#Nonlinear Analysis

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Nonlinear Engineering

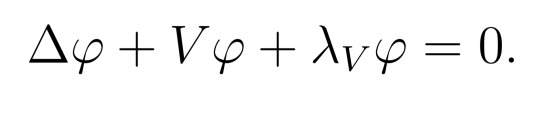

Lineare Systeme sind Systeme, bei denen ein lineares, also proportionelles Verhältnis zwischen Eingangsreiz und Ausgangsreiz besteht. Die Nichtlinearität ist im Bereich des Bauwesens eine geometrische Nichtlinearität, welche von der Unverformbarkeit abrückt, sowie eine physikalische Nichtlinearität, die die Stoff- und Materialgesetze betrifft. Oftmals kommen beide Nichtlinearitäten zugleich zur…

View On WordPress

#Bauingenieur#Baukultur und Ästhetik#Demanega#Engineering#Nachhaltigkeit#Nonkonform#Nonlinear#Nonlinear Analysis#Structural nonlinear analysis#Weiter denken

0 notes

Text

fea dynamics analysis in hyderabad

structural analysis services in hyderabad vibration analysis services in hyderabad stress analysis services in hyderabad feafor failure analysis in hyderabad best feaservices in hyderabad https://3d-labs.com/fea-services/ Comprehensive FEA Services for Enhanced Engineering Design and Analysis Welcome to 3D Labs FEA Services! Unlock the full potential of your engineering designs and simulations with our comprehensive Finite Element Analysis (FEA) services. At 3D Labs, we specialize in providing accurate and efficient FEA solutions to help you optimize your product development process and achieve superior performance. Expertise and Experience: Our team of skilled engineers and analysts have extensive experience in FEA and are well-versed in the latest industry practices. With a deep understanding of engineering principles and advanced simulation techniques, we can deliver reliable and insightful results.

https://3d-labs.com/

#fea linear/nonlinear analysis in hyderabad#finite element analysis services in hyderabad#fea for aerospace in hyderabad

0 notes

Text

Importance of Nonlinear Analysis of Building and Bridges Software

A Software which is used in Calculating the load and stress on a system and also is used in its survey is called Nonlinear analysis. This software is used by the engineers while working on the construction of buildings to get the information regarding the structure and is also used in making the work site secure where the construction work is going on. CSI develops highly acclaimed Nonlinear Analysis of Building And Bridges Software which is used by the structural engineers for getting the information regarding the stress and load applied on the system. Our services are always best in the market ensuring its best quality.

0 notes

Text

MOVIE ANALYSIS AND REVIEW: "Mirror" (1975)

Introduction:“Mirror” (Russian: Зеркало, Zerkalo) is a 1975 Soviet drama film directed by Andrei Tarkovsky. Loosely autobiographical and structured in a nonlinear narrative, the film incorporates poems by the director’s father, Arseny Tarkovsky. Featuring a cast including Margarita Terekhova, Ignat Daniltsev, and Alla Demidova, “Mirror” unfolds around memories recalled by a dying poet, weaving…

View On WordPress

#Andrei Tarkovsky#Artistic expression#Atmospheric soundtrack#Certainly#Cinematic Experience#Cinematic Masterpiece#Existential themes#Farid M. H. Sadeqi#Farid Sadeqi#Film Analysis#Georgy Rerberg cinematography#Hosein Tolisso#Identity exploration#Ignat Daniltsev#Margarita Terekhova#Memory exploration#Mirror (1975 film)#Mohammad Hosein Sadeqi#Nonlinear narrative#Poetry in cinema#Russian film#Soviet cinema#Stream of consciousness#Surreal storytelling#Time perception

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Notework: Victorian Literature and Nonlinear Style

This book is recommended to academics and university students interested in different approaches to fiction writing and the evaluation of literary works published in the late Victorian period and early 20th-century literary criticism. Simon Reader provides a novel approach to the creative writing process and analyses the periphery of fiction.

Victorian literature often presents the two matching pieces of the same artefact – expressed and implied. Naturally, any work of literature written in this period carries traces of the obscure and intertwined. In Notework, Simon Reader draws attention to this fragmented aspect in his investigation of notes, diaries and writings of Charles Darwin, George Gissing, Roland Barthes, Gerard Manley Hopkins, Oscar Wilde, and Vernon Lee. Having been motivated by Darwin’s concept of useless organs, Reader endeavours to understand the impact of these useless fragments on the published works by scrutinizing the disorganised aspect of writing and aims to reach beyond the limitations of form and genre in literature. This book is the most suitable for academics or university students interested in literary criticism or literary history.

Through problematising the literary approach of the New Criticism, Reader argues that close and minimalistic reading of any literary work perceives beauty only at the totality or within the bounds of the text, respectively, and disregards the value of the parts on their own. He illustrates how this approach would focus only on a narrow space of meaning. Instead of disregarding so-called useless texts, he employs them to peer through writers’ personal lives and writing processes. What Reader calls nonlinear style is the totality of personal expressions and textual interactions of these notes, diary entries and other affiliated fragments. However, not all fragments evolve into the parts of a whole or necessarily become related to the fictional product. In other words, they defy their own usefulness. Reader argues this moment as the point when we see fragmentary writing in its own elements. Ultimately, this book draws attention to the process of literary production and a deeper appreciation of a literary text.

In Part I, Reader analyses the nonlinear as a machinery of processing momentary ideas and aspirations. Darwin’s diary entries, for Reader, are instrumental in forming his ideas on evolution because they allow him to roam around natural forms and the environment without any specific aim or argument in need of evidence. This is also true for the novelist George Gissing, whose notes reveal a style of degree zero realism in writing that is free from the necessity of prescribed ends and motivations.

In Part II, the book investigates the nonlinear writing that accompanies the creation of literary work. For Hopkins, there exists an intangible relation between the animate and inanimate aspects of nature and through his notes and observations, the poet yearns to be a part of this vast collective being. Torn between his poetic aspirations and vocational commitments, Hopkins seems to have used the nonlinear style to achieve a congregation of fictional creators with the Christian god. In his study of Wilde’s notes, Reader sees a computer-like attitude for achieving a large flux of information and data.

Reader then steps into the domain of modernity and examines how nonlinear style can work outside the limitations of classical fiction writing. Part III uses the previous analysis of Darwin to examine Vernon Lee’s notes to show how Lee's nonlinear style is an expression of fluctuating aesthetic responses by relinquishing any pretence of genre and form in her career. True to the modernist statement on the possibility of presenting a coherent expression of life through subjective observations of the writer, Lee is in search of life scattered around through objects of triviality and recollection.

Reader, Associate Professor of English at College of Staten Island, the City University of New York, concludes his project in a Darwinian way by proposing the existence of fragmented writings of an author beyond and independently from the affiliated work of fiction. He also foresees the possibility of recovering the individual via contemporary documentation of social media interactions and the impressions recollected through that documentation.

Continue reading...

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

[EOA2] Years In The Future, But Not Many: Adolescence and Time in Act 2 of Homestuck

‘Stories of cultural evolution and of individual adolescent development prioritize the ending; they are primarily narratives of fulfillment.’ – Nancy Lesko (2001)

Act 2 of Homestuck takes place in a single afternoon, and also spans the whole history of life on earth, from before the Pacific Ocean formed to a post-apocalyptic wasteland. As time flashes and contorts and makes a maze of sequential storytelling, our main characters remain frozen at thirteen years old, locked in time at the end of the world. The modern teenager is culturally constructed as a person who is always waiting and preparing, running to keep up with milestones and punished for stepping outside a correct order. Teenagers’ only, and very difficult, job is to adequately prepare for adulthood – an adulthood that is always years in the future, but not many.

This essay looks at adolescence as it is theorized in society and in young adult literature, with a focus on its temporal dimension. It then applies these theories to Act 2 of Homestuck, asking to what extent Homestuck recreates, explores or subverts dominant ideas of adolescence with its characterizations and nonlinear storytelling. It’s about 8,000 words; to skip the theoretical background and just read the Homestuck analysis, Ctrl+F for ‘Paragraphs in the future…’ and read from that section onwards.

This essay is also hosted on ao3 and has a bibliography.

Background: Normal Teenagers, Normal Development

‘A child’s social, and ontological purpose is therefore, it would seem, not to stay a child… any signs of entrenchment or backtracking, like play for example, may be interpreted as indicators of a failure to ���develop’’ – Chris Jenks (2009)

All current adults have experienced childhood and adolescence – it is ‘the only truly common experience of being human’ (Jenks). Adolescence was not theorized in academia until the late 1800s, but had a social meaning much earlier; in 1818, Isaac Taylor published Advice to the Teens, Or, Practical Help Towards the Formation of One’s Own Character at the tender age of fifty-nine. G Stanley Hall, the first scholar of adolescence, was also fifty-nine in 1904 when he characterized the teenage experience as ‘storm and stress’, a time of turbulence, mood and behavioral changes, and conflict with authority.

In this early era of research, children and adolescents were studied in terms of their deviations from the ‘normal adult’, who was explicitly characterized as a middle-class white man. Young people were seen as speedrunning all stages of human evolution before reaching this ‘enlightened’ state at the onset of adulthood; the entirety of history recreated in each individual life. Those seen as ‘further down’ the evolutionary ladder – people of color and the working class in addition to adolescents – were viewed as biologically determined, controlled by their hormones and ‘underdeveloped’ brains, making it the job of those more ‘advanced’ to restrict their behavior. In this way, minors became a marginalized group, and adolescence became a training ground. By positioning teenagers as not yet capable of rational thinking and decision making, it was easy to justify controlling them until they were ‘ready’ to be full members of society.

Modern social scientists generally believe that our idea of ‘the adolescent’ was constructed in the early 20th century, in response to specific social conditions – but many people, including parents, teachers, journalists and young adult fiction authors, retain ideas about the ‘inherent nature’ of teenagers. Science surrounding the ‘teenage brain’ is picked up by popular media and adopted as proof of a biological basis of behavior, and two studies found that preservice teachers saw their future teenage students as ‘incomplete people’. Teenagers have long been described as overly emotional, as unstable due to raging hormones, as disrespectful and rebellious towards authority, delinquents and criminals, lacking individuality, lazy and disengaged, loud and disruptive, politically inactive, hedonistic, immature, as wasting their youth and health, and as not to be taken seriously. In the 21st century, the discourse shifts slightly: teenagers are just as much of a problem, but now they are entitled, inattentive, lacking in intelligence, work ethic and critical thinking skills, reliant on technology, spending too much time indoors, self- and celebrity-obsessed, irresponsible with money, overly sensitive and nihilistic towards the future. When these beliefs are dispersed throughout society and reiterated from all angles, it is no surprise that young people internalize them, and fulfill the prophecy they are told is unavoidable.

Politically, the ‘correct’ development of young people is crucial. The youth are the future adults, and as future adults, it is crucial that they advance society in the ‘right’ direction, and continue along the same path as the current adults. Hand in hand with the idea of teenagers’ inherent nature is the idea that their future trajectory can be changed through the right guidance and the right policy. Placed in a political spotlight, young people are always the ones to be concerned about, never able to formally raise their own concerns. Teenagers are denied the right to vote in countries they will likely be citizens of for their whole lives, and if they attempt to enter political arenas, are widely disparaged with their ideas seen as unrealistic and overly radical. They should instead be waiting their turn, with the expectation that their views will become more moderate by the time they are ‘mature’ enough to guide society.

In her re-theorization of adolescence Act Your Age! A Cultural Construction of Adolescence, Nancy Lesko points out that adolescence is defined through chronological age, and therefore through time. Pointing to theories of the clock as the technology that best defines the modern age, she discusses how youth are kept to a schedule of universalized milestones. One example is age graded schools, where all students are expected to turn thirteen during the seventh grade, and to all achieve the same defined educational standard at this age. Activities such as learning to drive and entering paid work are legally prohibited until a certain age, but people are expected to do these shortly after reaching these milestones, or they will be seen as falling behind. Physical markers of puberty are expected in narrow age ranges, and teenagers are medically pathologized if their bodies mature too fast or too slow. Social development, such as the expectation that adolescents will have their first kisses and first romantic relationships in their early teens, also qualify as milestones. Placed in narrowly age-grouped environments, young people will continually compare themselves to their peers, and those who reach milestones on time are socially rewarded by each other as well as by adults.

These milestones are not end points in themselves, but simply necessary steps along a path of becoming, always focused on the adult a teenager will be. Adults are positioned as superior in society, and to develop as a child is to become more adultlike. When a young person is given increased freedom and responsibility, it is bestowed by adults with the expectation that they will make the decisions of the adult – a teenager told they no longer have a curfew is probably still expected to come home at an adult-defined ‘reasonable time’, otherwise, the curfew will likely be reinstated.

The significance of adolescent decisions and experiences are often minimized. A first heartbreak, a failure to qualify for a sports team, or a decision between two potential friend groups or two academic tracks has a major impact on a teenager’s day to day life, but adults are typically dismissive, framing the issues from their perspective – when the teen is older, they will surely realize the insignificance of this training-ground decision to the arena of real life. Future reflections are privileged over in the moment feelings.

Time, more broadly, has been theorized by philosophers in many different ways, and studies have shown that humans intuitively understand time as both linear (happening one moment after another, continuous and unstoppable) and spatial (held in memory, with moments from the past able to be recaptured and moments from the future rehearsed). Western society heavily privileges the linear view, where time is measurable, unidirectional, and correlated with progress. Once a milestone has been reached, regression is unacceptable. A teenager putting away their Lego sets to get a part time job would be criticized for quitting that job and returning to their toys, and a high school that sees a year-on-year decline in standardized test results is seen as ‘failing’, regardless of other metrics (such as students’ mental health). Individuals and societies must continue to grow and advance with time; a logic which guides our current economic system as well as previous colonial projects. The fear of a society in decline is arguably the primary driving force behind the general obsession with youth, and with the ways the current adolescent generation is inferior to the previous.

This runs contrary to real experiences of time, which involve expansion, compression, twists, circles, loss, gain, running out and having too much. Time passes faster for a fifty year old compared to a fifteen year old. It passes faster when spending time with friends than when waiting for a bus in the rain, faster when anxiously preparing for a final exam than when waiting for results with fingers crossed. Adolescence, in its entirety, passes faster for a teenager raised in poverty who helps provide income and childcare at the age of fourteen than for an upper middle class teenager given a sizable income until they leave college at twenty-two. The past is returned to, over and over again, by adults who relive their high school yearbooks, watch television shows set in high schools, and reconceptualize their own adolescence by watching their children. My personal experience of time changed radically when I took on a seven year project, and started planning for a long term future as well as a short. Time is important not only in how it is spent, but in how it is captured, preserved, and shared.

Technological developments have further changed the experience of time for people of all ages. Writing in 2008, Judy Wajcman discusses the common belief that the pace of life is speeding up, as studies have found that across the second half of the twentieth century, people subjectively experienced feeling more rushed with decreased time for leisure. Some possible explanations discussed are how mobile communication has led to people organizing their lives around blocks of time instead of physical locations, as more activities are available ‘on the go’. There are greater expectations for people to do multiple tasks simultaneously, and mobile devices allow for people to plan and coordinate their time, and therefore optimize it for maximum productivity. Communication and the search for information happen at beyond-human speeds, and time that would historically have been ‘waiting time’ becomes obsolete.

For teenagers especially, social media has changed the experience of time, with young people feeling increased pressure to post frequently, respond to messages in the moment, and record their lives. One teenager explained social media as ‘kind of like documenting your life – you can look back in ten years time, you'll have all these pictures and comments’ while another, discussing taking photographs at Madame Tussauds, suggested that ‘the images became significant after the visit when they could be used to “tell stories” to others, providing digital prompts and enabling conversation about culture’ (Manchester & Pett, 2015). As affordable cultural spaces for teenagers decline, with fewer discos, malls and parks as well as a cultural shift away from parents allowing their children to roam outside, teenagers’ use of time also changes, and young people – especially the working class – report finding themselves with nothing to do.

In contrast, some middle-class young people have the opposite problem, their lives a far cry from the ‘leisure class’ of their peers fifty years before. Some schools begin careers education in middle school, and high achieving youth with college prospects are encouraged to fill their time with extracurriculars, volunteer work and academic preparation, held up against their peers who are using their time more effectively now, and are sure to see better futures because of it. In this way, some teenagers find themselves quite literally waiting for the time to pass and the next stage of life to arrive, while others find themselves working against the clock, trying to complete all preparatory work in time for their entry into adulthood. Despite attempts at standardization, real experiences of both adolescence and time are highly variable, responsive to individual differences, social positions, and new technologies.

Background: Narratives About Youth

‘Behind every disempowered teen narrator is an empowered adult author conveying ideology about the superiority of adult norms.’ – Petrone et al. (2015)

As teenagers became a distinct marketing group, new culture industries grew up around them. The first teen movies, focused on delinquent teenage boys committing crimes due to lack of adequate parenting, were released in the 1950s. In his book The Road to Romance and Ruin: Teen Films and Youth Culture, Jon Lewis argues that via these movies, adults projected their own discontent with modern society onto the teenage characters they created. He views all narrative as ideological, as even the most rebellious and anti-establishment teen movies end up reinforcing adult authority, with characters coming to regret their deviance and ‘reform’ themselves, or being punished for their actions.

Young adult literature was slower to develop, but grew in popularity throughout the 1970s and 80s. So named because it focuses on similar themes to adult books but intended for a younger audience, young adult books can work in any genre, but focus on teenage protagonists and coming of age narratives. Whether real or fantastical, these protagonists navigate the rules and power structures of the world around them, go through some type of trial and eventually learn a lesson crucial to adulthood. It has been argued that the classical narrative is inherently adolescent, as stories by their nature deal with development and change; postmodern fiction does not always follow these rules but it is true for many works for all age groups.

Jon Lewis also discusses the ‘notion of cause and effect’ as it applies to teenagers being ‘at once a mass movement and a mass market’. Many people have argued that the ‘teenager’ was partly created by marketing industries, who, noticing young people’s increased free time and money in the 1950s, created products to fill that niche. Other scholars assert the agency of young people in creating their own subcultures, saying that teen culture arises spontaneously, with adolescents just as likely to adopt a symbol not specifically marketed to them – such as the safety pin’s role in punk culture – as to be swayed by intentional marketing.

In media, the product being sold is an identity to embody. The protagonist of a teen movie can be both relatable and aspirational – they reflect both who the viewer is, and who they want to be. A teenage protagonist is described as ‘relatable’ and ‘authentic’ if they appear to reflect experiences of actual teenagers, who are conceptualized here as a monolith. Petrone et al. point out that such an analysis would seem ridiculous if a character were described as an ‘authentic adult’. They advocate for a more nuanced discussion of ideas surrounding adolescence in fiction – a Youth Lens, which questions how literature represents adolescence, what assumptions the story makes about youth and how that frames plots and characterizations, and to what extent the text reinforces or subverts the dominant understandings. They believe this could pave the way for more varied representations of teenagers, which could positively impact young readers, as ‘writers who foreground examples of youth who do not follow conventional expectations of adolescence can shift how youth might be understood’.

Young adult literature is typically written by adult authors, capturing a reflection of teen culture instead of the reality. It is also regulated by adults – editors and publishers who decide whether a book can be marketed for young adults, and librarians and bookstore owners who decide whether to categorize it as such. Mature themes – including mental health, death, drug abuse, sex, and structural issues such as racism – do feature in young adult fiction, but there are no formal guidelines, and any book seen as ‘going too far’ is liable to be kept away from teenagers.

Writing about young adult fantastical fiction, Alison Waller shows how fantasy narratives reinforce adult norms just as much as realistic fiction; the expectations of growth on a young witch, werewolf or ‘chosen one’ are not radically different from those on real life teenagers. A common theme in dystopian and high fantasy fiction sees a teenage protagonist framed as the only hope for the future, a person prophesized to both change and save their world. Although this narrative may seem progressive as it allows for radical change, in reality these characters are generally guided by wiser adult characters who influence their decisions, and the story is not so different from the real life expectation that the next generation will save us from the problems caused by the previous.

In time travel narratives specifically, a protagonist may go back in time to a situation where they have improved agency and a subjectively better life, but by the end of the story, will voluntarily decide that returning to the present is the right thing to do. A temporary move backwards gives this character the tools they need to succeed at the next stage of life, and overall, their chronological and developmental trajectory is not disrupted. Where a secondary character chooses the past over the future, the narrative tends to treat them with anxiety, positioning them as cautionary tales or as mistakes in need of fixing.

Novels, movies and video games are typically released as completed works – the creators know how the story ends before the work is released. This may not apply to books in a series, and also does not apply to many television shows, comic books, or audio dramas. In a format such as the sitcom, the growing up narrative is complicated – a teenage character may learn a lesson about sensitivity to others’ emotions in one episode, and return to their previous self-centered ways in the next, thereby allowing ‘adolescent’ to be a primary descriptor of the character, not a state to be grown out of. Creators who are teenagers themselves, such as published British author Rachael Wing and many online writers producing fanfiction and original fiction about characters their age, also present a new paradigm. Although they may be influenced by the judgments of adults, they are still writing based on their present experiences instead of memories and observations.

The internet expands possibilities for both narratives and creators. A work posted serially online has the chance to respond in real time to a young audience, and there are far fewer restrictions on what can be posted on the internet, meaning that stories can be made accessible to young adults even if a major publisher or a parent would disapprove. As the internet itself is an ‘adolescent’ rather than a ‘mature’ medium, exploring the possibilities of the medium itself could go hand in hand with disrupting a typical coming of age narrative.

Paragraphs in the future…

‘Try not to be so linear, dear.’ (p.421)

Homestuck is written by Andrew Hussie, a former teenager who turned 30 while writing Act 2 in 2009. Its principal characters are teenagers and like most stories, it is written from memories of being a teenager and observations of what teenagers are like today. Its first act is entirely linear, but Act 2 begins to explore time, continuity, and cause and effect. Readers can no longer assume that a page takes place after its preceding page, and the main characters – John, Rose, Dave and the Wayward Vagabond – all exist at different points along the timeline.

I believe that Act 2 represents time as it is actually experienced by teenagers, where growth and personal development are not always linear and not always in sync with that of others. John, Rose and Dave are all growing up in the 2000s USA, and are all subject to roughly the same cultural expectations as described in the earlier sections, just as the overall work is written in that context. Looking at each character in turn, I will discuss to what extent they conform to dominant conceptions of ‘the teenager’ and how they experience time within the narrative, with a view to asking whether Homestuck could offer a new understanding of adolescence.

John Egbert

‘And even meanerwhile, in the present. Sort of. Once again, the slippery antagonist eludes you.’ (p.385)

As the principal character and the first introduced, John’s time is arbitrarily defined as ‘the present’ – pages 334 and 385 both say as such. However, at the end of act 1, John is transported to a ‘realm untouched by the flow of time’ (p.421) and while time continues to pass for him, it’s not necessarily in step with Earth time, indicated by the ??:?? timestamps on his Pesterlogs. As such, John’s ‘normal’ development has been stalled on the day he becomes a teenager, and he’s locked off from the future of his society.

For John, time and space are linked. Although he has been removed from time and therefore from normal expectations, he’s still stuck in his house, the one piece of his culture that he brought with him. The picture John’s dad pinned to the fridge and the green slime pogo ride John continues to define himself by in this act both keep him tied to his childhood. While he’s here, John can’t escape a multitude of authority figures. His dad has been kidnapped, but still leaves notes around the house congratulating John on his maturity – ‘You are strong enough to lift the safe. You are now a man… I know you will take this responsibility seriously’ (p.546).

With Dad gone, Nannasprite steps in, having not seen John since he was very young. She restores John’s bedroom door to its hinges and restores the family order in the house, giving advice, controlling what John knows, and baking unprecedented amounts of cookies. Nannasprite calls John a ‘good boy’ (p.428), and the Wayward Vagabond’s first command to John is ‘BOY.’ (p.252), a word with assumptions about both John’s gender and current stage of life. Rose and WV also have guardianlike roles over John, able to control how he spends his time.

John is younger than Rose and Dave by a few months, but retains far more childlike qualities. His priorities lean towards play and silliness, as shown when he captchalogues shaving cream in case he suddenly needs to make a Santa beard (p.488) or makes a tent out of cruxite dowels (p.615), and he isn’t in any hurry to reach the signifiers of adulthood, such as shaving (p.544) or taking personal responsibility (p.643). The trait John most shares with the stereotypical teenager is poor emotional regulation – both his excitement and his frustration are obvious on his face and regularly interfere with his behavior (for example, p.429, p.637).

He passes the time instead of using the time, and is easily swayed by his peers. He has a drive for autonomy and self preservation, and will attempt to stand up for himself, but usually ends up deferring to the authority of his friends or guardians. He’s not very self-motivated except when it comes to putting bunnies back in boxes, and he enjoys consuming media, not all of which is age-appropriate – three of the movies on his wall are R-rated, including Con Air. He also plays popular video games and buys media merchandise such as T-shirts and posters, so falls into a mainstream youth marketing demographic.

As a prophesized savior positioned to undertake a hero’s journey, John is a classic young adult protagonist. He demonstrates the idea that the youth are our only hope, though they still require guidance from previous generations and are defined by their opposition to adulthood (seen through Nannasprite’s presence). However, despite Skaia influencing Earth since before life itself existed (p.757), it wasn’t until its power was harnessed into a video game that it began to threaten the world – youth’s popular culture is the thing that sends us all into decline, even if that culture was created and marketed by adults.

The earth already being ‘done for’ (p.427) allows for a subversion of the typical progress narrative. Page 757 indicates that Sburb may be influenced by ancient technology from outside of Earth, The end goal is not known, making John’s narrative defined by the journey and not by the ending, highlighting adolescence as a meaningful experience in and of itself, not only because of where it leads. And Sburb is already poking fun at John’s culture – the echeladder (p.405) parodies the milestone progression of youth, filled with meaningless and generic titles placed in an arbitrary order.

John’s destiny to ascend through the Seven Gates to Skaia, fighting with the light kingdom and attempting to overcome the dark forces’ destined win, could be read as an ascension from childhood to adulthood. John would be moving away from the sinful childlike state where young people are ruled by their base instincts of hunger, sleep, hormones and emotions, towards a rational and enlightened adulthood. But an inversion of this metaphor would work, too. John could move away from his culture’s ideal adult that he’s been told he’ll become – a person who is cynical, conformist, an obedient worker, driven by money and personal success – back towards the childlike state, retaining the open-mindedness, sense of whimsy and possibility, and creativity of childhood. Earth is done for, and so there’s no reason John should still be tied to the linear march of the culture he came from. He is perfectly positioned to imagine a new paradigm of adolescence, if he can break away from the ties – his house and his guardians – that try to tie him down to the ‘old ways’.

Rose Lalonde

‘To hear his mammoth belly gurgle is to know the Epoch of Joy has come to an abrupt end.’ (p.302)

In the narrative, Rose’s time is defined as the near future. Although her story directly overlaps with John’s, putting them at the same point in time, Rose is three timezones ahead and refers to other timezones as ‘younger’ (p.174). It’s night time for her, which visually distinguishes her panels and gives her story a more adult atmosphere. She is future oriented and proactive, planning for the next thing, and typically portrayed as one step ahead of John.

Rose has experienced the passage of time quickly, and has not had the luxury of lingering in childhood as John has. With a mother who is inattentive towards raising her and communicates through daily arguments (p.389) and ‘notes’ on the fridge (p.366), Rose likely had to develop independence and adult traits at a young age. She would be considered ‘precocious’, a word typically carrying a negative or judgmental tone describing a young person whose achievements or inclinations are happening ‘too soon’. In the narrative, Rose is continually running out of time, watching the battery on her laptop slowly drain and the forest fire surrounding her house creep closer. This anxiety of something yet to come positions Rose as a teenager who is awaiting the future and making use of every possible moment to prepare for it.

Educationally, she has a larger vocabulary than the average person her age, and likely a higher reading level. Practically, she understands construction and generator safety, has a good grasp of modern technology such as computers as well as classic skills such as knitting, and the hand eye coordination to do these things well. She demonstrates abstract and critical thinking, and attempts – with varying levels of success – to understand the consequences of her actions. She shows an understanding of a world greater than herself when she wishes Jaspers had been allowed to decompose (p.414) and avoids allocating her grimoire to her strife specibus (p.297). Despite being raised by a rich mother, she enjoys a challenge and is willing to work hard, rejecting childlike wish-fulfillment fantasies such as princesses and wizards.

Rose is a teenager who attempts to fill her time with activities she sees as productive and as bettering her as a person. She has internalized adult values and would prefer to get there too soon than be left behind, and she works hard to define herself through timeless, sophisticated hobbies such as literature, knitting and the violin, generally resisting mass culture that would be typically marketed to teens; unlike John she disrupts the idea of the teenager as mindless consumer or as defined by her peers’ interests. She tries to avoid juvenile behavior and scorns it in others (p.249) and is very attuned to cultural expectations, feeling a nebulous pair of eyes upon her judging the appropriateness of her actions, which affects her decisions (p.370), almost as if she is trying to skip the complicated, messy parts of being a modern teenager and move directly from childhood into rational adulthood.

It’s rare for Rose to regress into childlike behavior, such as the ‘W’ mustache (p.370) and the Youth Roll (p.379), and she usually ends up regretting or correcting the behavior afterwards (p.398, p.380). Her disdain for her mother suggests that she is self-correcting and trying to parent herself in response to these ‘slips’. Notably on page 440, Rose works on her GameFAQs, which are intended as an informative guide to future players. Accidentally slipping into a frustrated and self-berating personal anecdote, she strikes out the passage and again criticizes her own regression, which is immediately followed by a narrative shift into Rose’s actual past.

Rose struggles with patience, and with waiting for other people to catch up to her. She understands the seriousness of her situation; for her adolescence is a time of survival, her decisions now liable to affect her entire future. Act 2’s title, ‘Raise of the Conductor’s Baton’, appears in the text in relation to Rose - ‘Somewhere a zealous god threads these strings between the clouds and the earth, preparing for a symphony it fears impossible to play. And so it threads on, and on, delaying the raise of the conductor's baton’ (p.307). This certainly links to Rose’s experience of time, her living in expectant mode for a terrifying, looming future.

Primarily Rose strives for the ‘positive’ markers of adulthood, such as responsibility and educational attainment, but she also tries to be casual regarding sex, such as claiming to enjoy Dave’s bro’s websites (p.419). The only markers of adulthood she openly rejects are alcohol and domestic chores, both of which the text associates with Rose’s mother, who Rose views as a cautionary tale and the ‘wrong’ kind of adult. Through Rose’s relationship with her mother, there is space to question the idea put forward by other media that teenagers become dangers to society through poor parental oversight; Rose is certainly a rebellious and anti-authority teen, but her ‘rebellion’ consists of asserting her own capability and responsibility, such as turning down alcohol in favor of water (p.388).

Rose sees herself as the more responsible of the two of them, but it remains uncertain whether the narrative will legitimize this. By being positioned in a guardianlike role over John she disrupts the typical adult-youth dynamic, and is given a chance to prove her chesslike skills of thinking several steps ahead while staying responsive to new information, evidenced by her GameFAQ updates. However, in the final page of the act, Rose’s ability to manage her own life reaches its limits, and it is her mother who saves her by opening a secret passage, having apparently planned for this all along. Here Rose’s independence is taken from her and she is once again the teenager who needs a firm guiding hand, despite apparently working much harder than her mother. This reinforces a typical authority structure and is dismissive of Rose’s legitimate problems with her mother, as despite her flaws she is still a necessary figure in Rose’s life.

In future acts, Rose’s character arc could go multiple ways, particularly once she enters the Medium and is presumably separated from her mother. The story could legitimize her drive to grow up at a young age and allow her to take on a leadership role that she does seem well positioned for, given her ability to keep a clear head and solve problems in real time. In this narrative, Rose would not be punished or put back in her ‘rightful place’ for speeding through time, instead, her early development would allow her to be valuable to the group, and to challenge herself in ways a thirteen-year-old would not have access to in the real world. Alternatively, Rose could have an arc that allows her to go ‘back in time’ and reclaim her more youthful traits, taking on some of John’s silliness, handing over responsibility or making bad and uninformed decisions when in a new context, for example when she becomes a client player. This could also be subversive if returning from a more adultlike to a more childlike state is portrayed as a valid and meaningful journey in its own right, instead of as someone who grew up too fast returning to their ‘correct’ place in time.

Dave Strider

‘You just don’t have time for this bullshit. You’ll catch up later.’ (p.332)

Dave’s narrative time is defined as the past. His story begins on page 308, at the same moment where John’s story began on page 1. John and Rose are several hours ahead of him by now, and Dave’s storyline is constantly racing to catch up. Like any teen looking around and watching their peers maturing physically and socially while they fail to keep up, Dave is always missing information and excluded from his friends’ activities. The narrator makes sly references to Dave being in the past and unaware of what’s to come (p.314) like a nagging thought in the back of his head, and in every page, he has the relic of a five-year-old movie stamped on his face.

In reality, Dave is not failing to meet developmental milestones – quite the opposite. In a world where the athletic achievement of young men is prized and adults are expected to be in control of their own bodies, Dave is physically fit with quick reflexes, able to fight, jump, dodge and perform an ‘acrobatic fucking pirouette’ (p.579, p.665), even without regular access to food. The original, early 20th century Boy Scouts prepared boys for military service primarily through obedience, a sense of duty, and personal responsibility towards physical development; Dave’s brother with his strict sword-training and Saw trap regime is instilling similar values.

Dave does participate in mainstream culture, evidenced by his regular reading of GameBro and his desire to be ‘cool’ and to like the same things as his brother – but he’s not only a consumer of culture, he’s also a producer. He writes a blog, ostensibly on a regular schedule, and produces a webcomic, combining creative and analytical pursuits. He regularly refers to himself as ‘busy’ (p.309, etc) and says he ‘doesn’t have time’ for things (p.310, 332), has ‘a lot on [his] plate’ (p.333), and that it’s ‘hard to get any work done’ (p.381). Dave sees his internet projects as work, as commitments he needs to make time for, and he’s not afraid to push back against the player’s commands if he thinks they wouldn’t be a good use of his time.

He has the Complete Bullshit desktop application and keeps up with his brother’s projects, and likely other internet culture too, to stay on the cutting edge of irony that he prides himself on. It seems like Dave’s time is largely full and he struggles to fit everything in. He is very aware of the constantly changing, modern society that he lives in and wants to stay on the pulse of these changes. Less than six months after Obama’s election, a black president is no longer noteworthy to Dave (p.287), and he creates remixes with electronic samplers instead of playing classical instruments like his friends. He’s always online and always keeping in real time contact with his friends; he ‘pesters [Rose] like clockwork’ (p.415). Trying to keep the beat of an ever-shifting internet meme culture to stay cool and avoid being outdated at all costs is exhausting, and it’s no wonder Dave sometimes struggles to keep up.

Living in the city, a place where the pace of life is quickest, in a time of rapid technological and cultural change already creates a ‘racing against the clock’ mindset, and Dave’s relationship with his brother compounds this. By modeling himself on Jigsaw, a villain who created complex, physically violent traps with strict time limits, he forces Dave to be constantly on guard, constantly expecting the next danger, yet often a moment too late for it, behaving like an intense ‘no pain, no gain’ style sports coach. On the surface, Dave’s sunglasses, frown and monosyllables look like a rebellious teen movie protagonist, but beneath that, Dave best corresponds to a real life high achieving teenager who is put under pressure to achieve even more by the adults around them.

Dave’s story so far has focused on the ‘campaign of one-upmanship’ between himself and his brother as he fights for his brother’s Sburb game discs – his brother is an obstacle to both his plot development and his emotional development (for example, admitting that he’s uncomfortable with his brother’s hobbies). This is likely setting up a ‘loss of innocence’ story, where Dave has to come to terms with harsh realities of the adult world by recognizing that an authority figure is imperfect. This is a fairly typical growing up narrative that does not disrupt conventional ideas of linear growth, as the adult world is widely seen as darker, more serious, and something young people need to be protected from.

However, I think Dave’s status as a subcultural producer places him outside a typical youth/adult binary. Dave is not overall presented as adultlike, as he follows trends and is fully subservient to the adult in his life, and his hobbies – Sweet Bro and Hella Jeff, sweet bro’s hella blog, and remixing music – don’t place him on a typical path to adulthood. By establishing that Dave sees these as responsibilities, and as things he creates for a real audience of at minimum four people and potentially many more, Dave’s teenage experiences and creations are given importance without needing to be legitimated by adults (such as the narrator or his brother).

Dave’s self-motivation when it comes to his creative pursuits also disrupts ideas of teenagers as lazy or needing to be shaped by outside forces; he’s capable of sticking to a self-imposed schedule. However, his creative drive is part of a real-time responsiveness to internet culture – if he is taken to the Medium, outside the normal progression of time, would he be able to maintain this? An arc that focuses on Dave as a creator instead of Dave as a soldier could do more to complicate a typical youth narrative.

Wayward Vagabond

‘The APPEARIFIER cannot appearify something if it will create a TIME PARADOX’. (p.752)

The Wayward Vagabond is not a human adolescent, and does not come from the same culture as John, Rose and Dave – they discover the concepts of ‘cutlery’ and ‘politeness’ in Act 2, so are a long way from internalizing age-based ideals. As such, although WV exists in the future – their story taking place 413 years after the human characters’ – they are not more advanced, or more adult, than the others.

Alone in a wasteland and free from social influences, WV does not regulate their eating, is described as physically weak, expresses black and white opinions on governance, and loses track of time playing pretend games. At the same time, they show a good understanding of art, chess strategy and precise movements and distances. They pick up social and technological skills quickly and are very attuned to positions in space (p.743), but far less attuned to positions in time (p.755). Many of their actions are similarly nonsensical to John’s, and these moments of whimsy frame WV as childlike.

However, WV has a privileged position in time. Not only are they in the future, but they have the technology to experiment with temporal mechanics. Through a set of screens they are able to look back at and directly influence events from the past; they have authority over at least one young person, and can appearify objects from other points in time.

Being an adult and a child at the same time feels like a time paradox to us, just as appearifying a rotten pumpkin they ate earlier is a time paradox to WV. Having authority over a young person who, if he continued to grow in linear time, would be long dead by the time WV enters the bunker is also a paradox of normal development. By mixing childlike and adultlike traits, WV draws attention to the way roles in society are socially mediated and may not exist outside of their cultural moment. By living in a post-apocalyptic wasteland where advanced technology is lost to the ravages of nature, WV represents a type of person who could live in the future if the world does not follow a path of strict linear progress, but simply of change.

The appearifier and command station in WV’s bunker fundamentally change the function of time in the narrative. Although WV’s mastery of time is limited by the need to avoid paradoxes, if characters take actions to influence or improve the past, they disrupt the norm of future orientation and give equal importance to the past. Indeed, the pages titled ‘Years in the future…’ are not presented as the desirable end goal of the narrative, nor are they a terrible fate to be avoided. They are interesting asides to the story, but they are asides, with the bulk of them taking place in pages hosted outside of the main story. The story structure lets the past and present be centered in themselves, not just through their leading to the future.

The Narrator

‘Maybe you could go bug someone somewhere else for a while? Or at the very least, somewhen else.’ (p.440)

The position of any given Homestuck page within the timeline is uncertain until established by the narrator, who regularly exercises their power to shift back and forth, and to conceal these movements until the player has made a fool of themself. In this way, the narrator is positioned as an adult with perfect knowledge of the timeline, viewing adolescence in its totality. They have transcended the limitations of adolescence and have moved onto a real and meaningful time of life, and will occasionally reference their superior knowledge of future events with winks to the audience while keeping characters out of the loop – ‘you can’t imagine how a video game could save someone’s life’ (p.314) or ‘only… babies who poop in their diapers believe in [monsters]’ (p.387).

However, moments of the narrator criticizing or speaking condescendingly to the teenage characters is surprisingly rare. It happens occasionally, like with ‘This is COMPLETE BULLSHIT.’ (p.458) or ‘The circle of stupidity is complete’ (p.490) but the vast majority of narrative criticism is directed towards the Wayward Vagabond, the only character the narrator regularly speaks directly to. The narrator calls WV stupid on multiple occasions (for example, p.437, p.746), and tells them to defer to Rose’s decision making (p.277), but the majority of narrative text criticizing the kids’ behavior is actually just reporting their own thoughts, either towards themselves – ‘It seems the woman has you at a clear disadvantage’ (p.373) – or towards each other, such as ‘What the hell is that nincompoop doing?’ (p.508). When a command would lead to a bad decision, it’s generally the character who refutes it, not the narrator (p.489). In this way, although the narrator does have superior knowledge, they give center stage to adolescent perspectives.

Implicitly, the narrator controls the flow of time in the story – deciding who to switch to and in what moment of their story, allowing characters to speak or moving focus away from them – and the narrator is willing to indulge the characters in their non-plot critical diversions, rarely hurrying them along when they take extended time to read books or rearrange their sylladex, but allowing the minutiae of their experiences to matter. The narrator lists characters’ interests without judgment – adult characters are interested in clowns, wizards, puppets and sugary foods, while adolescent characters are interested in computer programming, knitting and specimen preservation, with no clear line on ‘acceptable’ interests for a given age group.

Zooming out a layer, Act 2 posits the idea of John, Rose and Dave’s stories available for viewing through a screen, four hundred and thirteen years in the future. As well as reflecting the existence of the webcomic itself, this contrasts the idea of adolescence as a transient state. The 13-year-old versions of these characters are frozen in time on the Wayward Vagabond’s screen. Born in the mid-1990s, these characters are among the first to grow up with social media, and with an internet moving away from anonymity. Their lives being recorded on the command terminal, in Rose’s GameFAQ screenshots (p.510) and in Bro’s Jigsaw puppet (p.570) are not a million miles from the teenagers documenting each other’s lives on Facebook in 2009 – and at the time of Act 2’s writing, it’s not yet certain what the real world impacts of this will be on current young people’s experiences of time.

Conclusion

‘Temporal movement into the future is understood as linear, uni-directional, and able to be separated from the present and the past… a conception of growth and change as recursive, as occurring over and over again as we move into new situations, would reorient us.’ - Nancy Lesko (2001)

Written in 2009, Homestuck carries the baggage of over a hundred years of public discourse around the teenager. Adulthood is seen as the most important stage of life, with teenagers as flawed, incomplete versions who need to be corrected before reaching the end goal of conventional adult society through conforming to a series of linear milestones. The expected development of real teenagers is reflected in the stories told about them, which focus on characters ‘coming of age’ and successfully internalizing adult norms.

By introducing nonlinear storytelling in Act 2, Homestuck represents time as teenagers actually experience it, which gives the comic a chance to explore and question dominant ideas of adolescence and adolescent time. John and Rose have relationships with guardian figures, including the narrator, that reinforce adult superiority, and all three kids have communication breakdowns between themselves and their guardians – but the skills and interests of teenagers are also given importance, and adults are not exempt from narrative criticism. The narrator is happy to indulge the teenagers just as often as to correct them.

The end of Act 2 positions Sburb as an organic entity of sorts, not necessarily created by adults in universe. Sburb encourages linear gameplay with progression up the Echeladder and through the Seven Gates, but the Medium’s position outside of time, and the fact that restoring the Earth is not the game’s goal, allow for narratives of change that are not necessarily narratives of progress, as the characters’ future in rational adult society no longer exists. The comic’s focus on creativity – both the potential of Skaia and with Dave’s role as an artist – means the story could focus on the importance of not losing childlike traits along the path to adulthood.

The narrative structure allows teenage characters to be nonlinear, to move between past and future moments, to experience sudden growth and moments of regression, to overtake their friends and then fall behind. The real-time nature of Homestuck’s creation allows readers to linger in the characters’ day to day moments and to experience their present alongside them, instead of tightly focusing on their plot development, and the reader submitted commands central to Act 2 mean that real life teenagers likely contributed to their own story. Homestuck is still early on in its story, but has already laid the groundwork for a novel conceptualization of time, and therefore an understanding of adolescence as more than just its ending.

#eoa2#milestone#analysis#homestuck#to be honest i think i aimed too high with this and that what i wanted to do here is beyond what im currently capable of#but it was a very valuable experience! and i hope to work on these skills over the next couple years#and to look back at this and see lots of improvement over time!#i do also think theres a lot of good in the bones of this even if the execution isnt great! and so its still important to post :)#chrono

26 notes

·

View notes

Note

I understand that Caliborn/English is controlling the narrative by playing figurative pool with all his time chicanery and narrative console thingy. In many ways the alpha timeline exists solely to propagate his existence. However, I need one point spelled out to me before I say something stupid; Is there support for Caliborn LITERALLY being the 'player' of homestuck? like the one who types in the commands and is erroneously referred to as 'you' by the narration? (I understand those are from user commands I'm moreso asking if it could be plausible, considering everyone has already pointed out how the cals are meant to represent the fans of the time and the commands themselves already remind me of him in their 'DO THIS' 'YES GOOD' kind of way) idk just tell me if I'm speaking crazy talk

i don't think we can identify Caliborn as THE 'player', no, precisely because of what you say about all of those commands coming from different people; some of them are from the mayor, some of them are from the queen... even a copy of trollian can be a substitute for a formal command console.

caliborn is just one reader among a sea of them - because of course he is, he's one of us! - who has managed to become the dominant voice in some fashion. you might liken this to how he always becomes the dominant personality in whatever body he inhabits, perhaps by making precisely-placed commands like the proverbial pool cue; or maybe he's positioned himself as the guy at the top of the food chain, giving the commands to the people who give the commands? like his ownership of karkat's command terminal might suggest.

because you're not crazy when you say there's obvious similarities between the way WV and caliborn direct the story, and I think this is a very deliberate conceptual line drawn between the two characters, with karkat sitting in the middle. here's what andrew has to say about this in his commentary on book 3, page 228;

[...] at any given moment Homestuck is full of surrogates for various factions of the readership. Basically any character who is viewing the actions of other characters on a screen can be seen as a consumer of that story through some form of in-canon digital media. Whether they type in character commands like the exiles, or use Trollian to skip around the "archive" in a nonlinear way like the trolls do, for the sake of "adventure analysis" or to heap scorn on those involved, every narrative-viewing character is temporarily filling the role of the Homestuck reader from a certain angle. Later, cherubs become the ultimate distillation of the idea.

act 6 is all about the "ultimate distillations" of ideas like these, in ways that are both figurative and literal. like how dirk derives his personality profile from that of doc scratch, but is in fact the kernel of doc scratch's personality in the first place. so in this way, it would make some sense as well for lord english to have had some kind of literal influence on the exiles - or at least WV in particular - from the very beginning.

probably relevant, but difficult to fit into anything else i've said in this post: lord english's cursor, a variation on the same cursor used in association with the reader's influence, shows up right as he regurgitates the exact commands given by the mayor: YOU THERE. GIRL.

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

TRYP thoughts on characterization

jack frost // elsa | characterization considerations

PART 4 | THEIR ICE POWERS (OR AU-EQUIVALENT) & SHARED CONNECTIONS:

ground rules + intro

overview: the tl;dr of my personality + dialogue choices

deep dive: characterization, personality, + identity

shared ice powers (or AU-equivalent) + shared connections

questions/points to consider as you write

PART 4 | THEIR ICE POWERS (OR AU-EQUIVALENT) & SHARED CONNECTIONS:

(STAY TUNED FOR AN IN-DEPTH ANALYSIS OF ❄️❄️❄️SNOWFLAKES, FROST, ICE, AND STRUCTURES❄️❄️❄️ [and more???] BY CALLI, @callimara, FORTHCOMING, but also initially explored in mtyk.)

you didn’t think i was going to not mention it, right?? but super honestly i almost forgot to write this section. 😂 i’ve written so many AUs, this point is not even always at the front of my mind anymore, but let’s dig in. ❄️❄️❄️

❄️❄️❄️❄️ this is usually how it goes, i feel, more or less:

a double-edged sword:

elsa’s ice powers are an integral part of her identity, initially a source of both immense strength and bone-deep, soul-wrenching fear. throughout much of her life, she has been taught to suppress her abilities (her emotions), leading her to associate her powers with danger and potential harm, especially to those she cares about. this repression has caused her to view her powers as something to be controlled, rather than fully embraced, leaving her constantly on guard, always fearing that she might lose control and hurt someone.

jack’s unique perspective and transformative influence:

however, as elsa’s relationship with jack develops (in whatever universe), she begins to see her powers in a new light. jack, who also wields ice magic—and is OFTEN the FIRST and ONLY other ice-wielder that she knows of—understands the intricacies and challenges that come with such abilities. unlike others who have only seen elsa’s powers as something to fear or control, jack sees them as a natural extension of who she is—a gift, rather than a curse.

this perspective is transformative for elsa. it allows her to slowly let go (👀) of the fear that has always accompanied her powers and begin to explore their full potential without the constant need to hold back.

liberation, trust, journey toward embracing her powers:

with jack by her side, elsa experiences—depending on the story—a newfound sense of security in using her powers. she no longer feels the need to restrain herself out of fear of causing harm (unless…….. it is angst. 👀). jack’s presence and his own mastery of ice magic provide her with a sense of understanding and acceptance that she has rarely experienced.

unique bond and understanding:

this shared connection through their powers creates a bond between them that goes beyond the physical—it’s in some ways a sort of spiritual trust that they are safe with each other (unless it’s angst, at the center readers, you remember the scene 👀), that they can fully be themselves without judgment or fear. (unless, of course: ANGST.)

eventually, gradually: empowerment and healing:

if/when this freedom does occur, for elsa, this new sense of safety and security in using her powers is a liberating experience. she begins to experiment with her powers in ways she never dared before, discovering new facets of her abilities and pushing the boundaries of what she thought was possible. the trust she feels in jack’s presence allows her to let go of her inhibitions and truly explore the extent of her magic.

it’s a process of self-discovery that is both empowering and healing, as she starts to view her powers not as something to be feared, but as an essential part of who she is.

cycle of growth and healing, strengthening their connection:

this newfound freedom also deepens her connection with jack, thereby pushing them into a cycle of growing and healing (unless: angst 😂, in which case, this cycle may still happen but SLOWLY and PAINFULLY, in stops and starts, in nonlinear patterns).

mutual understanding, support, and solidarity:

as they face challenges together, elsa finds that she can rely on jack not just as a partner in battle (or daily life, depending on the story, which could also be a “battle” 😂), but as someone who understands the unique burden of their shared powers (and, in the cases where they don’t share powers… their shared sense of Sacrifice 🥹 and their love for their younger sisters). this mutual understanding creates a sense of solidarity and, occasionally, camaraderie between them, making both of them feel less alone in their struggles.

growing confidence, deeper connection, shared purposes:

ultimately, elsa’s ice powers, once a source of fear and repression, become a symbol of her growing confidence and self-acceptance. through her relationship with jack, she learns to embrace her abilities without fear, finding strength in the trust and security they share. this transformation allows elsa to not only harness her powers more fully but also to connect with jack on a deeper level, creating a bond that is rooted in mutual understanding, trust, and a shared sense of purpose.

but what about the specific differences in features of their ice/snow/frost/powers?

for specific ice MAGIC features, patterns, habits, and geometrical dendrites (🤣 thanks calli), please note that @callimara will be dropping a DETAILED comparison analysis one day, so stay tuned!

in the meantime, you can see my quick takes in the woman in white, or in ch. 4 of more than you know.

20 notes

·

View notes

Note

3, 12, 17

What work are you most proud of (regardless of kudos/hits)?

Of JUST the pieces written this year, I think Riposte would have to win. We did a lot of excellent character work, meta-analysis, and nonlinear storytelling and the end result is, in my humble and unbiased opinion, masterful.

How many WIP’s do you have in your docs for next year?

You'll never take me alive.

Your favorite character to write this year?

ooo, let's see. One, specific character

I don't know if it really counts as being written "this year," because it was PUBLISHED ON AO3 this year (and large sections polished or rewritten) but it's a rework of an older ficlet....however, Satra the Romulan doctor in Counterpart is always an absolute treat to write.

Ihz, my precious antisocial soft-hearted prickly asshole, was a close second in some desperate small creature.

But BY FAR the most fun I had doing character work IN GENERAL this year is, without a doubt, the master-and-apprentice shenanigans in Perspective.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

@marxistcalvinisthobbesist okay, it's not late at night anymore, and I can respond in a more profound way than I did in this thread.

1. On the topic of trans men and male privilege, nontransfem trans people and tme privilege.

Can you give concrete examples of trans men being invited into male privilege ("offered a leg up", as you put it), and invited into social hierarchy of normative manhood in general? How do you think it happens across different countries and cultures? How is trans manhood evaluated and discussed by the general society?

How are nontransfem trans people situationally engaging in transmisogyny different from transfem people doing the same? E.g. Blaire White attacking Alok Vaid-Menon for her transmisogynist fan base approval. What's the difference on the material level for the perpetrator and the victim of this act?

Note that I am not asking for analysis of the type "well, they're men, so it's logical that they have male privilege", I am asking how you think it manifests in reality and what kind of systemic benefit nontransfem trans people have from transmisogyny.

2. On the topic of the meaning of transfeminine and transmasculine, as well as transition directions.

Could you clarify still, where exactly are transneutral people positioned in your view of gender? I am still bothered by you assuming that everyone transitioning away from manhood is transfeminine and everyone transitioning away from womanhood is transmasculine.

In addition to that, what about people whose transition is nonlinear or not following the set expectations for their assigned gender and current gender identity? What about intersex people, some of whom report being assumed to transition while they actually don't?

Also, at what point does any of it start? I didn't do anything significant with my presentation or self expression for some time after realizing I was trans, what was I back then?

3. On the topic of externally assigning gender labels and assuming experiences.

I think we all here agree that gender assignment in the way that it is conducted by the general society is invasive and abusive, so I'm not sure what's the merit of trying to recreate it in the form of sorting trans people into groups on the basis of their (perceived) material position.

You said that people may be wrong in evaluating what oppression they're affected by. Who do you think is suitable to judge this wrongness? Do you believe it's possible to correctly guess the past and present life circumstances of a stranger?

In addition to that, you said that "people aren't oppressed by transmisogyny for looking like a trans woman, but for being a trans woman". How is that correlated with your view that transmisogyny occurs on the basis of one's position in the society? Do you believe that it's impossible for two people with different gender identities to occupy a similar social position, e.g. a binary trans woman and an agender person both pursuing estrogen HRT and legal gender change to female while using a masculine name and dressing androgynously? Or do you believe only one of these people will be affected by transmisogyny regardless? Or is your point that the agender person needs to be included in trans womanhood and/or transfemininity for the sake of material analysis against their will?

You said I'm wrong in assuming transmasculine and transfeminine are based on individual identification. I think assuming it's okay to apply these labels to people externally is just transphobic.

4. Positionality (in general)

It seems to me like you're trying to add more nuance to gender assignment by saying that trans people are not their assigned gender because they don't occupy the material position associated with their assigned gender. Meanwhile I believe one's gender identity is solely and fully a way to self label, and one's material position comes from a combination of factors that are not necessarily caused by any external expression of this identity (e.g. closeted nontransitioning trans people are still affected by transphobia in the form of trauma they experience while realizing how it shapes and restricts their life).

This is a problem I have with positionality as a theory, because it offers a very "you are how you're treated as" look at identity and social perception. I believe that a person's internal sense of self and the way they're treated are influencing each other, but don't cause each other in any linear predictable manner.

This is probably the root of the problem we're having here, because you hear "man" and think "someone who occupies a social position of a man", meanwhile I hear "man" and think "someone who considers themself a man". My approach allows me to divorce identity from oppression/privilege and discuss both in a way that doesn't rely on telling people that they're not what they say they are or they're not experiencing what they say they do. This is also where we go into the whole "problematic identity" topic, because I don't believe someone identifying in a somewhat unexpected and non intuitive way is committing some kind of a fraud. Transgender identities don't exist to give bystanders meaningful input on your life.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

fea dynamics analysis in india

structural analysis services in india vibration analysis services in india stress analysis services in india FEA for failure analysis in india best FEA services in india

https://3d-labs.com/fea-services/ Comprehensive FEA Services for Enhanced Engineering Design and Analysis Welcome to 3D Labs FEA Services! Unlock the full potential of your engineering designs and simulations with our comprehensive Finite Element Analysis (FEA) services. At 3D Labs, we specialize in providing accurate and efficient FEA solutions to help you optimize your product development process and achieve superior performance. Expertise and Experience: Our team of skilled engineers and analysts have extensive experience in FEA and are well-versed in the latest industry practices. With a deep understanding of engineering principles and advanced simulation techniques, we can deliver reliable and insightful results.

#fea linear/nonlinear analysis in india#finite element analysis services in india#FEA for aerospace in india

0 notes

Text

Enhancing Precision with Nonlinear Structural Analysis Tools

Engineers and architects seeking to elevate their structural designs can greatly benefit from nonlinear structural analysis tools. These advanced software solutions, such as those offered by Extreme Loading, allow professionals to simulate complex behaviors of materials under various load conditions, including dynamic and seismic events. By accurately predicting potential structural failures or deformations, engineers can optimize their designs for safety and efficiency. The Extreme Loading Structural Analysis Software stands out by providing intuitive interfaces and detailed visualizations, ensuring that even the most challenging projects are approached with confidence. Visit their website to learn more.

0 notes

Text

Why Nonlinear Analysis of Buildings and Bridges is Important?

Nowadays 3-Dimensional models are very important for big projects like in Construction of a building , in Building of dams and other in other construction works. The 3-d models give a good idea about how to start the project before working on it . While constructing a building its security is a matter of great importance like when tons of loads are applied, or we can say that Nonlinear analysis of Buildings and bridges is important because it describes the additional bending moments caused by the vertical loads , in this software we focus on the stability of the structure after the load is applied on the structure. Our organisation named CSI India provides highly developed software packages and programmes to examine the structure thoroughly and design of buildings.

0 notes

Text

MXTX thoughts; conventions

The long awaited (not) analysis of MXTX conventions is here! I’ve literally been meaning to talk about this for months but it got sidelined in favour of vicious arguing on PDB about MBTI. Anyways! Obviously this post will contain spoilers, and something I wanted to touch on was 3rd person limited in MXTX, but I already have a post on that here, so feel free to check that out for a better explanation of it. Beware of mediocre analysis ahead, I’m a little rusty (also shoutout to the person who liked some of my posts this morning, you reminded me to actually write something!).

THE AGENDA since this post is long:

Non-linear storylines

Dying and resurrection

Colour symbolism

Character tropes

NON-LINEAR STORYLINES

An interesting thing that follows MXTX’s more thought out works, is the non-linear plotlines she follows in them. This itself is a really good convention of writing in general, especially if it’s done well, and I can safely say that MXTX did it astoundingly well in TGCF. The clear cuts between time periods in relation to each book is an incredible feat, and is something that easily trumps MXTX's other examples of non-linear storylines. Through the use of the jumping back and forth in time, specifically in TGCF, creates an excellent cause and effect, something that is definitely central to the novel. Everything done has an effect, whether that be on the continuation of the plot, or even as a characterisation point, so the non-linear narrative cements that sense of foreboding hanging over everything. A simple sentence said when Xie Lian 17 somehow amounts to a complete upheaval of the heavens 800 years later, unveiling a conspiracy well over 2000 years old. A friendship group dissolving due to difficult circumstances results in a really horrific friendship confession later in the novel. Shi Wudu trying to save his sibling ends his own demise, the crippling of said sibling, and a vengeful ghost with nothing to do anymore. This nonlinear storyline is definitely used in MDZS as well, but I found it a bit more complex, and actually, now that I think about it, is a really good reflection of Wei Wuxian in general. The thing with MXTX, is that all her novels are in 3rd person limited, so they follow our protagonist in 3rd person, but it’s tinged with their own personal views and biases that limit the omniscience of 3rd person. And with MDZS it would be a fair assessment to say that the unordered mess of time leaps in the novel are an excellent indication of Wei Wuxian’s bias leaking through the 3rd person. The incessant jumping is difficult to follow in places (don’t say otherwise), but it’s actually a genius idea because it’s an accurate assessment of the thought process that Wei Wuxian probably follows anyway. I wouldn’t say that this was definitely on purpose however, as MDZS was written before TGCF, so it could just be MXTX growing alongside her writing, but hey, maybe it is a stroke of complete and beautiful genius! Don’t bother mentioning SVSSS, it’s definitely an interesting novel, but it’s not non-linear, at least not as wholly as MDZS and TGCF are. The most you’ll get in SVSSS is like a two line flashback, plus the extra’s, but I think that’s a reflection of when MXTX wrote it.

DYING AND RESURRECTION