#1925 Fantine is up there

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Photo

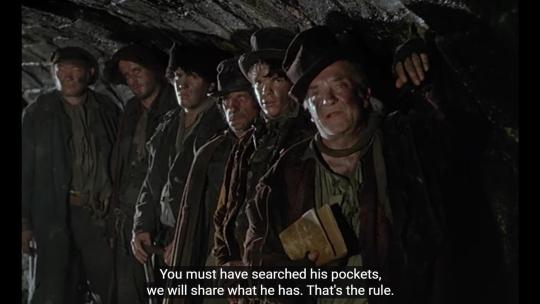

LES MIS LETTERS IN ADAPTATION - Result of the Success, LM 1.5.10 (Les Miserables 1967)

“A hundred francs,” thought Fantine. “But in what trade can one earn a hundred sous a day?”

“Come!” said she, “let us sell what is left.”

The unfortunate girl became a woman of the town.

#Les Mis#Les Miserables#Les Mis Letters#LM 1.5.10#Les Mis 1967#Les Miserables 1967#Fantine#Marguerite#Michele Dotrice#Nancie Jackson#lesmisedit#lesmiserablesedit#lesmiserables1967edit#bbcedit#tvedit#miniseriesedit#She is my favorite Fantine I think#1925 Fantine is up there#but Dotrice's Fantine HURTS me so much#pureanonedits#Les Mis Letters in Adaptation

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

BarricadesCon Panel Descriptions: Highlights of Track 1, Saturday, July 13

Reflecting on Directing Les Mis by Pieces Of Cait

Cait directed an amateur production of Les Mis at the end of last year, and would love to talk about how that went and share snippets from the show and behind the scenes. This will include talking about adapting Les Mis for the space and budget, approaches to certain scenes, dual casting lead roles, and probably raving about the lovely cast.

2. What Horizon: Tragedies, Time Loops, and the Hopefulness of Les Amis by Percy

In this presentation, Percy will discuss the ideas of tragedy and hope with reference to Hugo’s original text and the ways in which rebellion has been changed in adaptation, as well as other works of inspiration for this staged play adaptation of Hugo’s work (namely Hadestown and Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead). The presentation will detail choices made in the adaptation process, show clips from the staged reading, and touch on the different characters, setting, and overarching themes with which Percy engaged while creating the play.

3. Cosette: A Novel — The (Fanmade) Sequel to Les Misérables by Imiserabili

This presentation is a deep-dive into the 1995 fanfiction “Cosette” by Laura Kalpakian. It will include a short background on the author and the publication, a summary of the plot, an analysis of represented historical events in the work, character analyses and comparisons to the source material and other Les Mis adaptations, and memorable quotes.

4. Barricades as a Tactic: How Do They Work? by Lem

This session will explore the tactical and strategic uses of barricades, with an eye towards what to consider when writing both canon-era fanfiction and modern AUs. After all, the strategic goals towards which the barricades were used in canon-era urban warfare were often quite different from the strategic goals of similar-looking tactics in contemporary protest movements. Core components of the session will be a map-based analysis of July 1830, a comparison with June 1832 highlighting strategic goals and considerations canon-era characters would have, and an exploration of various parallels among contemporary protest tactics (which may or may not *look* like barricades).

5. Why is there a Roller Coaster in Les Mis? The Strange History of the Russian Mountains by Peyton Parker (Mellow)

In Les Miserables there is an actual canon scene where Fantine rides a roller coaster. How did a roller coaster end up in Paris in 1817? And why did this ride, one of the worlds first Roller Coasters, make a cameo in Les Mis? It’s “Les Mis Meets Defunctland.”

We’re going talk about the earliest origins of the Russian Mountains, the fascinating history behind how they came to France, their many connections to the political turmoil of the time period, what they felt like to ride, why they were shut down, how they fell into obscurity, and why Victor Hugo included them in Les Mis.

6. Obscure(-ish) Les Mis Adaptations To Watch by PureAnon

Les Mis has been adapted many times over the years, and this means there’s a lot of adaptations to enjoy. Because of this, a lot of adaptations are underviewed or underappreciated. This panel will discuss 1925, 1948, 1967, and 1995. These adaptations are all very different and are fascinating looks at how different countries and different time periods will adapt this story. Clips of each adaptation will be shown so the audience can get a taste of what each adaptation is like.

7. Recovery: A Fanfic Live Read by Eli (Thecandlesticksfromlesmis)

A full cast will live read a Les Mis fanfic written specifically for the con.

8. Preliminary Gaieties by Barri Cade, Percy, and Rare

In keeping with personal tradition, Rare, Percy, and ShitpostingFromTheBarricade will bring you a second year of our dramatic reading of the “Preliminary Gayeties” chapter of the brick, following specified drinking game rules (including classics such as “brick quotes that appear commonly in fanfiction,” “pretentious classical references,” and “drink/eat when characters drink/eat”), and enjoying snacks mentioned in the chapter as they are mentioned. Everyone is invited to participate by reading, eating, and drinking along with this activity!

#barricades con#barricadescon#les mis#les miserables#barricades#les mis con#victor hugo#lesmiscon#les mis fandom

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Les Miserables 1982: My Review

I'm going to keep this one shorter than my other reviews.

I loved this film. Only a couple of things were left out and a few things were changed slightly. All the characters we know and love are there. The acting is superb. The film is big on slo-mo dramatic effects which also makes the scenes where this is used more emotional.

While Michel Bouquet did not look like Javert (He looked more like British actor Derek Jacobi to me lol) he played the part stunningly well. He was stoic, authoritarian, though in a couple of scenes he did look a bit sympathetic (his eyes) such as when he was dealing with Fantine as she begged not to go to prison and there was a slight alteration made in the scene where he is freed from the barricade as well. I don't want to spoil it but if you watch you'll know what I'm on about. Javert's suicide. What they did with this was a very nice touch I thought. No comical, malfunctioning mannequin drops and no short falls into a placid river seine (considering that canonically Javert jumped into the rapids at the Pont Au Change.

I really loved Lino Ventura as Valjean, there was something about him, but he had that old, adorable Valjean poker face. He was not violent in this film, unlike in the 1998 film. His death scene was a bit OTT but it did make it all the more sadder and showed his grief at losing Cosette to Marius.

At the end there are a couple of changes (I think) I'm still reading The Brick and haven't got to the battles yet so I can't be sure. How come though, none of these films, ever end with Thenardier pissing off to America with Azelma (I read about that on reddit before anyone asks). Nor do any of them (certainly not the ones I've seen so far) show Madame T dying in prison.

There was not a single actor in this film that I didn't like. They were all fantastic imo. The Thenardier's got a good amount of screentime and we saw the Patron Minette in this as well. Though i was a tad disappointed in Montparnasse's attire because he's supposed to be well dressed but looks a bit scruffy.

One of my favourite things about this film is Gavroche, in almost every scene he's in he is singing a song and it's the same tune as 'Little People' from the musical but different lyrics. Once again his death was devastating and I'm not telling you anything more than that. From the adaptations I've watched so far, I don't recall any of them depicting the aftermath of Gavroche's death the way they did in this film.

The main thing that was missing was the attack on Rue Plummet part where the Patron Minette show up to rob Valjean's home and Eponine ruins their plans. Anything else that was missing I think I can forgive in this case because it's it didn't distract me too much. At least they weren't replaced with scenes where Cosette and Marius are held at knifepoint by an unhinged Javert.

Overall Les Mis 1982 is an excellent film and one I would definitely watch again. I really, really enjoyed it and I highly recommend it. It is a long film though, over 3 hours. But the 1925 version is still my No1 film adaptation of LM.

#les miserables#les mis#les mis 1982#my review#loved this film#highly recommend#lino ventura#michel bouquet#les miserables french adaptations

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

To the end of Les Mis '25 part III. Thoughts!

First, forgot to mention on part II: Valjean is robbed of two entire symbolic deaths (the Orion & the coffin heist), as per the usual. Do we have any film versions that keep the latter? I understand why it's cut, particularly for those versions that keep the tone somber throughout, but on the other hand: I want it.

I'm so fucking confused about Sandra Milovanoff playing adult Cosette? I'm even more fucking confused by the fact that Milovanoff forgot how to act. Where she was sharp as Fantine, she's vacant as Cosette. Huge miss in an otherwise solid film.

'25 takes the impoverishment and squalor of the Thénardiers in Paris and runs with it. M. Thénardier is undoubtedly a villain, but he's a pitiable one, bent-backed and raggedly-dressed; there's the faintest hint of comedy played up over his scamming, a little menace in how he treats his daughters, but the air is of the pathetic. He's changed enough I actually believe that Valjean wouldn't recognize him from their interactions eight years prior at the inn. There's physical comedy in Mme Thénardier's appearance (it's awful, derived directly from the novel, and haunts most adaptations--Hooper 2012 and BBC 2018 dodge this), but not much. Azelma and Éponine look like hell. I'm for it.

The film is still overall disinterested in politics, though when the Amis are introduced we are told that "A ces nouveaux contacts, Marius sentait s'élargir son esprit. Il comprenait que la VERITE ne réside pas uniquement dans le passé, qu'il y a de la FLAMME dans le présent et de la LUMIERE dans l'avenir." I can't recall a parallel to this in the novel nor found anything in a brief search; seems it's an overly optimistic interpretation of his character development in the Brick. Maybe the scriptwriter felt Combeferre's "to be free" had a different impact than how I read it. In any case, the film doesn't want us to think that Marius has remained a complete Napoleon simp. This might also be what's establishing his future involvement at the barricade, though I won't know 'til I watch part IV whether there's better development in this quarter.

Enjolras has a speech (no intertitles to indicate the content), after which we cut to a copy of Déclaration des droits de l'Homme et du citoyen--dated 1792, with Robespierre's name featured in large font. I get the vibe, but feel like I'm missing something. I suspect a grasp on the French political scene in 1925 would help parse what's going on here.

Paul Guidé as Enjolras looks like an aging rock band frontman. Maybe someone with finer tuned senses for Amis could pick out who's who in the crowd around him--I think we cut to Grantaire drinking with ladies at an adjacent table?--but none are explicitly named or get to occupy camera center.

Congrats to '25 for dodging the incest bullet. The dynamic between Valjean and Cosette continues to be quite sweet and mutually attentive (we're probably benefiting from the fact that the filmmakers don't have the space to include flirtatious dialogue a la '35 and '52). Milovanoff comes back to life for brief flashes when interacting with Gabrio, particularly in the scene where Cosette fawns over Valjean's injury from the Gorbeau ambush (she then knocks back out to "reflect" on Marius, or--I assume that's what her face is trying to communicate is happening).

Unfortunately Marius and Cosette's courtship timeline is condensed--if I'm not mistaken? As they walk together at night in the garden there are intercuts with shots of the fountain and trees, and I'm uncertain whether these are meant to be understood as timeskips. I think not. Cosette comes across as unsettled where I think the intent is overwhelmed, and she lacks the boldness and charm of her characterization in the book. Can't say I'm enthusiastic over any of it. Why, Milovanoff?

Suzanne Nivette as Éponine is fabulous during the defense of the Rue Plumet. She's self-destructive, she's a little mad. The altercation becomes physical and loses me for a minute, but it's solid overall. I wish Marius had done a single thing to justify her investment in him, but he's treated her throughout as if she's something distasteful (which--I in fact entirely buy this version of Marius looking at her with condescension and disgust, but I think it's supposed to break into some flavor of kindness when he and Éponine first speak in his room; François Rozet flubs the delivery--he's a little vacant--and Nivette's performance is wasted; to be fair, Nivette is utterly fucking feral during that scene, and maybe threw him).

Did Toulout lose weight between parts II and III?? His face looks less blocky. Maybe they changed his makeup as part of the aging effect? Anyway, he's fun, solid Gorbeau ambush, you can tell they really wanted to add the hat line but couldn't fit it. Pause for Javert squad, Javert absent:

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Yeah! There's a lot of good stuff in the older adaptations, particularly the French ones IMO, also there's a good Italian miniseries from the 60's that had zero budget but a lot of creativity to make up for it, and then there's a few Spanish and I think Mexican ones too? From like the 70's? I haven't actually seen those, just clips from them.

There's also the anime called Shoujo Cosette, which focuses on Cosette but it also includes a lot of stuff that often gets left out.

None of those have more Myriel as far as I remember but still, lot of other underrated scenes

Oh yeah and there's the Arai manga that's now finally getting an English translation! I think the first volume is already out, and it does have more Myriel scenes! I warmly recommend that one for other reasons too, it's a really cool and unique adaptation with a lot of fascinating imagery. One of the best examples of adapting Hugo's vivid descriptions and metaphors into a visual medium

My personal favourites are:

the aforementioned Arai manga

the 1925 film which I already mentioned earlier too; has probably the best Fantine ever and it's one of the most faithful and complete adaptations that I've seen

the 1934 film trilogy which is not always necessarily the most faithful adaptation (although I wouldn't call it unfaithful either because it still captures the essence of the story very well) but it's a classic for a good reason; absolutely worth checking out. It has great drama mixed with a sense of humour and genuine warmth

^ not to be confused with the 1935 Hollywood film which is a joke

the 60's children's show produced by the Théâtre de la Jeunesse, which is goofy as hell, but highly entertaining and sometimes surprisingly effective

and the 1972 miniseries, which is weird because it focuses almost entirely on the last three volumes of the novel (volumes 1 and 2 get summarised in like 20 minutes in a flashback in the middle of episode one) and I love it because the last three volumes are what adaptations usually abridge the most

I would love an adaptation of les mis that explores Myriel before Jean Valjean shows up actually. I thought the discussion of the guillotine and the death penalty in 1.1.4 was really interesting

72 notes

·

View notes

Text

1925 Interview with Sandra Milovanov on playing both Fantine and Cosette

Translated by me. Super interesting read, love to see her perspective on the characters she played, love that she takes out her copy of les mis and makes the interviewer read it and reading all these old articles about the 1925 adaptation really makes you think about the evolution of movies as an art form, all these dancers and actors who were becoming movie stars, and then the change that was going to come with the introduction of sound films

Source: Apollo-Journal, January 1st 1926

On the wall hung a beautiful, large blue and pink painting with a circle of white wings, representing Sandra Milowanoff in The Death of the Swan because the great artist who was speaking to me about Cosette had belonged to the Russian ballet of Serge Diaghilev. One day, without a doubt, a director will profit from her double talent for dance and expression before the camera and we will applaud this magnificent artist in the role of a dancer where she will have spun the choreography herself.

While I continue to look at the framed Death of the Swan painting, Sandra Milowanoff takes a volume of Misérables and tells me: “Re-read it yourself…look…Cosette owes it all to Jean Valjean, doesn’t she? He saves her from the Thenardiers, from the forest, from the misery of abandonment, he made for her a life of happiness, she owes him Marius and her marriage, and well, when Marius asks Jean Valjean to step aside from the young couple, she puts up with it, my God…read it…”

And I read: “Cosette did not ask questions, was not shocked, she avoided saying “father” or “Monsieur Jean.” She let herself be addressed as “vous”, she let herself be called “madame,” only her joy was somewhat diminished.”

“A diminution in joy,” interrupts Sandra, “before the sorrow of this man who raised her, who loves her, and who will soon die because of the distance that they hold him at…”

Further still, the poet adds: “She would have been sad, if sadness had been possible for her.”

“Look again at the happy child’s selfishness:

‘No longer using ‘tu,’ using ‘vous’ and ��madame’ and ‘monsieur Jean,’ all this did something else to Cosette. The care he had taken to detach himself from her had succeeded. She was more and more happy and less and less tender. One day the word “father” escaped from Cosette. A flash of happiness illuminated the old somber face of Jean Valjean. He reprimanded her: ‘Say Jean!’ ‘Oh! It’s true,’ she responded with a laugh, ‘Monsieur Jean.’ ‘That’s good, he said.’ And he turned away so that she would not see him dry his eyes.’

You see how Cosette easily observes with respect to Jean Valjean, who was so good to her in being reserved as her husband Marius requested. Cosette is a little selfish, because she is too innocent. As they say, she doesn’t know what life is, incidentally it’s because of the care of Jean Valjean. She runs after butterflies... the problems that menace all beings? Jean Valjean threw them behind her with his powerful hand. Cosette? She’s a flower without a worry, who loves Marius because he is handsome and she believes that he is good. But can she really know what goodness is? It is enough, in our eyes, to simply have the charm of young happy girls. Her mother, Fantine, is more sorrowful.”

You know, and, in a few weeks, movie-goers the world over will know that Sandra Milowanoff acted in Les Misérables in the dual role of Fantine and Cosette. Fantine, a young mother, and then Cosette, young girl. And I had come to ask the great artist, who was acclaimed during the presentation of the film, how she left the role of Fantine to enter into the role of Cosette, how she transformed himself, from one to the other…

That is how Sandra came to speak to me about Cosette. Now she evoked Fantine. It seemed that the role of Fantine holds more passion for Sandra. But you must read the phrases that I am trying to transcribe for you with her Russian accent that accompanies each word from the great artist:

“Fantine is vulgar but she has a good soul…Fantine! It’s a soul that had its light…She is all suffering…She does not fall. The more her life becomes hard, the more, in the eyes of others, she wanes, the more her soul is purified…She’s a saint. She gives it all so that she can dress her daughter, her hair, her teeth, her body…Despite her social decline, Fantine is a sun that shows itself behind the clouds.

So do you understand how I transformed from Fantine to Cosette? Because, from a moral point of view these are two totally different souls, not once does a single gesture from Cosette resemble a gesture from Fantine. They are two opposite types. Why did I play two roles? But if life developed in these two beings, these two souls so different, if the suffering, which one of them hardly saw, and which the other nothing was spared, they had to have, all the same, some of the same traits. Cosette resembles her mother; they have the same traits with two different expressions.

But yes, we can be different, believe me, each true artist can transform themselves into an angle and a devil.”

Sandra Milowanoff sees that my eyes are resting on a doll that is there, a doll with a head of porcelain, with a cracked cheek and dressed in a little Russian blouse, with red leather boots.

“That is my doll. I took it when I was able to flee from my country…the broken cheek? That was my daughter who, while playing, broke this doll. I keep it with me now.”

Fantine, Cosette, Jean Valjean, this doll, miraculously saved from revolutionary violence only to be broken by a child, all this agitated around me and I was bathed in the voice of the great Russian actress. It seems to me now that it was simply a transformation and that Sandra Milowanoff had in her enough sensibility and imagination, of sadness, of happy memories, to be, on the one hand, the distraught mother of Cosette, and also Cosette herself. The conversation rebounds: her interpretation of Fantine underlines the moral resemblance between Fantine and certain Russian heroines from the great Dostoevsky and here we are talking about Henri Fescourt.

“It’s the first time that I shot with Fescourt and as you were able to see in the realization of Misérables, he’s a great, a very great director…but yes, the artist must follow the indications of the director. There are movements that seem to us to be beautiful and correct and that are not anymore when put in front of the camera and as a proverb in my country says: ‘A pair of eyes is good but two pairs of eyes is better.’

Certainly, the inner movements, the deep feelings of a character, if you aren’t able to do that, no one in the world can make you do that.”

And we left Sandra Milwanoff, great performer of Fantine and Cosette, after she declared with fervor: “You see, what we all must do: learn, learn without ceasing, learn…to arrive at simplicity, at the greatest simplicity into which you must put as much of your soul as possible, all of your soul.”

71 notes

·

View notes

Photo

"Oriental Poppies" (1927) is reproduced from 'Georgia O’Keeffe,' published to accompany the survey currently on view @museothyssen “Flowers – explicitly recognizable – first appeared in the artist’s work in 1919 in a series of watercolors based on calla lily motifs,” Didier Ottinger writes. “O’Keeffe’s interest in flowers as subject matter was stimulated by her visit to Charles Demuth, an artist belonging to the Stieglitz circle who had been painting them since 1905. During the 1920s, they became his main subjects. Demuth’s pictures convinced O’Keeffe of the artistic validity of flowers as motifs and encouraged her to explore the best style for turning them into a highly personal subject matter. From 1925, O’Keeffe depicted flowers from a closer viewpoint, so that they filled the whole picture space. This progression to close-up was brought about by the combined influence of photography and her attention to the phenomenology of the modern city. As a firsthand witness to the artistic revolution led by a new generation of photographers (Paul Strand, Edward Weston, Ansel Adams…) under the banner of ‘Straight Photography,’ she had plenty of time to meditate on what could be learned from their approach, in which the use of blow-up acted as both a formal and an emotional intensifier. O’Keeffe aspired to this intensification to adapt her art to the phenomena of the modern city: ‘In the twenties, huge buildings sometimes seemed to be going up overnight in New York. At that time I saw a painting by Fantin-Latour, a still life with flowers I found very beautiful, but I realized that were I to paint the same flowers so small, no one would look at them because I was unknown. So I thought I’ll make them big like the huge buildings going up.’” Read more via linkinbio. IMAGE CREDIT: "Oriental Poppies," 1927, Oil on canvas. 76.7 x 102.1 cm, Collection of the Frederick R. Weisman Art Museum at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis. Museum Purchase, 1937.1 © @okeeffemuseum #georgiaokeeffe #CatherineMillet @centrepompidou @fondationbeyeler #georgiaokeeffe #orientalpoppies #southwestart #georgiaokeeffeflowers https://www.instagram.com/p/CRPJpnnMnuD/?utm_medium=tumblr

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Oh my... god! So I was just talking about the 1925 silent film and of course I did another search for it online... and someone has in fact put JUST THE VISUALS (so no music) up online. There’s also a really annoying timer thing overlaid on it? I have no idea if this is a copyright-detection thing or what? it’s a little bit headachey and I’m going to grab the files to try to work out if there is a way to at least cover it over with a black box or something. Also there are currently only 3/4 parts up. And there are no subtitles. OTOH that’s ~4.5 hours of video, and you can get a good idea of at least part of the brilliance of this adaptation even if it’s only a partial view.

Part 1/Jean Valjean: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=M-vExceKBM8

Part 2/Fantine: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SqLUJ0wrYNQ

Part 4/Les Barricades: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=K_Q3AtbmnuQ

I cannot recommend strongly enough that people check these out! If nothing else, just watch for like.. 30 seconds? from here: https://youtu.be/K_Q3AtbmnuQ?t=757

#do be careful with the timer thing like I don't know if it counts as flashing or not#the numbers are moving VERY fast#hipster les miserables

88 notes

·

View notes

Text

usse 55

Floral Patterns ~ An Essay About Flowers and Art (with a Blooming Addendum.)

Share

by Andrew Berardini

A Change of Heart installation view at Hannah Hoffman Gallery, Los Angeles, 2016. Courtesy: Hannah Hoffman Gallery, Los Angeles. Photo: Michael Underwood

“Without flowers, the reptiles, which had gotten along fine in a leafy, fruitless world, would probably still rule. Without flowers, we would not be.”

— Michael Pollan, The Botany of Desire (2001)

“Not even the category of the portrait seems to have ever attained the profound level of painterly decrepitude that still life would attain in the sinister harmlessness in the work of Matisse or Maurice de Vlaminck… the most obsolete of all still-life types.”

— Benjamin H. D. Buchloh on Gerhard Richter’s Flowers (1992)

Don’t worry, nobody’s looking. Go ahead.

Stop and smell the flowers.

Feel that sumptuous perfume blooming from those spreading petals. That’s pleasure. That’s sex. That’s the body lotion of the teenage beauty fingering your belt buckle to take your virginity (or the one you wore when you tugged that belt off your first). That’s your grandmother’s bathroom and the heart-shaped wreath at her funeral. That’s the lithe fingers and supple wrists of the florist, an emperor of blooms arranging the flowers for your mother just so.

Those petals, that scent, those colors.

Somehow flowers have become a decrepit subject, “the most obsolete of all still-life types,” to use Buchloh’s words. Despite the eminent Octoberist’s antipathy (and he is hardly alone in his disdain), flowers in art are back in bloom.

Flagrantly frivolous, wholly ephemeral, though ancient in art, the floral’s recent return as a major subject for artists marks a pivot toward those things that flowers represent: the decorative, the minor, the ephemeral and emotional, the liveliness of their bloom and the perfume of their decay, a sophisticated language of purest color and form that can be both raw nature and refined arrangement, poetic symbolism rubbing against the political mechanisms of value, history, and trade. Flowers are fragrant with subtle meanings, each different for every artist who chooses them as a subject. They are a move away from literal explications, self-righteous cynicism—and toward what, precisely? Let’s say poetry.

Bas Jan Ader, Primary Time (still), 1974. © Estate of Bas Jan Ader / Mary Sue Andersen, 2016 / Bas Jan Ader by SIAE, Rome, 2016. Courtesy: Meliksetian | Briggs, Los Angeles

Free in the wilderness, rowed in gardens, in bouquets on tables, or as a decorative aromatic around the dead, flowers offer an opportunity for a simple, sensual pleasure—both a temporary escape and a corporeal return. Their origins as a species are a bit shrouded in mystery, but most who study flowers and evolution agree that they came about in order to employ insects and animals in their reproduction (a process that surely continues with our artful interventions). They lure with beauty, eventually tricking humans into agriculture and the dream of making such fecund and lively yearnings permanent, into art.

First and foremost, flowers are the sex organs of plants. Those bright colors and elaborate bodies were meant to turn us on. Georgia O’Keeffe transformed her blossoms from still-life representation into a kind of abstraction that tongued that first truth of flowers; all of her blooms wore the faces of interdimensional pussies. Robert Mapplethorpe’s photographs of flowers look even more suggestive to me than some of his more obviously lusty snaps of men in various states of undress and erect action.

Though their flounce and curve have a pornography of color, flowers as a metaphor can be easily read as safe, sanitized stand-ins for the real musk and squelch of sex. A vase of flowers in grandma’s parlor might be less notable than a bouquet of dildos erupting out of a bucket of lube. The opposite of badass to all the tough boys playing with their power tools, flowers to them are for old ladies and sissies and girls. Macho minimalists preferred stacks of bricks and sheets of steel to prove the heft of their seriousness. Besides, the florals look too comfortably bourgeois for the shock and spectacle of self-serious avant-gardists, though Giacomo Balla’s Futurist Flowers(1918-1925) look as radical as anything else those defiant Italians cooked up.

Virginia Poundstone: Flower Mutations installation view at The Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum, Ridgefield, 2015. Courtesy: The Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum, Ridgefield. Photo: Jean Vong

Though flowers have appeared in art for thousands of years, first evidenced in funerary motifs in the earliest Egyptian dynasties, they’ve been used mostly as a sideshow, a decorative motif, a signifying prop. But around 1600, during the time of the tulip mania that rubbled the Netherlandish economy, Dutch artists began to paint blooms as the main attraction: finely wrought bouquets with delicate strokes, an idealistic botanist’s attention to perfection and detail, each variety laden with meaning, some held over from religion, some devised for newly invented varietals. This efflorescence came about with the disposable income of the bourgeoisie and the introduction of the tulip to international trading with the Ottoman Empire; in the court of Constantinople, flowers were all the rage. As an object of desire and prestige, the flower earned its worth as a central subject.

By the Victorian era, the language of flowers became wildly popular, as that repressed period needed something sexy to finger, especially for the corseted women. The frivolity of flowers was perhaps an area of knowledge the patriarchy let ladies have mastery over, but male artists weren’t ignoring the chromatic potential of blooms, either. With wet smears and hazy visions, Vincent van Gogh and Claude Monet were among the best floral daubers of their time (with a solid shout out to the drooping beauties of Henri Fantin-Latour, whose 1890 painting A Basket of Flowers made it onto New Order’s 1983 album Power, Corruption, and Lies, itself an elliptical Richter reference). Flowers to these painters were a way to explore the power and range of their medium with unfettered color. “Perhaps I owe it to flowers,” said Monet, “that I became a painter.” As art took an intellectual turn, however, flowers fell out as serious subjects and became the provenance of Sunday painters, appropriate only for the marginalized. Yet as outsiders increasingly collapse binaries, the center cannot hold and vines snake into the heart of power to bloom a variety as diverse and beautiful as the spectrum of humanity.

A Change of Heart, an exhibition organized by the curator Chris Sharp at Hannah Hoffman Gallery in Los Angeles in summer 2016, touched on dreams and contemplations I’d been having about obvious forms of beauty and their force in art as both assertion and escape. Sunsets, moonlight, waterfalls, and, of course, flowers, all easily dismissed as sentimental kitsch, seemed to be enjoying a new life, born of a self-conscious romanticism that acknowledges these subjects as perhaps decayed and misspent, but lets their beauty sweep them up anyway. Sharp stated in the press release that the work in the exhibition “embraces the floral still life in all its formal, symbolic, political and aesthetic heterogeneity… a radical and even dizzying diversity of approaches, including the queer, the decorative, the scientific, the euphemistic, the memento mori, the painterly, the deliberately amateur and minor as a position, and much more.”[1]

Willem de Rooij, Bouquet IX, 2012. Courtesy: the artist and Regen Projects, Los Angeles. Photo: Michael Underwood

From historical works by Andy Warhol, Alex Katz, Ellsworth Kelly, Jane Freilicher, Felix Gonzalez-Torres, and Bas Jan Ader to art made much more recently by Camille Henrot, Willem de Rooij, Amy Yao, Kapwani Kiwanga, and Paul Heyer, the pieces in A Change of Heart approach the floral in wholly unique ways. Rather than cordoning off the artists in Sharp’s excellent show, I’m going to weave their methods, ideas, and visions into a larger conversation, some aspects of which were quite likely on the curator’s mind, as any art gallery and its resources can only be so expansive. In London as well, the gallerist and curator Silka Rittson-Thomas has opened up a project space and storefront called TukTuk Flower Studio to host the floral visions of contemporary artists.

Of course some artists in recent history focus on the base, mass appeal of flowers, like Warhol and his iconic screenprint Flowers (1964), or Jeff Koons with his giant, bloom-encrusted Puppy(1992) and solid shimmering metal of Tulips (1995-2004). But despite the blank-faced games of pop cipher employed by Warhol and the spirited industrial-scale exuberance of Koons, I can’t help finding a whisper of contempt in both, a pandering hucksterism, giving the people what they want. This obviousness and its exploitation is of course a part of the story of our modern interactions with flowers, but it obscures a more nuanced narrative.

Capitalism has so often turned beauty as a notion into kitsch, or as Milan Kundera puts it, “a denial of shit,” and we can find this modern kitsch in the unblemished bloom on the cheeks of a Disney princess, or in “America’s most popular artist” Thomas Kinkade’s creation of an imagined past of perfect old-timey townships, a good old days that glosses over all the problems of inequality and oppression endemic to that era. Donald Trump is the kingpin of this kind of kitsch these days. The best of our feelings can be easily hijacked for political purposes, but it is a mistake to cynically dismiss those feelings simply because others would take advantage of them.

All aspects of creation are beautiful enough to need little human improvement, including flowers. As John Berger writes in The White Bird, “The notion that art is the mirror of nature is one that appeals only in periods of skepticism. Art does not imitate nature, it imitates a creation, sometimes to propose an alternative world, sometimes simply to amplify, to confirm, to make social the brief hope offered by nature.” [2] We attempt to capture the power of these moments not to improve upon them, but to fix their power, to make ephemeral hopes and desires into something more permanent. Perhaps the natural versus the human-made is one more collapsing binary, and the diversity of flowers allows for such wild variety that the simple monolithic subject of “flowers” can’t easily contain it. In using flowers as a subject, artists have gravitated from the classic still life (like Richter on the ass end of Buchloh’s anti-floral sentiment), with its entwined poetical and political meanings and their elaborate symbolic language, operating at the decorative margins, toward the center. This can be traced in the atmospheric floral patterns of Marc-Camille Chaimowicz (enjoying a fantastic resurgence of interest), the pastel squiggles of Lily van der Stokker, and the softly erotic washes of Paul Heyer. Pulling the margins into the center is also of course one of the great political projects of our time.

Felix Gonzales-Torres, “Untitled” (Alice B. Toklas’ and Gertrude Stein’s Grave, Paris), 1992. © The Felix Gonzales-Torres Foundation. Courtesy: Andrea Rosen Gallery, New York

The poetical-political intertwining in flowers has a few significant contemporary exemplars. Felix Gonzalez-Torres imbued common objects with profound poetic and political force throughout his work, and included in A Change of Heart was his photograph of the flowers on the graves of Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas. In a single snap, an almost slight touristic photograph, the artist reveals a nexus of forces around flowers: as memorial, as assertion of love with all its political and artistic forces, as vaginal (given their lesbian sexuality), and as a visual poem that matches Stein’s “A rose is a rose is a rose…,” itself of course an invocation of William Shakespeare’s “A rose by any other name would smell just as sweet.” A rose is a rose and love is love, by any other name.

With a blend of flowers, sometimes artificially constructed, and his own indexical variety of sharp critique, Christopher Williams takes a more distinctly political focus, working wholly on reclassifying a collection of flower models (fakes, to be clear) not into botanical hierarchies but into political relevance. The photographs in Angola to Vietnam* (1989) are snapped pictures of selected replicas from the Harvard Botanical Museum’s Ware Collection of Blaschka Glass Models, made between 1887 and 1936. Williams, however, focuses on flowers from countries where political disappearances were recorded in 1985, reclassifying them by country of origin rather than by the museum’s system. But although these are certainly flowers, one gets the feeling that Williams wants to undermine their bourgeois beauty and the colonial impulse that collected, modeled, and classified them.

This sharply political act finds force in Taryn Simon’s photo series Paperwork and the Will of Capital (2015) and Kapwani Kiwanga’s ongoing series Flowers for Africa (begun in 2012), with their similar focus on floral arrangements made for banquets celebrating important political moments. Simon’s pictures tend to flatten the arrangements into manipulated environments. Kiwanga presents living bouquets, with the intention that they rot over the course of the exhibition (I watched one whither in A Change of Heart) so as to describe a complex physical poetic. For Kiwanga, the flowers that stood on the tables of important moments in politics represent the colonial import of European flower arrangement: where, for what, and by whom these flowers were cultivated, but also the hope and heartbreak involved in many of the agreements they witnessed. Some represented a marked turn toward liberation, while other accords withered along with the flowers. (Both of these projects echo, for me, Danh Vo’s display of the chandeliers from the Hotel Majestic in Paris hanging over the agreement that ended the US-Vietnam War.)

Zoe Crosher, The Manifest Destiny Billboard Project in Conjuction with LAND, Fourth Billboard to Be Seen Along Route 10, Heading West… (Where Highway 86 Intersects…), 2015. Courtesy: the artist. Photo: Chris Adler

Zoe Crosher’s billboard series Shangri LA’d (2013-2015), produced in collaboration with LAND, displayed a lush array of flowers and greenery arranged by the artist and shot in a storefront in Los Angeles’s Chinatown formerly occupied by the Chinese Communist Party. As one drove across the country on the transcontinental highway, I-10, the flowers rotted further with each successive picture, until a decayed brown mass greeted the traveler as they crossed into California and on to Los Angeles. The dream of prosperity and possibility that drives a traveler westward became the hardships of the road and the realities of the place.

For the last decade, Virginia Poundstone has included in her artwork all aspects of floral cultivation. She has climbed the Himalayan mountains to find the wildest of wildflowers, and traveled to the factory farms of Colombia, tracing industrially grown blooms from growth to auction to wholesalers to flower markets and shops. Her interest grew from her day job as a floral arranger and her research into the gendered origins of that craft in the West and its resonance as a mode of art making in Japanese ikebana. She has also curated exhibitions at the Aldrich Museum that included floral works by Christo, Nancy Graves, and Bas Jan Ader (Ader’s video Primary Time [1974], of endless arrangements, is also in A Change of Heart) that have informed her deep investigations into the complex symbolism and language of flowers.

Other artists focus primarily on this language. Willem de Rooij’s Bouquet series (first begun with his late collaborator, Jeroen de Rijke, in 2002) speaks without literal language. Discussions around politics are followed by meditations on color or a collection of blooms gathered for their intensely allergenic qualities. The giant displays, in contrast to Kiwanga’s, are carefully maintained throughout an exhibition; a florist collaborator always makes regular visits to an exhibition to maintain the scent, color, and freshness of the expression.

In A Change of Heart, Sharp also included Camille Henrot’s ikebana interpretations of important modern novels as well as Maria Loboda’s A Guide to Insults and Misanthropy (2006), which attempts to use the symbolic language of flowers to insult their receiver.

Camille Henrot, The Golden Notebook, Doris Lessing, 2014. Courtesy: the artist and Metro Pictures, New York

For flowers, the recent turn holds an echo of romanticism, the intuitive, the emotional, the poetic, existing alongside a belief in political freedoms. The lusty poet Lord Byron died in the war for Greek independence. One of the fundamental human rights is a right to pleasure, to beauty. Beauty isn’t our collective ignoring of the hard struggles of the world, but rather an assertion of exactly what we’re fighting for.

As Fernando Pessoa writes in The Book of Disquiet (1984), “Flowers, if described with phrases that define them in the air of the imagination, will have colours with a durability not found in cellular life. What moves lives. What is said endures.”[3]

[1] http://hannahhoffmangallery.com/media/files/pr_acoh_web.pdf. [2] John Berger, The White Bird (London: Chatto & Windus, 1985) [3] Fernando Pessoa, The Book of Disquiet (London: Serpent’s Tale, 1991)

~ BLOOMING ADDENDUM ~

Christopher Williams, Angola, 1989, Blaschka Model 439, 1894, Genus no. 5091, Family, Sterculiaceae Cola acuminate (Beauv.) Schott and Endl., Cola Nut, Goora Nut, 1989, from the series Angola to Vietnam*, 1989. Courtesy: the artist and Galerie Gisela Capitain, Cologne

Orchid / #DA70D6

General Sternwood: The orchids are an excuse for the heat. You like orchids? Marlowe: Not particularly. General Sternwood: Nasty things. That flesh is too much like the flesh of men. Their perfume has a rotten sweetness of corruption… — The Big Sleep (1946)

The shape of this flowering plant’s pendulous doubled root ball suggested to some ancient Hellenic botanist the particular danglers in a man’s kit, and the orchid got its name from the Greek word for testes. Thus the dainty beloveds of aristocratic gardeners and fussy flower breeders are buried balls, dirty nuts. Try not to snicker when granny effuses, “I simply adore orchids.” Flowers have always been symbolic of sexuality, and even more so for those for whom it’s suppressed. Women, especially older ones, have been forced by social norms to stanch their desires, rarely granted the allowance to fuck freely. It gladdens the heart in its own weird way to hear old folks homes have the highest rates of STDs these days. Not because it’s good for anyone to catch the clap, but because it means they fuck with more abandon than most might care to admit.

To some, orchids are the sexiest of flowers. Their namesake roots lie buried in most variants, while those strange blooms pump horticultural hearts with lively colors, generous curves, and lusty orifices. If vaginal decoration took a sharp surgical turn past bejeweled vajazzling, you might find yourself confronted with one of these psychedelic pussies when dipping down for a French lick. As flowers, they fall into an uncanny valley. Too close but not close enough, the effect is just creepy rather than alluring. While other flowers invite an inserted nose, a huff, and though not yet an erection, their floral perfume has turned my head in that general direction. But the fleshy orchid does not inspire my lusts even a little. Perhaps even the opposite—its odor and form the absence of body, a dry, funereal thing.

“Crypt orchid” is the term for an undescended testicle, though I dream a flower that can only blossom in tombs.

The bright, rich purple creeps its name from the flower, one of innumerable possibilities for a plant with wild variation. Though it has the crackle of electricity beneath its buzz, orchid’s too muted to be much beyond a suggestion. Bright but not the brightest, rich without being creamy, orchid’s a faded purple haze on a bright day, the fading neon of a strip club past its prime.

Rose / #FF007F

A rose is a rose is a rose is a rose.

When a beautiful rose dies beauty does not die because it is not really in the rose. — Agnes Martin (1989)

Each five-petal-kiss of colors from the tangled, toothy green stems. A brokenhearted smear, a yearning expressed through the formality of its presentation, the rose’s simple obviousness is its charm. The color of nipple, just exposed before cold air and hot mouths harden it into a deeper shade.

In many languages, the words for “rose” and “pink” are the same.

Rose-colored glasses. Roseate glow.

Rose tints my world Keeps me safe from my trouble and pain. — The Rocky Horror Picture Show (1975)

Ask any florist and he’ll know how much a dozen will cost, one extra thrown in for luck. The rose grows thorns to better climb over its neighbors, to push over other flowers hungry for a beam of sunlight. More than one rose has drawn my blood, the dripping finger quickly mouthed.

Rose, floating in the pond, a dead flower in the eddies of the silver surface spangled with light. A lover’s bathtub blanket, a romantic’s bedspread. Rose, a gesture, an empty signifier, a lover’s lament, a husband’s apology. A shapely scented flower, a dream of what pussies could be.

Flowers and fruits are the sex organs of plants. Georgia O’Keeffe knew surely what she was doing with her folded blooms, plumped petals peeled back. Victorian ladies corseted by rigid morality spent repressed hours devotedly fingering their carefully cultivated flowers. Fresh blossoms will wilt on the vine whether they are nabbed or not. Gather ye rosebuds while ye may, you virgins who make much of time. The scientific term for wilted plants starved of nutrients and water is “flaccid.”

A lover once told me she only enjoyed flowers knowing that something was dying expressly for her pleasure. Every rose has its thorn…

Flowers began as a funeral tradition to mask the odor of a decaying corpse. Wreathed, bouqueted, and sprayed, apple blossoms and heliotropes, chrysanthemums and camellias, hyacinths and delphiniums, snapdragons and, of course, roses. Anything goes for funeral flowers, just as long as they are fresh.

One artist I know dreamed of casting in concrete the cast-off flowers at the base of a Soviet war memorial. All the original flowers she stared at for hours, snapping picture after picture, measuring and admiring the perfect war memorial, the waste of pageantry all heaped and rotting, all the showy pomp to be swept up and trashed. Failing to gather them all from a park one Sunday afternoon, she made a memorial to that one. Under marbles carved Pro Patria, sometimes you’ll find flowers, but you’ll be sure to find a corpse.

“Roses,” she thought sardonically, “All trash, m’dear.” — Virginia Woolf, Mrs. Dalloway (1925)

As bright blooms fade, what is the color of decay?

Is it a sinking brown, a pale green, a moldy black that captures the wilted flower, the rotten fruit, the decomposing body? Spotted and mottled, both wet and dusty, alive with death’s critters and aromatic with rot, the color is unsteady at best, a hue with a checkered future. Tuck a rose away, let it dry, and though the life goes and the color fades, its form remains.

Ah Little Rose—how easy For such as thee to die! — Emily Dickinson (1858)

I won’t forget to put roses on your grave.

Lilac / #CBA2CB

I lost myself on a cool damp night Gave myself in that misty light Was hypnotized by a strange delight Under a lilac tree I made wine from the lilac tree Put my heart in its recipe It makes me see what I want to see and be what I want to be When I think more than I want to think Do things I never should do I drink much more than I ought to drink Because it brings me back you… Lilac wine is sweet and heady, like my love Lilac wine, I feel unsteady, like my love

Pale purples are the fucking saddest. Lavender’s forgetful wash. Mauve’s lonely decadence. And lilac. The color of unwilling resignation to lost passion. The pale fade, a lost spring.

April is the cruellest month, breeding Lilacs out of the dead land, mixing Memory and desire, stirring Dull roots with spring rain. —T. S. Eliot, The Waste Land (1922)

The lilac flower originated on the Croatian coast whence it found its way into the gardens of Turkish emperors and from there to Europe in the 16th century, not reaching the Americas until the 17th. The scent of lilac has become for many the scent of spring. Carried by the compound indole, which is also found in shit, lilac’s aroma carries with its fade a special decay, heavy and narcotic. To a nose that does not know the tricks of the master perfumer, indole dropped in chocolate and coffee makes a product smell natural.

A note found in perfume, bottled spring, often worn by elderly ladies. In the Descanso Gardens near Los Angeles, there is a grove of two hundred fifty varieties of lilac, their names a horticulturist’s poetry of yearning: Dark Night and Sylvan Beauty, Snow Shower and Spring Parade, Maiden’s Blush and Vesper Song.

I missed their bloom this year, gone to the snowy mountains where the flowers blossom late, but to walk among the towering shrubs is to be punched in the face with perfume. So sweet, so heady. Running my fingers over its heart-shaped leaf, failing to feel my leaf-shaped heart. I dreamed of going to the gardens with my lover and went there many times after she left me. Dreaming of her. Feeling the sweet sadness of her perfume, the unwilling resignation of her love withdrawn. And this lover, all the lovers who always go away. One lilac may hide another and then a lot of lilacs… — Kenneth Koch (1994)

Walt Whitman dropped a sprig on the passing coffin of a murdered president and birthed a poem for dooryards and students. Not his most beautiful by far, but its love is real. As any love for a distant leader can only be so real, but the lilac is love. Staring into a screen full of its color, I am both spring and its destruction. Its bright lovely burst of life, its wilt and loss. The cool kiss of night, naked skin shivers but still you stay. And you stay and drink its sweetness and its rot, you drink your heart.

In the desert I saw a creature, naked, bestial, Who, squatting upon the ground, Held his heart in his hands, And ate of it. I said, “Is it good, friend?” “It is bitter—bitter,” he answered; “But I like it Because it is bitter, And because it is my heart.” — Stephen Crane (1895)

Cherry Blossom / #FFB7C5

A Selection of the Traditional Colors of Japan; or, Bands I Wished I Was In

Cherry Blossom Ibis Wing Long Spring Dawn Orangutan Persimmon Juice Cypress Bark Meat Sparrow Brown Decaying Leaves Pale Incense The Brown of Flattery The Color of an Undried Wall Golden Fallen Leaves Simmered Seaweed Contemplation in a Tea Garden Pale Fallen Leaves Underside of Willow Leaves Sooty Willow Bamboo Thousand-Year-Old Green Insect Screen Rusty Storeroom Velvet Harbor Rat Iron Storage Mousy Wisteria Thin Color Fake Purple Vanishing Red Mouse Half Color Inside of a Bottle

Andrew Berardini is an American writer known for his work as a visual art critic and curator in Los Angeles. He has published articles and essays in publications such as Mousse, Artforum, ArtReview, Art-Agenda.

Originally published on Mousse 55 (October–November 2016)

0 notes

Text

French Symbolist artist Odilon Redon wrote in his journal in 1903; “I love nature in all her forms … the humble flower, tree, ground and rocks, up to the majestic peaks of mountains … I also shiver deeply at the mystery of solitude.”

A painter, lithographer, and etcher of considerable poetic sensitivity and imagination, his work developed along two divergent lines. Initially his (mostly monochrome) prints explored haunted, often macabre, themes of fantasy. However, in about 1890 he turned to painting vibrant dreamscapes in colour.

Odilon Redon, The Smiling Spider, 1881

Odilon Redon, Ophelia among the Flowers, c 1905 08

Redon’s interest was in the portrayal of imagination rather than visual perception, and like a number of Symbolists, he suffered from periodic depression. Redon’s work represented an exploration of his internal feelings and psyche. He himself wanted to “place the visible at the service of the invisible” so, although his work seems filled with strange beings and grotesque dichotomies, his aim was to pictorially represent the ghosts of his own mind.

Although a contemporary of the Impressionists, he felt that Impressionism lacked the ambiguity which he sought in his work – his artistic roots were more in Romanticism, and, like many others, he was also influenced by Puvis de Chavannes and Delacroix.

Odilon Redon spent much of his childhood at Peyrelebade (in Bordeaux) in France, which became a source of inspiration for his art. In 1863 he befriended artist Rodolphe Bresdin, who later taught him etching. Redon was so influenced by Bresdin that he didn’t use colour in his work for some time and instead worked in black and white. He stated, “black is the essential colour of all things,” and “colour is too capable of conveying emotion.”

After the 1870 Franco Prussian war, Redon settled in Paris where he learnt lithography from Henri Fantin-Latour and discovered that the unique qualities of this technique enabled him to achieve infinite gradations of tone, fine-line drawing, and rich depictions of light and dark. He was profoundly concerned with the effects of light.

Odilon Redon, Homage to Goya, 1885

Odilon Redon, Woman with Outstretched Arm c 1868

Odilon Redon, The Head of Saint John the Baptist, c 1868

Odilon Redon, The Eye like a Strange Balloon Mounts toward Infinity, 1882

Odilon Redon, Parsifal, 1891

Odilon Redon, Felinerie, 1879

Odilon Redon, Brunnhilde, 1894

Redon drew on varied sources, from Francisco Goya, Edgar Allen Poe, and Shakespeare to Darwinian theory, for his mysterious, disturbing, and often melancholy Noirs lithography, etchings, and drawings. He produced nearly 200 prints, beginning in 1879 with the lithographs collectively titled The Dream. He completed another portfolio in 1882 which was dedicated to Edgar Allan Poe. Rather than illustrating Poe, Redon’s lithographs are poems in visual terms, themselves evoking the poet’s world of private torment. There is also a link to Goya in Redon’s imagery of winged demons and menacing shapes, and one of his series was the Homage to Goya, 1885.

In 1884 Redon took part in the Salon des Indépendants, of which he was one of the founders, and in the Salon of the XX in Brussels (in 1886, 1887 and 1890) and in the final Impressionist exhibition in 1886.

After 1890 he began working seriously in colour in both oils and pastels, demonstrating his strong sense of harmony – this changed the nature of his work from the macabre and sombre to the joyous and exquisite. He introduced sensitive floral studies, and faces that appear to be dreaming or lost in reverie, and developed a unique palette of powdery and brilliant hues.

Odilon Redon, Pandora, c1914

Odilon Redon, Mystery, 1910

Odilon Redon, The Child, 1894

Odilon Redon, Flower Clouds, 1903

Odilon Redon, Butterflies, c1910

Odilon Redon, Trees on a Yellow Background, 1901

He began to work on large surfaces in 1900-1901, completing around fifteen panels for the château of Baron Robert de Domecy. On that occasion, he wrote to his friend Albert Bonger “I am covering the walls of a dining room with flowers, flowers of dreams, fauna of the imagination; all in large panels, treated with a bit of everything, distemper, “aoline”, oil, even with pastel which is giving good results at the moment, a giant pastel.”

The library at Fontfroide would be Redon’s great decorative work, which he completed in 1911.

Odilon Redon, Night, Library of Fontfroide Abbey, 1910-12

Odilon Redon, Day, Library of Fontfroide Abbey, 1910-12

He also designed sets for Debussy’s Ballet, Afternoon of a Faun, which premiered in 1912.

Odilon Redon, design for Debussy’s theatre set, 1912

Redon’s evocative images attracted the praise of many Symbolist writers and admiration from painters as various as Gauguin, Emile Bernard, and Matisse. He was an important influence on a younger generation of artists such as the Nabis, a group of post-impressionist painters whose style incorporated decorative and symbolist elements.

My gallery, Kiama Art Gallery, has a selection of Heliogravures by Odilon Redon, which were produced in 1925, which you may enjoy.

This blog is just a short excerpt from my art history e-course, Introduction to Modern European Art which is designed for adult learners and students of art history.

This interactive program covers the period from Romanticism right through to Abstract Art, with sections on the Bauhaus and School of Paris, key Paris exhibitions, both favourite and less well known artists and their work, and information about colour theory and key art terms. Lots of interesting stories, videos and opportunities to undertake exercises throughout the program.

If you’d like to see some of the Australian artwork you’ll find in my gallery, scroll down to the bottom of the page. You’ll also find many French works on paper and beautiful fashion plates from the early 1900s by visiting the gallery.

Symbolism – Odilon Redon; Night and Day French Symbolist artist Odilon Redon wrote in his journal in 1903; "I love nature in all her forms ...

0 notes

Text

Les Miserables 1978: My Review

I want to stress this before I go any further. I enjoyed watching this film but not as much as I enjoyed the 1925 epic.

The Good Stuff

It was a good watch and if i hadn't known the story, seen the musical, or watched other versions of the film then I woudl possibly have enjoyed it more than I did. Good acting, great costumes, and it was lovely to see some well known legends and actors who were familiar to me from programmes I watched in my childhood.

At first I wasn't sure about Richard Jordan as Valjean but he grew on me as the film progressed. Now when I see watch Les Mis and see Valjean doing something awesome I want to be wowed by it and at times it was possible to predict what was going to happen. Like when he saved that dude who fell down the side of the walls outside the prison and was left dangling there. I knew he was going to use that opportunity to escape. I just didn't realise that he would be successful in that escape because that's not what I remember in the book. He was a little bit of a wet blanket for me.

Anthony Perkins acted the part well though I did side eye a few scenes where he seemed a bit too much of a wet blanket. After seeing Philip Quast perform The Confrontation with Colm Wilkinson, I prefer Javert expressing a bit more anger and disgust when talking about being born in prison and so on. Overall he played the part well I'm just not sure that he was well suited to the role physically. He was too slim and as previously stated he has brown eyes (my boy Javert had blue eyes), his sideburns weren't bushy enough for my liking and I know I'm being a petty bitch but Javert's sideburns are important imo. He didn't look imposing enough however the were times when Perkins totally pulled off the stance and attitude of Javert for instance standing still with arms folded (like Napoleon) and the suspiscious gaze. He wasn't quite as authoritarian as I would have liked him to be. It's a shame because Perkins was such an awesome actor. He could have really pushed things a bit further. But he didn't. As for the suicide scene, NO COMMENT except for, where in the fuck did they buy that mannequin from and couldn't they have thrown it from a higher point. It looked like a mannequin falling into the paddling pool at the local swimming baths, if you know what I mean.

Missing Characters

Yep I've got a massive bee in my bonnet about this, no Eponine, No Patron Minette, No Enjolras, WTF??

Re-writing The Canon Story.

I'm going to keep this short. The were chunks of the story missing, things that happen in the book that imo are important to the story as a whole. Also some things they kept from the canon story but changed somewhat. Like Marius and Cosettes relationship development (the stalking) and how Javert meets up with Valjean after he rescues Marius. Thenardier not being in the sewers when Valjean was carrying Marius through them. Valjean's death, half of Fantine's story was missing. Parts of the canon story that normally choke me up and make me weepy, didn't.

My Final Verdict

I enjoyed watching it. Imo it's ideal for Sunday afternoon viewing when you want to watch something you don't need to think much about because you're still hung over from Saturday night wine time and your brain isn't working. I didn't love it, but. I didn't hate it. I might watch it again in the future but I don't know. I got screenshots and will post them soon. I'm glad I watched it. But it's not a version of Les Mis I can watch over and over (like I do with The TAC). The 1925 epic is still the top film for me at this point.

I'll watch another Les Mis movie very soon. Poll coming up shortly to halp me choose which one.

Special mention for the late, great Sit John Gielgud. No particular reason for this other than him being an absolute legend and wonderful actor.

#les miserables#les mis#les mis 1978#anthony perkins#richard jordan#my review#my verdict#didn't love it but didn't hate it either#still prefer les mis 1925#the late great sir john gielgud - special mention

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

LES MIS LETTERS IN ADAPTATION - M. Bamatabois's Inactivity, LM 1.5.12 (Les Miserables 1925)

Each time that the woman passed in front of him, he bestowed on her, together with a puff from his cigar, some apostrophe which he considered witty and mirthful, such as, “How ugly you are!—Will you get out of my sight?—You have no teeth!” etc., etc. This gentleman was known as M. Bamatabois. The woman, a melancholy, decorated spectre which went and came through the snow, made him no reply, did not even glance at him, and nevertheless continued her promenade in silence, and with a sombre regularity, which brought her every five minutes within reach of this sarcasm, like the condemned soldier who returns under the rods. The small effect which he produced no doubt piqued the lounger; and taking advantage of a moment when her back was turned, he crept up behind her with the gait of a wolf, and stifling his laugh, bent down, picked up a handful of snow from the pavement, and thrust it abruptly into her back, between her bare shoulders. The woman uttered a roar, whirled round, gave a leap like a panther, and hurled herself upon the man, burying her nails in his face, with the most frightful words which could fall from the guard-room into the gutter. These insults, poured forth in a voice roughened by brandy, did, indeed, proceed in hideous wise from a mouth which lacked its two front teeth. It was Fantine.

#Les Mis#Les Mis Letters#Les Miserables#Les Mis 1925#Les Miserables 1925#Fantine#Bamatabois#Sandra Milovanoff#lesmisedit#lesmiserablesedit#lesmiserables1925edit#silentfilmedit#filmedit#pureanonedits#Les Mis Letters in Adaptation#violence tw#LM 1.5.12#GET HIM FANTINE

122 notes

·

View notes

Photo

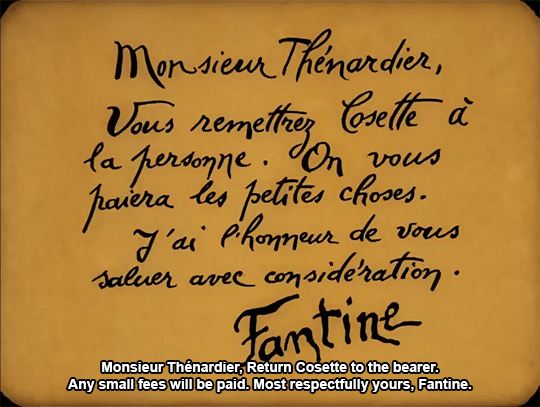

LES MIS LETTERS IN ADAPTATION - He Who Seeks to Better Himself May Render His Situation Worse, LM 2.3.10 (Les Miserables 1925)

“Pardon, excuse me, sir,” he said, quite breathless, “but here are your fifteen hundred francs.”

So saying, he handed the stranger the three bank-bills.

The man raised his eyes.

“What is the meaning of this?”

Thénardier replied respectfully:—

“It means, sir, that I shall take back Cosette.”

Cosette shuddered, and pressed close to the old man.

He replied, gazing to the very bottom of Thénardier’s eyes the while, and enunciating every syllable distinctly:—

“You are go-ing to take back Co-sette?”

“Yes, sir, I am. I will tell you; I have considered the matter. In fact, I have not the right to give her to you. I am an honest man, you see; this child does not belong to me; she belongs to her mother. It was her mother who confided her to me; I can only resign her to her mother. You will say to me, ‘But her mother is dead.’ Good; in that case I can only give the child up to the person who shall bring me a writing, signed by her mother, to the effect that I am to hand the child over to the person therein mentioned; that is clear.”

The man, without making any reply, fumbled in his pocket, and Thénardier beheld the pocket-book of bank-bills make its appearance once more.

The tavern-keeper shivered with joy.

“Good!” thought he; “let us hold firm; he is going to bribe me!”

Before opening the pocket-book, the traveller cast a glance about him: the spot was absolutely deserted; there was not a soul either in the woods or in the valley. The man opened his pocket-book once more and drew from it, not the handful of bills which Thénardier expected, but a simple little paper, which he unfolded and presented fully open to the inn-keeper, saying:—

“You are right; read!”

Thénardier took the paper and read:—

“M. SUR M., March 25, 1823.

“MONSIEUR THÉNARDIER:—

You will deliver Cosette to this person. You will be paid for all the little things. I have the honor to salute you with respect,

FANTINE.”

“You know that signature?” resumed the man.

It certainly was Fantine’s signature; Thénardier recognized it.

#Les Mis#Les Mis Letters#lm 2.3.10#Les Miserables#Les Mis Letters in Adaptation#Les Mis 1925#Les Miserables 1925#Jean Valjean#Thenardier#Cosette#Cosette Fauchelevent#Gabriel Gabrio#Andrée Rolane#Georges Saillard#silent film#filmedit#silentfilmedit#lesmisedit#lesmiserablesedit#long post#lesmiserables1925edit#pureanonedits

54 notes

·

View notes

Text

I've watched through the end of Les Mis 1925 part II, and must say--I'm digging this version, actually? I don't know whether someone uninvested in the source material would be as engaged, but I'm here for it. Some thoughts:

I.VII.III is a bitch of a chapter to adapt to the screen and '25 pt. II gets off to a weak start with its attempt to do so. It doesn't capture the vacillation, the debate. Since this adaptation is so long I would expect this scene to have more room to breathe than it's given. The ghost of Bishop Myriel does show up to give Jean Valjean a fondly chiding look though so that's chill.

Thought for a minute we were getting a dream sequence as in I.VII.IV but no. cockteased.

Does the ghost of Fantine '78 haunt every deathbed scene for anyone else? She haunts me. Milovanoff is comparatively understated.

I'm completely won over by the dynamic between this Valjean and little Cosette. '25 retains the lost/"found" coin (over which the two share a delightful conspiratorial look) and the louis d'or as well as the absurdly extravagant gesture of Catherine, and it's a good call. They keep very close to the novel through this sequence--down to Valjean putting Catherine's hand into Cosette's when he is urging her to take the doll (I'm normally unsentimental about child characters but found this sweet).

No, really, I'm unsentimental, but later on Valjean brushes off Cosette's stockinged feet before putting her shoes on, and such a little thing does so much to communicate his love for her.

The Gorbeau house is a goddamn mess, Valjean loses a point for housing a child there.

Given this is the only time Javert's presence in Valjean's life isn't purely coincidental, it's unfortunate that '25 fails to explain his appearance at the Gorbeau house (it attempts! it does not succeed).

Pause to appreciate the Javert squad.

Once in a while an adaptation makes a change that I'd guess is due to the creative team looking at the novel and saying, "No, that's too fucking sad." I suspect that is why Fantine and Cosette get reunions in '35 and '52, for example. In '25? Cosette gets to keep Catherine.

Calling all convent husband 'shippers: Valjean reciprocates Fauchelevant's affections in this one.

Tomorrow: Cosette grows up, and God willing there's no incestuous energy.

12 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Review of Henri Fescourt’s 1925 film adaptation of Les Misérables, published in Le Petit Parisien and translated by me.

It’s sort of a long one but there are a couple of fun things here. One, the reviewer really likes the film. In the last review I translated, the reviewer called it one of the great works of French cinematography. I liked that he compared it to Charles Hugo’s stage adaptation and notes the difficulty of adapting the novel. Also sort of interesting that the reviewer digresses to talk about Myriel and his inspiration and is kind of snarky about it. I have never heard that the preliminary name of Hugo’s work was Manuscript of a Bishop but it would kind of explain a lot if true. Finally, I like the line “M. Toulout gave all his picturesqueness to the face of Javert” because it’s true.

We must return to the important cinematographic manifestation that is the screen adaptation of Misérables. There has been a considerable effort and it is a happy one. M. Henri Fescourt has translated Victor Hugo’s tremendous novel into singularly expressive images; he has reconstructed the atmosphere, he has made the most intelligent artistic translation, and by very simple means. Besides, with its diverse settings what more beautiful, more ample subject could indulge the ambition of a director?

But there was also some audacity in the treatment. The book, where the descriptions are so powerful, could crush a film, as it happened with the play based on the grand work, although that play, which premiered 2 years after the novel, has had multiple revivals. The test, however, was passed. There is no reason to praise M. Fescourt for his fidelity to the action which he couldn’t touch without some manner of sacrilege. [?] What makes the merit of this thoughtful work, is the restoration of that which constitutes the best soul of the epic, of which Hugo told Charles Edmond: “Dante made hell with poetry; me, I attempted to make it with reality.”

The director acted counter to the custom of scattering the scenes, passing from one place to the next brusquely, and by tightening the scenes so that they follow each other logically the film increases in interest, in emotion, and also in harmony. This is an example to follow: we have really abused viewers in the process of dispersing scenes. [?]

It was the first two epochs that were presented. These parts begin with the arrival of the liberated convict Jean Valjean at Digne and his charitable welcome by Monseigneur Miriel to the death of Fantine and the adoption of Cosette, after which Jean Valjean, having sought to redeem himself for himself under the name of M. Madeleine, evades prison which he had returned to so that an innocent would not be condemned in his place. What great motifs for a great fresco!

One reminder about Misérables, it was first called Manuscript of a Bishop when Hugo did not yet see the developments he would give to his work. We know that, in painting the truly evangelical pastor that is Monseigneur Miriel, he was not depicting an imaginary character in those first pages. While he gave him another name, he was thinking of Monseigneur Bienvenu de Miollis, who was, actually, the Bishop of Digne, where he left the tradition of his charity. Monseigneur Miriel was given all of his virtues by Victor Hugo, he made him a saint who takes pity on all the miserables of humanity. Yet when the novel was published, a nephew of Monseigneur de Miollis, recognizing his uncle in the bishop of the novel, stood up against the portrait which had been traced.

It was probably the first time that a protest was raised because a celebrated writer adorned with too many moral beauties a man whose life he had evoked.

Les Misérables has found an interpretation with much depth with M. Gabrio, powerfully expressive as Jean Valjean; with Mlle. Sandra Milowanoff, in turns touching or charming in the double role of Fantine and Cosette; with MM. Paul Jorge, Rozet, Saillard; Mmes Nivelle, Renée Carl. M. Toulout gave all his picturesqueness to the face of Javert.

9 notes

·

View notes