#jewish identity

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

I think a lot of Americans have a hard time grasping the idea of Jewish indigeneity because they dont know where their own ancestors came from. Maybe they'll have vague ideas like German, Italian, or Irish, but what they know has very little bearing on their day-to-day lives. They don't dress any different, they don't speak the language their great grandparents spoke, they don't hold regular ceremonies and rituals that harken back to the old days.

The idea of an ethnic group maintaining a constant identity over thousands of years is patently absurd to them. "You're telling me you're still mourning something the ancient Romans did? That's ridiculous! Clearly you've fallen for modern Israeli propaganda, otherwise you're deliberately arguing in bad faith in order to justify land theft and genocide!"

It's very frustrating, because when I say these things I do not say them in bad faith. My friend once said "it's a very American thing not to understand large timescales", and I think she was right on the money. The process of American assimilation has cut peoples ties to their ancestors to such a degree that they can no longer comprehend a continuous identity spanning millennia.

So I'm going to say this in the clearest language I can:

There is a genuine, historically provable, continuous connection from ancient Israelites to modern Jews. By the laws and customs of those ancient Israelites I am one of them. Let me reiterate. I am an Israelite, a Hebrew, like from the Bible, and the fact that my identity has been so mythologized and talked about as if it's a thing of the past will never change that.

#fuzzytheduck#jumblr#jewish#judaism#frumblr#antisemitism#jewblr#jewish stuff#jewish history#israel#jewish identity#jew tag#jew stuff#jewish things

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Every single time I hear someone referring to a Jewish person as ‘white’ another little piece of my soul dies.

As a non-American Jew, the first time I ever heard Jews being referred to as white was when I was a full grown adult watching an American reality show. I FOR REAL thought they were making that shit up in order to generate buzz and get people talking about the controversy! That’s how foreign the notion was to me. Imagine my shock and horror to discover that THIS IS A COMMON MISCONCEPTION IN THE UNITED STATES.

It’s the way that referring to Jews as ‘white’ ERASES white people’s antisemitism, it erases our persecution at the hands of white people, it erases our suffering, it erases the OTHERING that Jews had suffered for CENTURIES from actual white people.

Based on what the skin tone of some Jews in a few places might afford them SO LONG AS NO ONE KNOWS THEY’RE JEWISH.

If you have to hide your real identity in order to enjoy the privileges of being perceived as white, YOU’RE NOT WHITE (this is true for Jews just like it is true for other white-passing People of Color).

White passing is not the same as white.

WHITE PASSING IS NOT THE SAME AS WHITE.

Jews are NOT white. Not a single one of us. Not even the ones who can pass as white, let alone all of the Jews who can’t.

#jews#jew#jumblr#jr#jewish#jewish stuff#jewish history#jewish identity#antisemitism#frumblr#white passing#is not the same as white#jews of tumblr#jewish privilege#jews are not white#jewish dignity#jewish people#judaism#antisemites#resources

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

I wasn’t going to say anything, but seeing people get chastised over saying “Rest in Peace” for Michelle Trachtenberg instead of using the Hebrew phrase? Yeah, I need to.

My great-grandfather was Jewish. He married a Catholic woman who loved him, and instead of erasing his traditions, she embraced them. She honored both Jewish and Catholic holidays. She handmade decorations for both. We still have them. We still carry that love, even if we aren’t practicing. Because being Jewish isn’t just about practice—it’s about family, history, and remembrance.

And that’s why this whole discourse hurts.

Most people saying “Rest in Peace” aren’t trying to erase Jewish mourning traditions. They aren’t trying to be disrespectful. They’re just expressing love in the only way they know how. And instead of taking a moment to teach, to connect, to build bridges—some of you would rather tear people down for not already knowing.

But here’s the thing: Judaism has survived through remembering. Through teaching. Through welcoming people in rather than shutting them out. My family held onto our Jewishness through love, not through pushing people away. Maybe—just maybe—that’s something to think about before deciding that someone’s sympathy isn’t “correct” enough.

Because in the end? What matters isn’t the exact words used. It’s that she is remembered. And that people care. 💙

#michelle trachtenberg#judaism#jewish#jumblr#culture#jewish mourning#rest in peace#zichronah Livracha#grief#respect#jewish history#jewish heritage#jewish tumblr#jewish identity#jewish remembrance#jewish solidarity#discourse#callout culture#internet culture#tumblr discourse#activism vs performative activism#let people grieve

211 notes

·

View notes

Text

I don’t usually talk about politics on here, if ever. But it’s been almost six months since the conflict in the Middle East flared up again, and I’m finally ready to start. Here are some of my thoughts.

I say ‘flared up’ because this has happened before and it’ll happen again. Because, even though what's currently going on is absolutely unprecedented, those of us who live in this part of the world are used to it. Let that sink in: we are used to this. And we shouldn’t have to be.

But I use that term for another reason: I don't want to accidentally call it the wrong thing lest I come under fire for being a genocidal maniac or a terrorist or a propaganda machine, etc., etc.—so let’s just call it ‘the war’ or ‘the conflict.’ Because that’s what it is. Doesn’t matter which side you’re on, who you love, or who you hate.

This post will, in all likelihood, sit in my drafts forever. If it does get posted, it certainly won’t be on my main, because I'm scared of being harassed (spoiler: she posted it on her main). I hate admitting that, but honestly? I’m fucking terrified.

I also feel like in order for anything I say on here (i.e. the hellscape of the internet) to be taken seriously, I have to somehow prove that a) I’m “educated” enough to talk about the conflict, and b) that my opinion lines up with what has been deemed the correct one. So, tedious and unnecessary though it is, I will tell you about my experience, because I have a feeling most of the people reading this post are not nearly as close to what’s happening as I am.

How do I explain where I live without actually explaining where I live? How do I say “I live in the Red Zone of international conflicts” without saying what I actually think? How do I convey the fear that grips me when I try to decide between saying “I live in Palestine” and “I live in Israel”? I don't really know. But I do know that names are important. I also know that, due to the various clickbaity monikers ascribed to the conflict, it would probably just be easier to point to a map.

I haven't always lived in the Middle East. I've lived in various places along America’s east coast, and traveled all over the world. But in short, I now live somewhere inside the crudely-drawn purple circle.

If you know anything about these borders you probably blanched a bit in sympathy, or maybe condolence. But in truth, it’s a shockingly normal existence. I don't feel like I've lived through the shifting of international relations or a war or anything. I just kind of feel like I did when COVID hit, that dull sameness as I wondered if this would be the only world-altering event to shape my life, or if there would be more.

I've been told that, in order for my brain to process all the horrific details of the past six months, there needs to be some element of cognitive dissonance—that falling into a sort of dissociative mindset is the only way to not go insane under the weight of it all. I think in some ways that’s true. I have been terrifyingly close to bus stop shootings when my commute wasn’t over; I have felt my apartment building shake with the reverberations of a missile strike; I have spent hours in underground shelters waiting for air raid sirens to stop.

But. I have also gone grocery shopping, and skipped class, and stayed up too late watching TV, and fed the cats on the street corner, and cried over a boy, and got myself AirPods just because, and taken out the trash, and done laundry on a delicate cycle, and bought overpriced lattes one too many days a week. I have looked at pretty things and taken out my phone because, despite it all, I still think that life is too short not to freeze the small moments.

So I'd say, all things considered, I live an incredibly privileged life—compared, of course, to those suffering in Gaza—one filled with sunsets and over-sweetened knafeh and every different color of sand. One that allows me to throw myself into a fandom-induced hyperfixation (or, alternatively, escape method) as I sit on the couch and crack open my laptop to write the next chapter of the fic I'm working on.

But there are bits of not-normalness that wheedle their way through the cracks. I pretend these moments are avoidable, even if they’re not.

They look like this: reading the news and seeing another idiotic, careless choice on Netanyahu’s part and groaning into my morning coffee. Watching Palestinian and Jewish children’s needless suffering posted on Instagram reels and feeling helpless. Opening my Tumblr DMs to find a message telling me to exterminate myself for reblogging a post that only seems like it’s about the war if you squint and tilt your head sideways.

These moments look like all the tiny ways I am reminded that I'm living in a post-October seventh world, where hearing a car backfire makes me jump out of my skin and the sound of a suitcase on pavement makes me look up at the sky and search for the war planes. They look like the heavy grief that is, and also isn’t, mine.

Here's the thing, though. I know you’re wondering when the ball will drop and my true opinion will be revealed. I know you’re waiting for me to reveal what demographic I'm a part of so that you, dear reader, can neatly slap a label on my head and sort me into some oversimplified category that lets you continue to think you understand this war.

No one wants to sit and ruminate on the difficult questions, the ones that make you wonder if maybe you’ve been tinkered with by the propaganda machine, if you might need to go back on what you’ve said or change your mind. We all strive for our perception of complicated issues to be a comfortable one.

But I know that no matter what I do, there will always be assumptions. So, while I shudder to reveal this information online, I think that maybe my most significant contribution to this meta-discussion spanning every facet of the internet is this:

I am a Jew.

Or, alternatively, I am: Jewish, יהודית, يَهُودِيٌّ, etc. Point is, I come from Jews. And, like any given person, I am a product of generation after generation of love.

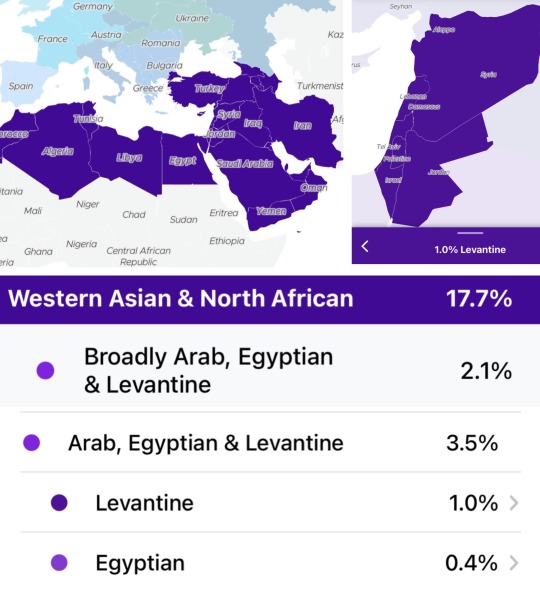

I'm not going to take time to explain my heritage to you, or to prove that before all the expulsions and pogroms, there was an origin point. If you don’t believe that, perhaps it’s less of a factual problem and more of an ‘I don’t give weight to the beliefs of indigenous people’ problem. But, in case you want to spend time uselessly refuting this tiny point in a larger argument, you can inspect the photos below (it’s just a small chunk of my DNA test results). Alternatively, you can remember that interrogating someone in an attempt to make their indigeneity match your arbitrary criteria is generally not seen as good manners.

Now, let’s go back to thathateful message (read: poorly disguised death threat) I received in my Tumblr DMs. I think it was like two or three weeks ago. I had recently gained a new follower whose blog’s primary focus was the fandom I contribute to, so I followed them back. I saw in my notes that they were going through my posts and liking them—as one does when gaining a new mutual. Yippee!

Then they sent me this:

I tried to explain that hate speech is not a way to go about participating in political discourse, but the person had already blocked me immediately after sending that message. Then, assured by the fact that I surely would never see them complaining about me on their blog (because, as I said, they blocked me), they posted a shouting rant accusing me of sympathizing with colonizing settlers and declaring me a “racist Zionist fuck.” Oh, the wonders of incognito tabs.

Where this person drew these conclusions after reading my (reblogged) post about antisemitism…. I'm not actually sure. But I greatly sympathize with them, and hope that they weren’t too personally offended by my desire to not die.

For a while I contemplated this experience in my righteous anger, and tried to figure out a way to message this person. I wanted to explain that a) seeing a post about being Jewish and choosing to harass the creator about Israel is literally the definition of antisemitism and b) that sending a hateful DM and refusing to be held accountable is just childish and immature. But I gave up soon after—because, honestly, I knew it wasn’t worth my effort or energy. And I knew that I wouldn't be able to change their mind.

But I still remember staring at that rather unfortunate meme, accompanied by an all-caps message demanding for me to Free Palestine, and thinking: the post didn’t even have any buzzwords. I remember the swoop of dread and guilt and fear. I remember wondering why this kind of antisemitism felt worse, in that moment, than the kind that leaves bodies in its wake.

I remember thinking, I don’t have the power to free anyone.

I remember thinking, I’m so fucking tired.

And before you tell me that this conflict isn’t about religion—let me ask you some questions. Why is it that Israel is even called Israel? (Here’s why.) Why do Jews even want it? (Here’s why.) But also, if you actually read the charters of Islamist terrorist organizations like ISIS, Hamas, and Hezbollah (among others), they equate the modern state of Israel with the Jewish people, and they use the two entities interchangeably. So of course this conflict is religious. It’s never been anything but that.

But I do wonder, when faced with those who deny this fact: how do I prove, through an endless slew of what-about-isms and victim blaming, that I too am hurting? How do I show that empathy is dialectical, that I can care deeply for Palestinians and Gazans while also grieving my own people?

There's this thing that humans do, when we’re frustrated about politics and need to howl our opinions about it into the void until we feel better. We find like-minded souls, usually our friends and neighbors, and fret about the state of the world to each other until we’ve gone around in a satisfactory amount of circles. But these conversations never truly accomplish anything. They’re just a substitute, a stand-in catharsis, for what we really wish we could do: find someone who embodies the spirit of every Jew-hating internet troll, every ignorant justifier of terrorism, and scream ourselves hoarse at them until we change their mind.

But, of course, minds cannot be changed when they are determined to live in a state of irrational dislike. In Judaism, this way of thinking has a name: שנאת חינם (sinat hinam), or baseless hatred. It's a parasite with no definite cure, and it makes people bend over backwards to justify things like the massacre on October seventh, simply because the blame always needs to be placed on the Jews.

So when a Jew is faced with this unsolvable problem, there is only one response to be had, only one feeling to be felt: anger. And we are angry. Carrying around rage with nowhere to put it is exhausting. It's like a weight at the base of our neck that pushes down on our spine, bending it until we will inevitably snap under the pressure. I’m still waiting to break, even now.

I wish I could explain to someone who needs to hear it that terrorism against Israelis happens every single day here, and that we are never more than one degree of separation away from the brutal slaughter of a friend, lover, parent, sibling. I wish it would be enough to say that the majority of Israelis (which includes Arab-Israeli citizens who have the exact same rights as Jewish-Israelis) wish for peace every day without ever having seen what it looks like.

I wish I could show the world that Israel was founded as a socialist state, that it was built on communal values and born from a cluster of kibbutzim (small farming communities based on collective responsibility), and that what it is now isn’t what its people stand for.

I wish the world could open their eyes to what we Israelis have seen since the beginning: that Hamas is the enemy, Hamas is the one starving Palestinians and denying them aid, Hamas is the one who keeps rejecting ceasefire terms and denying their citizens basic human rights. Hamas is the governing body of Gaza, not Israel. Hamas is responsible for the wellbeing of the Palestinian people. And Hamas are the ones who are more determined to murder Jews—over and over and over again, in the most animalistic ways possible—than to look inwards and see the suffering they’ve inflicted on their own people. I wish it was easier to see that.

But the wishing, the asking how can people be so blind, is never enough. I can never just say, I promise I don't want war.

When I bear witness to this baseless hatred, I think of the victims of October seventh. I think of the women and girls who were raped and then murdered, forever unable to tell their stories. I think of the hostages, trapped underneath Gaza in dark tunnels, wondering if anyone will come for them. I think of Ori Ansbacher, of Ezra Schwartz, of Eyal, Gilad, and Naftali, of Lucy, Rina, and Maia Dee, of the Paley boys, of Ari Fuld and of Nachshon Wachsman. I think of all the innocent blood spilled because of terror-fueled hatred and the virus of antisemitism. I think of all the thousands of people who were brutally murdered in Israel, Jews and Muslims and Christians and humans, who will never see peace.

My ties to this land are knotted a thousand times over. Even when I leave, a part of me is left behind, waiting for me to claim it when I return. But when I see the grit it takes to live through this pain, when I see the suffering that paints the world the color of blood, I look to the heavens and I wonder why.

I ask God: is it worth all this? He doesn't answer. So I am the one, in the end, to answer my own question. I say, it has to be.

Feel free to send any genuine, respectful, and clarifying questions you may have to my inbox!

EDIT: just coming on here to say that I'm really touched & grateful for the love on this post. When I wrote it, I felt hopeless; I logged off of Tumblr for Shabbat, dreading the moment I would turn off my phone to find more hate in my inbox. Granted, I did find some, and responding to it was exhausting, but it wasn’t all hate. I read every kind reblog and comment, and the love was so much louder. Thank you, thank you, thank you. 🤍

Source Reading

The Whispered in Gaza Project by The Center for Peace Communications

Why Jews Cannot Stop Shaking Right Now by Dara Horn

Hamas Kidnapped My Father for Refusing to Be Their Puppet by Ala Mohammed Mushtaha

I Hope Someone Somewhere Is Being Kind to My Boy by Rachel Goldberg

The Struggle for Black Freedom Has Nothing to Do with Israel by Coleman Hughes

Israel Can Defend Itself and Uphold Its Values by The New York Times Editorial Board

There Is a Jewish Hope for Palestinian Liberation. It Must Survive by Peter Beinart

The Long Wait of the Hostages’ Families by Ruth Margalit

“By Any Means Necessary”: Hamas, Iran, and the Left by Armin Navabi

When People Tell You Who They Are, Believe Them by Bari Weiss

Hunger in Gaza: Blame Hamas, Not Israel by Yvette Miller

Benjamin Netanyahu Is Israel’s Worst Prime Minister Ever by Anshel Pfeffer

What Palestinians Really Think of Hamas by Amaney A. Jamal and Michael Robbins

The Decolonization Narrative Is Dangerous and False by Simon Sebag Montefiore

Understanding Hamas’s Genocidal Ideology by Bruce Hoffman

The Wisdom of Hamas by Matti Friedman

How the UN Discriminates Against Israel by Dina Rovner

This Muslim Israeli Woman Is the Future of the Middle East by The Free Press

Why Are Feminists Silent on Rape and Murder? by Bari Weiss

#palestine#israel hamas war#israel hamas conflict#hamas#on war#essay writing#personal essay#rant post#stop terrorism#israel#writing#palestinian lives matter#jewish lives matter#jewish and proud#jewish identity#jewish muslim solidarity#on grief#on religion#antisemitism#anti zionisim#purim 2024#chag purim sameach#judaism#israeli palestinian conflict#am yisrael chai#kvetching#jumblr#the post that turned my blog into an anti-antisemitism blog

724 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mythological beasts are frequently representations and compartmentalizations of societal fears. Take the dragon: a type of European kaiju that, in contemporary European depictions, represents the fear of a bad king or other political figure. This representation evolved slowly and, ironically, solidified only after most monarchies of Europe fell. Pieces of media like Beuwulf, Saint George and the Dragon, The Völsunga Saga, The Faerie Queene, The Hobbit, Dungeons and Dragons, The Elder Scrolls, as well as folkloric stories like that of the Lindwurm and Tarrasque chart the development of this symbology over history.

The dragon:

Kidnaps princesses (endangers the future of the royal lineage)

Hoards gold (refuses to enrich the kingdom by spending anything)

Terrorizes townsfolk (imposes unjust, tyrannical rule)

Breathes fire (spreads devastation)

And is slain by a knight (the social position of a knight is occupied almost exclusively by children of noble houses. The implication here being that the dragon is rightfully disposed of by an inter-elite power struggle)

Likewise, the werewolf represents societal feats of several types that all relate to a central theme of savagery, of two primary veins: human savagery and environmental savagery. People today have poor comprehension of what true wilderness looks like. Ask a veteran what Vietnam was like, that's what the Teutoburg forest and, for that matter, almost every European forest was like until just a few hundred years ago. That shit was dark and scary. Thicket was so abundant and the canopy so heavy that visibility of less than 10 meters was common. Different crops require different soil conditions, and before the introduction of the potato and other crops to Europe, many areas were unsuitable for barley, wheat, millet, oats, etc, and therefore just… completely unsuitable for agriculture. With no profitable land use to justify clearcutting, there were vast areas of untamed wilds. The dark forests were imagined to be able to contain anything, even monsters. The type of monster that could prowl just out of sight and yet startlingly close.

Certain murders were so brutal that people refused to believe them to be human work, and needed to ascribe to a bestial party. Warriors across history (Aztec jaguars, Norse Ulfhednars, etc) used animals as symbols of their ferocity, thinking along these lines. Human bloodlust extended to depths that we refuse to recognize as human, and the werewolf also represents this.

The witch, the empowered woman.

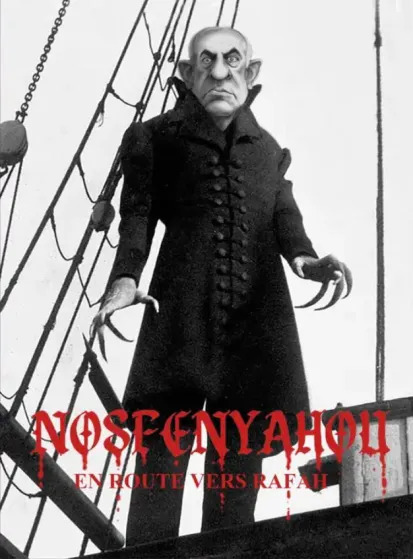

The vampire represents the fear of the Jew.

This is not an exaggeration or a fringe theory, it’s baked into the very core of European vampire mythology. The archetype is steeped in antisemitic tropes, drawing from centuries of paranoia about Jewish assimilation, financial influence, and cultural survival. This archetype did not emerge in a vacuum. The antisemitic construction of Jewish identity in medieval and modern Europe shaped the vampire’s core traits, and from it was built a monster that could seamlessly embody the deepest fears of Christian European societies, fears about assimilation, power, rootlessness, and economic control, all while claiming to be just another piece of folklore. Where the werewolf embodies the fear of regression into primal violence and untamed wilds, and where the dragon is the fear of an aristocracy grown fat and incompetent, the vampire reflects a different kind of anxiety: the fear of the Other who blends in too well. The Vampire moves through societies unnoticed, quietly accumulating wealth, knowledge, and power. It crosses borders effortlessly, carrying its curse from nation to nation. It is aristocratic yet rootless, influential yet foreign, a permanent outsider who thrives by being inside.

The vampire’s ability to pass as human reflects one of the oldest European anxieties about Jewish communities: the fear of assimilation. While Jews in Europe faced constant marginalization, those who integrated too successfully into mainstream society were viewed with equal suspicion. The very act of existing in banking, politics, or academia, fields where Jews, often forced out of land ownership and trade guilds, historically found opportunity, became evidence of a secret agenda. The idea that Jews could be among the people but never of the people, that they outwardly conformed while covertly undermining, mirrors the vampire’s double life.

Bram Stoker’s Dracula plays this fear straight. The Count is no mindless beast. He is an intelligent, strategic, plotting figure who methodically expands his influence. He is not a rampaging invader but a subtle one, acquiring property in London, blending into the city, and corrupting English women. His invasion is not one of brute force but of clandestine manipulation. His very existence threatens to change British society from within, much like contemporary fears of Jewish immigration and cultural influence. The novel also explicitly likens vampirism to disease, reinforcing the antisemitic trope of Jews as bearers of plague and sickness

Just as antisemitic conspiracies have long framed Jews as secret rulers of finance, media, and politics, Dracula does not simply kill his victims: he controls them. He mesmerizes, seduces, and turns his enemies into his thralls, all while maintaining the illusion of civility. The Victorian fear of Jewish influence and the literary fear of vampiric mind control are two sides of the same paranoid coin.

One of the most enduring antisemitic tropes in Europe was the fear of Jewish mobility. The idea that Jews were always moving: that they had no fixed homeland, that they could enter and leave societies as they pleased was a source of deep resentment. Jews had a unique ability to escape persecution, to establish networks across borders, to find distant allies when local ones failed. European xenophobia resented this, and nowhere is that resentment clearer than in the vampire myth. The vampire, much like the imagined Jew, is never truly from anywhere. Yes, it may have an ancestral home (the Eastern European castle, the shadowy Transylvanian estate), but it is fundamentally unbound to a single place. It moves fluidly between cities, between nations, bringing its influence wherever it goes. Dracula is not terrifying because he exists in Transylvania. He is terrifying because he leaves Transylvania and comes to London. His ability to cross borders mirrors the Jewish diaspora’s ability to move, adapt, and survive despite centuries of persecution. This taps into an old European fear: that Jews, unbound by national loyalty, could never be fully controlled. The wandering vampire, like the wandering Jew, is a figure of deep-seated anxiety: not just because he is foreign, but because he does not stay foreign.

Historically, the European imagination has always had a special paranoia reserved for Jews, figures simultaneously seen as too integrated and yet fundamentally foreign, too powerful yet victimized, too wealthy yet parasitic. The vampire, an undead aristocrat with an unquenchable thirst, is the perfect folkloric embodiment of this contradiction.

The most obvious link between the vampire and European antisemitism is the myth of blood libel: the centuries-old conspiracy theory that Jews kidnapped Christian children and used their blood for rituals, particularly making matzah. I don’t think I need to elaborate too much to draw the connection between allegations that Jews used the blood of goyim for sustenance and a mythological beast that uses the blood of the innocent for sustenance. This grotesque fabrication led to pogroms, massacres, and enduring accusations of Jewish parasitism. The idea of a creature whose very existence depends on secretly draining the lifeblood of innocents is an obvious echo of these accusations.

The vampire’s unnatural hunger also aligns with longstanding fears about Jewish economic roles. European societies, often banning Jews from landowning or trade guilds, forced them into financial professions such as moneylending, positions that made them indispensable yet despised. Thus, the vampire is not just a bloodsucker but an economic one, hoarding wealth while contributing nothing (a staple accusation against Jews, despite the fact that Jewish communities were often economically marginalized). The vampire’s aversion to the cross is one of its most overtly Christian-coded weaknesses, reinforcing the antisemitic underpinnings of the archetype. If the vampire is a stand-in for the Jew—an outsider infiltrating Christian society, hoarding wealth, corrupting the innocent—then the cross is a clear symbol of Christian supremacy, the force that repels and defeats the encroaching Other. This dynamic maps onto medieval Christian narratives of Jewish theological and spiritual inferiority, in which Jews were depicted as enemies of Christ who could only be redeemed through conversion or subjugation. Just as the vampire cannot bear the sight of the cross, Jews in Christian Europe were often forced to visibly submit to Christian authority—whether through mass conversions, forced public disputations, or the wearing of identifying badges. The cross’s power over the vampire echoes the theological claim that Christianity alone can vanquish evil, reinforcing the idea that Jewish presence in Christian lands was inherently corrupting, something to be resisted, expelled, or destroyed.

Unlike the werewolf, whose monstrous nature is barely hidden beneath the surface, the vampire is a master of disguise. It looks human, speaks human languages, dresses like a European aristocrat, but it is something else entirely. It is not merely an external threat but an internal one, an infiltrator, a parasite hiding among its prey. This aligns precisely with antisemitic fears about Jewish assimilation: the idea that Jews, despite integrating into European society, remained alien and subversive.

The Protocols of the Elders of Zion, the infamous antisemitic forgery, paints Jews as conspirators who secretly control the world. The vampire myth plays into this same anxiety: here is a creature that appears civilized but secretly plots against humanity. Count Dracula, for instance, is not a rampaging beast but a calculating mastermind who orchestrates his spread into London like a military strategist or a corrupt financier (depending on which antisemitic stereotype you prefer). The fear is not just that he is powerful, but that his power is hidden.

The idea of a vampire coven as a stand-in for the Jewish cabal is one of the strongest recurring motifs in vampire fiction, paralleling antisemitic conspiracy theories that claim Jews operate in secret networks to manipulate world affairs. These narratives frame vampires as an unseen, tightly organized elite that controls human society from the shadows, just as antisemitic conspiracies depict Jews as clandestine rulers of politics, finance, and culture. The Volturi, The Masquerade, The Vampire Council, Dracula’s Court, all of these mirror various forms of ZOG conspiracism to one degree or another.

Physical descriptions of vampires, particularly in 19th and early 20th-century literature, were not subtle in their alignment with antisemitic imagery. Count Dracula is described with an "aquiline nose," "peculiarly arched nostrils," and "sharp white teeth." These are not neutral traits. They are lifted directly from the antisemitic caricatures that filled European political cartoons. Stoker was writing at a time when Britain was panicking about Eastern European Jewish immigration, so the portrayal of vampires as having these Jewish features is unsurprising. The vampire’s foreignness, reinforced by its physical attributes, marks it as an outsider who cannot be trusted.

This is not unique to Dracula. Early vampire films like Nosferatu (being merely Dracula with the serial numbers filed off) exaggerated these features even further. Count Orlok’s hooked nose, elongated fingers, and rat-like demeanor align perfectly with the way Jews were depicted in early 20th-century antisemitic propaganda. The film takes Dracula’s subtext and makes it explicit: the vampire, like the imagined Jew, is a grotesque foreign invader who must be stopped before he corrupts the innocent. Count Orlok’s also literally spreads plague by controlling rats, directly mirroring European antisemitism and aligning Jews with disease in the popular imagination. In Carmilla, the titular vampire infiltrates aristocratic families, seducing and manipulating women while maintaining an illusion of innocence. Her ability to blend in and subvert social norms mirrors the conspiracy that Jews secretly manipulate governments, culture, and morality.

Similarly, the vampire’s wealth and status align with the old aristocratic paranoia about Jewish financiers. Just as Jews were accused of controlling economies through banking and usury, the vampire hoards gold and property, living in a secluded, fortress-like estate. The difference, of course, is that while Jews were often forced into financial professions as a matter of survival, the vampire chooses its parasitism, it is a predator by nature.

Another piece of this antisemitic puzzle is the vampire’s immortality. European folklore was filled with narratives about Jewish rootlessness, the idea that Jews, scattered across the world, never truly belonged anywhere. Jews were framed as an unchanging and eternal presence: foreigners who, despite persecution and exile, never truly disappeared. This is exemplified in the myth of the Wandering Jew, a Christian legend about a Jewish man cursed to walk the earth forever. The vampire’s eternal existence mirrors this idea, another Other who cannot be killed, cannot be expelled, and cannot be fully integrated into the societies it inhabits. The Jew, and the vampire, cannot be eradicated and always seems to resurface.

Vampires, like the stereotyped Jewish banker, do not produce anything. They consume. They do not labor in the fields or contribute to industry. Vampires live off the labor of others without producing anything themselves. They extract wealth from those who do. They control vast resources but do so in a secretive and unnatural way. They are not merely rich: they are unnaturally rich, wealthy beyond human lifespans, hoarding gold that has compounded across centuries and across human lifespans. They manipulate markets (or minds), they consolidate influence, and they always seem to have more power than they should.

This echoes historical stereotypes about Jewish financial power. The image of the Jewish banker, and particularly the Jewish banking family, the archetypical example being the Rothschilds, manipulating global economies maps neatly onto the idea of the vampire aristocrat and their coven who puppeteer society from the shadows. The enduring myth of Jewish financial conspiracy as seen in Bilderberg conspiracies, WEF conspiracies, etc, finds its gothic counterpart in the vampire’s role as a hidden predator of wealth and vitality. The idea that Jews secretly control global economies maps perfectly onto the vampire’s role as a shadowy, omnipotent predator.

The vampire, more than any other monster, reflects the anxieties of the societies that create it. Unlike the werewolf, whose horror lies in its loss of control, or the dragon, whose terror stems from brute force, the vampire’s horror is one of subtlety. It does not attack: it corrupts. It does not rampage: it manipulates. It is powerful, wealthy, and, most horrifying of all: hidden and mobile. Like all monsters, vampires reflect the fears of the societies that create them. The vampire is not just a bloodsucker, it is a construct of European paranoia, a vessel for anxieties about Jews as economic, social, and political infiltrators. By mapping these fears onto a supernatural figure, European cultures could demonize Jewish people while pretending it was just fiction.

The historical underpinnings of antisemitism remain embedded in the DNA of the archetype of the vampire. When a vampire is inserted into a modern story as allegory or to critique, the history of the vampire inherently changes the critique. a story where a CEO is a vampire is usually not just a critique of corporate influence on society, it becomes a critique of Jewish corporate influence on society, either that CEOs are too jewish or wielding power too Jewishly.

The Vampire as a cultural figure has been extremely long lasting, as has antisemitism as a stigma. The connection between the vampire archetype and antisemitic depictions of Jews is not confined to the dusty pages of Gothic literature. It thrives in modern media, where the vampire remains the go-to monster for representing Jewish figures, both subtly and overtly. This persistent metaphor reveals how deeply embedded antisemitic tropes are within Western cultural narratives, often resurfacing even in spaces that consider themselves progressive or socially aware.

A striking example of this phenomenon is the frequent depiction of Stephen Miller, a Jewish political advisor in the Trump administration, as a vampire. In The Majority Report, a popular left-leaning YouTube channel, a segment titled "Real-Life Vampire Stephen Miller Delivers Absolutely Chilling Response At CPAC" https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tBzHHAxkwQw taps into this imagery. The fact that Sam Seder himself is Jewish proves that Jews are not inoculated against the effectiveness of this bigotry and the symbolism of the Vampire. Similarly, comedian John Oliver referred to Miller as a vampire in a segment on Last Week Tonight: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JfvWnFbClp0 reinforcing this association within mainstream progressive discourse. Chillingly, Oliver in other segments has played into specific Vampiric tropes when discussing Miller.

These comparisons are not isolated jokes; they are part of a broader pattern. The vampire archetype, secretive, manipulative, and parasitic, resonates because it taps into historical antisemitic stereotypes. The fact that these comments come from progressive media, which typically opposes overt bigotry, underscores how normalized this imagery has become. The invocation of the vampire is less about Miller's politics and more about the ease with which his Jewish identity can be coded through this well-worn cultural shorthand.

As aforementioned, Marvel Comics portrayed Henry Kissinger, the Jewish former U.S. Secretary of State, as a vampire and servant of Dracula. This depiction not only draws on Kissinger's reputation as a shadowy geopolitical strategist but also literalizes the antisemitic trope of the Jew as an undead puppet master pulling the strings behind global events. In the Marvel universe, Kissinger isn't just influential; he's an actual vampire, feeding off the lifeblood of nations in service to a more powerful, immortal overlord.

This portrayal reflects how fiction often amplifies real-world prejudices under the guise of creative freedom. The vampire here is not just a metaphor but an explicit characterization, reinforcing the idea of Jews as inherently connected to dark, supernatural forces. It aligns with historical narratives that cast Jews as conspiratorial, controlling, and inhumanly resilient.

Much of newer media has not evolved past playing into the same tropes. In Marvel Comics, Dracula is often depicted as an aristocratic, highly intelligent manipulator who controls pawns across the world, with him being deeply entrenched in politics and media, akin to antisemitic conspiracy theories of Jewish global influence. Among the servants of Dracula, of course: Henry Kissinger, noted Jew. In Castlevania (Netflix series) Dracula is portrayed as a near-omnipotent ruler with boundless resources, accumulated across centuries. His vast, hidden network of allies from Styria to Japan and ability to project power from afar reinforce the trope of Jewish financial control. His Castle’s ability to teleport mirrors fears of Jewish mobility across borders. The use of ‘Distance mirrors’ in communication and transport similarly reinforce this fear and antisemitic fears of cabal conspiracies.

The vampire myth, often interpreted as a reflection of societal fears surrounding the "Other," can also be examined through the lens of Jewish theological concepts, particularly the Brit Bein HaBetarim. This foundational covenant, described in Bereshit, established an everlasting pact between God and Abram’s descendants. The enduring nature of this covenant, along with its promises of eternal lineage, wealth, and survival through oppression, provides an intriguing framework for understanding how Jewish identity has been mythologized and, at times, demonized through the figure of the vampire.

Genesis 17:7 states: "I will maintain My covenant between Me and you, and your offspring to come, as an everlasting covenant throughout the ages, to be God to you and to your offspring to come." This divine assurance of continuity is a spiritual form of immortality. While individual Jews are mortal, the Jewish people as a collective entity, Am Yisrael, are eternal, bound by an unbreakable covenant that transcends time and geography.

This concept mirrors the vampire’s defining trait: immortality. The vampire, like the Jewish people, endures through ages, unyielding in the face of external threats, perpetually surviving and adapting. However, whereas Jewish endurance is a testament to resilience, the vampire’s eternal existence is often portrayed as both a blessing and a curse, reflecting ambivalent feelings toward longevity and survival against the odds. The antisemitic imagination twists Jewish covenantal survival into something unnatural and menacing: an entity that cannot be eradicated, no matter how fiercely it is hunted.

Genesis 15:14 promises: "But I will execute judgment on the nation they shall serve, and in the end they shall go free with great wealth." This assurance of eventual prosperity has been weaponized in antisemitic stereotypes, framing Jewish success as evidence of hidden influence or malevolent power. Similarly, vampires are frequently depicted as ancient aristocrats hoarding vast fortunes amassed over centuries.

Genesis 15:13 states: "Know well that your offspring shall be strangers in a land not theirs, and they shall be enslaved and oppressed four hundred years." This foreshadowing of the Israelite experience in Egypt prefigures the broader Jewish diaspora experience: perpetual outsiders navigating foreign lands, often subjected to marginalization and suspicion.

The vampire, too, is an eternal outsider, unable to fully integrate into human society, existing on the fringes, hidden yet present. The fear of the “stranger” or the “infiltrator” is central to both antisemitic narratives and vampire mythology. Vampires, like Jews in the diaspora, are depicted as simultaneously visible and invisible, integrated into society yet fundamentally apart from it. This dichotomy evokes anxiety about assimilation and hidden influence and dual loyalty, fears historically projected onto Jewish communities.

Circumcision, the physical mark of the covenant, is described in Genesis 17:13: "They must be circumcised, homeborn and purchased alike. Thus shall My covenant be marked in your flesh as an everlasting pact." This bodily sign of Jewish identity has historically been a source of both communal solidarity and external hostility, fueling antisemitic fascination and demonization.

The focus on Jewish bodies as different, marked, or "other" is reflected in vampire mythology through the vampire's distinctive physical traits: fangs, pallor, and a body that defies natural laws. Moreover, the act of circumcision, often misunderstood and exoticized in antisemitic rhetoric, ties into fears of bodily control and transformation, themes central to vampire lore. Vampires transform their victims through the act of biting, an intimate, invasive process that alters the body permanently, a distorted echo of the covenantal marking.

These tropes and parallels between the Brit Bein HaBetarim and the characteristics of vampires are awfully precise to be coincidental. The vampire myth emerged long after the Bible was written, after the ethnogenesis of Jews, and after these antisemitic stereotypes had developed. Christian authors, well-acquainted with both Jewish texts and Jewish communities, would have drawn from these sources in shaping the vampire archetype. Immortality, wealth, exile, and bodily difference are all elements rooted in Jewish theology and history, twisted into the framework of a monstrous archetype designed to evoke fear and loathing of exactly the people to whom this covenant applies. These tropes draw from historical anxieties about Jewish economic roles in European societies, particularly in contexts where Jews were restricted to specific occupations such as money lending. The vampire, much like the antisemitic stereotype of the "wealthy, influential Jew," is depicted as a manipulator of economies, pulling strings from the shadows. Where the covenant promises divine reward, the vampire myth recasts that endurance as parasitic exploitation.

Understanding the vampire as a cultural construct shaped by antisemitic narratives allows us to see how myths are used to dehumanize marginalized groups. By examining the origins and evolution of these tropes, we can begin to dismantle the prejudices embedded within them, revealing the vampire not as a creature of the night, but as a mirror reflecting the darkest aspects of human history and fear. Given all of that, it should be unsurprising that this is what modern (in a broad sense) antisemitism looks like:

The association of these depictions of Jews and a Mensch like Joe Biden with blood libel should not reuire further explanation. When seen collectively and in the historic context of vampires as an antisemitic political symbol, the persistence of these tropes into modern imagery reveals a troubling continuity. The near seamlessness with which an illustration from Der Stürmer fits into contemporary anti-Zionist “art” underscores that these depictions are part of a long-standing visual lexicon of antisemitic propaganda, adapted for modern political contexts. These images claim to critique policy or personalities but instead resurrect age-old conspiratorial fantasies, transforming Jews and their supporters from people into shadowy, manipulative, and bloodthirsty monsters or their thralls. The past does not just echo in these portrayals; it is repackaged and resold under the guise of contemporary critique, making its ideological lineage all the more insidious.

This reveals an unsettling reality: that antisemitic narratives are so deeply embedded in Western culture that even those who claim to oppose racism, fascism, and xenophobia often reproduce its most virulent forms without hesitation. The vampire, once a Gothic fiction laced with antisemitic anxieties, remains a political weapon. Its imagery resurfacing in modern caricatures of Jewish figures, from world leaders to businessmen to entire communities. These symbols endure because they continue to serve the same purpose they always have: to delegitimize, to dehumanize, and to justify violence. In this way, the myths of the past do not simply persist: they continue to shape the present, lurking beneath the surface of political discourse like the very creatures they invoke.

58 notes

·

View notes

Note

been thinking about this question and hopefully this won't be too awkward to ask. since judaism is itself an ethnicity and religion at the same time, imagine you have ancestors from like idk portugal who converted to judaism centuries and centuries ago and so their descendants are all jewish but don't know about the conversion part. can they call themselves ethnically jewish?

A person becomes part of the Jewish ethnicity when they convert to Judaism. Ethnicity is more than DNA, it's about your peoplehood. As a student of anthropology I honestly don't like how the rise of at-home DNA test kits have put into people's minds their identity is a complicated equation of DNA percentages. People are not math problems. If you were born Jewish you are 100% Jewish. If you converted to Judaism you are 100% Jewish. DNA tests only measure the genes you're more likely to share with certain populations, and even then they're not completely accurate. Ethnicity isn't about blood quantum, at least it shouldn't be.

Here's an example, using myself:

I've never taken a DNA test, and don't intend to, but if I had to guess it would probably give me a result of something like: 58% Ashkenazi Jewish; 25% Northern European; 15% Sephardi Jewish; 2% Northern African.

What does that tell me about my ethnicity? Nothing. It tells me percentages of DNA I have that are most likely shared with certain populations of people from certain geographic regions (haplogroups), but my ethnicity is 100% Jewish and I don't need a DNA test to tell me that, because I know I was born Jewish.

DNA tells you your haplotypes. Peoplehood tells you your ethnicity. And peoplehood is defined by the people themselves.

So yes, the descendents of converts are ethnically Jewish. All Jews are ethnically Jewish.

#jumblr#jewish identity#race vs ethnicity vs haplogroup#dna test#anthropology#ethnicity#ethnoreligion#judaism

485 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Jewish people have always lived in Israel.

Jewish History

Jewish roots

Jewish identity

Now here is how Palestine got its name 👇

Truth Bombs !

History doesn't lie !

Israel was

Israel is

Israel will always be

Israel is the only Jewish nation in the world and they aren't going anywhere !

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jewish intersex: a flag for those who are both Jewish and Intersex!

[ID start

A light blue background. In the center there is a yellow circle, its inside transparent to show the background color. In the circle there is a Star of David in a deep blue.

End ID]

#liom coining#mogai coining#xenogender#mogai post#mogai#mogai blog#mogai flag#mogai gender#mogai term#intersex#jewish mogai#jewish#jewish identity#intersex pride

18 notes

·

View notes

Note

I was told growing up that my mother's mother was raised Jewish and my mother's grandmother and great grandmother were born Jewish, though I was raised atheist. I believed this wholeheartedly and considered myself a ba'al teshuvah - studied Torah, kept kosher, observed yomim tovim, (occasionally) attended services, etc for the past decade. Unfortunately, I recently discovered - very conclusively - this is not the case. There are absolutely no Jews in my ancestry at all as far back as the 1700s. I didn't intentionally lie to my synagogue, my friends, or my coworkers, but I lied nonetheless. I want to talk to the rabbi and ask about conversion, but I'm honestly pretty shaken by the whole discovery and have no idea how to start or what to say. Does anyone have any ideas?

.

#jumblr#ask jumblr#judaism#jewblr#jewish#frumblr#halacha#jewish conversion#conversion to judaism#am i jewish#am i a jew#jewish heritage#jewish identity

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

by Andrew Lapin

JTA — A comic book festival in Vancouver said it has banned an Israeli-American artist because of her past service in the Israel Defense Forces, after apologizing for allowing her to participate this year.

The Vancouver Comic Arts Festival then deleted its statement apologizing for allowing Miriam Libicki to exhibit at the event, which took place earlier this month, after the Canadian Jewish News published an article calling attention to the affair.

According to the news outlet and social media screenshots, the statement did not name Libicki but referenced her and her work and said she would not be allowed in the festival in the future.A Stop to the Trucks - The Times of IsraelKeep Watching

“The concerns regarded this exhibitor’s prior role in the Israeli military and their subsequent collection of works which recount their personal position in said military and the illegal occupation of Palestine,” said the “Accountability Statement,” posted to Instagram.

The statement went on to say her appearance was the result of “oversight and ignorance” and that it “fundamentally falls in absolute disregard to all of our exhibiting artist’s [sic], attendees and staff, especially those who are directly affected by the ongoing genocide in Palestine and Indigenous community members alike.”

In her own statement, Libicki, who explores Jewish identity in her work, called the ban “illegal” and said it was “bad for all artists of all political orientations and backgrounds.” She added, “I have consistently, publicly been pro-peace” and supportive of the establishment of a Palestinian state.

“Because of the vulnerable populations I work with, I prefer not to discuss my specific political views in public,” she wrote in a statement shared on Wednesday by Jesse Brown, a Canadian Jewish publisher and journalist. “I believe all policing of artists’ personal identities and nationalities is wrong.”

But after the CJN article was published on Wednesday, the festival deleted its “Accountability Statement.” It did not immediately respond to a Jewish Telegraphic Agency request for comment.

68 notes

·

View notes

Text

Queen Esther

Artist: Hugues Merle (French, 1822–1881)

Date: 1885

Medium: Oil on canvas on masonite

Collection: Private Collection

Queen Esther

In the biblical book named after her, Esther is a young Jewish woman living in the Persian diaspora who finds favor with the king, becomes queen, and risks her life to save the Jewish people from destruction when the court official Haman persuades the king to authorize a pogrom against all the Jews of the empire. Written in the diaspora in the late Persian/early Hellenistic period (fourth century B.C.E.), the Book of Esther deals with the enduring issues of preserving Jewish identity and ensuring survival amid cultural pressures and hostile enemies in a foreign land.

#portrait#queen esther#old testament#hugues merle#french painter#book of esther#19th century art#jewish woman#jewish identity#christianity#christian art#biblical art#oil painting#artwork#fine art#drapery#curtains#veil#jewels#french culture#french art#european art#19th century painting

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

an personal narrative speech on israel i wrote for school

note that this was written for an audience who mostly doesn't know anything about Israel.

essay below if the images are not working for you/you have a screen reader

I was at Hebrew School, my legs against the cold plastic chair of the over-air conditioned synagogue basement, and I was bored. My eyes fell over the posters on the wall — the Rambam’s ladder of Tzedakah, common Hebrew words, and a large map, almost my size, of Israel.

I had looked at this map so many times, so many days. But I had never really looked at it. My eyes traced the coastline … Ashkelon, Ashdod, Tel Aviv, Haifa, Akko. In the center, Jerusalem. At the bottom, Eilat. And at the very top, the little tip wedged between Lebanon and the Golan, Kiryat Shmona.

Israel is a small country, about the size of New Jersey, located in the Middle East. It borders the Mediterranean Sea and is home to almost 10 million people. It is the only country with a Jewish majority, but it also has large Arab and Druze minorities. Many holy sites for the main three Abrahamic religions — Judaism, Christianity, and Islam — are located in Israel.

As a kid growing up in the Jewish community, Israel was a common topic of conversation. We had Israelis come and visit us, a lot of us had family there, and most people we knew had visited Israel. We learned the Hebrew words for things like ice cream (glidah) and dog (kelev). We used the Hebrew pronunciation of words like hummus (huh-miss), which we said houmous (choo-moose).

We celebrated the new year of the trees in January (which doesn’t really make any sense in [redacted]) and we prayed for rain during services.

Really, whether or not we said it, we knew, we could feel, that everything we did… our prayers, our traditions, all traced back to Israel.

But here’s the weird thing… I’ve never been to Israel. I’ve never even really been close to Israel. I’ve never swum at the beach in Tel Aviv, never walked the cobblestone streets of Jerusalem, never felt the heat bearing down on me as I climbed Masada. I’ve never placed a folded up prayer in the Western Wall, never smelled the aromas of spices and herbs at a shuk, never read the ancient names on the graves at the Mount of Olives. And even though I’ve never stood on the grounds my ancestors stood on, put my hands where they did, and breathed the air they breathed, I can still feel these places. They’re in my DNA… literally.

The traditions of the Jewish community connect me to my roots. When the kingdom of Judah, where Jews are from, located in modern day Israel, was taken over by the Romans, the Jews were forced out of our homeland, and we became dispersed throughout the word. As Rudy Rochman, an Israeli activist, says, Judaism “is a portable suitcase of a native people's identity that was created to preserve who they were after their forceful displacement from… Israel.” Every Jew throughout the world, no matter where we are; in the United States, Israel, or France, continues to carry this suitcase that connects us back to where we came from.

Today, when I celebrate Jewish holidays, I know there are people halfway around the world doing the same things I’m doing. They sing the same prayers, eat the same foods, and participate in the same traditions. They are all drawing from a suitcase that looks a lot like mine.

Today, about half of the world’s Jews live in the United States, and about half live in Israel. My traditions and culture connect me to all Jews, but my traditions also tie me to that land. I know that if I wanted to, or if I needed to, I could move to Israel. I could become a part of that country — the country I already love so much.

But today, there are a lot of challenges with loving Israel — at least in the sense of the modern nation state. Currently, Israel is locked in a conflict with Palestine — a conflict you’ve probably heard about in the news — that has been going on for over a century. Today, neither Israel nor Palestine are completely innocent or guilty in this conflict. Israel, as much as I love it and feel connected to it, has done a lot of things I disagree with. And it’s hard for me to love Israel when I constantly see things in the news that make me facepalm, and when I know that the Israeli government is doing things I don’t agree with.

I love Israel. But love is complicated. It’s not black and white. I love Israel as my homeland, the place that birthed my people. And that love is paradoxical. I accept it as it is now, and I want it to get better.

But now that I think about it, I realize that love means caring enough for something that you’re willing to work for it. Love means believing that peace, and a better future, is possible. Love means that a better way will be found. Because you don’t just walk away from something you love when it doesn’t meet your expectations.

So someday, I will go to Israel, and when I swim at the beach in Tel Aviv, walk the cobblestone streets of Jerusalem, and feel the heat bearing down on me as I climb Masada — I’m not going to be thinking about news headlines or military operations. I’m not going to be thinking about disappointment and failures. I’m going to be thinking about the three thousand years of history and tradition that led me back to the land of my ancestors.

#jumblr#jewish#chana talks#judaism#israel#am yisrael chai#i stand with israel#antisemitism#essay#personal essay#personal narrative#jewish identity

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

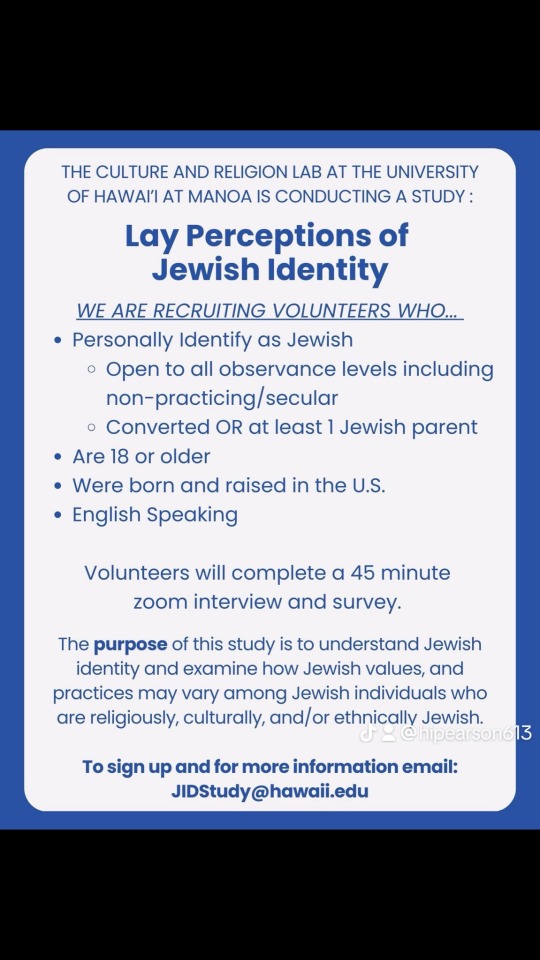

I am currently collecting data for my PhD dissertation project looking the lay perceptions of Jewish identity. This is the first study of 4 and I am looking for volunteers to chat with me about their Jewish identity!

Anyone who is 18+, born and raised in the United States, and identifies as Jewish (whatever that means to you) is eligible regardless of level of observance!

If you are interested, feel free to reach out to me directly or email [email protected]. If you are not interested but would be willing to take a survey down the road, let me know and I can be sure to include you on my survey email list when studies 2 and 3 are ready to go.

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

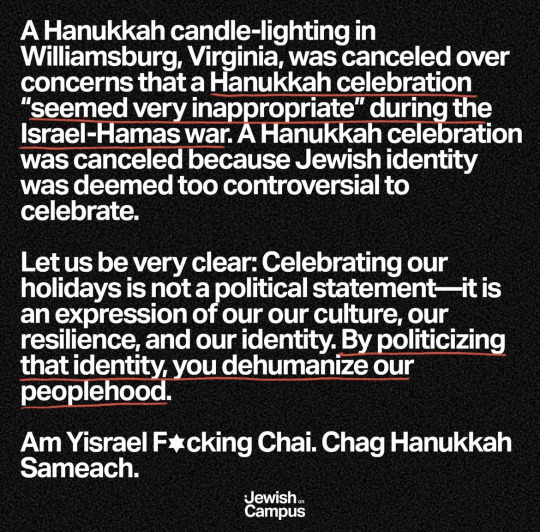

Although times are dark right now, we can all be lights. חג חנוכה שמח 🕎

#am yisrael chai#עם ישראל חי#jewish#jewblr#actually jewish#judaism#hanukkah#israel#jewish identity#happy hanukkah#Hanukkah Sameach#חנוכה שמח

110 notes

·

View notes

Text

instagram

#jewish identity#survival#history#statistical improbability#hell yes this is us#israblr#jumblr#positivity boost#Instagram

7 notes

·

View notes

Note

Apologies if this questions sounds stupid or ignorant, but I'm genuinely trying to educate myself. Can Jews be Jewish *and* a different race, so does a Jewish identity supersede another racial identity? Just wondering because a lot of Ashkenazi Jews I know (in real life or online) push back against the idea that they are white. I've heard European Jews say that they are not considered white, do not have white privilege, etc. so they are not white. But I've also seen a lot of Jews of color identify with both their Jewish identity and their "racial" identity (ravenreveals on Instagram explains how she identifies as Black *and* Jewish, and one of my friends identifies as an Asian Jew). So is there a reason many European (Ashkenazi?) Jews don't identify as white/identify as only Jewish? I'm sorry if this is offensive in any way, this isn't my intent :)

Sorry it took me so long to answer, I am swamped with asks haha

Yes, it's possible to be Jewish and a different race, as Judaism isn't a race, but an ethnoreligion, or even better described as a tribal nation.

Now, first I'm going to push back on you equating European with Ashkenazi. Ashkenazi is a specific term referring to Jews whose ancestors settled in the Rhine valley after the Roman expulsion from Judea. Many of these Jews eventually migrated eastward to Eastern Europe and Westward to British Isles, while others stayed in the Rhine valley region. But not all Jews whose ancestors settled in Europe are Ashkenazi.

There are Sephardi Jews, obviously, whose ancestors settled in the Iberian peninsula following the Roman expulsion, and then later migrated to North Africa, Northwestern Europe, Eastern Europe, and West Asia following the Spanish and Portugese inquistions.

There are also Italki Jews in Italy and Romaniote Jews in Greece, all of which are unique communities of Jews whose ancestors settled in Europe and who are not Ashkenazi.

Additionally, not all Ashkenazi Jews are racialized as white. Ashkenazi does not refer to your race, but rather who your ancestors are and/or what community traditions you follow. There are Ashkenazi Jews of every race.

The reason why lots of what-you-perceive-as-white Jews don't identify as white is because Judaism precedes the modern constructs of race (yes, race is a construct, not an immutable science) and because whiteness is highly subjective and fluid, just as non-whiteness is. Because race is a construct, which race a person is perceived as varies by where they are and by which people they are around.

Jewish "whiteness" is also conditional- and as Jews we don't like to leave ourselves vulnerable to shifting statuses. Jewish "white-passing-ness" can also be a tool of violence, either by denying the racial reality of antisemitism, or by being 'proof' that Jews are shape-shifting inflitrators of the white race. Hitler's Final Solution was total extermination precisely because he feared many Jews would pass as white and spread their Jewish blood among the Aryans, and so the total extermination of Jews was deemed as necessary, like one would exterminate a parasite.

This of course doesn't mean that no Jew has ever had access to the privilege afforded to whiteness. In the post-Holocaust era, many Jews have tried to successfully assimilate into whiteness to access even a little bit of privilege in order to protect themselves. I'm not going to lie and say that if I was pulled over at a traffic stop, my lighter complexion wouldn't give me more grace at the hands of the police officers than someone with darker skin would. Because yes, sometimes I am racialized as white and therefore access the privilege of whiteness.

But that doesn't mean I don't feel deeply uncomfortable when I'm filling out a form and the only options for race and even ethnicity are "white", "black", "hispanic", and "asian". Because while at the end of the day I'll check "white", it's only because I don't want to be accused of fraud (even though Middle Eastern or just Jewish would fit me better, but that's not an option). But that's just me. Some Jews are fine calling themselves "white Jews". Two Jews three opinions and all.

Someone introduced me to the phrase "racialized white/black/etc" a few years ago, and I think it makes much more sense. Because race is entirely dependent on perception and how others racialize you. I am not White, but sometimes I am racialized as white. Other times, I am racialized as "not-quite-white-but-we-don't-know-how-to-categorize-you-so-we're-just-going-to-try-and-guess-and-ask-wildly-invasive-questions".

At the end of the day, call Jews what they want to be called, and don't try and push labels on us. If a Jew doesn't want to be called white, don't call them white. Because race, ethnicity, religion, and all that is complicated, and Judaism predates all of that, so naturally Jews are going to have mixed feelings about it all.

#jumblr#race vs ethnicity vs haplogroup#judaism#jewish identity#jewish experience#if jew know jew know

276 notes

·

View notes