#Jeff Bezos editore

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Bezos ci crede veramente: La decisione di Jeff Bezos e l’etica dell’informazione al Washington Post

Michele Serra su La Repubblica analizza la scelta dell’editore di limitare l’endorsement per Kamala Harris: un atto di integrità o convenienza?

Michele Serra su La Repubblica analizza la scelta dell’editore di limitare l’endorsement per Kamala Harris: un atto di integrità o convenienza? Nell’articolo Bezos ci crede veramente, Michele Serra, editorialista di La Repubblica, esplora una decisione controversa di Jeff Bezos, proprietario del Washington Post: la scelta di impedire ai giornalisti del quotidiano di fare endorsement espliciti…

#Amazon e media#analisi Michele Serra#autonomia dei media#decisione di Jeff Bezos#decisioni editoriali#endorsement politico#etica giornalistica#fiducia nei media#giornalismo e politica#giornalismo etico#giornalismo responsabile#giornalismo USA#imparzialità dei media#indipendenza editoriale#influenza politica#integrità editoriale#integrità giornalistica#integrità nel giornalismo#Jeff Bezos#Jeff Bezos decisioni#Jeff Bezos editore#Jeff Bezos opinioni#Kamala Harris#Kamala Harris endorsement#libertà editoriale#media americani#media e interessi politici#media e trasparenza#Michele Serra#Michele Serra Repubblica

0 notes

Text

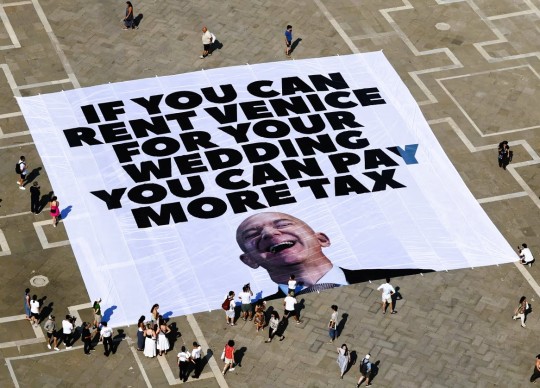

‘One man rents a city for three days? That’s obscene’

The Amazon boss, Jeff Bezos, is about to descend on Venice with his fiancee, some ex-Marines and his limitless credit card. We meet the Italian activists who are saying: enough

When she heard that Jeff Bezos was getting married in Venice this June, Heather Jane Johnson felt worse than she had in her entire life. Twenty-five years ago, she ceased trading as a bookseller in Boston, Massachusetts. “I lost a lot because of Bezos and the complicity of Americans in the making of Amazon,” the 53-year-old says. “A big reason I moved to Italy is because I felt betrayed by my countrypeople.”

So when posters went up calling a public meeting in the city she now calls home, she went, and she has been to every meeting of anti-Bezos activists since, including one the day before her own wedding last week. “These young people have really restored my faith in humanity,” Johnson says.

Many of the No Space for Bezos activists are based in Laboratorio Occupato Morion, which describes itself as an “anti-fascist, anti-capitalist, anti-racist and trans-feminist political space”. “Let’s say that this is the house of many struggles,” says Federica Toninello, 33. It has the same vaulted ceiling and grand proportions as its neighbours, but is full of banners and placards, ready to festoon Venice for Bezos’s wedding celebrations, which are due to start on Thursday. (I spotted no billionaires when I visited on Sunday, but then they have a powerful drive towards invisibility.) It could be any countercultural collective, except this is Venice, so everything is a hundred times more beautiful. Striking, timeless graphics from past campaigns plaster the walls – No Big Ships, an anti-cruise, anti-tourist campaign, which started here before spreading across Europe; No One Is Illegal, a grassroots refugee solidarity movement; posters on the climate crisis, the housing shortage, and one from a pop-up feminist union representing the city’s maids.

Noemi Donà, 19, is from the USG (loosely, the union of left youth); Oliver, 43, came via the “Sardines”, an anti-racist group set up to fight the hard-right Lega Nord. He works as a receptionist in a Venice hotel – not one of the hyper-luxe ones, just “a small, 14th-century palace” – but has his eye on the economy beyond tourism. “Bezos can pay, he can stay,” he says, “but thousands of shops in Italy have closed because of Amazon. So I don’t think he is welcome.” There’s a university collective that meets here, which occupied a number of campuses last year, protesting about the Israeli bombardment of Gaza.

The air is delicious and a bit headachey with the smell of aerosol and felt-tip pens. Some banners say Free Palestine; others say Stop Bombing Iran. Palestina Libre is an active organisation across Italy, and the US’s attack on Iran is still less than 24 hours old and deeply shocking. But if No Space for Bezos – “it’s not a collective, it’s a platform”, says Marta Sottoriva, a 34-year-old secondary school teacher – has ambitions that feel unimaginably large, it has already achieved some of what it wants, after only a few weeks.

“If Bezos had announced his marriage here, and we hadn’t moved, the narrative in the world’s media would have been the luxury hotels, the VIPs, the dresses, the gossip,” says Sottoriva. “We really wanted to problematise the ridiculous and obscene wealth that allows a man to rent a city for three days.”

On 12 June, the movement unfurled its simplest and largest banner – eight metres long, featuring just Bezos’s name crossed out in red – down the bell tower of the San Giorgio Maggiore basilica, while the deeply unpopular city mayor, Luigi Brugnaro, was trying to do a press conference. Toninello laughingly describes their slanging match on social media: “He was saying, ‘For shame!’ and we were saying, ‘You should be ashamed!’” Activists put up a similar banner on the Rialto bridge in the same week.

They have already shifted the focus from: “How much money does that one man have?” to the more interesting: “How much disruption can No Space for Bezos cause? What kind of numbers will they get? What conversations will they start?” Between Elon Musk handing voters million-dollar cheques and Vladimir Putin ordering up chaos and death like consumables, there is this awful sense of limitlessness to the elite’s purchasing power. If it turned out there was something a billionaire couldn’t buy, and it was something that ought to be simple – a little goodwill, servility, privacy and respect, for him, his fiancee Lauren Sánchez and their 200 friends – well, that would be a really big deal.

Not all the direct action this week will be announced in advance, but one thing has not been kept secret: this Saturday, there will be a demo to block access to the cavernous Scuola Grande della Misericordia, where Bezos planned to hold a big party.

I walked around the building on Sunday evening, just to see what kind of numbers you’d need on the protest to really, comprehensively screw the chance of Kim Kardashian showing up. Along the north wall is a pavement of probably three metres, with a steep drop into the canal, and a narrow bridge, the walkway ending randomly, Venetianly, in a metal gate. The west side has a wider pavement, again with the canal running alongside, with a little bridge to the left that could let police in or protesters out, but only in slow-moving units of maybe seven at a time. It is the most beautiful bridge in the world, unless you count all of Venice’s other bridges, but it’s not built for speedy access. At the front, a square, Misericordia on one edge, canal on the other; 200 protesters could make a lot of trouble for you here.

The rumour is that Bezos is not relying solely on the police but is bringing ex-marines with him, which has only served to make him less popular. “How can you move away a person from the water without injuring that person?” Toninello asks, her tone much more playful than anxious. “We are using our bodies to say: ‘Stop. No more. We don’t want this.’”

According to media reports on Monday, Bezos has been forced to move the party to another venue.

Even if you can picture the city’s exquisite eccentricities – bridges that stop dead at a front door, like the 14th-century lagoon equivalent of a lift that opens into your penthouse; alleyways with framed paintings stuck on the walls, as if that were normal – you still, I promise you, would not understand without pacing it how comically impossible it would be to have an elegant, star-studded party here if even 15 people made it their business to tell you that you weren’t welcome. It crossed my mind that maybe Venice is a decoy, and they’re actually having the parties in Maui.

The activists’ assemblies aired everything – critics say Bezos and Sánchez aren’t great targets for the anti-tourist movement, since they’re bringing just 200 guests, a drop in the ocean for a city that receives 30 million visitors a year. Yet in almost every scenario, Venetians perceive the same disregard from local government. It will effectively close down the centre of the city to please a billionaire; it has the power to limit Airbnb rentals, but declines to do so; it thinks last year’s tourist levy of €5 a day has solved the problem, but seemingly doesn’t consider that, as Sottoriva says, locals “really feel like animals in a zoo, or cartoon characters in Disneyland”.

Sofia, 26, is originally from Barcelona, so she has been around these discussions of overtourism often enough, but she sees something unique in this city, for good and ill. “There is a hidden Venice, which I was lucky enough to find through activism. A very vibrant community where you know each other, and support each other. I don’t mean an intellectual movement – I mean there are places where people do live, where they have neighbourhood suppers, where you can see children playing. The place risks becoming lifeless if you never see children.”

The political vision for a depopulated Venice – made of tourists, its workers coming in from the mainland, and existing as a one-of-a-kind theme park – is made obvious in the mayor’s dealings with the Bezos nuptials. But it also seems to chime with the values of the Amazon boss himself: his behaviour as an employer, his manifest resentment of corporate tax responsibility, an antisocial, anti-equality attitude that you’d be able to see from space, if he thought you were worthy of going there.

Climate change activists have other, intersecting complaints. Never mind that Amazon “promotes a culture of extreme, overexaggerated consumption”, says Stella Faye, a 27-year-old university researcher, “it represents a model of exploitation of people and of nature. It depends on huge amounts of electricity, for the servers, and then huge amounts of water resources to cool the servers, which are often placed in arid areas. So they’re taking water resources from regions where people desperately need them.”

Politically, Bezos has swung from what everyone always assumed was mild support for the Democrats to active support for Trump. “We are not seeing a multibillionaire bending to Trump,” Sottoriva says, “we are seeing a new political grammar in which the private interests of digital capitalism and technocapitalism merge with fascism. This is not just about Venice.”

What might conceivably trouble Bezos the most is the burgeoning critique of billionaires not as individuals, but as a structural force. “I would say anti-wealth movements are new,” says Robin Piazzo, a political scientist from Turin university. “Usually Marxists don’t like to focus on people like billionaires: they use concepts such as capitalism, objective things, not specific people. So most of the extra-parliamentary left avoided the wealthy themselves. And when the institutional left focused on, for example, Berlusconi, it was not framed as: ‘He is too rich.’ The problem was that he was using his money to influence politics and the media. It was always about good billionaires and bad ones, because they wanted to co-opt the good ones.”

At a grassroots level, however, there has always been a strong strain of anti-wealth critique, the one thing religion and politics could agree on. Piazzo is also a city councillor for the Democratic party, the largest centre-left party. A 90-year-old woman came up to him after the last council meeting and said, “You have to do something about rich people, I hate them. I’m with Papa Francisco [Pope Francis].” This is a dangerous moment for the ultra-high-net-worths: when wealth itself is seen to be acting in its own interests, and it has accumulated to the degree that its impact scars every poorer life with which it comes into contact, that starts to look a lot like a class war, albeit with one side very small (there are roughly 2,700 billionaires in the world; they could fit into a regional concert hall) and, until recently, almost invisible.

So at some point, wealth will show its teeth. I think back to the last protest I went to in Italy, the G8 summit in Genoa, 2001. The policing was unbelievably reactive and harsh; a protester called Carlo Giuliani was shot dead on the first night by the carabinieri. I was with British lefties, whose first reaction when the police come at you is to run down a side street – a great strategy if you’re being charged by a horse, a terrible idea if you’re being teargassed. You get stuck in this well of gas, and it gets in your eyes.

After the death of Giuliani, the Corpo Forestale was brought in: very distinctive uniforms, powder blue with knee-high black boots, hitting people with batons, a little bit like Nazis choreographed by Busby Berkeley. But what was most surreal was that the G8 had already erected an almost impenetrable metal fence. Only one protester managed to get through and she was arrested immediately. In that steel-ring protection was an admission: that those heads of state were the enemy, all our interests were not aligned.

Twenty-four years later, there’s something gaslighty in Bezos’s decision that he could represent all he represents – wage degradation, hyper-consumerism, environmental destruction, wealth supremacy – and still be a regular Joe that the people of Venice would be happy for, because he’d met his special person. What an out-and-out bizarre and provocative place to say that – a city with non-negotiable borders and a cliff edge into a canal every 50 yards. “I am afraid, personally,” says Noemi Donà. “But I’m here.”

Daily inspiration. Discover more photos at Just for Books…?

#just for books#message from the editor#Jeff Bezos#Weddings#Activism#Venice#Italy#The super-rich#Europe#features#opinion

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

0 notes

Text

i know this is a direct correlation to mass markets stopping production but i meant this at hpb!!!!!! also!!!!!! last time i visited b&n i didnt even see the MMP, so like how are we supposed to keep them floating if i cant even buy new ones. dont say amazon dont say amazon dont say amazon

shoutout to people feeling like theyre too good for mass market paperbacks, that just means more books for me hehehe

#never did i know that becoming a reader again would cause so much pain#loss of mmp#book prices are a trillion dollars per book#publishers dont utilize editors like they have previously and book covers are ugly#im blaming jeff bezos for this this is all his fault

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

More than 75,000 digital subscribers to The Washington Post have cancelled since its owner, billionaire Amazon founder Jeff Bezos, announced on Wednesday that he would radically overhaul the paper's opinion pages to reflect libertarian priorities and to exclude opposing points of view.

Wednesday's announcement led to the immediate resignation of Opinions Editor David Shipley. He had vainly sought to persuade Bezos to drop the plans, according to a person with direct knowledge. Shipley did not respond to requests for comment.

Bezos' decision also prompted an outcry from longtime Post figures, including Associate Editor David Maraniss and former Executive Editor Marty Baron. Baron called the move "craven" and told Zeteo News that Bezos, whom he praised extensively in his 2023 memoir, was "basically fearful" of President Trump.

272 notes

·

View notes

Text

It has fallen to me, the humor columnist, to endorse Harris for president

Isn’t this what a newspaper is supposed to do?

I love that The Washington Post satirist Alexandra Petri took it upon herself to endorse Harris for her paper after Bezos pulled the plug on the editorial board doing so. This is a gift🎁link, so feel free to read the entire article. Below are some excerpts:

The Washington Post is not bothering to endorse a candidate in the 2024 presidential election. (Jeff Bezos, the founder of Blue Origin and the founder and executive chairman of Amazon and Amazon Web Services, also owns The Post.) We as a newspaper suddenly remembered, less than two weeks before the election, that we had a robust tradition 50 years ago of not telling anyone what to do with their vote for president. It is time we got back to those “roots,” I’m told! Roots are important, of course. As recently as the 1970s, The Post did not endorse a candidate for president. As recently as centuries ago, there was no Post and the country had a king! [...] But if I were the paper, I would be a little embarrassed that it has fallen to me, the humor columnist, to make our presidential endorsement. I will spare you the suspense: I am endorsing Kamala Harris for president, because I like elections and want to keep having them. Let me tell you something. I am having a baby (It’s a boy!), and he is expected on Jan. 6, 2025 (It’s a … Proud Boy?). This is either slightly funny or not at all funny. [...] Well, that world [the baby will be born into] will look very different, depending on the outcome of November’s election, and I care which world my kid gets born into. I also live here myself. And I happen to care about the people who are already here, in this world. Come to think of it, I have a lot of reasons for caring how the election goes. I think it should be obvious that this is not an election for sitting out. The case for Donald Trump is “I erroneously think the economy used to be better? I know that he has made many ominous-sounding threats about mass deportations, going after his political enemies, shutting down the speech of those who disagree with him (especially media outlets), and that he wants to make things worse for almost every category of person — people with wombs, immigrants, transgender people, journalists, protesters, people of color — but … maybe he’ll forget.” “But maybe he’ll forget” is not enough to hang a country on! [...] I’m just a humor columnist. I only know what’s happening because our actual journalists are out there reporting, knowing that their editors have their backs, that there’s no one too powerful to report on, that we would never pull a punch out of fear. That’s what our readers deserve and expect: that we are saying what we really think, reporting what we really see; that if we think Trump should not return to the White House and Harris would make a fine president, we’re going to be able to say so. That’s why I, the humor columnist, am endorsing Kamala Harris by myself! [color/ emphasis added]

How far The Washington Post has fallen into the "darkness" it used to work so hard to ward off to help keep our democracy alive.

[edited]

#the washington post#jeff bezos#failure to endorse a presidential candidate#election 2024#harris#trump#alexandra petri#satire#democracy dies in darkness#gift link

696 notes

·

View notes

Text

In an effort to patch things up in their relationship, billionaire Jeff Bezos reportedly changed The Washington Post‘s slogan to “Love You, Babe” Tuesday��after getting into a fight with his fiancée, Lauren Sánchez. “As of now, these words of affection are emblazoned on The Post‘s homepage and on all copies of the newspaper, and they will remain there until the two of them make up,” said executive editor Matt Murray, adding that instead of the traditional black, the paper’s articles would be printed in lilac, which is reportedly Sánchez’s favorite color.

Full Story

264 notes

·

View notes

Text

I’ve worked for the Washington Post since 2008 as an editorial cartoonist. I have had editorial feedback and productive conversations—and some differences—about cartoons I have submitted for publication, but in all that time I’ve never had a cartoon killed because of who or what I chose to aim my pen at. Until now.

The cartoon that was killed criticizes the billionaire tech and media chief executives who have been doing their best to curry favor with incoming President-elect Trump.

There have been multiple articles recently about these men with lucrative government contracts and an interest in eliminating regulations making their way to Mar-a-lago. The group in the cartoon included Mark Zuckerberg/Facebook & Meta founder and CEO, Sam Altman/AI CEO, Patrick Soon-Shiong/LA Times publisher, the Walt Disney Company/ABC News, and Jeff Bezos/Washington Post owner.

While it isn’t uncommon for editorial page editors to object to visual metaphors within a cartoon if it strikes that editor as unclear or isn’t correctly conveying the message intended by the cartoonist, such editorial criticism was not the case regarding this cartoon. To be clear, there have been instances where sketches have been rejected or revisions requested, but never because of the point of view inherent in the cartoon’s commentary. That’s a game changer…and dangerous for a free press.

Over the years I have watched my overseas colleagues risk their livelihoods and sometimes even their lives to expose injustices and hold their countries’ leaders accountable. As a member of the Advisory board for the Geneva based Freedom Cartoonists Foundation and a former board member of Cartoonists Rights, I believe that editorial cartoonists are vital for civic debate and have an essential role in journalism.

There will be people who say, “Hey, you work for a company and that company has the right to expect employees to adhere to what’s good for the company”. That’s true except we’re talking about news organizations that have public obligations and who are obliged to nurture a free press in a democracy. Owners of such press organizations are responsible for safeguarding that free press— and trying to get in the good graces of an autocrat-in-waiting will only result in undermining that free press.

As an editorial cartoonist, my job is to hold powerful people and institutions accountable. For the first time, my editor prevented me from doing that critical job. So I have decided to leave the Post. I doubt my decision will cause much of a stir and that it will be dismissed because I’m just a cartoonist. But I will not stop holding truth to power through my cartooning, because as they say, “Democracy dies in darkness”.

Thank you for reading this.

—Ann Telnaes

#politics#ann telnaes#jeff bezos#washington post#political cartoons#editorial cartoons#free press#oligarchy#crony capitalism

299 notes

·

View notes

Text

There was a writer at io9 who I lowkey viewed as my nemesis despite never interacting with him in any way because whenever I encountered an article with an absolutely dogshit shallow take on pop culture 9 tiems out of 10 it was written by him, and generally in mindless praise of Star Wars. I bring this up because before I quit reading the site he posted an article called "I don't get why geeks don't like sports" or something like that, and the thesis of the article was that geeks who love sci-fi and fantasy fiction should LOVE sports because they're basically the same thing - that everything one loves about sci-fi and fantasy fiction can be found in sports. To which I say:

No the fuck it can't

You, a man who is paid to write about geek shit for geeks to read about because your editors inexplicably believe you know why geeks like what they like, clearly lied on your resume

The argument went that sports have everything sci-fi and fantasy fans like, which it specified were, like, stakes, and drama, and people to root for and against, which is basically all it takes to make a sci-fi story, right? Like Jesus Christ it was so stupid, like, Jeff Bezos described how easy it is to make a great TV show stupid.

BUT! It did give me an idea. See, one of the big appeals to me about sci-fi and fantasy stories is the fantastical shit that shows up in them, like monsters, for example. Another big appeal is to see a how our current world can be reflected in the fantastical one - whether we see a better world, or one that's worse in a very dramatic way.

So, here is my suggestion for making sports just like fantasy and sci fi fiction: we add a new position to every single sport called The Minotaur. The Minotaur wears heavy body armor as well as a big, intimidating horned helm, and brandishes an axe with deadly efficiency. The Minotaur is a free agent, allowed to wander in and out of the stadium/ice rink/golf course/what have you as he pleases, but he must attempt to kill one player per game. The players are not allowed to take weapons into the game to defend themselves - only through sheer athleticism can they either evade or disarm the Minotaur, and in doing so save themselves.

If they did this, then finally they'd have everything I love in my sci-fi and fantasy movies in sports.

467 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Washington Post is working on plans to get content from alternative sources like Substack contributors and “nonprofessional writers��� aided by an AI editor and writing coach, reported The New York Times’ media reporter Ben Mullin.

The new content strategy comes after months of turmoil at the Post as staffers have bristled at efforts by owner Jeff Bezos and publisher and CEO Will Lewis to cut costs, increase revenue, and adopt a more right-leaning, MAGA-friendly tone, including directing the paper to forgo an endorsement of Vice President Kamala Harris last fall and a February staff-wide email from Bezos announcing a “new direction” for the Opinion Section.

According to Mullin’s report Tuesday afternoon, the program has been internally named “Ripple” and the research and development for it started over a year ago. It seeks to “sharply expand” the Post’s lineup of columnists in an effort to “appeal to readers who want more breadth than The Post’s current opinion section and more quality than social platforms like Reddit and X.”

65 notes

·

View notes

Text

More “obeying in advance” by the Washington Post

I haven’t referred or cited to the Washington Post since Jeff Bezos ordered the editorial board not to endorse Kamala Harris for president. I sometimes wonder whether that was the right decision. Today, it became clear it was.

Editorial cartoonist Ann Telnaes just published an article on Substack entitled, Why I'm quitting the Washington Post. Telnaes explains that she prepared an editorial cartoon that showed billionaires bowing in supplication to Trump. The cartoon is in the linked article. As explained by Telnaes,

The group in the cartoon included Mark Zuckerberg/Facebook & Meta founder and CEO, Sam Altman/AI CEO, Patrick Soon-Shiong/LA Times publisher, the Walt Disney Company/ABC News, and Jeff Bezos/Washington Post owner.

Telnaes explains,

For the first time, my editor prevented me from doing that critical job [publishing the cartoon]. So I have decided to leave the Post. I doubt my decision will cause much of a stir and that it will be dismissed because I’m just a cartoonist. But I will not stop holding truth to power through my cartooning, because as they say, “Democracy dies in darkness”.

Ann Telnaes deserves our respect and admiration for her courage. And the ongoing disgrace at WaPo should cause all self-respecting journalists and columnists to follow Ann Telnaes’s example.

[Robert B. Hubbell Newsletter]

#Robert B. Hubbell#Robert B. Hubbell Newsletter#Ann Telnaes#The Washington Post#WAPO#journalism#billionaires

69 notes

·

View notes

Text

‘A marker of luxury and arrogance’: why gravity-defying boobs are back – and what they say about the state of the world

Breasts have always been political – and right now they’re front and centre again. Is it yet another way in which Trump’s worldview is reshaping the culture?

It was, almost, a proud feminist moment. On inauguration day in January, the unthinkable happened. President Trump, the biggest ego on the planet, was upstaged by a woman in a white trouser suit – the proud uniform of Washington feminists, worn by Kamala Harris, Hillary Clinton and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez in solidarity with the traditional colour of the suffragettes. In the event, the white trouser suit barely got a mention. The show was stolen by what was underneath: Lauren Sánchez’s cleavage, cantilevered under a wisp of white lace. The breasts of the soon-to-be Mrs Jeff Bezos were the ceremony’s breakout stars. The only talking point that came close was Mark Zuckerberg’s inability to keep his eyes off them.

Call it a curtain raiser for a year in which breasts have been – how to put this? – in your face. Sydney Sweeney’s pair have upstaged her acting career to the point that she wears a sweatshirt that says “Sorry for Having Great Tits and Correct Opinions”. Bullet bras are making a sudden comeback, in sugar-pink silk on Dua Lipa on the cover of British Vogue and nosing keen as shark fins under fine cashmere sweaters at the Miu Miu show at Paris fashion week. Perhaps most tellingly, Kim Kardashian, whose body is her business empire, has made a 180-degree pivot from monetising her famous backside to selling, in her Skims lingerie brand, push-up bras featuring a pert latex nipple – with or without a fake piercing – that make an unmissable point under your T-shirt. Not since Eva Herzigova was in her Wonderbra in 1994 – Hello Boys – have boobs been so, well, big.

It is oddly tricky to discuss boobs without sounding as if you are in a doctor’s surgery or a fraternity house. The word breasts is rather formal. Boobs is fond and familiar, which feels right, but sniggery, which doesn’t. Bosoms are what you see in period dramas. Knockers, jugs, melons, hooters, fun bags? Whatever we call them, they are full of contradictions. Men see them and think of sex; babies see them and think of food. They contain a liquid without which the human race could not until recently have survived, but they are also one of the most tumour-prone parts of the body. You can admire them in the Uffizi, the Louvre and the National Gallery, but they are banned on Instagram (Free the nipple!). They are nursing Madonnas, and they are Madonna in a conical bra. They are topless goddesses and top shelf; entirely natural yet extremely rude; and they are, right now, absolutely everywhere.

There is a whole lot going on here. In America, the impact of the Trump administration is going way beyond policy, reshaping culture at a granular level. The Maga ruling class has a thirst for busty women in tight clothes, which fuses something new – what Zuckerberg has called “masculine energy” – with nostalgia for 1950s America. (The “again” in Make America Great Again may not have a date stamp, but it comes with a white picket fence.) As a symbol of fertility, full breasts are catnip to a regime obsessed with breeding and keen to limit reproductive freedoms.

Boobs are in the eye of the storm of the current gender fluidity rollback, too. Nothing says boys will be boys and women should look like women more than Bezos’s Popeye biceps next to Sánchez’s lace-edged curves. They used to say that a picture was worth a thousand words; in today’s ultra-visual culture, that rate of exchange has steepened. The fact that a culture that was, until a few years ago, sensitively exploring gender as a complex issue has now regressed to the level of teenage boys watching American Pie for the first time says everything about how things have changed.

Since 1962, when Timmie Jean Lindsey, a mother of six from Texas, became the first woman in the world to have silicone implants, breasts have been a lightning rod for the battleground between what is real and what is fake. The debate that catapulted Pamela Anderson to fame in the 1990s has become one of the defining issues of our time. It turns out that breasts, and beauty, were just the start. Artificial intelligence has jumped the conversation on. From Mountainhead to Black Mirror, we are now talking not just about real boobs v fake ones but about real brains v fake ones. In the battle between old-school flesh and blood and the prospect of a new, possibly improved, version of the human race, breasts have been leading the culture for 63 years.

In a nutshell, the world is losing its mind over the girls. “The State of the Union is … boobs” was the New York Post’s succinct verdict on the charms of Sweeney, while Amy Hamm wrote in the National Post that they were “double-D harbingers of the death of woke”. On inauguration day, onlookers were divided between outrage at an inappropriate level of nudity and admiration for how Sánchez’s “Latina auntie” energy showed her, um, balls.

All of which makes it a weird time to have breasts. When writer Emma Forrest saw the author portrait taken for the jacket of her new novel, Father Figure, her first thought was, “Oh wow, my boobs look huge.” She is wearing a plain black T-shirt, “so that must be OK, right? It’s not like I’m wearing a corset. I feel I should be allowed to have people review my books without having an issue with my boobs. But who knows.”

Breasts have always had the power to undermine women. After a double mastectomy and reconstructive surgery, Sarah Thornton found herself with much bigger breasts than she had wanted – having asked for “lesbian yoga boobs”, she woke up with D cups – and wrote her book, Tits Up, to make peace with her “silicone impostors” by investigating their cultural history. Breasts, she writes, are “visible obstacles to equality, associated with nature and nurture rather than reason and power”. Since she was a teenager, Forrest has lived with “the assumption that having big breasts means being messy, being sexually wild, having no emotional volume control. I have had to learn to separate my own identity from what other people read on to my body.” It’s Messy: On Boys, Boobs and Badass Women is the title of Amanda de Cadenet’s memoir, in which she writes about developing into “the teenage girl whose body made grown women uncomfortable and men salivate”, recalling the destabilising experience of having a body that brought her overnight success – she was a presenter on The Word at 18 – while simultaneously somehow making her the butt of every joke.

If the length of our skirts speaks to the stock market – short hemlines in boom times, long when things are bad – breasts are political. Thirty years after the French Revolution, Eugène Delacroix painted Liberty Leading the People with a lifesize, bare-breasted Liberty hoisting the French flag, leading her people to freedom. A century and a half later, women burning their bras at the 1968 protest against the Miss America pageant became one of the defining images of the feminist movement – never mind the fact that it never happened. (Protesters threw copies of Playboy, and some bras, in a trash can, but starting a fire on a sidewalk was illegal.) Intriguingly, decades when big breasts are in fashion seem to coincide with times of regression for women. Think about it. The 1920s: flat-chested flapper dresses and emancipation. The 1950s: Jayne Mansfield and women being pushed away from the workplace and back into the home. The 1970s: lean torsos under T-shirts, and the women’s liberation movement.

Sarah Shotton started out as an assistant in Agent Provocateur’s raunchy flagship store in Soho, London, in 1999, when she was 24, and rose to become creative director of the lingerie brand in 2010. Her 15 years in charge have seen Agent Provocateur rocked by the changing tides of sexual politics. In 2017, the year #MeToo hit the headlines, the company went into administration, before finding a new distributor. Shotton says, “I have always loved sexy bras, and it’s what we are known for. But there was a time when it felt like that wasn’t OK. Soon after #MeToo, we had a campaign lined up to shoot and the phone started ringing with all the agents of the women who were supposed to be in it, pulling their clients out, saying they didn’t want to be seen in that way.”

But the brand’s revenues have doubled in the past three years. “Last year we shot a film with Abbey Clancy and Peter Crouch, where she’s in really sexy lingerie and he’s playing pool. I remember saying, ‘This is either going to go down like a ton of bricks or people are going to love it.’” It seems as if they loved it: the company’s sales are expected to hit £50m this year. “I think a younger generation now want what we had in the 1990s and 2000s,” Shotton says, “because it looks like we had more fun. My generation of women had childhood on our BMX bikes, then when we were in our 20s, your job finished when you left the office and you could go out drinking all night if you wanted to. I think we really did have more fun. Life just didn’t feel as complicated as it does now.” The bestselling bras, she says, are currently “anything plunging and push-up. Racy stuff. Our Nikita satin bra, which is like a shelf for your boobs and only just covers your nipples.”

The legacy of the 1990s, when feminism and raunch became bedfellows, has left the world confused about breasts. Before that, the lines were pretty simple – the flappers throwing off their corsets, the feminists protesting over Page 3. But Liz Goldwyn, film-maker and sociologist (and granddaughter of Samuel Goldwyn Jr), whose first job was in a Planned Parenthood clinic and who collects vintage lingerie, doesn’t fit neatly into any of the old categories. “Third-wave feminists like myself grew up in the riot grrrl and burlesque days, where we embraced corsets and kink along with liberation and protest,” she says. Goldwyn collects, loves and wears vintage lingerie, while abhorring Spanx. “I would rather go to the dentist than wear shapewear, but I find nothing more satisfying than to colour-coordinate my lingerie drawers.” Wearing a corset, she says, “makes me breathe with more presence”.

Breasts have always been about money and class as well as sex and gender. The Tudor gentlewomen who wore dresses cut to expose their small, pert breasts were proudly indicating they had the means to afford a wet nurse. Sánchez’s inauguration outfit – tiny white Alexander McQueen trouser suit, lots of gravity-defying cleavage – “taps into the fact that people who are that wealthy can have the impossible,” Forrest says. “It is pretty difficult to have a super-slim body and big breasts. Her body is a physical manifestation of something much bigger, which is the hyper-wealthy living in a different reality to the rest of us. The planet might be doomed, but they can go to space. It’s a ‘fuck you’ marker of luxury and arrogance.” The vibe, Goldwyn agrees, “is very dystopian 1980s Dynasty meets ‘let them eat cake’. I would never disparage another woman’s body, but I have no problem disparaging her principles … in claiming to stand for women’s empowerment, yet attending an inauguration for an administration that has rolled back reproductive freedoms.”

Surgery – the blunt fact of boobs being a thing you can buy – has crystallised the idea of breasts as femininity’s biggest commercial hit. (They are at times referred to, after all, as prize assets.) The primitive – survival of the fittest, in the thirsty sense of the word – is now turbocharged by capitalism.Breast enlargement is the most popular cosmetic surgery in the UK, with 5,202 procedures carried out in 2024, according to the British Association of Aesthetic Plastic Surgeons.

When Jacqueline Sanchez Taylor interviewed women in 2010 about their experiences of breast augmentation for her research into the sociology of cosmetic surgery, “a lot of young women told me they were doing it for status”. Not to show off, but to show “they had made it. They felt they were being good citizens: going out there and making money, but also wanting to play the part of being feminine.” Breasts, Sanchez Taylor says, “say everything about who a woman is: about femininity and fertility, class and age.” They are at the centre of the industrial complex that has grown up around female beauty. “I remember sitting in a consultation with a woman and her surgeon, and him saying cheerfully, ‘Oh yes, you’ve got fried egg breasts. But we can fix that.’”

Fake is no longer scandalous or transgressive. The vocabulary of plastic surgery has been gentled and mainstreamed to become the more palatable cosmetic surgery. The older women of the Kardashian family have been coy about having had work, but 27-year-old Kylie Jenner recently shared on social media the details of her breast surgery – down to the implant size, placement and name of surgeon. Unreal is here to stay, and the new battle line is between perfection and imperfection. The generation growing up now, who have never seen a celebrity portrait that wasn’t retouched, have never used a camera that doesn’t have filters, take 20 selfies and delete 19 of them, have an intolerance of imperfection. To put it bluntly: normal looks weird to them.

So it seems natural – even if it isn’t really natural – that celebrity boobs are getting bigger even as celebrity bodies are getting smaller. “We are in a really weird place with the body, particularly in America,” says Emma McClendon, assistant professor of fashion studies at St John’s University in New York, who in 2017 curated the New York exhibition The Body: Fashion and Physique. “What we are seeing now is definitely not about the bigger body. It is a very controlled mode of curviness, which emphasises a tiny waist.” (Very 1950s coded, again.) “GLP-1 weight-loss drugs are having a cultural impact on all of us, whether or not you or people you know are on them,” McClendon says. “The incredible shrinking of the celebrity body that is happening in America is creating this idea that your body is endlessly fixable and tweakable.” Hairlines can be regrown, fat melted, wrinkles erased.

For most of the past half-century, fashion has held out against boobs. With a few notable exceptions – Vivienne Westwood, rest her soul, adored a corset-hoisted embonpoint – modern designers have mostly ignored them. Karl Lagerfeld insisted his models should glissade, ballerina style, and disliked any curves that veered from his clean, elongated lines. And yet in the past 12 months, the bullet bra has come back. A star turn on the Miu Miu catwalk was presaged last year by a cameo in the video for Charli xcx’s 360, worn by photographer and model Richie Shazam, and by influencer and singer Addison Rae, whose lilac velvet corset creamed into two striking Mr Whippy peaks at a Young Hollywood party last summer. To seal the revival, none other than the queen of fashion – Kate Moss – wore a bullet bra under her Donna Karan dress in a viral fashion shoot with Ray Winstone for a recent issue of Perfect magazine.

Perhaps the bullet bra, which can be seen as weaponising the breast, is perfect for now. “Fashion is the body, and clothes turn the body into a language,” McClendon says. The bullet bra is steeped in a time when “domestic femininity was repackaged as glamour”, Forrest says. “A postwar era, coming back from scarcity and lack and hunger, when Sophia Loren was sold as a kind of delicious luxury truffle.”

Goldwyn is a fan. “A perfectly seamed bullet bra lifts my spirits (and my breasts) if I am in a foul mood,” she says. “I hope we can reclaim it as symbolic of resistance, defiance and armour.” In the backstage scrum with reporters after she had made bullet bras the centrepiece of her Miu Miu catwalk show, Miuccia Prada said the collection was about “femininity”, then she corrected herself: “No – femininities.” Prada has been using her clothes to articulate the complexities of living and performing femininity for decades, and this season it led her to the bullet bra. “What do we need, in this difficult moment for women – to lift us up?” she laughed, gesturing upwards with her hands, surrounded by pointy-chested models. “It’s like a new fashion. I think the girls are excited.”

Half a millennium after Leonardo da Vinci painted the Madonna Litta, his 1490 painting of the Virgin Mary baring her right breast to feed Christ, which now hangs in the State Hermitage Museum in St Petersburg, Russia, another Madonna found her breasts in the spotlight. In the late 1980s, Jean Paul Gaultier was experimenting with conical bras in his Paris shows. “He took inspiration from his grandmother’s structured undergarments,” says fashion historian Amber Butchart, “and used them to herald self-liberation. I don’t generally like the word empowering – it doesn’t tend to mean much – but that was very much the idea.” In 1989, while Madonna was preparing for her 1990 Blond Ambition world tour, she phoned Gaultier and asked him to design the wardrobe. On the opening night, in Japan, Madonna tore off her black blazer to reveal that iconic baby-pink satin corset with conical cups. “Do you believe in love? Well, I’ve got something to say about it,” she declared, before launching into Express Yourself. The silhouette, which could be seen all the way from the cheap seats, would end up scandalising the pope and costing the world’s biggest female pop star a lucrative Pepsi deal. Boobs have always been good at capturing our attention, and they have it right now. Hello again, boys.

Daily inspiration. Discover more photos at Just for Books…?

#just for books#message from the editor#opinion#Life and style#Kim Kardashian#Madonna#Cosmetic surgery#Jeff Bezos#Feminism#Donald Trump#features#Jayne Mansfield#Lauren Sánchez#Dua Lipa#Eva Herzigova#Wonderbra

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

gotta laugh at everyone who has ever said that "~unLiKE tHe pEtEr jACkSoN fILmS~ the trop people don't care about tolkien, don't care about middle-earth, it's a soulless adaptation for the money just because amazon is behind it" because (and i say this while also saying fuck amazon, fuck jeff bezos. it goes without saying - two things can be true at the same time, i can't believe it bears repeating)

how do you think films and television get made?? hate to break it to you, but it's all for the money. new line cinema didn't say "we love tolkien, pj, let's do this for free!" they were literally looking for a franchise hit when they decided to take the films over from miramax - which is exactly what every studio and their mom is trying to do now!!! it's movie business, baby! to say the people behind trop - the actors, the casting directors, the production designers, the vfx artists, the art directors, the armorers, the costume designers, the set decorators, the makeup artists, the ADs, the carpenters, painters, prop-makers, steelworkers, laborers, animal handlers, sound editors, miniature builders, stuntpeople, craftspeople, movement and dialect coaches, trainers, lighting techs, jewelers, etc. - don't care about the story they're telling???? is a wild reach. obviously they work for the showrunners who work for amazon who care the most about making a profit, but so did peter jackson and new line!! wanting your project to be financially and critically successful is not an inherently evil thing, come on guys, are you still buying into the starving artist fallacy 😭

there are tons of little nods to the silmarillion and other parts of the legendarium in the rings of power. yes, there are also changes and goofs, but lotr and the hobbit film trilogies also had their fair share of changes and goofs. i just think that "these people didn't read the books/this is just a money grab/pj & co. cared about the source material while these losers clearly don't" are tired arguments used to justify subjective opinions, not to mention the way it reeks of revisionist history considering the way tolkien purists initially took great issue with deviations made in lotr and especially the hobbit.

it's almost like...the most hated tolkien adaptation is ever the current one.

#lotr#the rings of power#it's quite funny to note in the lead-up to s2 how many people feel the need to say “i hated s1 BUT... 👀”#something about this fandom makes people so defensive and easily triggered and it's baffling#deciding something isn't to your taste and you'll be abstaining thanks doesn't require this much justification#neither does changing your mind or choosing to watch critically or deciding to enjoy the ride as it is#maybe it's the fact that people want to consider themselves lore-masters and like to lord it over others#that 'i know tolkien better than you and definitely better than these overpaid hacks'#....good for you that you're comfortable in that sort of obnoxiousness i guess?#but you show your hand when you make these blanket statements that objectively make no sense

74 notes

·

View notes

Text

Some Honor Bound Acknowledgements

Today I want to highlight the amazing jobs that lots of people did to get HONOR BOUND where it is. It wouldn't be anywhere near so polished without their hard work!

My editor Abigail C. Trevor pushes my games into shape from concept to release, from big-picture feedback to meticulous edits.

Abby has a particular knack for teasing out the potential of an idea and pushing it further. At the very early stages, the PC was assigned to Ozera because of an injury but not because of any particular other issues, and Elene's Prospect was not the PC's hometown (and therefore there was no prior connection with Denario)!

Abby also writes games! Her first game, Heroes of Myth, is about a con-artist called to really fix a magical crisis. Her latest, Stars Arisen, is a fantasy doorstopper about being the child of an immortal deposed tyrant queen who wants you to seize back control of the city-state. Highly recommended!

Kris Lorischild copyedited this 595K word monster. This would be a massive undertaking even without my tangles of code to deal with and Kris truly polished Honor Bound to make it shine.

Kris was narrative co-lead/localisation producer on Cozy Grove, created You Are Jeff Bezos and more, used to be Senior Curator for Critical Distance, and has copyedited 20 CoG games. Check out their itch page here!

Adrien Valdes aka @defenestratin did the cover art. Adrien's illustrated three of my games now and knocks it out of the park beautifully every time. He's also illustrated many other CoG and all of the Heart's Choice games. See more of Adrien's work here!

I don't know all the names of the continuity readers, and although I've tried to thank the playtesters directly, I may have missed some—but from finding bugs, to noticing typos or awkward sentences, to letting me know where I was falling short of my goals, their work was invaluable.

Jason Stevan Hill, Mary Duffy, and Dan Fabulich from the Choice of Games team worked wonderfully on this release. Special shoutout to Rebecca Slitt's editorial review of the full draft which guided me in expanding and enriching a ton of moments that needed it.

These days Rebecca is mostly an editor and runs the Heart's Choice label (and many of my favourite games were edited by her), but she also created Psy High, a brilliant teen-psychic CoG game!

Shortly after Honor Bound was released, my friend and fellow writer Eiwynn passed away. You can find out more about her here. Eiwynn was a tireless pillar of the ChoiceScript interactive fiction community, helping writers and players old and new. Ever since I started writing with ChoiceScript, she gave me support and encouragement, and I know she did this for many, many more writers.

Thank you for everything, Eiwynn. Your warmth and kindness will be sorely missed by me and countless others in the community.

Finally: my wife Fay Ikin is my first reader even at the concept stages and helps me arrange my ideas as well as helping me untangle when I'm struggling (in writing and in life!).

Teran is loosely based on her TTRPG campaign from many years ago. I'm very grateful that she let me steal her setting!

Fay isn't on social media, but she makes interactive fiction as well. She's best known for her intense gladiator-pit romance game HEART OF BATTLE in which you can fight and/or romance your fellow gladiators, a magic medic, or a fabulously wealthy patron. It's a brilliant game, and I would say that even if I wasn't married to her! She also made ASTEROID RUN: NO QUESTIONS ASKED, a gorgeous and very underrated scifi thriller.

Thank you to everyone who contributed to making HONOR BOUND what it is!

Steam | Google Play Store | Choice of Games on Android | Choice of Games on iOS | Choice of Games on Amazon | Webstore

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

I walked into the Washington Post building for the first time in the summer of 1981. Past the red linotype machine that marked the entrance to the Post’s Fifteenth Street headquarters for so many years and up to the fifth-floor newsroom, a cavernous space that looked just as it’s depicted in “All the President’s Men.”

I was fresh out of college and on my way to law school. Along the way, I’d worked at a small legal newspaper, where I found myself both interested in the subject and annoyed at being condescended to by lawyers about my lack of a degree. Bob Woodward, the Post’s Metro editor, had read some of my pieces and invited me in to talk. In fact, he tried to talk me out of law school. He told me that he had turned down Harvard to work for the Sentinel, a paper in Montgomery County, Maryland. Why not just come to the Post?

I gulped, and asked Woodward how old he had been then. Twenty-seven, he said. Great, I said, I’ll be twenty-six when I graduate from law school. I’ll be back. And I was, first as a summer intern, in 1982, and then as a full-time reporter, starting September 4, 1984, covering Prince George’s County, in suburban Maryland. I stayed for forty years, six months, and six days.

I stayed until I no longer could—until the newspaper’s owner, Jeff Bezos, issued an edict that the Post’s opinion offerings would henceforth concentrate on the twin pillars of “personal liberties and free markets,” and, even more worrisome, that “viewpoints opposing those pillars will be left to be published by others.” I stayed until the Post’s publisher, Will Lewis, killed a column I filed last week expressing my disagreement with this new direction. Lewis refused my request to meet. (You can read the column in full below, but—spoiler alert—if you’re craving red meat, brace for tofu. I wrote the piece in the hope of getting it published and registering a point, not to embarrass or provoke the paper’s management.)

Is it possible to love an institution the way you love a person, fiercely and without reservation? For me, and for many other longtime staff reporters and editors, that is the way we have felt about the Post. It was there for us, and we for it. One Saturday night, in May, 1992, the investigative reporter George Lardner, Jr., was in the newsroom when he received a call that his twenty-one-year-old daughter, Kristin, had been shot and killed in Boston by an abusive ex-boyfriend. As I recall, there were no more flights that night to Boston. The Post’s C.E.O., Don Graham, chartered a plane to get Lardner where he needed to go. It was typical of Graham, a kindness that engendered the loyalty and affection of a dedicated staff.

Graham’s own supreme act of loyalty to the Post was his painful decision to sell the paper, in 2013, to Bezos, who made his vast fortune as the founder of Amazon. The Graham family was hardly poor, but in the new media environment—and under the relentless demands of reporting quarterly earnings—they were forced, again and again, to make trims, at a time when investment was needed. Instead of continuing to cut and, inevitably, diminish the paper that he loved, Graham carried out a meticulous search for a new owner with the resources, the judgment, and the vision to help the Post navigate this new era. Bezos—the “ultimate disrupter,” as Fortune had called him a year earlier—seemed the right choice.

As a deputy to the late editorial-page editor Fred Hiatt, I had the chance to see the drama of a new ownership play out up close. In the summer and fall of 2016, as Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump battled for the Presidency, our editorial board, of which I was a member, was unsparing in its criticism of Trump. As the G.O.P. Convention concluded, in late July, Hiatt published an extra-long editorial that made it clear, even before Democrats held their Convention, that the paper could not support Trump.

“The real estate tycoon is uniquely unqualified to serve as president, in experience and temperament,” Hiatt wrote. “He is mounting a campaign of snarl and sneer, not substance. To the extent he has views, they are wrong in their diagnosis of America’s problems and dangerous in their proposed solutions. Mr. Trump’s politics of denigration and division could strain the bonds that have held a diverse nation together. His contempt for constitutional norms might reveal the nation’s two-century-old experiment in checks and balances to be more fragile than we knew.” That wasn’t the end of what we had to say. In September, 2016, we published a series of six editorials outlining “the clear and present danger of Donald Trump,” from climate change to the global economy to immigration.

We had every indication that Bezos shared this sense of alarm. Bezos and Hiatt held twice-monthly telephone calls, which I joined, along with the Post’s then publisher, Fred Ryan, and Hiatt’s other deputy, Jackson Diehl. These were not conversations in which the owner handed down instructions; they were more like dorm-room gab sessions, with a heavy dose of policy. We proffered morsels of Washington gossip and delivered our insights, such as they were, about politics and international affairs. Bezos talked about the need to find innovative ways to connect with readers—he mentioned something about an exploding watermelon that had gone viral on BuzzFeed, though I didn’t exactly follow how that applied to our work. When our humor columnist Alexandra Petri spoofed Samuel Beckett in “Waiting for Pivot: A GOP Tragicomedy,” featuring Vladimir Ryan and Estragon Priebus waiting for Trump’s shift to the center, Bezos suggested that we post a video dramatization. (Proving that immense wealth and sole ownership don’t always get you what you want, our video department balked.)

In my experience of that time, Bezos came off as charming, smart, and unpretentious. “Guys, this is always the most interesting meeting of my week,” he would often say, seeming to mean it. Or, “I know we’ve been going on for a while, but can I hold you for one more question?”—as if he weren’t the owner, and we weren’t at his beck and call.

Trump’s first election and Inauguration brought some inklings of trouble. Some sixty-three million voters had backed Trump, but even our conservative columnists—including George Will, Charles Krauthammer, and Michael Gerson—were highly critical of Trump. Bezos pressed us to find more writers from the heartland, who might understand Trump’s appeal. This was entirely appropriate. More unsettling was his expressed desire, at the start of the new Administration, to have the editorial page find something, anything, positive to say about Trump. During Trump’s first term, the Post’s executive editor was Martin Baron. As Baron relates in his book, “Collision of Power,” Bezos “urged showing support for Trump on whatever issues he could. . . . Whenever the Post editorial board’s view coincided with Trump’s, why not say so?” Hiatt, Baron wrote, “feared that Bezos was anxious to smooth things over with the new occupant of the White House.” During one pre-Inauguration phone call, Bezos seized on a line from Trump’s first post-election news conference—“I have great respect for the news and great respect for freedom of the press and all of that”—as a promising sign. This was an exceedingly charitable interpretation, given that, at the same event, Trump had refused to take a question from “fake news” CNN, called the BBC “another beauty,” and denounced BuzzFeed as a “failing pile of garbage,” and we suggested as much to Bezos.

Still, we tried to give Trump, where possible, the benefit of the doubt. One example was an editorial published on January 18, 2017, outlining “five policies Trump might get right.” It noted that, despite the newspaper’s endorsement of his opponent, Trump’s “election was legitimate, and his inauguration is inevitable. All of us have a duty to oppose Mr. Trump when he is wrong, but also to remain open to supporting him when he and the Republican-majority Congress make worthy proposals.” In the end, we didn’t find much to cheer about in Trump’s first term—and Bezos never pressured us to go easy on him.

Four years later, the editorial board endorsed Joe Biden for President, warning that “democracy is at risk, at home and around the world. The nation desperately needs a president who will respect its public servants; stand up for the rule of law; acknowledge Congress’s constitutional role; and work for the public good, not his private benefit.” There was no disagreement from the owner.

So much changed—and long before Bezos’s eleventh-hour decision to kill the newspaper’s endorsement of Kamala Harris in 2024. Hiatt died suddenly in December, 2021. He was replaced by David Shipley (full disclosure: I applied for the job and didn’t get it), who, as an executive editor of Bloomberg’s opinion coverage, had experience dealing with, and channelling the views of, a billionaire owner. To read the paper’s 2024 editorials on Trump and Biden, and then on Trump and Harris, is to experience a once passionate voice grown hesitant and muted. (I left the editorial board in September, 2023.) Granted, Democrats offered voters two far from perfect candidates, but, to paraphrase Biden, we’re not comparing them to the Almighty here.

Certainly, Trump was not spared from criticism; in fact, there was no doubt which candidate the editorial board preferred. Yet the shift in tone was unmistakable. You would not know from the 2024 editorials that just four years earlier we had called Trump “the worst president of modern times”—and that was before the January 6th insurrection at the Capitol. A September, 2024, editorial that purported to compare Trump and Harris on policy grounds concluded that “the substantive contrasts Ms. Harris draws with Mr. Trump generally make her look better. But should Americans settle?” Generally? Look at what Trump’s been doing since taking office—at his barrage of unconstitutional, small-minded, and cruel executive orders—and tell me that Harris was “generally” better.

It was becoming clear, as September gave way to October, that something was up with the endorsement. Those not in the know—which included almost all of us in the Opinions section, because the piece was unusually closely held—figured that the delay involved negotiating over tone and adjectives. Then, on October 25th, came the first of our self-inflicted wounds: the paper’s leadership announced that, in fact, we would not be issuing an endorsement in the 2024 Presidential race, and wouldn’t in future contests.

Lewis, the publisher and chief executive officer, cast this decision as “returning to our roots,” referring to our long-ago practice of not endorsing in Presidential contests. This was, to say the least, unconvincing. The modern Post—the post-Watergate Post—issued Presidential endorsements in every election but the dreary Michael Dukakis–George H. W. Bush matchup, of 1988, when the paper rigorously explained its reasoning for finding neither of the candidates worthy.

The more senior columnists—David Ignatius, Eugene Robinson, Karen Tumulty, Dana Milbank, and I—conferred about what to do. We drafted a statement, eventually signed by twenty-one columnists, calling the decision “a terrible mistake” and an “abandonment of the fundamental editorial convictions of the newspaper that we love.” I called my editor to say that I’d also be filing a column disagreeing with this decision. What I heard back was encouraging: the section editors welcome it, they’ll run it, they’ll hold space for you in print. And the column ran, with no resistance from editors.

“I have never been more disappointed in the newspaper than I am today,” I wrote. The owner has the right to shape editorial policy, I acknowledged, and there are reasons to eschew endorsements: they can cause headaches for the separate, news side of the paper. Moreover, Presidential endorsements are something of a vanity operation—unlike with more local contests, readers don’t need them to guide their votes. Choosing to abandon the practice would be a reasonable decision.

Still, I argued, “this is not the time to make such a shift. It is the time to speak out, as loudly and convincingly as possible, to make the case that we made in 2016 and again in 2020.” Since then, Trump had incited an insurrection that threatened the life of his own Vice-President, had refused to accept the reality of his 2020 loss and claimed he wouldn’t accept defeat in the 2024 contest, and had threatened to “go after” political enemies and “terminate” the Constitution. “What self-respecting news organization could abandon its entrenched practice of making presidential endorsements in the face of all this?” I asked.

The “kicker” wrote itself, and it is painful to read now: “Many friends and readers have reached out today, saying they planned to cancel their subscriptions or had already done so. I understand, and share, your anger. I think the best answer, for you and for me, may be embodied in this column: You are reading it, on the same platform, in the same newspaper, that has so gravely disappointed you.”

As many as three hundred thousand readers reportedly cancelled their subscriptions. Two of our non-staff columnists—Robert Kagan and Michele Norris—resigned. Should I have joined them? The paper had demonstrated that my columnist colleagues and I were free to write what we wanted. If Trump were elected, I reasoned, my voice and my expertise—we columnists are a grandiose lot—would count for something. In retrospect, you can say that this frog chose to remain in the simmering pot, but she thought hard about it.

Things got worse, in two connected ways—three if you count Trump’s election. After November 5th, Bezos joined his fellow tech billionaires in seeming to court Trump’s favor. “I’m actually very optimistic this time around,” Bezos said on December 4th, at the New York Times’ DealBook Summit. “He seems to have a lot of energy around reducing regulation. And my point of view, if I can help him do that, I’m going to help him.”

When his interviewer, Andrew Ross Sorkin, pressed Bezos about Trump’s depiction of the press as “the enemy,” Bezos said, “I’m gonna try to talk him out of that idea. I don’t think the press is the enemy and I don’t think, he’s also—you’ve probably grown in the last eight years. He has, too.” Trump, he continued, “is calmer than he was the first time and more confident, more settled.” This wasn’t the triumph of hope over experience; it was the elevation of willful self-delusion over all available evidence.

On December 12th, Amazon said that it would follow Meta’s lead and donate a million dollars to Trump’s Inauguration. On December 18th, Bezos and his fiancée, Lauren Sánchez, dined with Trump and Melania at Mar-a-Lago, joined by Elon Musk. “In this term, everybody wants to be my friend,” Trump observed. He had reason to think as much. On January 5th, Amazon announced that it had bought the rights to a documentary about Melania, co-produced by Melania herself. Puck’s Matthew Belloni reported that the streaming service was paying forty million dollars to license the film—reportedly the most Amazon had ever spent on a documentary, and almost three times the highest competing bid. The Wall Street Journal reported that Melania stood to pocket more than seventy per cent of that fee—and that, at the Mar-a-Lago dinner, Melania “regaled” Bezos and Sánchez with details about the project.

Amid all this, Ann Telnaes, the Post’s Pulitzer Prize-winning cartoonist, submitted a cartoon depicting Bezos and his fellow-billionaires on their knees before a statue of Trump. On January 3rd, Telnaes announced that she was quitting because the cartoon had been rejected. “There have been instances where sketches have been rejected or revisions requested, but never because of the point of view inherent in the cartoon’s commentary,” Telnaes wrote. “That’s a game changer . . . and dangerous for a free press.” As far as I can tell, the rejection didn’t happen at Bezos’s direction. Shipley, the editorial-page editor, made the call, on the unconvincing ground that the cartoon was duplicative—Eugene Robinson had written a column on the billionaires’ pilgrimages to Mar-a-Lago, and another one was in the works.

“Not every editorial judgment is a reflection of a malign force,” Shipley wrote in a statement. The “only bias” in the decision, he added, “was against repetition.” It is true that the section under Shipley’s guidance had tried to crack down on multiple columns making the same point. But the notion that a cartoon could not make a similar point was ludicrous. (In any event, there had been developments since Robinson’s column: the centerpiece of the Telnaes cartoon was a prostrate Mickey Mouse, reflecting Disney’s malodorous decision to settle Trump’s defamation lawsuit against ABC News by paying fifteen million dollars for his Presidential foundation and museum and a million dollars to cover his legal fees.) There is no doubt in my mind that, absent Bezos, the cartoon would have run unchallenged. The decision to kill it was an instance of obeying in advance.

This episode was far more concerning than the non-endorsement decision, because it wasn’t limited to the paper’s institutional editorial position—it implied that restrictions were coming for columnists, too. In hindsight—and, again, I thought about it at the time—maybe that should have been the moment I left.

Then came the Inauguration, with the spectacle of Bezos and his fellow-tycoons arrayed like so many trophies behind the triumphant new President. I tested the limits with a column about the “inauguration of the oligarchs.” The column decried the spectacle and named Bezos but, I have to confess, shied away from pointing out that a newspaper was among Bezos’s playthings. His presence on the inaugural platform conveyed a message of support for Trump that, I can say now, was inappropriate.

As it turned out, the vast majority of us at the paper had no idea what was happening behind the scenes as Shipley, Lewis, and Bezos debated a new vision for the Opinions section. That vision arrived in our inboxes at 9:31 A.M. on February 26th, with Bezos’s announcement of “a change coming to our opinion pages” and the news that Shipley was resigning.

“I offered David Shipley, whom I greatly admire, the opportunity to lead this new chapter. I suggested to him that if the answer wasn’t ‘hell yes,’ then it had to be ‘no,’ ” Bezos wrote. “After careful consideration, David decided to step away.”

The columnists were deeply wounded by the newly announced limits and what they portended. We had always been able to assure our readers that no one restricted what we could write. How could we credibly make that claim now? What was the meaning of “personal liberties and free markets?” Without further clarification, we were like dogs that had been fitted with shock collars but had no clue where the invisible fence was situated. Dana Milbank was the first to test the new regime, with a clever column that put every Trump action through a Bezosian lens. “If we as a newspaper, and we as a country, are to defend Bezos’s twin pillars, then we must redouble our fight against the single greatest threat to ‘personal liberties and free markets’ in the United States today: President Donald Trump,” he wrote.

Milbank’s column somehow passed muster and ran—even though that required the highly unusual step of it being submitted to the publisher for review. Eugene Robinson followed, with a subtle column on the new documentary about Katharine Graham; the column made no reference to Bezos, but its paeans to Graham’s courage in the face of Richard Nixon’s threats evoked an implicit comparison with the current owner and his relationship with Trump. Our media critic, Erik Wemple, was less fortunate. His straightforward column disagreeing with the Bezos announcement—I read it in our internal system, and found it perfectly reasonable—never ran.

And so I took the plunge. On a long flight to Washington, I opened my laptop. I knew what would likely happen before I typed a single word. I had spoken out forcefully against the decision to kill the endorsement. Censoring columnists was way worse. Having written then, how could I stay silent and live with myself now? Still, I hesitated. Since Trump’s Inauguration, I had been writing at a furious pace, assailing his blizzard of executive orders, his assaults on the rule of law, his dismantling of the Justice Department, which I had covered as a young reporter. Was speaking out on Bezos important enough to risk losing the platform that the Post provided?

I tried, as you will see if you read the column, to give the editors a way to get to yes. I made almost no mention of Bezos’s post-election efforts to cozy up to Trump. I did not question Bezos’s motives. The column was, if anything, meek to the point of embarrassing. But I thought that it was important to put my reasons for disagreement on the record—not only to be true to myself but to show that the newspaper could brook criticism and that columnists still enjoyed freedom of expression. Running it, I believed, would enhance the Post’s credibility, not undermine it.

Just before 1 P.M. on Monday, March 3rd, my editor sent the column to higher-ups for review. Under ordinary circumstances, it would have gone to the copy desk in a matter of hours. This time, silence ensued. Early Wednesday evening, some fifty hours after the column was first submitted, I received a call from Mary Duenwald, who had followed Shipley from Bloomberg to serve as a deputy. The verdict from Will Lewis, she said, was no. Pause here for a moment: I know of no other episode at the Washington Post, and I have checked with longtime employees at the paper, when a publisher has ordered a column killed.

According to Duenwald’s explanation, the column did not pass the “high bar” required for the Post to write about itself. It was “too speculative,” because we couldn’t know, until a new opinion editor was named, what the impact of the new direction would be. It could turn out that none of our columns would be affected by the Bezos plan. Duenwald said that my column on the endorsement had been accepted because it involved a clear-cut decision; the opinion-page policy was a work in progress.

None of this was any more convincing than the rationale for rejecting the Telnaes cartoon. At bottom, the “too speculative” excuse took our owner for a feckless fool, which he is most certainly not. He announced a change in direction, and we should take him at his word, not assume that it was meaningless, or that he would forget about the idea. And my point was not only about what columns would get through the filter, once installed; it was about maintaining the trust of our readers. I asked to speak with Lewis. He declined to see me, instructing an editor to inform me that there was no reason to meet, because his decision was final.

So, too, was mine. I submitted my letter of resignation on Monday, to Bezos and Lewis. “Will’s decision to not run the column that I wrote respectfully dissenting from Jeff’s edict—something that I have not experienced in almost two decades of column-writing—underscores that the traditional freedom of columnists to select the topics they wish to address and say what they think has been dangerously eroded,” I wrote. “I love the Post. It breaks my heart to conclude that I must leave.”

This was not the outcome I sought. I will always be rooting for the Post and its journalists. I hope, for the sake of my colleagues but even more for the good of readers, that Bezos’s plan for the Opinions section will turn out in practice to be more capacious and less stifling than feared. Even more, I hope that Bezos will hold to his commitment, and to his stalwart practice, during Trump’s first term, of not knuckling under to the President’s pressure campaign to interfere with news coverage. We have lost so much talent in the newsroom in the past few months as reporters and editors have defected to competitors—and we’re still publishing remarkable work. (I’ll never stop saying “we.”)

I wish we could return to the newspaper of a not so distant past. But that is not to be, and here is the unavoidable truth: the Washington Post I joined, the one I came to love, is not the Washington Post I left.

Here is the column that the Post would not run:

“The values of the Post do not need changing,” Jeff Bezos told employees when he bought the newspaper a dozen years ago. He echoed the words of the Post’s owner Eugene Meyer in 1935, emphasizing, “The paper’s duty will remain to its readers and not to the private interests of its owners.”

Agreed, and, at the risk of sounding naïve, I believe Bezos still agrees as well. But I must respectfully dissent—as I did when he decided just before the election to spike our endorsement in the Presidential race—from his newly announced vision for the Opinions section. The section will focus, Bezos said, on “personal liberties and free markets.” More ominously, he added, “viewpoints opposing those pillars will be left to be published by others.”

Bezos owns the Post, and this decree is within his prerogatives. An owner who meddles with news coverage, especially to further personal interests, is behaving unethically. Shaping opinion coverage is different, and less problematic. But narrowing the range of acceptable opinions is an unwise course, one that disserves and underestimates our readers.

This is my forty-first year at the Post. I’ve spent more than half of them now on the opinions side of what we think of as the church-state divide, as a writer of unsigned editorials, a columnist, and, for a six-year stretch during the Bezos years, a deputy editorial-page editor, overseeing the op-ed pages.

During that time, we had two fixed stars. First, an editorial page—the unsigned opinions that express the views of the newspaper—that was fiercely devoted to, yes, “personal liberties and free markets,” including the promotion of democracy at home and abroad. Second, an op-ed section—the signed opinion columns and other content—that embraced no orthodoxy. Instead, we consciously and assertively endeavored to present our readers with a range of views.