#National citizenship is not defined by assimilation

Text

"Writing Julian as spending time abroad and speaking other languages and being too culturally foreign is racist because it implies he's less British" yeah hey quick question: why do you think those things would make him less British

#Cipher talk#Sorry I'm in a cunty mood about that one person#The people I worked alongside who spoke little to no English were Americans by virtue of living in America.#National citizenship is not defined by assimilation#Like. Blegh#Would it be OOC to say Julian doesn't speak English at all? Possibly. He'd the type that I think /does/ prefer to read literature in its#Original language#But I really really would like to see these oh so horrible fics that are Doing a Racism in your opinion as a white#By giving a brown character connection to cultural aspects of him that were left untouched in the show outside of Augmentation#Because you cannot separate Khan Noonien Singh as this iconized figure of revulsion from how Julian exists#No one is denying Julian likes Bond or WW2 replays or Shakespeare. We're arguing he likes other things too.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Zainichi, which literally means “residing in Japan”, is the name given to ethnic Koreans who immigrated to Japan post-war.

Although Koreans in Japan prior to World War II suffered racial discrimination and economic exploitation, the Japanese authorities nonetheless counted ethnic Koreans as Japanese nationals and sought to fully assimilate Koreans into Japanese society through Japanese education and the promotion of intermarriage. Following the war, however, the Japanese government defined ethnic Koreans as foreigners, no longer recognizing them as Japanese nationals. The use of the term Zainichi, or "residing in Japan" reflected the overall expectation that Koreans were living in Japan on a temporary basis and would soon return to Korea. By December 1945, Koreans lost their voting rights. In 1947, the Alien Registration Law consigned ethnic Koreans to alien status. The 1950 Nationality Law stripped Zainichi children with Japanese mothers of their Japanese nationality; only children with Japanese fathers would be allowed to keep their Japanese citizenship.

Read more about Koreans in Japan:

#zainichi#korean#Japanese#japan#korea#post war Japan#discrimination#ethnic minority#immigration#immigrants#WWII#three resurrected drunkards#japanese film

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

I had someone tell me Ireland is an ethnostate, similar to Israel. Ireland is a nation-state: a state that is relatively homogeneous in factors such as language. Israel is an ethnostate: a state that de facto and/or de jure restricts citizenship to members of a certain racial, ethnic, or religious group. The two are not the same. Suggesting they are is nothing short of insulting.

Relative ethnic homogeneity within a state’s borders is *not* inherently a sign of an ethnostate because relative homogeneity within a state’s borders is *not* necessarily the result of ethnostate citizenship restrictions. It is possible for a state to have a very heterogeneous population within its borders and be an ethnostate. Because what defines an ethnostate is whether the state de facto and/or de jure restricts citizenship to members of a certain racial, ethnic, or religious group.

Ethnostate citizenship restrictions are also *not* inherently the result of a preexisting relative homogeneity within a state’s borders. There is absolutely a conversation to be had about the political, legal, economic, and social resources at a hegemonic group’s disposal to maintain its majority. One of those political and legal resources can be the establishment of an ethnostate. We can see this principle in action in the United States with right-wing calls to end jus soli. They know that ending jus soli and combining it with greater immigration restrictions is a more feasible way to achieve a homogeneous staatsvolk in the United States given that, by 2050, immigration will account for 71% of population growth and there will be no clear ethnic or racial majority within US borders. Legally restricting citizenship to members of a certain racial, ethnic, or religious group is the only way for the white, Christian majority to maintain itself, so it is publicly advocating for this to become a legal reality.

On the other side of the spectrum, the modern Yamato people comprise over 98% of Japan’s population. For decades, Japanese political leaders have stated that ethnic homogeneity is key to Japanese national identity, and Japan has a long history of racism toward the Ainu, the Ryukyuans, the Koreans, and the Vietnamese. Japanese governments have created programs encouraging a single, unified, monocultural Japanese identity. Many of these programs included the erasure, forced assimilation, and suppression of minority ethnic groups and multiethnic people. Japanese imperialism and racism have a long history of brutal violence and oppression. It is through violence and oppression that they have been able to maintain its hegemonic ethnic state. They do not need to utilize ethnostate citizenship policies for Japan to maintain its staatsvolk.

Israel had to build its staatsvolk from scratch, similarly to other settler-colonial nations like the US, Canada, Australia, and South Africa. Israelis did not exist before 1948. The state had to build its national subjects, national identity, and hegemonic groups from the outside - in rather than the inside - out (like, say, Japan). The Israeli State had to secure the primacy of Judaism, Hebrew, and Ashkenazi identity among secular life and government, and it did it through Zionism. Zionism’s political intention and goal was a demographic shift in Palestine. It wanted to make the minority Jewish population a majority through massive Jewish immigration and settlement building, as well as the expulsion of the native Palestinians. It has continued its settler-colonial project by codifying Jewish entitlement to citizenship while making citizenship to Israel incredibly difficult to obtain if you are non-Jewish. Israel legally, socially, and economically encourages the settlement and citizenship of Jewish people while legally, socially, and economically discouraging the settlement and citizenship of non-Jewish people. Israeli law states that national self-determination is unique to Jewish people, establishes Hebrew as Israel’s official language, establishes Jewish settlement and citizenship as a national value, and calls Israel the “national home of the Jewish People.” There is no promise of political or legal equality for Palestinians and non-Jews in Israel as they are relegated to separate legal, political, public, and health systems.

Israel is an ethnoreligious state.

youtube

40 notes

·

View notes

Note

Here’ss a question I have in regards to an ethno-religion, is it possible to leave in any way?

Like, if someone was born to Jewish parents, but was adopted shortly after being born, was raised without any of the practices, no contact with the culture whatsoever, are they still considered Jewish?

To a white supremacist? yes, definitely, but if Judaism is a religion, an ethnicity and a culture, then can one be ethnically Jewish without being culturally or religiously Jewish?

Like OP said I think it’s more a question of how these two groups define religion. Which, to be fair, “religion” is rather difficult to define.

So, yes, someone can be ethnically Jewish without being observant. Someone who is ethnically Jewish but doesn't observe the religion is what we call an ethnic Jew.

Adoption is an iffier subject, and often people adopted out at young ages to gentile families are told to speak with a Rabbi about determining what they want or need to do.

Now, let's say someone was raised by assimilated parents and know nothing of Jewish traditions or cultures, that we would usually refer to as someone having Jewish heritage. Again, someone with Jewish heritage could choose to be Jewish themselves or not to be. Their children or their children's children, on the other hand, would most likely not be Jewish. We tend to call people like that as having Jewish ancestry.

And all of this is of course separate from leaving Judaism as a religion. People can choose to leave Judaism to follow other gods and join other religions. Everyone has that right.

There are mixed thoughts to whether you can be Jewish if you leave the Jewish religion. I happen to think that, yes, you can. But then your children are not themselves automatically Jewish, because they were born outside the covenant and were not raised in a Jewish home by Jewish children. This last point though, has many points of views and perspectives by different Jews.

Essentially, it helps to think of all of it as akin to nationality. People can "naturalize" by converting to Judaism. People can leave Judaism but keep their "citizenship" as they live in a different religion/nationality. But because they left, their children instead have "citizenship" of the country where they were born, and need to actively affirm any Jewish affiliation. If that metaphor makes sense?

And then, all of this is separate again to the main point, which has less to do with religion itself. The original conversation has to do with the frameworks people were taught to view the world and themselves vis a vis the world.

This is part of why I find that term unhelpful. It doesn't actually have to do with religion at all really. It has to do with the communities, cultures, teachings and peoples that have been coupled with the religion.

6 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hyphenated Americans should be deported. Oh you're irish-american? Chinese-american? Get out of here and come back when you're ready to be 100% American

two things.

first, in a sense, i agree with this. americans need to stop doing this. they need to just embrace being americans. it's fine to appreciate your heritage -- in fact, i think it's important -- but it shouldn't be your defining identity. so either assimilate or leave. embrace being american. cast away the old world and take your place among the greatest civilization to ever exist.

also, join my cult and our project of renewed american ethnogenesis.

second, in a sense, i think there is some room for this kind of identification. specifically for new immigrants. this is getting into the complexities of ethnicity which i won't go too in depth about right now. but i don't think that you can be fully integrated into a nation just by moving there. a white man moving to china doesn't make him chinese. he is a white man who lives in china. he may have chinese citizenship in which case he's a chinese national/citizen but he's not /ethnically/ chinese. likewise a chinese person who immigrates here doesn't magically become ethnically american. so it would be a bit weird for him to say he's american. but i think chinese-american would be acceptable until he is assimilated. so he's ethnically chinese but an american citizen.

i think that's fair.

but yeah, if your ancestors came from ireland 150 years ago and you're still calling yourself irish-american it's kinda cringe bro. just say you're american with irish heritage. it'll be okay.

2 notes

·

View notes

Link

Once citizenship was equated with human dignity, its extension to all classes, professions, both sexes, all races, creeds, and locations was only a matter of time. Universal franchise, the national service, and state education for all had to follow. Moreover, once all human beings were supposed to be able to accede to the high rank of a citizen, national solidarity within the newly egalitarian political community demanded the relief of the estate of Man, a dignified material existence for all, and the eradication of the remnants of personal servitude. The state, putatively representing everybody, was prevailed upon to grant not only a modicum of wealth for most people, but also a minimum of leisure, once the exclusive temporal fief of gentlemen only, in order to enable us all to play and enjoy the benefits of culture.

For the liberal, social-democratic, and other assorted progressive heirs of the Enlightenment, then, progress meant universal citizenship—that is, a virtual equality of political condition, a virtually equal say for all in the common affairs of any given community—together with a social condition and a model of rationality that could make it possible. For some, socialism seemed to be the straightforward continuation and enlargement of the Enlightenment project; for some, like Karl Marx, the completion of the project required a revolution (doing away with the appropriation of surplus value and an end to the social division of labor). But for all of them it appeared fairly obvious that the merger of the human and the political condition was, simply, moral necessity.2

The savage nineteenth-century condemnations of bourgeois society—the common basis, for a time, of the culturally avant-garde and politically radical—stemmed from the conviction that the process, as it was, was fraudulent, and that individual liberty was not all it was cracked up to be, but not from the view, represented only by a few solitary figures, that the endeavor was worthless. It was not only Nietzsche and Dostoevsky who feared that increasing equality might transform everybody above and under the middle classes into bourgeois philistines. Progressive revolutionaries, too, wanted a New Man and a New Woman, bereft of the inner demons of repression and domination: a civic community that was at the same time the human community needed a new morality grounded in respect for the hitherto excluded.

This adventure ended in the debacle of 1914. Fascism offered the most determined response to the collapse of the Enlightenment, especially of democratic socialism and progressive social reform. Fascism, on the whole, was not conservative, even if it was counter-revolutionary: it did not re-establish hereditary aristocracy or the monarchy, despite some romantic-reactionary verbiage. But it was able to undo the key regulative (or liminal) notion of modern society, that of universal citizenship. By then, governments were thought to represent and protect everybody. National or state borders defined the difference between friend and foe; foreigners could be foes, fellow citizens could not. Pace Carl Schmitt, the legal theorist of fascism and the political theologian of the Third Reich, the sovereign could not simply decide by fiat who would be friend and who would be foe. But Schmitt was right on one fundamental point: the idea of universal citizenship contains an inherent contradiction in that the dominant institution of modern society, the nation-state, is both a universalistic and a parochial (since territorial) institution. Liberal nationalism, unlike ethnicism and fascism, is limited—if you wish, tempered—universalism. Fascism put an end to this shilly-shallying: the sovereign was judge of who does and does not belong to the civic community, and citizenship became a function of his (or its) trenchant decree.

[...]

The perilous differentiation between citizen and non-citizen is not, of course, a fascist invention. As Michael Mann points out in a pathbreaking study3, the classical expression "we the People" did not include black slaves and "red Indians" (Native Americans), and the ethnic, regional, class, and denominational definitions of "the people" have led to genocide both "out there" (in settler colonies) and within nation states (see the Armenian massacre perpetrated by modernizing Turkish nationalists) under democratic, semi-democratic, or authoritarian (but not "totalitarian") governments. If sovereignty is vested in the people, the territorial or demographic definition of what and who the people are becomes decisive. Moreover, the withdrawal of legitimacy from state socialist (communist) and revolutionary nationalist ("Third World") regimes with their mock-Enlightenment definitions of nationhood left only racial, ethnic, and confessional (or denominational) bases for a legitimate claim or title for "state-formation" (as in Yugoslavia, Czecho-Slovakia, the ex-Soviet Union, Ethiopia-Eritrea, Sudan, etc.)

Everywhere, then, from Lithuania to California, immigrant and even autochthonous minorities have become the enemy and are expected to put up with the diminution and suspension of their civic and human rights. The propensity of the European Union to weaken the nation-state and strengthen regionalism (which, by extension, might prop up the power of the center at Brussels and Strasbourg) manages to ethnicize rivalry and territorial inequality (see Northern vs. Southern Italy, Catalonia vs. Andalusia, English South East vs. Scotland, Fleming vs. Walloon Belgium, Brittany vs. Normandy). Class conflict, too, is being ethnicized and racialized, between the established and secure working class and lower middle class of the metropolis and the new immigrant of the periphery, also construed as a problem of security and crime.4 Hungarian and Serbian ethnicists pretend that the nation is wherever persons of Hungarian or Serbian origin happen to live, regardless of their citizenship, with the corollary that citizens of their nation-state who are ethnically, racially, denominationally, or culturally "alien" do not really belong to the nation.

The growing de-politicization of the concept of a nation (the shift to a cultural definition) leads to the acceptance of discrimination as "natural." This is the discourse the right intones quite openly in the parliaments and street rallies in eastern and Central Europe, in Asia, and, increasingly, in "the West." It cannot be denied that attacks against egalitarian welfare systems and affirmative action techniques everywhere have a dark racial undertone, accompanied by racist police brutality and vigilantism in many places. The link, once regarded as necessary and logical, between citizenship, equality, and territory may disappear in what the theorist of the Third Way, the formerly Marxissant sociologist Anthony Giddens, calls a society of responsible risk-takers.

[...]

Citizenship in a functional nation-state is the one safe meal ticket in the contemporary world. But such citizenship is now a privilege of the very few. The Enlightenment assimilation of citizenship to the necessary and "natural" political condition of all human beings has been reversed. Citizenship was once upon a time a privilege within nations. It is now a privilege to most persons in some nations. Citizenship is today the very exceptional privilege of the inhabitants of flourishing capitalist nation-states, while the majority of the world’s population cannot even begin to aspire to the civic condition, and has also lost the relative security of pre-state (tribe, kinship) protection.

The scission of citizenship and sub-political humanity is now complete, the work of Enlightenment irretrievably lost. Post-fascism does not need to put non-citizens into freight trains to take them into death; instead, it need only prevent the new non-citizens from boarding any trains that might take them into the happy world of overflowing rubbish bins that could feed them. Post-fascist movements everywhere, but especially in Europe, are anti-immigration movements, grounded in the "homogeneous" world-view of productive usefulness. They are not simply protecting racial and class privileges within the nation-state (although they are doing that, too) but protecting universal citizenship within the rich nation-state against the virtual-universal citizenship of all human beings, regardless of geography, language, race, denomination, and habits. The current notion of "human rights" might defend people from the lawlessness of tyrants, but it is no defense against the lawlessness of no rule.

Believe I posted this before but it’s interesting enough to post again

142 notes

·

View notes

Text

6 Key Concepts about Race or Racism

youtube

1) Ethnic cleansing - Ethnic cleansing, the attempt to create ethnically homogeneous geographic areas through the deportation or forcible displacement of persons belonging to particular ethnic groups. On May 14, 1948, the State of Israel was created, sparking the first Arab-Israeli War. The war ended in 1949 with Israel's victory, but 750,000 Palestinians were displaced and the territory was divided into 3 parts: the State of Israel, the West Bank (of the Jordan River), and the Gaza Strip. Between 1947 and 1949, over 400 Palestinian villages were deliberately destroyed, civilians were massacred and around a million men, women, and children were expelled from their homes at gunpoint. The creation of Israel caused conflict because Jewish people moved into the Muslim land. The Palestinians living in Israel dislike Israeli rule. Around the early 1990s, Israel agreed to give Palestinians control of an area called the Gaza strip and the town of Jericho.

youtube

2) Citizenship - Citizenship is the relationship between an individual and a state to which the individual owes allegiance and in turn is entitled to its protection. Citizenship implies the status of freedom with accompanying responsibilities. Citizens have certain rights, duties, and responsibilities that are denied or only partially extended to aliens and other noncitizens residing in a country. In general, full political rights, including the right to vote and to hold public office, are predicated upon citizenship. The usual responsibilities of citizenship are allegiance, taxation, and military service.

3) Genocide - The United Nations Genocide Convention defines genocide as an internationally recognised crime where acts are committed with the intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial, or religious group. These include killing members of a group, causing serious bodily or mental harm to the members of a group, deliberately inflicting of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part, imposing measures to prevent birth within a group or forcibly transferring children of a group to some other group.The most extreme extermination campaign against a people was the Holocaust or the genocidal `Final Solution' ordered by Adolf Hitlerduring the holocaust, before or at the latest by autumn 1941 and continuing into May 1945. Reliable estimates of the number of Jews killed range from 5.1 to 6 million. In addition, the Nazis routinely killed three million Soviet prisoners of war, two million Poles and 400,000 other 'undesirables'.

youtube

4) Assimilation - Assimilation is the process whereby individuals or groups of differing ethnic heritage are absorbed into the dominant culture of a society. The process of assimilating involves taking on the traits of the dominant culture to such a degree that the assimilating group becomes socially indistinguishable from other members of the society. As such, assimilation is the most extreme form of acculturation. Although assimilation may be compelled through force or undertaken voluntarily, it is rare for a minority group to replace its previous cultural practices completely; religion, food preferences, proxemics, and aesthetics are among the characteristics that tend to be most resistant to change. An example of this is the physical distance between people in a given social situation.

5) Diaspora - A diaspora is a large group of people with a similar heritage or homeland who have since moved out to places all over the world. It is the dispersion or spreading of something that was originally localized (as a people or language or culture). Diaspora describes people who have left their home country, usually involuntarily to foreign countries around the world. Examples of these communities include the removal of Jewish people from Judea, the removal of Africans through slavery, and most recently the migration, exile, and refugees of Syrians. The image shows the removal of Africans through slavery.

youtube

6) Nationality - Nationality is the status of belonging to a particular nation by birth or naturalization. A person's nationality is where they are a legal citizen, usually in the country where they were born and raised. People from Mexico have Mexican nationality, and people from Australia have Australian nationality. People of the same nationality usually share traditions and customs, and they might look a little alike, too. Nationality is one of many qualities that bring people together.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

EXCLUSIVE: Chief of Border Patrol Bucks Biden, Will Say ‘Alien’ Until Law Changes

A law enforcement source, speaking on a condition of anonymity, provided Breitbart Texas with a memorandum authored by Rodney S. Scott, Chief of the United States Border Patrol. In the April memo, Scott advises Acting Customs and Border Protection Commissioner Troy Miller that he cannot endorse a new communications and vocabulary policy set in motion by the Biden Administration.

The policy change requires Customs and Border Protection and Immigration and Customs Enforcement personnel to refrain from the use of the terms “alien, unaccompanied alien children, undocumented alien, illegal alien, and assimilation” in internal and external communications. The terms must be substituted with “non-citizen, non-citizen unaccompanied children, undocumented non-citizen, and civic integration.” The policy went into effect on April 19.

Chief Scott’s memorandum recommends waiting for the enactment of United States Citizenship Act of 2021 which would remove the prohibited terminology from the Immigration and Nationality Act. Under current immigration law, the term “alien” is legally defined as a foreign national present in the United States.

Chief Scott states in his memorandum that he would not undermine the effort to implement and enforce the new policy but had reservations about politicizing his agency. He explains his rationale:

The U.S. Border Patrol (USBP) is and must remain an apolitical federal law enforcement agency. Over the years, many outside forces on both extremes of the political spectrum have intentionally, or unintentionally politicized our agency and our mission. Despite every attempt by USBP leadership to ensure that all official messaging remained consistent with law, fact, and evidence, there is no doubt that the reputation of the USBP has suffered because of the many outside voices. Mandating the use of terms which are inconsistent with law has the potential to further erode public trust in our government institutions.

Despite Scott’s objection, the policy was ultimately put in place and remains in effect. It will not, however, impact official reports and legal documents that must contain the terms codified in the Immigration and Nationality Act.

Randy Clark is a 32-year veteran of the United States Border Patrol. Prior to his retirement, he served as the Division Chief for Law Enforcement Operations, directing operations for nine Border Patrol Stations within the Del Rio, Texas, Sector. Follow him on Twitter @RandyClarkBBTX.

READ MORE STORIES ABOUT:

Border / Cartel Chronicles PoliticsPre-Viral immigration On the Hill

_____________________________________

OPINION: President Joe Biden is turning our country into a ‘sh*t hole of a country. Everything Democrats touch turns our country into the worst possible situation before they (i.e, took office).

Its a shame! However, our country have plenty of documentation over the years when each Democrats has taken office and the picture is not good at all.

Joe Biden, unfortunately is weak and is not a strong leader of the United States of America. (i.e, as we may not recognize it after he leave office). It a dare shame that we are taken back instead of moving forward.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Gijsbert Oonk, Sport and nationality: towards thick and thin forms of citizenship, National Identities 1 (Epub ahead of print, 2020)

Abstract

This study explores the relationship between national belonging, acquiring citizenship, and migration. Taking high profile examples from international sports events, it seeks to unveil the complexities behind the question: who may represent the nation? The historical models of jus sanguine (blood ties) and jus soli (territorial birthright) are well-known markers and symbols of citizenship and nationality. The study proposes an ideal-type model of thick, thin, and in-between forms of citizenship. This model clarifies and provides direction to the empirical understanding of ‘citizenship as claims-making’, as recently suggested by Bloemraad [(2018). Theorising the power of citizenship as claims-making.

Introduction

In the international sports arena, the legal guidelines and the moral justifications for citizenship and national belonging are stretched. This stretching can be perceived as a global continuum where, on the one hand, there is an ideal type – thick – citizenship, whereby an athlete and their parents, and/or grandparents are born and raised in the country that they represent. In these cases, the athlete holds the citizenship of the country they represent, and their legal status, as well as the moral justifications for representing a country, are not under scrutiny. This seems to be self-evident. On the other hand, the thin description of citizenship defines conditions in which an athlete has no prior relationship with the country they represent. For example, this was the case when Russia offered Korean born-and-raised Viktor Ahn citizenship and a sum of money in return for his willingness to represent Russia in the Olympics (Business Insider, 2014). Between thick and thin descriptions of citizenship, this study outlines an in between perspective where dual or multiple forms of citizenship emerge. This in between perspective provides options for athletes to represent more than one country. The proposed model of thick, thin, and in-between citizenship aims to clarify and provide meaning to the empirical understanding of ‘citizenship as claims-making’, as recently suggested by Bloemraad (2018).

This model helps us to understand three recent developments of acquiring citizenship in the history of global sports: (1) Acknowledge that the current global regimes for acquiring citizenship at birth inevitably create dual, or multiple forms of citizenship. Therefore, countries and national sports federations need to accept that dual citizens are legitimately legal members of more than one country, and they may wish to switch alliances. (2) People of former colonies may acquire citizenship by claiming colonial ties as part of their national identity and may, therefore, switch alliances. (3) Countries such as the U.S. and Canada historically attract migrants, and thus, it is not surprising that they use special scholarships and sports schemes to attract athletes who may eventually represent them though they had no prior attachments. In extreme cases, such as Qatar and Bahrain, most inhabitants are migrants. Here, the use of migrant-athletes in representing these countries is in line with the overall migration strategy of empowering these respective countries. These countries increasingly accept the thin description of citizenship to have their countries represented in international sports arenas. 1

In general, the historical process of acquiring modern citizenship has taken two different paths: territorial birthright and descent. This is best illustrated in the remarkable and ground-breaking study by Brubaker (1998), who points out that the two primary concepts determining French and German national self-understanding are the civic and ethnic approaches to membership of a nation formed in the 18th and 19th centuries. The French understanding of citizenship and nationhood was based on birthright and was inclusive. Everyone born on French territory was French or – in the case of parents with different nationalities – could become French. The French tended to define their country as a political unit. The major question was – who would enjoy political rights? It was not – what makes us French? However, the German understanding of citizenship and nationhood was based on descent, was ethnocultural, and therefore exclusive. Blood, ancestry and Volksgeist created the nation. Similar to the French example, the development of American citizenship was based on territorial birthright. Kettner (1978) shows that the debates in the early nineteenth century established the terms under which immigrants could become American citizens:

Theoretical coherence and logical consistency were not the primary goals here, especially for legislatures and executive officers. Rather, in dealing with problems involving citizenship – problems of naturalisation, expatriation and court jurisdiction – the chief aim was to maintain an acceptable pattern of federal relations. (p. 248).

However, this pragmatic approach also included the right to exclude Native Americans and (former) enslaved people. In short, bloodline and territorial birthright were powerful tools to both include and exclude citizenship, and therefore, citizenship rights.

What German, French and American histories share is that they describe the magnitude of the Westphalian transformation in1848, from non-territorial membership (when people were the subjects of kings) to territorial membership, where people became members of sovereign states. This membership is based on duties and political rights, which have evolved into universal rights for all members of most states, such as freedom of speech, equality, and well-being. Simultaneously, it is assumed that the state fulfils its functions best if its members are not only individuals with their social contracts but also share general values, language, and history. This is perceived as the result of unifying processes such as the shift from primarily agricultural to industrialised societies (Gellner, 1992). Similarly, the emergence of an ‘imagined community’ (Anderson, 1991) was the result of the successful promotion of national identity, the education of children in national history, promotion of a common language, and the emergence of a ‘national press’ (Anderson, 1991; Hobsbawm, 1992). Associated with these processes are the distinction between ‘civic’ and ‘ethnic’ types of nations and nationalism, and the idea that all nations have dominant ‘ethnic cores’ (Smith, 1991). On the one hand, there is the successful transformation of peasants to Frenchmen as described by Weber (1976), whereas on the other hand, Gans (2017) describes how Britain assimilated the Welsh people, while excluding Jews and Catholics from full citizenship.

New forms of citizenship regimes

New forms of citizenship regimes and belonging emerged in the post-colonial world, especially in the Middle East and Asia. Countries like Singapore, Qatar and the United Arab Emirates realised that bringing in multinationals and foreign direct investment were not sufficient to prosper. Attracting people with skills and knowledge therefore became a key strategy for national development. This included promoting attractive citizenship processes and tax regimes for wealthy and talented foreign individuals, with more sober regimes for labourers. Singapore, for example, introduced a points system where education and professional qualifications are rated so that skilled migrants can easily obtain permanent residency depending on their rating, skills and income (Ong, 1999, p. 186). Attracting skilled and wealthy foreigners is not unique to the East. It also occurs in many Western countries, including the U.S. and Canada. What is different, however, is the scale of migration. In Singapore, around one-fifth of the total population belongs to the highly educated migrant community. In Dubai and Qatar, more than 80% of inhabitants are migrants (Vora, 2013). Some are poor and worked as labourers building the stadiums for the Qatar 2022 World Cup, while others had the sought-after skills to represent Qatar in international sports events.

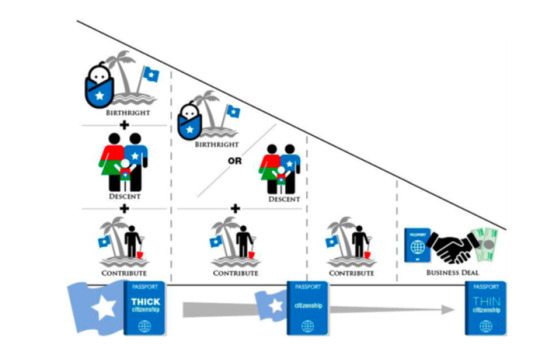

In short, currently, there are three interrelated ways of obtaining citizenship: (1) citizenship acquired through descent (jus sanguinis). This form is the kind of citizenship prevalent in, for example Germany until 1999. If one, or both of your parents were German, you were eligible for German citizenship. In this way, many Eastern European Germans maintained access to German citizenship status during the Cold War. (2) Citizenship by birth in the territory (jus soli). This form of citizenship was made famous by the U.S. American citizenship is granted automatically to any person born within and subject to the jurisdiction of the U.S. (3) The stakeholder principle (jus nexi) is proposed as an alternative (or a supplement) to birthright citizenship. Individuals who have a ‘real and effective link’ (Shachar, 2009, p. 165) to the political community, or a ‘permanent interest in membership’ (Bauböck, 2006) are entitled to claim citizenship. This relatively new criterion aims at securing citizenship for those who are members of the political community, in the sense that their life prospects depend on the country’s laws and policy choices. This often applies to migrants who work and live in a country for a specific number of years (often five to seven). They are regarded as new members of society who have acquired skills (they work and pay taxes), and can become politically active and thus contribute to the state (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Thick and thin forms of citizenship.

However, there are some counter-intuitive results of the distinction between jus sanguinis and jus soli: while a regime of pure jus sanguinis systematically excludes immigrants and their children, though the latter may have been born and raised in their parents’ new homeland, it includes the descendants of expatriates who might never have set foot in the homeland of their forebears. On the other hand, a regime of jus soli might attribute citizenship to children whose birth in the territory is accidental, while denying it to children who arrived in the country at a young age. It is important to understand that the current rules for acquiring citizenship at birth inevitably create multiple citizenships. Dual nationality merges at birth in two cases: first, in the gender-neutral system of jus sanguinis, where children of mixed parentage inherit both parents’ nationalities, and second, from a combination of jus soli and jus sanguinis. Multiple citizenships could only be avoided if all states adopted either pure jus soli or jus sanguinis from one parent’s side. However, gender discrimination in citizenship has been outlawed by norms of international and domestic law, and countries that apply jus soli within their territory mostly attribute citizenship jus sanguinis to children born to their citizens abroad. Given these facts, there is no possible rule that could be adopted by all states to avoid multiple forms of citizenship. In other words, through existing membership regimes, there is always scope for athletes and states to represent two or more states. Dutch national footballer Jonathan de Guzman, for example, could have played for Jamaica (maternal ancestry), the Philippines (paternal ancestry), Canada (where he was born), or the Netherlands (where he started his career and was eligible to play after naturalisation). His brother Julian represents Canada. In other words, as an extremely talented midfielder, he was able to negotiate between the Dutch and Canadian national football federations. His citizenship capital (a form of cultural capital) was such that he could claim to play for four different countries at the international level. By the same token, there were four national football federations that could compete for his talents. In this case, de Guzman chose to play for the Netherlands – most likely because his chances of winning a World Cup medal were highest there as the Dutch national football team was ranked higher than the other three options. In this respect, the agency of citizens and non-citizens takes centre stage rather than state policies (Bloemraad, 2018; Jansen et al., 2018). Thus, this study seeks to discuss ‘citizenship as membership through claims-making’ from an empirical perspective (Bloemraad, 2018). Bloemraad (2018) attempts to understand citizenship from a relational approach within the context of structured agency. She takes a bottom-up approach, emphasising the perspective of migrants in the context of ‘citizenship’s power as practice and status’ to elucidate, ‘how status, rights, participation and identity can at times be interwoven and reinforcing’ (Bloemraad, p. 4).

The matter of civic and ethnic citizenship rights merges here forming the question: who may represent the country in international sports events? International athletes represent a country. They wear the colours of that country. They sing the national anthem, and they watch the national flag being raised if they win a medal. In other words, how do athletes acquire citizenship? The answer might not surprise us. In general, they acquire citizenship the same way most of us do, by birth (territorial or descent). However, as this article shows, for some athletes, the stakes in negotiating the scope for acquiring citizenship for one country or another are high.

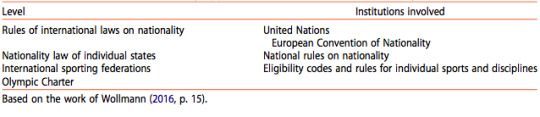

Table 1. Levels of rules in nationality applications within the International Olympics Committee.

Thick and thin forms of citizenship

In this model, I define thick citizenship where territorial birthright, descent, and contribution merge. Most athletes and their parents are born in the countries they represent. These athletes have acquired their skills in that country and are more than willing to wear national colours and win medals for national teams. Unsurprisingly, the Sport and Nation group at the Erasmus University in the Netherlands found that more than 90% of all athletes who represented their country in the summer Olympic Games from 1948–2016 fell within this category (Campenhout et al., 2018; Jansen et al., 2018; Jansen & Engbersen, 2017).

Thin citizenship, however, occurs in cases when migrants or athletes do not have any relationship with the country they represented before the citizenship transfer in exchange for money. This is illustrated by the current debates on national belonging and citizenship changes in the Olympics (Shachar, 2011; Spiro, 2011). Some countries (including the U.S., Canada, and most Western European countries) have advanced an entrepreneurial attitude towards elite labour; they have developed specific citizenship tracks for foreigners. However, extreme examples relating to participation in the Olympics have emerged from countries such as Azerbaijan, Qatar, Singapore, Bahrain, and Turkey. These countries have actively attracted foreign athletes to represent them internationally. In the cases of Qatar, Bahrain, and Singapore, this can be perceived as part of a wider strategy to attract foreign talent. For Turkey and Azerbaijan, it is a form of self-promotion. 2Between thick and thin citizenship, this study locates mixed, or in-between forms of citizenship where athletes only share a connection through two of three citizenship qualifications: jus soli, jus sanguins, or jus nexi. Additionally, in some cases, the prior relationship through jus sanguinis and jus soli is distorted by external territorial (colonial) expansion, as well as mixed ancestral backgrounds. Further, this category includes cases where the connection is made through contribution, earned citizenship, and jus nexi, without prior relation through territorial birthright or descent. Overall, the major contribution of this study is to highlight some of the complexities of the ‘in between’ category, an area that has yet to receive sufficient attention.

This ideal model of thick and thin perspective stresses the formal relation – ‘the social contract’, between the individual and the state. Therefore, this model hides some of the complexities of nationality and national belonging. In Britain, for example, citizens may carry a British passport, whether their national identity is Scots, Welsh, Irish, or Cornish. In Spain, people may have a Spanish passport, but they may identify more with Catalonian or Basque nationalities. In these cases, the terms of the social contract of a Welsh and Scottish person are analogous, but the two persons may identify with different nationalities. Thus, the answer to the question: who may represent the country, becomes multifaceted. Scottish football players are unlikely to represent the Welsh national football team in an official match and vice versa. Nevertheless, as the international governing body of association football, the Fédération Internationale de Football Association (FIFA) and the International Olympic Committee handle different sets of rules regarding their recognition of citizenship, it may well happen that the same Scottish and Welsh football players represent Team Britain during the Olympic Games against another country (Ewen, 2012).

Sport, migration and identity

Research on sports labour migration began almost three decades ago with the pioneering work of Bale and Maguire (Bale, 1991; Bale & Maguire, 1994). In the development of a political economy of sport, labour migration and nationhood international sports migrants should be considered in the context of the realities of leaving native lands and adapting to foreign environments. Most cases examined came from countries in the Global North and South America. However, these were soon supplemented with cases of football players from Africa who went to Europe, and East African athletes who went to the Middle East (Bale, 2004; Carter, 2011; Darby, 2000, 2002, 2007; Lanfranchi & Taylor, 2001; Poli, 2006, 2010). Most of this research is primarily focused on male athletes. Agergaard and Engh have recently complemented existent literature with female migrant players, focusing on routes between African (Nigerian) and Scandinavian football clubs (Engh et al., 2017) as well as global perspectives (Agergaard & Tiesler, 2014). Recently, Besnier, Brownell, and Carter have taken up the challenge to write an anthropological perspective of sport, including issues of class, race, gender, and migration (2018). While these studies include questions of migration, cultural adaptation, legal process of visa, citizenship, and the political economy of globally skilled (athlete) labour, they scarcely focus on the extraordinary cases of migrant athletes who represent a country at the FIFA World Cup, or at the Olympics (Guschwan, 2014). The study argues that representing a country where you were not born often involves a different set of legal requirements (e.g. the acquisition of citizenship), adaptions (sometimes minimal), and national identification, whether imagined or not. For an excellent overview of the complexities of the nationality requirements of Olympic sports see the recent work of Wollmann (2016). She clearly shows that states, as well as international and national sport federations, may set different rules and regulations of eligibility. This study shows how athletes navigate within those institutions (Table 1).

Overall, most cases and examples studied here come from the Olympics and the Men’s World Cup, which are arguably the most watched global sporting events. The 2016 Olympic Games were broadcast in over 200 participating countries with a worldwide audience of five billion people. Despite the fact that the number of participating countries in the World Cup was limited to 32 in 2018, the final match was watched by 3.5 billion people. The increased mediatisation of those events over the past decades makes nationality switches in these global sport events major national, and sometimes international high-profile matters (Giulianotti, 2015). In these contexts, sport can serve as a ‘prism […] uniquely well suited to an examination of national identity’ (Holmes & Storey, 2011, p. 253). In addition, the historian Eric Hobsbawn is often quoted as saying, ‘The Imagined Community of Millions seems more real as a team of eleven named people. The individual, even the one who only cheers, becomes a symbol of his nation himself’ (Hobsbawm, 1992, p. 143).

In the following sections I describe the three citizenship categories in more detail. This includes the presentation of empirical case studies to determine the scope for negotiating between states and athletes in each of these categories. Not surprisingly, the first category of thick citizenship does not leave much room for negotiating. Athletes, as well as states and sport-institutions, do not find much room for switching alliances because of legal and institutional constraints. The second, ‘in-between’ category is where shifting alliances and making instrumental choices to compete for country A or B has come to the forefront of the debate. Regulations on dual citizenship, colonial heritage, and jus nexi all contribute to the flexibility of athletes, sports institutions, and states. It is here that I propose to merge Bloemraad’s plea (2018) to study citizenship as a form of claims-making with Bourdieu’s theory of social fields, i.e. where a relatively autonomous network of agents is able to use its social citizenship capital (a combination of jus soli, jus sanguinis and jus nexi included in colonial and post-colonial senses of belonging) to navigate belonging and the right to participate in international sports. In the third category of thin citizenship, the room for negotiating is extended to the maximum. No prior-relationship is needed. It is simply citizenship in return for cash.

The thick, or ideal type of citizenship

National pride takes centre stage in international competitions, such as the Olympics and the FIFA World Cup. The number of medals won per country is regarded as an indication of the country’s (economic or military) prowess and reputation. Olympic athletes and the players on national football teams often become symbols of national pride and prestige. They sing the national anthem before matches, or after they have won an Olympic medal. These athletes display their medals and trophies with pride upon return from international competitions. More often than not, the success of these athletes is perceived as the success of the nation. The head of state typically invites successful athletes and teams to their official residence and honours them with awards or other decorations. It is not uncommon to see images of athletes or national audiences during the celebrations of great success with tears in their eyes.

Most athletes who represent their country are born and raised in the country they represent. More often than not, their parents and/or grandparents were also born there. Here, the ideal types of jus soli, jus sanguinis, and jus nexi merge. Each state can have its national hero, and this study considers Dirk Kuyt as one typical example. Both he and his parents were born in the Netherlands. He played for the Dutch football team (Feyenoord) before moving to Liverpool and Fenerbache. He played the semi-final match of the World Cup in 2010 and the final match in 2014. Others may opt for Michael Phelps, an American swimmer and the most decorated Olympian of all time. He was born in the U.S., as were both his parents. His American citizenship is not in dispute, nor is his American identity. What these cases have in common is that the citizenship status of the athletes is not disputed, from a legal, cultural, or normative perspective. Their citizenship status is – supposedly – self-evident.

Between thick and thin forms of citizenship

A little below the surface, some counterintuitive examples emerge where the relationship to jus sanguinis and jus soli is distorted. In fact – as already mentioned – the present rules for acquiring citizenship at birth inevitably create the possibility for multiple citizenships. A child born in country Z of a father born in country X and a mother born in country Y may be eligible to represent three countries. This increases the scope for negotiating national identity. This section presents three areas with scope for negotiating citizenship, identity, and belonging. First, there are examples of dual and multiple citizenships. Second, some countries use (and have used) their colonial ties to stretch the idea of territorial citizenship, while various forms of multiple citizenships and the stretching of colonial belonging might also merge. Third, cases where migrants – or their ancestors – claim jus nexi, or citizenship based on permanent interest in membership are discussed.

Dual and multiple citizenships

Julian Green was born in the U.S. His father was American, and his mother was German. As a toddler, he moved with his mother to Germany where she raised him. His American father served in the U.S. military and travelled back and forth. Julian had one brother, Jerry, who was born in Germany. Julian became a talented football player and played for Bayern Munich. At the age of 18, he acquired German citizenship (mother’s descent) and American citizenship (through father’s descent and territorial birthright). He was selected for the American national team and was also eligible to play for the German team. He spoke no English prior to his selection and had rarely visited the U.S. He was just one of the five German-Americans in the 2014 U.S. team. There were also foreign-born players, such as an Icelandic-American and a Norwegian-American, in addition to players of Colombian, Mexican and Haitian descent. All in all, 10 of 23 players, or 48% of the team were foreign-born. Manager Jürgen Klinsmann was said to have made the team his own by aggressively recruiting ‘dual nationals’ (players with dual citizenship). According to Klinsmann, however, this ‘reflects the culture of a country’. Nevertheless, America-born goalkeeper Tim Howard stated in USA Today that, ‘Jürgen Klinsmann had a project to unearth talent around the world that had American roots. But having American roots doesn’t mean you are passionate about playing for that country’. 3Some Americans have questioned the logic behind allowing dual citizens to represent Team USA in Brazil, while domestic players, such as former team captain Landon Donovan, were left off the roster. What is important in this context is that Klinsmann, Howard, and Donovan negotiated stretching dual citizenship and national belonging to a larger national and global audience, from their own instrumental perspectives.

In 2013, the talented football player Adnan Januzaj hit the headlines when journalists revealed that he was eligible to play for six different countries. He was born and raised in Belgium. He qualifies to play for Albania through his Kosovan-Albanian parents. His parents are of Kosovan-Albanian descent, but Kosovo’s national teams are not members of the Union of European Football Associations (UEFA) or FIFA. As Kosovo’s independence is also not recognised by the United Nations, he could play for Serbia. He also qualifies to play for Turkey through his grandparents. Finally, as he played for Manchester United at an early stage of his career, he could have acquired the right to play for England after five years. 4He ultimately chose to play for Belgium. 5Earlier, the former president of UEFA, Lennart Johansson, emphasised in similar cases that UEFA needed to preserve ‘traditional values such as pride in the jersey, national and regional identity (…) that are not financially related’ (Poli, 2007, p. 650).

Foreign-born: colonial pasts and post-colonial realities

Colonial ties and ideals of citizenship and belonging were negotiated during the colonial era. An interesting figure who complicates the exclusivity of the jus soli and jus sanguis forms of belonging in the colonial context is Norman Pritchard (1875–1929). He was born in Calcutta, the son of English parents and was baptised through the Senior Marriage Registrar in Calcutta in 1883. Historian and journalist Gulu Ezekiel claims that Pritchard was Indian based on the fact that he was born and raised in India and lived there for many years. 6Pritchard became the first Asian-born athlete to win an Olympic medal. Nevertheless, the late British Olympic historian Ian Buchanan argues that as Pritchard was a member of an old colonial family and though born in India, through descent he was indisputably British. In competitions in England his name was entered as a member of both the Bengal Presidency Athletic Club of India, and the London Athletic Club. It should also be noted that of the countries participating in the Paris Olympics, only a handful of countries registered their National Olympic Committees. These did not include either India or Great Britain, and it was not until the 1908 Olympics that athletes were officially registered by their countries. Until then they were free to register as individuals. In the archives and on its website, the International Olympic Committee continues to credit his two medals to India. However, disputes and debates persist, as authentic records were not maintained at the time. 7For the importance of national medal counts and the modern role of citizenship swaps see Horowitz and McDaniel (2015).

One unexpected side effect of the Scramble for Africa was that prospective players who were born and raised in Africa were eventually allowed to compete for their mother countries. An excellent example is the Portuguese football hero Eusébio da Silva Ferreira, born in Portuguese Mozambique in 1942. His parents were an Angolan railroad worker from Malanje, and a black Mozambican woman (Cleveland, 2017).

Mozambique was a colony until 1975. Eusébio was signed by the Portuguese club Benfica in 1961, was naturalised soon afterwards and went on to become a key player on Portugal’s national team. Eusébio was one of the five naturalised players who represented Portugal in the 1966 World Cup. This extraordinarily gifted generation could have made Mozambique a major force in world football, but there was no Mozambican state, or national team in 1966. These forms of colonial inclusion reflected Portuguese dictator Salazar’s attempt to justify continuing colonialism despite decolonisation elsewhere, by proclaiming that its African subjects were also Portuguese. While his fellow Mozambicans remained subject to harsh colonial rule that greatly limited their social and political rights, Eusébio was named by Salazar as a ‘national treasure’ (Darby, 2007; 2005). Nevertheless, even though colonialism played a role in these cases, one might argue that those concerned also earned their citizenship based on birthright and descent. In other words, they might still claim thick citizenship. Nevertheless, it articulates the distinction between legal and cultural and indeed racial associations in the case of colonised peoples in metropolitan centres. In these cases, some would argue that that the claim for citizenship is ‘thinner’, but ‘stretched’ in the direction of colonial territory (Campenhout et al., 2018)

There are many contemporarycases where forms of dual citizenship and colonial pasts are negotiated. The 1998 world champion men’s football, France, was celebrated for its multicultural team. However, most players were born and raised in France, albeit as children of (colonial) migrants (Maquire et al.). An interesting case is that of the Algerian team in the 2014 World Cup. Algeria arrived with 16 out of 23 (almost 70%) of its team who were born and raised in France. They were eligible to play for both Algeria and France (dual citizenship). Overall, there were 25 players born in France who did not represent France in the World Cup. However, those who were eligible and opted for the French team were not always received with patriotic feeling. In the words of the French international Karim Benzema, ‘Basically, if I score, I’m French. And if I don’t score or there are problems, I’m Arab’. 8Again, players themselves and national audiences openly debate the terms of belonging (Skey, 2015).

Jus nexi: socio-economic citizenship

In the third category, socio-economic citizenship, the focus is on cases where migrants or their ancestors claim jus nexi, or citizenship based on permanent interest in membership. Europe has recently experienced a marked increase in migration coming mainly from Morocco and Turkey (Lucassen, 2005; Mol & de Valk, 2016). These migrants, or their ancestors, claim jus nexi citizenship. Their offspring often claim dual citizenship, and the Olympic Committee and FIFA have developed special rules for these situations. For instance, the Germany-born player Mesut Ozil, is the son of Turkish migrant workers. Owing to his background (parents’ descent as well as birthright), he was allowed to play for both the Turkish and German national teams. Under the current FIFA regulations, players who have played for one national team cannot switch teams and play for another. Nevertheless, players are allowed to change their football nationality if they have played for the national youth team of another country. During the 2018 World Cup, it was estimated that more than 60% of the players representing Morocco were born in the Netherlands, France, Germany, or Spain. 9

Thin citizenship

There are three occasionally overlapping categories of thin citizenship. First, some athletes get caught up in the tricky web of wars and international politics. In recent history, the collapse of the Soviet Union, Yugoslavia, Czechoslovakia, and several others, lead to the replacement by new entities like Ukraine, Azerbaijan, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, and so on. Athletes in these countries, who lose their original citizenship, subsequently need to renegotiate where they belong based on their birthright and other forms of belonging. Simultaneously, both the International Olympic Committee and FIFA had to construct distinct rulings to deal with these exceptional cases. Second, in some cases, both athletes and states have stretched the rules of belonging, as with Viktor Ahn. Even though these are exceptional cases, it shows that if the time and place are right, regulations and principles can be overextended and become very thin indeed. Third, some athletes have represented three or more countries. Sometimes, this is a consequence of circumstances, which also occurs in the mixed forms of citizenship. Nevertheless, the cases presented here include a combination of ‘citizenship for sale’, lost citizenship, and mixed forms of citizenship. The fact that these athletes can shift citizenship more than once shows the scope for negotiation in exceptional cases where the institutional settings and historical context are favourable.

Lost, emerging and overlapping states and nations

In 1989, the promising Yugoslavian football team became world youth champions in Chile, playing together until 1990 when war broke out and Yugoslavia fell apart. First, the Croatian players left, then the trainer resigned because the Serbians bombed his home town of Sarajevo, and finally the team was banned from the European championships in Sweden under pressure from the international community. This ended the promising Yugoslavian squad. Some of the players in this team later played for Switzerland (Mills, 2009).

In the 2014 World Cup, Switzerland fielded seven migrant players permitted to play for Switzerland for several reasons. The midfielder Tranquillo Barnetta is of Italian descent and holds dual citizenship. Gokhan Inler’s parents were born in Turkey, though he was born in Switzerland. However, the most striking feature of Switzerland’s 2014 team was the number of players from former Yugoslavia. Among them, four had roots in Kosovo, two were from Bosnia, and two from Macedonia. Further, Granit Xhaka had previously played for Albania. Ironically, he faced his elder brother in the match against Albania in the 2016 European championship. Only 38% of the players in the 2014 selection for Switzerland were actually born there. 10

Citizenship for sale?

The most extreme examples of thin citizenship are cases where there is no parental ancestry, nor any birthright claim. Becky Hammon and Victor Ahn are good examples of thin citizenship. The female basketball player Becky Hammon was one of the most talented basketball players in the U.S. She signed a contract for CSKA Moskou in 2007. In 2008 she could sign up for the Russian team in return for a US$2 million-dollar contract. Even though Hammon is not of Russian descent, speaks no Russian and is not a full-time resident, she was fast-tracked for Russian citizenship in February by the highest levels of the Russian government (Schwarz, 2008). Dual citizenship made Hammon a precious commodity in the Russian league because two Russians must be on the floor at all times, and each club is allowed only two American players. As Hammon had never competed in a sanctioned international competition for American Basketball, The International Basketball Federation, more commonly known by the French acronym FIBA, rules allowed her to represent another country in the Olympics. Capitalising on the fact that FIBA rules allow one naturalised citizen to compete for each country, the Russians offered Hammon not only a passport but also an opportunity to play at the Olympics (Schwarz, 2008). In 2006, South Korea’s short-track skater Ahn Hyun-soo won three gold medals for his homeland. Due to injuries, Korea did not need him after 2010. So Ahn went searching for a new Olympic allegiance having fallen out with the South Korean Skating Federation. He and his father investigated naturalisation for top athletes in several countries – with the U.S. and Russia on the final shortlist. In 2011, Ahn Hyun-soo became a Russian citizen, changed his name to Viktor Ahn, and pledged to compete for his adopted homeland at the Sochi Games in 2014 (Business Insider, 2014).

The case of Hammon and Ahn acquiring Russian citizenship in exchange for money, status and the ability to compete at the highest level might be regarded as extreme examples of highly talented athletes’ ‘citizenship swaps’, or ‘talent for citizenship exchange’ (Kostakopoulou & Schrauwen, 2014; Shachar, 2011; Shachar et al., 2017). There were no prior ties between Hammon and Ahn to Russia. They had no Russian ancestors, nor did they speak Russian. 11In short, this example challenges the ritual affirmation of citizenship. This raises the question as to whether the world is heading towards the end of Olympic Nationality (Spiro, 2011). However, in this case, Russia and not the IOC decided the citizenship issue (Schwarz, 2008; Shachar, 2011, pp. 2090–2091; Jansen, 2019).

In the Rio Summer Olympics in 2016, Azerbaijan and Qatar – among others – portrayed themselves as entrepreneurial states willing to buy success. Azerbaijan sent 56 athletes to these Olympic Games. However, foreign athletes who changed their citizenship to compete under the Azerbaijani flag made up more than 60% of the delegation. Transfer of allegiance, ‘leg drain’, or ‘muscle drain’, is a fairly common phenomenon in the international sporting world, but for Azerbaijan, it would appear that it has become a matter of state policy. 12Twenty-three of Qatar’s 39 athletes were not born in Qatar. Its handball team of 14 players includes 11 foreign-born athletes. 13This in itself is not a new phenomenon, but the scale is striking. Media and some academic literature (Shachar, 2011, p. 2017) often suggest that states increasingly trade their most valuable and prestigious asset – citizenship – for medals and national prestige. Nevertheless, empirical evidence suggests a more nuanced perspective (Jansen et al., 2018; Jansen & Engbersen, 2017). These examples portray a very thin citizenship. There is no prior relationship through descent or birthright. More often than not, these athletes do not speak the language of the country they represent, nor is there any other cultural or religious identification. Countries allow these athletes to represent them in return for their ability to earn medals. Individual athletes are willing to swap their national identities (passports) in return for money and the ability to compete at the highest possible level.

Travelling loyalties

Some top athletes have become experts at using existing rules and negotiating an exchange of their skills for citizenships, passports, and money. Lascelles Brown, born in Jamaica in 1974, was a member of the Jamaican national bobsled team from 1999 to 2004, competing at the 2002 Winter Olympics in Salt Lake City. He continued training in Calgary, where he met and married his Canadian wife Kara. He applied for Canadian citizenship in 2005; it was awarded to him by special exemption just prior to the 2006 Winter Olympics, letting him compete for Canada at the games in Turin. Brown competed at the 2010 Winter Olympics, winning bronze in the four-man event. Brown then became a competitor for Monaco at the start of the 2010 season and was apparently paid well for his services. 14Brown combined both thick citizenship (born and raised in Jamaica), thin citizenship (representing Monaco for money), and an in-between version of the citizenship rules (representing Canada, as he lived and married there).

Similar cases have occurred in football. The famous footballer Laszlo Kubala (1927–2002) and the striker Alfredo Di Stéfano (1926–2014) played for three different national teams. Kubala played for Czechoslovakia, Hungary and Spain, while Di Stéfano played for Spain, Argentina and Columbia. Nevertheless, their migration history was less opportunistic and money-driven, and more politically motivated. Kubala was born in Budapest, as were his parents who came from mixed backgrounds. His mother had Polish, Slovak and Hungarian roots, while his father, belonged to the Hungary’s Slovak minority. In 1946, he moved to Czechoslovakia, allegedly to avoid military service, and joined ŠK Slovan Bratislava. In 1947, Kubala married the sister of the Czechoslovakian national coach, Ferdinand Daučík. He played for Czechoslovakia six times. In 1948, he returned to Hungary, again allegedly to avoid military service, and joined Vasas SC. In January 1949, as Hungary became a socialist state, Kubala fled the country in the back of a truck. He initially arrived in the U.S. zone of Allied-occupied Austria and then moved on to Italy, where he briefly played for Pro Patria. He was eventually signed to Barcelona in 1950. After adopting Spanish nationality, he played for Spain 19 times between 1953 and 1961.

Alfredo Di Stéfano was born in Buenos Aires, as the son of a first-generation Italian-Argentinian and an Argentinian woman of French and Irish descent. He played with the Argentinian national team six times. In 1949, a footballers’ strike in Argentina prompted him and many other Argentinean players to defect to a breakaway Colombian league outside the remit of FIFA, not obliged to pay transfer fees and able to pay generous wages to some of the world’s best players. In the 1950s, he began playing for Real Madrid in Spain and acquired Spanish citizenship in 1956. He played four World Cup-qualifying matches for Spain in 1957 and helped Spain qualify for the 1962 World Cup, though he was unable to participate himself due to injuries and his age.

In this last category, athletes who represented three or more countries were highlighted. At times, there were some ‘contributing relations’, as in the case of Lascelles Brown, who represented Canada after marrying a Canadian woman. However, his move to represent Monaco was motivated by money, as well as his desire to compete at the highest possible level, to participate in the Olympics one more time.

Afterthought and conclusion

Our proposed three categories – thick, in-between, and thin citizenship – are not mutually exclusive and do occasionally overlap. An exceptional example is Zola Budd, the middle- and long-distance runner born in 1966 in South Africa. Her parents were also born in South Africa. Her case would be defined as thick citizenship if she represented South Africa. Nevertheless, her story brought her to Britain. At the age of 17, Budd broke the women’s 5000 m world record. Since her performance took place in South Africa, then excluded from international athletics competition because of its apartheid policy, the International Amateur Athletics Federation (IAAF) refused to ratify her time as an official world record.

The British tabloid, the Daily Mail persuaded Budd’s father to encourage her to apply for British citizenship, on the grounds that her grandfather was British, to circumvent the international cultural (therefore also sporting) boycott of South Africa. The Daily Mail would have exclusive rights to Budd’s story and would put U.K.£40,000 into a fund for her, as well as providing rent-free housing for the family and finding a job for her father. The Daily Mail started an active campaign and began to put pressure on a series of ministers to give Budd a passport. They wished to see her competing for Team Britain during the 1984 Summer Olympics. Thus a fast track citizenship procedure was started. However, the Home Office was reluctant to grant such status stating:

To give exceptional treatment to a South African national to enable her to avoid the sporting restrictions inflicted on her country and compete for Britain in the Olympics will be seen as a cynical move which will undermine that good faith. 15

Groups supporting the abolition of apartheid campaigned to highlight the special treatment she received; other applicants had to wait sometimes years to be granted citizenship, if at all. In short, just ten days after she formally applied for British citizenship, the 17-year-old got her passport. It remains unclear whether the justification was based on her talent, her ancestry, or a combination of both. However, what this example shows, is how cases can shift from thick citizenship to the in-between category of citizenship. This exceptional case is different from the citizenship for sale example in the thin citizenship category. It was not the state, but a newspaper that paid for the citizenship swap for medal chances. Undoubtedly, however, the fact is that money and the citizenship switch were directly related.

What is important here is that there is room to negotiate citizenship and the transfer of citizenship. Depending on territorial birthright, ancestry, political circumstances and financial incentives, the rules for access to citizenship are stretched. Interestingly, Budd competed for South Africa at the 1992 Olympics after the country was re-admitted to international competition following a referendum vote to end the apartheid system.

Historical research has shown that acquiring modern citizenship has taken different paths: territorial birthright and descent. More often than not they were not mutually exclusive, but reinforced each other. Nevertheless, through these paths and the emergence of the jus sanguinis system, access to multiple citizenships became part of the inheritance – or citizenship capital of individuals. In the past decades, some states, particularly in the Middle East and Asia, have attracted foreign labour in return for citizenship rights. A growing number of migrants have also acquired citizenship through a jus-nexi connection. These developments have created space for states, sport-institutions and individual athletes to negotiate their citizenship status.

The study proposed three categories of relationships between migrant athletes and country. These cases resemble Bauböck’s concept of thin and thick conceptions of citizenship (1999). Further, the cases discussed within this model give room for Bloemraad’s suggestion to discuss ‘citizenship from below’, and ‘citizenship as claims-making’ (2018). These models also apply to non-sporting contexts. However, the context of international sports is distinctive for two major reasons. First, athletes represent the country on a widely publicised international stage. Second, because of associated prestige, athletes’ connections with the homeland, motherland, or ‘genuine links’ with the country they represent are often part of public debate. (Campenhout et al., 2018; Jansen et al., 2018) Thin citizenship describes examples of citizenship changes where the athlete has no prior relationship with the country that they represent, as in the cases of Viktor Ahn and Becky Hammon. Moreover, this category includes migrants from states that dissolved, like Yugoslavia and the USSR. The national players of these countries became part of new countries or migrated. At the other extreme, I defined the thick citizenship, which refers to the merger of territorial birthright (jus soli), descent (jus sanguis), and ‘contribution’ (jus nexi). The in-between categories are the most interesting, but they are also difficult to define. Here, the concept of colonial citizenship is included, where migrant athletes are, or were part of the larger jus soli of the country, or colonial enterprise. Nevertheless, this category also includes recent migrant, where athletes are part of the jus nexi of their new homes. The three categories are not mutually exclusive, as has become clear in the case of Zola Budd.

In short, the primary question: who may represent the country? cannot be easily answered. Categories of belonging are blurred, and athletes, sports federations, institutions, states, and audiences constantly negotiate them. The question is, therefore, not whether athletes and/or states strategically use citizenship regulations for their own purpose, they probably are. The ear when scholars could convincingly argue that national sporting stars are unifying representatives (Duke & Liz, 1996) are now under scrutiny. This study argued that citizenship rules and justifications for national belonging are stretched. This stretching can be seen as a global continuum between thick and thin citizenship. The answer to the moral question: who may represent the country? might be found in the history of the Olympics. Until 1908 it was possible to compete with mixed teams and to enter as an individual, not necessarily representing a country. This, then, might come close to the suggestion of Iowerth et al. (2014) that sporting bodies should be more pragmatic in their criteria of national belonging.

Notes