyoja rejected this, saying that the visage was too gentle for converting the evil world to Buddhism. So the god was transformed into the terrible figure of Zao with his arm raised in anger, his foot poised to strike the ground, his eyes ablaze, and flames shooting up around him.

—Page 25

Confucianism and Its Impact on Religion and Governance

...The greatest impact was on the ruling elite, who adopted its five tenets on the proper relationships between ruler and vassal; parent and child; husband and wife; elder and younger sibling; and friends...It includes a code of morality that emphasizes truthfulness, intelligence, sincerity, virtuousness, and obedience. The emphasis in Japan on ancestor worship, praying in front of an urn holding the ashes of the deceased, and the idea of heavenly and earthy kami are also influences of Confucianism.

—Pages 25-26

...In pre-medieval times it acted as a philosophical underpinning to kami worship, providing instruction on the proper way to live. Such considerations were lacking in kami worship—which was primarily oriented toward ritual for protecting the state and the emperor, protecting the crops from damage, and protecting the community from plagues and other forms of disaster. Though the Kojiki and Nihon shoki contain some limited moral allegory, there is nothing in the way of an ethical doctrine. Because Confucianism had few deities of its own, there was no obstacle to Shinto importing its precepts from the standpoint of belief in kami. Conversely, as a systematic and practical philosophy concerned with the reality of the world, Confucianism had little patience with religion... The anti-Buddhist bias found an ally in Shinto during the late Edo period.

—Page 26

The Japanese style of Divination Called Onmyodo

...In essence, onmyodo is Japanese divination based primarily on a combination of Chinese, five phase (or five-element) theory and yin/yang. The latter is a cosmology of balance between constantly cycling opposites, embodied in the familiar black and white symbol called the tai-ji...Five-phase theory is based on the “elements” of water, fire, wood, earth, and metal. The theory extended to every aspect of the physical world. For example, what was identified with birth, Jupiter, the east and so on. Knowledge of the proper use of materials, colors, or sounds could produce the correct alignment of forces and a positive outcome to any endeavor.

—Page 27

Shinto Today

...Shinto has no council of leaders deciding how doctrines should be interpreted or how they should be applied to present-day moral or political issues. There are no dictates about what one should or shouldn’t believe, but there are practices aimed at developing the right way to live, which can be described as developing purity of heart, brightness of character, thankfulness, and reverence for the kami. The positive or negative influence of the kami on daily life is considered the result of our reverence or neglect of them. Importance is placed on the correct ritual acts toward the kami and the correct attitude toward life. There are also accepted practices on the proper rate to venerate the gods in general and for venerating specific deities at specific locations. As far as the general public goes, such acts will usually involve the type of simple visitation and prayer described previously...

—Page 29

The Shinto Priesthood

Many Shinto priests serve only part time and many serve voluntarily. They are not cloistered, do not wear priestly garb outside of official duties and are free to marry. There are approximately twenty-two thousand licensed priests serving about eighty thousand shrines. This means that about two-thirds of all shrines are unmanned on a full-time basis. There are also certain rites traditionally performed by community members, most of which are related to festivals; however cleaning and daily offerings are also performed by them at unmanned shrines.

—Page 30

The daily schedule begins with cleaning the shrine grounds and buildings early in the morning. After that, a ceremony of the daily offering of food and drink for the kami is conducted, including reading of the Oharae no kotoba (purification prayer). First the area and the participants are purified in a ceremony called shubatsu. Offerings are placed on small tables within the haiden, on the steps in front of the honden, or some other designated place. They will usually consist of a rice wine called miki, rice, salt, and water. The food offering, called shinsen, is made once in the morning and possibly once in the evening, depending on the shrine. On special feast days mochi, fish, seaweed, vegetables, fruit, and confections may also be offered. The offerings are withdrawn in the evening and thanks given for divine protection.

—Pages 30-31

5 notes

·

View notes