#LM 1.5.10

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

#i have many talking points to post re: todays chapter but let's start with this#come back later for sex work informed analysis of how this chapter is presented if u want#les mis#lm letters#les mis letters#fantine analysis tag#les miserables#fantine#lm 1.5.10#mine

142 notes

·

View notes

Text

I started les mis letters very motivated but here I am procrastinating now that things are going really bad for fantine. I don't wanna read those chapters. I just read the part where she cut her beautiful hair to buy clothing for her child that was given to eponine instead but fantine didn't know that and she was so happy and hopeful in her misery "my child is no longer cold. I have clothed her with my hair" god that fucking sucks

56 notes

·

View notes

Text

This marks the first chapter that ventures beyond sorrow into true (body) horror. All the ominous foreshadowing and bleak expectations have materialized. Fantine, driven by the desperate need to financially support Cosette, resorts to selling herself in pieces. What makes it even more heart-wrenching is that her hard-earned money is squandered by the Thénardiers, bringing no improvement to Cosette's life. Fortunately, Cosette seems to endure the hardships without falling ill, while Fantine's health is visibly deteriorating.

Fantine has not only lost the natural treasures she was endowed with (as hinted in the previous book) but also all the symbols of comfort in her life: first her pet bird, followed by her bed, and a small rosebush. In her impassioned reaction to her misfortunes, Fantine shares a resemblance to Jean Valjean when he harboured a profound resentment towards society. However, in Fantine's case, Valjean himself becomes the embodiment of injustice, and her hatred is directed squarely at him.

The last step towards moral degradation according to nineteenth-century standards is to sell herself. And that’s what we witness her doing.

We can see how societal demand for the use of euphemism has changed in the last hundred years, from how Hugo’s “fille publique” is translated by Hapgood as “a woman of the town,” and by Donoupher as "a common prostitute.”

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

I.v.10 Suite Du Succès

Results of the Success: Wilbour, Hapgood, Walton

Result Of Her Success: Wraxall

Continued Success of Madame Victurnien: Denny

Outcome of the Success: FMA

Continued Success: Rose

The Consequences of Her Success: Donougher

6 notes

·

View notes

Video

tumblr

Another excellent scene from Les Miserables 1967 relating to the Les Mis Letters for today, this time from episode 3. I love how 67 focuses on that Fantine becomes a prostitute through legal means, and how that automatically makes her lesser and more watched in the eyes of the law. Javert is perfectly cold here, and it’s just such a good take. I really like the foreshadowing of how he will react once she actually does get in trouble. The first half of 1967 is such a wonderful adaptation (the head screenwriter died halfway through writing it, and the later episodes are...less good due to that.)

99 notes

·

View notes

Text

Everything about this chapter is so painful.

I think there’s a bit of an implied judgment of Fantine in Hugo’s use of the term “coquetry” to describe her pride in her beauty, but it’s still devastating to watch her lose that when it’s the one thing she still had that brought her joy (not including the memory of Cosette, which is necessarily bittersweet because of their separation). In a previous chapter, it was stated that Fantine loved to brush her hair. Watching her lose that, then, isn’t sad because she’s no longer beautiful; it’s sad because she can’t do one of the few things that made her happy in a life of misery.

Of course, cutting off her hair wasn’t the first appearance-related sacrifice Fantine made for Cosette. When she left her daughter with the Thénardiers, it was mentioned that while Cosette was dressed in fine clothes, Fantine herself was dressed very simply. She had enjoyed beautiful clothing as well when she was with Tholomyès, but when she realized she couldn’t clothe both herself and her daughter, she prioritized Cosette. However, as Fantine said with her hair in this chapter, there’s a way back from that. Hair grows back; clothes can be bought again. And even though she can’t afford to put in the same attention to her appearance, she still cares. For instance, after cutting off her hair, Fantine covers her head with small caps that still make her look nice. It’s not the same as having her hair, which makes her happy through its beauty and through the relaxing ritual of brushing it, but it is a small thing that brings her comfort.

Her teeth, as she points out, are a permanent loss. She lost her hope with them. I think it’s very telling that what causes Fantine the most pain isn’t the direct suffering of poverty; it’s the loss of hope and joy. The long hours of work and her constantly shrinking salary are awful. But they’re not as bad as knowing that her lack of money is keeping her from seeing Cosette. Or that she’ll never be considered beautiful again because she’s missing her front teeth. When she was poor and could still hope to have these things again, she was able to manage to some extent; she wore her caps, she’d think about seeing Cosette someday, and she’d push herself to get through the day. Now, Fantine continues to work for Cosette’s sake, but she doesn’t do any of the small things that made her happy. Her caps are now dirty, and her linens aren’t mended either “from lack of time or from indifference.” The physical suffering of poverty (hunger, cold, etc) and its emotional consequences have blended together to push her into absolute despair.

It’s interesting how Hugo links her suffering to the prison system as well:

“She sewed seventeen hours a day; but a contractor for the work of prisons, who made the prisoners work at a discount, suddenly made prices fall, which reduced the daily earnings of working-women to nine sous.”

Fantine’s salary has always been low, but the abuse of prisoners is an excuse to drive it even lower, illustrating the interconnectedness of these systems.

58 notes

·

View notes

Text

I'm now ahead on Les Mis Letters, having decided to read all of Part One in one gulp based on what @fremedon says in this post (thematic/tone description of the rest of the book, no plot spoilers).

A few comments on 1.5 through today's email, not recapping or comprehensive, just things I noted:

Chapter 1.5.4, "Monsieur Madeleine in Mourning": I cannot begin to say how upsetting I found the long paragraph about the beauty of "being blind and being loved" (by a woman, specifically):

to know you are the center of every step she takes, of every word, of every song, to manifest your own gravitational pull every minute of the day, to feel yourself all the more powerful for your infirmity, to become in darkness, and through darkness, the star around which this angel revolves—few forms of bliss come anywhere near it!

Gah!!!!!

Chapter 1.5.5, "Dim Flashes of Lightning on the Horizon":

What a heck of a character introduction:

The Asturian peasants are convinced that in every litter of wolves there is one pup who is killed by the mother because otherwise it would grow up to devour all the other pups.

Give that male wolf puppy a human face, and you’d have Javert.

(I strongly disapprove of Hugo's conflation of beauty with virtue, so this is not about the appearance but the analogy.)

Chapter 1.5.9, "Madame Victurnien's Success": Well. There's the interiority I was wondering if we'd get for Fantine. Shame it isn't under better circumstances.

Chapter 1.5.10, "Continued Success": Hugo loves irony with these chapter titles, huh? It really works.

Rose's translation of the last line here echoes the last line of book three. Compare:

... she had given herself to this Tholomyès as to a husband, and the poor girl had a child.

With:

The poor girl made herself a whore.

It's very effective.

#les mis letters#les miserables#julie rose translation#lm 1.5.4#lm 1.5.5#lm 1.5.9#lm 1.5.10#mine-ish

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Brickclub I.5.10, “The Consequences of Her Success”

I’m not loving Donougher’s prose as music, the way I do Wilbour and much of FMA, but I’m very glad I picked up a new-to-me translation for this readthrough; I’m noticing small things I never have before. And of course in this chapter, they’re all horrible: --Talking to Marguerite about the offer for her teeth, and how terrible it would be to sell them: “I’d rather throw myself head first into the street from the fifth floor!” Which is what she’s going to do to her mirror, once she’s done it.

--Fantine keeps having to step out into the stairwell to reread the Thenardiers’ letter, because there’s not enough light in her room...the room she’s sewing in 19 hours a day. She doesn’t live long enough to suffer the consequences, but she’s in the process of sacrificing her eyes as well.

--The Thenardiers write letters “whose content upset her terribly, and the cost of the delivery was ruining her.” Imagine having to pay postage just to read their new ransom demands.

--One thing I do love about Donougher is that she footnotes when characters switch from tu to vous. She notes that starting from the furniture-dealer’s demand for payment in this chapter, Fantine is universally addressed with tu.

--Donougher translates the last line of this chapter as “The poor girl became registered as a common prostitute.” I’ve long assumed based on her interaction with Javert and general striving to play by the rules that Fantine was working legally, but the confirmation is nice to have.

We’ve been talking a lot on Discord about parallels between Fantine and Enjolras, and especially about these chapters as Fantine’s barricade. She loses, one by one, everything tying her to her life and her own future: her furniture and her little bird; her modesty and vanity; her hair and teeth. She finds a strength that was always in her--a frightening one, all cold rage and marble hardness. And her faith in a future outside of herself--embodied in Cosette--only grows.

54 notes

·

View notes

Text

Brickclub 1.5.10 ‘Results of the success’

What do you SAY about this chapter?

Things that strike me:

- Just, the way the Thenardiers work. Whatever scale they’re operating on, they want more. The current magnitude is on the order of several francs a month and the manual labor of a small child. If Fantine were a millionaire and Cosette were a capable adult, the Thenardiers would just open their mouths wider and still gobble up more than Fantine and Cosette were capable of giving them. As Thenardier says, he could eat the world. Eventually, Marius will give him enough money to get him to leave, and he’ll go use it to consume more people more entirely.

- How much Fantine comes to resemble Valjean. She has the same rage and bravado now that he did. She expresses it in laughter, and he almost never laughed, but I feel like that has to do with how much her life and livelihood as a woman depend on appearances. Valjean’s personal appearance and demeanor matters in terms of whether people trust him or will let him stay at their inn, etc., but it’s never been commodified the way Fantine’s hair and teeth and face have been since the beginning. Her laughter feels like a performance, because a sullen man may be frightening, but a sullen woman looks beaten. And neither of them is willing to look beaten.

- Until later. There’s a point in this chapter where Fantine’s care for appearances goes away.

- With Valjean’s time in the bagne, there’s a feeling that he grows more and more armor but that he could continue on that way for a long time. If the bishop hadn’t changed him, his life would be miserable and probably criminal, and he would almost certainly have been caught again and sent back to the bagne--but he would have lived. Valjean’s fall involved hardening parts of himself, but not in selling off parts of himself.

Fantine doesn’t get to keep her dignity, or the parts of her body, or the rights over who accesses her body. The world engages with Valjean in terms of what he does, be that labor or theft or good works. As long as Fantine stays in the category of “honest woman,” the world will engage with her in that capacity, but as soon as she steps outside it, she’s only a collection of commodities to be sold off piecemeal.

- The misérable status of a convict muddies that line--once he has a yellow passport, the world is very much concerned with what he is, and a prisoner is a commodity without rights whose labor can simply be taken, much like Cosette. But even then, as a man he can’t be divvied up into component parts.

- But Fantine keeps one thing that Valjean loses. She never stops adoring the kid she did it for.

- This chapter shows the similarity through Fantine competing directly with prison labor. The prisoners can be made to work for less, so she loses out. It looks like she’s competing with the prisoners when really these are just different avenues the powerful have for exploiting people. The capitalists will eat and eat and eat whatever they can get out of people.

- I’ve been experimenting lately with the idea that Thenardier is capitalism. Is this a thing? That would make the two villains of this story the police state and capitalism respectively. I think I like it.

- Like I said about Valjean’s prison wages, the feeling that Fantine’s labor is cheap and expendable and doesn’t matter is an illusion cast by the people who are profiting off it. These poor workers are the horses before the carts: they feel powerless and beaten-down, but when they fall, the entire street stops. None of them have, as of yet, learned to band together and use that power on purpose.

- I’m struck by how absolutely fucking indomitable Fantine is. You place an impossible task in front of her? She does it. Even if she has to strip off every conceivable part of herself piece by piece to do it. “Where did you get these louis d’or?” Marguerite asks in astonishment.

“I got them,” Fantine says.

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

LM 1.5.10 (retrobricking)

Oh, okay, it was the end of winter when Fantine got fired, so I guess it as actually early 1820. All right then.

That is the only Neutral Mood I've got in this chapter.

So I try to not get too into personal stuff in these , but, well. The first time I read this book, I'd been unable to find work for over a year. So, because Money Can Be Exchanged For Many Foods and Services, I , like so many people who need money, had enrolled in a medical study. Lots of poor women in that study. Lot of blood, too.

*reads about the whole Dentist event *

*stares out the window for an hour*

..I really want this book to stop being relevant.

Anyway!!

Capitalist Body Horror aside, what stands out to me in this chapter is Fantine's increasing displays of bravado. It started last chapter, but here is where it really ramps up. She gets fired and she walks by her critics with her head high; she sells her hair, and she starts singing as she walks. She laughs more in misery than we ever saw her laugh when she was happy and in love and thought she was safe. This whole process-- making more of a display of pride and confidence to counter social condemnation, reflecting disdain by Aggressively Not Caring-- is a particularly well observed bit of social behavior from Hugo. And it will come up over and over, with the gamins, with Eponine, arguably even with the barricade. It's cheer as a weapon, and especially a defensive one--but potentially an aggressive one, too.

Besides all the pain and physical violation, this is also the point where Fantine has given up all the little beautiful things she loved, including the beauty that was literally part of her own body; something this book holds as maybe even more essential than the useful, and she can't have it.

And I think this chapter is also where she's come to believe she'll never have Cosette with her again. She talks about it--but she laughs, the same way she laughs and sings to show she's not ashamed. It's a hard, brutal joke, the idea of having Cosette with her again. Now she's not working for her future; now she's just paying money to a hostage taker. Because she has to know, by now, that the Thenardiers, who constantly threaten to turn her child out, aren't being loving foster parents, can't even be trusted to be using the money for Cosette-but she doesn't see that she has a choice. She's given up on her own future, but there's still something for her to fight for.

But she’s been fighting for years now, and finally she’s lost even the weapon of her laughter. She’s down to her last stand.

#LM 1.5.10#Fantine talk#abuse ment#poverty ment#gore ment#medical stuff ment#Brickclub#retrobrick#brick club#i can never remember about the spacing

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

this has been sitting in my drafts for months and i'm finally posting it.

it's adding on from this post about Fantine and sex work in les mis. this post ended up being long and more about sex work than Fantine but it does come around i swear.

the way we discuss Fantine is very important, but why?

the way that we talk about Fantine and sex work in les mis - on tumblr, with our friends, in the brick club chat, in articles and in scholarly analysis - directly correlates with the way we treat modern day sex workers and the struggles we face today. notably, the fight for decriminalisation.

i'd argue that Fantine is the most famous of the "dead sex worker" trope. i'd argue she's one of the most famous fictional sex workers. she was just name dropped in the new mean girls movie. everyone knows the story of Fantine the "Miserable Dead Prostitute".

to many people, the book or musical is their first and often only point of reference for sex work, and informs how they treat real life sex workers. many of us interacting in fandom are or will soon be adults with jobs, you could be a childcare worker or a doctor or therapist or any role that makes you a mandatory reporter. and if you hold biases towards sex workers and your patient or the parent of the kid in your class is one, then what.

(you know i had a therapist tell me once that if i had any kids she would "be forced" to report me to the police for "child abuse" on the grounds of my job. that was discrimination and was illegal as i live in one of the four locations in the world with sex work both decriminalised and a protected attribute under discrimination law, but it still happened.)

how people think informs how they vote, and public opinion in turn impacts legislation that actively damages sex workers and puts them in real danger. (criminalisation, the nordic model, "legalisation" also known as licensing, instead of full decriminalisation).

here is a resource put together by NSWP, the Global Network of Sex Work Projects that covers terminology and legal frameworks. I recommend giving the whole thing a read, but if you just want to learn about the difference between the different legal models I'm talking about read from pages 12-14.

full decriminalisation is the safest best practice option for all sex workers. not the nordic model, not select legalisation, full decriminalisation for all workers including those who aren't "legal" citizens.

bringing this back to Fantine. when i search analysis of sex work/"prostitution" in les mis, this is the shit i find.

link 1 | link 2

i don't even know where to start on rebranding "oldest profession" to "oldest form of oppression" and "trafficked and forced into the industry" - the trafficking conflation is a common one. the majority of labour trafficking occurs in industries completely unrelated to sex work, with sex trafficking numbers being grossly overestimated. there are no true numbers because under criminalisation victim/survivors of sex trafficking can't safely seek help for fear of being criminalised. decriminalisation helps everyone.

I will also say that the trafficking narrative is a racist xenophobic one used to target migrant workers, making them more vulnerable to higher rates of police violence, detention and deportation. if you want to get deeper into this I recommend reading Migrant sex workers and trafficking - Insider research for and by migrant sex workers.

yet here we see the idea that most of (if not all) sex workers are trafficked or forced, a narrative that removes the agency of sex workers and obscures the reality of labour trafficking. in short, lies which serve to sensationalise and erase real lived experiences, provide publicly-sanctioned excuses for the heavy policing of marginalised communities, and helping no one.

i will quickly say here that you'll never meet anyone who fights as hard for sex trafficking survivors than sex workers and sex worker peer led organisations.

and in the second example, you see how even though they're saying sex work, (so they listened enough to know not to say "prostitute" anymore), but they're still sharing anti-sw beliefs like "selling the body/selling yourself", violent phrasing that denies us not only agency but connection to our bodies, autonomy, and consent.

this is something i'll talk about a lot more in the chapter analysis that i'll get around to finishing and posting one day: but fantine doesn't sell her body to sex work any more than she sells it to the textile factory. how is one form of physical labour "selling your body/yourself" and another isn't? at the end of the day, she still owns her body, just like when i leave a booking i still own my body, just like when i clocked out of my past civilian jobs i still owned my body. we sell labour, we sell services. not ourselves.

noting here that even when discussing exploitation and trafficking, phrasing it as "selling your body" is also gross, still removes the survivors agency and connection to their body, and shows that you're not really a safe ally to survivors at all.

these ideas, that i pulled from the first paragraphs of two of the first analyses of fantine i stumbled across, are the same ones that sex workers around the world argue against when lobbying for full decriminalisation. it's the arguments we have with law makers and councils and saviour organisations and our own families and friends.

i'll talk about this more later but look at how anne hathaway finished playing Fantine and then signed off on a letter and petition against full decriminalisation of sex work and advocated for the nordic model - ensuring that sex workers and trafficking victims alike would be more vulnerable to violent clients and policing.

ironically, the same thing Fantine faces.

so my whole roundabout point is it matters. the way we talk about characters like Fantine matter. this directly impacts how real people treat real sex workers. this directly impacts legislation that directly impacts the lives and safety of sex workers AND survivors of sex trafficking.

just in case i haven't said it enough the safest option for both parties is always complete and full decriminalisation btw 🫶🏻

all links in case they break (sorry for making it longer but i don't trust tumblr with links lol)

tumblr post:

NSWP terminology and legal models source:

screenshot 1:

screenshot 2:

Migrant sex workers and trafficking - Insider research for and by migrant sex workers:

anne hathaway article:

#fantine#les mis#les miserables#les mis letters#lm letters#fantine analysis tag#lm letters sw analysis#sw in les mis#lm letters 1.5#lm letters 1.5.10#mine#sorry my capitalisation is all over the place#sorry for the wall of text

52 notes

·

View notes

Text

"She had been dismissed towards the end of the winter; the summer passed, but winter came again. Short days, less work. Winter: no warmth, no light, no noonday, the evening joining on to the morning, fogs, twilight; the window is gray; it is impossible to see clearly at it. The sky is but a vent-hole. The whole day is a cavern. The sun has the air of a beggar. A frightful season! Winter changes the water of heaven and the heart of man into a stone".

The person who wrote this has gone through seasonal depression.

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

Brick Club 1.5.10 “Outcome Of The Success”

It’s long, I’m sorry. There’s just so much in this chapter!

The chapter’s first paragraph is a description of the misery of winter weather, bookended by sentences about Fantine. It’s been nearly a year since she was fired. The bit about winter is a description of Fantine’s descent as well as the weather. Winter brings short days which means less work; Fantine’s position in society means she’s finding less work as well because she is essentially freelancing rather than working for an employer with steady jobs. “No heat, no light, no noon, evening touches morning” is such a good description of the way everything is miserable and just blurs together when you’re trying to just stay alive. All the awful stuff is sharp and dull at the same time. “Winter changes into stone the water of heaven and the heart of man.” Fantine is starting to harden here; we see her become more shameless, tougher.

Fantine wears a cap after cutting her hair “so she was still pretty.” And this disappears so rapidly in this chapter. Her beauty is so important. Fantine is the only character aside from Enjolras who is repeatedly described as beautiful in a way that seems to really matter. (Cosette is also beautiful, but that description is almost entirely through Marius’ POV, rather than from a more general POV with Fantine.) The slow destruction of Fantines beauty--the discarding of her pretty clothes for peasant ones, her frequent tears, the loss of her hair and teeth, the torn and threadbare clothing--mirrors her social destruction. She desperately clings to her beauty by wearing a cap, but she obviously gives up pretty soon.

What fascinates me here is that Hugo mentions that Fantine admired Madeleine, like everyone else, but he also implies that she didn’t hate him straight away for her dismissal. In the previous chapters, her reaction is to accept the dismissal as a “just” decision. She works up her hatred by repeatedly telling herself it was his fault. It seems as though she lands on the right conclusion in the wrong way. She blames herself first, and only through gradually convincing herself does she start to blame Madeleine. He and his crap system are the ones to blame, but she comes to that conclusion in a roundabout way that feels like she still blames herself but is trying not to. Fantine has been a scapegoat for everyone up until now; Madeleine has become her scapegoat to avoid (incorrectly) blaming herself.

“If she passed the factory when the workers were at the door, she would force herself to laugh and sing.” She’s trying so hard to make them think they haven’t gotten to her, but it just makes it so much more obvious. The laughter and singing is the “wrong” reaction, and it makes everyone notice her even more, and judge her even harder. It’s just so sad because I can understand that behavior of trying so hard to act the opposite way of how you think people will expect you to, only it backfires and makes your true feelings all the more apparent, which gives even more fuel to the cruel people.

Fantine takes a lover out of spite, “a man she did not love.” There are a few things here that contrast with the grisettes of 1.3. This lover is someone Fantine does not love, her first relationship since losing Tholomyes, who she was in love with. The man is also a street musician, which reminds me of Favourite’s actor/choir boy. The difference being that Favourite’s boy had at least some connections through his father, and Fantine’s lover is only a street musician. Fantine takes this lover in for the same reason that she sings and laughs outside the factory: to try and show that she’s unaffected, which really only serves to do the opposite. She has this affair “with rage in her heart,” which seems to be the only emotion left for her for anyone besides Cosette (and maybe Marguerite).

“She worshiped Cosette.” My only comment here is that this is something that Valjean will later echo. Both worship and adore Cosette as a point of light, something to cling to and love and care for.

Okay maybe I’m missing something here, but Fantine can read but she can’t write? This is probably my “been good at reading/writing my whole life” privilege talking, but wouldn’t she be able to write if she could read? I suppose maybe it’s like how I can look at numbers and understand the numbers but I can’t do math for shit? I don’t know. That just caught my eye.

Fantine is starting to lose her inhibitions as she begins to lose control of everything in her life. She’s laughing and singing and running and jumping around outside in public, she’s acting loud and brash and odd. Her reactions to her misfortune and the terrible things that keep happening express the “wrong” emotion. It’s an attempt to cope, and a courageous one, but it’s drastically different from the quiet Fantine who barely spoke that we were introduced to.

“Two Napoleons!” grumbled a toothless old hag who stood by. “She’s the lucky one!”

This line really struck me. We’ve been tunnel-visioned on Fantine’s misery this whole time. Suddenly the focus pulls back a little bit and we get a little bit of perspective. Fantine is not at rock bottom yet. She could still go so much lower. To this toothless old woman, she’s lucky because she’s pretty and because her teeth have worth. Fantine is poor, and cold, and worried about her kid, and most of the town laugh at or scorn her, and yet this old woman still thinks she’s the lucky one of the two of them. It’s a much more subtle commentary on the levels of poverty and abjectness that exist. Once you’ve fallen through the cracks in society to the level of homelessness, to the level of selling your teeth and hair and body, to complete aloneness, anyone who has even a scrap more than you seems “lucky.” And Fantine’s not too far from that existence.

The conversation between Marguerite and Fantine about military fever is so weird. Is Marguerite just saying stuff? This dialogue sounds like a conversation between two people who have no idea what they’re talking about. It’s like those scenes in comedies where one person pretends to be super confident about something to impress the other even though both of them are completely wrong. Oh okay wait! I just did some googling and I’ve realized that neither of them know what they’re talking about because Thenardier did his bad spelling thing! “Miliary fever” is an old medical term for an infection that causes fevers and bumpy skin rashes. (Mozart’s death is attributed to it; it seems to have fallen out of use as it became easier to pinpoint certain illnesses.) I think this isn’t just Marguerite not knowing what she’s talking about. This is a misunderstanding due to Thenardier’s misspelling (whether deliberate or not, I don’t know) and neither Marguerite nor Fantine know enough to realize it.

ETA: Okay wow I’m keeping that whole “miliary fever” thought journey in just to record my thought process but I’ve just double-checked against the Hapgood translation and the original French, and the mistake isn’t with the Thenardiers at all! It’s entirely the fault of the translators. The original French says “miliare” and Hapgood has translated it as “miliary”; Fahnestock and MacAfee clearly did not notice that the French was “miliare” and not “militaire,” and neither did their editors.

“During the night Fantine had grown ten years older.” Off the top of my head, I can only think of three instances of not-old people being blatantly described as looking old. This description here, Valjean when he returns from Arras, and Eponine. There are probably more I’m missing, but the connecting factor between these three is severe, prolonged trauma. Trauma and a difficult life can prematurely age people (I always think of that Dorothea Lange photo of the migrant mother who was only 32 but looks 50) and Hugo uses this fact to bolster his descriptions of what they go through. But Fantine and Valjean both age almost suddenly; Eponine is already old-looking the first time we meet her as a character with dialogue. Fantine’s sudden aging is another level of departure from her old life. In Paris, she was the youngest of the group, and now she looks far older than she is.

“Actually, the Thenardiers had lied to get her to get the money. Cosette was not sick at all.” As readers, we know this. We’ve seen the Thenardiers lie over and over and we see Fantine sacrifice with no idea. But this one hits harder than the others. Partly, I think, because Hugo puts it so bluntly in a sentence that has its own paragraph. But also because this is the first sacrifice that is truly unalterable. Fantine’s hair can grow back. There may have eventually been some slim chance of a job opportunity or something coming up somehow, or an influx of things needing mending or something. But she cannot regain her teeth. This is also the first sacrifice that physically disfigures her in a visible way. She can hide her lack of hair under a cap, she can hide her lack of money by using and reusing things. She cannot hide her missing teeth.

It’s interesting that we do not hear about Mme Victurnien here. Rather than the last chapter, this would be the one where Victurnien would be “winning.” The consequences of Victurnien’s actions have now permanently affected Fantine’s life. Except I think the reason we don’t see her here is that she wouldn’t face it. She can look out her window at Fantine walking down the street in distress with her beauty intact and feel satisfaction, but if she saw Fantine walking down the street, toothless and hairless, I don’t think she would feel satisfaction, because she wouldn’t be able to connect her actions to this Fantine. Feeling satisfaction towards this level of misery would require acknowledging her participation in causing it. It’s one thing for the townspeople to laugh at or gawk at her, but I think claiming responsibility for her condition is something else altogether that I’m not sure Mme Victurnien would do.

Fantine throwing her mirror out the window is a strange sort of contrast compared to Eponine’s reaction to a mirror. Fantine cannot face her descent. Eponine is already there, and her excitement at Marius’ mirror is a weird sort of distracted examination of herself. Fantine cannot bear to examine herself because unlike Eponine, she can remember what it was like before this. Tossing away the mirror is tossing away the thoughts of her past life and her past self; she can’t ever go back to that.

“The poor cannot go to the far end of their rooms or to the far end of their lives, except by continually bending more and more.”

God I don’t really even know what to say about this line except ouch. It’s just so poignant and intense. The older you get the harder it is to survive, to get up with each new stumble. And we can also take into account things like the cholera epidemic that will occur a few years later in the book, which mostly affected the poor. There’s so little access to any sort of help or assistance. And clearly Valjean’s few little systems of aid aren’t good enough. He may have set up a worker’s infirmary and a place for children or old workmen, but there doesn’t seem to be assistance for single, unsupported women, or the homeless and unemployed. They’re left to bend more and more under the weight of life.

“Her little rose bush dried up in the corner, forgotten.” I can’t help but read this as a parallel to the Thenardier’s treatment of Cosette. As Fantine falls apart and falls behind on her payments, Cosette is growing up which means the abuse from the Thenardiers has probably increased. It also feels like a weird sort of throwback to the spring/summertime imagery of beauty and chasteness and modesty from back in 1.3, which has now completely disappeared and dried up as Fantine loses her beauty, her modesty, and her coquetry.

I love the little detail about Fantine’s butter bell full of water and the frozen ice marks. It’s such a small detail but so evocative. It also feels like a metaphor for each of Fantine’s new hardships. Every time the butter pot freezes over, it leaves a ring of ice for a long time; each time Fantine encounters a new trauma, she hardens and becomes tougher. She keeps her dried up, long gone modesty and youth in one corner and the suffering that has hardened her in the other. On a side note, I’m wondering if there is actually butter in her butter bell or if she’s now using it only for water? I would imagine water only; butter seems like something that might be expensive. Also, would the building she’s living in have had indoor plumbing, or would she have gotten water from a well or a pump somewhere? My plumbing history knowledge is lacking.

Hugo describes Fantine’s torn and badly mended clothes. At this point she’s working as a seamstress, which means she’s at least proficient in the skills needed to sew and/or mend clothes in such a way that they stay together. This means that the repairs done for herself are likely careless and messy. I think this is partly an indication of how little time she has for herself--if she’s sewing for work for 17 hours a day, she has very little time to mend her own stuff, and definitely can’t afford better quality material--and partly an indication of the ways in which she is falling apart. She doesn’t bother mending her things properly, she goes out in dirty clothes. She doesn’t mend her stockings, she just stuffs them further down in her shoes. It seems she has only one or perhaps no good petticoats, which means she’s probably walking around in just a shift and a dress. Not only is her stuff threadbare and falling apart, she’s also probably freezing due to the lack of layers.

“A constant pain in her shoulder near the top of her left shoulder blade.” This makes me wonder if Fantine’s left-handed. If she’s sewing by hand, by candlelight, in a shitty rush chair, for seventeen hours a day, that is absolute murder on the back/shoulders/neck. Whenever I do hand-sewing I’m usually sat on the floor or my bed, and my back and upper shoulders tend to get sore if I get in the zone and I’m bent over the work for a long time. I don’t know about French dressmakers, but I know around that time the English were really big on very small, neat, almost invisible stitches. Which would hurt to do for seventeen hours a day by candlelight.

“She hated Father Madeleine profoundly, and she never complained.” The Hapgood translation of this line is better, I think. Still, I think it’s important that it’s pointed out that she never voices her opinions or her complaints. It’s only when Madeleine is in front of her that she announces them at all (despite not speaking directly to him then, either). She hates Valjean, she blames him, and yet obviously some part of her still thinks that she deserves it, or that her dismissal was right.

“She sewed seventeen hours a day, but a contractor who was using prison labor suddenly cut the price, and this reduced the day’s wages of free-laborers to nine sous.” Reading this book is always a lot because aside from the still-relevant general overarching commentary about society and poverty and mutual aid and goodness and all that, there are so many smaller details that are so painfully, strangely relevant to the present day. Even today there’s fear that employers will come up with a new policy or a new labor shortcut that means less income. Employers who pay their employees less because the workers get tipped, or outsourcing that causes layoffs. Prison labor, too (and behind that, the fact that prison labor doesn’t guarantee a job in a similar field after release if desired).

In the next two chapters, we jump ahead somewhere between a few weeks to a couple months. What happened to Marguerite in the interim? Hugo describes her as a “pious woman [...] of genuine devotion,” but I have this sad thought that maybe when Fantine made the decision to become a sex worker, Marguerite may have turned her back on her as well. As we’ve seen with Valjean, being poor but modest is Good, and being poor and desperate enough to do something improper and “immoral” is Bad. Despite Marguerite’s canonical generosity towards the poor, I wouldn’t be surprised if Fantine’s decision overstepped some moral boundaries of hers.

“But where is there a way to earn a hundred sous a day?” I’m a little stuck on this. Would she make this much money? I’m basing the following information off of Luc Sante’s The Other Paris, so the monetary info might be slightly different a for non-Parisian area. According to Sante, someone like Fantine, a poor woman working without a pimp or madame and not in a legal brothel, would basically be working for pocket change. 100 sous would equal about 5 francs. If her earnings are basically pocket change, I don’t think she’d make 5 francs a day. Just considering the fact that a loaf of bread might cost about 15 sous, which seems like pocket change, or even slightly more than pocket change. Fantine probably becomes a sex worker and finds herself in the exact same position that she was in before, not making any more money than she would have if she had continued to be a seamstress.

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Brickclub 1.5.10 “Continued Success”

cw: Holocaust

The previous chapter ends with the association of Fantine with her golden hair shining in the morning sunlight; and this one begins immediately with the sun itself going dim and foggy and pauper-like, which is an ominous start; and then within a paragraph, the hair is gone.

There's something of a fairytale like mood to the triad of selling her hair, teeth, body a kind of "Once there was a fair maiden, with hair gold as the sun and teeth as white as ivory", somewhere between the Happy Prince, the Gift of the Magi, and The Little Match Girl; the physicality of weaving hair into a skirt, with the warmth of the sun in it. The fact that on each occasion, the barber and the dentist offer exactly the quantity she needs. I suppose part of it is also Fantine’s fairytale like attitude, a sort of glowing good nature which (in any other book) would naturally overcome adversity caused by the envious and ugly old woman.

"She had already lost all sense of shame, she now lost all vanity. A sure sign of the end." an anachronistic reference, but this reminds me of Primo Levi's description of concentration camp inmates in (iirc) the Drowned and the Saved, the way that they could tell who had collapsed inside and would not live longer, and how important it was to take what pride one could in ones appearance and daily routine to maintain a sense of who you were.

“When are you going to pay me, you tart?” like the landlord in the previous chapter, the second-hand dealer also pre-emptively expects she will end up in sex work.

I listened to a really fun conversation earlier in the month about the underlying magical system of Les Mis, and part of me is wondering - just like the Bishop buys Valjean’s soul, and one wonders just how many souls he now has bottled away, similarly how many people Madame V has fed on to keep her papery husk alive, sustained by nothing but gossip and misery.

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

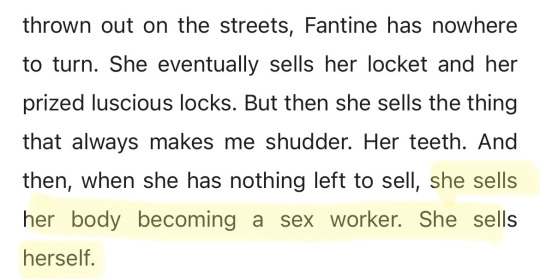

LES MIS LETTERS IN ADAPTATION - Result of the Success, LM 1.5.10 (Les Miserables 1967)

“A hundred francs,” thought Fantine. “But in what trade can one earn a hundred sous a day?”

“Come!” said she, “let us sell what is left.”

The unfortunate girl became a woman of the town.

#Les Mis#Les Miserables#Les Mis Letters#LM 1.5.10#Les Mis 1967#Les Miserables 1967#Fantine#Marguerite#Michele Dotrice#Nancie Jackson#lesmisedit#lesmiserablesedit#lesmiserables1967edit#bbcedit#tvedit#miniseriesedit#She is my favorite Fantine I think#1925 Fantine is up there#but Dotrice's Fantine HURTS me so much#pureanonedits#Les Mis Letters in Adaptation

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

Poor Marius is once again sad, even if this sadness promises to bear fruit. We return, though, to light:

“To stand between two religions, from one of which you have not as yet emerged, and another into which you have not yet entered, is intolerable; and twilight is pleasing only to bat-like souls. Marius was clear-eyed, and he required the true light. The half-lights of doubt pained him.”

From Marius’ introduction, it’s been stressed that he himself has “light.” Then, it was from his innocence as a child, but now, it’s one of righteous conviction. He still adheres to his Bonapartist beliefs, but he can’t avoid questioning them for long because he cannot tolerate “doubt;” the strength of his convictions demands that they be built upon certainty. “Clear-eyed” also implies that he sees exactly what Les Amis see and that his emotional attachment to Bonapartism is what keeps him from abandoning the ideology.

That being said, I feel a lot of sympathy for him here. Part of what he’d have to internalize to stop being a Bonapartist is that the idea of the “great man” shouldn’t be a guiding principle politically, and his thoughts surrounding that are bound up with his grief over his father. Unlearning one’s politics is hard, but processing loss is difficult, too, so doing both at once is a real challenge. Although his absence from the Musain is understandable, it also leaves him really isolated in a point of emotional and intellectual turmoil.

On top of that, Marius is poor (by his standards, at least). We don’t know how much Marius was given a month before he was kicked out of the Gillenormand household, but the 600 francs his aunt sends him are a considerable sum; Fantine made 9 sous a day, and Valjean made 15 sous with a day’s work on his way to Digne (Lm 1.5.10; LM 1.2.9). Even a workman without a criminal history would have only made 30 sous (about 45 francs per month, assuming he worked every day) (LM 1.2.9). Even Tholomyès, who was rich, only had 4000 francs a year, highlighting just how much the Gillenormands are offering him (LM 1.3.2). The workers we’ve seen were also outside of Paris, so it’s possible that the expenses of the city weigh more heavily on Marius (Tholomyès is not a good indicator of expenses, since he intentionally lived lavishly). It’s also likely that, given his family’s wealth, he doesn’t know how to save. Fantine, who was already lower class, went through that learning process after losing her job, so I can only imagine how difficult that would be for someone who’s never had to think about money. That being said, Marius is a man and a student (therefore, he has some education), so his “badly paid work” is probably a lot more than Fantine ever made.

I like how Hugo chooses to convert the 60 pistoles sent from the Gillenormands to francs here (600 of them). Since the majority of the money in this chapter is measured in francs, the conversion emphasizes the gulf between their wealth and that of a student without financial support. It demonstrates just how much Marius is rejecting as well, as all the money he gather doesn’t even add up to 100 francs, much less 600.

I also love the tiny details about spending here. It’s fascinating that rent was so, so expensive (it’s expensive today, too, but it still hurts to see in the context of Marius’ calculations), and clothes had a lot of value as well (seeing clothes as a sizeable fraction of rent is more shocking, given that they’re often a lot cheaper than rent today).

#les mis letters#lm 3.6.6#marius pontmercy#I live in terror of Marius' translations though#if I can't translate French#then there's no way he can translate English when he's just starting it#along with german#some poor French guy is reading the most strangely phrased and incoherent encyclopedia imaginable#just because Marius really needed money for food#he had to do it but he and future readers will definitely suffer

29 notes

·

View notes