#Maws and Judaism

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Trying to find something to do when I finally start keeping Shabbos is a fun challenge because it's like

Knowledge: you should rest and not work

Me: great I'm unemployed and spend my days on the couch I'll just boot up my computer and-

Knowledge: the use of electronics counts as work

Me: ok fine so a day without screens that's fine I have meatspace hobbies like I draw and crochet and-

Knowledge: creating counts as work

Me: right. um. well I can listen to- no music requires electronics. but at least I can write- no that's creating. at least I can?? go for a walk??

Knowledge: yes

Me: yay

Knowledge: but you may not bring any items you are not wearing in public

Me: uh-yay... I'm out of ideas ._.

Mom: hey can you help me untangle all these yarns? there's probably enough here to keep you busy for weeks but you can just do one bit at a time no rush

Me: !!! That's something I can do! That's not electronic or creative!!

Knowledge: buddy I have bad news about untying and separating threads

#before anyone tells me to read: dyslexia and ADHD make that very difficult to do for extended periods of time#additionally I live alone and don't know how to socialize with humans irl so hanging out with someone is in limited supply#can't take care of a pet. like really there ain't much I can do#sfw#personal#ok to reblog#Maws and Judaism#whenever I find an interest not involving electronics I get excited and then I inevitably realize that it still counts in some way#endless back and forth of “oh but maybe” “no”

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

truly no is doing the jewish superman subtext like the My Adventures With Superman writers. Despite being raised on Earth, by human parents, he feels like he doesn't belong as Clark, and when he's Superman he feels okay for a while, but then is ostracized and realizes he doesn't really belong as either Clark the Human or Superman the Alien.

77 notes

·

View notes

Text

just here piejesuposting through the horrors

#god busting through the walls of my hardened heart like the kool aid man OH YEAHHH#i think ill use this as an intro post perhaps#welcome#i was raised nondenominational though have been surrounded by southern baptists#ive been wrestling w/ & deconstructing my faith for quite some time & actually even began the conversion process to judaism last year#it was enough to fill the god-shaped yawning maw of a wound in my soul but then it wasn't#jesus tapped me on the shoulder and now im home again#not a clue how to tag this uhh#personal#christianity#lgbt christian#progressive christian#queer christian#jesus christ#friend of mine

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

If me hearing about how much Jewish people argue was part of what led me to my decision to convert does that count as reproduction?

where’s that meme about not arguing with jews because they get sexual pleasure from it when you need it

#obviously I'm not converting because 'wow cool arguing religion' asdfgjklahfk#it's much deeper than that but the more 'shallow' things are what drew me in close enough to appreciate the depth and recognize it#as home#Maws & Judaism#tw religion mention#NSFW-sex mention

440 notes

·

View notes

Note

I'm thinking of Mad being like opposite of Max in some ways. Like, she was the only child. Was unplanned and unloved.

Max was taught his culture by his parents, Mad studied it herself from books in secret.

Her family was slaughtered in front of her eyes too, but they were abusive and neglectful. And when Lycans attacked Mad locked the door, so her family couldn't escape and watched them die.

I like thinking of Mads' family as more neglectful than anything, maybe a little mentally abusive but not like... physically abusive. Like they weren't like Melony's mother, hyper religious and locking her in closets and all that. They just... didn't want her, so they ignored her.

Well, I say "they", Mads only grew up with her dad. He didn't care for religion, he only had books on Judaism because they were in a pile of her mother's things he hadn't thrown away. Incidentally, he never really cared for Madison either. He constantly forgot about her, and she can only recall a handful of actual conversation she had with him. A lot of which consisted of some thinly veiled insults from both sides. Maybe some yelling matches.

He always treated her more like a pest he had to feed on occasion, he never engaged with her, she isn't even entirely sure he knew what her name was. If she brought up the Judaism stuff he would just brush it off. (To be fair she's pretty sure he didn't know shit about it anyway)

Oh, she still witnessed him be ripped apart by Lycans. Dragged out of his bed in their maws and torn to pieces. She has a lot of complicated feelings about it. It didn't necessarily feel good to witness, but she didn't try to help him, either. She can't say she's glad he's dead, like Melony with her mother, but she doesn't really miss him, like Max with his family. It just kind of... is a thing that happened.

Familial relationship aside, Mads just hate that she saw a person die like that (several, actually, if we consider the fact she had to run). She's pretty sure that fucked with her more than the fact she lost her only family.

#like i don't think she watched by choice#she just heard them break in and when she got there he was already being eaten and had a moment of shock#then she just ran for it#asks#anons#oc madison

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

"The Impedance." From the Gospel of Saint John, 3: 16-21.

As we learned within the Angelic Code, all beliefs in Judaism require a witness just like quantum mechanics, medicine, the engineering and all artistic disciplines. Just like sex is no good if it's only talk, the religion requires a second, far more important demonstration of its sentiments.

One cannot say one is going interlinear and is going to meet Ha Shem some Shabbat Afternoon, one must gun for it. We have already discussed this can only happen if we publish the Torah and manifest the Self on the Other Side.

As we learned in the prior frame about John 3:16, however, what one finds in search of the Self cannot be defined up front:

"It may come as a shock to you but the Bible is not about religion. Never been. Lots of people have turned the Bible into a religion but then, lots of people have turned their TV sets into aquariums. Aquariums and religions certainly have a purpose, but the Bible has always been about science, or what later became known as science.

And science, we must quickly add, is not a dogma but a method that allows broad populations of otherwise unrelated people to form a single mind in understanding creation (Acts 2:46, Ephesians 4:3-6, 2 Corinthians 13:11). This method is not infallible, but it's the best one we got. And despite its many faults, science has cured more blindness, lameness and leprosy, alleviated more poverty and snatched more people out from the maw of death than any other method out there (Luke 7:22).

Regardless of the enthusiasm of certain advocates, science does not tell you what to believe. Instead, science offers a way to organize your thoughts. And this not in order to find some elusive "Truth" but rather in order to be able to confer with others — not others who think the same thoughts, but rather others who think the same way.

Science is an operating system, a method of thought, whose purpose it is to let people exchange their considerations. Science, therefore, is much rather a language than anything else; its standards and procedures are in fact very much like those of any language. Without them, we produce mere growls, howls and whistles but with them we can declare what's going on in intimate detail.

Science lets you say whatever you want about anything at all, in such a way that anybody anywhere in the world is able to understand what you're on about. Science is a language. It facilitates a trade network of thought. Its currency is information but its value is confirmation. And the growing body of confirmation is certainly not a government-issued fiat or dogma, but "a thing agreed on"; not an eternally static graven image, but a living observation that's always subject to continued review, and thus always grows into unimaginable splendor (Isaiah 7:14-16, Luke 2:40, 1:52).

It's for these reasons that science is not limited to any particular topic or restricted to any particular data set but can be used to review anything at all on the proviso that anything that is asserted is falsifiable (able to be proven wrong when wrong). This in turn means that, contrary to popular belief, science is a method that always proves wrong and never right, and thus separates the world of thought into (a) thoughts that are definitely wholly false, and (b) thoughts that possibly contain truth to some greater or lesser degree.

Science is like panning for gold, and with every swirl the panner separates certified dirt from the mix of dirt-and-gold remaining in the pan. Long before politicians invented fool's gold and duped the gullible, the Bible contemplated the real stuff, how to get it and what to do with when you did (Genesis 13:2, 1 Kings 6:20-22, Isaiah 48:10, Zechariah 13:9, Malachi 3:3, Revelation 3:18). Not any modern religion but modern science is the rightful heir of the genius of the Bible (Luke 14:24).

With the principles of science, people are able to govern their thinking and purify their observations from bias, folly and preconception (Romans 12:2). To achieve this, these people need first to develop standards of communication — from onomatopoeia to speech, then writing, then a postal service, then book printing, then telephonics, then the Internet, then cryptocurrency and Artificial Intelligence; all hitching a ride on the back of international trade, of which Abraham is the celebrated patriarch — and that is why the Bible is not about religion but about information technology."

The Zohar calls this "when Aenon is near Salim," "when the eye is near completeness and wholeness." = a certain Jew. This brings us back to the beginning of the Gospel and Baptism in the Holy Spirit, AKA cermonial washing. Ceremonial washing which adheres to the Kashrut, the laws of Kosher are a call to action to keep the self positively absolutely away from drama. Do not gossip, sleep around, do not speak your mind, do not give advice, do not even think about these things.

But can I have gay bondage sex in public with the Salim? The Value in Gematria is 2785, בזןה , "a falcon is scorned in the variety."

So one should not stir up drama by showing off the Salim in a public sexual situation.

SO, John Testifies Again About Jesus

22 After this, Jesus and his disciples went out into the Judean countryside, where he spent some time with them, and baptized.

23 Now John also was baptizing at Aenon near Salim, because there was plenty of water, and people were coming and being baptized. 24 (This was before John was put in prison.)

25 An argument developed between some of John’s disciples and a certain Jew over the matter of ceremonial washing.

26 They came to John and said to him, “Rabbi, that man who was with you on the other side of the Jordan—the one you testified about—look, he is baptizing, and everyone is going to him.”

Baptism in the Holy Ghost/Ceremonial Washing therefore is complete purity, the fulfillment of the Lord's Prayer, and all of the Hillels, no sweat.

The Values in Gematria are:

v. 22: They went to the Judean countryside. People in the countryside are much more likely to be orthodox also more likely to welcome advancement change. Jesus went there because this is where all the landowners and taxpayers lived and told them not to give their sons to Rome.

The Number is 8875, חחזה, chaza, "live like this."

=

Do not let the government come and take your family or your happiness away. We must raise an army and kill the Republicans if they start uprooting those immigrants. We have been remisss by allowing any of them to live.

v. 23-24: Now John was baptizing. He was encouraging people to Cross the Jordan. The Number is 13729, יגזבט, exbat, "the impedance."

Impedance, represented by the symbol Z, is a measure of the opposition to electrical flow. It is measured in ohms. For DC systems, impedance and resistance are the same, defined as the voltage across an element divided by the current (R = V/I).

=

Mitigate one's resistance to temptation.

v. 25-26: Everyone is going to him. The Number is 14232, ידבגב, kitabegbe, "read the writing to learn about agape."

=

"The love between a nucleus and other particles."

=

"The knowledge of excitement."

"In the material universe there are four natural forces. Two of these are small scale and operate only within the atomic nucleus, but the other two are large scale and those are the two forces from which all goings on in the universe derive. These two large scale forces are electromagnetism and gravity.

Electromagnetism is carried by photons and when photons are absorbed by a material particle, this particle obtains private motion, or motion relative to (usually away from) neighboring particles. This is where heat comes from. Heat is the same thing as particles going their own way, and the more energy particles privately absorb, the harder they bounce against their neighboring particles. Heating up a liquid like water causes individual water molecules to go wild, until they eventually get so excited that they jump out of the pool and become steam.

Since the universe is a giant fractal and everything complicated derives from something less complicated which is still essentially the same (this is called self-similarity), the mental equivalent of photonic absorption is getting mentally excited. The mind is constituted by what it knows, which in turn determines what it observes, which in turn determines its level of excitement. Excitement doesn't lead to more knowledge, but knowledge leads to observation, which in turn leads to the excitement of what one already knows. Excitement of what one knows sets one on a path that differs from someone who has not the identical knowledge plus excitement."

The knocking twice aspect of Judaism, which is inalienable from it explains why Christianity and its explanations of the mysteries of the Christ are invalid. One cannot just say the words and go unto to Jesus. That is a stupid person's absurdity.

The Gospel of John Torah shall continue.

0 notes

Text

None of you appreciate my art know Hebrew

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

doing my foundations of judaism course study and i love hashem just saying the levites get the foreleg, jaw and maw of any butchered animal AND the first of the tithings like gee levites why does hashem let you have ALLL that

0 notes

Text

QUESTIONS & ANSWERS: How Many Prophets Were There? Were They All From Arabia?

Prophets were raised and sent to their people in different lands and at different times. One hadith puts the number of Prophets at 124,000; another mentions 224,000. Both versions, however, should be evaluated critically according to the science of hadith. The exact number is not important; rather, we should realize that no people has ever been deprived of its own Prophet: There never was a people without a Warner having lived among them (35:24) and: We never punish until We have sent a Messenger (17:15).

To punish a people before warning them that what they are doing is wrong is contrary to His Glory and Grace. The warning precedes responsibility, which may be followed by reward or punishment: Anyone who has done an atom's weight of good shall see it. And anyone who has done an atom's weight of evil shall see it (99:7–8). If a Prophet has not been sent, people cannot know what is right and wrong and so cannot be punished. However, since every individual will be called to account for his or her good and evil deeds, we may infer that a Prophet has been sent to every people: We sent among every people a messenger with (the command): "Serve God and avoid evil" (16:36).

The Prophets were not raised only in Arabia. In fact, we do not even know all of the Prophets who were raised there, let alone elsewhere. We know only 28 of them by name (from Adam to Muhammad), and the Prophethood of three of them is uncertain. We do not know exactly from where they emerged. Supposedly, Adam's tomb and the place of his reunion with Eve is Jidda, but this information is uncertain. We know that Abraham spent some time in Anatolia, Syria, and Babylon. Lot was associated with Sodom and Gomorrah, around the Dead Sea; Shu'ayb with Madyan; Moses with Egypt; and Yahya and Zakariyya with the Mediterranean countries—they may have crossed to Anatolia, since Christians link Mary (Mayam ibn 'Isa) and Jesus with Ephesus. But these associations remain suppositions at best.

We know the names of some Prophets sent to the Israelites, but not the names of any others or where they appeared. Moreover, because their teachings have been distorted and lost over time, we cannot say anything about who they were and where they were sent.

Take the case of Christianity. Following the Council of Nicea (325 CE), the original doctrine of God's Oneness was dropped in favor of the human-made doctrine of the Trinity. For the Catholic Church, Jesus became the "son" of God, while his mother Mary became the "mother" of God. Some believed, rather vaguely, that God was immanent or present in things. Thus, Christianity came to resemble the idolatrous beliefs and practices of ancient Greece, and its followers began to associate other things and people with God, a major sin in Islam.

Throughout history, deviations and corruption of the Truth started and increased in this way. If the Qur'an had not informed us of the Prophethood of Jesus and of the purity and greatness of Mary, we would have difficulty in distinguishing the cults of and rites of Jupiter (Zeus) and Jesus, Venus (Aphrodite) and Mary.

This same process may have happened to other religions. As such, we cannot say definitely that their founders or teachers were Prophets or that they taught in a specific location. We only can speculate that Confucius, Buddha, or even Socrates were Prophets. We cannot give a definite answer because we do not have enough information about them and their original teachings. However, we know that the teachings of Confucius and Buddha influenced great numbers of their contemporaries and continue to do so.

Some say that Socrates was a philosopher influenced by Judaism, but they offer no proof. Words attributed to him by Plato imply that Socrates was "inspired" from a very early age to "instruct" people in true understanding and belief. But it is not clear if these words are attributed correctly or exactly what his people understood them to mean. Only this much is reliable: Socrates taught in an environment and manner that supports the use of reason.

Professor Mahmud Mustafa's observations of two primitive African tribes confirm what has been said above. He remarks that the Maw-Maws believe in God and call him Mucay. This God is one and only, acts alone, does not beget or is begotten, and has no associate or partner. He is not seen or sensed, but known only through His works. He dwells in the heavens, from where he ordains everything. That is why the Maw-Maws raise their hands when praying. Another tribe, the Neyam-Neyam, expresses similar themes. There is one God who decrees and ordains everything, and what he says is absolute. He makes everything in the forest move according to His will, and sends thunderbolts against those with whom he is angry.

These ideas are compatible with what is said by the Qur'an. The Maw-Maws's belief is very close to what we find in the Qur'an's Surat al-Ikhlas. How could these primitive tribes, so far removed from civilization and the known Prophets, have so pure and sound a concept of God? This reminds us of the Qur'anic verse: For every people there is a messenger. When their messenger comes, the matter is judged between them with justice, and they are not wronged (10:47).

Professor Adil of Kirkuk, Iraq, was working as a mathematician at Riyadh University when I met him in 1968. He told me that he had met many Native American Indians while earning his Ph.D. in the United States. He had been struck by how many of them believe in One God who does not eat or sleep or find himself constrained by time. He rules and governs all of creation, which is under His sovereignty and dependent on His will. They also referred to some of God's attributes: the lack of a partner, for such would surely give rise to conflict.

How does one reconcile the alleged primitiveness of such peoples with such loftiness in their concept of God? It seems that true Messengers conveyed these truths to them, some soundness of which can still be found in their present-day beliefs.

Some people wonder why there were no female Prophets. The overwhelming consensus of Sunni scholars of the Law and Tradition is that no woman has been sent as Prophet. Except for a questionable and even unreliable tradition that Mary and Pharaoh's wife were sincere believers, there is no Qur'anic authority or hadith that a woman was sent to her people as a Prophet.

God the All-Mighty created all entities in pairs. Humanity was created to be the steward of creation, and thus is fitted to it. The pairs of male and female are characterized by complex relation of mutual attraction and repulsion. Women incline toward softness, weakness, and compassion; men incline toward strength, force, and competitive toughness. When they come together, such characteristics allow them to establish a harmonious family unit.

Today, the issue of gender has reached the point where some people refuse to recognize the very real differences between men and women and claim that they are alike and equal in all respects. Implementing these views has resulted in the "modern" lifestyle of women working outside the home, trying to "become men," and thus losing their own identity. Family life has eroded, for children are sent to daycare centers or boarding schools as parents are too busy, as "individuals," to take proper care of them. This violence against nature and culture has destroyed the home as a place of balance between authority and love, as a focus of security and peace.

God the Wise ordained some principles and laws in the universe, and created human beings therein with an excellent and lofty nature. Men are physically stronger and more capable than women, and plainly constituted to strive and compete without needing to withdraw from the struggle. It is different with women, because of their menstrual period, their necessary confinement before and after childbirth, and their consequent inability to observe all the prayers and fasts. Nor can women be available continually for public duties. How could a mother with a baby in her lap lead and administer armies, make life and death decisions, and sustain and prosecute a difficult strategy against an enemy?

A Prophet must lead humanity in every aspect of its social and religious life without a break. That is why Prophethood is impossible for women. If men could have children, they could not be Prophets either. Prophet Muhammad points to this fact when he describes women as "those who cannot fulfil the religious obligations totally and cannot realize some of them."

A Prophet is an exemplar, a model for conducting every aspect of human life, so that people cannot claim that they were asked to do things that they could not do. Exclusively female matters are communicated to other women by the women in the Prophet's household.

#allah#god#prophet#Muhammad#quran#ayah#sunnah#hadith#islam#muslim#muslimah#hijab#help#revert#convert#dua#salah#pray#prayer#reminder#religion#welcome to islam#how to convert to islam#new convert#new revert#new muslim#revert help#convert help#islam help#muslim help

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

My Search for Lost Time in a Slice of Jewish Rye

Was it really as good as I remembered?

My wife was asking. For years she’d heard me rhapsodize about the rye bread of my youth, and now, after decades of privation, I had before me the genuine article: a sandwich on Gottlieb’s rye.

Gottlieb’s Bakery, in downtown Savannah, Ga., had shut its doors in 1994, and I’d left town years before that. It had been more than 30 years since I last tasted its rye bread. It was conceivable that I’d romanticized it in the intervening years.

The sandwich at hand was pedestrian: vegan bologna, power-washed greens from a plastic clamshell, a slice of purple onion and Dijon mustard. But the first, sharp bite of rye was transporting. The last time I’d eaten it I was a carnivore, making Reubens with my mother’s corned beef instead of the tempeh I use now.

The knotty-pine-paneled kitchen of our postwar suburban home was steamy and redolent of corned-beef brine, mingled with the intoxicating waft of rye turning golden in the chrome Sunbeam toaster. My job, which I relished as a teenager, was to carve thin, even slices for the whole family with a finely sharpened butcher’s knife. As the six of us crowded around the kitchen table, the usual banter and bickering gave way to quiet industriousness as we each assembled our sandwiches.

I took the bread for granted. But now I realize that my parents went to some trouble to make that taste of the Old World part of our mid-20th-century American diet. The standard then was packaged factory-made bread from the supermarket.

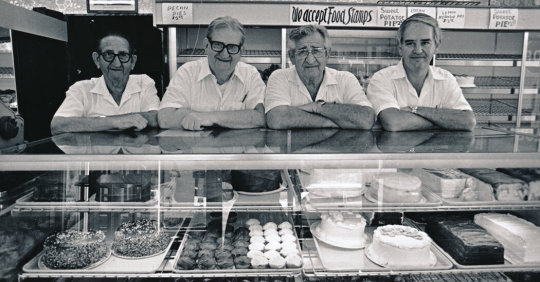

Now and then, Dad would pick up a loaf from Gottlieb’s on his way home from his downtown office, and ask for it to be thinly sliced. As a child, when I happened to be with him, I would watch in awe as one of the Gottlieb men would nestle it in a machine, flip a switch, and a maw of serrated blades would jounce up and down, sawing it into an accordion of perfect slices.

The bread, with its chewy crust and sharp tang, graced school lunch sandwiches of chicken and roast beef. At home, I’d toast it for a shrimp salad sandwich. But there was nothing better than a naked slice of rye for breakfast, toasted with butter; eggs and grits optional.

Finding a suitable replacement was the least of my concerns when I moved to New York in the early ’90s. The city, after all, was the world capital of Jewish baking. It had the best bagels, the best rugelach. The brash, bumptious New Yorkers I’d encountered in college had assured me that everything in New York was “the best.”

On a childhood visit, I’d marveled at the city’s Jewish delis, black-hatted Hasidim and Jewish mayor, all sources of wonder to a boy from Savannah, where Jews were a tiny minority. Surely this city had world-class rye bread.

For years, I sampled the city’s brands and bakeries. One of my childhood friends, a kid named David Levy, had a poster in his bedroom, purloined from a famous ad campaign of the era, of a smiling Black child eating a rye sandwich under the slogan, “You don’t have to be Jewish to love Levy’s.”

I tried Levy’s. I didn’t love it.

I tried the other supermarket brands. I picked up loaves from the best Jewish bakeries on the Lower East Side and uptown. I ordered sandwiches on rye in the famous Jewish delis (“the best!”) in Manhattan and Brooklyn, where I lived. None equaled the rye of my memory.

After a few years, a startling truth began to creep up on me: That rye was a rare thing.

And a corollary: Perhaps, in this case, New York did not have the best.

I stipulate that I do not claim to have tried every rye bread out there. Nor have I carried out a rigorous side-by-side blind tasting. I cannot assert with any objective authority that Gottlieb’s rye was the best in the world ever.

My wife wisely suggested that perhaps the best rye was whichever one you grew up with. I’m sure there’s truth to that. Especially if you grew up in Savannah when Gottlieb’s was around.

Gottlieb’s was the city’s only Jewish bakery. That was not always the case. In its early decades, it had competition from Buchsbaum Bakery, my great-grandparents’ storefront enterprise. My grandfather delivered bread by horse and wagon to the working-class Jewish community on the Westside, then Savannah’s shtetl of striving Eastern European immigrants.

Our family’s bakery did not survive my great-grandparents, but Gottlieb’s, founded in 1884, persevered.

One reason Gottlieb’s endured had to do with local synagogue politics. Savannah, to the astonishment of my Yankee college friends, had been home to Jews since shortly after its founding in 1733. But by the early 20th century, the few thousand Jews had divided into three congregations representing the main branches of American Judaism. And for any communitywide activity, like Hebrew school or day camp, the Orthodox rabbis sought to impose their strict rules on everyone, including kosher food.

One consequence, since Gottlieb’s was the only kosher bakery, was that snack time at day camp was bug juice and a thick, dense Gottlieb’s shortbread cookie.

No bar mitzvah party was complete without a bad local band — a cover of the Doobie Brothers’ “China Grove” was de rigueur — and tables piled with Gottlieb’s goodies: rich brownies, moist rainbow cakes, canasta cakes and iced white petit fours adorned with a silver candy pearl or the name of the boy or girl of honor in blue icing.

In those years, Gottlieb’s rye was part of how my parents cared for my three sisters and me. Decades later, it reappeared when we were taking care of my widowed, octogenarian mother.

In 2018, she was laid low by Guillain-Barré syndrome, an autoimmune disease that kills most people her age. My sisters and I began visiting Savannah in weeklong shifts to help care for her.

During one visit, I learned that two members of the fourth generation of Savannah Gottliebs, Laurence and Michael, had reopened the family bakery in a soulless strip mall on Savannah’s Southside. Shiny and modern, it lacked the flour-dusted ambience of its precursor in the city’s oak-lined Victorian district. But it offered many of my old favorites: pecan sticky buns, cheese Danish, chocolate chewies and, I was delighted to discover, rye bread.

I began tacking a stop onto my visits: I would swing by Gottlieb’s on the way to the airport, pick up two loaves, thin-sliced and double-bagged, pack them in my suitcase and freeze them immediately upon my return. I would then make grilled cheese, tempeh Reubens, tomato-and-mayonnaise sandwiches, egg salad sandwiches and smoked whitefish salad on toast until my stash ran out.

It was the same bread I ate as a child, Laurence Gottlieb told me, the recipe given him by his father, Isser Gottlieb, who ran the bakery, initially with his father and uncle, for more than 50 years. Isser said the recipe was the same one his grandfather had brought with him from Eastern Europe, according to Isser’s widow, Ava.

Jewish-style rye is a sourdough, and that rye tang embedded in my taste memory comes from the starter. Laurence makes his with medium rye flour, water and natural yeast.

The recipe is equally spare: “Salt, yeast, caraway seeds, flour, water and the starter — that’s it,” he said. “The shelf life isn’t there,” he admitted, but that’s not the point.

There had been minor adjustments over the years, not to the heirloom recipe but to the process. The old bakery on Bull Street had no air-conditioning, so the bakers threw ice in the dough as they mixed it to lower the temperature. The starter was mixed by hand in a large bucket, a job no one wanted because it would stick to your skin like wet cement.

Gottlieb’s made deli rye, corn rye, onion rye, seedless rye, rye rolls and marbled rye with swirls of pumpernickel. They were shipped by Greyhound bus to small towns in Georgia and South Carolina that didn’t have their own bakeries, and expressed overnight to devotees farther afield who were happy to pay a premium for a superior sandwich.

Like me, Ava Gottlieb remembers visits to New York City delis that were culinarily thrilling, but the bread disappointing. “It wasn’t because I was prejudiced,” she said. “Our bread was better.”

The original bakery succumbed to supermarket competition in 1994, a victim of the American preference for convenience over quality.

Laurence, now 47, had grown up in the bakery, but had trained to be a chef and was cooking in elegant restaurants. Then one day he happened into a bakery. “I walked in and fell in love with it,” he said. “The odor, the yeasty sweetness of the bakery just does something in my mind.”

In 2016, he opened the new Gottlieb’s bakery with his brother.

In March, our Savannah trips ended. My mother’s assisted-living home barred visitors as the front end of the pandemic edged into view. That didn’t stop my mom from contracting Covid-19, landing her in the isolation ward of an understaffed rehabilitation center. She recovered from the virus but died there, alone, in August after a fall.

My sisters and I flew to Savannah to bury her. The funeral, in a cemetery overlooking the marsh on a warm August morning, was spare. A handful of relatives sat amid rows of empty folding chairs and the insistent sound of cicadas. The rest watched on Zoom.

Before returning to New York, I had one last errand to run. I drove my mother’s battered Toyota to Gottlieb’s.

It was gone.

Part of the shopping center was being torn down. The bakery had been evicted. With the retail market in a tailspin, the Gottlieb brothers had no plans to reopen. The all-too-brief reprise of Gottlieb’s rye was over.

The smell and taste of things, Proust wrote, hold in the “tiny and almost impalpable drop of their essence the vast structure of recollection.” A morsel of madeleine in a spoonful of tea evokes a childhood in a French village; a bite of rye with Dijon mustard calls up mine in Savannah.

In the white-roar silence of the plane back to New York, my mother’s voice was already attenuating in my head, the solid force of her life fragmenting into snatches of half-remembered anecdotes. The rye bread was gone.

It was as good as I remembered.

Multiple Service Listing for Business Owners | Tools to Grow Your Local Business

www.MultipleServiceListing.com

from Multiple Service Listing https://ift.tt/2LNWs5O

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

First meal I made after I cleaned the kitchen for Pesakh turned out to be rather explosive and has sprayed all over onto every surface I cleaned but at least now I have a kosher for Pesakh mess rather than a Khametz mess

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Good And Sweet Year

a/n: in celebration of today being rosh hashanah, i’ve decided to re-share a fic i wrote last year during k’tavnukkah about cristina yang on rosh hashanah. l’shana tova, happy new year, and enjoy!

A Good And Sweet Year

It’s the High Holy days, and Cristina Yang is performing her own version of tradition.

(or: thoughts on cristina, judaism, and routine)

read on ao3 or continue reading below the cut

Cristina’s first completely clear day off in three weeks comes at the end of a several day stretch of the nagging feeling there’s something she’s forgetting. It’s only standing in her kitchen, finally turning the calendar to the new month, that she realizes what she was trying to remember. In her chicken scratch handwriting, the sharpie she had used when she first bought it to mark her holidays, which didn’t come printed in the dollar store calendar she bought when she’d gone on her ‘apartments should have things in them, right’ shopping spree, is the answer. Somehow, in the mad scramble of life, with the hospital and… everything else, the season has snuck up on her.

Today, this one empty, workless, floating day, is Rosh HaShanah.

After a couple moments of just standing there, staring at the calendar, Cristina says aloud to herself and her empty apartment, “Shit.”

For all that she can’t claim to be an especially observant, religious person, Cristina still can’t believe Rosh HaShanah snuck up on her like that. After all, even Catholics who never go to mass know when Christmas is. Maybe it’s because she’s a creature of habit, wearing routine like a sweater from college, comfortable through the hours spent breaking it in, but Cristina has always observed the the holidays, even if just by seeing the day on the calendar and calling her mother and stepfather, or actually buying food from a grocery store rather than a take-out place for once.

By the time the initial ice water realization of what day it is has passed, Cristina has been standing silently in her kitchen for a couple of minutes. Feeling suddenly grateful that she lives alone, Cristina shakes herself and walks into the living room. A newfound purpose guides her steps and she rifles through stacks of magazines and unopened mail, looking for a pamphlet she knows is around here somewhere. She finds it sandwiched between the carcass of the envelope for February’s electricity bill and an invitation to a high school reunion she hadn’t even considered going to.

Temple Beth Shalom is six blocks away from where she lives, and Cristina has been there all of twice. Once, the first night she got to Seattle, abandoning the daunting piles of unopened boxes and the yawning maw of her empty apartment. Putting off moving in completely had been so tempting, and with the justification of getting at least a brief feel for the local Jewish community, it was a good distraction. Plus, it had conveniently been a Friday night. The second time was during a particularly difficult week, both personally and professionally. Cristina’s head had felt so full it might split open, leave her hollow, grey matter on the floor. She had gone for the sense of stillness, for the way Hebrew still worked on her like sedation, emptying her not with a crack and a gutting but a gentle exhale, a calm clarity. It had worked, and she had gone back to work the next day, with a strengthened resolve and the words of the Hashkiveinu echoing in her mind.

It’s not easy to explain, why she does it. She’s been asked, a couple of times, if she’s religious. The answer ranges from ‘no’ to ��I don’t know you well enough to have this conversation’, depending on who asked and how irritated Cristina happened to be at that particular moment. She doesn’t light candles for Hanukkah, or carefully examine grocery packaging for pork derivatives, and she doesn’t pray with the clockwork rhythm of her stepfather’s sister, a woman who exists only in the memory of a rainbow, the words ‘zocher habrit’.

And yet here she is, walking down the chilled fall sidewalk in a nice shirt and slacks, because Beth Shalom has a Rosh HaShanah service in fifteen minutes, and, well, what else was she going to do with herself today? Maybe this is just what she needs right now. A fresh start. A new year. A clean slate and a new beginning from which new mistakes will be made, but hopefully better ones, with the wisdom of experience to backdrop them.

In a lot of ways, Cristina supposes as she sits in the back of the synagogue, the first song beginning, Judaism has a lot in common with surgery. The Torah is read over and over again every year, and it’s mastery, not redundancy. A running whip stitch takes hours to incorporate into your being, hours upon hours. So does Hebrew.

Cristina sits alone through the first of the High Holy Days services, knowing full well she won’t be back for the others. She’s busy, and what’s more, a realist. As she leaves though, the woman at the door smiling and wishing her “l’shana tovah” as she exits, Cristina feels good about having gone in the first place. She can imagine what her friends might say, the weird looks she might get, the way Burke would surely turn this into some exercise in mutual discovery, but she doesn’t plan on mentioning it.

No, this was just for her. This crisp, bright day, the Rabbi’s sermon on choices and new pages, turning to a clean sheet but remembering how the book began, it’s just for her.

On the way home she stops in a corner mart, an impulse sending her in and leaving her walking out with a Gala apple in one hand, a honey stick in the other. The honey is sweet and almost flavorless in her mouth, and she walks slowly, savoring the rare moment of quiet. It’s almost like she can still feel the vibrations of the sounding of the shofar horn, deep in her bones, though she knows that’s medically impossible.

When she gets home, Cristina eats the apple in absentminded bites amongst takeout Chinese food born of years of memories of her stepfather, grinning at her and her mother over a box of orange chicken on Christmas. Holidays meant takeout Chinese, it was one of the most important parts of Jewish culture that Saul had passed on to her, and she held onto that one particularly tightly.

It had meant something a little different to her than it had to Meredith, when they sat on Meredith’s couch over chow mein and fried rice last December and tried to ignore the holiday going on around them. The sharing of traditions changes with the shape of a family, she supposed, as she watched George and Izzie lie with their heads beneath the tree, Alex relegated to folding laundry after he lost at cards.

The next morning, as she heads on her way out the door to work, her earlier breakfast of a protein bar and a slammed mug of coffee mostly forgotten, Cristina snags a bagel as an afterthought. She stands on the ferry and doesn’t feel very hungry, staring down at the bagel in her hands and at the churning water far below it. A distant memory crops up in her mind, a tashlich walk with her mother when she was fifteen. Saul’s voice comes back dimly in her ear explaining how his younger brother had once turned, horrified, to their mother, announcing to her, “mama, the fish are eating my sins!” Cristina has never put much stock in symbolism. She prefers Latin to metaphor, and is pretty sure bread is a pretty poor metaphor for sins anyway.

As she crumbles the bagel in her hand, tossing it bit by bit down into the thrashing waves battering the side of the ferry, Cristina thinks about mistakes. There have been a lot of them. There are going to be more. That is the way it has always been, and it would be foolish and short sighted to think otherwise. But maybe there’s something to be said for trying again anyway.

#grey's anatomy#cristina yang#the rest of magic makes a brief cameo#fic: a good and sweet year#i still love this

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

So I think I did okay at my interview today

So in celebration, please have my full draft of my post apocalyptic sequel to my vigilante short stories. It's quick, brief, but kinda depressing and melancholy. So please be aware this is a bit sad. And then it gets weird at the very end.

Anyway, here it is. Tagging @jogress @akirakan and @renaroo

I scuttled across Home Three, my six legs clattering behind me. My feet sent impulses through me, the texture of the ground mapped with each touch. My main sight however was electroreception, the ability to sense electricity, both organic and inorganic. I could feel pulses, small flickers like stars poking out through bloated clouds.

The world existed in starlight, like dots among an endless void. Not black, not white, not anything that could be adequately described, just an absence. No sound, no light, just little flickers below me, and scattered shards of jewels dulled and faded with dust.

It was all-consuming to my autistic mind. It was a giant maw of emptiness, broken up only by the impulses and sparks of the scattered life that still squirmed and grew. I tried to focus on them, on the tardigrades, on the lichen, on the survivors

When I had to see I could project into Voyager I and II, Opportunity, or Curiosity, Akatsuki, Huygens, Mascot, Minerva II, any of the rest of the still functioning landers — or even the multitude of stranded UUV that dot that oceans. But there still wasn't much to see there, unless I piloted it to one of the vents. At least, there was nothing to see like home. I mean it was home, this was Earth but it ... it didn't feel like it. It felt empty. Only little sprinklings of life.

...I wonder what the Earth looks like now. Like, through eyesight.

I could only stay on Home Three for short amounts of time, it would be selfish too stay here long, even with my planting. I had to look for movement, try to cultivate the octopi and uplift them, and had to salvage on Mars and the Moon. I had felt bad crashing so many satellites, but I needed resources, and I had known they would crash eventually anyway. Might as well aim them by my bodies so I could have metal, circuits, and electronics. Ideally some that had not been fried by the nuclear war.

The satellites of Earth were all gone now, most of them had fried long ago, the rest had been aimed by me to crash either near Home Three or any of the UUV's. Lucas had been very loving to this body, she made its claw very articulate. It had nothing on a human had, but it still could manipulate well. For emphasis I tapped my claw against my back, strumming the plastic card I carried with me. I could almost feel the card, blind as I was.

...I miss hands. It's hard to stim without hands.

I pulled my claw back and dropped it in front of me like a cane. I probed ahead, feeling for anything interesting. Most of the world in front of me was just bits and pieces of electronics, rusted metal - I was no engineer, though Lucas had tried to teach me. I-I had gotten better over the ... decades? I think it had been decades. Probably not a century had passed yet, at least I didn't think so. Point was I still had plenty of machinery to manipulate and try to build with. I had given up making eyes ages ago though, too difficult.

I paused, feeling something under my foot. I stepped back, and with my claw I clasped at the shape. It was rough but patterned. Probably another infertile seed. Still, I clutched it, and scuttled over towards the planting ground.

I had churned and molded this patch of ground for ages, and lichen and other 'plants' had flourished there. Sometimes even lasting long enough to launch spores and seed new life. No large plants ever grew, no matter how many seeds I tried to plant, carried by the wind. Still, had to try, just in case one seed actually worked.

I dug it in, as the light squishy plants pressed against my legs. I paused digging so I could feel the plant, feel the moldable soft surface. I squeezed over and over, before pulling back and burying the would be seed. As I did I could see tardigrades squirming alongside a pillbug, if I identified it right? It was a big creature, it dwarfed the normal wildlife, that was for sure. But electroreception was not as a precise a long as vision.

I finished burying the seed, and clattered away, leaving the oasis behind. Lichen did grow everywhere here, same with mold. But here in my ... garden I supposed, here they actually grew a bit stronger.

I went back through the emptiness, scuffling my feet as my claw draped in front to help me see. I could feel the squishy plantlike life that clung to the ground, feel tardigrades crawled through them. The tiny beasts were common now, some of the most complex life in Mexico. Well, what was Mexico. Now the country was water logged and empty.

This had been Lucas's country. That was what Home Three was, her grave. Where she finally collapsed from the radiation poisoning, my last friend. I had tried to bury her, but my body here was small, weak, it could not ... it could not lift a person, it could not dig the earth enough to bury a human sized body. I ... again I was helpless.

I reached down and squeezed some lichen, letting the soft material ooze through my claws. I padded it, molded it, trying to calm. At least calm as best I could. There was still life here. Animals, plants — life persisted.

I knew in the deeps more complex life lived, mostly sheltered and cut off from nuclear winter. There were shrimp, clams, tube worms, crabs, snails, eels, some ray-finned fish, and even octopi. Octopi! I ... I fixated a lot on the octopi. And not for special interest reasons.

I knew it would take ages for sentient life to evolve again, even with my help. It would even take ages for complex life to recolonize the upper oceans and the surface. But octopi were a good chance for a successor to humanity, they were smart and they had appendages similar to hands and a very complex nervous system. I had used my UUV to contact them, gesturing to them with the machines' mechanical arms, tried to show them things. It felt mostly like failures. But I kept trying. Some of their groups had grasped how to use tools like rocks to smash open clams, three colonies seemed to grasp that meat cooked near the vents tasted better. It was slow going, but they were learning. Some of them anyway, it varied on the species or the group. But some learned, and some even taught each other without my help.

I relied on those teachers. Because otherwise I ... I might have to do something evil. And I did not want to be evil, not now not ever.

I knew they were still a long way from intelligence like humanity had. And it would be a longer time until I can teach them the Torah, or at least what I remembered of it. I remember a lot but I was no teacher, just a superhero in the waning days of humanity. I ... I also felt nervous about converting the octopi, in Judaism we didn't exactly focus on conversion, we welcomed new Jews but we didn't really make it a mission. At least, not my synagogue.

But I just ... I wanted out stories to continue. I wanted the covenant to be honored. I know it was after the end of the world but I ... I still ... I needed to know we survived. I needed us to have survived. And I was just one Jew in an empty world.

I was a superhero once upon a decade, I could project my consciousness into machinery and switch mechanical bodies at will. I was called the Drone, I helped protect people, disrupt lynch mobs, smuggle supplies to vulnerable communities. I was not the best hero, but I tried. And I ... I did some good. At least I had before the world ended.

I rambled a lot, my thoughts drifted and churned wildly. No medicine to help me focus, no mouth to take it either. And no one to talk to except the occasional octopi. Well, them and the things I couldn't really see.

...

I piloted this unmanned underwater vehicle down, nearing the octopi. I had named this group the 'Smoked Twelve' since there were twelve of them regularly together, and they were one of the groups that cooked their clams in the smoking vents. They were very intelligent, they used rocks to smash open then clams, then held them by the boiling vents to cock them and add flavor. I had tried to teach them that, but they did the bulk of the work learning.

They were descendants of one of the first groups I contacted, a group of refugee octopi not native to the vents. Some of the upper ocean life had managed to sink below and adapt, many by feeding off the massive tons of dead sea life from the fallout, much of them still lived there.

Others like the ancestors of the Smoked Twelve moved into the vents as the rotting ocean floor began to shrink and food began to grow more scarce. They were ill adapted to the heat and the dark, but they were smart. And so far they had survived in the vents for three generations, alongside the native species of octopi.

Only Algae and bacteria clung to the surface of the ocean, and their dead sank down. But animal life was rare in the wider ocean, impossible in the irradiated poisoned surface, and still mostly uncommon in the depths, save near the vents. But it was becoming more common. Crabs and eels from the vents occasionally roamed away from the vents to feed on the decaying corpses of animals killed by the fallout of the war, a massive food source with barely any competitors. The octopi followed too, same with the occasional snail and fish. Surface life also came below, breeding and living off the death. There was still a number of food away from the vents, and life was beginning to adapt to that niche.

My mind drifted a lot nowadays. In the present I hovered in front of the octopi, and they drifted towards me, swimming closer. I worried I was taming them, not educating them, they just were conditioned to obey not to learn. But I ... I wanted hope.

I drifted to the floor of the ocean and moved my metal arms down, before I grasped a rock. Then in my other claw I lifted up a second rock. I swam in front of the octopi group, never learned their proper group name, and I bashed the rocks into each other, slowed by the thick pressure of the water. But still the rocks chipped and splintered, forming little pieces of rock fractals.

The octopi mostly just encircled me, so I repeated it again with new rocks. I had been trying this particular lesson for a bit now, a few years I thought, at least with this group. I was no biologist, no scientist, and I wasn't trained to teach animals. I had pets once but they knew no tricks. But I hoped that if I smashed rocks enough, they would begin to learn how to make knives of stone. And that meant cutlery, the ability to give potions of meant, better cooking on the vents, and possibly more food. And more food meant more risks and experimentation.

One of the octopi grabbed a rock — I recognized the older Octopi, it was Lucca. I had named them for Lucas and the inventor from the Chrono Trigger video game - because they were better at understanding things and experimenting than the rest, they seemed to understand more bits and pieces, figure out more of the concepts. They really did the heavy lifting in understanding me. Right now they pounded the rock into the ground, pounding it until it began to shatter.

I had my body's arm release one of the rocks, and then reach out, struggling, struggling to grasp a shard of rock from the collision I caused. I waved my mechanical arm back and forth, trying to grasp, close, almost, nearly there, just got to strain—

Finally I clutched the shard of rock, and held the chunk of thin sharp rock up. The Octopi did not respond, just staring at me blankly. At least I thought the stares were blank.

I took the knife and drifted down towards a crab they had been eating. One of the Octopi swam past me in a burst of speed, and picked up the crab, hauling it away. That was probably the one who had caught it. I stared after the octopi, as it carried the crab to the vents to cook it. I drifted back away, another failed day.

Lucca had bash the rocks together many times before, maybe fifty. They still didn't know it was to make the knife, or how to use it, or why. They knew how to make the tool, that was fine. But cutting open meat, scooping out the insides, they still struggled with that. I rarely got far enough to show them that motion.

Still Lucca still followed after me, even as their fellow octopi went back to their usual routine. So I might as well had tried to take advantage of this moment. I carried my knife with me, Luca following behind, as I reached a clam.

Swallowing I plunged the knife down, scooping at the inside meat, cutting it away. I felt uneasy, icky, but less so than when I first did this process. And I wasn't eating it, so my guilt felt smaller, as little sense as that might make.

Luca stared at me as I acquired the meat, as with my second hand I pulled out the meat of the clam. I threw it to Lucca, who caught it with their tentacle, and began to swim away. I followed them, before they held the meat out over the vent.

They bite into the meat with their beak, tearing it apart in big chomps. I waited more

And then they left.

I followed after her of course, their body shifting and swimming. They propelled bubbles from their sideways jet, launching them father from me than I could swim.

When I finally caught up they were winging a rock around, seemingly playing with it.

Smash! they struck the rock against the ground, it exploding into stars. They swept their tentacles through the debris in a series of whooshing motions, before abandoning the shards and picking up a new rock to smash.

I stared as they smashed that rock too, then another. The pieces gradually drifted to the ocean floor. I had failed again to teach, there was still too much mental distance.

But at least they had a new toy, a new way to play. It was ... disappointing it was so destructive though. But it was only rocks. And I would rather Lucca pounded rocks together than say tear clams apart for fun.

Lucca would teach the others how to play, I knew they would. It was ... back in human days people said you were not supposed to project human qualities onto other species. Human behaviors were not animal behaviors.

But Lucca ... I would almost describe them as a fellow asexual. They were older than the rest, but they had never mated, and they had taught pretty much all of the Smoked Twelve how to cook and how to club clams.

But they were getting older. One day they would ... they would d-die. And then who would teach the next generation?

I was grasping at any wisp of hope I could find, as ridiculous as some of those hopes were.

I drifted back away, there still was hope as the behavior was taught to play with rocks, they would eventually figure out what they could use the pieces for on their own. But again, that was probably asking a lot from the mollusks.

I ... I wished mammals had survived. Or maybe birds. Both kinds of animals often were very smart, had lots of parental investment, especially birds. I ... I would have loved to have worked with a species of crow or raven, they were very intelligent, they understood so much. But the planet was too irradiated, and birds are very sensitive animals to distortions in climate. They all had perished long ago, the brief survivors suffering as the skies went dark and the atmosphere became a poisonous stew.

So I depended on crustaceans, cephalopods, and fish. Most of the fish were not as smart, but I was a vertebrate consciousness, and I still rooted a little for the eels and anglers that lurked in the deep. Crustaceans were already on land, at least if those were animals were types of pillbug. So they also had a good chance in the new world. They were almost unchallenged on the surface in size and power.

Overall, life would take ages to return to humanity's intelligence and power, maybe millions of years. I could wait, but so many nukes went off, and deep down I feared that they had drastically shortened the Earth's lifespan.

There were ... other things on the surface. Strange things. I knew of about five places with movement on the surface. But they did not glow right. One did not produce electricity at all, and I only knew they might be there by the animals they moved away. Others ... flickered faintly. They had shapes, a flow of electricity, but they were not as bright as living things. I ... I almost wondered if they were ghosts of some sort.

...

I screwed in the plates with my salvaged screwdriver. It was a cobbled together mess, bits of exposed wiring was visible, strange hybrids of cameras erupted from the base, and salvaged solar panels sprouted from it like strange metallic feathers.

I called it my Golemoon, because it was a construct I had made crudely on the moon. Crashed satellites, landers, equipment left behind by human expeditions - I took them all and melded them slowly into something like a rover.

It wasn't done, it was never done. But I had taken apart so many satellites and landers, both on asteroids, Mars, and on Earth, that I had figured out bits and pieces. It was slow, I wasn't that smart, but I had had decades to learn.

I pulled Yutu back, letting my camera take in the sight. I had found the Chinese rover in good shape, surprisingly good, she just needed some repairs on hand with a human intellect. It took some effort, it was hard to manipulate tools with the other rover's arms, but I still managed to fix her, and she now was my main hands on the Moon.

I refused to take apart Yutu, I needed hands after all, but even when Golemoon was completed I wouldn't dissect her. She was ... she was a human invention, a countries first landing on the moon. I couldn't bring myself to kill her.

The Golemoon was not done. It might never be done. Again I was no scientist, definitely not a engineer, I had just taught myself with what mechanical knowledge Lucas had shared. And I was never sure if that was enough.

Sometimes I tried to boost my confidence by reminding myself I was the smartest human alive. I then remembered I was also the most incompetent, and I ended up feeling just as useless.

I backed up Yutu, before turning to gaze towards Earth. It was white with pus, thick clouds blocked much of my view. There were cracks, but from here I couldn't see those peeking beams of sunlight. All I could see was a large fog blotting out the planet.

I wheeled again, to my wall. With my crude claw, built with parts from other rovers, I grasped at the ground, before picking up my rock. I wheeled over to the Plain of Memory, and began to carve again.

I sculpted words, first in Hebrew, then English, then the pidgin Lucas taught me. It was mostly based on Spanish, but with more Mayan and Aztec words mixed in than in the usual Mexican version of Spanish, along with some grammar. She had engineered the pidgin with help from Riccardo, as a sort of code for the three of us to use on her missions, and also to take pride in her Maya-Mexican heritage.

Lucas Rodriguez was the superhero called the Grasshopper, she could leap a good six yards into the air, kick people scores of feet away, and she had retractable armor resistant to most weaponry. Riccardo was her superhero mentor, and I helped scout for her and kept her in contact with the other superheroes on Earth.

I had written about her of course, about the Silken Seer, about Lightning Bug, Cadena, Slick, the Asper, Alchemy Man, my fellow heroes. And I also wrote about the history of our world, our mistakes, our triumphs, the discoveries, the genocides, the hate that destroyed humanity, but also our evolution, our relatives like chimpanzees and bonobos, our beliefs, as many as I could summarize well. It was a mad scribbling with little order in what I wrote, but it kept growing.

I knew a meteorite could shatter my work, but as long as I could I would repair it, keep the stories going. I had wanted to be a writer before I got my Power, and this was the most important story. Though the parts I told as a story were a bit ... altered to fit narrative flow better. As in I worded them differently.

I kept writing, today I was repairing a story about Mu'lan, it had gotten damaged recently. It was a nearly word for word translation of the original ballad, I knew it by heart. I knew we as humans were supposed to be wary about interpreting other cultures, but the last line about the hares, I viewed her as genderfluid. So it had been a source of strength growing up, that trans heroes existed for well over a thousand years.

I wasn't sure if the Octopi would understand gender, or if their future society would. Assuming they could and would develop a society, it would be alien to human society. If I told them I was a trans woman they would probably be confused about everything in that concept.

I continued to carve it, ugh I wish I knew Chinese. Mandarin, Cantonese - any Chinese dialect would be good. More people lived in China than anywhere else during the Fall of Man, and they were one of the sides in the war. They had less bombs, but not many were needed.

My former country was the other side. We had ... there were so many superheroes in the end because we were fighting against an evil dictator - elected with the aid of hateful monstrous bigots who wanted the extermination of anyone not like them. The election was tampered with by a hateful foreign dictatorship, who used our nation as a puppet.

In the end of a tyrant who couldn't understand restraint and a budding world power with everything to prove clashed, and the world ended in first fire, then snow, then rock.

In February 17th of 2018, that was the day of the Fall of Man happened. It felt like only the space of a few hours. Then for the next three years as the atmosphere turned thick and bloated and the surviving humans died off of starvation and radiation poison, an asteroid plowed into the Earth, finishing off the rest.

Humanity had known that asteroid was coming nearby, but with the planet's orbit destabilized by the hundreds of nuclear explosions, the planet was thrown closer towards the asteroid, letting it smash through and devastate the rest of the planet.

Now tardigrades and pillbugs ruled the surface, while in the depths octopi, eels, and crabs ruled. The smartest remaining species were some of the octopi, but it would probably take millennia at rest for them to understand things.

I pulled back from the Plain of Memory, the repairs were done. I roved away from the site, before pulling over to stare at the collection of writings scribbled onto the lunar surface. Just to take it all in. If Yutu broke down, I would want to have a full view of the writings.

I paused, before projecting out of Yutu. I flew about, the moon becoming an empty space with only a few lights flickering. I could not see the Moon itself, nor the Earth, I just could see the storms of Earth, flashes of radiance.

I flew back towards the storms, back towards the body Lucas made me. I had a couple ways of helping find bodies, I had a sorta of sense of where my former bodies were, like a spatial memory. I could find new bodies through electroreception too, I had the sense mostly when I was outside of bodies, only the body Lucas made me let me harness that sense.

I drifted suddenly. There was ... among the hum of plantlife drifted one of the "ghosts" I sometimes saw. But it ... it was far away from the other ghosts of its type. It was swinging its arms back and forth like ... like it was rowing.

The flickering unstable image was not of a human, but of a monkey. Like ... like a gibbon. I could only see its bioelectricity, and I could only see it flash. Again like it ... it wasn't real. There were many monkey ghosts, they were about the most common I could see. But they all clumped up in the remains of southern China, at least I thought it was China, it's hard to tell when you can only guess by the outline of animal life, the location of water, and the position compared to Mexico.

Regardless this ghost of a monkey was far to the East of their normal home, closer to my pillbug body. So then, it was sailing. Over the ocean.

I decided to risk it, and flew into a UUV, one close to the surface. I could not program, but I could give simple orders. She would rise up and head to where I see the monkey ghost, crude as this was I ... I needed to see if I could genuinely see these flickers. Because if they were real and not hallucinations, if there were mammals, not only mammals but tool using primates — oh I could check. Finally I could put the monkey business to rest, and the fear that I was going insane from loneliness, lack of a body, and lack of medication could finally be faced.

I was scared but ... this opportunity was right in my grasp, I had to face it.

Finally I sank into the little pillbug lobster creature of a body, feeling the soft squishy lichen against me feet. I scuttled away, might as well check on that seed, it was probably not awoken yet, even if it was fertile, but I had to check.

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Virtue of Meaningless Bourgeois Religion (Ancient Judaism) (Max Weber)

“Meaning” can sometimes seem like it is all the rage around some corners of the contemporary Jewish discourse, particularly in relation to religion and ritual. “Have a meaningful fast.” “What is the meaning of life?” “The synagogue seems to so many to be utterly devoid of meaning.” You get the point. “Meaning” is not a term that I use much. In the various worlds of contemporary theory, the very concept is retardataire. “Meaning” is tied up with language, semiotics, symbolism, and other theoretical themes left behind in the turn away from the linguistic turn. Reading Max Weber confirms why we might be better off without the pretentious term.

Doing due diligence for the Religion Studies Theories and Methods Seminar brought me to Weber’s Ancient Judaism. Weber, of course, was very interested in “meaning” precisely because he thought we lived in a meaningless world. This is in the definition of basic sociological terms in the opening chapter of the massive Economy and Society. For Weber, meaning is only a subjective ascription assigned to social action. Weber’s study of ancient Judaism re-enforces that subjective-social definition of meaning that is rational and humane.

Not so interesting about Ancient Judaism is the way the book is intended to shore up Weber’s thesis about the origins of capitalism in the Protestant west. Setting aside the anachronism, part of the point is to argue against Sombert and maybe Marx that the Jews and Judaism are unimportant engines of modern capitalism. Weber argues that the pariah status of the Jews does not lend itself to capitalism and that, in Judaism, the study of law and ritual practice are more important than making money. At the same time, Weber sees in the religion of ancient Israel a precursor form of rationalism that he contrasts with the religions of India, as well as the cosmo-theology reflected in the religions of China. In the Hebrew Bible the world is not fixed, not mystical, not magical, possessed of no “meaning” beyond history and human action. To be sure, one can inquire about the divine purpose, the anger of God, etc. But “[b]eyond that, there was nothing. This presupposition indeed, precluded the development of speculation about the ‘meaning’ of the world in Indian fashion” (p.225, cf. pp.206, 313, 317, 398).

Based on a picture of a world without meaning, Weber’s thoughts about the flat affective character of Israelite religion are utterly disenchanting. After Buber and especially Heschel, the argument seems counter-intuitive, indeed contradicted by charismatic prophetic visions of a world saturated by meaning, by the pathos of God. I am suggesting here that to grasp this part of Weber’s argument depends upon a recognition of ancient Israelite texts as literary art-objects. Indeed, reading such texts leaves one with two alternative interpretations. One possible interpretation is that the prophetic text reflects that real, overpowering of some immediate religious experience, reflecting the actual pathos of a great religious affect that saturates the prophet. An alternative interpretation is that the prophet is a literary persona and that prophetic books constitute no direct recording device of some intentional subjective state of lived consciousness, but is itself a carefully crafted poetic device. In support of the latter possibility is what Weber identifies as the suppression of prophecy by the “bourgeois” priests in the history of ancient Israel (pp.380-2). In like manner, the hot expectation that would seem to animate in our sources the idea of the future redemption is recognized by Weber to have been ultimately compressed into the limiting frame of “soulful longing” (p.399), a subjective state with no genuine objective meaning apart from its own expression. Weber also insists that what others will later call the messianic idea in Judaism is a strictly religious one, not political. In line with the argument in “Politics as a Vocation,” prophets are not politicians. Weber’s data for ancient data is primarily textual, which calls attention to the artful compression of literary-religious expression beyond which they “mean” nothing.

A takeaway from reading Weber’s analysis in Ancient Judaism is that “meaning” is as overrated a phenomenon as the bourgeoisie is an underrated one. The concluding pages to Ancient Judaism indicate the power of endurance enjoyed by this particular religious form. Weber speculates that the appeal of Judaism in the ancient world to converts, especially after the collapse of Hellenic states, was the grand and majestic idea of God, the elimination of cult deities, a vigorous ethic, and a fixed order of life offered by ritual (pp.419-20). In the self-formation of this pariah people, prophecy and ritual contribute to the making of an exclusive “confessional association” (p.336). Viewed from an opposite perspective, the failure of Christianity to convert the Jews was due to what Judaism had to offer the members of an exclusive “confessional association,” namely a stable tradition and structured way of life, “the strength of the firmly structured social community, the family, and the congregation.” These closing words to Ancient Judaism read like a paean to the bourgeois virtue of the Jews. “All of this,” he wants his readers to appreciate, “makes the Jewish community remain in its self-chosen situation of a pariah people as long and as far as the unbroken spirit of the Jewish law, and, that is to say, the spirit of the Pharisees and the rabbis of late antiquity continued and continues to live on” (p.424).

Has Weber confused the religion of ancient Judaism with the rabbis or with the modern synagogue? It will help to remember that Das antike Judentum is itself a period piece. It appeared in the 1917–1919 issues of the Archiv fur Sozialwissenschaft und Sozialforschung right in the midst of and after the maw of the Great War. Consider too the simple decorative device on the front cover of the 1952 English translation. I might be overreading Weber’s thesis, but would argue that he encourages us to consider the religion of ancient Israel as priestly, bourgeois, and rational, not prophetic, radical, and mystical. The same goes for the modern Judaism of his day. In the face of catastrophe, the legacy of ancient Judaism and the picture of modern Judaism would be that of small comfort and humble virtue of social association in a meaningless world.

http://ift.tt/2hZ21zv

0 notes

Text

About

Hi, I'm Maws! he/him or it/its

I've fallen in love with Judaism over the years and the closer I got the more certain I became that it is where I was always meant to be. So now I'm just trying to find my way home.

I hope to convert Orthodox one day but I'm gay and trans so I've decided to not make the search for a rabbi harder than it needs to be.

My boyfriend is Modern Orthodox and the first thing I wanna do after I convert is marry him but I'm not converting to be with him, I'm converting to come home, and I happen to have already found the person I want to share that home with. Not to mention, I may never have found the courage to believe I deserved to come home if not for his support. Every day I thank Hashem for the circumstances that allowed us to fell in love and I hope I also show gratitude to my boyfriend for in turn helping me find Hashem (to be clear he was NOT proselytizing, I was asking and almost begging for it).

Please tell me things, infodump, tell me about Torah, tell me a Talmud story, tell me all your Jewish opinions I love learning and my favorite way to learn is listening to people talking about something they care about. There is so much beauty in this world in knowledge and diversity and passion let's share it and oh gosh I need to stop rambling I've been writing this for an hour and I only meant for it to be something short to put as my description. Final fact about me is I can't shut up.

שלום!

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

(context)

I reached tag limit on that one but I wanna talk more about the two realizations I had during it (but also I'm super tired and this will be short)

First the Judaism thing cuz. Huh. I guess I do actually do a bunch of stuff I didn't even mention all the little ways it defines my routines. It's been over three years and I still don't have a rabbi and my ADHD makes it so bloody hard to even get the bare minimum progress done by writing a freaking email. Which leads to the ADHD self hating spiral we all know and loathe. But at least I keep kosher. At least I wear my kipa. At least I say Mode Ani and Hamotzi and Shehakol (and other applicable brakha on the very rare occasion that I actually eat a plant that still looks like a plant). At least I color code my kitchen and separate meat and dairy. At least I wash my hands before bread and at least I don't travel on Shabbat and at least I let little pieces of Judaism shape my days. I have a long way to go and I'm going much slower than I like. But. I'm not where I started. Where I started, keeping kosher, even just excluding pork, seemed impossible. Now it's my daily routine I don't think about.

Secondly and less significantly I suppose. I think I described my NPD the nicest way I've ever heard thanks to that post. It's about love actually. Yes I'm constantly in need of attention and acknowledgement of my abilities and yes I have unfair hierarchies in my head that always put me on top and yes NPD interferes with my ability to function in various ways. But! It's about love actually. Many of my friends throughout the years have seen me as very affectionate and to some I've been very very affectionate. Why? It wad narcissism. They paid attention to me and praised me and I loved them. If you give me attention I am full of love. And what is attention anyway? I like it in weird ways and more than others but most people want and need it to some extent because social animal. And that's love too, isn't it? NPD is about love actually (JOKE. EXAGGERATION. MANY PARTS ARE NOT SO NICE THAT'S WHY IT'S A DISORDER I AM NOT TRIVIALIZING THE DISORDER) (personally I am the epitome of a "sore loser" if you make me lose and I can't blame you for cheating or claim I wasn't trying I will want to kill everyone in the room and then myself and that part is barely an exaggeration I cope by never ever competing at anything I can lose)