#Ise Torii

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

風日祈宮 伊勢神宮

12 notes

·

View notes

Video

20250214 Ise + Shima 2 by Bong Grit Via Flickr: 朝早めの時間だと参拝者も少なくて参道は静かです。 Photo taken at Naiku, Ise city, Mie pref.

#Forest#Bush#Tree#Trees#Nature#Plant#Green#Torii#Torii gate#Shrine's gate#Gate#Wood#Wooden#Morning#Ise Jingu#Jingu#Naiku#Inner shrine#Kotai Jingu#Shinto shrine#Shinto#Shrine#Amaterasu#Amaterasu Omikami#Amaterasu Sume Omikami#Ise#Mie#Japan#Nikon#Nikon Df

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

たまたま撮��た神がかり的な一枚

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

I needed to see this image to be able to see how big the rocks were. Or in this case, how small. I used to think the Torii gate was full-sized

The sacred Meoto Iwa (夫婦岩) or Husband & Wife Rocks off the coast of Ise, Mie Prefecture

Photo by the Asahi Shimbun

Image from "Shintō: The Sacred Art of Ancient Japan" edited by Victor Harris, published by the British Museum Press. 2001, page 16

69 notes

·

View notes

Text

Okay

So I already have a protection gohei from Sarutahiko-no-Ōkami.

The Gohei (Shide wand) brings the protective power and blessings of Sarutahiko no O Kami to your home, office, dojo, or dorm room. [...] Please place this Gohei on the household altar or hang it at the entrance of your home so that you may be inspired by the miraculous power of the great kami’s divine virtue. Use this Gohei to receive his protection, be free from illness, be blessed with good fortune, and be blessed with wealth. — Shin Mei Spiritual Center

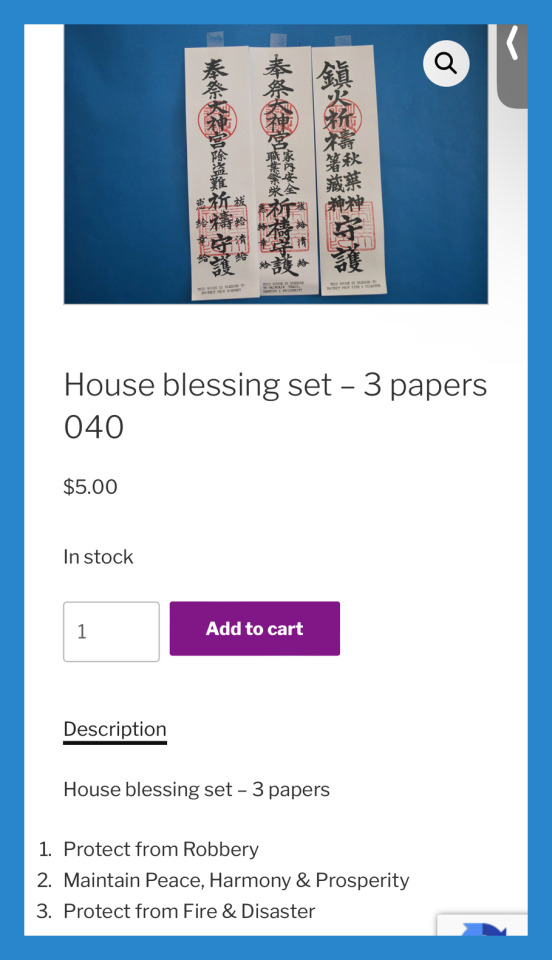

I wanted these three protection ofuda to be next to my miyagata in an ofuda stand

Protection from Robbery, Fire/Disaster, Peace. From Daijingu Temple of Hawaii an Amaterasu-Ōmikami shrine.

But from my ramblings earlier—link—they do not ship anywhere. I emailed to confirm. And unfortunately the person I know it Hawaii is no where near the shrine. And my sister's conclusion "I think the only solution is for you to go to Honolulu"

I found an Inari Shrine offering this

Which states

Middle 神流地球神社御守護 (Kannagara chikyu jinja gosyugo) | Kanna Earth Shrine Guardian — conveying the protective aura of Inari Sanza / Kannagara Okamitachi

Left 家内安全 (Kanai anzen) — Family protection and support.

Right 災難消滅 (Dainan syoumetsu) — Dispel / disappear misfortune.

as entryway ward/ amulet the Kirifuda invites in good fortune while repelling negative energies, other uses include any area with troubling energies, including but not limited to : compass directions that may be troublesome or locations with energy flow difficulties or over sleeping area in case of negative influences, patterns disturbing overnight. — Inari Earth Shrine

Though I can't place it by my door. Hence on Kamidana.

-

Once upon a time someone told me 'Inari faith' headed by Fushimi Inari Taisha should not be mixed with 'jinja shinto' headed by Ise Grand Shrine. That the Kamidana is different colors (red), that it requires Kitsune foxes and torii on the Kamidana.

But I feel like a protective amulet from Inari-Ōkami is not conflicting? Especially since my Ujigami ofuda from Hokubei Tsubaki Dai Jinja also includes the enshrined Ukanomitama-no-Kami... who is an Inari Ōkami

So I feel comfortable, while it doesn't specifically protect from fire (my worst fear, but that would fall under misfortune) it still feels lovely to have.

-

PS So happy my mom let me buy her an omamori for Mother's Day

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sean bienvenidos a una nueva publicación en la cual aclararemos las diferencias entre un templo y un santuario japonés dicho esto pónganse cómodos que empezamos. - Seguramente, todos hemos visto alguna vez en fotos templos y santuarios que están por todo el archipiélago nipón y más de una vez nos hemos preguntado: ¿Cuáles son las diferencias entre ellos? - Primero la palabra santuario ¿Qué significa?: Es el lugar en el que los japoneses adoran a todos los kamis por lo cual cada uno tiene el suyo propio, también cabe destacar que puede ser una montaña un lago ect.. Cuando buscamos esta palabra en español, hace referencia a un templo,entonces ¿Cuáles son las principales diferencias? la principal sería que los santuarios sintoístas, disponen de una puerta principal llamada torii a diferencia de los templos budistas, que disponen de una pagoda. Ejemplos de templos budistas por ciudades Templo de Kiyomizu-dera (Kioto) Templo Kinkakuji (Kioto) Templo Senso-ji (Tokio) Templo de Hokokuji (Kamakura) Templo Todai-ji (Nara) Templo de Sanjusangendo (Kioto - Santuarios japoneses por ciudades: Santuario de Ise – Ciudad de Ise Santuario Meiji – Tokio Santuario Itsukushima – Miyajima Santuario Sumiyoshi Taisha – Osaka Santuario Hie Jinja – Tokio Santuario Izumo – Ciudad de Izumo - Para aclarar las dudas, entre un santuario y un templo: También hay que tener en cuenta los distintos nombres y otras de las cosas que caracterizan un templo son las siguientes : Komainu, Temizuya o chōzuya, Salas principales, Amuletos,Komainu, Temizuya el honden y el haiden. En próximos capítulos podemos hablar de cada uno de ellos, aparte de seguir realizando publicaciones de historia, arqueología, geografía entre otros temas de japón os deseo un cordial saludo. - Welcome to a new publication in which we will clarify the differences between a temple and a Japanese sanctuary. That being said, make yourself comfortable and let's get started. - Surely, we have all seen temples and sanctuaries that are all over the Japanese archipelago in photos and more than once we have asked ourselves: What are the differences between them? - First, the word sanctuary What does it mean?: It is the place where the Japanese worship all the kamis, so each one has their own, it is also worth noting that it can be a mountain, a lake, etc. When we look for this word in Spanish, it refers to a temple, so what are the main differences? The main one would be that Shinto shrines have a main door called torii. unlike Buddhist temples, which have a pagoda. Examples of Buddhist temples by city Kiyomizu-dera Temple (Kyoto) Kinkakuji Temple (Kyoto) Senso-ji Temple (Tokyo) Hokokuji Temple (Kamakura) Todai-ji Temple (Nara) Sanjusangendo Temple (Kyoto) Shitennoji Temple (Osaka) - Japanese shrines by cities: Ise Shrine – Ise City Meiji Shrine – Miyajima Sumiyoshi Taisha Shrine – Osaka Fushimi Inari Shrine – Kyoto Hie Jinja Shrine – Tokyo Izumo Shrine – Izumo City - To clarify doubts, between a sanctuary and a temple: We must also take into account the different names and other things that characterize a temple are the following: Komainu, Temizuya or chōzuya, Main rooms, Amulets, Komainu, Temizuya the honden and the haiden. In future chapters we can talk about each of them, apart from continuing to publish publications on history, archaeology, geography, among other topics about Japan, I wish you a cordial greeting. - 寺院と日本の聖域の違いを明確にする新しい出版物へようこそ。そうは言っても、安心して始めましょう。 - 確かに、私たちは皆、日本列島各地にある寺院や聖域を写真で見たことがあり、それらの違いは何だろうかと自問したことが一度や二度ではありません。 - まず、聖域という言葉はどういう意味ですか?: それは日本人がすべての神を崇拝する場所であり、それぞれに独自の神があり、それが山や湖などであることも注目に値します。この単語はスペイン語で寺院を指しますが、主な違いは何でしょうか? 主なものは、神社には鳥居と呼ばれる表扉があることです。 塔のある仏教寺院とは異なります。 都市別の仏教寺院の例 清水寺(京都) 金閣寺(京都) 浅草寺(東京) 報国寺(鎌倉) 東大寺(奈良) 三十三間堂(京都) 四天王寺(大阪) - 都市別の日本の神社: 伊勢神宮 – 伊勢市 明治神宮 – 東京 厳島神社 – 宮島 住吉大社 – 大阪 伏見稲荷大社 – 京都 日枝神社 – 東京 出雲大社 – 出雲市 - 聖域と寺院の間の疑問を解消するには、次のような名前や寺院を特徴付けるその他のものについても考慮する必要があります: 狛犬、手水舎または手水舎、主室、お守り、狛犬、本殿と拝殿。 今後の章では、歴史、考古学、地理、その他日本に関するトピックに関する出版物の発行を続けることに加えて、それぞれのテーマについてお話します。心からご挨拶を申し上げます。

#清水寺#京都#金閣寺#伊勢神宮#伊勢市#日枝神社#東京#出雲神社#出雲市#寺院#神社#日本#歴史#ユネスコ#Kiyomizuderatemple#Kyoto#KinkakujiTemple#IseShrine#IseCity#HiJinjaShrine#Tokyo#IzumoShrine#IzumoCity#temple#Shrine#japan#history#unesco

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chapter 3: The History of Hie Shrine

Festivals and Fights

The one possibility for shrines like Hie to pursue their own distinctive path amidst the uniformity of Meiji was the annual festival… end of 1872, the Meiji government legislated a distinction between shrine rites. ㊸ “State rites” (kansai)… funded by the government… but “private rites” (shisai) would receive neither funding nor patronage… in the case of Hie’s Sannō festival… government funded the offerings made to Ōyamakui on the morning of the third festival day… the rest… were all redfined now as “private…” lest “private” be interpreted as a license for merrymaking… in 1873 ordered mikoshi processions everywhere to exercise restraint and avoid “being rough, bumping into houses or impeding passersby” (Miyachi 1988: 457).

—Page 119

㊸ From the end notes: “This applied only to shrines which, like Hie, were underwritten by government in any way at all. From the early 1970s, only some 139 major shrines out of a national network numbering well over 100,000 were so funded. Ise and Yasukuni, the new shrine for the war dead, were treated as special cases and never wanted for funds.

The discovery and enshrinement of the kami Ōyamakui… displaced the pre-Meiji interpretation… For [Shōgenji] Yukimaru, the descent of the mountain by the two mikoshi-borne kami… the departure of the seven mikoshi from the Ōmiya compound, were… joyous moments marking the entrance of the kami into the human world… akin to Amaterasu’s stepping out of the heavenly cave, restoring light to the word (ST Hie: 161-85). The passage of the seven mikoshi under the three torii gates of Hie…represented the essential oneness of the kami and the buddhas (ST Hie: 315-78)…. Never doubted the truth of Tendai claims about the Buddhist nature of all kami.

…modern Shinto-style Sannō festival yielded a different order of interpretation… “the festival, which is of the greatest antiquity, serves to recreate the birth and subsequent ascent to heaven of [the divine child] Wakamiya.”

—Pages 119-120

The Shrine and its Festival in the Twentieth Century

…The first two decades of the twentieth century saw Hie and other shrines acquire a status in national life higher than at any time since the Restoration… In 1915… priests obtained Home Ministry permission and restored the triangular structure to the top of the main torii gates… in 1928… the Home Ministry ordered that Hie end its ritual subordination of Ōnamuchi to Ōyamakui. The kami were to be regarded as equal, and their equality was to be manifest in new referents for their shrines: Ōyamakui’s shrine was to be known as Nishi Hongū, and Ōnamuchi’s as Higashi Hongū… Western and Eastern Main Shrines respectively. An Imperial emissary attended the Sannō festival in 1929 to present his own offerings to Ōnamuchi, and thus mark the restoration of that Kami’s status. If there was after all no status distinction between the two kami, there could no longer be any justification for the reordering of Hie’s ritual space which Nishikawa had effected back in the 1870s… This is the situation that prevails today: Hie is imagined as comprising western and eastern compounds, each dominated by two great kami whose divine virtues are in every measure equal.

—Pages 123-124

…One striking development of these years was a thawing in the relationship between the shrine priests and the ones of Mount Hiei. In 1837… celebrated the 1,550th anniversary of Saichō’s founding of the Enryakuji temple…. Monk called Umetani, descended the mountain and gave thanks to Ōnamuchi after the festival of that year was over… extraordinary moment… first time in 70 years since the Restoration that a Buddhist monk had prayed before the Hie kami… 1938 a party of monks attended the Sannō festival… received a ritual purification… made offerings to Ōnamuchi before paying their respects to each of the Hie kami in turn… mark the establishment of a new “civility” in shrine-temple relations. It is a civility that endures to the present day, for Tendai monks now participate every year in the Sannō festival in April, and they return to the shrine on May 26 to recite the Lotus sutra before the kami Ōnamuchi.

—Pages 124-125

The Challenge of the Postwar Years

…The Occupation dismantled “state Shinto…” Severing the links between the state and Shinto shrines like Hie was essential to this task… 1947 Constitution duly accommodated….separation of state and religion… vast majority of shrines, Hie sough security amid the new uncertainties by singing up to the National Association of Shrines (NAS)… under the name of Hiyoshi Tanisha, Hiyoshi being an alternative reading of the characters “Hie”; Tanisha or “great shrine” in deference to its elite status in imperial Japan. NAS was launched by prewar Shinto intellectuals and bureaucrats, precisely to prevent the demise of shrines without which Shinto had no meaning.

—Page 125

These two men [Takenami & Murata]] detested one another, largely it seems because they had graduated from rival Shinto universities. 55

–Page 126 55 From the end notes: The two (rival) universities that train men and women for the Shinto priesthood are Kokugakuin in Tokyo and Kōgakkan in Ise. Shrines have a tendency to recruit from either one of these two universities, rather than mixing candidates from both.

….What blocked the “divorce” [Hiyoshi Taisha leaving NAS] was not the prefecture, but NAS’s swift dispatch of a replacement for Sugimura, as well as a campaign by Hiyoshi parishioners… petititioners accused Sugimura of destroying hundreds of trees in protected woodland… discriminating against Hagiyama villagers [historically a burakumin region]. Sugimura was dismissed… but this was not the end of the matter. Seven priests resigned in protest in 1989 at further NAS interference in shrine personnel matters. In the 1990s, tensions of a quite different sort surfaced when a junior priest set upon the chief priest with a metal pipe. At the start of the twenty-first century, harmony has been restored to the shrine and the shrine’s relationship to NAS, or so it seems.

—Page 127

I’m mostly floored at that metal pipe comment, the worst part is he doesn’t expand on it… like WHAT DO YOU MEAN???? THEy ATTACKED THEM WITH A METAL PIPE????

Priests themselves play a vital role in generating income… through their performance of specially commissioned rites… For example… requesting prayers and offerings… for the bestowal of three such “benefits” — family health, safe birth and exam success, say — will pay 30,000 yen. 57 Fees for Shinto wedding rites start at 50,000 yen while ground-breaking rites and assorted purifications can be as much as 70,000 yen a time.

—Pages 128-129

57 From the End Notes: “At the time of writing, 10,000 yen is approximately $US 105.

The costs nowadays is: 30,000 yen ≈ $US199, 50,000 yen ≈ $US332, and 70,000 yen ≈$US465

And with that I finish chapter 3 finally! The next chapter discusses the Ise Shrines, so look forward to that!

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

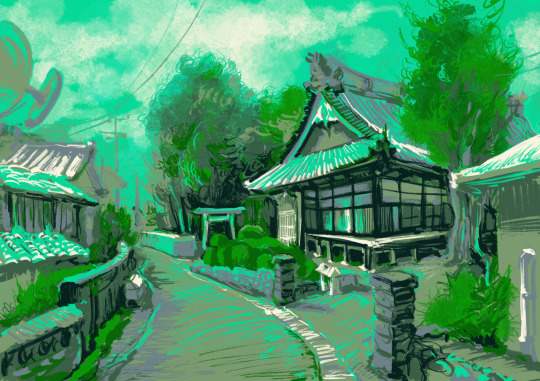

You know what — that torii gate seen in the distance was a completely unexpected catch! 😳 And I guess that is precisely why I'm liking the setting for this entire event so much — you traverse the street views along the maps at a seemingly complete random, and you find absolutely wondrous gems in decidedly non-tourist neighbourhoods. And ain't that precious in the very treasure-hunting way❤️ Continuing our travels with going to Ise, Mie, with palette №7. Painted in Procreate for the #japanuary art event 🗾

#japanuary#procreate#environment#street view#teal#teal green#green#architecture#street#digital study#traditional architecture

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

My Trip to Japan! ⛩️ Part 3

16.12

We had breakfast as soon as service started at 6:30, and then went to take the Shinkansen to Kyoto. The trip lasted just under an hour, and we arrived at 8:30. It was an adventure to get out. It would take us a day and a half to figure out the right way to move around the gigantic Kyoto station without getting trapped like a rat in a maze. We left the suitcases at the hotel, conveniently located just opposite the station, and went straight to Kinkaku-ji, the temple of the Golden Pavillion. The titlepavillion is one of several that make up the temple, though none as spectacular. The gardens were a delight. We had matcha tea at the temple's tea house, with a very tasty sweet bearing the pavillion’s outline and a touch of gold leaf.

We continued to the next temple, Ryō-An-ji. I liked this one a lot; it has a large stone Zen garden that invites contemplation... until the school outing arrives and misaligns all your chakras. On the way out, I bought a beautiful maiko doll for my niece, and we had a butaman, a very fluffy bread ball filled with pork. Very tasty.

Next on the itinerary was Ninna-ji, with an impressive monumental gate and a cherry blossom promenade that must be a dream during hanami season. Ninna-ji is an extensive complex, with many pavilions and a five-story pagoda. It was already 1 pm so we took a cute vintage train to Arashiyama, where we had some delicious sobaforlunch, looked at shops, and peeked at the Katsura River before attacking the fourth temple of the day, UNESCO World Heritage Site like the other 3: Tenryū-ji. This was the one that caught my attention the least (or maybe I was already saturated), but next to it ther’s the bamboo forest. You don't enter the forest proper, which is fenced, but walk through a pathway opened between the canes. Still, the height, greenery, and coverage of the bamboo canopy are impressive. You could hear the crackling of the canes hitting each other.

On the way back to the train, we happened to pass by a Shinto shrine in the middle of the bamboo forest, Nonomiya jinja, beautiful in its simplicity. Imperial princesses came here to purify themselves for at least a year before going to the Ise Shrine to ervve there on behalf of the emperor. Even if the custom ended in the 14th century, Nonomiya shrine still enjoys the favor of the imperial family.

In the evening we strolled a bit through the picturesque Gion district at night, had dinner, and went to bed for the next early rising.

17.12.

We got up at six sharp to go to the world-famous Fushimi Inari-taisha, the “shrine of the thousand torii” (ritual gates). We missed the train we wanted to take, lost in the mega-station, but we still arrived in time to start well before the hordes of visitors arrived. Even before entering, I witnessed something that gave a hint of how special this place is: while we were have breakfast in front of the konbini opposite the main entrance, a taxi stopped, the driver got out, prayed facing the temple right there on the tarmac, and continued his route.

The shrine was founded in the 8th century, dedicated, like the mountain where it sits, to Inari, the Shinto deity of rice, agriculture, and business, whose messenger animal is the fox. Therefore, fox-shaped statuettes are omnipresent on the altars spread all about the mountain. We went in, toured the different halls, and started the climb up Mount Inari along the torii-lined path. These gates are erected as votive offerings; the large ones, like the ones along the path, can cost as much as a luxury car, so they usually come from companies, but many minor shrines hold small, smaller, tiny, keychain-sized torii gates. Throughout the mountain, there are literally thousands of shrines: new and old, luxurious or very humble, alone or in groups, next to the path or hidden in the forest, pristine or claimed by nature.

Regardless of each person’s beliefs, Fushimi Inari has more than earned its sacred mountain status. Its atmosphere is tremendously spiritual. Even as I write this I get emotional, as I recall the overwhelming feeling that gripped me most of the way, despite the growing number of people appearing as the day progressed.

After leaving the shrine, we ate some takoyaki on the go and went to the center, to Nishiki Market, a covered street with very nice shops, especially food ones. I stopped at one which had all kinds of beautiful things, had my loot, and when I got to the cash point, the old lady took all her time to perfectly wrap the humble set of Hina dolls that I had bought. Position, bag, box, bag… I legit felt like Alan Rickman in Love Actually when Mr. Bean wraps the gift for his lover. Three times I told her she didn’t need to peel the price tags, as everything was for myself. Forget it, the price tag must go. We ate some more takoyaki to complete lunch at a place that only sells that. The basic ones were ¥280 (€1.90) for 6. In Europe, they charge you €5 for 4 balls. After eating, we went to Ginkaku-ji, the Silver Pavilion, with beautiful gardens and not as crowded as the golden one (spoiler: it's not covered in silver. That was the idea, but it never materialized).

We went down a little street that borders a canal called "The Philosopher's Path". A very bucolic and pleasant stroll, with a lot of green, traditional houses and hardly any shops, just art galleries or craft workshops. The last temple of the day was Eikan-do. Larger than we anticipated, it’s set within lush gardens and is beautiful: its many pavillions include a pagoda and a curved staircase nicknamed "sleeping dragon." Next to these stairs stands the three-needle pine, whose needles grow in groups of three, not two. It’s said to symbolize the virtues of wisdom, mercy, and sincerity. And that if you get a pine needle like that, you will be blessed with all three. Unfortunately, with everything being so clean, there was none within my reach.

⬆️ I haven't talked much about shopping so far, because the truth is there was hardly any AoT merchandise anywhere. These on the picture above are the only items they had at the Kyoto Animate store: One (1) chibi Levi clearfile; random manga volumes; One (1) Ereh acrylic stand and One (1) Levi one but it was teen Levi, not looking hot; and a "surprise" box with some chibi stuff but I'm certainly NOT spending 880¥ in a surprise. That's it. Neither Donki nor the discount place opposite had jackshit.

We had dinner on the 11th floor of the train station. Kyoto Station's building is a monster of engineering; the north hall rises ten floors above street level and includes a monumental staircase with LED colors on the risers that play with lights and even reproduce entire videos in full color (we saw the trailer for the latest Disney movie); on that side, there’s a huge department store, of which the last two floors are food courts: the 10th floor is only ramen restaurants, and the 11th floor has a bit of everything. We had beef tongue, a favourite of mine. After dinner, we went to the Sky Gallery, a walkway emerging from the 10th floor, with panoramic views of the station and the city.

18.12.

We woke up early and had breakfast at the hotel buffet, supposedly "western style," which turned out to be a hit-and-miss, not so much because of the Japanese version of what you can find at a buffet in Europe or the US, but because many of those dishes were cold, when they’re eaten warm in the West.

We started the day at Kiyomizu-dera, very spacious, with a clarity inside the temple that I hadn't seen in other Buddhist shrines. The impressive views over the city from its balcony supported by a structure of 13-meter-high wooden pillars are noteworthy. We walked down, looking at shops in Gion (there was a Ghibli shop here too!) and then we looked for an early lunch, as we had booked a kimono tea ceremony at one.

The buildig where the tea house operates is a registered cultural property. They dressed me in a kimono for me: an underrobe, tied with a ribbon (which straightens your back), the kimono itself, tied wit another ribbon, a plate to hold the obi (sash) in place, and the obi. They did my hair, and I proceeded to the salon, where Husband was already waiting for me looking like a full-fledged samurai. We were in a group of 8: us, an Australian couple about our age, and an Asian-American family of dad, mom, and two teenage children. Luckily, everyone was motivated and respectful of the place and the ritual.

After the hostess showed the entire process, she taught us how to whisk the matcha, and we enjoyed our tea (the traditional way is that everyone takes turns drinking from the same cup, but since the pandemic, each one gets their own bowl). Previously, we tasted sweets. One of them was a kind of dumpling filled with anko that blew my mind. It's called yatsuhashi and is a Kyoto specialty. The hostess wrote the name on a piece of paper for me and everything, but... My joy was short-lived, as when I went to buy it, the expiration date was quite short, so I could only got a small package to eat as soon as we returned home. Once the ceremony was over, we took photos at will in the house garden before returning the kimono.

In the afternoon we went to Nijo Castle, with impressive paintings on the door panels and exquisite marquetry on the lintels and ceilings. The historical significance of this castle is enormous, as it was the place wher the Tokugawa shogunate, better known as the Edo era, both began and ended. After the castle and more walking around the city centre, we had dinner and dragged ourselves back to the hotel, exhausted, and prepared everything to go to Nara the next day.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

🇯🇵⛩️Japan day 9 - last day of the road trip

Today we visited Ise, birthplace of Shintoism and home of Japan's most important shrine to Amaterasu-Omikami, the sun goddess who gave birth to the Imperial line.

⛩️Ise-Jingu is an immense shrine spanning the entire region, and containing 125 small shrines. The most important one is Naiku, the one where Amaterasu-Omikami is enshrined. Historically the high priests and priestesses of the shrine belonged to the imperial line, and the current high priestess is the daughter of retired emperor Akihito. The entire shrine (like, the main buildings, torii, etc, the whole shebang) is rebuilt anew every twenty years; the operation takes nine years and involves hundreds of rituals.

Ise shrine has been an important place of pilgrimage since the Edo era. The traditional route is to first purify yourself at Futamiokitama shrine, home of the famous Meoto Iwa "married stones", where young women pray for an auspicious marriage. The rocks represent Izanagi and Izanami, the original gods and parents of Amaterasu & co. The enshrined kami, Sarutahiko Okami, has frogs for their messenger animal, and there are frog statues and frog-decorated merch to buy. I nearly bought a tadpole-shaped omamori (might go back tomorrow for it).

Then you visit Geku shrine, dedicated to Toyouke Ohime. She is the goddess of food, clothes and homes. She was summoned and enshrined in Ise after an emperor had a vision of Amaterasu basically saying "I love it here but there's no food, bring my pal over so she can cook for me".

And lastly, you visit Naiku shrine, home of Amaterasu the sun goddess, protector of Japan. You can even ourify yourself djrectmy in the river rather than in a temizuya.

The shrines themselves were a little underwhelming, especially when compared with the other shrines I've seen so far. All of the buildings were made of plain wood, which is logical when you account for the fact that they're rebuilt every 20 years. You also cant see the atars, which are hidden behind walls or cloths, and there are no statues.

On the other hand, plain wooden buildings shaped like rice granaries in the middle of a forest /does/ bring you closer to nature, which is the origin of shintoism (which is at heart an animist belief). All in all, it was a important place to cross off the bucket list.

Also, tonight I can sleep on a real mattress for the first time in 10 days 🥳 And tomorrow we head back to Tokyo.

14 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Sanctuaire d'Ise

Le Grand sanctuaire d'Ise ou Ise Jingu, situé au cœur d'une forêt sacrée dans la préfecture de Mie au Japon, est le sanctuaire shintoïste le plus important du pays. Il est dédié à la déesse du soleil Amaterasu et un sanctuaire séparé est consacré à Toyouke, la déesse de la nourriture. Construit pour la première fois en l'an 4 avant notre ère, les structures actuelles sont basées sur les bâtiments érigés au 7e siècle de notre ère. Fait unique, 16 des 125 bâtiments de ce complexe tentaculaire, ainsi que le pont Uju et la porte torii , sont reconstruits exactement tous les 20 ans, la dernière fois en 2013. Ise Jingu est le sanctuaire ancestral des empereurs du Japon.

Lire la suite...

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

20240209 Ise+Futami 3 by BONGURI 何度訪れても特別な場所。 @Ise Grand shrine, Ise city, Mie pref.(三重県伊勢市 皇大神宮)

#mainsanctuary#shougu#stonesteps#sekkai#toriigate#torii#shrinesgate#wood#tree#trees#shintoshrine#shinto#shrine#isegrandshrine#kotaijingu#isejingu#naiku#amaterasimasusumeomikami#amaterasu#ise#mie#japan#nikon#nikondf#cosna#cosinavoigtländerultron40mmf2sl2naspherical

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Torii Kapısı:

Torii (toh-ree) gate (Tori kapısı) dinsel anlamı olan bir geçit. Bu dünya ile ruh dünyasını birbirinden ayırdığı varsayılan bir kapıdır.

Birçok varyasyona sahip olan torii, karakteristik olarak, her iki taraftaki direklerin ötesine uzanan bir dikdörtgen ve birincisinden daha kısa bir ikinci kemerin iki silindirik dik direğin üstüne yerleştirilmesiyle oluşur. Genellikle parlak kırmızı boyalı torii, tapınağın kutsal alanı ve sıradan alan arasındaki sınırı belirler. Torii ayrıca bir dağ ya da kaya gibi diğer kutsal noktaları da tanımlamaktadır. Farklı bölgelerdeki yerel inanışa göre değişik kutsal ruhları simgelemek üzere birçok farklı şekilde ve renkte karşımıza çıkabiliyor.

Şintoizm inanışında, şinto mabetlerinin girişindeki bu kapıdan geçtikten sonra ruhların sizin ettiğiniz duaları duyduğuna inanıyor Japonlar. Bu ruhlar onların inanışına göre bizdeki Allah veya ruh betimlemesinden biraz farklı kutsal ruh/ruhlar demek sanırım daha doğru olur.

Büyük şinto tapınaklarında birden fazla torii bulunuyor. Kırmızı torii mabete ana girişi simgelerken daha içerilerde kullanılan taştan yapılma bir torii ise mabetin kalbine (esas ritüel alanına) geldiğinizi belirtiyor. Kırmızı yerine bazen başka anlamları yüklemek için siyah veya renksiz (boyasız) toriiler de kullanılıyor.

İnari inanışının mabetlerinde ise biraz farklı olarak birçok (bazen yüzlerce) torii kapısından oluşan bir tünel kullanılıyor. Aslında bu torii kapılarının her birisi kutsal ruhlara minettarlık göstergesi olarak insanların tapınağa bağışlamış olduğu bir kapı ve bu bağışlanan kapılar arka arkaya dizilmek suretiyle bir tünel haline geliyor. Sayı ne kadar fazla ise o inanışın o kadar kuvvetlendiğine inanılıyor.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Exploring Japan's Spiritual Gateways and Luxurious Wellness Resorts

Introduction Japan, a land where ancient traditions blend seamlessly with modern innovations, offers visitors a range of unique experiences. Whether you're looking to explore spiritual gateways or indulge in serene wellness retreats, Japan's rich cultural heritage and natural beauty provide the perfect backdrop for both adventure and relaxation. 1. The Spiritual Gateways of Japan Japan is home to numerous Torii gates and spiritual landmarks that connect visitors to its ancient traditions, making these gateways essential stops on any trip to Japan. Fushimi Inari Taisha, Kyoto One of Japan's most iconic landmarks, the Fushimi Inari Shrine is famous for its thousands of vermilion Torii gates that create pathways leading up Mount Inari. Visitors can walk through these gates, offering prayers for prosperity and protection. - Why It’s Special: The Torii gates represent the transition from the mundane to the sacred. - Activities: Take a hike up the mountain, passing by small shrines, and enjoy panoramic views of Kyoto. Meiji Shrine, Tokyo Nestled in a forest within the bustling city of Tokyo, Meiji Shrine offers a tranquil escape. The massive wooden Torii gate at the entrance is one of Japan's largest and symbolizes purification. - Why It’s Special: A peaceful sanctuary in the heart of one of the world’s busiest cities. - Activities: Participate in traditional rituals, write prayers on Ema (wooden plaques), and visit during festivals to witness cultural performances. Itsukushima Shrine, Miyajima Famous for its "floating" Torii gate, Itsukushima Shrine on Miyajima Island is a UNESCO World Heritage site and one of Japan's most scenic spots. - Why It’s Special: The gate appears to float on water during high tide, creating a magical atmosphere. - Activities: Explore the shrine, hike up Mount Misen, and enjoy the island’s natural beauty. 2. Japan's Luxurious Wellness Resorts Japan is also a top destination for wellness retreats that focus on relaxation, rejuvenation, and a connection with nature. From luxurious onsen resorts to modern wellness centers, the country has something for everyone. Hakone Onsen, Kanagawa Prefecture Just a short trip from Tokyo, Hakone is known for its hot springs and stunning views of Mount Fuji. This popular wellness destination offers a variety of traditional onsen (hot spring) resorts. - Why It’s Special: Hot springs with views of Mount Fuji create a perfect balance between nature and luxury. - Activities: Soak in mineral-rich waters, visit the Hakone Open-Air Museum, and take a cruise on Lake Ashi. Beppu Onsen, Oita Prefecture Located on Japan’s southern island of Kyushu, Beppu is one of the country's most famous hot spring resorts, offering eight distinct geothermal baths known as the “Hells of Beppu.” - Why It’s Special: Unique onsen experiences like mud baths, sand baths, and hot spring steams. - Activities: Try the various hot spring baths, visit the Beppu Hells, and enjoy steam-cooked local cuisine. Kinosaki Onsen, Hyogo Prefecture Kinosaki Onsen is a charming hot spring town where visitors can enjoy the traditional experience of hopping between different onsen. - Why It’s Special: A picturesque town with seven public bathhouses, offering a variety of bathing styles and therapeutic benefits. - Activities: Rent a yukata (traditional robe) and stroll along the willow-lined streets as you visit the town’s onsen. Amanemu, Ise-Shima National Park For those seeking a luxurious, modern wellness experience, Amanemu is a five-star resort that incorporates traditional Japanese wellness philosophies with contemporary luxury. - Why It’s Special: This serene retreat offers onsen baths, yoga, and spa treatments surrounded by nature in Ise-Shima National Park. - Activities: Indulge in spa treatments, soak in private onsen, and explore the nearby Ise Grand Shrine. 3. Connecting Tradition with Wellness The concept of wellness in Japan is deeply rooted in its ancient traditions. Whether you’re meditating in a Zen garden, practicing mindfulness, or soaking in hot springs, Japan’s wellness philosophy emphasizes the balance between mind, body, and spirit. - Traditional Practices: Japanese wellness retreats often incorporate practices like tea ceremonies, calligraphy, and nature walks. - Healing through Nature: Many resorts are set in scenic locations, emphasizing the healing power of nature through forest bathing and water therapies. Conclusion: Japan's Gateways to Wellness Whether you are walking through the sacred gates of ancient shrines or unwinding in luxurious wellness resorts, Japan offers a perfect blend of spiritual and physical rejuvenation. Explore the unique Torii gates that have stood the test of time or indulge in the serene atmospheres of Japan’s finest onsen. Whichever path you choose, Japan’s spiritual and wellness experiences promise to leave you feeling refreshed and inspired. Read the full article

#CulturalExperiences#culturalimmersion#ForestBathing#FushimiInari#HotSprings#ItsukushimaShrine#Japan#Japaneseheritage#luxuryhotels#MeijiShrine#mind-bodybalance#rejuvenation#sceniclandscapes#spiritualgateways#teaceremonies#traditionalpractices#wellnessphilosophy#wellnessresorts#yogaretreats

0 notes

Photo

Japanese Antique Vintage Iron Steel Mask Signed Japan Tengu God Deity Ghost

Vintage-Antique appears to be circa 1940s - 1950s

Signed

Cast Iron

Well cast with fine details.

Size: 5.1 inch (13 cm) × 4.9 inch (12.5 cm)

Tengu

39 languages

Article

Talk

Read

Edit

View history

Tools

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Part of a series onJapanese mythology and folkloreMythic texts

Fudoki

Kogo Shūi

Kojiki

Konjaku Monogatarishū

Kujiki

Nihon Ryōiki

Nihon Shoki

Divinities

Amaterasu

Ame-no-Uzume

Inari

Izanagi

Izanami

Kami

Myōjin

Seven Lucky Gods

Susanoo

Tsukuyomi

Legendary creatures and urban legends

Kitsune

Oni

Onryō

Tengu

Yōkai

Yūrei

Mythical and sacred locations

Izumo

Jigoku

Mount Fuji

Mount Hiei

Ryūgū-jō

Takamagahara

Yomi

Sacred objects

Amenonuhoko

Kusanagi

Tonbogiri

Three Sacred Treasures

Shintō and Buddhism

Bon Festival

Ema

Setsubun

Torii

Buddhist temples

Shinto shrines

v

t

e

Tengu (/ˈtɛŋɡuː/ TENG-goo; Japanese: 天狗, pronounced [teŋɡɯ], lit. 'Heavenly Dog') are a type of legendary creature found in Shinto belief. They are considered a type of yōkai (supernatural beings) or Shinto kami (gods or spirits).[1] The Tengu were originally thought to take the forms of birds of prey and a monkey deity, and they were traditionally depicted with human, monkey, and avian characteristics. Sarutahiko Ōkami is considered to be the original model of Konoha-Tengu (a supernatural creature with a red face and long nose), which today is widely considered the Tengu's defining characteristic in the popular imagination. He is the Shinto monkey deity who is said to shed light on Heaven and Earth. Some experts theorize that Sarutahiko was a sun god worshiped in the Ise region prior to the popularization of Amaterasu.

Buddhism long held that the Tengu were disruptive demons and harbingers of war. Their image gradually softened, however, into one of protective, if still dangerous, spirits of the mountains and forests. Tengu are associated with the ascetic practice of Shugendō, and they are usually depicted in the garb of its followers, the yamabushi.[2]

Image

[edit]

Kobayakawa Takakage debating with the tengu of Mount Hiko, by Yoshitoshi. The tengu's nose protrudes just enough to differentiate him from an ordinary yamabushi.

The tengu in art appears in a variety of shapes. It usually falls somewhere in between a large, monstrous bird and a wholly anthropomorphized being, often with a red face or an unusually large or long nose. Early depictions of tengu show them as kite-like beings who can take a human-like form, often retaining avian wings, heads, or beaks. The tengu's long nose seems to have been conceived in the 14th century, likely as a humanization of the original bird's bill.[3] This feature allies them with the Sarutahiko Ōkami, who is described in the 720 CE text the Nihon Shoki with a similar nose measuring seven hand-spans in length.[4] In village festivals, the two figures are often portrayed with identical red phallic-nosed mask designs.[5]

Some of the earliest representations of tengu appear in Japanese picture scrolls, such as the Tenguzōshi Emaki (天狗草子絵巻), painted c. 1296, which parodies high-ranking priests by endowing them with the hawk-like beaks of tengu demons.[6]

Tengu are often pictured as taking the shape of some sort of priest. Beginning in the 13th century, tengu came to be associated in particular with yamabushi, the mountain ascetics who practice Shugendō.[7] The association soon found its way into Japanese art, where tengu are most frequently depicted in the yamabushi's unique costume, which includes a distinctive headwear called the tokin and a pompom sash (結袈裟, yuigesa).[8] Due to their priestly aesthetic, they are often shown wielding the khakkhara, a distinct staff used by Buddhist monks, called a shakujō in Japanese.[citation needed]

Tengu are commonly depicted holding a magical feather fan (羽団扇, hauchiwa). According to legend, tengu taught Minamoto no Yoshitsune to fight with the "war-fan" and "the sword".[9] In folk tales, these fans sometimes can grow or shrink a person's nose, but usually, they have attributed the power to stir up great winds. Various other strange accessories may be associated with tengu, such as a type of tall, one-toothed geta sandal often called tengu-geta.[10]

Origins

[edit]

Tengu as a kite-like monster, from Toriyama Sekien's Gazu Hyakki Yakō. Text: 天狗/てんぐ (tengu)

The term tengu and the characters used to write it are borrowed from the name of a fierce demon from Chinese folklore called tiāngǒu though this still has to be confirmed. Chinese literature assigns this creature a variety of descriptions, but most often it is a fierce and anthropophagous canine monster that resembles a shooting star or comet. It makes a noise like thunder and brings war wherever it falls. One account from the Shù Yì Jì (述異記, "A Collection of Bizarre Stories"), written in 1791, describes a dog-like tiāngǒu with a sharp beak and an upright posture, but usually tiāngǒu bear little resemblance to their Japanese counterparts.[11]

The 23rd chapter of the Nihon Shoki, written in 720, is generally held to contain the first recorded mention of tengu in Japan. In this account a large shooting star appears and is identified by a Buddhist priest as a "heavenly dog", and much like the tiāngǒu of China, the star precedes a military uprising. "9th year, Spring, and month, 23rd day. A great star floated from East to West, and there was a noise like that of thunder. The people of that day said that it was the sound of the falling star. Others said that it was earth-thunder. Hereupon the Buddhist Priest Bin said:—"It is not the falling star, but the Celestial Dog, the sound of whose barking is like thunder.". When it appeared, there was famine".—(Nihon Shoki) Although the Chinese characters for tengu are used in the text, accompanying phonetic furigana characters give the reading as amatsukitsune (heavenly fox). M. W. de Visser speculated that the early Japanese meaning for the characters used to write Tengu may represent a conglomeration of two Chinese spirits: the tiāngǒu and the fox spirits called huli jing before the nuances of meaning were expanded to include local Japanese kami, therefore the true Tengu in appearance.[12]

Some Japanese scholars have speculated that the tengu's image derives from that of the Hindu eagle deity Garuda, who was pluralized in Buddhist scripture as one of the major races of non-human beings. Like the tengu, the garuda are often portrayed in a human-like form with wings and a bird's beak. The name tengu seems to be written in place of that of the garuda in a Japanese sutra called the Emmyō Jizō-kyō (延命地蔵経), but this was likely written in the Edo period, long after the tengu's image was established. At least one early story in the Konjaku Monogatari describes a tengu carrying off a dragon, which is reminiscent of the garuda's feud with the nāga serpents. In other respects, however, the tengu's original behavior differs markedly from that of the garuda, which is generally friendly towards Buddhism. De Visser has speculated that the tengu may be descended from an ancient Shinto bird-demon which was syncretized with both the garuda and the tiāngǒu when Buddhism arrived in Japan. However, he found little evidence to support this idea.[13]

A later version of the Kujiki, an ancient Japanese historical text, writes the name of Amanozako, a monstrous female deity born from the god Susanoo's spat-out ferocity, with characters meaning tengu deity (天狗神). The book describes Amanozako as a raging creature capable of flight, with the body of a human, the head of a beast, a long nose, long ears, and long teeth that can chew through swords. An 18th-century book called the Tengu Meigikō (天狗名義考) suggests that this goddess may be the true predecessor of the tengu, but the date and authenticity of the Kujiki, and of that edition, in particular, remain disputed.[14]

Evil spirits and angry ghosts

[edit]

Iga no Tsubone confronts the tormented spirit of Sasaki no Kiyotaka, by Yoshitoshi. Sasaki's ghost appears with the wings and claws of a tengu.

The Konjaku Monogatarishū, a collection of stories published in the late Heian period, contains some of the earliest tales of tengu, already characterized as they would be for centuries to come. These tengu are the troublesome opponents of Buddhism, who mislead the pious with false images of the Buddha, carry off monks and drop them in remote places, possess women in an attempt to seduce holy men, rob temples, and endow those who worship them with unholy power. They often disguise themselves as priests or nuns, but their true form seems to be that of a kite.[15]

Throughout the 12th and 13th centuries, accounts continued of tengu attempting to cause trouble in the world. They were now established as the ghosts of angry, vain, or heretical priests who had fallen on the "tengu-realm" (天狗道, tengudō). They began to possess people, especially women and girls, and speak through their mouths (kitsunetsuki). Still the enemies of Buddhism, the demons also turned their attention to the royal family. The Kojidan tells of an Empress who was possessed, and the Ōkagami reports that Emperor Sanjō was made blind by a tengu, the ghost of a priest who resented the throne.[16]

One notorious tengu from the 12th century was himself the ghost of an emperor. The Hōgen Monogatari tells the story of Emperor Sutoku, who was forced by his father to abandon the throne. When he later raised the Hōgen Rebellion to take back the country from Emperor Go-Shirakawa, he was defeated and exiled to Sanuki Province in Shikoku. According to legend he died in torment, having sworn to haunt the nation of Japan as a great demon, and thus became a fearsome tengu with long nails and eyes like a kite's.[17]

In stories from the 13th century, tengu began to abduct young boys as well as the priests they had always targeted. The boys were often returned, while the priests would be found tied to the tops of trees or other high places. All of the tengu's victims, however, would come back in a state near death or madness, sometimes after having been tricked into eating animal dung.[7]

The tengu of this period were often conceived of as the ghosts of the arrogant, and as a result, the creatures have become strongly associated with vanity and pride. Today the Japanese expression tengu ni naru ("becoming a tengu") is still used to describe a conceited person.[18]

Great and small demons

[edit]

Crow Tengu, late Edo period (28×25×58 cm)

Tengu and a Buddhist monk, by Kawanabe Kyōsai. The tengu wears the cap and pom-pom sash of a follower of Shugendō.

In the Genpei Jōsuiki, written in the late Kamakura period, a god appears to Go-Shirakawa and gives a detailed account of tengu ghosts. He says that they fall onto the tengu road because, as Buddhists, they cannot go to Hell, yet as people with bad principles, they also cannot go to Heaven. He describes the appearance of different types of tengu: the ghosts of priests, nuns, ordinary men, and ordinary women, all of whom in life possessed excessive pride. The god introduces the notion that not all tengu are equal; knowledgeable men become daitengu (大天狗, greater tengu), but ignorant ones become kotengu (小天狗, small tengu).[19]

The philosopher Hayashi Razan lists the greatest of these daitengu as Sōjōbō of Kurama, Tarōbō of Atago, and Jirōbō of Hira.[20] The demons of Kurama and Atago are among the most famous tengu.[18]

A section of the Tengu Meigikō, later quoted by Inoue Enryō, lists the daitengu in this order:

Sōjōbō (僧正坊) of Mount Kurama

Tarōbō (太郎坊) of Mount Atago

Jirōbō (二郎坊) of the Hira Mountains

Sanjakubō (三尺坊) of Mount Akiha

Ryūhōbō (笠鋒坊) of Mount Kōmyō

Buzenbō (豊前坊) of Mount Hiko

Hōkibō (伯耆坊) of Mount Daisen

Myōgibō (妙義坊) of Mount Ueno (Ueno Park)

Sankibō (三鬼坊) of Itsukushima

Zenkibō (前鬼坊) of Mount Ōmine

Kōtenbō (高天坊) of Katsuragi

Tsukuba-hōin (筑波法印) of Hitachi Province

Daranibō (陀羅尼坊) of Mount Fuji

Naigubu (内供奉) of Mount Takao

Sagamibō (相模坊) of Shiramine

Saburō (三郎) of Mount Iizuna

Ajari (阿闍梨) of Higo Province[21]

Daitengu are often pictured in a more human-like form than their underlings, and due to their long noses, they may also be called hanatakatengu (鼻高天狗, tall-nosed tengu). Kotengu may conversely be depicted as more bird-like. They are sometimes called Karasu-Tengu (烏天狗, crow tengu), or koppa- or konoha-tengu (木葉天狗, 木の葉天狗, foliage tengu).[22] Inoue Enryō described two kinds of tengu in his Tenguron: the great daitengu, and the small, bird-like konoha-tengu who live in Cryptomeria trees. The konoha-tengu are noted in a book from 1746 called the Shokoku Rijin Dan (諸国里人談), as bird-like creatures with wings two meters across which were seen catching fish in the Ōi River, but this name rarely appears in literature otherwise.[23]

Creatures that do not fit the classic bird or yamabushi image are sometimes called tengu. For example, tengu in the guise of wood-spirits may be called guhin (occasionally written kuhin) (狗賓, dog guests), but this word can also refer to tengu with canine mouths or other features.[22] The people of Kōchi Prefecture on Shikoku believe in a creature called shibaten or shibatengu (シバテン, 芝天狗, lawn tengu), but this is a small childlike being who loves sumō wrestling and sometimes dwells in the water, and is generally considered one of the many kinds of kappa.[24] Another water-dwelling tengu is the kawatengu (川天狗, river tengu) of the Greater Tokyo Area. This creature is rarely seen, but it is believed to create strange fireballs and be a nuisance to fishermen.[25]

Protective spirits and deities

[edit]

A tengu mikoshi (portable shrine) in the city of Beppu, Ōita Prefecture, on Kyūshū

In Yamagata Prefecture among other areas, thickets in the mountains during summer, there are several tens of tsubo of moss and sand that were revered as the "nesting grounds of tengu," and in mountain villages in the Kanagawa Prefecture, they would cut trees at night and were called "tengu daoshi" (天狗倒し, tengu fall), and mysterious sounds at night of a tree being cut and falling, or mysterious swaying sounds despite no wind, were considered the work of mountain tengu. It is also theorized that shooting a gun three times would make this mysterious sound stop. Besides this, in the Tone District, Gunma Prefecture, there are legends about the "tengu warai" (天狗笑い, tengu laugh) about how one would hear laughter out of nowhere, and if one simply presses on further, it'd become an even louder laugh, and if one tries laughing back, it'd laugh even louder than before, and the "tengu tsubute" (天狗礫, tengu pebble) (said to be the path that tengu go on) about how when walking on mountain paths, there would be a sudden wind, the mountain would rumble, and stones would come flying, and places tengu live such as "tenguda" (天狗田, tengu field), "tengu no tsumetogi ishi" (天狗の爪とぎ石, tengu scratching stone), "tengu no yama" (天狗の山, tengu mountain), "tengudani" (天狗谷, tengu valley), etc., in other words, "tengu territory" (天狗の領地) or "tengu guest quarters" (狗賓の住処). In Kanazawa's business district Owari in Hōreki 5 (1755), it is said that a "tengu tsubute" (天狗つぶて) was seen. In Mt. Ogasa, Shizuoka Prefecture, a mysterious phenomenon of hearing the sound of hayashi from the mountains in the summer was called "tengubayashi" (天狗囃子), and it is said to be the work of the tengu at Ogasa Jinja.[26] On Sado Island (Sado, Niigata Prefecture), there were "yamakagura" (山神楽, mountain kagura), and the mysterious occurrence of hearing kagura from the mountains was said to be the work of a tengu.[27] In Tokuyama, Ibi District, Gifu Prefecture (now Ibigawa), there were "tengu taiko" (天狗太鼓), and the sound of taiko (drums) from the mountains was said to be a sign of impending rain.[28]

The Shasekishū, a book of Buddhist parables from the Kamakura period, makes a point of distinguishing between good and bad tengu. The book explains that the former are in command of the latter and are the protectors, not opponents, of Buddhism – although the flaw of pride or ambition has caused them to fall onto the demon road, they remain the same good, dharma-abiding persons they were in life.[29]

The tengu's unpleasant image continued to erode in the 17th century. Some stories now presented them as much less malicious, protecting and blessing Buddhist institutions rather than menacing them or setting them on fire. According to a legend in the 18th-century Kaidan Toshiotoko (怪談登志男), a tengu took the form of a yamabushi and faithfully served the abbot of a Zen monastery until the man guessed his attendant's true form. The tengu's wings and huge nose then reappeared. The tengu requested a piece of wisdom from his master and left, but he continued, unseen, to provide the monastery with miraculous aid.[30]

In the 18th and 19th centuries, tengu came to be feared as the vigilant protectors of certain forests. In the 1764 collection of strange stories Sanshu Kidan (三州奇談), a tale tells of a man who wanders into a deep valley while gathering leaves, only to be faced with a sudden and ferocious hailstorm. A group of peasants later tell him that he was in the valley where the guhin live, and anyone who takes a single leaf from that place will surely die. In the Sōzan Chomon Kishū (想山著聞奇集), written in 1849, the author describes the customs of the wood-cutters of Mino Province, who used a sort of rice cake called kuhin-mochi to placate the tengu, who would otherwise perpetrate all sorts of mischief. In other provinces a special kind of fish called okoze was offered to the tengu by woodsmen and hunters, in exchange for a successful day's work.[31] The people of Ishikawa Prefecture have until recently believed that the tengu loathe mackerel, and have used this fish as a charm against kidnappings and hauntings by the mischievous spirits.[32]

Tengu are worshipped as beneficial kami (gods or revered spirits) in various regions. For example, the tengu Saburō of Izuna is worshipped on that mountain and various others as Izuna Gongen (飯綱権現, "incarnation of Izuna"), one of the primary deities in Izuna Shugen, which also has ties to fox sorcery and the Dakini of Tantric Buddhism. Izuna Gongen is depicted as a beaked, winged figure with snakes wrapped around his limbs, surrounded by a halo of flame, riding on the back of a fox and brandishing a sword. Worshippers of tengu on other sacred mountains have adopted similar images for their deities, such as Sanjakubō (三尺坊) or Akiba Gongen (秋葉権現) of Akiba and Dōryō Gongen (道了権現) of Saijō-ji Temple in Odawara.[33]

In popular folk tales

[edit]

An elephant and a flying tengu, by Utagawa Kuniyoshi

The folk hero Kintarō upsets a nest of small tengu.

Tengu appear frequently in the orally transmitted tales collected by Japanese folklorists. As these stories are often humorous, they tend to portray tengu as ridiculous creatures who are easily tricked or confused by humans. Some common folk tales in which tengu appear include:

"The Tengu's Magic Cloak" (天狗の隠れみの, Tengu no Kakuremino): A boy looks through an ordinary piece of bamboo and pretends he can see distant places. A tengu, overwhelmed by curiosity, offers to trade it for a magic straw cloak that renders the wearer invisible. Having duped the tengu, the boy continues his mischief while wearing the cloak. Another version of this story tells of an ugly old man who tricks a tengu into giving him his magical cloak and causes mayhem for his fellow villagers. The story ends with the tengu regaining the coat through a game of riddle exchange and punishes the man by turning him into a wolf.[34]

"The Old Man's Lump Removed" (瘤取り爺さん, Kobu-tori Jiisan): An old man has a lump or tumor on his face. In the mountains he encounters a band of tengu making merry and joins their dancing. He pleases them so much that they want him to join them the next night, and offer a gift for him. In addition, they take the lump off his face, thinking that he will want it back and therefore have to join them the next night. An unpleasant neighbor, who also has a lump, hears of the old man's good fortune and attempts to repeat it, and steal the gift. The tengu, however, simply gives him the first lump in addition to his own, because they are disgusted by his bad dancing, and because he tried to steal the gift.[35]

"The Tengu's Fan" (天狗の羽団扇, Tengu no Hauchiwa) A scoundrel obtains a tengu's magic fan, which can shrink or grow noses. He secretly uses this item to grotesquely extend the nose of a rich man's daughter and then shrinks it again in exchange for her hand in marriage. Later he accidentally fans himself while he dozes, and his nose grows so long it reaches heaven, resulting in painful misfortune for him.[36]

"The Tengu's Gourd" (天狗の瓢箪, Tengu no Hyōtan): A gambler meets a tengu, who asks him what he is most frightened of. The gambler lies, claiming that he is terrified of gold or mochi. The tengu answers truthfully that he is frightened of a kind of plant or some other mundane item. The tengu, thinking he is playing a cruel trick, then causes money or rice cakes to rain down on the gambler. The gambler is of course delighted and proceeds to scare the tengu away with the thing he fears most. The gambler then obtains the tengu's magic gourd (or another treasured item) that was left behind.[37]

Martial arts

[edit]

Ushiwaka-maru training with the tengu of Mount Kurama, by Kunitsuna Utagawa. This subject is very common in ukiyo-e.

Japan's regent Hōjō Tokimune, who showed down the Mongols, fights off tengu

During the 14th century, the tengu began to trouble the world outside of the Buddhist clergy, and like their ominous ancestors the tiāngǒu, the tengu became creatures associated with war.[38] Legends eventually ascribed to them great knowledge in the art of skilled combat.

This reputation seems to have its origins in a legend surrounding the famous warrior Minamoto no Yoshitsune. When Yoshitsune was a young boy going by the name of Ushiwaka-maru, his father, Yoshitomo, was assassinated by the Taira clan. Taira no Kiyomori, head of the Taira, allowed the child to survive on the grounds that he be exiled to the temple on Mount Kurama and become a monk. But one day in the Sōjō-ga-dani Valley, Ushiwaka encountered the mountain's tengu, Sōjōbō. This spirit taught the boy the art of swordsmanship so that he might bring vengeance on the Taira.[39]

Originally the actions of this tengu were portrayed as another attempt by demons to throw the world into chaos and war, but as Yoshitsune's renown as a legendary warrior increased, his monstrous teacher came to be depicted in a much more sympathetic and honorable light. In one of the most famous renditions of the story, the Noh play Kurama Tengu, Ushiwaka is the only person from his temple who does not give up an outing in disgust at the sight of a strange yamabushi. Sōjōbō thus befriends the boy and teaches him out of sympathy for his plight.[40]

Two stories from the 19th century continue this theme: In the Sōzan Chomon Kishū, a boy is carried off by a tengu and spends three years with the creature. He comes home with a magic gun that never misses a shot. A story from Inaba Province, related by Inoue Enryō, tells of a girl with poor manual dexterity who is suddenly possessed by a tengu. The spirit wishes to rekindle the declining art of swordsmanship in the world. Soon a young samurai appears to whom the tengu has appeared in a dream, and the possessed girl instructs him as an expert swordsman.[41]

In popular culture

[edit]

Tengu continue to be popular subjects in modern fiction, both in Japan and other countries. They often appear among the many characters and creatures featured in Japanese cinema, animation, comics, role-playing games, and video games.[42]

The Unicode emoji character U+1F47A (👺) represents a tengu, under the name "Japanese Goblin".[43]

The Touhou Project series prominently features tengu as a species of youkai within the setting. No less than five named characters are tengu, three of which are recurring characters, and one of which is a major character.[44]

In Gargoyles the gargoyles of the Ishimaru Clan are modeled after the Tengu and in-universe were their inspiration.

In Yugioh the Great Long Nose card is modeled after the Tengu.

Nuzleaf and Shiftry from the Pokémon franchise are based on the tengu.[45][46]

The tengu featured in the 2013 movie 47 Ronin, with their lord played by Togo Igawa.[47]

Tactics features a shinto onmyoji who spends his life searching for a tengu, whom he names Haruka and another tengu named Sugino. Each tengu represents a different type: Haruka is a "black" tengu who was born as such and is more powerful than "white" Sugino, who is noted to be a former human priest who grew too arrogant and is worshipped as a mountain god. They primarily appear as humans with wings.[48]

In Around the World in Eighty Days, Passepartout joins a circus in Japan where he dresses as a tengu (spelled Tingou in the book).

In Ghost of Tsushima, the "Mythic Quest" Curse of Uchitsune features a man with a tengu mask as the main antagonist of the Quest. In the "Legends Mode" Tengus are an enemy type that can also summon crows to attack players.

Tengu Man is a boss in the 1996 video game Mega Man 8.

In the 2003 television series of Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, an ancient mystical sword wielded by the great Tengu Shredder came into the possession of modern Tokyo ninja clan of the Foot and ended up in the hands of the four title characters. An ancient amulet called the Heart of Tengu gave the Utrom Shredder, and later Karai, command over the five Mystic Foot ninja. In Season Five: Ninja Tribunal, the original demonic Tengu Shredder who had possessed the original ninja master Oroku Saki millennia ago, returned to remake the modern world in his twisted image, but was ultimately destroyed by the Ninja Turtles' combined strength as mystical dragons and the spirit of Hamato Yoshi.

In Sekiro: Shadows Die Twice, the sickly, elderly leader of the Ashina, Isshin Ashina, dresses up as a Tengu when sneaking out to kill the rival government's assassins and ninjas. While wearing this disguise, the game refers to him as "The Tengu of Ashina".

In the 2020 video game Genshin Impact, the character Kujou Sara is a tengu, and other tengu (as well as other youkai) play a significant role in the history of the fictional nation of Inazuma, which is in turn based off of Japanese culture and mythology.

0 notes