#Odrysian Kingdom

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Guess what :]

#just talking recreationally#hetalia#Historical hetalia#Sort of#Hetalia ancients#Hetalia thrace#Aph thrace#Hws thrace#Odrysian kingdom#Aph#Hws#Thrace#The one multichapter fic I started is suffering I'm so sorry I wanna finish it but I would rather write anything else atm#Also#THE WORLD#<- my tag for my hetaverse stuff

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Unseen 3rd Century BC Thracian Temple Discovered by Archaeologists beneath ‘Large Mound’ in Bulgaria’s Plovdiv

The well-preserved ruins of the 3rd century BC Ancient Thracian temple discovered beneath a burial mound in Bulgaria’s Plovdiv. Photo by PodTepeto An Ancient Thracian temple from the 3rd century BC, of a type that has never been seen before, has been unearthed by archaeologists in Bulgaria’s Plovdiv, underneath a massive man-made hill known as “the Large Mound” (“Golyamata Mogila”). The Large…

#Ancient Thrace#Ancient Thracians#Bessi#burial mound#burial mounds#church#excavations#Hellenic#Large Mound (Golyamata Mogila)#Middle Ages#mortar#Odrysian Kingdom#Odrysians#pagan temple#Philipopolis#Plovdiv#Plovdiv Municipality#Plovdiv Museum of Archaeology#Pulpudeva#quadrae#Sapaeans#temple#Thracian temple#Thracians

0 notes

Note

Hi Dr Reames!

Would you say that Macedon shared the same "political culture" with its Thracian and Illyrian neighbours, like how most Greeks shared the polis structure and the concept of citizenship?

I don't really know anything about Macedonian history before Philip II's time, but you've often brought up how the Macedonians shared some elements of elite culture (e.g. mound burials) with their Thracian neighbours, as well religious beliefs and practices.

I've only ever heard these people generically described as "a collection of tribes (that confederated into a kingdom)", which also seems to be the common description for nearby "Greek" polities like Thessaly and Epiros. So did these societies have a lot in common, structurally speaking, with Macedon? Or were they just completely different types of polities altogether?

First, in the interest of some good bibliography on the Thracians:

Z. H. Archibald, The Odrysian Kingdom of Thrace. Orpheus Unmasked. Oxford UP, 1998. (Too expensive outside libraries, but highly recommended if you can get it by interlibrary loan. Part of the exorbitant cost [almost $400, but used for less] owes to images, as it’s archaeology heavy. Archibald is also an expert on trade and economy in north Greece and the Black Sea region, and has edited several collections on the topic.

Alexander Fol, Valeria Fol. Thracians. Coronet Books, 2005. Also expensive, if not as bad, and meant for the general public. Fol’s 1977 Thrace and the Thracians, with Ivan Marazov, was a classic. Fol and Marazov are fathers of modern Thracian studies.

R. F. Hodinott, The Thracians. Thames and Hudson, 1981. Somewhat dated now but has pictures and can be found used for a decent price if you search around. But, yeah…dated.

For Illyria, John Wilkes’ The Illyrians, Wiley-Blackwell, 1996, is a good place to start, but there’s even less about them in book form (or articles).

—————

Now, to the question.

BOTH the Thracians and Illyrians were made up of politically independent tribes bound by language and religion who, sometimes, also united behind a strong ruler (the Odrysians in Thrace for several generations, and Bardylis briefly in Illyria). One can probably make parallels to Germanic tribes, but it’s easier for me to point to American indigenous nations. The Odrysians might be compared to the Iroquois federation. The Illyrians to the Great Lakes people, united for a while behind Tecumseh, but not entirely, and disunified again after. These aren’t perfect, but you get the idea. For that matter, the Greeks themselves weren’t a nation, but a group of poleis bonded by language, culture, and religion. They fought as often as they cooperated. The Persian invasion forced cooperation, which then dissolved into the Peloponnesian War.

Beyond linguistic and religious parallels, sometimes we also have GEOGRAPHIC ones. So, let me divide the north into lowlands and highlands. It’s much more visible on the ground than from a map, but Epiros, Upper Macedonia, and Illyria are all more alike, landscape-wise, than Lower Macedonia and the Thracian valleys. South of all that, and different yet again, lay Thessaly, like a bridge between Southern Greece and these northern regions.

If language (and religion) are markers of shared culture, culture can also be shaped by ethnically distinct neighbors. Thracians and Macedonians weren’t ethnically related, yet certainly shared cultural features. Without falling into colonialist geographical/environmental determinism, geography does affect how early cultures develop because of what resources are available, difficulties of travel, weather, lay of the land itself, etc.

For instance, the Pindus Range, while not especially high, is rocky and made a formidable barrier to easy east-west travel. Until recently, sailing was always more efficient in Greece than travel by land (especially over mountain ranges).* Ergo, city-states/towns on the western coast tended to be western-facing for trade, and city-states/towns on the eastern side were, predictably, eastern-facing. This is why both Epiros and Ainai (Elimeia) did more trade with Corinth than Athens, and one reason Alexandros of Epiros went west to Italy while Alexander of Macedon looked east to Persia. It’s also why Corinth, Sparta, etc., in the Peloponnese colonized Sicily and S. Italy, while Athens, Euboia, etc., colonized the Asia Minor and Black Sea coasts. (It’s not an absolute, but one certainly sees trends.)

So, looking at their land, we can see why Macedonians and Thracians were both horse people with their wide valleys. They also practiced agriculture, had rich forests for logging, and significant metal (and mineral) deposits—including silver and gold—that made mining a source of wealth. They shared some burial customs but maintained acute differences. Both had lower status for women compared to Illyria/Epiros/Paionia. Yet that’s true only of some Thracian tribes, such as the Odrysians. Others had stronger roles for women. Thracians and Macedonians shared a few deities (The Rider/Zis, Dionysos/Zagreus, Bendis/Artemis/Earth Mother), although Macedonian religion maintained a Greek cast. We also shouldn’t underestimate the impact of Greek colonies along the Black Sea coast on inland Thrace, especially the Odrysians. Many an Athenian or Milesian (et al.) explorer/merchant/colonist married into the local Thracian elite.

Let’s look at burial customs, how they’re alike and different, for a concrete example of this shared regional culture.

First, while both Thracians and Macedonians had shrines, neither had temples on the Greek model until late, and then largely in Macedonia. Their money went into the ground with burials.

Temples represent a shit-ton of city/community money plowed into a building for public use/display. In southern Greece, they rise (pun intended) at the end of the Archaic Age as city-state sumptuary laws sought to eliminate personal display at funerals, weddings, etc. That never happened in Macedonia/much of the northern areas. So, temples were slow to creep up there until the Hellenistic period. Even then, gargantuan funerals and the Macedonian Tomb remained de rigueur for Macedonian elite. (The date of the arrival of the true Macedonian Tomb is debated, but I side with those who count it as a post-Alexander development.)

A “Macedonian Tomb” (above: Tomb of Judgement, photo mine) is a faux-shrine embedded in the ground. Elite families committed wealth to it in a huge potlatch to honor the dead. Earlier cyst tombs show the same proclivities, but without the accompanying shrine-like architecture. As early as 650 BCE at Archontiko (= ancient Pella), we find absurd amounts of wealth in burials (below: Archontiko burial goods, Pella Museum, photos mine). Same thing at Sindos, and Aigai, in roughly the same period. Also in a few places in Upper Macedonia, in the Archaic Age: Aiani, Achlada, Trebenište, etc.. This is just the tip of the iceberg. If Greece had more money for digs, I think we’d find additional sites.

Vivi Saripanidi has some great articles (conveniently in English) about these finds: “Constructing Necropoleis in the Archaic Period,” “Vases, Funerary Practices, and Political Power in the Macedonian Kingdom During the Classical Period Before the Rise of Philip II,” and “Constructing Continuities with a Heroic Past.” They’re long, but thorough. I recommend them.

What we observe here are “Princely Burials” across lingo-ethnic boundaries that reflect a larger, shared regional culture. But one big difference between elite tombs in Macedonia and Thrace is the presence of a BODY, and whether the tomb was new or repurposed.

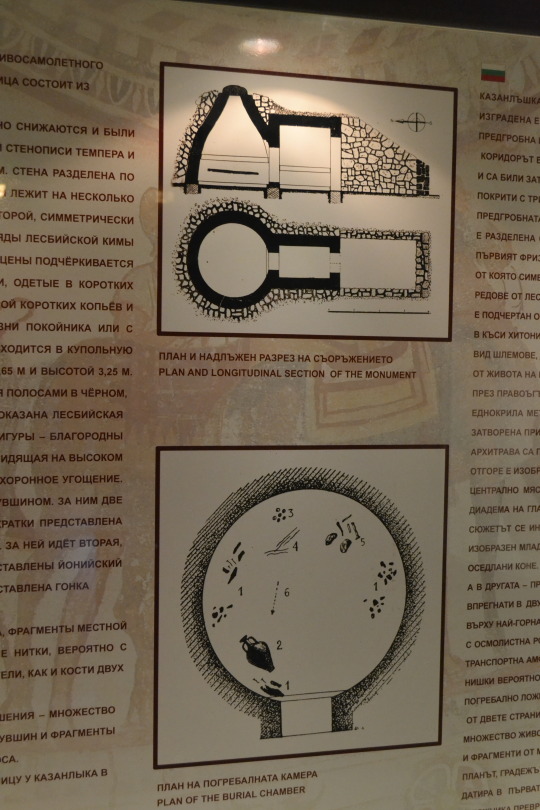

In Thrace, at least royal tombs are repurposed shrines (above: diagram and model of repurposed shrine-tombs). Macedonian Tombs were new construction meant to look like a shrine (faux-fronts, etc.). Also, Thracian kings’ bodies weren’t buried in their "tombs." Following the Dionysic/ Orphaic cult, the bodies were cut up into seven pieces and buried in unmarked spots. Ergo, their tombs are cenotaphs (below: Kosmatka Tomb/Tomb of Seuthes III, photos mine).

What they shared was putting absurd amounts of wealth into the ground in the way of grave goods, including some common/shared items such as armor, golden crowns, jewelry for women, etc. All this in place of community-reflective temples, as seen in the South. (Below: grave goods from Seuthes’ Tomb; grave goods from Royal Tomb II at Vergina, for comparison).

So, if some things are shared, others (connected to beliefs about the afterlife) are distinct, such as the repurposed shrine vs. new construction built like a shine, and the presence or absence of a body (below: tomb ceiling décor depicting Thracian deity Zalmoxis).

Aside from graves, we also find differences between highlands and lowlands in the roles of at least elite women. The highlands were tough areas to live, where herding (and raiding) dominated, and what agriculture there was required “all hands on deck” for survival. While that isn’t necessary for women to enjoy higher status (just look at Minoan Crete, Etruria, and even Egypt), it may have contributed to it in these circumstances.

Illyrian women fought. And not just with bows on horseback as Scythian women did. If we can believe Polyaenus, Philip’s daughter Kyanne (daughter of his Illyrian wife Audata) opposed an Illyrian queen on foot with spears—and won. Philip’s mother Eurydike involved herself in politics to keep her sons alive, but perhaps also as a result of cultural assumption: her mother was royal Lynkestian but her father was (perhaps) Illyrian. Epirote Olympias came to Pella expecting a certain amount of political influence that she, apparently, wasn’t given until Philip died. Alexander later observed that his mother had wisely traded places with Kleopatra, his sister, to rule in Epiros, because the Macedonians would never accept rule by a woman (implying the Epirotes would).

I’ve noted before that the political structure in northern Greece was more of a continuum: Thessaly had an oligarchic tetrarchy of four main clans, expunged by Jason in favor of tyranny, then restored by Philip. Epiros was ruled by a council who chose the “king” from the Aiakid clan until Alexandros I, Olympias’s brother, established a real monarchy. Last, we have Macedon, a true monarchy (apparently) from the beginning, but also centered on a clan (Argeads), with agreement/support from the elite Hetairoi class of kingmakers. Upper Macedonian cantons (formerly kingdoms) had similar clan rule, especially Lynkestis, Elimeia, and Orestis. Alas, we don’t know enough to say how absolute their monarchies were before Philip II absorbed them as new Macedonian districts, demoting their basileis (kings/princes) to mere governors.

I think continued highland resistance to that absorption is too often overlooked/minimized in modern histories of Philip’s reign, excepting a few like Ed Anson’s. In Dancing with the Lion: Rise, I touch on the possibility of highland rebellion bubbling up late in Philip’s reign but can’t say more without spoilers for the novel.

In antiquity, Thessaly was always considered Greek, as was (mostly) Epiros. But Macedonia’s Greek bona-fides were not universally accepted, resulting in the tale of Alexandros I’s entry into the Olympics—almost surely a fiction with no historical basis, fed to Herodotos after the Persian Wars. The tale’s goal, however, was to establish the Greekness of the ruling family, not of the Macedonian people, who were still considered barbaroi into the late Classical period. Recent linguistic studies suggest they did, indeed, speak a form of northern Greek, but the fact they were regarded as barbaroi in the ancient world is, I think instructive, even if not necessarily accurate.

It tells us they were different enough to be counted “not Greek” by some southern Greek poleis and politicians such as Demosthenes. Much of that was certainly opportunistic. But not all. The bias suggests Macedonian culture had enough overflow from their northern neighbors to appear sufficiently alien. Few Greek writers suggested the Thessalians or Epirotes weren’t Greek, but nobody argued the Thracians, Paiones, or Illyrians were. Macedonia occupied a liminal status.

We need to stop seeing these areas with hard borders and, instead, recognize permeable boundaries with the expected cultural overflow: out and in. Contra a lot of messaging in the late 1800s and early/mid-1900s, lifted from ancient narratives (and still visible today in ultra-national Greek narratives), the ancient Greeks did not go out to “civilize” their Eastern “Oriental” (and northern barbaroi) neighbors, exporting True Culture and Philosophy. (For more on these views, see my earlier post on “Alexander suffering from Conqueror’s Disease.”)

In fact, Greeks of the Late Iron Age (LIA)/Archaic Age absorbed a great deal of culture and ideas from those very “Oriental barbarians,” such as Lydia and Assyria. In art history, the LIA/Early Archaic Era is referred to as the “Orientalizing Period,” but it’s not just art. Take Greek medicine. It’s essentially Mesopotamian medicine with their religion buffed off. Greek philosophy developed on the islands along the Asia Minor coast, where Greeks regularly interacted with Lydians, Phoenicians, and eventually Persians; and also in Sicily and Southern Italy, where they were talking to Carthaginians and native Italic peoples, including Etruscans. Egypt also had an influence.

Philosophy and other cultural advances didn’t develop in the Greek heartland. The Greek COLONIES were the happenin’ places in the LIA/Archaic Era. Here we find the all-important ebb and flow of ideas with non-Greek peoples.

Artistic styles, foodstuffs, technology, even ideas and myths…all were shared (intentionally or not) via TRADE—especially at important emporia. Among the most significant of these LIA emporia was Methone, a Greek foundation on the Macedonian coast off the Thermaic Gulf (see map below). It provided contact between Phoenician/Euboian-Greek traders and the inland peoples, including what would have been the early Macedonian kingdom. Perhaps it was those very trade contacts that helped the Argeads expand their rule in the lowlands at the expense of Bottiaians, Almopes, Paionians, et al., who they ran out in order to subsume their lands.

My main point is that the northern Greek mainland/southern Balkans were neither isolated nor culturally stunted. Not when you look at all that gold and other fine craftwork coming out of the ground in Archaic burials in the region. We’ve simply got to rethink prior notions of “primitive” peoples and cultures up there—notions based on southern Greek narratives that were both political and culturally hidebound, but that have, for too long, been taken as gospel truth.

Ancient Macedon did not “rise” with Philip II and Alexander the Great. If anything, the 40 years between the murder of Archelaos (399) and the start of Philip’s reign (359/8) represents a 2-3 generation eclipse. Alexandros I, Perdikkas II, and Archelaos were extremely capable kings. Philip represented a return to that savvy rule.

(If you can read German, let me highly recommend Sabine Müller’s, Perdikkas II and Die Argeaden; she also has one on Alexander, but those two talk about earlier periods, and especially her take on Perdikkas shows how clever he was. For those who can’t read German, the Lexicon of Argead Macedonia’s entry on Perdikkas is a boiled-down summary, by Sabine, of the main points in her book.)

Anyway…I got away a bit from Thracian-Macedonian cultural parallels, but I needed to mount my soapbox about the cultural vitality of pre-Philip Macedonia, some of which came from Greek cultural imports, but also from Thrace, Illyria, etc.

Ancient Macedonia was a crossroads. It would continue to be so into Roman imperial, Byzantine, and later periods with the arrival of subsequent populations (Gauls, Romans, Slavs, etc.) into the region.

That fruit salad with Cool Whip, or Jello and marshmallows, or chopped up veggies and mayo, that populate many a family reunion or church potluck spread? One name for it is a “Macedonian Salad”—but not because it’s from Macedonia. It’s called that because it’s made up of many [very different] things. Also, because French macedoine means cut-up vegetables, but the reference to Macedonia as a cultural mishmash is embedded in that.

---------------

* I’ve seen this personally between my first trip to Greece in 1997, and the new modern highway. Instead of winding around mountains, the A2 just blasts through them with tunnels. The A1 (from Thessaloniki to Athens) was there in ’97, and parts of the A2 east, but the new highway west through the Pindus makes a huge difference. It takes less than half the time now to drive from the area around Thessaloniki/Pella out to Ioannina (near ancient Dodona) in Epiros. Having seen the landscape, I can imagine the difficulties of such a trip in antiquity with unpaved roads (albeit perhaps at least graded). Taking carts over those hills would be daunting. See images below.

#asks#ancient Macedonia#ancient Thrace#ancient Epiros#ancient Thessaly#Argead Macedonia#pre-Philip Macedonia#Late Iron Age Greece#Archaic Age Greece#Thracian tombs#Macedonian tombs#Classics#tagamemnon#Alexander the Great#Philip II of Macedon#Philip of Macedon#women in ancient Macedonia#ancient Illyria#women in Illyria#Macedonian-Thracian similarities#religion in ancient Thrace#religion in ancient Macedonia

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

North Macedonia is a fairly new, relatively small landlocked country. The Macedonian nation is anything but.

North Macedonia became independent in 1991 following the break-up of Yugoslavia. North Macedonia has been a member of the UN since 1993, but the Greeks objected to the original name "Macedonia", as there is a Greek region of the same name. They were admitted under the provisional description "the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia" in 2018 the dispute was resolved with an agreement that the country should rename itself "Republic of North Macedonia" which came into effect in early 2019.

This is not the end of that particular story though. A few days ago at the Presidential inauguration, new President Gordana Siljanovska-Davkova called the country "Macedonia" - the Greek ambassador walked out of the inauguration. https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/c3g5rj4y24do

The wider region of Macedonia is spread, mainly, across three countries - North Macedonia, known as Vardar Macedonia, Greece, known as Aegean Macedonia and Bulgarian, known as Pirin Macedonia. There are also parts of the Macedonia region in Albania, Kosovo and Serbia.

Settlements date back to around 7,000 BC. The Kingdom of Macedonia became the dominant power in the Balkans from the middle of the 4th century and peaked under Philip II and Alexander the Great.

Under Philip II Macedonia subdued mainland Greece and the Thracian Odrysian kingdom through conquest and diplomacy. Philip II defeated Athens and Thebes in the Battle of Chaeronea in 338 BC.

Alexander the Great conquered the remainder of Greece when he destroyed Thebes and grew the Empire to reach India in the east and Egypt in the south/west.

After Alexander’s death things began to fall apart and between 168 BC and 148 BC the Romans had taken over most, if not all, of Macedonia.

With the division of the Roman Empire into west and east in 298 AD, Macedonia came under the rule of Rome's Byzantine successors. Over time great parts of Macedonia came to be controlled by Slavic-speaking communities known as Sklaviniai.

After 836/837 the region was absorbed into the First Bulgarian Empire. The first Slavic Glagolitic alphabet was created in the early 860s in the cultural, and ecclesiastical, centre of Ohrid.

In 1018 Macedonia was reincorporated into the Byzantine Empire as the province of Bulgaria. At the end of the 12th century, some northern parts of Macedonia were temporarily conquered by Serbia.

In the 13th century, following the Fourth Crusade, Macedonia was disputed among Byzantine Greeks, the Kingdom of Thessalonica, and the Bulgaria. After 1261 all of Macedonia was once again returned to Byzantine rule, where it largely remained until the Byzantine civil war of 1341–1347, when it once again came under the control of the Serbia Empire.

After the Ottoman victory in the Battle of Maritsa in 1371, most of Macedonia was again under their rule and by the end of the 14th century the Ottoman Empire gradually annexed the region. Macedonia remained part of the Ottoman Empire for most of the next 500 years.

By the late 1890s rival groups were trying to assert themselves across Macedonia. In 1903 the Ilinden-Preobrazhenie Uprising in 1903 calling for an independent Macedonian state, and the Greek struggle for Macedonia from 1904 until 1908 led to diplomatic intervention by the European powers and plans for an autonomous Macedonia under Ottoman rule.

What happened, however, were the Balkan Wars. In the First Balkan War (1912-1913), Bulgaria, Serbia, Greece and Montenegro occupied almost all Ottoman-held territories in Europe. The Ottoman Empire in the Treaty of London in May 1913 assigned the whole of Macedonia to the Balkan League, without, specifying the division of the region. The Second Balkan War (1913) saw Bulgarian troops to attack the Greek and Serbian troops in Macedonia, the war sucked in various other powers and the Ottomans even regained some of their lost territory. Most of Macedonia ended up under Greek control.

The ‘settlement’ at the end of the First World War confirmed most Macedonia as under Greek control. Serbian-ruled Macedonia was incorporated into the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes, which later became Yugoslavia.

During the Second World War the boundaries of the region shifted yet again. When the German forces occupied the area, most of Yugoslav Macedonia and part of Aegean Macedonia were transferred for administration to Bulgaria. The western Aegean Macedonia was occupied by Italy, with the western parts of Yugoslav Macedonia being annexed to Italian-occupied Albania.

Macedonia was liberated in 1944, when the Red Army's advance in the Balkan Peninsula forced the German forces to retreat. The pre-war borders were restored under U.S. and British pressure. What is now North Macedonia became the People's Republic of Macedonia as part of the People's Federal Republic of Yugoslavia.

In 1991 following a referendum the People’s Republic of Macedonia became independent of Yugoslavia. (North) Macedonia remained at peace through the Yugoslav Wars of the early 1990s although there were agreed changes to the border.

North Macedonia is a candidate country for EU enlargement, but the recent comments from the new President have led to Greece saying they may veto any accession agreement.

0 notes

Text

Golden mask of Teres I, the first ruler of the Odrysian kingdom.

0 notes

Text

Odrysian Veterans. In most parts of the ancient world, older men were not expected to participate in military active duty; most men over their 40s opted for civic and political life instead. In the Odrysian Kingdom there was an entire Veteran Class of Soldiers comprised of old men who would train together, go on scouting parties and be the first response to enemies at the border. These were the Odrysian Veterans; a heavy infantry unit knowledgeable in geography and survival within the Balkan wilderness. The Odrysian Kingdom was a united Thracian tribal confederasy of 40 tribes spanning across modern day, Bulgaria, Turkey, Romania, and Greece.

#odrysian kingdom#odrysian#thracians#dacians#illyrian#triballi#romania#bulgaria#serbia#greece#macedonia#pagan#paganism#turkey#paleo balkan paganism#albania#celtic paganism#norse paganism#slavic paganism#europe#traditionalism#pagan goddesses#pagan gods#balkan#balkan culture#balkan tradition#balkan history

50 notes

·

View notes

Text

Read and Review - Thrace, control and social complexity

Time for something a little bit different. Read and Review - Thrace, control and social complexity #ancienthistory #archaeology #Thrace #Review

Letnitsa treasure | from Wikimedia Commons | CC BY-SA 3.0

Having nearly completed my Egyptian Module, I have discovered I really enjoy the ‘Read and Review’ format. So, as part of my mini-dissertation provisionally entitled, ‘How did the Odrysian Kingdom use its physical and cultural geography to maintain control of its subjects during the reigns of Sitalkes and Seuthes (431-407)?’, I had to…

View On WordPress

1 note

·

View note

Text

History of the Balkans 9th Century BC - 4th Century BC

IRON AGE

During the Iron Age, Greek culture expanded across the Balkans. This involved developing an efficient trade route through the Balkans, converting citizens to a faith based on ancient Greek ideology, and the use of refined tools. At this time, artwork, religious shrines, sculptures, and fine architecture proliferated. However, the adopted lifestyle of the Balkan people would not end peacefully.

In the 6th Century BC, the Greco-Persian wars lead to the invasion of the Persians. Fortunately, the Greeks were victorious and Persian control over the Balkans was relinquished. Under Greek control, the Thracian Odrysian empire formed and flourished.

PRE-ROMAN STATES

Illyria became a kingdom of great power and control during the 4th century BC, but would later be conquered by Philip II of Macedon. His successor, Alexander the Great, would maintain peace until his death. Following his passing, however, individual states often engaged in war. It was during one of these wars that Illyrian vessels attacked a Roman ship, providing Rome with a reason to invade the Balkans.

Rome would successfully conquer many of the states, establishing complete control. The Balkans would be divided into three separate territories known as Macedonia, Achaia, and Epirus.

0 notes

Link

“YAMBOL, BULGARIA—Archaeology in Bulgaria reports that an intact Roman-era inscription has been uncovered in the ancient Thracian city of Kabyle, which is located in southeastern Bulgaria. The city was home to rulers of the Odrysian Thracian kingdom from the fifth century B.C. until the first century A.D., when it was conquered by the Romans. The seven lines of Latin text, engraved on a two-foot-tall stone slab, are said to date to the reign of Marcus Aurelius, who ruled from A.D. 161 to 180, and refer to the construction of the city’s public baths, or thermae. The stone was found near the command center for the local military unit, which had built the thermae. “All in all, the inscription’s translation reveals that the thermae in Kable were built by the Cohors II Lucensium at the time when the Thracia province was governed by Governor Claudius Marcialus,” Stefan Bakardzhiev, director of the Regional Museum of History in Yambol, explained. To read about another recent Roman-era discovery in Bulgaria, go to "Mirror, Mirror."

#classics#tagamemnon#tagitus#history#ancient history#bulgaria#roman era inscription#roman empire#empire#roman history#ancient roman history#rome#ancient rome#roman europe#latin#latin text#imperialism#marcus aurelius#thermae#kable#cohors ii lucensium#thracia#claudius marcialus#yambol#archaeology#archaeology magazine

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Some of my OCs!!!! (Don't think too much about the clothing, it's just there and probs not historically accurate).

Wanted to draw how they look like in my head, Dacia & Thrace & the Getae. I'll probably change some stuff later idk not truly happy with how they look

Also this is Thrace but at a time when he was younger since I think when he grows into an adult he probs grows a beard

(Notes under the cut)

they're...siblings in the weird nation way.

Thrace's hair probably darkens even more as he grows up since I see him as having darker hair as an adult dbdhhddj

The Getae & Dacia might have been the same, or might have been very strongly related but I chose the make 2 OCs for them

(And I don't really have OCs for them yet, but I do think all the tribes that made up the dacians & the thracians also had personifications)

Dacia's slight resemblance to Romania was intended haha

Might change Thrace's eye colour idk

dacia would have probably worse some kind of head scarf or had her hair tied up but I wanted to draw her with her hair down

Idk can't think of anything else to say atm

#just talking recreationally#hetalia#Dacia#Thrace#Odrysian kingdom#Getae#Aph#Hws#Hws dacia#Hws thrace#Hws getae#Ancientalia#Hetalia ancients

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Celebrated ‘Armor of Thracian Warriors’ Exhibition to Be Showcased at Valley of Odrysian Kings

Part of a poster for the “Panoply of the Thracian Warriors” exhibition developed by Bulgaria’s National institute and Museum of Archaeology in Sofia А poster presentation of the celebrated exhibition entitled “The Panoply of the Thracian Warriors,” a project of Bulgaria’s National Institute and Museum of Archaeology, is set to be showcased in Kazanlak as part of the annual Celebrations at the…

#Agighiol tomb#armor#Bulgarian Academy of Sciences#burial mound#burial mounds#corslet#exhibition#Golyama Kosmatka Mound#Golyama Kosmatka Tomb#greave#greaves#helmet#Kazanlak#Kazanlak Museum of History#Kazanlak Valley#King Seuthes III#mask helmet#Mezek Tomb#Mogilanska Mound Treasure#National Institute and Museum of Archaeology#Odrysian Kingdom#Odrysians#poster exhibition#Romania#Ruets#Ruets tomb#Seuthes III#sheath#Sofia University "St. Kliment Ohridski"#Svetitsata (The Saint) Mound

0 notes

Note

Hi again Dr Reames! Thank you so much for your explainer on Macedon's relationship with neighbouring Balkan cultures last time. So, another question on cross-cultural ties:

Do we know if the period of Persian hegemony over the region left any impact on how the Macedonian state was run?

Obviously, the Argeads got to keep their jobs, and my impression is that the Achaemenids rarely intervened in the internal governance of their satraps (outside of wartime levies and big projects like the royal roads). But I also read in Maria Brosius' A History of Ancient Persia that the neighbouring Odrysian Kingdom deliberately modelled its court after the Achaemenid one, and that the Greeks adopted a lot of Persian apparels and everyday items over centuries of cross-Aegean relations.

So did the Persians leave any lasting influence on the Macedonian bureaucracy, court culture, etc.? (Brosius also mentions the Persians identifying the Thracian Getai as a sub-set of Scythians, which had me wondering about the extent of cultural exchanges between Iranian steppe peoples and other cultures of the southern Balkans/west-of-Black Sea region in this period).

Thank you once again for your time!

The answer is, we think, quite a lot—but exactly what is less clear. Like the Odrysians, the Macedonians seem to have borrowed a fair number of court structural ideas. Alexander I also took advantage of Persian assistance to secure his hold on much of the northern area, expanding Macedon and seizing silver mines, through which he enriched his own coinage.

In In the Shadow of Olympus, Gene Borza has a good chapter on Alexander I. Some things are a bit dated now due to recent archaeological discoveries, but the basics are the same. I recommend reading that (the whole book, in fact). Vivi Sarapanidi also has several good articles in English on the significance of archaeological discoveries up there—and separates some of those cultural trends from Persian influence. I’m deeply interested in Late Iron Age/Archaic Age developments in the north, what Macedon borrowed and what it didn’t. A sense of sumptuous royal style is something they shared regionally, not something they got from Persia.

What Macedon did borrow seems to be new offices and ideas for running a court more effectively. So, creating a Royal Bodyguard (Somatophylakes) as well as a special fighting force around the king as a “bodyguard” in combat may both be Persian adoptions, although the reason for “7” Somatophylakes is unclear. Perhaps it reflects the seven princes of Fars who had special status with the Great King at court, but I find it unlikely that Alexander I would adopt a number based on Persian elite. More likely, it reflects the number of high-status clans (Hetairoi) in Macedon at that time; one Somatophylax from each family/clan?

Also, a “combat bodyguard” is something we see in many kingdoms, not just Persia, so that may not be Persian after all. But certainly the Great King from Darius, and possibly Cyrus, forward had the Apple Bearers (Melephoroi) to guard him in battle.

Like Macedon, Persia evolved across time, and our paucity of surviving records, as well as the tendency for Greek writers to project traditions backwards, makes it tough to know when any given element entered into Persian practice.

Another office that may owe to Persia are the King’s Boys (Paides Basilikoi), also called Royal Pages. As with the Somatophylakes, we don’t know when they were instituted. Circumstantial evidence suggests Archelaos, at least, may have had them, but the account of his “accidental” spearing during a royal hunt doesn’t call the boys assisting “King’s Boys.” Their ages aren’t clear; they’re just “youths.” So probably Pages, but unclear.

Finally, offices such as Royal Secretary may owe to Persian example. Yet again, such an office would be a logical extension of increased correspondence. Did the Macedonian court borrow it, or simply decide they needed one due to circumstance?

So, yes—the general assumption is that Macedon borrowed ideas from the Persians, perhaps even a lot of ideas, but pin-pointing what can be tricky. While we don’t want to deny Persian influence, by the same token, we don’t want to assume “Persians” for traditions that may be indigenous, or at least a regional shared culture.

#asks#Achaemenid Persia#ancient Persia#ancient Macedon#ancient Macedonia#Alexander I of Macedon#Classics#Iron-Age Greece#Archaic Era Greece#Archaic Era Macedonia#Persian influence on ancient Macedonia#tagamemnon

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Daily Tulip

The Daily Tulip – Friday’s Archeological News From Around The World

Friday 13th July 2018

Good Morning Gentle Reader…. Well Archeologists have been really busy this week, telling us all about their discoveries made over the last year or so, as most of you understand, it takes quite a while to go from finding to announcing the find to the public, in many cases years and years, but eventually we get to hear all about it and then I can “Discover” it and post it here for all of us to learn, so from Dogs to Gold Coins and a mixture of everything in-between …

GENES OF NORTH AMERICA’S FIRST DOGS STUDIED…. OXFORD, ENGLAND—The mitochondrial DNA of ancient North American dogs has not been found in any other canines, according to a report in Science Magazine. A genetic study of dogs who lived in North America and Siberia between 1,000 and 10,000 years ago found that the genetic signature of the ancient American dogs most closely resembles that of 9,000-year-old dogs from Russia’s Zhokhov Island, which lies north of the Siberian mainland. A study of dogs’ nuclear DNA also supports the idea that ancient North American dogs were genetically distinct from today’s animals, but related to Arctic breeds like Alaskan malamutes and Siberian huskies. Evolutionary geneticist Laurent Frantz of the University of Oxford suggests the rate of genetic mutation indicates ancient North American dogs and ancient Siberian dogs shared an ancestor some 16,000 years ago, or about the time when humans were migrating into North America. Dogs may have traveled to the New World with humans, or they may have crossed the land bridge from Siberia into North America on their own at a later date, but before the land bridge disappeared some 11,000 years ago. Zooarchaeologist Angela Perri of Durham University said the first North American dogs were likely wiped out by diseases brought to the New World by the dogs of European explorers, or may have been killed off by wary Europeans who were frightened by their wolf-like appearance.

LARGE HOUSES FOUND NEAR EGYPT’S GIZA PYRAMIDS…. GIZA, EGYPT—Live Science reports that the remains of two 4,500-year-old structures have been uncovered at an ancient port near the Giza pyramids by a team of researchers led by Mark Lehner of Ancient Egypt Research Associates. The buildings are thought to have served as housing for a priest who may have been a high-ranking government official and an official in charge of the production of food for a paramilitary force during the reign of Menkaure, who ruled from about 2490 to 2472 B.C. A third large building at the site may have been used for brewing and baking. Nearby buildings called galleries may have housed the paramilitary force, thought to have been made up of about 1,000 people. The food produced at the site could have fed the people living in the galleries, and perhaps even some of the workers building Menkaure’s pyramid.

ROMAN INSCRIPTION UNEARTHED IN THRACIAN CITY…. YAMBOL, BULGARIA—Archaeology in Bulgaria reports that an intact Roman-era inscription has been uncovered in the ancient Thracian city of Kabyle, which is located in southeastern Bulgaria. The city was home to rulers of the Odrysian Thracian kingdom from the fifth century B.C. until the first century A.D., when it was conquered by the Romans. The seven lines of Latin text, engraved on a two-foot-tall stone slab, are said to date to the reign of Marcus Aurelius, who ruled from A.D. 161 to 180, and refer to the construction of the city’s public baths, or thermae. The stone was found near the command center for the local military unit, which had built the thermae. “All in all, the inscription’s translation reveals that the thermae in Kable were built by the Cohors II Lucensium at the time when the Thracia province was governed by Governor Claudius Marcialus,” Stefan Bakardzhiev, director of the Regional Museum of History in Yambol, explained.

INCA BURIALS FOUND IN LAMBAYEQUE PYRAMID OF THE BEES…. TÚCUME, PERU—According to a Reuters report in the New York Times, two dozen burials dating to the time of the Inca Empire have been found in the Pyramid of the Bees at the Lambayeque site of Tucume, which is located in a desert valley near Peru’s northern coastline. Archaeologist Jose Manuel Escudero said the space had been reused by the Inca, but there is no evidence at this time that they took it over by force. The cave-like tombs within the adobe pyramid contain human remains and pottery. The remains of men holding spiked spondylus shells were found in five of the tombs. One of the bodies in another tomb had been wrapped in more than four shrouds and set on a bed of ceramic pieces. One of these shrouds had been quilted. “You’re not going to bury an ordinary person that way,” Escudero said. He thinks burial in the Pyramid of the Bees may have held “great significance for them to be buried there.”

"LUCY'S BABY" HAD GRASPING BIG TOES…. HANOVER, NEW HAMPSHIRE—According to a Live Science report, a study of DIK-1-1, the remains of a three-year-old Australopithecus afarensis individual discovered in Dikika, Ethiopia, suggests that she had a grasping big toe that probably helped her hold onto her mother and even climb trees some 3.3 million years ago. Paleoanthropologist Jeremy DeSilva of Dartmouth College and his colleagues said the toddler’s two-inch long foot resembles the feet of modern humans, except for the curved big toe. “So, it’s human-like in not sticking out to the side, but it had much more mobility and could probably wiggle and grab on to stuff,” DeSilva said. “Not [as well as] a chimp, but certainly more than a human could.” And, adult A. afarensis fossils, such as Lucy, have robust heel bones similar to those possessed by modern humans for upright walking. Selam, however, has a small, delicate heel, which suggests she may have spent more time aloft than her parents, perhaps to avoid large predators.

MONGOLIA’S EARLIEST EVIDENCE OF EQUINE DENTISTRY…. JENA, GERMANY—Live Science reports that researchers led by William Taylor of the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History examined the remains of 85 horses buried between 1200 and 700 B.C. in Mongolia by the nomadic Deer Stone–Khirigsuur culture and found evidence of early equine dental care. In the skull of one of the horses, dated to 1150 B.C., a tooth sticking out at an odd angle bears a cut mark that suggests someone may have used a stone to form it into a shape that would be more comfortable for the horse. The researchers also discovered that after 750 B.C., when the herders of the Deer Stone–Khirigsuur culture began using metal bits in horses’ mouths instead of ones made of wood, rope, or leather, some horses required additional dental care, to remove remove a functionless premolar known as a wolf tooth, which can interfere with wearing a metal bit. “It’s really shocking and cool that [wolf-tooth removal] directly accompanied the introduction of metal bits,” Taylor said.

BRONZE COINS RECOVERED IN 2,300-YEAR-OLD TOMB…. ROME, ITALY—A cache of coins dating to the third century B.C. has been found at the Poggetto Mengarelli necropolis at the Vulci archaeological site, located near the coast of the Tyrrhenian Sea, according to a report in ANSA. The 15 large bronze coins bear images of the god Janus Bifrons on one side and the prow of a boat on the other, representing the passage to the underworld from the world of the living. They are thought to have been stored in a leather bag, and then placed in the burial along with ceramics and an iron tool called a strigil that was used to clean the body. A coin similar to those in the bag was placed near a bronze clasp on the left shoulder of a man who was buried in the tomb. An iron object that may have been a spear was found near his head. The second person buried in the tomb had been cremated, and the remains wrapped in a shroud that had probably been closed with the bronze clasp found nearby. A small circular pyx, or chalice, with a lead cover was discovered in the tomb’s vestibule.

Well Gentle Reader I hope you enjoyed our look at the news from around the world this, morning… …

Our Tulips today come with a cup of coffee for you to enjoy while you read…..

A Sincere Thank You for your company and Thank You for your likes and comments I love them and always try to reply, so please keep them coming, it's always good fun, As is my custom, I will go and get myself another mug of "Colombian" Coffee and wish you a safe Friday 13th July 2018 from my home on the southern coast of Spain, where the blue waters of the Alboran Sea washes the coast of Africa and Europe and the smell of the night blooming Jasmine and Honeysuckle fills the air…and a crazy old guy and his dog Bella go out for a walk at 4:00 am…on the streets of Estepona…

All good stuff....But remember it’s a dangerous world we live in

Be safe out there…

Robert McAngus #Travel #Archeology #News #Blog #Love #Gold #History

1 note

·

View note

Photo

THE THRACIANS AT THE TIME OF KING SITALCES (431–424 BCE)

This is an excerpt from my post, ‘THRACIANS, REAPERS OF THE BALKANS’

Sitalces and the Scythians:

Teres’ son and heir, Sitalces, expanded its borders north to the Danube River, west to the Strymon River (Struma) and southwest to the rich Greek trade port colony of Abdera by the northern Aegean Sea. The Greek colonies within the borders of his kingdom paid the Odrysians tribute as well as the occasional gifts of “gold and silver equal in value to the tribute, besides stuffs embroidered or plain and other articles” (Thucydides, 97.3).

“By these means the kingdom became very powerful, and in revenue and general prosperity exceeded all the nations of Europe which lie between the Ionian Sea and the Euxine; in the size and strength of their army being second only, though far inferior, to the Scythians.” – The Peloponnesian War by Thucydides, 97.5.

An early threat faced by Sitalces came in the form of a nephew named Octamasades who was of mixed Thracian and Scythian descent. This Octamasades usurped the Scythian throne from Scyles, his half-brother, who was disliked for the fact that he was half Greek, could read and speak Greek, married a Greek woman, built a house in the Greek trade colony of Olbia (north Black Sea coast), as well as publicly practicing the Greek Dionysian sacred rites. Scyles fled into Thrace seeking refuge. Octamasades chased after him but was met at the Danube River by Sitalces of Odrysia who sent Octamasades a message:

“Why should we try each other’s strength? You are my sister’s son, and you have my brother with you; give him back to me, and I will give up your Scyles to you; and let us not endanger our armies.” – The Histories by Herodotus, 4.80.3. Both sides agreed and Octamasades beheaded Scylas.

Peloponnesian War (431–404 BCE):

The Athenian-led Delian League succeeded in expelling the Persians from Europe and claimed the coastal regions of the northern Aegean Sea (the Hellespont, Thrace, Amphipolis and the Chalkidikian Peninsula) where they continued establishing colonies. Colonies were even founded deeper into Thrace, Amphipolis for example. One reason for their interest in Thrace was its rich and abundant gold and silver mines. With the Greek triumph over Persia, the Athenians and their allies effectively held dominion over the majority of the Aegean Sea, its coastlines and its islands. We refer to this grand Athenian hegemony as the Athenian Empire.

^ The expanse of the Athenian-led Delian League in 431 BCE, before the Peloponnesian War.

The Athenian empire was now tyrannically imposing their control over allied Greek city states and the rich trade networks of the Aegean Sea but was plagued by rebellions. Sitalces allied himself with the Athenians, promising them aid in Thrace if they helped him conquer the Chalkidikian peninsula (which had recently left the Athenian-led Delian League) which was to the east of Macedon. To this end Sitalces assembled an army of “more than one hundred and twenty thousand infantry and fifty thousand cavalry” (Diodorus, 12.50.3).

“many of the independent Thracian tribes followed him of their own accord in hopes of plunder. The whole number of his forces was estimated at a hundred and fifty thousand, of which about two-thirds were infantry and the rest cavalry.” – The Peloponnesian War by Thucydides, 98.3.

Macedon under King Perdiccas II, which impelled the Chalkidikians into rebelling against Athens, was at odds with Athens so Sitalces invaded Macedon in 429 BCE. Sitalces was also spurred to invade Macedon with the purpose of placing Amyntas (Perdiccas’ nephew) on the Macedonian throne; Amyntas and his father were previously driven out from Macedon and sought refuge with Sitalces’ court.

“And since he was at the same time on bad terms with Perdiccas, the king of the Macedonians, he decided to bring back Amyntas, the son of Philip, and place him upon the Macedonian throne.” – The Library of History by Diodorus Siculus, 12.50.4.

Sitalces ravaged the lands of both the Chalkidikians and the Macedonians, the latter feared to face this great army so some submitted to the Thracians while others gathered their crops and hid within their strongholds. The momentum waned as Sitalces saw that the Athenians had failed to fulfill their promise to aid the Odrysians with ships and an army, that the harsh winter was wearing down his men and that the Greeks (Thessalians, Achaeans, Magnesians, etc.) were assembling a vast army to repel them. Sitalces and Perdiccas II of Macedon came to terms, the Odrysians retreated and Perdiccas’ gave his sister’s (named Stratonice) hand in marriage to Sitalces’s nephew (Seuthes I). Sitalces, just like his father, died while trying to unify the Thracians (the Triballi killed Seuthes, the Thyni killed his father Teres).

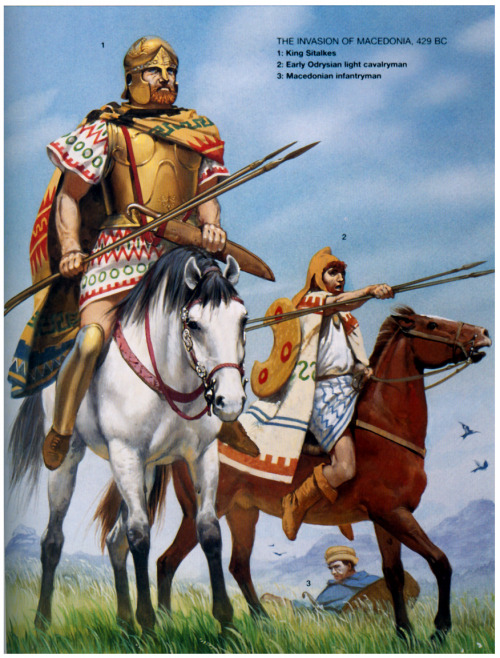

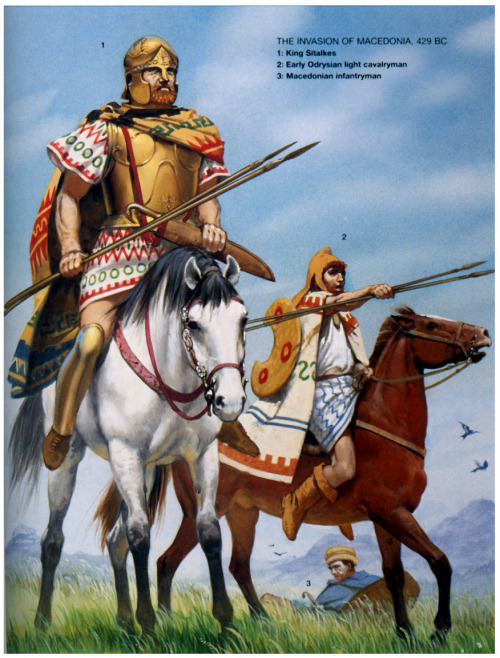

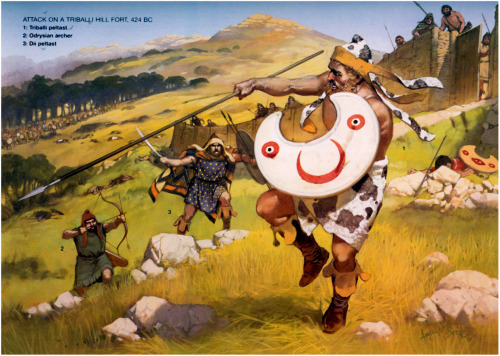

^ Osprey – ‘Men-at-Arms’ series, issue 360 – The Thracians, 700 BC-AD 46 by Christopher Webber and Angus McBride (Illustrator). Plate A: The Invasion of Macedonia. A1: King Sitalces – “The Thracian king is based on archaeological evidence and wears a bronze bell cuirass, bronze Chalkidian helmet, bronze greaves, and a Thracian cloak. He carries two javelins and a kopis. His breast plate is decorated with dragons’ heads, and his helmet with a griffin and palmettos. The helmet comes from an unknown site in Bulgaria and is dated to the second half of the 5th century. The silver harness ornaments come from Binova tumulus in Bulgaria”. A2: Early Odrysian light cavalryman – “This horseman is based on a painting on a 5th century pelike from Apollonia. He carries two javelins, and a pelta is slung on his back. Greek vase paintings show Thracian light cavalry dressed the same as the peltasts, in patterned tunic, foxskin cap, fawnskin boots and long cloak. Other less sophisticated cavalry dressed very simply in a pointed hat and long flowing tunic, and they are indistinguishable from Skythian cavalry. Some 4th century Thracian metalwork shows the cavalrymen bareheaded and with bare feet, a medium-length flowing cloak and simple tunic.” A3: Macedonian infantryman – “The Stricken Macedonian infantryman comes from the early 3rd century Kazanluk tomb paintings. He is thought to be Macedonian because of his location on the frieze, and his peculiar hat resembling the kausia of the Macedonian warrior nobility; but he may be Thracian, because the Macedonians do not use oval shields, and because of his similarity to the Thracian warriors on the same painting. He wears a blue cloak and carries a kopis and two javelins. His shield is oval with the top and bottom cut square, like the later Celtic thureos. A 5th century Macedonian infantryman would be carrying a circular wicker shield, animal-skin cloak and wearing sandals (or going barefoot) instead of shoes.”

During the Peloponnesian War, thirteen thousand javelin-wielding swordsmen from the Dii tribe (Thracians) were hired by the Athenians to act join in the Sicilian expedition but they arrived too late. The Athenians sent them back to Thrace since they did not wish to be burdened into paying mercenaries they couldn’t make use of. This changed, however, when a series of failures befell them which pressured them into hiring the Thracian mercenaries once again as coastal raiders. When these Dii (Thracian) mercenaries arrived at the Boeotian city of Mycalessus:

“[4] The Thracians, bursting into Mycalessus, sacked the houses and temples and butchered the inhabitants, sparing neither youth nor age, but killing all they fell in with, one after the other, children and women, and even beasts of burden, and whatever other living creatures they saw; the Thracian race, like the bloodiest of the barbarians, being ever most so when it has nothing to fear. [5] Everywhere confusion reigned and death in all its shapes; and in particular they attacked a boys’ school, the largest that there was in the place, into which the children had just gone, and massacred them all. In short, the disaster falling upon the whole town was unsurpassed in magnitude, and unapproached by any in suddenness and in horror.” – The Peloponnesian War by Thucydides, 7.29.4-5.

Their victory was short-lived however since the Thebans (Boeotians from the city of Thebes) rushed to the aid of the pillaged city and utterly slaughtered the Dii (Thracians) mercenaries. The Thebans took back the looted goods and pursued the fleeing Thracians back to their ships where the “greatest slaughter took place while they (the Thracians) were embarking, as they did not know how to swim” (Thucydides, 7.30.2).

“those in the vessels on seeing what was going on onshore moored them out of bow-shot: in the rest of the retreat the Thracians made a very respectable defence against the Theban horse, by which they were first attacked, dashing out and closing their ranks according to the tactics of their country, and lost only a few men in that part of the affair. A good number who were after plunder were actually caught in the town and put to death.” – The Peloponnesian War by Thucydides, 7.30.2.

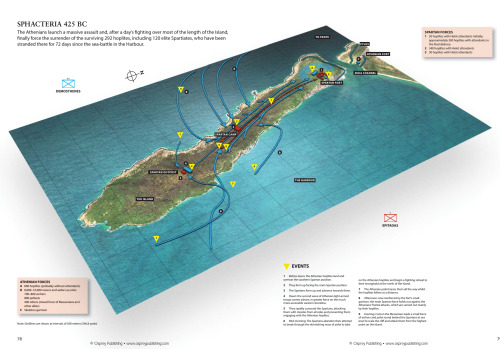

Battle of Sphacteria, 425 BCE:

The famed Athenian politician and general Cleon rallied support from his countrymen by conveying his lack of fear against the Spartans, boasting that he could overcome the Sparta’s within twenty days’ time and declaring that he would achieve this without risking the life of a single Athenian by instead employing foreigners like Thracians peltasts from Aenisas. These Thracians took part in one of the greatest triumphs over the famed Spartans. After the Athenian naval victory over the Spartans (Battle of Pylos, 425 BCE) and its succeeding skirmishes, the remnants of the Spartan forces became stranded on the nearby island of Sphacteria.

^ Osprey – ‘Campaign’ series, issue 261 – Pylos and Sphacteria 425 BC by William Shepherd and Peter Dennis (illustrator). (pg. 78-79).

Here the Spartans were besieged into starvation, dehydration and exhaustion then constantly pursued by Athenian hoplites while being harassed by enemy archers, javelinmen and slingers until they were forced to surrender.

^ Osprey – ‘Campaign’ series, issue 261 – Pylos and Sphacteria 425 BC by William Shepherd and Peter Dennis (illustrator). The Battle on the island: the Spartan last stand (pp. 82–83). “After a fighting retreat over more than half the length of the Island the main Spartan force, depleted by casualties, joined the small garrison in their naturally defended and partly walled stronghold on the highest point at the north end, overlooking the Athenian position across the narrow channel separating Pylos from the Island. For most of the rest of the day they defeated all Athenian attempts to dislodge them. They were much less vulnerable to missile attack and were at last able to do what they did best to beat off efforts to force the position with spear and shield, but they now had little or no water. However, the Athenians could not afford to wait for them to collapse from dehydration because they too had supply problems with their much larger force. Then Comon the Messenian and his mixed, non-hoplite force, managed to work their way round to the rear and scale the cliffs without being seen. They crossed the dead ground in the saddle behind the peak in the centre of the Spartan position and occupied it (1). This is the moment when the small force of about 40 archers, slingers and javelin men attack the defenders from above and behind at a range of 20–30m. ‘The Spartans were now under attack from front and rear and were in the same dire situation, to compare small things with great, as the men at Thermopylae. Just as those men were annihilated when the Persians outflanked them by taking that path, so these Spartans could not hold out any longer now, caught as they were between two fires. They were few fighting many and weakened by lack of food, and they began to fall back with the Athenians controlling every approach to their position’ (IV.37). The Spartans’ weakness would actually have been due to lack of water and probably sheer exhaustion. They may well have had nothing to eat all day but they were not actually starving; Thucydides later mentions that the Athenians discovered a stockpile of food on the Island. In the southern sector the thin Spartan line combining Spartiates (2), perioikoi (3) and Helot attendants (4) is holding firm on the natural and manmade defensive perimeter while the more numerous Athenians hang back as the first missiles find their target. The Harbour with the captured Spartan ships at anchor (5) and the Messenian mainland (6) are in the background to the east.”

At the end of this so-called Battle of Sphacteria, 292 Lacedaemonians (Greeks living under the Spartan state) were taken captive, 120 of which were Elite Spartiates (“Spartans”, full citizens of the Sparta) and the rest being either perioikoi (non-Spartan inhabitants of Lacedaemonia) or Helot attendants (serfs). Athens threatened to kill the captives if the Spartans were to set foot in Attica (region around Athens), holding this over their heads until a series of military setbacks and deaths of high leading commanders on both sides (Sparta’s Brasidas and Athens’ Cleon) opened the path to peace in 421 BCE (Peace of Nicias).

^ Osprey – ‘Men-at-Arms’ series, issue 360 – The Thracians, 700 BC-AD 46 by Christopher Webber and Angus McBride (Illustrator). Plate C – Attack on the Triballi Hill Fort, 424 BC. CI: Triballi peltast – “In 424 Sitalkes attacked the Triballi, and died fighting them. Thracians retreat to their hill forts when attacked; Tacitus (Annals, XLVII) later described the bolder warriors singing and dancing in from of their ramparts. Here a Triballi peltast armed with a long spear wears an unusual dappled cow-hide outfit that only partially covered his body, this is taken from an example of Greek illustrated pottery.” C2: Odrysian archer – “The costumes on this plate are partially based on a scene on a 6th century Attic amphora showing peltasts, an archer, and a cavalryman in combat. This figure is also based on a 4th century silver belt plaque from north-western Thrace showing an archer with beard, plain conical cap, composite bow, and pattern-edged tunic. He would also have a quiver hanging from the waist belt, and possibly a dagger. The quiver would have held around 100 arrows, and would probably have been made from leather. The decomposed remains of quivers made of some organic material, probably leather, have been found at a tomb near Vratsa.” C3: Dii peltasts – “This warrior is armed with a machaira. Many types of curved swords have been found in Thrace, and this example is based on a weapon now on display in a Bulgarian museum. He also carries a circular pelte – as discussed in the text, not all peltai were crescent shaped.”

Head over to my post, ‘THRACIANS, REAPERS OF THE BALKANS’, to learn about their culture, religion, weaponry, armors, battle tactics, and their influence on the ancient world. Their history as well, from the tales in the Iliad to the era of the Greco-Persian Wars, the rise of Macedon under Philip II and his son Alexander the Great, and the Roman conquests of the Balkans.

201 notes

·

View notes

Link

The Wikipedia article of the day for May 7, 2020 is Macedonia (ancient kingdom). Macedonia was an ancient kingdom on the periphery of Archaic and Classical Greece, and later the dominant state of Hellenistic Greece. The kingdom was founded and initially ruled by the Argead dynasty, followed by the Antipatrid and Antigonid dynasties. Home to the ancient Macedonians, it originated on the northeastern part of the Greek peninsula. Before the 4th century BC, it was a small kingdom outside of the area dominated by the city-states of Athens, Sparta and Thebes, and briefly subordinate to Achaemenid Persia. During the reign of the Argead king Philip II (359–336 BC), Macedonia subdued mainland Greece and the Thracians' Odrysian kingdom through conquest and diplomacy, and defeated Athens and Thebes in the Battle of Chaeronea. His son Alexander the Great, commanding the whole of Greece, destroyed Thebes after the city revolted. During Alexander's subsequent campaign of conquest, he overthrew the Achaemenid Empire and conquered as far as the Indus River.

0 notes