#Irene Doukaina

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

"The most notable players in Palaiologue politics were the empresses Yolanda-Irene of Montferrat and Anna of Savoy, and on the whole their record is woeful: Yolanda-Irene of Montferrat, second wife of Andronikos II, was unable to comprehend the succession rights of her eldest stepson, Michael IX, and since her husband remained obstinately unmoved by her representations she flounced off with her three sons to Thessalonika where she kept a separate court for many years from 1303 to her death in 1317. From her own domain she issued her own decrees, conducted her own foreign policy and plotted against her husband with the Serbs and Catalans: in mitigation, she had seen her five-year-old daughter married off to the middle-aged Serbian lecher Milutin, and considered that her eldest son John had been married beneath him to a Byzantine aristocrat, Irene Choumnaina. She died embittered and extremely wealthy.

When Yolanda’s grandson Andronikos III died early, leaving a nine-year old son John V and no arrangements for a regent, the empress Anna of Savoy assumed the regency. In so doing she provoked a civil war with her husband’s best friend John Kantakouzenos, and devastated the empire financially, bringing it to bankruptcy and pawning the crown jewels to Venice, as well as employing Turkish mercenaries and, it appears, offering to have her son convert to the church of Rome. Gregoras specifically blames her for the civil war, though he admits that she should not be criticised too heavily since she was a woman and a foreigner. Her mismanagement was not compensated for by her later negotiations in 1351 between John VI Kantakouzenos and her son in Thessalonika, who was planning a rebellion with the help of Stephen Dushan of Serbia. In 1351 Anna too settled in Thessalonika and reigned over it as her own portion of the empire until her death in c. 1365, even minting her own coinage.

These women were powerful and domineering ladies par excellence, but with the proviso that their political influence was virtually minimal. Despite their outspokenness and love of dominion they were not successful politicians: Anna of Savoy, the only one in whose hands government was placed, was compared to a weaver’s shuttle that ripped the purple cloth of empire. But there were of course exceptions. Civil wars ensured that not all empresses were foreigners and more than one woman of Byzantine descent reached the throne and was given quasi-imperial functions by her husband.

Theodora Doukaina Komnene Palaiologina, wife of Michael VIII, herself had imperial connections as the great-niece of John III Vatatzes, and issued acts concerning disputes over monastic properties during her husband’s reign, even addressing the emperor’s officials on occasion and confirming her husband’s decisions. Nevertheless, unlike other women of Michael’s family who went into exile over the issue, she was forced to support her husband’s policy of church union with Rome, a stance which she seems to have spent the rest of her life regretting. She was also humiliated when he wished to divorce her to marry Constance-Anna of Hohenstaufen, the widow of John III Vatatzes.

Another supportive empress consort can be seen in Irene Kantakouzene Asenina, whose martial spirit came to the fore during the civil war against Anna of Savoy and the Palaiologue ‘faction’. Irene in 1342 was put in charge of Didymoteichos by her husband John VI Kantakouzenos; she also organised the defence of Constantinople against the Genoese in April 1348 and against John Palaiologos in March 1353, being one of the very few Byzantine empresses who took command in military affairs. But like Theodora, Irene seems to have conformed to her husband’s wishes in matters of policy and agreed with his decisions concerning the exclusion of their sons from the succession and their eventual abdication in 1354.

Irene and her daughter Helena Kantakouzene, wife of John V Palaiologos, were both torn by conflicting loyalties between different family members, and Helena in particular was forced to mediate between her ineffectual husband and the ambitions of her son and grandson. She is supposed to have organised the escape of her husband and two younger sons from prison in 1379 and was promptly taken hostage with her father and two sisters by her eldest son Andronikos IV and imprisoned until 1381; her release was celebrated with popular rejoicing in the capital. According to Demetrios Kydones she was involved in political life under both her husband and son, Manuel II, but her main role was in mediating between the different members of her family.

In a final success story, the last Byzantine emperor, Constantine XI, owed his throne to his mother. The Serbian princess Helena Dragash, wife of Manuel II Palaiologos, in the last legitimating political manoeuvre by a Byzantine empress, successfully managed to keep the throne for her son Constantine and fend off the claims of his brother Demetrios. She arranged for Constantine’s proclamation as emperor in the Peloponnese and asserted her right to act as regent until his arrival in the capital from Mistra in 1449.

Despite the general lack of opportunity for them to play a role in politics, Palaiologue imperial women in the thirteenth century found outlets for their independent spirit and considerable financial resources in other ways. They were noted for their foundation or restoration of monastic establishments and for their patronage of the arts. Theodora Palaiologina restored the foundation of Constantine Lips as a convent for fifty nuns, with a small hospital for laywomen attached, as well as refounding a smaller convent of Sts Kosmas and Damian. She was also an active patron of the arts, commissioning the production of manuscripts like Theodora Raoulaina, her husband’s niece. Her typikon displays the pride she felt in her family and position, an attitude typically found amongst aristocratic women.

Clearly, like empresses prior to 1204, she had considerable wealth in her own hands both as empress and dowager. She had been granted the island of Kos as her private property by Michael, while she had also inherited land from her family and been given properties by her son Andronikos. Other women of the family also display the power of conspicuous spending: Theodora Raoulaina used her money to refound St Andrew of Crete as a convent where she pursued her scholarly interests.

Theodora Palaiologina Angelina Kantakouzene, John Kantakouzenos’s mother, was arguably the richest woman of the period and financed Andronikos III’s bid for power in the civil war against his grandfather. Irene Choumnaina Palaiologina, in name at least an empress, who had been married to Andronikos II’s son John and widowed at sixteen, used her immense wealth, against the wishes of her parents, to rebuild the convent of Philanthropes Soter, where she championed the cause of ‘orthodoxy’ against Gregory Palamas and his hesychast followers. Helena Kantakouzene, too, wife of John V, was a patron of the arts. She had been classically educated and was the benefactor of scholars, notably of Demetrios Kydones who dedicated to her a translation of one of the works of St Augustine.

The woman who actually holds power in this period, Anna of Savoy, does her sex little credit: like Yolanda she appears to have been both headstrong and greedy, and, still worse, incompetent. In contrast, empresses such as Irene Kantakouzene Asenina reflect the abilities of their predecessors: they were educated to be managers, possessed of great resources, patrons of art and monastic foundations, and, given the right circumstances, capable of significant political involvement in religious controversies and the running of the empire. Unfortunately they generally had to show their competence in opposition to official state positions. While they may have wished to emulate earlier regent empresses, they were not given the chance: the women who, proud of their class and family, played a public and influential part in the running of the empire belonged to an earlier age."

Byzantine Empresses: Women and Power in Byzantium AD 527-1204, Lynda Garland

#history#women in history#historyedit#queens#empresses#byzantine empire#byzantine history#medieval women#13th century#14th century#15th century#historyblr#historical figures#byzantine empresses#irene of montferrat#anna of savoy#helena dragas#Theodora Doukaina Komnene Palaiologina#Irene Kantakouzene Asenina#Helena Kantakouzene

77 notes

·

View notes

Text

Irene Doukaina Laskarina was empress consort of Bulgaria (1258–1268). She was the second wife of Tsar Constantine Tikh of Bulgaria.

She was a daughter of Emperor Theodore II Laskaris of Nicaea, and his wife Elena of Bulgaria, and sister of Nicaean Emperor John IV Laskaris. Her maternal grandparents were Tsar Ivan Asen II and Anna Maria of Hungary.

In 1257, Irene married Bulgarian nobleman Constantine Tikh as his second wife. Her husband was a pretender to the Bulgarian crown. Constantine was proud to be married to a granddaughter of Tsar Ivan Asen II, and he adopted the Bulgarian dynastic name Asen to enhance his claim to the crown. In the next year Constantine was elected Tsar of Bulgaria by a boyar council in Tarnovo and Irene become his consort.

In 1261 Irene's young brother, Emperor John IV Laskaris, was deposed and blinded by Nicaean regent Michael VIII Palaiologos, who had just regained Constantinople from the Latin Empire, re-establishing the Byzantine Empire. Tsaritsa Irene was a bitter enemy of the usurper. She became a leader of the anti-Byzantine party in the Bulgarian court.

Irene died in 1268. She had no children.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Wives and Daughters of Byzantine Emperors: Ages at First Marriage

I have only included women whose birth dates and dates of marriage are known within at least 1-2 years, therefore, this is not a comprehensive list.

Theodora, wife of Justinian I; age 35 when she married Justinian in 435 AD

Constantina, wife of Maurice; age 22 when she married Maurice in 582 AD

Eudokia, wife of Heraclius; age 30 when she married Heraclius in 610 AD

Fausta, wife of Constans II; age 12 when she married Constans in 642 AD

Maria of Amnia, wife of Constantine VI; age 18 when she married Constantine in 788 AD

Theodote, wife of Constantine VI; age 15 when she married Constantine in 795 AD

Euphrosyne, wife of Michael II; age 33 when she married Michael in 823 AD

Theodora, wife of Theophilos; age 15 when she married Theophilos in 830 AD

Eudokia Dekapolitissa, wife of Michael III; age 15 when she married Michael in 855 AD

Eudokia Ingerina, wife of Basil I; age 25 when she married Basil in 865 CE

Theophano Martinakia, wife of Leo VI; age 16/17 when she married Leo in 882/883 AD

Helena Lekapene, wife of Constantine VII; age 9 when she married Constantine in 919 AD

Theodora, wife of John I Tzimiskes; age 25 when she married John in 971 AD

Theophano, wife of Romanos II (and later Nikephoros II); age 14 when she married Romanos in 955 AD

Anna Porphyrogenita, daughter of Romanos II; age 27 when she married Vladimir in 990 AD

Zoe Porphyrogenita, wife of Romanos III (and later Michael IV & Constantine IX); age 50 when she married Romanos in 1028 AD

Eudokia Makrembolitissa, wife of Constantine X Doukas (and later Romanos IV Diogenes); age 19 when she married Constantine in 1049 AD

Maria of Alania, wife of Michael II Doukas (and later Nikephoros III Botaniates); age 12 when she married Michael in 1065 AD

Irene Doukaina, wife of Alexios I Komnenos; age 11 when she married Alexios in 1078 AD

Anna Komnene, wife of Nikephoros Bryennios the Younger; age 14 when she married Nikephoros in 1097 AD

Maria Komnene, daughter of Alexios I Komnenos; age 14/15 when she married Nikephoros Katakalon in 1099/1100 AD

Eudokia Komnene, daughter of Alexios Komnenos; age 15 when she married Michael Iasites in 1109 AD

Theodora Komnene, daughter of Alexios Komnenos; age 15 when she married Constantine Kourtikes in 1111 AD

Maria of Antioch, wife of Manuel I Komnenos; age 16 when she married Manuel in 1161 AD

Euphrosyne Doukaina Kamatera, wife of Alexios III Angelos; age 14 when she married Alexios in 1169 AD

Maria Komnene, daughter of Manuel I Komnenos; age 27 when she married Renier of Montferrat in 1179 AD

Anna of France, wife of Alexios II Komnenos (and later Andronikos Komnenos); age 9 when she married Alexios in 1180 AD

Eudokia Angelina, daughter of Alexios III Angelos; age 13 when she married Stefan Nemanjic in 1186 AD

Margaret of Hungary, wife of Isaac II Angelos; age 11 when she married Isaac in 1186 AD

Anna Komnene Angelina, daughter of Alexios III Angelos; age 14 when she married Isaac Komnenos Vatatzes in 1190 AD

Irene Angelina, daughter of Isaac II Angelos; age 16 when she married Philip of Swabia in 1197 AD

Philippa of Armenia, wife of Theodore I Laskaris; age 31 when she married Theodore in 1214 AD

Maria of Courtenay, wife of Theodore I Laskaris; age 15 when she married Theodore in 1219 AD

Maria Laskarina, daughter of Theodore I Laskaris; age 12 when she married Bela IV of Hungary in 1218 AD

Elena Asenina of Bulgaria, wife of Theodore II Laskaris; age 11 when she married Theodore in 1235 AD

Anna of Hohenstaufen, wife of John III Doukas Vatatzes; age 14 when she married John in 1244 AD

Theodora Palaiologina, wife of Michael VIII Palaiologos; age 13 when she married Michael in 1253 AD

Anna of Hungary, wife of Andronikos II Palaiologos; age 13 when she married Andronikos in 1273 AD

Eudokia Palaiologina, daughter of Michael VIII Palaiologos; age 17 when she married John II Megas Komnenos in 1282 AD

Irene of Montferrat, wife of Andronikos II Palaiologos; age 10 when she married Andronikos in 1284 AD

Rita of Armenia, wife of Michael IX Palaiologos; age 16 when she married Michael in 1294 AD

Simonis Palaiologos, daughter of Andronikos II Palaiologos; age 5 when she married Stefan Milutin in 1299 AD

Irene of Brunswick, wife of Andronikos III Palaiologos; age 25 when she married Andronikos in 1318 AD

Anna of Savoy, wife of Andronikos III Palaiologos; age 20 when she married Andronikos in 1326 AD

Irene Palaiologina, daughter of Andronikos III Palaiologos; age 20 when she married Basil of Trebizond in 1335 AD

Maria-Irene Palaiologina, daughter of Andronikos III Palaiologos; age 9 when she married Michael Asen IV of Bulgaria in 1336 AD

Theodora Kantakouzene, daughter of John VI Palaiologos; age 16 when she married Orhan Gazi in 1346 AD

Helena Kantakouzene, wife of John V Palaiologos; age 13 when she married John in 1347 AD

Keratsa of Bulgaria, wife of Andronikos IV Palaiologos; age 14 when she married Andronikos in 1362 AD

Helena Dragas, wife of Manuel II Palaiologos; age 20 when she married Manuel in 1392 AD

Anna of Moscow, wife of John VIII Palaiologos; age 21 when she married John in 1414 AD

Maria Komnene, wife of John VIII Palaiologos; age 23 when she married John in 1427 AD

Helena Palaiologina, daughter of Theodore II Palaiologos; age 14 when she married John II of Cyprus in 1442 AD

Helena Palaiologina, daughter of Thomas Palaiologos; age 15 when she married Lazar Brankovic in 1446 AD

Sophia Palaiologina, daughter of Thomas Palaiologos; age 23 when she married Ivan III of Russia in 1472 AD

The average age at first marriage was 17 years old.

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

@just-late-roman-republic-things

I think for the women section in Byzantine, you can add Aelia Eudoxia, the wife of Arcadius, Aelia Pulcheria (problematic though, not sure if you want to include her) Aelia Eudocia, the wife of Theodosius II and Galla Placidia.

Anna Komnene who is the author of the Alexiad, a biographical work that accounts Alexios I Komnenos' reign, her father.

Her mother Irene Doukaina.

Empress Theodora, wife of Justinian the Great (I) (for obvious reasons and a famous one, not sure if you include her in your list.)

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Anna Comnena - Primeira mulher historiadora

Anna Comnena, princesa de Bizâncio, 1083-1153, filha de Alexius I Comnenus, imperador bizantino, e de Irene Doukaina, esposa de Nikephoros Bryennoise, o Jovem.

Como filha de um imperador bizantino, Ana foi bem instruída em astronomia, medicina, história, assuntos militares, história, geografia e matemática. O seu pai encarregou-a do grande hospital que construiu em 1096, com 10 000 camas para doentes e órfãos, onde ensinava medicina; era considerada uma especialista em gota, tendo tratado o seu próprio pai durante a sua última doença.

Anna era a filha mais velha e deveria ter sido a primeira na sucessão. Quando, em 1112, o pai adoeceu de reumatismo e ficou incapaz de andar durante muito tempo, entregou o governo civil à mãe, Irene, que apoiou o direito da filha ao trono. Anna e o seu marido, César Nikephoros Bryennios, filho de uma família aristocrática que tinha disputado o trono antes da ascensão de Aleixo I, assumiram que o trono seria deles, uma vez que o seu casamento era considerado uma união política, embora a sua união de quarenta anos tenha produzido quatro filhos. Quando Aleixo estava a morrer, o seu irmão terá tirado o anel do imperador, declarando o seu direito ao trono. Ana e a sua mãe tentaram desviar a sucessão, mas não tiveram sucesso. Durante o funeral do seu pai, houve uma tentativa de assassinar o seu irmão João, seguida de outros esforços para o destituir, até que Ana foi forçada a renunciar às suas propriedades. Após a morte do marido, em 1137, entrou para o convento de Kecharitomene, em Constantinopla, "Cheia de Graça", fundado pela mãe, onde viveu até à sua morte, em 1153, tornando-se freira apenas no leito de morte.

Durante os anos que passou no convento, em prisão domiciliária e em reclusão, estudou história e filosofia, organizando encontros intelectuais. Em 1148, Anna começou a escrever o seu livro de 15 volumes, The Alexiad, que foi iniciado pelo seu marido e é considerado a obra mais bem conseguida escrita por uma mulher antes do Renascimento, embora seguisse convenções e fórmulas antigas e engenhosamente emprestadas pela Ilíada e pela Odisseia. Os seus escritos históricos abrangem o reinado do seu pai e são a principal fonte da história política bizantina, incluindo a primeira cruzada, a reação bizantina à cruzada e o estabelecimento do reino latino de Jerusalém.

Foi a primeira mulher historiadora do mundo a escrever sobre assuntos militares, religiosos, medicina e astronomia e desempenhou um papel fundamental no renascimento dos estudos aristotélicos. Os seus contemporâneos, como o bispo de Éfeso Georgios Tornikes, consideravam Ana como uma pessoa que tinha atingido "o mais alto cume da sabedoria, tanto secular como divina".

Fonte ~ https://www.medievalwomen.org/anna-comnena-princess-of-byzantium.html

Imagem 📸 criada com a ajuda de Inteligência Artificial, utilizando o NightCafe Creator.

0 notes

Photo

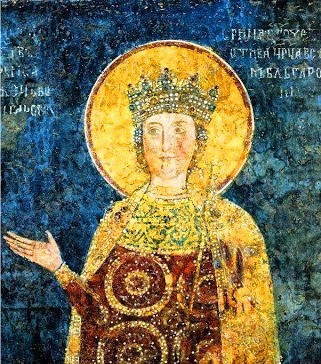

WOMEN’S HISTORY ☦ EIRĒNĒ KOMNĒNḖ DOUKAINA (fl. 13th century)

Eirēnē Doukaina was the third of the four children of Maria Petraliphaina and Theodōros Komnēnos Doukas, a grandson of Konstantinos Angelos and Theodora Porphyrogénnētē Komnene¹. After the Fourth Crusade sacked Constantinople in 1204, her father fled to Antaloia and took up service under Theodōros I Laskaris and married Maria before going to aid his half-brother, Mikhaēl Komnēnos Doukas, in ruling over Epirus. Mikhaēl was assassinated in 1214 or 1215 and his only son was illegitimate and young, so Theodōros found it easy to gain ruler over Epirus. In 1217, Theodōros took Pierre II de Courtenay² captive while Pierre was journeying to Constantinople to claim the title of emperor. In 1224, Theodōros conquered the city of Thessaloniki and then proclaimed himself emperor. Shortly after, in 1230, Theodōros declared war against Bulgaria, but was defeated in the Battle of Klokotnitsa, so Eirēnē and her family were all taken hostage by Ivan Asen II, tzar of Bulgaria. Eirēnē was considered a very beautiful woman and Ivan Asen fell in love with her. After the death of his second wife, Anna Mária³, in 1237, Ivan asked Eirēnē to marry him and she agreed, if he released her father from captivity. Ivan agreed and released the blinded Theodōros, who returned to Thessalonica and had his brother, Manouel, ousted from power. Ivan and Eirēnē married and had a son and two daughters. After Ivan's death, his son by Anna Mária succeeded as tsar, but died in 1246, leaving the throne to Eirēnē's son, Mihail II Asen. Mihail was assassinated in 1256 by his cousin, Kaliman, and Eirēnē returned to Thessalonica and entered a convent. Kaliman lasted less than a year before being overthrown by Mitso Asen, the husband of Eirēnē's daughter, Maria Asenina.

¹ Daughter of Alexios I Komnēnos and Eirēnē Doukaina and younger sister of Anna Porphyrogénnētē Komnēnē . ² Grandson of Louis VI de France and Adelaide di Savoia. ³ Daughter of II. András magyar király and Gertrud von Andechs.

#irene doukaina#greek history#bulgarian history#european history#asian history#women's history#history#women's history graphics#nanshe's graphics#medieval

19 notes

·

View notes

Photo

ANNA KOMNENE:

ANNA Komnene (aka Anna Comnena, 1083-1153 CE) was the eldest daughter of Byzantine emperor Alexios I Komnenos(r. 1081-1118 CE) and the author of a lengthy biography of her father’s reign, the Alexiad. Although not an impartial history, Anna’s position at court, her thorough research of sources and a good measure of pithy observation and insightful opinion have all ensured the Alexiad remains one of the most important and colourful primary sources of Byzantine history.

Anna Komnene was born in 1083 CE in the Porphyra, the purple room of the Byzantine royal palace in Constantinople where royal babies were usually born and which was a potent symbol of royal legitimacy. She was the eldest daughter of Alexios I Komnenos and his wife the Empress Irene Doukaina. The emperor had no sons and so, for a time, Anna was the official heir following her betrothal to Constantine Doukas, the son of Michael VII (r. 1071-1078 CE). Constantine was nine years older than Anna and the empress-to-be later wrote of him in the following glowing terms:

“[Constantine was] seemingly endowed with a heavenly beauty not of this world, his manifold charms captivated the beholder, in short, anyone who saw him would say, He is like the painter’s Cupid” (Herrin, 233)

Read More

242 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Byzantine History Meme - Anna Komnene

Anna Komnene was born on December 1083 as the eldest child of emperor Alexius I and Irene Doukaina. She was called porphyrogenita, a name given to every child born during their fathers’ reign. Rumor has is that the Imperial Palace had a chamber called “Porphyra” where empresses gave birth to their children. Until the birth of her brother, Anna was heir apparent to the Byzantine throne and as an imperial princess was betrothed at a young age to Constantine Doukas, son of Michael VII and was proclaimed co- emperor for the second time. Anna grew up in his mother’s household and studied greek literature and history, philosophy, theology, mathematics, and medicine. In 1087 her brother John II was born and replaced her in the line of succession frustrating Anna. Ten years later her fiance died so she was once again betrothed and then married to general Nickephorus Bryennius with whom she had four children. Despite Anna’s tireless efforts to make her husband emperor, her brother succeeded Alexius and Anna was sent into exile after losing all of her fortune. In the monastery where she spent the rest of her life she wrote Alexiad and became the first female historian.

81 notes

·

View notes

Text

"During the reign of her husband the primary function of an Augusta was the orchestration of ceremonial at the imperial court, a highly stylised and intricate affair given the ceremonial nature of imperial life, which was based primarily around the Great Palace, a huge complex extending from the hippodrome to the sea walls, with its own gardens, sporting grounds, barracks, audience halls and private apartments; the Great Palace was the official residence of the emperor until 1204, though under Alexios Komnenos the imperial family usually occupied the Blachernai Palace in the north-west of the city, while there were other residential palaces in and outside of the capital. Empresses’ public life remained largely separate from that of their husbands, especially prior to the eleventh century, and involved a parallel court revolving around ceremonies involving the wives of court officials. For this reason an empress at court was considered to be essential: Michael II was encouraged to marry by his magnates because an emperor needed a wife and their wives an empress.

The patriarch Nicholas permitted the third marriage of Leo VI because of the need for an empress in the palace: ‘since there must be a Lady in the Palace to manage ceremonies affecting the wives of your nobles, there is condonation of the third marriage…’ While the empress primarily presided over her own ceremonial sphere, with her own duties and functions, she could be also present at court banquets, audiences and the reception of envoys, as well as taking part in processions and in services in St Sophia and elsewhere in the city; one of her main duties was the reception of the wives of foreign rulers and heads of state. Nor were empresses restricted to the capital: both Martina and Irene Doukaina accompanied their husbands on campaign.

The empress was also in charge of the gynaikonitis, the women’s quarters in the palace, where she had her own staff, primarily though not entirely composed of eunuchs, under the supervision of her own chamberlain; when empresses like Irene, Theodora wife of Theophilos, and Zoe Karbounopsina came to power they often relied on this staff of eunuchs as their chief ministers and even their generals. Theodora the Macedonian was unusual in not appointing a eunuch as her chief minister, perhaps because her age made such gender considerations unnecessary. The ladies of the court were the wives of patricians and other dignitaries: a few ladies, the zostai, were especially appointed and held rank in their own right. The zoste patrikia was at the head of these ladies (she was usually a relative of the empress),and dined with the imperial family."

Byzantine Empresses: Women and Power in Byzantium AD 527-1204, Lynda Garland

#history#women in history#women's history#byzantine empresses#byzantine empire#byzantine history#eastern roman empire#queens#historyedit#historyblr#medieval history#irene of athens

97 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Irene Doukaina or Ducaena (c. 1066 – 19 February 1138) was a Byzantine empress by marriage to the Byzantine emperor Alexios I Komnenos. She was the mother of Emperor John II Komnenos and the historian Anna Komnene.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hero of December: Anna Komnene

Hero of December: Anna Komnene

Our woman hero of December is Anna Komnene! She was a Byzantine princess, scholar, physician, hospital administrator, and historian. She was the daughter of the Byzantine Emperor Alexios I Komnenos and his wife Irene Doukaina. She is best known for her attempt to usurp her brother, John II Komnenos, and for her work The Alexiad, an account of her father’s reign. (more…)

View On WordPress

0 notes

Photo

PEOPLE OF THE ANCIENT WORLD: John II Komenos (Emperor of the Byzantine Empire)

JOHN II Komnenos “the Handsome” was emperor of the Byzantine Empire from 1118 CE to 1143 CE. John, almost constantly on campaign throughout his reign, would continue the military successes of his father Alexios I with significant victories in the Balkans, Armenia, and Asia Minor. The Byzantine Empire, thus, regained something of its former sparkle and the respect of its rivals across the Mediterranean.

John was born in 1087 CE, the son of emperor Alexios I Komnenos (r. 1081-1118 CE) and Irene Doukaina. When Alexios died of disease on 15 August 1118 CE, John, his chosen heir, became emperor as John II Komnenos. All very straightforward but things could have been very different. This is because it was actually Alexios’ eldest daughter, Anna Komnene, who was for a time Alexios' official heir following her marriage to Constantine Doukas, the son of Michael VII (r. 1071-1078 CE). When John was born, he, naturally, became the chosen heir.

Read More

78 notes

·

View notes

Photo

PEOPLE OF THE ANCIENT WORLD: Alexios I Komnenos (Emperor of the Byzantine Empire)

ALEXIOS I Komnenos (Alexius Comnenus) was emperor of the Byzantine Empire from 1081 to 1118 CE. Regarded as one of the great Byzantine rulers, Alexios defeated the Normans, the Pechenegs, and, with the help of the First Crusaders, the Seljuks to put the empire back on its feet after years of decline. He would found the Komnenoi dynasty which included five emperors who ruled until 1185 CE. The emperor’s life was recorded in the Alexiad, written by his daughter Anna Komnene.

Alexios came from a military family from Asia Minor, and he had royal blood for he was the nephew of Emperor Isaac Komnenos (r. 1057-1059 CE). Alexios’ father was John Komnenos, a senior military commander of the imperial guard (domestikos of the Scholai), and his mother, Anna Dalassena, was from a respected aristocratic family. In 1078 CE he married Irene Doukaina, who was distantly related to two former emperors and an ex-Tsar of the Bulgars. Alexios certainly had the pedigree to rise to the very top. He excelled in the army and rose to the position of general under Emperor Michael IV (r. 1034-1041 CE), never losing a battle.

Read More

107 notes

·

View notes