#Lankhmar: City of Adventure

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

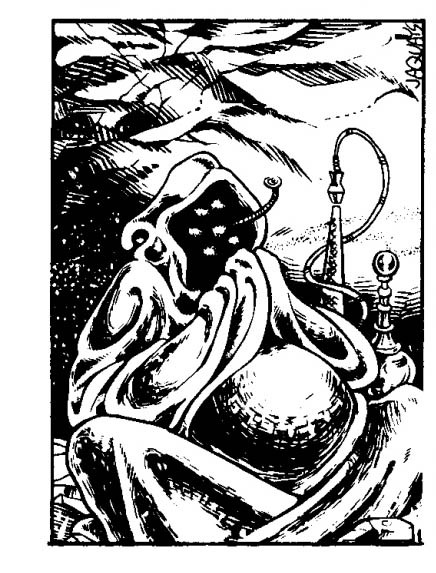

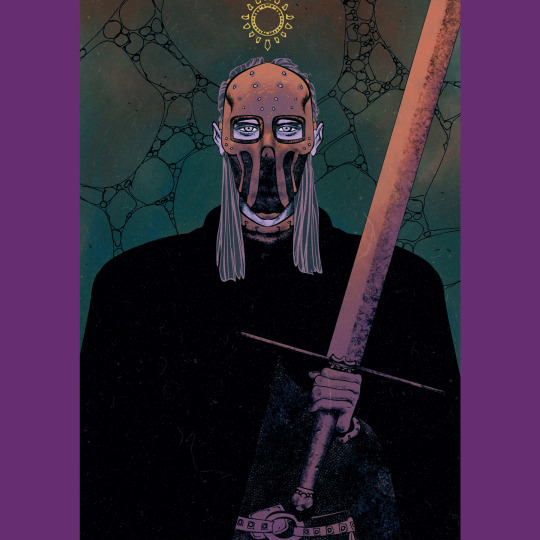

Jannell Jaquays, portraits for TSR's Lankhmar: City of Adventure

#monochrome#Jannell Jaquays#Lankhmar: City of Adventure#Lankhmar#Nehwon#Fafhrd#Grey Mouser#Ningauble of the Seven Eyes#Sheelbar of the Eyeless Face#Kreeshkra#ghoul#Gods of Lankhmar

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

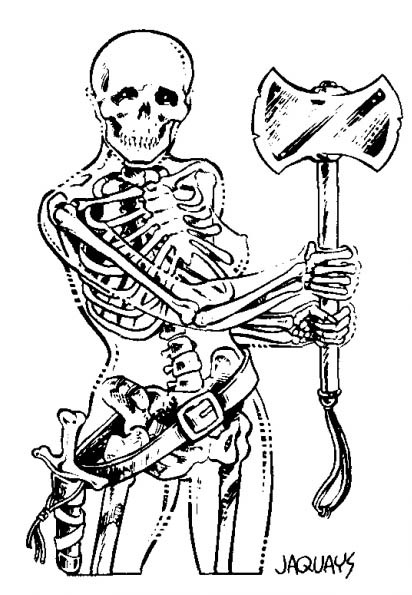

Lankhmar: City of Adventure Cover Art by Keith Parkinson

#Dungeons and Dragons#Dungeons & Dragons#D&D#Lankhmar: City of Adventure#Covers#Cover Art#Keith Parkinson#Fantasy#Art

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

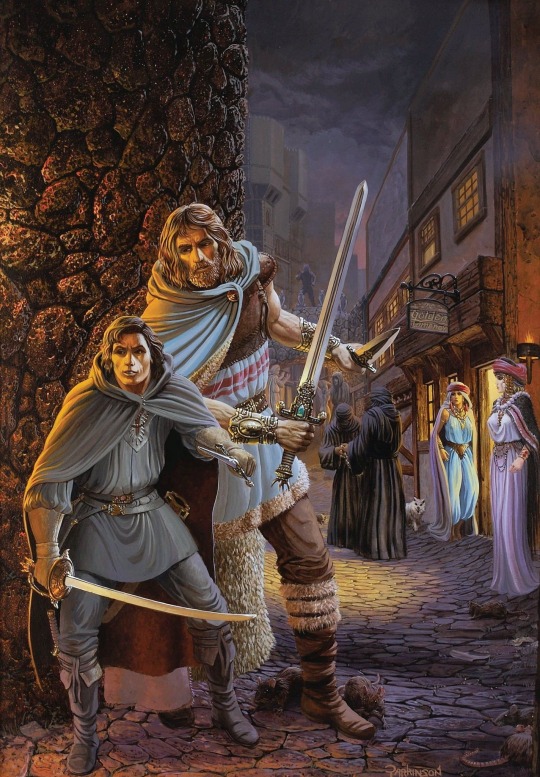

#Lankhmar #Nehwon, in excellent condition, for Advanced #DungeonsAndDragons, is now available! #ttrpg #dnd #CityOfAdventure #originalprint #outofprint #TSR #secondedition #2e #NiksRPGs

#ttrpg#niksrpgs#original print#out of print#dnd#dungeons and dragons#2e#second edition#lankhmar#city of adventure#tsr

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

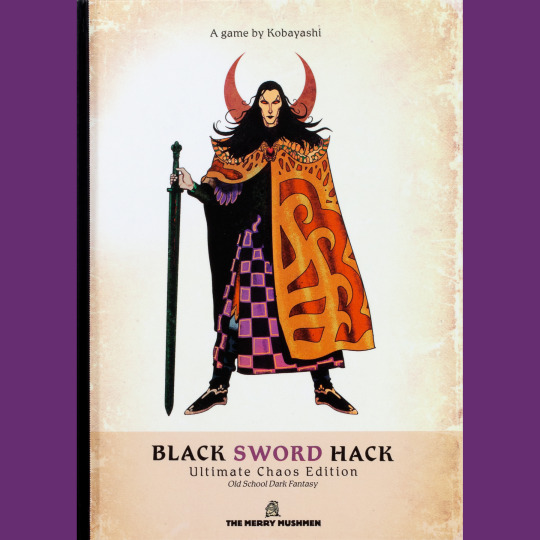

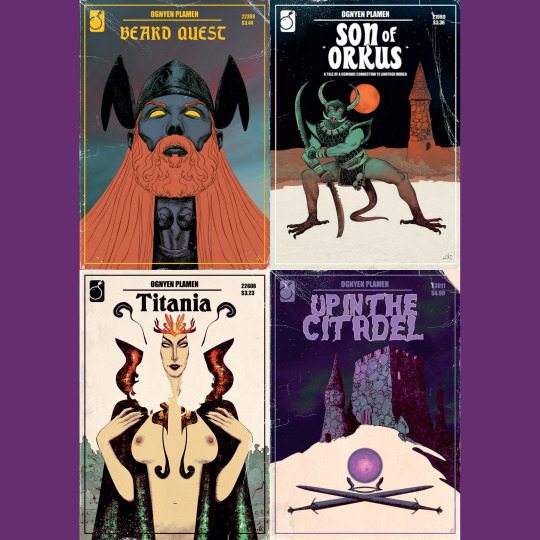

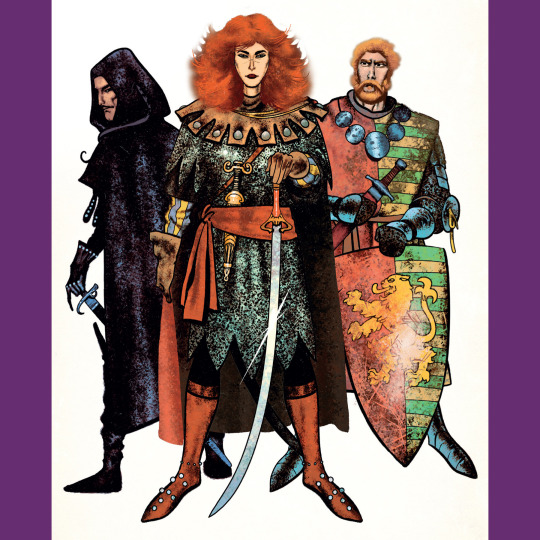

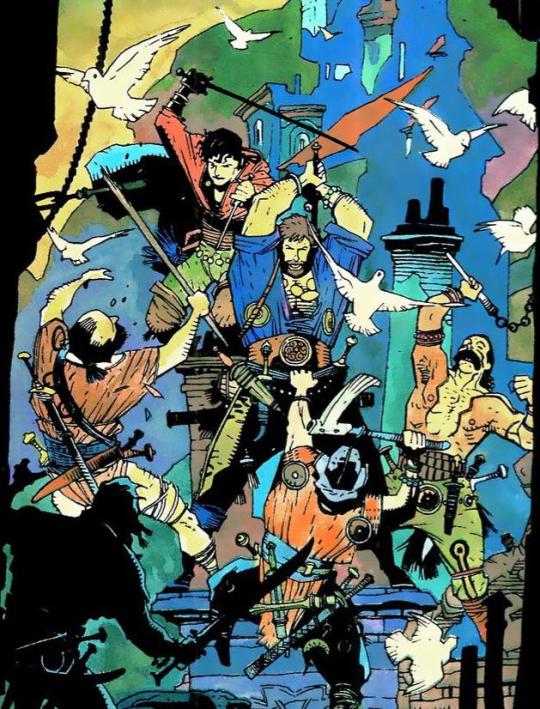

Black Sword Hack: Ultimate Chaos Edition (2023) is a beautiful little system derived from David Black’s Black Hack of D&D. The obvious literary touchstone is Elric and Moorcock’s larger cosmic conflict between Law and Chaos. There are many other clear influences, though — Jack Vance’s Dying Earth, Lankhmar, Kane, Poul Anderson. I suspect that is Jirel of Joiry on the back cover, flanked by Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser. Perhaps they’re a trio of entirely different people — Goran Gligovic’s art vibrates on strange frequencies, as if you’re looking at archetypes from a parallel universe.

The core systems work essentially as they do in Black Hack, so I won’t go into them here. The additions contribute to the doomful atmosphere. These amount to a set of different sorts of pacts — demons, evil swords, fairies, and so on. There are a varieties of powers to draw on and be consumed by.

The rest of the book is given over, mostly, to tools for collaboratively creating a world and a central city for players to inhabit, explore and, eventually, ruin and destroy. Goes with the territory, really. A couple scenarios round things out. A fantastic appendix lays out a method to create adventures using your favorite paperback fantasy novel.

Black Sword Hack touches on many of the same themes as Chaosium’s Stormbringer, but in a more minimal, smoother sort of way. It’s more direct, really. It’s also its own thing, and every game is unique, thanks to the world generation. I’m keen to see it develop further.

546 notes

·

View notes

Text

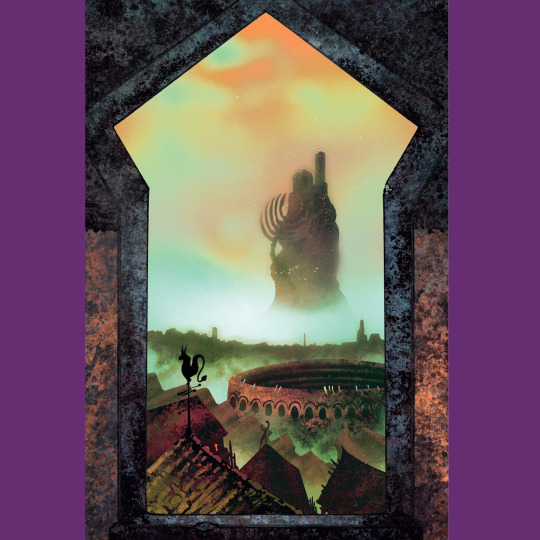

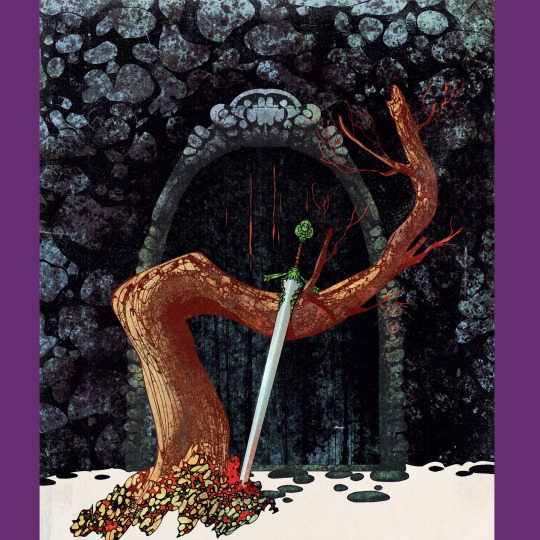

481.1 - Jeff Easley - Illustrations for Lankhmar: City of Adventure (1985)

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

I'm thinking of Planescape again aND the most interesting part of it, Sigil. It has big issues where low level adventures have no impact and high level ones feel mundane. And city adventures are an art that can hardly be passed down.

To run a good city adventure you need a good picture of the city and what's going on in it but that picture, when put down in print, makes a crappy vook.

But say you have it. What do the players do? I think the answer is fang fights and raids on guildhalls, and later on, wild heists. It should be Lankhmar on steroids. You know how Fafhrd and the Mouser fight some weird demon shit every story, it's like that but those demons are in the open and everyone has a problem with them.

Did you know planescape was supposed to compete with shadowrun and Cyberpunk? And thats TSRs reason for making it? Thats what I heard. With that in mind it makes sense that faction play is emphasized in the better Sigil supplements and in Planescape Torment.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lankhmar City of Adventure

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Time is an agony of Now, and so it will always be”: Moorcock’s Pillar of Heroic Fantasy

Art Credit: Steven Craig Hickman on ArtStation

“The Dreaming City” by Michael Moorcock depicts a wide scale fantasy world in a short amount of time but overall does this very successfully. This work was the first story to feature the widely popular character of Elric of Melniboné, inspiring other stories and appearing in later works by Moorcock such as “The Bane of The Black Sword” which helps explain more of the world created by this short story originally published in the magazine, Science Fantasy. While the character of Elric is very different from what we would usually consider a “hero”, this work of heroic fantasy demonstrates the complexity of the genre in a not-so-overwhelming way. In addition, the descriptive writing style and immersion help the audience fall easily into the fantasy world, making this one of the most accessible and relatively simple fantasy stories to pick up by anyone who has interest in the genre.

The story essentially follows Elric, a troubled individual that is bound to his sword, Stormbringer, by some sort of dark magic or maybe a pact with a demon we later see named Arioch. Our “hero” has a central journey to seek revenge on his cousin, Yyrkoon, and save his love interest, Cymoril. He plans this quest with the help of others, such as side characters like Yaris, who will raid the city of Immyr where Cymoril and Yyrkoon are located. Past an initial confrontation between Elric and Yyrkoon, the audience is placed right on the ships of the raiding party against The Dreaming City, nicknamed this due to most of the inhabitants being in drug induced sleep. While the initial raid worked well, Elric ends up killing Cymoril due to the uncontrollable Stormbringer in his final duel against Yyrkoon, leaving his quest at an abrupt end. Upon escaping from the dreaming city with a heavy heart, Elric and the raiding party are met with vessels that were waiting for them to leave and with quick thinking, Elric tries his best to save himself against these superior ships. The troubles for Elric and the party do not end there, however. Creatures that can only be dragons start to attack and leave most of the party dead. After this attack, Elric tries to throw his cursed blade into the water he still sits on but it doesn’t seem to want to part with him. Accepting this parasitic relationship, Elric regroups with what remains of the party and prepares for whatever adventure lies ahead.

Fantasy is a genre that seems to struggle with putting such a fantastical world in perspective to the reader. Other fantasy works that I’ve read, mainly “Lean Times in Lankhmar” by Fritz Leiber, focus so heavily on establishing a massive world in such a short time using confusing terminology and expecting one to understand what the author is meaning. From the very beginning of “The Dreaming City”, the world around the characters is well established but pleasantly brief. The introduction of the short story puts the setting in our world just before current empires in our history like India or Egypt. Personally, this grounding of fantasy with history helped me imagine the setting a lot better than just throwing me into a strange world. Moorcock even explained that this story happens “Ten thousand years before history was recorded–or ten thousand years after history had ceased to be chronicled”, giving us a time period of the story as well and further letting the audience imagine where we are historically. Past this historic perspective, we see very vivid descriptions of places within the world. For example, when Elric first arrives to Immyr in chapter two of the story, we get a gorgeous description of the city from his perspective and from this, we encounter some hints about our main character's past, further allowing the reader to imagine the world and immerse themselves. Moorcock seems to be a big fan of describing the colors and personally, this helps greatly when imagining the environment that the story is set in.

The vivid descriptions go beyond just the environment, however. Throughout the short story, the reader gathers additional information of what Elric himself looks like. Overall, Elric is said to be the opposite of what one would think of for a “hero”: a frail, albino man that must satiate his sword's need for bloodshed in order to keep his health and supernatural powers. Through the work, we get more details about this character, such as his “youthful eyes” or his attire. These descriptions extend beyond the main character, describing the creatures of the world as well. When the raid party encounters dragons in chapter four, the reader can imagine exactly what these beasts look like without having prior knowledge.

The aspect I appreciate the most about this story and Moorcock specifically is how he slightly diverges from what’s already established in the fantasy genre. When we think of a hero, we usually imagine a muscular man with flowing hair and set morals that helps everyone. Moorcock's “hero” is almost the complete antithesis of this idea but we as readers almost sympathize with Elric. This makes the story stick out in a way that no other work of fantasy has for me. Going back to the dragons mentioned in the story, they are unique as well due to their ability to spit venom rather than fire and smoke. There is a sense of familiarity in this work but at the same time, there are fresh ideas that I’m sure had audiences wanting more of this world and everything in it.

Overall, I absolutely loved “The Dreaming City”. When trying to think of any quarrels I may have with this work, I couldn’t think of any that really stood out to me. It is a little lengthy for a short story, but it tells such a vibrant world that was definitely worth reading. Because of the uniqueness of Moorcock’s writing, I have found a love for heroic fantasy literature and while I’m still learning how to appreciate it more, this is an amazing start for anyone who may be interested.

Works CitedMoorcock, Michael. “The Dreaming City.” The Big Book of Modern Fantasy, edited by Ann VanderMeer and Jeff VanderMeer, Vintage Books, 2020, pp. 102-119

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

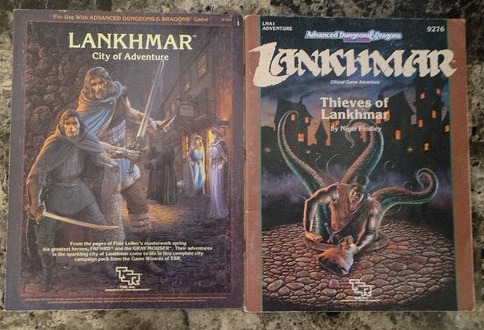

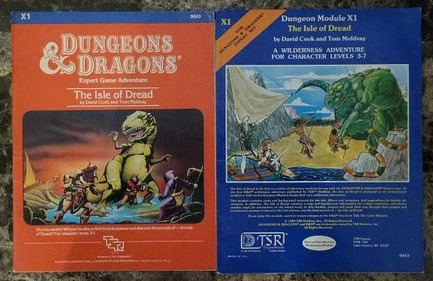

Dragonfinds got some new books today for DND adventures. I got both copies of The Isle of Dread, Legions of Hell, Tales of the Outer Planes, Lankhmar City of Adventure & Thieves of Lankhmar.

#DND#TSR#minatures#dragonfinds#dungeonsanddragons#dungeons and dragons#rpg#ttrpg#dnd1e#dnd2e#odnd#adnd#lankhmar#planescape

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Books I’ve read (2024) - 32

American Prometheus: Oppenheimer, by Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin

Hirohito and the Making of Modern Japan, by Herbert P. Bix

Personal Politics: Sexuality, Gender, and the Remaking of Citizenship in Australia, by Leigh Boucher et. al.

The Mists of Avalon by Marion Zimmer Bradley

Winterlight (#7), by Kristen Britain

Spirit of the Woods (7.5), by Kristen Britain

Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, by Lewis Carroll

Campaign: Austerlitz 1805, by Ian Castle

Scarlet (#1), by Genevieve Cogman

Rubicon, by J. S. Dewes

Elite: Napoleon’s Commanders (1) c.1792-1809, by Philip Haythornthwaite

Ship of Magic (#1), by Robin Hobb

Song of the Huntress, by Lucy Holland

Pax, by Tom Holland

The French Revolution and Napoleon: Crucible of the Modern World, by Lynn Hunt and Jack R. Censer

Babel, by R. F. Kuang

The First Book of Lankhmar (#1), by Fritz Leiber

The Mirror and the Light (#3), by Hilary Mantel

Teixcalaan Duology: A Desolation Called Peace (#2), by Arkady Martine

The Stranger Times (#1), by C. K. McDonnell

Unruly, by David Mitchell

Gideon the Ninth (#1), by Tamsyn Muir

Harrow the Ninth (#2), by Tamsyn Muir

Nona the Ninth (#3), by Tamsyn Muir

Anno Dracula, by Kim Newman

A Deadly Education (#1), by Naomi Novik

Tiffany Aching’s Guide to Being a Witch, by Rhianna Pratchett and Gabrielle Kent

A Stroke of the Pen, by Terry Pratchett

Napoleon the Great, by Andrew Roberts

Shogun (The Life and Times of Tokugawa Ieyasu: Japan’s Greatest Ruler): by A. L. Sadler

Hyperion (#1), by Dan Simmons

The Dawnhounds, by Sascha Stronach

Currently Reading

Stormlight Archive: Word of Radiance (#2), by Brandon Sanderson

I’ll get to these someday

Liberating France: 3rd Edition, by Judy Anderson, and Allan Kerr

Foundation (#1), by Isaac Asimov

Against All Gods, by Miles Cameron

Shanghai Immortal, by A.Y. Chao

The Storm Before the Storm, by Mike Duncan

The Silk Roads, by Peter Frankopan

I, Claudius (#1), by Robert Graves

Campaign: Gallipoli 1915, by Phillip J. Haythornthwaite

The Creeper, by Margaret Hickey

The Mad Ship (#2), by Robin Hobb

Ship of Destiny (#3), by Robin Hobb

Fool’s Errand (#1), by Robin Hobb

The Golden Fool (#2), by Robin Hobb

Istanbul, by Bettany Hughes

The Rise of Kyoshi (#1), by F. C. Lee

The Shadow of Kyoshi (#2), by F. C. Lee

The Penguin Book of Classical Myths, by Jenny March

The Romanovs, by Simon Sebag Montefiore

The Deed of Paksenarrion, by Elizabeth Moon

36 Streets (#1), by T. R. Napper

Ghost of the Neon God (#2), by T. R. Napper

Spinning Silver, by Naomi Novik

Buried Deep and other short stories, by Naomi Novik

Velocity Weapon (#1), by Megan O’Keefe

The Blighted Stars (#1), by Megan O’Keefe

Saevus Corvax Deals with the Dead (#1), by K. J. Parker

She Who Became The Sun, by Shelly Parker-Chan

The Gormenghast trilogy, by Mervyn Peake

Howling Dark (#2), by Christopher Ruocchio

Mistborn: The Lost Metal (#7), by Brandon Sanderson

The Stormlight Archive: Edgedancer (#2.5), by Brandon Sanderson

The Stormlight Archive: Oathbringer (#3), by Brandon Sanderson

The Stormlight Archive: Rhythm of War (#4), by Brandon Sanderson

The Bone Season (#1), by Samantha Shannon

A Day of Fallen Night, by Samantha Shannon

The Bone Shard War (#3), by Andrea Stewart

The Book of Witches, by various authors, edited by Jonathan Strahan

City of Last Chances (#1), by Adrian Tchaikovsky

Service Model, by Adrian Tchaikovsky

Shigidi and the Brass Head of Obalufon, by Wole Talabi

Early Modern Japan, by Conrad Totman

Wild Dogs, by Michael Trant

Heroic Fantasy Short Stories (Anthology), by various authors

1 note

·

View note

Text

Lean Times in Lankhmar

Lean Times in Lankhmar, by Fritz Leiber, is a story of two ex adventurers The Gray Mouser and Fafhrd. The two had parted ways and now reside in the city of Lankhmar where Mouser has joined the thieves guild under its leader Pulg, and Fafhrd has joined the temple of Issek of the Jug under priest Bwardes. Fafhrd unexpectedly causes Issek of the Jug to go from being a lower end God in Lankhmar to incredibly popular, and with this new popularity Pulg and the thieves guild decide to extort the temple. Mouser talks to Fafhrd of Pulg’s new target in an attempt to stop things before they get out of hand; it doesn’t work. Pulg sends Mouser to remove the current obstacle that is Fafhrd and Mouser does so by getting him incredibly drunk, but Pulg appears before the black out drunk Fafhrd as he no longer trusts Mouser due to a previous lie of Mouser’s coming to light. Fafhrd is then shaved and tied to a bed frame by three of Pulg’s men. The five members of the thieves guild show up to the temple the next dawn ready to extort Bwardes when a drunken, shaved, tied to a bed frame Fafhrd shows up yelling “WHERE IS THE JUG” which causes the people of the temple to believe he is Issek himself and they go mad. After a scuffle between Pulg’s henchmen, Fafhrd, and Mouser attempting to save Fafhrd, quite a bit happens. Pulg takes over as vizier of Issekianity which is then said to fail horrifically within three years, and Mouser and Fafhrd Reunite as adventuring companions.

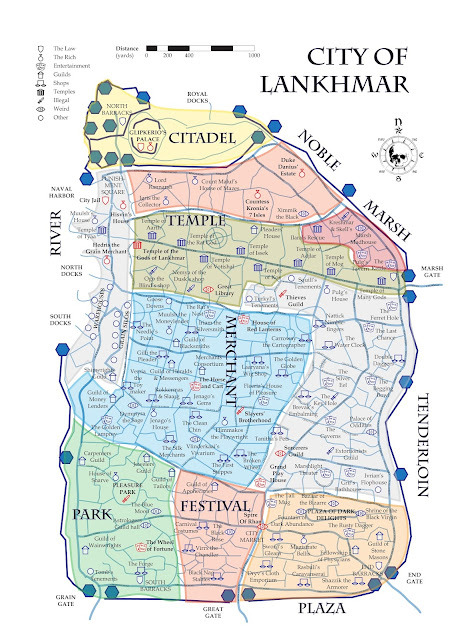

Lean Times in Lankhmar has an absolutely absurd story with set pieces out of an Abbott and Costello routine, but fantasy wise what Lean Times in Lankhmar excels in is its worldbuilding. The story provides an incredible amount of information about the culture of Lankhmar and the Street of Gods that it’s hard not to feel immersed, every nugget of information provided within a paragraph of exposition and off hand detail creating an intense image of its setting. The Street of Gods is a “theater of the proto-gods” where these temples are rented and their position on the street ranking their popularity from the unpopular gods of the Marsh Gate to the popular gods of the Citadel. There are several different versions of Issek including Issek the armless, Issek the burnt legs, Flayed Issek, and the unpopular Issek of the jug. When Fafhrd is attacked by bullies no one in the temple is panicked as extortion of temples is expected in Lankhmar. This amount of detail of Lankhmar is what creates this immersion that engrosses the reader to its world so effortlessly as its identity becomes so authentic to itself.

Not to mention that Fritz Lieber will take any opportunity to add an extra detail to the story. When Mouser attempts to stop Pulg’s interest in the temple of Issek of the Jug, he begins a rumor that the treasurer of the Temple of Aarth was attempting to flee with his funds. It is then pointed out in the next paragraph that the treasurer of this temple was actually in hot water and recently rented a sloop which gives Mouser’s rumor believability. This additional detail meant to showcase Mouser’s wit and cunning continues to build Lankhmar as a whole. Its culture of hierarchy religions and the somewhat seedy nature of those within these temples is showcased within the explanation of Mouser’s lie. For Lieber to showcase the lore of his world within such is nothing short of astonishing, and to have so much detail shown in this variety is highly engaging to a reader.

Of course some will see this excess of information as a slog, an infodump, tough to read, having a strange flow, but to most fans of High Fantasy Literature this is exactly what they look for. A level of incredible detail finely tuned to help create its story’s setpieces, and Lean Times in Lankhmar wouldn’t be the same without this worldbuilding. Without the explanation of Mouser’s truth behind his lie, it doesn’t make the reveal of Pulg seeing through Mouser’s lie as surprising. Without the explanation of hierarchy within The Street of Gods, it doesn’t show just how insane it is for Issek of the Jug to become so popular so quickly. And almost all of the worldbuilding presented to the reader builds up the climax of Fafhrd being seen as Issek of the Jug causing the masses within the temple to go insane. The details build the story, giving further insight to the reader of why characters react the way they do and why it is so important.

The worldbuilding especially is crucial as it presents how the characters affect the world around them, interacting and impacting the setting. This is what makes a story more believable and makes it feel more real, it’s how a story becomes immersive. The story would have surely been a good read if it had half the detail, but it wouldn’t be as great. This intensive worldbuilding elevates characters, motivation, stakes, dialogue, actions, set pieces, everything. Lean Times in Lankhmar is even more impressive when you take into consideration that it was the first to do many things that are now staples within High Fantasy such as the thieves guild and the dynamic of a large man who fights and is not too bright and a cunning smaller guy who gets into a lot of trouble. So not only is Fritz Lieber a master of his craft but he is undeniably a trendsetter within the history of Fantasy Literature, with worldbuilding and details of Lankhmar that can make such a fantastical place feel real when you read it. If you sit down, find a good music playlist, and really read Lean Times in Lankhmar you will be sucked into its world in true immersion.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Religion and Loyalty : Lean Times in Lankhmar

Lean Times in Lankhmar : The Values of Religion

The story begins with Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser, two famous adventurers that find themselves in a chaotic world of religion in Lankhmar. These two men used to be friends, but they now have different lives to lead, in a world where religion functions as a marketplace. The temples are dedicated to lots of deities competing for the follower's donations, and the religion when it becomes larger moves closer to the Citadel. Fafhrd joins a minor god, Issek of the Jug, and becomes a preacher alongside Bwardes. This religion is all about peace and resilience. While the Gray Moser works for what is essentially a thief's guild, under the head named Pulg, men steal and have an eye for gold. Fafhrd and the Grau Mouser’s loyalties through the story grow to the point of tension between the two (Though it is one-sided due to Fafhrd’s beliefs). Eventually there is a violent fight between the goons of the thief's guild and Fafhrd. Fafhrd prevails, and Pulg is disappointed in Mouser. Mouser then sets out to trick Fafhrd into drinking himself dumb, then the followers then think that Fafhrd is Issek of the Jug. The two friends then reunite and set off once again

In Lean Times in Lankhmar, Fritz Leiber shows how religion can be corrupt when it is more about money and power the real beliefs and values. In the chaotic city of Lankhmar religious temples are there to make a profit, and they compete for followers. As the text states, “Lankhmar itself and especially the earlier-mentioned street serves as the theater or more precisely the intellectual and artistic testing-ground of the proto-gods after their more material but no more cruel sifting at the hands of the brigands and Mingols.” Though that is the beautiful thing about Issek of the Jug, the people were poor, and the money did not matter. The values came first for what we could see for the first time in the story and maybe the history of Lankhmar. There are temples for all kinds of obscure gods, and each one tries in their own unique way to bait in people in, whether that be through offering miracles or blessings or protection. This may be just out of actual belief; but the realists see that it is a way that these temples make money and have influence. Unless there is a religion that is pure peace and where money means nothing. Furthermore, in the text we see that these temples are advertising and competing with one another rather than having a spiritual experience.

Again, religion is treated like a hot commodity here sure that could work, but when there are few intelligent conversations about the deities that were, “as numberless as the grains of sand in the Great Eastern Desert.” There was much talk about money stealing and hierarchy, but the exploration of the religion was few even though there were mentions of philosophers. Reaching, philosophers did send a message because they stopped so often to hear Fafhrd and Bwardes preach they were mesmerized by a religion that could swoon people without the glorious aspect of moving closer to the Citadel. Perhaps an idea so unfamiliar their minds were changed or amazed. This however does not matter because of the fact that even the main characters did not believe the idea that Issek was real as other people did though make a thoughtful impact on the future of what the religions of Lankhmar could look like, the author states:

‘Not I,’ he said at last. ‘There are always other tales to be woven. I served a god well, I dressed him in new clothes, and then I did a third thing. Who'd go back to being an acolyte after being so much more? You see, old friend, I really was Issek.’”

He recognizes that Issek was gone forever. However, he did something good for that religion, showing that it was possible to become great in a world full of capitalism, and life ran by money.

While the religion in Lankhmar is wondersome, and interesting to read about, there was another prevalent theme that need not to be ignored: Friendship and Loyalty. The friendship between fafhrd and the Gray Mouser is changed from their past adventures when they chose different lives in Lankhmar’s religious sea. Fafhrd follows humility, peace, and compassion, while the Gray Mouser, was hired by a mafia (Pulg) of sorts being a mercenary of people's money and lives. The division of friends creates a direct opposition. Thier relationship then seems lifeless at the time, in a way, other than Mouser setting people up to contest Fafhrd. This then shows that there is still love in the Mousers heart, there were direct orders for Mouser to go and contest Fafhrd but instead the greed took over and he took valuables from someone else instead of having the perfect tactics to tear Fafhrd down. The sneaky thought though is in the conversation between Pulg and the Mouser we see the love in Mouser's heart with the following, “’You're not still soft on him, are you, son?’ The Mouser arched his eyebrows, flared his nostrils and slowly swung his face from side to side.’” Pulg sensed it from the beginning, there is no other reason for him to be asking that question to former comrades. All of this does not matter though. In the end of the story when “Issek” appeared and ran into the darkness with Mouser, then we see them reminiscing about each other and the time that they had in Lankhmar. The ending states:

��’I have no regrets for Lankhmar,’ he said, lying mightily, though not entirely.

‘I can see now that if I'd stayed I'd have gone the way of Pulg and all such Great Men-fat, power-racked, lieutenant-plagued, smothered with false-hearted dancing girls, and finally falling into the arms of religion.’

Even though the deception, and the opposite paths, they stay the people they were before, and I assume that there were more adventures after this with the other books that were published. Would anyone be able to stay friends when they attempted to kill you, or get you so drunk you pass out? What kind of person does that take? How much loyalty do these two have?

0 notes

Text

Lankhmar and the Origins of Adventure Fantasy

Fritz Leiber’s Lean Times in Lankhmar is a sword and sorcery short story that is part of the Fafhrd and Gray Mouser series. The Series had a huge impact on the development of the Sword and Sorcery Genre and the term for the genre itself comes from Lieber. The story is set in the city of Lankhmar, a metropolis full of scheming factions and false gods. Fafhrd and Grey Mouser begin the story by arriving in the city of Lankhmar and split apart as their friendship has fallen apart over a disagreement of loot splitting. Both find new routes in the city with Gray Mouser entering the service of Pulg, a mob leader who gets money from the small religions of the city.Fafhrd became an acolyte for the church of Issek of the Jug. Mouser eventually has to rob the church Fafhrd works and the two reunite as opponents but eventually things resolve with Fafhrd attaining apotheosis, becoming a living god, and Pulg ends up serving Issek The two eventually leave with the money.

Lean Times in Lankhmar serves as a sword and sorcery template for novels such as Alyx by Joanna Russ and Michael Moorcock’s Elric Series. Most significantly, Leiber’s work was a major influence on Dungeons and Dragon, With TSR putting out adventure supplements set in Lankhmar and the world of Nehwon. This influence creates an image of fantasy that has bled into the mainstream perception of fantasy literature. Leiber writes in an immersive style, much of it sounding like descriptions of a D&D scenario, this is seen with the naming conventions of characters such as Gray Mouser, Muulsh the Moneylender. These names evoke images and associations that stick in the mind and immerse the reader as it makes the character sound as if they are a part of the world and have a reputation. The immersion is also seen in the allusion to another Fafhrd and Gray Mouser story in referencing the Year of the Feathered Death, giving a sense of continuity to the stories and sewing the plots into the fabric of the setting. This sense of immersion plays into a reminder of DnD as it reminds readers of the shared connected worlds and stories of the role playing game. It also adds immersion as it allows the reader to speculate on what the Year of the Feathered Death was if they’ve never read that tale similar to the allusion to the Clone Wars in the original Star Wars where there was nothing but the allusion until the Prequel Trilogy fleshed out the Clone Wars. Leiber’s approach to immersion is akin to throwing you into the world and letting the reader figure it out rather than using exposition to accomplish this. Depending on the reader, the show not tell approach can be an effective tool for immersing the reader but for other readers this can pull them out of the narrative. Leiber’s characters also set up archetypes that are seen within Dungeons and Dragons, Fafhrd being the large northern warrior who is honorable and brave, Gray Mouser is the sly rogue who uses wits and deception to achieve success, both of these are common character types in fantasy and within Dungeons and Dragons. The competing priests and faction also plays into this as characters like Pulg can easily be seen as quest givers. These character tropes have even bled into the characterization of characters within Dungeons and Dragons lore and novels such as the Dragonlance Chronicles series, with Fafhrd being very similar to Solamnian Knight Sturm Brightblade. Leiber’s work here can be seen as cliche but only in that it is an origin point for the development of these fantasy conventions and tropes. Leiber’s originality might be overrated now but it lays the groundwork for much of the fantasy genre and Lean Times in Lankhmar contributes much to what we owe to Leiber.

0 notes

Text

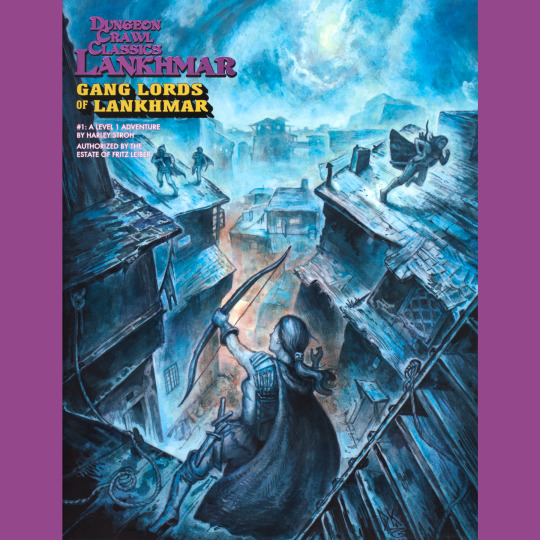

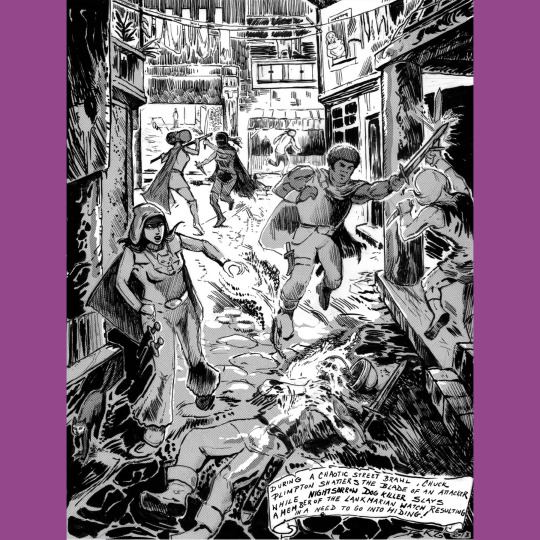

Fritz Leiber’s Lankhmar stories are so delightful because they mix fortune and folly. Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser tend to gain fortunes thanks to the folly of others, and promptly lose them again, thanks to their own. This was a difficult experience to capture in the framing of D&D’s version of the City of the Black Toga. How will Dungeon Crawl Classics fare?

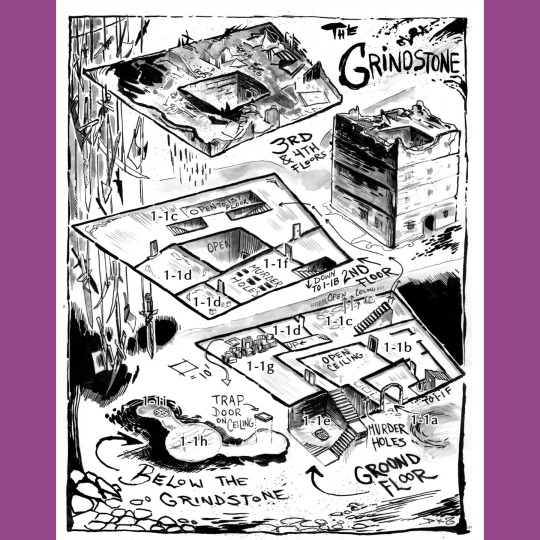

This is Gang Lords of Lankhmar (2018), the first DCC Lankhmar module (spinning out of the Lankhmar campaign setting box, which I covered way back in November of 2021). The framework is simple. One neighborhood gang — the Knife Twisters, in their fortified tenement — wants to be the ONLY neighborhood gang, and hires the PCs to help muscle out the Pimp Street Scuttlers (who lair in the sewers) and the Forty Owlets (who have a rooftop tent city). The adventure begins with the players acting at the behest of the leader of the Knives, but things soon get out of hand and that idiot gets himself killed, leaving the rest of the gang to elect the PC’s the new boss(es). A true Lankhmar success story, going from rags to somewhat nicer rags! What happens next is entirely up to the players, who might wisely decide to take what gold they can find and skedaddle to another, less pointy neighborhood.

A solid start to the adventure line, I think, with nice art throughout (Doug Kovacs on the cover, a suite of Goodman regulars inside). I particularly like the inclusion of the Neighborhood Tension mechanic, which gauges non-gang patience and introduces new potential problems from the Thieves Guild and the Watch as violence increases.

#roleplaying game#tabletop rpg#dungeons & dragons#rpg#ttrpg#d&d#Goodman Games#Dungeon Crawl Classics#Lankhmar#Gang Lords of Lankhmar

68 notes

·

View notes

Text

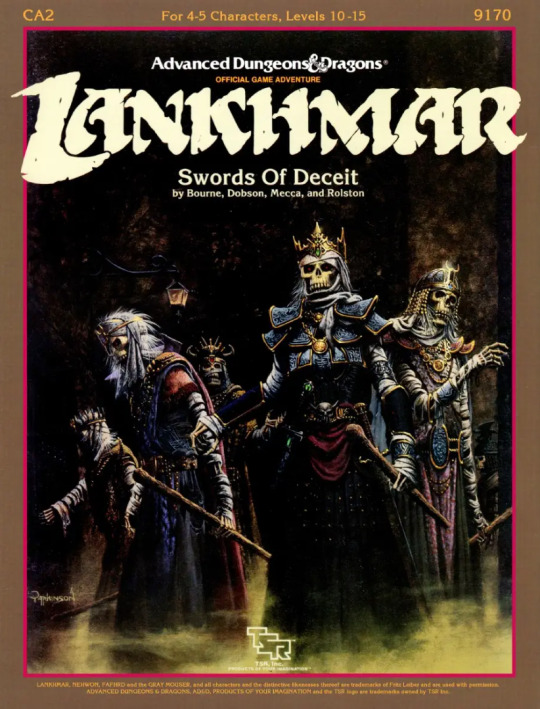

447. Stephen Bourne, Michael Dobson, Steve Mecca and Ken Rolston - CA2: Swords of Deceit (1986)

The last in the CA series of Lankhmar set adventures, this module brings together 3 adventures set in the City of Adventure, with some cameos (Fafhrd and the Grey Mouser, of course) and a stellar group of adventure creators. Ken Rolston would eventually be the lead designer for a couple of little games called Elder Scroll: Morrowind and Oblivion. Curiously the Lead Designer for Elder Scrolls: Skyrim, Bruce Nesmith, is also a TSR alum that we have mentioned before and will again. I suppose that just shows the D&D pedigree of the Elder Scrolls series.

A bunch of fun little adventures then, set in a well fleshed out world, with quite a lot of accessory material, some of which I will post here tomorrow, so stay tuned! There's a bunch of maps, including a really good full color map of Lankhmar for you to appreciate.

There weren't that many modules set in Lankhmar, although TSR would keep supporting the setting well into the 1990s, with new versions of the main campaign setting coming out for future editions of the game. Unfortunately, even with its literary pedigree as set in the world of the successful Fritz Leiber books, it would never be as popular as other D&D settings such as Greyhawk, Mystara, Dragonlance or the upcoming Forgotten Realms.

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

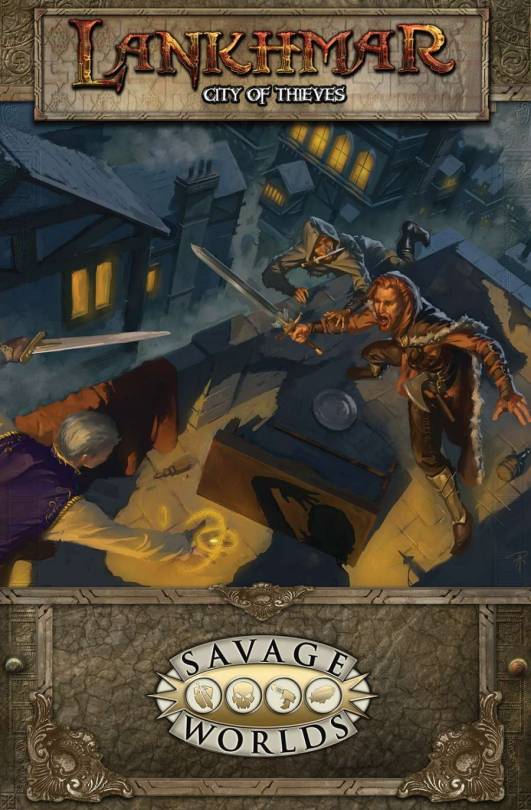

#licensedRPGs2015 Lankhmar: City of Thieves & DCC Lankmar

The first of these is the Savage Worlds adaptation of Nehwon, the Fafhrd and Gray Mouser setting. Leiber’s characters and stories are definitively one of the great influences on early D&D. While Tolkien set a template for the fantasy history, these characters and how they interact with the world and each other became a touchstone for players.

There had already been a couple of earlier adaptations of the license, beginning with several different versions from TSR. In 2007 Mongoose would release three books adapting it to Mongoose Runequest. This version comes from Pinnacle Entertainment, adapting it to the current version of Savage Worlds.

Like many of their recent, big-ticket releases, the Lankhmar series came out of a successful Kickstarter to fund the whole series. Beyond this core book, they released a map, an adventure, an archetypes book, and three more substantial sourcebooks: Savage Seas of Nehwon, Savage Takes of Nehwon, and Savage Foes of Nehwon. These would come out over the next several years, through 2018.

Strikingly in parallel Goodman Games would also have access to the license. In 2015 they released three DCC Lankmar supplements, the adventures Through Ningauble's Cave and Masks of Lankhmar as well as The Patrons of Lankhmar, which offered a preview of the upcoming DCC adaptation of the setting. That big book would arrive in 2017 and kick off a series of new modules set in that world.

1 note

·

View note