#More Fossil Fragments

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Video

youtube

Dinosaur Zoo Tycoon - More Fossil Fragments

#youtube#Dinosaur#Zoo#Tycoon#More#Fossil#Fragments#Roblox#Red_Wolf16GH#Dinosaur Zoo Tycoon#More Fossil Fragments

0 notes

Text

It's National Dinosaur Day in Australia!

The 7th of May is officially National Dinosaur Day! While our fossil record might be a bit patchier than some continents, there are still plenty of excellent dinosaurs that have been found from the Mesozoic and Cenozoic, and here's a few of them!

Australovenator wintonensis

(art by Scott Reid)

Probably the most iconic Australian dinosaur, Australovenator was a large theropod with massive hooked hand claws from the Winton Formation. It was the first megaraptoran identified in Australia, a group of theropods that we now know were widespread and successful across the southern hemisphere in the Cretaceous!

Kunbarrasaurus ieversi

(art by Ashley Patch)

One of the few armoured dinosaurs found in Australia, Kunbarrasaurus ieversi is known from a beautiful full-body fossil from the Allaru Formation that preserves the armour plates in their life positions!

Dromornis stirtoni

(art by @knuppitalism-with-ue)

The Dromornithidae (also known as mihirungs) have a roughly emu-like body plan but are actually a member of the group Anseriformes, closer to waterfowl! Dromornis stirtoni from the Alcoota Fossil Beds is the largest bird to ever live in Australia that we know of, weighing around half a ton.

Genyornis newtoni

(art by Jacob Blokland)

The latest-surviving mihirung, Genyornis was described in 1896 but the first well-preserved skull fossil of this quarter-ton bird was only published last year by Phoebe McInerney, who I actually know! I also got to do a little bit of work on the second skull of Genyornis in the lab earlier this year so it's not only a cool animal but one I'm especially personally fond of!

Fostoria dhimbangunmal

(art by James Kuether)

Fostoria is a mid-sized iguanodontian that's known from Australia's only ornithischian bone bed, an extremely rare find for a continent whose Mesozoic dinosaur fossils tend to be pretty badly scattered and fragmented. The bones of multiple individuals were found together in the opal fields of the Griman Creek Formation, and the bones themselves had been opalised!

Australotitan cooperensis

(art by Vlad Konstantinov)

Known simply as Cooper for 15 years, Australotitan finally got a full description in 2021 which marked it out as not only Australia's biggest dinosaur but on the scale of some of the largest known sauropods in the world!

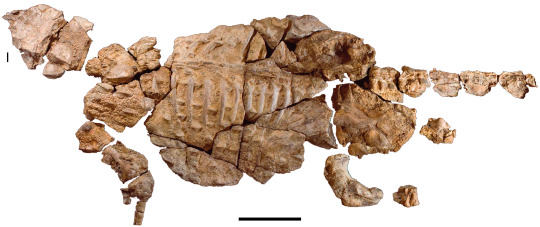

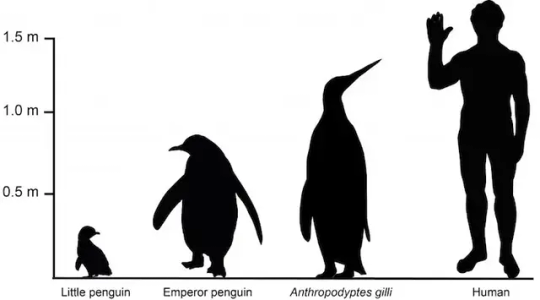

Anthropodyptes gilli

(art by,,, Travis Park? I think? this one was a Struggle)

Today the only penguin native to the mainland is the little blue penguin, but in prehistory there were much larger penguins around! They're only known from fragmentary remains in Australia, but species like Anthropodyptes gilli and Pachydyptes simpsoni grew larger than modern emperor penguins!

Diluvicursor pickeringi

(art by Peter Trusler)

One dinosaur we seem to have heaps of in Australia (as with the rest of the world) is small ornithischians. These sprinty little guys are almost ubiquitous in Mesozoic ecosystems, and in Australia Diluvicursor is one of the more complete examples, with a holotype fossil from the Eumeralla Formation that preserves the tail and foot bones.

Phoenicopteridae (Flamingos)

(art by Astrapionte, featuring from left to right: Phoeniconaias proeses, Phoenicopterus copei, Xenorhynchopsis tibialis and minor, Phoenicopterus novaehollandiae, and Phoeniconotius eyrensis)

Last fun fact about Australia, did you know we used to have flamingos until very recently? The flamingo fossil record in Australia is pretty limited, but we know they lived here from the Oligocene all the way to the Pleistocene, when they were likely wiped out by environmental change as the centre of the continent dried up. Phoeniconotius eyrensis seems to have been one of the largest flamingo species, likely heavier than the modern greater flamingo!

294 notes

·

View notes

Text

Round 3 - Reptilia - Galliformes

(Sources - 1, 2, 3, 4)

Our next order of birds are the ancient Galliformes, known collectively as “landfowl”. The order contains five families: Megapodiidae (megapodes), Cracidae (“curassows”, “guans”, and “chachalacas”), Odontophoridae (“New World quails”), Numididae (“guineafowl”), and Phasianidae (“pheasants”, “grouse”, “partridges”, “junglefowl”, “turkeys”, “Old World quail”, and “peafowl”).

Many gallinaceous species have rounded bodies and blunt wings. They are typically skilled runners and escape predators by running rather than flying, only using their wings to fly up to trees to roost or escape a predator when cornered. Galliforms are anisodactyl, with three toes that point forward and one that points backward, and some of the adult males also grow spurs that point backwards, which they use for fighting. They are usually omnivorous, feeding on fruits, seeds, leaves, shoots, flowers, tubers, roots, insects, snails, worms, lizards, snakes, small rodents, and eggs, depending on species. Galliforms are mainly nonmigratory. They can be found worldwide in a variety of habitats, including forests, deserts, and grasslands.

Galliforms have diverse mating strategies: some are monogamous, while others are polygamous or polygynandrous. Males of many galliform species are more colorful than the females, with often elaborate courtship behaviors that include strutting, fluffing of tail or head feathers, and vocal sounds. They breed seasonally in accordance with the climate and lay 3 to 16 eggs per year in nests built on the ground or in trees. Females usually brood the eggs, except for the megapodes.

Fossils of galliform-like birds originate in the Late Cretaceous. These ancestors of the galliformes were a niche group of dinosaurs that were toothless and ground-dwelling. When the asteroid impact killed off all non-avian dinosaurs, as well as the dominant birds, Enantiornithes, the ancestors of galliformes were small and lived in the ground which protected them from the blast and ensuing destruction, becoming the new dominant birds along with waterfowl. Modern galliformes originated in the Eocene, around 55 million years ago.

Propaganda under the cut:

The megapodes are unique among birds for their nesting behavior. Instead of sitting on their eggs, they build large mounds of decaying plant matter over them. The male will attend the mound, adding or removing litter to regulate the internal heat while the eggs develop. The Maleo (Macrocephalon maleo) (image 2) is most known for burying its eggs in a hole in the sand, allowing the eggs to be incubated by geothermal or solar energy heating up the sand. They leave the eggs once they are laid, and never return. Megapode chicks are the most precocial of all birds, digging their way out of the nest or ground with their powerful claws. They hatch fully feathered and active, already able to fly and live independently from their parents.

The Australian Brushturkey (Alectura lathami) is the largest living megapode. It is sometimes considered a pest, as it may take mulch for its nest or rake up gardens searching for food. However, it is fully protected in Queensland and New South Wales, and harming one of the unique birds can result in a fine of up to 3000 penalty units ($483,900), or two years imprisonment.

The endangered Horned Guan (Oreophasis derbianus) looks like this:

(source)

The critically endangered Blue-billed Curassow (Crax alberti) once used to range all across Northern Colombia, but is now reduced to small, fragmented populations, with the only known viable population existing in the Serranía de las Quinchas area in the Magdalena Valley. Its population is estimated to be fewer than 1,500 mature individuals. They are threatened due to habit loss, occurring from widespread use of herbicides by the Colombian government. Forests have also been cleared for agriculture, livestock, oil extraction, and mining. Around 98% to 99% of Blue-billed Curassow habitat has been lost. The birds are also hunted, and studied populations are not estimated to survive another 100 years if hunting continued. Thankfully, some reserves have been created and captive breeding has been successful. Now time will tell if the Blue-billed Curassow can be saved.

The iconic California Quail (Callipepla californica) (image 4) was selected as the state bird of California in 1931. They are highly social birds, gathering in small flocks known as "coveys". One of their daily communal activities is dust bathing.

One of the most well-known quails in North America, recognized by their characteristic whistling call, is the Northern Bobwhite (Colinus virginianus). The Northern Bobwhite is considered near threatened, and their populations have declined by around 85% since 1966. One subspecies, the Masked Bobwhite (Colinus virginianus ridgwayi), is endangered, and have been extirpated from Arizona twice. The decline is mainly due to changes in how land is managed. Northern Bobwhites depend on early successional habitat, that requires fire or some other disturbance to be revitalized. These habitats have the forbs, legumes and insects that bobwhite need for food and the heavy or brushy cover for nesting, brooding and safety. To help reverse bobwhite declines, NRCS (Natural Resources Conservation Service) is working with private landowners to manage their land for high-quality habitat in grasslands and pine savannas.

The Helmeted Guineafowl (Numida meleagris) was domesticated in Western Africa, and there is evidence that Domestic Guineafowl were present in Greece by the 5th century BC. The birds are kept for meat and eggs, but today are mostly kept for pest control, as they are avid eaters of ticks, wasps, and other insects. They are also kept as guard animals with other livestock, as they give a loud, shrill warning call when predators are seen. Feral populations descended from domestic flocks are now widely distributed and occur in the West Indies, North America, Australia, and Europe.

Unusually for galliforms, the Crested Partridge (Rollulus rouloul) will feed its young bill-to-bill, rather than teach it to peck at the ground, and both parents engage in this feeding behavior.

The Tragopans are also known as “horned pheasants”, due to the male’s courtship display in which he will inflate large, vividly colored horns on his head and a lappet on his chest.

The Himalayan Monal (Lophophorus impejanus) is the national bird of Nepal, and the males are one of the most colorful birds in the world, covered in patches of iridescent blue, purple, green, and red.

The Willow Ptarmigan (Lagopus lagopus) is the state bird of Alaska and has gained recent internet notoriety for its “awebo” call. They are known for changing color from brown to white in the Winter, and have remained relatively unchanged since the Pleistocene.

The largest galliform is the Wild Turkey (Meleagris gallopavo) which may weigh as much as 14 kg (30.5 lb) and may exceed 120 cm (47 in).

The Western Capercaillie (Tetrao urogallus) is a large grouse species, and is extremely sexually dimorphic, with males being nearly twice the size of females. Males are known for their combative behavior during the breeding season, even challenging and chasing off humans who enter their territory.

The critically endangered Edwards's Pheasant (Lophura edwardsi) may be extinct in the wild. The pheasants declined due to deforestation and hunting, but a major blow to their population was the use of defoliant herbicides used during the Vietnam War. The herbicides were sprayed by the United States to deprive the Vietnam soldiers of food crops and/or hiding cover. They also deprived the pheasants of food and shelter. There have been no confirmed sightings of a living individual in the wild since 2000. In 2018, a photograph of a dead female Edwards's Pheasant was taken near Phong Điền Nature Reserve, providing evidence that the pheasants may persist in the wild on the reserve. Thankfully, the pheasants breed readily in human care, and assurance populations are being prepared for release back into the wild.

The Domestic Chicken (Gallus gallus domesticus) was domesticated in Southeast Asia around 8,000 years ago, from the Red Junglefowl (Gallus gallus). They are kept for meat, eggs, as pets, and for cockfighting. Their domestication has led to them being the most widespread and successful birds in the world, with a total population of 26.5 Billion as of 2023, and an annual production of more than 50 Billion birds.

The smallest galliform is the King Quail (Synoicus chinensis), which is around 12.7cm (5in) long and weighs 28–40 g (1–1.4 oz).

121 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mammoth Tusk Discovered in Mississippi

Scientists in Mississippi announced a major fossil discovery in the state!

According to the Mississippi Department of Environmental Quality (MDEQ), the agency’s Mississippi State Geological Survey scientists received a message about a the discovery made by Eddie Templeton, an avid artifact and fossil collector. Templeton was exploring in rural Madison County earlier this month when he stumbled upon what appeared to be a portion of an ice-age elephant tusk exposed in a steep embankment.

Mississippi was home to three Proboscideans during the last ice age: Mastodon, Gomphothere, and the Columbian mammoth. All three possessed ivory tusks.

Officials said Mastodons are the most common Proboscidean finds in Mississippi. Mammoths, which were related to modern elephants, are far less common finds in Mississippi.

When Templeton and the State Survey paleontological team arrived to the fossil site, they found the fossil tusk in amazing condition and was only partially exposed just above the water under a bluff in the alluvium of a small drainage. It was suspected based on the strong curvature of the massive tusk that they were dealing with a Columbian mammoth and not that of the more common mastodon. Officials said this would be the first of its kind for the area.

The team was able to carefully remove the clayey sand from around the tusk to expose the seven-foot long fossil. The tusk had been deposited entirely intact. MDEQ officials said most fossil tusk ivory found around the state are just fragments and most are likely to be attributable to the more common mastodon.

The fossil was taken to the Mississippi Museum of Natural Science in Jackson for further curation and careful study. It was confirmed by a museum paleontologist as belonging to a mammoth.

Officials said the discovery offers a rare window into the Columbian mammoths that once roamed Madison County along the Jackson Prairie of central Mississippi. Columbian mammoths were much larger than the infamous woolly mammoth that roamed the colder, more northern regions of North America. They grew up to 15 feet at the shoulder and could weigh more than 10 tons.

#Mammoth Tusk Discovered in Mississippi#Madison County#mammoth#Columbian mammoth#Gomphothere#Mastodon#fossil#paleontology#paleontologist#archeology#archeolgst#history#history news

291 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello! Hope you're doing well. Love your work! Can I request something slightly.. Maybe confusing?

Idk why but I've always felt that Yoongi and Namjoon have the potential to be attracted to similar people, given their ideologies and personalities. So what happens when they meet reader organically and feel drawn towards them?

I am not envisioning a love triangle per se, but only the illusion of one. Where both grow closer to reader but with namjoon, it indeed is just a solid friendship. Lovestruck but in denial Yoongi doesn't see it that way necessarily. At least initially. Maybe some angst there.

Therefore despite the reader showing interest back, it takes our honey boy a minute to get there, and finally it's all sorted. Yoongi and reader end up together and all their friends are happy for them!

Cold Storage: An Archive of Imperfect Notes

Pairings: Min Yoongi x Archivist!Reader (slow burn), Platonic Kim Namjoon x Reader Rating: R (M) Genre: angst, romance, hurt/comfort, fluff Warnings: alcohol use (whiskey), emotional confrontations (themes of self-doubt, fear of artistic irrelevance), mild language, jealousy, kissing (non-explicit) Word Count: ~ 3k

Description: As HYBE’s archivist, you’re a keeper of ghosts - demos, coffee-stained lyrics, and the jagged edges of artists’ past selves. But when Min Yoongi starts haunting the archives to resurrect his old mixtapes, his obsession with the boy he used to be collides with the man he’s become. Between debates about Rilke, Camus, and the stains on his notebooks, you’ll learn that some wounds outlive the knife… and some hearts only thaw in the cold.

💌 Reply:

Hi love! 💜 First off - THANK YOU for this brilliant request (and your kind words, my heart 🥹). I hope you don’t mind that I spun this into a full imagine/fic — your concept of Yoongi and Joon’s parallel pulls and the “illusion” of a triangle hit me like a TRUCK. As a Yoongi ult (he’s my first/last/always 🐱) and Namjoon bias-wrecker, I vibrated at the idea of their dynamic clashing over someone who challenges them - god, I wish I could thank you enough (you scratched my brain) I kept your vision sacred: no real triangle, just Yoongi’s honey-coated denial, Joon’s platonic muse vibes, and the angst of two artists fearing too much vulnerability (at least in my mind). Also, the others teasing Yoongi? I couldn't NOT do it If this isn’t what you pictured, I’ll happily tweak, but I hope it gives you that slow-burn, you deserved. Thank you for trusting me with this gem. Now go feed your brainrot, legend. 🖤 – c – 💜

Cold Storage: An Archive of Imperfect Notes

Cold Storage: An Archive of Imperfect Notes

Prologue: The Quiet Before the Storm

The archives room at HYBE was a cathedral of silence, if silence could hum.

You liked it that way; the steady whir of climate-controlled servers, the faint tang of aged paper clinging to your fingertips, the way dust motes drifted like static in the blue-tinted dark. Here, in the belly of the iconic building where music went to hibernate, you were more archaeologist than archivist. Unearthing demos from 2013 felt like brushing silt from fossils, each lyric sheet was a bone fragment of who BTS used to be.

You’d taken the job for the anonymity. Artists came to you as ghosts, through track lists scrawled in Sharpie, voice memos buried in hard drives, the occasional coffee ring staining a producer’s notes. They rarely came in person.

Until today.

The Catalyst

The door hissed open at 3:47 PM. You didn’t look up, fingers skating over the spine of a 2014 lyric journal. “If you’re here for the Dark & Wild masters, they’re digitizing in Bay 6.”

“Not here for Bang PD’s old angst,” a voice drawled. Dry, low, lacquered with a Daegu rasp. “Looking for mine.”

Your head snapped up.

Min Yoongi leaned against the doorframe, sleeves rolled to his elbows. His face was all angles under the archival LEDs. his sharp jaw, sharper eyes. You’d seen him before, of course. In hallways. Through the frosted glass of Studio 4, in the practice rooms... Never here, where the past was kept under lock and humidity controls.

“Am producing D-3,” he said, pushing off the frame. “Ten-year reissue. Need the raw stems. And the notebook I used back then. The black one.”

You blinked. “The one where you wrote ‘I want to scream but my throat is a cemetery’?”

His eyebrow twitched, he seemed impressed for a second. “…Yeah.”

You stood, chair screeching. “Physical copies are in Cold Storage. Digital’s accessible if you...”

“Want the physical.” He crossed his arms. “Need to see the… stains.”

Ah. The coffee spills, crossed out words - rewritten a hundred times, whatever sins of sentimentality survived a decade. You nodded, turning toward the steel vault door.

The archives chose that moment to spit out Kim Namjoon.

He materialized between shelves like a philosopher-king misplaced by time, hair tousled, glasses smudged. “Hyung? What’re you...”

“My mixtape’s getting a facelift,” Yoongi said, not taking his eyes off you. “You?”

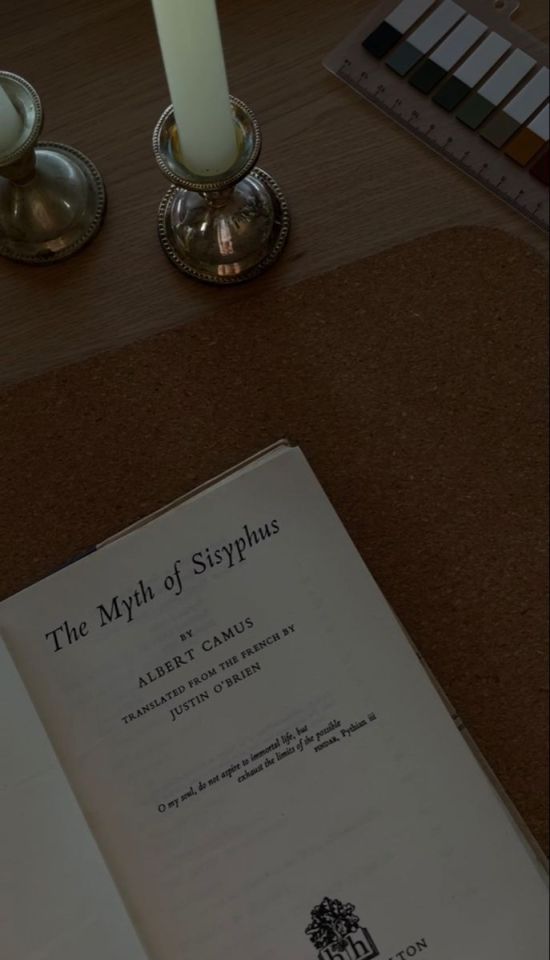

Namjoon hefted a dog-eared copy of The Myth of Sisyphus. “Preparing speech on art as resilience. Need more Camus. And… something that doesn’t sound like a TED Talk.” He grinned, dimples cratering. “Help?”

You snorted. “Camus is a TED Talk. 1942 edition.”

Namjoon’s grin widened. “Then give me the director’s cut.”

Yoongi cleared his throat. Loudly. “Cold Storage?”

“Right.” You led them deeper into the archives, fluorescent lights flickering like a heartbeat monitor. Yoongi’s shadow loomed over your shoulder; Namjoon’s fingers trailed the shelves, dislodging years of dust.

The vault door groaned open. Yoongi stepped into the 12°C chill like a soldier entering a trench.

“Box S-13,” you said, gloved hands lifting a battered container. Inside lay the notebook, the pages warped, edges singed. “Handle with care. Literally.”

He took it like a relic. For a moment, his mask slipped, lips parted, eyes soft and startled, as if meeting a ghost. Then he sniffed. “Nostalgia’s a scam. This…” He flicked a page. “Kid was an idiot.”

You tilted your head. “Or you’re scared he’s smarter than you now.”

Yoongi froze.

Namjoon coughed; badly hiding a laugh.

“Growth isn’t a diss to who you were,” you continued, pulling a crate of Camus essays for Namjoon. “Just proof you survived.”

Yoongi’s gaze cut to you, calculating. “You psychoanalyze all the artists, or just the ones who peaked in 2014?”

“Only the ones who leave burn marks on their notebooks.” You nodded at the charcoal smudges on his thumb.

Namjoon burst out laughing. “Oh, I like her.”

Yoongi didn’t laugh. But his lips quirked, brief and begrudging. “Whatever. Thanks.” He turned to leave, then paused. “…Kid me. You think he’d hate me now?”

The question hung in the frozen air.

You considered the man clutching his past like a grenade. “He’d pity you.”

Yoongi’s brow furrowed.

“For thinking you had to choose between him and who you are now.”

For a heartbeat, the vault hummed with unsaid things. Then Yoongi huffed, tucking the notebook under his arm. “Tell Cold Storage to chill less. It’s fucking arctic in here.”

He left.

Namjoon lingered, thumbing through Camus. “‘The struggle itself toward the heights is enough to fill a man’s heart,’” he read aloud. Then, softer: “You believe that? That art outlives the artist?”

You handed him a first-edition Rebel. “Depends. What if the artist wants to fade? To let the work breathe without their shadow?”

He stilled, eyes narrowing behind smudged lenses. “…Are you always this dangerous?”

“Only to philosophers who quote dead Frenchmen at me.”

Namjoon’s laugh echoed off the vault walls. “Noted. But fair warning...” He leaned in, mock-conspiratorial. “Yoongi-hyung’s gonna be back. He hates losing debates.”

“Not a debate. A fact.”

“Even worse.” He winked, tucking the book under his arm. “Thanks, archivist.”

You watched him leave, unaware of the eyes burning into your back from the security feed in Studio 4... Yoongi, rewinding the footage, pausing on your smirk.

On the desk, his old notebook lay open to a scribbled line: I want to die - I want to live.

He hit replay.

The Dance

The HYBE cafeteria at midnight was a liminal space, flickering vending machines, the scent of stale coffee, and the ghost of Jungkook’s laughter echoing from a meme video left playing on a tablet. You sat hunched over a dog-eared Rilke collection, blue-light glasses slipping down your nose as Namjoon paced, reciting draft lines like incantations.

“Art as… a rebellion against entropy,” he muttered, raking a hand through his hair. “No, too clinical. Art as... shit, what’s the equivalent for ‘intergenerational dialogue’?”

You tossed him a chocolate bar from your bag. “Try 유산 (legacy). Or 대화 (conversation). Depends if you want your audience to weep or nap.”

He caught it, dimples flashing. “Why not both?” Collapsing into the chair across from you, he ripped the wrapper with his teeth. “Help me murder this paragraph. It’s got three metaphors and zero soul.”

You leaned over his notebook, red pen slashing through a convoluted analogy about “sculpting time.” “Camus would disown you. Keep it raw. Like your ‘My heart was filled with straight lines only’ line in Trivia: Love.”

Namjoon’s eyes lit up. “You know that song?”

“I archive your old journals. You wrote that lyric after spilling green tea on Hegel.”

He barked a laugh, loud enough to startle a passing cleaner. “Okay, archivist. What’s raw but profound?”

You scribbled in the margin: “Art isn’t a relic... it’s the wound that outlives the knife.”

Namjoon stared, then slowly grinned. “…I’m stealing that.”

Yoongi found you two days later, arguing over the pronunciation of “Schwere” (heaviness) in Rilke’s “Archaic Torso of Apollo.”

“It’s sh-veh-reh,” you insisted, slamming a German dictionary on the archives desk. “Not shuh-wear. You’re butchering the Schmerz (pain).”

Namjoon leaned back, smug. “Hyung, back me up. It’s about feeling, not grammar.”

Yoongi hovered in the doorway, a box of 2015 demos under his arm. His black sweater rode up slightly as he shifted, frowning. “Why’s Rilke in my studio?”

“Speech,” you said, not looking up. “He’s romanticizing existentialism again.”

Namjoon tossed a crumpled post-it at Yoongi. “They’re ruthless. Tell them schwere (heaviness) is subjective.”

Yoongi caught it, squinting at the scribbled lines. Art isn’t a relic - it’s the wound that outlives the knife. His jaw twitched. “Sounds like a D-2 B-side.” He dropped the demos on your desk. “Need these scanned. And the notebook from last week.”

You frowned. “You’ve requested that notebook three times.”

He met your gaze, unblinking. “I like the stains.”

His visits became clockwork.

Tuesdays at 4 PM

“The 2016 tour schedules. For… chronology.”

Thursdays at 7 PM

“Original First Love lyrics. The ones with the coffee rings.”

Each time, he lingered; arguing over tracklists, scoffing at your critiques, circling back to debates about his old self.

“Reissue Track 5 should be The Last pt.2 ,” you said one evening, sliding the old demo across the desk.

Yoongi stiffened. “Too raw. People won’t get it.”

“Or you’re scared they will.”

He leaned forward, palms flat on the desk. The small 7 on his shoulder peeked out, a silent confession. “You think you know me because you’ve digitized my angst?”

“I think The Last saved someone once. Maybe you.”

He held your stare, the air thickening like storm clouds. Then he snatched the demo. “Track 5 stays Agust D - WHO?.”

But the next day, the tracklist update included The Last pt.2.

It was Namjoon who shattered the détente.

You’d met him in the cafeteria again, debating the ethics of AI-generated art. His laugh, warm and booming, carried across the room as you mocked his “algorithms can’t cry” argument.

Yoongi walked in just as you tossed a sugar packet at Namjoon’s chest.

“ So if a robot writes a love song,” you said, grinning, “...is it plagiarism or progress?”

Namjoon caught the packet, eyes crinkling. “Depends if it’s got soul. Like your Rilke edits., but probably not.”

Yoongi froze, tray in hand. His knuckles whitened around a cup of bitter black coffee.

Of course it’s Joon.

He left without a word.

That night, Yoongi stormed the archives.

“Seesaw,” he demanded, slamming a hand on your desk. “The original first-demo. Now.”

You didn’t flinch. “...it’s 11 PM.”

“And?”

“You’ve listened to Seesaw a thousand times. Why now?”

His throat bobbed. “Need to remember why I wrote it.”

You swiveled to the server, pulling up the file. The demo played, raw, unpolished, Yoongi’s voice cracking on “I’m afraid I’ll get used to this pain,” - a line that didn't make it too the final track.

He stood rigid, back to you.

“You wrote it because you were tired of balancing pride and regret,” you said softly. “Because vulnerability felt like failure.”

Yoongi spun, eyes blazing. “You don’t...”

“Know you?” You stood, meeting his glare. “I know the boy who scribbled ‘I need u’ in margins. Who still comes here to argue with his ghost when noone is looking, but I see.”

He stepped closer, heat radiating off him. “And what do you get from this? Playing therapist to fucked-up artists?”

“Maybe I like the company.”

A beat. His gaze dropped to your lips.

The door creaked.

Namjoon poked his head in, blissfully oblivious. “Archivist! Need your take on Nietzsche’s ‘eternal recurrence’ for the speech... Oh. Am I interrupting?”

Yoongi jerked back, cheeks flushed. “No.”

“Yes,” you said.

Namjoon glanced between you, smirk blooming. “I’ll… come back.”

Yoongi left without another word, but not before you spotted the tremor in his hands; the same tremor from the day he’d first held his old notebook.

The Fracture

The air in Studio 4 was always sterile, a vacuum sealed against the outside world. But tonight, it felt like a tomb.

Yoongi had been playing his The Last pt.2 draft on loop for hours, the demo’s jagged bassline gnawing at the soundproof walls. His fingers hovered over the mixing board, tweaking the same three-second clip - “I built my pride from broken glass”, until the words lost meaning.

He didn’t hear the door open. You were one of the few people in the company with keys to almost every room.

“You’re avoiding me.”

Your voice cut through the noise. Yoongi’s shoulders tensed, but he didn’t turn. “Busy.”

“Bullshit.” You stepped inside, the door clicking shut behind you. “You haven’t answered a single text. Skipped the archives all week. What’s wrong?”

What’s wrong. The track pulsed, raw and unpolished. “The Last pt.2” was supposed to be a sequel, closure for the boy who wrote “I want to die” in smudged ink years ago. Instead, it felt like a relapse.

“MIN YOONGI.”

He spun, chair screeching. “Why’re you here? Shouldn’t you be helping Joon craft his precious speech?”

The venom startled you. “He asked me to rehearse. That’s all.”

Yoongi scoffed, jabbing a finger at the screen. “Saw you. Foreheads touching, hands all... whatever. Looked cozy.”

You blinked. “I was stopping him from clicking his pen. He does it when he’s nervous. You know that.”

“Do I?” He stood abruptly, knocking over a half-empty glass of whiskey. The liquid seeped into his notebook, blurring the notes as he shoved past you. “Doesn’t matter. Got a producer meeting.”

“At midnight?”

“Yes.”

You blocked the door. “Talk to me.”

His laugh was brittle. “About what? How you’ve got Joon wrapped around your finger? How he looks at you like you’re his damn muse?”

“You’re being ridiculous.”

“Am I?” He stepped closer, the whiskey on his breath sharp and sour. “You quote his lyrics, fix his speeches, laugh at his jokes... fuck, you even know how he takes his coffee. What’s next? Translating his diary?”

You flinched. “It’s not like that. Also you only drink decaf, iced...”

“Sure.” He yanked the door open. “Have fun crafting legacies.”

Rooftop, 1:14 AM

The wind bit through Yoongi’s sweater as Namjoon found him slumped against the guardrail, whiskey glass dangling from his fingers.

“You look like hell,” Namjoon said, settling beside him.

“Feel like it.”

A beat. The city below hummed, indifferent.

“They quoted The Last in my speech today,” Namjoon said quietly.

Yoongi stiffened.

“Not the lyrics. The… feeling. Said it reminded them that art isn’t about permanence. It’s about…” He paused. “'The courage to shatter what you’ve built.'”

Yoongi’s throat tightened.His line, from the 2016 notebook, unreleased.

Namjoon turned, gaze piercing. “They’ve been stealing your words to fix mine this whole time. Not because they’re mine... because they’re yours.”

The glass trembled in Yoongi’s hand. “Why are you telling me this?”

“Because you’re an idiot.” Namjoon’s voice softened. “They’re not my muse, hyung. They’re yours. Always have been.”

Yoongi stared at the amber liquid, the reflection of his own fractured face staring back.

“You gonna keep hiding in demos?” Namjoon stood, clapping his shoulder. “Or write a new verse?”

Studio 4, 2:03 AM

The door creaked open again.

You froze, breath catching.

Yoongi stood in the threshold, The Last pt.2 still looping. His eyes were red-rimmed, hair a mess, but his voice steadied the storm.

“I’m… shit at this.”

“At what?”

“Talking. Feeling. All of it.” He stepped inside, the door shutting with a soft click. “But I’m worse at pretending I don’t.”

The track swelled - “I built my pride from broken glass” - as he closed the distance.

“Joon’s right,” he muttered, gaze dropping to your lips. “I’m an idiot.”

The space between you crackled.

“Prove it,” you whispered.

He didn't, not yet...

The Harmony

The archives hummed with the static of a thousand dormant stories, the air thick with the scent of ink and longing.

Yoongi stood in the center of the room, his back to you, shoulders tense as he rifled through a box of 2018 demos. The small 7 on his shoulder peeked out beneath his tank top, a silent testament to loyalty, and fear.

“You left this in Studio 4.”

He froze at your voice.

You held up his old notebook, the one with the warped pages and coffee-stained edges. It fell open to “I need u”, the words circled in red, your own scribble bleeding into the margin: “I need you too.”

Yoongi didn’t turn. “Thought you’d be with Joon.”

“Stop.” Your voice cracked. “Stop pretending you don’t see me.”

He spun, eyes dark and stormy. “See what? You quoting my lyrics to fix his speeches? Laughing at his jokes? Holding his damn hand...”

“To stop him from clicking his pen!” You repeated and stepped closer, the notebook trembling in your grip. “You think I care about his speeches? About legacies? I’ve been here every night, waiting for you to look up from your damn demos and see me!”

Yoongi’s breath hitched.

You thrust the notebook at him. “You want to know why I memorized The Last notes? Why I stayed late every time you asked for another mixtape? It wasn’t for the music, you idiot. It was for you.”

The archives fell silent, save for the whir of servers.

Yoongi stared at the notebook, your confession etched beside his oldest wound. When he finally spoke, his voice was raw. “I thought… I was just another track to you. Something to analyze and shelve.”

“You were never just anything.”

He looked up, vulnerability stripping him bare. “I don’t know how to do this.”

“Do what?”

“This.” He gestured between you, the air crackling. “Wanting someone who… who knows all the broken parts.”

You closed the distance, your fingers brushing his. “Then stop hiding in your demos.”

His gaze dropped to your lips. “What if I ruin it?”

“You won’t.”

The kiss was a crescendo; slow at first, tentative, then desperate. Yoongi’s hands cradled your face like you were the last fragile tape in the archives, his lips soft but insistent, tasting of whiskey and unsung verses. The shelves pressed into your back, demos scattering like imperfect notes around your feet. His fingers tangled in your hair, tugging gently as he deepened the kiss, a silent plea for more, more, more...

“Took you long enough,” a voice drawled.

You broke apart, breathless. Namjoon leaned against the doorway, tossing a USB drive at Yoongi. It landed at your table, labeled “Hyung’s Love Song (Finally)” in Sharpie.

Yoongi glared, cheeks flushed. “How long were you...?”

“Long enough to know you owe me 50,000 won.” Namjoon smirked. “Jin-hyung bet on tonight. I said you’d chicken out till dawn.”

Yoongi flipped him off, but his arm stayed wrapped around your waist, anchoring you to his side.

[Bonus] Epilogue: One Month Later

The OT7 group chat exploded at 8 PM.

Jin: [photo of Yoongi feeding you kimchi jjigae in the cafeteria] “Grandpa’s first date since 2014!!! Transfer payments, children.”

Jungkook: “WAIT THEY'RE REAL???”

Hobi: “I TOLD YOU ALL IT WAS THE ARCHIVES. PAY UP!!!”

Taehyung: [Screenshots of Yoongi’s Spotify wrapped] “Since when does hyung listen to Rilke ASMR??”

Yoongi: “Fuck off.”

You: [photo of the USB plugged into Yoongi’s laptop, titled “Love Song (Draft)”] “Track 1: ”Not Yet” 👀”

Namjoon: “Finally.”

END

#magicshopstories#bts fanfic#bts imagines#bangtan fanfic#bangtanimagine#bts fanfction#bangtanfanfiction#bts#bts requests#bts x reader#bts x you#bts x y/n#bts x fem!reader#bts angst#namjoon scenarios#namjoon fanfic#namjoon fluff#suga fanart#suga fic#suga fanfiction#suga fluff#suga angst#yoongi angst#yoongi x reader#yoongi x you#yoongi x y/n#yoongi fanfic#yoongi fluff#yoongi imagine#namgi fic

63 notes

·

View notes

Text

Spinning Plant and Animal Fibers

By Brooklyn Museum - Spindle without Whorl, whole or Spindle with Cotton Yarn, Fragment. Brooklyn Museum. Retrieved on 2019-11-04.Attribution 3.0 Unported (CC BY 3.0) license, CC BY 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=83653957

The beginning of twisting fibers from plants or animal coats is difficult to date because they don't fossilize, so we have to rely on trace evidence, such as imprints in mud that did fossilize. We have these of string-like skirts from the Upper Paleolithic that date to about 20,000 years ago. Recent discoveries, though, show that Neanderthals spun cording as well.

Photo of Neanderthal cord from Abri du Maras. M-H. Moncel

The evidence from the Neanderthals was actual fibers that were preserved in a cave in southern France. The fragment was 6mm long and was three bundles of twisted tree fibers twisted together. The most likely usage of the fiber was to be wrapped around a handle of some type or as part of a net bag. This implies many areas of knowledge held by Neanderthals to make the cording including the growth patterns of the trees the fibers came from, spinning, and spinning the resultant thread into a stronger yarn. 'In order to get this fiber, you have to strop the outer bark off a tree to scrape off the innter bark. This is best done in the spring or early summer,' according to Bruce Hardy, co-author of the study of these fibers and professor of anthropology at Kenyon College in Gambler, Ohio.

This spinning was most likely done against the thigh, twisting the fibers as the hand rolls it down the thigh, pinching them, and then bringing them back to the top of the thigh to be twisted more. The product was likely wound around a stick or stone.

By Rama - Own work, CC BY-SA 2.0 fr, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=49227927

The next step was to spin onto the stick, or spindle, directly, then to create a split or hook in the top of the stick to hold the twisted part on the stick. Exactly when this happened, we don't know, as there are, as yet, no direct remains of this process. What we do have evidence of improved technology is small bone and later metal hooks that replaced the slit or hook cut into wood as well as weights made of stone, wood, metal, clay, or later metal that went on the end of the sticks to keep them spinning longer called spinning whorl. These have been found as early as the Neolithic. The combination of these technological improvements is called the drop spindle and we have artwork depicting spinning from many cultures.

By © Marie-Lan Nguyen / Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=2596494

The other item needed to make spinning easier is an item called a distaff, which would hold a prepared bundle of fibers is loosely wrapped onto, which freed the hand that would have previously held the fiber and allowed a larger quantity of fiber to be held at one time. The distaff could be tucked under the arm or into a loop or holder in a belt. Again, since this didn't fossilize, we don't know when it was developed, though it does appear in Bronze Age artwork.

If you're interested in learning to spin, local independent yarn stores are a good place to start. Other places to look are reenactment guilds, fiber craft guilds, or online for spinning classes. The benefit of guilds is in-person help learning and the benefit of companionship and experience.

58 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello! Trainer from Alola here, big fan of your work. I was wondering; is there any evidence of any legendary pokemon being related to other pokemon? For example, does Rayquaza share any DNA with other dragon pokemon? (I know it would be extremely difficult to get any rayquaza DNA fhshfjd) Or are pokemon like that entirely their own species?

the answer is, as with many things on this blog.. it depends!

"legendary pokemon" aren't really a cohesive category like, say, a type or a taxonomic group. the only common factors are that they tend to be very rare and that they have legends about them. as our examples, let's use two groups of hoenn legendary pokemon: latios and latias, and groudon, kyogre, and rayquaza.

latios and latias (like other pairs such as nidoqueen and nidoking, or volbeat and illumise, latios and latias are sexually dimorphic members of the same species) are indeed related to other pokemon- they're birds! specifically, they're in the auk family, which are a group of generally stout, seafaring birds like guillemots and puffins. this may seem strange- the latis appear to have wings and arms, and no legs, very unlike birds. however, if we take a look at their skeleton, the connection becomes much more obvious:

what we generally interpret as arms are actually the lati's legs, the thighs of which are obscured by flesh and feathers. while they use their wings to steer and for some lift, the latis generally stay aloft with their psychic powers rather than traditional flight, which is why they can hover in place. this has freed up their legs for use in manipulating objects, and they are rarely seen standing on their feet. because they mostly rely on hovering, their legs no longer have the strength to hold their large bodies up for very long.

these pokemon are indeed exceptionally rare, having very low population numbers in only a few regions, and spending most of their time over open ocean. like many pelagic seabirds, they breed on only a few small islands, like alto mare off the johto region and southern island off hoenn's south coast. their populations are on the upswing, though, in large part due to concentrated conservation efforts on those islands. point being, though, they are indeed just animals. rare, powerful animals, but animals nonetheless.

many legendary pokemon fall into this camp. articuno, zapdos, and moltres, lugia and ho-oh, heatran, and various others.

.

conversely, the so-called weather trio of hoenn: groudon, kyogre, and rayquaza. these three are even more rarely seen than the latis, only having been sighted in recent times during their clash in hoenn nearly two decades ago. despite the three's resemblance to other living pokemon, as far as we know they are entirely unrelated to any known animals, or even any other life on earth.

this is known because evidence of these pokemon have been found dating back over 3 billion years ago, that is to say over a billion years before multicellular life even existed. gigantic fragments of footprints attributed to groudon have been sighted alongside some of the earliest fossils we know of of early bacteria. modern physical samples from these pokemon- the extremely few that have ever been recovered- have never resulted in any dna evidence, and appear in structure much more similar to inorganic matter.

as it stands, it appears these pokemon arose some time early (relatively speaking) after the earth formed, being (as opposed to natural living organisms) animate representations of the forces of nature themselves. a similar condition is often assumed for some other grandiose legendary pokemon, such as dialga and palkia, though much less tangible evidence exists for their presence in prehistoric time, so this is mostly an assumption based on their infrequent appearances & legends surrounding their origins.

463 notes

·

View notes

Text

DINOVEMBER 3/13: Sinosaurus triassicus

WE'RE GONNA DO IT FOLKS I'M GONNA DO IT I AM GOING TO COMPLETE THIS CHALLENGE ¡4 DAYS REMAIN! Tbh I've had this drawing sat in my drafts for probably 2 weeks at this point, I've been struggling with no.4 and with the description for this one. She's in colour this time, not because of any premeditated choice but because there wasn't enough contrast between the feathered and nonfeathered parts of the animal.

Anyhoo, Sinosaurus is a theropod from Yunnan province, China that lived roughly 200Ma ago. It's very similar to the North-american Dilophosaurus, being roughly the same size and build, with a pair of head crests that have a distinctive V shape when viewed from the front. Although it's been named since 1940, it was only really properly understood when Specimen KMV8701 was unearthed in the 1980s; this fossil was originally referred to as Dilophosaurus sinensis until it was linked to the jaw fragments of the holotype and reassigned to Sinosaurus.

I'm featuring this animal because another important step has been taken towards understanding it's biology this year: specimen ZLJ0057, another more complete Sinosaurus triassicus found in recent years, has been modelled and analysed in depth by Liang, Falkingham and Xing to help understand it's biomechanics. It was found that Sinosaurus weighed in at almost 850kg, heavier than previously thought, and that it was a strong runner that used both its arms and jaws together to capture prey. These kinds of studies can be a slog to put together, but they form the base on which the rest of palaeontology is built.

#palaeostuff#anthem posts#palaeoart#dinosaurs#dinovember#dinovember 2024#sinosaurus#dilophosaurus#anthems art#palaeoblr#palaeontology#paleoart#n class

70 notes

·

View notes

Text

While some rocks consist of a single mineral, most are combinations of several minerals. Additionally, rocks can include organic materials, such as fossils or plant fragments, further enhancing their diversity and complexity.

#minerals#crystals#gems#rocks#igneous#igneous rocks#sedimentary rock#sedimentary rocks#metamorphic rock#granite#schist

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

Crystal Palace Field Trip Part 2: Walking With Victorian Dinosaurs

[Previously: the Permian and the Triassic]

The next part of the Crystal Palace Dinosaur trail depicts the Jurassic and Cretaceous periods. Most of the featured animals here are actually marine reptiles, but a few dinosaur species do make an appearance towards the end of this section.

Although there are supposed to be three Jurassic ichthyosaur statues here, only the big Temnodontosaurus platyodon could really be seen at the time of my visit. The two smaller Ichthyosaurus communis and Leptonectes tenuirostris were almost entirely hidden by the dense plant growth on the island.

Ichthyosaurs when fully visible vs currently obscured Left side image by Nick Richards (CC BY SA 2.0)

Head, flipper, and tail details of the Temnodontosaurus. A second ichthyosaur is just barely visible in the background.

Ichthyosaurs were already known from some very complete and well-preserved fossils in the 1850s, so a lot of the anatomy here still holds up fairly well even 170 years later. They even have an attempt at a tail fin despite no impressions of such a structure having been discovered yet! Some details are still noticeably wrong compared to modern knowledge, though, such as the unusual amount of shrinkwrapping on the sclerotic rings of the eyes and the bones of the flippers.

———

Arranged around the ichthyosaur, three different Jurassic plesiosaurs are also represented – “Plesiosaurus” macrocephalus with the especially sinuous neck on the left, Plesiosaurus dolichodeirus in the middle, and Thalassiodracon hawkinsi on the right.

They're all depicted here as amphibious and rather seal-like, hauling out onto the shore in the same manner as the ichthyosaurs. While good efforts for the time, we now know these animals were actually fully aquatic, that they had a lot more soft tissue bulking out their bodies, and that their necks were much less flexible.

———

The recently-installed new pivot bridge is also visible here behind some of the marine reptiles.

———

Positioned to the left of the other marine reptiles, this partly-obscured pair of croc-like animals are teleosaurs (Teleosaurus cadomensis), a group of Jurassic semi-aquatic marine crocodylomorphs.

A better view of the two teleosaurs by MrsEllacott (CC BY-SA 4.0)

The Crystal Palace statues have the general proportions right, with long thin gharial-like snouts and fairly small limbs. But some things like the shape of the back of the head and the pattern of armored scutes are wrong, which is odd considering that those details were already well-known in the 1850s.

———

Finally we reach the first actual dinosaur, and one of the most iconic statues in the park: the Jurassic Megalosaurus!

Megalosaurus bucklandi was the very first non-avian dinosaur known to science, discovered in the 1820s almost twenty years before the term "dinosaur" was even coined.

At a time when only fragments of the full skeleton were known, and before any evidence of bipedalism had been found, the Crystal Palace rendition of Megalosaurus is a bulky quadrupedal reptile with a humped back and upright bear-like limbs. It's a surprisingly progressive interpretation for the period, giving the impression of an active mammal-like predator.

This statue suffered extensive damage to its snout in 2020, which was repaired a year later with a fiberglass "prosthesis".

———

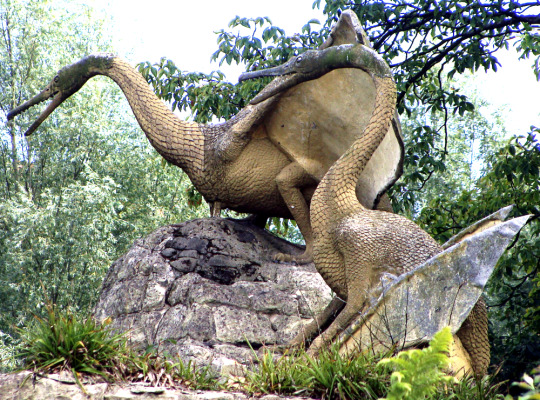

Reaching the Cretaceous period now, we find Hylaeosaurus (and one of the upcoming Iguanodon peeking in from the side).

Hylaeosaurus armatus was the first known ankylosaur, although much like the other dinosaurs here its life appearance was very poorly understood in the early days of paleontology. Considering how weird ankylosaurs would later turn out to be, the Crystal Palace depiction is a pretty good guess, showing a large heavy iguana-like quadruped with hoof-like claws and armored spiky scaly skin.

It's positioned facing away from viewers, so its face isn't very visible – but due to the head needing to be replaced with a fiberglass replica some years ago, the original can now be seen (and touched!) up close near the start of the trail.

———

Two pterosaurs (or "pterodactyles" according to the park signs) were also supposed to be just beyond the Hylaeosaurus, but plant growth had completely blocked any view of them.

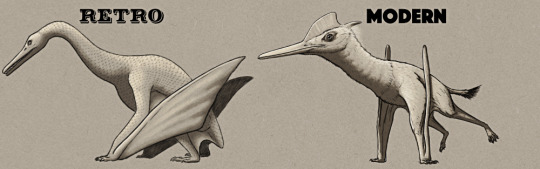

Although these two statues are supposed to represent a Cretaceous species now known as Cimoliopterus cuvieri, they were probably actually modeled based on the much better known Jurassic-aged Pterodactylus antiquus.

A second set of pterosaur sculptures once stood near the teleosaurs, also based on Pterodactylus but supposed to represent a Jurassic species now known as Dolicorhamphus bucklandii. These statues went missing in the 1930s, and were eventually replaced with new fiberglass replicas in the early 2000s… only to be destroyed by vandalism just a few years later.

(The surviving pair near the Hylaeosaurus are apparently in a bit of disrepair these days, too, with the right one currently missing most of its jaws.)

Image by Ben Sutherland (CC BY 2.0)

The Crystal Palace pterosaurs weren't especially accurate even for the time, with heads much too small, swan-like necks, and bird-like wings that don't attach the membranes to the hindlimbs. Hair-like fuzz had been observed in pterosaur fossils in the 1830s, but these depictions are covered in large overlapping diamond-shaped scales due to Richard Owen's opinion that they should be scaly because they were reptiles.

But some details still hold up – the individual with folded wings is in a quadrupedal pose quite similar to modern interpretations, and the bird-like features give an overall impression of something more active and alert than the later barely-able-to-fly sluggish reptilian pterosaur depictions that would become common by the mid-20th century.

(Much like the statues themselves, the "modern" reconstruction above is based on Pterodactylus rather than Cimoliopterus)

———

The last actual dinosaurs on this dinosaur trail are the two Cretaceous Iguanodon sculptures. At the time of my visit they weren't easy to make out behind the overgrown trees, and only the back end of the standing individual was clearly visible.

Named only a year after Megalosaurus, Iguanodon was the second dinosaur ever discovered, and early reconstructions depicted it as a giant iguana-like lizard.

The Crystal Palace statues depict large bulky animals, one in an upright mammal-like stance and another reclining with one hand raised up. (This hand is usually resting on a cycad trunk, but that element appeared to be either missing or fallen over when I was there.)

Famously a New Year's dinner party was held in the body of the standing Iguanodon during its construction, although the accounts of how many people could actually fit inside it at once are probably slightly exaggerated.

A clearer view by Jim Linwood (CC BY 2.0)

Considering that the skull of Iguanodon wasn't actually known at the time of these sculpture's creation, the head shape with a beak at the front of the jaws is actually an excellent guess. The only major issue was the nose horn, which was an understandable mistake when something as strange as a giant thumb spike had never been seen in any known animal before.

(The fossils the Crystal Palace statues are based on are actually now classified as Mantellisaurus atherfieldensis, but the "modern" reconstruction above depicts the chunkier Iguanodon bernissartensis.)

———

Image by Doyle of London (CC BY-SA 4.0)

I also wasn't able to spot the Cretaceous mosasaur on the other side of the island due to heavy foliage obscuring the view.

Depicting Mosasaurus hoffmannii, this model consists of only the front half of the animal lurking at the water's edge. It's unclear whether this partial reconstruction is due to uncertainty about the full appearance, or just a result of money and time running out during its creation.

The head is boxier than modern depictions, and the scales are too large, but the monitor-lizard like features and paddle-shaped flippers are still pretty close to our current understanding of these marine reptiles. It even apparently has the correct palatal teeth!

Next time: the final Cenozoic section!

#field trip!#crystal palace dinosaurs#retrosaurs#i love them your honor#crystal palace park#crystal palace#ichthyosaur#plesiosaur#teleosaurus#crocodylomorpha#marine reptile#megalosaurus#theropod#hylaeosaurus#ankylosaur#iguanodon#ornithopoda#ornithischia#dinosaur#pterodactyle#pterodactylus#pterosaur#mosasaurus#mosasaur#paleontology#vintage paleoart#art

478 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Homo Habilis

Homo habilis ("handy man") is an extinct species of human that lived in East and South Africa between 2.3 and 1.5 million years ago and plays an interesting role in the discussion surrounding the dawn of our genus of Homo, which is thought to have first appeared around 2.5 million years ago.

Homo habilis was often seen as one of the earliest members of our genus and, for a long time, was commonly depicted as the ancestor of Homo erectus (thus, being a direct ancestor of our own species, too). Nowadays, this is debated, and a much more complex picture of the early days of Homo has emerged. Much discussion remains about the place of Homo habilis within this picture.

The fragmentary fossil record when it comes to Homo habilis (and many other species around at this early time) does not help; though we have a collection of skulls and skull fragments, only three so-called postcranial (below the skull) skeletons have been unearthed, and they are incomplete. The remains showcase a mishmash of features that in some parts resemble Homo, and in others resemble those found in Australopithecus.

What we do know is that Homo habilis was both fully bipedal, as well as a good and probably frequent climber, with strong hands that fashioned stone tools belonging to the Oldowan industry.

Discovery

Homo habilis was first described in 1964 by the British-Kenyan palaeoanthropologist Louis Leakey and his colleagues in a paper that rocked the scientific community. Along with his wife, Mary, Leakey had been combing Olduvai Gorge in Tanzania since the early 1950s in search of traces of Homo's first steps and had already discovered early stone tools belonging to what he termed the Oldowan industry. In the early 1960s, their son Jonathan found several skull and lower jaw fragments, along with some hand bones, in the same fossil bed that had yielded the tools. Soon, more remains were uncovered, including an adult foot, a skull with both upper and lower jaw, and a very fragmented skull with teeth.

Their verdict was that the new remains were quite 'modern' in appearance: they appeared closer to the genus Homo than to that of other early hominins like the Australopithecines. Clearly, this was a good fit for their toolmaker, they argued. Following the definition of Homo that was generally accepted at that time, the team felt the new fossils successfully met three of the key criteria: this species had an upright posture, could walk in a bipedal manner, and had the necessary dexterity to create stone tools. However, the fact that its brain volume was smaller than that of established members of Homo at the time required some fidgeting: the team thus proposed relaxing this criterion a bit.

Leakey's 1964 paper argued for the new species to be added to the genus Homo in the shape of Homo habilis – from the Latin for "handy, skilful, able". The announcement marked a turning point in palaeoanthropology, as Bernard Wood describes: "It shifted the search for the first humans from Asia to Africa and began a controversy that endures to this day." (2014).

Although the Homo habilis taxon was officially validated by the scientific community, it has frequently been challenged and criticised – a battle that is ongoing.

Continue reading...

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

i finally did a design of twisted shelly that i like yippee! also heads up bones, body horror, blood, and rot not drawn the best but it's implied below the readmore

so, i spinned a wheel to see who to work on next and shelly got picked. the dealo of endless is that gardenview got distorted and corrupted by an ichor creature the only one who didnt get twisted is dandy and shrimpo. the corruption made gardenview center into a whole world with fragments of garden view mixed with like minecarft inspired biomes. there's dungens for all the twisted toon and the mains twisted are not the only one with more fucked up form, and they each have their own fighting mechanism. shelly's dungen location is in a badlands, the enemeies are based on fossils, bones and dinosaurs. shrimpo must defat her and take her to dandy so he can use ichor to mend her wounds and go back to her og form. i'll design her after everything later.

#yolk art#yolk the joke#myart#art#digital art#fanart#dw au#au#artists on tumblr#my art#artwork#illustration#dandys world roblox#dandysworld#roblox dandys world#dandys world#dandy's world fanart#endless dandy's world au#dandy's world au#dw shelly#dandys world shelly#dandy's world shelly#body horror tw#tw blood#cw: bones#clip studio paint#clip studio art#dandys world au#endless

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

𐌂𐌀ɽ𐌀'𐌔 Ꮤ𐌄𐌀𐌐ꝋ𐌍𐌔

Thrym’s Lower Jawbone and Teeth

Teeth: Both halves of Thrym’s lower jawbone remain intact, their teeth gleaming with an unnatural sharpness. Despite the age of the fossilized jawbone, these fangs are pristine, as if time and decay have no claim on them. They’re still capable of tearing through flesh and bone with ease.

Significance: These aren’t just trophies; they embody Thrym’s enduring strength and Cara’s deep connection to him. They are a primal reminder of the bear who once stood by her side, their readiness for battle a silent promise of his lingering presence.

The Jawbone Halves: A jagged monument to loss and divinity, the Jawbone Halves are more than mere bone—they are a covenant carved in ice, a fractured hymn to a god’s suffering. Each half of Thrym’s lower jaw, sundered cleanly by forces unknown, resembles a glacial shard torn from the heart of a dying star. Timeworn and gnarled by eons, the fossilized bone gleams like polished ivory veined with cobalt, its surface etched with spiraling runes that pulse faintly, as though breathing with the rhythm of Thrym’s spectral soul.

Physicality & History: The left half bears the scars of Thrym’s mortal torment: deep gouges from chains, hairline fractures from the chieftain’s cudgel, and a permanent stain of rust-brown where his lifeblood seeped into the bone. The right half, smoother but no less ancient, glimmers with an ethereal frost, its edges lined with tiny, crystalline teeth that shimmer like trapped starlight—a haunting reminder of the cub who once nibbled his mother’s nose beneath the auroras. When joined, the halves lock seamlessly, revealing the full arc of Thrym’s primal roar frozen in time, a silent scream that still chills the air around it.

Magical Essence: To touch the Jawbone is to feel the weight of a glacier and the whisper of a ghost. It thrums with a low, resonant hum, a dirge that vibrates through the marrow—a soundless lament for Thrym’s stolen innocence. When Cara clasps her half, it warms gently, as if cupping a handful of freshly fallen snow kissed by sunlight. Yet its chill never fades; frost feathers across surfaces beneath it, and in moments of sorrow or rage, its glow intensifies, casting shadows that twist into spectral visions of ice-bound forests and a caged bear’s despair.

Symbolism & Power: This is no passive relic. The Jawbone is Thrym’s tether to the mortal realm—and Cara’s lifeline to the divine. Its fractures mirror the cracks in his spirit, yet its unyielding structure embodies his unbroken will. Those who dare wield it without reverence find their hands numbed to the bone, their breath crystallizing in their lungs. For Cara, it is both compass and confessional: when pressed to her brow, it floods her mind with fragments of Thrym’s memories—the coppery tang of his mother’s blood, the suffocating stench of the arena, the honey-sweet oblivion of his first taste of freedom.

A Divine Paradox: Here lies the contradiction: a relic of death that brims with stubborn, seething life. The Jawbone’s magic is primal, raw, and unrefined—a storm contained. It rejects decay, its edges sharpening in winter’s heart and softening under summer’s gaze, as though Thrym himself still seasons the world through it. To hold both halves is to stand at the threshold of godhood, to feel the raw scrape of a glacier’s march and the fragile warmth of a spirit refusing to be forgotten. In the end, the Jawbone Halves are not just bone. They are a requiem. A promise. And, perhaps, a thaw waiting to begin.

Kira’s Dagger

Blade: Forged from Starfall Iron—a rare fusion of meteorite and iron ore—this blade is a deep, inky black. When caught in the right light, it sparkles like a star-strewn night sky, a hauntingly beautiful effect that mirrors the cosmos.

Hilt: Carved from the bone of a Sawtail—a creature renowned for its toughness—the hilt bears intricate carvings of Frostbloom Flowers. These delicate etchings were done by Cara herself, each petal and stem a labor of love in memory of her sister, Kira.

Emotional Weight: More than a weapon, this dagger is a piece of Kira’s essence, a keepsake that blends sorrow and strength. It cuts with both steel and sentiment, a constant companion that keeps Kira’s warmth alive.

This is more of a trinket than a weapon to Cara as she never uses this blade until she is taken to the Howa'ahian Palace.

Hidden Retractable Blade

Material: Crafted from the femur bone of a Wolf Drake—a cunning and ferocious predator—this blade is lightweight yet devastatingly sharp.

Design: Tucked within Cara’s hide gauntlets, it deploys with a flick of her wrist, its razor edge perfect for slashing or stabbing in an instant. It’s a silent killer, designed for speed and surprise.

Purpose: This is Cara’s last resort, a hidden trump card that ensures she’s never truly defenseless. It’s a symbol of her refusal to be caught off guard again.

Frost and Lightning Rune-Enchanted Necklace

Pendant: Shaped from Thrym’s shed ice, this crude pendant was carved by Cara into an awkward hammer-like form. It’s blunt on one end for crushing and pointed on the other for piercing or stabbing.

Enchantments: Embedded with frost and lightning runes, it pulses with energy—capable of unleashing freezing cold or electric shocks with a touch.

Strap: Made from the scarred hide of a BloodFang Wyvern, the leather is as tough and battle-worn as Cara herself, a trophy from a near-fatal encounter.

Significance: This necklace doubles as a weapon and a protective charm, channeling Thrym’s spirit to guard her as fiercely as he once did in life.

Small Claw Pocket Knife

Blade: Carved from one of Thrym’s shed claws, this narrow, slightly curved knife has a rough, hand-forged edge that reflects its origins in the wilds.

Handle: An extension of the blade itself, it features a decorative spiral loop at the top—ideal for hanging or quick access.

Utility: Small but versatile, it’s perfect for carving, skinning, or delivering a swift, lethal strike. It’s a constant reminder of Thrym, always within reach like a trusted friend.

Viper Cat Bone Shiv

Origin: This jagged, blood-stained shiv was Cara’s first weapon, carved from the bone of a Viper Cat in the slavers’ pits. It’s crude and brutal, a product of desperation that fueled her escape to the wilds of Howa’ah.

Sentiment: It’s a raw symbol of the terrified girl she once was—and the unbreakable will that carried her through. She keeps it as a memento of her survival, a testament to her refusal to surrender.

Thin Spears of Ice

Magic: Formed from Cara’s frost magic, these spears are translucent and razor-sharp, their icy chill capable of impaling on impact.

Tactics: She summons them in an instant, hurling them with pinpoint accuracy or using them to impale foes. They’re as fragile as they are deadly, a frozen extension of her rage and precision.

Bow with Blunt Forced End and Enchanted Arrows

Bow: Made from sturdy wood with metal-capped ends, this bow is built for versatility. The blunt tips double as clubs when arrows run out or enemies close in.

Arrows: Each arrow is tipped with enchanted runes—some crackle with lightning, others glow with frost, and a few carry a mysterious, darker magic.

Versatility: This weapon is both a hunter’s tool and a warrior’s lifeline, excelling at range and holding its own up close. It reflects Cara’s adaptability, her ability to fight on any terms.

Razor-Like Shards in Cara’s Hair

Description: These are razor-sharp shards made from either Thrym’s enchanted ice or the polished bones of beasts Cara has hunted. They are small, lethal, and seamlessly woven into her blonde hair.

Purpose: Designed to prevent enemies from grabbing her hair during combat, the shards act as a hidden trap. When an opponent makes contact, the jagged edges slice into their flesh, drawing blood and forcing them to let go. The ice shards, infused with frost magic, also chill the attacker’s skin, adding an extra layer of deterrence.

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Round 2.5 - Cnidaria - Hexacorallia

(Sources - 1, 2, 3, 4)

The anthozoan class Hexacorallia contains five extant (living) orders: Actiniaria (“sea anemones”), Antipatharia (“black corals” or “thorn corals”), Corallimorpharia (“false corals”), Scleractinia (“stony corals” or “hard corals”), and Zoantharia (“zoanthids”). This class contains many of the most important reef builders: the stony corals, sea anemones, and zoanthids.

Like all anthozoans, these organisms are formed of individual soft polyps which in some species live in colonies and can secrete a calcite skeleton. Some species live as solitary polyps. Hexacorals are distinguished from Octocorals by having six or fewer axes of symmetry in their body structure, and tentacles which are simple and unbranched and normally number more than eight. Reef-building or hermatypic corals are mostly colonial, building a communal skeleton around their colony. Corallimorphs are similar to the stony corals, except for the stony skeleton, and have a tendency to overgrow reefs in a carpet formation. Most sea anemones are solitary, single polyps attached to a hard surface by their base but some species float near the surface, or can deatach to escape predators.

Hexacorals are filter-feeding carnivores, using their tentacles armed with stinging cells, called cnidocytes, to catch and neutralize plankton and draw it into their mouth. Larger polyps are able to take correspondingly larger prey, including various invertebrates and even fish. Many species have separate sexes, the whole colony being either male or female, but others are hermaphroditic, with individual polyps having both male and female gonads. Most species release gametes into the sea where fertilisation takes place, and the planula larvae drift as plankton, but a few species brood their eggs. Once the larvae settle in an area, they will metamorphize into a polyp. In colonial species, this initial polyp will repeatedly divide to give rise to an entire colony. Hexacorals can also reproduce by fragmentation, where part of a colony becomes detached and reattaches elsewhere, cloning polyps to grow the colony in the new area.

Hexacorals have existed since the Fortunian. Mackenzia, from the Middle Cambrian Burgess Shale of Canada, is the oldest fossil identified as a sea anemone. Nonetheless, many hexacorals have been declining in numbers and are expected to continue declining due to poaching, ocean acidification and climate change.

Propaganda under the cut:

Hexacorals provide housing, shelter, food, and protection for so many other animals. They are The Givers of the Animal Kingdom.

The largest coral ever recorded, a Pavona clavus colony dubbed the “mega coral” lives off the Solomon Islands. It is 34m (112 ft )wide, 32m (105 ft) long and 4.9m (16 ft) high, larger than a Blue Whale, composed of nearly one billion polyps, and more than 300 years old!

Coral is loud. It can hear and it communicates with each other via sound. We’re only beginning to discover this information and understand the implications of it, and more research needs to be done, but the amount of noise-making humans do in the ocean tends to disrupt the communication corals have with each other and other reef life.

Black Corals have historically been used by Pacific Islanders for medical treatment and in rituals, and are used in modern day for making jewelry.

Sea anemones and zoanthids are popular in the aquarium trade, however, their popularity threatens some populations as the trade depends on collection from the wild.

In southwestern Spain and Sardinia, the Snakelocks Anemone (Anemonia viridis) is consumed as a delicacy. The whole animal is marinated in vinegar, then coated in a batter similar to that used to make calamari, and deep-fried in olive oil.

Most sea anemones are harmless to humans, but a few highly toxic species (notably Actinodendron arboreum, Phyllodiscus semoni and Stichodactyla spp.) have caused severe injuries and are potentially lethal.

Clownfish and Anemonefish (Subfamily Amphiprioninae) are most famous for having a mutualistic relationship with sea anemones, receiving protection from predators by hiding in the anemone's stinging tentacles, and providing the anemone nutrients in the form of faeces. Some other animals have been recorded utilizing sea anemones in a similar way, including cardinalfish, juvenile threespot dascyllus, incognito (or anemone) gobies, juvenile painted greenlings, various crabs (such as Inachus phalangium, Mithraculus cinctimanus and Neopetrolisthes), shrimp (such as certain Alpheus, Lebbeus, Periclimenes and Thor), opossum shrimp (such as Heteromysis and Leptomysis), and various marine snails. One of the more unusual relationships are those between certain anemones (such as Adamsia, Calliactis and Neoaiptasia) and hermit crabs or snails, where the anemones live on the shell of the hermit crab or snail, providing protection from predators while being provided with transportation. Another unusual relationship is between Bundeopsis or Triactis anemones and Lybia boxing crabs, where the small anemones are actually carried around in the claws of the boxing crab as little weapons.

Look at this anemone eating an entire Mola:

(source)

75 notes

·

View notes

Text

A size comparisson of the infamous Quinkana fortirostrum, the terrestrial mekosuchine of Pleistocene Australia.

Quinkana is an....interesting animal. A lot remains unknown about it due to the fact that we only have skull material that is properly assigned to the genus, but some hip bones from the Oligocene Riversleigh indicate that at least one mekosuchine had erect-limbs, something that best fits Quinkana.

The size is also something that is fraught with missconceptions. Sometimes people will cite lengths of 6 to 7 meters, but those are not well supported. True enough, a jaw fragment of a croc that size has been assigned to Quinkana in the 90s, but it was never described beyond a conference abstract and a brief mention in Molnar's "Dragon's in the Dust". Given the mess Mekosuchinae was at the time and how much we learned since, I doubt the assignment and by extension "mega Quinkana" (personally I would not be surprised if said fossil turned out to be Paludirex) and went with the much more concrete estimates centered around the holotype skull, which indicates an animal no more than three meters long.

Finally, with the silhouette I mostly tried to accomodate the published estimates with the actual skull size, while going with limbs that are adapted better to moving on land without being too overly lanky (after all it is still a crocodilian). I ended up pulling a lot from Cuban Crocodiles, but as I mentioned the lack of proper fossils means that this is ultimately just one possible interpretation.

I've recently written a major expansion of Quinkana's wikipedia page, which should reflect our current state of knowledge on this fascinating crocodile.

#mekosuchinae#quinkana#quinkana fortirostrum#croc#crocodile#crocodilia#australia#pleistocene#palaeoblr#prehistory#size chart

60 notes

·

View notes

Text

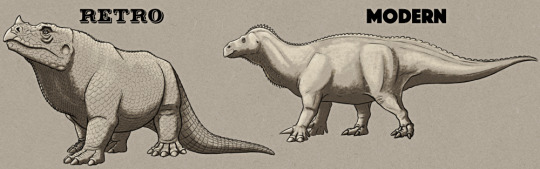

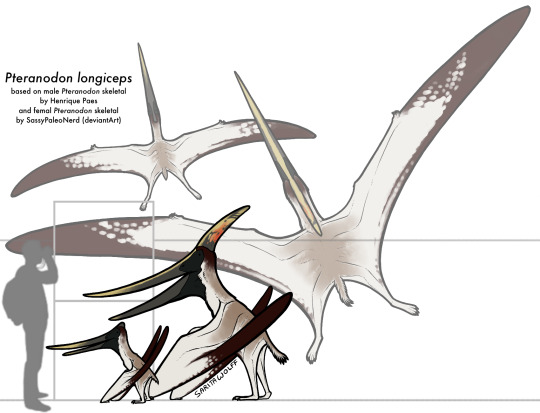

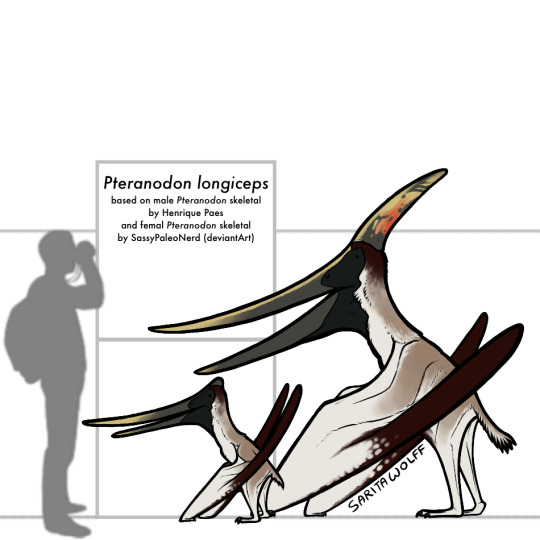

Archovember 2024 Day 25 - Pteranodon longiceps

As one of the main species to make up the mythical “Pterodactyl” conglomerate, Pteranodon longiceps is possibly the most familiar pterosaur to the public. However, most people don’t know much about the real animal behind the pop culture monster. Living in the Late Cretaceous USA, Pteranodon is also the most well-known pterosaur to science, as over 1,200 specimens have been found! It was the first pterosaur found outside of Europe, the first toothless pterosaur found, and, before the discovery of the giant azhdarchids, was also the largest pterosaur known. Pteranodon is also one of the few prehistoric animals with confirmed sexual dimorphism, and it’s a bit extreme to boot! The larger male Pteranodons had huge pointed crests and an average wingspan of 5.6 m (18 ft), while the smaller female Pteranodons had small, rounded crests, wider pelvic canals, and an average wingspan of 3.8 m (12 ft).

Pteranodon lived around the Western Interior Seaway, a massive sea that split North America in two during the Late Cretaceous into the Early Paleocene. With wings shaped like modern day albatrosses, Pteranodons were likely gliders who relied on thermals, but did seem to be more capable of sustained flapping. As one would expect, their diet was made up mostly of fish, though they may have eaten invertebrates as well. With their more heavy build, they could probably dive into the water like modern day gannets, folding up their wings and plunging beneath the waves, snatching up fish with their pointed, birdlike beaks. Pteranodon crests were most likely for display, as there was variation between not only males and females, but also individual males. As females were twice as common as males, they were probably polygynous, with males competing for the mating rights in rookeries of females. Competition was likely not physical, and instead would depend on females determining the age and fitness of males based on the size of their crest.