#Ned ludd

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

#i just have to know ok#bh6#big hero 6#bh6 the series#big hero 6 the series#ned ludd#bh6 ned ludd#smash or pass

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

When Gogo and Hiro accompany Krei and Judy to the Muirahara Woods for a new piece of land, they run into the legendary Hibagon.

Link to episode:

#big hero 6 the series#big hero 6#bh6 the series#hiro hamada#gogo tomago#ned ludd#mochi bh6#muira-horror!#my art#big hero 6 monogatari#monsters and comets

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

EPISODE #175: NED LUDD'S RETURN

EPISODE #175: NED LUDD’S RETURN

Winter Solstice is coming and the Luddites are celebrating on their flip-phones. Now is the time for EPISODE #175: NED LUDD’S RETURN Listen on your radio in Joshua Tree or Moab or Fresno or various other community stations. with soundscapes by RedBlueBlackSilver, written and hosted by Ken Layne — which tonight includes a piece originally written for Popula. Thanks for supporting this program via…

View On WordPress

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

An interview with organised labour thoughtform, Ned Ludd

Today’s (semi-serious) post is inspired by Anne Johnson’s blog The Gods Are Bored. Anne has been interviewing bored deities for many years, and I thought I’d emulate her by interviewing the nineteenth century apocryphal figure, Ned Ludd.

LB: Whaddup, Ned Ludd?

NL: I see what you did there. “Hanging loose”.

LB: As you should! Thanks for taking the time to speak with me today.

NL: I sense a proposition.

LB: Yes, indeed! You’ve kept abreast of recent technological advances I take?

NL: I have. It’s looking kind of bleak.

LB: This AI business is a little not good.

NL: Oh, I don’t think there’s anything wrong with it per se.

LB: Really? I thought you’d be against it in principle.

NL: I’m not against technology in principle, just capitalism. It’s two different things, but the capitalists want you to see advancement as inextricably bound up in capitalism. There can be advancement just fine without exploitation.

LB: I’m glad you feel that way, I do not want to forswear modern comforts!

NL: Ah, about that…

LB: Bad news, Ned?

NL: Eschewing some modern comforts will probably be necessary. Can’t make an omelette without breaking a few eggs…

LB: Or a few knitting machines, am I right?

NL: Yes! The warning even back then was that mass production for maximal profit is untenable in the long term. As long as technological advancement is the lone purview of the venture capitalist, it is always going to tick down to a doomsday scenario.

LB: So what, practically, are we to do?

NL: Break a few eggs!

LB: What eggs, Ned?

NL: Subscription services, same day delivery, products created in sweatshops, over consumption, doom scrolling, hashtags, white supremacy, major corporations, western individualism, saviour mentality, envy, influencers, the Kardashians, the algorithm…

LB: Whoa! That’s quite a list!

NL: Look, most people still have to participate in the system, but doing so with a little thought and awareness and the willingness to forgo some comforts can go a hell of a lot farther than shrugging your shoulders and saying, Oh, well, everyone else does it. Otherwise everyone will keep doing it until you reach the end of the line, and then what?

LB: What do you think the future is going to look like?

NL: I don’t think there is as much left of it as you all want to believe.

LB: But haven’t people of every era always said that - that the world was going to end?

NL: The world won’t end, just life as you know it. It can either improve or it can get worse. The choices you make now have an effect on that outcome. Individual choices as well as societal mores.

LB: So our choices should be…?

NL: Remember where I had my start: infamous breaker of knitting frames. If you told the original Luddites what the future would look like, they would struggle to grasp it; so much has changed. But they’d recognise the same impulse in things like AI and algorithms that they saw in the factory bosses encroaching on their specialised trade in favour of bad mass production. Your choices should always be for humanity, as much as you can, as often as you can. What’s that poem about coming for your neighbour?

LB: You mean Pastor Martin Niemöller’s First They Came?

First they came for the Communists And I did not speak out Because I was not a Communist Then they came for the Socialists And I did not speak out Because I was not a Socialist Then they came for the trade unionists And I did not speak out Because I was not a trade unionist Then they came for the Jews And I did not speak out Because I was not a Jew Then they came for me And there was no one left To speak out for me

NL: That’s the one! Notice how now, when you most need human solidarity, people are driven apart by hyper specific algorithms that cater to every negative and wanton thought, fear and belief? You don’t think that’s accidental, do you? It’s ironic, in light of the above poem, that even a people who suffered one of the most devastating attempts at extermination can turn around and do that to others. There is no better time to be more human than when all the apps and algorithms are trying to make you less so.

LB: Those are fighting words, Ned Ludd.

NL: I’m a cross-dressing product of organised labour consciousness - did you expect anything less?

LB: Indeed not! It’s why I wanted to do this interview. We’ve talked practical actions - shall we talk impractical ones?

NL: You want to go “full woo”.

LB: I want to go full woo! I don’t think there’s anything wrong with invoking a cross dressing, organised labour consciousness thoughtform to withstand the march of mindless, exploitative progress. It’s been a while, but do you think you’re up for the task?

NL: I’m happy to lead the charge on the “astral”.

LB: Excellent! How can we best petition you?

NL: I have a fondness for ale, hammers, oaths of secrecy, guerrilla warfare, cross dressing, needlework and other specialised skills, assassination, and that “The Cropper Lads” tune.

LB: We might have to skip the assassinations for the time being.

NL: That’s okay, I’m plenty patient.

LB: Err, right. But the ale and that, hey, that’s workable! Any parting thoughts as we wrap up this interview?

NL: The technocrats won’t hesitate to replace you. Replace them first. And: real resistance starts the moment you believe it’s possible it might make a difference.

LB: What a thought to ponder! Thanks for your time, Ned. See you on the astral.

NL: It’s been a pleasure! Donate to Wikipedia!

Well, there ya have it, folks! Some inspiration for resisting the technocrats, mundane and magickal alike. How are you pushing back?

1 note

·

View note

Text

“Enslaved toothbrushes” is definitely NOT a concept I have previously encountered. Nor did I ever consider it necessary, or even desirable, to own an internet-capable toothbrush. I guess I’m just an out-of-touch old fogey, or worse yet, a Luddite.

According to a recent report published by the Aargauer Zeitung (h/t Golem.de), around three million smart toothbrushes have been infected by hackers and enslaved into botnets.

The most cyberpunk thing on your dash today.

21K notes

·

View notes

Text

in general i support scientists in all their perverted endeavors but this notion of a time zone for the moon has me HEATED. smiling, insidious, the tyrannical Human Clock stretches its "civilizing" tentacles into space. the toothèd seeds of capitalism burrow into our beautiful partner satellite. "oh it's just about making sure various countries and corporations can coordinate their moon missions" WELL I THINK ITS BAD. AND I'M UPSET

#going full Ned Ludd for THIS specifically#ai is whatever. im a tech doomer for time zones on the moon.#SHE SHOULD NEVER HAVE TO KNOW ABOUT MICROSOFT TEAMS!!!

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Luddite hearing about who wrote the 2022 English indie rock album Dance Fever:

Florence And The WHAT?!!😡😡😡😤

#luddites#industrial revolution#f+tm#florence and the machine#florence & the machine#florence welch#ned ludd

1 note

·

View note

Text

#bh6 wendy wower#bh6 chief cruz#richardson mole#bh6 ned ludd#alistar krei#big hero 6#big hero 6 the series#big hero 6 memes#textposts#big hero 6 text posts

54 notes

·

View notes

Note

As I've written about before, the Luddites get a bad rap:

They were not ideologically opposed to technology, they were opposed to management using technology to cut their wages and fire workers. They destroyed machines not because they thought the machines were evil and "taking their jobs," but because they understood that the machines were really valuable capital and a major investment of the bosses, so that by destroying them they could hit the bosses in their pocketbooks.

If management finds a way to automate jobs during a strike, is that scabbing?

Peripherally.

The automation itself is more part of the general category of management strategies to restructure workflow and production methods in order to reduce the need for, and thus the power of, labor. This dates back to the origins of Taylorism itself in the 1890s as an effort to “steal the brains from underneath the cap of labor” and through to the emergence of Human Relations and Industrial Psychology in the early 20th century as a means to better control workers. So I think you could see in as essentially equivalent to classic speed-up and stretch-out efforts to maintain production at as low a cost as possible during a strike, and thus break the union.

However, the dirty truth of automation is that there is no clean way to fully substitute machinery for labor. Due to the inherent limitations of technology at any stage of development, you need labor to repair and maintain and monitor automated systems, you need labor to install and operate the machines, you need labor to design and program and manufacture the machines. (This is one reason why the job-killing predictions around automation often fall flat, because the supposedly superior new technology often requires a significant increase in human labor to service the new technology when it breaks. For example, this is why automation in fast food has proven to be so difficult and partial than expected: it turns out that self-checkout machines are actually very expensive to operate in terms of skilled manpower.) And to the extent that a given automation contract or project is being undertaken during a strike in order to break that strike, that’s absolutely scabbing.

134 notes

·

View notes

Text

once again i am posting hand-woven images!

#em draws stuff#...what does one even tag this with. well it is ned ludd shouting at a gundam. make of it what you will.#idea drawn from a joke in the fashion bonus episode of well there's your problem and also the increasing general Situation wrt Art in 2024#the situation's a mess and perhaps I'd smash a few knitting frames myself under the circumstances!!!#oh and the lyrics on the poster are from the robert calvert song of the same name

140 notes

·

View notes

Text

The next product or service that demands that I download their single use app before I can get the thing I paid for is getting a robust low-tech intervention delivered directly to their CEO

0 notes

Text

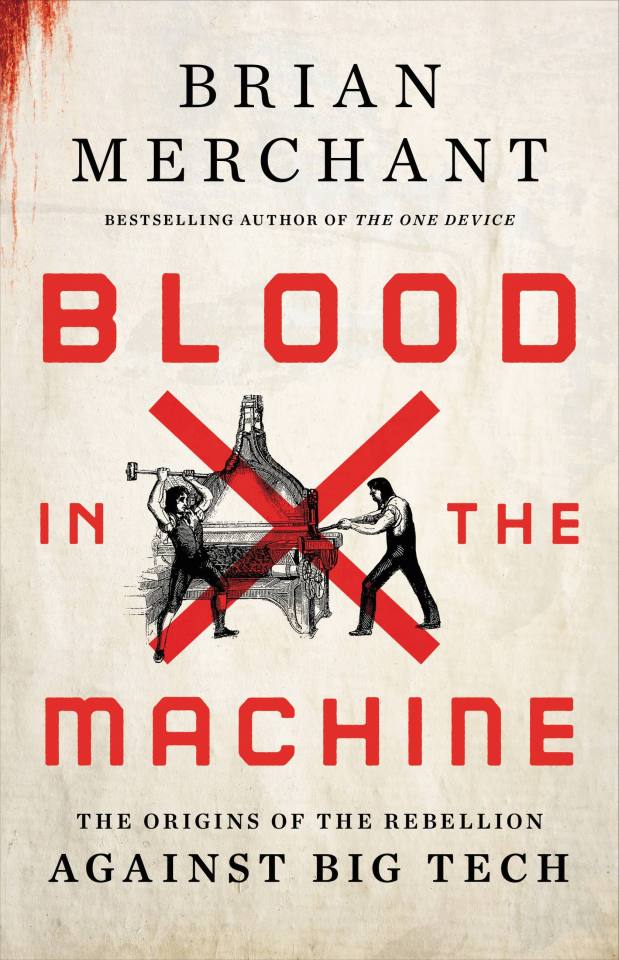

Brian Merchant’s “Blood In the Machine”

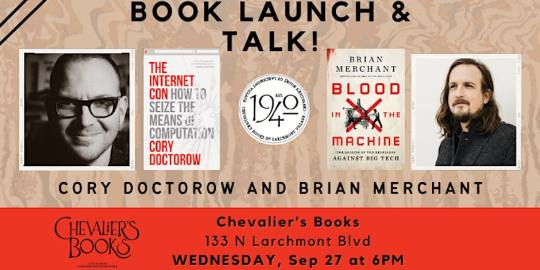

Tomorrow (September 27), I'll be at Chevalier's Books in Los Angeles with Brian Merchant for a joint launch for my new book The Internet Con and his new book, Blood in the Machine. On October 2, I'll be in Boise to host an event with VE Schwab.

In Blood In the Machine, Brian Merchant delivers the definitive history of the Luddites, and the clearest analysis of the automator's playbook, where "entrepreneurs'" lawless extraction from workers is called "innovation" and "inevitable":

https://www.littlebrown.com/titles/brian-merchant/blood-in-the-machine/9780316487740/

History is written by the winners, and so you probably think of the Luddites as brainless, terrified, thick-fingered vandals who smashed machines and burned factories because they didn't understand them. Today, "Luddite" is a slur that means "technophobe" – but that's neither fair, nor accurate.

Luddism has been steadily creeping into pro-labor technological criticism, as workers and technology critics reclaim the term and its history, which is a rich and powerful tale of greed versus solidarity, slavery versus freedom.

The true tale of the Luddites starts with workers demanding that the laws be upheld. When factory owners began to buy automation systems for textile production, they did so in violation of laws that required collaboration with existing craft guilds – laws designed to ensure that automation was phased in gradually, with accommodations for displaced workers. These laws also protected the public, with the guilds evaluating the quality of cloth produced on the machine, acting as a proxy for buyers who might otherwise be tricked into buying inferior goods.

Factory owners flouted these laws. Though the machines made cloth that was less durable and of inferior weave, they sold it to consumers as though it were as good as the guild-made textiles. Factory owners made quiet deals with orphanages to send them very young children who were enslaved to work in their factories, where they were routinely maimed and killed by the new machines. Children who balked at the long hours or attempted escape were viciously beaten (the memoir of one former child slave became a bestseller and inspired Oliver Twist).

The craft guilds begged Parliament to act. They sent delegations, wrote petitions, even got Members of Parliament to draft legislation ordering enforcement of existing laws. Instead, Parliament passed laws criminalizing labor organizing.

The stakes were high. Economic malaise and war had driven up the price of life's essentials. Workers displaced by illegal machines faced starvation – as did their children. Communities were shattered. Workers who had apprenticed for years found themselves graduating into a market that had no jobs for them.

This is the context in which the Luddite uprisings began. Secret cells of workers, working with discipline and tight organization, warned factory owners to uphold the law. They sent letters and posted handbills in which they styled themselves as the army of "King Ludd" or "General Ludd" – Ned Ludd being a mythical figure who had fought back against an abusive boss.

When factory owners ignored these warnings, the Luddites smashed their machines, breaking into factories or intercepting machines en route from the blacksmith shops where they'd been created. They won key victories, with many factory owners backing off from automation plans, but the owners were deep-pocketed and determined.

The ruling Tories had no sympathy for the workers and no interest in upholding the law or punishing the factory owners for violating it. Instead, they dispatched troops to the factory towns, escalating the use of force until England's industrial centers were occupied by literal armies of soldiers. Soldiers who balked at turning their guns on Luddites were publicly flogged to death.

I got very interested in the Luddites in late 2021, when it became clear that everything I thought I knew about the Luddites was wrong. The Luddites weren't anti-technology – rather, they were doing the same thing a science fiction writer does: asking not just what a new technology does, but also who it does it for and who it does it to:

https://locusmag.com/2022/01/cory-doctorow-science-fiction-is-a-luddite-literature/

Unsurprisingly, ever since I started publishing on this subject, I've run into people who have no sympathy for the Luddite cause and who slide into my replies to replicate the 19th Century automation debate. One such person accused the Luddites of using "state violence" to suppress progress.

You couldn't ask for a more perfect example of how the history of the Luddites has been forgotten and replaced with a deliberately misleading account. The "state violence" of the Luddite uprising was entirely on one side. Parliament, under the lackadaisical leadership of "Mad King George," imposed the death penalty on the Luddites. It wasn't just machine-breaking that became a capital crime – "oath taking" (swearing loyalty to the Luddites) also carried the death penalties.

As the Luddites fought on against increasingly well-armed factory owners (one owner bought a cannon to use on workers who threatened his machines), they were subjected to spectacular acts of true state violence. Occupying soldiers rounded up Luddites and suspected Luddites and staged public mass executions, hanging them by the dozen, creating scores widows and fatherless children.

The sf writer Steven Brust says that the test to tell whether someone is on the right or the left is simple: ask whether property rights are more important than human rights. If the person says "property rights are human rights," they are on the right.

The state response to the Luddites crisply illustrates this distinction. The Luddites wanted an orderly and lawful transition to automation, one that brought workers along and created shared prosperity and quality goods. The craft guilds took pride in their products, and saw themselves as guardians of their industry. They were accustomed to enjoying a high degree of bargaining power and autonomy, working from small craft workshops in their homes, which allowed them to set their own work pace, eat with their families, and enjoy modest amounts of leisure.

The factory owners' cause wasn't just increased production – it was increased power. They wanted a workforce that would dance to their tune, work longer hours for less pay. They wanted unilateral control over which products they made and what corners they cut in making those products. They wanted to enrich themselves, even if that meant that thousands starved and their factory floors ran red with the blood of dismembered children.

The Luddites destroyed machines. The factory owners killed Luddites, shooting them at the factory gates, or rounding them up for mass executions. Parliament deputized owners to act as extensions of law enforcement, allowing them to drag suspected Luddites to their own private cells for questioning.

The Luddites viewed property rights as just one instrument for achieving human rights – freedom from hunger and cold – and when property rights conflicted with human rights, they didn't hesitate to smash the machines. For them, human rights trumped property rights.

Their bosses – and their bosses' modern defenders – saw the demands to uphold the laws on automation as demands to bring "state violence" to bear on the wholly private matter of how a rich man should organize his business. On the other hand, literal killing – both on the factory floor and at the gallows – was not "state violence" but rather, a defense of the most important of all the human rights: the rights of property owners.

19th century textile factories were the original Big Tech, and the rhetoric of the factory owners echoes down the ages. When tech barons like Peter Thiel say that "freedom is incompatible with democracy," he means that letting people who work for a living vote will eventually lead to limitations on people who own things for a living, like him.

Then, as now, resistance to Big Tech enjoyed widespread support. The Luddites couldn't have organized in their thousands if their neighbors didn't have their backs. Shelley and Byron wrote widely reproduced paeans to worker uprisings (Byron also defended the Luddites in the House of Lords). The Brontes wrote Luddite novels. Mary Shelley's Frankenstein was a Luddite novel, in which the monster was a sensitive, intelligent creature who merely demanded a say in the technology that created him.

The erasure of the true history of the Luddites was a deliberate act. Despite the popular and elite support the Luddites enjoyed, the owners and their allies in Parliament were able to crush the uprising, using mass murder and imprisonment to force workers to accept immiseration.

The entire supply chain of the textile revolution was soaked in blood. Merchant devotes multiple chapters to the lives of African slaves in America who produced the cotton that the machines in England wove into cloth. Then – as now – automation served to obscure the violence latent in production of finished goods.

But, as Merchant writes, the Luddites didn't lose outright. Historians who study the uprisings record that the places where the Luddites fought most fiercely were the places where automation came most slowly and workers enjoyed the longest shared prosperity.

The motto of Magpie Killjoy's seminal Steampunk Magazine was: "Love the machine, hate the factory." The workers of the Luddite uprising were skilled technologists themselves.

They performed highly technical tasks to produce extremely high-quality goods. They served in craft workshops and controlled their own time.

The factory increased production, but at the cost of autonomy. Factories and their progeny, like assembly lines, made it possible to make more goods (even goods that eventually rose the quality of the craft goods they replaced), but at the cost of human autonomy. Taylorism and other efficiency cults ended up scripting the motions of workers down to the fingertips, and workers were and are subject to increasing surveillance and discipline from their bosses if they deviate. Take too many pee breaks at the Amazon warehouse and you will be marked down for "time off-task."

Steampunk is a dream of craft production at factory scale: in steampunk fantasies, the worker is a solitary genius who can produce high-tech finished goods in their own laboratory. Steampunk has no "dark, satanic mills," no blood in the factory. It's no coincidence that steampunk gained popularity at the same time as the maker movement, in which individual workers use form digital communities. Makers networked together to provide advice and support in craft projects that turn out the kind of technologically sophisticated goods that we associate with vast, heavily-capitalized assembly lines.

But workers are losing autonomy, not gaining it. The steampunk dream is of a world where we get the benefits of factory production with the life of a craft producer. The gig economy has delivered its opposite: craft workers – Uber drivers, casualized doctors and dog-walkers – who are as surveilled and controlled as factory workers.

Gig workers are dispatched by apps, their faces closely studied by cameras for unauthorized eye-movements, their pay changed from moment to moment by an algorithm that docks them for any infraction. They are "reverse centaurs": workers fused to machines where the machine provides the intelligence and the human does its bidding:

https://pluralistic.net/2021/02/17/reverse-centaur/#reverse-centaur

Craft workers in home workshops are told that they're their own bosses, but in reality they are constantly monitored by bossware that watches out of their computers' cameras and listens through its mic. They have to pay for the privilege of working for their bosses, and pay to quit. If their children make so much as a peep, they can lose their jobs. They don't work from home – they live at work:

https://pluralistic.net/2021/01/22/paperback-writer/#toothless

Merchant is a master storyteller and a dedicated researcher. The story he weaves in Blood In the Machine is as gripping as any Propublica deep-dive into the miserable working conditions of today's gig economy. Drawing on primary sources and scholarship, Blood is a kind of Nomadland for Luddites.

Today, Merchant is the technology critic for the LA Times. The final chapters of Blood brings the Luddites into the present day, finding parallels in the labor organizing of the Amazon warehouse workers led by Chris Smalls. The liberal reformers who offered patronizing support to the Luddites – but didn't imagine that they could be masters of their own destiny – are echoed in the rhetoric of Andrew Yang.

And of course, the factory owners' rhetoric is easily transposed to the modern tech baron. Then, as now, we're told that all automation is "progress," that regulatory evasion (Uber's unlicensed taxis, Airbnb's unlicensed hotel rooms, Ring's unregulated surveillance, Tesla's unregulated autopilot) is "innovation." Most of all, we're told that every one of these innovations must exist, that there is no way to stop it, because technology is an autonomous force that is independent of human agency. "There is no alternative" – the rallying cry of Margaret Thatcher – has become our inevitablist catechism.

Squeezing the workers' wages conditions and weakening workers' bargaining power isn't "innovation." It's an old, old story, as old as the factory owners who replaced skilled workers with terrified orphans, sending out for more when a child fell into a machine. Then, as now, this was called "job creation."

Then, as now, there was no way to progress as a worker: no matter how skilled and diligent an Uber driver is, they can't buy their medallion and truly become their own boss, getting a say in their working conditions. They certainly can't hope to rise from a blue-collar job on the streets to a white-collar job in the Uber offices.

Then, as now, a worker was hired by the day, not by the year, and might find themselves with no work the next day, depending on the whim of a factory owner or an algorithm.

As Merchant writes: robots aren't coming for your job; bosses are. The dream of a "dark factory," a "fully automated" Tesla production line, is the dream of a boss who doesn't have to answer to workers, who can press a button and manifest their will, without negotiating with mere workers. The point isn't just to reduce the wage-bill for a finished good – it's to reduce the "friction" of having to care about others and take their needs into account.

Luddites are not – and have never been – anti-technology. Rather, they are pro-human, and see production as a means to an end: broadly shared prosperity. The automation project says it's about replacing humans with machines, but over and over again – in machine learning, in "contactless" delivery, in on-demand workforces – the goal is to turn humans into machines.

There is blood in the machine, Merchant tells us, whether its humans being torn apart by a machine, or humans being transformed into machines.

Brian and I are having a joint book-launch tomorrow night (Sept 27) at Chevalier's Books in Los Angeles for my new book The Internet Con and his new book, Blood in the Machine:

https://www.eventbrite.com/e/the-internet-con-by-cory-doctorow-blood-in-the-machine-by-brian-merchant-tickets-696349940417

If you'd like an essay-formatted version of this post to read or share, here's a link to it on pluralistic.net, my surveillance-free, ad-free, tracker-free blog:

https://pluralistic.net/2023/09/26/enochs-hammer/#thats-fronkonsteen

#pluralistic#books#reviews#brian merchant#luddism#automation#history#gift guide#steampunk#makers#tina#inevitablism#reverse centaurs#amazon#arise

548 notes

·

View notes

Text

Oh Globby. Using the picture from when he’s interviewing at Noodle Burger is really smart. ;)

i do not take constructive criticism

#reblog#big hero 6#bh6#bh6 the series#big hero six the series#big hero 6 the series#disney#disney xd#disney channel#alistair krei#ned ludd#supersonic stu#baymax#karmi#mr. sparkles#obake#trevor trengrove#globby#momakase#felony carl#juniper#go go tomago#hardlight#aunt cass#richardson mole#fred frederickson iv#wasabi no ginger

107 notes

·

View notes

Text

Xuexiao x 道德经 (Dao De Jing, the original Daoist text by 老子) Verse 31, as translated by Ned Ludd.

101 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cutting taut cloth with sharp scissors: "You know, I think the Luddites had some good ideas. There's something truly ennobling about the joy of manual labor."

Cutting loose cloth with dull scissors: "Once I finish this time machine, I am shooting Ned Ludd with a slow bullet."

42 notes

·

View notes